«You» and «Your» are not to be confused with U, Ewe, Yew, or Ure.

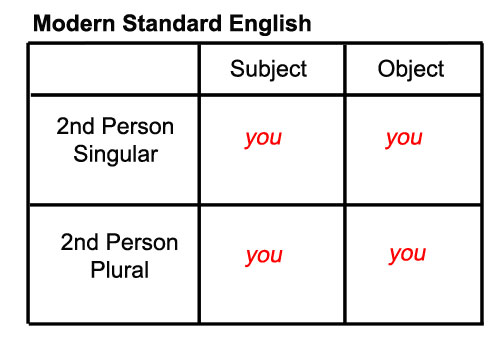

In Modern English, you is the second-person pronoun. It is grammatically plural, and was historically used only for the dative case, but in most[citation needed] modern dialects is used for all cases and numbers.

History

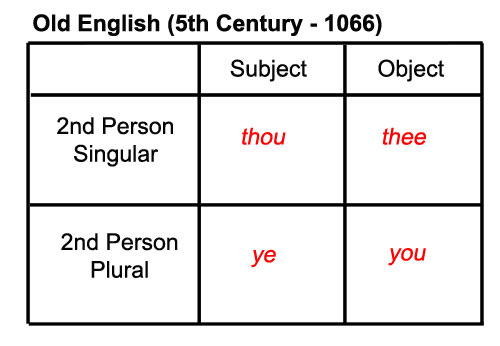

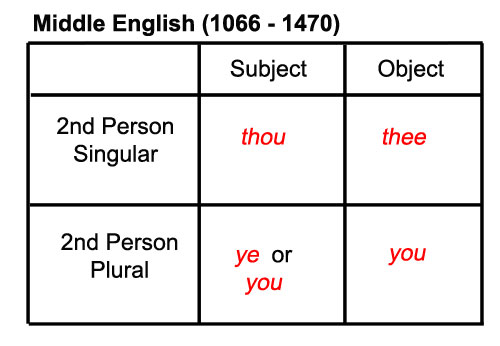

You comes from the Proto-Germanic demonstrative base *juz-, *iwwiz from Proto-Indo-European *yu— (second-person plural pronoun).[1] Old English had singular, dual, and plural second-person pronouns. The dual form was lost by the twelfth century,[2]: 117 and the singular form was lost by the early 1600s.[3] The development is shown in the following table.[2]: 117, 120, 121

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | ME | Mod | OE | ME | Mod | OE | ME | Mod | |

| Nominative | þu | þu | ġit | ġe | ȝē | you | |||

| Accusative | þe | þē | inc | ēow | ȝou | ||||

| Dative | |||||||||

| Genitive | þīn | þī(n) | incer | ēower | ȝour(es) | your(s) |

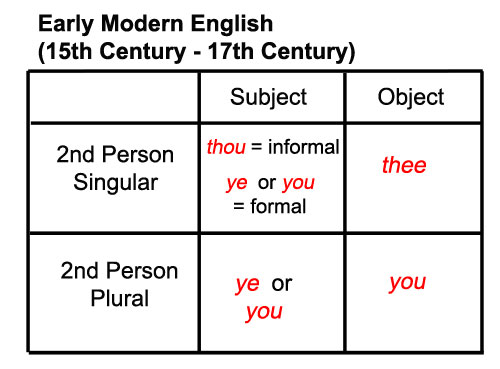

Early Modern English distinguished between the plural ye and the singular thou. As in many other European languages, English at the time had a T–V distinction, which made the plural forms more respectful and deferential; they were used to address strangers and social superiors.[3] This distinction ultimately led to familiar thou becoming obsolete in modern English, although it persists in some English dialects.

Yourself had developed by the early 14th century, with the plural yourselves attested from 1520.[4]

Morphology

In Standard Modern English, you has five shapes representing six distinct word forms:[5]

- you: the nominative (subjective) and accusative (objective or oblique case[6]: 146 ) forms

- your: the dependent genitive (possessive) form

- yours: independent genitive (possessive) form

- yourselves: the plural reflexive form

- yourself: the singular reflexive form

Plural forms from other varieties

Although there is some dialectal retention of the original plural ye and the original singular thou, most English-speaking groups have lost the original forms. Because of the loss of the original singular-plural distinction, many English dialects belonging to this group have innovated new plural forms of the second person pronoun. Examples of such pronouns sometimes seen and heard include:

- y’all, or you all – southern United States,[7] African-American Vernacular English, the Abaco Islands,[8] St. Helena[8] and Tristan da Cunha.[8] Y’all however, is also occasionally used for the second-person singular in the North American varieties.

- you guys [ju gajz~juɣajz] – United States,[9] particularly in the Midwest, Northeast, South Florida and West Coast; Canada, Australia. Gendered usage varies; for mixed groups, «you guys» is nearly always used. For groups consisting of only women, forms like «you girls» or «you gals» might appear instead, though «you guys» is sometimes used for a group of only women as well.

- you lot – United Kingdom,[10] Palmerston Island,[11] Australia

- you mob – Australia[12]

- you-all, all-you – Caribbean English,[13] Saba[11]

- a(ll)-yo-dis – Guyana[13]

- allyuh – Trinidad and Tobago[14]

- among(st)-you – Carriacou, Grenada, Guyana,[13] Utila[11]

- wunna – Barbados[13]

- yinna – Bahamas[13]

- unu/oona – Jamaica, Belize, Cayman Islands, Barbados,[13] San Salvador Island[8]

- yous(e) – Ireland,[15] Tyneside,[16] Merseyside,[17] Central Scotland,[18] Australia,[19] Falkland Islands,[8] New Zealand,[11] Philadelphia,[20] parts of the Midwestern US,[21] Cape Breton and rural Canada[citation needed]

- yous(e) guys – in the United States, particularly in New York City region, Philadelphia, Northeastern Pennsylvania, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan;[citation needed]

- you-uns, or yinz – Western Pennsylvania, the Ozarks, the Appalachians[22]

- ye, yee, yees, yiz – Ireland,[23] Tyneside,[24] Newfoundland and Labrador[11]

Semantics

You prototypically refers to the addressee along with zero or more other persons, excluding the speaker. You is also used to refer to personified things (e.g., why won’t you start? addressed to a car).[25] You is always definite even when it is not specific.

Semantically, you is both singular and plural, though syntactically it is always plural: it always takes a verb form that originally marked the word as plural, (i.e. you are, in common with we are and they are).

