Where the word “dollar” came from

Surprise! Surprise! The word “dollar” has German origin and is much older than the USA and its currency! In 1516 in Bohemia, in a place called “Joachimsthal” (which means “Joachim’s valley”) a silver mine was opened, and they started to produce coins known as “Joachimsthalers”. This long word was soon shortened to “thalers” and called “dalers” by the Dutch. The English changed this word to “dollar” and began to use it when speaking of any large silver foreign coin. In North America, for instance, English settlers referred to the Spanish piece of eight reals as the “Spanish dollar”.

(отрывок из текста)

Откуда произошло слово «доллар»

Сюрприз! Сюрприз! Слово «доллар» имеет немецкое происхождение и намного старше, чем США и их валюта! В 1516 году в Чехии, в месте под названием «Joachimsthal» (что означает «долина Иоахима») был открыт серебряный рудник, и они начали выпускать монеты, известные как «Joachimsthalers». Это длинное слово вскоре сокращено до «талера», голландцы говорили «далер». Англичане изменили это слово на «доллар» и начали использовать его, когда речь шла о какой-либо большой серебряной иностранной монете. В Северной Америке, например, английские поселенцы называли испанские восемь реалов — «испанский доллар».

В течение нескольких лет после получения независимости американцы не имели свою собственную валюту, они использовали любые иностранные монеты, которые могли получить, включая испанские доллары. Но они понимали, что новой нации нужна своя валюта. Томас Джефферсон решительно возражал против использования английской системы. Это была его идея назвать американские деньги «доллары», словом, которое было уже знакомо людям. Доллар был официально объявлен денежной единицей США в 1785 году.

Say if the following statements are true, false or not stated. – Скажите, верны ли следующие утверждения, ложные или не указано.

1. According to the text, the word “thaler” is connected with a certain place name. — В соответствии с текстом, слово «талер» связано с название определенного места.

a) true b) false c) not stated

2. The Dutch brought German thalers to Britain. — Голландцы принесли немецкие талеры в Великобританию.

a) true b) false c) not stated

3. In English the word “dollar” was at first used to describe any silver coin. — В английском языке слово «доллар» сначала было использовано для описания любой серебряной монеты.

a) true b) false c) not stated

4. Thomas Jefferson wanted the US to have their own currency. — Томас Джефферсон хотел, чтобы США имели свою собственную валюту.

a) true b) false c) not stated

5. According to the text, for 9 years the USA didn’t have currency of their own. — В соответствии с текстом, в течение 9 лет США не имели свою собственную валюту.

a) true b) false c) not stated

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the name used for currencies. For the currency used in the United States of America, see United States dollar. For other uses, see Dollar (disambiguation).

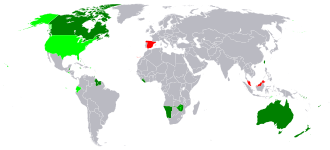

Countries or territories that use a non-US currency named dollar

Countries that formerly used a dollar currency

The Joachimsthaler of the Kingdom of Bohemia was the first thaler (dollar).

Dollar is the name of more than 20 currencies. The United States dollar, named after the international currency known as the Spanish dollar, was established in 1792 and is the first so named that still survives. Others include the Australian dollar, Brunei dollar, Canadian dollar, Eastern Caribbean dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Jamaican dollar, Liberian dollar, Namibian dollar, New Taiwan dollar, New Zealand dollar, Singapore dollar, Trinidad and Tobago Dollar and several others. The symbol for most of those currencies is the dollar sign $ in the same way as many countries using peso currencies. The name «dollar» originates from Bohemia and a 29 g silver-coin called the Joachimsthaler.

Economies that use a «dollar»[edit]

| Currency | ISO 4217 code | Country or territory | Established | Preceding currency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | 1965 | British West Indies dollar | |

| Australian dollar | AUD | 1966-02-14 | Australian pound 1910-1966 Pound sterling 1825-1910 |

|

| Bahamian dollar | BSD | 1966 | Bahamian pound | |

| Barbadian dollar | BBD | 1972 | Eastern Caribbean dollar | |

| Belize dollar | BZD/USD | 1973 | British Honduran dollar | |

| Bermudian dollar | BMD | 1970 | Pound sterling | |

| Brunei dollar

(Alongside the Singapore dollar) |

BND

(SGD) |

1967 | Malaya and British Borneo dollar | |

| Canadian dollar | CAD | 1858 | Spanish dollar pre-1841 Canadian pound 1841–1858 Newfoundland dollar 1865–1949 in the Dominion of Newfoundland |

|

| Cayman Islands dollar | KYD | 1972 | Jamaican dollar | |

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | 1965 | British West Indies dollar | |

| United States dollar | USD | 2002 | Indonesian rupiah | |

| United States dollar | USD | 2001 | Ecuadorian sucre | |

| United States dollar | USD | 2001 | Salvadoran colón | |

| Fijian dollar | FJD | 1969 | Fijian pound | |

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | 1965 | British West Indies dollar | |

| Guyanese dollar | GYD | 1839 | Eastern Caribbean dollar | |

| Hong Kong dollar | HKD | 1863 | Rupee, Real (Spanish/Colonial Spain: Mexican), Chinese cash | |

