Do you happen to work in a Russian office or with Russian partners? Do you already know all the words you need to communicate with your Russian colleagues?

If you feel like it would not hurt to increase your Russian office vocabulary, today we offer you a selection of 10 useful Russian words for those working in a office and not only in an office.

At the end of the article you can find a link to the flashcards where you can practice all the words below.

leave of absence, compensatory leave, overtime leave, day off

зарпла́та

[zarpláta]

Noun

, feminine

, short from за́работная пла́та

corporative party, office party

to scheme / intrigue against (usually to take one’s position)

о́фисный планкто́н

[ófeesnyî planktón]

Phrase

office plankton (low motivated office worker)

deal, transaction, bargain

Examples

-

За после́дние два го́да его́ зарпла́та вы́росла в три ра́за.

za paslyédneeye dva góda eevó zarpláta výrasla f tree ráza

Over the past two years, his salary has grown three-fold.

-

На каку́ю зарпла́ту вы рассчи́тываете?

na kakúyu zarplátu vy raschéetyvaeetye

What salary do you expect?

-

Сотру́дники возмути́лись сокраще́нием зарпла́т.

satrúdneekee vazmutéelees’ sakraschyéneeyem zarplát

Employees were outraged by the reduction in salaries.

-

Сто́имость разби́того окна́ вы́чли из его́ зарпла́ты.

stóeemast’ razbéetava akná výchlee eez yevó zarpláty

The cost of the broken window was subtracted from his salary.

-

Могу́ я заня́ть у тебя́ до полу́чки?

magú ya zanyát’ u teebyá da palúchkee

Can I borrow from you until the payday?

-

Полу́чка у нас два ра́за в ме́сяц.

palúchka u nas dva ráza v myésyats

We get paid twice a month.

-

Его́ нет в о́фисе, он в командиро́вке в Ита́лии.

yevó nyet v ófeesye, on f kamandeerófkye v eetáleeee

He is not in the office, he is on a business trip in Italy.

-

Он ча́сто е́здит по командиро́вкам.

on chásta yézdeet pa kamandeerófkam

He often travels on business trips.

-

Послеза́втра я уезжа́ю в командиро́вку.

posleezáftra ya uyezzháyu f kamandeerófku

The day after tomorrow I’m leaving on a business trip.

-

За́втра у нас корпорати́в по слу́чаю дня рожде́ния компа́нии.

záftra u nas karparatéef pa slúchayu dnya razhdyéneeya kampáneee

Tomorrow we have a corporate party on the occasion of the company’s birthday.

-

На нового́днем корпорати́ве он напи́лся так, что не мог ходи́ть.

na navagódnyem karparatéevye on napéelsya tak, chto nye mok hadéet’

At the New Year’s corporate party, he got so drunk that he could not walk.

-

Он сего́дня в отгу́ле.

on seevódnya v atgúlye

He is on leave today.

-

Я хочу́ попроси́ть отгу́л на за́втра.

ya hachú papraséet’ atgúl na záftra

I want to ask for a day off for tomorrow.

-

Когда́ у тебя́ о́тпуск?

kagdá u teebyá ótpusk

When is your vacation?

-

Пе́рвая неде́ля о́тпуска, как ка́жется, прошла́ на одно́м дыха́нии.

pyérvaya needyélya ótpuska, kak kázheetsa, prashlá na adnóm dyháneeee

The first week of vacation seems to have passed in one breath.

-

Че́рез неде́лю я уезжа́ю в о́тпуск на мо́ре.

chéryez nyedyélyu ya uyezzháyu v ótpusk na mórye

In a week I’m going on vacation to the sea.

-

При увольне́нии сотру́днику поло́жена компенса́ция за неиспо́льзованный о́тпуск.

pree uval’nyéneeee satrúdneeku palózheena kampeensátseeya za nyeeespól’zavanyî ótpusk

Upon dismissal, the employee is entitled to a compensation for unused vacation.

-

Мы е́дем в о́тпуск всей семьёй.

my yédeem v ótpusk fsyeî seem’yóî

We go on vacation with the whole family.

-

Вы совсе́м не загоре́ли, весь о́тпуск в но́мере просиде́ли, что-ли?

vy safsyém nye zagaryélee, vyes’ ótpusk v nómeerye praseedyélee, chtólee

You didn’t get tanned at all, did you spent the whole vacation in your room?

-

О́фисный планкто́н — э́то сре́днее о́фисное звено́ с пони́женной тво́рческой составля́ющей.

ófeesnyî planktón éta sryédnyeye ófeesnaye zveenó s panéezhennaî tvórcheeskaî sastavlyáyuschyeî

Office plankton is a middle level office workers with a reduced creative component.

-

Весь наш о́фисный планкто́н прово́дит бо́льше вре́мени в социа́льных сетя́х, чем рабо́тая.

vyes’ nash ófeesnyî planktón pravódeet ból’she vryémeenee v satseeál’nyh seetyáh, chyem rabótaya

All our office plankton spends more time on social networks than working.

-

Перегово́ры зашли́ в тупи́к.

peereegavóry zashlée f tupéek

Negotiations have reached an impasse.

-

Сто́роны се́ли за стол перегово́ров.

stórany syélee za stol peereegavóraf

The parties sat down at the negotiating table.

-

Все счита́ют, что ты подсиде́л Анто́на.

fvsye scheetáyut chto ty padseedyél antóna

Everybody thinks that you intrigued against Anton to take his position.

-

Он пережива́ет, что его́ мо́гут подсиде́ть в компа́нии.

on peereezheeváeet, chto eevó mógut padseedyét’ f kampáneeee

He worries that somebody can scheme against him in the company (to take his position).

-

Два́дцать проце́нтов от су́ммы сде́лки забира́ет себе́ се́рвис.

dvátsat’ pratséntaf at súmmy sdyélkee zabeeráeet seebyé sérvees

The service takes twenty percent of the amount of the transaction.

-

Мы заключи́ли вы́годную сде́лку.

my zaklyuchéelee výgadnuyu sdyélku

We made a good deal.

-

Он не пошёл на сде́лку с со́вестью.

on nye pashól na sdyélku s sóveest’yu

He did not go for a deal with his conscience.

Practice «10 Russian words for those working in an office» with flashcards

Practice with flashcards

You might also like

- Ushanka — Meaning in Russian

- Baba Yaga — Meaning in Russian

- Privet in Russian

- Russian podcast for intermediate and advanced learners

- Russian jokes with translation and audio

- Online Russian school Russificate

There is more to discover

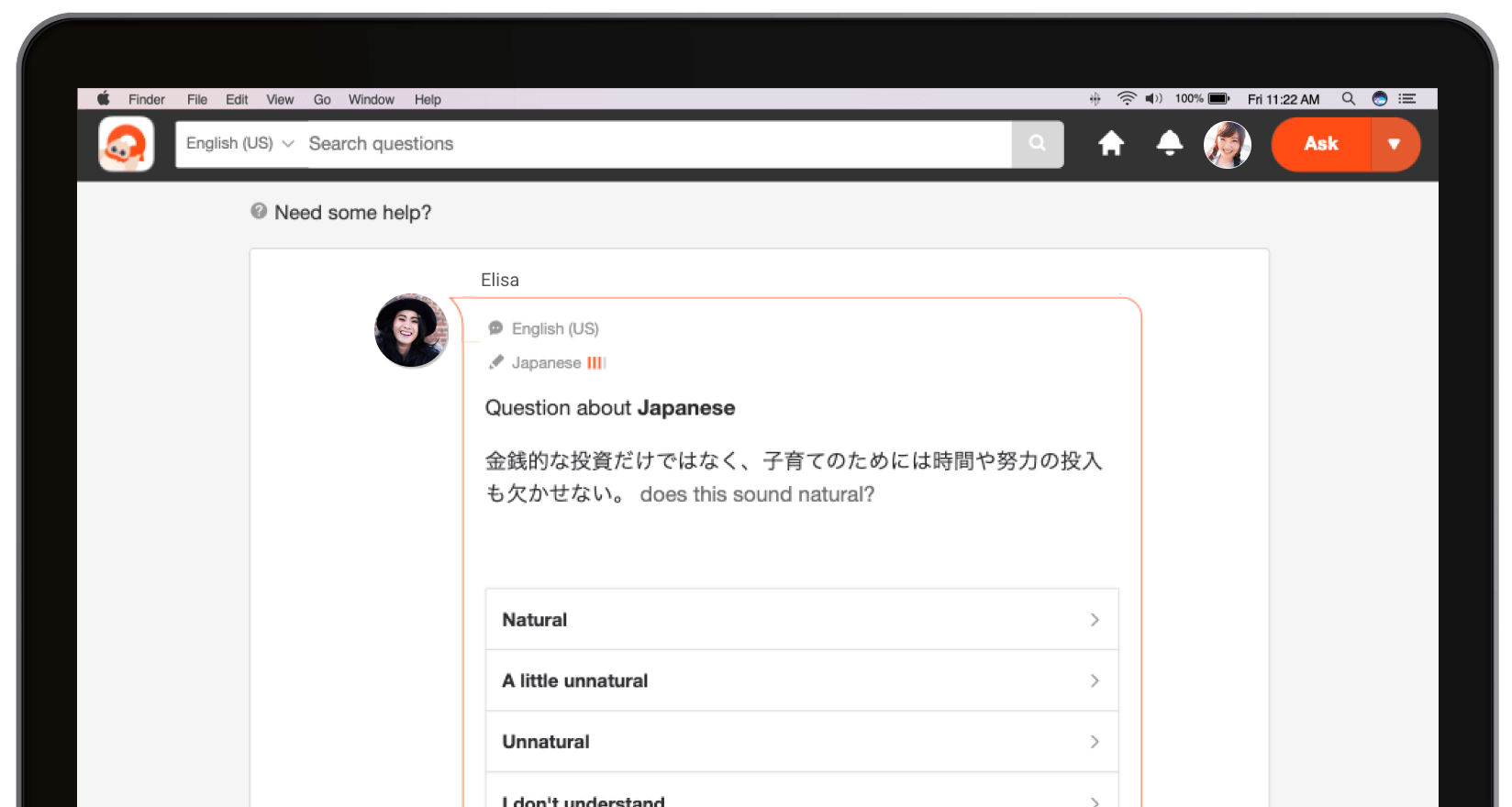

Question

Updated on

15 Aug 2018

-

English (UK)

-

Norwegian (bokmal)

-

Russian

How do you say this in Russian? Russian word for work-out, training etc

How do you say this in Russian? Russian word for work-out, training etc

When you «disagree» with an answer

The owner of it will not be notified.