Third person usage

You is used to refer to an indeterminate person, as a more common alternative to the very formal indefinite pronoun one.[26] Though this may be semantically third person, for agreement purposes, you is always second person.

- Example: «One should drink water frequently» or «You should drink water frequently».

Syntax

Agreement

You always triggers plural verb agreement, even when it is semantically singular.

Functions

You can appear as a subject, object, determiner or predicative complement.[5] The reflexive form also appears as an adjunct. You occasionally appears as a modifier in a noun phrase.

- Subject: You’re there; your being there; you paid for yourself to be there.

- Object: I saw you; I introduced her to you; You saw yourself.

- Predicative complement: The only person there was you.

- Dependent determiner: I met your friend.

- Independent determiner: This is yours.

- Adjunct: You did it yourself.

- Modifier: (no known examples)

Dependents

Pronouns rarely take dependents, but it is possible for you to have many of the same kind of dependents as other noun phrases.

- Relative clause modifier: you who believe

- Determiner: the real you; *the you

- Adjective phrase modifier: the real you; *real you

- Adverb phrase external modifier: Not even you

Pronunciation

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the following pronunciations are used:

| Form | Plain | Unstressed | Recording |

|---|---|---|---|

| you | (UK) /juː/

(US) /jə/ |

/ju/

/jə/ |

female speaker with US accent |

| your | (UK) /jɔː/

(US) /jɔr/ |

/jʊə/

/jʊ(ə)r/ |

female speaker with US accent |

| yours | (UK) /jɔːz/

(US) /jɔrz/ |

/jʊəz/

/jʊ(ə)rz/ |

female speaker with US accent |

| yourselves | (UK) /jɔːˈsɛlvz/, /jʊəˈsɛlvz/

(US) /jɔrˈsɛlvz/, /jʊrˈsɛlvz/ |

/jəˈsɛlvz/

/jərˈsɛlvz/ |

|

| yourself | (UK) /jɔːˈsɛlf/, /jʊəˈsɛlf/

(US) /jɔrˈsɛlf/, /jʊrˈsɛlf/ |

/jəˈsɛlf/

/jərˈsɛlf/ |

female speaker with US accent |

See also

- Generic you

- English personal pronouns

- Thou

- Y’all

- Yinz

References

- ^ «Origin and meaning of it». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ a b Blake, Norman, ed. (1992). The Cambridge history of the English Language: Volume II 1066–1476. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b «thee». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ «yourselves». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ a b Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge history of the English Language: Volume III 1476–1776. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Rios, Delia M (2004-06-01). «‘You-guys’: It riles Miss Manners and other purists, but for most it adds color to language landscape». The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- ^ a b c d e Schreier, Daniel; Trudgill, Peter; Schneider, Edgar W.; Williams, Jeffrey P., eds. (2013). The Lesser-Known Varieties of English: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139487412.

- ^ Jochnowitz, George (1984). «Another View of You Guys». American Speech. 58 (1): 68–70. doi:10.2307/454759. JSTOR 454759.

- ^ Finegan, Edward (2011). Language: Its Structure and Use. Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc p. 489. ISBN 978-0495900412

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Jeffrey P.; Schneider, Edgar W.; Trudgill, Peter; Schreier, Daniel, eds. (2015). Further Studies in the Lesser-Known Varieties of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02120-4.

- ^ «Expressions». The Aussie English Podcast. Archived from the original on Aug 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Allsopp, Richard (2003) [1996]. Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press. ISBN 978-976-640-145-0.

- ^ «Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago». Chateau Guillaumme Bed and Breakfast.

- ^ Dolan, T. P. (2006). A Dictionary of Hiberno-English. Gill & Macmillan. p. 26. ISBN 978-0717140398

- ^ Wales, Katie (1996). Personal Pronouns in Present-Day English. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0521471022

- ^ Kortmann, Bernd; Upton, Clive (2008). Varieties of English: The British Isles. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 378. ISBN 978-3110196351

- ^ Taavitsainen, Irma; Jucker, Andreas H. (2003). Diachronic Perspectives on Address Term Systems. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 351. ISBN 978-9027253484

- ^ Butler, Susan (Aug 30, 2013). «Pluralising ‘you’ to ‘youse’«. www.macquariedictionary.com.au. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ My sweet | Philadelphia Inquirer | 02/03/2008 Archived April 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McClelland, Edward (Feb 6, 2017). «Here’s hoping all youse enjoy this». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- ^ Rehder, John B. (2004). Appalachian folkways. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7879-4. OCLC 52886851.

- ^ Howe, Stephen (1996). The Personal Pronouns in the Germanic Languages: A Study of Personal Morphology and Change in the Germanic Languages from the First Records to the Present Day. p. 174. Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3110146363

- ^ Graddol, David et al. (1996). English History, Diversity and Change. Routledge. p. 244. ISBN 978-0415131186

- ^ «you, pron., adj., and n.» Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (2016). Garner’s Modern English Usage. Oxford University Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-19-049148-2.

Native speakers are pronoun experts. We (we is a pronoun here referring to native speakers including yours truly) understand them (them is a pronoun referring to pronouns) easily and employ them (there it is again; it is another pronoun, here referring to the word them) without much need for examination. (A reminder: a pronoun is a word used instead of a noun or noun phrase that has either already been mentioned or does not need to be named specifically.)

But you (another one!) maybe knew that already.

Pronoun use is in fact proof of our facility with the language—we so often get them right, and they’re not simple things. No one says «Us so often get them right,» or «We so seldom get they wrong.» But in a particular type of environment, pronoun use can wander from its predicted territory, as writer and humorist James Thurber noted:

I have been planning a piece on personal pronouns and the death of the accusative. Nobody says «I gave it to they,» but «me» is almost dead, and I have heard its dying screams from Bermuda to Columbus: «He gave it to Janey and I.» … My cousin Earl Fisher said it to me in Columbus, «Louise and I gave it to he and she last Christmas.»

— letter, 25 June 1956

Thurber has a point, and more than half a century later we’re still seeing the same kind of thing that bothered him so much. Let’s take a closer look at Thurber’s objections. In both of the examples he gives, the questionable pronouns are members of a compound phrase—that is, a phrase that has more than one distinct part. In the first it’s Janey and I:

He gave it to Janey and I.

What’s wrong with this sentence? It might look perfectly fine at first, but if we simplify the compound phrase an odd pronoun choice becomes apparent:

He gave it to Janey. He gave it to I.

