INTRODUCTION

When a language is taught to students of non-linguistic specialties

-so-called Language for Special Purpose (LSP) — this fact is usually taken into

account by the authors of language manuals and results in special manuals

either intended for a particular profession (for example, English

for Law Students) or covering a range of similar occupations (e. g.,

Technical English, Financial English, etc.).

As a rule, LSP Manuals focus students’

attention on peculiar professional vocabulary and phrasing, comprise

training text materials pertaining to particular profession and

explain grammar rules and stylistic patterns conspicuous for certain professional

speech variety. Also, LSP Manuals include numerous translation

exercises involving texts of specific professional orientation.

Although

translation is part and parcel of any LSP Manual, however, with

several rare exceptions (e. g., Military Translation

Manual by L. Nelyubin et al.) there are no translation manuals

specifically intended for students of non-linguistic specialties.

First and most of all, translation is an

effective tool that assists in matching language communication

patterns of the speakers of different languages in a specific

professional field, especially such communication-dependent one

as international relations.

This aspect of translation teaching becomes

even more important under the language development situation typical of New

Independent States such as Kazakhstan.

Thought

this work is titled «Lexical problems of translation»,

this is not the only point examined. The qualification paper consists

of three parts and each part in its turn divided

into points.

The author’s trying to explain the importance of language

in translation observing its different fields and aspects. We

also come across with phraseological translation and its problems.

So, this work should be of particular interest to students of foreign languages

universities and those who’re interested in studying languages, as

well.

PART I. IMPORTANCE OF LANGUAGE IN TRANSLATION

1.1 Language and extra linguistic world.

The language sign is a sequence of sounds (in

spoken language) or symbols (in written language) which is associated with

a single concept in the minds of speakers of that or another language.

It should be noted that sequences smaller

than a word (i.e morphemes) and those bigger than a word (i.e. word

combinations) are also language signs rather than .only words. Word

combinations are regarded as individual language signs if they are related to a

single mental concept which is different from the concepts of its individual

components (e. g. best man).

The

signs of language are associated with particular mental concepts only

in the minds of the speakers of this language. Thus, vrouw, Frau, femeie, and

kobieta are the language signs related to the concept of a woman m

Dutch, German, Romanian and Polish, respectively. It is important to note that

one can relate these signs to the concept of a woman if

and

only if he or she is a speaker of the relevant language or knows these words

otherwise, say, from a dictionary.

One may say that language signs are a kind of construction

elements (bricks) of which a language is built. To prove

the necessity of knowing the language sign system in order to

understand a language it is sufficient to run the following test: read with a

dictionary a text m a completely unknown language with complex declination

system and rich inflexions (say, Hungarian or Turkish). Most probably your

venture will end in failure because not knowing the word-changing

morphemes (language signs) of this language you won’t find many of

the words in a dictionary.

The mental concept is an array of mental

images and associations related to a particular part of the extra

linguistic world (both really existing and imaginary), on the one

hand, and connected with a particular language sign, on the other.

The relationship between a language sign and

a concept is ambiguous: it is often different even in the minds of

different people, speaking the same language, though it has much in

common and, hence, is recognizable by all the members of the language

speakers community. As an example of such ambiguity consider

possible variations of the concepts (mental images and associations)

corresponding to the English word engineer in the minds

of English-speaking people when this word is used, say, in a

simple introductory phrase Meet Mr., X. He is an engineer.

The

relationship between similar concepts and their relevant language

signs may be different also in different languages. For example,

among the words of different languages corresponding to the concept

of a women mentioned above: vrouw-, Frau, femeie, and

kobieta, the first two will include in the

concept of a woman that of a wife whereas the last two will not..

The differences in the relationship between

language signs and concepts (i.e.

similar concepts appearing different to the speakers of different languages and

even to different speakers of the same language) may explain many of the

translation difficulties.

For example, the German word haben possesses

the lexical meaning of to have with similar

connotations and associations and in its grammatical meaning it belongs as an element

to the German grammatical system of the Perfect Tense. One

may note similar division of the meanings in the English verb

to have or in the French verb avoir.

Thus, a lexical meaning is the general

mental concept corresponding to a word or a combination of

words To get a better idea of lexical meanings lets

take a look at some definitions in a dictionary . For practical

purpthey may be regarded as descriptions of the lexical

meanings of the words shown below:

mercy

— 1. (capacity for) holding oneself back from punishing,

or from causing suffering to, somebody whom one has the

right or power to punish;

2.

piece of good fortune, something to be thankful for, relief;

3. exclamation of surprise or (often pretended) terror.

noodle — 1. type of paste of flour

and water or flour and eggs prepared in long, narrow strips and used in soups,

with a

sauce, etc.; 2. fool.

blinkers

(US — blinders) — leather squares to prevent a horse from seeing

sideways.

A connotation is an additional, contrastive

value of the basic usually designative function of the

lexical meaning. As an example, let us compare the

words to die and to peg out. It is easy to note that the former

has no connotation, whereas the latter has a definite connotation of vulgarity.

An association is a more or less regular

connection established between the given and other

mental concepts in the minds of the language speakers. As an

evident example, one may choose red which is usually associated

with revolution-, communism and the like. A rather regular association

is established between green and fresh {young) and (mostly in the

last decade) between green and environment protection.

Naturally,

the number of regular, well-established associations accepted by the

entire language speakers’ community is rather limited — the

majority of them are rather individual, but what is more important for

translation is that the relatively regular set of associations is sometimes

different in different languages. The latter fact might affect the choice of

translation equivalents.

The concepts being strongly subjective and

largely different in different languages for similar denotata

give rise to one of the most difficult problems of translation, the problem of ambiguity

of translation equivalents.

These relations are

called polysemy (homonymy) and synonymy,

accordingly. For example, one and the same language sign bay

corresponds to the concepts of a

tree

or shrub, a part of the sea-, a compartment in a building, room

etc., deep barking of dogs, and reddish-brown color of a horse

and one and the same concept of high speed corresponds to several

language signs: rapid, quick, fast.

The peculiarities of conceptual fragmentation

of the world by the language speakers are manifested by the

range of application of the lexical meanings (reflected in limitations in the

combination of words and stylistic peculiarities). This is yet another

problem having direct relation to translation — a translator is to observe the

compatibility rules of the language signs (e. g. make mistakes,

but do business).

The relationship of language signs with the

well-organized material world and mostly logically arranged

mental images suggests that a language is an orderly system

rather than a disarray of random objects.

1.2 Language as a means of communication

Thus, a language may be regarded as a

specific code intended for information exchange between its users

(language speakers). Indeed, any language resembles a code being

a system of interrelated material signs (sounds or

letters), various combinations of which stand for various

messages. Language grammars and dictionaries may be

considered as a kind of Code Books, indicating both the meaningful combinations

of signs for a particular language and their meanings.

For

example, if one looks up the words (sign

combinations)

elect and college in a dictionary, he will find that they are

meaningful for English (as opposed, say, to combinations ele or oil),

moreover, in an English grammar he will find that, at least,

one combination of these words: elect college is

also meaningful and forms a message.

The process of language communication involves

sending a message by a message sender to a message recipient —

the sender encodes his mental message into the code of a

particular language and the recipient decodes it using the same code

(language).

The communication variety with one common language

is called the monolingual communication.