Only the user who asked this question will see who disagreed with this answer.

-

Russian

-

Russian

Sorry)) удаться, получиться, а не добиваться

-

Russian

Тренироваться, заниматься фитнесом

-

Russian

Work-out is «тренировка»

Work-out (noun) — тренировка.

(verb) — тренироваться.

-

Russian

You can say «качаться» meaning «to work-out» when you’re building muscle

[News] Hey you! The one learning a language!

Do you know how to improve your language skills❓ All you have to do is have your writing corrected by a native speaker!

With HiNative, you can have your writing corrected by native speakers for free ✍️✨.

Sign up

-

I need help pronouncing Russian words

answer

I can suggest engaging in exchanging word pronunciation exercises. I’m interested in English. I can help with the Russian.

-

How do you say this in Russian? Russian idioms and expressions

answer

русские идиомы и выражения

-

is there any places for checking the transform of Russian words?like verb, noun

answer

@stephan2017 https://sklonenie-slov.ru

http://bezbukv.ru/inflect -

How do you say this in Russian? ロシア語で覚えた言葉

answer

Слова, которые я запомнил по-русски

- What is the Russian word ordering? Like in English we have adjectives before nouns. What is that …

-

How do you say this in Russian? 从俄语新闻看俄译汉翻译技巧

answer

Вижу Вы уже понимаете русские новости

-

What does ж. in a Russia dictionary mean?

answer

It means feminine nouns (женский род).

Those words usually end in -a or –я -

How do you say this in Russian? 俄语用俄语怎么说?

answer

«Ты говоришь по-русски?»

- How do you say this in Russian? I don’t like drama (not the movie type, but in relationships)

-

How do you say this in Russian? 私はゲームをしたり稀に絵を描いています。

五十路のおっさんですが、宜しくお願いします。 - How do you say this in Russian? A person can be broken (emotionally, etc.)

- How do you say this in Russian? Я иногда завтракаю утром, но я всегда обедаю днём в кафе.

- How do you say this in Russian? sugar daddy

- How do you say this in English (US)? I hear that in some places, they don’t have toilet paper, so…

-

How do you say this in English (US)? (레스토랑)

여기다 의자두고 먹을수있나요?

죄송하지만 여기다 의자두실수없어요 - How do you say this in English (US)? もし子供が傲慢な態度をしていたら、自分の行動、話し方を見た方がいい。自分でも気付かない悪いところがある。親は子供の鏡です。

- How do you say this in English (US)? 오늘 아까부터 비가 내리고있습니다

- How do you say this in English (US)? 音楽ライブに参加する友達に「楽しんできてね!」

- How do you say this in English (US)? 亲爱的

- How do you say this in English (US)? 당신을 위해 기도할게요

- How do you say this in English (US)? 私は彼に出会ってから、まだ1週間しか経っていない。

- How do you say this in English (US)? 把自己当回事儿

- How do you say this in English (US)? 好啊

Previous question/ Next question

- What does the word ‘Residential weekend’ mean ? Thanks a lot

- What is the difference between run into and run across ?

What’s this symbol?

The Language Level symbol shows a user’s proficiency in the languages they’re interested in. Setting your Language Level helps other users provide you with answers that aren’t too complex or too simple.

-

Has difficulty understanding even short answers in this language.

-

Can ask simple questions and can understand simple answers.

-

Can ask all types of general questions and can understand longer answers.

-

Can understand long, complex answers.

Sign up for premium, and you can play other user’s audio/video answers.

What are gifts?

Show your appreciation in a way that likes and stamps can’t.

By sending a gift to someone, they will be more likely to answer your questions again!

If you post a question after sending a gift to someone, your question will be displayed in a special section on that person’s feed.

Tired of searching? HiNative can help you find that answer you’re looking for.

Have you already mastered the basics of the Russian language? If so, this means you have put in the time and effort to gain an extensive vocabulary and that you can make simple statements with relative ease. Congratulations!

But as they say, you can always do better. You should be proud of the Russian-language proficiency level that you have achieved up to this point, but remember that there is always room for improvement. To reach the advanced level, you’ll need to study more advanced Russian words and make continual progress by working to improve your skills on a daily basis.

Thanks to the global spread of the internet, it has become more convenient than ever to learn Russian online. If you would like to improve your Russian skills even further and learn to use the language exactly like native speakers, then you’re in the right place.

RussianPod101 has compiled this comprehensive list of advanced Russian vocabulary words you’ll need in order to level up. We have included words and example sentences that will definitely allow you to show off your knowledge: academic words, business terms, legal jargon, and alternative “high-end” words to use in place of their simpler counterparts.

Online learning definitely reduces financial strain as it’s far more affordable compared to attending traditional universities or language classes.

Table of Contents

- Advanced Academic Words

- Advanced Business Words

- Advanced Medical Words

- Advanced Legal Words

- Alternative Words for Academic or Professional Writing

- Conclusion

1. Advanced Academic Words

The education systems of the USA, Canada, Australia, and Europe differ significantly from the education system in Russia. In this section of our advanced Russian words list, you’ll find words and phrases in Russian that will be useful to know while studying in Russian schools and universities (and, of course, when speaking with students in Russia). The topic of education is very broad, but the purpose of this list is to provide you with the most relevant words for Russian communication in academic settings.

- Экзамен (Ekzamen) – “Assessment” [noun]

- Сомнительный (Somnitel’nyy) – “Ambiguous” / “Doubtful” [adjective]

- Дискуссия (Diskussiya) – “Discussion” [noun]

- Сессия (Sessiya) – “Examinations” [noun]

- Диплом (Diplom) – “Diploma” [noun]

Example Sentences:

Сомнительно, что она сдаст экзамен.

Somnitel’no, chto ona sdast ekzamen.

“It is doubtful that she will pass the exam.”

После показа фильмов проводилась тематическая дискуссия.

Posle pokaza fil’mov provodilas’ tematicheskaya diskussiya.

“Each showing of the documentary was followed by a panel discussion.”

После удачной сдачи сессии он получил диплом.

Posle udachnoy sdachi sessii on poluchil diplom.

“After successfully passing the examinations, he received a diploma.”

Over four million students were enrolled in Russian institutions of higher education in 2019.

- Лекция (Lektsiya) – “Lecture” [noun]

- Урок (Urok) – “Lesson” [noun]

На лекциях и уроках получают знания.

Na lektsiyakh i urokakh poluchayut znaniya.

“We gain knowledge at lectures and lessons.”

- Химический (Khimicheskiy) – “Chemical” [adjective]

- Принципы (Printsipy) – “Foundations” / “Basis” [noun]

Принципы химических реакций

Printsipy khimicheskikh reaktsiy

“Foundations of chemical reactions”

- Методическое пособие (Metodicheskoye posobiye) – “Guideline” [the word пособие is a noun and методическое is an adjective]

- Обнаружить (Obnaruzhit’) – “To detect” [verb]

- Случайно (Sluchayno) – “Randomly” / “Accidentally” [adverb]

- Приложение (Prilozheniye) – “Appendix” [noun]

Он случайно обнаружил приложение к методическому пособию.

On sluchayno obnaruzhil prilozheniye k metodicheskomu posobiyu.

“He accidentally discovered an appendix to the guideline.”

- Таблица (Tablitsa) – “Chart” / “Table” [noun]

Таблица является полезным инструментом.

Tablitsa yavlyayetsya poleznym instrumentom.

“The chart is a useful tool.”

- Кругозор (Krugozor) – “Prospect” / “Horizons” [noun]

У него широкий кругозор.

U nego shirokiy krugozor.

“He has broad horizons.”

- Абзац (Abzats) – “Paragraph” [noun]

Абзац форматируется как заголовок.

Abzats formatiruyetsya kak zagolovok.

“A paragraph is formatted as a heading.”

- Решающий (Reshayushchiy) – “Crucial” [adjective]

- Ядерный (Yаdernyy) – “Nuclear” [adjective]

Первым пунктом повестки дня должна стать ратификация улучшений решающего инструмента обеспечения ядерной безопасности.

Pervym punktom povestki dnya dolzhna stat’ ratifikatsiya uluchsheniy reshayushchego instrumenta obespecheniya yadernoy bezopasnosti.

“At the top of the agenda should be the ratification of improvements to a crucial nuclear security instrument.”

- Расписание (Raspisaniye) – “Schedule” / “Timetable” [noun]

- Минимальный (Minimal’nyy) – “Minimum” [adjective]

Студенты получили ориентировочное расписание с минимальным количеством занятий.

Studenty poluchili oriyentirovochnoye raspisaniye s minimal’nym kolichestvom zanyatiy.

“Students received an indicative timetable with a minimum number of classes.”

- Ориентировочный (Oriyentirovochnyy) – “Preliminary” / “Approximate” [adjective]

- Общежитие (Obshchezhitiye) – “Dormitory” [noun]

В общежитии был беспорядок.

V obshchezhitii byl besporyadok.

“The dormitory was a mess.”

- Формат (Format) – “Format” [noun]

Сдайте работу в формате pdf.

Sdayte rabotu v formate pdf.

“Submit your work in PDF format.”

