Sometimes we have a requirement where we have to filter out lines from logs, which start from certain word OR end with certain word. In this Java regex word boundary tutorial, we will learn to create regex to filter out lines which either start or end with a certain word.

Table of Contents 1. Boundary matchers 2. Match word at the start of content 3. Match word at the end of content 4. Match word at the start of line 5. Match word at the end of line

1. Boundary matchers

Boundary macthers help to find a particular word, but only if it appears at the beginning or end of a line. They do not match any characters. Instead, they match at certain positions, effectively anchoring the regular expression match at those positions.

The following table lists and explains all the boundary matchers.

| Boundary token | Description |

|---|---|

^ |

The beginning of a line |

$ |

The end of a line |

b |

A word boundary |

B |

A non-word boundary |

A |

The beginning of the input |

G |

The end of the previous match |

Z |

The end of the input but for the final terminator, if any |

z |

The end of the input |

2. Java regex word boundary – Match word at the start of content

The anchor "A" always matches at the very start of the whole text, before the first character. That is the only place where it matches. Place "A" at the start of your regular expression to test whether the content begins with the text you want to match.

The "A" must be uppercase. Alternatively, you can use "^" as well.

^wordToSearch OR AwordToSearch

String content = "begin here to start, and go there to endn" +

"come here to begin, and end there to finishn" +

"begin here to start, and go there to end";

String regex = "^begin";

//OR

//String regex = "\Abegin";

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(regex, Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE);

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher(content);

while (matcher.find())

{

System.out.print("Start index: " + matcher.start());

System.out.print(" End index: " + matcher.end() + " ");

System.out.println(matcher.group());

}

Output:

Start index: 0 End index: 5 begin

3. Java regex word boundary – Match word at the end of content

The anchors "Z" and "z" always match at the very end of the content, after the last character. Place "Z" or "z" at the end of your regular expression to test whether the content ends with the text you want to match.

Alternatively, you can use "$" as well.

wordToSearch$ OR wordToSearchZ

String content = "begin here to start, and go there to endn" +

"come here to begin, and end there to finishn" +

"begin here to start, and go there to end";

String regex = "end$";

String regex = "end\Z";

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(regex, Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE);

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher(content);

while (matcher.find())

{

System.out.print("Start index: " + matcher.start());

System.out.print(" End index: " + matcher.end() + " ");

System.out.println(matcher.group());

}

Output:

Start index: 122 End index: 125 end

4. Java regex word boundary – Match word at the start of line

You can use "(?m)" to tun on “multi-line” mode to match a word at start of every time.

“Multi-line” mode affects only the caret (^) and dollar ($) sign.

(?m)^wordToSearch

String content = "begin here to start, and go there to endn" +

"come here to begin, and end there to finishn" +

"begin here to start, and go there to end";

String regex = "(?m)^begin";

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(regex, Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE);

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher(content);

while (matcher.find())

{

System.out.print("Start index: " + matcher.start());

System.out.print(" End index: " + matcher.end() + " ");

System.out.println(matcher.group());

}

Output:

Start index: 0 End index: 5 begin

Start index: 85 End index: 90 begin

5. Java regex word boundary – Match word at the end of line

You can use "(?m)" to tun on “multi-line” mode to match a word at end of every time.

(?m)wordToSearch$

String content = "begin here to start, and go there to endn" +

"come here to begin, and end there to finishn" +

"begin here to start, and go there to end";

String regex = "(?m)end$";

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(regex, Pattern.CASE_INSENSITIVE);

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher(content);

while (matcher.find())

{

System.out.print("Start index: " + matcher.start());

System.out.print(" End index: " + matcher.end() + " ");

System.out.println(matcher.group());

}

Output:

Start index: 37 End index: 40 end

Start index: 122 End index: 125 end

Let me know of your thoughts on this Java regex word boundary example.

Happy Learning !!

References:

Java regex docs

| Symbols | Hits | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| sa | all words containing the string sa | sa, vasaku, sahata, tisa |

| bsa | all words starting with sa | sa, sahata, sana; NOT vasaku, tisa |

| bsab | all words sa | sa |

| bsa..b | all words consisting of sa + two letters that follow sa |

saka, saku, sana |

| bsaw+ | all words beginning with sa, but not the word sa by itself | sahata, sana |

| b.*anab | al words ending in ana | sinana, tamuana, sana, bana, maana |

| (….)l | all words with four reduplicated letters | pakupaku, vapakupaku, mahumahun, vamahumahun |

| b(….)l | all words beginning with four reduplicated letters |

pakupaku; NOT vapakupaku |

| b(….)lanab | all words beginning with four reduplicated letters and ending in ana |

vasuvasuana, hunuhunuana |

| bva(….)l | all words consisting of the prefix va- + four reduplicated letters |

vapakupaku, vagunagunaha |

| bvahaa?b | all tokens of vahaa and vaha | vahaa and vaha |

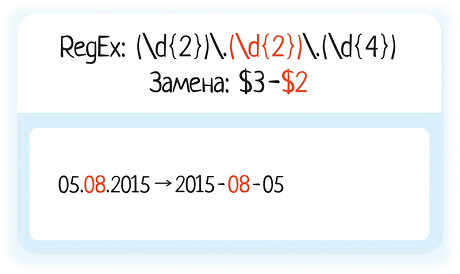

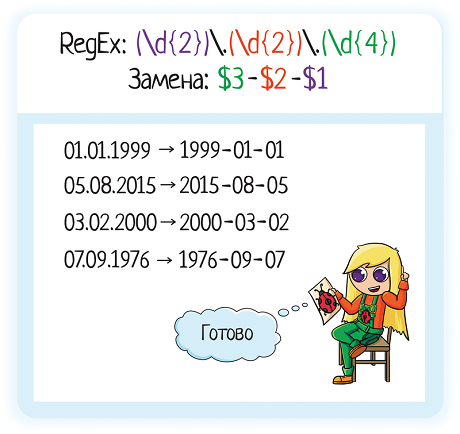

Регулярные выражения (их еще называют regexp, или regex) — это механизм для поиска и замены текста. В строке, файле, нескольких файлах… Их используют разработчики в коде приложения, тестировщики в автотестах, да просто при работе в командной строке!

Чем это лучше простого поиска? Тем, что позволяет задать шаблон.

Например, на вход приходит дата рождения в формате ДД.ММ.ГГГГГ. Вам надо передать ее дальше, но уже в формате ГГГГ-ММ-ДД. Как это сделать с помощью простого поиска? Вы же не знаете заранее, какая именно дата будет.

А регулярное выражение позволяет задать шаблон «найди мне цифры в таком-то формате».

Для чего применяют регулярные выражения?

-

Удалить все файлы, начинающиеся на test (чистим за собой тестовые данные)

-

Найти все логи

-

grep-нуть логи

-

Найти все даты

-

…

А еще для замены — например, чтобы изменить формат всех дат в файле. Если дата одна, можно изменить вручную. А если их 200, проще написать регулярку и подменить автоматически. Тем более что регулярные выражения поддерживаются даже простым блокнотом (в Notepad++ они точно есть).

В этой статье я расскажу о том, как применять регулярные выражения для поиска и замены. Разберем все основные варианты.

Содержание

-

Где пощупать

-

Поиск текста

-

Поиск любого символа

-

Поиск по набору символов

-

Перечисление вариантов

-

Метасимволы

-

Спецсимволы

-

Квантификаторы (количество повторений)

-

Позиция внутри строки

-

Использование ссылки назад

-

Просмотр вперед и назад

-

Замена

-

Статьи и книги по теме

-

Итого

Где пощупать

Любое регулярное выражение из статьи вы можете сразу пощупать. Так будет понятнее, о чем речь в статье — вставили пример из статьи, потом поигрались сами, делая шаг влево, шаг вправо. Где тренироваться:

-

Notepad++ (установить Search Mode → Regular expression)

-

Regex101 (мой фаворит в онлайн вариантах)

-

Myregexp

-

Regexr

Инструменты есть, теперь начнём

Поиск текста

Самый простой вариант регэкспа. Работает как простой поиск — ищет точно такую же строку, как вы ввели.

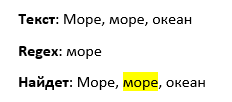

Текст: Море, море, океан

Regex: море

Найдет: Море, море, океан

Выделение курсивом не поможет моментально ухватить суть, что именно нашел regex, а выделить цветом в статье я не могу. Атрибут BACKGROUND-COLOR не сработал, поэтому я буду дублировать регулярки текстом (чтобы можно было скопировать себе) и рисунком, чтобы показать, что именно regex нашел:

Обратите внимание, нашлось именно «море», а не первое «Море». Регулярные выражения регистрозависимые!

Хотя, конечно, есть варианты. В JavaScript можно указать дополнительный флажок i, чтобы не учитывать регистр при поиске. В блокноте (notepad++) тоже есть галка «Match case». Но учтите, что это не функция по умолчанию. И всегда стоит проверить, регистрозависимая ваша реализация поиска, или нет.

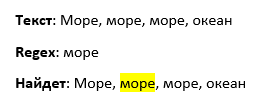

А что будет, если у нас несколько вхождений искомого слова?

Текст: Море, море, море, океан

Regex: море

Найдет: Море, море, море, океан

По умолчанию большинство механизмов обработки регэкспа вернет только первое вхождение. В JavaScript есть флаг g (global), с ним можно получить массив, содержащий все вхождения.

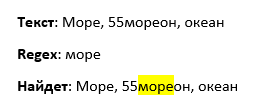

А что, если у нас искомое слово не само по себе, это часть слова? Регулярное выражение найдет его:

Текст: Море, 55мореон, океан

Regex: море

Найдет: Море, 55мореон, океан

Это поведение по умолчанию. Для поиска это даже хорошо. Вот, допустим, я помню, что недавно в чате коллега рассказывала какую-то историю про интересный баг в игре. Что-то там связанное с кораблем… Но что именно? Уже не помню. Как найти?

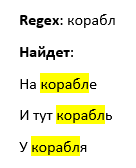

Если поиск работает только по точному совпадению, мне придется перебирать все падежи для слова «корабль». А если он работает по включению, я просто не буду писать окончание, и все равно найду нужный текст:

Regex: корабл

Найдет:

На корабле

И тут корабль

У корабля

Это статический, заранее заданный текст. Но его можно найти и без регулярок. Регулярные выражения особенно хороши, когда мы не знаем точно, что мы ищем. Мы знаем часть слова, или шаблон.

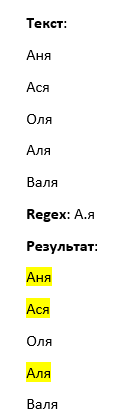

Поиск любого символа

. — найдет любой символ (один).

