Have you ever had difficulties with combining Russian words? We’re sure you know what we’re talking about. Russian word order is important because it makes sentences make sense. Without understanding the main principles of combining words, you won’t be able to communicate with native speakers while, let’s say, vacationing in Russia over the holidays or chatting on social media.Russian sentence structure is one of the most significant parts of learning the grammar rules of this language. If you learn how to make sentences word by word now, you probably won’t have problems with more difficult themes in the future. So let’s start studying!

Table of Contents

- Overview of Word Order in Russian

- Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

- Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

- Word Order with Modifiers

- How to Change Your Sentence into a Yes-or-No Question

- Translation Exercises

- Conclusion

1. Overview of Word Order in Russian

The Russian language word order is SVO, but the existing grammar rules allow us to change it. So, sometimes, the typical SVO Russian word order can become VSO. That’s why we can say that word order in Russian sentences is quite flexible.

So, does word order matter in Russian? When comparing word order in English and Russian, we can notice one big difference. Russian word order doesn’t matter grammatically as much as English word order does.

Before having Russian sentence structure practice, you should definitely learn the most popular Russian phrases and words. It’s impossible to make sentences without knowing them by heart.

If you’re an advanced speaker, you may read Russian books and learn new words from them.

2. Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

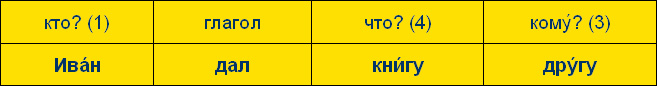

According to the basic Russian word order, you must start your sentence with the subject. Then comes the verb, followed by the object. If you use this word order in Russian sentences, you’ll never make a mistake. For example:

- Я читаю книгу. (Ya chitayu knigu.) — “I read a book.”

There are also some cases when you can use VSO instead of SVO. It’s appropriate if the sentence contains two verbs, and you want to emphasize the first one. It sounds good if you’re telling a story. For example:

- Читаю я книгу и вдруг… (Chitayu ya knigu i vdrug…) — “I’m reading a book, and suddenly…”

Be careful with VSO in Russian, though. It may sound really weird if you use it while making an order in a restaurant, talking to a stewardess during your flight to Russia, in an emergency, or in other formal situations.

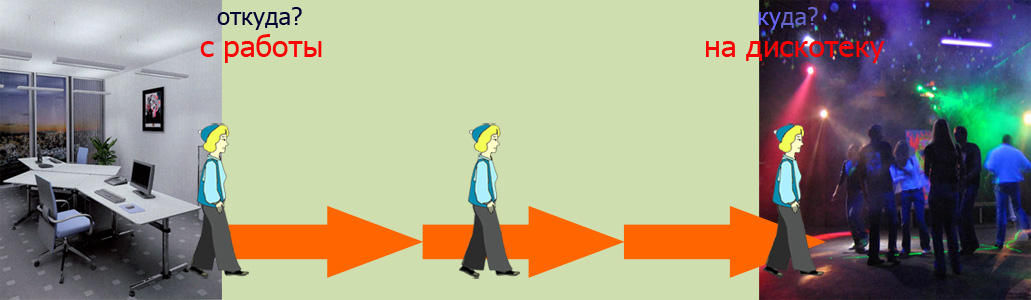

3. Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases answer the following questions:

- Where?

- When?

- In what way?

Prepositional phrases that answer the question “Where?” are typically used at the end of the sentence, after the object:

- Я читаю книгу дома. (Ya chitayu knigu doma.) — “I read a book at home.”

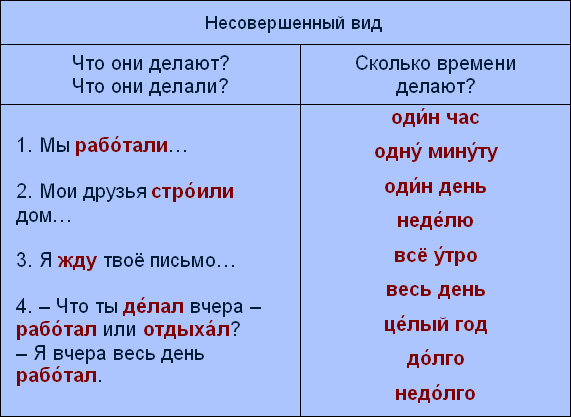

In Russian sentence structure, prepositional phrases that answer the question “When?” are put either at the very beginning or at the end of a sentence. The meaning of the phrase will change a bit, though. For example:

- Сегодня я читаю книгу. (Segodnya ya chitayu knigu.) — “Today, I read a book.”

- In this case, this sentence answers the question “What did I do today?”

- Я читаю книгу сегодня. (Ya chitayu knigu segodnya.) — “I read a book today.”

- This one answers the question “When did I read a book?”

Prepositional phrases that answer the question “In what way?” can be used right after the noun or at the end, after the verb. Both variants are grammatically correct, but the first one sounds more natural:

- Я увлеченно читаю книгу. (Ya uvlechyonno chitayu knigu.) — “I enthusiastically read a book.”

- Я читаю книгу увлеченно. (Ya chitayu knigu uvlechyonno.) — “I read a book enthusiastically.”

When there are two (or even more) prepositional phrases, you should use them in the following order:

- Put the prepositional phrase of time in the first place, before the noun.

- Add the prepositional phrase that answers the question “In what way?“ after the noun.

- Use the prepositional phrase of place after the object, at the end.

Here’s an example:

- Сегодня я увлеченно читаю книгу дома. (Segodnya ya uvlechyonno chitayu knigu doma.) — “Today, I enthusiastically read a book at home.”

If you don’t want to learn all these rules about building sentences in Russian, you may always put the prepositional phrase at the end of the sentence. Of course, doing so is appropriate only for beginners. Advanced students must know and use more complex rules regarding sentence structure in Russian.

4. Word Order with Modifiers

In most cases, the modifier is an adjective which describes something. In Russian word order, adjectives are always used before nouns:

- Я читаю интересную книгу. (Ya chitayu interesnuyu knigu.) — “I read an interesting book.”

If there are two or more adjectives in the sentence, you should:

- Firstly, use the one which expresses your own opinion about the subject or marks something about the subject that’s not very stable.

- Use the adjective which denotes a very stable aspect as close to the noun as possible.

For example:

- Я читаю интересную научную книгу. (Ya chitayu interesnuyu nauchnuyu knigu.) — “I read an interesting scientific book.”

Note that Russian sentence structure with adjectives is more or less flexible. There are no actual Russian word order rules that say you must use one type of adjective before another (e.g. shape before color). Try not to think too hard about how to order words in Russian when it comes to adjectives.

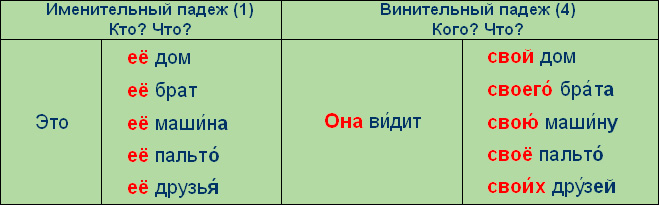

Other modifiers include the determiner, the numeral, and the possessive. According to the most typical word order in Russian, all modifiers like these come before the noun:

- Я читаю эту книгу. (Ya chitayu etu knigu.) — “I read this book.”

- Я читаю одну книгу. (Ya chitayu odnu knigu.) — “I read one book.”

- Я читаю его книгу. (Ya chitayu yego knigu.) — “I read his book.”

5. How to Change Your Sentence into a Yes-or-No Question

Typical Russian sentence structure makes it really easy to change affirmative constructions into yes-or-no-questions. If you want your Russian question word order to be correct, follow our instructions:

- Put the verb at the beginning.

- Add the conjunction ли (li) after the verb.

- Then use the noun and the object.

Here’s an example:

- Читаю ли я книгу? (Chitayu li ya knigu?) — “Do I read a book?”

6. Translation Exercises

We hope that you’ve read the information above thoroughly and understand the basic Russian sentence structures. Now we need to practice a bit with new sentences. We’ll use the most common Russian word order: SVO.

Please, stop comparing Russian sentence structure to that of English. They are both easy and comprehendible, believe us.

First of all, try to translate this phrase using your knowledge about how Russian sentences are structured:

- “I watched a movie.”

You may use the Russian dictionary if you don’t know the translations of some words.

If it’s difficult for you, think about Russian sentence structure compared to that in English. What do you know about them? They’re both SVOs! That’s why you can translate the simplest sentence word by word without the fear of making mistakes.

The correct Russian translation of the sentence above is:

- Я посмотрел фильм. (Ya posmotrel fil’m.)

Now let’s translate a slightly more difficult variant of this sentence:

- “I watched a good movie.”

If you’re struggling, look at our Russian sentence structure examples. There you’ll see that the adjective always comes before the noun:

- Я посмотрел хороший фильм. (Ya posmotrel khoroshiy fil’m.)

Now it’s time to make our English sentence more difficult. Translate this one:

- “I watched a good movie yesterday.”

Don’t panic! There are two ways to make this sentence:

- Вчера я посмотрел хороший фильм. (Vchera ya posmotrel khoroshiy fil’m.)

- Я посмотрел хороший фильм вчера. (Ya posmotrel khoroshiy fil’m vchera.)

Now try to translate the question:

- Did I watch a good movie yesterday?

There are two correct ways to translate it:

- Посмотрел ли я вчера хороший фильм? (Posmotrel li ya vchera khoroshiy fil’m?)

- Посмотрел ли я хороший фильм вчера? (Posmotrel li ya khoroshiy fil’m vchera?)

Sometimes there’s more than one appropriate way to express your thoughts in Russian.

7. Conclusion

You’ve learned a lot about Russian sentence structure and word order. We gave you not only the basic rules, but also some advanced techniques to build complex Russian sentences. Of course, it may seem too difficult right now. But don’t forget that Russian people don’t even think about how to combine words while speaking or writing. You only need some practice to do the same.

No one can fully cover the theme of sentence structure in Russian in one article, because this language is too rich. We’re sure you still have some questions: how to structure a sentence in Russian if there are two subjects and two verbs, how to form complex questions, how Russian sentence structure works in sentences with relative clauses, etc.

If you want to know more about this theme and find the answers to the above-mentioned questions, explore RussianPod101.com. Here you’ll find lots of free materials regarding vocabulary, grammar, and spelling. You’ll be able to download some useful information about Russian sentence structure.Do you want to try personal coaching? You can check our Premium PLUS service MyTeacher and take the assessment test to get started.

By

Last updated:

June 16, 2022

Russian adjectives are essential to sounding interesting when speaking Russian, but they play by their own rules!

In this post, you’ll master the art of using Russian adjectives correctly, as well as pick up new adjectives for your Russian repertoire.

You’ll also see some entertaining (yet effective) contextual examples to see the key adjective rules in practice.

Contents

- How Do Russian Adjectives Work?

-

- If the stem ends in a hard consonant

- If the adjective ends in -ний

- If the stem ends in a guttural or sibilant

- Short vs. Long Adjectives

- How to Form the Russian Comparative

-

- By using add-ons

- By changing adjectives for comparison

- How to Form the Russian Superlative

- Resources for Learning to Love Russian Adjectives

-

- The Cooljugator Russian Adjectives Declinator

- 100 Adjectives video from RussianPod101.com

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How Do Russian Adjectives Work?

