Hallo, Deutschlerner. Today I am going to show you how to form your own questions in German, so you can really open up the versatility of your German skills. You will learn the word order rules for questions in German. Then I will teach you some basic German question words. Stick around for the end of the video and I’ll explain to you why I think the subject and verb are in a romantic relationship with each other.

This lesson is a part of Herr Antrim’s new e-book “Beginner German with Herr Antrim“. Within the e-book, this lesson includes a worksheet and answer key to practice the skills you are about to learn. You will also get access to online flashcards and a whole lot more. Find out more about the e-book here.

Statement Word Order in German

Before we get into formation of questions, we need to first take a step back and look at the formation of statements, so you understand what is going on when we switch to a question. Statements generally start with the subject of the sentence, the person or thing doing something in the sentence. The next thing in the sentence is the verb, which is changed to match the correct form for the subject. After that we have a variety of other things, but to keep things simple for today’s lesson, we are going to refer to these things as “other stuff”. So the general word order for a statement in German is: subject, verb, other stuff. For example:

Ich bin Levi.

I am Levi.

Der Mann geht nach Hause.

The man is going home.

Wir kaufen die Bahnkarten.

We are buying the train tickets.

In order to make a simple question out of a statement, we simply move the verb to the other side of the subject. In other words: verb first, then subject, and the other stuff is still at the end. Let’s go back to the example “Der Mann geht nach Hause.” To make a question out of this we move the verb, “geht”, to the first position. Now our sentence is:

Geht der Mann nach Hause?

Is the man going home?

Let’s try that again.

Die Kinder spielen Fußball.

The children are playing soccer.

Spielen die Kinder Fußball?

Are the children playing soccer?

Using Statement Word Order with German Questions

Notice in the video that just like in English my voice changes a bit at the end of the last word to indicate that this is a question. If you do the same thing with your voice when reading the statement, you can sort of ask the question, but the connotation changes.

Notice the difference between “Die Kinder spielen Fußball?” (The children are playing soccer?) and “Spielen die Kinder Fußball?” (Are the children playing soccer?) The first one indicates a disbelief. The children usually play basketball, but now they are playing soccer? That is weird. “Die Kinder spielen Fußball?” But if you are just asking whether or not the children are playing soccer, you would need the normal question word order of “Spielen die Kinder Fußball?”

Changing the Subject Between Question and Answer

Sometimes your subject should not be the same in your question as it is in your answer. For example, if I am the one responding in the answer to the question, the question probably used the pronoun “you”. For example:

Wohnst du hier?

Do you live here?

Ja, ich wohne hier.

Yes, I live here.

Bleiben Sie lange?

Are you staying long?

Nein, ich bleibe nur zwei Tage.

No, I am only staying two days.

I only bring this up, because it isn’t always obvious that this needs to change when you are first learning German. It feels obvious once you learn it, but before that it seems confusing. It is a good reminder that the subject and the verb must always agree, which is why your verb changes between the question and the response.

German Question Words

The questions I have shown you so far are a bit boring, however, as we don’t yet have question words. Question words are technically interrogative pronouns. The reason I mention this is because pronouns replace things in the sentence. The subject pronouns that I talked about in lesson #8, for example, replace nouns that are the subject of the sentence.

When you use a question word in a question, you are indicating that there is a lack of knowledge about a part of the sentence. The answer to the question no longer has the question word in it, as the question word has been replaced with the formerly missing information. Think of the question words as placeholders for more substantive information.

Was – What

The first question word you should learn is “was”. This means “what” and is mostly used like it is in English. For example:

Was kaufst du?

What are you buying?

Ich kaufen ein Sofa.

I am buying a sofa.

Was ist das?

What is that?

Das ist ein Döner.

That is a döner kebab.

Was denkst du darüber?

What do you think about that?

“Was” can either be the subject of the sentence, as it was in the question “Was ist das?” or it can be an object like it was in the question “Was kaufst du?” “Du” is the one buying something in that question. The something being bought is the object “was”. I mention this, because if the question word “was” is the subject of the sentence, the conjugation of the verb is usually the third person singular (er, sie, es) form of the verb. For instance:

Was steht in der Ecke?

What is standing in the corner?

The conjugation of the verb can be the third person plural (sie) form, if you know that “was” refers to more than one thing. For example:

Was sind diese Dinge?

What are these things?

*It is important to note that technically “Dinge” are the subject of this sentence along with “was” due to the special nature of the verb “sein”.

Wo – Where

Next up we have the question word “wo”. This means “where” in English. It is great for asking where things are, which is pretty important if you are visiting Germany. Keep in mind that in contrast to “was”, the German question word “wo” can never be the subject of the sentence (except with ‘sein’), which means you are not restricted to the third person singular (er, sie, es) or plural (sie) forms of verbs. Here are a few examples of how you can use this question word.

Wo finde ich die Toilette?

Where do I find the toilet?

Wo lebst du jetzt?

Where do you live now?

Wo beginnt das Rennen?

Where does the race start?

Wo ist deine Mutter?

Where is your mother?

Wo warten wir auf den Bus?

Where are we waiting on the bus?

Wo lernt ihr Deutsch?

Where are you learning German?

Wo gehören diese Bücher?

Where do these books belong?

