Close reading is the careful reading of a text, often multiple times, to obtain a deeper understanding of its meaning, and should be part of a well-balanced curriculum in language arts and the content areas*.

Close reading is used to examine specific aspects of a short text, such as key details, author’s point of view, word meaning, or making inferences. This post shares a close reading strategy to help students determine word meaning from any text that they read.

Strategy Steps

Use this version when the text provides definition/context to determine word meaning.

- Display the text using a projector or document camera. Have students reread the text independently or in pairs.

- Select key words from the text that need to be defined and display those words for students.

- Ask students to highlight the sentences where those words are found and that give their definitions.

- Ask, “Why do you think the author put the words ______ and _______ in italics (or bold)?” Discuss how the text features help the reader determine the meanings of these words and phrases.

Use this version when outside resources need to be used to determine word meaning.

- Display the text using a projector or document camera. Have students review their initial impression notes in the margins. Ask if anyone noted any words that were either confusing or interesting in the text. Highlight these words on the projected text.

- Have students reread the text independently or in pairs.

- Allow students time to use dictionaries, context clues, and other resources to determine the meanings of unknown or confusing words and phrases.

- Have students share their definitions and then agree on a definition for each word as a class. Record the definition on the displayed text and have students do the same.

Download sample close reading lessons that use this strategy. Download Now

Author bio

Jessica Hathaway

Jessica Hathaway, M.S.Ed., earned her B.A. in Psychology from Pomona College and her M.S. in Education from Northwestern University, with a concentration in literacy. She has conducted classroom-based research on the integration of different learning modalities into literacy instruction and spent several years working in the Los Angeles Unified School District teaching early elementary, instructing art enrichment classes, and mentoring novice teachers. Currently, Jessica authors educational resources for teachers and students.

Privacy Policy and Cookies

By browsing our website, you accept cookies used to improve and personalize our services and

marketing.

To find out more, read our Privacy Policy page.

Great Idea: Reading for Meaning

What is reading for meaning?

Reading involves both decoding and reading for meaning. Many EAL learners are highly literate in one or more languages, but some may not have had the opportunity to learn to read in the language of their home. In some cultures, reading is seen as a specialist skill, not one that every individual can and should acquire. In others it is the skill of decoding that is particularly admired, and understanding what you are reading is seen as less important.

Learners who can read in a language that uses the same alphabet as English will find it easier to learn to decode in English than those who can read another script, but both groups bring with them an understanding that print carries meaning.

Decoding should not be an end in itself, and practising reading ‘nonsense words’ such as vap or ulf is unhelpful because EAL learners cannot be expected to know whether or not these words have meaning in English. So a focus on reading for meaning is crucial and should be supported by visuals (pictures, diagrams, mime etc.) as much as possible.

Examples of activities

Reading for meaning is important at all levels of English language proficiency from New to English to Fluent. It is critical in all areas of the curriculum. Here are some examples of activities that promote reading for meaning at word, phrase or sentence and text level:

1. Word level:

Flashcards and word mats are great for reading at word or short phrase level. Many of the resources on this website contain these, together with suggestions as to how to use them.

2. Sentence level:

To encourage reading for meaning at sentence level a useful strategy is to set sequencing tasks to be done either individually or in a pair or small group. This can be cutting up sentence cards and asking learners to reassemble the sentence, or using sentence flashcards that can be sequenced to form a text.

3. Text level:

To encourage reading for meaning at text level activities done before reading are very helpful. Give learners a clear idea what to expect from the text and give them plenty of time to engage with it. Use any visual clues there are and provide additional visual material if necessary. For books, allow time to look at the cover of a book, identify the author and illustrator, read the blurb and make predictions about the story. The more learners know about the contents of the text the easier they will find it to understand when they read it. EAL learners also need support in reading between the lines: they need to see that text may imply more than it actually says.

4. DARTs:

DARTs (Directed Activities Related to Text) are activities which lead learners to interact with text in ways which enhance understanding. Many of the resources on this website contain DARTs activities, for example Holes by Louis Sachar: DARTs. In this resource there is a true / false activity, a sorting task on past and present events and an activity where learners are asked to match the main characters feelings to events in the story.

5. Group reading:

Reading aloud in pairs or threes works well with fiction, taking it in turns to read a page, paragraph or even a sentence. Modelling of good reading with expression by a teacher or other adult is very important and will encourage learners to do the same. Make available high-quality texts (picture books / short novels / poetry / manga / illustrated non-fiction) that will encourage EAL learners to read for pleasure.

