converters or dtype won’t always help. Especially for date/time and duration (ideally a mix of both…), post-processing is necessary. In such cases, reading the Excel file’s content to a built-in type and create the DataFrame from that can be an option.

Here’s an example file. The «duration» column contains duration values in HH:MM:SS and invalid values «-«.

If the hour is less than 24, Excel formats the entry to a time, otherwise a duration. We want dtype timedelta for the whole column in the DataFrame. But pandas messes up the import:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel("path-to-file")

df.duration

# 0 12:30:00

# 1 1900-01-01 00:30:00

# 2 -

# 3 1900-01-01 23:55:01

# Name: duration, dtype: object

[type(i) for i in df.duration]

# [datetime.time, datetime.datetime, str, datetime.datetime]

Now we have datetime.datetime and datetime.time objects, and it’s difficult to get back duration (timedelta)! You could do it directly with a converter, but that does not make it less difficult.

Here, I found it to be actually easier to use the excel loader engine directly:

from openpyxl import load_workbook

wb = load_workbook('path-to-file')

sheet = wb['Tests'] # adjust sheet name, this is for the demo file

data = list(sheet.values) # a list of tuples, one tuple for each row

df = pd.DataFrame(data[1:], columns=data[0]) # first tuple is column names

df['duration']

# 0 12:30:00

# 1 1 day, 0:30:00

# 2 -

# 3 1 day, 23:55:01

# Name: duration, dtype: object

[type(i) for i in df['duration']]

# [datetime.time, datetime.timedelta, str, datetime.timedelta]

So now we already have some timedelta objects! The conversion of the others to timedelta can be done as simple as

df['duration'] = pd.to_timedelta(df.duration.astype(str), errors='coerce')

df['duration']

# 0 0 days 12:30:00

# 1 1 days 00:30:00

# 2 NaT

# 3 1 days 23:55:01

# Name: duration, dtype: timedelta64[ns]

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to use Python and Pandas to read Excel files using the Pandas read_excel function. Excel files are everywhere – and while they may not be the ideal data type for many data scientists, knowing how to work with them is an essential skill.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll have learned:

- How to use the Pandas read_excel function to read an Excel file

- How to read specify an Excel sheet name to read into Pandas

- How to read multiple Excel sheets or files

- How to certain columns from an Excel file in Pandas

- How to skip rows when reading Excel files in Pandas

- And more

Let’s get started!

The Quick Answer: Use Pandas read_excel to Read Excel Files

To read Excel files in Python’s Pandas, use the read_excel() function. You can specify the path to the file and a sheet name to read, as shown below:

# Reading an Excel File in Pandas

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel('/Users/datagy/Desktop/Sales.xlsx')

# With a Sheet Name

df = pd.read_excel(

io='/Users/datagy/Desktop/Sales.xlsx'

sheet_name ='North'

)In the following sections of this tutorial, you’ll learn more about the Pandas read_excel() function to better understand how to customize reading Excel files.

Understanding the Pandas read_excel Function

The Pandas read_excel() function has a ton of different parameters. In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to use the main parameters available to you that provide incredible flexibility in terms of how you read Excel files in Pandas.

| Parameter | Description | Available Option |

|---|---|---|

io= |

The string path to the workbook. | URL to file, path to file, etc. |

sheet_name= |

The name of the sheet to read. Will default to the first sheet in the workbook (position 0). | Can read either strings (for the sheet name), integers (for position), or lists (for multiple sheets) |

usecols= |

The columns to read, if not all columns are to be read | Can be strings of columns, Excel-style columns (“A:C”), or integers representing positions columns |

dtype= |

The datatypes to use for each column | Dictionary with columns as keys and data types as values |

skiprows= |

The number of rows to skip from the top | Integer value representing the number of rows to skip |

nrows= |

The number of rows to parse | Integer value representing the number of rows to read |

.read_excel() functionThe table above highlights some of the key parameters available in the Pandas .read_excel() function. The full list can be found in the official documentation. In the following sections, you’ll learn how to use the parameters shown above to read Excel files in different ways using Python and Pandas.

As shown above, the easiest way to read an Excel file using Pandas is by simply passing in the filepath to the Excel file. The io= parameter is the first parameter, so you can simply pass in the string to the file.

The parameter accepts both a path to a file, an HTTP path, an FTP path or more. Let’s see what happens when we read in an Excel file hosted on my Github page.

# Reading an Excel file in Pandas

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel('https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx')

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 191

# 1 2022-04-02 B 727

# 2 2022-04-03 A 782

# 3 2022-04-04 B 561

# 4 2022-04-05 A 969If you’ve downloaded the file and taken a look at it, you’ll notice that the file has three sheets? So, how does Pandas know which sheet to load? By default, Pandas will use the first sheet (positionally), unless otherwise specified.

