Word for Microsoft 365 Outlook for Microsoft 365 PowerPoint for Microsoft 365 Word 2021 Outlook 2021 PowerPoint 2021 OneNote 2021 Word 2019 Outlook 2019 PowerPoint 2019 Word 2016 Outlook 2016 PowerPoint 2016 OneNote 2016 Word 2013 Outlook 2013 PowerPoint 2013 OneNote 2013 Office for business Office 365 Small Business Word 2010 Outlook 2010 PowerPoint 2010 OneNote 2010 More…Less

Speak is a built-in feature of Word, Outlook, PowerPoint, and OneNote. You can use Speak to have text read aloud in the language of your version of Office.

Text-to-speech (TTS) is the ability of your computer to play back written text as spoken words. Depending upon your configuration and installed TTS engines, you can hear most text that appears on your screen in Word, Outlook, PowerPoint, and OneNote. For example, if you’re using the English version of Office, the English TTS engine is automatically installed. To use text-to-speech in different languages, see Using the Speak feature with Multilingual TTS.

To learn how to configure Excel for text-to-speech, see Converting text to speech in Excel.

Add Speak to the Quick Access Toolbar

You can add the Speak command to your Quick Access Toolbar by doing the following in Word, Outlook, PowerPoint, and OneNote:

-

Next to the Quick Access Toolbar, click Customize Quick Access Toolbar.

-

Click More Commands.

-

In the Choose commands from list, select All Commands.

-

Scroll down to the Speak command, select it, and then click Add.

-

Click OK.

Use Speak to read text aloud

After you have added the Speak command to your Quick Access Toolbar, you can hear single words or blocks of text read aloud by selecting the text you want to hear and then clicking the Speak icon on the Quick Access Toolbar.

Learn more

Listen to your Word documents with Read Aloud

Listen to your Outlook email messages with Read Aloud

Converting text to speech in Excel

Dictate text using Speech Recognition

Learning Tools in Word

Hear text read aloud with Narrator

Using the Save as Daisy add-in for Word

Need more help?

Want more options?

Explore subscription benefits, browse training courses, learn how to secure your device, and more.

Communities help you ask and answer questions, give feedback, and hear from experts with rich knowledge.

-

HOME

-

Speech delivery

- How to practice a speech

›

›

— to rehearse or to ‘wing it’, that is the question

By: Susan Dugdale | Last modified: 02-07-2022

Do you know how to rehearse, or practice, a speech?

Do you know how to structure the time you have between preparing, (writing), your speech and delivering it well?

What do you think you should focus on first?

If you want to rehearse, rather than ‘wing it’, but really don’t know much about the process, you’re in the right place.

Jump straight to the 3 important pre-rehearsal options you need to review and then on to the 7 ‘how to rehearse’ tips.

To ‘wing’, or not to ‘wing it’?

There’s a fairly large group of people who have convinced themselves there’s no real need to rehearse a speech at all. They prefer to ‘wing it’!

Perhaps that’s been your preference too.

Here’s the strangely crooked, yet compelling thinking that often sits in behind the decision to ‘wing it’. It delivers a win if you fail AND a win if you succeed.

When ‘winging it’ works

For example if I go out there and, with minimal preparation, wow the audience that’s proof preparation, rehearsing, is a waste of time.

Who needs it? I don’t. They laughed at my jokes. They asked me questions, and they told me I’d done really well. I’m good, without practice.

When ‘winging it’ fails to fly

On the other hand, if I go out there and forget to mention several critical points I was supposed to make, nobody laughs at my jokes, and the audience is restless the entire time I’m speaking, that’s understandable. Because, after all I was ‘winging it’.

I wasn’t really trying. If I had, I would be so much better!

That aside, this lackluster result doesn’t count. I don’t need to feel embarrassed because I hadn’t committed myself to do the very best I could in the first place.

‘winging it’, accountability and self protection

In many instances ‘winging it’ is a way of avoiding accountability. It’s a form of self-protection, a shield to hide behind. After all what might happen if you genuinely put a whole lot of work in and despite doing that, fail?

That would feel hard, and very painful. It could be enough for some to say, why bother? And walk away shrugging their shoulders.

(However, that is not you!)

Got the words sorted, so the speech is done.

Alongside ‘winging it’, there’s another common assumption. This one is about the speech itself; the content, the words you say.

The assumption is that once the content is decided on and prepared, the speech is ready for delivery.

You do not need to do anything more. Because, heaven forbid, you would sound robotic, or false, if you practiced.

I want my speech to be real, to be natural

When the time to deliver the speech arrives, you open your mouth and the words come out.

It’s spontaneous. It’s natural. And whatever happens, is fine because it’s real.

‘Umming’ & ‘ahhing’, gear mishaps, and awkward silences

That includes all the unconscious speech habits you may have: ‘umming’ and ‘ahhing’, awkward pausing, gabbling caused by nervousness, fidgeting, and so on.

In addition, it also covers any other unforeseen events.

For example, glitches with gear because what was required wasn’t thought through, like these:

- The lead brought along for the projector not being long enough to reach the wall socket.

- The cue cards not being numbered. When dropped it takes an age to figure out the order they should be in.

None of these awkward moments need happen. They may be natural but that doesn’t make them good.

