В Twitter-аккаунте малоизвестного американского рэпера Rick Smoove появилась запись фрагмента рэп-баттла, которая быстро разлетелась по западному сегменту сети. Дело в том, что на ней запечатлено, как белый баттл-рэпер локального масштаба, выступающий под псевдонимом William Wolf, получает от оппонента по лицу всего за одно произнесённое слово.

Наверняка вы уже догадались, какое слово, произнесённое на американском рэп-баттле в адрес чернокожего оппонента, могло стать причиной удара. Тот самый фрагмент смотрите в твите, прикреплённом ниже:

Примечательно, что порой даже российские баттл-рэперы больше задумываются о целесообразности использования N-слова в своих текстах, чем их западные коллеги (для которых, как вы сами могли видеть, это куда более критично). Так, ещё год назад Oxxxymiron в четвёртом выпуске «СТОЛ: Fresh Blood» отдельно затронул тему использования спорного слова в баттлах.

По словам ментора команды «Злые голуби», на одном из ранних этапов сезона ему не понравилось, что член его команды LeTai злоупотреблял этим словом в своих раундах. Тогда он собрал «Злых голубей» и попытался объяснить им, почему так делать не стоит: хотя в России не было рабства чёрных, поэтому N-слово, употребляемое на местных баттлах, не носит сколь-либо оскорбительного характера, да и вообще Мирон против запрета отдельных слов, следует помнить, что мы не находимся в изоляции. Мирона читает определённое количество людей из баттл-культуры с Запада, и он не может взять и поделиться с ними хорошим фрагментом раунда того же LeTai, в котором тот кидается упомянутым словом «по десять раз в минуту», поскольку это будет выглядеть подло и низко. Послушать тот разговор вы можете в ролике ниже — смотрите с 11:50.

Post navigation

At one of his recent shows, the Pulitzer Prize winning rapper and emcee Kendrick Lamar asked a white fan to stop rapping the n-word.

The crowd in Gulf Shores, Ala., started booing as the fan used the racial slur. The rapper had invited the fan identified as “Delaney” on stage to sing “M.A.A.D. City” during his set.

But he stopped the music and told her, “You gotta bleep one single word.” Delaney appeared not to realize why Lamar had stopped her from singing. She asked: “Am I not cool enough for you, bro?”

She apologized, saying: “I’m so sorry …I’m used to singing it like you wrote it.”

A video recording of the incident in Alabama has reignited a controversy that gained wide attention last year.

Last fall social media erupted after a video of white sorority girls singing along to Kanye West’s mega hit Gold Digger went viral. The lyrics include the word n-gga. The students promptly apologized and were absolved of racism by their university and by commentators and journalists — most notably Piers Morgan.

Morgan, writing in the Daily Mail, insisted that white listeners of rap music cannot be reproached for using the n-word. Rather, he said, they are targeted and exploited by Kanye and other Black celebrities, who send mixed messages about whether the n-word is offensive. Morgan wrote: “The only way to stop its use is for everyone to stop using it, including Black people.”

Though Morgan’s take on the n-word was widely derided, it went viral, and a few commentators endorsed it in whole or in part. As a white fan of rap music and as a linguist who writes and teaches about hip-hop language, I feel compelled to add my voice to others who have countered his poorly informed arguments.

Hip-hop as counterculture

Though hip-hop is now consumed by mainstream pop audiences, it is traditionally made for, and by, working-class Black youth whose “in-group” acceptance depends in large part on their fluent use of Black vernacular English. “There is no question that Black talk provides hip-hop’s linguistic underpinnings,” write linguist John Rickford and his son, journalist Russell Rickford, in Spoken Soul: The Story of Black English. They go on to explain:

Nothing thumbs its nose at conformity like the unrestrained African American vernacular. Although white suburban youngsters eat up hip-hop’s edgy tales of money, sexual adventure, ghetto life, and racial injustice (and keep ghetto rhymes atop the pop charts), Black urban youngsters are the genre’s target audience.