In the following section, you’ll learn how to specify which sheet you want to load into a DataFrame.

How to Specify Excel Sheet Names in Pandas read_excel

As shown in the previous section, you learned that when no sheet is specified, Pandas will load the first sheet in an Excel workbook. In the workbook provided, there are three sheets in the following structure:

Sales.xlsx

|---East

|---West

|---NorthBecause of this, we know that the data from the sheet “East” was loaded. If we wanted to load the data from the sheet “West”, we can use the sheet_name= parameter to specify which sheet we want to load.

The parameter accepts both a string as well as an integer. If we were to pass in a string, we can specify the sheet name that we want to load.

Let’s take a look at how we can specify the sheet name for 'West':

# Specifying an Excel Sheet to Load by Name

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name='West')

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 504

# 1 2022-04-02 B 361

# 2 2022-04-03 A 694

# 3 2022-04-04 B 702

# 4 2022-04-05 A 255Similarly, we can load a sheet name by its position. By default, Pandas will use the position of 0, which will load the first sheet. Say we wanted to repeat our earlier example and load the data from the sheet named 'West', we would need to know where the sheet is located.

Because we know the sheet is the second sheet, we can pass in the 1st index:

# Specifying an Excel Sheet to Load by Position

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name=1)

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 504

# 1 2022-04-02 B 361

# 2 2022-04-03 A 694

# 3 2022-04-04 B 702

# 4 2022-04-05 A 255We can see that both of these methods returned the same sheet’s data. In the following section, you’ll learn how to specify which columns to load when using the Pandas read_excel function.

How to Specify Columns Names in Pandas read_excel

There may be many times when you don’t want to load every column in an Excel file. This may be because the file has too many columns or has different columns for different worksheets.

In order to do this, we can use the usecols= parameter. It’s a very flexible parameter that lets you specify:

- A list of column names,

- A string of Excel column ranges,

- A list of integers specifying the column indices to load

Most commonly, you’ll encounter people using a list of column names to read in. Each of these columns are comma separated strings, contained in a list.

Let’s load our DataFrame from the example above, only this time only loading the 'Customer' and 'Sales' columns:

# Specifying Columns to Load by Name

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

usecols=['Customer', 'Sales'])

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Customer Sales

# 0 A 191

# 1 B 727

# 2 A 782

# 3 B 561

# 4 A 969We can see that by passing in the list of strings representing the columns, we were able to parse those columns only.

If we wanted to use Excel changes, we could also specify columns 'B:C'. Let’s see what this looks like below:

# Specifying Columns to Load by Excel Range

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

usecols='B:C')

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Customer Sales

# 0 A 191

# 1 B 727

# 2 A 782

# 3 B 561

# 4 A 969Finally, we can also pass in a list of integers that represent the positions of the columns we wanted to load. Because the columns are the second and third columns, we would load a list of integers as shown below:

# Specifying Columns to Load by Their Position

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

usecols=[1,2])

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Customer Sales

# 0 A 191

# 1 B 727

# 2 A 782

# 3 B 561

# 4 A 969In the following section, you’ll learn how to specify data types when reading Excel files.

How to Specify Data Types in Pandas read_excel

Pandas makes it easy to specify the data type of different columns when reading an Excel file. This serves three main purposes:

- Preventing data from being read incorrectly

- Speeding up the read operation

- Saving memory

You can pass in a dictionary where the keys are the columns and the values are the data types. This ensures that data are ready correctly. Let’s see how we can specify the data types for our columns.

# Specifying Data Types for Columns When Reading Excel Files

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

dtype={'date':'datetime64', 'Customer': 'object', 'Sales':'int'})

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Customer Sales

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 191

# 1 2022-04-02 B 727

# 2 2022-04-03 A 782

# 3 2022-04-04 B 561

# 4 2022-04-05 A 969It’s important to note that you don’t need to pass in all the columns for this to work. In the next section, you’ll learn how to skip rows when reading Excel files.

How to Skip Rows When Reading Excel Files in Pandas

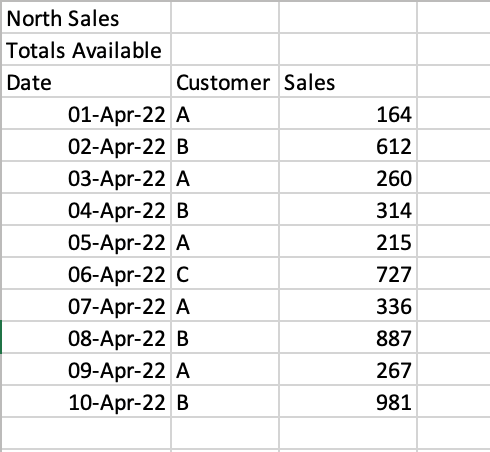

In some cases, you’ll encounter files where there are formatted title rows in your Excel file, as shown below:

