Last updated on

Feb 10, 2022

Need to match strings which don’t start with a given pattern using a regular expression in Python?

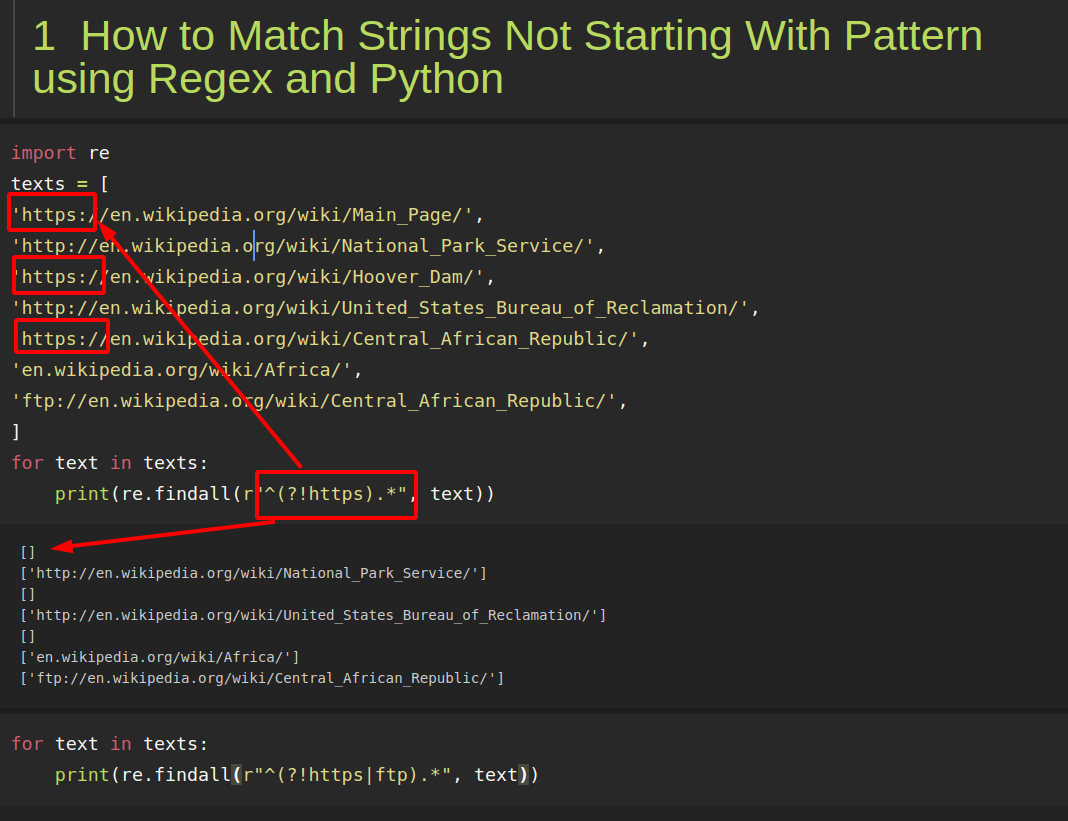

If so, you may use the following syntax to find all strings except ones which don’t start with https:

r"^(?!https).*"

Step 1: Match strings not starting with pattern

IN this example we have a list of URLs. Let’s say that you would like to get all of them which don’t start with https.

For this purpose we will use negative lookahead:

import re

texts = [

'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page/',

'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Park_Service/',

'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoover_Dam/',

'http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bureau_of_Reclamation/',

'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_African_Republic/',

'en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa/',

'ftp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_African_Republic/',

]

for text in texts:

print(re.findall(r"^(?!https).*", text))

The result is:

[]

['http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Park_Service/']

[]

['http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bureau_of_Reclamation/']

[]

['en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa/']

['ftp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_African_Republic/']

How does it work?

^— asserts position at start of the string(?!https)— Negative Lookahead — assert that the regex does not match — https.*— matches any character between zero and unlimited times

Step 2: Match strings not starting with several patterns

Now let try to find all strings which don’t start with:

- https

- ftp

We can use | which is or in regex syntax — r"^(?!https|ftp).*":

for text in texts:

print(re.findall(r"^(?!https|ftp).*", text))

result is:

[]

[‘http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Park_Service/’]

[]

[‘http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bureau_of_Reclamation/’]

[]

[‘en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa/’]

[]

Note: you can add many patterns with |.