The differences between Russian and English adjectives can feel overwhelming, but they boil down to one principle: the word endings play the same role in Russian as sentence structure does in English.

Because Russian words change depending on the role they play in a sentence, that also means that the structures aren’t as rigid as they are in English. Keep this advantage in mind when dealing with some of the complications they add—you’ll find it all more tolerable.

Even so, it does give you a lot more to remember than in languages similar to English. While “beautiful” will always be “beautiful,” no matter what it’s describing or where it goes in a sentence, but красивый (beautiful) shape-shifts depending on the situation.

This isn’t as random as it sounds, though! Next, I’ll show you some rules that demonstrate the relatively predictable nature of Russian adjective endings, as well as some contextual examples.

If the stem ends in a hard consonant

Adjectives in Russian are typically listed in dictionaries by their masculine singular nominative forms.

“Hard stem” adjectives ending in -ый in that default dictionary form are the most common kind of Russian adjectives. The stem is the part of the word that you’re left with once you remove the ending (in this case, -ый).

For example, let’s look at the word первый (first). If you remove the -ый ending, you’re left with перв-, which is your stem ending in a hard consonant.

There are also some adjectives that fall into this group that end in -ой. These are known as stressed adjectives because the ending is stressed. An example is молодой (young). The stressed adjectives in this group take the same endings as adjectives that end in -ый, except for the nominative masculine singular and the nominative inanimate accusative (used when the noun is an inanimate object in the accusative).

| Case | Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural |

| Nominative | -ый/-ой | -ая | -ое | -ые |

| Genitive | -ого | -ой | -ого | -ых |

| Accusative inan. | -ый/-ой | -ую | -ое | -ые |

| Accusative anim. | -ого | -ую | -ое | -ых |

| Dative | -ому | -ой | -ому | -ым |

| Instrumental | -ым | -ой (or -ою) | -ым | -ыми |

| Prepositional | -ом | -ой | -ом | -ых |

Did all those cases catch you off guard? That’s understandable. Since I won’t be getting into them in detail here, read this article for more information on what cases are and how to use them properly.

For now, let’s just look at a couple of examples of adjective use in the nominative case:

Первый день (the first day)

Молодой человек (the young man)

Here, both of these words are being used to modify masculine singular nouns in the nominative. So, each remains in its dictionary form and its ending matches the one in the top left box of our chart.

But what happens when that’s not the case, or rather, when that’s not the gender?

Let’s use the same adjectives, but with feminine singular nouns.

Первая неделя (the first week)

Молодая девушка (the young woman)

As you can see, the masculine singular endings have been removed from their stems and replaced with -ая, which is the ending for the feminine singular nominative (as you can see in the chart above).

Now, just for some real-world context and to explore the chart a little further, let’s take a look at a line from the Russian version of the trailer for the latest “Charlie’s Angels” remake:

Эй, ты чего застряла в первой гардеробной? (Hey, why are you stuck in Dressing Room 1?)

In this sentence, первый is present again, but it’s shifted from its default form for reasons beyond gender.

The noun гардеробной (dressing room), which is preceded by the preposition в (to, in, at), is in the prepositional case. It’s also a feminine noun and is singular. This means that первый, as the adjective modifying it, needs to inflect with the noun to become feminine, singular and prepositional. So the -ый ending has been removed and replaced with -ой.

By the way, if you checked the table above for that ending, you may have noticed the “or -ою” note for feminine/singular/prepositional. This is just an older ending for this particular declension that you might run across in written material.

If the adjective ends in -ний

“Soft stem” adjectives, or adjectives whose default forms end in -ний, take a different set of endings. There aren’t too many of these. Also, if you compare this chart to the one above, you’ll see that the pattern for declension is actually quite similar and mostly just differs by the first vowel in the ending.

| Case | Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural |

| Nominative | -ий | -яя | -ее | -ие |

| Genitive | -его | -ей | -его | -их |

| Accusative inan. | -ий | -юю | -ее | -ие |

| Accusative anim. | -его | -юю | -ее | -их |

| Dative | -ему | -ей | -ему | -им |

| Instrumental | -им | -ей (or -ею) | -им | -ими |

| Prepositional | -ем | -ей | -ем | -их |

For an example of a soft stem adjective, let’s take the color синий (blue):

Синий стол (blue table)

Once again, синий is in the nominative here because it’s modifying a nominative noun, and that noun стол (table) is masculine and singular, so синий remains in its default dictionary state.

In the trailer for “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2,” Rocket Raccoon asks if anyone has Scotch tape that he can use to wrap up an explosive device. When told that there isn’t any, he says (in the Russian version):

Ну, или синей изоленты хотя бы! (Well, or at least some blue electrical tape!)

Here, изоленты (electrical tape) is being used in the genitive, and it’s a feminine singular noun. So “blue” also needs to be feminine, singular and in the genitive.

If the stem ends in a guttural or sibilant

Okay, I know this is already a lot, but when adjective stems end in the letters г, к, х, ж, ч, ш or щ, things shake out a little differently.

Some Russian adjectives in their default masculine form end in -гий, -кий or -хий. These take the following endings:

| Case | Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural |

| Nominative | -ий/-ой | -ая | -ое | -ие |

| Genitive | -ого | -ой | -ого | -их |

| Accusative inan. | -ий | -ую | -ое | -ие |

| Accusative anim. | -ого/-ой | -ую | -ое | -их |

| Dative | -ому | -ой | -ому | -им |

| Instrumental | -им | -ой (or -ою) | -им | -ими |

| Prepositional | -ом | -ой | -ом | -их |

Now, as you can probably already see here, you’ll also get some stressed adjectives in this group. Some adjectives end in г, к, х, ж, ч, ш or щ and are followed by -ой. Those use the same endings above except for in the nominative masculine singular and the accusative inanimate.

Other adjectives end in -жий, -чий, -ший or -щий. Here are the endings for those adjectives specifically:

| Case | Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural |

| Nominative | -ий | -ая | -ее | -ие |

| Genitive | -его | -ей | -его | -их |

| Accusative inan. | -ий | -ую | -ее | -ие |

| Accusative anim. | -его | -ую | -ее | -их |

| Dative | -ему | -ей | -ему | -им |

| Instrumental | -им | -ей (or -ею) | -им | -ими |

| Prepositional | -ем | -ей | -ем | -их |

Let’s look at an example. A common Russian adjective is большой (big, large). Since the stem ends in ш and the default form ends in -ой, it falls into the first category above.

In this cute cartoon about a rabbit named Miffy, we learn where Miffy keeps her toys:

Миффи хранит свои игрушки в большой оранжевой корзине. (Miffy stores her toys in a large orange basket.)

The word for “basket” is feminine and is in the prepositional case here, along with the two adjectives that modify it, большой and оранжевой (orange).

Большой follows the rules laid out above. At first glance, it might look like nothing has changed about it at all, and technically, that’s true. But let’s look closer. The ending for feminine prepositional on the first chart above is -ой. So, we’re actually removing -ой and replacing it with another -ой, but you can see how we got there.

Now, let’s look at an adjective with an -ий ending:

Русский язык (Russian language)

Here, we’re looking at русский (Russian) in the nominative case along with язык, the masculine singular noun it’s modifying.

But let’s see how this adjective is used in a Russian cooking video on how to make borscht:

Украинский борщ является любимым блюдом многих русских людей… (Ukrainian borscht is the favorite dish of many Russian people…)

The form русских is modifying людей (people), which is a plural masculine noun being used in the genitive case, so it takes the ending for the plural genitive from the first table above. Hey, at least we don’t have to worry about genders in the plural!

If you’re really freaking out right now from all of the above, I would recommend watching this video on Russian adjectives from Antonia Romaker. It breaks things down in a very simple and gentle manner.

Remember, like so many other parts of learning Russian, the point here is not to remember all of this stuff right now. That would probably be impossible! But, if you can run with the general idea and stay calm, you’ll be able to get a lot more out of authentic Russian resources like books and movies.

And now, just a few more quick notes on adjectives. These could each take up a post in themselves, and we’ve already covered a lot, so we’ll just touch on these remaining concepts briefly.

Short vs. Long Adjectives

The short form is always in the nominative and used predicatively, meaning that rather than being placed right before a noun, it’s used in a sentence after where the word “is” or “are” would appear in English (in Russian, the verb for “to be” is almost always omitted in the present tense).

For example:

Это умная кошка. (This is a smart cat.)

Эта кошка умна. (This cat is smart.)

The short form of adjectives for masculine singular is the adjective stem (sometimes with an extra vowel inserted if the stem ends in a consonant cluster), with а or я added for the feminine version, о or е for neuter and ы or и for plural.

The default masculine form we’re working with here is умный (smart). Кошка is feminine (you can refer to a male cat as кот), so the default form needs to change to the feminine singular for the first sentence above.

In the second sentence, the short form is being used, with а being added to the stem to make it feminine.

Not all adjectives in Russian have a short form. Generally, the ones that do are qualitative adjectives that have to do with the measurable quality of a thing rather than its makeup or origin (for example, adjectives for nationality don’t have short forms).

It’s also worth noting that oftentimes, the stress placement changes when you use a short adjective form.

How to Form the Russian Comparative

In English, we compare qualities in people and things by using words like “more” or “less” and also by changing the form of adjectives. For example, we might say that one sandwich is “tastier” than another or that one room is “colder” than the one next to it.

Russian actually isn’t that different in this area. Here’s how to use adjectives comparatively in Russian.

By using add-ons

The Russian words for “more” and “less” are, respectively, более and менее. These words can simply go in front of an adjective to give the sense of “more” or “less.”

For example, высокий стол (the high table) can become более высокий стол (the higher table).

By changing adjectives for comparison

Another way to form the comparative is to drop off the adjective ending and add -ее:

Эта кошка умнее. (This cat is smarter.)

Some comparative adjectives are formed with -e and a shift in the letters that come before the ending.

For example, высокий (high) becomes выше (higher, like the Nyusha song).

As is the case in many languages, some Russian adjectives change completely when they switch to the comparative.

Notably, хороший (good) changes to лучше (better), and плохой (bad) switches to хуже (worse).

There are different ways to directly compare things or beings, but the simplest is by using чем (than):

Кошка умнее, чем собака. (The cat is smarter than the dog.)

How to Form the Russian Superlative

To form the superlative, you can put самый (the best) before a masculine adjective, самая before a feminine adjective and самое before a neuter adjective.

Она самая умная. (She is the smartest.)

Another easy way to express the same idea is with всех, which is the word for “all” in the genitive case:

Она умнее всех. (She is the smartest; literally, “She is smarter than all.”)

You can alternatively add -ейш to an adjective stem followed by -ий, -ая, -ое or -ие (for masculine, feminine, neuter or plural).

Она умнейшая. (She is the smartest.)

Stems that end in -к, -г, -х can be replaced with -ч, -ж and -ш followed by -айший (and changed in the same way above for other genders/numbers).

For example, высокий becomes высочайший (the highest).

Just like with the comparative, some superlative forms are irregular. For example, лучший (the best) and худший (the worst).

