Noun

Being able to work again gave him his pride back.

Getting caught cheating stripped him of his pride.

Pride would not allow her to give up.

It’s a matter of pride that he does the work all by himself.

The novel is about a family consumed with pride and vanity.

They needed help, but their pride wouldn’t let them ask for it.

I had to swallow my pride and admit I made a mistake.

He showed a great pride in his family.

These young people are the pride of their community.

Verb

he prides himself on the quality of his writing

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Jim Trotter is a friend, a colleague, a man unafraid, a man of convictions, a family man, and a beacon of Black pride who has pushed on through the headwinds.

—

Both players take tremendous pride in representing their home state and proving that Massachusetts does have special basketball talent.

—

More generally, the Ayodhya movement, the movement for the building of the temple in Ayodhya, has enabled the B.J.P. to capitalize on this appetite for Hinduism and pride in a Hindu identity.

—

However, a police detective testified earlier this year that the shooter ran a neo-Nazi website, used gay and racial slurs while gaming online and posted an image of a rifle scope trained on a gay pride parade.

—

And boxer Joe Louis would take on and knock out Max Schmeling there in 1938, becoming the era’s hero for Black pride.

—

Or lean into your Maryland pride with the Yard Dog, a combo of three foot-long hot dogs stuffed into a bun and topped with crab dip and Old Bay potato sticks.

—

The plane, built in Kyiv in the 1980s and extensively overhauled after the country won independence from the Soviet Union, has long been Ukraine’s pride.

—

Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate KANSAS CITY, Mo. — All of the emotions seemed to smack Rodney Terry at once, a tidal wave of joy and pain and pride and sorrow.

—

In addition, Sophia prides herself in prioritizing her health and wellness.

—

New Englanders pride ourselves on our independence, our self-reliance.

—

Diamond Miller prides herself on her ability to score for Maryland women’s basketball.

—

Arriola, who has started all four FCD games this season and leads the team in assists (2), prides himself in his accountability.

—

The Republicans pride themselves on being the party that protects children.

—

Lee prides himself on his athleticism and defensive acumen, two traits increasingly sought after behind the plate.

—

As a point guard, West Salem’s Jackson Leach prides himself on knowing exactly where and when his teammates need the ball.

—

And in a city that prides itself as the center of the world, Trump saw himself as king.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘pride.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Pride is defined by Merriam-Webster as «reasonable self-esteem» or «confidence and satisfaction in oneself».[1] However, «pride» sometimes is used interchangeably with «conceit» or «arrogance» (among other words) with negative connotations.[2][3] Oxford defines it as «the quality of having an excessively high opinion of oneself or one’s own importance.»[4] This may be related to one’s own abilities or achievements, positive characteristics of friends or family, or one’s country. Richard Taylor defined pride as «the justified love of oneself»,[5] as opposed to false pride or narcissism. Similarly, St. Augustine defined it as «the love of one’s own excellence»,[6] and Meher Baba called it «the specific feeling through which egoism manifests.»[7]

Philosophers and social psychologists have noted that pride is a complex secondary emotion which requires the development of a sense of self and the mastery of relevant conceptual distinctions (e.g. that pride is distinct from happiness and joy) through language-based interaction with others.[8] Some social psychologists identify the nonverbal expression of pride as a means of sending a functional, automatically perceived signal of high social status.[9]

Pride is sometimes viewed as corrupt or as a vice, sometimes as proper or as a virtue. With a positive connotation, pride refers to a content sense of attachment toward one’s own or another’s choices and actions, or toward a whole group of people, and is a product of praise, independent self-reflection, and a fulfilled feeling of belonging.

With a negative connotation pride refers to a foolishly[10] and irrationally corrupt sense of one’s personal value, status or accomplishments,[11] used synonymously with hubris.

While some philosophers such as Aristotle (and George Bernard Shaw) consider pride (but not hubris) a profound virtue, some world religions consider pride’s fraudulent form a sin, such as is expressed in Proverbs 11:2 of the Hebrew Bible. In Judaism, pride is called the root of all evil. When viewed as a virtue, pride in one’s abilities is known as virtuous pride, the greatness of soul or magnanimity, but when viewed as a vice it is often known to be self-idolatry, sadistic contempt, vanity or vainglory. Other possible objects of pride are one’s ethnicity, and one’s sexual identity (especially LGBT pride).[citation needed]

Etymology[edit]

Proud comes from late Old English prut, probably from Old French prud «brave, valiant» (11th century) (which became preux in French), from Late Latin term prodis «useful», which is compared with the Latin prodesse «be of use».[12] The sense of «having a high opinion of oneself», not in French, may reflect the Anglo-Saxons’ opinion of the Norman knights who called themselves «proud».[13]

Ancient Greek philosophy[edit]

Aristotle identified pride (megalopsuchia, variously translated as proper pride, the greatness of soul and magnanimity)[14] as the crown of the virtues, distinguishing it from vanity, temperance, and humility, thus:

Now the man is thought to be proud who thinks himself worthy of great things, being worthy of them; for he who does so beyond his deserts is a fool, but no virtuous man is foolish or silly. The proud man, then, is the man we have described. For he who is worthy of little and thinks himself worthy of little is temperate, but not proud; for pride implies greatness, as beauty implies a goodsized body, and little people may be neat and well-proportioned but cannot be beautiful.[15]

He concludes then that

Pride, then, seems to be a sort of crown of the virtues; for it makes them more powerful, and it is not found without them. Therefore it is hard to be truly proud; for it is impossible without nobility and goodness of character.[16][17]

By contrast, Aristotle defined the vice of hubris as follows:

to cause shame to the victim, not in order that anything may happen to you, nor because anything has happened to you, but merely for your own gratification. Hubris is not the requital of past injuries; this is revenge. As for the pleasure in hubris, its cause is this: naive men think that by ill-treating others they make their own superiority the greater.[18]

Thus, although pride and hubris are often deemed the same thing, for Aristotle and many philosophers hubris is altogether an entirely different thing from pride.