If, however, the communication process

involves two languages (codes) this variety is called the bilingual communication.

Bilingual communication is a rather typical

occurrence in countries with two languages in use (e. g. in Ukraine or

Canada). In Ukraine one may rather often observe a conversation where one

speaker speaks Ukrainian and another one speaks Russian. The

peculiarity of this communication type lies in the fact that decoding

and encoding of mental messages is performed simultaneously in two

different codes. For example, in a Ukrainian-Russian pair one speaker encodes

his message in Ukrainian and decodes the message he received

in Russian.

Translation is a specific type of bilingual

communication since (as opposed to bilingual communication proper) it obligatory

involves a third actor (translator) and for the message sender

and recipient the communication is, in

fact, monolingual.

Translation

as a specific communication process is treated by the communicational

theory of translation discussed in more detail elsewhere in this

Manual.

Thus, a language is a code used by language

speakers for communication. However, a language is a specific code

unlike any other and its peculiarity as a code lies

in its ambiguity — as opposed

to a code proper a language produces originally ambiguous messages which are

specified against context-, situation

and background information.

Let us take an example. Let the original

message in English be an instruction or order Book! It is

evidently ambiguous having at least two grammatical meanings (a noun

and a verb) and many lexical ones (e. g., the

Bible, a code, a book, etc. as a noun) but one

will easily and without any doubt understand this message:

1.

as Book tickets! in a situation involving

reservation

of tickets or

2.

as Give that book! in a situation involving sudden and

urgent

necessity to be given the book in question.

So, one of the means clarifying the meaning

of ambiguous messages is the fragment of the real world that surrounds

the speaker which is usually called extra linguistic situation.

Another possibility to clarify the meaning of

the word book is provided by the context which

may be as short as one more word a {a book) or several words (e.g., the

book I gave you).

In simple words a context may be defined

as a length of speech (text) necessary to clarify the

meaning of a given word.

The ambiguity of a language makes it

necessary to use situation and context to properly generate

and understand a message (i.e. encode and decode it).Since

translation according to communicational approach is decoding and

encoding in two languages the significance of situation and context for

translation cannot be overestimated.

There is another factor also to be taken into

account in communication and, naturally, in translation. This factor

is background information, i.e. general awareness of the

subject of communication.

To

take an example the word combination electoral college

will mean nothing unless one is aware of the presidential election system in the

USA.

Apart from being a code strongly dependent on

the context, situation and background information a language

is also a code of codes. There are codes within codes in specific

areas of communication (scientific, technical, military, etc.) and

so called sub-languages (of professional, age groups, etc.). This

applies mostly to specific vocabulary used by these groups though there are

differences in grammar rules as well.

As an example of the elements of such in-house languages one

may take words and word combinations from financial sphere (chart

of accounts, value added, listing), diplomatic practice (credentials,

charge d’affaires, framework agreement) or legal language

(bail, disbar, plaintiff).

PART

2. LEXICAL TRANFORMATION

2.1 LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES.

Due to the semantic features of language the

meaning of words, their usage, ability to combine with other

words associations awakened by them, the «place» they hold in

the lexical system of a language do not concur for the most

part. All the same «ideas» expressed by words coincide in most

cases, though the means of expression differ.

As it is impossible to embrace all the cases

of semantic differences between two languages, we shall restrict this

course to the most typical features.

The

principal types of lexical correspondences between two languages are as

follows:

I.

Complete correspondences.

II.

Partial correspondences.

III.

The absence of correspondences.

I.

COMPLETE LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES Complete correspondence of

lexical units of two

languages

can rare!) be found. As a rule they belong to the

following

lexical groups,

1)

Proper names and geographical denominations;

2)

Scientific and technical terms (with the

exception of terminological polysemy);

3)

The months and days of the week, numerals.

II. PARTIAL LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES

While translating the lexical units partial correspondences mostly occur. That happens when a word m the language of the original conforms to several

equivalents in the language it is

translated into. The reasons of these facts are the following.

1. Most words in a language are polysemantic, and the

same of word-meaning in one language

does not concur the

same system in another language completely. That’s why the

selection of a word in the process of translating is determined

by the context.

The specification of synonymous order which

pertain selection of words. However, it is necessary to allow the nature

of the semantic signs which an order of synonyms is based

on. Consequently, it is advisable to account the concurring meanings

of members of synonymic orders, the difference in lexical and

stylistic meanings, and ability of individual components of

orders of synonyms combine: e. g. dismiss, discharge (bookish), sack, fire; the

edge of the table— the rim of the moon.

2. Each word effects the meaning of an object it

designates. Not infrequently languages «select» different

proper-s and signs to describe the

same denotations. The way,

each language creates its own «picture

of the world», is known

as «various principles of dividing

reality into parts». Despite

the difference of signs, both

languages reflect one and the

same phenomenon adequately and to the

same extent, lich must

be taken into account when

translating words of this kind, as

equivalence is not identical to having

the same meaning.

3.

The difference of semantic content of the

equivalent

words in two languages. These words can be divided into three sub-groups:

a) Words with a differentiated (undifferentiated)

mean-g: e. g. In English: to swim (of

a human being), to sail of ship), to

float (of an inanimate object).

b)

Words with a «broad» sense: verbs of state (to be),

perception and brainwork (to see, to understand), verbs of

action and speech (to go, to say), partially desemantisized

words (thing, case).

c)

«Adverbial verbs» with a composite structure,

which

have a semantic content, expressing action and nature at the

same time: e.g. The train whistled out of the station.

4. Most difficulties are encountered when

translating the so called pseudo-international words, 1. e. words

which are similar in form in both languages, but differ in meaning

or use. The regular correspondence of such words in spelling and sometimes

in articulation (in compliance with the regularities of

each language), coupled with the structure of word- building in

both languages may lead to a false identifier.

5. Each language has its own

typical rules of combinability. The latter is limited by the system of the language.

A language has generally established traditional combinations which do

not concur with corresponding ones in another language.

Adjectives offer considerable difficulties in the process

of translation that is explained by the specific ability of English

adjectives to combine. It does not always coinside with their

combinability in the Russian language or:

account of differences m their semantic

structure and valence. Frequently one and the same adjective in English

combines with a number of nouns, while in Russian different adjectives

are used in combinations of this kind, For this reason it is not easy

to translate English adjectives which are more capable of combining than their

Russian equivalents.

A specific feature of the combinability of

English nouns Is that some of them can function as the subject of a

sentence, indicating one who acts, though they do not belong to a

lexico-semantic category Nomina Agentis. This tends to the «predicate—adverbial

modifier» construction being replaced by that of the «subject—predicate».

Of no

less significance is the habitual use of a word, which is bound up

with the history of the language and the formation and development of its

lexical system. This gave shape to cliches peculiar to each

language, which are used for describing particular situations.

2.2.

TYPES OF LEXICAL TRANSFORMATIONS

In order to attain equivalence,

despite the difference in formal and semantic systems of two

languages, the translator is obliged to do various linguistic

transformations. Their aims are: to ensure that the text imparts all

the knowledge I inferred in the original text, without violating the

rules of the language it is translated into.

The following three elementary types are deemed most suitable for describing all

kinds of lexical

transformations:

1.lexical

substitutions;

2.

supplementations;

3.omissions

(dropping) .

1.

