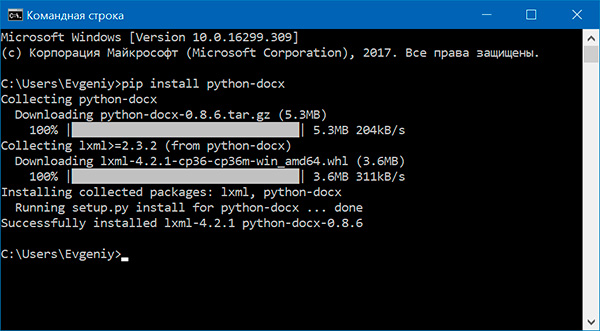

С помощью модуля python-docx можно создавать и изменять документы MS Word с расширением .docx. Чтобы установить этот модуль, выполняем команду

> pip install python-docx

При установке модуля надо вводить python-docx, а не docx (это другой модуль). В то же время при импортировании модуля python-docx следует использовать import docx, а не import python-docx.

Чтение документов MS Word

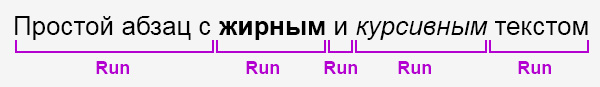

Файлы с расширением .docx обладают развитой внутренней структурой. В модуле python-docx эта структура представлена тремя различными типами данных. На самом верхнем уровне объект Document представляет собой весь документ. Объект Document содержит список объектов Paragraph, которые представляют собой абзацы документа. Каждый из абзацев содержит список, состоящий из одного или нескольких объектов Run, представляющих собой фрагменты текста с различными стилями форматирования.

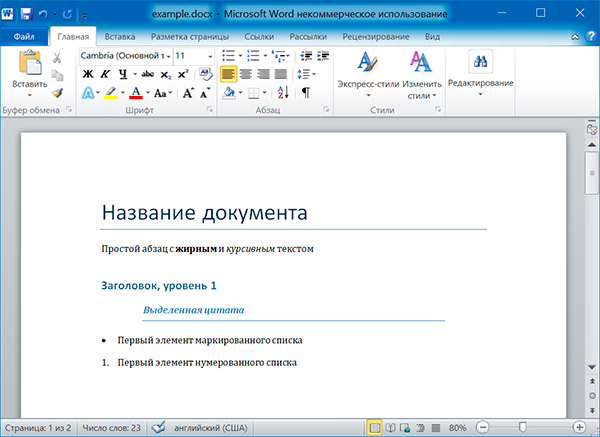

import docx doc = docx.Document('example.docx') # количество абзацев в документе print(len(doc.paragraphs)) # текст первого абзаца в документе print(doc.paragraphs[0].text) # текст второго абзаца в документе print(doc.paragraphs[1].text) # текст первого Run второго абзаца print(doc.paragraphs[1].runs[0].text)

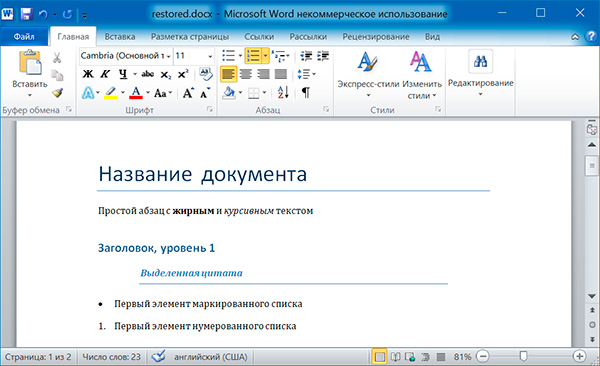

6 Название документа Простой абзац с жирным и курсивным текстом Простой абзац с

Получаем весь текст из документа:

text = [] for paragraph in doc.paragraphs: text.append(paragraph.text) print('n'.join(text))

Название документа Простой абзац с жирным и курсивным текстом Заголовок, уровень 1 Выделенная цитата Первый элемент маркированного списка Первый элемент нумерованного списка

Стилевое оформление

В документах MS Word применяются два типа стилей: стили абзацев, которые могут применяться к объектам Paragraph, стили символов, которые могут применяться к объектам Run. Как объектам Paragraph, так и объектам Run можно назначать стили, присваивая их атрибутам style значение в виде строки. Этой строкой должно быть имя стиля. Если для стиля задано значение None, то у объекта Paragraph или Run не будет связанного с ним стиля.

Стили абзацев

NormalBody TextBody Text 2Body Text 3CaptionHeading 1Heading 2Heading 3Heading 4Heading 5Heading 6Heading 7Heading 8Heading 9Intense QuoteListList 2List 3List BulletList Bullet 2List Bullet 3List ContinueList Continue 2List Continue 3List NumberList Number 2List Number 3List ParagraphMacro TextNo SpacingQuoteSubtitleTOCHeadingTitle

Стили символов

EmphasisStrongBook TitleDefault Paragraph FontIntense EmphasisSubtle EmphasisIntense ReferenceSubtle Reference

paragraph.style = 'Quote' run.style = 'Book Title'

Атрибуты объекта Run

Отдельные фрагменты текста, представленные объектами Run, могут подвергаться дополнительному форматированию с помощью атрибутов. Для каждого из этих атрибутов может быть задано одно из трех значений: True (атрибут активизирован), False (атрибут отключен) и None (применяется стиль, установленный для данного объекта Run).

bold— Полужирное начертаниеunderline— Подчеркнутый текстitalic— Курсивное начертаниеstrike— Зачеркнутый текст

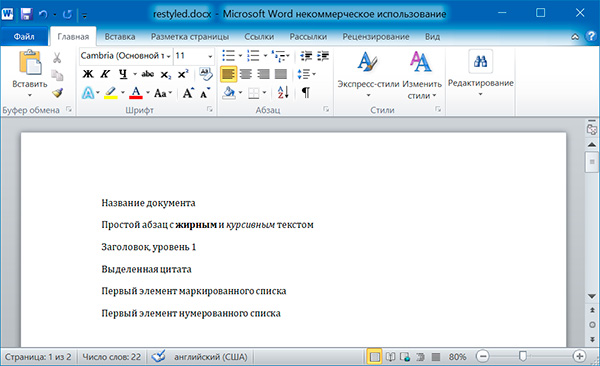

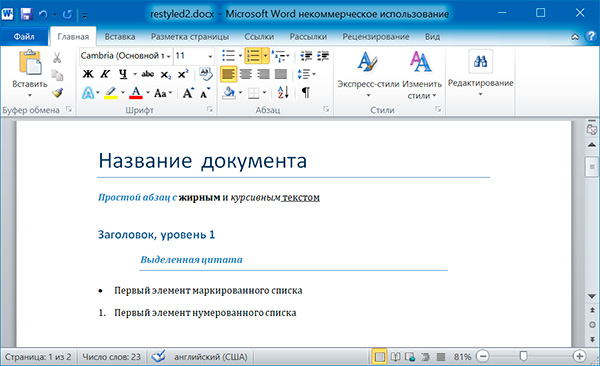

Изменим стили для всех параграфов нашего документа:

import docx doc = docx.Document('example.docx') # изменяем стили для всех параграфов for paragraph in doc.paragraphs: paragraph.style = 'Normal' doc.save('restyled.docx')