Please understand that …

Rehearsing can make ordinary extraordinary

Think about it.

Writing is only part of the process. It’s delivery that completes it.

Despite what you may have been told, and want to believe, the act of giving a speech is performance and delivering it well takes practice.

Ultimately ‘winging’ it will let you down

If you’ve sat through ho-hum presentations finding your finger nails more interesting, the odds are the delivery was less than polished.

The content may have been excellent. It may have been well researched but because the speaker lacked basic delivery skills, the entire speech was compromised.

That is why, if you care about your audience, your content, and yourself, you need to know how to rehearse.

Rehearsal refines your speech

It helps you to identify areas needing work. For instance:

- Is the opening effective?

- Do the transitions from one idea to the next work?

- Do you need to slow your speech rate? When? Are some parts better faster or slower?

- Do you need pauses? Where? How long for?

- Are your words clearly spoken? Can people hear you adequately?

- Are any props you’ve planned fully integrated into the flow of your speech?

- Is the ending strong?

- Does the speech fit the time allowance?

All this, and more, you’ll find out through rehearsal or practice.

How you deliver a speech makes a HUGE difference. Good delivery helps you to reach out and communicate well with your audience.

Pre-rehearsal

Before you begin learning how to rehearse you need to make a critical decision. What you decide will have an impact on how you practice and deliver your speech.

Make a choice between:

- Reading your speech from a word-for-word

script.

This is where you have EVERYTHING you are going to say fully written out. - Using cue or note cards on which you

have written the headings of your main ideas in order and the key words associated with each of them.

(Cue cards are easily made from small index cards. One is used per main idea and its key words and phrases are clearly written on each. You speak from memory using the keywords/phrases as a trigger.) - Committing your entire speech to memory. In this

option you have neither cue cards or a script.

There are positives and negatives for all three options.

Word-for-word

script

Using a full manuscript (a word-for-word document) can be positive as it acts as a safety net for a nervous or first time speaker. The downside is reading.

When people read they tend not to make eye contact with their audience. And neither is their voice projected outward. Instead it’s focused downward to the page.

If the script is in their hands, rather than on a stand, then they’re not free to gesture and there is always the temptation to

mask or cover their face with it.

If a stand is used to place papers on, then it’s

between them and the audience, creating a barrier.

There are ways around these problems.

- The first is to place the stand to one side instead of directly in front of you.

- The second is make sure the stand is at eye-level to ensure easy upright reading.

(You won’t be bending down and therefore presenting the top of your head rather than your face to the audience.) -

Another is to make sure the script is easily read.

A mess of scribbled notes isn’t good! If you lose your place, you’ll be struggling to find it. Type them up in a clear good sized easy-to-read font, double space and number your pages before printing them out single-sided. - And to practice reading your speech aloud.

The ability to read well aloud is a great skill to have, and particularly useful if you have to give a speech at very short notice.

Visit How to read a speech effectively for specific tips to ensure you don’t put your audience to sleep.

If full scripting is your choice, make a clean copy of your speech before going on to the ‘How to Rehearse’ tips.

Cue or note cards*

The positives for using cue cards are they are smaller than a full size script and therefore can be held unobtrusively in one hand. Because you are not using a stand for notes you’re not blocked off from your audience. This means you can use eye contact more

easily and direct your speech where you wish. And because you’re not following a word-for-word script, you’re freer to be more spontaneous.

The downside of cue cards is apparent if they haven’t been prepared properly.

If they’re not ordered you run the risk of getting muddled. If they’re not clear and easily read, you run the same risk. The other major negative is what happens if you stumble in remembering how you linked your ideas together.

If cue cards are your choice, you’ll need to prepare

them before you go on to the How to Rehearse tips.

You’ll find a page of instructions here on how to make good cue cards.

*The term ‘cue’ comes from theater. A cue for an actor is a signal to begin speaking, or enter, or do some other action required by the play.

Memorizing your

speech

The positives for committing your speech entirely to memory is that you meet the audience completely free of notes. You can gesture, ad lib etc where you wish, provided of course, that you can keep yourself on track.

While this option is good for speakers used to being in front of people, it can be daunting for a novice. It is also difficult to pull off with certain styles of speech.

For example, if you are giving a complex business presentation which includes the breakdown and analysis of large chunks of data, this would be risky. So think carefully and wisely before making the decision to go solo.

Styles of speech most suitable for giving entirely from memory are eulogies, wedding, retirement speeches…the type which include personal story telling. Here it can work brilliantly, although you do need to keep in mind that rote learning, without expressiveness, can make delivery wooden.

Click the link for more information on using acronyms as mnemonics (memory aids) to help remember your speech.

If memorizing your speech is your choice, pay particular attention to expressiveness when it comes to the ‘How to Rehearse’ tips.

How to rehearse tips

Aim to have a minimum of three rehearsals before your final presentation in front of an audience. If you have the time available for more, take it.

The more you run your speech through, the more confidence you’ll have and the easier it becomes to deliver it more effectively.

The first two rehearsals are to iron out any glitches in either your text or delivery and to integrate any resource material you may be using. These could be photographs, a power point presentation etc.

The third is a dress rehearsal for the real thing.

How to rehearse tip one: reading aloud

Read your speech notes several times out loud. Do the same thing if you are using cue cards.