Текст:

Аня

Ася

Оля

Аля

Валя

Regex: А.я

Результат:

Аня

Ася

ОляАля

Валя

Точка найдет вообще любой символ, включая цифры, спецсисимволы, даже пробелы. Так что кроме нормальных имен, мы найдем и такие значения:

А6я

А&я

А я

Учтите это при поиске! Точка очень удобный символ, но в то же время очень опасный — если используете ее, обязательно тестируйте получившееся регулярное выражение. Найдет ли оно то, что нужно? А лишнее не найдет?

Точку точка тоже найдет!

Regex: file.

Найдет:

file.txt

file1.txt

file2.xls

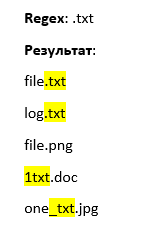

Но что, если нам надо найти именно точку? Скажем, мы хотим найти все файлы с расширением txt и пишем такой шаблон:

Regex: .txt

Результат:

file.txt

log.txt

file.png1txt.doc

one_txt.jpg

Да, txt файлы мы нашли, но помимо них еще и «мусорные» значения, у которых слово «txt» идет в середине слова. Чтобы отсечь лишнее, мы можем использовать позицию внутри строки (о ней мы поговорим чуть дальше).

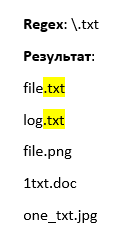

Но если мы хотим найти именно точку, то нужно ее заэкранировать — то есть добавить перед ней обратный слеш:

Regex: .txt

Результат:

file.txt

log.txt

file.png

1txt.doc

one_txt.jpg

Также мы будем поступать со всеми спецсимволами. Хотим найти именно такой символ в тексте? Добавляем перед ним обратный слеш.

Правило поиска для точки:

. — любой символ

. — точка

Поиск по набору символов

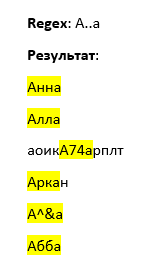

Допустим, мы хотим найти имена «Алла», «Анна» в списке. Можно попробовать поиск через точку, но кроме нормальных имен, вернется всякая фигня:

Regex: А..а

Результат:

Анна

Алла

аоикА74арплт

Аркан

А^&а

Абба

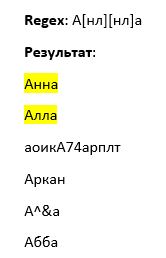

Если же мы хотим именно Анну да Аллу, вместо точки нужно использовать диапазон допустимых значений. Ставим квадратные скобки, а внутри них перечисляем нужные символы:

Regex: А[нл][нл]а

Результат:

Анна

Алла

аоикА74арплт

Аркан

А^&а

Абба

Вот теперь результат уже лучше! Да, нам все еще может вернуться «Анла», но такие ошибки исправим чуть позже.

Как работают квадратные скобки? Внутри них мы указываем набор допустимых символов. Это может быть перечисление нужных букв, или указание диапазона:

[нл] — только «н» и «л»

[а-я] — все русские буквы в нижнем регистре от «а» до «я» (кроме «ё»)

[А-Я] — все заглавные русские буквы

[А-Яа-яЁё] — все русские буквы

[a-z] — латиница мелким шрифтом

[a-zA-Z] — все английские буквы

[0-9] — любая цифра

[В-Ю] — буквы от «В» до «Ю» (да, диапазон — это не только от А до Я)

[А-ГО-Р] — буквы от «А» до «Г» и от «О» до «Р»

Обратите внимание — если мы перечисляем возможные варианты, мы не ставим между ними разделителей! Ни пробел, ни запятую — ничего.

[абв] — только «а», «б» или «в»

[а б в] — «а», «б», «в», или пробел (что может привести к нежелательному результату)

[а, б, в] — «а», «б», «в», пробел или запятая

Единственный допустимый разделитель — это дефис. Если система видит дефис внутри квадратных скобок — значит, это диапазон:

-

Символ до дефиса — начало диапазона

-

Символ после — конец

Один символ! Не два или десять, а один! Учтите это, если захотите написать что-то типа [1-31]. Нет, это не диапазон от 1 до 31, эта запись читается так:

-

Диапазон от 1 до 3

-

И число 1

Здесь отсутствие разделителей играет злую шутку с нашим сознанием. Ведь кажется, что мы написали диапазон от 1 до 31! Но нет. Поэтому, если вы пишете регулярные выражения, очень важно их тестировать. Не зря же мы тестировщики! Проверьте то, что написали! Особенно, если с помощью регулярного выражения вы пытаетесь что-то удалить =)) Как бы не удалили лишнее…

Указание диапазона вместо точки помогает отсеять заведомо плохие данные:

Regex: А.я или А[а-я]я

Результат для обоих:

Аня

Ася

Аля

Результат для «А.я»:

А6я

А&я

А я

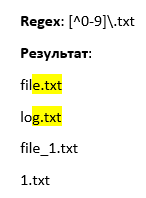

^ внутри [] означает исключение:

[^0-9] — любой символ, кроме цифр

[^ёЁ] — любой символ, кроме буквы «ё»

[^а-в8] — любой символ, кроме букв «а», «б», «в» и цифры 8

Например, мы хотим найти все txt файлы, кроме разбитых на кусочки — заканчивающихся на цифру:

Regex: [^0-9].txt

Результат:

file.txt

log.txt

file_1.txt

1.txt

Так как квадратные скобки являются спецсимволами, то их нельзя найти в тексте без экранирования:

Regex: fruits[0]

Найдет: fruits0

Не найдет: fruits[0]

Это регулярное выражение говорит «найди мне текст «fruits», а потом число 0». Квадратные скобки не экранированы — значит, внутри будет набор допустимых символов.

Если мы хотим найти именно 0-левой элемент массива фруктов, надо записать так:

Regex: fruits[0]

Найдет: fruits[0]

Не найдет: fruits0

А если мы хотим найти все элементы массива фруктов, мы внутри экранированных квадратных скобок ставим неэкранированные!

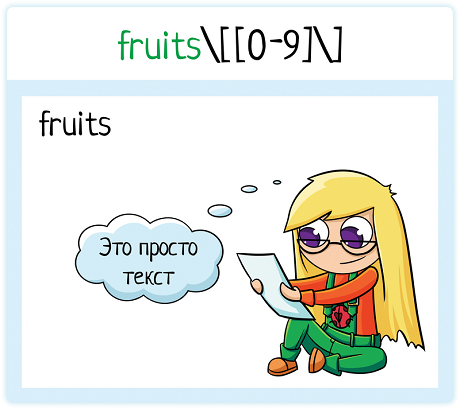

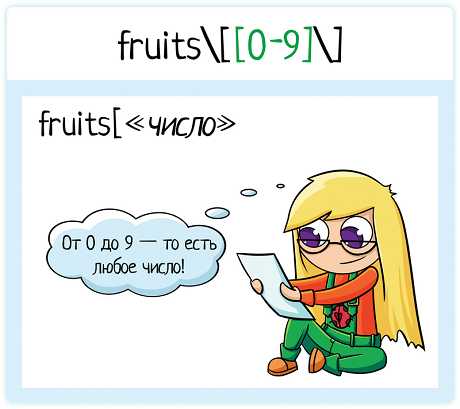

Regex: fruits[[0-9]]

Найдет:

fruits[0] = “апельсин”;

fruits[1] = “яблоко”;

fruits[2] = “лимон”;

Не найдет:

cat[0] = “чеширский кот”;

Конечно, «читать» такое регулярное выражение становится немного тяжело, столько разных символов написано…

Без паники! Если вы видите сложное регулярное выражение, то просто разберите его по частям. Помните про основу эффективного тайм-менеджмента? Слона надо есть по частям.

Допустим, после отпуска накопилась гора писем. Смотришь на нее и сразу впадаешь в уныние:

— Ууууууу, я это за день не закончу!

Проблема в том, что груз задачи мешает работать. Мы ведь понимаем, что это надолго. А большую задачу делать не хочется… Поэтому мы ее откладываем, беремся за задачи поменьше. В итоге да, день прошел, а мы не успели закончить.

А если не тратить время на размышления «сколько времени это у меня займет», а сосредоточиться на конкретной задаче (в данном случае — первом письме из стопки, потом втором…), то не успеете оглянуться, как уже всё разгребли!

Разберем по частям регулярное выражение — fruits[[0-9]]

Сначала идет просто текст — «fruits».

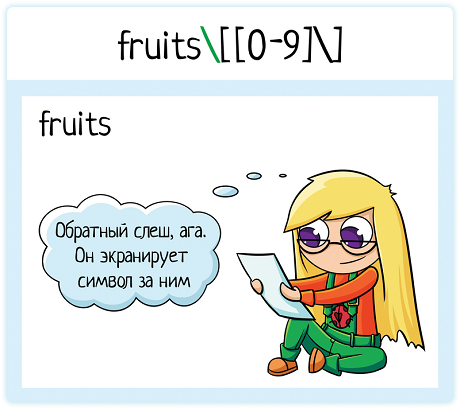

Потом обратный слеш. Ага, он что-то экранирует.

Что именно? Квадратную скобку. Значит, это просто квадратная скобка в моем тексте — «fruits[»

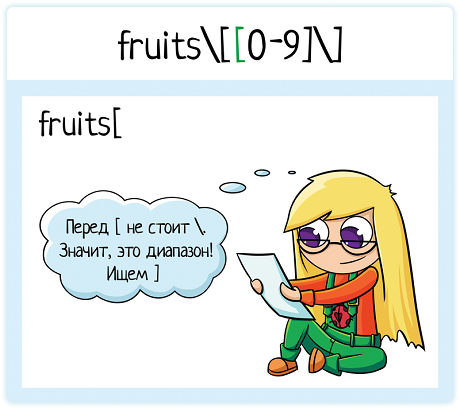

Дальше снова квадратная скобка. Она не экранирована — значит, это набор допустимых значений. Ищем закрывающую квадратную скобку.

Нашли. Наш набор: [0-9]. То есть любое число. Но одно. Там не может быть 10, 11 или 325, потому что квадратные скобки без квантификатора (о них мы поговорим чуть позже) заменяют ровно один символ.

Пока получается: fruits[«любое однозназначное число»

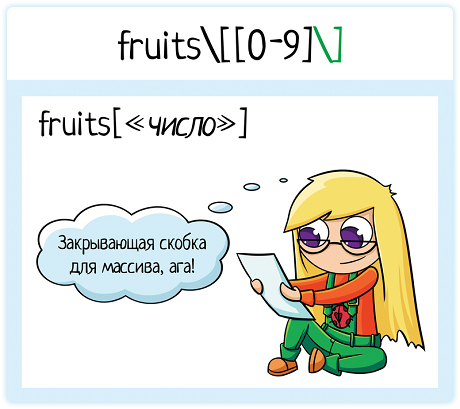

Дальше снова обратный слеш. То есть следующий за ним спецсимвол будет просто символом в моем тексте.