| Jamaican dollar | JMD | 1969 | Jamaican pound | |

| Kiribati dollar along with the Australian dollar | KID / AUD | 1979 | Australian dollar | |

| Liberian dollar | LRD | 1937 | United States dollar | |

| United States dollar | USD | |||

| United States dollar | USD | |||

| Namibian dollar along with the South African rand | NAD | 1993 | South African rand | |

| Australian dollar | AUD | 1966 | ||

| New Zealand dollar | NZD | 1967 | New Zealand pound | |

| United States dollar | USD | |||

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | 1965 | ||

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | |||

| Eastern Caribbean dollar | XCD | |||

| Singapore dollar

(Alongside the Brunei dollar) |

SGD

(BND) |

1967 | Malaya and British Borneo dollar | |

| Solomon Islands dollar | SBD | 1977 | Australian pound | |

| Surinamese dollar | SRD | 2004 | Surinamese guilder | |

| New Taiwan dollar | TWD | 1949 | Old Taiwan dollar | |

| Trinidad and Tobago dollar | TTD | 1964 | British West Indies dollar | |

| Tuvaluan dollar along with the Australian dollar | TVD / AUD | 1976 | ||

| United States dollar | USD | 1792 | Spanish dollar colonial scrip |

|

| Dolar West

Papua[1] |

IDX | Indonesia | 1949 | Gulden Netherlands Indonesian rupiah (1969-present now) |

Other territories that use a «dollar»[edit]

Countries unofficially accepting «dollars»[edit]

Countries and regions that have previously used a «dollar» currency[edit]

- Confederate States of America: The Confederate States dollar issued from March 1861 to 1865

- Ethiopia: The name «Ethiopian dollar» was used in the English text on the birr banknotes before the Derg takeover in 1974.

- Malaysia: the Malaysian ringgit used to be called the «Malaysian Dollar». The surrounding territories (that is, Malaya, British North Borneo, Sarawak, Brunei, and Singapore) used several varieties of dollars (for example, Straits dollar, Malayan dollar, Sarawak dollar, British North Borneo dollar; Malaya and British Borneo dollar) before Malaya, British North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore and Brunei gained their independence from the United Kingdom. See also for complete list of currencies.

- Sierra Leone: The Sierra Leonean dollar was used from 1791 to 1805. It was subdivided into 100 cents and was issued by the Sierra Leone Company. The dollar was pegged to sterling at a rate of 1 dollar = 4 shillings 2 pence.

- Spain: the Spanish dollar was used from 1497 to 1868. It is closely related to the dollars (Spanish dollar was used in the US until 1857) and euros used today.[clarification needed]

- Sri Lanka; the Ceylonese rixdollar was a currency used in British Ceylon in the early 19th Century.

- Rhodesia: the Rhodesian dollar replaced the Rhodesian pound in 1970 and it was used until Zimbabwe came into being in 1980.

- Republic of Texas: the Texas dollar was issued between January 1839 and September 1840.

- Zimbabwe: uses the Zimbabwe dollar,and also accepts the South African rand, the US dollar,[10] the Euro, the Pound sterling, the Botswana pula, the Chinese yuan, the Indian rupee and the Japanese yen.[11]

History[edit]

Etymology[edit]

On 15 January 1520, the Kingdom of Bohemia began minting coins from silver mined locally in Joachimsthal and marked on reverse with the Bohemian lion. The coins would be named Joachimsthaler after the town, becoming shortened in common usage to thaler or taler. The town itself derived its name from Saint Joachim, coupled with the German word Thal (Tal in modern spelling) means ‘valley’ (cf. the English term dale).[12]

This name found its way into other languages, for example:[13]

- German — Thaler (or Taler)

- Czech, Slovak and Slovenian — tolar

- Slovak — toliar

- Polish — talar

- Low German — daler

- Dutch — rijksdaalder (or daler),

- Danish and Norwegian — rigsdaler

- Swedish — riksdaler

- Spanish — dólar (or real de a ocho or peso duro)

- Hungarian — tallér

- Ethiopian — talari (ታላሪ)

- English — dollar

In contrast to other languages which adopted the second part of word joachimsthaler, the first part found its way into Russian language and became efimok [ru], yefimok (ефимок).[14]

The predecessor of the Joachimsthaler was the Guldengroschen or Guldiner which was a large silver coin originally minted in Tirol in 1486, but which was introduced into the Duchy of Saxony in 1500. The King of Bohemia wanted a similar silver coin which then became the Joachimsthaler.