Now the n-word looms large in the vernacular of many Black youth. In a new linguistic study of “Black Twitter,” the n-word stands out as the most frequent distinctively Black form, being used 6.6 million times by Black American Twitter users in a single month. The study notes that the n-word has various uses but defines it simply as “guy.”

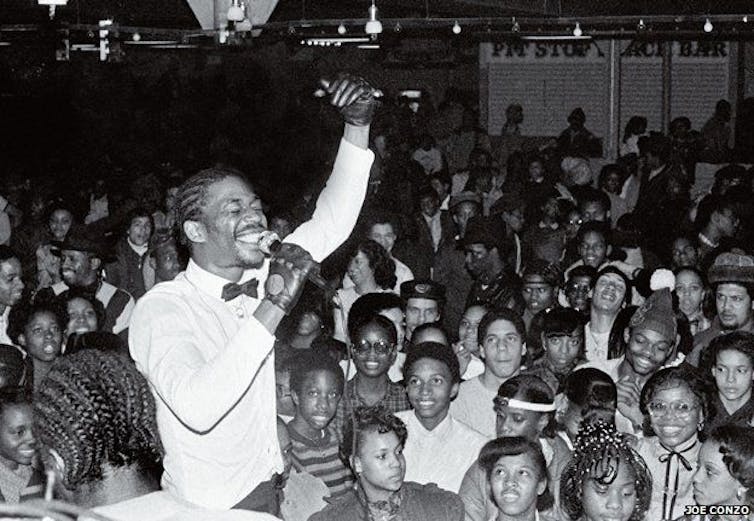

Black emcees, too, generally use the n-word as “guy,” with diverse connotations, none of them truly offensive. In Something From Nothing: The Art of Rap, Grandmaster Caz, a hip-hop elder, explores the word in a 300-word freestyle that includes 46 instances of the term. Caz shows that it has dozens of meanings, ranging from peaceful to aggressive, from camaraderie to competition, and from boasting to “dissing.”

I’m that top n-gga, … I won’t stop, n-gga … I’m that sweet n-gga, that never off-beat n-gga … I’m that cool n-gga, ran my whole high school n-gga … I’m that proud n-gga, that stand out in the crowd n-gga … I’m that smart n-gga, always first to start n-gga. I think with my head, but I feel with my heart, n-gga!

(©Joe Conzo and Cornell University Library)

A Black man from the Bronx, Caz’s use of the n-word in these lines is in direct opposition to “out-group” racist uses of the term. According to a philosopher of language, Adam Croom, the racial slur describes “a constellation of prototypical attributes,” the most derogatory being “subservient,” “prone to laziness,” “prone to violence,” “simple-minded,” and “emotionally shallow.” Croom explains that slurs are used in non-derogatory ways within countercultures such as hip-hop, to oppose and to subvert entrenched sociocultural norms.

Surviving racism and the evolution of language

Black youth appear to strengthen their solidarity and identity by using the n-word as an in-group term. Linguist Jacquelyn Rahman argues the term may help Black males identify as “resourceful, pragmatic survivors” of racial injustice. “During the period of slavery, n-gga became a term that Africans used to refer to themselves and companions in the struggle to survive,” explains Rahman. “Using the term highlighted the identity of a speaker as participating in the culture of survival.” This is apparent when Jay-Z tells himself in Holy Grail, “you still alive, still that n-gga. N-gga, you survived, you still gettin’ bigger.”

(AP Photo/Brian Kersey)

The survivor meaning of the n-word has a long history. But African Americans have also developed new meanings and uses of the word in the last few decades. For instance, its use has expanded from noun to noun modifier. An iconic example is New Orleans’s MC T. Tucker who described himself as “the n-gga, the n-gga n-gga, … the n-gga n-gga n-gga you love to hate.” The n-word has also grown from an expression of solidarity among survivors to a term of endearment (as in, “that’s my n-gga”).

The n-word has even evolved into a meaning-neutral pronoun in the first or third person, similar to “I/me,” “we/us,” “he/him,” and “they/them.” So for instance, KAAN simply refers to himself when he raps, “I’m still rolling by myself, a n-gga [I] never had a crew … you lookin for a n-gga [me], you know where to find me … Lawd knows that a n-gga [I’m] feelin hopeless.”