- Среда (Sreda) – “Medium” [noun]

Питательная среда содержит лактопептон.

Pitatel’naya sreda soderzhit laktopepton.

“The nutrition medium contains lactopeptine.”

- Продолжительность (Prodolzhitel’nost’) – “Duration” [noun]

Продолжительность занятия — 30 минут.

Prodolzhitel’nost’ zanyatiya — 30 minut.

“The duration of the lesson is 30 minutes.”

- Убеждённый (Ubezhdyonnyy) – “Convinced” [adjective]

Убеждённый европеец, он рассматривал европейский идеал строго в рамках международного сотрудничества.

Ubezhdyonnyy yevropeyets, on rassmatrival yevropeyskiy ideal strogo v ramkakh mezhdunarodnogo sotrudnichestva.

“A convinced European, he set the European ideal squarely in a framework of international cooperation.”

2. Advanced Business Words

Business vocabulary is not limited to business contexts; many of the advanced Russian words presented below are used in ordinary everyday conversations as well. While going through this list, keep in mind that each specialty requires a specific vocabulary set. Daily meetings with colleagues, negotiations with business partners, communication by phone and email—all these things require a special skill set and a specific set of vocabulary.

- Стратегия (Strategiya) – “Strategy” [noun]

- Встречное предложение (Vstrechnoye predlozheniye) – “Counteroffer” [noun]

Встречное предложение партнёра было частью запасной стратегии.

Vstrechnoye predlozheniye partnyora bylo chast’yu zapasnoy strategii.

“The partner’s counteroffer was part of a fallback strategy.”

- Фискальный (Fiskal’nyy) – “Fiscal” [adjective]

Бухгалтерский и налоговый учёт фискального накопителя

Bukhgalterskiy i nalogovyy uchyot fiskal’nogo nakopitelya

“Accounting and tax accounting of the fiscal driver”

- Сотрудничество (Sotrudnichestvo) – “Collaboration” / “Cooperation” [noun]

- Соглашение / Договор (Soglasheniye / Dogovor) – “Agreement” [noun]

Частью сотрудничества является подписание договора.

Chast’yu sotrudnichestva yavlyayetsya podpisaniye dogovora.

“Part of cooperation is the signing of an agreement.”

- Бюджет (Byudzhet) – “Budget” [noun]

Бюджет академии увеличился на 11 процентов.

Byudzhet akademii uvelichilsya na 11 protsentov.

“The budget for the academy was raised by 11 percent.”

Russia was the sixth-largest economy in the world in 2019, the World Bank estimates. In nominal terms, Russia ranks eleventh.

- Бухгалтер (Bukhgalter) – “Accountant” [noun]

- Отдел (Otdel) – “Department” [noun]

- Визитка (Vizitka) – “Business card” [noun]

На визитке бухгалтера был указан его отдел.

Na vizitke bukhgaltera byl ukazan yego otdel.

“The accountant’s business card indicated his department.”

- Валюта (Valyuta) – “Currency” [noun]

- Товар (Tovar) – “Commodity” [noun]

- Покупатель (Pokupatel’) – “Customer” [noun]

Покупатель купил товар за валюту.

Pokupatel’ kupil tovar za valyutu.

“The buyer bought the product with foreign currency.”

- Эффективность (Effektivnost’) – “Efficiency” [noun]

Отдел повысил показатели эффективности.

Otdel povysil pokazateli effektivnosti.

“The department has improved efficiency indicators.”

- Упаковочный лист (Upakovochnyy list) – “Packing list” [the word лист is a noun and упаковочный is an adjective]

- Срок (Srok) – “Deadline” / “Time” [noun]

- Счёт (Schyot) – “Invoice” [noun]

Срок поставки по счёту и упаковочному листу — сегодня.

Srok postavki po schyotu i upakovochnomu listu — segodnya.

“The invoice and packing list delivery time is today.”

- Инвестиции (Investitsii) – “Investment” [noun]

- Директор (Direktor) – “Managing director” [noun]

- Переговоры (Peregovory) – “Negotiation” [noun]

Директор провёл переговоры, касающиеся инвестиций.

Direktor provyol peregovory, kasayushchiyesya investitsiy.

“The managing director negotiated investments.”

- Вакансия (Vakansiya) – “Opening” / “Vacancy” [noun]

Вакансия руководителя этого проекта заполнена.

Vakansiya rukovoditelya etogo proekta zapolnena.

“The leadership vacancy on this project has been filled.”

- Прибыльный (Pribyl’nyy) – “Profitable” [adjective]

- Заказ (Zakaz) – “Purchase order” [noun]

Компания выполнила прибыльный заказ.

Kompaniya vypolnila pribyl’nyy zakaz.

“The company has completed a profitable order.”

- Резюме (Rezyume) – “Resumé” / “Curriculum vitae” [noun]

Я отправила моё резюме на вакантные места.

Ya otpravila moyo rezyume na vakantnyye mesta.

“I sent my resumé for a few job openings.”

- Подпись (Podpis’) – “Signature” [noun]

Подпись не нужна, только инициалы.

Podpis’ ne nuzhna, tol’ko initsialy.

“You don’t have to sign it; just your initials.”

- Поставка (Postavka) – “Supply” [noun]

- Налог (Nalog) – “Tax” [noun]

Поставка не облагается налогом.

Postavka ne oblagayetsya nalogom.

“The supply is tax-deductible.”

- Сделка (Sdelka) – “Transaction” / “Deal” [noun]

Сделка была прибыльной.

Sdelka byla pribyl’noy.

“The deal was profitable.”

3. Advanced Medical Words

Imagine that you’re in Russia when you start to feel unwell. To get the help you need, you’ll have to describe your symptoms and overall condition (knowing a little about the Russian health system would help, too). In this section, we’ll introduce you to the most useful advanced Russian words related to healthcare.

- Биопсия (Biopsiya) – “Biopsy” [noun]

Эндометриальная биопсия нужна, чтобы проверить эффективность прививки.

Endometrial’naya biopsiya nuzhna, chtoby proverit’ effektivnost’ privivki.

“An endometrial biopsy is needed to test the vaccine efficacy.”

- Деменция (Dementsiya) – “Dementia” [noun]

Совет фонда считает, что у меня деменция.

Sovet fonda schitayet, chto u menya dementsiya.

“The foundation board thinks I have dementia.”

- Ординатура (Ordinatura) – “Residency” [noun]

Мне так сильно понравилась ординатура, что я прошёл её дважды.

Mne tak sil’no ponravilas’ ordinatura, chto ya proshyol yeyo dvazhdy.

“I liked residency so much that I did it twice.”

- Заболевание (Zabolevaniye) – “Disease” / “Illness” [noun]

Заболевание является серьёзным тормозом для развития.

Zabolevanie yavlyayetsya ser’yoznym tormozom dlya razvitiya.

“The disease is a major problem for development.”

- Рецепт (Retsept) – “Prescription” [noun]

Врач выписал мне рецепт.

Vrach vypisal mne retsept.

“The doctor wrote me a prescription.”

Health is one of the crucial things in life that money can’t buy. Please, stay healthy!

- Астма (Astma) – “Asthma” [noun]

Ну, у её дочери астма.

Nu, u yeyo docheri astma.

“Well, her daughter has asthma.”

- Зависимость (Zavisimost’) – “Addiction” [noun]

Ричардс лечился от алкогольной зависимости в 2006 году.

Richards lechilsya ot alkogol’noy zavisimosti v 2006 godu.

“Richards was in rehab for alcohol addiction in 2006.”

- Поликлиника (Poliklinika) – “Outpatient department” [noun]

Поликлиника была создана для диагностики.

Poliklinika byla sozdana dlya diagnostiki.

“The outpatient department was set up to provide diagnostic care.”

- Медицинский центр (Meditsinskiy tsentr) – “Health care center” [the word центр is a noun and медицинский is an adjective]

- Cтоматологический (Stomatologicheskiy) – “Dental” [adjective]

Стоматологические клиники и медицинские центры в России могут быть частными.

Stomatologicheskiye kliniki i meditsinskiye tsentry v Rossii mogut byt’ chastnymi.

“Dental clinics and medical centers in Russia can be private.”

- Медицинский полис (Meditsinskiy polis) – “Health insurance certificate” [the word полис is a noun and медицинский is an adjective]

Медицинский полис будет только через месяц.

Meditsinskiy polis budet tol’ko cherez mesyats.

“The health insurance certificate will be ready in a month.”

- Приёмный покой (Priyomnyy pokoy) – “Emergency room” [the word покой is a noun and приёмный is an adjective]

- Больничная палата (Bol’nichnaya palata) – “Hospital ward” [the word палата is a noun and больничная is an adjective]

В приёмном покое много больничных палат.

V priyomnom pokoye mnogo bol’nichnykh palat.

“There are many hospital wards in the emergency room.”

- Операционная (Operatsionnaya) – “Operating room” [noun]

- Реанимация (Reanimatsiya) – “Intensive care unit” [noun]

- Пациент, больной (Patsiyent, bol’noy) – “Patient” [noun]

Из операционной пациента перевели в реанимацию.

Iz operatsionnoy patsiyenta pereveli v reanimatsiyu.

“The patient was transferred from the operating room to the intensive care unit.”

- Стационарный больной (Statsionarnyy bol’noy) – “Inpatient” [the word больной is a noun and стационарный is an adjective] Please note that the word больной can also be used as an adjective, just as “patient” can be a noun or an adjective in English.

- Амбулаторный больной (Ambulatornyy bol’noy) – “Outpatient” [the word больной is a noun and амбулаторный is an adjective]

- Медсестра (Medsestra) – “Nurse” [noun]

- Терапевт (Terapevt) – “Physician” [noun]

- Отоларинголог (Otolaringolog) – “ORT specialist” [noun]

Медицинское обслуживание стационарных и амбулаторных больных осуществляется разными группами докторов и медсестёр, в том числе терапевтами и отоларингологами.