А теперь восстановим все как было:

import docx os.chdir('C:\example') doc1 = docx.Document('example.docx') doc2 = docx.Document('restyled.docx') # получаем из первого документа стили всех абзацев styles = [] for paragraph in doc1.paragraphs: styles.append(paragraph.style) # применяем стили ко всем абзацам второго документа for i in range(len(doc2.paragraphs)): doc2.paragraphs[i].style = styles[i] doc2.save('restored.docx')

Изменим форматирвание объектов Run второго абзаца:

import docx doc = docx.Document('example.docx') # добавляем стиль символов для runs[0] doc.paragraphs[1].runs[0].style = 'Intense Emphasis' # добавляем подчеркивание для runs[4] doc.paragraphs[1].runs[4].underline = True doc.save('restyled2.docx')

Запись докуменов MS Word

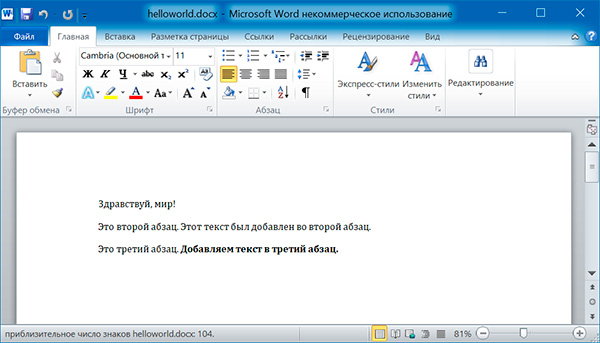

Добавление абзацев осуществляется вызовом метода add_paragraph() объекта Document. Для добавления текста в конец существующего абзаца, надо вызвать метод add_run() объекта Paragraph:

import docx doc = docx.Document() # добавляем первый параграф doc.add_paragraph('Здравствуй, мир!') # добавляем еще два параграфа par1 = doc.add_paragraph('Это второй абзац.') par2 = doc.add_paragraph('Это третий абзац.') # добавляем текст во второй параграф par1.add_run(' Этот текст был добавлен во второй абзац.') # добавляем текст в третий параграф par2.add_run(' Добавляем текст в третий абзац.').bold = True doc.save('helloworld.docx')

Оба метода, add_paragraph() и add_run() принимают необязательный второй аргумент, содержащий строку стиля, например:

doc.add_paragraph('Здравствуй, мир!', 'Title')

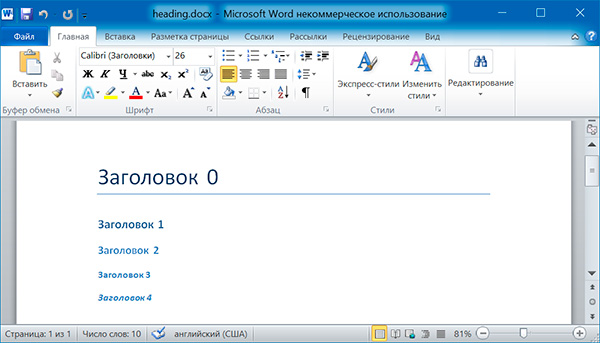

Добавление заголовков

Вызов метода add_heading() приводит к добавлению абзаца, отформатированного в соответствии с одним из возможных стилей заголовков:

doc.add_heading('Заголовок 0', 0) doc.add_heading('Заголовок 1', 1) doc.add_heading('Заголовок 2', 2) doc.add_heading('Заголовок 3', 3) doc.add_heading('Заголовок 4', 4)

Аргументами метода add_heading() являются строка текста и целое число от 0 до 4. Значению 0 соответствует стиль заголовка Title.

Добавление разрывов строк и страниц

Чтобы добавить разрыв строки (а не добавлять новый абзац), нужно вызвать метод add_break() объекта Run. Если же требуется добавить разрыв страницы, то методу add_break() надо передать значение docx.enum.text.WD_BREAK.PAGE в качестве единственного аргумента:

import docx doc = docx.Document() doc.add_paragraph('Это первая страница') doc.paragraphs[0].runs[0].add_break(docx.enum.text.WD_BREAK.PAGE) doc.add_paragraph('Это вторая страница') doc.save('pages.docx')

Добавление изображений

Метод add_picture() объекта Document позволяет добавлять изображения в конце документа. Например, добавим в конец документа изображение kitten.jpg шириной 10 сантиметров:

import docx doc = docx.Document() doc.add_paragraph('Это первый абзац') doc.add_picture('kitten.jpg', width = docx.shared.Cm(10)) doc.save('picture.docx')

Именованные аргументы width и height задают ширину и высоту изображения. Если их опустить, то значения этих аргументов будут определяться размерами самого изображения.

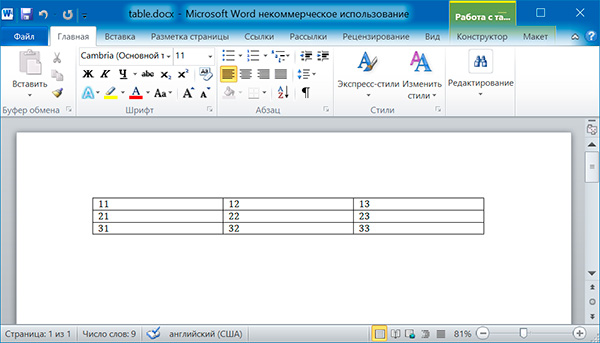

Добавление таблицы

import docx doc = docx.Document() # добавляем таблицу 3x3 table = doc.add_table(rows = 3, cols = 3) # применяем стиль для таблицы table.style = 'Table Grid' # заполняем таблицу данными for row in range(3): for col in range(3): # получаем ячейку таблицы cell = table.cell(row, col) # записываем в ячейку данные cell.text = str(row + 1) + str(col + 1) doc.save('table.docx')

import docx doc = docx.Document('table.docx') # получаем первую таблицу в документе table = doc.tables[0] # читаем данные из таблицы for row in table.rows: string = '' for cell in row.cells: string = string + cell.text + ' ' print(string)

11 12 13 21 22 23 31 32 33

Дополнительно

- Документация python-docx

Поиск:

MS • Python • Web-разработка • Word • Модуль

Каталог оборудования

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Производители

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Функциональные группы

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Модуль python-docx предназначен для создания и обновления файлов с расширением .docx — Microsoft Word. Этот модуль имеет одну зависимость: сторонний модуль lxml.