The first part works, but «He gave it to I» isn’t idiomatic English. After a preposition like to we expect the accusative pronoun me, rather than the nominative pronoun I: «He gave it to me.» The same is true after other prepositions as well:

They were with me.

It isn’t for me.

It’s not about me.

When we rewrite these with compound phrases we get the following:

He gave it to Janey and me.

They were with Janey and me.

It isn’t for Janey and me.

It’s not about me and Janey.

Note that there’s nothing ungrammatical about putting me first, as in the last example; it’s simply considered more polite to put oneself in the final position.

Thurber’s second example is:

Louise and I gave it to he and she last Christmas.

«Louise and I» is fine, as we see if we separate the first compound phrase:

Louise gave it …; I gave it…

But if we separate the second compound phrase, the pronouns become unidiomatic:

We gave it to he last Christmas. We gave it to she last Christmas.

It’s the accusative—him and her in this case—that’s called for:

We gave it to him last Christmas. We gave it to her last Christmas.

The accusative is also called for when the pronoun is the object of the verb—that is, when it receives the action of the verb, such as her in «I saw her.» Again, things get complicated when the pronoun is part of a compound phrase, as in this reworked version of Thurber’s second example:

We gave he and she the book last Christmas.

When we separate the compound phrase, a similar situation arises:

We gave he the book last Christmas. We gave she the book last Christmas.

«We gave he the book» and «we gave she the book» don’t sound right; the accusative once again comes to the rescue:

We gave him the book last Christmas. We gave her the book last Christmas.

We won’t agree with Thurber that the accusative is dead—phrases like «tell me» and «call him» and «show her» and «hear them» continue to be used with unfettered frequency—but we do agree that compound phrases sometimes make people choose pronouns differently. If you want to keep the Thurber crowd happy, separate the compounds to see which pronoun is the word you’re looking for. In speech it may not matter to your audience much of the time, but in writing especially, you’ll be judged more favorably if you keep the accusative in its place.

But there’s more, of course, to this discussion. If pronoun use is proof of facility with the language, why do so many competent users of English confuse them in compound phrases?

One common theory is that people choose I instead of me in cases like «He gave it to Janey and I» because they’ve been taught that me isn’t correct in cases like «It is me» and «My friend and me agree»; they assume, so the theory goes, that there’s something wrong with me, especially when joined to someone else by and, and so they use I instead. It’s a reasonable enough theory—and maybe it holds true for some people—but it doesn’t explain the matter entirely because our evidence of [someone] and I in the object position goes back to the 16th century, about 150 years before anyone was instructing anyone else about these things.

Another theory has the added bonus of dealing also with the likes of «Louise gave it to he and she.» It’s from linguist Noam Chomsky, who, in his 1986 book Barriers, proposes that compound phrases like you and I and he and she are barriers to the assignment of grammatical case, meaning that their elements don’t get assigned case individually, but that the phrase as a whole is what gets assigned case instead; the individual words in the phrase can look like they’re in the object or subject position, or are even reflexive, i.e. myself, herself, or themselves. Chomsky’s idea remains a theory, but it does do the job of explaining the phenomenon.

Личные местоимения в английском языке указывают на лицо или предмет, к ним относят местоимения I, you, he, she, it, we, they. Личные местоимения — это первые слова, с которых начинают изучать английский язык.

Таблица личных местоимений английского языка: он, она, оно, они и др. по-английски

Все личные местоимения представлены в этой таблице:

| Единственное число | Множественное число | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 лицо | I — я | We — мы |

| 2 лицо | You — ты | You — вы |

| 3 лицо | He, she, it — он, она, оно | They — они |

Как правило, личные местоимения учат не отдельно, а сразу с соответствующей формой глагола to be и каким-нибудь существительным, прилагательным. Во-первых, так они лучше запоминаются, во-вторых, убиваете двух зайцев — учите и местоимения, и формы to be.

Примеры предложений:

I am calm. — Я спокоен.

You are tired. — Ты устал Вы устали.

He is polite. — Он вежлив.

She is kind. — Она добрая.

It is tall. — Оно высокое (о здании).

We are alone. — Мы одни.

They are happy. — Они счастливы.

Особенности некоторых личных местоимений

У английских личных местоимений есть несколько особенностей.

1. «Ты» и «вы» в английском языке

В русском языке можно обратиться на «ты» и на «вы», в английском только одно местоимение you. Раньше в английском языке тоже были «ты» и «вы», местоимение thou служило для обращения на «ты», а you — на «вы». Но со временем you полностью вытеснило thou в связи с повсеместным обращением на «вы». Есть такая известная шутка: англичанин даже к своей собаке обращается на «вы», то есть на «you».

Для нас эта особенность с «ты» и «вы» в английском языке только кстати: не нужно лишний раз думать к кому как обращаться. Разве что только если вы не обращаетесь к Богу — в религиозных текстах и обрядах устаревшее местоимение thou использутеся при обращении к Богу.

2. Почему местоимение I (я) в английском всегда пишется с большой буквы?

Англичане пишут «я» (I) только с большой буквы. Дело вовсе не в каком-нибудь высокомерии, причина куда проще. Староанглийское «я» выглядело так: «ic» или «ich», со временем язык изменился, изменилась орфография, в Средние века «ic» превратилось в «i». Проблема была в том, что «i» на письме часто сливалась с другими знаками, в особенности с римской единицей, поэтому нормой стало писать «i» как прописную «I».

3. Местоимение it — это не только «оно»

Местоимение it в английском языке указывает на неодушевленные предметы, а также на животных и младенцев. Для нас это непривычно, но по-английски, говоря о младенце, могут использовать it, а не he или she. То же самое касается животных. Впрочем, домашних любимцев, которые уже как члены семьи часто «очеловечивают», называя he или she.

4. Местоимение it как формальное подлежащее

Местоимение it часто используется как формальное подлежащее в безличных предложениях. Безличные предложения отличаются тем, что в них нет «действующего лица», то есть кого-то или чего-то, что играет роль подлежащего в предложении. Но по правилам английской грамматики, в безличных предложениях подлежащее присутствует, хоть и формально — его роль выполняет местоимение it. Обычно это предложения, где сообщается о каком-то состоянии, погоде, настроениии, говорится о времени.

It is cold. — Холодно.

It is sad. — Грустно.

It is five o’clock. — Сейчас пять часов.