Step 3: Match strings not starting with list of characters

Finally let’s see how to match all strings that don’t start with several characters like:

fh

This time we are going to list all characters between square brackets: [^hf]. Statement [hf] means match letters — f or h while ^ negates the match.

In other words match a single character not present in the list — [hf].

So we can use:

for text in texts:

print(re.findall(r"^[^hf].*", text))

Which will give us:

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

['en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa/']

[]

| Character classes | |

|---|---|

| . | any character except newline |

| w d s | word, digit, whitespace |

| W D S | not word, digit, whitespace |

| [abc] | any of a, b, or c |

| [^abc] | not a, b, or c |

| [a-g] | character between a & g |

| Anchors | |

| ^abc$ | start / end of the string |

| b | word boundary |

| Escaped characters | |

| . * \ | escaped special characters |

| t n r | tab, linefeed, carriage return |

| u00A9 | unicode escaped © |

| Groups & Lookaround | |

| (abc) | capture group |

| 1 | backreference to group #1 |

| (?:abc) | non-capturing group |

| (?=abc) | positive lookahead |

| (?!abc) | negative lookahead |

| Quantifiers & Alternation | |

| a* a+ a? | 0 or more, 1 or more, 0 or 1 |

| a{5} a{2,} | exactly five, two or more |

| a{1,3} | between one & three |

| a+? a{2,}? | match as few as possible |

| ab|cd | match ab or cd |

Dec 29, 2021

To check if a string does not start with specific characters using a regular expression, use the test() function and negate it.

Make sure your regular expression starts with ^, which is a special character that represents the start of the string.

function doesNotStartWithA(str) {

return !/^A/.test(str);

}Another approach is to use [^A].

[] denotes a set of characters to match, and ^ at the start of the set negates the set.

So [^A] matches any character other than A.

function doesNotStartWithA(str) {

return /^[^A]/.test(str);

}More Fundamentals Tutorials

- The parseInt Function in JavaScript

- The toFixed() Function in JavaScript

- The Nullish Coalescing Operator ?? in JavaScript

- Implementing Tuples in JavaScript

- Convert a JavaScript Enum to a String

- JavaScript Optional Chaining with Array Index

- How to Add 2 Arrays Together in JavaScript

- Remove From My Forums

-

Question

-

This regex is meant to match strings that DO NOT START WITH a specified string. for example «FBI_»

^(?i)([^(FBI_)])

(note use of case insensitive inline option).

Problem is that it also matches an empty string. Any idea on how to modify it to not match an empty string?

Regards

Ian

Answers

-

Hi

Thank you both very much. John, your negative lookahead assertion did the trick. I have now achieved atomicity (and learned what a Negative lookahead is!)

Final case insensitive RegEx:

^(?i)(?!(GS_))

Regards

Ian

-

Marked as answer by

Thursday, July 3, 2008 1:02 PM

-

Marked as answer by

A Regular Expression – or regex for short– is a syntax that allows you to match strings with specific patterns. Think of it as a suped-up text search shortcut, but a regular expression adds the ability to use quantifiers, pattern collections, special characters, and capture groups to create extremely advanced search patterns.

Regex can be used any time you need to query string-based data, such as:

- Analyzing command line output

- Parsing user input

- Examining server or program logs

- Handling text files with a consistent syntax, like a CSV

- Reading configuration files

- Searching and refactoring code

While doing all of these is theoretically possible without regex, when regexes hit the scene they act as a superpower for doing all of these tasks.

In this guide we’ll cover:

- What does a regex look like?

- How to read and write a regex

- What’s a “quantifier”?

- What’s a “pattern collection”?

- What’s a “regex token”?

- How to use a regex

- What’s a “regex flag“?

- What’s a “regex group”?

What does a regex look like?

In its simplest form, a regex in usage might look something like this:

This screenshot is of the regex101 website. All future screenshots will utilize this website for visual reference.

In the “Test” example the letters test formed the search pattern, same as a simple search.

These regexes are not always so simple, however. Here’s a regex that matches 3 numbers, followed by a “-“, followed by 3 numbers, followed by another “-“, finally ended by 4 numbers.

You know, like a phone number:

^(?:d{3}-){2}d{4}$This regex may look complicated, but two things to keep in mind:

- We’ll teach you how to read and write these in this article

- This is a fairly complex way of writing this regex.