How reading for meaning works

In schools, reading tends to be seen as an individual activity, and the older the learners, the more likely this is to be the case, but there are other possibilities. Reading as a collaborative activity is very beneficial to EAL learners. This can be done in a number of ways:

- Read aloud to learners

- Read in pairs in class

- Paired reading with an older learner

Answering questions, whether orally or in writing, is the traditional way of checking comprehension. However, some learners become skilled in answering the question without fully understanding the text. It is often more effective to ask EAL learners to demonstrate their understanding in other ways, for example:

- Ask learners to say whether discrete sentences (taken from the text, or paraphrases) are true or false

- Give learners a number of false sentences, and ask them to reword the sentences to make them true

- Give learners a copy of the text which has been edited to contain errors. Ask the learners to identify the errors and correct them.

All of the above can be done as collaborative activities, in pairs or groups, as well as by learners working individually.

Top tip: Make available high-quality texts (picture books / short novels / poetry / manga / illustrated non-fiction) that will encourage EAL learners to read for pleasure, and allow them to choose reading material that appeals to them.

Why is reading for meaning a Great Idea for EAL learners?

Research into reading, e.g. Holden 2004, indicates that it provides a gateway into personal, social and economic development. It has been suggested that literacy will become increasingly important as the 21st century progresses (Moore et al 1999). There is also research evidence that competent readers are better at acquiring new vocabulary through their reading, for example Holly and Joseph (2018).

A focus on reading for meaning rather than simply decoding is important for EAL learners. Research suggests that EAL learners tend to have greater phonological awareness than their peers and often demonstrate good decoding skills in English, but score less well in reading comprehension measures (Murphy and Franco 2016). This suggests that attention to phonics should not take place in isolation from activities that promote vocabulary building, meaning-making and comprehension (Edwards 2013). Reading builds on oral language competence and so learning to read requires making links between the language and the writing system (Abbot, 2013). This means that reading and writing tasks should focus on words and phrases that the learner already knows in English.

Reading in groups and pairs is a way of exposing EAL learners to peers who can provide good models of reading with expression, and this can increase enjoyment of reading. Krashen (1993) also found that being given a choice of reading matter increases the motivation of learners and leads to greater language and literacy development.

References

Abbot, M. 2013, What makes reading difficult for EAL students? NALDIC Quarterly Vol. 13 No. 1 pp5-14.

Edwards, V., 2013, The politics of phonics, implications for bilingual learners, NALDIC Quarterly Vol. 13 No. 1 pp15-20.

Holden, J., 2004, Creative Reading. London: Demos.

Joseph, H. and Nation, K., 2018, Examining incidental word learning during reading in children: the role or context. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166. 190-211.

Krashen, S., 1993, The Power of Reading, Eaglewood, Col.,: Libraries Unlimited Inc.

Moore, D.W., Bean, T.W., Birdyshaw, D. and Rycik, J., 1999, Adolescent Literacy: A position statement, International Reading Association.

Murphy, V. and Franco, D., 2016, Phonics instruction and children with English as an Additional Language, EAL Journal Autumn 2016, 38-42.

Reading is an exercise for your mind. It is a way of turning a text into meaning and then understanding it to interact with it through a message. To make your reading more effective, you may make a sense of what you read. Often you unconsciously lose the meaning in between, which causes a sense within yourself to make use of effective reading strategies. Here are a few effective reading strategies for you:

Based on Critical Reading Strategies

Critical reading of a text means to read from your own perspective, apart from what the writer has painted it for you. So, this rational way of reading can be considered as the beginning of true learning and personal development. Here are a few effective critical reading strategies for you:

1. Previewing

It means to attain pre-knowledge about the text, before starting to read it, which may save you time. It may be done by researching:

- Who is the author?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Who is the audience?

Get FREE Students Apps (Check it Now)

2. Contextualizing

Contextualizing or researching the text involves exploring the historical, cultural and biographical frame of references of the text.

From a wider perspective, it means that you should try to differentiate between your own understandings of the text with that of some other person’s, as an understanding of a text may vary from time to time and place to place.

3. Inquisition

It is all about questioning the content of the text to understand, comprehend and clarify what you are reading, which will help you to build interest with the text. This can be made easier by framing 3 sets of questions:

- Subject-Text(represents subject or text undergoing discussion)

- Personal reality(represents your own experience)

- External reality(represents the concepts of larger society)

4. Synopsizing

This is an effective reading strategy, which is also known by other names like outlining or summarizing. This method is to identify the central theme of the text and then to paraphrase it in your own words. The key to synopsizing is the ability to make out a difference between the main idea, supporting idea and the examples.

5. Co-relating with related reading

This is a mode of reading based on the factor of comparison, by examining the differences or similarities within the texts to figure it out in a better sense.

6. Assessing an argument

This involves testing the logicality along with the credibility and emotional impact of the text.

You can analyze an argument using these 4 steps:

- You should thoroughly go through the instructions and arguments

- Then spot out the assumptions and claims of the argument

- Now you should think of counter explanations and examples of the arguments.