Psychology[edit]

Since pride is classified as an emotion or passion, it is pride both cognitive and evaluative and that its object, that which it cognizes and evaluates, is the self and its properties, or something the proud individual identifies with.[11] Like guilt and shame, it is specifically described in the field as a self-conscious emotion that results from the evaluations of the self and one’s behavior according to internal and external standards.[19] This is further explained by the way pride results from satisfying or conforming to a standard while guilt or shame is an offshoot of defying it. An observation cites the lack of research that addresses pride because it is despised as well as valued in the individualist West where it is experienced as pleasurable.[20]

Emotion[edit]

In psychological terms, positive pride is «a pleasant, sometimes exhilarating, emotion that results from a positive self-evaluation».[21] It was added by Tracy et al. to the University of California, Davis, Set of Emotion Expressions (UCDSEE) in 2009, as one of three «self-conscious» emotions known to have recognizable expressions (along with embarrassment and shame).[22]

The term «fiero» was coined by Italian psychologist Isabella Poggi to describe the pride experienced and expressed in the moments following a personal triumph over adversity.[23][24] Facial expressions and gestures that demonstrate pride can involve a lifting of the chin, smiles, or arms on hips to demonstrate victory. Individuals may implicitly grant status to others based solely on their expressions of pride, even in cases in which they wish to avoid doing so. Indeed, some studies show that the nonverbal expression of pride conveys a message that is automatically perceived by others about a person’s high social status in a group.[9]

Behaviorally, pride can also be expressed by adopting an expanded posture in which the head is tilted back and the arms extended out from the body. This postural display is innate as it is shown in congenitally blind individuals who have lacked the opportunity to see it in others.[25]

Positive outcomes[edit]

A common understanding of pride is that it results from self-directed satisfaction with meeting the personal goals; for example, Weiner et al. have posited that positive performance outcomes elicit pride in an individual when the event is appraised as having been caused by him alone. Moreover, Oveis et al. conceptualize pride as a display of the strong self that promotes feelings of similarity to strong others, as well as differentiation from weak others. Seen in this light, pride can be conceptualized as a hierarchy-enhancing emotion, as its experience and display helps rid negotiations of conflict.[26]

Pride involves exhilarated pleasure and a feeling of accomplishment. It is related to «more positive behaviors and outcomes in the area where the individual is proud» (Weiner, 1985). Pride is generally associated with positive social behaviors such as helping others and outward promotion. Along with hope, it is also often described as an emotion that facilitates performance attainment, as it can help trigger and sustain focused and appetitive effort to prepare for upcoming evaluative events. It may also help enhance the quality and flexibility of the effort expended (Fredrickson, 2001). According to Bagozzi et al., pride can have positive benefits of enhancing creativity, productivity, and altruism. For instance, it has been found that in terms of school achievement, pride is associated with a higher GPA in low neighborhood socioeconomic environments, whereas in more advantaged neighborhoods, pride is associated with a lower GPA.[27]

Economics[edit]

In the field of economic psychology, pride is conceptualized in a spectrum ranging from «proper pride», associated with genuine achievements, and «false pride», which can be maladaptive or even pathological. Lea et al. have examined the role of pride in various economic situations and claim that in all cases pride is involved because economic decisions are not taken in isolation from one another, but are linked together by the selfhood of the people who take them.[28] Understood in this way, pride is an emotional state that works to ensure that people take financial decisions that are in their long-term interests, even when in the short term they would appear irrational.

Sin and self-acceptance[edit]

Inordinate self-esteem is called «pride».[29] Classical Christian theology views pride as being the result of high self-esteem, and thus high self-esteem was viewed as the primary human problem, but beginning in the 20th century, «humanistic psychology» diagnosed the primary human problem as low self-esteem stemming from a lack of belief in one’s «true worth». Carl Rogers observed that most people «regard themselves as worthless and unlovable.» Thus, they lack self-esteem.[30]

In the King James Bible, people exhibiting excess pride are labeled with the term, «Haughty».

«pride comes before a fall»— 1611, King James Version of the Bible, Book of Proverbs, 16:18

Terry Cooper conceptualized in 2003 excessive pride (along with low self-esteem) as an important paradigm in describing the human condition. He examines and compares the Augustinian-Niebuhrian conviction that pride is primary, the feminist concept of pride as being absent in the experience of women, the humanistic psychology position that pride does not adequately account for anyone’s experience, and the humanistic psychology idea that if pride emerges, it is always a false front designed to protect an undervalued self.[31]

He considers that the work of certain neo-Freudian psychoanalysts, namely Karen Horney, offers promise in dealing with what he calls a «deadlock between the overvalued and undervalued self» (Cooper, 112–3).

Cooper refers to their work in describing the connection between religious and psychological pride as well as sin to describe how a neurotic pride system underlies an appearance of self-contempt and low self-esteem:

The «idealized self,» the «tyranny of the should,» the «pride system» and the nature of self-hate all point toward the intertwined relationship between neurotic pride and self-contempt. Understanding how a neurotic pride system underlies an appearance of self-contempt and low self-esteem. (Cooper, 112–3).

Thus, hubris, which is an exaggerated form of self-esteem, is sometimes actually a lie used to cover the lack of self-esteem the committer of pride feels deep down.

Hubris and group narcissism[edit]

Hubris itself is associated with more intra-individual negative outcomes and is commonly related to expressions of aggression and hostility (Tangney, 1999). As one might expect, Hubris is not necessarily associated with high self-esteem but with highly fluctuating or variable self-esteem. Excessive feelings of hubris have a tendency to create conflict and sometimes terminating close relationships, which has led it to be understood as one of the few emotions with no clear positive or adaptive functions (Rhodwalt, et al.).[citation needed]

Several studies by UC Davis psychologist Cynthia Picket about group pride, have shown that groups that boast, gloat or denigrate others tend to become a group with low social status or to be vulnerable to threats from other groups.[32] Suggesting that «hubristic, pompous displays of group pride might be a sign of group insecurity as opposed to a sign of strength,» she states that those that express pride by being filled with humility whilst focusing on members’ efforts and hard work tend to achieve high social standing in both the adult public and personal eyes.