А следующий символ — ]

Получается выражение: fruits[«любое однозназначное число»]

Наше выражение найдет значения массива фруктов! Не только нулевое, но и первое, и пятое… Вплоть до девятого:

Regex: fruits[[0-9]]

Найдет:

fruits[0] = “апельсин”;

fruits[1] = “яблоко”;

fruits[9] = “лимон”;

Не найдет:

fruits[10] = “банан”;

fruits[325] = “ абрикос ”;

Как найти вообще все значения массива, см дальше, в разделе «квантификаторы».

А пока давайте посмотрим, как с помощью диапазонов можно найти все даты.

Какой у даты шаблон? Мы рассмотрим ДД.ММ.ГГГГ:

-

2 цифры дня

-

точка

-

2 цифры месяца

-

точка

-

4 цифры года

Запишем в виде регулярного выражения: [0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9].

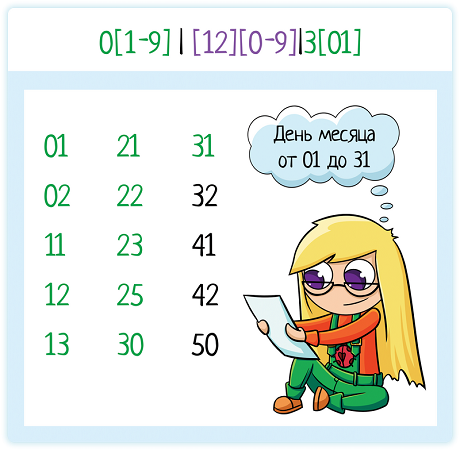

Напомню, что мы не можем записать диапазон [1-31]. Потому что это будет значить не «диапазон от 1 до 31», а «диапазон от 1 до 3, плюс число 1». Поэтому пишем шаблон для каждой цифры отдельно.

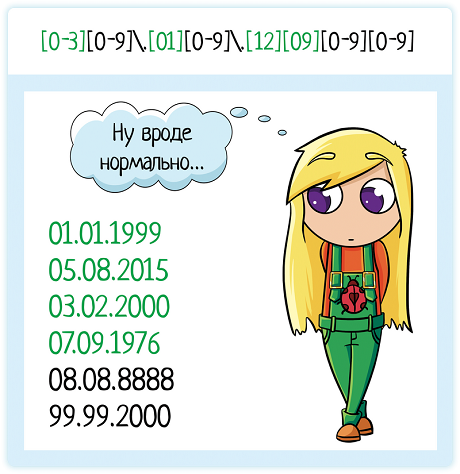

В принципе, такое выражение найдет нам даты среди другого текста. Но что, если с помощью регулярки мы проверяем введенную пользователем дату? Подойдет ли такой regexp?

Давайте его протестируем! Как насчет 8888 года или 99 месяца, а?

Regex: [0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9]

Найдет:

01.01.1999

05.08.2015

Тоже найдет:

08.08.8888

99.99.2000

Попробуем ограничить:

-

День месяца может быть максимум 31 — первая цифра [0-3]

-

Максимальный месяц 12 — первая цифра [01]

-

Год или 19.., или 20.. — первая цифра [12], а вторая [09]

Вот, уже лучше, явно плохие данные регулярка отсекла. Надо признать, она отсечет довольно много тестовых данных, ведь обычно, когда хотят именно сломать, то фигачат именно «9999» год или «99» месяц…

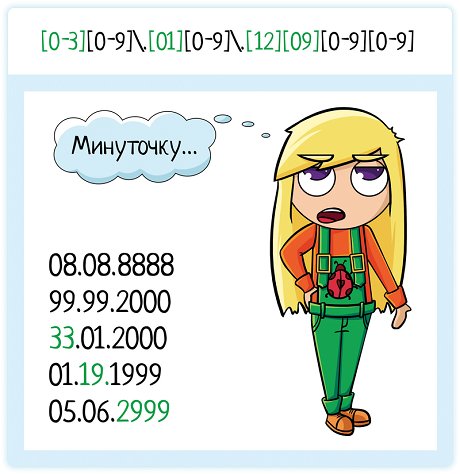

Однако если мы присмотримся внимательнее к регулярному выражению, то сможем найти в нем дыры:

Regex: [0-3][0-9].[0-1][0-9].[12][09][0-9][0-9]

Не найдет:

08.08.8888

99.99.2000

Но найдет:

33.01.2000

01.19.1999

05.06.2999

Мы не можем с помощью одного диапазона указать допустимые значения. Или мы потеряем 31 число, или пропустим 39. И если мы хотим сделать проверку даты, одних диапазонов будет мало. Нужна возможность перечислить варианты, о которой мы сейчас и поговорим.

Перечисление вариантов

Квадратные скобки [] помогают перечислить варианты для одного символа. Если же мы хотим перечислить слова, то лучше использовать вертикальную черту — |.

Regex: Оля|Олечка|Котик

Найдет:

Оля

Олечка

Котик

Не найдет:

Оленька

Котенка

Можно использовать вертикальную черту и для одного символа. Можно даже внутри слова — тогда вариативную букву берем в круглые скобки

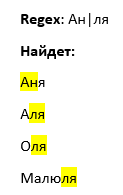

Regex: А(н|л)я

Найдет:

Аня

Аля

Круглые скобки обозначают группу символов. В этой группе у нас или буква «н», или буква «л». Зачем нужны скобки? Показать, где начинается и заканчивается группа. Иначе вертикальная черта применится ко всем символам — мы будем искать или «Ан», или «ля»:

Regex: Ан|ля

Найдет:

Аня

Аля

Оля

Малюля

А если мы хотим именно «Аня» или «Аля», то перечисление используем только для второго символа. Для этого берем его в скобки.

Эти 2 варианта вернут одно и то же:

-

А(н|л)я

-

А[нл]я

Но для замены одной буквы лучше использовать [], так как сравнение с символьным классом выполняется проще, чем обработка группы с проверкой на все её возможные модификаторы.

Давайте вернемся к задаче «проверить введенную пользователем дату с помощью регулярных выражений». Мы пробовали записать для дня диапазон [0-3][0-9], но он пропускает значения 33, 35, 39… Это нехорошо!

Тогда распишем ТЗ подробнее. Та-а-а-ак… Если первая цифра:

-

0 — вторая может от 1 до 9 (даты 00 быть не может)

-

1, 2 — вторая может от 0 до 9

-

3 — вторая только 0 или 1

Составим регулярные выражения на каждый пункт:

-

0[1-9]

-

[12][0-9]

-

3[01]

А теперь осталось их соединить в одно выражение! Получаем: 0[1-9]|[12][0-9]|3[01]

По аналогии разбираем месяц и год. Но это остается вам для домашнего задания =)

Потом, когда распишем регулярки отдельно для дня, месяца и года, собираем все вместе:

(<день>).(<месяц>).(<год>)

Обратите внимание — каждую часть регулярного выражения мы берем в скобки. Зачем? Чтобы показать системе, где заканчивается выбор. Вот смотрите, допустим, что для месяца и года у нас осталось выражение:

[0-1][0-9].[12][09][0-9][0-9]

Подставим то, что написали для дня:

0[1-9]|[12][0-9]|3[01].[0-1][0-9].[12][09][0-9][0-9]

Как читается это выражение?

-

ИЛИ 0[1-9]

-

ИЛИ [12][0-9]

-

ИЛИ 3[01].[0-1][0-9].[12][09][0-9][0-9]

Видите проблему? Число «19» будет считаться корректной датой. Система не знает, что перебор вариантов | закончился на точке после дня. Чтобы она это поняла, нужно взять перебор в скобки. Как в математике, разделяем слагаемые.

Так что запомните — если перебор идет в середине слова, его надо взять в круглые скобки!

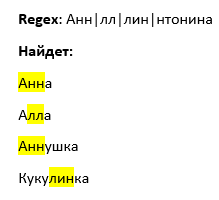

Regex: А(нн|лл|лин|нтонин)а

Найдет:

Анна

Алла

Алина

Антонина

Без скобок:

Regex: Анн|лл|лин|нтонина

Найдет:

Анна

Алла

Аннушка

Кукулинка

Итого, если мы хотим указать допустимые значения:

-

Одного символа — используем []

-

Нескольких символов или целого слова — используем |

Метасимволы

Если мы хотим найти число, то пишем диапазон [0-9].

Если букву, то [а-яА-ЯёЁa-zA-Z].

А есть ли другой способ?

Есть! В регулярных выражениях используются специальные метасимволы, которые заменяют собой конкретный диапазон значений:

|

Символ |

Эквивалент |

Пояснение |

|

d |

[0-9] |

Цифровой символ |

|

D |

[^0-9] |

Нецифровой символ |

|

s |

[ fnrtv] |

Пробельный символ |

|

S |

[^ fnrtv] |

Непробельный символ |

|

w |

[[:word:]] |

Буквенный или цифровой символ или знак подчёркивания |

|

W |

[^[:word:]] |

Любой символ, кроме буквенного или цифрового символа или знака подчёркивания |

|

. |

Вообще любой символ |

Это самые распространенные символы, которые вы будете использовать чаще всего. Но давайте разберемся с колонкой «эквивалент». Для d все понятно — это просто некие числа. А что такое «пробельные символы»? В них входят:

|

Символ |

Пояснение |

|

Пробел |

|

|

r |

Возврат каретки (Carriage return, CR) |

|

n |

Перевод строки (Line feed, LF) |

|

t |

Табуляция (Tab) |

|

v |

Вертикальная табуляция (vertical tab) |

|

f |

Конец страницы (Form feed) |

|

[b] |

Возврат на 1 символ (Backspace) |

Из них вы чаще всего будете использовать сам пробел и перевод строки — выражение «rn». Напишем текст в несколько строк:

Первая строка

Вторая строка

Для регулярного выражения это:

Первая строкаrnВторая строка

А вот что такое backspace в тексте? Как его можно увидеть вообще? Это же если написать символ и стереть его. В итоге символа нет! Неужели стирание хранится где-то в памяти? Но тогда это было бы ужасно, мы бы вообще ничего не смогли найти — откуда нам знать, сколько раз текст исправляли и в каких местах там теперь есть невидимый символ [b]?