Модуль python-docx размещен на PyPI, поэтому установка относительно проста.

# создаем виртуальное окружение, если нет $ python3 -m venv .venv --prompt VirtualEnv # активируем виртуальное окружение $ source .venv/bin/activate # ставим модуль python-docx (VirtualEnv):~$ python3 -m pip install -U python-docx

Основы работы с файлами Microsoft Word на Python.

- Открытие/создание документа;

- Добавление заголовка документа;

- Добавление абзаца;

- Применение встроенного стиля в Microsoft Word к абзацу;

- Жирный, курсив и подчеркнутый текст в абзаце;

- Применение стилей Microsoft Word к символам текста (к прогону);

- Пользовательский стиль символов текста;

- Добавление разрыва страницы;

- Добавление картинки в документ;

- Чтение документов MS Word.

Открытие/создание документа.

Первое, что вам понадобится, это документ, над которым вы будете работать. Самый простой способ:

from docx import Document # создание документа document = Document() # открытие документа document = Document('/path/to/document.docx')

При этом создается пустой документ, основанный на «шаблоне» по умолчанию. Другими словами, происходит примерно то же самое, когда пользователь нажимает на иконку в Microsoft Word «Новый документ» с использованием встроенных значений по умолчанию.

При этом шрифт документа и его размер по умолчанию для всего документа можно задать следующим образом:

from docx import Document from docx.shared import Pt doc = Document() # задаем стиль текста по умолчанию style = doc.styles['Normal'] # название шрифта style.font.name = 'Arial' # размер шрифта style.font.size = Pt(14) document.add_paragraph('Текст документа')

Так же, можно открывать существующий документ Word и работать с ним при помощи модуля python-docx. Для этого, в конструктор класса Document() необходимо передать путь к существующему документу Microsoft Word.

Добавление заголовка документа.

В любом документе, основной текст делится на разделы, каждый из которых начинается с заголовка. Название таких разделов можно добавить методом Document.add_heading():

# без указания аргумента `level` # добавляется заголовок "Heading 1" head = document.add_heading('Основы работы с файлами Microsoft Word на Python.') from docx.enum.text import WD_ALIGN_PARAGRAPH # выравнивание посередине head.alignment = WD_ALIGN_PARAGRAPH.CENTER

По умолчанию, добавляется заголовок верхнего уровня, который отображается в Word как «Heading 1». Если нужен заголовок для подраздела, то просто указываем желаемый уровень в виде целого числа от 1 до 9:

document.add_heading('Добавление заголовка документа', level=2)

Если указать level=0, то будет добавлен текст с встроенным стилем титульной страницы. Такой стиль может быть полезен для заголовка относительно короткого документа без отдельной титульной страницы.

Так же, заголовки разделов можно добавлять методом document.add_paragraph().add_run(), с указанным размером шрифта.

Например:

from docx import Document from docx.shared import Pt doc = Document() # добавляем текст прогоном run = doc.add_paragraph().add_run('Заголовок, размером 24 pt.') # размер шрифта run.font.size = Pt(24) run.bold = True doc.save('test.docx')

Добавление абзаца.

Абзацы в Word имеют основополагающее значение. Они используются для добавления колонтитулов, основного текста, заголовков, элементов списков, картинок и т.д.

Смотрим самый простой способ добавить абзац/параграф:

p = document.add_paragraph('Абзацы в Word имеют основополагающее значение.')

Метод Document.add_paragraph() возвращает ссылку на только что добавленный абзац (объект Paragraph). Абзац добавляется в конец документа. Эту ссылку можно использовать в качестве своеобразного «курсора» и например, вставить новый абзац прямо над ним:

prior_p = p.insert_paragraph_before( 'Объект `paragraph` - это ссылка на только что добавленный абзац.')

Такое поведение позволяет вставить абзац в середину документа, это важно при изменении существующего документа, а не при его создании с нуля.

Ссылка на абзац, так же используется для его форматирования встроенными в MS Word стилями или для кастомного/пользовательского форматирования.

Пользовательское форматирование абзаца.

Форматирование абзацев происходит при помощи объекта ParagraphFormat.

Простой способ форматировать абзац/параграф:

from docx import Document from docx.shared import Mm from docx.enum.text import WD_ALIGN_PARAGRAPH doc = Document() # Добавляем абзац p = doc.add_paragraph('Новый абзац с отступами и красной строкой.') # выравниваем текст абзаца p.alignment = WD_ALIGN_PARAGRAPH.JUSTIFY # получаем объект форматирования fmt = p.paragraph_format # Форматируем: # добавляем отступ слева fmt.first_line_indent = Mm(15) # добавляем отступ до fmt.space_before = Mm(20) # добавляем отступ слева fmt.space_after = Mm(10) doc.add_paragraph('Новый абзац.') doc.add_paragraph('Еще новый абзац.') doc.save('test.docx')

Чтобы узнать, какие параметры абзаца еще можно настроить/изменить, смотрите материал «Объект ParagraphFormat»

Очень часто в коде, с возвращенной ссылкой (в данном случае p) ничего делать не надо, следовательно нет смысла ее присваивать переменной.

Применение встроенного стиля в Microsoft Word к абзацу.

Стиль абзаца — это набор правил форматирования, который заранее определен в Microsoft Word, и храниться в редакторе в качестве переменной. По сути, стиль позволяет сразу применить к абзацу целый набор параметров форматирования.

Можно применить стиль абзаца, прямо при его создании:

document.add_paragraph('Стиль абзаца как цитата', style='Intense Quote') document.add_paragraph('Стиль абзаца как список.', style='List Bullet')

В конкретном стиле 'List Bullet', абзац отображается в виде маркера. Также можно применить стиль позже. Две строки, в коде ниже, эквивалентны примеру выше:

document.add_paragraph('Другой стиль абзаца.').style = 'List Number' # Эквивалентно paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Другой стиль абзаца.') # применяем стиль позже paragraph.style = 'List Number'

Стиль указывается с использованием его имени, в этом примере имя стиля — 'List'. Как правило, имя стиля точно такое, как оно отображается в пользовательском интерфейсе Word.

Обратите внимание, что можно установить встроенный стиль прямо на результат document.add_paragraph(), без использования возвращаемого объекта paragraph

Жирный, курсив и подчеркнутый текст в абзаце.