Личные местоимения в объектном падеже

В английском языке личные местоимения могут использоваться как дополнения (объект действия). В этом случае они принимают форму объектного падежа. Кстати, в русском языке личные местоимения тоже меняют форму, когда используются в качестве дополнения: я — меня, ты — тебя, вы — вас и т. д.

Объектные местоимения приведены в этой таблице:

| Единственное число | Множественное число | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 лицо | I — Me | We — Us |

| 2 лицо | You — You | You — You |

| 3 лицо | He, she, it — Him, Her, It | They — Them |

Примеры:

Did you see me? — Вы меня видели?

I heard you. — Я вастебя слышал.

We can ask himher. — Мы можем спросить у негонее.

Don’t touch it! — Не трогай это!

You don’t know us. — Вы нас не знаете.

Find them. — Найдите их.

Личные местоимения: частые ошибки

Личные местоимения никогда не употребляются в качестве дополнения.

- Правильно: Did you see me? — Ты меня видел?

- Неправильно: Did you see I? — Ты меня видел?

И наоборот, объектные местоимения не употреблятся в качестве подлежащего.

- Правильно: I did’t see you. — Я тебя не видел.

- Неправильно: Me did’t see you. — Я тебя не видел.

Здравствуйте! Меня зовут Сергей Ним, я автор этого сайта, а также книг, курсов, видеоуроков по английскому языку.

Подпишитесь на мой Телеграм-канал, чтобы узнавать о новых видео, материалах по английскому языку.

У меня также есть канал на YouTube, где я регулярно публикую свои видео.

Let’s look at the fascinating history of the pronoun you!

I got the idea to write this lesson after some friends and I were talking about the pronoun whom and how it seems that fewer and fewer people know what it’s for and how to use it.

Might whom slip away the same way that thee and thou have? How were thee and thou used, and what happened to them?

Let’s start with how we use the word you today.

We use you for both subjects and objects.

You are great. You = Subject

The magician tricked you. you = Object

We use it as a singular pronoun and a plural pronoun.

But, you wasn’t always this versatile!

In Old English, which is the earliest form of the English language, you was only a second person plural object pronoun. It wasn’t used as a subject.

As time went on, you was used interchangeably with ye for a second person plural pronoun.

Then, the French influence on English affected how the pronoun you was used.

In French, you addressed kings and aristocrats (singular people) with plural pronouns.

English picked up on this and started using you and ye as formal pronouns to address aristocrats.

That slowly changed to people also using you and ye to address strangers and those with higher social status. Using the plural pronoun for one person was seen to be more polite.

And then, around the 17th century, we dropped thee, thou and ye, and used simply you for all of those words.

And that brings us back to where we are today!

There you have it! Language changes over time. I wonder what will happen to whom over the next hundred years. (Psst… If you’d like to know how to use whom you can read this lesson on who vs. whom.)

If you’d like to karate chop your way through grammar, you need to check out our Get Smart Grammar Program!

It’ll save you time and heartache, and it will bring you well-earned confidence.

Местоимение – это часть речи, которая употребляется вместо имени существительного или имени прилагательного. Местоимение указывает на лицо, предметы, их признаки, количество, но не называет их.

Личные местоимения означают лицо или предмет и употребляются вместо имени существительного. Они имеют формы именительного и объектного падежей. I tried the door. It was locked. — Я попытался открыть дверь. Она была заперта.

Притяжательные местоимения выражают принадлежность и отвечают на вопрос whose — чей, чья, чьё? Они имеют две формы: основную и абсолютную.

Притяжательные местоимения основной формы употребляются с существительным, являясь определением к нему: The doctor usually comes to his office at two o’clock. — Доктор обычно приходит в свой офис в два часа. Часто эти местоимения используются вместо артикля и в таких случаях не переводятся на русский язык: He took off his jacket and loosened his tie. — Он снял пиджак и ослабил галстук.

Местоимения абсолютной формы употребляются без существительного и выполняют функцию подлежащего, дополнения и именной части сказуемого: Theirs is a very large family. — Их семья очень большая. They are not my books; they must be yours. — Это не мои книги. Должно быть они ваши.

|

Число |

Лицо |

Личные местоимения |

Притяжательные местоимения |

Возвратно-усилительные местоимения |

||

|

Именительный падеж |

Объектный падеж |

Основная форма (перед существительным) |

Абсолютная форма (без существительного) |

|||

|

Ед. ч. |

1-е |

I я |

me меня, мне |

my мой |

mine |

myself |

|

2-е |

you ты, вы |

you тебя, тебе |

your твой, ваш |

yours |

yourself |

|

|

3-е (м. р.) |

he он |

him его, ему |

his его |

his |

himself |

|

|

3-е (ж. р.) |

she она |

her ее, ей |

her ее |

hers |

herself |

|

|

3-е (неодуш.) |

it оно, он, она |

it его, ему, ее, ей |

its его, ее |

its |

itself |

|

|

Мн. ч. |

1-е |

we мы |

us нас, нам |

our наш |

ours |

ourselves |

|

2-е |

you вы |

you вас, вам |

your ваш |

yours |

yourselves |

|

|

3-е |

they они |

them их, им |

their их |

theirs |

themselves |

Взаимные местоимения each other и one another выражают взаимосвязь между двумя и более лицами или предметами. Если они употребляются с предлогом, он ставится непосредственно перед ними: The men are playing chess with one another — Мужчины играют в шахматы друг с другом. My husband and I always sing for each other — Мой муж и я часто поем друг для друга.

Указательные местоимения выделяют предмет или лицо среди аналогичных.

Местоимения this (ед. ч.) и these (мн. ч.) указывают на предметы, которые расположены в относительной близости от субъекта речи; а that (ед. ч.) и those (мн. ч.) указывают на предметы, которые несколько удалены от говорящего.

Take this plum. It looks very ripe. – Возьми эту сливу. Она выглядит очень спелой. (Речь идет о сливе, которую говорящий видит прямо перед собой или держит в руке)

That house is very beautiful. – Тот (этот) дом очень красивый. (Речь идет о доме, находящемся на некотором расстоянии от говорящего)

Что касается времени, this и these употребляются если речь идет о настоящем моменте, а that и those – о прошлом или будущем. Louie, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. – Луи, я думаю, что это начало прекрасной дружбы.

I remember that he woke up early that morning. – Я помню, что он проснулся тем утром рано.