Lexical substitutions.

a) In

substitutions of lexical units words and stable word combinations are

replaced by others which are not their equivalents. More often three

cases are met with: a) a concrete definition—replacing a word

with a broad sense by one of a narrower meaning.

b)

generalization—replacing a word with a narrow meaning by one with a

broader sense.

c) Antonymous

translation is a complex lexico-grammatical substitution of

a positive construction for a negative one (and vice versa), which is

coupled with a replacement of a word by its antonym when

translated.

d) Compensation

is used when certain elements in the original text cannot be

expressed in terms of the language it is translated into. In cases of

this kind the same information is communicated by other means

or in another place so as to make up the semantic deficiency. ( … He

was ashamed of his parents . . ., because they said «he don’t» and

«she don’t».

2.Supplementations. A formal inexpressibility of

semantic components is the reason most met with for using

supplementations as a way of lexical transformation. A formal

inexpressibility of certain semantic components is especially

of English word combinations N+N and Adj.+N

3.Omissions (dropping). In the process of lexical

transformation of omission generally words with a surplus

meaning are omitted (e. g. components of typically English

pair-synonyms,

possessive pronouns and exact measures) in order to give a more

concrete expression.

III. ABSENCE OF LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES

Realiae are words denoting objects, phenomena

and so on, which are typical °f a people. In order to render correctly the

designation of objects referred to in the original and image associated

with them it is necessary to know the tenor of life

epoch and specific features of the country

depicted in the original work.

The following groups of words can be regarded

as having no equivalents:

1)

realiae of everyday life—words denoting objects,

phenomena

etc., which typical of a people (cab, fire:

-place);

2)

proper names and geographical denominations;

3)

addresses and greetings;

4)

the titles of journals, magazines and newspapers;

5)

weights, linear measures etc.

When dealing with realiae it is necessary to

take special account of the pragmatic aspect of the translation,

because the «knowledge gained by experience» of the participants of

the communicative act turns out to be different. As a result,

much of which is easily understood by an Englishman is in

comprehensible to an Uzbek or Russian readers or exerts the opposite

influence upon them. It is particularly important to allow for the pragmatic

factor when translating fiction, foreign political propaganda

material and

advertisements

of article’s for export.

Below are three principal ways of translating

words denoting specific-realiae:

1) transliteration (complete or partial), i.e.

the direct use of a word denoting realiae or its root

in the spelling or in combination with suffixes of the mother

tongue.

2)creation of new single or complex word for

denoting an object on the basis of elements and morphological relationship

in the mother tongue.

3)use of a word denoting something close to

(though not identical with) realiae of another language. It

represents an approximate translation specified by the context, which is

sometimes on the verge of description.

2.3

Translation definition

Translating

a phraseological unit is not an easy matter as it depends on several

factors: different combinability of words, homonymy, synonymy, polysemy

of phraseological units and presence of falsely identical units,

which makes it necessary to take into account of the context.

Besides, a large number of phraseological units have a stylistic-expressive

component in meaning, which usually has a specific national feature.

The afore-cited determines the necessity to get acquainted

with the main principles of the general theory of phraseology.

The

following types of phraseological units may be observed: phrasemes

and idioms. A unit of constant context, consisting of a dependent and a

constant indicators may be called a phraseme. An idiom is a unit of

constant context which is characterized by an integral meaning

of the whole and

by

weakened meanings of the components, and in which the dependant

and the indicating elements ore identical and equal for

the -whole lexical structure of the phrase.

Any type of phraseological unit can be

presented as a definite micro-system. In the process of

translating phraseological units functional adequate linguistic units are selected

by comparing two specific linguistic principles. These principles

reveal elements of likeness and distinction. Certain parts

of these systems may correspond in form and content (completely or partially)

or have no adequancy.

The main types of phraseological conformities

are as follows:

I.

Complete conformities.

II.

Partial conformities.

III.

Absence of conformities.

I. Complete

conformities. Complete coincidence of form and content in

phraseological units is rarely met with.

1.black

frost (Phraseme)

2.To

bring oil to fire. (Idiom)

3.To

lose one’s head. (Idiom)

II. Partial conformities. Partial conformities of phraseological units in two languages assume

lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical

differences with identity of meaning

and style, i.e. they arc figuratively close, but differ in lexical composition, morphologic number and syntactic

arrangement of the order of words. One may find:

1) Partial

lexic conformities by Iexic parameters (lexical

composition):

l.To get out of bed on the wrong foot. (Idiom) 2.To have one’s heart in one’s boots. (Idiom) 3.To lose one’s temper. (Phraseme)

4.To

dance to smb’s pipe. (Idiom)

2) Partial

conformities by the grammatical parameters:

differing as to morphological

arrangement'(number).

1 To

fish in troubled waters. (Idiom)

2 From

head to foot. (Idiom)

3 to

agree like cats and dogs (Phraseme)

4 to keep one’s head (Idiom)

b)

differing as to syntactical arrangement

1.Strike

while the iron is hot

2.Egyptian

darkness

3.armed

to teeth

4.All is not gold that glitters

III. Absence of conformities.

Many

English phraseological units have no phraseological conformities

in Russian. In the first instance this concerns phraseological

units based on realiae. When translating units of this kind it is

advisable to use the following types of translation:

A.

verbatim word for word translation

B. Translation by analogy.

C. Descriptive translation,

Verbatim translation is possible when the way

of thinking (in the phraseological unit) does

not bear a specific national feature,

l.To call things

by their true

names.(Idiom)

2.The arms race. ( Phraseme)

3.Cold war. (Idiom)

Translating

by analogy. This way of translating is resorted to when the phraseological

unit has a specific national realiae.

1.

«Dick», said the dwarf, thrushing his head in at the door-

«my pet», my pupil, the apple of my eye hey! (Idiom)

2.

to pull somebody’s leg (Idiom)

Descriptive translation. Descriptive

translating i e. translating phraseological units by a free combination of words is possible when the phraseological unit has a particular national feature and has no

analogue in the language it is to be translated

into.

1.to

enter the House (Phraseme)

2.to

cross the floor of the House (Idiom) Usually when

people

speak about translation or even write about it in

special

literature they are seldom specific about the meaning. The

presumption is quite natural- everybody understands the

meaning of the word. However to describe translation intuitive understanding

is not sufficient — what one needs is definition.

Translation

means both a process and a result and when defining translation we are

interested in both its aspects. First of all,

we are interested in the process because it is the process we are

going to define.

But at the same time

we need the result of translation since alongside with the

source the translated text is one of the two sets of observed events

we interested in disposal of we intend to describe the process. In order to

explain translation we need to compare the original source text and

resulting target text.

However the formation of the source text and

target text is governed by the rules characteristic of the source and target languages.

Moreover, when describing a language one

should never forget that language itself is a formal model of thinking, i.e. of

mental concepts we use when thinking.

In

translation we deal with two languages: two codes and verify

the information they give us about the extralinguistic object and

concepts we should consider extralinguistic situation and background

information.

Having considered all this we shall come to

understand that as an object of linguistic study translation is a

complex entity consisting of the following interrelated

components.

a. Elements and structures of the source text.

b. Elements and structures of the target language.

c. Systems of the languages involved in translation.

d. Transformation rules to transform the elements

and structures of the source texts

into those of the

target text.

e. Conceptual content and organization of the source

text, conceptual content

and organization of the

target text.

f.