Research from the University of Sydney, have found that hubristic pride was positively correlated with arrogance and self-aggrandizement and promotes prejudice and discrimination. But authentic pride was associated with self-confidence and accomplishment and promotes more positive attitudes toward outgroups and stigmatized individuals.[33]

Ethnic[edit]

Across the world[edit]

Pride in ones own ethnicity or ones own culture seems to universally have positive connotations,[34][35][36][37] though like earlier discussions on pride, when pride tips into hubris, people have been known to commit atrocities.[38]

Types of Pride across the world seem to have a broad variety. The difference of type may have no greater contrast than that between the US and China.[39] In the US, individual pride tends and seems to be held more often in thought. The people in China seem to hold greater views for the nation as a whole.[40]

The value of Pride in the individual or the society as a whole seems to be a running theme and debate among cultures.[41] This debate shadows the discussion on Pride so much so that perhaps the discussion on Pride shouldn’t be about whether Pride is necessarily good or bad, but about which form of it is the most useful.[41]

German[edit]

In Germany, «national pride» («Nationalstolz») is often associated with the former Nazism. Strong displays of national pride are therefore considered poor taste by many Germans. There is an ongoing public debate about the issue of German patriotism. The World Cup in 2006, held in Germany, saw a wave of patriotism sweep the country in a manner not seen for many years. Although many were hesitant to show such blatant support as the hanging of the national flag from windows, as the team progressed through the tournament, so too did the level of support across the nation.[42]

Asian[edit]

Asian pride in modern slang refers mostly to those of East Asian descent, though it can include anyone of Asian descent. Asian pride was originally fragmented, as Asian nations have had long conflicts with each other, examples are the old Japanese and Chinese religious beliefs of their superiority. Asian pride emerged prominently during European colonialism.[43] At one time, Europeans controlled 85% of the world’s land through colonialism, resulting in anti-Western feelings among Asian nations.[43] Today, some Asians still look upon European involvement in their affairs with suspicion.[43] In contrast, Asian empires are prominent and are proudly remembered by adherents to Asian Pride.

There is an emerging discourse of Chinese pride that unfolds complex histories and maps of privileges and empowerments. In a deeper sense, it is a strategic positioning, aligned with approaches such as «Asia as method»,[44] to invite more diverse resistances in language, culture, and practices, in challenging colonial, imperial dominations, and being critical of Eurocentric epistemologies.[45] In more specific cases, it examines the Sinophone circulations of power relations connecting the transnational to the local, for example, a particular set of Chinese-Canadian relations between China’s increasing industrial materiality and output in which pride becomes an expansionist reach and mobilization of capital, Canada’s active interests in tapping into Asian and Chinese labours, markets, and industrial productions, and the intersected cultural politics of ‘Chinese-ness’ in an East Pacific British Columbia city where ‘Chinese’ has been tagged as a majority-minority.[45]

Black[edit]

Black pride is a slogan used primarily in the United States to raise awareness for a black racial identity. The slogan has been used by African Americans of sub-Saharan African origin to denote a feeling of self-confidence, self-respect, celebrating one’s heritage, and being proud of one’s worth.

White[edit]

White pride is a slogan mainly (but not exclusively) used by white separatist, white nationalist, neo-Nazi and white supremacist organizations in the United States for a white race identity.[46] White pride also consists of white ethnic/cultural pride.

Mad[edit]

Bed Push at Mad Pride parade in Cologne, Germany, in 2016

Mad pride is a worldwide movement and philosophy that mentally ill people should be proud of their madness. It advocates mutual support and rallies for their rights,[47] and aims to popularize the word «mad» as a self-descriptor.[48]

LGBT[edit]

Gay pride is a worldwide movement and philosophy asserting that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals should be proud of their sexual orientation and gender identity. LGBT pride advocates equal rights and benefits for LGBT people.[49][50][51] The movement has three main premises: that people should be proud of their sexual orientation and gender identity, that sexual diversity is a gift, and that sexual orientation and gender identity are inherent and cannot be intentionally altered.[52]

The word «pride» is used in this case as an antonym for «shame». It is an affirmation of self and community. The modern gay pride movement began after the Stonewall riots of the late 1960s. In June 1970, the first pride parade in the United States commemorated the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall riots—the nearly week-long uprising between New York City youth and police officers following a raid of Stonewall Inn.[53]

Vanity[edit]

In conventional parlance, vanity sometimes is used in a positive sense to refer to a rational concern for one’s appearance, attractiveness, and dress and is thus not the same as pride. However, it also refers to an excessive or irrational belief in one’s abilities or attractiveness in the eyes of others and may in so far be compared to pride. The term Vanity originates from the Latin word vanitas meaning emptiness, untruthfulness, futility, foolishness and empty pride.[54] Here empty pride means a fake pride, in the sense of vainglory, unjustified by one’s own achievements and actions, but sought by pretense and appeals to superficial characteristics.

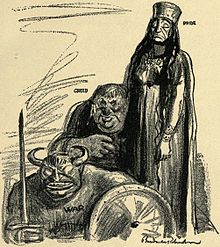

Jacques Callot, Pride (Vanity), probably after 1621

In many religions, vanity is considered a form of self-idolatry, in which one rejects God for the sake of one’s own image, and thereby becomes divorced from the graces of God. The stories of Lucifer and Narcissus (who gave us the term narcissism), and others, attend to a pernicious aspect of vanity. In Western art, vanity was often symbolized by a peacock, and in Biblical terms, by the Whore of Babylon. During the Renaissance, vanity was invariably represented as a naked woman, sometimes seated or reclining on a couch. She attends to her hair with a comb and mirror. The mirror is sometimes held by a demon or a putto. Other symbols of vanity include jewels, gold coins, a purse, and often by the figure of death himself.

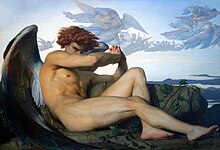

«All Is Vanity» by C. Allan Gilbert, evoking the inevitable decay of life and beauty toward death

Often we find an inscription on a scroll that reads Omnia Vanitas («All is Vanity»), a quote from the Latin translation of the Book of Ecclesiastes.[55] Although that phrase, itself depicted in a type of still life, vanitas, originally referred not to an obsession with one’s appearance, but to the ultimate fruitlessness of man’s efforts in this world, the phrase summarizes the complete preoccupation of the subject of the picture.

«The artist invites us to pay lip-service to condemning her», writes Edwin Mullins, «while offering us full permission to drool over her. She admires herself in the glass, while we treat the picture that purports to incriminate her as another kind of glass—a window—through which we peer and secretly desire her.»[56] The theme of the recumbent woman often merged artistically with the non-allegorical one of a reclining Venus.

