Найдено 12 композиций

Kotoba no Iranai Yakusoku — Sana

1:30

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words — SANA

4:12

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words — SANA

4:13

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words — 言葉のいらない約束

4:31

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words (TV Size) — Sana

1:30

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words (Instrumetal) — HoneyWorks feat. sana

4:13

sm26305742 — 【Nitmegane ✕ halyosy】「A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words」Sang it — Неизвестен

4:11

sm26279917 — A promise that doesn’t need words tried to sing ver Senra — Неизвестен

4:13

sm26262664 — ♣「A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words」Sang it Uratanuki。 — Неизвестен

4:13

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words (言葉のいらない約束, Kotoba no Iranai Yakusoku), performed by sana, is the thirty-third ending of Naruto: Shippūden. It ran from episode 406 to 417, which then was followed by Rainbow’s Sky.

Video

Lyrics

Rōmaji

Hitori ja nai yo

Osoreru mono nante nai kara

Ikou sā me o ake te

Butsukatte ita

Hontō wa oitsuki taku te

Kizutsuke atte

Tsunagi tomeru kizuna hoshiku te

‘Gomen’ wasure nai de

Shinji te matte te

Mukae ni ikun da

Yūki no tomoshibi terashidase yowa sa o

Kizu datte itami datte wakeae ba heiki da

Kimi no senaka osu musun da yakusoku

Itsu datte hanare tatte

Shinjirareru kizuna wa mune ni nemutteru

Kanji

独りじゃないよ

恐れるものなんてないから

行こう さあ 目を開けて

ぶつかっていた

本当は追いつきたくて

傷つけ合って

繋ぎ止める 絆ほしくて

「ごめん」忘れないで

信じて待ってて

迎えに行くんだ

勇気の灯火 照らし出せ弱さを

傷だって痛みだって 分け合えば平気だ

君の背中押す 結んだ約束

いつだって離れたって

信じられる絆は 胸に眠ってる

English

You’re not alone

There’s nothing for you to fear,

So let’s go — open up your eyes!

We were butting heads

When we really just wanted to catch up to one another

Hurting each other

Seeking bonds to tie us together

‘I’m sorry’ Please don’t forget

Believe in me and wait for me

‘Cause I’m coming to see you!

Take the flame of courage and light up your weakness!

If we share the scars…the pain..we’ll be just fine

The promise you made that pushes you along

Creates a bond, sleeping in your heart

That you can always rely upon, even when we’re apart

Romaji (Full Version)

Hitori janai yo

Osoreru mono nante nai kara

Yukou saa me o akete

Butsukatte ita

Hontou wa oitsukitakute

Kizutsuke atte

Tsunagi tomeru kizuna hoshikute

«Gomen»

Wasurenaide

Shinjite mattete

Mukae ni iku nda

Yuuki no tomoshibi terashidase yowasa o

Kizu datte itami datte

Wakeaeba heiki da

Kimi no senaka osu musunda yakusoku

Itsudatte hanaretatte

Shinjirareru kizuna wa mune ni nemutteru

Hetakuso nanda yo

Osore shirazu hatenkou de sa

Kiku mimi motazu

Teki o tsukuru seigi moatte

«Hora ne»

Wasurenaide

Zutto sono mama de

Shiranakute ii yo

Yuuki no ashioto mayoi naki tsuyosa ga

Kizu datte itami datte

Kakikeshita heiki da

Kimi no senaka osu musunda yakusoku

Itsudatte hanaretatte

Shinjirareru kizuna wa mune ni nemutteru

Kotoba no nai yakusoku wa ima

Butsukari au koto mo hetta

Wakatteta

Kimi to boku wa majiwarazu ni

Wasurenaide

Zutto sono mama de

Aizu wa iranai

Yuuki no tomoshibi terashidase

Bokura wo

Kizu datte itami datte

Wakeaeba heiki da

Kimi no senaka osu musunda yakusoku

Itsudatte hanaretatte

Shinjirareru kizuna wa mune ni nemutteru

Characters

The characters in order of their appearances:

- Madara Uchiha

- Hashirama Senju

- Izuna Uchiha

- Itama Senju

- Kakashi Hatake

- Rin Nohara

- Kurama

- Kushina Uzumaki

- Minato Namikaze

- Obito Uchiha

- Tobi

- Orochimaru

- Kisame Hoshigaki

- Miru

- Yahiko

- Nagato

- Fusō

- Ise

- Jiraiya

- Asura Path

- Preta Path

- Naraka Path

- First Animal Path

- Nonō Yakushi

- Kabuto Yakushi

- Sasuke Uchiha

- Itachi Uchiha

- Sasori

- Sakumo Hatake

- Asuma Sarutobi

- Neji Hyūga

- Hizashi Hyūga

- Bunpuku

- Fugaku Uchiha

- Dan Katō

- Tsunade

- Shukaku

- Matatabi

- Isobu

- Son Gokū

- Kokuō

- Saiken

- Chōmei

- Gyūki

- Hinata Hyūga

- Hiashi Hyūga

- Hanabi Hyūga

- Gaara

- Naruto Uzumaki

- Demonic Statue of the Outer Path

- White Zetsu clone

- Black Zetsu

- Ten-Tails

- Тексты песен

- Sana

- A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words (OST Naruto: Shippuden Ending 33 ep 406-417)

Hitori ja nai yo

Osoreru mono nante nai kara

Ikou sā me o ake te

Butsukatte ita

Hontō wa oitsuki taku te

Kizutsuke atte

Tsunagi tomeru kizuna hoshiku te

‘Gomen’ wasure nai de

Shinji te matte te

Mukae ni ikun da

Yūki no tomoshibi terashidase yowa sa o

Kizu datte itami datte wakeae ba heiki da

Kimi no senaka osu musun da yakusoku

Itsu datte hanare tatte

Shinjirareru kizuna wa mune ni nemutteru

——————————————————

You’re not alone

There’s nothing for you to fear,

So let’s go — open up your eyes!