Interrelation of the conceptual contents of the

source

and target texts.

In short, translation is functional

interrelation of languages and to study this process we should

study both the interacting elements and the rules of

interaction.

Among interacting elements we must distinguish

between the observable and those deducible from the observables. The observable

element in translation are part of words, words, and word

combinations of the source text.

However, translation process involves parts of words and word

combinations of the target language (not of the target text, because

when we start translating or to be more exact when we I

begin to build a model of translation, the target text is yet to be I

generated). These translation compositions deducible from I

observable elements of the source text.

Thus, the process of translation may be

represented as I consisting of three stages:

1.

analysis of the source text, situation and

background information.

2.

synthesis of the translation model, and

3.

verification of the model against the source and

target context (semantic, grammatical, stylistic),

situation, and background information resulting in the

generation of the final I target text.

Let

us illustrate this process using a simple assumption I

that you receive for translation one sentence at a time (by the way I this

assumption is a reality of consecutive translation). For example,

if you received:

«At

the first stage the chips are put on the conveyer» as

the source sentence. Unless you observe or know the situation

your model of the target text will be:

» На первом этапе стружку (щебень,

жареный картофель, нерезаный сырой картофель, чипсы) помещают на конвейер.

Having verified this model against the

context provided in the next sentence (verification against

semantic context):

»

Then they are transferred to the frying oven «

you will obtain:

“На первом этапе нарезанный сырой картофель помещают

на конвейер.”

It looks easy and self-evident, but it is

important indeed for understanding the way translation is done. In

the case we have just discussed the translation model is verified

against the relevance of the concepts corresponding to the word

«chips» in all its meaning to the concept of the word

«frying».

Then, omitting the grammatical context which

seems evident (though, of course, we have already analyzed it intuitively) we

may suggest the following intermediate model of the target text that

takes into account only semantic ambiguities:

Европейские лидеры (лидеры европейской

интеграции) считают (верят) что эта критика постепенно прекратится (сойдет на

нет). Как только важность расширения (Евросоюза) начнет утверждаться в сознании

общества (как только общество станет лучше понимать значение расширения

Европейского союза)

On the basis of this model we may already suggest a final target

text alternative:

Лидеры европейской интеграции считают. Что

как только важность расширения Европейского союза начнет утверждаться в

сознании общества, эта критика постепенно сойдет на нет.

We seldom notice this mental work of ours, but always do it

when translating. However, the way we do it is very much dependent on

general approach, i.e. on translation theories which are

our next subject.

2.4

Translation ranking.

Even in routine translation process there no

different ways of translation, that

one rank of translation consists of rather simple substitutions whereas another involves relatively

sophisticated and not just purely linguistic analysis.

Several attempts have been made to develop a

translation theory based on different translation ranks or levels as

they are sometimes called. Among those one of the most popular in the former

Soviet Union was the “theory of translation equivalence level

(TEL)” developed by V.Komissarov.

According to his theory the translation

process fluctuates passing from formal inter-language

transformations to the domain of conceptual interrelations. V. Komissarov’s

approach seems to be a realistic interpretation of the translation

process, however, this approach fails to demonstrate when and one

translation equivalence level becomes no longer appropriate and, to get a correct

translation, you have to pass to a higher TEL.

Ideas

similar to TEL are expressed by Y.Retsker who maintains that any

two languages are related by «regular» correspondences (words,

word-building patterns, syntactical structures) and «irregular» ones.

The irregular correspondences cannot be formally represented and only

the translators knowledge and intuition can help to find the

matching formal expression in the target language for a concept

expressed in the source language.

According to J. Firth in order to bridge

languages in the process of translation, one must use the whole

complex complex of linguistic and extralinguistic information rather

than limit oneself to purely linguistic objects and structures.

J.Catfort similar to V.Komissarov and J.Firth interprets

translation as a multy-level process. He distinguishes between

«total» and «restricted» translation- in «total»

translation all levels of the source text are replaced by those of the target

text, whereas in “restricted” translation the substitution occurs

at only one level.

According to J. Catford a certain set of

translation tools characteristic of a certain level constitutes

a rank of translation and a translation performed using that or another set of

tools is called rank level.

Generally speaking, all theories of human translation discussed

above try to explain the process of translation to a degree of precision

required for practical application, but no explanation is complete so

far.

The transformational approach quite convincingly suggests

that in any language there are certain regular syntactic, morphological,

and word-building structures which may be successfully matched with

their analogies in another language during translation.

Besides, you may observe evident similarity

between the transformational approach and primary translation ranks

within theories suggesting the ranking of translation

(Komissarov, Retsker, Catford and others).

As you will note later, the transformational

approach forms the basis of machine translation design — almost any machine translation system uses the principle of

matching forms of the languages involved in translation. The

difference is only in the forms that are matched and the rules of

matching.

The denotative approach treats different

languages as closed systems with specific relationships between

formal and conceptual aspects, hence in the process of translation

links between the forms of different languages are established

via conceptual.

This is also true, especially in such cases

where language expressions correspond to unique indivisible

concepts. Here one can also observe similarity with higher ranks

within the theories suggesting the ranking of translation.

The communicational approach highlights a very

important aspect of translation — the matching of the sauruses. Translation may

achieve its ultimate target of rendering a piece of information only

if the translator knows the users’ language and the subject matter

of the translation well enough (i.e. if the translator’s language

and subject thesauruses are sufficiently complete). This may

seem self-evident, but should always be kept in mind, because all

translation mistakes result from the insufficiencies of the thesauruses.

Moreover, wholly complete thesauruses are the

ideal case. No translator knows the source and target languages

equally well (even a native speaker of both) and even if he or she

does, it is still virtually impossible to know everything about any possible

subject matter related to the translation.

Scientists and

translators have been arguing and still do about the priorities in a

translators education. Some of them give priority to the linguistic

knowledge of translators, others keep saying that a knowledgeable

specialist m the given area with even a relatively

poor command of the language will be able to provide a more adequate translation than a good scholar of

the language with no special technical or natural science background .

In our opinion this argument

is counter-productive — even if one or another viewpoint is

proved, say, statistically, this will not add anything of value to the

understanding of translation.

However,

the very existence of this argument underscores the significance of

extra linguistic information for translation.

Summing

up this short overview of theoretical treatments of translation we would again

like to draw your attention to the general conclusion that any theory

recognizes the three basic component of translation and different approaches

differ only in the accents placed on this or that component So the basic components are:

Meaning of a word or word combination in the

source language (concept or concepts corresponding to this word

or word combination in the minds of the source language

speakers).

Extra linguistic information pertaining to the

original meaning and/or its conceptual equivalent after the

translation.

So, to put it differently, what you can do in translation

is either match individual words and combinations of the two languages

directly (transformational approach) or understand the content

of the source message and render it using the formal means of the target

language (denotative approach) with due regard of the translation

recipient and background information (communicational approach).

The hierarchy of these methods may be

different depending on the type of translation Approach depending

on the type of translation are given in Table below

|

Translation Type |

Translation |

|

Oral Consecutive |

Denotative, Communicational |

|

Oral |

Transformational, |

|

Written (general and |

Transformational |

|

Written (fiction and |

Denotative |

In

simultaneous translation as opposed to consecutive priority given to direct

transformations since a simultaneous interpreter

simply has no time for profound conceptual analysis.