In his table of the seven deadly sins, Hieronymus Bosch depicts a bourgeois woman admiring herself in a mirror held up by a devil. Behind her is an open jewelry box. A painting attributed to Nicolas Tournier, which hangs in the Ashmolean Museum, is An Allegory of Justice and Vanity. A young woman holds a balance, symbolizing justice; she does not look at the mirror or the skull on the table before her. Vermeer’s famous painting Girl with a Pearl Earring is sometimes believed to depict the sin of vanity, as the young girl has adorned herself before a glass without further positive allegorical attributes.[57] All is Vanity, by Charles Allan Gilbert (1873–1929), carries on this theme. An optical illusion, the painting depicts what appears to be a large grinning skull. Upon closer examination, it reveals itself to be a young woman gazing at her reflection in the mirror of her vanity table.

Such artistic works served to warn viewers of the ephemeral nature of youthful beauty, as well as the brevity of human life and the inevitability of death.

See also[edit]

- Confidence

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Grandiose delusions

- Haughtiness

- Hubris

- Narcissism

- Overconfidence effect

- Self-serving bias

- Vanity

- Accomplishment

- Groupthink

- Icarus complex

- Selfishness

- Seven virtues

- The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things

- Vanity gallery

- Victory disease

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Definition of PRIDE».

- ^ «Definition of CONCEIT».

- ^ «Definition of ARROGANCE».

- ^ The New Oxford Dictionary of English Clarendon Press 1998

- ^ Taylor, Richard (1995). Restoring Pride: The Lost Virtue of Our Age. Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781573920247.

- ^ «Est autem superbia amor proprie excellentie, et fuit initium peccati superbia.»«De amore liber IV». Archived from the original on 2008-11-05. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses. 2. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. p. 72. ISBN 978-1880619094.

- ^ Sullivan, GB (2007). «Wittgenstein and the grammar of pride: The relevance of philosophy to studies of self-evaluative emotions». New Ideas in Psychology. 25 (3): 233–252. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2007.03.003.

- ^ a b Shariff, Azim F.; Tracy, Jessica L. (2009). «Knowing who’s boss: Implicit perceptions of status from the nonverbal expression of pride». Emotion. 9 (5): 631–639. doi:10.1037/a0017089. PMID 19803585.

- ^ «Definition of HUBRIS». www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- ^ a b Steinvorth, Ulrich (2016). Pride and Authenticity. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 9783319341163.

- ^ Article from Free Online Dictionary, accessed 9 Nov. 2008

- ^ Article from Online Etymology Dictionary Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 20 June 2014

- ^ Aristotle (2004). The Nicomachean Ethics By Aristotle, James Alexander, Kerr Thomson, Hugh Tredennick, Jonathan Barnes translators. ISBN 9780140449495. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- ^ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 4.3 Archived December 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine; also available here Sacred Texts – Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine; and here alternate translation at Perseus

- ^ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 4.3 Archived December 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hamilton, Christopher (2003). Understanding Philosophy for AS Level AQA, by Christopher Hamilton (Google Books). ISBN 9780748765607. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- ^ Aristotle Rhetoric 1378b (Greek text and English translation available at the Perseus Project).

- ^ Bechtel, Robert; Churchman, Arza (2002). Handbook of Environmental Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 547. ISBN 978-0471405948.

- ^ Leontiev, Dmitry (2016). Positive Psychology in Search for Meaning. Oxon: Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 9781138806580.

- ^ Lewis, M.; Takai-Kawakami, K.; Kawakami, K.; Sullivan, M. W. (2010). «Cultural differences in emotional responses to success and failure». International Journal of Behavioral Development. 34 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1177/0165025409348559. PMC 2811375. PMID 20161610.

- ^ Tracy, J. L.; Robins, R. W.; Schriber, R. A. (2009). «Development of a FACS-verified set of basic and self-conscious emotion expressions». Emotion. 9 (4): 554–559. doi:10.1037/a0015766. PMID 19653779.

- ^ Lazzaro, Nicole (8 March 2004). «Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion Without Story» (PDF). XEODesign.

- ^ Language, Body (2010-10-23). «Sincerity Secret # 20: Fiero Feels Good – Mirror Neurons». Body Language Success. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- ^ Tracy, Jessica L.; Matsumoto, David (19 August 2008). «The spontaneous expression of pride and shame: Evidence for biologically innate nonverbal displays». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (33): 11655–11660. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511655T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802686105. JSTOR 25463738. PMC 2575323. PMID 18695237.

- ^ Oveis, C.; Horberg, E. J.; Keltner, D. (2010). «Compassion, pride, and social intuitions of self-other similarity». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 98 (4): 618–630. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.307.534. doi:10.1037/a0017628. PMID 20307133.

- ^ Byrd, C. M.; Chavous, T. M. (2009). «Racial identity and academic achievement in the neighborhood context: a multilevel analysis «. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 38 (4): 544–559. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9381-9. PMID 19636727. S2CID 45063561.

- ^ Lea, S. E. G.; Webley, P. (1996). «Pride in economic psychology». Journal of Economic Psychology. 18 (2–3): 323–340. doi:10.1016/s0167-4870(97)00011-1.

- ^ «pride, n.1». Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

The quality of being proud.

- ^ Terry D. Cooper, Sin, Pride & Self-Acceptance: The Problem of Identity in Theology & Psychology (InterVar sity, 2003), 40, 87, 95.

- ^ Cooper, T. D. (2003). Sin, pride & self-acceptance: the problem of identity in theology & psychology. Chicago: InterVarsity Press.

- ^ Study is currently in revision

- ^ «Pride and Prejudice: How Feelings About the Self Influence Judgments of Others». ResearchGate. Retrieved 2021-02-08.

- ^ Specia, Megan; Kwai, Isabella (24 October 2022). «Sunak’s Ascent Is a Breakthrough for Diversity, With Privilege Attached». The New York Times.

- ^ Gemechu, Berhanu (7 June 2022). «The Ethiopians changing their names as a show of pride». BBC News.

- ^ Pullar, Gordon L. (1992). «Ethnic identity, cultural pride, and generations of baggage: a personal experience». Arctic Anthropology. 29 (2): 182–191. JSTOR 40316321. OCLC 5547262802.

- ^ Castro, Felipe González; Stein, Judith A.; Bentler, Peter M. (July 2009). «Ethnic Pride, Traditional Family Values, and Acculturation in Early Cigarette and Alcohol Use Among Latino Adolescents». The Journal of Primary Prevention. 30 (3–4): 265–292. doi:10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z. PMC 2818880. PMID 19415497.

- ^ Dimijian, Gregory G. (July 2010). «Warfare, genocide, and ethnic conflict: a Darwinian approach». Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 23 (3): 292–300. doi:10.1080/08998280.2010.11928637. PMC 2900985. PMID 21240320.