Resources for Learning to Love Russian Adjectives

The Cooljugator Russian Adjectives Declinator

This powerful little resource will give you declensions for over 21,000 Russian adjectives instantly.

100 Adjectives video from RussianPod101.com

This video will boost your vocabulary and set you up to start recognizing Russian adjectives in your writing and speech. Just learning the default dictionary forms of adjectives will help you recognize them when you see and hear them, and you can get to know the subtleties of formation and usage over time.

Adjectives seem like they should be simple and harmless, but it turns out so many aspects of the language are woven into them in complex and subtle ways.

Still, the best way forward is to simply arm yourself with knowledge and charge ahead.

Elisabeth Cook is a freelance writer who lives with two very clever cats but has nothing against dogs or people, and in any case thinks that the concept of being “smart” is a bit reductive, though it sounds cool in Russian. You can follow her on Twitter (@CooksChicken).

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Adjectives are used to describe people and objects. Words like “fast”, “new” and “beautiful” are all adjectives. Adjectives always describe nouns. (Whereas adverbs describe verbs or actions).

In the Russian language there are many different forms of each adjective. (Relating to the 6 cases, 3 genders, plural, short and the comparative). This may sound daunting at first, but in reality, it is fairly simple once you learn the system. The key is to just to learn the stem, or dictionary form of each adjective and then you can quickly form the rest.

The dictionary form of a Russian adjective is normally the normal, nominative, masculine form. These will almost always end in the letters “-ый” or “-ий”

There are 3 main types of Russian adjectives. Normal, Short and Comparative.

Normal Adjectives

Normal adjectives are those that come before a noun. For example in a phrase like “beautiful girl”, or “new car”.

Normal adjectives always agree in gender, and case with the noun that they are describing. This means that there are several ending for each adjective.

There are two systems to make the adjectives. Use the ‘Soft Adjectives’ table for those adjectives ending in “-ний”, otherwise use the ‘Hard Adjectives’

Normal Adjectives — Hard (“-ый”, “-ой”, “-ий” (but not “-ний”))

Hard Adjectives are by far the most common. Just substitute “-ый” for “-ой”, or “-ий” where needed. (other table entries remain the same).

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative Case | -ый | -ая | -ое | -ые |

| Accusative Case | -ый -ого (anim.) |

-ую | -ое | -ые -ых (anim.) |

| Genitive Case | -ого | -ой | -ого | -ых |

| Dative Case | -ому | -ой | -ому | -ым |

| Instrumental Case | -ым | -ой | -ым | -ыми |

| Prepositional Case | -ом | -ой | -ом | -ых |

For example, the word «новый» (new) ends in the letters -ый so we use the forms above.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative Case | новый | новая | новое | новые |

| Accusative Case | новый нового (anim.) |

новую | новое | новые новых (anim.) |

| Genitive Case | нового | новой | нового | новых |

| Dative Case | новому | новой | новому | новым |

| Instrumental Case | новым | новой | новым | новыми |

| Prepositional Case | новом | новой | новом | новых |

Normal Adjectives — Soft (“-ний”)

The soft form or normal adjectives is less common. It’s for adjectives ending in “-ний”.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative Case | -ий | -яя | -ее | -ие |

| Accusative Case | -ий -его (anim.) |

-юю | -ее | -ие -их (anim.) |

| Genitive Case | -его | -ей | -его | -их |

| Dative Case | -ему | -ей | -ему | -им |

| Instrumental Case | -им | -ей (or -ею) | -им | -ими |

| Prepositional Case | -ем | -ей | -ем | -их |

You will notice that the soft adjectives simply use the soft form of the first added vowel. («ы» becomes «и», «а» becomes «я», «о» becomes «е»,»у» becomes «ю»).

Otherwise the hard and soft forms are basically the same.

Remember that «его», and «ого», the «г» is pronounced like the english letter «v»

For example, the word «синий» (dark blue) ends in the letters -ий so we use the forular above.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative Case | синий | синяя | синее | синие |

| Accusative Case | синий синего (anim.) |

синюю | синее | синие синих (anim.) |

| Genitive Case | синего | синей | синего | синих |

| Dative Case | синему | синей | синему | синим |

| Instrumental Case | синим | синей | синим | синими |

| Prepositional Case | синем | синей | синем | синих |

Short Adjectives

The second main type of Russian adjectives are the ‘short form’. We don’t really have this form in English, but we do use adjectives the same way.

The short form is generally used to make a statement about something. In English it normally follows the word “is” or “are”. For example, “You are beautiful”, “He is busy”. Notice that the adjective is not followed by a noun. The use of the short form is generally limited to such simple sentences.

It is important to note that not all adjectives can have a short form, (but most do). One notable example is русский (Russian).

Cases are not relevant when using short adjectives, as you only need the nominative case when making such statements. The adjective should still agree in gender with the noun. Masculine nouns just use the stem of the adjective in the short form. Feminine adds “а”. Neuter adds “о”. Plural adds “ы” or “и”.

If the adjective is masculine and the stem ends in two consonants, then add a vowel (“о”, “е” or “ё”) so that the word is easier to read.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Adjectives | — | -а | -о | -ы or -и |

For Example.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Adjectives | красив | красива | красиво | красивы |

Comparative Adjectives

Often you may wish to use adjectives to compare one thing to another. To do this we normally use the comparative adjectives.

These adjectives are just adapted from normal adjectives. However the are a couple of methods that you can use. All of these methods are relatively easy.

Method 1 : More / Less

The lazy way to compare two things is to use the Russian words for “more” and “less”. Here are the Russian words that you need to use.

более — more

менее — less

чем — than

When comparing adjectives using this method, use the normal adjectives. Here are some examples.

более красивый дом — A more beautiful house.

менее красивый дом — A less beautiful house.

Анна более красивая женщина, чем Елена. — Anna is a more beautiful woman than Elena.

Анна менее красивая женщина, чем Елена. — Anna is a less beautiful woman than Elena.

Method 2 : Comparative Adjectives

Although the above examples are acceptable, Russians will prefer to use the comparative adjectives most of the time.

These are formed by adding either “ее” or “е” to the stem of the adjective. It is worth noting that these forms can also be used as comparative adverbs.

1. If the last consonant of the adjective is н, л, р, п, б, м, в : Add “ее”

быстрый(fast) — быстрее(faster)

красивый(beautiful) — красивее(more beautiful, also: more beautifully)

трудный(difficult) — труднее(more difficult , also: more difficultly)

2. Otherwise add “е” (but the stem will display typical consonant mutation).

большой(big) — больше(bigger)

лёгкий(easy) — легче(easier)

дешёвый(cheap) — дешевле(cheaper)

дорогой(expensive) — дороже(more expensive)

3. As with English the words «good» and «bad» have irregular comparative forms.

хороший(good) — лучше(better)

плохой(bad) — хуже(worse)

Here are some examples.

Москва красивее, чем Лондон. — Moscow is more beautiful than London.

Анна красивее, чем Елена. — Anna is more beautiful than Elena.

3. Without Чем

The third way to make comparisons is almost the same as method 2, except the we omit the word “Чем” (than). This method is popular in spoken Russian.

In order to omit “Чем” we must use the second noun in the genitive case. When using this method the order of words in the sentence is important.

Москва красивее Лондона. — Moscow is more beautiful than London.

Анна красивее Елены. — Anna is more beautiful than Elena.

Superlative Adjectives — Most

The superlative is how we indicate something is the best, or the most. (Eg, “the most beautiful”, “smallest”, “oldest”).

To do this we simply use the adjective “самый” (most) which declines like a normal adjective.

самый красивый дом — The most beautiful house.

самое дешёвое вино — The cheapest wine.

самая красивая женщина — The most beautiful woman

Conclusion

There are many different forms of adjectives to learn if you wish to write Russian. However as you learn the Russian language you will find that they are actually not too hard to remember.

If you would like to learn some new Russian adjectives try our adjectives page in our vocabulary section

Russian grammar —> Word order in Russian

In English, the word order plays an important role because it shows the relationships between parts in the sentence (subject, object, etc.). For example, if we say «Cats eat mice», we clearly understand that «cats» is here the subject of the action «eat» and the object of this action is «mice». If we switch the position of nouns «cats» and «mice», we get «Mice eat cats», a sentence with a different meaning. So, in English sentence the grammatical sense depends on word order.

However, Russian word order is very flexible. The relationships between parts of the Russian sentence are shown by the endings of words. Depending on the grammatical sense and role in the sentence, Russian words have different endings.

Look at the following example:

Кошки едят мышей. — Cats eat mice.

In the Russian sentence, the object of the action is shown by the ending -ей of the word мышей. That is why, if you change the position of the Russian words, the overall meaning of the sentence will not change. You can say:

Кошки едят мышей.

Мышей едят кошки.

Едят кошки мышей.

Едят мышей кошки.

In these sentences, the subject and the object of the action «eat» remain the same.

So, because of words endings, the parts of the Russian sentence can go in almost any order without causing any misunderstanding on the part of the listener.

If you want to know more about word endings and their grammatical role in Russian, we recommend you to see the page Cases in Russian on our website.

For the beginner in Russian there is nothing very important to remember about word order – other than the fact that it is very flexible. For example, while translating a Russian sentence, you can use the word order of the English sentence and native speakers will always understand you.

At the same time, Russian word order has its own peculiarities. One of these peculiarities is that in written Russian new information (or emphasized information) comes at the end of the sentence. For example, look at the sentence:

Мария едет в Москву. — Maria goes to Moscow.

The emphasis is on the word Москва (Moscow), it is a new information because this sentence tells where Maria goes. If another word order is used:

В Москву едет Мария. – It is Maria who goes to Moscow.

The emphasis is on the word Мария (Maria), and, in this case, the sentence tells who goes to Moscow.

In a conversation, the word order is more flexible since intonation and stress may be used to show the emphasized information in a sentence.

Taking Russian language course London or trying to learn Russian on your own? Then you know that when you learn a new language, it involves more than simply thumbing through a Russian dictionary or memorizing the Russian numbers and days of the week. You need to learn Russian grammar rules in order to build understandable sentences.

Of course, you can learn some Russian words and phrases from your textbooks or phrase book, but at some point you will want to go beyond saying hello, pleased to meet you, giving a rote compliment and asking “Do you speak English?” If you want to speak Russian halfway fluently, Russian vocabulary is not the only aspect you need to work on: you will also need to study pronunciation, reading the Cyrillic alphabet and, of course, sentence structure.

So here is a small guide on how to properly structure Russian phrases, so that the next time you travel to St. Petersburg, Moscow or elsewhere in the former USSR you will be understood.

The best Russian tutors available

5 (19 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (10 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (18 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (14 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (19 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (10 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (18 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (14 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

Basic Russian Sentence Structure

In English, the basic sentence structure is:

Subject + Verb + Object

This is true in Russian grammar as well. Whether you are taking Russian lessons online or in a classroom, most phrases you learn will be set up this way:

У меня простуда

I have a cold.

The subject is in the nominative case (the form of the noun you will find first in a dictionary) whereas the direct object is in the accusative. You will need to conjugate Russian verbs in the proper tense, of course.