We were butting heads

When we really just wanted to catch up to one another

Hurting each other

Seeking bonds to tie us together

‘I’m sorry’ Please don’t forget

Believe in me and wait for me

‘Cause I’m coming to see you!

Take the flame of courage and light up your weakness!

If we share the scars…the pain..we’ll be just fine

The promise you made that pushes you along

Creates a bond, sleeping in your heart

That you can always rely upon, even when we’re apart

Еще Sana

Статистика страницы на pesni.guru ▼

Просмотров сегодня: 1

Популярное сейчас

- Григорий Лепс и Ирина Аллегрова — Я тебе не верю

- *ななん* — Undefined

- Сергей Пестов — Я хочу жить в России

- Паша Изотов — Нежно

- Айки Душевный — Ты Моя Бро (LIFE)

- FOLKPRO MUSIQUE — ПОПРАВИЛ ПАТЧ

- АрХангел — Оригами (feat. Белла)

- Rap Ring — Тесак VS Майкл Джексон

- Андрей «Орлуша» Орлов — Про надпись на Рейхстаге

- Vspak — Хочу

- Куба — Вставай Донбасс

- Песни — С тучки на тучку

- Kempel- — я так хочу тебя от тра**ть

- Чарльз Буковски — Стиль

- Мирослава — Забирай ( ost Он — Дракон )

A Promise That Doesn’t Need Words (OST Naruto: Shippuden Ending 33 ep 406-417) (исполнитель: Sana)

Hitori ja nai yo [bad word] mono nante nai kara Ikou sā me o ake te Butsukatte ita Hontō wa oitsuki taku te Kizutsuke atte Tsunagi [bad word] kizuna hoshiku te 'Gomen' wasure nai de Shinji te matte te Mukae ni ikun da Yūki no tomoshibi terashidase yowa sa o Kizu datte itami datte wakeae ba heiki da Kimi no senaka osu musun da yakusoku Itsu datte hanare tatte [bad word] kizuna wa mune ni [bad word] ----------------------------------------------------- You're not alone There's nothing for you to fear, So let's go - open up your eyes! We were butting heads When we really just wanted to catch up to one another Hurting each other Seeking bonds to tie us together 'I'm sorry' Please don't forget Believe in me and wait for me 'Cause [bad word] to see you! Take the flame of courage and light up your weakness! If we share the scars...the pain..we'll be just fine The promise you made that pushes you along Creates a bond, sleeping in your heart That you can always rely upon, even when we're apart

Послушать/Cкачать эту песню

Mp3 320kbps на стороннем сайте

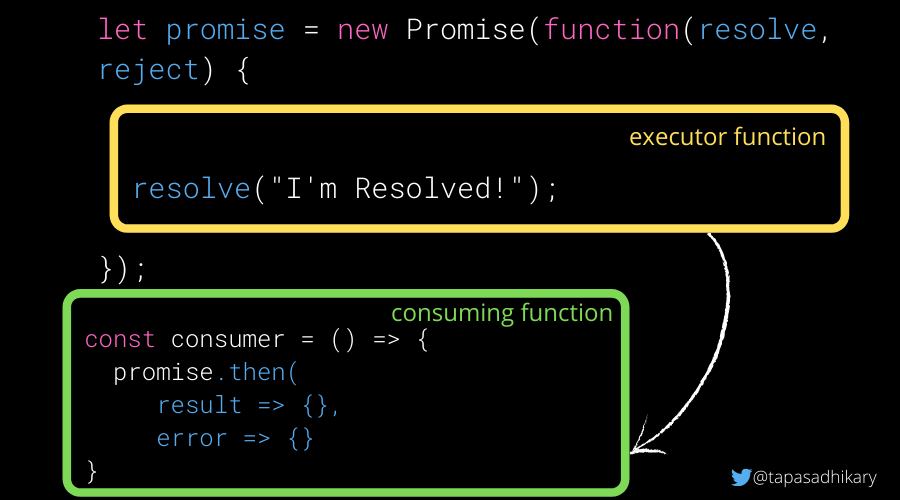

Promises are important building blocks for asynchronous operations in JavaScript. You may think that promises are not so easy to understand, learn, and work with. And trust me, you are not alone!

Promises are challenging for many web developers, even after spending years working with them.

In this article, I want to try to change that perception while sharing what I’ve learned about JavaScript Promises over the last few years. Hope you find it useful.

What is a Promise in JavaScript?

A Promise is a special JavaScript object. It produces a value after an asynchronous (aka, async) operation completes successfully, or an error if it does not complete successfully due to time out, network error, and so on.

Successful call completions are indicated by the resolve function call, and errors are indicated by the reject function call.

You can create a promise using the promise constructor like this:

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// Make an asynchronous call and either resolve or reject

});In most cases, a promise may be used for an asynchronous operation. However, technically, you can resolve/reject on both synchronous and asynchronous operations.

Hang on, don’t we have callback functions for async operations?

Oh, yes! That’s right. We have callback functions in JavaScript. But, a callback is not a special thing in JavaScript. It is a regular function that produces results after an asynchronous call completes (with success/error).

The word ‘asynchronous’ means that something happens in the future, not right now. Usually, callbacks are only used when doing things like network calls, or uploading/downloading things, talking to databases, and so on.