In fact, most regexes can be written in multiple ways, just like other forms of programming. For example, the above can be rewritten into a longer but slightly more readable version:

^[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{4}$Most languages provide a built-in method for searching and replacing strings using regex. However, each language may have a different set of syntaxes based on what the language dictates.

In this article, we’ll focus on the ECMAScript variant of Regex, which is used in JavaScript and shares a lot of commonalities with other languages’ implementations of regex as well.

How to read (and write) regexes

Quantifiers

Regex quantifiers check to see how many times you should search for a character.

Here is a list of all quantifiers:

a|b– Match either “a” or “b?– Zero or one+– one or more*– zero or more{N}– Exactly N number of times (where N is a number)-

{N,}– N or more number of times (where N is a number) {N,M}– Between N and M number of times (where N and M are numbers and N < M)*?– Zero or more, but stop after first match

For example, the following regex:

Hello|GoodbyeMatches both the string “Hello” and “Goodbye”.

Meanwhile:

Hey?Will track “y” zero to one time, so will match up with “He” and “Hey”.

Alternatively:

Hello{1,3}Will match “Hello”, “Helloo”, “Hellooo”, but not “Helloooo”, as it is looking for the letter “o” between 1 and 3 times.

These can even be combined with one another:

He?llo{2}Here we’re looking for strings with zero-to-one instances of “e” and the letter “o” times 2, so this will match “Helloo” and “Hlloo”.

Greedy matching

One of the regex quantifiers we touched on in the previous list was the + symbol. This symbol matches one or more characters. This means that:

Hi+Will match everything from “Hi” to “Hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii”. This is because all quantifiers are considered “greedy” by default.

However, if you change it to be “lazy” using a question mark symbol (?) to the following, the behavior changes.

Hi+?Now, the i matcher will try to match as few times as possible. Since the +icon means “one or more”, it will only match one “i”. This means that if we input the string “Hiiiiiiiiiii”, only “Hi” will be matched.

While this isn’t particularly useful on its own, when combined with broader matches like the the . symbol, it becomes extremely important as we’ll cover in the next section. The .symbol is used in regex to find “any character”.

Now if you use:

H.*lloYou can match everything from “Hillo” to “Hello” to “Hellollollo”.

However, what if you want to only match “Hello” from the final example?

Well, simply make the search lazy with a ? and it’ll work as we want:

H.*?lloPattern collections

Pattern collections allow you to search for a collection of characters to match against. For example, using the following regex:

My favorite vowel is [aeiou]Code language: CSS (css)You could match the following strings:

My favorite vowel is a

My favorite vowel is e

My favorite vowel is i

My favorite vowel is o

My favorite vowel is uBut nothing else.

Here’s a list of the most common pattern collections:

[A-Z]– Match any uppercase character from “A” to “Z”[a-z]– Match any lowercase character from “a” to “z”[0-9]– Match any number[asdf]– Match any character that’s either “a”, “s”, “d”, or “f”[^asdf]– Match any character that’s not any of the following: “a”, “s”, “d”, or “f”

You can even combine these together:

[0-9A-Z]– Match any character that’s either a number or a capital letter from “A” to “Z”[^a-z]– Match any non-lowercase letter

General tokens

Not every character is so easily identifiable. While keys like “a” to “z” make sense to match using regex, what about the newline character?

The “newline” character is the character that you input whenever you press “Enter” to add a new line.

.– Any charactern– Newline charactert– Tab characters– Any whitespace character (includingt,nand a few others)S– Any non-whitespace characterw– Any word character (Uppercase and lowercase Latin alphabet, numbers 0-9, and_)W– Any non-word character (the inverse of thewtoken)b– Word boundary: The boundaries betweenwandW, but matches in-between charactersB– Non-word boundary: The inverse ofb^– The start of a line$– The end of a line– The literal character “”

So if you wanted to remove every character that starts a new word you could use something like the following regex:

s.And replace the results with an empty string. Doing this, the following:

Hello world how are youBecomes:

HelloorldowreouCombining with collections

These tokens aren’t just useful on their own, though! Let’s say that we want to remove any uppercase letter or whitespace character. Sure, we could write

[A-Z]|sBut we can actually merge these together and place our s token into the collection:

[A-Zs]Code language: JSON / JSON with Comments (json)Word boundaries

In our list of tokens, we mentioned b to match word boundaries. I thought I’d take a second to explain how it acts a bit differently from others.