Altogether, then, the use of the n-word in hip-hop is about identity and survival. When a Black emcee says the n-word, it is intended without derogation. So can white hip-hop heads — like me — and other non-Black people rap along without being offensive?

It is never OK: Eminem

In my rap linguistics course a few years ago, a student of South Asian heritage made a memorable class presentation titled, “The meaning of n-gga.” He’d asked a Black childhood friend to join him in class that day, to stand beside him, and to say each instance of the n-word in his stead. My student said that though he is a person of colour and an emcee immersed in hip-hop culture, from a “hood area” in Northeast Calgary, he makes a point of never saying this word, even with Black friends who encourage him to use it. One of his idols, white rapper Eminem, never does either.

(AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

Indeed, Eminem and the Black culture of hip-hop famously adopted each other. Much of Eminem’s accent, grammar and vocabulary are drawn from Black vernacular English, but he avoids saying the n-word. (He admitted he said it on occasion in his teens but he has been mostly excused for this — as Nas wrote, he’s “not mad ’cause Eminem said n-gga, ’cause he my n-gga.”) In ’Till I Collapse, Eminem even avoids a euphemism for the n-word — by substituting “wizzle” for “nizzle” in Snoop Dogg’s well-known expression “fo’ shizzle, my nizzle.”

This song (like many others by Eminem, such as Not Afraid and Survival) is about being a “survivor.” Because the n-word is deeply rooted in African-American history, Eminem cannot use it to mean “survivor,” no matter how integrated he is in the Black culture that is hip-hop. More generally, because Eminem is white, he cannot subvert the n-word as non-derogatory, as Black hip-hoppers can with each other. Only the in-group members that the slur was originally intended to target can perform this “normative reversal.”

So for Eminem, the n-word must remain the racist slur that white America has always used and sadly, some continue to use.

The bottom line is this: if a renegade rap god, who is one of the most unrestrained artists in hip-hop, won’t rap the n-word, then what might possess mere white listeners of rap music to do so?

In all the years I’ve been debating race and racism with white people, the most common response some have offered in their own defense hinges on black people’s use of the N-word.

“If they can say it, why can’t we?”

It’s a question Kendrick Lamar might be hearing a lot following an incident onstage May 20 at the Hangout Music Festival in Gulf Shores, Alabama. The Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper, who headlined the three-day fest along with The Chainsmokers and The Killers, invited a group of people from the crowd for a rap-along to his 2012 single “m.A.A.d. city.” Things were going great until one young fan, a white female who introduced herself as Delaney, got the lyrics a bit too right.

After she delivered the lines in which the N-word is repeated several times, Lamar became visibly angry, told the fan that a “bleep” was in order (suggesting that, really, she should have known better) and ultimately booted her from the stage.

“It’s over,” he said, ending her less than 15 minutes of fame. (Watch video captured from the audience below.)

rip delaney @kendricklamar pic.twitter.com/GATaVPli5F

— taylor (@taylormprince11) May 21, 2018

Response has been mixed. Some have accused the young girl of being insensitive and foolishly failing to understand the potential ramifications of a white person using the N-word. Meanwhile, others have wondered why Lamar didn’t use a more lyrically neutral song for the rap-along while branding him a hypocrite for practicing what he preaches against.

I believe both sides have valid points. As I try to explain whenever white people challenge me on black use of the N-word, particularly in the rap and hip hop community, it’s all about context. It’s like the difference between a man using the B-word against a woman and another woman doing the same.

The legacy of racism in the United States revolves around the N-word and how many in the white community have historically used it as a verbal weapon against black Americans. It’s as bracing a reminder as cotton, chains and Confederacy memorabilia of what our ancestors endured for centuries.

Even today, for many of us, when a white person utters the N-word, it’s like the sound of a whip slapping the back of a slave. Because of its loaded history, it will never be OK for white people to use the N-word (not even if it’s Eminem, though he inexplicably seems to get a pass from the hip hop community), no matter what the circumstance.