- Finally, ask yourself about the changes that can be made.

Also Read: 21 Inspirational Movies Every Student Must Watch

7. Activating Prior-Knowledge

This is a method of reading a text with some pre-conceived notions in mind. This will let you get a better understanding of the text.

Academic Reading Strategies

Being a student, one of the biggest challenges you may face is to complete reading the academics. So if you know the different academic reading strategies, you will enjoy reading. Here are a few of the academic reading strategies:

8. Scanning

Scanning is a specific reading skill that does not focus on every nook and corner of the text.

You do scanning while reading a schedule about the screen timings of a movie or a cricket match or while going through the weather map in the newspaper.

To make the scanning process more helpful, you can use the following strategies:

- Find out the keyword from the question itself

- You should scan separately for each question

- When you re-locate the keyword, go through the surrounding texts too.

9. Skimming

This is a technique almost similar to that of scanning, but the aim is to collect the main points of the text from a wider perspective. It’s just like skimming milk, where after skimming, we skim the finest part of the milk. Likewise, when you skim a text, you will learn the main points in the text, thereby; you can save your time.

Good skimmers do not skim everything. You can do it wisely by slowing down your pace of reading at places like:

- Introductory and concluding paragraphs

- Topic sentences

- Unfamiliar words

10. Intensive Reading

When compared to the other two techniques, this is relatively slower and a time consuming one.

This involves sentence to sentence reading rather than word to word reading.

You should read every sentence in detail from the beginning to the end and thereby, analyze the complete meaning of the text.

If you put too much pressure on vocabulary, then it would be a burden rather than a blessing.

Based on Cognitive Reading Strategies

This is a mental procedure for achieving a goal. In simpler words, cognitive strategies for learning will help you in reading effectively by just thinking and then solving the problem. There are different methods of cognitive reading like:

11. Inferring

This is a way of extracting the meaning of the text by bringing together the things that are written or unwritten in the text along with your prior knowledge about the subject. You have to read between the lines and understand the secondary meaning of the text.

12. Monitoring or Clarifying

It is a reading comprehension strategy where the reader constantly enquires whether the text makes any sense to them and enforcing strategic methods to make the text easier. You can understand it better by using these few methods:

- Re-read the paragraph

- Search for unfamiliar words

- Reconstruct information into an image, concept or map

13. Visualizing and Organizing

It is a method that stimulates the readers to create a vague image in their mind, about the content they read. It’s like a person making movies or videos in their minds out of the prior knowledge, imagination and the content of the text. This will stimulate your imagination and enhance your involvement with the text and thus improve your mental imagery

14. Searching and Selecting

This is a way of searching sources of the text to choose the required piece of information to answer the questions, solve problems, and clear the wrong interpretations or to gather information.

15. Questioning

This is a mode of reading which is almost similar to that of the above-mentioned method-‘Inquisition’, which involves questioning. This will engage you with self-questioning, by which you will gain an answer with the help of your peers and teachers.

Some questions which will help you read effectively are:

- Why did that character behave so?

- What led to such an issue?

- What next?

Based on Fluency Reading Strategies

Whether you read it with hatred, stumbled words or without expression, your comprehension will be affected. Better fluency leads to better understanding. So some of the fluency reading strategies are discussed below:

16. Reading it aloud

This can be done with the help of a peer or a teacher, where, you should read it aloud, and your peer should correct the mistakes regarding your fluency in language and correctness in sentences.

This will be quite a good way to determine your initial level of reading.

Also Read: 13 Ways to Deal With Exam Stress

17. Choral Reading

This is a reading strategy that aims at the repetition of sentences. In this, you should copy what the teacher says, just as we did in smaller classes. This will sharpen your ability to decode words and increase vocabulary.

18. Partner Reading

This is a kind of peer learning where strong readers are paired with weaker ones so that the latter can learn from the former. This will allow you to share your strengths. This is also known as Peer-assisted learning.

19. Cloze Reading

This is a technique of effective reading where the instructor will read the passage aloud and will deliberately skip certain words from the passage, and further you will be asked to read the missing words together. This will improve your analytical as well as critical thinking ability.

20. SQ3R

Following an SQ3R is a well-known strategy for reading. It can be applied to a whole range of reading purposes as it is flexible and takes into account the need to change reading speeds.

SQ3R acronym stands for:

- Survey

- Question

- Read

- Recall

- Review

Reading is a skill that can be considered as a lifelong achievement. So by using wisely the effective reading strategies, you can improve your lifelong skill, which may often save your time.