Разберемся, что происходит внутри абзаца:

- Абзац содержит все форматирование на уровне блока, такое как — отступ, высота строки, табуляции и так далее.

- Форматирование на уровне символов, например полужирный и курсив, применяется на уровне прогона

paragraph.add_run(). Все содержимое абзаца должно находиться в пределах цикла, но их может быть больше одного. Таким образом, для абзаца с полужирным словом посередине требуется три прогона: обычный, полужирный — содержащий слово, и еще один нормальный для текста после него.

Когда создается абзац методом Document.add_paragraph(), то передаваемый текст добавляется за один прогон Run. Пустой абзац/параграф можно создать, вызвав этот метод без аргументов. В этом случае, наполнить абзац текстом можно с помощью метода Paragraph.add_run(). Метод абзаца .add_run() можно вызывать несколько раз, тем самым добавляя информацию в конец данного абзаца:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Абзац содержит форматирование ') paragraph.add_run('на уровне блока.')

В результате получается абзац, который выглядит так же, как абзац, созданный из одной строки. Если не смотреть на полученный XML, то не очевидно, где текст абзаца разбивается на части. Обратите внимание на конечный пробел в конце первой строки. Необходимо четко указывать, где появляются пробелы в начале и в конце прогона, иначе текст будет слитный (без пробелов). Они (пробелы) автоматически не вставляются между прогонами paragraph.add_run(). Метод paragraph.add_run() возвращает ссылку на объект прогона Run, которую можно использовать, если она нужна.

Объекты прогонов имеют следующие свойства, которые позволяют установить соответствующий стиль:

.bold: полужирный текст;.underline: подчеркнутый текст;.italic: курсивный (наклонный) текст;.strike: зачеркнутый текст.

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Абзац содержит ') paragraph.add_run('форматирование').bold = True paragraph.add_run(' на уровне блока.')

Получится текст, что то вроде этого: «Абзац содержит форматирование на уровне блока».

Обратите внимание, что можно установить полужирный или курсив прямо на результат paragraph.add_run(), без использования возвращаемого объекта прогона:

paragraph.add_run('форматирование').bold = True # или run = paragraph.add_run('форматирование') run.bold = True

Передавать текст в метод Document.add_paragraph() не обязательно. Это может упростить код, если строить абзац из прогонов:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph() paragraph.add_run('Абзац содержит ') paragraph.add_run('форматирование').bold = True paragraph.add_run(' на уровне блока.')

Пользовательское задание шрифта прогона.

from docx import Document from docx.shared import Pt, RGBColor # создание документа doc = Document() # добавляем текст прогоном run = doc.add_paragraph().add_run('Заголовок, размером 24 pt.') # название шрифта run.font.name = 'Arial' # размер шрифта run.font.size = Pt(24) # цвет текста run.font.color.rgb = RGBColor(0, 0, 255) # + жирный и подчеркнутый run.font.bold = True run.font.underline = True doc.save('test.docx')

Применение стилей Microsoft Word к символам текста (к прогону).

В дополнение к встроенным стилям абзаца, которые определяют группу параметров уровня абзаца, Microsoft Word имеет стили символов, которые определяют группу параметров уровня прогона paragraph.add_run(). Другими словами, можно думать о стиле текста как об указании шрифта, включая его имя, размер, цвет, полужирный, курсив и т. д.

Подобно стилям абзацев, стиль символов текста будет определен в документе, который открывается с помощью вызова Document() (см. Общие сведения о стилях).

Стиль символов можно указать при добавлении нового прогона:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Обычный текст, ') paragraph.add_run('текст с акцентом.', 'Emphasis')

Также можете применить стиль к прогону после его добавления. Этот код дает тот же результат, что и строки выше:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph() paragraph.add_run('Обычный текст, ') paragraph.add_run('текст с акцентом.').style = 'Emphasis'

Как и в случае со стилем абзаца, имя стиля текста такое, как оно отображается в пользовательском интерфейсе Word.

Пользовательский стиль символов текста.

from docx import Document from docx.shared import Pt, RGBColor # создание документа doc = Document() # задаем стиль текста по умолчанию style = doc.styles['Normal'] # название шрифта style.font.name = 'Calibri' # размер шрифта style.font.size = Pt(14) p = doc.add_paragraph('Пользовательское ') # добавляем текст прогоном run = p.add_run('форматирование ') # размер шрифта run.font.size = Pt(16) # курсив run.font.italic = True # добавляем еще текст прогоном run = p.add_run('символов текста.') # Форматируем: # название шрифта run.font.name = 'Arial' # размер шрифта run.font.size = Pt(18) # цвет текста run.font.color.rgb = RGBColor(255, 0, 0) # + жирный и подчеркнутый run.font.bold = True run.font.underline = True doc.save('test.docx')

Добавление разрыва страницы.

При создании документа, время от времени нужно, чтобы следующий текст выводился на отдельной странице, даже если последняя не заполнена. Жесткий разрыв страницы можно сделать следующим образом:

document.add_page_break()

Если вы обнаружите, что используете это очень часто, это, вероятно, знак того, что вы могли бы извлечь выгоду, лучше разбираясь в стилях абзацев. Одно свойство стиля абзаца, которое вы можете установить, — это разрыв страницы непосредственно перед каждым абзацем, имеющим этот стиль. Таким образом, вы можете установить заголовки определенного уровня, чтобы всегда начинать новую страницу. Подробнее о стилях позже. Они оказываются критически важными для получения максимальной отдачи от Word.

Жесткий разрыв страницы можно привязать к стилю абзаца, и затем применять его для определенных абзацев, которые должны начинаться с новой страницы. Так же можно установить жесткий разрыв на стиль заголовка определенного уровня, чтобы с него всегда начинать новую страницу. В общем, стили, оказываются критически важными для того, чтобы получить максимальную отдачу от модуля python-docx.

Добавление картинки в документ.

Microsoft Word позволяет разместить изображение в документе с помощью пункта меню «Вставить изображение«. Вот как это сделать при помощи модуля python-docx:

document.add_picture('/path/to/image-filename.png')

В этом примере используется путь, по которому файл изображения загружается из локальной файловой системы. В качестве пути можно использовать файловый объект, по сути, любой объект, который действует как открытый файл. Такое поведение может быть полезно, если изображение извлекается из базы данных или передается по сети.

Размер изображения.

По умолчанию, изображение добавляется с исходными размерами, что часто не устраивает пользователя. Собственный размер рассчитывается как px/dpi. Таким образом, изображение размером 300×300 пикселей с разрешением 300 точек на дюйм появляется в квадрате размером один дюйм. Проблема в том, что большинство изображений не содержат свойства dpi, и по умолчанию оно равно 72 dpi. Следовательно, то же изображение будет иметь одну сторону, размером 4,167 дюйма, что означает половину страницы.

