© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy

Religion

Nearly 86% of the world’s population is religious, including all religions. In numerous countries, religion guides social behavior and plays a significant role in daily life.

Religion is an organized collection of belief systems, cultural systems, and world views that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to explain the origin of life or the Universe. From their ideas about the cosmos and human nature, they tend to derive morality, ethics, religious laws or a preferred lifestyle. According to some estimates, there are roughly 4,200 religions in the world.

Many religions may have organized behaviors, clergy, a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership, holy places, and scriptures. The practice of a religion may also include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration of a deity, gods or goddesses, sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trance, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, prayer, music, art, dance, public service or other aspects of human culture. Religions may also contain mythology.

The word religion is sometimes used interchangeably with faith or belief system; however religion differs from private belief in that it is “something eminently social”.

Note: Don’t miss these additions to the main article (scroll down):

– Religion and Violence

– In the name of God

– War and Peace

Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents

The following world religions listing is derived from the statistics data in the Adherents.com database (with an update from CIA World Factbook 2010).

This listing is not a comprehensive list of all religions (there are distinct religions other than the ones listed below), however it accounts for the religions of over 98% of the world’s population.

|

(Sizes shown are approximate estimates, and are here mainly for the purpose of ordering the groups, not providing a definitive number. This list is sociological/statistical in perspective.)

Note: Mandeans, PL Kyodan, Ch’ondogyo, Vodoun, New Age, Seicho-No-Ie, Falun Dafa/Falun Gong, Taoism, Roma are religions, but have not been included in this list of major religions primarily for one or more of the following reasons:

- They are not a distinct, independent religion, but a branch of a broader religion/category.

- They lack appreciable communities of adherents outside their home country.

- They are too small (even smaller than Rastafarianism).

Prevailing World Religions Map

Map Source: Wikipedia

Click to Enlarge

This drawing is copied from the Wikipedia web site at: http://en.wikipedia.org/ and is shown here under terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Sources:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Major_religious_groups

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion

- http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html

The information provided below is intended to provide a short introduction to the major world religions as defined classically. Each description has been kept very short so that it is easy to read straight through all of them and get a general impression of the diversity of spiritual paths humanity takes to live the kind of life God wants. As a result, a great many things have been omitted. No omissions are intentional and readers are encouraged to consult other resources on the web as well as books for more in-depth information.

Hinduism – 4000 to 2500 BCE

The origins of Hinduism can be traced to the Indus Valley civilization sometime between 4000 and 2500 BCE. Though believed by many to be a polytheistic religion, the basis of Hinduism is the belief in the unity of everything. This totality is called Brahman. The purpose of life is to realize that we are part of God and by doing so we can leave this plane of existance and rejoin with God. This enlightenment can only be achieved by going through cycles of birth, life and death known as samsara. One’s progress towards enlightenment is measured by his karma. This is the accumulation of all one’s good and bad deeds and this determines the person’s next reincarnation. Selfless acts and thoughts as well as devotion to God help one to be reborn at a higher level. Bad acts and thoughts will cause one to be born at a lower level, as a person or even an animal.

Hindus follow a strict caste system which determines the standing of each person. The caste one is born into is the result of the karma from their previous life. Only members of the highest caste, the brahmins, may perform the Hindu religious rituals and hold positions of authority within the temples.

Angkor Wat is the largest Hindu temple complex and the largest religious monument in the world.

More Resources on Hinduism

Sacred Texts of Hinduism – Hindu sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Hinduism at OCRT – Article on Hinduism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Judaism – 2000 BCE

Judaism, Christianity, Islam and the Baha’i faith all originated with a divine covenant between the God of the ancient Israelites and Abraham around 2000 BCE. The next leader of the Israelites, Moses, led his people out of captivity in Egypt and received the Law from God. Joshua later led them into the promised land where Samuel established the Israelite kingdom with Saul as its first king. King David established Jerusalem and King Solomon built the first temple there. In 70 CE the temple was destroyed and the Jews were scattered throughout the world until 1948 when the state of Israel was formed.

Jews believe in one creator who alone is to be worshipped as absolute ruler of the universe. He monitors peoples activities and rewards good deeds and punishes evil. The Torah was revealed to Moses by God and can not be changed though God does communicate with the Jewish people through prophets. Jews believe in the inherent goodness of the world and its inhabitants as creations of God and do not require a savior to save them from original sin. They believe they are God’s chosen people and that the Messiah will arrive in the future, gather them into Israel, there will be a general resurrection of the dead, and the Jerusalem Temple destroyed in 70 CE will be rebuilt.

Western wall jerusalem. Credit: Wayne McLean, Wikipedia

More Resources on Judaism

Sacred Texts of Judaism – Jewish sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Judaism at OCRT – Article on Judaism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Zoroastrianism – 1000 BCE

Zoroastrianism was founded by Zarathushtra (Zoroaster) in Persia which followed an aboriginal polytheistic religion at the time. He preached what may have been the first monotheism with a single supreme god, Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrians belief in the dualism of good and evil as either a cosmic one between Ahura Mazda and an evil spirit of violence and death, Angra Mainyu, or as an ethical dualism within the human consciousness. The Zoroastrian holy book is called the Avesta which includes the teachings of Zarathushtra written in a series of five hymns called the Gathas. They are abstract sacred poetry directed towards the worship of the One God, understanding of righteousness and cosmic order, promotion of social justice, and individual choice between good and evil. The rest of the Avesta was written at a later date and deals with rituals, practice of worship, and other traditions of the faith.

Zoroastrians worship through prayers and symbolic ceremonies that are conducted before a sacred fire which symbolizes their God. They dedicate their lives to a three-fold path represented by their motto: “Good thoughts, good words, good deeds.” The faith does not generally accept converts but this is disputed by some members.

More Resources on Zoroastrianism

Sacred Texts of Zoroastrianism – Zoroastrian sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Zoroastrianism at OCRT – Article on Zoroastrianism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Buddhism – 560 to 490 BCE

Buddhism developed out of the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama who, in 535 BCE, reached enlightenment and assumed the title Buddha. He promoted ‘The Middle Way’ as the path to enlightenment rather than the extremes of mortification of the flesh or hedonism. Long after his death the Buddha’s teachings were written down. This collection is called the Tripitaka. Buddhists believe in reincarnation and that one must go through cycles of birth, life, and death. After many such cycles, if a person releases their attachment to desire and the self, they can attain Nirvana. In general, Buddhists do not believe in any type of God, the need for a savior, prayer, or eternal life after death. However, since the time of the Buddha, Buddhism has integrated many regional religious rituals, beliefs and customs into it as it has spread throughout Asia, so that this generalization is no longer true for all Buddhists. This has occurred with little conflict due to the philosophical nature of Buddhism.

More Resources on Buddhism

Sacred Texts of Buddhism – Buddhist sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Buddhism at OCRT – Article on Buddhism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Shinto – 500+ BCE

Shinto is an ancient Japanese religion, closely tied to nature, which recognizes the existance of various “Kami”, nature dieties. The first two deities, Izanagi and Izanami, gave birth to the Japanese islands and their children became the deities of the various Japanese clans. One of their daughters, Amaterasu (Sun Goddess), is the ancestress of the Imperial Family and is regarded as the chief deity. All the Kami are benign and serve only to sustain and protect. They are not seen as separate from humanity due to sin because humanity is “Kami’s Child.” Followers of Shinto desire peace and believe all human life is sacred. They revere “musuhi”, the Kami’s creative and harmonizing powers, and aspire to have “makoto”, sincerity or true heart. Morality is based upon that which is of benefit to the group. There are “Four Affirmations” in Shinto:

- Tradition and family: the family is the main mechanism by which traditions are preserved.