Get FREE Students Apps (Check it Now)

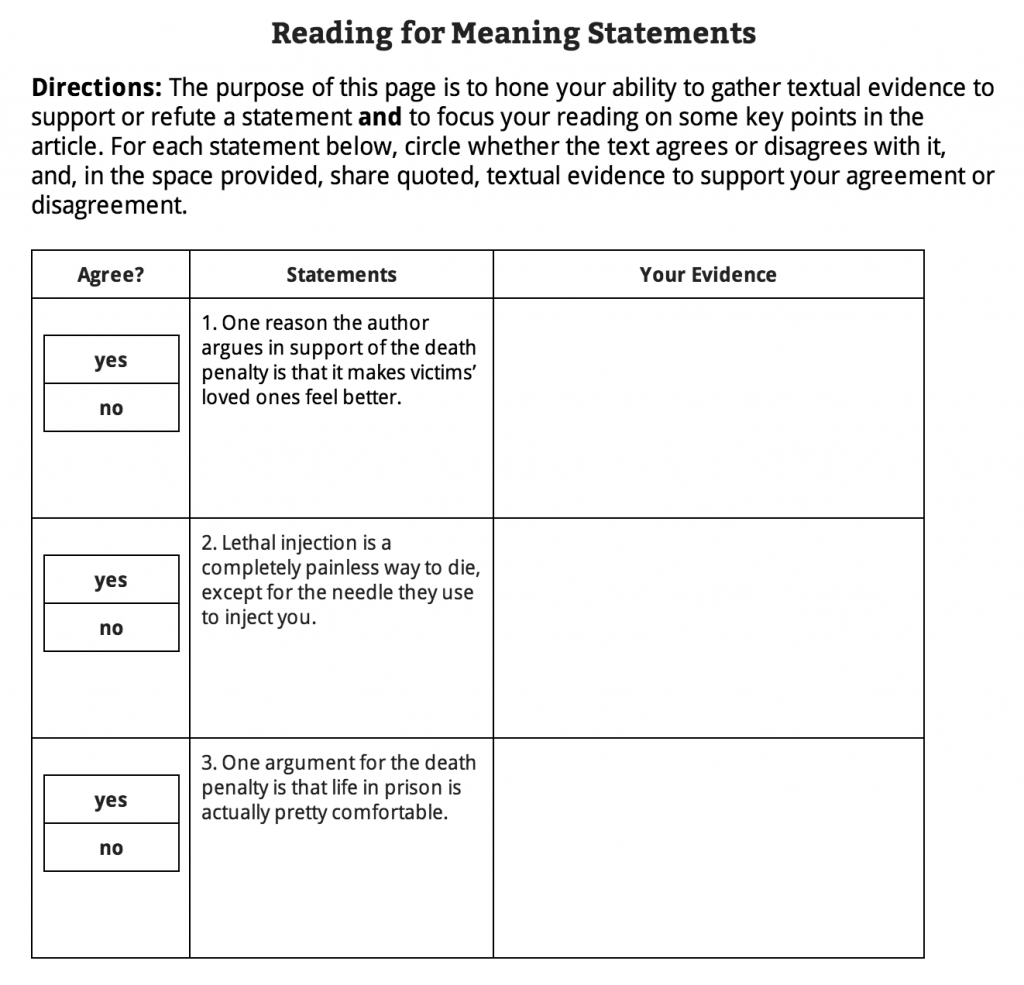

If you used any of the articles of the week I posted this year (just to be clear, Kelly Gallagher is the originator of the Article of the Week strategy), you definitely noticed some changes to the format. I’ve written elsewhere about why I use Graff/Birkenstein’s They Say/I Say strategy with AoWs (here and here), but I haven’t said much about the “Reading for Meaning” (RFM) statements I now include on many articles (see screen shot below).

In this post, I’ll be explaining what’s up with those.

Reading for Meaning, brought to me by The Core Six

- Reading for Meaning — gives practice in the basic skills readers use when grappling with complex texts.

- Compare & Contrast — “teaches students to conduct a thorough comparative analysis” (p. 3)

- Inductive Learning — “helps students find patterns and structures built into content through… analyzing specifics to form generalizations” (p. 3)

- Circle of Knowledge — “a strategic framework for planning and conducting classroom discussions that engage all students in deeper thinking and thoughtful communication” (p. 3)

- Write to Learn — “helps teachers integrate writing into daily instruction and develop students’ writing skills in key text types associated with college and career readiness” (p. 3)

- Vocabulary’s CODE — “a strategic approach to vocab instruction that improves students’ ability to retain and use crucial vocab terms” (p. 3)

I implemented pieces of all of the above strategies during this past school year, so again, if you’d like further treatment of any of them by a layman, let me know in the comments, and if you’d prefer to hear it straight from the pros, grab the book.

How do I use the Reading for Meaning strategy, in 250 words or less?

- Pick a complex text.

- Create statement(s) about the text (see AoW screen capture above for a few examples).

- Important: Make sure the statements are supported or refuted by the text.