If we were to read the sheet 'North', we would get the following returned:

# Reading a poorly formatted Excel file

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name='North')

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# North Sales Unnamed: 1 Unnamed: 2

# 0 Totals Available NaN NaN

# 1 Date Customer Sales

# 2 2022-04-01 00:00:00 A 164

# 3 2022-04-02 00:00:00 B 612

# 4 2022-04-03 00:00:00 A 260Pandas makes it easy to skip a certain number of rows when reading an Excel file. This can be done using the skiprows= parameter. We can see that we need to skip two rows, so we can simply pass in the value 2, as shown below:

# Reading a Poorly Formatted File Correctly

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name='North',

skiprows=2)

print(df.head())

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 164

# 1 2022-04-02 B 612

# 2 2022-04-03 A 260

# 3 2022-04-04 B 314

# 4 2022-04-05 A 215This read the file much more accurately! It can be a lifesaver when working with poorly formatted files. In the next section, you’ll learn how to read multiple sheets in an Excel file in Pandas.

How to Read Multiple Sheets in an Excel File in Pandas

Pandas makes it very easy to read multiple sheets at the same time. This can be done using the sheet_name= parameter. In our earlier examples, we passed in only a single string to read a single sheet. However, you can also pass in a list of sheets to read multiple sheets at once.

Let’s see how we can read our first two sheets:

# Reading Multiple Excel Sheets at Once in Pandas

import pandas as pd

dfs = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name=['East', 'West'])

print(type(dfs))

# Returns: <class 'dict'>In the example above, we passed in a list of sheets to read. When we used the type() function to check the type of the returned value, we saw that a dictionary was returned.

Each of the sheets is a key of the dictionary with the DataFrame being the corresponding key’s value. Let’s see how we can access the 'West' DataFrame:

# Reading Multiple Excel Sheets in Pandas

import pandas as pd

dfs = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name=['East', 'West'])

print(dfs.get('West').head())

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 504

# 1 2022-04-02 B 361

# 2 2022-04-03 A 694

# 3 2022-04-04 B 702

# 4 2022-04-05 A 255You can also read all of the sheets at once by specifying None for the value of sheet_name=. Similarly, this returns a dictionary of all sheets:

# Reading Multiple Excel Sheets in Pandas

import pandas as pd

dfs = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

sheet_name=None)In the next section, you’ll learn how to read multiple Excel files in Pandas.

How to Read Only n Lines When Reading Excel Files in Pandas

When working with very large Excel files, it can be helpful to only sample a small subset of the data first. This allows you to quickly load the file to better be able to explore the different columns and data types.

This can be done using the nrows= parameter, which accepts an integer value of the number of rows you want to read into your DataFrame. Let’s see how we can read the first five rows of the Excel sheet:

# Reading n Number of Rows of an Excel Sheet

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_excel(

io='https://github.com/datagy/mediumdata/raw/master/Sales.xlsx',

nrows=5)

print(df)

# Returns:

# Date Customer Sales

# 0 2022-04-01 A 191

# 1 2022-04-02 B 727

# 2 2022-04-03 A 782

# 3 2022-04-04 B 561

# 4 2022-04-05 A 969Conclusion

In this tutorial, you learned how to use Python and Pandas to read Excel files into a DataFrame using the .read_excel() function. You learned how to use the function to read an Excel, specify sheet names, read only particular columns, and specify data types. You then learned how skip rows, read only a set number of rows, and read multiple sheets.

Additional Resources

To learn more about related topics, check out the tutorials below:

- Pandas Dataframe to CSV File – Export Using .to_csv()

- Combine Data in Pandas with merge, join, and concat

- Introduction to Pandas for Data Science

- Summarizing and Analyzing a Pandas DataFrame

You can use the following basic syntax to specify the dtype of each column in a DataFrame when importing an Excel file into pandas:

df = pd.read_excel('my_data.xlsx', dtype = {'col1': str, 'col2': float, 'col3': int})

The dtype argument specifies the data type that each column should have when importing the Excel file into a pandas DataFrame.

The following example shows how to use this syntax in practice.