Introducing indirect objects

Indirect objects (in English, they are introduced by “to” or “by”) usually come after the verb, but whereas in English they come:

- After the direct object if a preposition (”to”, “for”, “by”) is used (I gave a book to Sanya.)

- Before the direct object if none is used (I gave Sanya a book.)

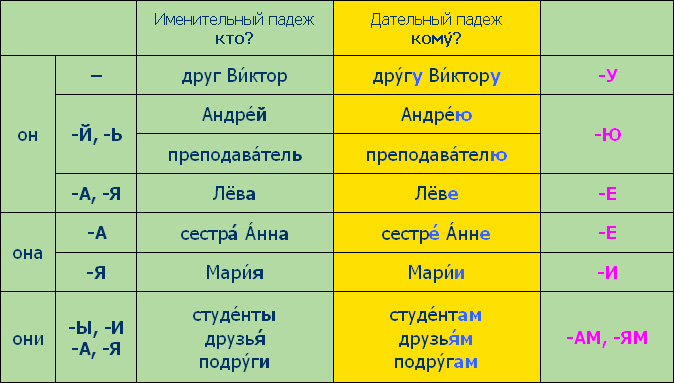

Russian words — in this case, the nouns — are declined. We have seen that subjects are in the nominative case and direct objects in the accusative case. This means that the indirect object can be placed either before or after the direct object without anyone becoming confused, as it will be in the dative case.

You can say:

Он пишет письмо родителям.

He wrote a letter to his parents.

Or:

Он пишет письмо родителям

He wrote his parents a letter.

Here is a table with the dative declension for the most common noun endings in Russian:

| Gender | Ending | Dative singular | Dative plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | consonant | add -y | add -ам |

| Masculine | -й | replace -й with -ю | replace -й with -ям |

| Masculine | -ь | replace -ь with -ю | replace -ь with -ям |

| Feminine | -а | replace -а with -е | replace -а with -ам |

| Feminine | -я (except for -ия) | replace -я with -е | replace -я with -ям |

| Feminine | -ия | replace -ия with -и | replace -я with -ям (keep the и) |

| Feminine | -ь | replace -ь with -и | replace -ь with -ям |

| Neuter | -о | replace -о with -y | replace -о with -ам |

| Neuter | -е (except for examples below) | replace -е with -ю | replace -е with -ям |

| Neuter | -це, -же, -ше, -ще | replace -е with -y | replace -е with -ам |

Pronouns in Russian word order

While generally, objects come after the verb, when an object is a pronoun they always come before the verb.

я его знаю

I know him.

Modifying Nouns and Verbs in Russian

Adjectives and other noun modifiers

Adjectives come before the noun they modify:

красный цветок

A red flowerбольшои дом

A big house

Genitives and other noun modifiers usually only come after the noun.

Adverbs and adverbial phrases

Adverbial phrases indicating time, place, mode etc. are generally at the end of the sentence.

я иду в школу

I am going to school.

Make learning Russian fun with Russian language games to practise sentence structure.

How to Place Emphasis in a Russian Sentence

Now that we have talked about the order of Russian words in a sentence, here’s something you need to know: the subject+verb+objects order is optional.

Because Russian has cases, word order is not quite as important for determining the role of each noun in the sentence. This means that nouns can be moved around for emphasis.

New information tends to come at the end of a sentence. For example, in English we might differentiate between:

- My sister is an architect. The important information is not the sister, but the fact that she’s an architect.

- My sister is the architect. The sister is the more important information here. There was talk of architects and the sister is named as one.

When you speak Russian, you can do this by reversing the word order.

- Моя сестра архитектор corresponds to “my sister is an architect.”

- Архитектор моя сестра is the equivalent of “my sister is the architect.”

This means that everything we said before is only one way of learning basic Russian sentence structure. It is the most usual way, and it’s good to remember these tips as they will help you focus on what you want to say without worrying about emphasis.

However, as you progress from beginner to intermediate level or even advanced levels and learn to read Russian literature in the original rather than translations, you will notice that many authors such as Pushkin or Tolstoy will switch around words in a sentence. That’s why it’s so important to gain proficiency in the declensions of Russian nouns, so you always know what function a word has in a sentence.

If you travel to Russia and your listening comprehension increases, you will also notice people doing it in common speech and as you gain fluency, you can try it out as well as you figure out what works and what doesn’t. This is something you can practise in Russian lessons with your teacher.

Asking Questions in Russian

There are two types of questions:

- Questions that can be answered by either yes or no

- Questions that need a more comprehensive answer and generally need question words

Asking yes or no questions in Russian

Simple questions in the Russian language course are just that: simple. You don’t need to change anything about the word order, simply add a question mark when writing or raise your voice at the end when speaking.

Он пишем письмо

He is writing a letterОн пишем письмо?

Is he writing a letter?

Asking questions in Russian is an important part of learning the language. Photo credit: hehheh78 on VisualHunt

Asking questions using question words

Common question words in English are:

- Who?

- What?

- When?

- Where?

- Why?

- How?

But there are many more, compound question tags that also have Russian counterparts, such as:

- Whose?

- How many?

- How much?

- What kind/ what sort?

Also, Russian uses its own question words for “where to” (куда) and where from (откуда).

Here are some of the most frequently used question words in Russian:

| English | Russian |

|---|---|

| Who | кто |

| What | почему |

| When | когда |

| Where | где |

| Why | что |

| How | как |

| How much/how many | сколько |

You can pair them with common Russian verbs to form useful questions.

Though most aspects of Russian sentences are permutable, question words are always at the beginning of a sentence.

что зто

What is this?кто зто

Who is it?где зто

Where is it?

Now, some of these need to be declined to suit their grammatical role in the sentence. For example, both что (what?) and кто (who?) are declined:

| Nominative | Accusative | Dative | Genitive | Instrumental | Prepositional |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| что | что | чему | черо | чем | чём |

| кто | кого | кому | кого | кем | ком |

Also, whose? (чей) needs to agree in number, case and gender to the object or the person it refers to.

Grammar Notes

NOUNS

NOUNS: GENDER

Russian nouns are divided into three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Usually, one can determine the noun gender by the noun ending.

Most masculine nouns end in:

Feminine nouns usually end in:

Most neuter nouns end in:

| MASCULINE GENDER ОН |

FEMININE GENDER ОНА |

NEUTER GENDER ОНО |

| паспорт журнал компьютер музей словарь |

страна газета виза фамилия площадь |

письмо яблоко море кафе |

NOUNS: NUMBER

In the Russian language plural nouns are constructed in the following way:

- — to the masculine singular noun the endings -Ы or -И are added

- -Ы, -И:

- документ – документы

- журнал – журналы

- -Ы, -И:

- — feminine noun endings undergo changes:

- «-А» is replaced by «-Ы»

- виза – визы

- газета – газеты

- «-Я» is replaced by «-И»

- фамилия – фамилии

- «-А» is replaced by «-Ы»

- — neuter nouns endings undergo changes:

- -А

- письмо – письма

- — Е is replaced by-Я

- море – моря

- -А

The word ЯБЛОКО (apple) is an exception, the plural form of it is ЯБЛОКИ!

Please, remember! The words «ДЕНЬГИ», «ОЧКИ» have only the plural forms.

| Singular number | Plural number | |

| ОН | документ | документы |

| журнал | журналы | |

| ОНА | виза | визы |

| газета | газеты | |

| фамилия | фамилии | |

| ОНО | письмо | письма |

| море | моря | |

| – | деньги | |

| – | очки |

Personal Pronouns

The pronouns «ОН», «ОНА» can denote either animate or inanimate entities. The pronoun ОНО always denotes inanimate objects.

| КТО? | ЧТО? | |

| ОН | Это турист. Он тут. | Это паспорт. Он тут. |

| ОНА | Это девушка. Она тут. | Это виза. Она тут. |

| ОНО | – | Это яблоко. Оно тут. |

The pronoun «ВЫ» is not only a plural form. It is also used as a polite form to address a stranger or an older person.

OCCUPATIONS: Feminine nouns

Feminine nouns inidicating occupations or professions are derived from masculine nouns with the help of the suffix «-К-». And, of course, the noun will acquire a feminine ending as well. For example:

| он | она |

| студент | студентка |

| журналист | журналистка |

| турист | туристка |

For example:

Он

студент. – Она студентка.

Он

журналист. – Она журналистка.

But there is a group of nouns indicating occupations which don’t change by gender. For example:

Он

менеджер. – Она менеджер.

Он инженер.

– Она инженер.

Он доктор.

– Она доктор.

Он музыкант.

– Она музыкант.

Negation

To give a negative answer to a question formed without a special question word, you have to use TWO negative words (or double negation): «НЕТ» и «НЕ» . First, you have to say «НЕТ» (No,…) and then repeat the negative particle «НЕ» preceeding negation.

For example: ЭТО КЛЮЧ? НЕТ, ЭТО НЕ КЛЮЧ.

- БАГАЖ ТУТ? НЕТ, БАГАЖ НЕ ТУТ.

- ВЫ СТУДЕНТ? НЕТ, Я НЕ СТУДЕНТ.

- ОНА МЕНЕДЖЕР? НЕТ, ОНА НЕ МЕНЕДЖЕР.

Attention!

Intonation plays a big role in the question and answer. In the question you emphasize the word that is most meaningful or important to you — that’s where the intonation will rise.

In the answer the negative particle «не» and the following word are pronounced together as one phonetic unit or word. As a rule, the stress does not fall on the particle «не».

- «не тут» — [ нитут]

- «не она» — [ ниана]

Depending on the meaning of the question, «не» can be placed before:

- Noun:

- Это стол? — Нет, не стол.

- Adverb:

- Дом там? — Нет, не там.

- Verb:

- Ты знаешь? — Нет, не знаю.

- Adjective:

- Дом большой? – Нет, не большой.

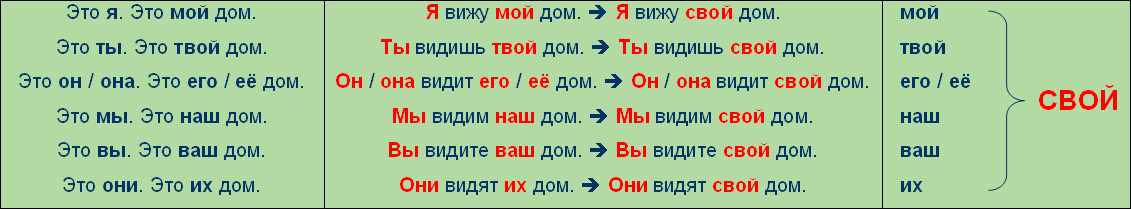

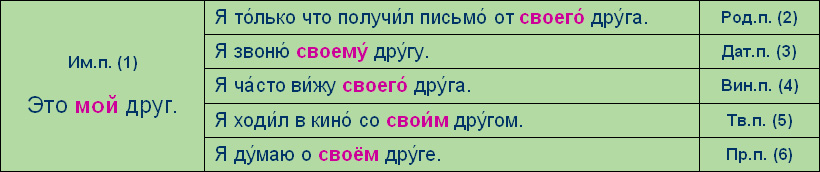

Pronouns

- Posessive pronouns always agree in gender and number with the nouns they refer to. For example, «мой билет» (my ticket) — «билет» is a masculine noun, «твоя виза» (your entry visa) — «виза» is a feminine noun, ‘моё яблокоa’ (my apple) — яблоко is a neuter noun, «ваши деньги» (your money) — «деньги» is a plural noun.