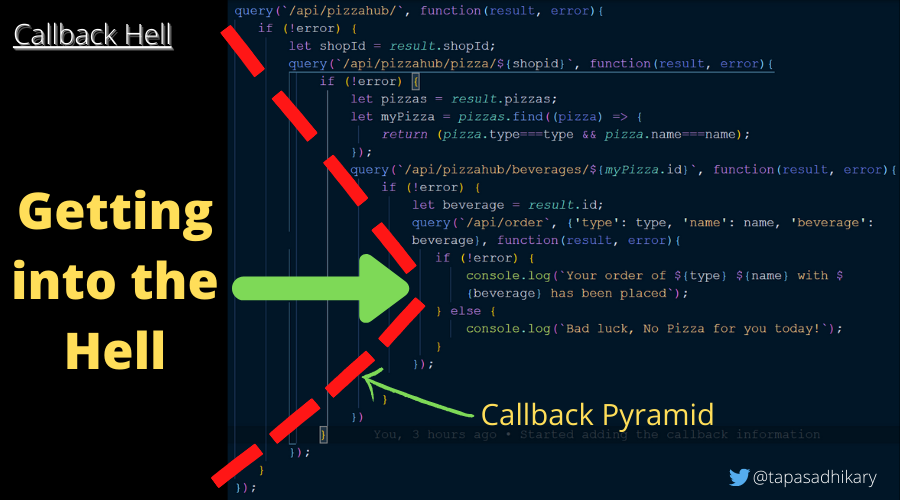

While callbacks are helpful, there is a huge downside to them as well. At times, we may have one callback inside another callback that’s in yet another callback and so on. I’m serious! Let’s understand this «callback hell» with an example.

How to Avoid Callback Hell – PizzaHub Example

Let’s order a Veg Margherita pizza 🍕 from the PizzaHub. When we place the order, PizzaHub automatically detects our location, finds a nearby pizza restaurant, and finds if the pizza we are asking for is available.

If it’s available, it detects what kind of beverages we get for free along with the pizza, and finally, it places the order.

If the order is placed successfully, we get a message with a confirmation.

So how do we code this using callback functions? I came up with something like this:

function orderPizza(type, name) {

// Query the pizzahub for a store

query(`/api/pizzahub/`, function(result, error){

if (!error) {

let shopId = result.shopId;

// Get the store and query pizzas

query(`/api/pizzahub/pizza/${shopid}`, function(result, error){

if (!error) {

let pizzas = result.pizzas;

// Find if my pizza is availavle

let myPizza = pizzas.find((pizza) => {

return (pizza.type===type && pizza.name===name);

});

// Check for the free beverages

query(`/api/pizzahub/beverages/${myPizza.id}`, function(result, error){

if (!error) {

let beverage = result.id;

// Prepare an order

query(`/api/order`, {'type': type, 'name': name, 'beverage': beverage}, function(result, error){

if (!error) {

console.log(`Your order of ${type} ${name} with ${beverage} has been placed`);

} else {

console.log(`Bad luck, No Pizza for you today!`);

}

});

}

})

}

});

}

});

}

// Call the orderPizza method

orderPizza('veg', 'margherita');Let’s have a close look at the orderPizza function in the above code.

It calls an API to get your nearby pizza shop’s id. After that, it gets the list of pizzas available in that restaurant. It checks if the pizza we are asking for is found and makes another API call to find the beverages for that pizza. Finally the order API places the order.

Here we use a callback for each of the API calls. This leads us to use another callback inside the previous, and so on.

This means we get into something we call (very expressively) Callback Hell. And who wants that? It also forms a code pyramid which is not only confusing but also error-prone.

There are a few ways to come out of (or not get into) callback hell. The most common one is by using a Promise or async function. However, to understand async functions well, you need to have a fair understanding of Promises first.

So let’s get started and dive into promises.

Understanding Promise States

Just to review, a promise can be created with the constructor syntax, like this:

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// Code to execute

});The constructor function takes a function as an argument. This function is called the executor function.

// Executor function passed to the

// Promise constructor as an argument

function(resolve, reject) {

// Your logic goes here...

}The executor function takes two arguments, resolve and reject. These are the callbacks provided by the JavaScript language. Your logic goes inside the executor function that runs automatically when a new Promise is created.

For the promise to be effective, the executor function should call either of the callback functions, resolve or reject. We will learn more about this in detail in a while.

The new Promise() constructor returns a promise object. As the executor function needs to handle async operations, the returned promise object should be capable of informing when the execution has been started, completed (resolved) or retuned with error (rejected).