- Love of nature: nature is sacred and natural objects are to be worshipped as sacred spirits.

- Physical cleanliness: they must take baths, wash their hands, and rinse their mouth often.

- “Matsuri”: festival which honors the spirits.

More Resources on Shinto

Sacred Texts of Shinto – Shinto sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Shinto at OCRT – Article on Shinto at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Confucianism – 500 BCE

K’ung Fu Tzu (Confucius) was born in 551 BCE in the state of Lu in China. He traveled throughout China giving advice to its rulers and teaching. His teachings and writings dealt with individual morality and ethics, and the proper exercise of political power. He stressed the following values:

- Li: ritual, propriety, etiquette, etc.

- Hsiao: love among family members

- Yi: righteousness

- Xin: honesty and trustworthiness

- Jen: benevolence towards others; the highest Confucian virtue

- Chung: loyalty to the state, etc.

Unlike most religions, Confucianism is primarily an ethical system with rituals at important times during one’s lifetime. The most important periods recognized in the Confucian tradition are birth, reaching maturity, marriage, and death.

More Resources on Confucianism

Sacred Texts of Confucianism – Confucian sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Confucianism at OCRT – Article on Confucianism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Jainism – 420 BCE

The founder of the Jain community was Vardhamana, the last Jina in a series of 24 who lived in East India. He attained enlightenment after 13 years of deprivation and committed the act of salekhana, fasting to death, in 420 BCE. Jainism has many similarities to Hinduism and Buddhism which developed in the same part of the world. They believe in karma and reincarnation as do Hindus but they believe that enlightenment and liberation from this cycle can only be achieved through asceticism. Jains follow fruititarianism. This is the practice of only eating that which will not kill the plant or animal from which it is taken. They also practice ahimsa, non-violence, because any act of violence against a living thing creates negative karma which will adversely affect one’s next life.

Jain temples, Palitana, India. Source: Wikipedia

More Resources on Jainism

Sacred Texts of Jainism – Jain sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Jainism at OCRT – Article on Jainism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Taoism – 440 CE

Taoism was founded by Lao-Tse, a contemporary of Confucius in China. Taoism began as a combination of psychology and philosophy which Lao-Tse hoped would help end the constant feudal warfare and other conflicts of his time. His writings, the Tao-te-Ching, describe the nature of life, the way to peace and how a ruler should lead his life. Taoism became a religion in 440 CE when it was adopted as a state religion.

Tao, roughly translated as path, is a force which flows through all life and is the first cause of everything. The goal of everyone is to become one with the Tao. Tai Chi, a technique of exercise using slow deliberate movements, is used to balance the flow of energy or “chi” within the body. People should develop virtue and seek compassion, moderation and humility. One should plan any action in advance and achieve it through minimal action. Yin (dark side) and Yang (light side) symbolize pairs of opposites which are seen through the universe, such as good and evil, light and dark, male and female. The impact of human civilization upsets the balance of Yin and Yang. Taoists believe that people are by nature, good, and that one should be kind to others simply because such treatment will probably be reciprocated.

Originally known as the “Rock of Immortals”, the statue is believed to represent Laozi, the founder of Taoism. The carved stone sage still looks surprisingly good despite its approximate thousand year age. Image Source >>

More Resources on Taoism

Sacred Texts of Taoism – Taoist sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Taoism at OCRT – Article on Taoism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Exploring Tao with Fun – Informative site written by Taoists for beginners and non-beginners.

Images of Taoism from Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching – Illustrated Tao Te Ching based on Jeff Rasmussen’s “Spirit of Tao Te Ching”, introduction to Taoism, literal pictograph-by-pictograph translation, annotated links.

Christianity – 30+ CE

Christianity is a monotheistic and Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings. Most adherents of the Christian faith, known as Christians, believe that Jesus is the Son of God, fully divine and fully human and the savior of humanity prophesied in the Old Testament. Consequentially, Christians commonly refer to Jesus as Christ or Messiah.

Christianity represents about a third of the world’s population and is the world’s largest religion.

The foundation of Christian theology is expressed in the early ecumenical creeds which contain claims predominantly accepted by followers of the Christian faith. These professions state that Jesus suffered, died, was buried, and was subsequently resurrected from the dead in order to grant eternal life to those who believe in him and trust him for the remission of their sins. They further maintain that Jesus bodily ascended into heaven where he rules and reigns with God the Father. Most denominations teach that Jesus will return to judge all humans, living and dead, and grant eternal life to his followers. He is considered the model of a virtuous life, and his ministry, crucifixion, and resurrection are often referred to as the gospel, meaning “Good News”.

Jesus, the son of the Virgin Mary and her husband Joseph, but conceived through the Holy Spirit, was bothered by some of the practices within his native Jewish faith and began preaching a different message of God and religion. During his travels he was joined by twelve disciples who followed him in his journeys and learned from him. He performed many miracles during this time and related many of his teachings in the form of parables. Among his best known sayings are to “love thy neighbor” and “turn the other cheek.” At one point he revealed that he was the Son of God sent to Earth to save humanity from our sins. This he did by being crucified on the cross for his teachings. He then rose from the dead and appeared to his disciples and told them to go forth and spread his message.

Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the mid-1st century. Originating in the Levant region of the Middle East, it quickly spread to Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and Egypt. It grew in size and influence over a few centuries, and by the end of the 4th century had become the official state church of the Roman Empire, replacing other forms of religion practiced under Roman rule. During the Middle Ages, most of the remainder of Europe was Christianized, with Christians also being a sometimes large religious minority in the Middle East, North Africa, Ethiopia and parts of India. Following the Age of Discovery, through missionary work and colonization, Christianity spread to the Americas, Australasia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the rest of the world. Christianity has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization.

Since Christianity and Judaism share the same history up to the time of Jesus Christ, they are very similar in many of their core beliefs. There are two primary differences. One is that Christians believe in original sin and that Jesus died in our place to save us from that sin. The other is that Jesus was fully human and fully God and as the Son of God is part of the Holy Trinity: God the Father, His Son, and the Holy Spirit. All Christians believe in heaven and that those who sincerely repent their sins before God will be saved and join Him in heaven. Belief in hell and satan varies among groups and individuals.

There are a multitude of forms of Christianity which have developed either because of disagreements on dogma, adaptation to different cultures, or simply personal taste. For this reason there can be a great difference between the various forms of Christianity they may seem like different religions to some people.

Basic Groupings

Catholicism (or Roman Catholicism): This is the oldest established western Christian church and the world’s largest single religious body. It is supranational, and recognizes a hierarchical structure with the Pope, or Bishop of Rome, as its head, located at the Vatican. Catholics believe the Pope is the divinely ordered head of the Church from a direct spiritual legacy of Jesus’ apostle Peter. Catholicism is comprised of 23 particular Churches, or Rites – one Western (Roman or Latin-Rite) and 22 Eastern. The Latin Rite is by far the largest, making up about 98% of Catholic membership. Eastern-Rite Churches, such as the Maronite Church and the Ukrainian Catholic Church, are in communion with Rome although they preserve their own worship traditions and their immediate hierarchy consists of clergy within their own rite. The Catholic Church has a comprehensive theological and moral doctrine specified for believers in its catechism, which makes it unique among most forms of Christianity.