Meditsinskoye obsluzhivaniye statsionarnykh i ambulatornykh bol’nykh osushchestvlyayetsya raznymi gruppami doktorov i medsestyor, v tom chisle terapevtami i otolaringologami.

“Medical services for inpatient and outpatient care are provided by various groups of doctors and nurses, including physicians and ORT specialists.”

- Записаться на приём (Zapisat’sya na priyom) – “To make an appointment” [verb]

Записаться на приём было очень сложно.

Zapisat’sya na priyom bylo ochen’ slozhno.

“It was very difficult to make an appointment with a doctor.”

According to statistics, more than half of Russians trust alternative and complementary medicine. Previously, only old ladies knew and shared amongst themselves all the recipes of alternative medicine; now, these recipes can be found on TV and the internet. Healing properties are attributed to herbal tinctures, the steam of boiled potatoes, and other methods of alternative medicine. Here are some advanced Russian words related to complementary medicine:

- Народная медицина (Narodnaya meditsina) – “Alternative medicine” / “Complementary medicine” [the word медицина is a noun and народная is an adjective]

- Грелка (Grelka) – “Hot water bottle” [noun]

- Горчичник (Gorchichnik) – “Mustard plaster” [noun]

- Отвар (Otvar) – “Brew” [noun]

- Целебные травы (Tselebnyye travy) – “Medicinal herbs” [the word травы is a noun (plural of трава – “herb”) and целебные is an adjective]

Отвар из целебных трав, горчичники и грелка являются популярными средствами в народной медицине.

Otvar iz tselebnykh trav, gorchichniki i grelka yavlyayutsya populyarnymi sredstvami v narodnoy meditsine.

“Medicinal herb brews, mustard plasters, and a hot water bottle are popular remedies in alternative medicine.”

4. Advanced Legal Words

While these legal words and phrases may be long, difficult to remember, and even harder to spell, they’re sure to prove useful in a number of contexts. Memorize these advanced Russian words to get a leg up in the business world and to enrich your personal life (these are words you might find used on news stations and in the paper).

- Гражданин (Grazhdanin) – “Passport holder” / “Resident” [noun]

- Закон (Zakon) – “Law” [noun]

- Нарушать закон (Narushat’ zakon) – “To break the law” [verb]

Граждане не должны нарушать закон.

Grazhdane ne dolzhny narushat’ zakon.

“Residents must not break the law.”

- Тяжба (Tyazhba) – “Lawsuit” [noun]

- Юрисконсульт (Yuriskonsul’t) – “Legal adviser” [noun]

- Законный представитель (Zakonnyy predstavitel’) – “Legal representative” [the word представитель is a noun and законный is an adjective]

Законный представитель и юрисконсульт помогут с судебными тяжбами.

Zakonnyy predstavitel’ i yuriskonsul’t pomogut s sudebnymi tyazhbami.

“A legal representative and a legal adviser will help with filing a lawsuit.”

- Нотариус (Notarius) – “Notary public” [noun]

Нотариус проверяет чистоту сделки и следит за тем, чтобы недвижимость продавалась свободной от долгов.

Notarius proveryayet chistotu sdelki i sledit za tem, chtoby nedvizhimost’ prodavalas’ svobodnoy ot dolgov.

“A notary public verifies the purity of a deal and ensures that property is sold free of debts.”

- Бездействие (Bezdeystviye) – “Omission” / “Nonfeasance” [noun]

Такие нарушения могут иметь место в силу действия или бездействия государства.

Takiye narusheniya mogut imet’ mesto v silu deystviya ili bezdeystviya gosudarstva.

“Such violations can occur by state action or omission.”

- Юрист (Yurist) – “Lawyer” [noun]

- Суд (Sud) – “Court” [noun]

- Спорить (Sporit’) – “To dispute” [verb]

Юрист оспорил это решение в суде.

Yurist osporil eto resheniye v sude.

“The lawyer disputed this decision in court.”

The Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation is the highest judicial body of constitutional supervision in the Russian Federation.

- Мошенничество (Moshennichestvo) – “Fraud” [noun]

- Прокурор (Prokuror) – “Prosecutor” [noun]

Прокурор предъявил обвинение в мошенничестве.

Prokuror pred’yavil obvineniye v moshennichestve.

“The prosecutor indicted for fraud.”

- Обжалование (Obzhalovaniye) – “Appeal” [noun]

- Виновный (Vinovnyy) – “Liable” / “Guilty” [adjective]

- Обвинительное заключение (Obvinitel’noye zaklyucheniye) – “Indictment” [the word заключение is a noun and обвинительное is an adjective]

Виновный обжаловал обвинительное заключение.

Vinovnyy obzhaloval obvinitel’noye zaklyucheniye.

“The person found guilty appealed against the indictment.”

- Судебное постановление (Sudebnoye postanovleniye) – “Injunction” [the word постановление is a noun and судебное is an adjective]

Это судебное постановление у нас в кармане.

Eto sudebnoye postanovleniye u nas v karmane.

“This injunction is in the bag.”

- Правосудие (Pravosudiye) – “Justice” / “Justice systems” [noun]

- Приговор (Prigovor) – “Verdict” / “Sentence” [noun]

В то же время женщины теряют доверие к системе правосудия, если приговоры минимальны и не обеспечивают им какую-либо защиту.

V to zhe vremya zhenshchiny teryayut doveriye k sisteme pravosudiya, yesli prigovory minimal’ny i ne obespechivayut im kakuyu-libo zashchitu.

“At the same time, women lose faith in justice systems where sentences are minimal and fail to offer them any protection.”

- Свидетель (Svidetel’) – “Witness” [noun]

Свидетель видел золотой рисунок.

Svidetel’ videl zolotoy risunok.

“The witness saw a gold stripe.”

- Правоотношение (Pravootnosheniye) – “Legal arrangement” / “Legal relation” [noun]

Ссылка на конкретное правоотношение может не вполне подходить для некоторых правовых систем.

Ssylka na konkretnoye pravootnosheniye mozhet ne vpolne podkhodit’ dlya nekotorykh pravovykh sistem.

“The reference to a defined legal relationship might not easily be accommodated in certain legal systems.”

- Права человека (Prava cheloveka) – “Human rights” [noun]

Права человека также являются основой внешней политики.

Prava cheloveka takzhe yavlyayutsya osnovoy vneshney politiki.

“Human rights also constitute one of the key pillars of foreign policy.”

5. Alternative Words for Academic or Professional Writing

To write a really good essay, you need to have a sufficient vocabulary of advanced Russian words. Developing the necessary language skills for writing a persuasive argument is crucial. In this section, we’ll equip you with the words and phrases you’ll need to write a great essay or to compose other forms of academic/professional writing. We have also included a number of advanced Russian words that are hard to pronounce, long, or hyphenated.

Alternative Words

In the first column, you’ll find a simple Russian word; in the second column, you’ll find a more advanced or nuanced replacement you could use instead.

| поэтому (poetomu) – “so” Conjunction |

таким образом (takim obrazom) – “therefore” Conjunction |

| Таким образом, курс рубля повысился. Takim obrazom, kurs rublya povysilsya. “Therefore, the ruble has been appreciated.” |

| большой (bol’shoy) – “big” Adjective |

огромный (ogromnyy) – “huge” / “enormous” Adjective |

| Это огромный успех. Eto ogromnyy uspekh. “This is a huge success.” |

| любить (lyubit’) – “to love” Verb |

обожать (obozhat’) – “to adore” Verb |

| Я обожаю этот сериал. Ya obozhayu etot serial. “I adore this show.” |

| хорошо (khorosho) – “good” Adjective |

прекрасно / замечательно (prekrasno / zamechatel’no) – “beautiful” / “wonderful” Adjective |

| Это прекрасно, просто замечательно. Eto prekrasno, prosto zamechatel’no. “It’s wonderful, just beautiful.” |

Complex Linking Words

- Для того чтобы (Dlya togo chtoby) – “For the purpose of” / “In order to”

This linking word can be used to introduce an explanation.

Example:

Нужно прийти домой пораньше, для того чтобы успеть сделать уроки.

Nuzhno priyti domoy poran’she, dlya togo chtoby uspet’ sdelat’ uroki.

“You need to come home early in order to have time to do your homework.”

- Другими словами / Иными словами (Drugimi slovami / Inymi slovami) – “In other words”

Use the linking word другими словами or иными словами when you want to express something more simply so that it’s easier to understand, or to emphasize or expand upon a point of view.

Example:

Иными словами, он переживает кризис.

Inymi slovami, on perezhivayet krizis.

“In other words, he is in a state of crisis.”

Complicated Words for Russian Learners

Are you up for a challenge? Then try memorizing a few of these more complicated Russian words for advanced learners!

- Подбираться, подкрадываться (Podbirat’sya, podkradyvat’sya) – “To sneak up” / “To creep up” [verb]

Он подобрался незаметно.

On podobralsya nezametno.

“He crept up unnoticed.”

- Растеряться (Rasteryat’sya) – “To become confused” [verb]

- Вдобавок (Vdobavok) – “In addition” [adverb]

Я растерялась и вдобавок забыла, что хотела сказать.

Ya rasteryalas’ i vdobavok zabyla, chto khotela skazat’.

“I was confused and, in addition, forgot what I wanted to say.”

- Неудовлетворённость (Neudovletvoryonnost’) – “Discontent” [noun]

Они вечно показывали неудовлетворённость работой.

Oni vechno pokazyvali neudovletvoryonnost’ rabotoy.

“They were forever discontent with work.”

- Правописание (Pravopisaniye) – “Spelling” [noun]

Одно ясно — его правописание оставляет желать лучшего.

Odno yasno — yego pravopisaniye ostavlyayet zhelat’ luchshego.

“One thing is certain—his spelling leaves much to be desired.”

- Самообладание (Samoobladaniye) – “Self-control” [noun]

Самообладание очень важно в любом обществе.