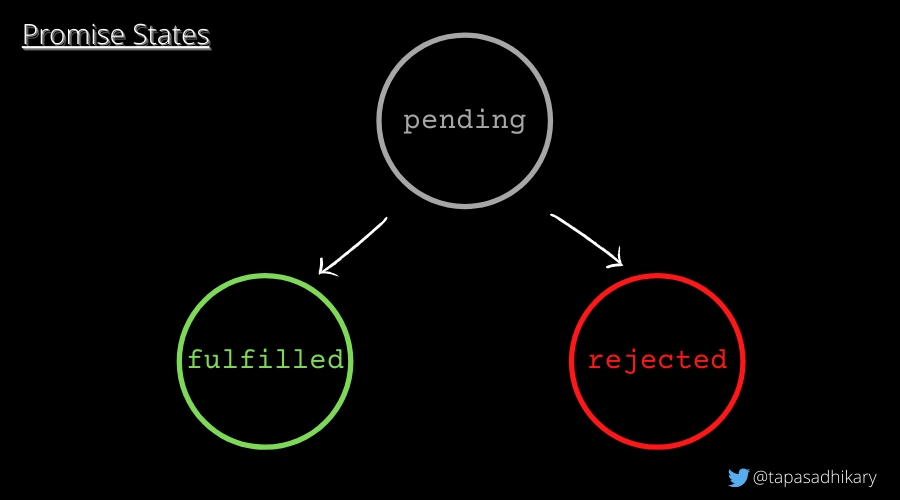

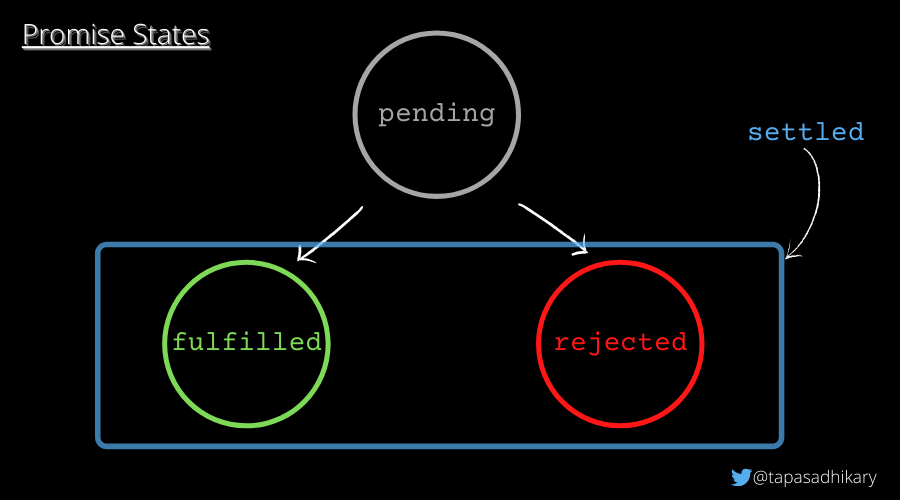

A promise object has the following internal properties:

state– This property can have the following values:

pending: Initially when the executor function starts the execution.fulfilled: When the promise is resolved.rejected: When the promise is rejected.

2. result – This property can have the following values:

undefined: Initially when thestatevalue ispending.value: Whenresolve(value)is called.error: Whenreject(error)is called.

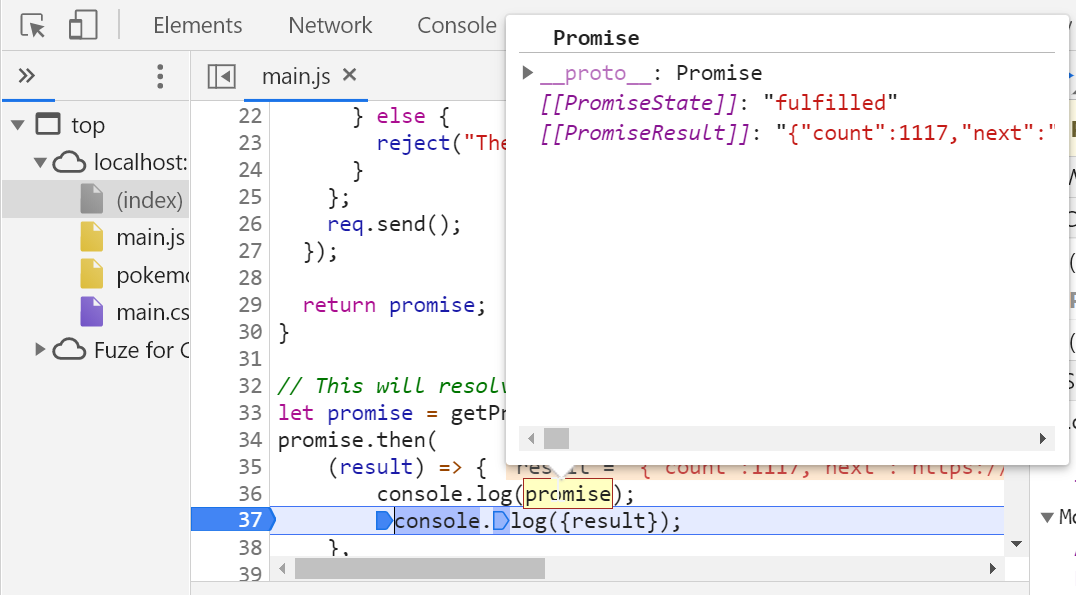

These internal properties are code-inaccessible but they are inspectable. This means that we will be able to inspect the state and result property values using the debugger tool, but we will not be able to access them directly using the program.

A promise’s state can be pending, fulfilled or rejected. A promise that is either resolved or rejected is called settled.

How promises are resolved and rejected

Here is an example of a promise that will be resolved (fulfilled state) with the value I am done immediately.

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve("I am done");

}); The promise below will be rejected (rejected state) with the error message Something is not right!.

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

reject(new Error('Something is not right!'));

});An important point to note:

A Promise executor should call only one

resolveor onereject. Once one state is changed (pending => fulfilled or pending => rejected), that’s all. Any further calls toresolveorrejectwill be ignored.

let promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve("I am surely going to get resolved!");

reject(new Error('Will this be ignored?')); // ignored

resolve("Ignored?"); // ignored

});In the example above, only the first one to resolve will be called and the rest will be ignored.

How to handle a Promise once you’ve created it

A Promise uses an executor function to complete a task (mostly asynchronously). A consumer function (that uses an outcome of the promise) should get notified when the executor function is done with either resolving (success) or rejecting (error).

The handler methods, .then(), .catch() and .finally(), help to create the link between the executor and the consumer functions so that they can be in sync when a promise resolves or rejects.

How to Use the .then() Promise Handler

The .then() method should be called on the promise object to handle a result (resolve) or an error (reject).

It accepts two functions as parameters. Usually, the .then() method should be called from the consumer function where you would like to know the outcome of a promise’s execution.

promise.then(

(result) => {

console.log(result);

},

(error) => {

console.log(error);

}

);If you are interested only in successful outcomes, you can just pass one argument to it, like this:

promise.then(

(result) => {

console.log(result);

}

);If you are interested only in the error outcome, you can pass null for the first argument, like this:

promise.then(

null,

(error) => {

console.log(error)

}

);However, you can handle errors in a better way using the .catch() method that we will see in a minute.