Europe and colonial North America[edit]

The Joachimsthaler of the 16th century was succeeded by the longer-lived Reichsthaler of the Holy Roman Empire, used from the 16th to 19th centuries. The Netherlands also introduced its own dollars in the 16th century: the Burgundian Cross Thaler (Bourgondrische Kruisdaalder), the German-inspired Rijksdaalder, and the Dutch liondollar (leeuwendaalder). The latter coin was used for Dutch trade in the Middle East, in the Dutch East Indies and West Indies, and in the Thirteen Colonies of North America.[15]

For the English North American colonists, however, the Spanish peso or «piece of eight» has always held first place, and this coin was also called the «dollar» as early as 1581. Spanish dollars or «pieces of eight» were distributed widely in the Spanish colonies in the New World and in the Philippines.[16][17][18][19][20]

Origins of the dollar sign[edit]

The sign is first attested in business correspondence in the 1770s as a scribal abbreviation «ps«, referring to the Spanish American peso,[21][22] that is, the «Spanish dollar» as it was known in British North America. These late 18th- and early 19th-century manuscripts show that the s gradually came to be written over the p developing a close equivalent to the «$» mark, and this new symbol was retained to refer to the American dollar as well, once this currency was adopted in 1785 by the United States.[23][24][25][26][27]

Adoption by the United States[edit]

By the time of the American Revolution, the Spanish dólar gained significance because they backed paper money authorized by the individual colonies and the Continental Congress.[17] Because Britain deliberately withheld hard currency from the American colonies, virtually all the non-token coinage in circulation was Spanish (and to a much lesser extent French and Dutch) silver, obtained via illegal but widespread commerce with the West Indies. Common in the Thirteen Colonies, Spanish dólar were even legal tender in one colony, Virginia.

On April 2, 1792, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton reported to Congress the precise amount of silver found in Spanish dollar coins in common use in the states. As a result, the United States dollar was defined[28] as a unit of pure silver weighing 371 4/16th grains (24.057 grams), or 416 grains of standard silver (standard silver being defined as 371.25/416 in silver, and balance in alloy).[29] It was specified that the «money of account» of the United States should be expressed in those same «dollars» or parts thereof. Additionally, all lesser-denomination coins were defined as percentages of the dollar coin, such that a half-dollar was to contain half as much silver as a dollar, quarter-dollars would contain one-fourth as much, and so on.

In an act passed in January 1837, the dollar’s weight was reduced to 412.5 grains and alloy at 90% silver, resulting in the same fine silver content of 371.25 grains. On February 21, 1853, the quantity of silver in the lesser coins was reduced, with the effect that their denominations no longer represented their silver content relative to dollar coins.

Various acts have subsequently been passed affecting the amount and type of metal in U.S. coins, so that today there is no legal definition of the term «dollar» to be found in U.S. statute.[30][31][32] Currently the closest thing to a definition is found in United States Code Title 31, Section 5116, paragraph b, subsection 2: «The Secretary [of the Treasury] shall sell silver under conditions the Secretary considers appropriate for at least $1.292929292 a fine troy ounce.»

Silver was mostly removed from U.S. coinage by 1965 and the dollar became a free-floating fiat money without a commodity backing defined in terms of real gold or silver. The US Mint continues to make silver $1-denomination coins, but these are not intended for general circulation.

Usage in the United Kingdom[edit]

There are two quotes in the plays of William Shakespeare referring to dollars as money. Coins known as «thistle dollars» were in use in Scotland during the 16th and 17th centuries,[33] and use of the English word, and perhaps even the use of the coin, may have begun at the University of St Andrews[34] This might be supported by a reference to the sum of «ten thousand dollars» in Macbeth (act I, scene II) (an anachronism because the real Macbeth, upon whom the play was based, lived in the 11th century). In the Sherlock Holmes story «The Man with the Twisted Lip» by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, published in 1891,[35][circular reference] an Englishman posing as a London beggar describes the shillings and pounds he collected as dollars.

In 1804, a British five-shilling piece, or crown, was sometimes called «dollar». It was an overstruck Spanish eight real coin (the famous «piece of eight»), the original of which was known as a Spanish dollar. Large numbers of these eight-real coins were captured during the Napoleonic Wars, hence their re-use by the Bank of England. They remained in use until 1811.[36][37] During World War II, when the U.S. dollar was (approximately) valued at five shillings, the half crown (2s 6d) acquired the nickname «half dollar» or «half a dollar» in the UK.

Usage elsewhere[edit]

Chinese demand for silver in the 19th and early 20th centuries led several countries, notably the United Kingdom, United States and Japan, to mint trade dollars, which were often of slightly different weights from comparable domestic coinage. Silver dollars reaching China (whether Spanish, trade, or other) were often stamped with Chinese characters known as «chop marks», which indicated that that particular coin had been assayed by a well-known merchant and deemed genuine.

Other national currencies called «dollar»[edit]

Prior to 1873, the silver dollar circulated in many parts of the world, with a value in relation to the British gold sovereign of roughly $1 = 4s 2d (21p approx). As a result of the decision of the German Empire to stop minting silver thaler coins in 1871, in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, the worldwide price of silver began to fall.[38] This resulted in the U.S. Coinage Act (1873) which put the United States onto a ‘de facto’ gold standard. Canada and Newfoundland were already on the gold standard, and the result was that the value of the dollar in North America increased in relation to silver dollars being used elsewhere, particularly Latin America and the Far East. By 1900, value of silver dollars had fallen to 50 percent of gold dollars. Following the abandonment of the gold standard by Canada in 1931, the Canadian dollar began to drift away from parity with the U.S. dollar. It returned to parity a few times, but since the end of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that was agreed to in 1944, the Canadian dollar has been floating against the U.S. dollar. The silver dollars of Latin America and South East Asia began to diverge from each other as well during the course of the 20th century. The Straits dollar adopted a gold exchange standard in 1906 after it had been forced to rise in value against other silver dollars in the region. Hence, by 1935, when China and Hong Kong came off the silver standard, the Straits dollar was worth 2s 4d (11.5p approx) sterling, whereas the Hong Kong dollar was worth only 1s 3d sterling (6p approx).