- Pro tips:

- Use Figure 1.2 on this page to create statements to address specific standards.

- Create thought-provoking statements, so as to engage student interest before reading.

- Before reading, have students preview the statements, and use this opportunity to include any other activity that might “hook” students into the reading. (E.g., I might use the efficient “take a stand” strategy to have them show me whether they agree or disagree with some element of controversy presented in the text.)

- Show students how to “record evidence for and against each statement while (or after) they read” (p. 10)

- After reading, students can discuss their evidence in pairs or small groups, seeking to reach an agreement on which statements are supported or refuted by the text. This can be extended to a whole-class discussion “in which students share and justify their positions” (p. 10), which provides the teacher with an opportunity to “help students clarify their thinking and call their attention to evidence they might have missed or misinterpreted” (p. 10).

- Use student responses, both in their recorded Reading for Meaning statements and in their discussions, as formative data in evaluating how well they understood the text.

RFM develops three moves readers do when grappling with text complexity

In my last post, I mentioned Harvard’s “thinking-intensive reading”; to save you a click, below you’ll find the outline of that framework:

- Previewing: Look “around” the text before you start reading.

- Annotating: Make your reading thinking-intensive from start to finish.

- Outline, summarize, analyze: Take the information apart, look at its parts, and then try to put it back together again in language that is meaningful to you.

- Look for repetitions and patterns.

- Contextualize: Take stock and put the text in perspective.

- Compare and Contrast: Set course readings against each other to determine their relationships (hidden or explicit).

Notice how this aligns with the three phases of the Reading for Meaning strategy:

- Previewing and predicting before reading (which lines up with the first bullet point above)

- Actively searching for relevant info during reading (which is involved in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th bullet points above)

- Reflecting on learning after reading (emphasized in the final two bullet points above)

In short, RFM can serve as a great scaffold for those shorter, complex texts you give your readers.

Scaffolding readers and helping teachers

If the Common Core simply results in teachers chucking complex texts at classes of kids without any support or instruction, then, indeed, the Common Core will have been something worth freaking out about. However, with simple, efficient strategies like Reading for Meaning, teachers can get closer to that sweet spot between under- and over-teaching, and students will end up with the win as more of them enter the college and career world as functionally literate folks.

Have you used RFM statements before? Do you have any further questions I can answer? Holler at your boy below.

Reader Interactions

Download Article

Download Article

Maybe you are in the middle of an exam and suddenly come across a word that makes absolutely no sense. This is usually a cue for most people to panic if a dictionary is not handy. But don’t worry! There are several steps you can take to help you figure out the meaning of a word without a dictionary.

-

1

Read the entire sentence. It can be very frustrating to have your reading interrupted by an unknown word. If you are in the middle of an exam or an assignment for school or work, it can also be very stressful. If you can’t reach for a dictionary, take other steps to figure out what the word means.

- Your first step is to go back and re-read the entire sentence. You probably lost track of what your were reading when you stumbled upon the new word.

- Think about the content of the sentence. Do you understand the sentence without using the new word? Or is it incomprehensible?

- Try underlining the unknown word. This will help you separate it from the rest of the sentence.

-

2

Identify words you do understand. You can often use other words in the sentence to help you define the unknown word. Think about what else is happening in the sentence. Hopefully, this will help you figure out whether the unknown word is a noun, verb, or adjective.

- For example, maybe you are looking at a sentence that says, «It was a very sultry day in the middle of the summer.» You probably understand each word except for «sultry».

- Think about what you know about the summer. It is likely that «sultry» has something to do with weather.

- Maybe your biology exam has this sentence, «Many members of the canine family are predators, looking for other animals to eat.» You can surmise that «predators» prey on other animals.

Advertisement

-

3

Look for illustrative examples. Once you have examined the other words in that sentence, you can move on. Start looking at the sentences that follow the unknown word. An author will often give descriptions that can help you figure out the meaning of an unknown word.[1]

- For example, take the sentence, «It was a very sultry day in the middle of summer.» It could be followed by the sentence, «The heat and humidity made it appealing to sit in the shade and drink lemonade.»

- You can now more confidently define «sultry». The descriptive words such as «heat» and «humidity» are further clues that it is a description of the weather.

- Sometimes, the descriptive examples will be right in the original sentence. For example, it could say, «Sultry days are so damp and hot.»

-

4

Think logically. Sometimes, the context clues will not be as clear. You will have to use logic to figure out the word. You can also use experience, or prior knowledge, of the topic.[2]

- For example, maybe a sentence says, «In the antebellum South, many plantation owners kept slaves.» It is likely that «antebellum» is the unknown word.

- The sentence itself does not offer many clues. However, the following sentences are, «But after the Civil War, slavery was outlawed. This was a major change between the two periods.»