Чтобы получить изображение нужного размера, необходимо указывать его ширину или высоту в удобных единицах измерения, например, в миллиметрах или сантиметрах:

from docx.shared import Mm document.add_picture('/path/to/image-filename.png', width=Mm(35))

Если указать только одну из сторон, то модуль python-docx использует его для вычисления правильно масштабированного значения другой стороны изображения. Таким образом сохраняется соотношение сторон и изображение не выглядит растянутым.

Классы Mm() и Cm() предназначены для того, чтобы можно было указывать размеры в удобных единицах. Внутри python-docx используются английские метрические единицы, 914400 дюймов. Так что, если просто указать размер, что-то вроде width=2, то получится очень маленькое изображение. Классы Mm() и Cm() импортируются из подпакета docx.shared. Эти классы можно использовать в арифметике, как если бы они были целыми числами. Так что выражение, width=Mm(38)/thing_count, работает нормально.

Чтение документов Microsoft Word.

В модуле python-docx, структура документа Microsoft Word представлена тремя различными типами данных. На самом верхнем уровне объект Document() представляет собой весь документ. Объект Document() содержит список объектов Paragraph(), которые представляют собой абзацы документа. Каждый из абзацев содержит список, состоящий из одного или нескольких объектов Run(), представляющих собой фрагменты текста с различными стилями форматирования.

Например:

>>> from docx import Document >>> doc = Document('/path/to/example.docx') # количество абзацев в документе >>> len(doc.paragraphs) # текст первого абзаца в документе >>> doc.paragraphs[0].text # текст второго абзаца в документе >>> doc.paragraphs[1].text # текст первого прогона второго абзаца >>> doc.paragraphs[1].runs[0].text

Используя следующий код, можно получить весь текст документа:

text = [] for paragraph in doc.paragraphs: text.append(paragraph.text) print('nn'.join(text))

А так можно получить стили всех параграфов:

styles = [] for paragraph in doc.paragraphs: styles.append(paragraph.style)

Использовать полученные стили можно следующим образом:

# изменим стиль 1 параграфа на # стиль взятый из 3 параграфа doc.paragraphs[0].style = styles[2]

In preparation for the job market, I started polishing my CV. I try to keep the

CV on my website as up-to-date as possible, but many recruiters and companies

prefer a single-page neat CV in a Microsoft Word document. I used to always make

my CV’s in LaTeX, but it seems Word is often preferred since it’s easier to

edit for third parties.

Keeping both a web, Word, and PDF version all up-to-date and easy to edit seemed

like an annoying task. I have plenty experience with automatically generating

PDF documents using LaTeX and Python, so I figured why should a Word document be

any different? Let’s dive into the world of editing Word documents in Python!

Fortunately there is a library for this: python-docx. It can be used to create

Word documents from scratch, but stylizing a document is a bit tricky. Instead,

its real power lies in editing pre-made documents. I went ahead and made a nice

looking CV in Word, and now let’s open this document in python-docx. A Word

document is stored in XML under the hoods, and there can be a complicated tree

structure to a document. However, we can create a document and use the

.paragraphs attribute for a complete list of all the paragraphs in the

document. Let’s take a paragraph, and print it’s text content.

from docx import Document

document = Document("resume.docx")

paragraph = document.paragraphs[0]

print(paragraph.text)

Turns out the first paragraph contains my name! Editing this text is very easy;

we just need to set a new value to the .text attribute. Let’s do this and safe

the document.

paragraph.text = "Willem Hendrik"

document.save("resume_edited.docx")

Below is a picture of the resulting change; it unfortunately seems like two

additional things happened when editing this paragraph: the font of the edited

paragraph changed, and the bar / text box on the right-hand side disappeared

completely!

This is no good, but to understand what happened to the text box we need to

dig into the XML of the document. We can turn the document into an XML file like

so:

document = Document("resume.docx")

with open('resume.xml', 'w') as f:

f.write(document._element.xml)

It seems the problem was that the text box on the right was nested inside an

other object, which is apparently not handled properly. This issue was easy to

fix by modifying the Word document. However, the right bar on the side consists

of 2 text boxes, and the top box with my contact information does disappear if

I change the first paragraph. But, it does not disappear if I change the

second paragraph; it only happens if I change paragraph 1 or 3 (and the latter

is empty). I tried inserting two paragraphs before this particular paragraph, or

changing the style of this particular paragraph, but the issue remains.

Looking at the XML the issue is clear: the text box element lies nested inside

this paragraph! It turned out to be a bit tricky to avoid this, so for now let

us then try changing the second paragraph, changing the word “resume” for

“curriculum vitae”.

document = Document("resume.docx")

paragraph = document.paragraphs[1]

print(paragraph.text)

paragraph.text = "Curriculum Vitae"

document.save("CV.docx")

If we do this there’s no problems with text boxes disappearing, but

unfortunately the style of this paragraph is still reset when we do this. Let’s

have a look at how the XML changes when we edit this paragraph. Ignoring

irrelevant information, before changing it looks like this:

<w:p>

<w:r>

<w:t>R</w:t>

</w:r>

<w:r>

<w:t>esume</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:p>

And afterwards it looks like this:

<w:p>

<w:r>

<w:t>Curriculum Vitae</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:p>

In Word, each paragraph (<p>) is split up in multiple runs (<r>). What we

see here is that originally the paragraph was two runs, and after modifying it,

it became a single run. However, it seems that in both cases the style

information is exactly the same, so I don’t understand why the style changes

after modification. In this case if I retype the word ‘Resume’ in the original

word document, this paragraph become a single run, but still the style changes

after editing, and I still don’t see why this happens when looking at the XML.

Looking at the source code of python-docx I noticed that when we call

paragraph.text = ..., what happens is that the contents of the paragraph get

deleted, and then a new run is added with the desired text. It is not clear to

me at where exactly the style information is stored, but either way there is a

simple workaround to what we’re trying to do: we can simply modify the text of

the first run in the paragraph, rather than clearing the entire paragraph and

adding a new one. This in fact also works for editing the first paragraph,

where before we had problems with disappearing text boxes:

document = Document("resume.docx")

with open('resume.xml', 'w') as f:

f.write(document._element.xml)

# Change 'Rik Voorhaar' for 'Willem Hendrik Voorhaar'

paragraph = document.paragraphs[0]

run = paragraph.runs[1]

run.text = 'Willem Hendrik Voorhaar'

# Change 'Resume' for 'Curriculum Vitae'

paragraph = document.paragraphs[1]

run = paragraph.runs[0]

run.text = 'Curriculum Vitae'

document.save('CV.docx')

Doing this changes the text, but leaves all the style information the

same. Alright, now we now how to edit text. It’s more tricky than one might

expect, but it does work!