The term «dollar» has also been adopted by other countries for currencies which do not share a common history with other dollars. Many of these currencies adopted the name after moving from a £sd-based to a decimalized monetary system. Examples include the Australian dollar, the New Zealand dollar, the Jamaican dollar, the Cayman Islands dollar, the Fiji dollar, the Namibian dollar, the Rhodesian dollar, the Zimbabwe dollar, and the Solomon Islands dollar.

- The tala is based on the Samoan pronunciation of the word «dollar».

- The Slovenian tolar had the same etymological origin as dollar (that is, thaler).

- The Swedish Daler used to be the name for the currency and have the same etymological origin as the German thaler).

See also[edit]

- Canadian Tire money

- Disney Dollars

- Eurodollar

- List of circulating currencies

- North American currency union Amero

- Petrodollar

References[edit]

- ^ Rupiah is often used/dollars are rarely used?

- ^ Torres, Andrea (17 July 2020). «Cuba to accept U.S. dollars at government stores». Local 10.

- ^ Estrada, Oscar Fernandez (8 November 2019). «Return to the US Dollar in Cuba: What about the CUC?». Havana Times.

- ^ Kornbluh, Peter. «Cuba Is Getting Rid of the CUC». Cigar Aficionado.

- ^ «Can I Use U.s. Dollars To Make Purchases In Cuba?». Insight Cuba.

- ^ Robinson, Circles (30 August 2020). «US Dollar Taking Over in Cuba as CUC Plummets». Havana Times.

- ^ Wojtanik, Andrew (2005). Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. p. 147.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (2015). The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-939003-8.

- ^ Although called Panamanian balboas, US dollars circulate as official currency, since there are no Balboa bills, only coins that are the same size, weight and value as their US counterparts.

- ^ Adopted for all official government transactions

- ^ Hungwe, Brian. «Zimbabwe’s multi-currency confusion», BBC News, Harare, 6 February 2014. Retrieved on 5 November 2016.

- ^ Welcome to Jáchymov: the Czech town that invented the dollar. The tiny town of Jáchymov was just named one of Unesco’s newest World Heritage sites Five hundred years after coining the first dollar, a tiny mining town is coming to grips with the many ways it shaped the modern world. bbc.com.

- ^ «Why Is The Dollar Sign A Letter S?». Observation Deck. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- ^ «Талер, доллар, ефимок — Троицкий вариант — Наука». 20 June 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ «Lion Dollar — Introduction». coins.nd.edu.

- ^ Rabushka, Alvin (16 December 2010). Taxation in Colonial America. ISBN 978-1400828708. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ a b Julian, R.W. (2007). «All About the Dollar». Numismatist: 41.

- ^ Cross, Bill (2012). Dollar Default: How the Federal Reserve and the Government Betrayed Your Trust. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781475261080.

- ^ National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1. Ask Us.

- ^ Vries, Jan de; Woude, Ad van der (28 May 1997). The First Modern Economy. ISBN 9780521578257. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Lawrence Kinnaird (July 1976). «The Western Fringe of Revolution,» The Western Historical Quarterly 7(3), 259. JSTOR 967081

- ^ «Origin of Dollar Sign is Traced to Mexico», Popular Science, 116 (2): 59, 1930, ISSN 0161-7370

- ^ Florian Cajori ([1929]1993). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol. 2), 15-29.

- ^ Arthur S. Aiton and Benjamin W. Wheeler (May 1931). «The First American Mint», The Hispanic American Historical Review 11(2), 198 and note 2 on 198. JSTOR 2506275

- ^ Nussbaum, Arthur (1957). A History of the Dollar. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 56.

- ^ Riesco Terrero, Ángel (1983). Diccionario de abreviaturas hispanas de los siglos XIII al XVIII: Con un apendice de expresiones y formulas juridico-diplomaticas de uso corriente. Salamanca: Imprenta Varona, 350. ISBN 84-300-9090-8

- ^ Bureau of Engraving and Printing. «‘What is the origin of the $ sign?’ in FAQ Library». Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Act of April 2, A.D. 1792 of the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Section 9.

- ^ Section 13 of the Act.

- ^ United States Statutes at Large.

- ^ Yeoman, RS (1965). A Guide Book of United States Coins.

- ^ Ewart, James E. Money — Ye shall have honest weights and measures.

- ^ Herbert Appold Grueber (January 1999). Handbook of the Coins of Great Britain and Ireland in the British Museum. ISBN 9781402110900.

- ^ Michael, T.R.B. Turnbull (30 July 2009). «Saint Andrew». BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ The Man with the Twisted Lip

- ^ All Things Austen: An Encyclopedia of Austen’s World ISBN 0-313-33034-4 p. 444

- ^ «The Coinage of Britain — Milled Coins 1662-1816». www.kenelks.co.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ «Monetary Madhouse, Charles Savoie, 2005». Silver-investor.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dollar.