Mormonism (including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints): Originating in 1830 in the United States under Joseph Smith, Mormonism is not characterized as a form of Protestant Christianity because it claims additional revealed Christian scriptures after the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. The Book of Mormon maintains there was an appearance of Jesus in the New World following the Christian account of his resurrection, and that the Americas are uniquely blessed continents. Mormonism believes earlier Christian traditions, such as the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant reform faiths, are apostasies and that Joseph Smith’s revelation of the Book of Mormon is a restoration of true Christianity. Mormons have a hierarchical religious leadership structure, and actively proselytize their faith; they are located primarily in the Americas and in a number of other Western countries.

Jehovah’s Witnesses structure their faith on the Christian Bible, but their rejection of the Trinity is distinct from mainstream Christianity. They believe that a Kingdom of God, the Theocracy, will emerge following Armageddon and usher in a new earthly society. Adherents are required to evangelize and to follow a strict moral code.

Orthodox Christianity: The oldest established eastern form of Christianity, the Holy Orthodox Church, has a ceremonial head in the Bishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), also known as a Patriarch, but its various regional forms (e.g., Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, Ukrainian Orthodox) are autocephalous (independent of Constantinople’s authority, and have their own Patriarchs). Orthodox churches are highly nationalist and ethnic. The Orthodox Christian faith shares many theological tenets with the Roman Catholic Church, but diverges on some key premises and does not recognize the governing authority of the Pope.

Protestant Christianity: Protestant Christianity originated in the 16th century as an attempt to reform Roman Catholicism’s practices, dogma, and theology. It encompasses several forms or denominations which are extremely varied in structure, beliefs, relationship to state, clergy, and governance. Many protestant theologies emphasize the primary role of scripture in their faith, advocating individual interpretation of Christian texts without the mediation of a final religious authority such as the Roman Pope. The oldest Protestant Christianities include Lutheranism, Calvinism (Presbyterians), and Anglican Christianity (Episcopalians), which have established liturgies, governing structure, and formal clergy. Other variants on Protestant Christianity, including Pentecostal movements and independent churches, may lack one or more of these elements, and their leadership and beliefs are individualized and dynamic.

Source: CIA Fact Book – Religions

More Resources on Christianity

CIA Fact Book – Religions

Sacred Texts of Christianity – Christian sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Christianity at OCRT – Articles on Christianity at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

Islam – 622 CE

Islam was founded in 622 CE by Muhammad the Prophet, in Makkah (also spelled Mecca). Though it is the youngest of the world’s great religions, Muslims do not view it as a new religion. They belief that it is the same faith taught by the prophets, Abraham, David, Moses and Jesus. The role of Muhammad as the last prophet was to formalize and clarify the faith and purify it by removing ideas which were added in error. The two sacred texts of Islam are the Qur’an, which are the words of Allah ‘the One True God’ as given to Muhammad, and the Hadith, which is a collection of Muhammad’s sayings. The duties of all Muslims are known as the Five Pillars of Islam and are:

- Recite the shahadah at least once.

- Perform the salat (prayer) 5 times a day while facing the Kaaba in Makkah.

- Donate regularly to charity via the zakat, a 2.5% charity tax, and through additional donations to the needy.

- Fast during the month of Ramadan, the month that Muhammad received the Qur’an from Allah.

- Make pilgrimage to Makkah at least once in life, if economically and physically possible.

Muslims follow a strict monotheism with one creator who is just, omnipotent and merciful. They also believe in Satan who drives people to sin, and that all unbelievers and sinners will spend eternity in Hell. Muslims who sincerely repent and submit to God will return to a state of sinlessness and go to Paradise after death. Alcohol, drugs, and gambling should be avoided and they reject racism. They respect the earlier prophets, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, but regard the concept of the divinity of Jesus as blasphemous and do not believe that he was executed on the cross.

More Resources on Islam

Sacred Texts of Islam – Muslim sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Islam at OCRT – Article on Islam at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

www.jannah.org – Independent site on Islam with good information on the response of mainstream Muslims to terrorism.

The Islam Page – One of the oldest Islam pages on the web. Many articles/books and resources.

Islamic Circle of North America – Great resource with news, articles, family, youth pages, etc.

Islaam.com – Tons of informative articles and information.

Sikhism – 1500 CE

The Sikh faith was founded by Shri Guru Nanak Dev Ji in the Punjab area, now Pakistan. He began preaching the way to enlightenment and God after receiving a vision. After his death a series of nine Gurus (regarded as reincarnations of Guru Nanak) led the movement until 1708. At this time these functions passed to the Panth and the holy text. This text, the Shri Guru Granth Sahib, was compiled by the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh. It consists of hymns and writings of the first 10 Gurus, along with texts from different Muslim and Hindu saints. The holy text is considered the 11th and final Guru.

Sikhs believe in a single formless God with many names, who can be known through meditation. Sikhs pray many times each day and are prohibited from worshipping idols or icons. They believe in samsara, karma, and reincarnation as Hindus do but reject the caste system. They believe that everyone has equal status in the eyes of God. During the 18th century, there were a number of attempts to prepare an accurate portrayal of Sikh customs. Sikh scholars and theologians started in 1931 to prepare the Reht Maryada — the Sikh code of conduct and conventions. This has successfully achieved a high level of uniformity in the religious and social practices of Sikhism throughout the world. It contains 27 articles. Article 1 defines who is a Sikh:

“Any human being who faithfully believes in:

- One Immortal Being,

- Ten Gurus, from Guru Nanak Dev to Guru Gobind Singh,

- The Guru Granth Sahib,

- The utterances and teachings of the ten Gurus and

- the baptism bequeathed by the tenth Guru, and who does not owe allegiance to any other religion, is a Sikh.”

More Resources on Sikhism

Sacred Texts of Sikhism – Sikh sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Sikhism at OCRT – Article on Sikhism at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

A Sikh Youth Site – Excellent Sikh site with lots of information and resources for youths and others.

Bahá’í – 1863 CE

The Bahá’í Faith arose from Islam in the 1800s based on the teachings of Baha’u’llah and is now a distinct worldwide faith. The faith’s followers believe that God has sent nine great prophets to mankind through whom the Holy Spirit has revealed the “Word of God.” This has given rise to the major world religions. Although these religions arose from the teachings of the prophets of one God, Bahá’í’s do not believe they are all the same. The differences in the teachings of each prophet are due to the needs of the society they came to help and what mankind was ready to have revealed to it. Bahá’í beliefs promote gender and race equality, freedom of expression and assembly, world peace and world government. They believe that a single world government led by Bahá’ís will be established at some point in the future. The faith does not attempt to preserve the past but does embrace the findings of science. Bahá’ís believe that every person has an immortal soul which can not die but is freed to travel through the spirit world after death.

More Resources on Bahá’í

Sacred Texts of Bahá’í – Bahá’í sacred texts available for free online viewing at sacred-texts.com.

Bahá’í at OCRT – Article on Bahá’í at the web site of the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance.

www.bahaifaith.com – Gateway to the official sites of the Bahá’í Faith.

* The dates are given in BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era). These years correspond to the same dates in BC and AD but by defining the current period as the “Common Era” the nomenclature attempts to treat all religions and beliefs as equal.

Much of the material on this page was adapted from the descriptions of the different world religions at the web site of the Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. Please visit their site if you would like more information on these faiths. They also have many links to resources on the net for each faith.

Source of the above chapter:

http://www.omsakthi.org/religions.html

Religion Statistics and General Info

GeoHive – Country by country listing detailing the religious makeup of each.