In written translation when you seem to have

time for everything priority is also given to simple transformations (perhaps,

with exception of poetic translation).

It should be born in mind however, that in any

translation we observe a combination of different methods.

From the approaches discussed one should also

learn that the matching language forms and concepts are regular and irregular, that

seemingly the same concepts are interpreted differently by the speakers

of different languages and different translation users.

2.5

Translation and style

The problem of translation equivalence is closely connected with the stylistic aspect of translation

— one cannot reach the required level of equivalence if the stylistic

peculiarities of the source text are

neglected. Full translation adequacy includes as an obligatory component the adequacy of style, i.e. the right choice

of stylistic means and devices of the target language to substitute for those observed in the source text.

This means that in translation one is

to find proper stylistic variations of the original meaning rather than only

meaning itself. For example, if the text you’ll see, everything wills he hunky-dory is translated in neutral style (say,Увидишь…все будет хорошо) the basic meaning will be preserved but

colloquial and a bit vulgar connotation of the expression hunky-dory

will be lost. Only the stylistically correct equivalent of this expression

gives the translation the required adequacy. (e.g.Увидишь…все будет тип—топ).

Modern stylistics distinguishes the following

types of functional styles.

-Belles-lettres

(prose, poetry, drama):

-Publicist

style:

-Newspaper

style.

-Scientific

style:

-Official

documents

Any

comparison of the texts belonging to different stylistic varieties,

listed above will show that the last two of them (scientific style

variety and official documents) are almost entirely devoid

of stylistic devoid of stylistic coloring being characterized by

the neutrality of style whereas the first three (belles-lettres (prose,

poetry, drama), publicistic and newspaper style) are usually

rich in stylistic devices to which a translator ought to pay due

attention. Special language media securing the desirable communication

effect of the text are called stylistic devices and expression

means.

First of all a translator is

to distinguish between neutral, bookish and colloquial words and word

combinations, translating them by relevant

units of the target language. Usually it is a routine task. However, it sometimes is hard to determine the correct stylistic variety of a translation

equivalent, then – as almost all instances of translation — final decision is

on the basis of context, situation

and background information.

For example, it is hard to decide without

further information, which of the English words -disease, illness

or sickness — corresponds to the Russian words, болезнь and заболевание. However

even such short contexts as infectious disease and social disease

already help to choose appropriate equivalents and translate the word disease

as инфекционное заболевание and социальная болезнь. This

example brings are based us to a very important conclusion that

style is expressed in proper combination of words rather than only stylistic

coloring of the individual words. Stylistic devices are

based on the comparison of primary dictionary meaning and hat

dictated by the contextual environment on the contradiction between

the meaning of the given word and the environment, on the

association between words in the minds of the language speakers

and on purposeful deviation accepted grammatical and phonetic standards.

The following varieties of stylistic devices

and expression means are most common and frequently

dealt with even by the translators of non-fiction texts.

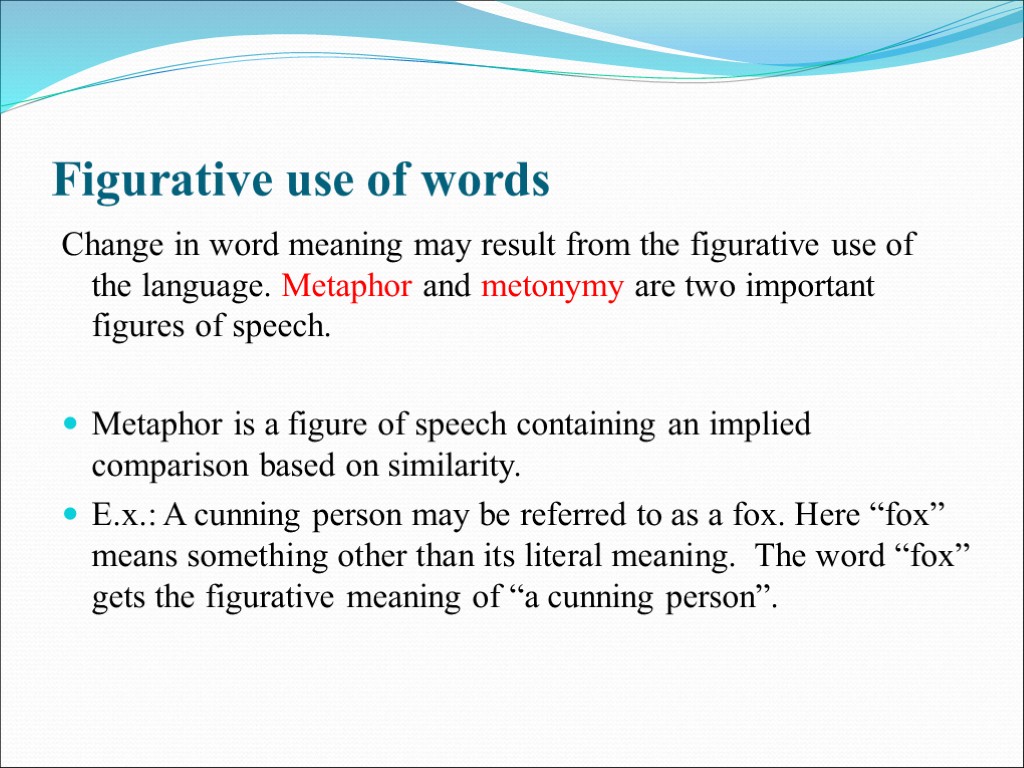

Metonymy is similarity by association; usually

one of the constituents of an object replaces the object itself.

As a rule translators keep to literal

translation when translating the cases of metonymy. For

example, crown (meaning the royal family) is usually translated as корона,hand-рука(e.g.

He is the right hand of the president),etc. Cases of irony do not

present serious problems for translation and the approaches similar to

those mentioned above (semantic or pragmatic equivalence) are

commonly used. For example, the ironical expression paper war may

be translated as (бумажная война or война бумаг)

Semantic and syntactic irregularities of expression used

as stylistic devices are called transferred qualifier and

zeugma, respectively.

A good example of a transferred qualifier is he paid his smiling

attention to … -here the qualifier smiling refers to a person,

but is used as an attribute lo the state attention.

Translator’s task is this case consist m

rendering the idea in compliance with the lexical combination

rules of the target language For instance, in Russian it may be expressed as (улыбаясь…)

Zeugma is also a semantic irregularity, e.g.

If one and the same verb is combined with two or more nouns and

acquires a different meaning in each of such combinations For

example. He has taken her and another cup tea. Here attain the

translator’s task is to try to render this ironical comment

either by finding a similar irregularity in the target language or

failing to show a zeugma land irony of the author) stick to regular target

language mean.-, (i.e. separate the two actions Он ее сфотографировал и выпил еще одну чашку чая or

try to lender them as a zeugma as well.Он сделал снимок и еще один глоток чая из чашки). A

pun (so called play of words’) is

righteously considered the most difficult for translation, Pun is the realization in one and the same word of two lexical meanings simultaneously.

A pun can be translated only by a word in the

target language with similar capacity to develop two meanings in

a particular context. English is comparatively rich in polysems and homonyms,

whereas in Russian these word types are rather rare. Let’s

take an example of a pun and its fairly good Russian translation.

-What,

gear were you in al the moment of impact?