Wer – Who

The next question word you should know is “wer”, which means “who” in English. The official rules for “wer” and “who” are supposed to be the same, but English speakers don’t really seem to care anymore what the difference between “who” and “whom” is, which leads to some problems when trying to ask questions in German.

Short version: “who” is the subject of the question, but “whom” is not. That’s all that matters for right now. “Wer” is always the subject of the sentence. We use it to ask about the person who is doing the action of the sentence. It is also exclusively used to inquire about people or in rare cases personified animals.

Wer = Who, but Wo = Where?

“Wer” and “wo” are often difficult for English speakers to grasp, as “wo” looks a lot like “who”, but means “where” and “wer” looks a lot like “where” and means “who”. The way I remember it is that you can answer the question “wer” with “er”, which is simply the question word without the “W” at the beginning. This is also good for reminding you that the conjugation of the verb with this question word is often the same as the third person singular (er, sie, es) form.

Examples of “wer”

Here are a few examples of how you can use this question word. I also answered these questions, to show you that you can replace “wer” with “er” to answer the question.

Wer nennt eine Möhre eine Karotte?

Who calls a carrot a carrot?

In German there are multiple words for carrot.

Er nennt eine Möhre eine Karotte.

He calls a carrot a carrot.

Wer zeigt uns das WC?

Who is showing us the restroom?

Er zeigt uns das WC.

He is showing us the restroom.

Wer führt die Ponys auf dem Weg?

Who is leading the ponies on the path.

Er führt die Ponys auf dem Weg.

He is leading the ponies on the path.

Wer with Plural Answers

Again the conjugation of the verb is in the third person singular (er, sie, es) form when “wer” is the subject. This applies even if you know that the answer to the question is plural. For example:

Wer ist schon da?

Who is already there?

Sie sind schon da.

They are already there.

Wer wohnt in diesem Haus?

Who lives in this house?

Wir wohnen in diesem Haus.

We live in this house.

Wann – When

The next question word you should learn is “wann”, which means “when” in English. It is used to inquire about the time of some event or action. Again, since the question word is not the subject of the sentence (“when” can’t do something), the conjugation of the verb is not dependent upon this question word. The subject of the sentence will be directly after the verb and the conjugation of the verb will match that subject.

Wann bringst du das Buch zurück?

When are you bringing the book back?

Wann lernen wir über das Passiv?

When are we learning about the passive voice?

Wann braucht er eine Antwort?

When does he need an answer?

Wann beginnt der Film?

When does the film start?

Wann bekommen die Müllers ihr Auto zurück?

When are the Müllers getting their car back?

Wie – How

You have already seen our next question word in a few simple questions from the last video. “Wie” means “how”. This question word also is never the subject of the sentence. Here are some examples of how to use “wie”.

Wie heißen Sie?

How are you called?

Wie geht es Ihnen?

How are you?

Wie meinst du das?

How do you mean that?

Wie schläft dein Hund?

How does your dog sleep?

Wie erreichen wir unsere Ziele?

How do we reach our goals?

Wie + Adjectives

“Wie” is a much more versatile question word than the other ones we have seen so far, as we can add adjectives after it to inquire about the degree of something. You can do the same thing in English, which you will see in these examples.

Wie groß bist du?

How tall are you?

Wie alt bist du?

How old are you?

Wie sauer ist dieses Bonbon?

How sour is this candy?

Wie lange bleibst du in Deutschland?

How long are you staying in Germany?

Warum – Why

The last question word on my list for today is “warum”, which is German for “why”. This one isn’t different from the English either, so I’ll just jump into the examples for this one.

Warum fragt er das?

Why is he asking that?

Warum verstehst du mich nicht?

Why don’t you understand me?

Warum erzählen Kinder solche Geschichten?

Why do children tell stories like that?

Warum versuchen Sie das nicht morgen?

Why don’t you try that tomorrow?

German Subjects and Verbs are Romantically Involved

And now, as promised, I’ll explain why I think the subject and verb are in a romantic relationship with each other. They have to be dating. The subject is almost always next to the verb. It is definitely the dominant personality in the relationship, as it is usually first in a sentence. If the subject isn’t first, it is directly after the verb. This happens like we saw earlier in this video with questions. Either the verb is first on its own followed by the subject, the question word is first followed by the verb and then the subject or the question word is the subject, which puts it first in the sentence again.

You can separate the subject and verb in complicated situations. They are in a long distance relationship when this happens. At the beginner level, you don’t really need to worry about this, but suffice it to say you can separate this clingy couple in more complicated situations (sentences). Since my students don’t learn about this until their junior year, I usually tell them that you can’t separate the clingy couple until their junior year, which is when they usually break up anyway.

The subject and verb take their relationship to the creepy level of wearing matching clothes. The verb changes to match the subject, as the subject is the dominant personality in the relationship, so it gets to choose the outfits they wear. If the subject wears the “du” pronoun, for example, the verb wears its “ST” outfit.

Beginner German with Herr Antrim

Herr Antrim’s new e-book “Beginner German with Herr Antrim“ is your guide to having your first conversation in German. Within the e-book, each lesson includes a worksheet and answer key to practice the skills in that lesson. You will also get access to online flashcards and a whole lot more. Find out more about the e-book here.