Adherents.com – Major religions of the world ranked by the number of adherents.

Interfaith Calendar – Calendar of important days in the world’s major religions.

Links

- CIA Fact Book – Religions >>

- http://www.religioustolerance.org/

- http://www.omsakthi.org/religions.html

Books

The World’s Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions

Huston Smith

The World’s Religions, by Huston Smith, has been a standard introduction to its eponymous subject since its first publication in 1958. Smith writes humbly, forswearing judgment on the validity of world religions. His introduction asks, “How does it all sound from above? Like bedlam, or do the strains blend in strange, ethereal harmony? … We cannot know. All we can do is try to listen carefully and with full attention to each voice in turn as it addresses the divine. Such listening defines the purpose of this book.” His criteria for inclusion and analysis of religions in this book are “relevance to the modern mind” and “universality,” and his interest in each religion is more concerned with its principles than its context. Therefore, he avoids cataloging the horrors and crimes of which religions have been accused, and he attempts to show each “at their best.” Yet The World’s Religions is no pollyannaish romp: “It is about religion alive,” Huston writes. “It calls the soul to the highest adventure it can undertake, a proposed journey across the jungles, peaks, and deserts of the human spirit. The call is to confront reality.” And by translating the voices of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Confucianism, Christianity, and Judaism, among others, Smith has amplified the divine call for generations of readers. –Michael Joseph Gross

PS1 World Religions – Humor

PS2 Religion and Violence

Charles Selengut characterizes the phrase “religion and violence” as “jarring”, asserting that “religion is thought to be opposed to violence and a force for peace and reconciliation”. He acknowledges, however, that “the history and scriptures of the world’s religions tell stories of violence and war as they speak of peace and love.”

Hector Avalos argues that, because religions claim divine favor for themselves, over and against other groups, this sense of righteousness leads to violence because conflicting claims to superiority, based on unverifiable appeals to God, cannot be adjudicated objectively.

Critics of religion Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins go further and argue that religions do tremendous harm to society by using violence to promote their goals, in ways that are endorsed and exploited by their leaders.

Regina Schwartz argues that all monotheistic religions are inherently violent because of an exclusivism that inevitably fosters violence against those that are considered outsiders.

Lawrence Wechsler asserts that Schwartz isn’t just arguing that Abrahamic religions have a violent legacy, but that the legacy is actually genocidal in nature.

Byron Bland asserts that one of the most prominent reasons for the “rise of the secular in Western thought” was the reaction against the religious violence of the 16th and 17th centuries. He asserts that

“(t)he secular was a way of living with the religious differences that had produced so much horror. Under secularity, political entities have a warrant to make decisions independent from the need to enforce particular versions of religious orthodoxy. Indeed, they may run counter to certain strongly held beliefs if made in the interest of common welfare. Thus, one of the important goals of the secular is to limit violence.”

Nonetheless, believers have used similar arguments when responding to atheists in these discussions, pointing to the widespread imprisonment and mass murder of individuals under atheist states in the twentieth century:

And who can deny that Stalin and Mao, not to mention Pol Pot and a host of others, all committed atrocities in the name of a Communist ideology that was explicitly atheistic? Who can dispute that they did their bloody deeds by claiming to be establishing a ‘new man’ and a religion-free utopia? These were mass murders performed with atheism as a central part of their ideological inspiration, they were not mass murders done by people who simply happened to be atheist. —Dinesh D’Souza

In response to such a line of argument, however, author Sam Harris writes:

The problem with fascism and communism, however, is not that they are too critical of religion; the problem is that they are too much like religions. Such regimes are dogmatic to the core and generally give rise to personality cults that are indistinguishable from cults of religious hero worship. Auschwitz, the gulag and the killing fields were not examples of what happens when human beings reject religious dogma; they are examples of political, racial and nationalistic dogma run amok. There is no society in human history that ever suffered because its people became too reasonable. —Sam Harris

Related Resources

Bible Quotes

Dr Ian Guthridge cited many instances of genocide in the Old Testament:

“the Bible also contains the horrific account of what can only be described as a “biblical holocaust”. For, in order to keep the chosen people apart from and unaffected by the alien beliefs and practices of indigenous or neighbouring peoples, when God commanded his chosen people to conquer the Promised Land, he placed city after city ‘under the ban” -which meant that every man, woman and child was to be slaughtered at the point of the sword.”

Forget for a moment that the following are the Bible quotations…

What would you think about the “Lord” if this were a movie script?

Is the “Lord”a peaceful, gentle, merciful and compassionate god?

– – –

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Get up early in the morning and stand before Pharaoh. Tell him, ‘This is what the Lord, the God of the Hebrews, says: Let my people go, so they can worship me. If you don’t, I will send more plagues on you and your officials and your people. Then you will know that there is no one like me in all the earth. By now I could have lifted my hand and struck you and your people with a plague to wipe you off the face of the earth. But I have spared you for a purpose—to show you my power and to spread my fame throughout the earth. — Exodus 9: 13-16

– – –

The gates of the city of Jericho were closed. The people in the city were afraid because the Israelites were near. No one went into the city, and no one came out. Then the LORD said to Joshua, “Look, I will let you defeat the city of Jericho. You will defeat the king and all the fighting men in the city. March around the city with your army once every day for six days.Tell seven of the priests to carry trumpets made from the horns of male sheep and to march in front of the priests who are carrying the Holy Box. On the seventh day march around the city seven times and tell the priests to blow the trumpets while they march. They will make one loud noise from the trumpets. When you hear that noise, tell all the people to begin shouting. When you do this, the walls of the city will fall down and your people will be able to go straight into the city.” – Joshua 6: 6-5

– – –

So then the priests blew the trumpets. When the people heard the trumpets, they began shouting. The walls fell down, and the people ran up into the city. So the Israelites defeated that city. The people destroyed everything in the city. They destroyed everything that was living there. They killed the young and old men, the young and old women, and the cattle, sheep, and donkeys. Joshua talked to the two spies. He said, “You made a promise to the prostitute. So go to her house and bring her out and all those who are with her.” So the two men went into the house and brought out Rahab, her father, mother, brothers, all her family, and all those who were with her. They put all the people in a safe place outside the camp of Israel.

Then the Israelites burned the whole city and everything in it except for the things made from silver, gold, bronze, and iron. They put these things in the LORD’S treasury. Joshua saved Rahab the prostitute, her family, and all those who were with her. Joshua let them live because Rahab helped the spies Joshua had sent out to Jericho. Rahab still lives among the Israelites today. — Joshua 6: 20-25

– – –

Then the LORD said to Joshua, “Don’t be afraid of that army, because I will allow you to defeat them. By this time tomorrow, you will have killed them all. You will cut the legs of the horses and burn all their chariots.”

So Joshua and his whole army surprised the enemy and attacked them at the river of Merom. The LORD allowed Israel to defeat them. The army of Israel defeated them and chased them to Greater Sidon, Misrephoth Maim, and the Valley of Mizpah in the east. The army of Israel fought until none of the enemy was left alive. Joshua did what the LORD said to do; he cut the legs of their horses and burned their chariots.

Then Joshua went back and captured the city of Hazor and killed its king. (Hazor was the leader of all the kingdoms that fought against Israel.) The army of Israel killed everyone in that city and completely destroyed all the people. There was nothing left alive. Then they burned the city.