Samoobladaniye ochen’ vazhno v lyubom obshchestve.

“Self-control is crucial to any society.”

- Приспосабливаться (Prisposablivat’sya) – “To adapt” [verb]

Эти голограммы способны учиться и приспосабливаться.

Eti gologrammy sposobny uchit’sya i prisposablivat’sya.

“These holograms have the ability to learn and adapt.”

- Орудовать (Orudovat’) – “To work by tool” / “To wield” [verb]

Я даже не знаю, как орудовать ножом.

Ya dazhe ne znayu, kak orudovat’ nozhom.

“I wouldn’t even know how to wield a knife.”

- Махнуть рукой (Makhnut’ rukoy) – “To give up” / “A lost cause” [verb]

А ты, на тебя можно махнуть рукой.

A ty, na tebya mozhno makhnut’ rukoy.

“You, however—you’re a lost cause.”

- Истолковывать (Istolkovyvat’) – “To interpret” / “To translate” [verb]

- Ненадлежащий (Nenadlezhashchiy) – “Improper” [adjective]

Ненадлежащее поведение и поступки можно оценивать и истолковывать по-разному.

Nenadlezhashcheye povedeniye i postupki mozhno otsenivat’ i istolkovyvat’ po-raznomu.

“Improper behavior and conduct can be appraised and interpreted in different ways.”

- Несподручно (Nespodruchno) – “Awkwardly” / “Inconveniently” / “Uncomfortably” [colloquialism] [adverb]

В смысле… для меня это, как бы, несподручно.

V smysle… dlya menya eto, kak by, nespodruchno.

“I mean, I’m not comfortable with that.”

Hyphenated Words

In the Russian language, compound words are often hyphenated. These words include compound nouns, compound names, the names of compass points, shades of color, and so on. Here are some examples:

- Северо-восточный (Severo-vostochnyy) – “Northeast” [adjective]

Подул северо-восточный ветер.

Podul severo-vostochnyy veter.

“The northeast wind blew.”

- Фруктово-ягодный (Fruktovo-yagodnyy) – “With/made from fruits and berries” [adjective]

- Изумрудно-зелёный (Izumrudno-zelyonyy) – “Emerald-green” [adjective]

Это был фруктово-ягодный изумрудно-зелёный джем.

Eto byl fruktovo-yagodnyy izumrudno-zelyonyy dzhem.

“It was a fruit and berry emerald-green jam.”

- Диван-кровать (Divan-krovat’) – “Convertible sofa bed” [noun]

- Купля-продажа (Kuplya-prodazha) – “Buy/sell” / “Sale and purchase” [noun]

Фирма занималась куплей-продажей диванов-кроватей.

Firma zanimalas’ kupley-prodazhey divanov-krovatey.

“The company was engaged in the sale and purchase of sofa beds.”

- Мало-помалу (Malo-pomalu) – “Little by little” [adverb]

Мало-помалу каждая часть головоломки становится на своё место.

Malo-pomalu kazhdaya chast’ golovolomki stanovitsya na svoyo mesto.

“Little by little, every piece of the jigsaw is falling into place.”

- Перекати-поле (Perekati-pole) – “Rolling stone” [noun]

Потому что ты и я, мы — перекати-поле.

Potomu chto ty i ya, my — perekati-pole.

“Cause you and I, we’re rolling stones.”

6. Conclusion

In this article, you have learned more than 100 new advanced Russian words and phrases that will help you improve and enrich your Russian vocabulary.

RussianPod101.com has plenty of resources designed to help you reach your Russian learning goals, no matter your current proficiency level. If you’re feeling confident, we recommend creating your free lifetime account today and checking out our advanced Russian course.

In case you found this topic a bit difficult to grasp on your own, you can upgrade to Premium PLUS in order to use our MyTeacher service. A personal tutor will gladly help you memorize and use new Russian words and phrases, provide you with personalized assignments, and more!

Before you go: Which of the above words and phrases do you find most useful? Please, let us know in the comments.

The Most Used Russian Words

This lesson will introduce the most used words in Russian in the order that they are most used. This lesson is a vocabulary lesson to help you learn a number of Russian words that you will use almost every day while you are in Russia.

Many of these words you will already know from previous lessons. Visit the vocabulary page to see the words in list form.

The examples included in this lesson are quite advanced. You will not understand all of the grammar, there are some concepts that you have not been taught. The main thing is to learn the 100 words in this lesson. From this lesson and onwards we will use more complex examples to help you passively learn more Russian vocabulary. You are not expected to memorise all the new Russian words.

1: И — And

Russian’s most used word is ‘и’ (and). ‘И’ is preceded by comma when it is used as a conjuction to join phrases with different subjects. Here are some examples of it in use.

| Кофе с молоком и с сахаром | Coffee with milk and sugar. |

| Московский Кремль и Красная площадь | The Moscow Kremlin and Red Square. |

| Она соединяет Москву и Владивосток | It connects Moscow and Vladivostok. |

| Берите бумагу и пишите. | Take some paper and write. |

| Дети сели на ковер и начали играть. | The children sat down on the carpet and began playing. |

| Он прыгнул в реку и быстро поплыл к острову. | He jumped into the river and quickly swam to the island. |

| Все пели и танцевали. | Everyone was singing and dancing. |

| Озера и горы Шотландии очень красивые. | The lakes and mountains of Scotland are very beautiful. |

| Она подошла к доске, взяла мел и начала писать на доске. | She went up to the blackboard, took the chalk and began writing on the blackboard. |

When it is used like «и … и» it can mean «both … and».

| Она и красива и умна. | She’s both beautiful and clever. |

2: В (Во) — In, into, to

‘В’ means ‘in’ when followed by the prepositional case. Refer to lesson 8 for more information). ‘В’ is pronounced as though it is part of the following word. Sometimes this is difficult to say so ‘Во’ is used instead. ‘Во’ usually proceeds words that start with ‘в’ or a group consonants that are difficult to pronounce.

| Я живу в Москве. | I live in Moscow. |

| Я работаю в школе. | I work at (in) a school. |

| Вчера мы были в театре. | Yesterday we were at the theatre. |

| Мы собрали в лесу много грибов. | We gathered many mushrooms in the forest. |

| Он прилетел в Лондон сегодня утром. | He arrived in London this morning. |

| В городе было очень жарко и мы решили поехать за город. | In town it was very hot, we decided to go to the country. |

| Позавчера мы были в парке. | The day before yesterday we were in the park. |

When followed by the accusative case it means ‘to’ or ‘into’. This is common following verbs of motion because there is a sense of direction.

| Мы едем в Москву. | We are going to Moscow. |

| Завтра мы едем в Лондон. | Tomorrow we are going to London. |

| Я пошел во двор. | I went into the garden. |

| Наша бабушка обычно ходит в магазин утром. | Our grandmother usually goes to the shop in the morning. |

| Сэм ходит в школу пешком каждое утро. | Sam goes to school every morning on foot. |

| Он вошел в институт, когда начался дождь. | Не went into the institute when rain started. |

| Было жарко, но когда мы вошли в лес стало прохладно. | It was hot, but when we went into the forest, it became cool. |

Is used with expressions of time such as ‘on Monday’. (Note: ‘по’ is used when the days are plural ‘on Mondays’)

| В понедельник. | On Monday. |

| Во вторник я читал газету. | On Tuesday I read the newspaper. |

| В пятницу я играю в теннис. | On Friday I am playing tennis. |

| В полдень мы обедали и отдыхали. | At noon we had dinner and rested. |

| В декабре мы пьем водку | In December we drink Vodka |

| В прошлом году мы купили квартиру | Last year we bought an apartment |

3: Не — Not

The word ‘не’ is used for negation. It usually precedes the verb it negates.

| Я не знаю | I don’t know |

| Надя не любит вино | Nadya doesn’t like wine. |

| Она тебе не нравится? | Don’t you like her? |

| Я сказал тебе не делать этого. | I told you not to do that. |

| Мне не было ее жалко. | I didn’t feel sorry for her. |

| Они сказали, чтобы я не волновался. | They told me not to worry. |

| Раньше не все дети имели возможность для дошкольного образования. | Previously, not all children had access to preschool education. |

When negative words are used such as никто (noone), ничто (nothing), никуда (nowhere (motion)), The word ‘не’ is often used.

To the English speaker this looks like a double negative, but this is normal in Russian.

| Я ничего не вижу. | I see nothing. |

| Никто не знает. | Nobody knows. |

| Я никуда не хожу. | I am not going anywhere. |

The follow phrase is occasionally used in response to ‘thank-you’.

| Не за что. | Don’t mention it. (in response to ‘thank-you’) |

4: На — On, at, to

‘На’ means ‘on’ or ‘at’ when followed by the prepositional case. (Refer to lesson 8 for more information)

| Надя на работе | Nadya is at work |

| Вчера мы были на концерте. | Yesterday we were at the concert. |

| На столе книга и карандаш | On the table is a book and a pencil. |

| Мой отец работает на заводе и моя мама работает в библиотеке. | My father works at a plant and my mother works at a library. |

| Мы плавали в реке, а бабушка сидела у реки на траве. | We swam in the river, and grandmother was sitting on the grass at the river. |

| Она проводит за городом целый день и возвращается в город на закате. | She spends the whole day in the country and returns to town at sunset. |

| Когда мы были на юге, мы ходили к морю каждый день. | When we were in the south, we went to the sea every day. |

| На этой неделе мы встречаем наших друзей в аэропорту. | At this week we meet our friends at the airport. |

When ‘На’ is followed by the accusative case it means ‘to’ or ‘onto’.

| Надя идёт на работу. | Nadya is going to work. |

| Окна выходят на юг. | The windows look to the south. |

| Летом они всегда ездят на юг. | In summer they always go to the south. |

| В прошлом месяце моя тетя не ходила на работу. | Last month my aunt didn’t go to work. |

| Она встает в семь часов утра и идет на вокзал. | She gets up at seven o’clock and goes to the railway station. |

‘На’ is used in expressions of time that relate to weeks.

| На этой неделе… | This week… |

| На следующей неделе… | Next week… |

| На прошлой неделе я был на работе. | Last week I was at work |

5: Я — I

‘Я’ is the personal pronoun for the first person.

| Я говорю по-русски | I speak Russian |

| Я понимаю | I understand |

| Читая письмо, я не мог поверить собственным глазам. | Reading the letter, I couldn’t believe my eyes. |

| Я хотел бы кофе, пожалуйста. | I’d like a coffee, please. |

| Летом моя мама ходит на работу, а я в школу не хожу. | In summer my mother goes to work but I do not go to school. |

| На прошлой неделе я ходил в Русский музей. | Last week I went to the Russian Museum. |

| Я не слышал эту песню с прошлой зимы. | I haven’t heard this song since last winter. |

| Я весь день провел за городом и вернулся в город на закате. | I spent the whole day in the country and returned to town at sunset. |

| Я сижу на скамейке в парке и кормлю птиц. | I am sitting on a bench in the park and feeding the birds. |

6: Он — He, it.