- Think about what you know now. You are reading information about two different time periods, right? Before the Civil War and after the Civil War.

- You can now make a pretty logical assumption about the word «antebellum». Based on your experience and reading the following sentences, you know it probably means «before the war».

-

5

Use other context clues. Sometimes an author will offer other types of clues. Look for restatement. This is where the meaning of the word is restated in other words.

- Here is an example of «restatement»: «The pig squealed in pain. The high-pitched cry was very loud.»

- You can also look for «appositives». This is where an author highlights a specific word by placing a further description between two commas.

- This is an example of the use of an appositive: «The Taj Mahal, which is a massive white marble mausoleum, is one of the most famous landmarks in India.

- You may not know the words «Taj Mahal», but the use of appositives makes it clear that it is a landmark.

Advertisement

-

1

Look for a prefix. Etymology is the study of the meanings of words. It also looks at the origins of words, and how they have changed over time. By learning about etymology, you can find new ways to define unknown words without using a dictionary.

- Start by looking at each part of the word in question. It is very helpful to look to see if the word has a common prefix.

- Prefixes are the first part of the word. For example, a common prefix is «anti».

- «Anti» means «against». Knowing this should help you figure out the meanings of words such as «antibiotic» or «antithesis».

- «Extra» is a prefix that means «beyond». Use this to figure out words such as «extraterrestrial» or «extracurricular».

- Other common prefixes are «hyper», «intro», «macro» and «micro». You can also look for prefixes such as «multi», «neo» and «omni».

-

2

Pay attention to the suffix. The suffix are the letters at the end of the word. There are several suffixes in the English language that are common. They can help you figure out what kind of word you are looking at.

- Some suffixes indicate a noun. For example, «ee» at the end of the word almost always indicates a noun. Some examples are «trainee» and «employee».

- «-ity» is also a common suffix for a noun. Examples include «electricity» and «velocity».

- Other suffixes indicate verbs. For example, «-ate». This is used in words such as «create» and «deviate».

- «-ize» is another verb suffix. Think about the words «exercise» and «prioritize».

-

3

Identify root words. A root word is the core word, without a prefix or suffix. Most words in the English language come from either a Latin or Greek root word.[3]

- By learning common root words, you can begin to identify new words more easily. You will also be able to recognize words that have had a prefix or suffix added.

- An example of a root word is «love». You can add many things to the word: «-ly» to make «lovely».

- «Bio» is a Greek root word. It means «life, or living matter». Think about how we have adapted this root word to become «biology», «biography», or «biodegradable».

- The root word mater- or matri- comes from the Latin word mater, meaning mother. By understanding this root, you can better understand the definitions of words like matron, maternity, matricide, matrimony, and matriarchal.

Advertisement

-

1

Keep notes. If you can increase the size of your vocabulary, you will find yourself less likely to encounter unknown words. There are several steps you can take to effectively build your vocabulary. For example, you can start by writing notes.

- Every time you encounter an unfamiliar word, write it down. Then later, when you have access to a dictionary, you can look it up for a precise definition.

- Keep a small pack of sticky notes with you while you read. You can write the unfamiliar word on a note and just stick it on the page to return to later.

- Start carrying a small notebook. You can use it to keep track of words that you don’t know and new words that you have learned.

-

2

Utilize multiple resources. There are a lot of tools that you can use to help you build your vocabulary. The most obvious is a dictionary. Purchase a hard copy, or book mark an online dictionary that you find useful.

- A thesaurus can also be very helpful. It will give you synonyms for all of the new words you are learning.

- Try a word of the day calendar. These handle desk tools will give you a new word to learn each day. They are available online and at bookstores.

-

3

Read a lot. Reading is one of the best ways to increase the size of your vocabulary. Make it a point to read each day. Both fiction and non-fiction will be helpful.

- Novels can expose you to new words. For example, reading the latest legal thriller will likely expose you to some legal jargon you’ve never heard before.

- Read the newspaper. Some papers even have a daily feature that highlights language and explores the meanings of words.

- Make time to read each day. You could make it a point to scroll through the news while you drink your morning coffee, for example.

-

4

Play games. Learning can actually be fun! There are many enjoyable activities that can help you to build your vocabulary. Try doing crossword puzzles.

- Crossword puzzles are a great way to learn new words. They will also stretch your brain by giving you interesting clues to figure out the right word.

- Play Scrabble. You’ll quickly learn that unusual words can often score the most points.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

Is there a list of prefixes/suffixes, or a simple etymology handbook, that I can obtain from the Internet or someplace else?

I’m sure there are many! Check websites like Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or other booksellers who might sell grammar handbooks. You could also try checking your local book stores.

-

Question

How does one find out and understand the formation of words?