In recent decades, some blacks have co-opted the word that some whites still use against them as an almost term of endearment for their fellow African-Americans, often modifying it to “nigga,” presumably to dilute it defeating effect. It’s a way of taking a weapon that kept African-Americans beaten down mentally for generations and embracing it, thus robbing it of its destructive power.

While I understand the psychology behind this, clearly it hasn’t worked. There’s no getting past the destructive power of the N-word, and Lamar’s reaction to Delaney and the round of boos she received underscore just how hurtful it remains today. But are blacks partly to blame for its continued dominance in the American vernacular?

The current widespread success of rappers like Lamar and J Cole, whose latest album KOD is peppered with the N-word, wouldn’t be possible without the support of white fans. And as any chart-watcher knows, the commercial viability of music depends on the ability of listeners to recreate the melody and mimic the lyrics.

If you are going to accept royalties from album sales and concert revenue from both black and white fans, you can’t legitimately expect them to consume your music differently. Would Lamar have reacted the same way to a black fan? Did he really think a starstruck teenage girl who probably has never been in front of such a massive crowd would instinctively know that she was supposed to censor herself when he doesn’t? Is it really fair to have one set of rules for black fans and another for white fans?

Teens are impressionable, whether they’re white or black. As rap and hip hop continue to gain in popularity, white kids have increasingly co-opted the style and mannerisms as well as the syntax and speech patterns of its stars, in a sort of mass cultural appropriation. Delaney even referred to Lamar onstage as “bro,” which I personally find just as cringe-worthy as her nailing his lyrics.

It’s time for rappers to rethink how they deliver their message. It wouldn’t lose any of its lyrical might if they dropped the N-word altogether. Lamar’s “HUMBLE.” would be just as potent with all of the N-words removed. What do they add to the song’s message anyway?

If anything, they detract from it. Whites who don’t necessarily relate to the messages that socially conscious rap delivers may get the impression that if Lamar is OK with spreading the N-word, if Cole is cool with it, then maybe racism isn’t as much of an issue as blacks say it is. Maybe the N-word is OK for everyone to use, after all.

As Delaney found out the humiliating way at Hangout, nothing could be further from the truth. The N-word is as harmful and hurtful as ever, and it won’t be going away anytime soon.

For that, the kings and queens of rap and hip hop must accept some of the blame. It’s not too late to turn things around, but if a change is gonna come, it might have to start with them.

The n-word is probably the most emotionally and historically charged word there is in English, at least in the United States. The rules of its use are clear: black people can use it, having reclaimed it and given it new meaning. White people cannot. It’s simply impossible to separate from its history as a disgusting racial slur and a vestige of centuries of enslavement and mistreatment.

But for white hip-hop fans—and they are plentiful, hip-hop now being bigger than rock music—the situation doesn’t always seem so straightforward. A lot of white kids have grown up listening to hip-hop. It’s part of their culture. Hip-hop artists tend to use the n-word liberally in their songs. White kids often want to sing along, and may feel entitled to when they believe could never harbor the same repugnant views as the bigots who made the word a weapon. So can they?

No, they can’t.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, the acclaimed author and writer for The Atlantic, offered a clear explanation why during a tour stop at an Illinois high school for his latest book, We Were Eight Years in Power. A student asked him the question outright, saying that her friends constantly use the word when singing along.

“Words don’t have meaning without context, OK?” Coates, who has defended the use of the n-word by black Americans, began in response. He offered different examples of how this dynamic plays out. His wife, for instance, refers to him as “honey” because that’s an accepted term between them, but if a stranger did, that wouldn’t be acceptable.

It’s a normal and widespread behavior. Similarly, different groups, such as the LGBT community, have their own ways of referring to each other that are off limits to those outside the group, such as derogatory words used ironically. People generally understand this, Coates noted. So why, he asked, do white people still get hung up on not being allowed to use the n-word?

“When you’re white in this country, you’re taught that everything belongs to you,” he said. “You’re conditioned this way. It’s not because your hair is a texture or your skin is light. It’s the fact that the laws and the culture tell you this.”