—Gucci‘s sweats and Reebok.

-На какой передаче вы были в момент столкновения

-“Последние известия”

Another stylistic device is a paraphrase. Its

frequent use is characteristic of the

English language. Some of the paraphrases are borrowed from classical cources (myths and the Bible): others are

typically English. To give an example, the paraphrases of the classical origin are «Beware (ireeks… », Prodigal

son (Бойтесь данайцев) whereas «Lake Country» «Озерный край»

is a typically English paraphrase. As a rule paraphrases do not

present difficulties for translation however their correct translation

strongly depends on situation and appropriate background information

.

Special

attention is to be paid by a translator to overt and covert

quotations Whereas the former require only correct rendering of the source

quotation in the target language (Never suggest your own home-made

translation for a quotation of a popular author), the latter

usually takes the shape of an allusion and the pragmatic

equivalence seems the most appropriate for the ase For example, «the

Trojan horse raid one may translate as нападение, коварный, троянский конь(i.e.

preserving the allusion) or as коварное нападение (loosing

the meaning of the original quotation)

A

translator is to be ready to render dialect forms and illiterate

speech in the target language forms. It goes without saying

that one cans hardly lender, say, cockney dialect using the Western Ukrainian

dialect forms. There is no universal recipe for tins translation

problem. In some cases the distortions in the target

grammar

are used to render the dialect forms but then again it is not

‘a cure-all and each such case requires an individual approach.

Thus, any good translation should be fulfilled with due

regard of the stylistic peculiarities of the source text and this

recommendation applies to all text types rather than only to fiction.

PART 3. THE WAYS OF WORDS AND

SENTENCES TRANSLATION

3.1 MORPHOLOGICAL CORRESPONDENCE

Every

language has a specific system which differs from that of any other. This is

all the more so with respect to English and Russian, whose grammatical

systems are I typologically and genetically heterogenous.

English and Russian belong to the Germanic and Slavonic groups

respectively of the Indo-European family of languages; the

Kazakh language pertains to the Turkic group of the Altaic family. Concerning

the morphological type both English and Russian are inflected, though

the former is notable for its analytical character and the latter for its

synthetic character in the main. Kazakh is an agglutinative language.

As to grammar the principal means of

expression in languages possessing an analytical character (English) is

the order of words and use of function words (though all the four

basic grammatical means—grammatical inflections, function words,

word

order and intonation pattern—are found in any language). The

other two means are of secondary importance.

The grammatical inflections are the principal

means used in such languages as Russian and though the rest of

grammatical

means are also used but they are of less

frequency than the grammatical inflections.

The

comparison of the following examples will help to

illustrate the difference between the languages considered: The

hunter killed the wolf.

English the order of words is fixed. The model of

simple declarative sentences in this

language is as follows:

Subject

— Predicate

This

means that the subject (S) is placed in the first position and the predicate

(V)—in the second position. If the predicate is expressed by a

transitive verb then in the third position we find the

object (0), that is S—Vtr—0

Any violation of this order of words brings

about a change or distortion of the meaning.

The corresponding Russian sentence adheres to the pattern

S—Vtr—0. But it permits the transposition of the words, i.e. Russian models by the order of wards and morphological arrangement of

the object which may be marked or unmarked.

These

patterns are not equivalent. The first allows transposition of

words, which leads to stylistic marking (characteristic of poetry).

Besides, the ending «HИ» expresses an additional

meaning of definiteness. The second pattern does not tolerate transposition of words.

The

principal types of grammatical correspondences;

a)

complete correspondence;

b)

partial correspondence;

c)

the absence of correspondence.

COMPLETE

MORPHOLOGICAL CORRESPONDENCE Complete morphological

correspondence is observed when in the languages considered

there are identical grammatical categories with identical particular meanings.

In

all the three languages there is a grammatical category of number

both the general categorical and particular meanings are alike;

Number

Singular

Plural

Such

correspondence may be called complete PARTIAL MORPHOLOGICAL CORRESPONDENCE.

Partial morphological correspondence is

observed when in the languages examined there are grammatical categories with identical

categorical meanings but with some differences in their particular

meanings.

In the languages considered there is a grammatical category

of case in nouns. Though the categorical meaning is identical

hi all the three languages the particular meanings are different both from the

point of view of their number and the meanings they express.

English has two particular meanings while Russian have

six. Though the latter two languages have the same quantity of particular cases, their meanings do

not coincide.

The

differences in the case system or in any other

grammatical categories are usually expressed by other means in

languages.

ABSENCE OF

MORPHOLOGICAL CORRESPONDENCE

Absence of morphological correspondence

is observed when there are not corresponding grammatical

categories in the languages examined. As for instance in Russian there is a

grammatical category of possessiveness, which shows the affixation of things to one of the three grammatical persons.

English

my book

your

book

his,

her, its book

In English we use certain grammatical means to

express a definite and indefinite meanings, that is articles. But

there are no equivalent grammatical means in Kazakh and Russian. They

use lexical or syntactic means to express those meanings.

(See Substitution.)

3.2 COMPLETE

SYNTACTIC CORRESPONDENCE

By complete syntactic correspondence is

understood the conformity m structure and sequence of words in word-combinations

and sentences.

Complete syntactic correspondence is rarely to

be found in the languages examined here. However, the pattern adj + N

is used in word-combination: red flags. The same may be said of

sentences

in

cases when the predicate of a simple sentence is expressed by an intransitive

verb: He laughed.

PARTIAL SYNTACTIC

CORRESPONDENCE

By partial syntactic correspondence in

word-combinations is understood the conformity in meaning but

discrepancy in the structure of phrase.

Partial syntactic correspondence in word-combinations

are found in the following patterns:

Attributes

formed by the collocation of words. Owing to [the fact that English

is poor in grammatical inflections, attributes are widely formed by means of

mere collocation of words in accordance with (lie pattern Nl +N2)

which expresses the following type of relations.

ABSENCE

OF SYNTACTIC CORRESPONDENCE

1. By

absence of syntactic correspondence we mean lack of certain syntactic

constructions in the Target language, which were used in the Source language.

In English this concerns syntactic constructions with

non-finite forms of the verb which compose the extended part of a sentence with

an incomplete or secondary predication. The semantic function of predicative

constructions can be formulated as intercommunication and

interconditionality of actions or states with different subjects.

These constructions have no formal grammatical connection with the

main parts of sentences, though there, is always a conformity between

them. The degree of attendancy of action or conditions in

predicative constructions determines the choice of complex, compound

or simple sentences in translation.

Compare:

I heard the door open .. .

In

the English sentence the predicative construction which

functions

as an object is composed of a noun in the common case and

an infinitive. In Kazakh this construction corresponds to the word-combination

which carries out the same function, though there is neither structural

nor morphological conformity; it is a word combination expressed by

a noun and participle. Thus, an English predicative

construction when translated into Kazakh gets nominalized. In

Russian this construction is expressed by a complex sentence with a

subordinate object clause.

3.3 TYPES

OF GRAMMATICAL TRANSFORMATIONS

In

order to attain the fullest information from one language into

another one is obliged to resort to numerous interlinguistic lexical

and grammatical transformations.

Grammatical

transformations are as follows;

l) substitution,

2) transposition,

3) omission,

4) supplementation.

The

cited types of elementary transformations as such are rarely used in the

process of translating. Usually they combine with each other,

assuming the nature of «complex» interlinguistic transformations.