‘Он’ is the personal pronoun for the third person (masculine).

| Он говорит по-русски | He speaks Russian |

| Он студент | He is a student |

| Куда он идёт? | Where is he going? |

| Он едет домой | He is going home |

| Слушая музыку, он забыл о времени. | Listening to the music, he forgot the time. |

| Он навестил свою сестру по случаю её дня рождения. | He visited his sister on the occasion of her birthday. |

| Он уже час работал, когда стемнело. | He had worked for an hour when it got too dark. |

| Он всегда был жестоким человеком. | He has always been a violent man. |

| Он выглядел старше, чем он был. | He looked older than he was. |

| Где мой телефон? Он был здесь минуту назад. | Where’s my Phone? It was on my desk a minute ago. |

| Родители подарили мне на День Рождения велосипед. Он очень современный и красивый. | Parents gave me a bike for my birthday. It is very modern and beautiful. |

7: Что — What, that

The word «Что» is a question pronoun that means «what»». It can be phrased simply as a question «What?». The pronoun takes the following forms.

| English | What |

| Nominative Case | Что |

| Accusative Case | Что |

| Genitive Case | Чего |

| Dative Case | Чему |

| Instrumental Case | Чем |

| Prepositional Case | Чём |

For example

| Что вы хотите? | What do you want? |

| Что случилось, после того как я ушел? | What happened after I left? |

| Что ты здесь делаешь? | What are you doing that for? |

| О чём ты говоришь? | What are you talking about? |

Like in English «Что» can also be a relative pronoun (similar to a conjunction) . It can mean ‘what’. It is preceded by a comma.

| Люди иногда спрашивают меня, что я собираюсь делать, когда я выйду на пенсию. | People sometimes ask me what I’m going to do when I retire. |

| Она была не совсем уверена, что она собиралась сказать. | She wasn’t quite sure what she was going to say. |

| Я даже не думал о том, что я собираюсь надеть на ужин. | I haven’t even thought about what I’m going to wear to the dinner. |

| Дети жалуются, что там нечего делать. | The kids complain that there’s nothing to do there. |

«Что» is also used for the conjunction «that». In Russian «Что» can not be omitted.

| Я знаю, что ты любишь музыку. | I know that you love music. |

| Я думаю, что он очень красивый | I think that it is very beautiful. |

| Я знаю, что есть проблемы, но у меня нет времени беспокоиться об этом сейчас. | I know there’s a problem, but I haven’t got time to worry about that now. |

| Я думаю, что я очень честный. | I think that I am very honest. |

«Потому что» translates to the conjunction «because». It is usually preceded by a comma.

However sometimes the comma is moved to the middle ‘потому, что’. This is done to emphasise the reason, however the difference it subtle. ‘Потому, что’ might be translated to ‘because of the fact’.

| Моя девушка не может пойти на прогулку, потому что она занята. | My girlfriend is not able to go for a walk with me today because she is very busy. |

8: С (со) — With, from

«С» has different meanings depending on the following case. It is usually pronounced as though it is part of the following word. When «с» it is followed by two or more consonants, «со» is normally used.

«С» means «with» or «accompanied by» when it is followed by the instrumental case (see Lesson 14).

| Я ем борщ со сметаной | I eat borsh with sour cream. |

| сказал он с надеждой | he said with hope |

| Иван с Анной идут в кафе. | Ivan and Anna are going to the cafe. |

| Он живет со своей бабушкой. | He lives with his grandmother. |

| Я собираюсь во Францию с парочкой друзей. | I’m going to France with a couple of friends. |

| Она жила с родителями в течение нескольких месяцев. | She was staying with her parents for a few months. |

| Она обедала со своим боссом | She was having lunch with the boss. |

«С» means «from» when it is followed by the genitive case. «С» (from) is the opposite of «на» (to). You should use the preposition «с» to translate ‘from a place’ when you would use «на» to mean ‘to a place’. (Refer: lesson 8). (Refer: ‘от’ and ‘из’ for other words that mean ‘from’).

| Ветер дует с севера. | The wind is coming from the north. |

| Она прислала мне открытку с Майорки. | She sent me a postcard from Majorca. |

| Вам придется брать деньги с кого-то еще. | You’ll have to borrow the money from someone else. |

| Он взял книгу со стола. | He took a book from the table. |

It is used in the following expressions also.

| С Рождеством | Merry Christmas |

| С днём рождения | Happy birthday |

| С новым годом | Happy new year |

9: Это — This is, that is

Это corresponds to «this is», «that is», «it is». This pronoun does not change form.

Note: The neuter form of the word «Этот» (word 20) is also spelt «это».

| Это наш дом | This is our house |

| Это верно | That is true |

| Что это? | What is it? |

| Это чай | It is tea. |

| Это мой дети | These are my children |

| Это мой муж | This is my husband |

| Это мое полотенце, а это твое. | This is my towel and that’s yours. |

| Это наш новый секретарь Вероника Тейлор. | This is our new secretary, Veronica Taylor. |

| Это полезная информация. | This is a useful information. |

| Это – безотлагательное дело. | This is an urgent matter. |

| Это уже четвертый шторм в течение одиннадцати дней. | This is already the fourth gale in eleven days. |

| Это покрывало на односпальную кровать. | This is a bed-spread for a single bed. |

10: Быть (есть) — To be, there is, there are

Быть is the verb for «to be» («is», «will», «was»). In Russian this verb is rarely used in the present tense. There are only certain cases where it is used in the present tense, these include the «to have» construction, and in the sense of «there is».

(View Conjugated Verb)

| У вас есть кофе? | Do you have coffee? |

| Есть водка? | Is there vodka? |

| Я был в кино вчера. | I was in the cinema yesterday. |

| Он будет учить русский язык. | He will learn russain. |

| Он хочет быть актером, когда закончит школу. | He wants to be an actor when he finishes school. |

| Это было ранним морозным утром. | It was a cold frosty morning. |

| В другой комнате есть женщина, которая хочет с тобой поговорить. | There’s a woman in the other room who wants to talk to you. |

| Есть небольшая проблема, которую необходимо обсудить. | There is a small problem that we need to discuss. |

| В моем супе есть волос. | There’s a hair in my soup. |

| В коробке было пять красных шаров. | There were five red balls in the box. |

11: А — And, but

«А» is a Russian conjunction that can mean ‘and’ or ‘but’. It is used when two statements contrast each other, but do not contradict each other. Quite often it is possible to translate it to either the word ‘but’ or ‘and’ in English. It’s use is normally preceded by a comma.

| Я говорю по-русски, а он говорит по-английски. | I speak Russian, but he speaks English. |

| Иван любит чай, а Надя любит вино. | Ivan loves tea, and Nadya loves wine. |

| Ты готовишь ленч, а я присматриваю за детьми. | You cook the lunch, and I’ll look after the children. |

| Я инженер, а моя мама бухгалтер. | I am engineer, and my mother is accountant. |

| Том пошел домой, а Андрей отправился на вечеринку. | Tom went home, and Andrew went to a party. |

| Моя жена любит овощи, а я фрукты. | My wife loves vegetables and I like fruits. |

| Она не художник, а писатель. | She’s not a painter but a writer. |

| Мэри была не на вечеринке, а в библиотеке. | Mary was not at the party but in the library. |

| Мой папа работает на заводе, а моя мама работает в библиотеке | My father works at a factory and my mother works at a library. |

12: Весь (Вся, Всё, Все) — All

«Весь» is the Russian word for «all», or «the whole». It takes a number of different forms depending on it’s place in the sentence.

| Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative Case | Весь | Вся | Всё | Все |

| Accusative Case (animate) |

Весь Всего |

Всю | Всё | Все Всех |

| Genitive Case | Всего | Всей | Всего | Всех |

| Dative Case | Всему | Всей | Всему | Всем |

| Instrumental Case | Всем | Всей | Всем | Всеми |

| Prepositional Case | Всём | Всей | Всём | Всех |

| Весь день | All day. |

| Всё было очень чисто | Everything was very clean |

| Вся квартира состояла из этих двух комнат | The whole apartment consisted of two rooms. |

| Мы все из Липецка | We are all from Lipetsk |

| Все животные должны есть, чтобы жить. | All animals have to eat in order to live. |

| Все мои друзья согласны. | All my friends agree. |

| Все что мне нужно, это крыша над головой и нормальная еда. | All I need is a roof over my head and a decent meal. |

| Торта не осталось. Они все съели. | There’s no cake left. They’ve eaten it all. |

| Вы потратили все свои деньги? | Have you spent all your money? |

| Вся семья собралась за столом. | All the family gathered around the table. |

13: Они — They

‘Они’ is the personal pronoun for the third person plural.