- ^ Liu, Conghui; Li, Jing; Chen, Chuansheng; Wu, Hanlin; Yuan, Li; Yu, Guoliang (19 May 2021). «Individual Pride and Collective Pride: Differences Between Chinese and American Corpora». Frontiers in Psychology. 12: 513779. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.513779. PMC 8170025. PMID 34093292.

- ^ Robson, David (19 January 2017). «How East and West think in profoundly different ways». BBC Future.

- ^ a b Van Osch, Yvette M. J.; Breugelmans, Seger M.; Zeelenberg, Marcel; Fontaine, Johnny R. J. (2013). «The meaning of pride across cultures». Components of Emotional Meaning. pp. 377–387. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199592746.003.0026. ISBN 978-0-19-959274-6.

- ^ Sullivan, G. B. (2009). Germany during the 2006 World Cup: The role of television in creating a national narrative of pride and «party patriotism». In Castelló, E., Dhoest, A. & O’Donnell, H. (Eds.), The Nation on Screen, Discourses of the National in Global Television. Cambridge Scholars Press: Cambridge.

- ^ a b c Langguth, Gerd. German Foreign Affairs Review. «Dawn of the ‘Pacific’ Century?» 1996. June 30, 2007. «Asian Values». Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Chen, K. H. (2010). Asia as method: Toward deimperialization. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- ^ a b Xiao, Y (2014). «Radical Feelings in the ‘Liberation Zone’: Active Chinese Canadian Citizenship in Richmond, BC». Citizenship Education Research Journal. 4 (1): 13–28. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08.

- ^ Dobratz & Shanks-Meile 2001

- ^ Cohen, Oryx (9 March 2017). «The Power of ‘Healing Voices’«. The Mighty. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Graham, Ben (5 June 2018). «MAD Pride». WayAhead. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ «Pride celebrated worldwide». www.pridesource.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-28. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ «GAY PRIDE IN EUROPE LOOKS GLOBALLY». direland.typepad.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ «Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Equality -an Issue for us All». www.ucu.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-12-09. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ «Gay and Lesbian History Month» (PDF). www.bates.ctc.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ «WGBH American Experience — Inside American Experience». American Experience. Archived from the original on 2016-04-22. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- ^ «William Whitaker’s Words».

- ^ James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects & Symbols in Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 318.

- ^ Edwin Mullins, The Painted Witch: How Western Artists Have Viewed the Sexuality of Women (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1985), 62–3.

- ^ «Information about Johannes Vermeer’s «Woman with a Pearl Necklace»«. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

References[edit]

- Cairns, Douglas L (1996). «Hybris, Dishonour, and Thinking Big» (PDF). Journal of Hellenic Studies. 116: 1–32. doi:10.2307/631953. hdl:20.500.11820/d7c5e485-cef7-490a-b67d-1b1eb4a200ef. JSTOR 631953. S2CID 59361502.

- MacDowell, Douglas (1976). «Hybris in Athens». Greece and Rome. 23: 14–31. doi:10.1017/s0017383500018210. S2CID 163033169.

- Owen, David (2007) The Hubris Syndrome: Bush, Blair and the Intoxication of Power Politico’s, Methuen Publishing Ltd.

Further reading[edit]

- Jessica Tracy (2016). Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0544273177.

From Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Pride means having a feeling of being good and worthy. The adjective is proud.

The word pride can be used in a good sense as well as in a bad sense.

In a good sense it means having a feeling of self-respect. People can be satisfied with their achievements. They can be proud of something good that they have done. They can be proud of (or take pride in) their work. They might be proud of their son or daughter or husband or wife or anyone else who is close to them and who has done something good. People can be proud of their country (patriotism). The opposite would be to be ashamed of someone or something.

In a bad sense, pride can mean that someone has an exaggerated sense of feeling good. This might mean that someone has no respect for what other people do, only respect for what he or she does. Someone who is described as proud may be arrogant. The word is used in this sense in the saying: “Pride comes before a fall” or “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall.” Prov.16:18 (meaning that someone is so overconfident that he or she might soon have a disaster).

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- pryde (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English pride, from Old English prȳde, prȳte (“pride”) (compare Old Norse prýði (“bravery, pomp”)), derivative of Old English prūd (“proud”). More at proud. The verb derives from the noun, at least since the 12th century.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /pɹaɪd/, [ˈpɹ̥ʷaɪd]

- Rhymes: -aɪd

- Homophone: pried

Noun[edit]

pride (countable and uncountable, plural prides)

- The quality or state of being proud; an unreasonable overestimation of one’s own superiority in terms of talents, looks, wealth, importance etc., which manifests itself in lofty airs, distance, reserve and often contempt of others.

- (having a positive sense, often with of or in) A sense of one’s own worth, and scorn for what is beneath or unworthy of oneself; lofty self-respect; noble self-esteem; elevation of character; dignified bearing; rejection of shame

-

He took pride in his work.

-

He had pride of ownership in his department.

- 1766, Oliver Goldsmith, The Vicar of Wakefield, ch 3:

- My chief attention therefore was now to bring down the pride of my family to their circumstances; for I well knew that aspiring beggary is wretchedness itself.

- 1790-1793, William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

- The pride of the peacock is the glory of God.

-

- Proud or disdainful behavior or treatment; insolence or arrogance of demeanor; haughty bearing and conduct; insolent exultation.

- Synonyms: disdain, hubris

- 1912, G. K. Chesterton, Introduction to Aesop’s Fables

- Pride goeth before the fall.

- That of which one is proud; that which excites boasting or self-congratulation; the occasion or ground of self-esteem, or of arrogant and presumptuous confidence, as beauty, ornament, noble character, children, etc.

- Show; ostentation; glory.

-

c. 1603–1604 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Othello, the Moore of Venice”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act III, scene iii]:

-

Pride, pomp and circumstance of glorious war.

-

-

- Highest pitch; elevation reached; loftiness; prime; glory.

-

c. 1606 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Macbeth”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act II, scene iv]:

-

a falcon, towering in her pride of place

-

-

- Consciousness of power; fullness of animal spirits; mettle; wantonness.

- Lust; sexual desire; especially, excitement of sexual appetite in a female animal.

- (zoology, collective) A company of lions or other large felines.

-

A pride of lions often consists of a dominant male, his harem and their offspring, but young adult males ‘leave home’ to roam about as bachelors pride until able to seize/establish a family pride of their own.

-

- (zoology) The small European lamprey species Petromyzon branchialis.

- Alternative letter-case form of Pride (“festival for LGBT people”).

- For quotations using this term, see Citations:pride.

Synonyms[edit]

- (a sense of one’s own worth): dignity; See also Thesaurus:pride

- (proud or disdainful behavior): conceit, disdain; See also Thesaurus:arrogance

- (lust; sexual desire): See also Thesaurus:lust

- (lamprey species): prid, sandpiper

Derived terms[edit]

- Christmas pride

- gay pride

- in one’s pride

- London pride

- point of pride

- Pride

- pride and joy

- pride comes before a fall

- pride of authorship

- Pride of Erin

- pride of place

- pride parade

- prideful

- prider

- pridewear

- purse-pride

- self-pride

- straight pride

- swallow one’s pride

- take pride

[edit]

- proud

Translations[edit]

quality or state of being proud; inordinate self-esteem; an unreasonable conceit of one’s own superiority in talents, beauty, wealth, rank etc.

- Akkadian: 𒌨 m (bāštu [TEŠ2])

- Arabic: كِبْرِيَاء f (kibriyāʔ)

- Armenian: գոռոզություն (hy) (goṙozutʿyun)

- Asturian: arguyu m

- Avar: чӏухӏи (čʼuḥʳi)

- Azerbaijani: qürur, təkəbbür (az), məğrurluq

- Belarusian: го́нар m (hónar), пы́ха f (pýxa), гарды́ня f (hardýnja), фанабэ́рыя f (fanabéryja), ганары́стасць f (hanarýstascʹ)

- Bengali: নফসানিয়াত (bn) (nôfsaniẏat)

- Bulgarian: гордост (bg) f (gordost)

- Catalan: orgull (ca)

- Cherokee: please add this translation if you can

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 自負/自负 (zh) (zìfù), 自大 (zh) (zìdà), 妄自尊大 (zh) (wàngzì-zūndà)

- Czech: pýcha (cs) f

- Dutch: trots (nl), fierheid (nl), eergevoel (nl) n

- Esperanto: fiero (eo)

- Estonian: ülbus (et), kõrkus

- Finnish: ylpeys (fi)

- French: orgueil (fr) m, fierté (fr)

- Galician: orgullo (gl) m

- Georgian: სიამაყე (siamaq̇e), ამპარტავნება (amṗarṭavneba)

- German: Hochmut (de) m

- Greek: υπερηφάνεια (el) f (yperifáneia)

- Hebrew: גאווה גַּאֲוָה (he) f (gaavá)

- Hindi: आरोह (hi) m (āroh), ऊंचाई f (ūñcāī), ऐंठ (hi) f (aiṇṭh)

- Hungarian: büszkeség (hu)

- Icelandic: stolt n

- Irish: mórchúis f, anumhlaíocht f

- Italian: superbia (it) f, orgoglio (it)

- Japanese: 自慢 (ja) (じまん, jiman), 傲慢 (ja) (ごうまん, gōman)

- Korean: 자만 (ko) (jaman), 자부심 (ko) (jabusim), 교만 (ko) (gyoman)

- Latvian: lepnība f, lepnums m

- Macedonian: го́рдост f (górdost)

- Malayalam: അഭിമാനം (ml) (abhimānaṃ)

- Norwegian: stolthet (no) m

- Occitan: orguèlh m

- Old English: ofermettu f

- Oromo: boona

- Ossetian: сӕрыстыр (særystyr)

- Persian: غرور (fa) (ğorur)

- Plautdietsch: Huachmoot f

- Polish: pycha (pl) f, zarozumiałość (pl) f

- Portuguese: orgulho (pt) m

- Romanian: îngâmfare (ro) f, mândrie (ro) f, trufie (ro)

- Russian: горды́ня (ru) f (gordýnja), спесь (ru) f (spesʹ), зано́счивость (ru) f (zanósčivostʹ), высокоме́рие (ru) n (vysokomérije), чва́нство (ru) n (čvánstvo), го́нор (ru) m (gónor)

- Scottish Gaelic: uaill f

- Slovak: pýcha f

- Slovene: ponòs (sl) m, nadutost f

- Southern Sami: tjievlies-voete

- Spanish: orgullo (es) m

- Swedish: stolthet (sv) c

- Tagalog: karangalan

- Turkish: kibir (tr), gurur (tr)

- Tuvan: чоргаарал (çorgaaral)

- Ukrainian: горди́ня f (hordýnja), го́нор m (hónor), пиха́ f (pyxá), чва́нство (uk) n (čvánstvo), фуду́лія f (fudúlija)

- Walloon: firté (wa) f

- Welsh: balchder m

- Yiddish: גאווה (gayve)

sense of one’s own worth, and abhorrence of what is beneath or unworthy of one

- Arabic: فَخْر m (faḵr)

- Armenian: հպարտություն (hy) (hpartutʿyun)

- Azerbaijani: qürur, fəxr, iftixar

- Belarusian: го́рдасць f (hórdascʹ)

- Bulgarian: го́рдост (bg) f (górdost)

- Catalan: orgull (ca) m

- Cherokee: ᎠᏢᏉᏛ (atlvquodv)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 驕傲/骄傲 (zh) (jiāo’ào), 自尊 (zh) (zìzūn)

- Czech: hrdost f

- Danish: stolthed c

- Dutch: trots (nl), eigendunk (nl), zelfvoldaanheid (nl)

- Esperanto: sinamo

- Estonian: ülbus (et)

- Faroese: erni n, stoltleiki m

- Finnish: ylpeys (fi)

- French: fierté (fr) f, orgueil (fr) m

- Galician: orgullo (gl) m

- German: Stolz (de) m

- Greek: αξιοπρέπεια (el) f (axioprépeia)

- Hebrew: גאווה גַּאֲוָה (he) f (gaavá)

- Hindi: गर्व (hi) m (garv)

- Hungarian: önbecsülés (hu), önérzet (hu)

- Icelandic: stolt n

- Indonesian: angkuh (id), sombong (id)

- Irish: uaill f, mórtas m

- Italian: orgoglio (it) m

- Japanese: 誇り (ja) (ほこり, hokori), プライド (ja) (puraido)

- Khmer: មោទនភាព (moutean pʰiep)

- Korean: 자랑 (ko) (jarang)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: شانازی (ckb) (şanazî)

- Latin: superbia f

- Latvian: lepnums m

- Macedonian: го́рдост f (górdost)

- Malayalam: അഭിമാനം (ml) (abhimānaṃ)

- Maori: whakahī

- Norwegian: stolthet (no) m

- Occitan: orguèlh m

- Old English: ofermettu f

- Polish: duma (pl)

- Portuguese: orgulho (pt) m

- Romanian: orgoliu (ro) n

- Russian: го́рдость (ru) f (górdostʹ)

- Scottish Gaelic: uaill f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: гордост f, понос m

- Roman: gordost (sh) f, ponos (sh) m

- Slovak: hrdosť f

- Slovene: ponos (sl) m

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: gjardosć f

- Spanish: orgullo (es) m

- Swedish: stolthet (sv) c

- Turkish: gurur (tr)

- Ukrainian: го́рдість f (hórdistʹ)

- Yiddish: שטאָלץ (shtolts)

proud or disdainful behavior or treatment; insolence or arrogance of demeanor; haughty bearing and conduct

- Bulgarian: надменност (bg) f (nadmennost), високомерие (bg) n (visokomerie)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 傲慢 (zh) (àomàn)

- Chuukese: namanam tekia

- Dutch: trots (nl), fierheid (nl), hoogmoed (nl), eigenwaan (nl), kapsones (nl) m

- Estonian: ülbus (et)

- Finnish: ylpeys (fi), kopeus (fi)

- French: fierté (fr) f, orgueil (fr) m

- Galician: soberbia (gl) f, fachenda (gl) f

- German: Hochmut (de) m, Trotz (de) m, Dünkel (de) m

- Greek: υπεροψία (el) f (yperopsía), περιφρόνηση (el) f (perifrónisi), εγωισμός (el) (egoïsmós), οίηση (el) f (oíisi)

- Hungarian: gőg (hu), dölyf (hu)

- Irish: borrachas m, uaill f, mórtas m

- Japanese: 傲慢 (ja) (ごうまん, gōman)

- Latvian: lepnība f, iedomība f

- Macedonian: горде́ливост f (gordélivost), на́дменост f (nádmenost)

- Norwegian: stolthet (no) m

- Portuguese: soberba (pt) f, nariz empinado m

- Russian: горды́ня (ru) f (gordýnja), спесь (ru) f (spesʹ), зано́счивость (ru) f (zanósčivostʹ), высокоме́рие (ru) n (vysokomérije), чва́нство (ru) n (čvánstvo)

- Scottish Gaelic: uaill f

- Spanish: soberbia (es) f

- Swedish: stolthet (sv) c

- Tocharian B: amāṃ

- Turkish: kibir (tr)

show; ostentation; glory

- Bulgarian: показност f (pokaznost)

- Finnish: ylvästely (fi)

- Greek: αυταρέσκεια (el) f (aftaréskeia)

- Macedonian: го́рдост f (górdost)

- Russian: го́рдость (ru) f (górdostʹ)

- Scottish Gaelic: uaill f

- Swedish: prål (sv), skrytsamhet (sv), vräkighet

highest pitch; elevation reached; loftiness; prime; glory

- Dutch: (please verify) bloei (nl), (please verify) bloeitijd (nl), (please verify) fleur (nl), (please verify) hoogtepunt (nl) n, (please verify) piek (nl), (please verify) (volle) glorie

- Finnish: huippu (fi)

- Hungarian: csúcs (hu), csúcspont (hu), dele (hu), virágja

- Russian: расцве́т (ru) m (rascvét), разга́р (ru) m (razgár)

- Swedish: höjdpunkt (sv), topp (sv)

consciousness of power; fullness of animal spirits; mettle; wantonness

lust; sexual desire; especially, an excitement of sexual appetite in a female beast

company of lions

- Bulgarian: група лъвове (grupa lǎvove)

- Czech: smečka (cs) f

- Dutch: troep (nl)

- Esperanto: leonaro

- Finnish: lauma (fi)

- French: troupeau (fr) m

- German: Rudel (de)

- Greek: αγέλη (el) f (agéli)

- Hebrew: שַׁחַץ (he) m (sháẖatz)

- Hungarian: falka (hu)

- Macedonian: глу́тница f (glútnica), ста́до n (stádo)

- Norwegian: flokk (no) m

- Polish: stado (pl) n

- Portuguese: alcateia (pt) f

- Russian: прайд (ru) m (prajd)

- Serbo-Croatian: čopor (sh) m

- Spanish: manada (es) f

- Swedish: flock (sv) c

small European lamprey (Petromyzon branchialis)

Translations to be checked

- Cebuano: (please verify) garbo

- Italian: (please verify) orgoglio (it) m

- Marathi: (please verify) गर्व (mr) (garva)

- Scottish Gaelic: (please verify) uaill f, (please verify) pròis f, (please verify) àrdan m, (please verify) uabhar m

- Serbo-Croatian: (please verify) ponos (sh) m, (please verify) gordost (sh) f, (please verify) oholost (sh) f

- Slovene: (1,2) (please verify) ponos (sl) m

- Spanish: (please verify) orgullo (es) m

See also[edit]

- clowder, company of small felines

Verb[edit]

pride (third-person singular simple present prides, present participle priding, simple past and past participle prided)

- (reflexive) To take or experience pride in something; to be proud of it.

-

I pride myself on being a good judge of character.

- 1820, Washington Irving, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

- Ichabod prided himself upon his dancing as much as upon his vocal powers. Not a limb, not a fibre about him was idle; and to have seen his loosely hung frame in full motion and clattering about the room you would have thought Saint Vitus himself, that blessed patron of the dance, was figuring before you in person.

-

2021 December 29, Paul Stephen, “Rail’s accident investigators”, in RAIL, number 947, page 32:

-

RAIB prides itself on being able to send any of its inspectors to site with sufficient investigative skills and technical knowledge to gather evidence for any type of accident.

-

-

Derived terms[edit]

- prided

- priding

Translations[edit]

take or experience pride in something

- Bulgarian: гордея се (gordeja se)

- Dutch: prat gaan (op), trots zijn (op)

- Esperanto: fieri

- German: stolz sein auf

- Greek: υπερηφανεύομαι (el) (yperifanévomai), καμαρώνω (el) (kamaróno)

- Italian: essere orgoglioso

- Macedonian: се го́рдее (se górdee)

- Russian: горди́ться (ru) impf (gordítʹsja)

- Spanish: ser orgulloso de, enorgullecerse (es)

- Swedish: vara stolt

- Turkish: gurur duymak (tr), övünç duymak (tr)

- Ukrainian: горди́тися impf (hordýtysja)

References[edit]

- Douglas Harper (2001–2023), “pride”, in Online Etymology Dictionary.

Part or all of this entry has been imported from the 1913 edition of Webster’s Dictionary, which is now free of copyright and hence in the public domain. The imported definitions may be significantly out of date, and any more recent senses may be completely missing.

(See the entry for pride in Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary, G. & C. Merriam, 1913)

Anagrams[edit]

- pried, re-dip, redip, riped

Between the sin of Pride and the joy of LGBTQ Pride parades, you might be a little confused about what the word pride actually means. Not to worry, though; we’re here to help!

In this post, we’re exploring the term pride to uncover its definition, origin, synonyms, antonyms, and more. So if you’ve ever wondered about pride — keep reading. Here’s our complete guide on pride.

What Is the Definition of Pride?

To kick off our journey toward understanding the word pride, let’s start by reviewing a few definitions provided by three trusted English dictionaries:

- According to the Britannica Dictionary, pride is a feeling in which respect yourself and deserve to be respected by other people.

- The Oxford English Dictionary defines pride as consciousness of one’s own dignity.

- The Collins Dictionary says if you pride yourself on a quality or skill that you have, you are very proud of it.

After reviewing these definitions, we can conclude that pride is the quality or state of being proud. In other words, it’s reasonable self-respect.

While you may use our word of the day when referring to national pride, the term pride can also be used to refer to a number of subjects, such as:

- The Pride Parade — an outdoor event that celebrates lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) social and self-acceptance, legal rights, achievements, and more.

- Pride And Prejudice — a fantastic novel written by Jane Austen.

- Pride, from the Seven Deadly Sins — considered the original and more serious of the cardinal sins.

- A group of lions is collectively known as a Pride

What Is the Origin of Pride?

According to the Macmillan Dictionary, the noun pride made its first debut in the English language at the beginning of the 14th century, derived from the late Old English pryto. This came from the adjective prūt or prūd meaning “proud.”

What Are the Idioms, Synonyms, and Antonyms of Pride?

Below you will find a list of the various idioms, antonyms, and symptoms of our word of the day, pride, all of which are provided to you today by Power Thesaurus and Collins English Thesaurus.

Idioms and Synonyms:

- Swallow your pride

- Ego

- Self-respect

- Pomposity

- Excessive self-esteem

- Pride oneself on

- Dignity

- Egotism

- Vainglory

- Snobbery

- Belief in one’s worth

- Honor

- Self-esteem

- Vanity

- Pride of place

- Pride in one’s abilities

- Hubris

- Inordinate self-esteem

Antonyms:

- Source of embarrassment

- Ashamedness

- self-reproach

- Humble

- Abashment

- Self-effacement

- Humiliation

- Bad conscience

- Jealous

- Modesty

- down-to-earthiness

- Humility

- self-reproof

- Lack of vanity

Additionally, we have included a few of the commonly related word partners for pride provided by Collins English Dictionary:

- Patriotic pride

- National pride

- Immense pride

- Civic pride

- Pride month

- Great pride

- Collective pride

- Dented pride

- Hurt pride

- Feel pride

- Fierce pride

How Can You Use Pride in a Sentence?

Now that you understand what the word pride means, let’s take a look at a few example sentences, shall we?

Jane Austen wrote one of my favorite novels to date, Pride and Prejudice. How can you NOT know who she is?

I wore my rainbow socks, rainbow t-shirt, and rainbow skirt to the Pride Parade today. If you ask me, I think I still could have used a bit more color.

She has a powerful sense of pride that simply can’t be matched.

I take great pride in my work — don’t you?

Did you know pride is the original deadly sin?

Tom’s feeling of pride quickly fizzled after realizing all of his hard work was for nothing.

Apparantly, the word pride is a derivative of the Old English prūd, which simply means “proud.”

To indulge in a feeling of pleasure is simply pride.

My teacher told me that pride is born out of overconfidence and that I should be proud of all my accomplishments from over the year.

Despite being small, Tammy’s little brother took great pride in sticking up for his sister when she was getting bullied at the bus stop.

What Are Translations of Pride?

Wondering how to say pride in a different language? We have your back! Here are the many various translations of the word pride:

Pride as a noun:

- Swedish — stolthet

- Thai — ความภาคภูมิใจ

- Turkish — gurur

- European Portuguese — orgulho

- Romanian — mândrie

- Japanese — 誇り

- Finnish — ylpeys

- American English — pride

- Arabic — فَخْر

- Brazilian Portuguese — orgulho

- Chinese — 骄傲

- Croatian — ponos

- Czech — pýcha

- Danish — stolthed

- Dutch — trots

- European Spanish — orgullo

- French — fierté

- German — Stolz

- Greek — περηφάνεια

- Italian — orgoglio

- Korean — 긍지

- Norwegian — stolthet

- Polish — duma

- Russian — гордость

- Spanish — orgullo

- Ukrainian — гордість

- Vietnamese — sự tự hào

Pride as a verb:

- European Spanish — enorgullecerse

- French — enorgueillir

- American English — pride

- Italian — essere orgoglioso

- Japanese — 誇りにする

- European Portuguese — orgulhar-se

- Spanish— enorgullecerse

- Korean — ~을 자랑스러워하다

- Brazilian Portuguese — orgulhar-se

- Chinese — 以…而自豪

- German — sich rühmen

Conclusion

To come to the point, the noun pride describes a feeling of self-respect and happiness, most commonly after achieving something. Be sure not to forget that Pride can also be attached to some negative connotations as well — hence why it’s the name of the original cardinal sin.

For more interesting words and their definitions, check out our website and start learning today!

Sources:

- Pride definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary

- Pride synonyms: 791 Words and Phrases for Pride | Power Thesaurus

- Pride | Macmillan Dictionary Blog

Kevin Miller is a growth marketer with an extensive background in Search Engine Optimization, paid acquisition and email marketing. He is also an online editor and writer based out of Los Angeles, CA. He studied at Georgetown University, worked at Google and became infatuated with English Grammar and for years has been diving into the language, demystifying the do’s and don’ts for all who share the same passion! He can be found online here.