Hearing yourself speak will help you to familiarize yourself with the flow of your material more quickly. It will also help you to spot potential difficulties more easily.

If you find some phrases awkward to say change them. Similarly if you notice leaps in logic fix them.

Time the speech. If it is too long for the time allocated, cut it to fit, aiming to end before you are required to.

During this beginning phase do not worry about expression or gesture. You will cover that in ‘tip 3’.

Right now your primary focus is on getting the flow of the content fluent. That means without jumbling the order or hesitating because you’ve forgotten what you planned to say!

How to practice tip two: watching yourself

Now record yourself using the camera on your smart phone. Then play it back.

Actually seeing and hearing yourself while presenting is a revelation. You can no longer hide in the comfortable illusion of what you ‘think’ you do. This is your own reality TV show.

You will see the good, the bad and the ugly. The good news about that is that you are giving yourself the opportunity to learn — to become better.

How to rehearse tip three: delivery demons

While watching yourself look out for anything hindering your communication, either in your body language or speech.

These delivery demons could be:

- Habitual unconscious gestures like fiddling with your hair, pulling faces when you can’t remember what is next, standing awkwardly, swaying, pulling at your clothes…

- Irregular breathing running you out of breath over long sentences or holding your breath which makes your voice sound strained.

- Racing your speech through

- Pauses or breaks in the wrong places which weaken or alter your meaning

- Specific words or phrases that trip you up e.g. a name

- Holding your notes in a way that masks your face

- Rattling or fiddling with your notes if you are reading from them

- Hiding behind, or slouching over, the stand if you are using one

- Dropping or raising your voice at the end of sentences

- Mumbling

- Repeated phrases eg. ‘and then I…’,’and then I…’, ‘and then I…’

- Repeated fillers eg. ‘um’, ‘err’…

- Lack of gesture or too much of the same gesture

- Lack of eye contact or smiling

- Minimal variation in tone or pace

- Bumbling the use of resources through not having them organised.

How to rehearse tip four: fixing the faults

When you see/catch yourself committing any of the grievous speech delivery crimes listed above under ‘delivery demons’, STOP.

Take a very deep breath, fix the problem and start again from where you left off.

Help is a click away

You can find help with speech rate (either going too fast or too slow) by clicking the link.

If you find yourself mumbling and running words together try using some of these diction exercises.

If you need to work on pausing and breathing effectively you’ll find these exercises help.

Click this link for assistance with vocal variety issues, like monotone delivery and lack of expressiveness

Go to this link for gesture and body language tips.

Do be patient with yourself.

Some of the habits you’ve just become aware of will be deeply ingrained. It will take sustained effort to create new, more beneficial ones. However the more practice you do, the quicker you’ll get there.

How to rehearse tip five: making notes

If it’s a matter of when and where to pause either for a breath or to stress an important point, mark it on your cue cards or script.

In the same way mark passages needing to taken more slowly, or words requiring extra emphasis.

Make whatever notes you need to remind yourself of what you want to do to improve your delivery.

How to rehearse tip six: using humor

Humor can be incredibly difficult to get right. One person’s funny, is another person’s not.

If you have included jokes, they need special timing attention. Point up the cue for the audience to laugh by briefly holding back the punch line and leave space for the audience to respond before carrying on.

For your own self-preservation click for more information on How to Use Humor Effectively. You need to know your audience!

How to rehearse tip seven: the dress rehearsal

Testing, testing, testing …

- Run through your entire presentation as though it was the real thing. And if possible, do it in the venue you’ll be using.

- Wear the clothes you’ll be wearing for the event so you can be sure you feel comfortable and that they’re not restricting in any way.

There’s a helpful personal grooming checklist here with guidelines on choosing clothing. - Set up your stand, if you are using one, in a similar position to the one you’ll use on the day.

- If you are using any electronic equipment for example a microphone be sure to rehearse with it.

Can’t make up your mind whether to use the podium microphone or attach one to your lapel? The pros and cons of both are discussed here. - If you can present to trusted friends or a members of your family, do it! Their feedback could provide in valuable last minute suggestions. Tell them exactly what you want feedback on before you start. Ask them to take notes during your speech to give to you after it’s finished.

- Do not STOP if you falter. Keep going.

- When you’re done make any minor adjustments you need to and repeat to integrate them.

Rehearsing a question & answer session

And lastly, if your speech/presentation includes a question and answer session think through the types of questions you are likely to be asked. Prepare answers to cover them and practice delivering those as well.

It’s tempting to think that once you’re through the prepared speech the rest will fall into place easily. However if you haven’t put the thought and preparation in it will be transparently obvious! And you could undo everything you’ve worked so hard to put in place. That’s a risk so easily avoided. Don’t take it.

And very lastly …

Here’s a couple more pages you might find useful.

The first is the perfect complement to this one: how to practice public speaking. In this article I cover aspects like segmenting your practice, how to get useful feedback, how to deal with distractions, and more. The topics supplement what you’ve already read about on this page.

Go to how to practice public speaking

The second page covers 5 strategies to tame public speaking fear.

The last of the 5 suggestions is to create and work what I call a Bring-it-On list — a comprehensive preparation checklist to minimize the possibility of anything under your direct control going sideways and jeopardizing your presentation. You’ll see my example list contains many of the items mentioned here plus some more.