Suppose we have the following Excel file called player_data.xlsx:

If we import the Excel file using the read_excel() function, pandas will attempt to identify the data type for each column automatically:

import pandas as pd #import Excel file df = pd.read_excel('player_data.xlsx') #view resulting DataFrame print(df) team points rebounds assists 0 A 24 8 5 1 B 20 12 3 2 C 15 4 7 3 D 19 4 8 4 E 32 6 8 5 F 13 7 9 #view data type of each column print(df.dtypes) team object points int64 rebounds int64 assists int64 dtype: object

From the output we can see that the columns in the DataFrame have the following data types:

- team: object

- points: int64

- rebounds: int64

- assists: int64

However, we can use the dtype argument within the read_excel() function to specify the data types that each column should have:

import pandas as pd #import Excel file and specify dtypes of columns df = pd.read_excel('player_data.xlsx', dtype = {'team': str, 'points': float, 'rebounds': int, 'assists': float}) #view resulting DataFrame print(df) team points rebounds assists 0 A 24.0 8 5.0 1 B 20.0 12 3.0 2 C 15.0 4 7.0 3 D 19.0 4 8.0 4 E 32.0 6 8.0 5 F 13.0 7 9.0 #view data type of each column print(df.dtypes) team object points float64 rebounds int32 assists float64 dtype: object

From the output we can see that the columns in the DataFrame have the following data types:

- team: object

- points: float64

- rebounds: int32

- assists: float64

These data types match the ones that we specified using the dtype argument.

Note that in this example, we specified the dtype for each column in the DataFrame.

However, you can choose to specify the dtype for only specific columns and let pandas infer the dtype for the remaining columns.

Note: You can find the complete documentation for the pandas read_excel() function here.

Additional Resources

The following tutorials explain how to perform other common tasks in pandas:

Pandas: How to Skip Rows when Reading Excel File

Pandas: How to Combine Multiple Excel Sheets

Pandas: How to Write DataFrames to Multiple Excel Sheets

pandas.read_excel() function is used to read excel sheet with extension xlsx into pandas DataFrame. By reading a single sheet it returns a pandas DataFrame object, but reading two sheets it returns a Dict of DataFrame.

pandas Read Excel Key Points

- This supports to read files with extension xls, xlsx, xlsm, xlsb, odf, ods and odt

- Can load excel files stored in a local filesystem or from an URL.

- For URL, it supports http, ftp, s3, and file.

- Also supports reading from a single sheet or a list of sheets.

- When reading a two sheets, it returns a Dict of DataFrame.

Table of contents –

- Read Excel Sheet into DataFrame

- Read by Ignoring Column Names

- Set Column from Excel as Index

- Read Excel by Sheet Name

- Read Two Sheets

- Skip Columns From Excel

- Skip Rows From Excel

- Other Important Params

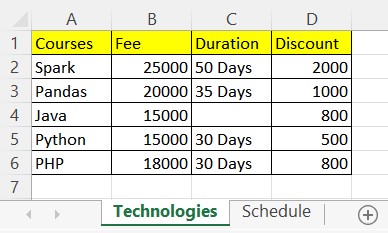

I have an excel file with two sheets named Technologies and Schedule, I will be using this to demonstrate how to read into pandas DataFrame.

Notice that on our excel file the top row contains the header of the table which can be used as column names on DataFrame.

1. pandas Read Excel Sheet

Use pandas.read_excel() function to read excel sheet into pandas DataFrame, by default it loads the first sheet from the excel file and parses the first row as a DataFrame column name. Excel file has an extension .xlsx. This function also supports several extensions xls, xlsx, xlsm, xlsb, odf, ods and odt .

Following are some of the features supported by read_excel() with optional param.

- Reading excel file from URL, S3, and from local file ad supports several extensions.

- Ignoreing the column names and provides an option to set column names.

- Setting column as Index

- Considering multiple values as NaN

- Decimal points to use for numbers

- Data types for each column

- Skipping rows and columns

I will cover how to use some of these optional params with examples, first let’s see how to read an excel sheet & create a DataFrame without any params.

import pandas as pd

# Read Excel file

df = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx')

print(df)

# Outputs

# Courses Fee Duration Discount

#0 Spark 25000 50 Days 2000

#1 Pandas 20000 35 Days 1000

#2 Java 15000 NaN 800

#3 Python 15000 30 Days 500

#4 PHP 18000 30 Days 800

Related: pandas Write to Excel Sheet

By default, it considers the first row from excel as a header and used it as DataFrame column names. In case you wanted to consider the first row from excel as a data record use header=None param and use names param to specify the column names. Not specifying names result in column names with numerical numbers.

# Read excel by considering first row as data

columns = ['courses','course_fee','course_duration','course_discount']

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

header=None, names = columns)

print(df2)

# Outputs

#0 courses course_fee Duration Discount

#1 Spark 25000 50 Days 2000

#2 Pandas 20000 35 Days 1000

#3 Java 15000 NaN 800

#4 Python 15000 30 Days 500

#5 PHP 18000 30 Days 800

3. Set Column from Excel as Index

If you notice, the DataFrame was created with the default index, if you wanted to set the column name as index use index_col param. This param takes values {int, list of int, default None}. If a list is passed with header positions, it creates a MultiIndex.

By default, it is set to None meaning not column is set as an index.