1.

Substitution. By substitution we understand the substitution of

one

part of speech by another or one form of a word by another.

Consequently there are two kinds of substitution constituting a grammatical

type of transformation: substitution of parts of speech and the

grammatical form of a word.

Transformation

by substitution may be necessitated by several reasons: the

absence of one or an other grammatical form or

construction m the Target language; lack of coincidence in the ire of corresponding forms and constructions ac

well as lexical reasons-

different combinability and use of words, lack of a part of speech with the same meaning.

An example of the substitution of a word-form

may be the interpretation of the meaning of the grammatical category of

posteriority of an English verb, which is presented in two particular

meanings: absolute posteriority (He says lie

will come) and relative posteriority (He said he would come). Kazakh

and Russian verbs do not possess word-forms of this kind and communicate

their meaning with use of other grammatical means;

In Kazakh the meaning of this category is expressed by a substantivized

participle ending m or by the infinitive ending in; in

Russian the future tense form of a verb is used.

There

are two types of substitution of parts of speech: obligatory

and non obligatory. The obligatory substitution is observed

when in the Target language, there is no part of speech corresponding

to that used in the Source language, e. g. the English articles.

Apart from other functions (he article

may function as an indefinite or demonstrative

pronoun, a numeral, and may be used for emphasis. In cases of this kind it is necessary to substitute them with functionally—adequate means of expression in

Kazakh and Russian.

E.g. When

we were in Majorca, there was a Mrs. Leech there

and slie was telling us most wonderful things about you. (A.

Christie)

In

Kazakh and Russian an indefinite pronoun is used

for translating

the indefinite article.

Non

obligatory substitution is a substitution undertaken by the

needs or demands of the context:

The

climb had been easier than he expected. A noun in the English

sentence is substituted by infinitives in the Kazakh and Russian languages.

2. Transposition.Transposition (as a

type of transformation used in translations) is understood to be

the change of position (order) of linguistic elements in the Target language in

comparison with the Source language.

Transposition (change in the structure of a sentence) is necessitated

by the «difference in the structure of the language (fixed

or free order of words etc.), in the semantic of a sentence, and

others. There are two types of transpositions; transposition (or substitution)

of parts of a sentence and transposition occasioned by the

change of types of syntactic connection in a composite sentence. Examples:

Active defenders of the national interests of their people, the Communists, are

at the same time true internationalists. (W. Foster.)

The

first component of the English attributive word-combination “active

defenders” is an adverb while the second becomes the predicate when

translated into Kazakh. In Russian the same word-combination is

expressed by an adverbial word combination. The means used to express

the semantic core of a statement may not be identical. In English the

indefinite article, the construction it is … that (who),

inversions of different kinds are used for this purpose, while the

order of words is the most frequent means of expression in Kazakh

and Russian: words, communicating new information are not placed

at the beginning of the sentence:

A big scarlet Rolls Royce had just stopped in front of the

local post office.

In the English

sentence the semantic core is expressed by the indefinite article while in Kazakh and Russian it is assigned to the

second and third places accordingly.

When translating English compound sentences

into Kazakh and Russian, the principal and subordinate clauses may be transposed.

This is explained by the fact that the order of words in

compound sentences does not always coincide in the languages considered.

Compare:

A remarkable air of relief overspread her countenance as soon

as she saw me. (R. Stevenson.)

3. Omission. As a type of grammatical transformation-omission is necessitated by grammatical redundancy of certain forms in two languages.

He

raised his hand.

4. Addition. Addition, as a type of grammatical

transformation, can be met with cases

of forma! inexpressive-

ness of grammatical or semantic

components in the language of the original text.

Also,

there was an awkward hesitancy at times, as he essayed the new words he had

learnt.

It must be emphasized that the division into

lexical and grammatical transformations is, to a

great extent, approximate and conditional. In some cases a

transformation can be interpreted as one or another type of elementary

transformation. In practice the cited types of lexical and

grammatical transformations are seldom met with in «pure form».

Frequently they combine to form complex transformations.

CONCLUSION

Roughly, the human

translation theories may be divided into three main groups which

quite conventionally may be called transformational approach,

denotative approach, and communicational approach.

The transformational

theories consist of many varieties which may have different

names but they all have one common feature: die process of

translation is regarded as transformation. Within

the group of theories which we include in the transformational

approach a dividing line is sometimes drawn between transformations and equivalencies

.

According to this interpretation a

transformation arts at the syntactic level when there is a change, i.e.

when we alter, say, the word order during translation.

Substitutions at other levels are regarded as equivalencies,

for instance, when we substitute words of the target language for

those of the source, this is considered as an

equivalence.

In the transformational approach we

shall distinguish three levels of substitutions: morphological

equivalencies, lexical equivalencies, and syntactic

equivalencies and. or transformations.

In the

process of translation:

-at the morphological level morphemes (both word-building

and word-changing) of the target language are substituted for

those of the source;

-at the lexical level words and word combinations of the target language are substituted for those of the

source;

-at the syntactic level syntactic structures

of the target

language

are substituted for those of the source.

The syntactic transformations in translation

comprise a broad range of structural changes in the target text,

starting from the reversal of the word order in a sentence and finishing with division

of the source sentence into two and move target ones.

Appendix

Blitzkrieg молниеносная война.

Comprehensive

Programmed of Disarmament n Всеобъемлющая программа разоружения.

International Nuclear

Information System n международная система ядерной информации.

National Guard n Национальная

гвардия

abet resistance v оказывать

поддержку движению сопротивления(vi)

abrogated a treaty v расторгнул

договор

(vi).

1. abrogating a

convention n расторжение договора.

2. abrogating a convention

v расторгающий договор(vi). absolute rule n

самовластие.

3. absolute war n решительные

боевые действия

accelerate upon an agreement v ускорять достижение соглашения(vi).

1. adhering to treaty provisions n соблюдение положений договора.

2. adhering to treaty provisions v соблюдающий положения договора(vi)

adjustment of disputes n урегулирование разногласий, administration of

peace-keeping operations n осуществление операций по поддержанию мира.

bar the way to war v преграждать путь к войне (vi)

.

basic war plan n основной

стратегический план.

beam the opposition v подавлять

сопротивление(vi).

brush blaze n локальная

война

brush fire war n местная война

call to the colors v

объявлять мобилизацию(vi).

carried the day v одержал победу(vi).

challenge to the

world community n вызов международному сообществу.

change in a policy n смена политики.

chemical warfare agreement n соглашение

о запрещении химического оружия.

circumvention of an

agreement n обход соглашения.

claims to world superiority n притязания на мировое господство.

comparison of military expenditures in

accordance with international

standards n сопоставление

военных бюджетов по международным стандартам

compensation allowance

n денежная компенсация.

competitive co—existence n сосуществование

в условиях соперничества.

completion of talks n завершение

переговоров.

compliance with

commitments n соблюдение обязательств.

conduct an arms race

v вести гонку вооружений(vi).

conduct diplomacy v проводить дипломатию (vi).

conduct of

disarmament negotiations n ведение переговоров по разоружению.

consolidation of

peace n укрепление мира.

construction of

all-embracing system of international security n

создание

всеобъемлющей системы международной безопасности..

consultative board

n.консультативный совет

contending nation n. воюющее государство.

contest the air v оспаривать

господство в воздухе

control agency n. орган управления.

convene a meeting v созывать совещание

convene the UN Security Council v созывать Совет Безопасности OOH (vi).

conventional armament

n. обычное вооружение

desperate situation n отчаянное положение

dentist n сторонник разрядки международной

напряженности deterioration of resistance nослабление сопротивления

diminished

international tension n. спад международной безопасности

diplomatic attack n дипломатическая атака

diplomatic

co-operation n дипломатическое сотрудничество

diplomatic decision

n. дипломатическое решение

disarmament issue n. проблема

разоружения.