- Etymonline (word history). for buck; Etymonline (word history) for dollar

- Currency converter. CNNMoney.com

Many people are fascinated by etymology, and will happily spend a large amount of time tracing some specific word’s history, looking back through hundreds of years of history in search of lexical information. While we are always happy to see people indulge their passion for language, we must also say that in many cases the story of a word’s history is likely to be a rather dry affair. If you are at a dinner party, and someone tries to engage you in small talk by telling you the interesting story of a word such as posh there is a good chance that the word’s history will not actually be as supposed.

The ‘dollar’ is known throughout the world, but the word’s origin story begins hundreds of years ago in a small town in Bohemia.

However, there are thousands and thousands of English words with great backstories. Take, for instance, the humble dollar: why do we call our basic unit of currency by this name?

It all begins, logically enough (if you accept a somewhat loose definition of “logically”), in a small mountain town in northwestern Bohemia, named Jáchymov. In the beginning of the 16th century this town (located in what today is the Czech Republic) was known by its German name, Sankt Joachimsthal, which may be translated as “dale (or valley) of Joachim.” This may not seem yet like it allows a logical path to the modern dollar, but it will.

About the beginning of the 16th century the Count of Schlick (a name that comes from genuine history books, and not from a Lemony Snicket novel) opened a mine in this town, and from its ore began to mint and issue a good amount of silver coin. William Lyman Fawcett, in his Gold and Debt; an American Handbook of Finance (1879) informs us that these coins were “of uniform weight and fineness” and that “traders of the time were in want of some international standard,” and so “these coins soon became in good repute all over Europe under the names of Schlicken thalers or Joachim’s thalers.”

The second of these names, more often written as joachimstaler, appeared to have had more success than did schlicken thaler, although it did not last for a terribly long time. Soon the name of this coin became shortened to the German taler, and from there became daler. By the middle of the 16th century the English language had added daler to its vocabulary, used in reference to an increasing variety of coins from Europe and elsewhere which were being so described.

The dollar was proposed as the monetary unit of the United States in the early 1780s, and adopted formally in 1792 (although they were not actually issued as currency until 1794). Since that time our language has taken on a remarkable number of synonyms for this word for “100 cents,” often found in the form of slang. We have paid for things with bones, bucks, smackers (and smackeroos), clams, iron men (for silver dollars), plunks, and simoleons.

Although the list of slang and colloquial terms for the dollar (and other denominations of our currency, such as Benjamin for the $100 bill, which bears the portrait of Benjamin Franklin) is long and quite creative, we are sad to report that the word based on the long-dead Count appears to have been largely overlooked. If you are of a mind to try to introduce a new bit of slang for the dollar, and would like to spice your coinage with a degree of historical flair you could certainly do worse than schlickenthaler.

The US dollar was officially launched by America’s Continental Congress on September 8, 1786. However, the dollar can trace its roots all the way back to 16th century Bavaria.

How did the US dollar come to be one of the world’s largest and most widely-accepted currencies? Where does the value of the US dollar come from? And where is the dollar going in the future? Today, we’re explaining everything you need to know about the history of the dollar.

The Dollar Originated in Bavaria in 1518

If you asked someone where the US dollar first began, they would probably guess America.

But that’s not entirely true. Many historians place the beginnings of the dollar to a small town in Bavaria. In 1518, that town began issuing standardized silver coins using silver from a nearby mine.

These coins were issued at a standardized weight of 29.2 grams. The coins were called “thalers” because “thal” means “valley” in German, and the coins came from a valley. Get it?

Countries across Europe soon came to recognize the value of a standardized currency system. Countries adopted the standardized thaler coin from commerce. Different governments used different silver and different production methods, but all the thalers were virtually identical.

Europe was on a “thaler” standard. You don’t have to change the pronunciation of “thaler” very much to get “dollar” – which is where the name dollar would eventually come from.

The Spanish Silver Dollar

As the Old World began to explore the New World, the thaler or dollar became more and more ubiquitous.

Spanish explorers discovered rich mines in Mexico and other new colonies. They used these mines to produce the Spanish silver dollar. In just years, the Spanish silver dollar became the most common coin in all of the American colonies

Despite its ubiquity, the Spanish silver dollar was far from the only coin in the colonies: silver dollars from the Old World continued to be used throughout the Americas. This tended to complicate transactions at the time – which is why the US began to fight to adopt a standardized currency.

America Before the US Dollar

Before America was officially a country, the colonies had to use something as a currency.

The origins of money in America can be traced back to 17th century Massachusetts. In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony used paper notes to finance military expeditions. Seeing the success of this system, other US colonies quickly followed.

The British eventually imposed restrictions on these early colonial paper currencies. In 1775, when anti-British sentiment was rising, the Continental Congress would choose the Continental currency as its official standard. That currency, however, would not last very long. It did not have sufficient financial backing and the notes were too easy to counterfeit.

The US Congress Adopts the Thaler As Its First Official National Currency

Soon after the American Revolution, US Congress had a big decision to make: what would the young country use at its official currency?

In 1785, US Congress decided to adopt the European thaler as the standard across America. At this point, the original German word “thaler” was being replaced by the Anglicized “dollar”. The two were pronounced in a very similar way.