- Pronoun forms его, её, их don’t change. You should select the pronoun to agree with the gender of the person who owns the object:

- Это Антон. Он здесь. Это его билет, его виза, его фото, его деньги.

- Это Анна. Она там. Это её билет, её виза, её фото, её деньги.

- Это Антон и Анна. Это они. Это их журнал, их виза, их фото, их деньги.

- To find out who owns the object, you should ask a question using special question pronoun forms: чей? чья? чьё? чьи? (whose?). You should select a pronoun form which agrees in gender and number with the noun referred to by the question pronoun.

- Это Мария. Это билет. Это её билет. Чей это билет? (The noun «билет» is masculine, so you need the question word «ЧЕЙ»? ).

- Это Джон. Это виза. Это его виза. Чья это виза? (The noun «виза» is feminine, so you need the question word «ЧЬЯ»? ).

- Это Антон. Это яблоко. Это его яблоко. Чьё это яблоко? (The noun «яблоко» is neuter, so you need the question word «ЧЬЁ»? ).

- Это Анна и Джон. Это деньги. Это их деньги. Чьи это деньги? (The noun «деньги» is plural, so you need the question word «ЧЬИ»? ).

NATIONALITY NOUNS

There are special words to indicate nationalities in Russian. To describe males and females of the same nationality, different masculine and feminine nouns will be used. To indicate nationality of several people, in Russian a special plural form can be used.

Take a look at the table: masculine nouns are forned with the help of suffixes

-ец (канадец), -ан+-ец (американец),

less often the suffix анин is used: (англичанин).

Some masculine nationality nouns have special forms: француз, турок, грек.

The form русский (русская, русские)

is also an exceptionРусский – is an adjective, not a noun form!

Most feminine nationality nouns end in -ка (канадка),

-анка (американка) или -янка (китаянка), however, there are exceptions:

француженка.

Plural froms are constructed following the standard rules:

If the masculine singular noun ends in а -ец (канадец) or -анец

(американец), the plural form ends in -цы

(канадцы) или -анцы (американцы). The standard rule of adding an ending i>-ы or -и to form the plural applies even to exception nouns, such as

француз, грек — plural forms — французы, греки. Please, note that the form турок – турки.

Masculine nouns ending in –анин have unique plural forms,

ending in –ане: англичанин – англичане.

As you can see there are many ways in Russian to form nationality nouns. The most important thing to remember is this: nationalities in Russian are expressed by special nouns, not by adjectives. And it is best to memorize nationality nouns that are exceptions.

ADVERBS

To characterise an action, or describe a state, adverbs are used in most cases. Adverb is a part of speech in the Russian language which never changes it’s form.

To indicate where something an action took place, we use «adverbs of place». They answer the question где? (where?).

- Номер справа.

- Лифт там, слева.

- Ресторан внизу.

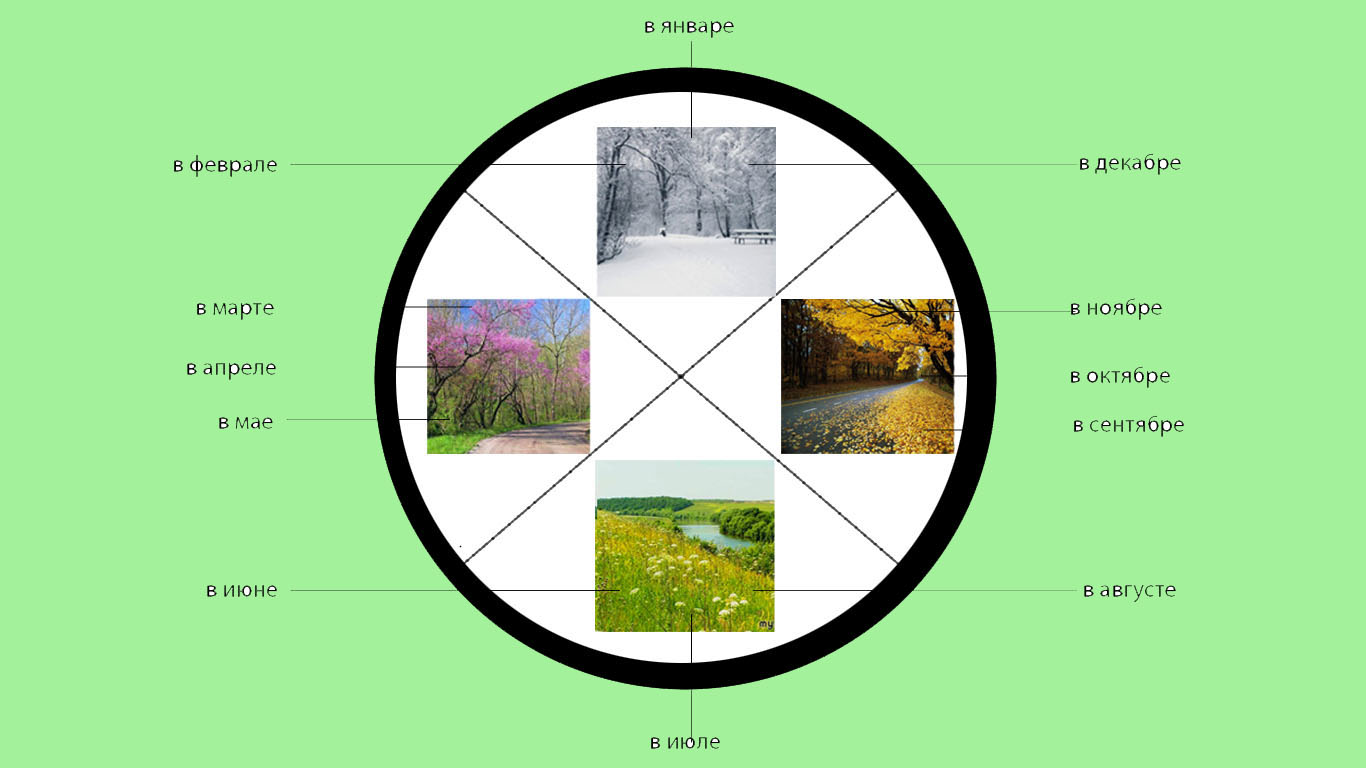

To indicate when something takes place, we use «adverbs of time» which answer the question когда? (when?).

- Завтрак утром, обед днём, ужин вечером.

To characterise an action or state, we use «adverbs of manner» which answer the question как? (how?, or «in which manner the action took place?»).

- Летом жарко,зимой холодно.

- Это хорошо.

- В ресторане очень дорого.

Most often, adverbs are used with verbs expressing states or actions, with adjectives, and with other adverbs. Adverbs are placed in front of these words and indicate intensity of an action, intensity of a state, or characteristic.

You can also find adverbs in sentences with the word ЭТО (it, this).

- Сериал – это скучно!

- Детектив – это интересно.

To describe a state of the environment or nature, we use impersonal sentences (lacking an active subject in the Nominative case) with adverbs. Such sentences always include indications of time or location. Usually, the information about where or when the action is taking place will be placed at the beginning of a sentence, and the information about the action or state characteristics (как?) is placed at the end of a sentence.

The Russian language differs from most other European languages in that in sentences describing the state of the environment in the present tense, the verb быть (to be) is not used. However, in the past and future tenses the verb «быть» is necessarily present in its appropriate tense form.

- Сегодня жарко.

- Вчера было жарко.

- Завтра тоже будет жарко.

Remember! The most important (new) information is placed at the end of the sentence. Compare:

- Завтрак утром (не днём и не вечером).

- Утром завтрак (не обед и не ужин).

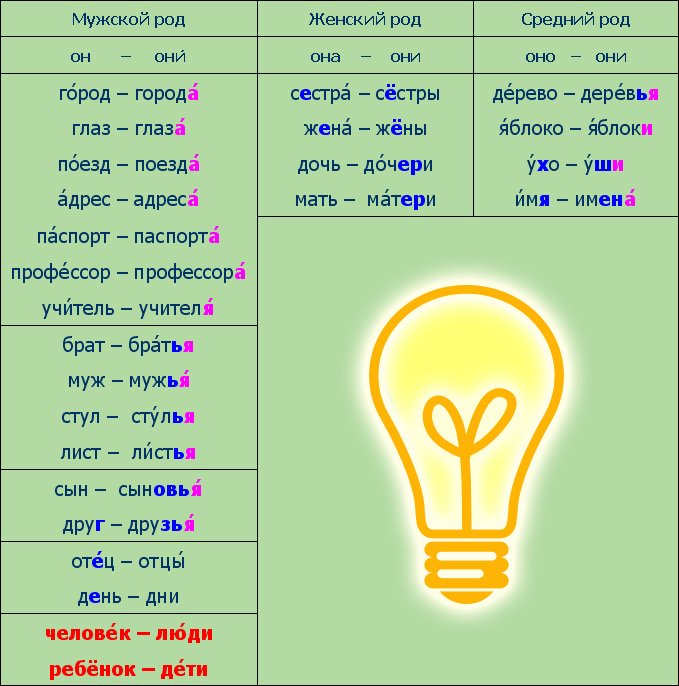

Plural Nouns (continued)

The plural form of masculine nouns ending in -г, -к, -х, -ж, -ш, -ч, -щ, and feminine nouns ending in -га, -ка, -ха, -жа, -ша, -ча, -ща, is formed using the letter «и»:

Please, memorize some special plural forms:

брат – бра́тья дом – дома́ ребё́нок – де́ти

стул – сту́лья город – города́ челове́к – лю́ди

друг – дру

з

ья́ адрес – адреса

Borrowed nouns that end in vowels: «о», «-а», «-и», «-у» don’t have a separate plural form: такси (sing) = такси (pl) = taxi, метро = метро (metro), пальто = пальто (coat), интервью (interview).

There are some nouns in Russian which have only the plural form: «джинсы», «деньги», «очки», «часы».

Please, remember! These are exceptions.