# Read excel by setting column as index

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

index_col=0)

print(df2)

# Outputs

# Fee Duration Discount

#Courses

#Spark 25000 50 Days 2000

#Pandas 20000 35 Days 1000

#Java 15000 NaN 800

#Python 15000 30 Days 500

#PHP 18000 30 Days 800

4. Read Excel by Sheet Name

As I said in the above section by default pandas read the first sheet from the excel file and provide a sheet_name param to read a specific sheet by name. This param takes {str, int, list, or None} as values. This is also used to load a sheet by position.

By default, it is set to 0 meaning load the first sheet.

# Read specific excel sheet

df = pd.read_excel('records.xlsx', sheet_name='Sheet1')

print(df)

5. Read Two Sheets

sheet_name param also takes a list of sheet names as values that can be used to read two sheets into pandas DataFrame. Not that while reading two sheets it returns a Dict of DataFrame. The key in Dict is a sheet name and the value would be DataFrame.

Use None to load all sheets from excel and returns a Dict of Dictionary.

# Read Multiple sheets

dict_df = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

sheet_name=['Technologies','Schedule'])

# Get DataFrame from Dict

technologies_df = dict_df .get('Technologies')

schedule_df = dict_df.get('Schedule')

# Print DataFrame's

print(technologies_df)

print(schedule_df)

I will leave this to you to execute and validate the output.

6. Skip Columns From Excel Sheet

Sometimes while reading an excel sheet into pandas DataFrame you may need to skip columns, you can do this by using usecols param. This takes values {int, str, list-like, or callable default None}. To specify the list of column names or positions use a list of strings or a list of int.

By default it is set to None meaning load all columns

# Read excel by skipping columns

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

usecols=['Courses', 'Duration'])

print(df2)

# Outputs

# Courses Duration

#0 Spark 50 Days

#1 Pandas 35 Days

#2 Java NaN

#3 Python 30 Days

#4 PHP 30 Days

Alternatively, you can also write it by column position.

# Skip columns with list of values

df = pd.read_excel('records.xlsx', usecols=[0,2])

print(df)

Also supports a range of columns as value. For example, value ‘B:D’ means parsing B, C, and D columns.

# Skip columns by range

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

usecols='B:D')

print(df2)

Fee Duration Discount

0 25000 50 Days 2000

1 20000 35 Days 1000

2 15000 NaN 800

3 15000 30 Days 500

4 18000 30 Days 800

7. Skip Rows from Excel Sheet

Use skiprows param to skip rows from the excel file, this param takes values {list-like, int, or callable, optional}. With this, you can skip the first few rows, selected rows, and range of rows. The below example skips the first 3 rows and considers the 4th row from excel as the header.

# Read excel file by skipping rows

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

skiprows=2)

print(df2)

Pandas 20000 35 Days 1000

0 Java 15000 NaN 800

1 Python 15000 30 Days 500

2 PHP 18000 30 Days 800

Use header=None to consider the 4th row as data. you can also use a list of rows to skip.

# Using skiprows to skip rows

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

skiprows=[1,3])

print(df2)

Courses Fee Duration Discount

0 Pandas 20000 35 Days 1000

1 Python 15000 30 Days 500

2 PHP 18000 30 Days 800

By using a lambda expression.

# Using skiprows with lambda

df2 = pd.read_excel('c:/apps/courses_schedule.xlsx',

skiprows=lambda x: x in [1,3])

print(df2)

8. Other Important Params

- dtype – Dict with column name an type.

- nrows – How many rows to parse.

- na_values – Additional strings to recognize as NA/NaN.

- keep_default_na – Whether or not to include the default NaN values when parsing the data.

- na_filter – Filters missing values.

- parse_dates – Specify the column index you wanted to parse as dates

- thousands – Thousands separator for parsing string columns to numeric.

- skipfooter – Specify how to rows you wanted to skip from the footer.

- mangle_dupe_cols – Duplicate columns will be specified as ‘X’, ‘X.1’, …’X.N’,

For complete params and description, refer to pandas documentation.

Conclusion

In this article, you have learned how to read an Excel sheet and covert it into DataFrame by ignoring header, skipping rows, skipping columns, specifying column names, and many more.

Happy Learning !!

Related Articles

- pandas ExcelWriter Usage with Examples

- pandas write CSV file

- Pandas Read SQL Query or Table with Examples

- Pandas Read TSV with Examples

- Pandas Read Text with Examples

- Pandas read_csv() with Examples

- Pandas Read JSON File with Examples

- How to Read CSV from String in Pandas

- Pandas Write to Excel with Examples

References

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/deployoffice/compat/office-file-format-reference

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Microsoft_Office_filename_extensions

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Reading and Writing Files With Pandas

pandas is a powerful and flexible Python package that allows you to work with labeled and time series data. It also provides statistics methods, enables plotting, and more. One crucial feature of pandas is its ability to write and read Excel, CSV, and many other types of files. Functions like the pandas read_csv() method enable you to work with files effectively. You can use them to save the data and labels from pandas objects to a file and load them later as pandas Series or DataFrame instances.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn:

- What the pandas IO tools API is

- How to read and write data to and from files

- How to work with various file formats

- How to work with big data efficiently

Let’s start reading and writing files!