Joshua captured all these cities and killed all their kings. He completely destroyed everything in these cities—just as Moses, the LORD’S servant, had commanded. But the army of Israel did not burn any cities that were built on hills. The only city built on a hill that they burned was Hazor. This is the city Joshua burned. The Israelites kept for themselves all the things and all the animals they found in the cities. But they killed all the people there. They left no one alive. Long ago the LORD commanded his servant Moses to do this. Then Moses commanded Joshua to do this. So Joshua obeyed God. He did everything that the LORD had commanded Moses. – Joshua 11: 6-15

– – –

When thou comest nigh unto a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace unto it.

And it shall be, if it make thee answer of peace, and open unto thee, then it shall be, that all the people that is found therein shall be tributaries unto thee, and they shall serve thee.

And if it will make no peace with thee, but will make war against thee, then thou shalt besiege it:

And when the LORD thy God hath delivered it into thine hands, thou shalt smite every male thereof with the edge of the sword:

But the women, and the little ones, and the cattle, and all that is in the city, even all the spoil thereof, shalt thou take unto thyself; and thou shalt eat the spoil of thine enemies, which the LORD thy God hath given thee.

Thus shalt thou do unto all the cities which are very far off from thee, which are not of the cities of these nations.

But of the cities of these people, which the LORD thy God doth give thee for an inheritance, thou shalt save alive nothing that breatheth:

But thou shalt utterly destroy them; namely, the Hittites, and the Amorites, the Canaanites, and the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites; as the LORD thy God hath commanded thee:

That they teach you not to do after all their abominations, which they have done unto their gods; so should ye sin against the LORD your God. — Deuteronomy Chapter 20:10-18

—

In the name of God

The Crusades

The Crusades – What were the Crusades?

The Crusades were a series of Holy Wars launched by the Christian states of Europe against the Saracens. The term ‘Saracen’ was the word used to describe a Moslem during the time of the Crusades. The Crusades started in 1095 when Pope Claremont preached the First Crusade at the Council of Claremont. The Pope’s preaching led to thousands immediately affixing the cross to their garments – the name Crusade given to the Holy Wars came from old French word ‘crois’ meaning ‘cross’. The Crusades were great military expeditions undertaken by the Christian nations of Europe for the purpose of rescuing the holy places of Palestine from the hands of the Mohammedans. They were eight in number, the first four being sometimes called the Principal Crusades, and the remaining four the Minor Crusades. In addition there was a Children’s Crusade. There were several other expeditions which were insignificant in numbers or results.

What was the Cause for the Crusades?

The reason for the crusades was a war between Christians and Moslems which centered around the city of Jerusalem. The City of Jerusalem held a Holy significance to the Christian religion. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem commemorated the hill of crucifixion and the tomb of Christ’s burial and was visited by Pilgrims. In 1065 Jerusalem was taken by the Turks and 3000 Christians were massacred starting a chain of events which contributed to the cause of the crusades.

What were the Objectives of the Crusades?

The Objectives of the crusades was at first to release the Holy Land, in particular Jerusalem, from the Saracens, but in time was extended to seizing Spain from the Moors, the Slavs and Pagans from eastern Europe, and the islands of the Mediterranean.

How many Crusades were there?

There were a total of nine crusades! The first four crusades were seen as the most import and scant reference is made to the other crusades – with the exception of the Children’s crusade which effectively led to the decline of the crusades. For a period of two hundred years Europe and Asia were engaged in almost constant warfare. Throughout this period there was a continuous movement of crusaders to and from the Moslem possessions in Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt.

The First Crusade

The first crusade, which lasted from 1095-1099, established the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, providing more lands for the crusading knights, who often travelled across Europe to try their fortunes and to visit the Holy Sepulchre.

Read more at the source of this section (about Crusades) >>

– – –

The Inquisition

The Inquisition (Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis; Inquiry on Heretical Perversity) was a group of decentralized institutions within the judicial system of the Roman Catholic Church whose aim was to “fight against heretics”. It started in 12th-century France to combat the spread of heresy and error, and was later expanded to other European countries.

I see the great Apostasy, I see the desolation of Christendom, I see the smoking ruins, I see the reign of monsters; I see those vice-gods, that Gregory VII, that Innocent III, that Boniface Vlll, that Alexander Vl, that Gregory XIII, that Pius IX; I see their long succession, I hear their insufferable blasphemies, I see their abominable lives; I see them worshipped by blinded generations, bestowing hollow benedictions, bartering away worthless promises of heaven; I see their liveried slaves, their shaven priests, their celibate confessors; I see the infamous confessional, the ruined women, the murdered innocents; I hear the lying absolutions, the dying groans; I hear the cries of the victims; I hear the anathemas, the curses, the thunders of the interdicts; I see the racks, the dungeons, the stakes; I see that inhuman Inquisition, those fires of Smithfield, those butcheries of St. Bartholomew, that Spanish Armada, those unspeakable dragonnades, that endless train of wars, that dreadful multitude of massacres. I see it all, and in the name of the ruin it has brought in the Church and in the world, in the name of the truth it has denied, the temple it has defiled, the God it has blasphemed, the souls it has destroyed; in the name of the millions it has deluded, the millions it has slaughtered, the millions it has damned; with holy confessors, with noble reformers, with innumerable martyrs, with the saints of ages, I denounce it as the masterpiece of Satan, as the body and soul and essence of antichrist.”

Source: THE INQUISITION: A Study in Absolute Catholic Power

– – –

Spanish colonization of the Americas

Colonial expansion under the crown of Castile was initiated by the Spanish conquistadores and developed by the Monarchy of Spain through its administrators and missionaries. The motivations for colonial expansion were trade and the spread of the Christian faith through indigenous conversions. It lasted for over four hundred years, from 1492 to 1898.

– – –

“Gott mit uns” (meaning God with us) is a phrase commonly used on armor in the German military from the German Empire to the end of the Third Reich, although its historical origins are far older. The Russian Empire’s motto also translates to this.

ORIGINAL NAZI WH WEHRMACHT BELT BUCKLE “GOTT MIT UNS”

– – –

WAR and Peace

Peace is often defined as “absence of war”.

Peace is a state of harmony characterized by the lack of violent, conflict behaviours and the freedom from fear of violence. Commonly understood as the absence of hostility, peace also suggests the existence of healthy or newly healed interpersonal or international relationships, prosperity in matters of social or economic welfare, the establishment of equality, and a working political order that serves the true interests of all. In international relations, peacetime is not only the absence of war or violent conflict, but also the presence of positive and respectful cultural and economic relationships.

Is war reflection of human nature or is it the result of skilful propaganda and manipulation of a society to impose will of ruling elite and to enslave the “enemy”?

Existence of human societies in which warfare does not exist, suggests that humans may not be naturally disposed for warfare and wars emerge only under particular circumstances.

“War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.” — Carl von Clausewitz, Prussian military general and theoretician (1832 treatise On War)

War is an organized and often prolonged conflict that is carried out by states and/or non-state actors. It is characterized by extreme violence, social disruption, human suffering, and economic destruction.

War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political communities, and therefore is defined as a form of political violence or intervention. The set of techniques used by a group to carry out war is known as warfare.

The new military technologies bring the potential risk of the complete extinction of the human species.