The Coinage Act of 1792 solidified the US dollar as the nation’s official currency: that act implemented an organized monetary system featuring gold, silver and copper.

The U.S. dollar was slightly lighter than the original thalers used throughout the Old World: it weighed in at 27 grams of silver.

1861 and the Civil War

The US Civil War took place between 1861 and 1865. At this time, America realized a major problem: it needed money to fight the war, but it only had a finite amount of gold, silver, and copper reserves.

Thus, America began to issue paper notes or greenbacks into the system started in 1861 to help finance the Civil War.

Of course, paper notes were easier to counterfeit than traditional metal coins. Around this time, the US treasury began implementing different counterfeit-fighting measures – including a Treasury seal and engraved signatures.

By 1863, Congress had introduced a national banking system that granted the US Treasury permission to oversee the issuance of National Bank notes. This gave national banks the power to distribute money and purchase US bonds more easily while still being regulated.

Federal Reserve Act of 1913

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 created one central bank and introduced a national banking system. The goals of these two entities were to keep up with the rapidly changing financial needs of the country.

The Federal Reserve Board would eventually create a new currency called the Federal Reserve Note. The first “Note” introduced was a ten dollar bill, introduced in 1914.

The Federal Reserve Board decided to implement two major changes to the design of the bills:

- The Board decided to reduce the size of the notes by 30% to lower manufacturing costs

- The same designs were printed on all denominations, once again to save manufacturing costs

The design of the US bills would not change until 1996, when rampant counterfeiting forced the US to implement a series of security improvements.

Nevertheless, the US dollar remains a unique currency to this day for having virtual identical designs across its bill denominations in terms of size, shape, and color.

The Relationship Between Silver and Gold

You may have noticed that the thaler or dollar was originally built on the price of silver. However, most of us associate the value of modern currencies like the US dollar with the price of gold.

When did things change?

Well, silver and gold traded at virtually identical ratios throughout history. This was known as the “bimetallic” system of trading. Over the centuries, one ounce of gold was consistently worth about 15 or 16 ounces of silver.

Because the “thaler” system standardized the price of silver, it also, by extension, standardized the price of gold.

Gold was eventually viewed as the more stable commodity and became a more favored indicator of currency value. Britain would eventually throw out the old bimetallic system in 1816, replacing it with the monometallic system. The United States followed suit in 1834 (although the monometallic system would not be officially implemented until 1900).

In 1834, the United States passed the 1834 Coinage Act. This act locked the value of the U.S. dollar to $20.67 per ounce of gold. Each dollar was worth about 1.5048 grams of gold.

It’s easier to visualize the importance of these changes when looking at a graph. In the graph below, you can see that the “dollar” or “thaler” was an unchanging unit of value for most of 415 years, only changing in 1933:

Photo courtesy of HuffingtonPost.com

As you can see, there are several major dips in the graph. In the 1780s, the American colonies experienced a wave of hyperinflation. After the Civil War, there was another hyperinflation problem. However, after these minor inflation problems, the nation would always turn to the stable gold dollar.

That long-standing standardized value of the gold US dollar would change forever in 1933, as you can see by the sudden upheaval of the graph above.

The US Dollar Becomes Permanently Devalued in 1933

So what happened to change the dollar in 1933? In 1933, America was in the heart of the Great Depression. In an effort to spur the economy, America reduced its dollar value to $35 per ounce. One dollar was worth about 0.8887 grams of gold.

The Dollar is Devalued Again in 1971

Starting in 1971, the US dollar would be taken on another ride that would forever change its fate. Nixon’s “easy money” policies of the 1970s led to floating exchange rates. The dollar would lose about 90% of its value relative to gold, eventually stabilizing around $350 per ounce in the 1980s and 1990s.

The “Great Moderation” period, as this is called by some economists, somewhat continues to this day. We take floating exchange rates and currency fluctuations for granted: they’re just part of a global economy.

However, in reality, we’re in the middle of a great experiment – the end results of which have yet to be seen. Some argue that we’ll return to a stable global currency in the future, as it was the basis on which capitalist economies around the world were made.

Who Uses the US Dollar?

The United States dollar is the official currency of the United States. However, it’s also the world’s most common reserve currency. More governments around the world hold US dollars than any other type of currency.

At the same time, certain countries around the world use the US dollar as either their official currency or their de-facto currency. Other countries peg the value of their currency to the US dollar.

Countries and Territories That Use the US Dollar as Their Official Medium of Exchange:

- United States of America

- Puerto Rico

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Zimbabwe

- Guam

- US Virgin Islands

- Timor-Leste (East Timor)

- American Samoa

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Federated States of Micronesia

- Palau

- Marshall Islands

- British Virgin Islands

- Turks and Caicos

There are certain unique situations on this list. Zimbabwe, for example, experienced disastrous hyperinflation throughout much of the last few decades. In 2009, the country chose to abandon its own currency and adopt eight new currencies as its official legal tender. The United States dollar is now an official currency in the country along with the South African rand, the Botswana pula, the British pound sterling, the Australian dollar, the Chinese yuan, the Indian rupee, and the Japanese yen.

Countries Where the US Dollar is Commonly Used

The countries above use the US dollar as one of their official currencies (often as the official currency).