Installing pandas

The code in this tutorial is executed with CPython 3.7.4 and pandas 0.25.1. It would be beneficial to make sure you have the latest versions of Python and pandas on your machine. You might want to create a new virtual environment and install the dependencies for this tutorial.

First, you’ll need the pandas library. You may already have it installed. If you don’t, then you can install it with pip:

Once the installation process completes, you should have pandas installed and ready.

Anaconda is an excellent Python distribution that comes with Python, many useful packages like pandas, and a package and environment manager called Conda. To learn more about Anaconda, check out Setting Up Python for Machine Learning on Windows.

If you don’t have pandas in your virtual environment, then you can install it with Conda:

Conda is powerful as it manages the dependencies and their versions. To learn more about working with Conda, you can check out the official documentation.

Preparing Data

In this tutorial, you’ll use the data related to 20 countries. Here’s an overview of the data and sources you’ll be working with:

-

Country is denoted by the country name. Each country is in the top 10 list for either population, area, or gross domestic product (GDP). The row labels for the dataset are the three-letter country codes defined in ISO 3166-1. The column label for the dataset is

COUNTRY. -

Population is expressed in millions. The data comes from a list of countries and dependencies by population on Wikipedia. The column label for the dataset is

POP. -

Area is expressed in thousands of kilometers squared. The data comes from a list of countries and dependencies by area on Wikipedia. The column label for the dataset is

AREA. -

Gross domestic product is expressed in millions of U.S. dollars, according to the United Nations data for 2017. You can find this data in the list of countries by nominal GDP on Wikipedia. The column label for the dataset is

GDP. -

Continent is either Africa, Asia, Oceania, Europe, North America, or South America. You can find this information on Wikipedia as well. The column label for the dataset is

CONT. -

Independence day is a date that commemorates a nation’s independence. The data comes from the list of national independence days on Wikipedia. The dates are shown in ISO 8601 format. The first four digits represent the year, the next two numbers are the month, and the last two are for the day of the month. The column label for the dataset is

IND_DAY.

This is how the data looks as a table:

| COUNTRY | POP | AREA | GDP | CONT | IND_DAY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHN | China | 1398.72 | 9596.96 | 12234.78 | Asia | |

| IND | India | 1351.16 | 3287.26 | 2575.67 | Asia | 1947-08-15 |

| USA | US | 329.74 | 9833.52 | 19485.39 | N.America | 1776-07-04 |

| IDN | Indonesia | 268.07 | 1910.93 | 1015.54 | Asia | 1945-08-17 |

| BRA | Brazil | 210.32 | 8515.77 | 2055.51 | S.America | 1822-09-07 |

| PAK | Pakistan | 205.71 | 881.91 | 302.14 | Asia | 1947-08-14 |

| NGA | Nigeria | 200.96 | 923.77 | 375.77 | Africa | 1960-10-01 |

| BGD | Bangladesh | 167.09 | 147.57 | 245.63 | Asia | 1971-03-26 |

| RUS | Russia | 146.79 | 17098.25 | 1530.75 | 1992-06-12 | |

| MEX | Mexico | 126.58 | 1964.38 | 1158.23 | N.America | 1810-09-16 |

| JPN | Japan | 126.22 | 377.97 | 4872.42 | Asia | |

| DEU | Germany | 83.02 | 357.11 | 3693.20 | Europe | |

| FRA | France | 67.02 | 640.68 | 2582.49 | Europe | 1789-07-14 |

| GBR | UK | 66.44 | 242.50 | 2631.23 | Europe | |

| ITA | Italy | 60.36 | 301.34 | 1943.84 | Europe | |

| ARG | Argentina | 44.94 | 2780.40 | 637.49 | S.America | 1816-07-09 |

| DZA | Algeria | 43.38 | 2381.74 | 167.56 | Africa | 1962-07-05 |

| CAN | Canada | 37.59 | 9984.67 | 1647.12 | N.America | 1867-07-01 |

| AUS | Australia | 25.47 | 7692.02 | 1408.68 | Oceania | |

| KAZ | Kazakhstan | 18.53 | 2724.90 | 159.41 | Asia | 1991-12-16 |

You may notice that some of the data is missing. For example, the continent for Russia is not specified because it spreads across both Europe and Asia. There are also several missing independence days because the data source omits them.