Lessons within “Beginner German with Herr Antrim”

- Download the E-Book

- #1 – Pronunciation

- #2 – Greetings

- #3 – Farewells

- #4 – Du vs Ihr vs Sie

- #5 – How to Say You Don’t Speak German

- #6 – das Alphabet

- #7 – 24 Most Common Verbs with Example Sentences

- #8 – Subject Pronouns & Conjugation

- #9 – Basic Questions & Answers

- #10 – Formation of Questions

- #11 – Describe Yourself in German

- #12 – Present Tense of “sein”

- #13 – Present Tense of “haben”

- #14 – Family Vocabulary

- #15 – The Ultimate Guide to German Numbers

- #16 – Word Order with Time

- #17 – Read & Write Dates in German

- #18 – Word Order Basics

- #19 – Shopping

- #20 – A Beginner German Conversation

Как задать вопрос на немецком? Какие виды вопросов существуют? Каков порядок слов в немецком вопросительном предложении? Учимся спрашивать и отвечать по-немецки!

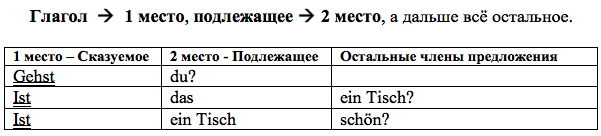

В первой части статьи мы разбирались с порядком слов в немецком повествовательном предложении. Что ж, идем дальше и посмотрим, какие отличия нас ждут при формировании вопросительного предложения.

В немецком языке вопросы можно задать четырьмя разными способами:

1. общим вопросом,

2. дополнительным вопросом,

3. альтернативным вопросом,

4. комбинации вопросов.

Разберем все четыре способа.

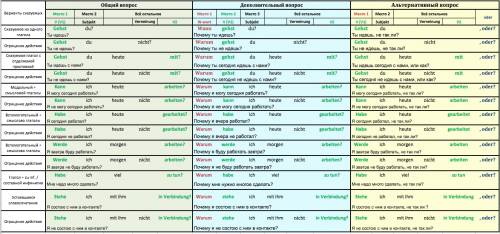

Общий вопрос в немецком языке

Общий вопрос — это, проще говоря, любой вопрос без вопросительного слова. Например, «Ты идешь?» – спрашивающего интересует только действие, а не куда, когда и зачем идет человек.

В качестве подсказки можно использовать то, что на такие вопросы возможен ответ «да» или «нет». Но, как правило, мы сами редко отвечаем коротко, а стараемся дать более полный ответ. В случае, если перед нами вопрос без вопросительного слова, порядок слов строится довольно просто:

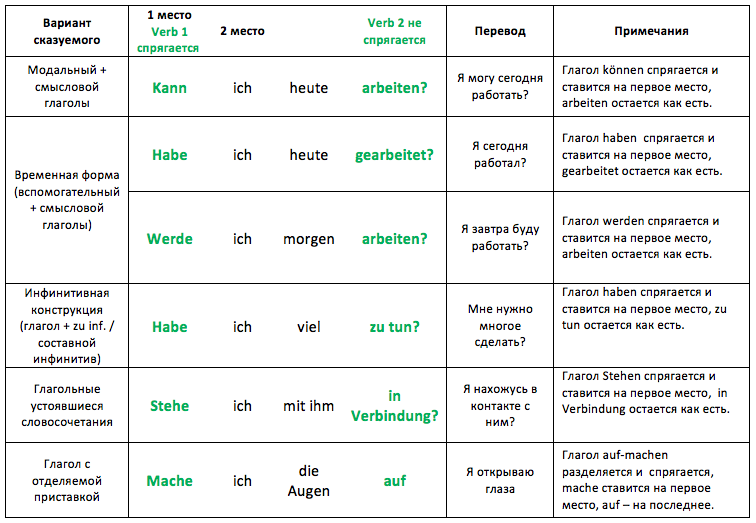

Если мы имеем дело с составным сказуемым (см. Порядок слов в предложении), то изменяемая часть V1 ставится на первое место, а неизменяемая V2 остается в конце предложения.

Хотите выучить немецкий, но все откладываете? Или пытаетесь учить самостоятельно, но топчитесь на месте? А может вам нужна помощь преподавателя? В Deutsch Online вы можете записаться на групповые курсы немецкого языка с сертифицированными преподавателями. Занятия проводятся на платформе в личном кабинете: уроки, весь материал для подготовки, тесты и задания в одном месте. Запишитесь прямо сейчас, количество мест ограничено!

Выбрать курс немецкого языка

Если в предложении есть отрицание действия (выраженное nicht), то nicht ставится:

- в конце (в случае с одним глаголом)

- перед V2 (в случае составного сказуемого).

Вывод — формирование вопроса никак не влияет на положение отрицания: Ich gehe nicht. — Gehst du nicht?

Дополнительный вопрос

Как следует из названия, этот вопрос заключает в себе дополнение, уточнение, более подробную информацию.

То есть «кто?», «что?», «зачем?», «куда?» и так далее. Это вопрос с вопросительным словом, и на него нельзя просто ответить «да» или «нет». Например, «Когда ты придешь?» или «Какой это стол?».

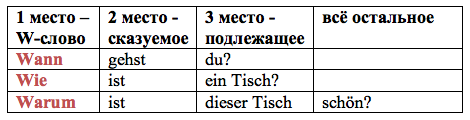

Вопросительные слова начинаются с буквы W и в немецком называются W-словами. Порядок слов в вопросе следующий: Вопросительное слово —> 1 место, глагол —> 2 место, подлежащее —> 3 место, а дальше всё остальное.