Чтобы не пришлось дважды повторять одно и то же существительное, после указательных местоимений this и that используется местоимение one. That coat does not suit me, I want this one. — То пальто мне не подходит, я хочу это.

Местоимение such (такой) относится к определяемому им имени существительному. После него ставится неопределенный артикль a(an), если существительное, перед которым оно стоит исчисляемое. There are such interesting people here! – Здесь есть такие интересные люди!

Перед местоимением same (такой же) всегда ставится определенный артикль the. I do not want the same TV set — Я не хочу такой же телевизор.

Вопросительные местоимения who, whom, what, which, whose, how необходимы для построения специальных вопросов. Они ставятся в начале вопросительного предложения вместо неизвестных спрашивающему лицу предметов, веществ, явлений, признаков.

Who is present today? – Кто сегодня присутствует?

What is on my table? – Что на моем столе?

Whose cup of tea is this? – Чья это чашка чая?

Which of you speaks English? – Кто из вас (который) говорит по-английски?

Относительные и соединительные местоимения who, whom, which, that, whose – это местоимения, служащие для образования сложноподчиненных предложений. Местоимения who, what, whose, which также являются соединительными.

Here is the photo of our cat which went missing several weeks ago. – Вот фотография нашего кота, который пропал несколько недель назад.

The man whom you saw last week was my teacher. – Человек, которого ты видел на прошлой неделе, мой учитель.

The girl whose you are looking for has just gone out. – Девушка, которую ты ищешь, только что ушла.

Неопределенные местоимения указывают на неизвестные предметы, признаки, количество.

|

производные неопределенных местоимений |

употребление |

|||

|

-thing |

-body |

-one |

||

|

неопределенное местоимение |

something [ˈsʌmθiŋ] что-то, что-нибудь |

somebody [ˈsʌmbɒdi], someone [ˈsʌmwʌn] кто-то, кто-нибудь |

1. В утвердительных предложениях. Тhere are some letters on the shelf. – На полке несколько писем |

|

|

неопределенное местоимение |

anything [ˈeniθiŋ] что-нибудь |

anybody [ˈeniˌbɒdi], anyone [ˈeniwʌn] кто-нибудь |

1. В вопросительных предложениях. Have you got any writing paper? – У вас есть какая-нибудь бумага для записей? |

|

|

все, что угодно |

всякий, любой |

3. В утвердительных предложениях. I found a taxi without any trouble. – Я нашла такси без (каких-либо) проблем. |

||

|

ничто |

никто |

4. В отрицательных предложениях (при отрицательной форме глагола). There is not any chalk in this box. – В этой коробке нет (совсем) мела. |

||

|

неопределенное местоимение |

1. В предложениях, которые соответствуют русским неопределенно-личным предложениям для обозначения неопределенного лица. One must always be in time for classes. – На занятия нужно приходить вовремя. |

|||

К отрицательным местоимениям в английском языке относятся следующие местоимения:

no [nəʊ] – никакой,

none [nʌn] – никто,

nobody/no one [ˈnəʊbədi]/[nəʊwʌn] – никто,

neither [ˈnaiðə] – ни тот ни другой, ни один,

nothing [ˈnʌθiŋ] – ничто.

There are no magazines for you today. – Для вас сегодня нет журналов. Are there any magazines for me today? – No, there are none. – Для меня сегодня есть журналы? Нет.

Neither road goes to the train station. – Ни одна из дорог не ведет к железнодорожному вокзалу.

Универсальные местоимения в английском языке указывают на каждый из предметов или на ряд однородных предметов. К универсальным местоимениям относятся местоимения:

each [i:tʃ]– каждый,

every [ˈevri] – каждый, всякий,

everybody [ˈevribɒdi] – все,

everything [ˈevriθiŋ]– всё,

both/either [bəʊθ] / [ˈaiðə]– и тот и другой, один из двух, любой из двух, оба, обе,

all [ɔ:l] – все, всё, вся, весь,

other/another [ˈʌðə] / [əˈnʌðə]– другой, другие.

Each apartment has a balcony. – В каждой квартире есть балкон.

I do my morning exercises every day. – Я каждый день делаю зарядку.

Everybody (=everyone) enjoyed the party. – Все наслаждались вечеринкой.

Here are Phil and Alex, you can talk to either boy. – Вот Фил и Алекс, ты можешь поговорить с любым из парней.

We both knew it was risky. – Мы оба знали, что это было опасно.

He’s forgotten all that I told him. – Он забыл все, что я говорила ему.

пройти тест на «Местоимения»

вернуться к выбору в разделе «Грамматика»

Курсы английского языка по уровням

Beginner

Экспресс-курс

«I LOVE ENGLISH»

Elementary

Космический квест

«БЫСТРЫЙ СТАРТ»

Intermediate

Обычная жизнь

КЕВИНА БРАУНА

В разработке

Advanced

Продвинутый курс

«ПРОРЫВ»

Практичные советы по изучению английского языка

Видеоурок: Личные местоимения. Personal Pronouns

Здравствуйте, друзья) В написании вышедшего из употребления местоимения ye (вы) допущена ошибка (8:46). Правильно: ye! We are very sorry)

Английские личные местоимения в таблице

В английском языке личные местоимения (Personal Pronouns) имеют два падежа — именительный и объектный:

Именительный падеж / Объектный падеж*

I — я / me — меня, мне

I like coffee. — Я люблю кофе. / Nick loves me. — Ник любит меня.

I can swim. — Я умею плавать. / Help me, please. — Помоги мне, пожалуйста.

he — он / him — его, ему

He likes coffee. — Он любит кофе. / Ann loves him. — Энн любит его.

He can swim. — Он умеет плавать. / Help him, please. — Помоги ему, пожалуйста.

she — она / her — её, ей

She likes coffee. — Она любит кофе. / Nick loves her. — Ник любит её.

She can swim. — Она умеет плавать. / Help her, please. — Помоги ей, пожалуйста.

it — он, она, оно (о вещах) / it — его (её), ему (ей)

It doesn’t work. — Он не работает (о компьютере). / Can Nick fix it? — Ник может починить его? (компьютер)

we — мы / us — нас, нам

We like coffee. — Мы любим кофе. / Mum loves us. — Мама любит нас.

We can swim. — Мы умеем плавать. / Help us, please. — Помоги нам, пожалуйста.

you — вы (ты) / you — вас, вам (тебя, тебе)

You like coffee. — Вы любите кофе (Ты любишь кофе). / Mum loves you. — Мама любит вас (Мама любит тебя).