Dealing with text boxes

Let’s say that next we want to edit the text box on the right-hand side of the

document, and add a skill to our list of skills. We’ve been diving into the

inner workings of Word documents, so it’s fair to say we know how to use

Microsoft Word, so let’s add the skill “Microsoft Word” to the list.

To do this we first want to figure out in which paragraph this information is

stored. We can do this by going through all the paragraphs in the document and

looking for the text “Skills”.

import re

pattern = re.compile("Skills")

for p in document.paragraphs:

if pattern.search(p.text):

print("Found the paragraph!")

break

else:

print("Did not find the paragraph :(")

Did not find the paragraph :(

Seems like there is unfortunately no matching paragraph! This is because the

paragraph we want is inside a text box, and modifying text boxes is not supported

in python-docx. This is a known issue, but instead of giving up I decided to

add support for modifying text boxes to python-docx myself! It turned out not to

be too difficult to implement, despite my limited knowledge of both the package

and the inner structure of Word documents.

The first step is understanding how text boxes are encoded in the XML. It turns

out that the structure is something like this:

<mc:AlternateContent>

<mc:Choice Requires="wps">

<w:drawing>

<wp:anchor>

<a:graphics>

<a:graphicData>

<wps:txbx>

<w:txbxContent>

...

<w:txbxContent>

</wps:txbx>

</a:graphicData>

</a:graphics>

</wp:anchor>

</w:drawing>

</mc:Choice>

<mc:Fallback>

<w:pict>

<v:textbox>

<w:txbxContent>

...

<w:txbxContent>

</v:textbox>

</w:pict>

</mc:Fallback>

</mc:AlternateContent>

The insides of the two <w:txbxContent> elements are exactly identical. The

information is stored twice probably for legacy reasons. A quick Google reveals

that wps is an XML namespace introduced in Office 2010, and WPS is short for

Word Processing Shape. The textbox is therefore stored twice to maintain

backwards compatibility with older Word versions. Not sure many people still use

Office 2006… Either way, this means that if we want to update the contents of

the textbox, we need to do it in two places.

Next we need to figure out how to manipulate these word objects. My idea is to

create a TextBox class, that is associated to an <mc:AlternateContent>

element, and which ensures that both <w:txbxContent> elements are always

updated at the same time. First we make a class encoding a <w:txbxContent>

element. For this we can build on the BlockItemContainer class already

implemented in python-docx. Mixing in this class gives automatic support for

manipulating paragraphs inside of the container.

class TextBoxContent(BlockItemContainer)

Given an <mc:AlternateContent> object, we can access the two <w:txbxContent>

elements using the following XPath specifications:

XPATH_CHOICE = "./mc:Choice/w:drawing/wp:anchor/a:graphic/a:graphicData//wps:txbx/w:txbxContent"

XPATH_FALLBACK = "./mc:Fallback/w:pict//v:textbox/w:txbxContent"

Then making a rudimentary TextBox class is very simple. We base it on the

ElementProxy class in python-docx. This class is meant for storing and

manipulating the children of an XML element.

class TextBox(ElementProxy):

"""Implements texboxes. Requires an `<mc:AlternateContent>` element."""

def __init__(self, element, parent):

super(TextBox, self).__init__(element, parent)

try:

(tbox1,) = element.xpath(XPATH_CHOICE)

(tbox2,) = element.xpath(XPATH_FALLBACK)

except ValueError as err:

raise ValueError(

"This element is not a text box; it should contain precisely two

``<w:txbxContent>`` objects"

)

self.tbox1 = TextBoxContent(tbox1, self)

self.tbox2 = TextBoxContent(tbox2, self)

So far this is just good for storing the text box, we still need some code to

actually manipulate it. It would also be great if we have a way to find all the

text boxes in a document. This is as simple as finding all the

<mc:AlternateContent> elements with precisely two <w:txbxContent> elements.

We can use the following function:

def find_textboxes(element, parent):

"""

List all text box objects in the document.

Looks for all ``<mc:AlternateContent>`` elements, and selects those

which contain a text box.

"""

alt_cont_elems = element.xpath(".//mc:AlternateContent")

text_boxes = []

for elem in alt_cont_elems:

tbox1 = elem.xpath(XPATH_CHOICE)

tbox2 = elem.xpath(XPATH_FALLBACK)

if len(tbox1) == 1 and len(tbox2) == 1:

text_boxes.append(TextBox(elem, parent))

return text_boxes

We then update the Document class with a new textboxes attribute:

@property

def textboxes(self):

"""

List all text box objects in the document.

"""

return find_textboxes(self._element, self)

Now let’s test this out:

document = Document("resume.docx")

document.textboxes

[<docx.oxml.textbox.TextBox at 0x7faf395c3bc0>,

<docx.oxml.textbox.TextBox at 0x7faf395c3100>]

Now to manipulate the “Skills” section as we initially wanted, we first find the

right paragraph. Since the two <w:txbxContent> objects have the same

paragraphs, we need to find which number of paragraph contains the text, and

in which textbox:

import re

def find_paragraph(pattern):

for textbox in document.textboxes:

for i,p in enumerate(textbox.paragraphs):

if pattern.search(p.text):

return textbox,i

pattern = re.compile("Skills")

textbox, i = find_paragraph(pattern)

print(textbox.paragraphs[i].text)

Now to insert a new skill, we need to create a new paragraph with the text

“Microsoft Word”. For this we can find the paragraph right after, and this

paragraphs insert_paragraph_before method with appropriate text and style

information. The paragraph in question is the one containing the word

“Research”. I want to copy the style of this paragraph to the new paragraph, but

for some reason the style information is empty for this paragraph. However, I

know that the style of this paragraph should be the 'Skillsentries', so I can

just use that directly.

style = document.styles['Skillsentries']

pattern = re.compile("Research")

textbox,i = find_paragraph(pattern)

p1 = textbox.tbox1.paragraphs[i]

p2 = textbox.tbox2.paragraphs[i]

for p in (p1,p2):

p.insert_paragraph_before("Microsoft Word", p.style)

document.save("CV.docx")

When now opening the Word document, we see the item “Microsoft Word” in my list

of skills, with the right style and everything. I did cheat a little; I needed

to make some additional technical changes to the code for this all to work, but

the details are not super important. If you want to use this feature, you can

use my fork of python-docx. My

solution is still a little hacky, so I don’t think it will be added to the main

repository, but it does work fine for my purposes.