Если в предложении составное сказуемое, то вопросительное слово будет на первом месте, V1 – на втором, подлежащее — на третьем, а V2 – в конце предложения. Например: Wie kann ich heute arbeiten?

Альтернативный вопрос

Такими вопросами спрашивающий переспрашивает, например: «Ты идешь, не так ли?» или «Это ведь стол, да?», или «Я пойду гулять или нет?».

Выражаются эти вопросы через союз «или» – ODER. ODER можно использовать как в середине предложения для соединения вопросов, например: «Gehst du spazieren oder gehst du nicht?» — Ты пойдешь гулять или не пойдешь?, так и в конце вопроса, в этом случае ODER будет переводиться как «не так ли?». При этом ODER никак не влияет на порядок слов в вопросе (он отделяется от вопроса запятой и стоит в конце):

Gehst du spazieren, oder? — Ты идешь гулять, не так ли?

Ist das ein Tisch, oder? — Это стол, не так ли?

Стоит отметить, что такая форма постановки вопроса очень распространена в разговорной речи, её очень легко употреблять. Сравним для наглядности все три вида вопросов и их отрицаний:

(нажмите на таблицу для увеличения)

Комбинация вопросов

И наконец, вариант вопросительного предложения, в котором сочетаются несколько вопросительных, например, «Вы не подскажете, который час?»

В таком случае определяется порядок слов в каждом предложении отдельно, а затем они пишутся через запятую (при этом в косвенном вопросе глагол уходит на последнее место):

Könnten Sie bitte sagen? + Wie spät ist es? = Könnten Sie bitte sagen, wie spät es ist?

Выводы по теме:

- В зависимости от контекста вопросы могут быть с вопросительным словом или без него.

- Если вопросительное слово присутствует, то порядок слов: W-слово, сказуемое, подлежащее…?

- Если вопросительного слова нет, то порядок слов: Сказуемое, подлежащее, … ?

- Если к общему вопросу (без W-слова) добавить ODER в конце, то получится альтернативный вопрос.

- Порядок слов в вопросе никак не влияет на отрицание действия (на место nicht в предложении). Об отрицании в немецком мы подробно говорили в статье по ссылке.

Материал готовила

Анна Райхе, команда Deutsch Online

Самые популярные

What is the correct word order for a question in German?

Yes or no questions in German are structured by having the verb in first position, meaning it is the first word of the sentence. The verb is followed immediately by the subject (the person or thing ‘actioning’ the verb).

How do you answer a question in German?

As you can see, asking and answering the question simply requires manipulation of the main verb. At the same time, you can also use conditional responses such as vielleicht (maybe), wahrscheinlich (probably), eigentlich nicht (not really) or any number of other responses.

What is est ce que?

The phrase est-ce que is used to ask a question. Word order stays just the same as it would in an ordinary sentence. Est-ce que comes before the subject, and the verb comes after the subject. So to turn the sentence Tu connais Marie (meaning You know Marie) into a question, all you need to do is to add est-ce que.

Why is Qu est ce que?

Qu’est-ce que asks what when what is the object of the verb — that is, when it receives the action. In Qu’est-ce que tu veux?, tu (you) is the subject of the verb, so there can’t be another subject. Because the interrogative qu’est-ce que can’t be the subject, it must be the object.

Is est ce que formal?

Est-ce que (pronounced “es keu”) is a French expression that is useful for asking a question. It is a slightly informal construction; the more formal or polite way to ask questions is with inversion, which involves inverting the normal pronoun/noun + verb order.

How do you reverse est ce que?

Est-ce que is the inversion of c’est que, literally, “it is that.” Hence the hyphen between est and ce: c’est = ce + est is inverted to est-ce….Essential French Expression.

| Meaning | (turns a statement into a question) | |

|---|---|---|

| Literally | is it that | |

| Register | normal/informal | |

| Pronunciation | [ehs keu] | |

| IPA | [ɛs kə] |

How do you use est ce que and Qu est ce que?

2) Est-ce que… ? “Est-ce que…” is another French way to ask a question. But, while “Qu’est-ce que” asks for “What…?”, “Est-ce que…” (= “Is it that… ?” literally) asks “Is it true that… ?.” It’s an easy way to announce that you’re asking a “Yes / No” question!

What are the French question words?

Useful French question words

- quand (when)

- à quelle heure (at what time)

- qui (who/whom)

- qui est-ce que (who, object of the verb)

- qui est-ce qui (who, subject of the verb)

- avec qui (with whom)

- pour qui (for whom)

- comment (how)

What is your name in French?

If you’d like to say “What is your name?” in French, you generally have two options. To pose the question formally, you’d say “Comment vous-appelez vous? Speaking informally, you can simply ask “Comment t’appelles-tu?”

How do you count 1 to 1000 in French?

Un, deux, trois, c’est parti (one, two, three, here we go)!…

- Un.

- Deux.

- Trois.

- Quatre.

- Cinq.

- Six.

- Sept.

- Huit.

How do you say 20th in French?