To get you started I’ve made a printable checklist. Download it. Take my list and adapt it to fit your own situation.

Collect the printable from 5 strategies to beat public speaking nerves.

- Return to top of how to rehearse

While a speaker’s primary goal is to engage and inspire, many communicators are inclined to write out their speeches because they mistakenly believe their goal is to be perceived as a fantastic speaker or writer. This mindset has nothing to do with getting your point across or doing your job and sends you down a path of performance (“I want to impress you”), not presentation (“I want to convince you”). Writing a full speech is a process that excludes the audience, whereas delivering a speech with limited notes involves and incorporates the audience into the experience. This concept is critical, because humans are more apt to give attention to speakers who seem to, or actually do, demonstrate a sincere interest in them. Speaking spontaneously, with authentic conviction and awareness, signals that you have something to say — a point you feel so strongly about that you’re willing to express it personally and out loud. Anyone can read a script. Leaders champion their ideas.

-

Tweet

-

Post

-

Share

-

Annotate

-

Save

-

Get PDF

-

Buy Copies

-

Print

“Don’t worry,” a coaching client once told me shortly after I saw her rehearse her presentation. “I’ll have it completely written and memorized by next week!”

To my trained ears, she might as well have been saying, “Don’t worry, I’ll make my task pointlessly hard and ensure a distant connection with my audience!”

Like many people, she thought a “good speech” is something you write out word-for-word and read aloud — perhaps even memorize. Some learned this approach in school. Others inferred it from seeing stirring, perfect speeches from politicians, award recipients, and fictional television characters.

If you have a team of speechwriters working for you, you should certainly have them work their magic and then take your position behind glassy teleprompters to serve it up. But that’s not the majority of us. Most of us give presentations more frequently in business meetings, online conferences, and a wide range of small- to mid-size internal and external events. In those typical settings, writing, reading, and certainly memorizing a word-for-word speech is actually one of the most destructive and counterproductive tactics you can take as a presenter.

Below are some of the biggest pitfalls of fully writing, reading, and memorizing speeches, as well as what you should be doing instead to accomplish what should be your main goal — engaging and inspiring your audience.

Writing Focuses on the Wrong Things

While a speaker’s primary goal is to engage and inspire, many communicators are inclined to write out their speeches because they mistakenly believe their goal is to be perceived as a fantastic speaker or writer. This mindset has nothing to do with getting your point across or doing your job, and sends you down a path of performance (“I want to impress you”), not presentation (“I want to convince you”).

In most cases, writing a full speech is also pointlessly time-consuming. For every important concept you raise, you’re crafting many extra lines to set up and contextualize those ideas. These words and transitions should come naturally and sound human, but when read word-for-word, they can come across like the voice on a robocall — friendly but noticeably stilted and artificial.

A presentation audience doesn’t even have time to process — much less remember — specific words and phrases, so time spent conceiving and writing “the perfect words” is largely wasted on them, even if it brings comfort or pride to the speaker.

Finally, writing a full speech is a process that excludes the audience, whereas delivering a speech with limited notes involves and incorporates the audience into the experience. This concept is critical, because humans are more apt to give attention to speakers who seem to, or actually do, demonstrate a sincere interest in them. “The key to delivering a successful speech is showing your audience members that you care about them,” says Steve D. Cohen, an author and professor at Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. “If you maintain an audience-centered approach, your listeners will reward you with appreciation.”

Imagine someone recommending a movie to you. Should that person look you in the eye and explain what makes the film compelling, or should they go home, write and edit a review, come back, and then read the finished review to you? Now imagine that person recommending not a movie, but a brilliant new marketing strategy, a breakthrough vaccine delivery system, or a campaign to save the earth. As an interested human being, you want to hear them make that case live and in their own spontaneously-generated words, not read something created apart from you and without you in mind.

Reading Builds a Barrier

Reading a speech word-for-word has its own unique disadvantages. It reduces the amount of eye contact you have with an audience, whether in an in-person meeting or on a Zoom call. Reading also diminishes your ability to speak with personal conviction because, when you read a speech aloud, your mind is not focused on enlightening or inspiring your audience; it’s focused on the task of reading hundreds of carefully chosen words in succession. It isn’t easy to read words and project fervency simultaneously, but when you remove the script, you restore the human connection between the speaker and their audience and enable more emotional transmissions.

In more than 15 years of watching and training speakers, I’ve rarely seen someone read a speech as compellingly as someone who presents a live point. Again, audiences typically zone out when a presenter is reading, because they feel cut out of the process of interpersonal communication.

Even the TED Commandments — a list of do’s and don’ts allegedly given to TED speakers — includes Commandment #9:

Thou shalt not read thy speech.

“Probably the worst of all public speaking sins is the temptation to disappear into your notes and read, as opposed to speak, to your audience. If they wanted to be read to, you could’ve just sent them an email with your speech content.”

Speaking spontaneously, with authentic conviction and awareness, signals that you have something to say — a point you feel so strongly about that you’re willing to express it personally and out loud. That sounds powerful, because it is.

Some people insist on writing full speeches to calm their public speaking anxiety. After all, how can you mess up when all you need to do is read 932 words in order, sprinkling in some emphasis and eye contact? But when you focus mostly on getting from the first word to the final 932nd, the whole point of public speaking is reduced to a robotic task.