If you can recognize the prefixes, suffixes, and anything else that might alter the root word, then you’ll know how the root is being altered. For example, ‘amuse’ is made up of ‘a’ as in ‘not’ and ‘muse’ referring to ponderous thought. Even if you don’t recognize the root ‘muse’ because it’s a more archaic term, you know that the ‘a’ inverses it’s meaning.

-

Question

How can I know the exact meaning of a word using dictionaries from many leanings given?

Substitute each meaning into the sentence where you encountered the word, and see which definition makes the most sense within the context of that sentence.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

-

Keep a notebook. This could be useful if you come across a word that you want to learn later, if you want to list any words that share suffixes or prefixes (both of which are known as «roots», which also include anything that goes into the middle.)

-

Read etymology dictionaries. They are found online and presumably in bookstores if you look hard enough.

-

Make your own notes in your personal English notebook to remember important points later on.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To understand a word without a dictionary, try re-reading the entire sentence to see if the context helps you to find out what the word means. If it’s unclear, try to figure it out by thinking about the meaning of the words you’re familiar with, since the unknown word might have a similar meaning. Additionally, look for common prefixes in words, such as «anti,» which means against, or «extra,» which means beyond. Next, check the following sentences for clues, such as the topic the word is related to. Alternatively, keep a list of unknown words so you can check them in a dictionary at a later date. For tips on how to identify root words and how to learn words by doing crossword puzzles, read on!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 215,260 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Aaron Junior

Jul 26, 2016

«This article has really helped me especially finding the meaning of the word using prefixes, suffixes, and word…» more

Did this article help you?

contributed by Kathy Glass

We often ask students to use context clues to figure out a word’s meaning. That makes it is our job as teachers to formally teach how authors use them.

In doing so, students become armed with an inventory of ways (such as reading response questions) to access unknown words to help gain a deeper meaning of the text. Without awareness of the types of context clues, students are at a disadvantage to decipher meanings for themselves.

Teaching this skill supports self-agency so students can define unfamiliar words independently. The following are devices that authors use to incorporate context clues into their writing. The point is not that students memorize each type of context clue. It is more that they come to understand that authors give hints in all kinds of ways to help readers figure out what words mean so they are alert to these devices.

Although the following list seems straightforward, neat and tidy, demonstrate to students to read the surrounding passage in which unfamiliar words appear. This helps readers infer a word’s meaning and appreciate the entire passage where the word resides.

7 Strategies For Using Context Clues In Reading

1. Word Parts

The idea: Break down the different parts of a word—base word (word stem or root word), prefixes, and suffixes—to figure out what it means. Some words have a prefix only (reread), a suffix only (reading), both a prefix and a suffix (prereading), a combination (unreadableness), or neither (read).

Discrimination

Dis-: not, opposite of, reverse, deprive of; apart, away

crimin: verdict, judicial decision; judgment

tion: indicates the word is a noun

2. Definition/explanation

The idea: Look for a definition or an explanation within the sentence.

• Discrimination or unfairly targeting one or more groups by those who perceive themselves to be superior can cause distress.

• Vulnerable people are oftentimes in need of protection under certain laws so others cannot take advantage of them.

3. Synonym

The idea: Words next to the unknown word can be a clue that there is a synonym.

• Discrimination or bias can cause distress toward the targeted group.

• When people know they are vulnerable or defenseless, they tend to protect themselves to avoid harm.

4. Example

The idea: Providing examples of the unknown word can give readers a clue to meaning.

• Like shunning smokers in restaurants by making them satisfy their habit outside, discrimination targets a perceived undesirable group.

• Vulnerable people, such as young children, the elderly, or handicapped individuals, might have protections under certain laws.

5. Antonym/contrast

The idea: opposite information about the unknown word can be offset by words and phrases such as unlike, as opposed to, different from.

• Discrimination, as opposed to fairness for all people, can have damaging effects on a targeted group.

• Vulnerable people, unlike those who can stand up for themselves, tend to be the target of unethical or dangerous individuals.

6. Analogy

The idea: Comparisons of the word help to determine what it means.

• The ill effects of discrimination are like hateful, wicked tendrils gripping the heart.

• Vulnerable people can be like fragile glass in need of care and attention.

7. Appositive

The idea: Look for the grammatical structure of appositives which can provide a definition, synonym, or example.

• Discrimination, the act of showing bias to one group, can have damaging effects.

• The elderly and handicapped, a vulnerable group of individuals, have laws to protect them from unethical individuals.