List of ongoing wars

More Links

- https://blog.world-mysteries.com/science/transformation-of-the-human-race/

- https://blog.world-mysteries.com/science/war-and-peace/

- https://blog.world-mysteries.com/science/mind-control/

Post Views: 646

Religious symbols: Christianity, Islam, Isese, Hinduism, Judaism, Baha’i, Eckankar, Buddhism, Jainism, Wicca, Unitarian Universalism, Sikhism, Taoism, Thelema, Tenrikyo, Shinto

Religion is a range of social-cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural, transcendental, and spiritual elements[1]—although there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.[2][3] Different religions may or may not contain various elements ranging from the divine,[4] sacredness,[5] faith,[6] and a supernatural being or beings.[7]

Religious practices may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration (of deities or saints), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, matrimonial and funerary services, meditation, prayer, music, art, dance or public service. Religions have sacred histories and narratives, which may be preserved in sacred texts, symbols and holy places, that primarily aim to give life meaning. Religions may contain symbolic tales that may attempt to explain the origin of life, the universe, and other phenomena; some followers believe these to be true stories. Traditionally, both faith and reason have been considered sources of religious beliefs.[8]

There are an estimated 10,000 distinct religions worldwide,[9] though nearly all of them have regionally based, relatively small followings. Four religions—Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism—account for over 77% of the world’s population, and 92% of the world either follows one of those four religions or identifies as nonreligious,[10] meaning that the remaining 9,000+ faiths account for only 8% of the population combined. The religiously unaffiliated demographic includes those who do not identify with any particular religion, atheists, and agnostics, although many in the demographic still have various religious beliefs.[11] A portion of the population, mostly located in Africa and Asia, are members of new religious movements.[12] Scholars have indicated that global religiosity may be increasing due to religious countries having generally higher birth rates.[13]

The study of religion comprises a wide variety of academic disciplines, including theology, philosophy of religion, comparative religion, and social scientific studies. Theories of religion offer various explanations for its origins and workings, including the ontological foundations of religious being and belief.[14]

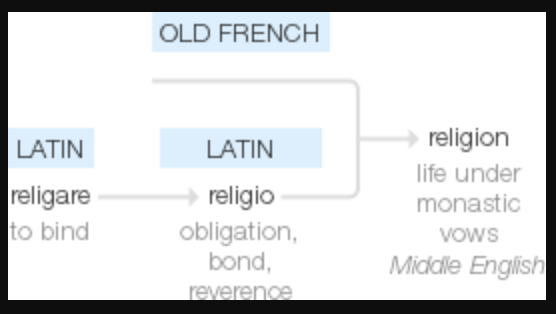

Concept and etymology

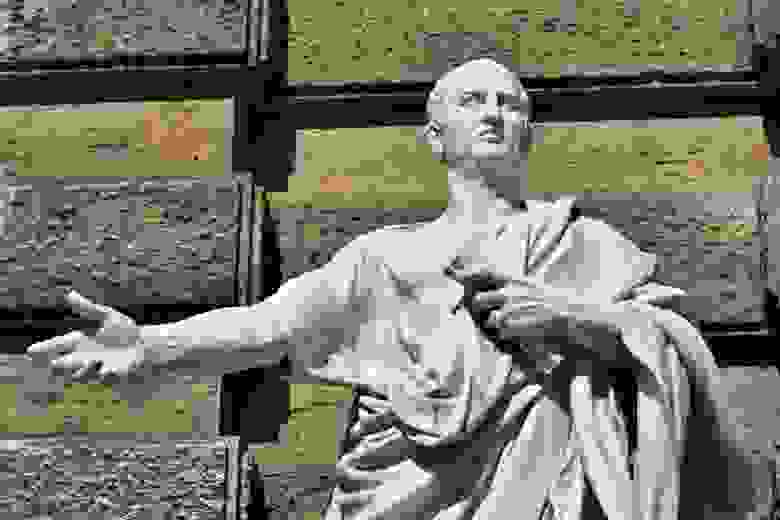

The term religion comes from both Old French and Anglo-Norman (1200s AD) and means respect for sense of right, moral obligation, sanctity, what is sacred, reverence for the gods.[15][16] It is ultimately derived from the Latin word religiō. According to Roman philosopher Cicero, religiō comes from relegere: re (meaning «again») + lego (meaning «read»), where lego is in the sense of «go over», «choose», or «consider carefully». Contrarily, some modern scholars such as Tom Harpur and Joseph Campbell have argued that religiō is derived from religare: re (meaning «again») + ligare («bind» or «connect»), which was made prominent by St. Augustine following the interpretation given by Lactantius in Divinae institutiones, IV, 28.[17][18] The medieval usage alternates with order in designating bonded communities like those of monastic orders: «we hear of the ‘religion’ of the Golden Fleece, of a knight ‘of the religion of Avys'».[19]

Religiō

In classic antiquity, religiō broadly meant conscientiousness, sense of right, moral obligation, or duty to anything.[20] In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root religiō was understood as an individual virtue of worship in mundane contexts; never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.[21][22] In general, religiō referred to broad social obligations towards anything including family, neighbors, rulers, and even towards God.[23] Religiō was most often used by the ancient Romans not in the context of a relation towards gods, but as a range of general emotions which arose from heightened attention in any mundane context such as hesitation, caution, anxiety, or fear, as well as feelings of being bound, restricted, or inhibited.[24] The term was also closely related to other terms like scrupulus (which meant «very precisely»), and some Roman authors related the term superstitio (which meant too much fear or anxiety or shame) to religiō at times.[24] When religiō came into English around the 1200s as religion, it took the meaning of «life bound by monastic vows» or monastic orders.[19][23] The compartmentalized concept of religion, where religious and worldly things were separated, was not used before the 1500s.[23] The concept of religion was first used in the 1500s to distinguish the domain of the church and the domain of civil authorities; the Peace of Augsburg marks such instance,[23] which has been described by Christian Reus-Smit as «the first step on the road toward a European system of sovereign states.»[25]

Roman general Julius Caesar used religiō to mean «obligation of an oath» when discussing captured soldiers making an oath to their captors.[26] Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder used the term religiō to describe the apparent respect given by elephants to the night sky.[27] Cicero used religiō as being related to cultum deorum (worship of the gods).[28]

Threskeia

In Ancient Greece, the Greek term threskeia (θρησκεία) was loosely translated into Latin as religiō in late antiquity. Threskeia was sparsely used in classical Greece but became more frequently used in the writings of Josephus in the 1st century AD. It was used in mundane contexts and could mean multiple things from respectful fear to excessive or harmfully distracting practices of others, to cultic practices. It was often contrasted with the Greek word deisidaimonia, which meant too much fear.[29]

Religion and religions

The modern concept of religion, as an abstraction that entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines, is a recent invention in the English language. Such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to events such as the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and globalization in the Age of Exploration, which involved contact with numerous foreign cultures with non-European languages.[21][22][30] Some argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply the term religion to non-Western cultures,[31][32] while some followers of various faiths rebuke using the word to describe their own belief system.[33]

The concept of religion was formed in the 16th and 17th centuries,[34][35] despite the fact that ancient sacred texts like the Bible, the Quran, and others did not have a word or even a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[36][37] For example, there is no precise equivalent of religion in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[38] One of its central concepts is halakha, meaning the walk or path sometimes translated as law, which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.[39] Even though the beliefs and traditions of Judaism are found in the ancient world, ancient Jews saw Jewish identity as being about an ethnic or national identity and did not entail a compulsory belief system or regulated rituals.[40] In the 1st century AD, Josephus had used the Greek term ioudaismos (Judaism) as an ethnic term and was not linked to modern abstract concepts of religion or a set of beliefs.[3] The very concept of «Judaism» was invented by the Christian Church,[41] and it was in the 19th century that Jews began to see their ancestral culture as a religion analogous to Christianity.[40] The Greek word threskeia, which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus, is found in the New Testament. Threskeia is sometimes translated as «religion» in today’s translations, but the term was understood as generic «worship» well into the medieval period.[3] In the Quran, the Arabic word din is often translated as religion in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed din as «law».[3]

The Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as religion,[42] also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between imperial law and universal or Buddha law, but these later became independent sources of power.[43][44]

Though traditions, sacred texts, and practices have existed throughout time, most cultures did not align with Western conceptions of religion since they did not separate everyday life from the sacred. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the terms Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism, and world religions first entered the English language.[45][46][47] Native Americans were also thought of as not having religions and also had no word for religion in their languages either.[46][48] No one self-identified as a Hindu or Buddhist or other similar terms before the 1800s.[49] «Hindu» has historically been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for people indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.[50][51] Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of religion since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this idea.[52][53]

According to the philologist Max Müller in the 19th century, the root of the English word religion, the Latin religiō, was originally used to mean only reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety (which Cicero further derived to mean diligence).[54][55] Müller characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called law.[56]

Definition

Religious symbols from left to right, top to bottom: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, the Baháʼí Faith, Eckankar, Sikhism, Jainism, Wicca, Unitarian Universalism, Shinto, Taoism, Thelema, Tenrikyo, and Zoroastrianism

Scholars have failed to agree on a definition of religion. There are, however, two general definition systems: the sociological/functional and the phenomenological/philosophical.[57][58][59][60][61]

Modern Western

The concept of religion originated in the modern era in the West.[32] Parallel concepts are not found in many current and past cultures; there is no equivalent term for religion in many languages.[3][23] Scholars have found it difficult to develop a consistent definition, with some giving up on the possibility of a definition.[62][63] Others argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply it to non-Western cultures.[31][32]

An increasing number of scholars have expressed reservations about ever defining the essence of religion.[64] They observe that the way the concept today is used is a particularly modern construct that would not have been understood through much of history and in many cultures outside the West (or even in the West until after the Peace of Westphalia).[65] The MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions states:

The very attempt to define religion, to find some distinctive or possibly unique essence or set of qualities that distinguish the religious from the remainder of human life, is primarily a Western concern. The attempt is a natural consequence of the Western speculative, intellectualistic, and scientific disposition. It is also the product of the dominant Western religious mode, what is called the Judeo-Christian climate or, more accurately, the theistic inheritance from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The theistic form of belief in this tradition, even when downgraded culturally, is formative of the dichotomous Western view of religion. That is, the basic structure of theism is essentially a distinction between a transcendent deity and all else, between the creator and his creation, between God and man.[66]

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz defined religion as a

… system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.»[67]

Alluding perhaps to Tylor’s «deeper motive», Geertz remarked that

… we have very little idea of how, in empirical terms, this particular miracle is accomplished. We just know that it is done, annually, weekly, daily, for some people almost hourly; and we have an enormous ethnographic literature to demonstrate it.[68]

The theologian Antoine Vergote took the term supernatural simply to mean whatever transcends the powers of nature or human agency. He also emphasized the cultural reality of religion, which he defined as

… the entirety of the linguistic expressions, emotions and, actions and signs that refer to a supernatural being or supernatural beings.[7]

Peter Mandaville and Paul James intended to get away from the modernist dualisms or dichotomous understandings of immanence/transcendence, spirituality/materialism, and sacredness/secularity. They define religion as

… a relatively-bounded system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and in which communion with others and Otherness is lived as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.[69]

According to the MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions, there is an experiential aspect to religion which can be found in almost every culture:

… almost every known culture [has] a depth dimension in cultural experiences … toward some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life. When more or less distinct patterns of behavior are built around this depth dimension in a culture, this structure constitutes religion in its historically recognizable form. Religion is the organization of life around the depth dimensions of experience—varied in form, completeness, and clarity in accordance with the environing culture.[70]

Classical

Budazhap Shiretorov (Будажап Цыреторов), the head shaman of the religious community Altan Serge (Алтан Сэргэ) in Buryatia

Friedrich Schleiermacher in the late 18th century defined religion as das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl, commonly translated as «the feeling of absolute dependence».[71]

His contemporary Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel disagreed thoroughly, defining religion as «the Divine Spirit becoming conscious of Himself through the finite spirit.»[72]

Edward Burnett Tylor defined religion in 1871 as «the belief in spiritual beings».[73] He argued that narrowing the definition to mean the belief in a supreme deity or judgment after death or idolatry and so on, would exclude many peoples from the category of religious, and thus «has the fault of identifying religion rather with particular developments than with the deeper motive which underlies them». He also argued that the belief in spiritual beings exists in all known societies.

In his book The Varieties of Religious Experience, the psychologist William James defined religion as «the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine».[4] By the term divine James meant «any object that is godlike, whether it be a concrete deity or not»[74] to which the individual feels impelled to respond with solemnity and gravity.[75]

Sociologist Émile Durkheim, in his seminal book The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, defined religion as a «unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things».[5] By sacred things he meant things «set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them». Sacred things are not, however, limited to gods or spirits.[note 1] On the contrary, a sacred thing can be «a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred».[76] Religious beliefs, myths, dogmas and legends are the representations that express the nature of these sacred things, and the virtues and powers which are attributed to them.[77]

Echoes of James’ and Durkheim’s definitions are to be found in the writings of, for example, Frederick Ferré who defined religion as «one’s way of valuing most comprehensively and intensively».[78] Similarly, for the theologian Paul Tillich, faith is «the state of being ultimately concerned»,[6] which «is itself religion. Religion is the substance, the ground, and the depth of man’s spiritual life.»[79]

When religion is seen in terms of sacred, divine, intensive valuing, or ultimate concern, then it is possible to understand why scientific findings and philosophical criticisms (e.g., those made by Richard Dawkins) do not necessarily disturb its adherents.[80]

Aspects

Beliefs

Traditionally, faith, in addition to reason, has been considered a source of religious beliefs. The interplay between faith and reason, and their use as perceived support for religious beliefs, have been a subject of interest to philosophers and theologians.[8] The origin of religious belief as such is an open question, with possible explanations including awareness of individual death, a sense of community, and dreams.[81]

Mythology

The word myth has several meanings.

- A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

- A person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence; or

- A metaphor for the spiritual potentiality in the human being.[82]

Ancient polytheistic religions, such as those of Greece, Rome, and Scandinavia, are usually categorized under the heading of mythology. Religions of pre-industrial peoples, or cultures in development, are similarly called myths in the anthropology of religion. The term myth can be used pejoratively by both religious and non-religious people. By defining another person’s religious stories and beliefs as mythology, one implies that they are less real or true than one’s own religious stories and beliefs. Joseph Campbell remarked, «Mythology is often thought of as other people’s religions, and religion can be defined as misinterpreted mythology.»[83]

In sociology, however, the term myth has a non-pejorative meaning. There, myth is defined as a story that is important for the group, whether or not it is objectively or provably true.[84] Examples include the resurrection of their real-life founder Jesus, which, to Christians, explains the means by which they are freed from sin, is symbolic of the power of life over death, and is also said to be a historical event. But from a mythological outlook, whether or not the event actually occurred is unimportant. Instead, the symbolism of the death of an old life and the start of a new life is most significant. Religious believers may or may not accept such symbolic interpretations.