Sacrificing audience impact to preserve your comfort and security is not a sustainable approach. The best way to overcome public speaking fear is to embrace your purpose, not shrink from it.

Memorization Is Asking for Trouble

When you memorize something, you are still reading — now with the script in your head instead of in your hands — and the slightest memory failure can cause you to lose your place and throw you off. Even small memory lapses and bobbles may reveal to your audience you’re reciting from a script, which can injure your credibility, your authenticity, and their respect for you as an invited presenter.

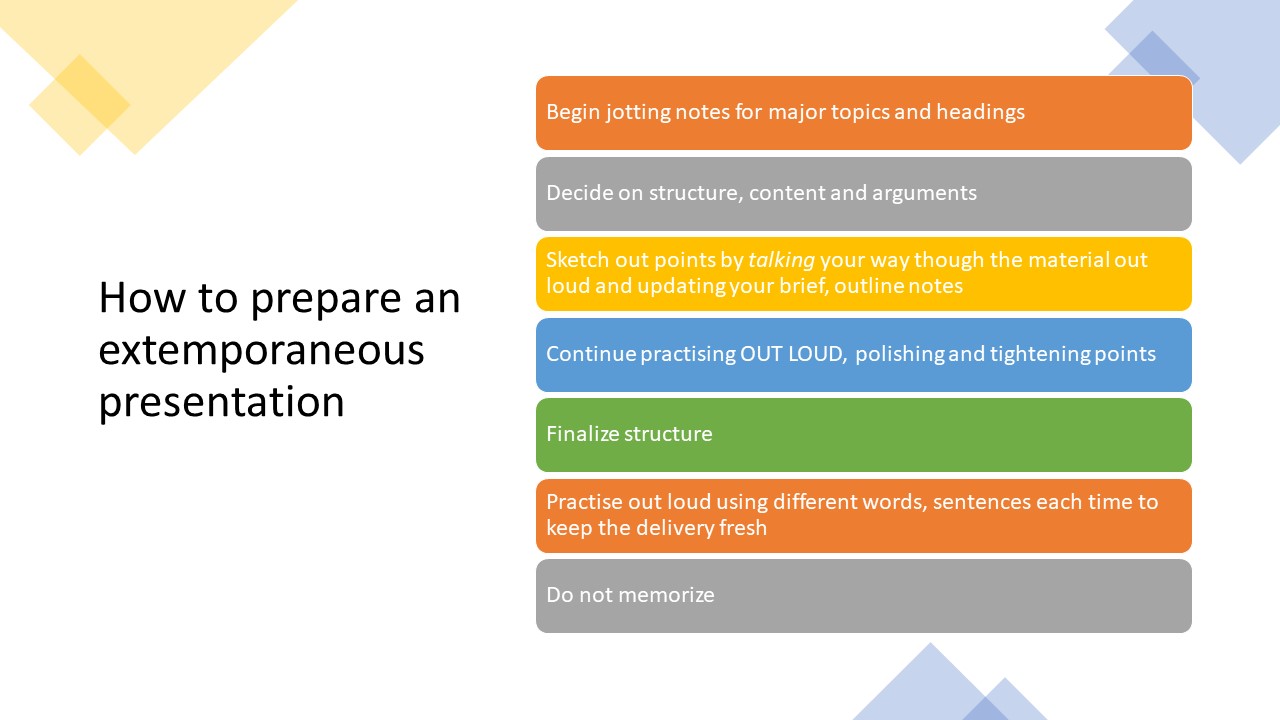

Why risk forgetting something you memorized or bearing the engagement handicaps of writing and reading when there’s a much easier, quicker, and more effective way to prepare, practice, and present? For me, that better way consists of four basic steps:

-

Start with an Outline

Your grade school teachers were right: Every good communication starts with an outline — a roadmap that indicates the points you must hit on the way to your destination. The most effective outlines start with a proposition (I’m selling you an idea), followed by points that support that proposition (I’m showing you why the idea is beneficial to you).

The more you practice, the shorter that outline should become as you realize you require fewer and fewer reminders than you thought you needed.

-

Create Useful Notes

Eventually, your outline becomes so small and concise you can fit it on an index card. That’s your notes. Your notes are your cheat sheet, feeding you major points and essential details you might otherwise forget. I often tell my clients to construct their notes as they would a shopping list, complete with bullets, abbreviations, and no complete sentences.

On a shopping list you don’t write, “Buy three fresh avocados from aisle four in the produce section.” You write “3 avocados.”

In fact, your notes should be so personally coded for your personal use that they read as nonsensical to someone else.

The good thing about having notes versus a script is that, after looking up at your audience, you can look down and easily track where you are and what you need to say next. But if you lose your place between, say, words 439 and 440, it will take a conspicuous amount of time to recover.

-

Practice Effectively

You already know that practice is important, but it’s crucial to understand the difference between effective and ineffective presentation practice. Ineffective practice is thinking about your speech and mumbling the words, which only helps you know your presentation better. Effective practice is having your mind and mouth work together to convey your speech aloud and in real time. This tactic comes closest to simulating what you’ll be doing when you deliver your speech for real.