These ranks are known by the fancy name of “ordinal numbers”, as opposed to the cardinal numbers, which have already been featured here in the French Blog: French Numbers 1-100….

| The 1st | Le premier if masculin, La première if féminin |

|---|---|

| 20th | vingtième |

| 21st | vingt et unième |

| 22nd | vingt-deuxième |

| 23rd | vingt-troisième |

How do you say 42 in French?

Here are the French Numbers 41-50….French Numbers 41-50.

| Number | French Spelling | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | quarante-deux | kuh-rawnt-duhr |

| 43 | quarante-trois | kuh-rawnt-twah |

| 44 | quarante-quatre | kuh-rawnt-katr |

| 45 | quarante-cinq | kuh-rawnt-sank |

So you have taken some German grammar lessons online, learned your German vocabulary and can decline articles and pronouns and conjugate verbs. Now all that’s left is stringing everything together into understandable sentences.

But how can you learn to navigate the complicated word order in German?

As it is in English, so it is when speaking German: if the order of the words is too wrong, the meaning of the sentence is lost and all you get is gibberish.

Find out more about learning German online.

The best German tutors available

5 (17 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (74 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (5 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (3 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (4 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (17 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (74 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (5 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (3 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (4 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

Why Correct Word Order is Important

Surely if, when learning German, you stick to a simple Subject + Verb + Object sentence, people will understand what you mean, even if it’s not 100% perfect German grammar?

Yes and no. You will probably have trouble balancing vocabulary and grammar in any case, and even an advanced German scholar will sometimes get his cases wrong. And that’s where it gets a little tricky. If you have to choose (and when you are just starting to learn a foreign language, you will), it’s easier to remember word order once than the proper gender of hundreds of words. Get their placement right in the sentence, and most Germans might not even hear that you used the wrong gender or case.

In some cases, word order determines the meaning of a sentence. This is especially true of questions — think of the difference in meaning between the English sentences:

This is a fairytale.

Is this a fairytale?

All the words remain the same, but a change in word order makes the second one into a question, while the first is an assertation.

Also, using a participle right after an auxiliary verb (see further below) is sure to out you as an «Ausländer»! Place your words correctly in a sentence and your German acquaintances are sure to be impressed.

The Right Word Order in German for Main Clauses

Good news for English speakers! In German grammar, the basic sentence structure in a normal main clause is refreshingly like English:

Subject + Verb + Object

«Die Ritterin tötet einen Drachen.»

The female knight kills a dragon.

Also similar to English, the indirect object in German generally comes before the direct object. Where English would say:

The squire gave the (female) knight a lance, German says:

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object

Der Knappe gibt der Ritterin eine Lanze.

Find German language classes near me.

Learn how German and English contrast here.

The Placement of Nouns in German Sentences

This said, the existence of cases in the German language makes word order a bit more fluent than in English, which has confused more than one student of German. For, no matter the word order, the cases will still tell you the noun’s role in the sentence. Generally, this means that a noun can be brought to the beginning of the sentence to emphasise its importance.

Der Knappe gibt der Ritterin eine Lanze.

The squire gives the female knight a lance.

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object

Eine Lanze gab der Knappe der Ritterin.

A lance is what the squire gave the knight.

Direct Object + Verb + Subject + Indirect Object

Der Ritterin gab der Knappe eine Lanze.

The knight was the one to whom the squire gave the lance.

Indirect Object + Verb + Subject + Direct Object

English sometimes does this, too — in poetry («dark was the night…»). But as you can see from the English translations, English often needs to add a word or two for it to work — you couldn’t say: «The lance gave the squire». You might, of course, say: «The lance the squire gave to noble knight», or «To noble knight the squire a lance did give» — but these are all rather uncommon phrases in modern English speech, and we don’t recommend using them in casual conversation!

Join online German classes on Superprof.

How To Structure German Sentences When Using Pronouns

However, in German sentence structure, things are slightly different with personal pronouns.

If ONLY the indirect (dative) object is a pronoun, the word order remains the same:

Er gibt ihr die Lanze.

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object (pronoun) + Direct Object (noun)

He gives the lance to her.

As you can see, the German word order is slightly different than in English sentences having a pronoun as an indirect object!

However, the accusative pronoun comes before the dative object, even if both are pronouns:

Er gibt sie der Ritterin.

Subject + Direct Object (Pronoun) + Indirect Object (noun)

He gives it to the knight.

Er gibt sie ihr.

Subject + Direct Object (pronoun) + Indirect Object (pronoun)

He gives it to her.

The best German tutors available

5 (17 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (74 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (5 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (3 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (4 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (17 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (74 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (16 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (5 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (3 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (4 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

The Place of the Verb in German Main Clauses

You will notice that putting an object in first place does not change the place of the verb in a German sentence. Instead, the subject is shunted to a place behind the verb, leaving the verb always in second place.

Compound Verbs: identifying the place of the auxiliary verbs and the participle

Many German verb tenses rely on the formula:

auxiliary verb (sein or haben) + infinitive or participle

This is similar to several English tenses, such as the continuous tenses, for example (I went vs. I was going).

However, whereas your English lessons at school will have taught you to keep the parts of an English verb together (with the occasional exception of adverbs), German verbs are not as tightly knit. Even in a simple sentence, a German verb can and must be split:

Der Drache hat geschlafen.

The dragon was sleeping.