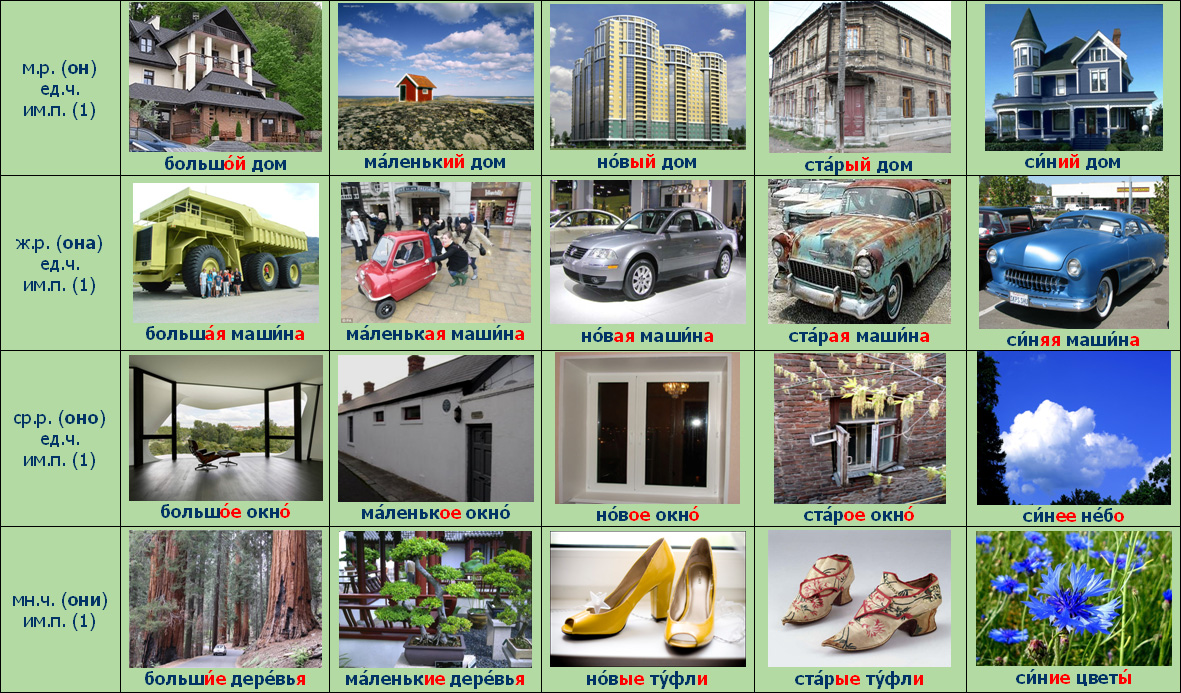

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that describe objects, i.e. indicate objects’ characteristics and attributes. The adjective answers a question: “«какой?» /”What kind?” or “Which one?” (see below). An adjective’s grammar form is always identical to that of a noun it characterizes, in other words, the adjective always has the same gender, number and case, as the noun:

красивый дом

красивая девушка

красивое дерево

красивые цветы

Pay attention to the endings of the nouns and adjectives in the table:

A Russian adjective follows either a “hard” or “soft” conjugation pattern – it means that one should pay attention to which consonant — hard or soft – precedes the adjective’s ending: e.g.in “новый” – [в] is a hard consonant, so the ending will be “- ый”, while in «синий” — [н’] is a soft consonant, thus, the ending is «ий».

. The following are the “hard” conjugation pattern endings: но́вый, но́вая, но́вое, но́выеThe following are the “soft” conjugation pattern endings: си́ний, си́няя, си́нее, си́ниеHowever, it is important to remember that in a stressed position masculine adjectives that follow the “hard” conjugation pattern will end in «ОЙ» instead of «ЫЙ»: голубо́й, молодо́й и т.д.The “soft” conjugation pattern adjectives have to be memorized, as they reflect linguistic evolution. In most cases, these are nouns that end in -ний: си́ний, ле́тний, зи́мний, вчера́шний, etc.

Question words: «Какой? Какая? Какое? «(what kind? which one?)

When an inquiry is made about qualitative characteristics of a person or inanimate object («what kind of a person or object is it?»), in Russian questions «какой? какая? какое? какие?» are asked. The question word usually opens the sentence, and agrees in gender and number with the noun it refers to. With the masculine noun, you will use the question word «какой?», with the feminine noun — «какая?», with the neuter noun — «какое?», and with plural nouns — «какие?».

«Какой это человек?» («What kind of a person is he?»): the noun «человек» (person) is masculine and singular, and the question word «какой»? is appropriate to use.

«Какая это рыба»? («What kind of a fish is it?»): «рыба» (fish) is a feminine noun in Russian, and the appropriate question word is «какая?»

«Какое это пиво?» («What kind of a beer is it?»): «пиво» (beer) is a neuter noun, and the appropriate question word is «какое»)

«Какие это дети?» («What kind of children are these?»): «дети» is a plural noun, and the appropriate question word is «какие?»)

Replies to such questions will include adjectives which agree with the nouns in gender and number.

«Это вкусн║ая рыба». («This is a tasty fish.»)

Also, questions «какой? какая? какое? какие?» can be used to inquire about an object’s name. Compare:

«Какое это пиво?» («What kind of a beer is it?»)

«Это холодное пиво». («This is a cold beer».)

«Это пиво «Балтика». («This is the Baltika brand beer».)

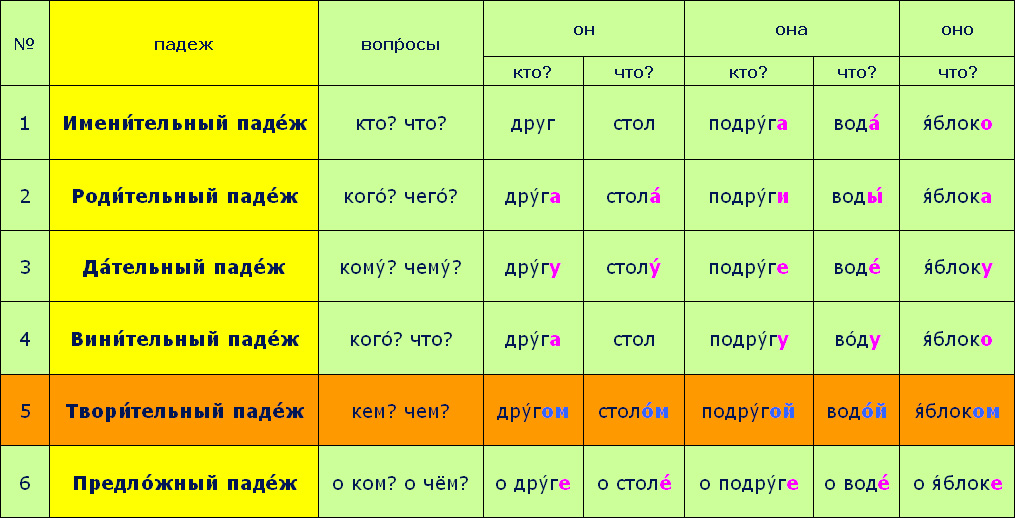

CASES in Russian

Russian nouns change (are inflected) in a sentence. The noun’s form depends on the noun’s role in a sentence. Such noun forms are known as «cases». There are six cases in the Russian language, and every case answers a specific case question for animate and inanimate nouns, is distinguished by a set of case endings, and has specific meaning and functions in the sentence.

There are six cases in the Russian language:

The Nominative Case is used when a noun is the grammatical subject (sometimes – a predicate) of a sentence and answers the questions: «Who?» or «What?». As a rule, in a dictionary nouns are listed in the Nominative case.

PREPOSITIONAL CASE

To indicate location of a person or an object (i.e. give an answer to the question «where?»), you should select a noun in the Prepositional case form.

To indicate location, nouns in the Prepositional case are always used with the prepositions «в«(in) or «на«(on).

If an object is located inside something, we use a preposition » в» (in):

«шарф в сумке» — «a scarf in a bag»,

«телефон в столе» -«a telephone in a desk drawer»,

«фото в книге» -«a photo in a book».

And if an object is located on a top surface of something , we use a preposition «на» (on):

«шарф на сумке» -«a scarf on a bag»,

«телефон на столе» — «a telephone on a desk»,

«фото на книге» — «a photo on a book».

Please, note additional rules and tips on how to use the prepositions «в» (in) and «на» (on):

Книги на полке.

Цветы в вазе.

Preposition В (in)

- If a person or object is in a room or in a building, in most cases the preposition « в» is used:

«Антон b>в комнате» — «Anton is in the room.», «Иван в ресторане». – «Ivan is in the restaurant.»

Exceptions:

на почте (post office)

на стадионе (stadium)

на факультете (college department)

на фабрике (factory) - If we speak about a country or a city, the preposition в is also used:

«Антон в Америке». – «Anton is in America.»

«Иван в Петербурге». – «Ivan is in Petersburg.» - The words парк (park), сад (garden), лес (forest) are also used with the preposition в:

«Мы в парке». – «We are in the park.»; «Она в лесу». – «She is in the forest.»

Preposition

на («at»)

- If a person is attending an event or performance,

the preposition » на» is used:

«Антон на

уроке.» — «Anton is at a lesson»; » Иван на

дискотеке» — «Ivan is at a disko dance.» - The preposition «на» is used with the words:

«улица» ( street), «бульвар»» ( boulevard), «проспект»» (prospect, avenue), «площадь»

(square). They indicate that a person stays in the open and «on the surface» :

«Я сейчас на

улице«.

Prepositional case: Noun Endings

- If the masculine noun ends in a consonant (in the Nominative case),

the Prepositional case ending «-е» is attached to the Nominative case form:

парк – в парке,

магазин – в магазине.

But if the masculine noun ends in

«ь» or «й»,

this last letter will be replaced by the ending -е:

музей

– в музее,

словарь

– в словаре.

2) Likewise, if the feminine noun ends in -а or -я,

this last letter will be replaced by the ending «е».

Москва

– в Москве, песня – в песне.

- If the neuter noun

ends in-о (in the Nominative case),

replace this last letter with the ending -е:

письмо – в письме

But

if the neuter noun ends in -е,

it will not change its form at all

and will only acquire the preposition в or на:

поле – в поле,

море – на море.

- If the feminine noun ends in «ь»,

in the Prepositional case this last letter will be replaced by the ending i> -и:

– в тетради. (Please, note the difference: if the masculine noun ends in -ь in the Nominative case, in the Prepositional case it will have the ending е: словарь

– в словаре).

- If in the Nominative case, the feminine noun ends in-ия,or the neuter noun ends in -ие in the Prepositional case they will end in -ии:

Россия

– в России,

здание – в здании.

There is a special group of Russian nouns

which have a different ending «-y» in the Prepositional case singular. Please, memorize them!

Verbs

All Russian verbs are inflected (modified) for person and number. There are 2 sets of verb endings, or 2 Conjugation patterns. The Infinitive verb form ( signaled by endings -ть, -ти, -чь) always remains unchanged. This is the very form you see in a dictionary. In a sentence the verb form will change because it has to «agree» with a person and number of the verb’s subject: I, you, he or she, it (singular), we, you, they (plural).

Я знаю. Они знают. Вы знаете.

Please, note that there is one third-person singular verbal form for both animate and inanimate subjects of all three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. «Антон (Anton) работа║ет». «Магазин (a store) работа║ет».»Анна (Anna) работа║ет». «Школа (school) работа║ет». «Радио (radio set) не работа║ет». The third-person plural form of a verb will also be the same for inanimate and animate subjects :»Антон и Анна (Anton and Anna) работа║ют». «Магазины (stores) работа║ют».

Endings of personal verbal forms depend on a verb’s conjugation type — I or II. Most Russian verbs which in the Infinitive form end in «-ить» are Conjugation II verbs: «любить», «звонить». Verbs which in the infinitive form have all other endings are Conjugation I verbs: «знать», «гулять», «отдохнуть», «иметь», etc. But you will come across a lot of exceptions in verb conjugation!