| Они работают | They work |

| Они встречаются в кафе | They meet in the cafe |

| Они желают новой семье счастливой жизни вместе. | They wish the new family happy life together. |

| Они брали уроки французского языка в прошлом году? | Did they take French lessons last year? |

| Они собираются жить в огромном доме. | They are going to live in an enormous house. |

| Они поженились на прошлой неделе. | They married last week. |

| На прошлой неделе они копали картофель. | They dug their potatoes last week. |

| Они выбрали самый большой ковер. | They chose the largest carpet. |

14: Она — She

‘Она’ is the personal pronoun for the third person (feminine).

| Она говорит по-русски | She speaks Russian |

| Она студентка | She is a student |

| Она улыбалась | She was smiling |

| Она набрала их номер два раза. | She has dialed their number twice. |

| Она получила письмо как раз вовремя. | She got the letter just in time. |

| Когда она уезжала, дождь шел уже несколько дней. | When she left it had rained for days. |

| Она сообщила о краже своего велосипеда. | She has reported the theft of her bicycle. |

| Она всегда убирает свою комнату. | She is always cleaning her room. |

| Она уже достигла цели своего путешествия? | Has she reached her destination yet? |

15: Как — How, as, like

‘Как’ is the Russian question word meaning ‘how?’…

| Как дела? | How are you? |

| Как вас зовут? | What is your name? |

| Как сказать «please» по-русски? | How do you say «please» in Russian. |

| Как нам отсюда добраться до города? | How do we get to the town from here? |

| Как вы узнали о концерте? | How did you hear about the concert? |

Like English, it can also be used like a conjugation meaning ‘how’.

| Дима не знает, как ездить на велосипеде. | Dima doesn’t know how to ride a bicycle. |

In Russian ‘Как’ is also used to make comparisons (similies). In this case it translates to ‘as’ or ‘like’…

| Белый, как снег | As white as snow |

| Он говорит по русски как настоящий русский | He speaks Russian like a native Russian |

| Я не могу бежать так быстро, как вы. | I can’t run as fast as you. |

| Это не так хорошо, как это было раньше. | It’s not as good as it used to be. |

| Я вложил деньги, как Вы предложили. | I invested the money as you suggested. |

| Это было небольшое животное, как крыса. | It was a small animal like a rat. |

| Никто не мог играть в футбол так, как он | No one could play football like him. |

| Я пошел и купил себе новую ручку — такую же как и у тебя. | I went and bought myself a new pen just like yours. |

«так как» is a conjuction meaning ‘since’. It is commonly used at the start of a sentence

| Так как Анна хотела поехать в кино, они и поехали. | Since Anna wanted to go to the cinema, they went. |

16: Мы — We

‘Мы’ is the personal pronoun for the first person plural.

| Мы понимаем | We understand |

| Мы не говорим по-русски | We don’t speak Russian |

| Мы все из Липецка | We are all from Lipetsk |

| Мы с мужем идём в кафе | My husband and I are going to the cafe. |

| Мы видели человека, у которого не было волос на голове. | We saw a man with no hair on his heard. |

| Я сказал ему, что мы всегда использовали те инструменты. | I told him that we had always used those tools. |

| Мы просили его сделать это, но он не хотел уступать. | We asked him to do it, but he didn’t want to yield. |

| Мы видели вдали деревню. | We saw the village in the distance. |

| Мы живем около красивого озера. | We live next to a beautiful lake. |

17: К (Ко) — Towards, to

‘К’ translates to ‘towards’. It is followed by the dative case. ‘Ко’ is used when two or more consonants follow.

| Липецк находится в четырехстах километрах к югу от Москвы. | Lipetsk is situated 400 kilometers to the south of Moscow. |

| Она встала и пошла к нему. | She stood up and walked towards him. |

| Существует тенденция к здоровому питанию среди всех слоев населения. | There is a trend towards healthier eating among all sectors of the population. |

| Он наклонился к жене и прошептал. | He leaned towards his wife and whispered. |

| Виктор стоял спиной ко мне. | Victor was standing with his back towards me. |

| Я часто голоден к середине обеда. | I often get hungry towards the middle of the morning. |

| К зиме темнеет раньше. | It’s getting dark earlier towards winter. |

| Госпожа Браун спешит по пути к нам. | Mrs Barnes was hurrying along the path towards us. |

‘К’ is also used when the meaning is ‘to the house of’.

| Мы едем к друзьям | We are going to our friends. |

18: У — By, near, at

The Russian preposition «У» can mean «to have». It will commonly be at the start of the sentence when it has this meaning. This sentence construction is somewhat unusual but you should remember it from lesson 9. The person who has the object follows «У» and is in the genitive case. The thing that is possessed becomes the subject of the sentence.

| У меня есть сестра | I have a sister |

| У вас есть водка? | Do you have vodka? |

| У меня нет братьев и сестер. | I don’t have brothers or sisters. |

| У них есть дача под Москвой | They have a dacha (summer house) near Moscow. |

When the preposition «У» is not used in the above construction it means «by» or «near». Again, it is used with the genitive case.

| Большинство крупных городов в мире расположены у воды. | Most large cities in the world are situated near water. |

| Собака пришла и легла у ноги. | The dog came and lay down at my feet. |

| Она стояла у книжного шкафа. | She was standing at the bookcase. |

| Где твой брат? Он в комнате, стоит у окна. | Where is your brother? He is in the room, standing at the window. |

| Она сидела там у окна. | She was sitting over there by the window. |

| Мы встречаемся у угла этого дома. | We meet at the corner of this house. |

| Дедушка вошел в гостиную и сел в кресло у камина. | My grandfather went into the living room and sat in a chair by the fireplace. |

19: Вы — You

«Вы» is the Russian pronoun for the second person plural. It is used when addressing a group of people. There is no English equivalent so English speakers may be tempted to use «yous», or «you all» in colloquial speech.

«Вы» is also used for the first person singular when you wish to address someone formally. «Ты» is usually reserved for friends and children. It is common to write Вы with a capital letter when writing to someone as it is more formal.

| Вы говорите по-русски? | Do you speak Russian? |

| Вы увидите множество российских рек. | You will see a lot of Russian rivers |

| Как Вы видите… | As you can see… |

| Я хочу пойти в свою комнату, если вы не возражаете. | I want to go to my room, if you don’t mind. |

| Вы приезжаете сегодня вечером, не так ли? | You’re coming tonight, aren’t you? |

| Как вы себя чувствуете? | How do you feel yourself? |

| Если вы занимаетесь спортом каждый день, вы будете чувствовать себя намного лучше. | If you exercise every day, you’ll feel a lot better. |

| Вы не могли бы мне помочь? | Сould you help me? |

| Вчера, когда вы пошли на прогулку, я убирал квартиру. | Yesterday, when you went for a walk, I cleaned the apartment. |

20: Этот (Эта, Это, Эти) — This

«Этот» is a demonstrative pronoun meaning «this». It declines based on case and gender. In some forms it has the same spelling as word 9 «Это» which means «this is».

| Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | This | |||

| Nominative Case | Этот | Эта | Это | Эти |

| Accusative Case (animate) |

Этот Этого |

Эту | Это | Эти Этих |

| Genitive Case | Этого | Этой | Этого | Этих |

| Dative Case | Этому | Этой | Этому | Этим |

| Instrumental Case | Этим | Этой | Этим | Этими |

| Prepositional Case | Этом | Этой | Этом | Этих |

| Этот дом новый, а тот дом старый. | This house is new, but that house is old. |

| Эта книга моя, а та книга ваша | This book is mine, and that book is yours. |

| Эта квартира слишком дорогая. | This apartment is too expensive. |

| Эта дорога ведет к станции. | This road leads to station. |

| Этот хлеб вкусный. | This bread is delicious. |

| Это велосипед почтальона? | Is this the postman’s bicycle? |

| Это ваш телевизор? | Is this your television set? |

| Это высокий книжный шкаф. | This is a tall bookcase. |

| Мой муж любит этот галстук. | My husband likes this tie. |

| Ты знал что-нибудь об этом? | Do you know anything about this? |

21: За — Behind, For

The Russian preposition «За» followed by the instrumental case can mean «behind» or «beyond».

| За домом | Behind the house. |

| Надя стоит за мной | Nadya is standing behind me. |

| Я повесил свое пальто за дверью. | I hung my coat behind the door. |

| Гарри вышел и закрыл за собой дверь. | Harry went out and shut the door behind him. |

| Менеджер сидел за огромным столом. | The manager was sitting behind an enormous desk. |

«За» is used with the accusative case when following verbs of motion because it has a sense of direction. In this case it still means «behind»

| Я иду за дом | I am going behind the house. |

«За» can also mean «for». It is used with the accusative to express thanks or the reason for a payment. In this meaning it has a sense of «in exchange for».