Bibliography

1.

Chafe

WX. Meaning and the structure of language. Chicago, 1971

2. Catford J.A.

Linguistic theory of translation. London,1967

3. Firth J.R. Linguistic analysis and

translation. The Hague, 1956

4. Grishman R. Communicational Linguistics:

an introduction. Cambridge,

1987

5. Hornby A.S. Oxford

Advanced Learners Dictionary of Current English.

Oxford, 1982

6. Hiroaki Kitano.

Speech-to-speech translation. Boston, 1994

7. Solomon L.B.

Semantic and common sense. New York, 1966

8. Бархударов Л.С. Язык и

перевод. Международные

отношения.Москва,1975

lO.Глушко

М.М.,Карулина Ю.А. Текстология английской научной

речи. МГУ,

Москва,1978

ll. Левицкая

Т.Р., Фитерман А.М. Пособие по переводу с английского

языка на

русский. Высш.шк.Москва,1973

12. Комиссаров В.Н. Лингвистика

перевода.Москва,,1981

13. Комиссаров В.Н. Слово о

переводе.Москва,1973

14. Мирам Г.Э.

Профессия-переводчик.К.,1999

15. Мирьяр-Белоручев Р.К. Теория и

методы перевода.Московский

лицей.Москва,1996

16. Рецкер Я.И. теория

перевода и переводческая

практика.Москва,1974

17. Швейцер А.Д.

теория перевода.

Статус,проблемы,аспекты.Наука.Москва,1988

18. Щвейцер А.Д.

Перевод

лингвистика.Москва,1980

19. Шевякова В.Е.

Современный

английский

язык.Наука.Москва,1980

20. Федоров А.В.

Основы

общей теории

перевода-

лингвистические

проблемы

21. www.tanslateweb.org

22.kz.wikipedia.org

23. www.longman.com 24.www.multitran.ru

TYPES OF LEXICAL TRANSFORMATIONS

In order to attain equivalence, despite the difference in formal and semantic systems of

two languages, the translator is obliged to do various linguistic transformations. Their aims are:

to ensure that the text imparts all the knowledge inferred in the original text, without violating

the rules of the language it is translated into.

The following three elementary types are deemed most suitable for describing all kinds of lexical

transformations:

1fexical substitutions;

2. Supplementations;

3. Omissions (dropping)

1

.

1. Lexical substitutions. 1) In substitutions of lexical units words and stable word

combinations are replaced by others which are not their equivalents. More often three cases are

met with: a) a concrete definition —replacing a word with a broad sense by one of a narrower

meaning (He is at school. —У мактабда ўқийди.—

OH УЧИТСЯ В ШКОЛЕ

; He is in the army. —

У армияда хизмат киляпти;

OH СЛУЖИТ В АРМЕ

; b) generalization —replacing a word with a

narrow meaning by one with a broader sense: a navajo blanket—жун адёл, индейское одеяло;

c) an integral transformation (How do you do! — Caлом! — Здравствуйте!).

2) Antonymous translation is a complex lexico-grammatical substitution of a positive

construction for a negative one (and vice versa), which is coupled with a replacement of a word

by its antonym when translated (Keep off grass — Maйca ycтидан юрманг —Не ходите по

траве).

3) Compensation is used when certain elements in the original text cannot be expressed in

terms of the language it is translated into. In cases of this kind the same information is

communicated by other means or in another place so as to make up the semantic deficiency. ( .. .

He was ashamed of his parents…., because they said «he don’t» and «she don’t»… —

(Селинджер) — У ўз ота-онасидан уяларди, чунки улар сўзларни нотўғри талаффуз

қилардилар. …Он стеснялся своих родителей, потому что они говорили «хочут» и

«хочете» (перевод Р. Райт — Ковалевой)

2. Supplementations. A formal inexpressibility of semantic components is the reason

most met with for using supplementations as a way of lexical transformation. A formal

inexpressibility of certain semantic components is especially of English wordcombinations N

+ N and Adj. 4- N: Pay claim — Иш хакини ошириш талаби. — Требование повысить

заработную плату; Logical computer. —Логик операцияларни бажарувчи ҳисоблаш

машинаси — комьпютер.

3. Omissions (dropping). In the process of lexical transformation of omission generally

words with a surplus meaning are omitted (e. g. components of typically English pair — syn-

onyms, possessive pronouns and exact measures) in order to give a more concrete expression. To

raise one’s eyebrows —Ялт этиб карамок— поднять брови (в знак изумления)

III. ABSENCE OF LEXICAL CORRESPONDENCES

Realiae are words denoting objects, phenomena and so on, which are typical of a people.

In order to render correctly the designation of objects referred to in the original and image

associated with them it is necessary to know the tenor of life epoch and specific features of the

country depicted in the original work.

The following groups of words can be regarded as having no equivalents: realiae of

everyday life — words denoting objects, phenomena etc. which typical of a people (cab, fire —

place); 2) proper names and geographies! denominations; 3) addresses and greetings; 4) the titles

of journals, magazines and newspapers; 5) weights, linear measures etc.

When dealing with realiae it is necessary to take special account of the pragmatic aspect

of the translation, because the “knowledge gained by experiences” of the participants of the

communicative act turns out to be different. As a result, much of which is easily understood by

an Englishman is in comprehensible to an Uzbek or Russian readers or exerts the opposite

influence upon them. It is particularly important to allow for the pragmatic factor when

translating fiction, foreign political propaganda material and advertisements of articles for export

Below are three principal ways of translating words denoting specific realiae:

1) transliteration (complete or partial), i. e, the direct use of a word denoting realiae or its

root in the spelling or in combination with suffixes of the mother tongue (cab, дўппи, садал,

изба);

2) creation of new single or complex word for denoting an object on the basis of elements

and morphological relationship in the mother tongue (skyscraper — oсмонўпар, небо-скрёб);

3) use of a word denoting something close to (though not identical with) realiae of

another language. It represents an approximate translation specified by the context, which is

sometimes on the verge of description. (Pedlar —тарқатувчи- торговец- разносчик)

PHRASEOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF TRANSLATION

Translating a phraseological unit is not an easy matter as it depends on several factors:

different combinability of words, homonymy, and synonymy, polysemy of phraseological units

and presence of falsely identical units, which makes it necessary to take into account of the

context. Besides, a large number of phraseological units have a stylistic-expressive component in

meaning, which usually has a specific national feature. The afore-cited determines the necessity

to get acquainted with the main principles of the general theory of phraseology.

The following types of phraseological units may be observed: phrasemes and idioms. A

unit of constant context consisting of a dependent and a constant indicators may be called a

phraseme. An idiom is a unit of constant context which is characterized by an integral meaning

of the whole and by weakened meanings of the components, and in which the dependant and the