Because of this culture, white Americans often feel they have a right to use the n-word when they hear black Americans using it. ”I have to inconvenience myself and hear this song, and I can’t sing along?” Coates mock-asked. “How come I can’t sing along?” That’s where the lesson lies. He explained:

For white people, I think the experience of being a hip-hop fan and not being able to use the word “nigger” is actually very, very insightful. It will give you just a little peek into the world of what it means to be black. Because to be black is to walk through the world, and watch people doing things that you cannot do, that you can’t join in and do. So, I think there’s actually a lot to be learned from refraining.

Coates’s explanation, beyond making a good point, was also funny. The video, posted to YouTube by his book’s publisher, Random House, is worth watching in full.

Quartz is owned by Atlantic Media, which also owns The Atlantic magazine.

by Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

Note: I will use the term n-words, when referring to “nigga” and “nigger” collectively.

Since the moment Jay-Z launched the music-streaming service Tidal at the end of March, the rapper-turned-mogul has been on the defensive. I will not rehash all of the criticisms being leveled at Tidal, as they are well articulated here and here for starters; suffice it to say that if the company survives, Jay-Z will likely be doing damage control for a long time. I, on the other hand, am pretty excited about Tidal. While I haven’t actually purchased the app, the reception of its launch has provided me with plenty of food for thought as it relates to the business of music, the diminishing power of celebrities in society, and the politics of being black in corporate America. Tidal’s launch has even indirectly provided me with the angle I needed in order to finally finish this think-piece about rap and the n-words I have been struggling to write since last summer. Let me explain.

It all started on the evening of Saturday May, 16th. After responding to naysayers through a series of tweets in April, Jay-Z moved to more familiar terrain that night, lambasting his critics via a freestyle he delivered during a private concert for Tidal subscribers. As I perused the annotated verse on Rap Genius the next day, my eyes latched onto one line in particular:

I feel like YouTube is the biggest culprit

Them niggas pay you a tenth of what you supposed to get.

I paused, scratched my head, and looked over more bars.

Let them continue choking niggas

We gonna turn style, I ain’t your token nigga

I compared the first set of bars to the second set a few times and began thinking aloud: Have rappers always used the word “nigga” as a stand-in for every kind of person (or in this case LLC) under the sun, or am I just more sensitive to it?

I have certainly been a part of conversations with friends wherein the term “nigga” is used to refer to anybody, including, to my amusement, the most lily-white professors at my alma mater. Despite the fact that I am a rapper, I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t have a good enough knowledge of the genre’s history to justify my initial question. At the same time, because I am a rapper, and one who has used the term “nigga” in her music, I felt it important not to simply gloss over my reaction to Jigga’s latest verse, even if it may only have been the result of my growing sensitivity towards the word.

Recently, I have become quite obsessive as it relates to checking the meaning of my words – a somewhat paranoid response to the growing social media presence around my music career. While I am overjoyed about expanding my network of supporters, every new Facebook like, Twitter follower, and Bandcamp purchase also serves as a reminder that I have less agency over the interpretation and use of the words I have written and recorded.

In turn, this realization has forced me to think more deeply about what it is I’ve actually been saying, particularly in the context of nerdcore rap music – a hip hop subgenre to which my work has been closely tied and one in which the majority of both its fans and most of its well-known MCs are white men. Although there are some notable exceptions, it’s safe to say that any explicit dealings with race around topics as charged as the politics of the n-words have never really been addressed. I often wonder how my words are understood in this scene as they are so intimately connected to my blackness.

I’ve also begun thinking about the frequency with which I’ve seen audience members mouthing my words during performances. The first time I witnessed this phenomenon, I was caught so wholly off guard that I temporarily forgot my words. These days, however, my excitement is usually tempered by my recollection of a video clip I’d seen circulating this past April in which a Coachella concert camera flashes to a white audience member while he emphatically sings “nigga” along with The Weeknd (and presumably most of the audience) during Drake’s set. I now wonder whether that’s happened at any of my shows.