Conjugation I

For Conjugation I verbs, to form the verb conjugation in the present tense one must:

- drop the infinitive ending, or the last two letters: «зна║ть», «дела║ть», «работа║ть»)

- then add to the remaining part (зна-, дела-, работа-) a correct personal ending: (I) зна║ю, (you, sing.) дела║ешь. In the first-person singular and third-person plural, the verb ending will be «- ю» or «-ют» if the ending is preceeded by a vowel: «(I) работА║ю, (they) работаА║ют»), and if the ending is preceeded by a consonant, the verb will end in -«-у» or «-ут»: «(I) моГ-у, (they) моГ-ут».

Conjugation II

For Conjugation II verbs, the verb conjugation in the present tense is formed in exactly the same way, as for Conjugation I verbs — but the personal verb endings are different:

Please, note the following spelling rule: letters «ч» and «ш» are never followed by letters «ю» or «я»; instead, you should write «y» or «a»: «я пиШ║у», «я уЧ║ у», «они пиШ║ут», «они уЧ║ат».

The verb «хотеть» (to want) is an exception. It follows neither the Conjugation I, nor Conjugation II pattern. You should simply memorize its forms! Please, note an alternation of the letters «т/ч» in the verb’s stem.

Demonstrative Pronouns

To specify an object found in a group of objects, you can use a demonstrative pronoun «этот, эта, это, эти» («this, these»). The demonstrative pronoun has to «agree» in gender and number with the noun denoting the object. With the singular masculine noun, you use «этот»: «этот дом» (this house); with the feminine noun, «эта» is used: «эта комната» (this room); and with the neuter noun, «это»: «это окно» (this window). Plural nouns require the form «эти»: «эти часы» (these clocks). Thus, there are four demonstrative pronoun forms in Russian. The demonstrative pronoun is called for when you point to a specific object you have chosen among several other objects and to answer a question: Какой? (какая? какое? какие?) — «which one?» or «which ones»?

- – Какой телевизор недорогой и хороший?

- – Этот. // Этот телевизор.

- – Какая комната очень удобная?

- – Эта комната.

- – Какое кино очень интересное?

- – Это американское кино.

- – Какие вещи твои?

- – Эти вещи мои.

To answer the question: «What is it?», you can use just one pronoun form «это», and in this case, it does not have to agree with the noun neither in gender, nor in number:

- Это мой дом.

- Это наша удобная квартира.

- Это наше окно.

- Это твои вещи?

A grammar model with the pronoun «это» gives you a complete sentence: «Это дом» (This is a house). Это ваза. Это окно. Это часы. The sentences are very short because in Russian the verb «to be» is not used in the Present Tense. This model is quite different from a phrase with a demonstrative pronoun which requires additional information about the specified object and, thus, requires a predicate to complete a sentence. Compare:

| Что это? | Какой? Какая? Какое? Какие? |

| Это дом. | Этот дом… Этот дом очень большой. Мне нравится этот дом. |

| Это русский сувенир. | –Какой сувенир очень красивый? –Этот русский сувенир очень красивый. |

| Это книга. | –Какая книга тебе нравится? –Мне нравится эта книга. |

| Это пальто. | –Какое пальто самое тёплое? –Это красное пальто самое тёплое. |

| Это часы. | –Какие часы очень хорошие –Эти часы очень хорошие. |

Pay attention to the word order in such sentences.

| Это овощной салат. | Э́тот салат овощной. |

| Это красная рыба. | Э́та рыба красная. |

| Это дорогие закуски. | Э́ти закуски дорогие. |

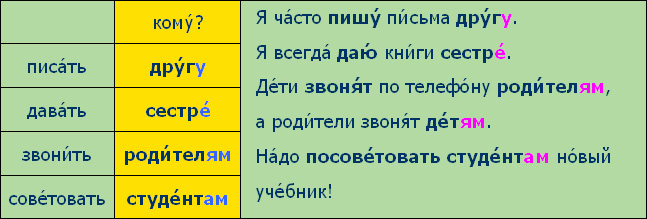

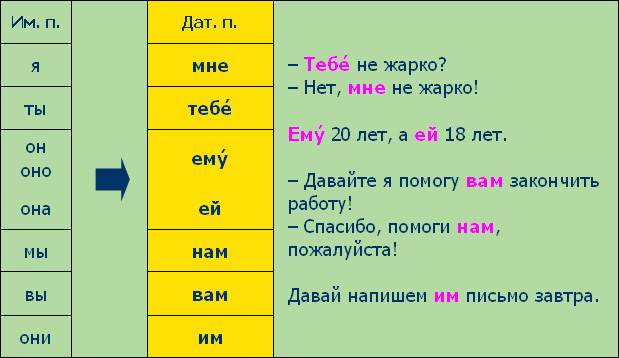

DATIVE CASE

In a sentence the Dative case often indicates an indirect object: a person or object to whom the action is directed.

- Позвони мне!

- Скажи мне!

- Дай мне!

In the Dative case nouns and pronouns answer the questions: To whom? To what?

I LIKE

The construction «Мне нравится… » (I like) or «Мне не нравится…» (I don’t like) is used to express the speaker’s attitude toward an object or action. In this construction a logical subject is expressed by a noun or pronoun in the Dative case while an object is expressed by a noun or pronoun in the Nominative case.

Consider the sentence structure in the following examples:

Attention!The verb form has to agree with the noun in the Nominative case.

Let’s see how you can ask and answer such questions:

- – Тебе́ нра́вятся блины́?

- – Да. // Да, нра́вятся. // Да, мне нра́вятся блины́.

- – Вам нра́вится омле́т?

- – Нет. // Нет, не нра́вится. // Нет, мне не нра́вится омле́т.

To convey an attitude to an action using the construction with the verb «нравиться» (to like), follow the verb «нравиться» (in the form нравится) with the infinitive form of the verb which indicates the action itself:

- Мне нра́вится чи́тать.

- Тебе́ нра́вится обе́дать здесь?

- Ему не нра́вится пить во́ду.

ACCUSATIVE CASE

A noun or pronoun in the Accusative case indicates a direct object. Verbs «читать» (to read), «понимать» (to understand), «to know» (знать), «любить» (to love or like) will be followed by the noun or pronoun in the Accusative case. Nouns or pronouns in the Accusative case answer the question: «what?» or «whom?»

The question «what?» is asked when the inanimate noun serves as an object, and the question «whom?» refers to an object that is either a human being or an animal.

- – Что ты хо́чешь?

- – Я хочу́ сала́т.

- – Кого́ ты зна́ешь?

- – Я зна́ю А́нну.

For inanimate masculine nouns, as well as neuter nouns, the Accusative case endings coincide with the Nominative case endings:

Masculine nouns

Neuter nouns:

However, for feminine nouns both animate and inanimate the Accusative case endings will be different:

Please, note! For masculine and feminine nouns which end in «–Ь», the Accusative case endings stay the same.

To find out how animate masculine noun endings change in the Accusative case, see Lesson 5.

Personal pronouns in the Accusative case have special forms.

Compare:

IMPERATIVE

The Imperative is used to express a request or an order.

There are two Imperative forms in Russian, and the choice of a particular form depends on whom you are addressing:

Imperative forms.

This is how the Imperative forms are constructed:

Please, remember!

If the verb stem ends in a vowel («a», «о», «у», «и», etc.), then the suffix «-Й-» is added to the stem. If the stem ends in a consonant («б»,»в», «г», «д», «ж», etc.), then the suffix «-И-» is added.

Verb: Past Tense

The Past tense is used to describe any action that took place in the past.

«Этот молодой человек раньше не говорил по-русски, а теперь говорит». — «Previously, this young man did not speak Russian but now he does.»

«Маша уже говорила тебе, где можно купить сувениры.» — «Masha told you before where to buy souvenirs.»

To form the Past Tense verbal forms: first, drop the verb Infinitive ending and add to the verb stem the Past tense suffix «-л», then follow the suffix with the ending «-а» for feminine nouns, with the ending «-о» for neuter nouns, and the ending «-и» for plural nouns.

Please, remember! The Past tense verbal form agrees with the noun in gender and number.

Ordinal Numerals.

The first place!

Just as adjectives, ordinal numerals have to agree with nouns in gender, number and case.

Complex sentence with the words «ПОЭТОМУ» (that’s why) и «ПОТОМУ ЧТО» (because)

|

причина Я люблю икру. |

следствие Я ем икру |

| This is a cause. | 2. Here is an effect. |

|

|

Я люблю икру, поэтому я ем икру.

Я ем икру, потому что я люблю икру.

Почему я часто ем икру? – Потому что я люблю её.

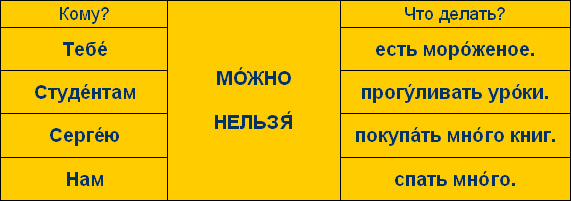

Modal words: рад (glad), уверен (sure), должен (have to), готов (ready), надо / нужно (need)

To convey an attitude to an action or event being talked about, a speaker can use special words: «должен», «рад», «уверен», «готов», «надо/нужно».

The words «рад», «уверен», «готов» are short forms of adjectives. Thus, they agree with nouns or pronouns in gender and number.

Consider the sentence structure in the following examples:

For example:

- «Антон рад видеть Анну в Москве». — «Anton is glad to see Anna in Moscow.»

- «Подруга должна заплатить за квартиру».- «My girl friend has to pay for the apartment».

- «Студенты готовы писать тест». — «The students are ready to write a text.»

BUT!

Я уверен, что видел этот фильм.

Please, remember!

- Мне надо позвонить домой.

- Тебе нужно заплатить за завтрак.

- Вам нужно поменять деньги.

Using adverbs («по-русски» — «in Russian») with verbs «говорить» («to speak») and «понимать» («to understand»).

Accusative Case: Animate Nouns (singular)

In the Accusative case, animate and inanimate masluline nouns have different endings. For inanimate masculine nouns, the Accusative and Nominative case endings are the same (see Grammeer Notes to Lesson 4).

But for masculine animate nouns, these endings will be different.

«Антон и Виктор друзья». — «Anton and Victor are friends.» «Антон знает Виктора, а Виктор знает Антона». — «Anton knows Victor, and Victor knows Anton.»

BUT! In the Accusative case animate feminine singular nouns have the same endings as inanimate ones:

WHEN? DAYS OF THE WEEK

Compare:

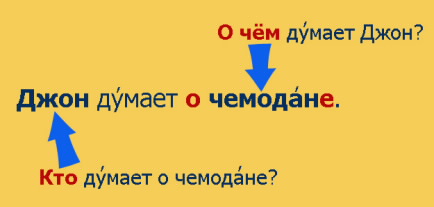

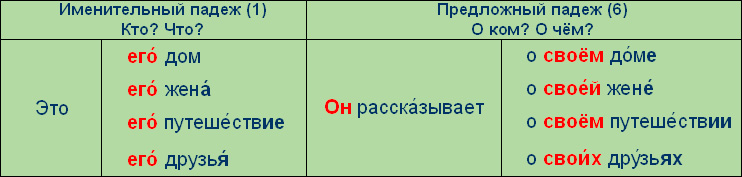

SUBJECT OF THOUGHT OR SPEECH

Prepositional Case with the preposition «О» («about»)

The noun which describes an object of thought or speech must be put in the Preposional case with the preposition «o» (about). Usually, such nouns follow the verbs «говорить» (talk about), «думать» (think about», «рассказывать» (tell about», «помнить» (remember about), etc.