Выдыхаем — этот символ не найдет все места исправления текста. Просто символ backspace — это ASCII символ, который может появляться в тексте (ASCII code 8, или 10 в octal). Вы можете «создать» его, написать в консоли браузера (там используется JavaScript):

console.log("abcbbdef");Результат команды:

adefМы написали «abc», а потом стерли «b» и «с». В итоге пользователь в консоли их не видит, но они есть. Потому что мы прямо в коде прописали символ удаления текста. Не просто удалили текст, а прописали этот символ. Вот такой символ регулярное выражение [b] и найдет.

См также:

What’s the use of the [b] backspace regex? — подробнее об этом символе

Но обычно, когда мы вводим s, мы имеем в виду пробел, табуляцию, или перенос строки.

Ок, с этими эквивалентами разобрались. А что значит [[:word:]]? Это один из способов заменить диапазон. Чтобы запомнить проще было, написали значения на английском, объединив символы в классы. Какие есть классы:

|

Класс символов |

Пояснение |

|

[[:alnum:]] |

Буквы или цифры: [а-яА-ЯёЁa-zA-Z0-9] |

|

[[:alpha:]] |

Только буквы: [а-яА-ЯёЁa-zA-Z] |

|

[[:digit:]] |

Только цифры: [0-9] |

|

[[:graph:]] |

Только отображаемые символы (пробелы, служебные знаки и т. д. не учитываются) |

|

[[:print:]] |

Отображаемые символы и пробелы |

|

[[:space:]] |

Пробельные символы [ fnrtv] |

|

[[:punct:]] |

Знаки пунктуации: ! » # $ % & ‘ ( ) * + , -. / : ; < = > ? @ [ ] ^ _ ` { | } |

|

[[:word:]] |

Буквенный или цифровой символ или знак подчёркивания: [а-яА-ЯёЁa-zA-Z0-9_] |

Теперь мы можем переписать регулярку для проверки даты, которая выберет лишь даты формата ДД.ММ.ГГГГГ, отсеяв при этом все остальное:

[0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9].[0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9]

↓

dd.dd.dddd

Согласитесь, через метасимволы запись посимпатичнее будет =))

Спецсимволы

Большинство символов в регулярном выражении представляют сами себя за исключением специальных символов:

[ ] / ^ $ . | ? * + ( ) { }

Эти символы нужны, чтобы обозначить диапазон допустимых значений или границу фразы, указать количество повторений, или сделать что-то еще. В разных типах регулярных выражений этот набор различается (см «разновидности регулярных выражений»).

Если вы хотите найти один из этих символов внутри вашего текста, его надо экранировать символом (обратная косая черта).

Regex: 2^2 = 4

Найдет: 2^2 = 4

Можно экранировать целую последовательность символов, заключив её между Q и E (но не во всех разновидностях).

Regex: Q{кто тут?}E

Найдет: {кто тут?}

Квантификаторы (количество повторений)

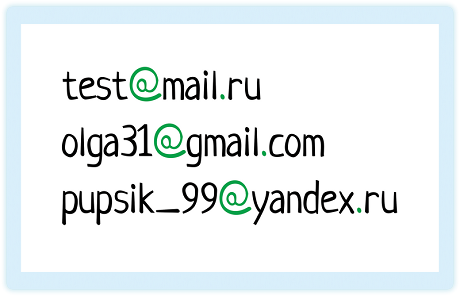

Усложняем задачу. Есть некий текст, нам нужно вычленить оттуда все email-адреса. Например:

-

test@mail.ru

-

olga31@gmail.com

-

pupsik_99@yandex.ru

Как составляется регулярное выражение? Нужно внимательно изучить данные, которые мы хотим получить на выходе, и составить по ним шаблон. В email два разделителя — собачка «@» и точка «.».

Запишем ТЗ для регулярного выражения:

-

Буквы / цифры / _

-

Потом @

-

Снова буквы / цифры / _

-

Точка

-

Буквы

Так, до собачки у нас явно идет метасимвол «w», туда попадет и просто текст (test), и цифры (olga31), и подчеркивание (pupsik_99). Но есть проблема — мы не знаем, сколько таких символов будет. Это при поиске даты все ясно — 2 цифры, 2 цифры, 4 цифры. А тут может быть как 2, так и 22 символа.

И тут на помощь приходят квантификаторы — так называют специальные символы в регулярных выражениях, которые указывают количество повторений текста.

Символ «+» означает «одно или более повторений», это как раз то, что нам надо! Получаем: w+@

После собачки и снова идет w, и снова от одного повторения. Получаем: w+@w+.

После точки обычно идут именно символы, но для простоты можно снова написано w. И снова несколько символов ждем, не зная точно сколько. Итого получилось выражение, которое найдет нам email любой длины:

Regex: w+@w+.w+

Найдет:

test@mail.ru

olga31@gmail.com

pupsik_99_and_slonik_33_and_mikky_87_and_kotik_28@yandex.megatron

Какие есть квантификаторы, кроме знака «+»?

|

Квантификатор |

Число повторений |

|

? |

Ноль или одно |

|

* |

Ноль или более |

|

+ |

Один или более |

Символ * часто используют с точкой — когда нам неважно, какой идет текст до интересующей нас фразы, мы заменяем его на «.*» — любой символ ноль или более раз.

Regex: .*dd.dd.dddd.*

Найдет:

01.01.2000

Приходи на ДР 09.08.2015! Будет весело!

Но будьте осторожны! Если использовать «.*» повсеместно, можно получить много ложноположительных срабатываний:

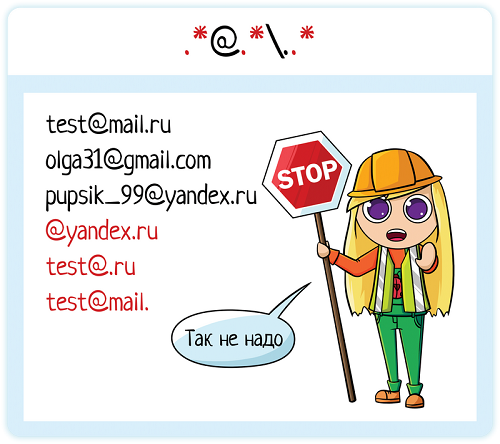

Regex: .*@.*..*

Найдет:

test@mail.ru

olga31@gmail.com

pupsik_99@yandex.ru

Но также найдет:

@yandex.ru

test@.ru

test@mail.

Уж лучше w, и плюсик вместо звездочки.

А вот есть мы хотим найти все лог-файлы, которые нумеруются — log, log1, log2… log133, то * подойдет хорошо:

Regex: logd*.txt

Найдет:

log.txt

log1.txt

log2.txt

log3.txt

log33.txt

log133.txt

А знак вопроса (ноль или одно повторение) поможет нам найти людей с конкретной фамилией — причем всех, и мужчин, и женщин:

Regex: Назина?

Найдет:

Назин

Назина

Если мы хотим применить квантификатор к группе символов или нескольким словам, их нужно взять в скобки:

Regex: (Хихи)*(Хаха)*

Найдет:

ХихиХаха

ХихиХихиХихи

Хихи

Хаха

ХихиХихиХахаХахаХаха

(пустота — да, её такая регулярка тоже найдет)

Квантификаторы применяются к символу или группе в скобках, которые стоят перед ним.

А что, если мне нужно определенное количество повторений? Скажем, я хочу записать регулярное выражение для даты. Пока мы знаем только вариант «перечислить нужный метасимвол нужное количество раз» — dd.dd.dddd.

Ну ладно 2-4 раза повторение идет, а если 10? А если повторить надо фразу? Так и писать ее 10 раз? Не слишком удобно. А использовать * нельзя:

Regex: d*.d*.d*

Найдет:

.0.1999

05.08.20155555555555555

03444.025555.200077777777777777

Чтобы указать конкретное количество повторений, их надо записать внутри фигурных скобок:

|

Квантификатор |

Число повторений |

|

{n} |

Ровно n раз |

|

{m,n} |

От m до n включительно |

|

{m,} |

Не менее m |

|

{,n} |

Не более n |

Таким образом, для проверки даты можно использовать как перечисление d n раз, так и использование квантификатора:

dd.dd.dddd

d{2}.d{2}.d{4}

Обе записи будут валидны. Но вторая читается чуть проще — не надо самому считать повторения, просто смотрим на цифру.

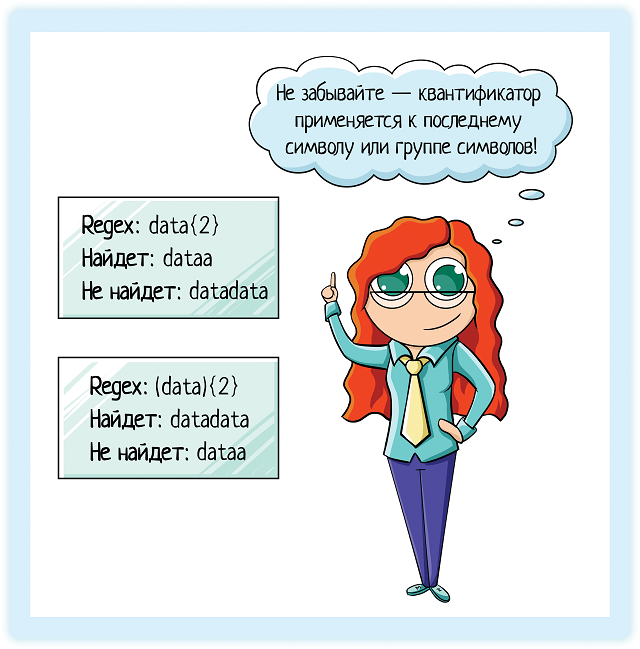

Не забывайте — квантификатор применяется к последнему символу!

Regex: data{2}

Найдет: dataa

Не найдет: datadata

Или группе символов, если они взяты в круглые скобки:

Regex: (data){2}

Найдет: datadata

Не найдет: dataa

Так как фигурные скобки используются в качестве указания количества повторений, то, если вы ищете именно фигурную скобку в тексте, ее надо экранировать:

Regex: x{3}

Найдет: x{3}

Иногда квантификатор находит не совсем то, что нам нужно.

Regex: <.*>

Ожидание:

<req>

<query>Ан</query>

<gender>FEMALE</gender>Реальность:

<req> <query>Ан</query> <gender>FEMALE</gender></req>Мы хотим найти все теги HTML или XML по отдельности, а регулярное выражение возвращает целую строку, внутри которой есть несколько тегов.

Напомню, что в разных реализациях регулярные выражения могут работать немного по разному. Это одно из отличий — в некоторых реализациях квантификаторам соответствует максимально длинная строка из возможных. Такие квантификаторы называют жадными.

Если мы понимаем, что нашли не то, что хотели, можно пойти двумя путями:

-

Учитывать символы, не соответствующие желаемому образцу

-

Определить квантификатор как нежадный (ленивый, англ. lazy) — большинство реализаций позволяют это сделать, добавив после него знак вопроса.

Как учитывать символы? Для примера с тегами можно написать такое регулярное выражение:

<[^>]*>

Оно ищет открывающий тег, внутри которого все, что угодно, кроме закрывающегося тега «>», и только потом тег закрывается. Так мы не даем захватить лишнее. Но учтите, использование ленивых квантификаторов может повлечь за собой обратную проблему — когда выражению соответствует слишком короткая, в частности, пустая строка.

|

Жадный |

Ленивый |

|

* |

*? |

|

+ |

+? |

|

{n,} |

{n,}? |

Есть еще и сверхжадная квантификация, также именуемая ревнивой. Но о ней почитайте в википедии =)

Позиция внутри строки

По умолчанию регулярные выражения ищут «по включению».

Regex: арка

Найдет:

арка

чарка

аркан

баварка

знахарка

Это не всегда то, что нам нужно. Иногда мы хотим найти конкретное слово.

Если мы ищем не одно слово, а некую строку, проблема решается в помощью пробелов:

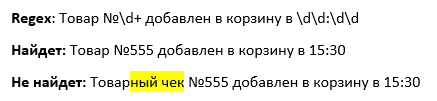

Regex: Товар №d+ добавлен в корзину в dd:dd

Найдет: Товар №555 добавлен в корзину в 15:30

Не найдет: Товарный чек №555 добавлен в корзину в 15:30

Или так:

Regex: .* арка .*

Найдет: Триумфальная арка была…

Не найдет: Знахарка сегодня…

А что, если у нас не пробел рядом с искомым словом? Это может быть знак препинания: «И вот перед нами арка.», или «…арка:».

Если мы ищем конкретное слово, то можно использовать метасимвол b, обозначающий границу слова. Если поставить метасимвол с обоих концов слова, мы найдем именно это слово:

Regex: bаркаb

Найдет:

арка

Не найдет:

чарка

аркан

баварка

знахарка

Можно ограничить только спереди — «найди все слова, которые начинаются на такое-то значение»:

Regex: bарка

Найдет:

арка

аркан

Не найдет:

чарка

баварка

знахарка

Можно ограничить только сзади — «найди все слова, которые заканчиваются на такое-то значение»:

Regex: аркаb

Найдет:

арка

чарка

баварка

знахарка

Не найдет:

аркан

Если использовать метасимвол B, он найдем нам НЕ-границу слова:

Regex: BакрB

Найдет:

закройка

Не найдет:

акр

акрил

Если мы хотим найти конкретную фразу, а не слово, то используем следующие спецсимволы:

^ — начало текста (строки)

$ — конец текста (строки)

Если использовать их, мы будем уверены, что в наш текст не закралось ничего лишнего:

Regex: ^Я нашел!$

Найдет:

Я нашел!

Не найдет:

Смотри! Я нашел!

Я нашел! Посмотри!

Итого метасимволы, обозначающие позицию строки:

|

Символ |

Значение |

|

b |

граница слова |

|

B |

Не граница слова |

|

^ |

начало текста (строки) |

|

$ |

конец текста (строки) |

Использование ссылки назад

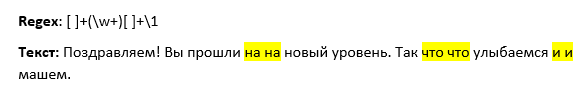

Допустим, при тестировании приложения вы обнаружили забавный баг в тексте — дублирование предлога «на»: «Поздравляем! Вы прошли на на новый уровень». А потом решили проверить, есть ли в коде еще такие ошибки.

Разработчик предоставил файлик со всеми текстами. Как найти повторы? С помощью ссылки назад. Когда мы берем что-то в круглые скобки внутри регулярного выражения, мы создаем группу. Каждой группе присваивается номер, по которому к ней можно обратиться.

Regex: [ ]+(w+)[ ]+1

Текст: Поздравляем! Вы прошли на на новый уровень. Так что что улыбаемся и и машем.

Разберемся, что означает это регулярное выражение:

[ ]+ → один или несколько пробелов, так мы ограничиваем слово. В принципе, тут можно заменить на метасимвол b.

(w+) → любой буквенный или цифровой символ, или знак подчеркивания. Квантификатор «+» означает, что символ должен идти минимум один раз. А то, что мы взяли все это выражение в круглые скобки, говорит о том, что это группа. Зачем она нужна, мы пока не знаем, ведь рядом с ней нет квантификатора. Значит, не для повторения. Но в любом случае, найденный символ или слово — это группа 1.

[ ]+ → снова один или несколько пробелов.

1 → повторение группы 1. Это и есть ссылка назад. Так она записывается в JavaScript-е.

Важно: синтаксис ссылок назад очень зависит от реализации регулярных выражений.

|

ЯП |

Как обозначается ссылка назад |

|

JavaScript vi |

|

|

Perl |

$ |

|

PHP |

$matches[1] |

|

Java Python |

group[1] |

|

C# |

match.Groups[1] |

|

Visual Basic .NET |

match.Groups(1) |

Для чего еще нужна ссылка назад? Например, можно проверить верстку HTML, правильно ли ее составили? Верно ли, что открывающийся тег равен закрывающемуся?

Напишите выражение, которое найдет правильно написанные теги:

<h2>Заголовок 2-ого уровня</h2>

<h3>Заголовок 3-ого уровня</h3>Но не найдет ошибки:

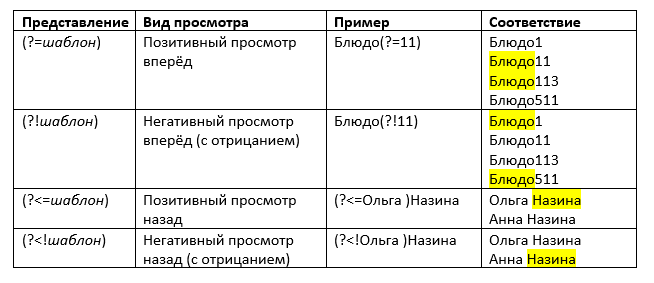

<h2>Заголовок 2-ого уровня</h3>Просмотр вперед и назад

Еще может возникнуть необходимость найти какое-то место в тексте, но не включая найденное слово в выборку. Для этого мы «просматриваем» окружающий текст.

|

Представление |

Вид просмотра |

Пример |

Соответствие |

|

(?=шаблон) |

Позитивный просмотр вперёд |

Блюдо(?=11) |

Блюдо11 Блюдо113

|

|

(?!шаблон) |

Негативный просмотр вперёд (с отрицанием) |

Блюдо(?!11) |

Блюдо1

Блюдо511 |

|

(?<=шаблон) |

Позитивный просмотр назад |

(?<=Ольга )Назина |

Ольга Назина

|

|

(?шаблон) |

Негативный просмотр назад (с отрицанием) |

(см ниже на рисунке) |

Анна Назина |

Замена

Важная функция регулярных выражений — не только найти текст, но и заменить его на другой текст! Простейший вариант замены — слово на слово:

RegEx: Ольга

Замена: Макар

Текст был: Привет, Ольга!

Текст стал: Привет, Макар!

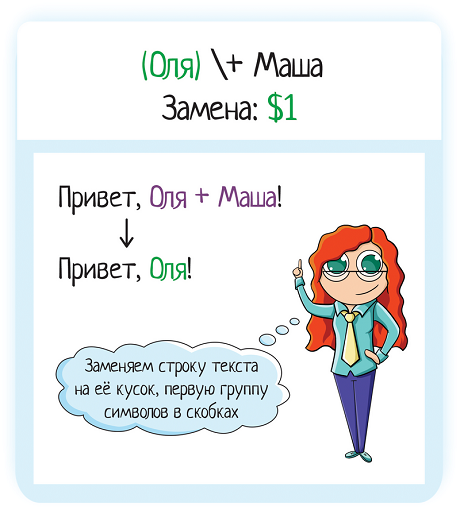

Но что, если у нас в исходном тексте может быть любое имя? Вот что пользователь ввел, то и сохранилось. А нам надо на Макара теперь заменить. Как сделать такую замену? Через знак доллара. Давайте разберемся с ним подробнее.

Знак доллара в замене — обращение к группе в поиске. Ставим знак доллара и номер группы. Группа — это то, что мы взяли в круглые скобки. Нумерация у групп начинается с 1.

RegEx: (Оля) + Маша

Замена: $1

Текст был: Оля + Маша

Текст стал: Оля

Мы искали фразу «Оля + Маша» (круглые скобки не экранированы, значит, в искомом тексте их быть не должно, это просто группа). А замнили ее на первую группу — то, что написано в первых круглых скобках, то есть текст «Оля».

Это работает и когда искомый текст находится внутри другого:

RegEx: (Оля) + Маша

Замена: $1

Текст был: Привет, Оля + Маша!

Текст стал: Привет, Оля!

Можно каждую часть текста взять в круглые скобки, а потом варьировать и менять местами:

RegEx: (Оля) + (Маша)

Замена: $2 — $1

Текст был: Оля + Маша

Текст стал: Маша — Оля

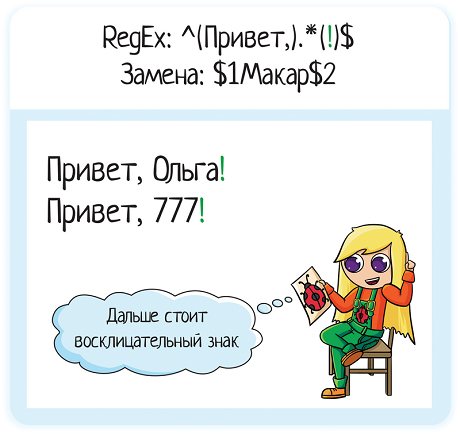

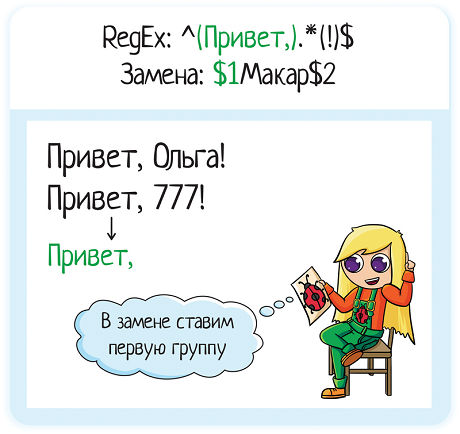

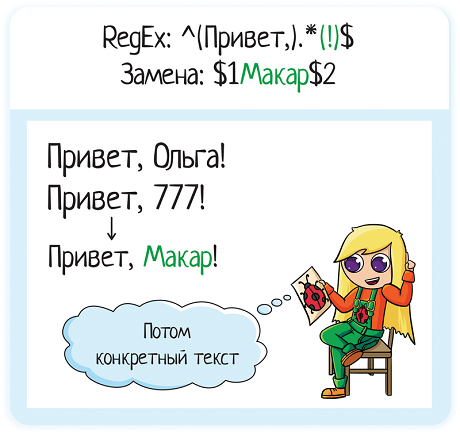

Теперь вернемся к нашей задаче — есть строка приветствия «Привет, кто-то там!», где может быть написано любое имя (даже просто числа вместо имени). Мы это имя хотим заменить на «Макар».

Нам надо оставить текст вокруг имени, поэтому берем его в скобки в регулярном выражении, составляя группы. И переиспользуем в замене:

RegEx: ^(Привет, ).*(!)$

Замена: $1Макар$2

Текст был (или или):

Привет, Ольга!

Привет, 777!

Текст стал:

Привет, Макар!

Давайте разберемся, как работает это регулярное выражение.

^ — начало строки.

Дальше скобка. Она не экранирована — значит, это группа. Группа 1. Поищем для нее закрывающую скобку и посмотрим, что входит в эту группу. Внутри группы текст «Привет, »

После группы идет выражение «.*» — ноль или больше повторений чего угодно. То есть вообще любой текст. Или пустота, она в регулярку тоже входит.

Потом снова открывающаяся скобка. Она не экранирована — ага, значит, это вторая группа. Что внутри? Внутри простой текст — «!».

И потом символ $ — конец строки.

Посмотрим, что у нас в замене.

$1 — значение группы 1. То есть текст «Привет, ».

Макар — просто текст. Обратите внимание, что мы или включает пробел после запятой в группу 1, или ставим его в замене после «$1», иначе на выходе получим «Привет,Макар».

$2 — значение группы 2, то есть текст «!»

Вот и всё!

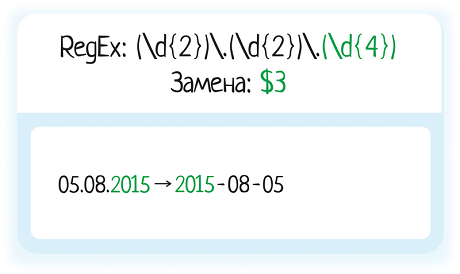

А что, если нам надо переформатировать даты? Есть даты в формате ДД.ММ.ГГГГ, а нам нужно поменять формат на ГГГГ-ММ-ДД.

Регулярное выражение для поиска у нас уже есть — «d{2}.d{2}.d{4}». Осталось понять, как написать замену. Посмотрим внимательно на ТЗ:

ДД.ММ.ГГГГ

↓

ГГГГ-ММ-ДД

По нему сразу понятно, что нам надо выделить три группы. Получается так: (d{2}).(d{2}).(d{4})

В результате у нас сначала идет год — это третья группа. Пишем: $3

Потом идет дефис, это просто текст: $3-

Потом идет месяц. Это вторая группа, то есть «$2». Получается: $3-$2

Потом снова дефис, просто текст: $3-$2-

И, наконец, день. Это первая группа, $1. Получается: $3-$2-$1

Вот и всё!

RegEx: (d{2}).(d{2}).(d{4})

Замена: $3-$2-$1

Текст был:

05.08.2015

01.01.1999

03.02.2000

Текст стал:

2015-08-05

1999-01-01

2000-02-03

Другой пример — я записываю в блокнот то, что успела сделать за цикл в 12 недель. Называется файлик «done», он очень мотивирует! Если просто вспоминать «что же я сделал?», вспоминается мало. А тут записал и любуешься списком.

Вот пример улучшалок по моему курсу для тестировщиков:

-

Сделала сообщения для бота — чтобы при выкладке новых тем писал их в чат

-

Фолкс — поправила статью «Расширенный поиск», убрала оттуда про пустой ввод при простом поиске, а то путал

-

Обновила кусочек про эффект золушки (переписывала под ютуб)

И таких набирается штук 10-25. За один цикл. А за год сколько? Ух! Вроде небольшие улучшения, а набирается прилично.

Так вот, когда цикл заканчивается, я пишу в блог о своих успехах. Чтобы вставить список в блог, мне надо удалить нумерацию — тогда я сделаю ее силами блоггера и это будет смотреться симпатичнее.

Удаляю с помощью регулярного выражения:

RegEx: d+. (.*)

Замена: $1

Текст был:

1. Раз

2. Два

Текст стал:

Раз

Два

Можно было бы и вручную. Но для списка больше 5 элементов это дико скучно и уныло. А так нажал одну кнопочку в блокноте — и готово!

Так что регулярные выражения могут помочь даже при написании статьи =)

Статьи и книги по теме

Книги

Регулярные выражения 10 минут на урок. Бен Форта — Очень рекомендую! Прям шикарная книга, где все просто, доступно, понятно. Стоит 100 рублей, а пользы море.

Статьи

Вики — https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Регулярные_выражения. Да, именно ее вы будете читать чаще всего. Я сама не помню наизусть все метасимволы. Поэтому, когда использую регулярки, гуглю их, википедия всегда в топе результатов. А сама статья хорошая, с табличками удобными.

Регулярные выражения для новичков — https://tproger.ru/articles/regexp-for-beginners/

Итого

Регулярные выражения — очень полезная вещь для тестировщика. Применений у них много, даже если вы не автоматизатор и не спешите им стать:

-

Найти все нужные файлы в папке.

-

Grep-нуть логи — отсечь все лишнее и найти только ту информацию, которая вам сейчас интересна.

-

Проверить по базе, нет ли явно некорректных записей — не остались ли тестовые данные в продакшене? Не присылает ли смежная система какую-то фигню вместо нормальных данных?

-

Проверить данные чужой системы, если она выгружает их в файл.

-

Выверить файлик текстов для сайта — нет ли там дублирования слов?

-

Подправить текст для статьи.

-

…

Если вы знаете, что в коде вашей программы есть регулярное выражение, вы можете его протестировать. Вы также можете использовать регулярки внутри ваших автотестов. Хотя тут стоит быть осторожным.

Не забывайте о шутке: «У разработчика была одна проблема и он стал решать ее с помощью регулярных выражений. Теперь у него две проблемы». Бывает и так, безусловно. Как и с любым другим кодом.

Поэтому, если вы пишете регулярку, обязательно ее протестируйте! Особенно, если вы ее пишете в паре с командой rm (удаление файлов в linux). Сначала проверьте, правильно ли отрабатывает поиск, а потом уже удаляйте то, что нашли.

Регулярное выражение может не найти то, что вы ожидали. Или найти что-то лишнее. Особенно если у вас идет цепочка регулярок. Думаете, это так легко — правильно написать регулярку? Попробуйте тогда решить задачку от Егора или вот эти кроссворды =)

PS — больше полезных статей ищите в моем блоге по метке «полезное». А полезные видео — на моем youtube-канале

A Regular Expression – or regex for short– is a syntax that allows you to match strings with specific patterns. Think of it as a suped-up text search shortcut, but a regular expression adds the ability to use quantifiers, pattern collections, special characters, and capture groups to create extremely advanced search patterns.

Regex can be used any time you need to query string-based data, such as:

- Analyzing command line output

- Parsing user input

- Examining server or program logs

- Handling text files with a consistent syntax, like a CSV

- Reading configuration files

- Searching and refactoring code

While doing all of these is theoretically possible without regex, when regexes hit the scene they act as a superpower for doing all of these tasks.

In this guide we’ll cover:

- What does a regex look like?

- How to read and write a regex

- What’s a «quantifier»?

- What’s a «pattern collection»?

- What’s a «regex token»?

- How to use a regex

- What’s a «regex flag»?

- What’s a «regex group»?

Download our Regex Cheat Sheet

What does a regex look like?

In its simplest form, a regex in usage might look something like this:

This screenshot is of the regex101 website. All future screenshots will utilize this website for visual reference.

In the «Test» example the letters test formed the search pattern, same as a simple search.

These regexes are not always so simple, however. Here’s a regex that matches 3 numbers, followed by a «-«, followed by 3 numbers, followed by another «-«, finally ended by 4 numbers.

You know, like a phone number:

^(?:d{3}-){2}d{4}$

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

This regex may look complicated, but two things to keep in mind:

- We’ll teach you how to read and write these in this article

- This is a fairly complex way of writing this regex.

In fact, most regexes can be written in multiple ways, just like other forms of programming. For example, the above can be rewritten into a longer but slightly more readable version:

^[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{3}-[0-9]{4}$

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Most languages provide a built-in method for searching and replacing strings using regex. However, each language may have a different set of syntaxes based on what the language dictates.

In this article, we’ll focus on the ECMAScript variant of Regex, which is used in JavaScript and shares a lot of commonalities with other languages’ implementations of regex as well.

How to read (and write) regexes

Quantifiers

Regex quantifiers check to see how many times you should search for a character.

Here is a list of all quantifiers:

-

a|b— Match either «a» or «b -

?— Zero or one -

+— one or more -

*— zero or more -

{N}— Exactly N number of times (where N is a number) -

{N,}— N or more number of times (where N is a number) -

{N,M}— Between N and M number of times (where N and M are numbers and N < M) -

*?— Zero or more, but stop after first match

For example, the following regex:

Hello|Goodbye

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Matches both the string «Hello» and «Goodbye».

Meanwhile:

Hey?

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Will track «y» zero to one time, so will match up with «He» and «Hey».

Alternatively:

Hello{1,3}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Will match «Hello», «Helloo», «Hellooo», but not «Helloooo», as it is looking for the letter «o» between 1 and 3 times.

These can even be combined with one another:

He?llo{2}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Here we’re looking for strings with zero-to-one instances of «e» and the letter «o» times 2, so this will match «Helloo» and «Hlloo».

Greedy matching

One of the regex quantifiers we touched on in the previous list was the + symbol. This symbol matches one or more characters. This means that:

Hi+

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Will match everything from «Hi» to «Hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii». This is because all quantifiers are considered «greedy» by default.

However, if you change it to be «lazy» using a question mark symbol (?) to the following, the behavior changes.

Hi+?

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Now, the i matcher will try to match as few times as possible. Since the + icon means «one or more», it will only match one «i». This means that if we input the string «Hiiiiiiiiiii», only «Hi» will be matched.

While this isn’t particularly useful on its own, when combined with broader matches like the the . symbol, it becomes extremely important as we’ll cover in the next section. The . symbol is used in regex to find «any character».

Now if you use:

H.*llo

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

You can match everything from «Hillo» to «Hello» to «Hellollollo».

However, what if you want to only match «Hello» from the final example?

Well, simply make the search lazy with a ? and it’ll work as we want:

H.*?llo

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Pattern collections

Pattern collections allow you to search for a collection of characters to match against. For example, using the following regex:

My favorite vowel is [aeiou]

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

You could match the following strings:

My favorite vowel is a

My favorite vowel is e

My favorite vowel is i

My favorite vowel is o

My favorite vowel is u

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

But nothing else.

Here’s a list of the most common pattern collections:

-

[A-Z]— Match any uppercase character from «A» to «Z» -

[a-z]— Match any lowercase character from «a» to «z» -

[0-9]— Match any number -

[asdf]— Match any character that’s either «a», «s», «d», or «f» -

[^asdf]— Match any character that’s not any of the following: «a», «s», «d», or «f»

You can even combine these together:

-

[0-9A-Z]— Match any character that’s either a number or a capital letter from «A» to «Z» -

[^a-z]— Match any non-lowercase letter

General tokens

Not every character is so easily identifiable. While keys like «a» to «z» make sense to match using regex, what about the newline character?

The «newline» character is the character that you input whenever you press «Enter» to add a new line.

-

.— Any character -

n— Newline character -

t— Tab character -

s— Any whitespace character (includingt,nand a few others) -

S— Any non-whitespace character -

w— Any word character (Uppercase and lowercase Latin alphabet, numbers 0-9, and_) -

W— Any non-word character (the inverse of thewtoken) -

b— Word boundary: The boundaries betweenwandW, but matches in-between characters -

B— Non-word boundary: The inverse ofb -

^— The start of a line -

$— The end of a line -

\— The literal character «»

So if you wanted to remove every character that starts a new word you could use something like the following regex:

s.

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

And replace the results with an empty string. Doing this, the following:

Hello world how are you

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Becomes:

Helloorldowreou

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Combining with collections

These tokens aren’t just useful on their own, though! Let’s say that we want to remove any uppercase letter or whitespace character. Sure, we could write

[A-Z]|s

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

But we can actually merge these together and place our s token into the collection:

[A-Zs]

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

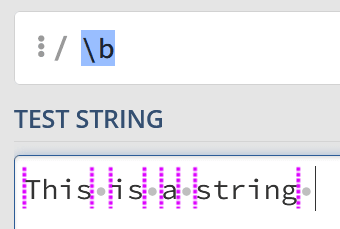

Word boundaries

In our list of tokens, we mentioned b to match word boundaries. I thought I’d take a second to explain how it acts a bit differently from others.

Given a string like «This is a string», you might expect the whitespace characters to be matched – however, this isn’t the case. Instead, it matches between the letters and the whitespace:

This can be tricky to get your head around, but it’s unusual to simply match against a word boundary. Instead, you might have something like the following to match full words:

bw+b

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

You can interpret that regex statement like this:

«A word boundary. Then, one or more ‘word’ characters. Finally, another word boundary».

Start and end line

Two more tokens that we touched on are ^ and $. These mark off the start of a line and end of a line, respectively.

So, if you want to find the first word, you might do something like this:

^w+

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

To match one or more «word» characters, but only immediately after the line starts. Remember, a «word» character is any character that’s an uppercase or lowercase Latin alphabet letters, numbers 0-9, and _.

Likewise, if you want to find the last word your regex might look something like this:

w+$

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

However, just because these tokens typically end a line doesn’t mean that they can’t have characters after them.

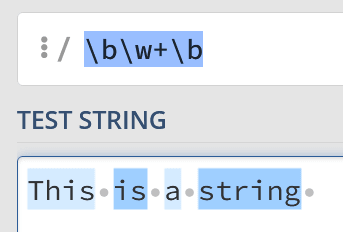

For example, what if we wanted to find every whitespace character between newlines to act as a basic JavaScript minifier?

Well, we can say «Find all whitespace characters after the end of a line» using the following regex:

$s+

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Character escaping

While tokens are super helpful, they can introduce some complexity when trying to match strings that actually contain tokens. For example, say you have the following string in a blog post:

"The newline character is 'n'"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Or want to find every instance of this blog post’s usage of the «n» string. Well, you can escape characters using . This means that your regex might look something like this:

\n

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

How to use a regex

Regular expressions aren’t simply useful for finding strings, however. You’re also able to use them in other methods to help modify or otherwise work with strings.

While many languages have similar methods, let’s use JavaScript as an example.

Creating and searching using regex

First, let’s look at how regex strings are constructed.

In JavaScript (along with many other languages), we place our regex inside of // blocks. The regex searching for a lowercase letter looks like this:

/[a-z]/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

This syntax then generates a RegExp object which we can use with built-in methods, like exec, to match against strings.

/[a-z]/.exec("a"); // Returns ["a"]

/[a-z]/.exec("0"); // Returns null

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

We can then use this truthiness to determine if a regex matched, like we’re doing in line #3 of this example:

Run the associated code sample in a code sandbox

We can also alternatively call a RegExp constructor with the string we want to convert into a regex:

const regex = new RegExp("[a-z]"); // Same as /[a-z]/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Replacing strings with regex

You can also use a regex to search and replace a file’s contents as well. Say you wanted to replace any greeting with a message of «goodbye». While you could do something like this:

function youSayHelloISayGoodbye(str) {

str = str.replace("Hello", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("Hi", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("Hey", "Goodbye"); str = str.replace("hello", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("hi", "Goodbye");

str = str.replace("hey", "Goodbye");

return str;

}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

There’s an easier alternative, using a regex:

function youSayHelloISayGoodbye(str) {

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/, "Goodbye");

return str;

}

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Run the associated code sample in a code sandbox

However, something you might notice is that if you run youSayHelloISayGoodbye with «Hello, Hi there»: it won’t match more than a single input:

If the regex /[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/ is used on the string «Hello, Hi there», it will only match «Hello» by default.

Here, we should expect to see both «Hello» and «Hi» matched, but we don’t.

This is because we need to utilize a Regex «flag» to match more than once.

Flags

A regex flag is a modifier to an existing regex. These flags are always appended after the last forward slash in a regex definition.

Here’s a shortlist of some of the flags available to you.

-

g— Global, match more than once -

m— Force $ and ^ to match each newline individually -

i— Make the regex case insensitive

This means that we could rewrite the following regex:

/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

To use the case insensitive flag instead:

/Hello|Hi|Hey/i

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

With this flag, this regex will now match:

Hello

HEY

Hi

HeLLo

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Or any other case-modified variant.

Global regex flag with string replacing

As we mentioned before, if you do a regex replace without any flags it will only replace the first result:

let str = "Hello, hi there!";

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/, "Goodbye");

console.log(str); // Will output "Goodbye, hi there"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

However, if you pass the global flag, you’ll match every instance of the greetings matched by the regex:

let str = "Hello, hi there!";

str = str.replace(/[Hh]ello|[Hh]i|[Hh]ey/g, "Goodbye");

console.log(str); // Will output "Goodbye, Goodbye there"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

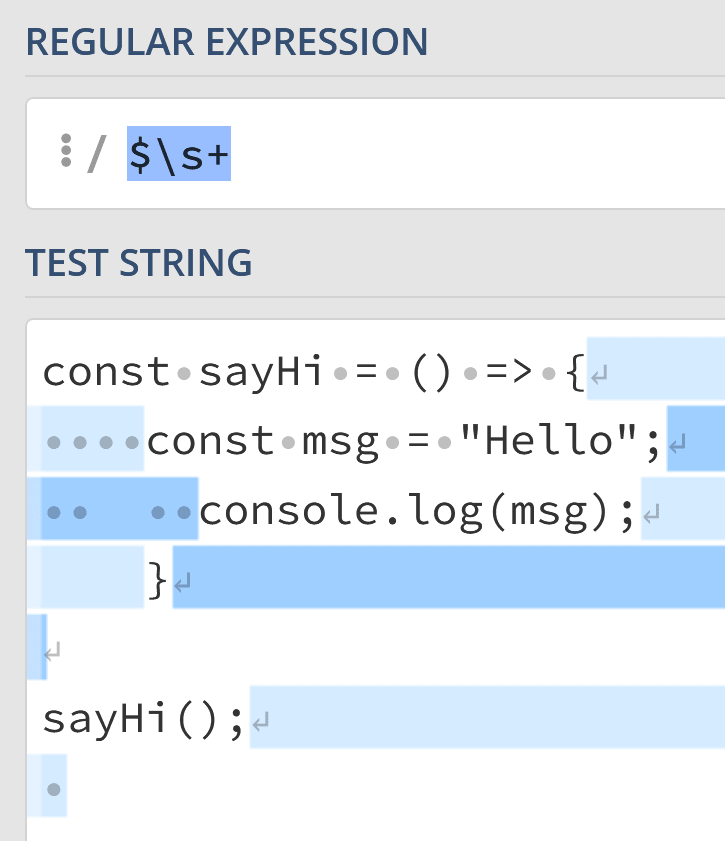

A note about JavaScript’s global flag

When using a global JavaScript regex, you might run into some strange behavior when running the exec command more than once.

In particular, if you run exec with a global regex, it will return null every other time:

JavaScript RegExp objects are stateful when they have the global or sticky flags set… They store a lastIndex from the previous match. Using this internally, exec() can be used to iterate over multiple matches in a string of text…

The exec command attempts to start looking through the lastIndex moving forward. Because lastIndex is set to the length of the string, it will attempt to match "" – an empty string – against your regex until it is reset by another exec command again. While this feature can be useful in specific niche circumstances, it’s often confusing for new users.

To solve this problem, we can simply assign lastIndex to 0 before running each exec command:

Groups

When searching with a regex, it can be helpful to search for more than one matched item at a time. This is where «groups» come into play. Groups allow you to search for more than a single item at a time.

Here, we can see matching against both Testing 123 and Tests 123 without duplicating the «123» matcher in the regex.

/(Testing|tests) 123/ig

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

-

(...)— Group matching any three characters -

(?:...)— Non-capturing group matching any three characters

The difference between these two typically comes up in the conversation when «replace» is part of the equation.

For example, using the regex above, we can use the following JavaScript to replace the text with «Testing 234» and «tests 234»:

const regex = /(Testing|tests) 123/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1 234');

console.log(str); // Testing 234nTests 234"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

We’re using $1 to refer to the first capture group, (Testing|tests). We can also match more than a single group, like both (Testing|tests) and (123):

const regex = /(Testing|tests) (123)/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1 #$2');

console.log(str); // Testing #123nTests #123"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

However, this is only true for capture groups. If we change:

/(Testing|tests) (123)/ig

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

To become:

/(?:Testing|tests) (123)/ig;

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Then there is only one captured group – (123) – and instead, the same code from above will output something different:

const regex = /(?:Testing|tests) (123)/ig;

let str = `

Testing 123

Tests 123

`;

str = str.replace(regex, '$1');

console.log(str); // "123n123"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Run the associated code sample in a code sandbox

Named capture groups

While capture groups are awesome, it can easily get confusing when there are more than a few capture groups. The difference between $3 and $5 isn’t always obvious at a glance.

To help solve for this problem, regexes have a concept called «named capture groups»

-

(?<name>...)— Named capture group called «name» matching any three characters

You can use them in a regex like so to create a group called «num» that matches three numbers:

/Testing (?<num>d{3})/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Then, you can use it in a replacement like so:

const regex = /Testing (?<num>d{3})/

let str = "Testing 123";

str = str.replace(regex, "Hello $<num>")

console.log(str); // "Hello 123"

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Named back reference

Sometimes it can be useful to reference a named capture group inside of a query itself. This is where «back references» can come into play.

-

k<name>Reference named capture group «name» in a search query

Say you want to match:

Hello there James. James, how are you doing?

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

But not:

Hello there James. Frank, how are you doing?

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

While you could write a regex that repeats the word «James» like the following:

/.*James. James,.*/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

A better alternative might look something like this:

/.*(?<name>James). k<name>,.*/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Now, instead of having two names hardcoded, you only have one.

Run the associated code sample in a code sandbox

Lookahead and lookbehind groups

Lookahead and behind groups are extremely powerful and often misunderstood.

There are four different types of lookahead and behinds:

-

(?!)— negative lookahead -

(?=)— positive lookahead -

(?<=)— positive lookbehind -

(?<!)— negative lookbehind

Lookahead works like it sounds like: It either looks to see that something is after the lookahead group or is not after the lookahead group, depending on if it’s positive or negative.

As such, using the negative lookahead like so:

/B(?!A)/

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Will allow you to match BC but not BA.

You can even combine these with ^ and $ tokens to try to match full strings. For example, the following regex will match any string that does not start with «Test»

/^(?!Test).*$/gm

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Likewise, we can switch this to a positive lookahead to enforce that our string must start with «Test»

/^(?=Test).*$/gm

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Putting it all together

Regexes are extremely powerful and can be used in a myriad of string manipulations. Knowing them can help you refactor codebases, script quick language changes, and more!

Let’s go back to our initial phone number regex and try to understand it again:

^(?:d{3}-){2}d{4}$

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Remember that this regex is looking to match phone numbers such as:

555-555-5555

Enter fullscreen mode

Exit fullscreen mode

Here this regex is:

- Using

^and$to define the start and end of a regex line. - Using a non-capturing group to find three digits then a dash

- Repeating this group twice, to match

555-555-

- Repeating this group twice, to match

- Finding the last 4 digits of the phone number

Hopefully, this article has been a helpful introduction to regexes for you. If you’d like to see quick definitions of useful regexes, check out our cheat sheet.

Download our Regex Cheat Sheet

Regex or regular expression is a pattern-matching tool. It allows you to search text in an advanced manner.

Regex is like CTRL+F on steroids.

For example, to find out all the emails or phone numbers from text, regex can get the job done.

The downside of the regex is it takes a while to memorize all the commands. One could say it takes 20 minutes to learn, but forever to master.

In this guide, you learn the basics of regex.

We are going to use the regex online playground in regexr.com. This is a super useful platform where you can easily practice your regex skills with useful examples.

Make sure to write down each regular expression you see in this guide to truly learn what you are doing.

Regex Tutorial

To make it as beneficial as possible, this tutorial is example-heavy. This means some of the regex concepts are introduced as part of the examples. Make sure you read everything!

Anyway, let’s get started with regex.

Regex and Flags

A regular expression (or regex) starts with forward slash (/) and ends with a forward slash.

The pattern matching happens in between the forward slashes.

For instance, let’s find the word “loud” in the text document.

As you can see, this works like CTRL + F.

Next, pay attention to the letter “g” in the above regex /loud/g.

The letter “g” means that the global flag is activated. In other words, you are treating the piece of example text as one long line of text.

Most of the time you are going to use the “g” flag only.

But it is good to understand there are other flags as well.

In the regexr online editor, you can find all the possible flags in the top right corner.

Now that you understand what regex is and what is the global flag, let’s see an example.

Let’s search for “at” in the piece of text:

As you can see, our regular expression found three matches of “at”.

Now, if you disable the “g” flag, it is only going to match the first occurrence of “at”.

Anyway, let’s switch the global flag back on.

So far using regex has been like using the good old CTRL+F.

However, the true power of the regular expressions shows up when we search for patterns instead of specific words.

To do this, we need to learn about the regex special characters that make pattern matching possible

Let’s start with the + charater.

The + Operator – Match One or More

Let’s search for character “s” in the example text.

This matches all “s” letters there are.

But what if you want to search for multiple “s” characters in a row?

In this case, you can use the + character after the letter “s”. This matches all the following “s” letters after the first one.

As a result, it now matches the double “s” in the text in addition to the singular “s”.

In short, the + operator matches one or more same characters in a row.

Next, let’s take a look at how optional matching works.

The ? Operator – Match Optional Characters

Optional matching is characterized by the question mark operator (?).

Optional matching means to match something that might follow.

For example, to match all letters “s” and every “s” followed by “t”, you can specify the letter “t” as an optional match using the question mark.

This matches:

- Each singular “s”

- Each combination of “st”.

Next up, let’s take a look at a special character that combines the + and ? characters.

The * Operator – Match Any Optional Characters

The star operator (*) means “match zero or more”.

Essentially, it is the combination of the + and the ? operators.

For example, let’s match with each letter “o” and any amount of letter “s” that follow.

This matches:

- All the singular “o” letters.

- All occurrences of “os”.

- All occurrences of “oss”.

As a matter of fact, this would match with “ossssssss” with any number of “s” letters as long as they are preceded by an “o”.

Next, let’s take a look at the wild card character.

The . Operator – Match Anything Except a New Line

In regex, the period is a special character that matches any singular character.

It acts as the wildcard.

The only character the period does not match is a line break.

For example, let’s match any character that comes before “at” in the text.

But how about matching with a dot then? The period (.) is a reserved special character, so it cannot be used.

This is where escaping is used.

The Operator – Escape a Special Character

If you are familiar with programming, you know what escaping means.

If not, escaping means to “invalidate” a reserved keyword or operator using a special character in front of its name.

As you saw in the previous example, the period character acts as a wildcard in regex. This means you cannot use it to match a dot in the text.

As you can see, /./g matches with each letter (and space) in the text, so it is not much of a help.

This is where escaping is useful.

In regex, you can escape any reserved character using a backslash ().

Anything followed by a backslash is going to be converted into a normal text character.

To match dots using regex, escape the period character with (.).

Now it matches all the dots in the text.

Let’s play with the example. To match any character that comes before a dot, add a period before the escaped period:

Now you understand how to match and escape characters in regex. Let’s move on to matching word characters using other special characters.

Match Different Types of Characters

You just learned how to use a backslash to escape a character.

However, the backslash has another important use case. Combining a backslash with some particular character forms an operator that can be used to match useful things.

As an example, an important special character in regex is w.

This matches all the word characters, that is, letters and digits but leaves out spaces.

For example, let’s match all the letters and digits in the text:

Another commonly used special operator is the space character s that matches any type of white space there is in the text.

For example, let’s match all the spaces in the text.

Of course, you can also match numeric characters only.

This happens via the d operator.

For instance, let’s match all digits in the text:

This matches with “2” and “0”.

These are the very basic special character operators there are in regex.

Next, you are going to learn how to invert these special characters.

Invert Special Characters

To invert a special character in regex, capitalize it.

- w matches any word character –> W matches with any non-word character

- s matches with any white space character –> S matches with any non-whitespace character.

- d matches with any digit –> D matches any non-digit character.

Examples:

Next, let’s take a look at how to match words with a specific length.

{} – Match Specific Length

Let’s say you want to capture all the words that are longer than 2 characters long.

Now, you cannot use + or * with the w character as it does not make sense.

Instead, use the curly braces {} by specifying how many characters to match.

There are three ways to use {}:

- {n}. Match n consecutive characters.

- {n,}. Match n character or more.

- {n,m}. Match between n and m in length.

Let’s examples of each.

Example 1. Match all sets of characters that are exactly 3 in length:

Example 2. Match consecutive strings that are longer than 3 characters:

Example 3. Match any set of characters that are between 3 and 5 characters in length:

Now that you know how to deal with quantities in regex, let’s talk about grouping.

[] – Groups and Ranges

In regex, you can use character grouping. This means you match with any character in the group.

One way to group characters is by using square brackets [].

For example, let’s match with any two letters where the last letter is “s” and the first letter is either “a” or “o”.

A really handy feature of using square brackets is you can specify a range. This lets you match any letter in the specified range.

To specify a range, use the dash with the following syntax. For example, [a-z] matches any letter from a to z.

For example, let’s match with any two-letter word that ends in “s” and starts with any character from a to z.

One thing you sometimes may want to do is to combine ranges.

This is also possible in regex.

For example, to find any two letters that end with “s” and start with any lowercase or uppercase letter, you can do:

/[a-zA-Z]s/g

Or if you want to match with any two letters that end with “s” and start with a number between 0 and 9, you can do:

/[0-9]s/g

Awesome.

Next, let’s take a look at another way to group characters in regex.

() Capturing Groups

In regex, capturing groups is a way to treat multiple characters as a single unit.

To create a capturing group, place the characters inside of the parenthesis.

For example, let’s match with words “The” or “the”, where the first letter is either lowercase t or uppercase T.

But why parenthesis? Let’s see what happens without them:

Now it matches with either any single character “t” or the word “The”.

This is the power of the capturing group. It treats the characters inside the parenthesis as a single unit.

Let’s see another example where we find any words that are 2-3 letters long and each letter in the word is either a,s,e,d.

As the last example of capturing, let’s match any words that repeat “os” two or three times in a row.

Here the “os” is not matched in the words “explosion” and “across”. This is because the “os” occurs only a single time. However, the “osososos” at the end has 3 x “os” so it gets matched.

Next up, let’s take a look at yet another special character, caret (^).

The ^ operator – Match the Beginning of a Line

The caret (^) character in regex means match with the beginning of the new line.

For example, let’s match with the letter “T” at the beginning of a text chapter.

Now, let’s see what happens when we try to match with the letter “N” at the beginning of the next line.

No matches!

But why is that? There is an “N” at the beginning of the second line.

This happens because our flag is set to “g” or “global”. We are treating the whole piece of text as a single line of text.