You can organize this data in Python using a nested dictionary:

data = {

'CHN': {'COUNTRY': 'China', 'POP': 1_398.72, 'AREA': 9_596.96,

'GDP': 12_234.78, 'CONT': 'Asia'},

'IND': {'COUNTRY': 'India', 'POP': 1_351.16, 'AREA': 3_287.26,

'GDP': 2_575.67, 'CONT': 'Asia', 'IND_DAY': '1947-08-15'},

'USA': {'COUNTRY': 'US', 'POP': 329.74, 'AREA': 9_833.52,

'GDP': 19_485.39, 'CONT': 'N.America',

'IND_DAY': '1776-07-04'},

'IDN': {'COUNTRY': 'Indonesia', 'POP': 268.07, 'AREA': 1_910.93,

'GDP': 1_015.54, 'CONT': 'Asia', 'IND_DAY': '1945-08-17'},

'BRA': {'COUNTRY': 'Brazil', 'POP': 210.32, 'AREA': 8_515.77,

'GDP': 2_055.51, 'CONT': 'S.America', 'IND_DAY': '1822-09-07'},

'PAK': {'COUNTRY': 'Pakistan', 'POP': 205.71, 'AREA': 881.91,

'GDP': 302.14, 'CONT': 'Asia', 'IND_DAY': '1947-08-14'},

'NGA': {'COUNTRY': 'Nigeria', 'POP': 200.96, 'AREA': 923.77,

'GDP': 375.77, 'CONT': 'Africa', 'IND_DAY': '1960-10-01'},

'BGD': {'COUNTRY': 'Bangladesh', 'POP': 167.09, 'AREA': 147.57,

'GDP': 245.63, 'CONT': 'Asia', 'IND_DAY': '1971-03-26'},

'RUS': {'COUNTRY': 'Russia', 'POP': 146.79, 'AREA': 17_098.25,

'GDP': 1_530.75, 'IND_DAY': '1992-06-12'},

'MEX': {'COUNTRY': 'Mexico', 'POP': 126.58, 'AREA': 1_964.38,

'GDP': 1_158.23, 'CONT': 'N.America', 'IND_DAY': '1810-09-16'},

'JPN': {'COUNTRY': 'Japan', 'POP': 126.22, 'AREA': 377.97,

'GDP': 4_872.42, 'CONT': 'Asia'},

'DEU': {'COUNTRY': 'Germany', 'POP': 83.02, 'AREA': 357.11,

'GDP': 3_693.20, 'CONT': 'Europe'},

'FRA': {'COUNTRY': 'France', 'POP': 67.02, 'AREA': 640.68,

'GDP': 2_582.49, 'CONT': 'Europe', 'IND_DAY': '1789-07-14'},

'GBR': {'COUNTRY': 'UK', 'POP': 66.44, 'AREA': 242.50,

'GDP': 2_631.23, 'CONT': 'Europe'},

'ITA': {'COUNTRY': 'Italy', 'POP': 60.36, 'AREA': 301.34,

'GDP': 1_943.84, 'CONT': 'Europe'},

'ARG': {'COUNTRY': 'Argentina', 'POP': 44.94, 'AREA': 2_780.40,

'GDP': 637.49, 'CONT': 'S.America', 'IND_DAY': '1816-07-09'},

'DZA': {'COUNTRY': 'Algeria', 'POP': 43.38, 'AREA': 2_381.74,

'GDP': 167.56, 'CONT': 'Africa', 'IND_DAY': '1962-07-05'},

'CAN': {'COUNTRY': 'Canada', 'POP': 37.59, 'AREA': 9_984.67,

'GDP': 1_647.12, 'CONT': 'N.America', 'IND_DAY': '1867-07-01'},

'AUS': {'COUNTRY': 'Australia', 'POP': 25.47, 'AREA': 7_692.02,

'GDP': 1_408.68, 'CONT': 'Oceania'},

'KAZ': {'COUNTRY': 'Kazakhstan', 'POP': 18.53, 'AREA': 2_724.90,

'GDP': 159.41, 'CONT': 'Asia', 'IND_DAY': '1991-12-16'}

}

columns = ('COUNTRY', 'POP', 'AREA', 'GDP', 'CONT', 'IND_DAY')

Each row of the table is written as an inner dictionary whose keys are the column names and values are the corresponding data. These dictionaries are then collected as the values in the outer data dictionary. The corresponding keys for data are the three-letter country codes.