Conclusion

In summary, we can use Python to edit word documents. However the

python-docx package is not fully mature, and using it for editing

highly-stylized word documents is a bit painful (but possible!). It is however

quite easy to extend with new functionality, in case you do need to do this. On

the other hand, there is quite extensive functionality in Visual Basic to edit

word documents, and the whole Word API is built around Visual Basic.

While I now have all the tools available to automatically update my CV using

Python, I will actually refrain from doing it. It is a lot of work to set up

properly, and needs active maintenance ever time I would want to change the

styling of my CV. Probably it’s a better idea to just manually edit it every

time I need to. Automatization isn’t always worth it. But I wouldn’t be

surprised if this new found skill will be useful at some point in the future for

me.

Recent blog posts

My thesis in a nutshell

February 26, 2023

17 minute read

Read this blog post if you’re curious what I worked on during my PhD!

GMRES: or how to do fast linear algebra

March 10, 2022

16 minute read

Linear least-squares system pop up everywhere, and there are many fast way to solve them. We’ll be looking at one such way: GMRES.

Blind Deconvolution #2: Image Priors

April 9, 2021

10 minute read

In order to automatically sharpen images, we need to first understand how a computer can judge how ‘natural’ an image looks.

Время на прочтение

2 мин

Количество просмотров 70K

Исполняем обязанности по получению сведений о своих бенефициарных владельцах

Небольшая вводная

Начиная с 21 декабря 2016 года вступили изменения в ФЗ РФ «О противодействии легализации (отмыванию) доходов, полученных преступным путем, и финансированию терроризма», касательно обязанности юридического лица по раскрытию информации о своих бенефициарных владельцах. В связи с этим, многие компании направляют запросы по цепочке владения с целью выяснения своих бенефициарных владельцев. Кто-то формирует запросы на бумаге, кто-то рассылает электронные письма.

На наш взгляд, надлежащим доказательством исполнения обязанности «знай своего бенефициарного владельца» является наличие письма на бумаге с отметкой об отправке/вручении. Данные письма в идеале должны готовиться не реже одного раза в год. Если в ведении юриста находится всего несколько компаний, то составление писем не составляет особого труда. Но, если компаний больше 3-х десятков, составление писем превращается в уничтожающую позитив рутину. Дело усугубляется тем, что реквизиты писем постоянно меняются: подписанты увольняются, компании перерегистрируются, меняя адреса. Все это надо учитывать. Как здесь могут помочь навыки программирования на python?

Очень просто — хорошо бы иметь программу, которая сама будет подставлять в письма необходимые реквизиты. В том числе формировать сами письма, не заставляя создавать документ за документом вручную. Попробуем.

Структура письма в word. Модуль python docxtpl

Перед написанием кода программы посмотрим как должен выглядеть шаблон письма, в который мы будем помещать наши данные.

Текст письма от общества своему участнику/акционеру будет примерно следующим:

Напишем простую программу, которая заполнит для начала одно поле в нашем шаблоне, чтобы понять принцип работы.

Для начала в самом шаблоне письма Word вместо одного из полей, например, подписанта поставим переменную. Данная переменная должна быть на либо на англ. языке, либо на русском, но в одно слово.Также переменная должна быть обязательно заключена в двойные фигурные скобки. Выглядеть это будет примерно так:

Сама программа будет иметь следующий вид:

from docxtpl import DocxTemplate

doc = DocxTemplate("шаблон.docx")

context = { 'director' : "И.И.Иванов"}

doc.render(context)

doc.save("шаблон-final.docx")

Вначале мы импортируем модуль для работы с документами формата Word. Далее мы открываем шаблон, и в поле директор, которое бы обозначили ранее в самом шаблоне, вносим ФИО директора. В конце документ сохраняется под новым именем.

Таким образом, чтобы заполнить все поля в файле-шаблоне Word нам для начала необходимо определить все поля ввода в самом шаблоне скобками {} вместе с переменными и потом написать программу. Код будет примерно следующим:

from docxtpl import DocxTemplate

doc = DocxTemplate("шаблон.docx")

context = { 'emitent' : 'ООО Ромашка', 'address1' : 'г. Москва, ул. Долгоруковская, д. 0', 'участник': 'ООО Участник', 'адрес_участника': 'г. Москва, ул. Полевая, д. 0', 'director': 'И.И. Иванов'}

doc.render(context)

doc.save("шаблон-final.docx")

На выходе при исполнении программы мы получим готовый заполненный документ.

Скачать готовый шаблон Word можно здесь.

Getting started with |docx| is easy. Let’s walk through the basics.

Opening a document

First thing you’ll need is a document to work on. The easiest way is this:

from docx import Document document = Document()

This opens up a blank document based on the default «template», pretty much

what you get when you start a new document in Word using the built-in

defaults. You can open and work on an existing Word document using |docx|,

but we’ll keep things simple for the moment.

Adding a paragraph

Paragraphs are fundamental in Word. They’re used for body text, but also for

headings and list items like bullets.

Here’s the simplest way to add one:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.')

This method returns a reference to a paragraph, newly added paragraph at the

end of the document. The new paragraph reference is assigned to paragraph

in this case, but I’ll be leaving that out in the following examples unless

I have a need for it. In your code, often times you won’t be doing anything

with the item after you’ve added it, so there’s not a lot of sense in keep

a reference to it hanging around.

It’s also possible to use one paragraph as a «cursor» and insert a new

paragraph directly above it:

prior_paragraph = paragraph.insert_paragraph_before('Lorem ipsum')

This allows a paragraph to be inserted in the middle of a document, something

that’s often important when modifying an existing document rather than

generating one from scratch.

Adding a heading

In anything but the shortest document, body text is divided into sections, each

of which starts with a heading. Here’s how to add one:

document.add_heading('The REAL meaning of the universe')

By default, this adds a top-level heading, what appears in Word as ‘Heading 1’.

When you want a heading for a sub-section, just specify the level you want as

an integer between 1 and 9:

document.add_heading('The role of dolphins', level=2)

If you specify a level of 0, a «Title» paragraph is added. This can be handy to

start a relatively short document that doesn’t have a separate title page.

Adding a page break

Every once in a while you want the text that comes next to go on a separate

page, even if the one you’re on isn’t full. A «hard» page break gets this

done:

document.add_page_break()

If you find yourself using this very often, it’s probably a sign you could

benefit by better understanding paragraph styles. One paragraph style property

you can set is to break a page immediately before each paragraph having that

style. So you might set your headings of a certain level to always start a new

page. More on styles later. They turn out to be critically important for really

getting the most out of Word.

Adding a table

One frequently encounters content that lends itself to tabular presentation,

lined up in neat rows and columns. Word does a pretty good job at this. Here’s

how to add a table:

table = document.add_table(rows=2, cols=2)

Tables have several properties and methods you’ll need in order to populate

them. Accessing individual cells is probably a good place to start. As

a baseline, you can always access a cell by its row and column indicies:

cell = table.cell(0, 1)

This gives you the right-hand cell in the top row of the table we just created.