«За +(accusative)» can also mean «for» in the sense of «in support of» (opposite of «against»).

| Спасибо за помощь. | Thanks for helping. |

| Владимир платит за билеты. | Vladimir is paying for the tickets. |

| За это было уплачено | It has been paid for. |

| Там была засуха за последние два лета. | There have been drought conditions for the last two summers. |

| Я продал свой автомобиль за £ 900. | I sold my car for £900. |

| Они купили весь бизнес примерно за 15 миллионов фунтов. | They bought the entire business for around £15m. |

| Я присматриваю за детьми. | I am looking for the children. |

«За» followed by the instrumental can mean «for» in the sense of «to get».

| Он пошел за молоком. | He went for (to get) milk. |

«За» can be used to express a duration of time (with accusative)

| Саша съел обед за пять минут. | Sasha ate his lunch in 5 minutes |

22: Тот (та, то, те) — That

«Тот» is the Russian demonstrative pronoun meaning «that». It is very similar to «Этот» (this).

| Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | That | |||

| Nominative Case | Тот | Та | То | Те |

| Accusative Case (animate) |

Тот Того |

Ту | То | Те Тех |

| Genitive Case | Того | Той | Того | Тех |

| Dative Case | Тому | Той | Тому | Тем |

| Instrumental Case | Тем | Той | Тем | Теми |

| Prepositional Case | Том | Той | Том | Тех |

| Этот дом новый, а тот дом старый. | This house is new, but that house is old. |

| Эта книга моя, а та книга ваша | This book is mine, and that book is yours. |

| В те дни не существовало телефона. | There were no telephones in those days. |

| Я хочу купить тот свитер. | I want to buy that sweater. |

| Она живет в том доме возле автобусной станции. | She lives in that house by the bus station. |

| Мне никогда не нравился тот ее двоюродный брат. | I’ve never liked that cousin of hers. |

| Двигатель снова начал издавать тот шум. | The engine’s started making that noise again. |

| Та девушка очень симпатичная, я хочу с ней встретиться. | That girl is very pretty, I want to meet her. |

23: Но — But

«Но» is the Russian conjunction meaning «but». It is used when two parts of a sentence contradict one another. Remember that «А» (word 11) is used when the clauses contrast one another but don’t contradict.

| Анна очень умная девушка, но она довольно ленивая. | Anna’s a highly intelligent girl, but she’s rather lazy. |

| Моя квартира большая, но квартира Петрова больше. | My flat is large, but Petrov’s is lager. |

| Я знаю, что есть проблемы, но у меня нет времени беспокоиться об этом сейчас. | I know there’s a problem, but I haven’t got time to worry about that now. |

| Эта машина очень дорогая, но надежная. | Their car is very expensive but reliable. |

| У него есть кот, но нет собаки. | He has a cat, but he has no dog. |

| В субботу в клубе была дискотека, но он не пошел. | There was a disco at the club last Saturday but he didn’t go. |

24: Ты — You (familiar)

«Ты» is the Russian pronoun for the second person singular. It is informal and commonly used with friends and children. Use «Вы» instead when formality is required.

| Ты понимаешь? | Do you understand? |

| Ты любишь апельсины? | Do you like oranges? |

| Ты всё ещё холост? | Are you still single? |

| Я пришел спросить, как ты себя чувствуешь? | I came to ask how you are. |

| Ты разочаровал меня. | You have disappointed me. |

| Ты видишь маленькую девочку с большим мячом в руках? | Do you see a little girl with a big ball in her hands? |

| Если ты хочешь, чтобы твой хлеб оставался свежим, храни его в холодильнике. | If you want your bread to be fresh, keep it only in the refrigerator. |

25: По — Along, around, according to, by

«По» is one of the most difficult Russian prepositions to translate. It has a number of different uses and meanings, and needs to be translated based on context.

It is most commonly used with the dative case. «По» (+dative) can mean «around»

| Романтик прогуливался по пляжу. | Romantic walk along the beach. |

| Он шел по улице и заметил своего друга. | He was walking along the street and saw his friend. |

| По утрам Джессика совершает пробежку по парку. | In the morning, Jessica makes a jog along the park. |

«По» (+dative) can mean «along»

| Дети бегали по комнате. | The children were dancing around the room. |

| У них есть около 15 офисов, разбросанных по всей стране. | They have about 15 offices scattered around the country. |

| Почему эти вещи разбросаны по полу. | Why are all those clothes lying around on the floor? |

«По» (+dative) can mean «according to»

| По нашим данным, Вы должны нам $130. | According to our records you owe us $130. |

| По словам Сары, они получают на очень много на данный момент. | According to Sarah they’re not getting a lot (of money) at the moment. |

| Мы должны стараться играть в игру по правилам. | We should try to play the game according to the rules. |

«По» (+dative) can mean «by»

| Я взял по ошибке вашу шляпу. | I took your hat by mistake. |

| Нам платят за работу по часам. | We get paid by the hour. |

| Туда можно ехать парохбдом или по железной дороге. | You can get there by boat or by train. |

26: Из — Out of, from

«Из» can mean ‘out of’ or ‘from’.

| Яблоко выкатилось из мешка. | An apple rolled out of the bag. |

| Кофе-машина вышла из строя. | The coffee machine is out of order. |

| Платье было сделано из бархата. | The dress was made out of velvet. |

| Девять из десяти человек сказали, что им понравился продукт. | Nine out of ten people said they liked the product. |

| Никто не получил 20 из 20 в тесте. | No one got 20 out of 20 in the test. |

«Из» is normally used in expressions of place. ‘Из’ (from) is the opposite of ‘в’ (to). ‘Из’ is normally used in expressions of place. For example… «from America», «from school».

(Refer to ‘с’ and ‘от’ to translate ‘from’ in relation to time, distance and person.

| Во сколько прибывает рейс из Амстердама? | What time does the flight from Amsterdam arrive? |

| Он вынул носовой платок из кармана. | He took a handkerchief from his pocket. |

| Она вынула расческу из сумочки и начала причесывать волосы. | She took her hairbrush from her handbag and began to brush her hair. |

Note: «из-за» means either ‘from behind’, or ‘because of’.

Note: «из-под» means either ‘from under’, or ‘for’.

27: О (об, обо) — About

«О» means «about» or «concerning» when it is used with the prepositional case. «об, обо» and are used for readability when a word starting with a vowel or multiple consonants follows.

| Мы поговорили обо всём, что нас волновало. | We talked about everything that we care. |

| Подумайте о том, что я вам говорил. | Think about what I’ve told you. |

| Я беспокоюсь о папе. | I’m worried about Dad. |

| Он еще не видел фильм, о котором я говорил. | He had not yet seen the film I was talking about. |

| Еще кто-нибудь знает о том, что я прибыл? | Does anyone else know about my arrival? |

| Ты знал что-нибудь об этом? | Do you know anything about this? |

| Ее мама сказала купить ей хлеб, а она забыла об этом. | Her mother had told her to buy some bread but she had forgotten about it. |

28: Свой — One’s own

«Свой» is the Russian reflexive possessive pronoun. It is used when the owner of something is also the subject. (Its use is required in the 3rd person, and optional in the 1st and 2nd. Although it is almost always used if the subject is ты).

More information about reflexives can be found in the Reflexive Verbs grammar lesson.

| Masc. | Fem. | Neut. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | My own, his own, her own | |||

| Nominative Case | Свой | Своя | Своё | Свои |

| Accusative Case (animate) |

Свой Своего |

Свою | Своё | Свои Своих |

| Genitive Case | Своего | Своей | Своего | Своих |

| Dative Case | Своему | Своей | Своему | Своим |

| Instrumental Case | Своим | Своей | Своим | Своими |

| Prepositional Case | Своём | Своей | Своём | Своих |

| Я разбил свою собственную машину вчера. | I smashed му own car yesterday. |

| Каждый человек имеет свое представление, что такое демократия. | Everyone has their own idea of what democracy means. |

| Каждый район в Нью-Йорке, имеет свои особенности. | Each neighbourhood in New York has its own characteristics. |

| Я бы никогда не поверил, если бы не увидел своими глазами. | I’d never have believed it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes. |

| У тебя есть свой дом? | Do you have your own house? |

| Вчера я делал уборку в доме и стирал свою одежду. | Yesterday I cleaned the house and washed my own clothes. |

| Он провел последние годы своей жизни в основном в Стратфорде . | He spent the last years of his life mostly in Stratford. |

29: Так — So

«Так» translates to ‘so’ and it’s use in Russian is quite similar to English.

| Я так устал, что я могу уснуть прям в этом кресле! | I’m so tired that I could sleep in this chair! |

| Я так рада, что вы смогли приехать. | I’m so glad you could come. |

| Она так любила смотреть, как играют дети. | She so loved watching the children play. |

| Он родился во Франции, так что у него также есть французский паспорт. | He was born in France, so he also has a French passport. |

| Вчера я ходил в гости к друзьям, это было так весело. | Yesterday I went to visit friends, it was so funny. |

| Ты не должен так делать. | You should not do so. |

«так как» is a conjuction meaning ‘since’. It is commonly used at the start of a sentence.

| Так как Анна хотела поехать в кино, то они и поехали. | Since Anna wanted to go to the cinema, they went. |

30: Один (Одна, Одно) — One

«Один» is the number 1.

| У вас три сумки, а у меня только одна. | You’ve got three bags and I’ve only got one. |

| У меня есть только один свободный час. | I’ve only got one hour free. |

| У них одна дочь и пятеро сыновей. | They have one daughter and five sons. |

| Сколько стоят эти брюки? Одну сотню пятьдесят фунтов. | How much are these pants? One hundred and fifty pounds. |

| Одна картинка маленькая, другая – очень большая. | One picture is small, the other picture is very large. |

| Санкт-Петербург — один из самых больших городов в России. | St. Petersburg is one of the largest cities in Russia. |

31: Вот — Here, there.

«Вот» can mean ‘here’ or ‘there’. It is used when are pointing or gesturing towards something. If you are not pointing then ‘here’ will usually translate as ‘здесь’ (word 74) instead.

| Вот Фиона — позвольте мне познакомить вас с ней. | Here’s Fiona — let me introduce you to her. |

| Вот книга, которую я одалживал у тебя. | Here’s the book I had lend you. |

| О, вот мои очки. Я думал, что потерял их. | Oh, here are my glasses. I thought I’d lost them. |

| Ах, вот вы где! Я искал вас повсюду. | Ah, here you are! I’ve been looking everywhere for you. |

32: Который — Which, who

«Который» means ‘which’ and declines like an adjective.

In Russian the use of Который is more strict. In English we may ask «What book do you like?», but it is more correct to ask «Which book do you like?». This distinction is important in Russian.

| Который час? | What is the time? (lit: Which hour?) |

| Я думал о тех вопросах, которые вы задали меня на прошлой неделе. | I’ve been thinking about those questions which you asked me last week. |

| Это сказка, которой будет наслаждаться каждый ребенок. | It’s a story which every child will enjoy. |