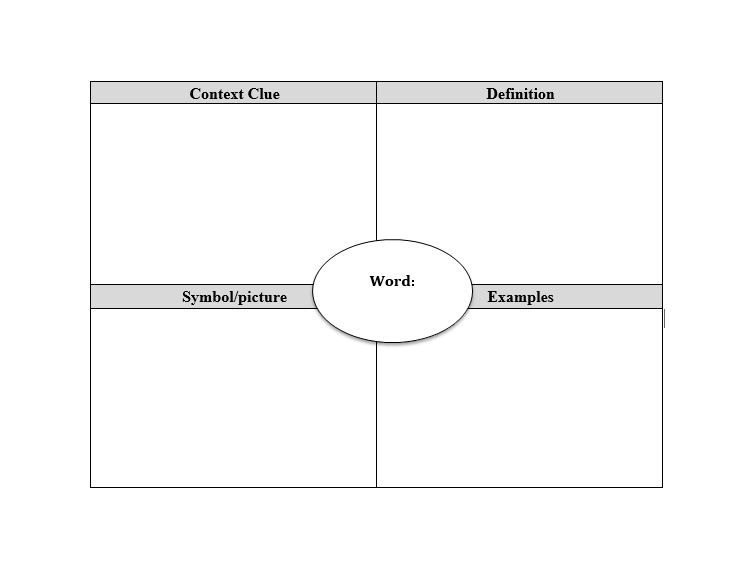

Once students identify the context clue, orchestrate activities for students to learn the word so they can use it when speaking and within their writing. Students can complete the graphic organizer in Figure A individually or with pairs for several words using online and print resources.

Figure A: 4-Square Graphic Organizer

An excellent source is vocabulary.com which provides explanations and examples of words. Students can also use the organizer as a game by completing only some of the quadrants and asking classmates to use the context clues on the figure to complete the others.

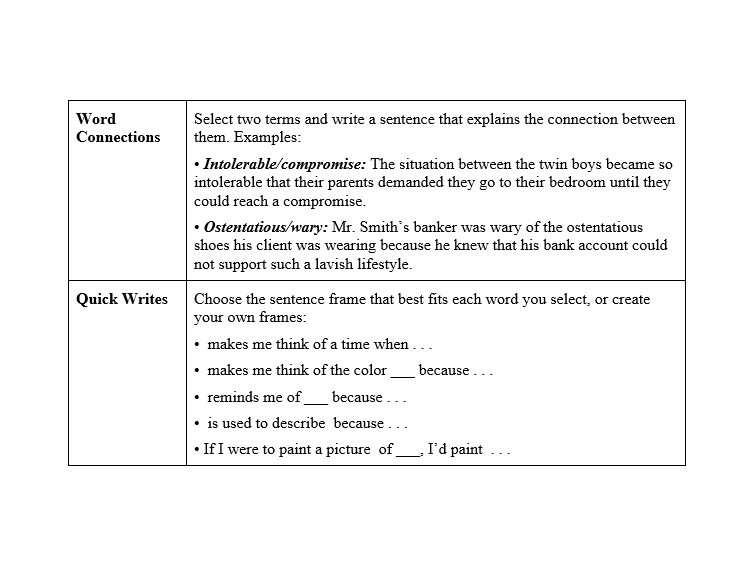

Figure B provides three different options that can be assigned as an in-class or homework assignment. Adapt the tasks so students use the words expressly associated with the targeted complex text.

Figure B: Short Writing Task Options

Examples

• Intolerable/compromise: The situation between the twin boys became so intolerable that their parents demanded they go to their bedroom until they could reach a compromise.

• Ostentatious/wary: Mr. Smith’s banker was wary of the ostentatious shoes his client was wearing because he knew that his bank account could not support such a lavish lifestyle.

Quick Writes

1. Choose the sentence frame that best fits each word you select or create your own frames

• makes me think of a time when . . .

• makes me think of the color ___ because . . .

• reminds me of ___ because . . .

• is used to describe because . . .

• If I were to paint a picture of ___, I’d paint . . .

2. Create examples and non-examples of your selected words

Examples for diversity

• The United States is home to people from different cultures and backgrounds.

• The United Nations is comprised of representatives from all over the world.

• A mall’s food court includes food from different countries.

Non-examples of diversity

• An all-women’s school

• A board of directors for a company composed entirely of one gender or race

• Before Civil Rights laws, public schools in the South admitted only white students.

Conclusion

Authors do not always provide context clues throughout the text because they might have the assumption that readers come to the text knowing the meaning of certain words. However, when these clues are present, equipping students with the tools to use them productively positions them well to further their reading comprehension.

Adapted from Complex Text Decoded: How to Design Lessons and Use Strategies That Target Authentic Texts by Kathy T. Glass (ASCD, 2015).

Kathy Glass consults nationally with schools and districts, presents at conferences, and teaches seminars for university and county programs delivering customized professional development. A former master teacher, she has been in education for more than 25 years and works with administrators and teachers in groups of varying sizes from kindergarten through high school. She is the author of Complex Text Decoded: How to Design Lessons and Use Strategies That Target Authentic Texts. Connect with Kathy through her website, www.kathyglassconsulting.com.