This subject and verb phrase is simple. However, once we start adding objects, it’s important to remember that while the auxiliary verb remains in second place, the second part of the verb (whether it be an infinitive or a participle) will go to the end of the sentence, no matter what:

Der Ritter hat den Drachen geweckt.

The knight woke the dragon.

Der Ritter hat den Drachen mit einer Tasse Kaffee geweckt.

The knight woke the dragon with a cup of coffee.

Der Ritter hat den Drachen zum Kämpfen um acht Uhr mit einer Tasse Kaffee geweckt.

The knight woke the dragon to fight at eight o’clock with a cup of coffee.

And so on.

This rule applies to regular verbs, irregular verbs, verbs in the past, present or future tense, verbs in the active or in the passive voice — as soon as you have an auxiliary verb, the participle goes to the end of the sentence.

In a verb tense with several auxiliary verbs, the second auxiliary verb goes to the end of the sentence AFTER the participle:

Ich bin getötet worden.

I was killed.

Ich bin von einem Ritter mit einer Lanze getötet worden.

I was killed by a knight with a lance.

The placement of the German verb is one of the most difficult aspects of word order for someone who speaks the English language as their mother tongue. It often makes, not just speaking, but also understanding German difficult. Remember: the rest of the verb is coming! Just wait for it…

Find German lessons to find out more about verb placement.

Knowing Where the Adverbs Go When Writing or Speaking German

Once you introduce adverbs, the cosy little place beside the verb becomes even more coveted. In sentences with only direct objects, the adverb always comes directly after the verb:

Subject + Verb + Adverb Direct Object

Der Knappe reicht schnell die Lanze.

The squire quickly hands over the lance.

BUT it comes AFTER the Indirect Object:

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Adverb + Direct Object

Der Knappe reicht der Ritterin schnell die Lanze.

The squire quickly hands the lance to the knight.

AND it comes AFTER any objects if they are pronouns.

However, the word order remains the same if only the dative (indirect object) is a pronoun:

Der Knappe reicht ihr schnell die Lanze.

The squire quickly hands her the lance.

Subject + Verb + Indirect Object (pronoun) + Adverb + Direct Object

If only the accusative (direct) object is a pronoun, it follows it but slips before the indirect (dative) object:

Der Knappe reicht es schnell der Ritterin.

The squire quickly hands it to the knight.

Subject + Verb + Direct Object (pronoun) + Adverb + Indirect Object

If both objects are pronouns, the adverb slips to last place:

Der Knappe reicht es ihr schnell.

The squire quickly hands it to her.

What to do if you have several adverbs in a sentence?

German generally puts them in the following order:

TIME — MANNER — PLACE

Die Ritterin gallopierte sofort mit angelegter Lanze zum Schlafort des Drachens.

Subject + Verb+ Adverb time + Adverb manner + Adverb place

The knight immediately galloped lance down to the dragon’s sleeping place.

As you can see, the same rules apply whether we are talking about a simple adverb or an adverbial phrase.

How the German Language Builds Subordinate Clauses

In the German language, as in English, if a sentence is made up of two clauses, these are often linked by conjunctions.

If both sentences can stand alone, they are both main clauses and the conjuctions linking them are called coordinating conjunctions (such as “und”, “oder” and «dann»). The word order of either clause is not influenced by the existence of the conjunction; it is treated as though it weren’t there:

Ihr Pferd war schnell und ihre Lanze war scharf.

Her horse was quick and her lance was sharp.

German subordinate clauses

But if one of the sentences can’t stand on its own, it is a subordinate clause. They can be adverbial, or they can function as a direct object to the verb.

They are often introduced by a subordinating conjunction such as «weil», «ob», «wann» etc.

An adverbial clause explains something about the main clause:

Der Drache sah die Ritterin nicht kommen, weil es noch geschlafen hat.

The dragon did not see the knight coming because it was still sleeping.

In learning German, object clauses mostly come after the verbs “wissen”, “fragen” and other verbs indicating knowledge (or lack of it). They are usually introduced with «dass».

Der Drache wußte nicht, dass es bald tot sein wird.

The dragon didn’t know that it would soon be dead.

Die Ritterin erfuhr bald, dass Drachen einen leichten Schlaf haben.

The knight soon found out that dragons are light sleepers.

German subordinating conjunctions and their place in the sentence

Conjunctions for adverb clauses include:

- weil,

- obwohl,

- damit,

- trotzdem,

- dann,

- wenn and others.

Conjunctions for object clauses are:

- dass

- ob,

- wer,

- wieso,

- wieviel…

The conjunctions ALWAYS come at the beginning of the subordinate clause:

Der Drache wachte auf, WEIL er ihr Pferd wiehern hörte.

(MC) The dragon woke up (SC) BECAUSE it heard her horse whinny.

Er fragte sich, WAS dieses Geraucht macht.

(MC) It asked itself (SC) WHAT made that noise.

The Placement of Verbs in German Subordinate Clauses

As an observant student of German, you might have noticed that in ALL subordinate clauses, the verb comes at the very end. If the verb has an auxiliary, the auxiliary verb comes after the main verb:

Er hob seinen Kopf hoch, damit er sehen konnte, was sich ihm näherte.

He raised his head to see what was approaching him.