You can swim. — Вы умеете плавать (Ты умеешь плавать). / Mum helps you. — Мама помогает вам (Мама помогает тебе).

they — они / them — их, им

They like coffee. — Они любят кофе. / Mum loves them. — Мама любит их.

They can swim. — Они умеют плавать. / Help them, please. — Помоги им, пожалуйста.

*Объектный падеж в английском соответствует косвенным падежам русского языка (то есть всем падежам, кроме именительного).

Личные местоимения в именительном падеже в предложении обычно стоят перед глаголом-сказуемым и выполняют роль подлежащего:

He likes coffee. — Он любит кофе.

Личные местоимения в объектном падеже в предложении обычно употребляются после глагола или предлога и выполняют роль дополнения:

Nick saw her yesterday. — Ник видел её вчера.

Why are you looking at her? — Почему ты смотришь на неё?

Лицо и число личных местоимений

Английские личные местоимения показывают лицо и число. Для удобства даны местоимения только в именительном падеже:

лицо / число

1 л.: I (ед. ч.) / we (мн. ч.)

2 л.: you (ед. ч.) / you (мн. ч.)

3 л.: he, she, it (ед. ч.) / they (мн. ч.)

Личные местоимения. Особенности употребления

I, me

Местоимение I (я) в английском языке всегда пишется с большой буквы, даже если стоит в середине предложения:

Yesterday I went to the cinema. — Вчера я ходил в кино.

Если I употребляется в паре с другим личным местоимением или существительным, то I ставится после него (my friend and I; I and my friend — неправильно):

Yesterday my friend and I went to the cinema. — Вчера мой друг и я (мы с другом) ходили в кино.

В разговорной речи в описанном выше предложении вместо I может употребляться me в значении «я», в этом случае me выполняет роль подлежащего:

Yesterday my friend and me went to the cinema. или Me and my friend went to the cinema yestreday.

My friend and I went to the cinema. — считается более правильным вариантом.

Как сказать на английском «это я»?

Это я. Ты можешь открыть дверь? У меня нет ключа.

It’s me. Can you open the door? I haven’t got the key.

В этом случае используется me. Можно сказать It is I, но этот вариант употребляется достаточно редко, так как является очень формальным.

You

На русский язык you мы переводим ты или вы. Но на самом деле в современном английском языке нет местоимения ты (оно когда-то было, но вышло из употребления). Сейчас есть только you — вы, которое употребляется по отношению к одному человеку или нескольким. Из контекста обычно понятно, к кому обращаются — к группе лиц или одному лицу. Так как изначально you — это местоимение в форме мн. ч., следовательно, сочетается оно всегда с глаголом в форме множественного числа:

You are a student. — Вы студент (Ты студент).

You are students. — Вы студенты.

Таким образом, русское местоимение ты на английском передают с помощью you — вы.

He, she, it

Местоимение he употребляется для обозначения лиц мужского пола (он), а she — для обозначения лиц женского пола (она):

This is Nick. He is my friend. — Это Ник. Он мой друг.

This is Ann. She is my friend. — Это Энн. Она моя подруга.

Местоимение it используется для обозначения неодушевленных предметов в единственном числе, абстрактных понятий, а также животных и растений. На русский язык it переводится «он, она, оно» в зависимости от рода соответствующего существительного в русском языке:

I’ve bought a bag. It is black. — Я купила сумку. Она черная.

Where is my notebook? ~ It is on the desk. — Где мой блокнот? ~ Он на столе.

Look at the window. It is dirty. — Посмотри на окно. Оно грязное.

He has got a dog. It is very big. — У него есть собака. Она очень большая.

Говоря о животных, можно использовать местоимения he или she, чтобы подчеркнуть их пол. Если это ваш питомец, и вы относитесь к нему как к члену семьи, то также можно использовать he или she.

В английском языке местоимение it также используется в качестве формального подлежащего в безличных предложениях, когда нет лица, которое совершает действие. Особенно, если речь идет о погоде или времени (в этом случае it is при переводе на русский опускаем):

It is already 10 o’clock. — Уже 10 часов.

It is windy. — Ветрено.

It также может иметь значение указательного местоимения «это»:

What is it? ~ It is a book. — Что это? ~ Это книга?

They

Местоимение they (они) заменяет одушевленные или неодушевленные существительные во множественном числе:

Look at the children. They are sleeping. — Посмотри на детей. Они спят.

Look at the flowers. They are so beautiful. — Посмотри на цветы. Они такие красивые.

Английские личные местоимения с переводом и произношением

Словарь: «Личные местоимения» (12сл.)

- I — я

- me — меня, мне

- he — он

- him — его, ему

- she — она

- her — её, ей

- it — он, она, оно (о вещах); его (её), ему (ей); это

- we — мы

- us — нас, нам

- you — вы (ты); вас, вам (тебя, тебе)

- they — они

- them — их, им

Чтобы открыть словарь, вам нужно авторизоваться.

Войти | О персональных словаря

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- ye (archaic nominative, dialectal plural)

- ya, yah, yer, yeh, y’, yo, yu, yuh (informal or eye dialect)

- -cha (informal, after /t/)

- -ja (informal, after /d/)

- u (informal, internet)

- yoo (eye dialect)

- yew (obsolete or eye dialect)

- youe, yow, yowe (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English you, yow, ȝow (object case of ye), from Old English ēow (“you”, dative case of ġē), from Proto-Germanic *iwwiz (“you”, dative case of *jīz), Western form of *izwiz (“you”, dative case of *jūz), from Proto-Indo-European *yūs (“you”, plural), *yū́.