To be clear, I have no judgments about black rappers who use the word in their music nor do I feel a way about those who intentionally do not. Additionally, my growing ambivalence around using “nigga” is in no way connected to the comfort of nerdcore’s primary fanbase. Making my music palatable and “safe” for non-black people has never been my intent. If anything, my driving force has often been a desire to engender difficult conversations between people who have never thought about blackness in the context of their favorite fandoms. On my latest project – a concept EP devoted to the classic video game Metroid – I use the word “nigga” as a way of establishing voice, a reminder that my experience of the game, even in my role as a raconteur, has always been mediated through the eyes of a self-aware black person in a space not designed for her. Yet, as stories about state-sanctioned violence against black people have become a regular part of my media diet, I am increasingly wondering whether my desire to create dialogue comes at the expense of creating a safe space for the very people I am trying to prioritize.

Rap’s Embrace of “Nigga”

A quick read-through of the 1993 New York Times article entitled “Rap’s Embrace of ‘Nigger’ Fires Bitter Debate” reveals that much of the popular discussion about rap and the n-words has remained the same over the past 20 years. Although the author overlooks important nuances related to the spelling of “nigga” and “nigger” the points of contention are the same: some maintain that the n-words can never be separated from their violent history, while others believe that reappropriation of the word “nigger” by black people divorces the word from its white supremacist roots. Popular rappers like YC the Cynic and Kendrick Lamar have taken things even further by cleverly exchanging the word “niggas” with the homophone “negus,” a term that refers to royalty in Ethiopian Semitic languages. And while more seasoned popular rappers have not quite taken that leap, most, if not all remain unapologetic in their usage of it. As Common has noted, “[I]f I talk over those people’s head or I don’t use language that I would naturally speak in raps, they may not get the message.” To him, the meaning of the word can be found in the colloquial context in which it is expressed.

As it relates to hip hop, I had unquestioningly taken a big part of this context to mean the race of the person rapping. Black rappers could say “nigga” whereas nobody else could do so unproblematically. If it were deployed by white rappers in a verse, as in the case of one of Eminem’s earlier works, it was necessarily interpreted as an act of violence and racism. And yes, though Bay Area rapper and “white girl mob” member V-Nasty received support from a few black rappers in defense of her right to use “nigga” in 2011, it is safe to say that no white rapper with a long-lasting national career has ever maintained the use of the n-words as a part of their rap lexicon.

Even so, I can’t shake the feeling that we are only a few years, if not months, away from such a rapper successfully emerging on the national stage. KRS-One may not have been far off in 1993 when he predicted, “In another 5 to 10 years, you’re going to see youth in elementary school spelling it out in their vocabulary tests…It’s going to be that accepted by the society.” Recently Chet Hanks, the son of Tom Hanks, attempted to argue much the same thing via Instagram, adamantly defending his right to say “nigga.” And although “Chet Haze” (Hanks’ rap persona), is nowhere near being nationally successful, his arguments in defense of the n-word’s broad appeal have certainly been echoed by more well-known non-black artists. This past March Cambodian-Canadian rapper Honey Cocaine defended her right to use “nigga” to Vice, arguing, “Like, where I grew up, everyone I know, black, Asian, whatever, says nigga. I know it’s controversial, but this is the world I grew up in.” Honey Cocaine’s use of the word as an Asian rapper is undoubtedly understood differently than it is with Chet Haze or V-Nasty, despite similarities in the rhetoric of their defense; still, at a moment when black and Asian activists are beginning to call out anti-blackness in Asian communities, it’s interesting to note how little has been said in this regard.

| Photo: Builder Levy |

Additionally over the past twelve months black rappers have made some alarming concessions as it relates to use of the n-words by their white “friends.” When video footage emerged in June 2014 of a much younger Justin Bieber singing “one less lonely nigger,” rappers like Young Money president Mack Maine and Common leapt to his defense, reasoning that he simply could not be a racist because he now “surrounds himself with black people.” In January of 2015, Jean Touitou, the founder of the menswear brand A.P.C. and close friend of Kanye West brandished the term “nigga” several times during a presentation of the company’s Fall collection, “Last Nigg@$ IN PARIS.” Touitou later “clarified” that he had received Kanye’s blessing although he eventually issued an apology only after jeopardizing A.P.C.’s relationship with their collaborator, Timberland. ‘Ye’s uncharacteristic silence throughout the ordeal spoke volumes.