Note that row and column indicies are zero-based, just like in list access.

Once you have a cell, you can put something in it:

cell.text = 'parrot, possibly dead'

Frequently it’s easier to access a row of cells at a time, for example when

populating a table of variable length from a data source. The .rows

property of a table provides access to individual rows, each of which has a

.cells property. The .cells property on both Row and Column

supports indexed access, like a list:

row = table.rows[1] row.cells[0].text = 'Foo bar to you.' row.cells[1].text = 'And a hearty foo bar to you too sir!'

The .rows and .columns collections on a table are iterable, so you

can use them directly in a for loop. Same with the .cells sequences

on a row or column:

for row in table.rows:

for cell in row.cells:

print(cell.text)

If you want a count of the rows or columns in the table, just use len() on

the sequence:

row_count = len(table.rows) col_count = len(table.columns)

You can also add rows to a table incrementally like so:

row = table.add_row()

This can be very handy for the variable length table scenario we mentioned

above:

# get table data -------------

items = (

(7, '1024', 'Plush kittens'),

(3, '2042', 'Furbees'),

(1, '1288', 'French Poodle Collars, Deluxe'),

)

# add table ------------------

table = document.add_table(1, 3)

# populate header row --------

heading_cells = table.rows[0].cells

heading_cells[0].text = 'Qty'

heading_cells[1].text = 'SKU'

heading_cells[2].text = 'Description'

# add a data row for each item

for item in items:

cells = table.add_row().cells

cells[0].text = str(item.qty)

cells[1].text = item.sku

cells[2].text = item.desc

The same works for columns, although I’ve yet to see a use case for it.

Word has a set of pre-formatted table styles you can pick from its table style

gallery. You can apply one of those to the table like this:

table.style = 'LightShading-Accent1'

The style name is formed by removing all the spaces from the table style name.

You can find the table style name by hovering your mouse over its thumbnail in

Word’s table style gallery.

Adding a picture

Word lets you place an image in a document using the Insert > Photo > Picture menu item. Here’s how to do it in |docx|:

from file...

document.add_picture('image-filename.png')

This example uses a path, which loads the image file from the local filesystem.

You can also use a file-like object, essentially any object that acts like an

open file. This might be handy if you’re retrieving your image from a database

or over a network and don’t want to get the filesystem involved.

Image size

By default, the added image appears at native size. This is often bigger than

you want. Native size is calculated as pixels / dpi. So a 300×300 pixel

image having 300 dpi resolution appears in a one inch square. The problem is

most images don’t contain a dpi property and it defaults to 72 dpi. This would

make the same image appear 4.167 inches on a side, somewhere around half the

page.

To get the image the size you want, you can specify either its width or height

in convenient units, like inches or centimeters:

from docx.shared import Inches

document.add_picture('image-filename.png', width=Inches(1.0))

You’re free to specify both width and height, but usually you wouldn’t want to.

If you specify only one, |docx| uses it to calculate the properly scaled value

of the other. This way the aspect ratio is preserved and your picture doesn’t

look stretched.

The Inches and Cm classes are provided to let you specify measurements

in handy units. Internally, |docx| uses English Metric Units, 914400 to the

inch. So if you forget and just put something like width=2 you’ll get an

extremely small image :). You’ll need to import them from the docx.shared

sub-package. You can use them in arithmetic just like they were an integer,

which in fact they are. So an expression like width = Inches(3) works just fine.

/ thing_count

Applying a paragraph style

If you don’t know what a Word paragraph style is you should definitely check it

out. Basically it allows you to apply a whole set of formatting options to

a paragraph at once. It’s a lot like CSS styles if you know what those are.

You can apply a paragraph style right when you create a paragraph:

document.add_paragraph('Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.', style='ListBullet')

This particular style causes the paragraph to appear as a bullet, a very handy

thing. You can also apply a style afterward. These two lines are equivalent to

the one above:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.')

paragraph.style = 'List Bullet'

The style is specified using its style name, ‘List Bullet’ in this example.

Generally, the style name is exactly as it appears in the Word user interface

(UI).

Applying bold and italic

In order to understand how bold and italic work, you need to understand

a little about what goes on inside a paragraph. The short version is this:

- A paragraph holds all the block-level formatting, like indentation, line

height, tabs, and so forth. - Character-level formatting, such as bold and italic, are applied at the

run level. All content within a paragraph must be within a run, but there

can be more than one. So a paragraph with a bold word in the middle would

need three runs, a normal one, a bold one containing the word, and another

normal one for the text after.

When you add a paragraph by providing text to the .add_paragraph() method,

it gets put into a single run. You can add more using the .add_run() method

on the paragraph:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Lorem ipsum ')

paragraph.add_run('dolor sit amet.')

This produces a paragraph that looks just like one created from a single

string. It’s not apparent where paragraph text is broken into runs unless you

look at the XML. Note the trailing space at the end of the first string. You

need to be explicit about where spaces appear at the beginning and end of

a run. They’re not automatically inserted between runs. Expect to be caught by

that one a few times :).

|Run| objects have both a .bold and .italic property that allows you to

set their value for a run:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Lorem ipsum ')

run = paragraph.add_run('dolor')

run.bold = True

paragraph.add_run(' sit amet.')

which produces text that looks like this: ‘Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.’

Note that you can set bold or italic right on the result of .add_run() if

you don’t need it for anything else:

paragraph.add_run('dolor').bold = True

# is equivalent to:

run = paragraph.add_run('dolor')

run.bold = True

# except you don't have a reference to `run` afterward

It’s not necessary to provide text to the .add_paragraph() method. This can

make your code simpler if you’re building the paragraph up from runs anyway:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph()

paragraph.add_run('Lorem ipsum ')

paragraph.add_run('dolor').bold = True

paragraph.add_run(' sit amet.')

Applying a character style

In addition to paragraph styles, which specify a group of paragraph-level

settings, Word has character styles which specify a group of run-level

settings. In general you can think of a character style as specifying a font,

including its typeface, size, color, bold, italic, etc.

Like paragraph styles, a character style must already be defined in the

document you open with the Document() call (see

:ref:`understanding_styles`).

A character style can be specified when adding a new run:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Normal text, ')

paragraph.add_run('text with emphasis.', 'Emphasis')

You can also apply a style to a run after it is created. This code produces

the same result as the lines above:

paragraph = document.add_paragraph('Normal text, ')

run = paragraph.add_run('text with emphasis.')

run.style = 'Emphasis'

As with a paragraph style, the style name is as it appears in the Word UI.