However, there are a number of other countries where the US dollar is viewed as a “quasi-currency” of exchange. For example, the US dollar is widely accepted by retailers in Canada and Mexico. It’s also commonly used at tourist destinations around the world – particularly tourist destinations that host many Americans.

Popular tourist destinations that accept the US dollar as a de facto-currency include the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Sint Maarten, St Kitts and Nevis, Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba. As you may have noticed, all of these islands are found in or around the Caribbean.

The Caribbean isn’t the only region that uses US dollars as a quasi-currency. You can also widely use the US dollar in Belize, Panama, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua.

Over the years, the US dollar has also been gaining ground in certain Asian nations. You will likely have success using your US dollar in the Philippines, for example, along with Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, and Vietnam (particularly in the major cities of Vietnam).

There are also certain outlier countries – like Africa’s Liberia – that widely accept US dollars. The Old City of Jerusalem also accepts US dollars.

Dollars in Other Countries

The United States isn’t the only country that uses the term “dollar” for its official currency. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand all use the dollar as the official medium of exchange.

Since this article is a “history of the dollar”, it seems appropriate to briefly explain the history of these currencies as well.

The Canadian Dollar

When Canada was a British colony, traders mostly used the pound sterling. Inevitably, the young country of Canada did plenty of business with its southern neighbor. This led to pressure to switch from the pound sterling to a decimal-based currency similar to the American one.

Trading between the pound sterling and the US dollar was problematic because the pound sterling divided pounds into 20 shillings, and then divided the shilling into 12 pence.

Thus, there was widespread support to switch to a decimal-based system of currency to facilitate trading between Canada and America.

The British government agreed that this seemed reasonable. Between 1853 and 1857, the Province of Canada (it wasn’t an official country until 1867) would gradually switch over to its own system of Canadian dollars and cents.

Surprisingly, Canada held little autonomy over its currency in the early days of confederation: the Canadian dollar was minted in Britain until 1908, when Canada built its own Ottawa Mint.

The Australian Dollar

Canada adopted its own native currency prior to becoming a country. Australia, however, took a different route: Australia continued using the pound sterling for about 50 years after it gained its independence from Britain (Australia achieved confederation in 1901).

Like the Canadians, however, the Aussies found the pound, shilling, and pence system cumbersome. By the 1960s, Australia had replaced the Australian pound with the Australian dollar. The new Australian dollar was worth 0.5 Australian pounds. In other words, one Australian pound was now worth two Australian dollars.

The UK, by the way, would eventually decimalize its currency and get rid of the old shilling and pence system in 1971.

The New Zealand Dollar

New Zealand, similar to Australia, used the pound for decades after gaining its independence. In 1967, New Zealand began using its own dollar. Nearby countries like Fiji and the Solomon Islands would eventually adopt the New Zealand dollar as their official national currencies.

Today, Pacific island nations typically use the Australia, US, or New Zealand dollar as their official currencies. Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Nauru, for example, all continue to use the US dollar to this day.

The Rhodesian Dollar

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States weren’t the only countries to use the “dollar” as a currency.

In Africa, the British colony of Rhodesia would eventually switch from the pound to the dollar. The Rhodesian dollar was introduced as a decimalized system in 1970, replacing the old shillings and pence system. That currency would only last until 1980, when Rhodesians voted to not only change the name of their currency, but also the name of their country: today, the former British colony of Rhodesia is known as Zimbabwe. As we learned above, the new Zimbabwean currency would not survive past 2009.

Where Does the Dollar Sign Come From?

There’s one more mystery we have yet to explain about the US dollar: where does its ubiquitous “$” sign come from?

We actually don’t know for sure where that sign originated, but there are a few different theories:

United States Abbreviation Theory: Some believe the dollar symbol arose out of a combination of the letters “U” and “S”. When you put the letter “U” overtop of the letter “S”, then drop the lower part of the “U”, you get the $ symbol with two strokes through it.

Peso Theory: The Spanish peso’s abbreviation was simply “P”, but the plural form of the Peso was a large “P” with a small “s” above it and to its right. That small “s” was sometimes superimposed over top of the P, which would lead to the modern US dollar symbol.

There are also several other theories about why the dollar is displayed with a “$” symbol, but those are the two leading theories. Other theories include the “Potosi Mint Mark Theory”, the “Shilling Abbreviation Theory”, and the “Portuguese Cifrao Theory”, all of which can be read about in this informative article here.

What Does the Future Hold for the US Dollar?

Ultimately, the United States dollar is the most widely-used currency in the world. This isn’t by accident: for decades, the US dollar has been viewed as one of the world’s most stable currencies.

Sites like Investopedia are also optimistic about the future of the US dollar:

“Barring some unforeseen catastrophe, the U.S. dollar will likely remain the global currency of choice until such a futuristic time when a global digital money system is invented and accepted.”

Asked by: Roxane Becker DDS

Score: 5/5

(56 votes)

The word dollar is the Anglicized version of the German word thaler (Czech tolar and Dutch word daalder or daler), a shortened version of the word Joachimthalers. The word thaler comes from the German root “thal” which means valley and “thaler” indicates a person or thing from the valley.