A number of new school rappers seem to have an even less proprietary sense of the word. Schoolboy Q has encouraged white audience members to say “nigga” at his shows as a way of breaking bread. In an interview with Fader he clarified: “We’re not black, we’re not white, we’re not Asian. We’re just people here listening to music. You can say nigga in front of me, I don’t care.” Interestingly he added that white fans shouldn’t use the word outside of that context. Tyler the Creator contends that the word no longer has any meaning, a point perhaps best articulated through his portrayal of the rapper “Young Nigga” in his Adult Swim sketch comedy show Loiter Squad. In one scene, “Young Nigga” holds a press conference to relay the news that he will be removing the “offensive” part of his moniker after meeting with a young fan. He then of course proceeds to remove the “Young” part of his rap name and states that he will henceforth be going solely by “Nigga” – an announcement that is met with applause and excitement from the press.

To be fair, certain black entertainers have recently spoken up from the other side of the aisle, although much of their rhetoric is steeped in the problematic language of respectability. Media personality Charlamagne tha God, who once famously gave Justin Bieber an n-word “pass,” backtracked from his position shortly after Bieber-gate. In an interview with Vibe, Charlamagne stated, “I don’t care if it’s –er or –ga at the end—it’s a word with too much blood attached to it to ever be positive.”

Not long after that, hip hop pioneer Chuck D publicly blasted Hot 97’s Summer Jam music festival, citing the careless use of “nigga” as one of his major grievances: “If there was a festival and it was filled with anti-Semitic slurs… or racial slurs at anyone but black people, what do you think would happen?…Why does there have to be such a double standard?

Still, within the commercial rap world it would appear that these perspectives have largely been obscured by nihilist viewpoints like Tyler the Creator’s or the emergence of a certain kind of black respectability that has been branded the “new black” mentality. Although the mentality is actually quite old, this framing is based on a recent Pharrell interview with Oprah, in which he said, “The New Black dreams and realizes that it’s not pigmentation: it’s a mentality and it’s either going to work for you or it’s going to work against you. And you’ve got to pick the side you’re going to be on.” In response to Pharrell, among others espousing the “new black” mentality, Stereo Williams of the Daily Beast writes, “The idea that black people’s reaction to racism—and not the racism itself—is what must be addressed is an effective distraction that de-centers the struggle of black people. It centers the comfort of white people, absolving white supremacy and indicting black rage as ‘the problem.’”

As it relates to the n-words, part of what makes the new black respectability so insidious is that it legitimizes the non-black use of both “nigger” and “nigga” by making black people’s complex relationship with these words the problem. It is certainly true that the issues with Justin Bieber and those with V-Nasty represent two different sets of concerns; while the former deals with the use of racially-charged language as a way of othering, the latter deals with the desire to strip language of its racial significance in order to destroy the notion that there even is an Other. However “new black” rappers utilize the same flawed logic to defend both instances, the argument being that if we blacks can say a word, we can’t then be mad when they do it too. And furthermore it doesn’t matter who you are and what you say, it’s who you take with you to the club currently that matters. This line of reasoning creates the dangerous space in which assumptions about intent, rather than historical or cultural context, are the only basis for interpreting the use of highly charged language.

«Mr. Nigga» and «New Slaves»

All of this comes at an interesting moment for the world of mainstream rap music. While the industry has virtually imploded, many black rappers are experiencing unprecedented levels of fame and entry into spaces never before afforded to them. Sixteen years after the release of Black on Both Sides, the brilliant debut album from Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def), I am only now fully appreciating the importance of «Mr. Nigga,» which deals precisely with this topic. On the track, he chronicles a series of racist micro and macro-aggressions faced by black artists, athletes, and businessmen as they attempt to move up in the world metaphorically as well as via elevators and airplanes. It is the track’s title, recited throughout the song by Yasiin Bey and collaborator Q-Tip, that most poignantly encapsulates white America’s schizophrenic relationship with the upwardly mobile black man – extending him the courtesy of a formal title like “Mr.” rather than “boy” – while calling attention to his status as an Other through the use of “nigga.”