Cognate with Scots you (“you”), Saterland Frisian jou (“you”), West Frisian jo (“you”), Low German jo, joe and oe (“you”), Dutch jou and u (“you”), Middle High German eu, iu (“you”, object pronoun), Latin vōs (“you”), Avestan 𐬬𐬋 (vō, “you”), Ashkun yë̃́ (“you”), Kamkata-viri šó (“you”), Sanskrit यूयम् (yūyám, “you”)

See usage notes. Ye, you and your are cognate with Dutch jij/je, jou, jouw; Low German ji, jo/ju, jug and German ihr, euch and euer respectively. Ye is also cognate with archaic Swedish I.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (stressed)

- (Received Pronunciation) enPR: yo͞o, IPA(key): /juː/ help,

- (General American) enPR: yo͞o, IPA(key): /ju/ help

- (General Australian) enPR: yo͞o, IPA(key): /jʉː/

- Rhymes: -uː

- (unstressed)

- (Received Pronunciation) enPR: yo͞o, IPA(key): /ju/

- (General American, General Australian) enPR: yə, IPA(key): /jə/ help

- Homophones: ewe, u, yew, yu, hew (in h-dropping dialects), hue (in h-dropping dialects)

When a word ending in /t/, /d/, /s/, or /z/ is followed by you, these may coalesce with the /j/, resulting in /tʃ/, /dʒ/, /ʃ/ and /ʒ/, respectively. This is occasionally represented in writing, e.g. gotcha (from got you) or whatcha doin’? (more formally what are you doing?).

Pronoun[edit]

you (second person, singular or plural, nominative or objective, possessive determiner your, possessive pronoun yours, singular reflexive yourself, plural reflexive yourselves)

- (object pronoun) The people spoken, or written to, as an object. [from 9th c.]

-

Both of you should get ready now.

-

1611, The Holy Bible, […] (King James Version), London: […] Robert Barker, […], →OCLC, Genesis 42:14, column 1:

-

And Ioſeph ſaid vnto them, That is it that I ſpake vnto you, ſaying, Ye are ſpies.

-

-

- (reflexive, now US colloquial) (To) yourselves, (to) yourself. [from 9th c.]

-

c. 1593 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedy of Richard the Third: […]”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, (please specify the act number in uppercase Roman numerals, and the scene number in lowercase Roman numerals):

-

If I may counsaile you, some day or two / Your Highnesse shall repose you at the Tower […].

-

-

1611, The Holy Bible, […] (King James Version), London: […] Robert Barker, […], →OCLC, Genesis XIX::

-

And Lot went out, and spake unto his sons in law, which married his daughters, and said, Up, get you out of this place; for the Lord will destroy this city.

-

- 1970, Donald Harington, Lightning Bug:

- ‘Pull you up a chair,’ she offered.

-

1975, Joseph Nazel, Death for Hire:

-

You’d better get you a gun and kill him before he kills you or somebody.

-

-

- (object pronoun) The person spoken to or written to, as an object. (Replacing thee; originally as a mark of respect.) [from 13th c.]

- c. 1485, Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, Book VIII:

- I charge you, as ye woll have my love, that ye warne your kynnesmen that ye woll beare that day the slyve of golde uppon your helmet.

- c. 1485, Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, Book VIII:

- (subject pronoun) The people spoken to or written to, as a subject. (Replacing ye.) [from 14th c.]

- You are all supposed to do as I tell you.

- 2016, VOA Learning English (public domain)

- Are you excited? ― Yes, I am excited!

- Are you excited? ― Yes, I am excited!

- (subject pronoun) The person spoken to or written to, as a subject. (Originally as a mark of respect.) [from 15th c.]

- c. 1395, Geoffrey Chaucer, «The Clerk’s Tale», Canterbury Tales, Ellesmere manuscript (c. 1410):

- certes lord / so wel vs liketh yow / And al youre werk / and euere han doon / þat we / Ne koude nat vs self deuysen how / We myghte lyuen / in moore felicitee […].

-

1814 July, [Jane Austen], chapter IX, in Mansfield Park: […], volume II, London: […] T[homas] Egerton, […], →OCLC, page 208:

-

You are right, Fanny, to protest against such an office, but you need not be afraid.

-

- c. 1395, Geoffrey Chaucer, «The Clerk’s Tale», Canterbury Tales, Ellesmere manuscript (c. 1410):

- (indefinite personal pronoun) Anyone, one; an unspecified individual or group of individuals (as subject or object). [from 16th c.]

- 2001, Polly Vernon, The Guardian, 5 May 2001:

- You can’t choose your family, your lovers are difficult and volatile, but, oh, you can choose your friends — so doesn’t it make much more sense to live and holiday with them instead?

- 2001, Polly Vernon, The Guardian, 5 May 2001:

Usage notes[edit]

- Originally, you was specifically plural (indicating multiple people), and specifically the object form (serving as the object of a verb or preposition; like us as opposed to we). The subject pronoun was ye, and the corresponding singular pronouns were thee and thou, respectively. In some forms of (older) English, you and ye doubled as polite singular forms, e.g. used in addressing superiors, with thee and thou being the non-polite singular forms. In the 1600s, some writers objected to the use of «singular you»[1] (compare objections to the singular they), but in modern English thee and thou are archaic and all but nonexistent and you is used for both the singular and the plural.

- Several forms of English now distinguish singular you from various marked plural forms, such as you guys, y’all, you-uns, or youse, though not all of these are completely equivalent or considered Standard English.

- The pronoun you is usually, but not always, omitted in imperative sentences. In affirmatives, it may be included before the verb (You go right ahead; You stay out of it); in negative imperatives, it may be included either before the don’t, or (more commonly) after it (Don’t you dare go in there; Don’t you start now).

- The pronoun you is also used in an indefinite sense: the generic you.

- See Appendix:English parts of speech for other personal pronouns.

Synonyms[edit]

- (subject pronoun: person spoken/written to):

- yer (UK eye dialect)

- plus the alternative forms listed above and at Appendix:English personal pronouns

- (subject pronoun: persons spoken/written to; plural): See Thesaurus:y’all

- (object pronoun: person spoken/written to): thee (singular, archaic), ye, to you, to thee, to ye

- (object pronoun: persons spoken/written to): ye, to you, to ye, to you all

- (one): one, people, they, them

Derived terms[edit]

- as you sow, so shall you reap

- because you touch yourself at night

- believe you me

- generic you

- how are you

- IOU

- mind you

- nice to meet you

- see you in the funny papers

- see you later

- smell you later

- thank you

- what do you say

- what say you

- you know

- you’d

- you’ll

- you’re

- you’ve

Descendants[edit]

- Belizean Creole: yu

- Bislama: yu

- Cameroon Pidgin: you

- Jamaican Creole: yuh

- Nigerian Pidgin: yu

- Sranan Tongo: yu

- Tok Pisin: yu

- Torres Strait Creole: yu

Translations[edit]

See also[edit]

Determiner[edit]

you

- The individual or group spoken or written to.

- Have you gentlemen come to see the lady who fell backwards off a bus?

- Used before epithets, describing the person being addressed, for emphasis.