Let’s look at a couple of examples of handling results and errors using the .then and .catch handlers. We will make this learning a bit more fun with a few real asynchronous requests. We will use the PokeAPI to get information about Pokémon and resolve/reject them using Promises.

First, let us create a generic function that accepts a PokeAPI URL as argument and returns a Promise. If the API call is successful, a resolved promise is returned. A rejected promise is returned for any kind of errors.

We will be using this function in several examples from now on to get a promise and work on it.

function getPromise(URL) {

let promise = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

let req = new XMLHttpRequest();

req.open("GET", URL);

req.onload = function () {

if (req.status == 200) {

resolve(req.response);

} else {

reject("There is an Error!");

}

};

req.send();

});

return promise;

}Example 1: Get 50 Pokémon’s information:

const ALL_POKEMONS_URL = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon?limit=50';

// We have discussed this function already!

let promise = getPromise(ALL_POKEMONS_URL);

const consumer = () => {

promise.then(

(result) => {

console.log({result}); // Log the result of 50 Pokemons

},

(error) => {

// As the URL is a valid one, this will not be called.

console.log('We have encountered an Error!'); // Log an error

});

}

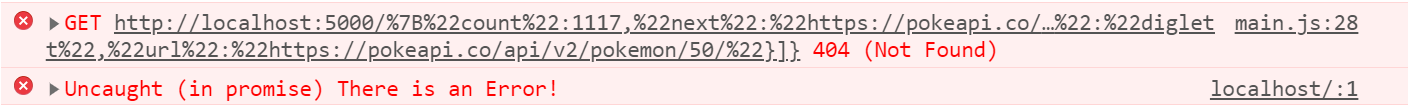

consumer();Example 2: Let’s try an invalid URL

const POKEMONS_BAD_URL = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon-bad/';

// This will reject as the URL is 404

let promise = getPromise(POKEMONS_BAD_URL);

const consumer = () => {

promise.then(

(result) => {

// The promise didn't resolve. Hence, it will

// not be executed.

console.log({result});

},

(error) => {

// A rejected prmise will execute this

console.log('We have encountered an Error!'); // Log an error

}

);

}

consumer();How to Use the .catch() Promise Handler

You can use this handler method to handle errors (rejections) from promises. The syntax of passing null as the first argument to the .then() is not a great way to handle errors. So we have .catch() to do the same job with some neat syntax:

// This will reject as the URL is 404

let promise = getPromise(POKEMONS_BAD_URL);

const consumer = () => {

promise.catch(error => console.log(error));

}

consumer();If we throw an Error like new Error("Something wrong!") instead of calling the reject from the promise executor and handlers, it will still be treated as a rejection. It means that this will be caught by the .catch handler method.

This is the same for any synchronous exceptions that happen in the promise executor and handler functions.

Here is an example where it will be treated like a reject and the .catch handler method will be called:

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

throw new Error("Something is wrong!");// No reject call

}).catch((error) => console.log(error)); How to Use the .finally() Promise Handler

The .finally() handler performs cleanups like stopping a loader, closing a live connection, and so on. The finally() method will be called irrespective of whether a promise resolves or rejects. It passes through the result or error to the next handler which can call a .then() or .catch() again.

Here is an example that’ll help you understand all three methods together:

let loading = true;

loading && console.log('Loading...');

// Gatting Promise

promise = getPromise(ALL_POKEMONS_URL);

promise.finally(() => {

loading = false;

console.log(`Promise Settled and loading is ${loading}`);

}).then((result) => {

console.log({result});

}).catch((error) => {

console.log(error)

});To explain a bit further:

- The

.finally()method makes loadingfalse. - If the promise resolves, the

.then()method will be called. If the promise rejects with an error, the.catch()method will be called. The.finally()will be called irrespective of the resolve or reject.

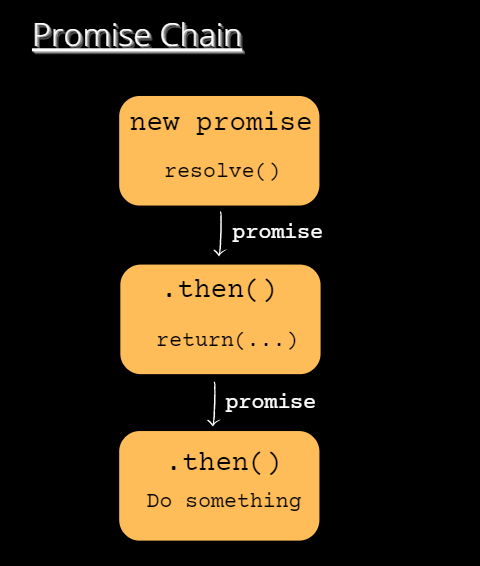

What is the Promise Chain?

The promise.then() call always returns a promise. This promise will have the state as pending and result as undefined. It allows us to call the next .then method on the new promise.

When the first .then method returns a value, the next .then method can receive that. The second one can now pass to the third .then() and so on. This forms a chain of .then methods to pass the promises down. This phenomenon is called the Promise Chain.

Here is an example:

let promise = getPromise(ALL_POKEMONS_URL);

promise.then(result => {

let onePokemon = JSON.parse(result).results[0].url;

return onePokemon;

}).then(onePokemonURL => {

console.log(onePokemonURL);

}).catch(error => {

console.log('In the catch', error);

});Here we first get a promise resolved and then extract the URL to reach the first Pokémon. We then return that value and it will be passed as a promise to the next .then() handler function. Hence the output,

https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/1/The .then method can return either:

- A value (we have seen this already)

- A brand new promise.