You don’t need a person, a mirror, or a camera to practice effectively — just you, your mind, and your mouth, practicing by physically presenting.

-

Trust Yourself More Than Your Script

You speak without scripts in your workplace all the time: in meetings, job interviews, performance reviews, conference calls, and more. If that’s true, then you spend a lot of time trusting yourself, your experience, and your credibility when you speak spontaneously. Use that understanding to confidently realize you never need a word-for-word script to make compelling points.

When you know your points well, prepare good notes, and practice the right way, you’ll understand that conveying your ideas live and unscripted is easier, less scary, and more effective than you thought.

That leap of faith is also a leap of progress. Anyone can read a script. Leaders champion their ideas.

Reading a speech is not the recommended way to deliver a speech.

But, there are many occasions where you may find yourself in exactly this situation, whether due to the circumstances of the event or unavoidable constraints on time. Or, maybe you’ve got to read a speech that you haven’t written!

When you must read a speech, are there ways to enhance your delivery? Two Six Minutes readers approach this question from different perspectives:

Patricia McArver writes:

How should a speechwriter mark up copy so that the speaker will deliver the message with emphasis and pauses in the right places? As a writer, you think it’s obvious, but that’s not always the case.

Jacob Miller asks:

Do you have any tips for annotating a speech? When I try to read my speeches, I frequently get lost in the print, and sometimes I put the emphasis in the wrong places. Is there anything I can do other than the obvious — practicing more?

When is it okay to read a speech?

Although I strongly encourage you to read your speeches as rarely as possible, there are occasions when it is acceptable, or even expected. These include:

- You are speaking at a highly formal occasion (e.g. a commencement speech)

- You are delivering a particularly emotional speech (e.g. a wedding speech, a eulogy)

- You are forced to read word-for-word by lawyers or campaign managers (e.g. a corporate statement; a political speech)

- A speechwriter has written your speech.

- Life prevented you from preparing adequately. (Don’t let this happen often… your speech really would go better if you prepare.)

- Within a larger speech, you are reading a passage from another work (e.g. a poem; a book excerpt).

- You are a brand new speaker, and you haven’t developed the confidence yet to go without a script.

The drawbacks of reading from a script

Once you are committed to reading your speech (or a portion of it), it’s helpful to consider the drawbacks so that you can attempt to compensate for them.

Negative effects of reading include:

- Your eyes are on your page, and not connecting with your audience.

- Your eyes are on your page, and not reading feedback from your audience.

- Your head is tipped down, which inhibits your vocal projection.

- You are locked into the words, not as free to introduce a conversational style.

- You risk skipping words or lines, and sounding foolish.

- Your vocal variety tends to be limited, as you concentrate on simply “getting the words out” instead of worrying how they sound.

Creating the best printed speech

Whether you are writing your own speech, or writing one for someone else to deliver, there are several strategies for creating an optimal page, including:

- Don’t hand-print or write your speech. I don’t know a person in the world who writes or prints as neatly as Times New Roman font. Even slight imperfections in your penmanship make you work harder than necessary when reading. Type it in and print it out.

- Print with a large font size — larger than you would typically use. For example, I typically print documents with 9 or 10 point font. When I have to read during a speech, I make sure it is 12, 14, or 18-point font. Larger typography makes it easier to read, and easier to find your place as you look up and then back down again.

- Print using multiple narrow columns. It’s harder to read wide columns of text (your eye is strained to “wrap” to the next line), so format it into two or three columns.

- Use subheadings. You won’t read these, of course, but using subheadings can help to structure the speech on the page, and is a good signal to take an extended pause.

- Use line breaks to mark pauses, even within sentences. This technique is wonderfully explained in Speak Like Churchill, Stand Like Lincoln (read the Six Minutes review). The idea is to divide the sentence into bite-sized chunks. Between each chunk, insert a slight pause, which is marked by the line break. Skilled speakers can use this technique to create a balanced cadence that overcomes some of the drawbacks of reading.

- Use ellipses to mark pauses, … or perhaps words that should be draaawn out for effect.

- Use italics or bolding to mark words, phrases, or entire sentences that require extra emphasis. Pick one style and use it consistently, so as not to confuse yourself or your speaker. I suggest not using underlining for this purpose as it will often truncate the bottoms of letters making them harder to read.

- Use italics or bolding or color to mark linked words, which may be separated by several other words or sentences. Consider this a form of super-emphasis.

- Put instructional annotations (not meant to be read) in the margins. For years, I used to write “BREATHE” and “SLOW DOWN” in red pen on my speeches.

What can you do with your body?

The printed page acts a bit like handcuffs, restraining your gestures and locking your body position in non-optimal ways. Still, there are a few things you can do to improve the situation.

- As much as possible, position your printed page high and away from your body. (i.e. if you are using a lectern, make sure it isn’t set too low, and try to read from the upper part.) This will keep your gaze closer to your audience, and also allow better voice projection.

- Don’t forget about gestures. It’s hard to incorporate them, but do your best to avoid a completely lifeless body.

- Use expressive facial gestures while you read. Though it may seem counter-intuitive to use facial gestures even when you are facing downward, forcing yourself to generate appropriate facial gestures will bring your vocal variety alive.

Last words…

Minimize reading your speeches. For most settings, your delivery will be much more effective if you free yourself of the page. If you can only memorize a few sentences, then memorize your opening and closing words.