- You idiot!

-

2015, Judi Curtin, Only Eva, The O’Brien Press, →ISBN:

-

‘You genius!’ I shouted in Aretta’s ear. ‘You absolute genius! Why didn’t you tell us you were so good?’

-

Derived terms[edit]

- y’all

- you guys

- you-uns

Translations[edit]

Verb[edit]

you (third-person singular simple present yous, present participle youing, simple past and past participle youed)

- (transitive) To address (a person) using the pronoun you (in the past, especially to use you rather than thou, when you was considered more formal).

- 1930, Barrington Hall, Modern Conversation, Brewer & Warren, page 239:

- Youing consists in relating everything in the conversation to the person you wish to flatter, and introducing the word “you” into your speech as often as possible.

- 1992, Barbara Anderson, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Victoria University Press, page 272:

- Now even Princess Anne had dropped it. Sarah had heard her youing away on television the other night just like the inhabitants of her mother’s dominions beyond the seas.

- 2004, Ellen Miller, Brooklyn Noir, Akashic Books, «Practicing»:

- But even having my very own personal pronoun was risky, because it’s pretty tough to keep stopped-hope stopped up when you are getting all youed up, when someone you really like keeps promising you scary, fun, exciting stuff—and even tougher for the of that moment to remain securely devoid of hope, to make smart, self-denying decisions with Dad youing me—the long ooo of it broad and extended, like a hand.

- 1930, Barrington Hall, Modern Conversation, Brewer & Warren, page 239:

Translations[edit]

Noun[edit]

you (plural yous)

- The name of the Latin-script letter U.

- 2004 Will Rogers, The Stonking Steps, p. 170

- It said, in a whispering, buzzing voice, «Gee-you-ess-ess-ay-dash-em-ee-ar-ar-wye-dash-em-eye-en-gee-oh-dash-pee-eye-pee-dash-pee-ee-ar-ar-wye-dash-pee-eye-en-gee-oh.»

- 2004 Will Rogers, The Stonking Steps, p. 170

Alternative forms[edit]

- u

References[edit]

- ^ The British Friend (November 1st, 1861), notes: «In 1659, Thomas Ellwood, Milton’s friend and scoretary, thus expresses himself—“ The corrupt and unsound form of speaking in the plural number to a single person, you to one instead of thou, contrary to the pure, plain, and simple language …»

Cameroon Pidgin[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- yu

Etymology[edit]

From English you.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ju/

Pronoun[edit]

you

- thou, thee, 2nd person singular subject and object personal pronoun

See also[edit]

Cameroonian Pidgin personal pronouns

| Subject personal pronouns | ||

|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | |

| 1st person | I | we, wu |

| 2nd person | you | wuna |

| 3rd person | i | dey |

| Object and topic personal pronouns | ||

| 1st person | me | we |

| 2nd person | you | wuna |

| 3rd person | yi, -am | dem, -am |

Japanese[edit]

Romanization[edit]

you

- Rōmaji transcription of よう

See also[edit]

- yō

Karawa[edit]

Noun[edit]

you

- water

References[edit]

- transnewguinea.org, citing D. C. Laycock, Languages of the Lumi Subdistrict (West Sepik District), New Guinea (1968), Oceanic Linguistics, 7 (1): 36-66

Leonese[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Old Leonese yo, from Vulgar Latin eo (attested from the 6th century), from Latin ego, from Proto-Italic *egō; akin to Greek εγώ (egó), Sanskrit अहम् (aham), all from Proto-Indo-European *éǵh₂.

Pronoun[edit]

you

- I

See also[edit]

Leonese personal pronouns

| nominative | disjunctive | dative | accusative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first person | singular | you | min1 | me | |

| plural | masculine | nosoutros | nos | ||

| feminine | nosoutras | ||||

| second person | singular | familiar | tu | ti1 | te |

| formal3 | vusté | ||||

| plural | familiar | masculine2 | vosoutros | vos | |

| feminine | vosoutras | ||||

| formal3 | vustedes | ||||

| third person | singular4 | masculine2 | él | ye | lu |

| feminine | eilla | la | |||

| plural | masculine2 | eillos | yes | los | |

| feminine | eillas | las | |||

| reflexive | — | sí1 | — |

- Not used with cun; cunmiéu, cuntiéu, and cunsiéu are used instead, respectively

- Masculine Leonese pronouns can be used when the gender of the subject is unknown or when the subject is plural and of mixed gender.

- Treated as if it were third-person for purposes of conjugation and reflexivity.

- A neuter form eillu exists too.

Mandarin[edit]

Romanization[edit]

you

- Nonstandard spelling of yōu.

- Nonstandard spelling of yóu.

- Nonstandard spelling of yǒu.

- Nonstandard spelling of yòu.

Usage notes[edit]

- Transcriptions of Mandarin speech into the Roman alphabet often do not distinguish between the critical tonal differences employed in the Mandarin language, using words such as this one without indication of tone.

Middle English[edit]

Etymology 1[edit]

Pronoun[edit]

you

- Alternative form of yow

Etymology 2[edit]

Pronoun[edit]

you

- (chiefly Northern and East Midland dialectal) Alternative form of þou

Mirandese[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Old Leonese you, from Vulgar Latin eo (attested from the 6th century), from Latin ego.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /jow/

Pronoun[edit]

you

- I (the first-person singular pronoun)

-

2008, Picä Tumilho (band) (music), “Ai que cochino!!! (ver. II)”, in Faíçca: Ua stória d’amor i laboura:

-

I you cun muita fuorça spetei bien la faca

- And I strongly skewered (with) the knife.

-

-

Pouye[edit]

Noun[edit]

you

- water

References[edit]

- transnewguinea.org, citing D. C. Laycock, Languages of the Lumi Subdistrict (West Sepik District), New Guinea (1968), Oceanic Linguistics, 7 (1): 36-66

Takia[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from Bargam yuw and Waskia yu.[1]

Noun[edit]

you

- water

References[edit]

- Malcolm Ross, Andrew Pawley, Meredith Osmond, The Lexicon of Proto-Oceanic: The Culture and Environment (2007, →ISBN

- ^ Loanwords in Takia, in Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook (edited by Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor), page 761

Terebu[edit]

Noun[edit]

you

- fire

Further reading[edit]

- Malcolm Ross, Proto Oceanic and the Austronesian Languages of Western Melanesia, Pacific Linguistics, series C-98 (1988)