Given a string like “This is a string”, you might expect the whitespace characters to be matched – however, this isn’t the case. Instead, it matches between the letters and the whitespace:

This can be tricky to get your head around, but it’s unusual to simply match against a word boundary. Instead, you might have something like the following to match full words:

bw+bYou can interpret that regex statement like this:

“A word boundary. Then, one or more ‘word’ characters. Finally, another word boundary”.

Start and end line

Two more tokens that we touched on are ^ and $. These mark off the start of a line and end of a line, respectively.

So, if you want to find the first word, you might do something like this:

^w+To match one or more “word” characters, but only immediately after the line starts. Remember, a “word” character is any character that’s an uppercase or lowercase Latin alphabet letters, numbers 0-9, and_.

Likewise, if you want to find the last word your regex might look something like this:

w+$However, just because these tokens typically end a line doesn’t mean that they can’t have characters after them.

For example, what if we wanted to find every whitespace character between newlines to act as a basic JavaScript minifier?

Well, we can say “Find all whitespace characters after the end of a line” using the following regex:

$s+Character escaping

While tokens are super helpful, they can introduce some complexity when trying to match strings that actually contain tokens. For example, say you have the following string in a blog post:

"The newline character is 'n'"Code language: JSON / JSON with Comments (json)Or want to find every instance of this blog post’s usage of the “n” string. Well, you can escape characters using. This means that your regex might look something like this:

\nHow to use a regex

Regular expressions aren’t simply useful for finding strings, however. You’re also able to use them in other methods to help modify or otherwise work with strings.

While many languages have similar methods, let’s use JavaScript as an example.

Creating and searching using regex

First, let’s look at how regex strings are constructed.

In JavaScript (along with many other languages), we place our regex inside of // blocks. The regex searching for a lowercase letter looks like this:

/[a-z]/This syntax then generates a RegExp object which we can use with built-in methods, like exec, to match against strings.

/[a-z]/.exec("a"); // Returns ["a"]

/[a-z]/.exec("0"); // Returns nullCode language: JavaScript (javascript)We can then use this truthiness to determine if a regex matched, like we’re doing in line #3 of this example:

We can also alternatively call a RegExp constructor with the string we want to convert into a regex:

const regex = new RegExp("[a-z]"); // Same as /[a-z]/Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Replacing strings with regex

You can also use a regex to search and replace a file’s contents as well. Say you wanted to replace any greeting with a message of “goodbye”. While you could do something like this:

function youSayHelloISayGoodbye(str) {

str = str.replace("Hello", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("Hi", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("Hey", "Goodbye"); str = str.replace("hello", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("hi", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("hey", "Goodbye");

return str;

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)There’s an easier alternative, using a regex:

function youSayHelloISayGoodbye(str) {

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/, "Goodbye");

return str;

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)However, something you might notice is that if you run youSayHelloISayGoodbyewith “Hello, Hi there”: it won’t match more than a single input:

Here, we should expect to see both “Hello” and “Hi” matched, but we don’t.

This is because we need to utilize a Regex “flag” to match more than once.

Flags

A regex flag is a modifier to an existing regex. These flags are always appended after the last forward slash in a regex definition.

Here’s a shortlist of some of the flags available to you.

g– Global, match more than oncem– Force $ and ^ to match each newline individuallyi– Make the regex case insensitive

This means that we could rewrite the following regex:

/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/To use the case insensitive flag instead:

/Hello|Hi|Hey/iWith this flag, this regex will now match:

Hello

HEY

Hi

HeLLoOr any other case-modified variant.

Global regex flag with string replacing

As we mentioned before, if you do a regex replace without any flags it will only replace the first result:

let str = "Hello, hi there!";

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/, "Goodbye");

console.log(str); // Will output "Goodbye, hi there"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)However, if you pass the global flag, you’ll match every instance of the greetings matched by the regex:

let str = "Hello, hi there!";

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/g, "Goodbye");

console.log(str); // Will output "Goodbye, hi there"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)A note about JavaScript’s global flag

When using a global JavaScript regex, you might run into some strange behavior when running the exec command more than once.

In particular, if you run exec with a global regex, it will return null every other time:

This is because, as MDN explains:

JavaScript RegExp objects are stateful when they have the global or sticky flags set… They store a lastIndex from the previous match. Using this internally, exec() can be used to iterate over multiple matches in a string of text…

The exec command attempts to start looking through the lastIndex moving forward. Because lastIndex is set to the length of the string, it will attempt to match "" – an empty string – against your regex until it is reset by another exec command again. While this feature can be useful in specific niche circumstances, it’s often confusing for new users.

To solve this problem, we can simply assign lastIndex to 0 before running each exec command:

Groups

When searching with a regex, it can be helpful to search for more than one matched item at a time. This is where “groups” come into play. Groups allow you to search for more than a single item at a time.

Here, we can see matching against both Testing 123 and Tests 123without duplicating the “123” matcher in the regex.

/(Testing|tests) 123/igGroups are defined by parentheses; there are two different types of groups–capture groups and non-capturing groups:

(...)– Group matching any three characters(?:...)– Non-capturing group matching any three characters

The difference between these two typically comes up in the conversation when “replace” is part of the equation.

For example, using the regex above, we can use the following JavaScript to replace the text with “Testing 234” and “tests 234”:

const regex = /(Testing|tests) 123/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1 234');

console.log(str); // Testing 234nTests 234"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)We’re using $1 to refer to the first capture group, (Testing|tests). We can also match more than a single group, like both (Testing|tests) and (123):

const regex = /(Testing|tests) (123)/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1 #$2');

console.log(str); // Testing #123nTests #123"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)However, this is only true for capture groups. If we change:

/(Testing|tests) (123)/igTo become:

/(?:Testing|tests) (123)/ig;Then there is only one captured group – (123) – and instead, the same code from above will output something different:

const regex = /(?:Testing|tests) (123)/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1');

console.log(str); // "123n123"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Named capture groups

While capture groups are awesome, it can easily get confusing when there are more than a few capture groups. The difference between $3 and $5 isn’t always obvious at a glance.

To help solve for this problem, regexes have a concept called “named capture groups”

(?<name>...)– Named capture group called “name” matching any three characters

You can use them in a regex like so to create a group called “num” that matches three numbers:

/Testing (?<num>d{3})/Code language: HTML, XML (xml)Then, you can use it in a replacement like so:

const regex = /Testing (?<num>d{3})/

let str = "Testing 123";

str = str.replace(regex, "Hello $<num>")

console.log(str); // "Hello 123"Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Named back reference

Sometimes it can be useful to reference a named capture group inside of a query itself. This is where “back references” can come into play.

k<name>Reference named capture group “name” in a search query

Say you want to match:

Hello there James. James, how are you doing?But not:

Hello there James. Frank, how are you doing?While you could write a regex that repeats the word “James” like the following:

/.*James. James,.*/A better alternative might look something like this:

/.*(?<name>James). k<name>,.*/Code language: HTML, XML (xml)Now, instead of having two names hardcoded, you only have one.

Lookahead and lookbehind groups

Lookahead and behind groups are extremely powerful and often misunderstood.

There are four different types of lookahead and behinds:

(?!)– negative lookahead(?=)– positive lookahead(?<=)– positive lookbehind(?<!)– negative lookbehind

Lookahead works like it sounds like: It either looks to see that something is after the lookahead group or is not after the lookahead group, depending on if it’s positive or negative.

As such, using the negative lookahead like so:

/B(?!A)/Will allow you to match BC but not BA.

You can even combine these with ^ and $ tokens to try to match full strings. For example, the following regex will match any string that does not start with “Test”

/^(?!Test).*$/gmLikewise, we can switch this to a positive lookahead to enforce that our string muststart with “Test”

/^(?=Test).*$/gmPutting it all together

Regexes are extremely powerful and can be used in a myriad of string manipulations. Knowing them can help you refactor codebases, script quick language changes, and more!

Let’s go back to our initial phone number regex and try to understand it again:

^(?:d{3}-){2}d{4}$Remember that this regex is looking to match phone numbers such as:

555-555-5555Here this regex is:

- Using

^and$to define the start and end of a regex line. - Using a non-capturing group to find three digits then a dash

- Repeating this group twice, to match

555-555-

- Repeating this group twice, to match

- Finding the last 4 digits of the phone number

Hopefully, this article has been a helpful introduction to regexes for you. If you’d like to see quick definitions of useful regexes, check out our cheat sheet.