Photo credit: Brenda-Starr via Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

The exception is in verb cases with more than one auxiliary verb — modal verbs and verbs that take a second infinitive such as “lassen” — in the perfect and past perfect. In such cases, the auxiliary verb sneaks up the line to just before the participle or infinitive:

Sie hätte ihr Pferd gleich umdrehen müssen.

She ought to have turned her horse around immediately.

Sie dachte, dass sie ihr Pferd gleich hätte umdrehen müssen.

She thought that she should have immediately turned her horse around.

Learn more about German Verbs in this dedicated blog

Where Does the Subordinate Clause Go in German Grammar?

While subordinate clauses usually come after the main clause, they can also come first. When you learn German, it is important to remember that they take the place of a noun or adverb, and as such, are considered part of the sentence and modifies word order in a complex sentence.

What does this mean?

It means that if you decide to put the subordinate clause first, the next thing to come in the main clause is the VERB. The subordinate clause takes up the first position in the sentence, so the verb comes in second, and THEN the subject.

In English, subordinate clauses at the beginning of a sentence don’t affect word order in the main clause.

Weil sie so schnell reitete, wusste die Ritterin nicht, ob sie noch rechtzeitig bremsen kann.

(SC1)Because she was going so fast, (MC) the knight didn’t know (SC2)if she would be able to brake.

Here we have two subordinate clauses. The first was shifted to the beginning of the sentence, so in the main clause the verb comes before the subject. The second is in its usual place after the main clause, and everything stays the same.

Find your German language course London.

Use the Imperative in a German Sentence

The imperative is used to give an order or instructions; it is one of the few verb tenses that is only conjugated in the second person (singular and plural) and the first person plural. In German grammar, the imperative is also conjugated in the third person plural — though purely as the formal version of the second person, rather than a true third person.

In German imperative sentences, the verb comes first — as indeed, it does in English grammar:

“Halte dich fest!”

Hang on!

“Töte den Drachen!”

Kill the dragon!

Learn How To Ask a Question in German

There are two types of questions:

- questions that need a question word and

- questions that can be answered yes or no.

Photo credit: Mario Spann via Visualhunt / CC BY-SA

Sentence Structure With German Question Words

How do questions with question words work?

Question words are used whenever sentences need to be clarified. The answer to a question using a question word is usually an adverb or adverb clause within the answer:

When will the knight arrive?

She will arrive at dawn. (Adverb of time)

How does the knight save herself?

She saves herself by spraying hot sauce into the dragon’s nose. (Adverb of means)

Why does she have hot sauce in her saddlebags?

The knight packed hot sauce because she just came from a chilli cook-out. (Adverb of reason)

Where will she go afterwards?

She’ll go to Disneyland! (Adverb of place)

The only exception is the question word «who» (in German «wer»), where the answer is the predicate of a phrase with «to be» («sein»):

Who is this mysterious knight?

She is Joan of Arc’s great-grandniece.

German question words

In the German language, question words always come at the beginning of the question, and are followed by the verb:

Wie rettet die Ritterin sich?

How does the knight save herself?

In this, German is once again close to English, where a question word is followed by the verb: How are you? Where does this go? How much does this cost?

Some of the most common German question words are:

| English word | German translation | Does it need to be declined? |

|---|---|---|

| Who? | Wer? | Yes — it’s a pronoun, so you should decline it to suit its role in the sentence: nominative: Wer accusative: Wen genetive: Wem dative: Wessen Wer is used for feminine and masculine. |

| What? | Was? | no |

| When? | Wann? | no |

| Where? | Wo? | no |

| Why? | Warum? | no |

| How? | Wie? | no |

| How much? | Wieviel? | no |

| How many? | Wie viele? | «viele» should agree with the noun it determines. |

| How old? | Wie alt? | no |

| At what time? | Um wieviel Uhr? | no |

Questions with auxiliary verbs:

As usual, the auxiliary verb is in second place, with the participle coming at the end of the sentence:

Was kann sie tun?

What can she do?

Wie hat sie sich gerettet?

How did she save herself?

How To Build Yes/No Questions in German

English generally needs to use “do” to ask a yes or no question (Do you want the last piece of cake? Do you tango?) or «will» for actions taking place in the future (Will Manchester United win the next game? Will I ever understand German word order?).

However, you will be happy to learn that German does not. In fact, you can take any perfectly normal sentence and simply flip the verb to first position to make it into a question:

Der Drache schnappt zu. -> Schnappt der Drache zu?

The dragon snaps his jaws. -> Does the dragon snap his jaws?

And, of course, two-part verbs remain much the same, with the participle at the end:

Sie kann sich retten. -> Kann sie sich retten?

She can save herself. -> Can she save herself?

Der Knappe rettet sie in letzter Minute. -> Rettet der Knappe sie in letzter Minute?

The squire saves her at the last minute. -> Will the squire save her at the last minute?

As you can see, German sentence structure is similar to English in many instances — making it all the more important that you learn and remember those cases where it isn’t! Sometimes, it is more flexible — long live German cases! — but in others it is more rigid and inflexible. Don’t get hung up on those that seem illogical to you — all languages have their oddities, and German is no exception! Yell at your textbook, then accept it, learn it and move on.

The best way to learn German sentence structure is to see it and hear it used constantly — so look for those German books, blogs, podcasts, audiobooks and movies to make German sentences a part of your daily life. And the best way to practice it is to speak — find a language buddy, look for a German language tutor or — why not? — go to Germany for a holiday!