It can also throw an error.

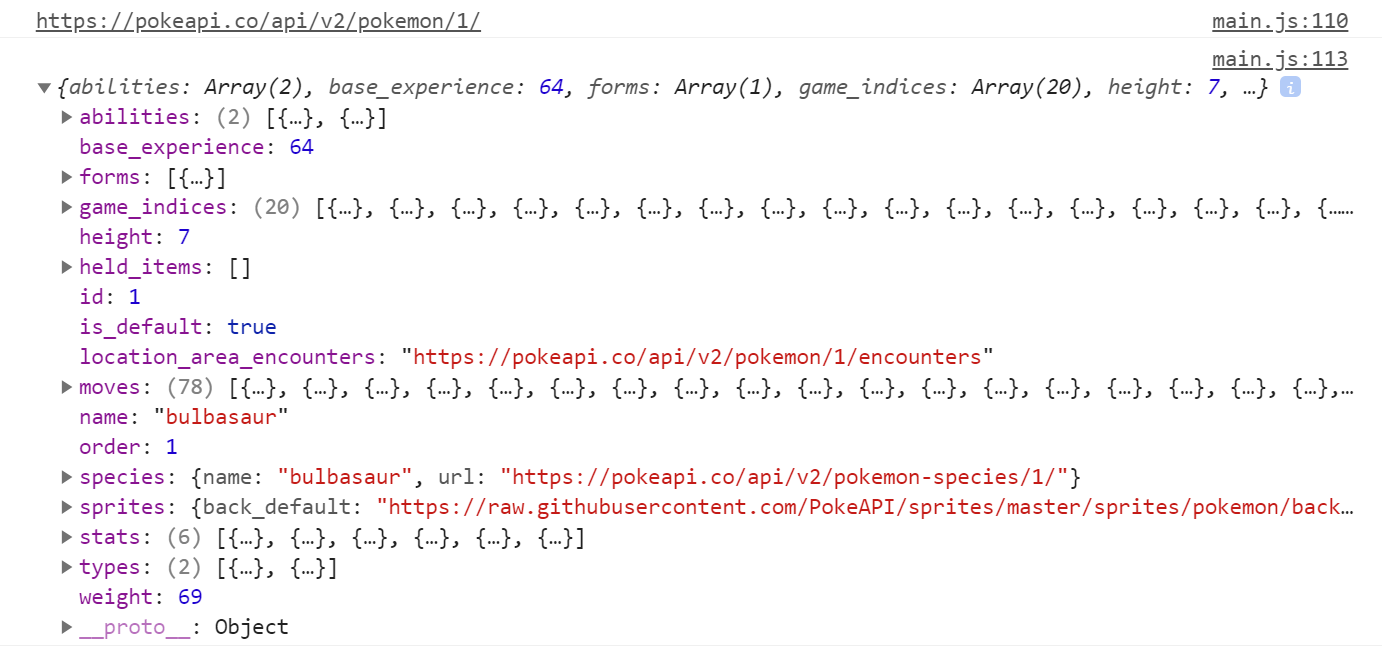

Here is an example where we have created a promise chain with the .then methods which returns results and a new promise:

// Promise Chain with multiple then and catch

let promise = getPromise(ALL_POKEMONS_URL);

promise.then(result => {

let onePokemon = JSON.parse(result).results[0].url;

return onePokemon;

}).then(onePokemonURL => {

console.log(onePokemonURL);

return getPromise(onePokemonURL);

}).then(pokemon => {

console.log(JSON.parse(pokemon));

}).catch(error => {

console.log('In the catch', error);

});In the first .then call we extract the URL and return it as a value. This URL will be passed to the second .then call where we are returning a new promise taking that URL as an argument.

This promise will be resolved and passed down to the chain where we get the information about the Pokémon. Here is the output:

In case there is an error or a promise rejection, the .catch method in the chain will be called.

A point to note: Calling .then multiple times doesn’t form a Promise chain. You may end up doing something like this only to introduce a bug in the code:

let promise = getPromise(ALL_POKEMONS_URL);

promise.then(result => {

let onePokemon = JSON.parse(result).results[0].url;

return onePokemon;

});

promise.then(onePokemonURL => {

console.log(onePokemonURL);

return getPromise(onePokemonURL);

});

promise.then(pokemon => {

console.log(JSON.parse(pokemon));

});

We call the .then method three times on the same promise, but we don’t pass the promise down. This is different than the promise chain. In the above example, the output will be an error.

How to Handle Multiple Promises

Apart from the handler methods (.then, .catch, and .finally), there are six static methods available in the Promise API. The first four methods accept an array of promises and run them in parallel.

- Promise.all

- Promise.any

- Promise.allSettled

- Promise.race

- Promise.resolve

- Promise.reject

Let’s go through each one.

The Promise.all() method

Promise.all([promises]) accepts a collection (for example, an array) of promises as an argument and executes them in parallel.

This method waits for all the promises to resolve and returns the array of promise results. If any of the promises reject or execute to fail due to an error, all other promise results will be ignored.

Let’s create three promises to get information about three Pokémons.

const BULBASAUR_POKEMONS_URL = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/bulbasaur';

const RATICATE_POKEMONS_URL = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/raticate';

const KAKUNA_POKEMONS_URL = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/kakuna';

let promise_1 = getPromise(BULBASAUR_POKEMONS_URL);

let promise_2 = getPromise(RATICATE_POKEMONS_URL);

let promise_3 = getPromise(KAKUNA_POKEMONS_URL);Use the Promise.all() method by passing an array of promises.