Don’t accept the “I didn’t have time to learn it” excuse from yourself repeatedly. You owe it to yourself and to your future audiences to break free of the page.

All of these techniques above can be utilized to prepare yourself for rehearsals. Working from a well-annotated printed speech, you will find it easier to practice and gradually learn the speech. (Of course, you should also be editing and revising as you rehearse.)

Your Turn: What’s Your Opinion?

Do you have any tips for marking up your speech so it is easier to read or learn?

is the editor and founder of Six Minutes. He teaches courses, leads seminars, coaches speakers, and strives to avoid Suicide by PowerPoint. He is an award-winning public speaker and speech evaluator. Andrew is a father and husband who resides in British Columbia, Canada.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Distinguish between four methods of speech delivery: the impromptu speech, the manuscript speech, the memorized speech, and the extemporaneous speech

- List the advantages and disadvantages of the four types of speeches

- Explain why an extemporaneous is the preferred delivery style when using rhetorical theory

- impromptu

- manuscript

- memorized

- extemporaneous

We have established that presentations involve much more than the transfer of information. Sure, you could treat a presentation as an opportunity to simply read a report you’ve written out loud to a group, but you would fail to both engage your audience and make a connection with them. In other words, you would leave them wondering exactly why they had to listen to your presentation instead of reading it at their leisure.

One of the ways to ensure that you engage your audience effectively is by carefully considering how best to deliver your speech. Each of you has sat in a class, presentation, or meeting where you didn’t feel interested in the information the presenter was sharing. Part of the reason for your disengagement likely originated in the presenter’s method of speech delivery.

For our purposes, there are four different methods—or types—of speech delivery used in technical communication:

What comes to mind when you think about the four methods of speech delivery? How do you think they are different from one another? Have you given a speech using any of these methods before?

Watch the video below for a brief overview of each one. After you are finished, answer the questions below:

- Which method are you most comfortable with? Why?

- Which method are you the least comfortable with? Why?

- Which method do you think is the best for connecting with your audience? Why?

The public speaking section of this course will require you to deliver a speech using an style, but let’s take a look at how all four differ in approach:

Impromptu Speeches

speaking is the presentation of a short message without advanced preparation. You have probably done impromptu speaking many times in informal, conversational settings. Self-introductions in group settings are examples of impromptu speaking: “Hi, my name is Shawnda, and I’m a student at the University of Saskatchewan.”

Another example of impromptu speaking occurs when you answer a question such as, “What did you think of the movie?” Your response has not been pre-planned, and you are constructing your arguments and points as you speak. Even worse, you might find yourself going into a meeting when your boss announces to you, “I want you to talk about the last stage of the project” with no warning.

The advantage of this kind of speaking is that it’s spontaneous and responsive in an animated group context. The disadvantage is that the speaker is given little or no time to contemplate the central theme of their message. As a result, the message may be disorganized and difficult for listeners to follow.

Here is a step-by-step guide that may be useful if you are called upon to give an impromptu speech in public:

- Take a moment to collect your thoughts and plan the main point that you want to make (like a mini thesis statement).

- Thank the person for inviting you to speak. Do not make comments about being unprepared, called upon at the last moment, on the spot, or uneasy. In other words, try to avoid being self-deprecating!

- Deliver your message, making your main point as briefly as you can while still covering it adequately and at a pace your listeners can follow.

- If you can use a structure, use numbers if possible: “Two main reasons. . .” or “Three parts of our plan. . .” or “Two side effects of this drug. . .” Past, present, and future or East Coast, Midwest, and West Coast are pre-fab structures.

- Thank the person again for the opportunity to speak.

- Stop talking. It is easy to “ramble on” when you don’t have something prepared. If in front of an audience, don’t keep talking as you move back to your seat.

Impromptu speeches are generally most successful when they are brief and focus on a single point.

We recommend practicing your impromptu speaking regularly. Do you want to work on reducing your vocalized pauses in a formal setting? Great! You can begin that process by being conscious of your vocalized fillers during informal conversations and settings.

Below are two examples of an speech. In the first video, a teacher is demonstrating an impromptu speech to his students on the topic of strawberries. He quickly jots down some notes before presenting.

What works in his speech? What could be improved?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/impromptuteacher

In the above example, the teacher did an okay job, considering how little time he had to prepare.

In this next example, you will see just how badly an impromptu speech can go. It is a video of a best man speech at a wedding. Keep in mind that the speaker is the groom’s brother.

Is there anything that he does well? What are some problems with his speech?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/badimpromptubestman

Manuscript Speeches

speaking is the word-for-word iteration of a written message. In a manuscript speech, the speaker maintains their attention on the printed page except when using presentation aids.

The advantage to reading from a manuscript is the exact repetition of original words. This can be extremely important in some circumstances. For example, reading a statement about your organization’s legal responsibilities to customers may require that the original words be exact. In reading one word at a time, in order, the only errors would typically be the mispronunciation of a word or stumbling over complex sentence structure. A manuscript speech may also be appropriate at a more formal affair (like a funeral), when your speech must be said exactly as written in order to convey the proper emotion the situation deserves.