With these rules, you should soon have no trouble crafting credible German sentences. And fight dragons, too.

Discover the best books and resources for learning German at all levels.

The Rules of German Sentence Structure

By OptiLingo • 6 minute read

Learn the German Word Order Quickly

The only way to reach German fluency is by mastering the sentence structure. Know which rules to create your sentences by makes a big difference. So, we compiled every rule on German sentence structure that you need to succeed. Never question German word order again, just speak fluently with ease.

German Has the Same Sentence Structure as English

This is a great starting point. Since you already know English, mastering German sentence structure will be much easier.

English and basic German sentences both follow the SVO (subject-verb-object) structure. This means that simple sentences will look something like this:

- The dog plays with the ball. – Der Hund spielt mit dem Ball.

The subject is “the dog” (der Hund), the verb is “plays” (spielt), and the object is “the ball” (dem Ball). As you can see, both languages have the same sentence structure. But, German only follows this for simple sentences. Once you say a complex sentence, things change.

German Word Order with Two Verbs

Very often, you’ll have to use two verbs in a sentence in German. Whether you’re speaking in past tense or have a complex idea, it’s best to get used to how it works in a sentence. Luckily, it’s not complicated at all.

One of your verbs will be the dominant one. If you’re talking in the past tense, it’s going to be “haben” (to have). In German, the dominant verb comes first. And this is the one you conjugate. The secondary verb either remains in the infinitive form or conjugated according to the rules of the past tense. Then, you’ll have to place the second verb to the end of the sentence. Although it’s at the end, and it’s not directly conjugated, that’s the verb that gives your sentence it’s meaning, so it’s still the main verb. Let’s take a look at some examples.

- I have rented a bicycle. – Ich habe ein Rad gemietet.

- You must take a detour. – Sie müssen einen Umweg machen.

- Mr. Meier can help you. – Herr Meier kann Ihnen helfen.

Psst! Did you know we have a language learning app?

You’re only one click away!

Forming Questions in German

When you’re asking a question in German, the sentence structure is again very similar to English. Again, if you have two verbs, the first one’s conjugated while the second one goes to the end of the question. But, just like in English, German has question words. These are often called W-Wörter in German, because they all being with a “w”.

German Question Words

- why – warum

- what – was

- when – wann

- how – wie

- where – wo

- where from – woher

- where to – wohin

- who – wer

- who(m) – wen

- whose – wessen

- to/from whom – wem

How to Ask a Question in German

There are two ways to form a question in German. You either use a question word, or you can invert the word order. These examples below show either option.

- Can I rent a car here? – Kann ich hier ein Auto mieten?

- When did you arrive? – Wann sind Sie angekommen?

Inverted Word Order in German

This rule has no real parallel in modern English, although older, poetic English may occasionally contain examples of it. In the simplest of terms, any time a sentence or clause begins with anything other than the subject, that first word is followed immediately by a verb. The subject follows the verb, then come objects and adverbial constructions.

- We drank some wine at the restaurant. – Im Restaurant haben wir Wein getrunken.

- Yesterday we were in Berlin. – Gestern waren wir in Berlin.

The German Sentence Structure With Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that you use to connect two parts of the sentence. Sometimes these two halves are equal, then you use conjunctions such as “und” (and). Other times, one of the sentence halves is dependent of the other. That’s when you need to use word like “wenn” (if) to connect them, and show which one is the dominant sentence.

Now this is where German learners are in a pickle. If a German sentence is made of a dominant and a dependent half (or it begins with conjunction) it becomes the following sentence structure: CSOV (conjunction, subject, object, verb). So, the main verb moves to the end of the sentence.

Common German Conjunctions

- when – als/wenn

- until – bis

- that – dass

- if – wenn/falls

- as if – als ob

- after – nachdem

- before – bevor

- since (as) – da

- since (time) – seitdem

- whether – ob

- although – obwohl

- because – weil

- how – wie

This German word order rule doesn’t just happen when the conjunction is at the beginning of the sentence. It also happens when the conjunction appears as a clause within the sentence. So, when that happens, you need to use inverted word order at the second half of the sentence. The following examples can show you how it’s done.

- He says that the have no vacant rooms – Er sagt, dass kein Zimmer frei ist.

- I don’t know whether people come today. – Ich weiss nicht, ob heute Leute kommen.

Negating Statements in German

In English, affirmative statements are negated by inserting the words “not” or “no”. German works in a similar manner using the words “nicht” and “kein”. For example:

- I can sing. – Ich kann singen.

- I cannot sing. – Ich kann night singen.

- I have money. – Ich habe Geld.

- I have no money. – Ich habe kein Geld.

Learn German Sentence Structure From Everyday Phrases

Understanding German sentence structure isn’t that difficult. But, you need to master forming sentences to reach German fluency. So, the best way to learn the word order rules is by seeing them in their natural habitat. Everyday phrases and expressions all include the grammar rules you just learned. And to find the list of the most useful German phrases, all you need to do is download OptiLingo.

OptiLingo has the only vocabulary list you’ll need to reach fluency. And, it also makes you speak the language. This means that you’ll build your confidence and speaking skills while you’re learning useful vocabulary. To discover the secrets to German sentence structure, download OptiLingo today!