Yet despite resonances of the song’s message in more contemporary rap songs, I see a distinct difference between the way that Yasiin Bey waxed philosophical about white responses to black affluence in ‘99, and the way that successful black rappers of today do so. Jay-Z’s Tidal freestyle offers one great example, but more widely known cases can be found by looking at the catalog of his creative foil, Kanye West. When Yasiin Bey adopts the second-person perspective in “Mr. Nigga,” his “you” is the up-and-coming black man in question. “Say they want you successful, but that ain’t the case / You living large, your skin is dark, they flash a light in your face.” In stark contrast, the object of Kanye’s ire in songs like “New Slaves” are the affluent, presumably white individuals sometimes invoked by Yasiin Bey when he speaks of an abstract “they.” West does not speak in abstractions when he spits: “Fuck you and your Hampton house / I’ll fuck your Hampton spouse / Came on her Hampton blouse / And in her Hampton mouth.”

Similar to the prominence of white bodies in new rap contexts (to say nothing of white consumption of rap music), this kind of lyrical engagement with white audiences is both reflective and constitutive of what I suspect may be a sea-change of sorts around what is understood to be a nigga these days. In the same verse that Kanye sardonically calls himself nigga (“Y’all throwin’ contracts at me / You know that niggas can’t read”) and later refers to the mostly brown bodies trapped in the prison industrial complex as such (“They tryna lock niggas up / They tryna make new slaves”), he also refers to the Hamptons property-owning CEOs as niggas (“Fuck you and your corporation / Y’all niggas can’t control me”). According to Kanye, everybody is a nigga. I understand his point, but for me, the stakes are too high to be so indiscriminate when discrimination against black people is costing them their lives.

* * *

Rap music will continue to evolve and as it does, its purveyors must recognize that they are uniquely equipped to start critical discussions around race. Last year NYC rapper Homeboy Sandman broke the Internet after writing a Gawker article entitled, “Black People are Cowards.” In it he accused the LA Clippers (among others) of cowardice for their silence in regards to the racist remarks of former team owner Donald Sterling. While the title served its purpose as obvious click-bait, the piece sparked an important discussion about civil disobedience and the burden carried by those with the most to lose for fighting a problem they didn’t create. If the tastemakers don’t create spaces for these conversations, who will?

As an MC, a PhD student, and the daughter of two Afrocentric academics I sense that I will never be able to reconcile my stance on the word “nigga.” One of my earliest memories remains being called a “stupid nigger” by a group of high school students on their way home from school as I sat on a nearby park bench. In contrast, “nigga” wasn’t a word I ever really heard while growing up (outside of hip hop music), but once I entered college I was surrounded by black people who often used the word casually. By my senior year, it had entered my lexicon quite organically.

Even so, when I first began rapping in 2009 I couldn’t bring myself to put “nigga” in my rhymes. As I began freestyling and working with more seasoned rappers, I began unconsciously peppering my verses with the word. Over time it became a way for me to insert my raw blackness into a scene where race is rarely discussed. I was even warned by some peers in the nerdcore community that my language was going to hinder me from getting important gigs. Given that several notable nerdcore artists deploy a litany of expletives while on stage, I suspected that “language” was a euphemism for “nigga” (which is even more infuriating because I have since learned about white artists in the nerd/geek music scene who casually use the n-words in conversation). I made a vow that I would never tone it down and I have since performed at some of nerdcore’s biggest venues – MAGFest, PAX East, and the official nerdcore stage at SXSW, among others.

While I am proud of myself for maintaining my artistic integrity, I now want to try prioritizing black voices in a different way with my next project. Maybe it will work, maybe it won’t, but for now I cannot justify employing a word that has the potential to only harm black people despite more people claiming it as their own to use. Instead I will focus on creating an earnest and open space for my most marginalized listeners, whether they’re standing in the audience at a show or maybe one day checking me out on Tidal.

Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo is a PhD candidate in Science & Technology Studies at Cornell University. Articles she has written on hip hop have appeared in such notable online publications as For Harriet and Bitch. In addition to her research and teaching obligations, she has also been rapping and producing under the stage name Sammus since 2009. Follow her on Twitter @SammusMusic.