However, there are costs involved in manuscript speaking. First, it’s typically an uninteresting way to present. Unless the speaker has rehearsed the reading as a complete performance animated with vocal expression and gestures (well-known authors often do this for book readings), the presentation tends to be dull. Keeping one’s eyes glued to the script prevents eye contact with the audience.

For this kind of “straight” manuscript speech to hold audience attention, the audience must be already interested in the message and speaker before the delivery begins. Finally, because the full notes are required, speakers often require a lectern to place their notes, restricting movement and the ability to engage with the audience. Without something to place the notes on, speakers have to manage full-page speaking notes, and that can be distracting.

It is worth noting that professional speakers, actors, news reporters, and politicians often read from an autocue device such as a teleprompter. This device is especially common when these people appear on television where eye contact with the camera is crucial. With practice, a speaker can achieve a conversational tone and give the impression of speaking extemporaneously and maintaining eye contact while using an autocue device.

However, success in this medium depends on two factors:

- the speaker is already an accomplished public speaker who has learned to use a conversational tone while delivering a prepared script, and

- the speech is written in a style that sounds conversational.

Below is a video that shows an example of a manuscript speech. In the video, US Presidential Historian, Doris Kearns Goodwin, gives a speech about different US presidents.

What works in her speech? What could be improved?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/goodwindepauw

Here’s a video that shows the dangers of relying on a manuscript for your speech:

Michael Bay heavily relied on his , so when he suddenly lost access to it, he was left feeling embarrassed and had to hastily leave the stage. As a result, he experienced .

Link to original video: https://tinyurl.com/MBayManuscript

Memorized Speeches

speaking is reciting a written message that the speaker has committed to memory. Actors, of course, recite from memory whenever they perform from a script in a stage play, television program, or movie. When it comes to speeches, memorization can be useful when the message needs to be exact and the speaker doesn’t want to be confined by notes.

The advantage to memorization is that it enables the speaker to maintain eye contact with the audience throughout the speech. Being free of notes means that you can move freely around the stage and use your hands to make gestures. If your speech uses presentation aids, this freedom is even more of an advantage.

Memorization, however, can be tricky. First, if you lose your place and start trying to ad lib, the contrast in your style of delivery will alert your audience that something is wrong. If you go completely blank during the presentation, it will be extremely difficult to find your place and keep going. Obviously, memorizing a typical seven-minute classroom speech takes a great deal of time and effort, and if you aren’t used to memorizing, it is very difficult to pull off.

Below is a video that shows an example of a memorized speech. In the video, former Louisiana governor, Bobby Jindal, responds to Barack Obama’s State of the Union address back in 2009.

What works in his speech? What could be improved?

speaking is the presentation of a carefully planned and rehearsed speech, spoken in a conversational manner using brief notes.

Speaking extemporaneously has some advantages. It promotes the likelihood that you, the speaker, will be perceived as knowledgeable and credible since you know the speech well enough that you don’t need to read it. In addition, your audience is likely to pay better attention to the message because it is engaging both verbally and nonverbally.

By using notes rather than a full manuscript (or everything that you’re going to say), the extemporaneous speaker can establish and maintain eye contact with the audience and assess how well they are understanding the speech as it progresses. It also allows flexibility; you are working from the strong foundation of an outline, but if you need to delete, add, or rephrase something at the last minute or to adapt to your audience, you can do so. The outline also helps you be aware of main ideas vs. subordinate ones.

Compared to the other three types of speech delivery, an extemporaneous style is the best for engaging your audience and making yourself sound like a natural speaker.

The video below provides some tips on how to deliver a speech using this method:

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/deliverextempres

The slide below provides a brief overview of tips for preparing your extemporaneous presentation:

Below is a video that shows an example of an speech. In the video, a former University of Saskatchewan student tries to persuade her peers to spend more solo time outside.

What works in her speech? What could be improved?

Link to Original Video: tinyurl.com/rcm401speech

- When designing any speech, it’s important to consider how you will deliver that speech. In technical communication, there are four different types of speech delivery, each with their advantages and disadvantages. They are: , , , and .

- An impromptu speech can take many forms such as a toast at a wedding, being asked to give a project update at a meeting, or even simply meeting someone for the first time. While this type of speech can be spontaneous and responsive, the speaker generally has little to no warning that they will need to speak.

- A manuscript speech is completely written out and read word for word. It is often a good style when you want to nail the specific wording and do not want to make an error. However, this type of speech is not very persuasive because it does not take advantage of the immediacy of public speaking. It also completely removes audience relation from the process.

- A memorized speech is when a speaker commits an entire speech to memory. This style also harms relation with the audience because the speaker is more focused on remembering the text of the speech rather than communicating with the audience. Additionally, if you lose your place and need to ad lib, it may be obvious to your audience.

- An extemporaneous speech is done in a natural, conversational speaking style. While it is carefully planned, it is never completely written out like a manuscript. It is also not read or memorized. Instead, an outline is used to help guide the speaker. As a result, more attention can be paid to the audience, allowing the speaker to better connect with them and make adjustments as necessary. This is the style we want you to use for your presentation assignment in RCM 200.

Attributions

This chapter is adapted from “Communication for Business Professionals” by eCampusOntario (on Open Library). It is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This chapter is also adapted from “Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy” by Meggie Mapes (on Pressbooks). It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.