Practices

The practices of a religion may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration of a deity (god or goddess), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, prayer, religious music, religious art, sacred dance, public service, or other aspects of human culture.[85]

Religions have a societal basis, either as a living tradition which is carried by lay participants, or with an organized clergy, and a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership.

Academic study

A number of disciplines study the phenomenon of religion: theology, comparative religion, history of religion, evolutionary origin of religions, anthropology of religion, psychology of religion (including neuroscience of religion and evolutionary psychology of religion), law and religion, and sociology of religion.

Daniel L. Pals mentions eight classical theories of religion, focusing on various aspects of religion: animism and magic, by E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer; the psycho-analytic approach of Sigmund Freud; and further Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Mircea Eliade, E.E. Evans-Pritchard, and Clifford Geertz.[86]

Michael Stausberg gives an overview of contemporary theories of religion, including cognitive and biological approaches.[87]

Theories

Sociological and anthropological theories of religion generally attempt to explain the origin and function of religion.[88] These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of religious belief and practice.

Origins and development

The origin of religion is uncertain. There are a number of theories regarding the subsequent origins of religious practices.

According to anthropologists John Monaghan and Peter Just, «Many of the great world religions appear to have begun as revitalization movements of some sort, as the vision of a charismatic prophet fires the imaginations of people seeking a more comprehensive answer to their problems than they feel is provided by everyday beliefs. Charismatic individuals have emerged at many times and places in the world. It seems that the key to long-term success—and many movements come and go with little long-term effect—has relatively little to do with the prophets, who appear with surprising regularity, but more to do with the development of a group of supporters who are able to institutionalize the movement.»[89]

The development of religion has taken different forms in different cultures. Some religions place an emphasis on belief, while others emphasize practice. Some religions focus on the subjective experience of the religious individual, while others consider the activities of the religious community to be most important. Some religions claim to be universal, believing their laws and cosmology to be binding for everyone, while others are intended to be practiced only by a closely defined or localized group. In many places, religion has been associated with public institutions such as education, hospitals, the family, government, and political hierarchies.[90]

Anthropologists John Monoghan and Peter Just state that, «it seems apparent that one thing religion or belief helps us do is deal with problems of human life that are significant, persistent, and intolerable. One important way in which religious beliefs accomplish this is by providing a set of ideas about how and why the world is put together that allows people to accommodate anxieties and deal with misfortune.»[90]

Cultural system

While religion is difficult to define, one standard model of religion, used in religious studies courses, was proposed by Clifford Geertz, who simply called it a «cultural system».[91] A critique of Geertz’s model by Talal Asad categorized religion as «an anthropological category».[92] Richard Niebuhr’s (1894–1962) five-fold classification of the relationship between Christ and culture, however, indicates that religion and culture can be seen as two separate systems, though with some interplay.[93]

One modern academic theory of religion, social constructionism, says that religion is a modern concept that suggests all spiritual practice and worship follows a model similar to the Abrahamic religions as an orientation system that helps to interpret reality and define human beings.[94] Among the main proponents of this theory of religion are Daniel Dubuisson, Timothy Fitzgerald, Talal Asad, and Jason Ānanda Josephson. The social constructionists argue that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

Cognitive science

Cognitive science of religion is the study of religious thought and behavior from the perspective of the cognitive and evolutionary sciences.[95] The field employs methods and theories from a very broad range of disciplines, including: cognitive psychology, evolutionary psychology, cognitive anthropology, artificial intelligence, cognitive neuroscience, neurobiology, zoology, and ethology. Scholars in this field seek to explain how human minds acquire, generate, and transmit religious thoughts, practices, and schemas by means of ordinary cognitive capacities.

Hallucinations and delusions related to religious content occurs in about 60% of people with schizophrenia. While this number varies across cultures, this had led to theories about a number of influential religious phenomena and possible relation to psychotic disorders. A number of prophetic experiences are consistent with psychotic symptoms, although retrospective diagnoses are practically impossible.[96][97][98] Schizophrenic episodes are also experienced by people who do not have belief in gods.[99]

Religious content is also common in temporal lobe epilepsy, and obsessive–compulsive disorder.[100][101] Atheistic content is also found to be common with temporal lobe epilepsy.[102]

Comparativism

Comparative religion is the branch of the study of religions concerned with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices of the world’s religions. In general, the comparative study of religion yields a deeper understanding of the fundamental philosophical concerns of religion such as ethics, metaphysics, and the nature and form of salvation. Studying such material is meant to give one a richer and more sophisticated understanding of human beliefs and practices regarding the sacred, numinous, spiritual and divine.[103]

In the field of comparative religion, a common geographical classification[104] of the main world religions includes Middle Eastern religions (including Zoroastrianism and Iranian religions), Indian religions, East Asian religions, African religions, American religions, Oceanic religions, and classical Hellenistic religions.[104]

Classification

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the academic practice of comparative religion divided religious belief into philosophically defined categories called world religions. Some academics studying the subject have divided religions into three broad categories:

- world religions, a term which refers to transcultural, international religions;

- indigenous religions, which refers to smaller, culture-specific or nation-specific religious groups; and

- new religious movements, which refers to recently developed religions.[105]

Some recent scholarship has argued that not all types of religion are necessarily separated by mutually exclusive philosophies, and furthermore that the utility of ascribing a practice to a certain philosophy, or even calling a given practice religious, rather than cultural, political, or social in nature, is limited.[106][107][108] The current state of psychological study about the nature of religiousness suggests that it is better to refer to religion as a largely invariant phenomenon that should be distinguished from cultural norms (i.e. religions).[109][clarification needed]

Morphological classification

Some scholars classify religions as either universal religions that seek worldwide acceptance and actively look for new converts, such as Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Jainism, while ethnic religions are identified with a particular ethnic group and do not seek converts.[110][111] Others reject the distinction, pointing out that all religious practices, whatever their philosophical origin, are ethnic because they come from a particular culture.[112][113][114]

Demographic classification

The five largest religious groups by world population, estimated to account for 5.8 billion people and 84% of the population, are Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism (with the relative numbers for Buddhism and Hinduism dependent on the extent of syncretism) and traditional folk religion.

| Five largest religions | 2015 (billion)[115] | 2015 (%) | Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2.3 | 31.2% | Christianity by country |

| Islam | 1.8 | 24.1% | Islam by country |

| Hinduism | 1.1 | 15.1% | Hinduism by country |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | 6.9% | Buddhism by country |

| Folk Religion | 0.4 | 5.7% | |

| Total | 6.1 | 83% | Religions by country |

A global poll in 2012 surveyed 57 countries and reported that 59% of the world’s population identified as religious, 23% as not religious, 13% as convinced atheists, and also a 9% decrease in identification as religious when compared to the 2005 average from 39 countries.[116] A follow-up poll in 2015 found that 63% of the globe identified as religious, 22% as not religious, and 11% as convinced atheists.[117] On average, women are more religious than men.[118] Some people follow multiple religions or multiple religious principles at the same time, regardless of whether or not the religious principles they follow traditionally allow for syncretism.[119][120][121] A 2017 Pew projection suggests that Islam will overtake Christianity as the plurality religion by 2075. Unaffiliated populations are projected to drop, even when taking disaffiliation rates into account, due to differences in birth rates.[122][123]

Scholars have indicated that global religiosity may be increasing due to religious countries having higher birth rates in general.[124]

Specific religions

Abrahamic

Abrahamic religions are monotheistic religions which believe they descend from Abraham.

Judaism

The Torah is the primary sacred text of Judaism.