Promise.all([promise_1, promise_2, promise_3]).then(result => {

console.log({result});

}).catch(error => {

console.log('An Error Occured');

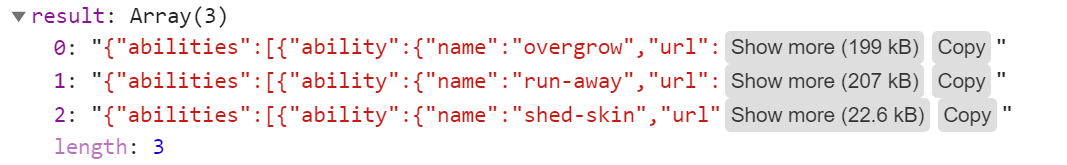

});Output:

As you see in the output, the result of all the promises is returned. The time to execute all the promises is equal to the max time the promise takes to run.

The Promise.any() method

Promise.any([promises]) — Similar to the all() method, .any() also accepts an array of promises to execute them in parallel. This method doesn’t wait for all the promises to resolve. It is done when any one of the promises is settled.

Promise.any([promise_1, promise_2, promise_3]).then(result => {

console.log(JSON.parse(result));

}).catch(error => {

console.log('An Error Occured');

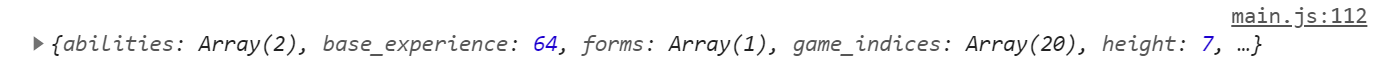

});The output would be the result of any of the resolved promises:

The Promise.allSettled() method

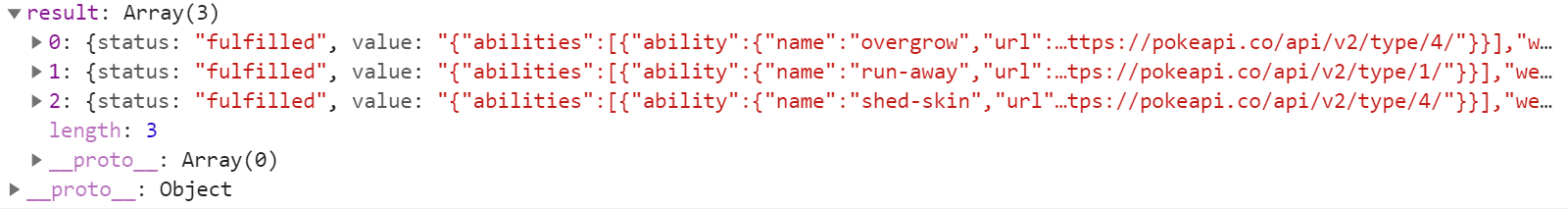

romise.allSettled([promises]) — This method waits for all promises to settle(resolve/reject) and returns their results as an array of objects. The results will contain a state (fulfilled/rejected) and value, if fulfilled. In case of rejected status, it will return a reason for the error.

Here is an example of all fulfilled promises:

Promise.allSettled([promise_1, promise_2, promise_3]).then(result => {

console.log({result});

}).catch(error => {

console.log('There is an Error!');

});Output:

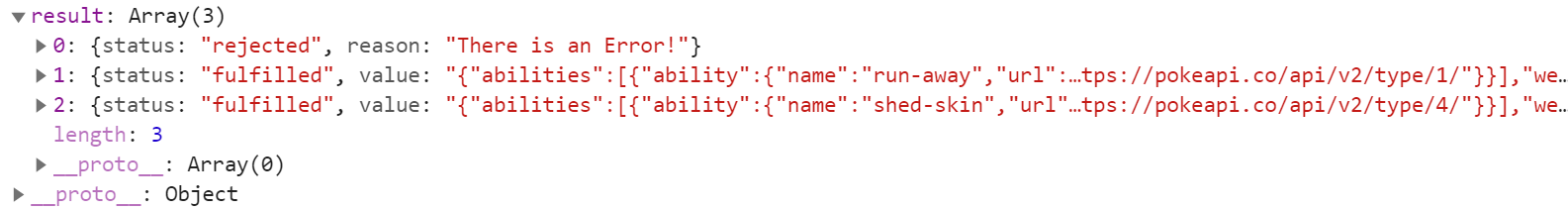

If any of the promises rejects, say, the promise_1,

let promise_1 = getPromise(POKEMONS_BAD_URL);The Promise.race() method

Promise.race([promises]) – It waits for the first (quickest) promise to settle, and returns the result/error accordingly.

Promise.race([promise_1, promise_2, promise_3]).then(result => {

console.log(JSON.parse(result));

}).catch(error => {

console.log('An Error Occured');

});Output the fastest promise that got resolved:

The Promise.resolve/reject methods

Promise.resolve(value) – It resolves a promise with the value passed to it. It is the same as the following:

let promise = new Promise(resolve => resolve(value));Promise.reject(error) – It rejects a promise with the error passed to it. It is the same as the following:

let promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => reject(error));Can we rewrite the PizzaHub example with Promises?