«Джон думает о чемодане и о Марии«. — «John is thinking about his suitcase and about Maria.»

«Джон говорит о Москве«. — «John talks about Moscow.»

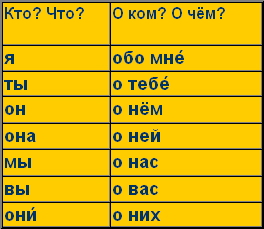

If you need to inquire about a subject of thought or speech, you should start a question with the preposition «О» followed by a pronoun «кто» or «что» in the Prepositional case: О КОМ? О ЧЁМ?

Compare:

Personal pronouns in the Prepositional case have the following forms:

GENITIVE CASE

Expressing absense: Genitive in negative sentenses with the word «НЕТ«.

To express absence of something or somebody, in Russian we use the negative word «НЕТ» (there is no…) + a noun or a pronoun in the Genetive case to indicate what or who is absent or lacking.

| У неё есть собака. | У него нет собаки. |

To put a singular noun in the Genetive case, you have to do the following:

Negative pronouns » НИКТО́» (nobody) and «НИЧТО́» (nothing) have the following Genitive case forms: «НИКОГО́» and «НИЧЕГО́».

POSSESSION: «ЧЕЙ?» (WHOSE?)

In Russian the Genitive case (2) is used to indicate WHO possesses an object (and to answer the question ЧЕЙ? ЧЬЯ? ЧЬЁ? ЧЬИ? — Whose object is it? )

| Это Джон.

Это его рюкзак. Это его газета. |

|

Это Мария.

Это её багаж. Это её визитка. |

|

— Чей роман «Идиот»? — «Идиот» — роман Достоевского. |

2. Description or definition (what?)

The Genitive case is also used to answer the questions: КАКОЙ? КАКАЯ? КАКОЕ? КАКИЕ? (what?)

Какая это улица? – Это улица Чехова.

Какой это театр? – Это Театр оперы и балета.

3. PART AND WHOLE

To describe a certain part of a whole object, the combination of two nouns is often used: the first one indicates a part and the second one, used in the Genitive case, indicates the whole object. For example:

Это центр города.

Париж – столица Франции.

Дай мне стакан воды!

Please, note!

To put such a phrase in a different case, you will need to change the first noun form. But the second noun in the Genitive case will not change. For example:

Вот центр Москвы. В центре Москвы находится Театр оперы и балета. В Театре оперы и балета работают известные артисты.

GENITIVE CASE AFTER NUMERALS

To indicate a precise quantity, we use the construction «a numeral plus a noun».

When there is one object, a noun is always in the Nominative case and a numeral agrees with the noun’s gender:

один час

одна минута

одно такси

If there are more objects than one, the construction «a numeral + a noun in Genitive singular or plural» is used. Please, study the tables.

Please, note! The noun agrees with the last numeral!

20 (двадцать) рублей, долларов

21 (двадцать один) рубль, доллар

22 (двадцать два) рубля, доллара

25 (двадцать пять) рублей, долларов

30 (тридцать) минут

31 (тридцать одна) минута

32 (тридцать две) минуты

35 (тридцать пять) минут

Please, note the word forms: два / две («two»)

два студента, два доллара (2 + существительные мужского рода)

две студентки, две книги (2 + существительные женского рода)

The invariant (never changing) nouns (see the section «Plural Nouns (continued)») do not change their form even when counted.

1 один евро, одно интервью, одно такси

2 (два) евро, интервью, такси

5 (пять) евро, интервью, такси

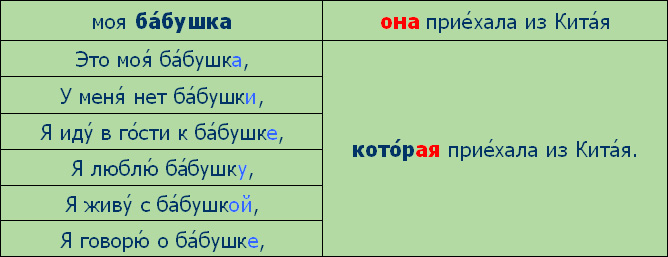

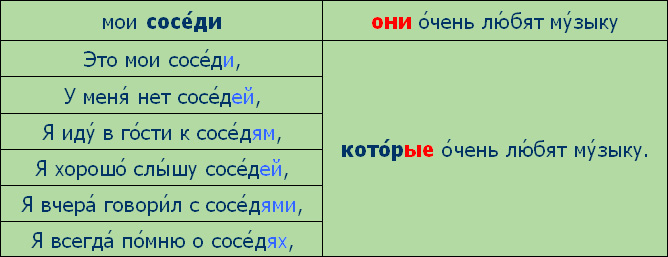

Complex sentence with the word «который» (which, that)

To describe a person or inanimate object (i.e. to answer the question: какой? = what is it like?), we can use a complex sentence with the word «который».

Например:

Это человек. Он меняет деньги.

Какой это человек? – Это человек, который меняет деньги.

Это девушка. Она работает в банке.

Какая это девушка? – Это девушка, которая работает в банке.

The word «который» behaves as an adjective: it is inflected for gender and number to agree with the word it serves as a substitute for.

человек – он – который

девушка – она – которая

люди – они – которые

The same happens when the word «который» serves as a substitute for the inanimate noun:

стол — он — который

книга — она — которая

дерево — оно — которое

книги — они — которые

Please, remember!

The form of the word «который» is determined by its function in a subordinate clause, not in the principal one! Please, consult the tables: the clause that starts with the word «который» doesn’t change, and it can be added to any principal clause from the left column.

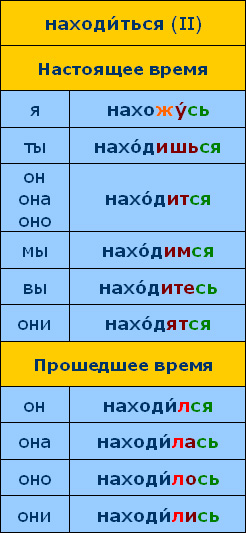

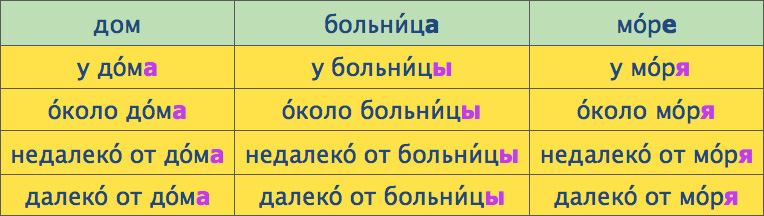

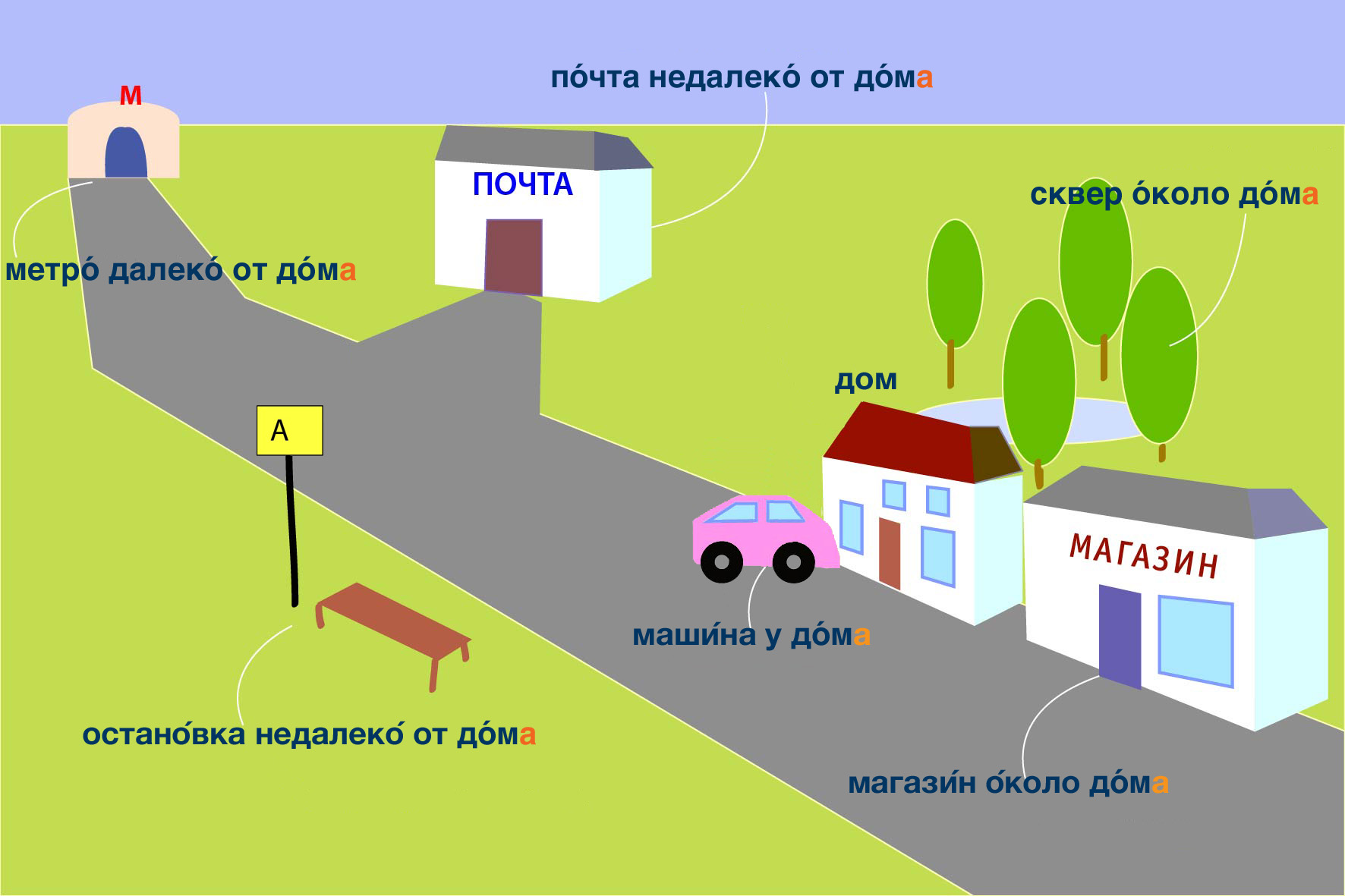

How to describe location of a person or object using the verb “находиться” (=to be located)

In informal speech to describe a location of a person or object, we use simple grammatical models:

Я в кино.

Анна на работе.

Книга на столе.

However, when we want to emphasize the meaning of the phrase, we use the verb НАХОДИ́ТЬСЯ (= to be located).

Президент сейчас нахо́дится в Италии.

Красная площадь нахо́дится в Москве.

Мы сейчас нахо́димся около здания университета.

Sentences with the verb «находиться» sound more formal. Compare: