Definition of Pun

A pun is a literary device that is also known as a “play on words.” Puns involve words with similar or identical sounds but with different meanings. Their play on words also relies on a word or phrase having more than one meaning. Puns are generally intended to be humorous, but they often have a serious purpose as well in literary works.

For example, if you were to attend a lecture about managing finances entitled “Common Cents,” this features a pun. The play on words is between “cents,” as in coins, and “sense,” as in awareness. This pun is also effective as a play on words of the phrase “common sense,” which is appropriate to the subject of managing finances.

Common Examples of Puns

Here are some examples of puns that may be found in everyday expression:

- Denial is a river in Egypt.

- The cyclist was two tired to win the race.

- Take my wife, please.

- Her cat is near the computer to keep an eye on the mouse.

- When my algebra teacher retired, he wasn’t ready for the aftermath.

- Some bunny loves you.

- Now that I have graph paper, I guess it’s time to plot something.

- Make like a tree and leave.

- This candy cane is in mint condition.

- My librarian is a great bookkeeper.

- This vacuum sucks.

- I like archery, but it’s hard to see the point.

- It’s easy to like musicians because they are very upbeat.

- If you stand by the window, I’ll help you out.

- The population of Ireland is always Dublin.

- It’s difficult for crabs to share because they are shellfish.

- Hand me that newspaper so we don’t have crosswords.

- The skeleton model in our biology class is a bonehead.

- The wedding cake had me in tiers.

- Next year, I’ll spend more thyme growing herbs.

Examples of Puns as Character Names

Writers often make clever use of puns when it comes to naming characters. This can provide humor and/or a sense of irony for the reader.

For example, in an episode of the animated series “The Tick,” one of the villains is named “El Seed.” El Seed is the leader of an army that intends to “liberate” the plant population. This is a clever use of pun for a character name, as it is both a play on the word “seed” in relation to plants and a play on the legend of El Cid, a medieval Spanish knight, and military warrior.

Here are some other examples of puns as character names:

- Cliff Hanger (adventure character from children’s television series “Between the Lions”)

- Gnomeo and Juliet (animated adaptation of “Romeo and Juliet”)

- Harley Quinn (fictional character in DC Comics)

- Truly Scrumptious (“Chitty Chitty Bang Bang”)

- Kim Possible (heroic character from children’s television series of the same name)

- Sugar Kane Kowalczyk (“Some Like It Hot”)

- Paige Turner (librarian character from children’s television series “Arthur”)

- Alfredo Linguini (chef character in Disney’s “Ratatouille”)

- Holly Golightly (“Breakfast at Tiffany’s”)

- Cruella De Vil (“101 Dalmatians”)

Famous Examples of Pun

Here are some famous examples of puns:

- “The road to success is always under construction.” (Lily Tomlin)

- “Atheism is a non-prophet organization.” (George Carlin)

- “I am a very committed wife. And I should be committed too – for being married so many times.” (Elizabeth Taylor)

- “The cafeteria staff requests sidekicks stop ordering hero sandwiches.” (from the motion picture “Sky High”)

- “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.” (Dorothy Parker)

Difference Between Pun and Joke

It can be difficult for people to distinguish between puns and jokes. This is understandable since they are similar in nature, yet they are not the same. Puns are figures of speech that rely on a form of word play, whereas jokes are narrative structures intended to create humor and laughter.

For example, the structure of a joke is generally dependent upon a “set up” followed by a “punchline.” A punchline delivers the humor of a joke by relieving the tension of the narrative set up through an unlikely or incongruous resolution. This punchline “twist” is intended to induce laughter from an audience.

Here is an example of a well-known joke from the “Monty Python” series:

First Person: “My dog has no nose.”

Second Person: “How does he smell?”

First Person: “Awful!”

The set up for this joke is that a person’s dog is without a nose, creating wonder in the second person (and the audience, vicariously) as to how the dog uses its sense of smell with no nose. Instead, the person with the dog interprets the second person’s question as a query about the quality of smell of the dog itself. The punchline “Awful!” relieves the tension of the narrative in that the question is answered. The punchline is humorous in that the answer is unexpected.

Though both jokes and puns are forms of humor, jokes frequently rely on comedic rhythm and timing. Puns, however, rely on word play and meanings.

Writing Pun

Many writers and poets such as John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, and Ambrose Bierce have claimed that puns are the “lowest form” of humor and wit. Those who agree with this sentiment justify it by pointing out that puns are often not genuinely funny and can be grimace-inducing for readers. In addition, puns frequently happen by accident when we are speaking, which is why the phrase “no pun intended” is said so often. People tend to consider puns as unnecessary or frivolous.

However, it’s quite challenging to create an effective pun when writing. There are two main reasons for this difficulty:

- First, the reader must understand the “source material” of the pun in order for it to work. This would include understanding different meanings of words or phrases, or recognizing an allusion or reference. For example, Warren Peace is a character name that features a pun. In order for the play on words to be effective with this pun, a reader must be familiar with the source material. In this case, the pun relies on the reader’s prior knowledge of Leo Tolstoy’s famous novel War and Peace. If a reader has no familiarity with Tolstoy’s work, the pun would be an ineffective literary device without meaning.

- The second challenge when it comes to creating an effective pun in writing is adding value for the reader. In other words, when a writer utilizes a pun simply for the sake of incorporating a play on words, this doesn’t enhance literary value or enjoyment for the reader. However, if a writer’s use of word play adds meaning to the text by elevating a sense of comedy, tragedy, or irony, then puns can create value and appreciation among readers.

Here are some reasons that writers incorporate puns into their works:

Evoke Humorous Response

For the most part, writers use puns to evoke a humorous response among their readers. This is due to the ambiguous and/or difference in meanings for certain words and phrases. These differences in meanings may originate from figurative language or use of homophone or homograph.

Enhance Interpretation

Puns, when used effectively, can enhance the interpretation of literary works. A pun will often cause a reader to think about various meanings of a word or phrase. In turn, this can result in the reader expanding their interpretation of the literary work itself in order to find deeper meanings.

Artistic and Clever Use of Language

Like all figures of speech, puns represent artistic and clever use of language on the part of the writer. However, puns should be used sparingly so as not to overwhelm or disengage a reader. In addition, it’s important for writers to understand that puns are often limited to a particular language and would not necessarily be effective in translation.

Intended and Unintended Pun

Sometimes authors and characters use words in some contexts which have possibly several meanings but the readers are likely to deduce the meanings which its use does not mean. This is an unintended use of puns or it is called a pun unintended. However, sometimes writers, speakers, and characters intentionally use words having double meanings to create laughter. The puns used by Hamlet are intentional. However, when there is no such intention, such puns are unintentional.

When to use pun intended or no pun intended

It’s simple and easy to remember ‘pun intended’ is used when you want to add a double meaning and show off your word skills! You can use ‘no pun intended when you use a pun in a serious situation when it is not well received or you are trying to defend yourself for using pun during your talks.

Using Pun in a Sentence

- My fat friend did not buy a belt, thinking it is a waist of time.

- All the people are combing the area to find the escaped hares.

- People following Santa Claus are often called subordinate clauses.

- It is not obvious to him why he cannot beat a boiled egg.

- It is pointless to write with a broken pencil.

Examples of Pun in Literature

A pun can be an effective literary device. Here are some examples of puns in well-known literary works, along with how they add to interpretation:

Example 1: The Importance of Being Earnest (Oscar Wilde)

To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”

Wilde was a master of word play, and this line from his play “The Importance of Being Earnest” reflects his dexterity when it comes to pun as a literary device. Of course, Wilde is playing on the dual meaning of “lose.” In its first mention, lose is used in the context of suffering loss through death. In its second mention, lose is used in the context of misplacing something.

There is layered humor provided by the pun in this line. The reader understands that Mr. Worthing has lost one parent to death, and the suggestion that the loss of both his parents is due to misplacement reflects dark humor. In addition, Wilde’s use of the word “carelessness” is clever wording as well. The idea that the speaker is poking fun at death also emphasizes the speaker’s lack of care, and therefore carelessness, with his words.

Example 2: Romeo and Juliet (William Shakespeare)

ask for me tomorrow and you shall find me a grave man.

William Shakespeare is known for his clever use of puns for comedic effect. Yet he also utilized this literary device as a means of enhancing tragic and ironic circumstances as well. Romeo’s dear friend Mercutio is stabbed by Tybalt, and makes this statement during his death scene. Shakespeare creates a play on the word grave that adds a level of tragedy and sense of irony to Mercutio’s death.

Mercutio’s pun relies on the dual meanings of the word “grave.” As an adjective, grave describes something that is serious or solemn. This meaning fits with Mercutio’s statement, as being stabbed is certainly a grave event. As a noun, a grave indicates a place of burial for a dead body and more specifically the area dug in the ground for internment. This meaning also fits with Mercutio’s situation, as his stab wound is fatal. Therefore, Mercutio’s pun is a play on words that enhances what has befallen him as well as the outcome.

Example 3: Pragmatist (Edmund Conti)

Apocalypse soon

Coming our way

Ground zero at noon

Halve a nice day.

In Conti’s poem, the speaker offers a pun based on the word “halve” and its homophone “have” in the last line. Phonetically, the last line reads as “have a nice day.” This cliche is an ironic finish to the poem considering its subject is an impending apocalypse and the world’s end. However, the poet’s use of the word “halve” rather than “have” is a clever way of supporting the rest of the poem. If “ground zero” of the apocalypse is “at noon,” then it is only possible to have half of a day. Therefore, “halve” a nice day is a much more accurate, though ironic, end to the poem.

Example 4: Design (Robert Frost)

What had the flower to do with being white,

The wayside blue and innocent heal-all?

What brought the kindred spider to that height,

Then steered the white moth thither in the night?

What but design of darkness to appall? –

If design govern in a thing so small.

In the last stanza of this poem, Frost uses pun as a figure of speech through the word “design.” Rather than an attempt at humor, the pun in this poem causes the reader to think more deeply about the meaning of design and the meaning of the poem as well. On one level, the poet is questioning the “design of darkness,” meaning its composition and construction. This is paired with the second use of “design” in the context of an intentional or deliberate plan. In other words, the poet wonders whether the natural design (composition) of the relationship between the flower, moth, and spider has resulted in the moth’s death, or whether it is nature’s design (plan) that governs the plight of the moth.

On other levels, the meaning of “design” in the poem might refer to Intelligent Design or the theory of divine presence in nature. Similarly, the word design may reflect the poetic process itself. The poet may also be questioning whether the poem is an artistic composition on its own or if he is the ultimate designer of the poem.

Synonyms of Pun

Although no word comes close to pun in meanings, it has several synonyms. Some of its synonyms are wordplay, double meaning, innuendo, witticism, quip, double entendre, and quibble.

Punch, February 25, 1914. The cartoon is a pun on the word «Jamaica».

A pun, also known as paronomasia, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect.[1] These ambiguities can arise from the intentional use of homophonic, homographic, metonymic, or figurative language. A pun differs from a malapropism in that a malapropism is an incorrect variation on a correct expression, while a pun involves expressions with multiple (correct or fairly reasonable) interpretations. Puns may be regarded as in-jokes or idiomatic constructions, especially as their usage and meaning are usually specific to a particular language or its culture.

Puns have a long history in writing. For example, the Roman playwright Plautus was famous for his puns and word games.[2][3]

Types of puns[edit]

Homophonic[edit]

A homophonic pun is one that uses word pairs which sound alike (homophones) but are not synonymous.[4] Walter Redfern summarized this type with his statement, «To pun is to treat homonyms as synonyms.»[5] For example, in George Carlin’s phrase «atheism is a non-prophet institution», the word prophet is put in place of its homophone profit, altering the common phrase «non-profit institution». Similarly, the joke «Question: Why do we still have troops in Germany? Answer: To keep the Russians in Czech» relies on the aural ambiguity of the homophones check and Czech. Often, puns are not strictly homophonic, but play on words of similar, not identical, sound as in the example from the Pinky and the Brain cartoon film series: «I think so, Brain, but if we give peas a chance, won’t the lima beans feel left out?» which plays with the similar—but not identical—sound of peas and peace in the anti-war slogan «Give Peace a Chance».[6]

Homographic[edit]

A homographic pun exploits words that are spelled the same (homographs) but possess different meanings and sounds. Because of their origin, they rely on sight more than hearing, contrary to homophonic puns. They are also known as heteronymic puns. Examples in which the punned words typically exist in two different parts of speech often rely on unusual sentence construction, as in the anecdote: «When asked to explain his large number of children, the pig answered simply: ‘The wild oats of my sow gave us many piglets.'» An example that combines homophonic and homographic punning is Douglas Adams’s line «You can tune a guitar, but you can’t tuna fish. Unless of course, you play bass.» The phrase uses the homophonic qualities of tune a and tuna, as well as the homographic pun on bass, in which ambiguity is reached through the identical spellings of (a string instrument), and (a kind of fish). Homographic puns do not necessarily need to follow grammatical rules and often do not make sense when interpreted outside the context of the pun.

Homonymic[edit]

Homonymic puns, another common type, arise from the exploitation of words that are both homographs and homophones. The statement «Being in politics is just like playing golf: you are trapped in one bad lie after another» puns on the two meanings of the word lie as «a deliberate untruth» and as «the position in which something rests». An adaptation of a joke repeated by Isaac Asimov gives us «Did you hear about the little moron who strained himself while running into the screen door?» playing on strained as «to give much effort» and «to filter».[7] A homonymic pun may also be polysemic, in which the words must be homonymic and also possess related meanings, a condition that is often subjective. However, lexicographers define polysemes as listed under a single dictionary lemma (a unique numbered meaning) while homonyms are treated in separate lemmata.

Compounded[edit]

A compound pun is a statement that contains two or more puns. In this case, the wordplay cannot go into effect by utilizing the separate words or phrases of the puns that make up the entire statement. For example, a complex statement by Richard Whately includes four puns: «Why can a man never starve in the Great Desert? Because he can eat the sand which is there. But what brought the sandwiches there? Why, Noah sent Ham, and his descendants mustered and bred.»[8] This pun uses sand which is there/sandwiches there, Ham/ham, mustered/mustard, and bred/bread. Similarly, the phrase «piano is not my forte» links two meanings of the words forte and piano, one for the dynamic markings in music and the second for the literal meaning of the sentence, as well as alluding to «pianoforte», the older name of the instrument. Compound puns may also combine two phrases that share a word. For example, «Where do mathematicians go on weekends? To a Möbius strip club!» puns on the terms Möbius strip and strip club.

Recursive[edit]

A recursive pun is one in which the second aspect of a pun relies on the understanding of an element in the first. For example, the statement «π is only half a pie.» (π radians is 180 degrees, or half a circle, and a pie is a complete circle). Another example is «Infinity is not in finity», which means infinity is not in finite range. Another example is «a Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean your mother.»[9] The recursive pun «Immanuel doesn’t pun, he Kant», is attributed to Oscar Wilde.[2]

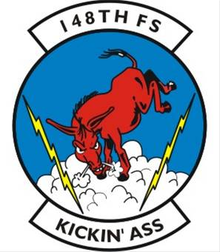

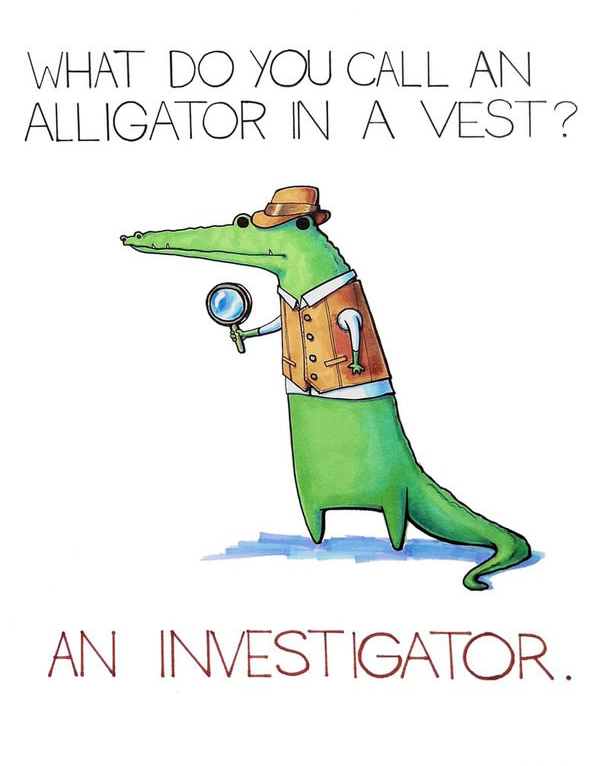

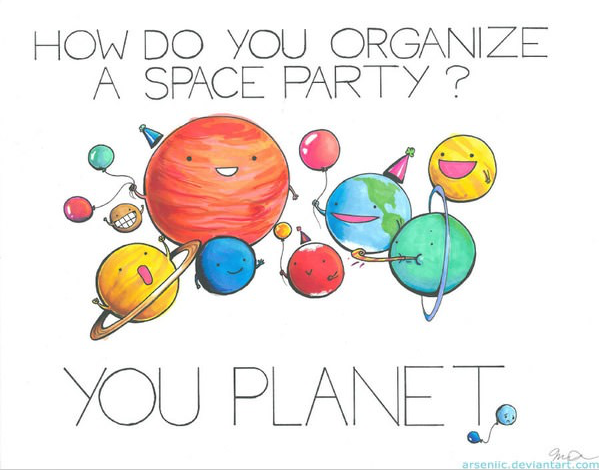

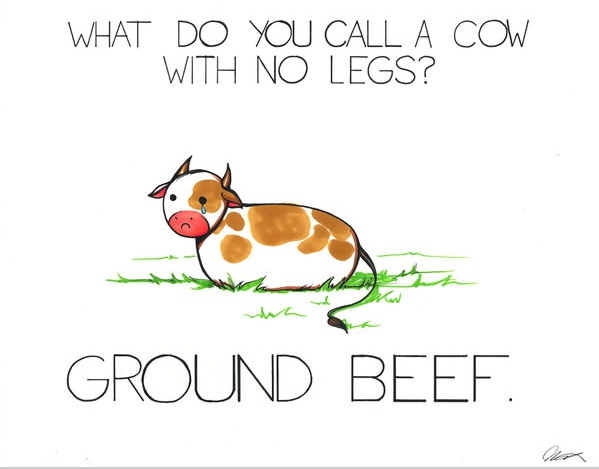

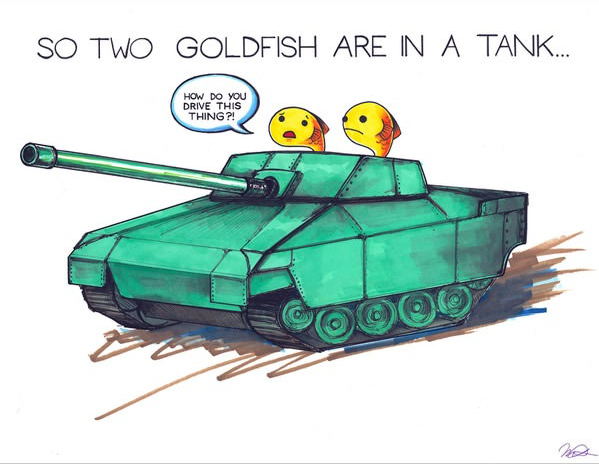

Visual[edit]

148th Fighter Squadron emblem, a visual pun in which the squadron’s motto, «Kickin’ Ass», is depicted literally as an ass in the act of kicking even though «kicking ass» is a colloquial expression for winning decisively or being impressive.

Visual puns are sometimes used in logos, emblems, insignia, and other graphic symbols, in which one or more of the pun aspects is replaced by a picture. In European heraldry, this technique is called canting arms. Visual and other puns and word games are also common in Dutch gable stones as well as in some cartoons, such as Lost Consonants and The Far Side. Another type of visual pun exists in languages that use non-phonetic writing. For example, in Chinese, a pun may be based on a similarity in shape of the written character, despite a complete lack of phonetic similarity in the words punned upon.[10] Mark Elvin describes how this «peculiarly Chinese form of visual punning involved comparing written characters to objects.»[11]

Visual puns on the bearer’s name are used extensively as forms of heraldic expression, they are called canting arms. They have been used for centuries across Europe and have even been used recently by members of the British royal family, such as on the arms of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and of Princess Beatrice of York. The arms of U.S. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Dwight D. Eisenhower are also canting.[citation needed] In the context of non-phonetic texts, 4 Pics 1 Word, is an example of visual paronomasia where the players are supposed to identify the word in common from the set of four images.[12]

Other[edit]

Richard J. Alexander notes two additional forms that puns may take: graphological (sometimes called visual) puns, such as concrete poetry; and morphological puns, such as portmanteaux.[13]

Use[edit]

Comedy and jokes[edit]

Puns are a common source of humour in jokes and comedy shows.[14] They are often used in the punch line of a joke, where they typically give a humorous meaning to a rather perplexing story. These are also known as feghoots. The following example comes from the movie Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, though the punchline stems from far older Vaudeville roots.[15] The final line puns on the stock phrase «the lesser of two evils». After Aubrey offers his pun (to the enjoyment of many), Dr. Maturin shows a disdain for the craft with his reply, «One who would pun would pick-a-pocket.»

Captain Aubrey: «Do you see those two weevils, Doctor?…Which would you choose?»

Dr. Maturin: «Neither. There’s not a scrap of difference between them. They’re the same species of Curculio.»

Captain Aubrey: «If you had to choose. If you were forced to make a choice. If there were no other option.»

Dr. Maturin: «Well, then, if you’re going to push me. I would choose the right-hand weevil. It has significant advantage in both length and breadth.»

Captain Aubrey: «There, I have you!…Do you not know that in the Service, one must always choose the lesser of the two weevils.»

Not infrequently, puns are used in the titles of comedic parodies[citation needed]. A parody of a popular song, movie, etc., may be given a title that hints at the title of the work being parodied, replacing some of the words with ones that sound or look similar. For example, collegiate a cappella groups are often named after musical puns to attract fans through attempts at humor.[16] Such a title can immediately communicate both that what follows is a parody and also that work is about to be parodied, making any further «setup» (introductory explanation) unnecessary.

2014 saw the inaugural UK Pun Championships, at the Leicester Comedy Festival, hosted by Lee Nelson.[17] Walsh went on to take part in the O. Henry Pun-Off World Championships in Austin, Texas.[18] In 2015 the UK Pun Champion was Leo Kearse.[19]

Books never written[edit]

Sometimes called «books never written» or «world’s greatest books», these are jokes that consist of fictitious book titles with authors’ names that contain a pun relating to the title.[20] Perhaps the best-known example is: «Tragedy on the Cliff by Eileen Dover», which according to one source was devised by humourist Peter DeVries.[21] It is common for these puns to refer to taboo subject matter, such as «What Boys Love by E. Norma Stitts».[20]

Literature[edit]

Non-humorous puns were and are a standard poetic device in English literature. Puns and other forms of wordplay have been used by many famous writers, such as Alexander Pope,[22] James Joyce,[23] Vladimir Nabokov,[24] Robert Bloch,[25] Lewis Carroll,[26] John Donne,[27] and William Shakespeare.

In the poem A Hymn to God the Father, John Donne, whose wife’s name was Anne More, puns repeatedly: «Son/sun» in the second quoted line, and two compound puns on «Done/done» and «More/more». All three are homophonic, with the puns on «more» being both homographic and capitonymic. The ambiguities introduce several possible meanings into the verses.

«When Thou hast done, Thou hast not done / For I have more.

that at my death Thy Son / Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore

And having done that, Thou hast done; / I fear no more.»

Alfred Hitchcock stated, «Puns are the highest form of literature.»[28]

Shakespeare[edit]

Shakespeare is estimated to have used over 3,000 puns in his plays.[29] Even though many of the puns were bawdy, Elizabethan literature considered puns and wordplay to be a «sign of literary refinement» more so than humor. This is evidenced by the deployment of puns in serious or «seemingly inappropriate» scenes, like when a dying Mercutio quips «Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man» in Romeo and Juliet.[30]

Shakespeare was also noted for his frequent play with less serious puns, the «quibbles» of the sort that made Samuel Johnson complain, «A quibble is to Shakespeare what luminous vapours are to the traveller! He follows it to all adventures; it is sure to lead him out of his way, sure to engulf him in the mire. It has some malignant power over his mind, and its fascinations are irresistible.»[31] Elsewhere, Johnson disparagingly referred to punning as the lowest form of humour.[32]

Rhetoric[edit]

Puns can function as a rhetorical device, where the pun serves as a persuasive instrument for an author or speaker. Although puns are sometimes perceived as trite or silly, if used responsibly a pun «can be an effective communication tool in a variety of situations and forms».[33] A major difficulty in using puns in this manner is that the meaning of a pun can be interpreted very differently according to the audience’s background with the possibility of detracting from the intended message.[34]

Design[edit]

Like other forms of wordplay, paronomasia is occasionally used for its attention-getting or mnemonic qualities, making it common in titles and the names of places, characters, and organizations, and in advertising and slogans.[35][36]

The Tiecoon Tie shop, in Penn Station NY, an example of a pun in a shop name

Many restaurant and shop names use puns: Cane & Able mobility healthcare, Sam & Ella’s Chicken Palace, Tiecoon tie shop, Planet of the Grapes wine and spirits,[37] Curl Up and Dye hair salon, as do books such as Pies and Prejudice, webcomics like (YU+ME: dream) and feature films such as (Good Will Hunting). The Japanese anime Speed Racer’s original Japanese title, Mach GoGoGo! refers to the English word itself, the Japanese word for five (the Mach Five’s car number), and the name of the show’s main character, Go Mifune. This is also an example of a multilingual pun, full understanding of which requires knowledge of more than one language on the part of the listener.

Names of fictional characters also often carry puns, such as Satoshi’s English name, Ash Ketchum and Goku («Kakarrot»), the protagonists of the anime series based on the video game series Pokémon and the manga series Dragon Ball, respectively, both franchises that are known for including second meanings in the names of many of their characters. A recurring motif in the Austin Powers films repeatedly puns on names that suggest male genitalia. In the science fiction television series Star Trek, «B-4» is used as the name of one of four androids models constructed «before» the android Data, a main character. A librarian in another Star Trek episode was named «Mr. Atoz» (A to Z).

The parallel sequel The Lion King 1½ advertised with the phrase «You haven’t seen the 1/2 of it!». Wyborowa Vodka employed the slogan «Enjoyed for centuries straight», while Northern Telecom used «Technology the world calls on.»[35]

On 1 June 2015 the BBC Radio 4 You and Yours included a feature on «Puntastic Shop Titles». Entries included a Chinese Takeaway in Ayr town centre called «Ayr’s Wok», a kebab shop in Ireland called «Abra Kebabra» and a tree-surgeon in Dudley called «Special Branch». The winning entry, selected by Lee Nelson, was a dry cleaner’s in Fulham and Chelsea called «Starchy and Starchy», a pun on Saatchi & Saatchi.[38]

In the media[edit]

Paronomasia has found a strong foothold in the media. William Safire of The New York Times suggests that «the root of this pace-growing [use of paronomasia] is often a headline-writer’s need for quick catchiness, and has resulted in a new tolerance for a long-despised form of humor.»[39] It can be argued that paronomasia is common in media headlines, to draw the reader’s interest. The rhetoric is important because it connects people with the topic. A notable example is the New York Post headline «Headless Body in Topless Bar».[40]

Paronomasia is prevalent orally as well. Salvatore Attardo believes that puns are verbal humor. He talks about Pepicello and Weisberg’s linguistic theory of humor and believes the only form of linguistic humor is limited to puns.[41] This is because a pun is a play on the word itself. Attardo believes that only puns are able to maintain humor and this humor has significance. It is able to help soften a situation and make it less serious, it can help make something more memorable, and using a pun can make the speaker seem witty.

Paronomasia is strong in print media and oral conversation so it can be assumed that paronomasia is strong in broadcast media as well. Examples of paronomasia in media are sound bites. They could be memorable because of the humor and rhetoric associated with paronomasia, thus making the significance of the soundbite stronger.

Confusion and alternative uses[edit]

There exist subtle differences between paronomasia and other literary techniques, such as the double entendre. While puns are often simple wordplay for comedic or rhetorical effect, a double entendre alludes to a second meaning that is not contained within the statement or phrase itself, often one that purposefully disguises the second meaning. As both exploit the use of intentional double meanings, puns can sometimes be double entendres, and vice versa. Puns also bear similarities with paraprosdokian, syllepsis, and eggcorns. In addition, homographic puns are sometimes compared to the stylistic device antanaclasis, and homophonic puns to polyptoton. Puns can be used as a type of mnemonic device to enhance comprehension in an educational setting. Used discreetly, puns can effectively reinforce content and aid in the retention of material. Some linguists have encouraged the creation of neologisms to decrease the instances of confusion caused by puns.[42]

History and global usage[edit]

Puns were found in ancient Egypt, where they were heavily used in the development of myths and interpretation of dreams.[43]

In China, Shen Dao (ca. 300 BC) used «shi», meaning «power», and «shi», meaning «position» to say that a king has power because of his position as king.[44]

In ancient Mesopotamia around 2500 BC, punning was used by scribes to represent words in cuneiform.[45]

The Tanakh contains puns.[46]

The Maya are known for having used puns in their hieroglyphic writing, and for using them in their modern languages.[47]

In Japan, «graphomania» was one type of pun.[48]

In Tamil, «Sledai» is the word used to mean pun in which a word with two different meanings. This is also classified as a poetry style in ancient Tamil literature. Similarly, in Telugu, «Slesha» is the equivalent word and is one of several poetry styles in Telugu literature.

See also[edit]

- Aesopian language

- Albur

- Alliteration

- Auto-antonym

- Dad joke

- Dajare

- Double entendre

- False etymology

- Mondegreen

- Phono-semantic matching

- Satiric misspelling

- Spoonerism

- Tom Swifty

Notes[edit]

- ^ «paronomasia». rhetoric.byu.edu. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b Pollack, John (14 April 2011). The Pun Also Rises. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-51386-6.

- ^ Fontaine, Michael (2010). Funny Words in Plautine Comedy. Oxford University Press.

- ^ «English Grammar Lesson – How very pun-ny of you! – ELC». ELC – English Language Center. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Puns, Blackwell, London, 1984

- ^ See the citation on Wikiquote

- ^ Asimov, Isaac. Isaac Asimov’s Treasury of Humor, p. 175, § 252. 1971. Houghton Mifflin. New York.

- ^ Tartakovsky, Joseph (28 March 2009). «Pun for the Ages». The New York Times.

- ^ «PUNS». Tnellen.com. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Attardo, Salvatore. Linguistic Theories of Humor, p.109. Walter de Gruyter, 1994. Alleton, V.: L’écriture chinoise. Paris, 1970.

- ^ Elvin, Mark, «The Spectrum of Accessibility: Types of Humor in The Destinies of the Flowers in the Mirror«, p. 113. In: Roger T. Ames (et al.): Interpreting Culture through Translation: a Festschrift for D. C. Lau. 1991, pp. 101–118.

- ^ «Paronomasia — Definition and Examples of Paronomasia». Literary Devices. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Richard J. (1997). Aspects of Verbal Humour in English. Narr, Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. pp. 21–41. ISBN 978-3-823-34936-5.

- ^ Worth, Dan (15 May 2008). «Gluttons for pun-ishment». The Guardian.

- ^ Levitt, Paul M. (2002). Vaudeville Humor: The Collected Jokes, Routines, and Skits of Ed Lowry. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2720-1.

- ^ Chin, Mike (18 May 2011). «How Many A Cappella Group Names are Puns? | The A Cappella Blog». acappellablog.com. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Collins, Gemma (14 February 2014). «Comedy Festival Review: The UK Pun Championships at Just The Tonic». Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ «Dave’s Leicester Comedy Festival». Comedy-festival.co.uk. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ «Leo Kearse: Comedian and Writer». leokearse.co.uk. Leo Kearse. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ a b Partington, Alan (2006). The Linguistics of Laughter: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Laughter-Talk. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-41538166-6.

- ^ Booth, David (1990). Writers on Writing: Guide to Writing and Illustrating Children’s Books. Grolier Limited. p. 83. ISBN 978-0717223930.

- ^ Nichol, Donald W, ed. (30 November 2015). Anniversary Essays on Alexander Pope’s ‘The Rape of the Lock’. University of Toronto Press. pp. 21, 41, 81, 102, 136, 141, 245. ISBN 9781442647961. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Menand, Louis (2 July 2012). «Silence, Exile, Punning: James Joyce’s chance encounters». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (1 December 2005). «Hurricane Lolita». The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Zinna, Eduardo (2013). «Yours Truly, Robert Bloch». Casebook.org. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Appleton, Andrea (23 July 2015). «The Mad Challenge of Translating «Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland»«. Smithsonian. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Kaveney, Roz (2 July 2012). «John Donne, priest and poet, part 7: puns in defiance of reason». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ The Dick Cavett Show (Television production). United States: American Broadcasting Company. Event occurs at 8 June 1972.

- ^ Colbyry, Thomas. «Examples of Puns in Shakespeare’s Writings». Entertainment Guide. Demand Media. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Tartakovsky, Joseph (28 March 2009). «Pun for the Ages». The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Samuel Johnson, Preface to Shakespeare.

- ^ Rogers, Bruce (1999). You Can Say That Again!. Dundurn. p. 95. ISBN 9781554880386.

- ^ Junker, Dave (February 2013). «In Defense of Puns: How to Use them Effectively». Public Relations Tactics. 20 (2): 18.

- ^ Djafarova, Elmira (June 2008). «Why Do Advertisers Use Puns? A Linguistic Perspective». Journal of Advertising Research. 48 (2): 267–275. doi:10.2501/s0021849908080306. S2CID 167457581.

- ^ a b «The Art and Science of the Advertising Slogan». Adslogans.co.uk. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Collins, Michelle (6 June 2008). «The 50 Best Pun Stores». BestWeekEver.tv. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ «Financial Abuse, Ikea Complaints, Damart Marketing, You and Yours». BBC Radio 4. BBC. 1 June 2015.

- ^ Safire, W. (1980). «On Language: A Barrel of Puns». The New York Times. p. SM2.

- ^ Vincent, Musetto (9 June 2015). «Vincent Musetto, 74, dies». The New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ van Mulken, Margot; Renske van Enschot-van Dijk; Hans Hoeken (May 2005). «Puns, relevance and appreciation in advertisements». Journal of Pragmatics. 37 (5): 707–721. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.946.7625. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2004.09.008.

- ^ Shakespeare Survey – Volume 23 – Page 19, Kenneth Muir – 2002

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine Pinch (1995), Magic in ancient Egypt, University of Texas Press, p. 68.

- ^ Waley, Arthur (1982), Three ways of thought in ancient China Stanford University Press, p. 81.

- ^ Robson, Eleanor (2008), Mathematics in ancient Iraq: a social history, Princeton University Press, p. 31.

- ^ Whedbee, J. William (28 May 1998). The Bible and the Comic Vision. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521495073. Retrieved 7 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Danien, Elin C.; Robert J. Sharer (1993), New theories on the ancient Maya, University of Pennsylvania. University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, p. 99.

- ^ Brown, Delmer M.; John Whitney Hall (eds), The Cambridge History of Japan: Ancient Japan, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 463.

References[edit]

- Augarde, Tony (1984). The Oxford Guide to Word Games. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-214144-6.

- Hempelmann, Christian F. (September 2004). «Script opposition and logical mechanism in punning». Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 17 (4): 381–392. doi:10.1515/humr.2004.17.4.381. S2CID 144409644. (access restricted)

Definition of Pun

A pun is a play on words which usually hinges on a word with more than one meaning or the substitution of a homonym that changes the meaning of the sentence for humorous or rhetorical effect. For example, here’s a well-known pun: “Corduroy pillows are making headlines.” The word “headlines” usually refers to something that is new and popular, but this pun changes the meaning in that after having slept on a corduroy pillow, a person would wake up with lines on their heads. Another well-known pun is, “When a vulture flies he takes carrion luggage.” In this pun, the words “carrion” and “carry on” are homonyms; humans take “carry on” luggage when we fly on planes, while vultures eat “carrion” and may take it with them when they fly.

Another word for pun is paronomasia, which comes from the Greek word paronomazein, which meant, “to make a change in naming.”

Types of Puns

There are several different types of puns. Here are some of the different classifications of puns:

- Homophonic pun: This type of pun uses homonyms (words that sound the same) with different meanings. For example: “The wedding was so emotional that even the cake was in tiers.” The professor Walter Redfern said of this type of pun, “To pun is to treat homonyms as synonyms.”

- Homographic pun: This type of pun uses words that are spelled the same but sound different. These puns are often written rather than spoken, as they briefly trick the reader into reading the “wrong” sound. For example, “You can tune a guitar, but you can’t tuna fish. Unless you play bass.” In this case, “tuna fish” is a homophonic pun because it is a homonym for “tune a.” The word “bass,” though, functions as a homographic pun in that the word “bass” pronounced with a long “a” refers to a type of instrument while “bass” pronounced with a short “a” is a type of fish.

- Homonymic pun: A homonymic pun contains aspects of both the homophonic pun and the homographic pun. In this type of pun, the wordplay involves a word that is spelled and sounds the same, yet has different meanings. For example, “Two silk worms had a race and ended in a tie.” A “tie” can of course either be when neither party wins, but in this pun also refers to the piece of clothing usually made from silk.

- Compound pun: A compound pun includes more than one pun. Here is a famous compound pun from English rhetorician and theologian Richard Whately: “Why can a man never starve in the Great Desert? Because he can eat the sand which is there. But what brought the sandwiches there? Why, Noah sent Ham, and his descendants mustered and bred.” There are several separate puns, including the pun on “sand which” and “sandwich,” as well as “Ham” (a Biblical figure) and “ham” and the homophonic puns on “mustered”/“mustard” and “bred”/“bread.”

- Recursive pun: This type of pun requires understanding the first half of the joke to understand the second. For example, “A Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean your mother.” The term “Freudian slip” was coined by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud to refer to a mistake in speaking where one word is replaced with another. Freud proposed that these mistakes hinted at unconscious or repressed desires. He also had several theories about the relationship between children (especially boys) and their mothers. Therefore, this pun requires knowledge of Freud’s theories and recognition that the pun itself is a Freudian slip with the substitution of “your mother” for “another.”

Difference Between Pun and Joke

While they share much in common, puns and jokes are not synonymous. The definition of pun is such that it necessitates wordplay. A joke may contain this type of wordplay, but there are a great many jokes that do not have any plays on words. Also, some puns are not humorous and used for rhetorical, rather than humorous, effect.

Common Examples of Pun

There are thousands of common puns in English; many languages have their own puns as well. Puns are quite frequent in every day language. You may have heard or used the following ones in regular conversations:

- Denial is not just a river in Egypt.

- Make like a tree and leave.

- Put that down, it’s nacho cheese.

Some businesses have puns in their names. For example:

- Hairdressing salon: Curl Up and Dye

- Lawyers office: Dewey, Cheatum, and Howe

- Ophthalmologist: For Eyes

What Does “No Pun Intended” Mean?

The phrase “no pun intended” is quite common. People say this when they unintentionally say something that could be construed as a pun, but in fact they don’t mean to make light of the situation. Consider the following situations:

- A window breaks and someone cuts his finger. When telling his friend about this later, she says, “Wow, that sounds painful. No pun intended.” This is because “pain” is a homonym for “pane,” which could refer to the window pane. However, the friend did not mean to tease him about his cut.

- In a geometry lesson, a student notices an error that the teacher has made on the board. The teacher says, “Good point. No pun intended.” This could be construed as a pun because “point” is a mathematical term, but the teacher was just congratulating the student, not trying to make a pun.

- A band breaks up and when explaining why, the lead singer says, “We’d hit a low note. No pun intended.” The “low note” here acts as a cliche for something being bad, yet could be taken literally since the band makes music together. The singer makes clear, however, that she means “low note” in the figurative sense.

Significance of Pun in Literature

Some people consider puns to be quite foolish and worthy only of eye-rolls or groans. However, puns can require a good deal of knowledge on the part of the audience (especially in recursive puns, as explained above). If the puns are particularly clever they are rewarding for the reader or listener when they decipher the pun. Many famous authors used puns to great effect, perhaps none more so than William Shakespeare. Shakespeare used language with such dexterity that his puns often delight and surprise the reader.

Examples of Pun in Literature

Example #1

HAMLET

I will speak to this fellow.—Whose grave’s this, sirrah?

GRAVEDIGGER

Mine, sir.

HAMLET

I think it be thine, indeed, for thou liest in ’t.

GRAVEDIGGER

You lie out on ’t, sir, and therefore it is not yours. For my part, I do not lie in ’t, and yet it is mine.

HAMLET

Thou dost lie in ’t, to be in ’t and say it is thine. ‘Tis for the dead, not for the quick. Therefore thou liest.

GRAVEDIGGER

‘Tis a quick lie, sir. ‘Twill away gain from me to you.

(Hamlet by William Shakespeare)

William Shakespeare used hundreds of puns in his plays and sonnets. They indicate a cleverness of thought on the part of the speaker; Hamlet being perhaps the cleverest character in all of Shakespeare’s works, it is not surprise that he uses many throughout the play. Hamlet encounters a gravedigger in this pun example and the two of them have a witty back-and-forth using the two meanings of the word “lie.” They pun on the idea of the gravedigger resting horizontally in the grave versus the gravedigger fabricating the story of the grave being his own.

Example #2

CECILY: You must not laugh at me, darling, but it had always been a girlish dream of mine to love some one whose name was Ernest.

[ALGERNON rises, CECILY also.]

There is something in that name that seems to inspire absolute confidence. I pity any poor married woman whose husband is not called Ernest.

(The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde)

Oscar Wilde used many examples of puns in his works, though he was also once quoted as having said, “Puns are the lowest form of humor.” His entire play The Importance of Being Earnest hinges on a homophonic pun. “Earnest” functions both as a name and as a quality. The quote from Cecily perfectly sums up the dual meanings. Cecily says she wants to marry a man named “Ernest” because its homonym, “earnest,” inspires confidence. Cecily mistakenly believes that the character of Algernon is named “Ernest,” which is one of the primary reasons that she loves and wants to marry him.

Example #3

[Alice:] ‘You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis–‘

‘Talking of axes,’ said the Duchess, ‘chop off her head!’

(Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll)

Lewis Carroll was yet another author who was a fan of using puns in his work. In this example of pun, Alice is trying to impress the Duchess with her worldly knowledge. When she uses the word “axis,” though, the Duchess makes the homophonic connection to “axes” and calls for Alice’s execution.

Test Your Knowledge of Pun

1. Choose the correct pun definition from the following statements:

A. A very funny statement.

B. A joke which can only be understood when written, not heard.

C. A form of wordplay using similar sounding words.

| Answer to Question #1 | Show |

|---|---|

2. Consider the following pun:

One grasshopper told another about eating corn. It went in one ear and out the other.

Which type of pun is this?

A. Recursive

B. Homonymic

C. Compound

| Answer to Question #2 | Show |

|---|---|

3. Which of the following lines from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet contains a pun?

A.

ROMEO: Not I, believe me. You have dancing shoes

With nimble soles. I have a soul of lead

So stakes me to the ground I cannot move.

B.

ROMEO: But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

C.

JULIET: O Romeo, Romeo,

wherefore art thou Romeo?

Deny thy father and refuse thy name,

Or if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet.

| Answer to Question #3 | Show |

|---|---|

What do you call a sandwich made of wordplay? A pun-ini.

The English language abounds with pun examples in literature. From Chaucer to Shakespeare, from the Romantics to contemporary poetry, writers have twisted language to explore new (and often hilarious) possibilities with words.

We generally consider puns to have humorous intent. However, The pun in literature can also be quite serious. So, let’s examine how puns can complement your writing and open new doorways in your work. We’ll take a look at some pun examples in literature and tips for writing puns, as well as reasons to incorporate this literary device in your work.

But first, what is a pun? Let’s define this playful and serious art form. I hope I won’t be punished for every pun-I-shed. All puns intended!

Pun Definition: What is a Pun?

At its simplest definition, a pun is a play on words. By experimenting with the sounds and/or meanings of a word, the author of a pun uses language in a novel, surprising, and often humorous way.

Pun definition: A play on words. By experimenting with the sounds and/or meanings of a word, the author of a pun uses language in a novel, surprising, and often humorous way.

For example, let’s say you owned a talkative feline, and I told you your pet “is a little catty.” This would be a play on words, because I’m using catty to mean “gossipy” on top of the fact that your pet is a cat.

Another word for pun is “paronomasia,” a Greek word translated as “to call something by a slight change of name.” If two wanderers saw a really witty pun, then would a pair of nomads see a paronomasia?

There are three basic categories of puns: those that play with sound, those that play with meaning, and those that play with both. Let’s break each down:

Homophonic Pun Examples

Puns that play with sound use homophones to convey distorted meanings. Here are some common pun examples based on sound:

- Not using conditioner is a hair-brained idea. (Instead of hare-brained)

- Atheism is a non-prophet organization. —George Carlin (Instead of non-profit)

- The motorbike was two-tired to stand on its own. (Instead of too tired)

- The egotistical shrimp was a little shellfish. (Instead of selfish)

- “Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt.” —Mark Twain (Instead of The Nile)

Homographic Pun Examples

A homograph is a word that is spelled the same but has a different meaning. For example, a “tear” can be both water from the eye and a rip in fabric. Homographic puns play with the meanings of words, often using one word or phrase to mean two different things. See below:

- I asked the distraught particle physicist “what’s the matter?”

- This gum stick is in mint condition.

- The dying calendar’s days were numbered.

Compound Pun Examples

Lastly, a pun can use both homophones and homographs at the same time. In the below examples, the compound puns play with both the sounds and meanings of words:

- A short psychic broke out of jail. She was a small medium at large.

- She pulled a mussel at the seafood gymnastics event.

Pun Examples in Literature

While most modern day puns are thought of as “dad jokes,” the pun plays a serious part in classic and contemporary literature. Take a look at these pun examples in literature and you’ll see how authors have toyed with the English language throughout history.

Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare

In Romeo & Juliet, Mercutio—one of Romeo’s closest friends—is killed at the hands of Tybalt, turning the play from a comedy to a tragedy. As he dies, Mercutio says this:

“Ask for me tomorrow and you shall find me a grave man.”

Mercutio’s use of the word “grave” is a pun. To be a grave man means to be utterly serious, but Mercutio means this to say he will be dead—in the grave. Always the comic, Mercutio even uses his own death as joking material.

Richard III by William Shakespeare

In Act 1, Scene 1 of Richard III, Richard, the brother of Edward IV and soon-to-be king, comments on Edward’s banner:

“Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York.”

Here, “sun” is a pun. The banner itself depicts an image of the sun, but also refers to Richard being a member (or son) of the House of York. While the text itself denotes “sun,” audience members of this play will be quick to hear the pun. As in many of Shakespeare’s plays, his puns are better heard rather than read.

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Here’s an excerpt from Alice’s first encounter with the Mouse:

“‘Mine is a long and a sad tale!’ said the Mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing. ‘It is a long tail, certainly,’ said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse’s tail; ‘but why do you call it sad?’ And she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking.”

The conversation goes unexpectedly because each character hears a different spelling of the word “tail / tale.” This kind of humorous misunderstanding is also known as a mondegreen.

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Pip, the protagonist of Great Expectations, is a small and misunderstood orphan boy, and his remaining family and fellow townsfolk tend to think they know what’s best for him. At one point, Pip remarks this to the reader:

“They seemed to think the opportunity lost, if they failed to point the conversation to me, every now and then, and stick the point into me.”

The double usage of “point” is a pun meaning two different things: the point of the conversation points into Pip. In other words, every time the conversation turns on Pip, it seems to cut into him. This rather serious paronomasia evinces both Pip’s precocious mind and the unkind society he grows up under.

“[Of a girl, in white]” by Harryette Mullen

This poem by Harryette Mullen was originally accessed here, at Poetry Foundation.

Of a girl, in white, between the lines, in the spaces where nothing is written. Her starched petticoats, giving him the slip. Loose lips, a telltale spot, where she was kissed, and told. Who would believe her, lying still between the sheets. The pillow cases, the dirty laundry laundered. Pillow talk-show on a leather couch, slips in and out of dreams. Without permission, slips out the door. A name adores a Freudian slip.

The word “slip” here is used three times, each time under a slightly different and sometimes ambiguous meaning. The first usage of slip is a pun: the petticoat might be slipping off, and it also might be “giving him the slip” or getting away from him. This ambiguity makes for a surprising difference in interpretation, and such interpretability comes back around when the poet mentions a Freudian slip. This short prose poem masterfully forms a mirror to the reader, asking them to consider how they interpret ambiguous words, and why.

“Money is an Energy” by Justin Marks

Here’s an excerpt from “Money is an Energy” by Justin Marks, accessed from The Academy of American Poets:

Money is current

I would like to not live

paycheck to paycheck

You could make a pun on currency

but not quite

Rather self-referential, the pun meaning is clear: working paycheck to paycheck requires a constant state of currency—as in, constantly being up-to-date on your current bank balance and available funds. Ironically, “currency” also refers to money, which someone who lives paycheck-to-paycheck has little of.

The Bible

The Bible actually has quite a few puns, though many of those will be lost on the reader unless they are well-versed in ancient languages and customs. Here’s one of the Bible’s pun examples:

Micah 1:10: Declare ye it not at Gath, weep ye not at all: in the house of Aphrah roll thyself in the dust.

The name Aphrah, sometimes written as Beth-Le-Aphrah, means “house of dust.” So, the sentence here is “in the [house of dust], roll thyself in dust.”

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Another work which has a surprising amount of puns is Nabokov’s Lolita. Here’s one such example:

We had breakfast in the town of Soda, pop. 1001.

By abbreviating “population” to “pop.”, this sentence makes a play on words with “soda pop.”

What’s the point of writing puns?

You might be wondering what puns accomplish. They’re mostly humorous twists on language, but why do authors employ these devices in their work? What’s the point of writing puns?

Here are a few reasons why writers play with words:

- To Create Ambiguity. How should a certain word or phrase be interpreted? Sometimes, the vague interpretability of words contributes directly to the author’s meaning, though this ambiguity should be tactful and intentional.

- To Highlight a Word. When Shakespeare creates a pun using sun/son in Richard III, he isn’t just being cheeky—he’s highlighting the sense of entitlement and desire for power that drives Richard’s many actions.

- To Add Irony. Sometimes, a pun is used to add irony to the text. Ironic puns are often situational and based on other elements occurring in the text. However, an ironic pun can also be built off of a contranym—a word that has multiple and opposing definitions, such as the word “clip,” which can mean “to fasten” or to “detach.”

- To be Clever or Humorous. Finally, yes, many puns are used to make the writing clever, humorous, or interesting. By twisting language and its many possible meanings, the writer creates new avenues for the reader to engage with and respond to the writing itself.

Among poetic devices, puns can prove quite controversial. Some writers and theorists disparage the use of pun in literature, as the wordplay can often seem shallow or irrelevant to the text itself.

Certainly, you do not want to overload your writing with paronomasias, or else they will distract or baffle the reader. Additionally, most puns get lost in translation, because the device relies on a specific sound and/or meaning inherent to a certain word in a certain language.

Nonetheless, a pun here and there can add flare and texture to your writing, enhancing the reader’s experience with the text, creating new inroads for interpretation, and making your work more artful and stylish.

Tips for Writing Puns

The hare who wouldn’t stop playing with words was quite a punny rabbit.

As you can see, I love puns. Sure, they’re not the highest of art forms (though Alfred Hitchcock disagrees), but language is fun and interesting and ripe for experimentation. Here’s a few ideas for writing puns in your own work:

1. Play with Rhymes

Try taking a common phrase, changing one of the consonants in that phrase, and then writing about that phrase under the new meaning you’ve given it. For example, instead of the phrase “snug as a bug in a rug,” you might write “smug as a thug in a tug.” Then, give context: make a joke about a murderer getting away on a tugboat, or even write a story around that single pun.

It might seem a little easy to base a story around a pun, but there’s literary history here. Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest, for example, begins with a character named Jack Worthing, a dishonest gentleman. At the end of the play, he becomes trustworthy and also has changed his name to Earnest, so he has learned the importance of “being earnest,” both in the literal sense and the nominative sense.

(No, Oscar Wilde might not have written an entire play to make a single pun, but that doesn’t mean you can’t!)

2. Play with Homophones and Homographs

The English language is filled with homophones and homographs. Many of our words sound the same to each other, and one word can have hundreds of definitions. Experiment with this!

In one of the above pun examples in literature, we mentioned a pun that was also a mondegreen. Homographic and homophonic puns can also take the form of zeugmas, syllepses, paraprosdokians, or other literary devices. Choose a word, find a homophone or homograph, and go wild.

3. Use Free Association

Free association is a writing technique in which you let your mind wander freely about the page. By giving yourself a topic to write on and letting your pen loose, you can come up with connections, or “associations,” that you might not have found if you had written with tight control over your words.

So, pick a word, then let your mind loose. Maybe your mind is a hunter, rifling through a dictionary. Or it’s a pig going ham with language. Or it’s a beast going wild with wordplay.

4. Experiment with Grammar

English grammar, just like the English language in general, gets confusing. Use that to your advantage, and you might develop new and witty puns.

We saw this experimentation with grammar in Lolita. By playing with periods and commas, Nabokov played with the words “soda pop” by describing the town of “Soda, pop. 1001.” In your own writing, making use of grammar and punctuation can certainly produce novel, exciting possibilities in language.

5. Be Referential

Puns make for witty, interesting references, so long as you write them the right way. For example, most people are familiar with the novel War & Peace, which makes the monaker “Warren Peace” (for musician Geoffrey Alexander MacCormack) incredibly funny.

But, one of the trickiest aspects in writing puns is the use of references. For example, I might tell you that I “thoroughly enjoyed reading Civil Disobedience” but if you don’t know that that book was written by Thoreau (rhymes with thorough), you won’t see the joke. Or, if there’s a learning and confidence curve to writing puns, I might say it abides by the “Punning Krueger effect”—but you would need to know about the Dunning-Krueger effect first.

Punny references should be tactful and universal to your audience. But, when the pun lands right, it will thoroughly amuse and delight the reader.

Master the Pun at Writers.com

Okay, okay, I’ve got one more for you. If you spend your entire literary career exploring new lands in paronomasia, does that make you Juan Punce de Leon?

That was bad, I know. I’m quite the pun of a gun. So if you want to do better than me, take a look at our upcoming creative writing courses, where you’ll learn the craft of creative writing from one of our award winning instructors. Along the way, experiment with your puns and chart new terrain in the possibilities of language. We hope to write with you soon!

Puns are often used in texts for humour, but can also make you think differently about a subject if the meaning is changed in the text.

Pun definition

A pun is a play on words or a joke using homophones (words with the same pronunciation but different meanings) or homographs (words with the same spelling but different meanings), with the pun centering on a word with more than one meaning or on two words that sound alike. Let’s start to explore some quick examples of puns to get you more confident when trying to spot them.

Types of word puns

We will now take a look at three different types of puns. These are:

- Homophonic puns

- Homographic puns

- Compound puns

Homophonic puns

Homophonic puns rely on words that sound the same (or very similar) but have different meanings and spellings (these are called homophones).

Because homophones sound the same but are spelt differently, the humour from homophonic puns is used more often in spoken texts, as the pun is more effective when it is spoken rather than when it is read.

Yesterday, I bet the butcher that she couldn’t reach the meat on the top shelf. She refused to take my bet since the steaks were too high.

Homographic puns

Homographic puns (also known as heteronymic puns) use words that are spelt the same but have different meanings.

Unlike homophonic puns, homographic puns are better understood when read. Because of this, homographic puns can be found in prose writing as well as plays and humorous writing. They are also used to show the multiple meanings of something, rather than writers just using them for humour.

Time flies like an arrow, but fruit flies like a banana.

Here, the homographic pun plays on the word «flies» which is spelled the same but has multiple meanings. The first meaning is referring to flight but the second meaning is referring to a fly, which is an insect.

Compound puns

Compound puns are probably the easiest to understand — they are simply a sentence that contains more than one pun. This can be two homographic puns, two homophonic puns, or a mixture of both.

They sometimes end up having more than two meanings, as each pun has its own multiple meanings; when they are combined they have lots of meanings.

Don’t scam in the jungle; cheetahs are always spotted.

Now that we’ve had a look at some different types of puns let’s think about some common examples.

Pun examples

List of puns

Now that you have a good understanding of what a pun is and the different types of puns, let’s have a look at some examples of puns to help you get more confident identifying them in a text.

Here are some examples of homophonic puns:

No matter how much you push the envelope, it will still be stationary.

The word ‘stationary’ can refer to something not moving but can also be confused with stationery, which refers to writing or office materials.

Reading while sunbathing makes you well-red.

‘Well-red’ could be confused with ‘well read’ as they sound the same. So the sentence has the double meaning of someone being able to read a lot but also becoming sunburnt.

Here are some homographic puns! Remember, homographic puns are spelled out the same but still have multiple meanings.

Always trust a glue salesman, they tend to stick to their word.

‘Stick’ has a double meaning. It could be talking about a glue salesman always being true to their word, or saying that they literally stick to it, as they sell glue.

The tallest building in town is the library — it has thousands of stories.

The pun in this sentence plays on the word ‘stories’ which can mean floors in a building or the narrative of a text.

A boiled egg every morning is hard to beat.

The word ‘beat’ in this sentence could mean whisking the egg, or saying that there isn’t anything better than a boiled egg every morning.

Finally, take a look at this example of a compound pun:

A hundred hares have escaped, the police are combing the place.

This sentence uses a compound pun! The first word (hares) can refer to the animal or to the hair on your head. Combing (the second word) can mean searching or could be talking about using a comb. Here we have both a homophonic pun (‘hare’ and ‘hair’) as well as a homographic pun (‘combing’).

Puns in literature

Now that you’ve had a look at some puns, let’s consider why a writer might use puns and what effects they can have.

Puns are used quite often in Literature and are more common in plays than prose. We are going to look at two examples from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet , as well as a pun used in Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations .

Ask for me tomorrow, you shall find me a grave man (William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 1597)

Mercutio speaks this homographic pun before his death. The word ‘grave’ has multiple meanings. It could mean that Mercutio is sad / serious about the situation between Romeo and Tybalt (who are feuding), or it could be Shakespeare hinting at Mercutio’s imminent death.

Being but heavy I will bear the light. Give me a torch. I don’t want to dance. I feel sad, so let me be the one who carries the light (William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 1597)

The compound pun here shows how puns can give multiple meanings to a line. Heavy could mean sadness, but also might be referring to the light itself being heavy. The light also has a double meaning. It could be talking about literal light or ‘light’ feelings.

This pun helps us understand Romeo’s feelings in this part of the play, and is a great example of the way puns can help a writer to create double meanings rather than just using them for humor.

They failed to point the conversation to me, every now and then, and stick the point into me. (Charles Dickens, Great Expectations, 1867)

Here is an example of a homographic pun in prose writing (rather than a play). In Dickens’ novel, the point can mean two different things.

- Pointing something out (to do with the main aspect of a conversation);

- Be the literal definition of the point (the sharp end) of an object.

Now you have a much greater understanding of puns, their types, and their uses. You will soon have a chance to test your knowledge, so pay attention to these key takeaways …

Pun — Key takeaways

- Puns can be used to create humour in a text, but can also be used to give multiple meanings.

- Puns are a type of wordplay, using words that have more than one meaning to create humour and double meaning.

-

There are three common types of a pun: homophonic pun, homographic pun, and compound pun.

-

Puns can often be found in plays — and you may find lots of them when studying Shakespeare.

-

They can also be used in other types of literature, such as prose.

Pun definition: A pun is defined as a play on words devised in order to create humor for the intended audience.

Puns are plays on words devised for the purpose of creating humor for the audience. These plays on words may come from words that sound the same but have different spellings/meanings, or one word that itself has more than one meaning. Jokes that are in the form of puns may seem cheesy, but they are an artful, clever use of language.

Pun Examples

- Have you ever eaten a clock? It’s very time consuming

- Time consuming = pun

- In this example, the phrase “time consuming” is a pun. It holds two different meanings: eating is time consuming as well as a time consuming clock.

- Animal puns? Toucan play that game.

- Toucan = pun

- In this example, the word “toucan” has two meanings in the joke: toucan the animal as well as it sounding like the number phrase “two can.”

Modern Examples of Puns

Typically, the common examples of puns found today are through witty remarks made by people:

- Did you hear about the guy whose whole left side got cut off? He’s all right now.

- All right = pun

- I used to be a banker, but I lost interest.

- Interest = pun

Puns vs. Jokes

Because puns are so often used to create humor, people may tend to think that they are synonymous with jokes.

While these two are similar, they are not the same device. In contrast to jokes, which are always intended to create humor, puns at times may be a type of joke or they may be used as a rhetorical device.

The Function of Puns in Literature

In literature, puns are used to create humor in the scene through their lighthearted, witty nature. While puns at times may seem silly or cheesy, they are an artful way to use words and often receive positive reactions from the audience if they are aware of the multiple meanings of the words used in the text.

Examples of Puns in Literature

One of the most famous artists of puns was the playwright William Shakespeare.

In his tragedy Romeo and Juliet, he used puns in scenes that allowed for comic relief in an otherwise serious play. Romeo’s friend Mercutio uses several puns throughout the play showing his witty personality.

After being stabbed by Tybalt, Mercutio exclaims, “ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man”. In this line, the word “grave” holds two meanings creating a pun:

- Grave = serious

- Grave = dead

In Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest, the title itself is a pun. The word earnest is in reference to dictionary definition of the word as well as the name Ernest. By including a pun in the title, it foreshadows the clever and witty aspects of the play.

Summary: What Are Puns?

Define pun in literature: In summation, puns are plays on words typically used to create a humorous effect on the audience.

Final Example:

In Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare, Mercutio and Romeo are having a heated debate in regards to the importance of dreams. During this debate the two exchange several puns. Mercutio declares that “dreamers often lie,” and Romeo creates a pun on the word “lie” with his response, “in bed asleep…while they do dream things that are true.” By including puns in this argument, it relieves some of the tension in addition to showing the cleverness of the two.

Contents

- 1 What is a Pun?

- 2 Pun Examples

- 3 Modern Examples of Puns

- 4 Puns vs. Jokes

- 5 Examples of Puns in Literature

- 6 Summary: What Are Puns?

Puns are a figure of speech that has many uses both in everyday conversation as well as in writing. Puns can be used to achieve a humorous effect in a piece of writing. A pun is known as “paronomasia,” and has its roots in the Greek word “paronomazein,” which means to make a change in a name. Some of the synonyms of puns include wordplay, witticism, double meaning, innuendo, quip, double entendre, and quibble. Today let’s have a look at what puns are, their function, common examples, etc.

- What is a Pun?

- Pun Examples

- Types of Puns

- Tips for making a Pun

- Purpose of Puns

- Pun Vs Joke

- Intended and Unintended Puns

- FAQs on Puns

What is a Pun?

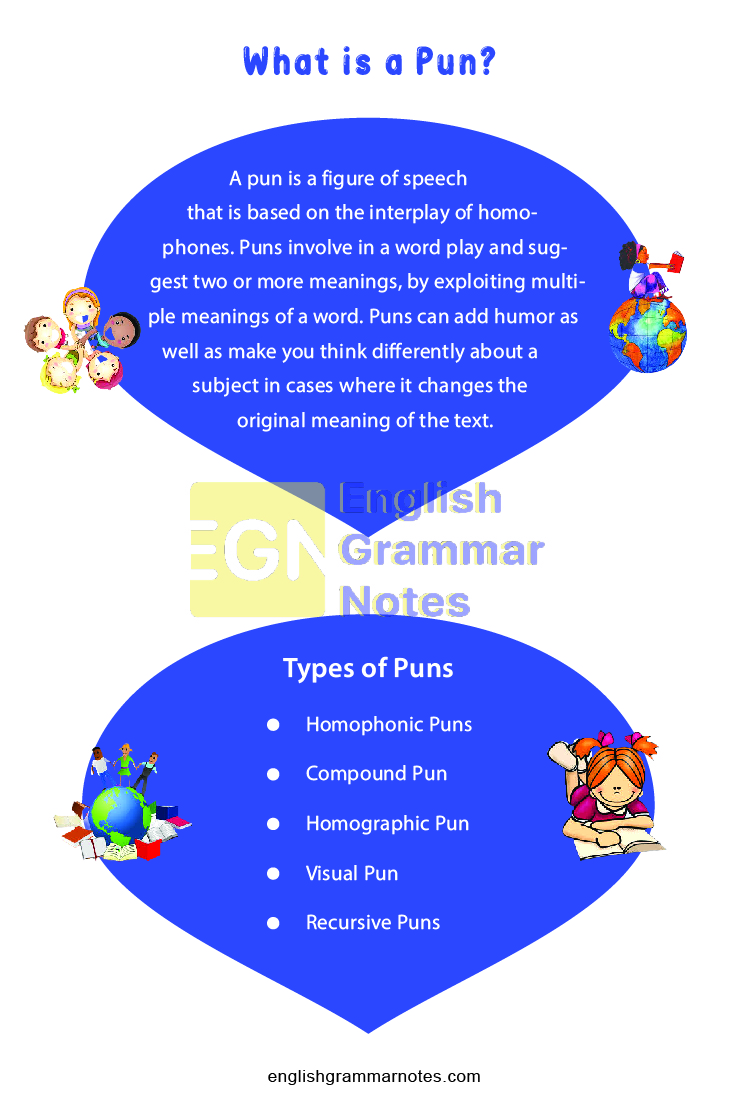

A pun is a figure of speech that is based on the interplay of homophones. Puns involve in a word play and suggest two or more meanings, by exploiting multiple meanings of a word. Puns can add humor as well as make you think differently about a subject in cases where it changes the original meaning of the text. The humor comes from the confusion between the two meanings.

Pun Examples

Given below are some of the commonly seen puns in everyday expression:

- The cat is near the computer and has its eye on the mouse.

- It’s not simple to love musicians as they are very upbeat.

- If you are by the window, I’ll help you out.

- The population of Ireland is always Dublin.

- It’s very though for crabs to share as they are shellfish.

- Give me the newspaper so we don’t have crosswords.

- The skeleton model in our biology class is a bonehead.

- The wedding cake had me in tiers.

- When my algebra teacher retired, he wasn’t ready to face the aftermath.

- Some bunny loves you.

- As I have graph paper, it’s time to plot something.

- Make like a tree and leave.

- This candy cane is in mint condition.

- My librarian is a great bookkeeper.

- This vacuum sucks.

- I like archery, but it’s very difficult to see the point.

See More:

- Oxymoron

- Litotes

- Metaphor

Types of Puns

Puns can be classified into different types based on their effect. Given below are five different types of puns:

- Homophonic Puns: This pun makes use of paired homonyms that are words that sound the same but have different meanings.

- Compound Pun: Compound pun consists of more than one pun in the same sentence.

- Homographic Pun: also known as a heteronymic pun. These puns play on words that have the same spelling but have a double meaning.

- Visual Pun: Visual puns can be achieved through imagery, graphics, or logos.

- Recursive Puns: This pun is a two-part pun. You have to recognize or understand the first part of the pun to grasp the meaning of the second part.

Tips for making a Pun

Given below are some tips that can help you create a good pun:

- Have an idea of the different types of puns.

- Be clear with the confusing grammatical rules.

- Link words or phrases with similar meaning

- Build your vocabulary which would in turn help you to make connections between words and create puns.

- The use of a rhyming dictionary can help you discover words for puns.

Purpose of Puns

Puns are often employed for the following reasons:

- The main function of a pun is to invoke laughter in the readers.

- Adds humour to what you write or say

- Puns can also change the meaning of an idea or phrase.

Pun Vs Joke

People often use the terms puns and joke interchangeably. However, both these techniques are different from each other. Puns are figures of speech that engage in a kind of wordplay, whereas jokes are narrative structures that are used to create humor and laughter.

Intended and Unintended Puns

Authors and characters make use of words in some contexts which can have several meanings but the readers mostly deduce the meanings which the pun does not originally mean. This is known as unintended use puns or it is called a pun unintended. However, at other times, puns may be used intentionally to create laughter in the readers. Such use of puns is known as intended puns.

Explore more literary devices and get a command over your language and become a pro in writing.

FAQs on Puns

1) What are puns?

A pun is a figure of speech that is based on the interplay of homophones. Puns involve in a word play and suggest two or more meanings, by exploiting multiple meanings of a word.

2. Give examples of puns?

Some common examples of puns include: Make like a tree and leave, This candy cane is in mint condition, My librarian is a great bookkeeper, This vacuum sucks.

3. What are the different types of puns?

The five different types of puns include homophonic puns, compound puns, visual puns, recursive puns, and homographic puns.

4. What are the benefits of using a pun?

The use of puns can invoke laughter in the readers. Puns can also change the meaning of an idea or phrase.

Conclusion

Puns are not just figures of speech employed to make the readers laugh, they can often make readers pause and consider what they have read from a different angle. This would in turn help them to appreciate your talent and grasp your language. Puns have been used for a long time to entertain readers and make reading more interesting.