Sure, let’s do it. Let us assume that the query method will return a promise. Here is an example query() method. In real life, this method may talk to a database and return results. In this case, it is very much hard-coded but serves the same purpose.

function query(endpoint) {

if (endpoint === `/api/pizzahub/`) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve({'shopId': '123'});

})

} else if (endpoint.indexOf('/api/pizzahub/pizza/') >=0) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve({pizzas: [{'type': 'veg', 'name': 'margherita', 'id': '123'}]});

})

} else if (endpoint.indexOf('/api/pizzahub/beverages') >=0) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve({id: '10', 'type': 'veg', 'name': 'margherita', 'beverage': 'coke'});

})

} else if (endpoint === `/api/order`) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve({'type': 'veg', 'name': 'margherita', 'beverage': 'coke'});

})

}

}Next is the refactoring of our callback hell. To do that, first, we will create a few logical functions:

// Returns a shop id

let getShopId = result => result.shopId;

// Returns a promise with pizza list for a shop

let getPizzaList = shopId => {

const url = `/api/pizzahub/pizza/${shopId}`;

return query(url);

}

// Returns a promise with pizza that matches the customer request

let getMyPizza = (result, type, name) => {

let pizzas = result.pizzas;

let myPizza = pizzas.find((pizza) => {

return (pizza.type===type && pizza.name===name);

});

const url = `/api/pizzahub/beverages/${myPizza.id}`;

return query(url);

}

// Returns a promise after Placing the order

let performOrder = result => {

let beverage = result.id;

return query(`/api/order`, {'type': result.type, 'name': result.name, 'beverage': result.beverage});

}

// Confirm the order

let confirmOrder = result => {

console.log(`Your order of ${result.type} ${result.name} with ${result.beverage} has been placed!`);

}Use these functions to create the required promises. This is where you should compare with the callback hell example. This is so nice and elegant.

function orderPizza(type, name) {

query(`/api/pizzahub/`)

.then(result => getShopId(result))

.then(shopId => getPizzaList(shopId))

.then(result => getMyPizza(result, type, name))

.then(result => performOrder(result))

.then(result => confirmOrder(result))

.catch(function(error){

console.log(`Bad luck, No Pizza for you today!`);

})

}Finally, call the orderPizza() method by passing the pizza type and name, like this:

orderPizza('veg', 'margherita');

What’s next from here?

If you are here and have read through most of the lines above, congratulations! You should now have a better grip of JavaScript Promises. All the examples used in this article are in this GitHub repository.

Next, you should learn about the async function in JavaScript which simplifies things further. The concept of JavaScript promises is best learned by writing small examples and building on top of them.

Irrespective of the framework or library (Angular, React, Vue, and so on) we use, async operations are unavoidable. This means that we have to understand promises to make things work better.

Also, I’m sure you will find the usage of the fetch method much easier now:

fetch('/api/user.json')

.then(function(response) {

return response.json();

})

.then(function(json) {

console.log(json); // {"name": "tapas", "blog": "freeCodeCamp"}

});- The

fetchmethod returns a promise. So we can call the.thenhandler method on it. - The rest is about the promise chain which we learned in this article.

Before we end…

Thank you for reading this far! Let’s connect. You can @ me on Twitter (@tapasadhikary) with comments.

You may also like these other articles:

- JavaScript undefined and null: Let’s talk about it one last time!

- JavaScript: Equality comparison with ==, === and Object.is

- The JavaScript `this` Keyword + 5 Key Binding Rules Explained for JS Beginners

- JavaScript TypeOf – How to Check the Type of a Variable or Object in JS

That’s all for now. See you again with my next article soon. Until then, please take good care of yourself.

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

I don’t know whether .done is the right solution. However, I’d like to point out something to everyone who’s thinking about this stuff:

Handling exceptions in asynchronous code properly is not only a usability issue. Rather, I believe that it’s important from a security point of view. Allow me to elaborate.

Common wisdom seems to be that when there is an uncaught exception in a Node server app, keeping the server running will cause issues and leak resources, so you should simply try to gracefully shut down the server process, and start a new one. This means that if an attacker can figure out a way to trigger an uncaught exception in your app, they might be able to force you do expend a significant amount of CPU time by sending a specially crafted request. As a result, any remotely triggerable uncaught exception creates a denial of service vulnerability, because an attacker can leverage a low amount of network bandwidth into a high amount of CPU usage. A past example of this CPU-to-network leverage issue would be the slew of vulnerabilities discovered in 2011, caused by dictionaries implemented without collision-resistant hash functions; see the original slides on this, especially pp. 50 ff.

In a Rails app, having an uncaught exception in your simply results in a 500 page. In a Node app, it would seem to cause a vulnerability under typical conditions. This is disastrous for security, because it turns ordinary bugs into vulnerabilities.

Even worse, note that libraries tend to accumulate «dead» attack surface. For instance, for the longest time Rails was parsing YAML, even though almost nobody was using it. YAML support was what I call «dead» attack surface, because clearly it wasn’t used anymore. I presume that it was kept to avoid breaking compatibility — perhaps reasonably so. Of course YAML parsing turned out to be ludicrously insecure in the end, and that’s how we found out about it. But think about how many other such arcane code paths are exposed by library code in an average application. Most shouldn’t contain egregious vulnerabilities of the YAML kind, but it would be very strange indeed if none had conditions under which they’d throw exceptions. Note also that it’s very hard to guard against this by auditing.

To summarize, I suspect that the average Node server application contains several undiscovered DoS vulnerabilities owing to this problem. I’m not sure how to guard against this either.

My hope would be that in the future, we can use promises to evolve error handling in such a way that in most or all places, code will be able to safely throw unexpected exceptions without causing a vulnerability.

At the moment however, it seems to me that even with promises, there are still places where your code simply mustn’t throw an error, and if it does, you are in a tricky spot, potentially leading to vulnerabilities as described above.

I don’t have a solution, but I just wanted to point out with this comment that if we manage to solve the problem of uncaught exceptions with promises, it would not only be good for developer usability. Rather, it might also be an unexpected boon for the security of Node applications in the long run.

tl;dr: Node apps seem to suffer from a common class of DoS vulnerability. Promises don’t avert this at the moment, but they might in the future, if we can figure out how.

Update: Now regarding the specific .done proposal, it seems to me that it’s advocating exactly the problem I described above: Throwing unhandled exceptions into the event loop. So no, .done is definitely not the right solution.

Thanks to @stefanpenner for proof-reading a draft of this.