How did the dollar get its name?

History. The dollar is named after the thaler. The thaler was a large silver coin first made in the year 1518. The thaler named after the Joachimsthal (Joachim’s valley) mine in Bohemia (Thal means valley in German).

When was the term dollar first used?

The dollar was proposed as the monetary unit of the United States in the early 1780s, and adopted formally in 1792 (although they were not actually issued as currency until 1794). Since that time our language has taken on a remarkable number of synonyms for this word for “100 cents,” often found in the form of slang.

Is dollar a Spanish name?

The common ancestor is the taler (pronounced like “dollar”), also spelled thaler, a series of silver coins minted in Germany in the 1500s. … In the thirteen colonies, a Spanish coin called pieces of eight came to be called Spanish dollars because of their resemblance to talers.

Who came up with the dollar?

Origins: the Spanish dollar

The United States Mint commenced production of the United States dollar in 1792 as a local version of the popular Spanish dollar or piece of eight produced in Spanish America and widely circulated throughout the Americas from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

20 related questions found

Who invented money?

The first region of the world to use an industrial facility to manufacture coins that could be used as currency was in Europe, in the region called Lydia (modern-day Western Turkey), in approximately 600 B.C. The Chinese were the first to devise a system of paper money, in approximately 770 B.C.

Why is US money green?

The green ink on paper money protects against counterfeiting. … This special green ink is just one tool that the government uses to protect us from counterfeiters. Also, there was lots of green ink for the government to use when it started printing the money we have now.

What are Spanish cents?

One euro is divided into 100 cents, and you´ll find eight different types of coins for the Spanish currency: 1cts, 2cents, 5 cents, 10cents, 20 cents, 50 cents as well as 1euro and 2-euro coins. When talking about the Spanish bank notes, you can find 7 different kinds: 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 euros.

Why is a dollar like a Neanderthal?

By the 1860s the new man identified by the fossils was named Neanderthal. … (The German given name is from Old Testament Hebrew, but seems not to have been used by the English; it is, however, cognate with Spanish Joaquín.) The English spelling had been modified to dollar by 1600.

What was before the dollar?

Commodity money was used when cash (coins and paper money) were scarce. Commodities such as tobacco, beaver skins, and wampum, served as money at various times in many locations. Cash in the Colonies was denominated in pounds, shillings, and pence.

What is US dollar backed by?

In contrast to commodity-based money like gold coins or paper bills redeemable for precious metals, fiat money is backed entirely by the full faith and trust in the government that issued it. One reason this has merit is because governments demand that you pay taxes in the fiat money it issues.

What are the 4 types of money?

Economists identify four main types of money – commodity, fiat, fiduciary, and commercial. All are very different but have similar functions.

Why is a dollar a dollar?

Those coins, particularly the Spanish peso or dollar circulated widely in Britain’s North American colonies because of a shortage of official British coins. That is why, after the United States gained its independence the new nation chose «dollar» as the name of its currency instead of keeping the pound.

How many dollars is 100 cents?

For example, 100 cents equals 1 dollar.

What are Mexican slang words?

11 Mexican Slang Words Only the Locals Know

- Pendejo. One of the most used slang words in Mexico is calling someone a ‘pendejo’. …

- Güey. Güey, sometimes spelled in the way it is pronounced as ‘wey’, means “mate” and is used all the time in Mexican Spanish. …

- Chido & Padre. …

- Cabrón. …

- Buena Onda. …

- La Neta. …

- Pinche. …

- Crudo.

Which word is slang for money?

This also became dough, by derivation from the same root), «cabbage», «clam», «milk», «dosh», «dough», «shillings», «frogskins», «notes», «ducats», «loot», «bones», «bar», «coin», «folding stuff», «honk», «lolly», «lucre»/»filthy «Lucre», «moola/moolah», «mazuma», «paper», «scratch», «readies», «rhino» (Thieves’ cant), …

Does pasta mean money in Spanish?

Money, money, money. Or, pasta, pasta, pasta if you’re in Spain. That’s right – rather than a call out to the Italians across the sea, in Spain pasta means money. Whether in coins, notes, cards, pesetas or Euros, whether you have it or not, it’s all pasta to the Spanish.

What is the name of Spain money?

What is the official currency? The Euro (€). You can consult its official value on the European Central Bank website. One Euro is made up of 100 cents, and there are eight different coins (1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 cents, and 1 and 2 Euros), and seven notes (5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 Euros).

What country uses pesetas?

Peseta, former monetary unit of Spain. The peseta ceased to be legal tender in 2002, when the euro, the monetary unit of the European Union, was adopted as the country’s sole monetary unit.

What is the actual color of money?

Why money is green

When paper notes were introduced in 1929, the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing opted to use green ink because the color was relatively high in its resistance to chemical and physical changes.

Did the US ever have a 3 dollar bill?

Though a gold three-dollar coin was produced in the 1800s, no three-dollar bill has ever been produced. Various fake US$3 bills have also been released over time. … However, many businesses print million dollar bills for sale as novelties. Such bills do not assert that they are legal tender.

What is the color for money?

Gold: Gold is also the color of money and power.

Gold bars. Gold jewelry. All of these things represent money and wealth.