You can use this data to create an instance of a pandas DataFrame. First, you need to import pandas:

>>>

>>> import pandas as pd

Now that you have pandas imported, you can use the DataFrame constructor and data to create a DataFrame object.

data is organized in such a way that the country codes correspond to columns. You can reverse the rows and columns of a DataFrame with the property .T:

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

>>> df

COUNTRY POP AREA GDP CONT IND_DAY

CHN China 1398.72 9596.96 12234.8 Asia NaN

IND India 1351.16 3287.26 2575.67 Asia 1947-08-15

USA US 329.74 9833.52 19485.4 N.America 1776-07-04

IDN Indonesia 268.07 1910.93 1015.54 Asia 1945-08-17

BRA Brazil 210.32 8515.77 2055.51 S.America 1822-09-07

PAK Pakistan 205.71 881.91 302.14 Asia 1947-08-14

NGA Nigeria 200.96 923.77 375.77 Africa 1960-10-01

BGD Bangladesh 167.09 147.57 245.63 Asia 1971-03-26

RUS Russia 146.79 17098.2 1530.75 NaN 1992-06-12

MEX Mexico 126.58 1964.38 1158.23 N.America 1810-09-16

JPN Japan 126.22 377.97 4872.42 Asia NaN

DEU Germany 83.02 357.11 3693.2 Europe NaN

FRA France 67.02 640.68 2582.49 Europe 1789-07-14

GBR UK 66.44 242.5 2631.23 Europe NaN

ITA Italy 60.36 301.34 1943.84 Europe NaN

ARG Argentina 44.94 2780.4 637.49 S.America 1816-07-09

DZA Algeria 43.38 2381.74 167.56 Africa 1962-07-05

CAN Canada 37.59 9984.67 1647.12 N.America 1867-07-01

AUS Australia 25.47 7692.02 1408.68 Oceania NaN

KAZ Kazakhstan 18.53 2724.9 159.41 Asia 1991-12-16

Now you have your DataFrame object populated with the data about each country.

Versions of Python older than 3.6 did not guarantee the order of keys in dictionaries. To ensure the order of columns is maintained for older versions of Python and pandas, you can specify index=columns:

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data, index=columns).T

Now that you’ve prepared your data, you’re ready to start working with files!

Using the pandas read_csv() and .to_csv() Functions

A comma-separated values (CSV) file is a plaintext file with a .csv extension that holds tabular data. This is one of the most popular file formats for storing large amounts of data. Each row of the CSV file represents a single table row. The values in the same row are by default separated with commas, but you could change the separator to a semicolon, tab, space, or some other character.

Write a CSV File

You can save your pandas DataFrame as a CSV file with .to_csv():

>>>

>>> df.to_csv('data.csv')

That’s it! You’ve created the file data.csv in your current working directory. You can expand the code block below to see how your CSV file should look:

,COUNTRY,POP,AREA,GDP,CONT,IND_DAY

CHN,China,1398.72,9596.96,12234.78,Asia,

IND,India,1351.16,3287.26,2575.67,Asia,1947-08-15

USA,US,329.74,9833.52,19485.39,N.America,1776-07-04

IDN,Indonesia,268.07,1910.93,1015.54,Asia,1945-08-17

BRA,Brazil,210.32,8515.77,2055.51,S.America,1822-09-07

PAK,Pakistan,205.71,881.91,302.14,Asia,1947-08-14

NGA,Nigeria,200.96,923.77,375.77,Africa,1960-10-01

BGD,Bangladesh,167.09,147.57,245.63,Asia,1971-03-26

RUS,Russia,146.79,17098.25,1530.75,,1992-06-12

MEX,Mexico,126.58,1964.38,1158.23,N.America,1810-09-16

JPN,Japan,126.22,377.97,4872.42,Asia,

DEU,Germany,83.02,357.11,3693.2,Europe,

FRA,France,67.02,640.68,2582.49,Europe,1789-07-14

GBR,UK,66.44,242.5,2631.23,Europe,

ITA,Italy,60.36,301.34,1943.84,Europe,

ARG,Argentina,44.94,2780.4,637.49,S.America,1816-07-09

DZA,Algeria,43.38,2381.74,167.56,Africa,1962-07-05

CAN,Canada,37.59,9984.67,1647.12,N.America,1867-07-01

AUS,Australia,25.47,7692.02,1408.68,Oceania,

KAZ,Kazakhstan,18.53,2724.9,159.41,Asia,1991-12-16

This text file contains the data separated with commas. The first column contains the row labels. In some cases, you’ll find them irrelevant. If you don’t want to keep them, then you can pass the argument index=False to .to_csv().

Read a CSV File

Once your data is saved in a CSV file, you’ll likely want to load and use it from time to time. You can do that with the pandas read_csv() function:

>>>

>>> df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', index_col=0)

>>> df

COUNTRY POP AREA GDP CONT IND_DAY

CHN China 1398.72 9596.96 12234.78 Asia NaN

IND India 1351.16 3287.26 2575.67 Asia 1947-08-15

USA US 329.74 9833.52 19485.39 N.America 1776-07-04

IDN Indonesia 268.07 1910.93 1015.54 Asia 1945-08-17

BRA Brazil 210.32 8515.77 2055.51 S.America 1822-09-07

PAK Pakistan 205.71 881.91 302.14 Asia 1947-08-14

NGA Nigeria 200.96 923.77 375.77 Africa 1960-10-01

BGD Bangladesh 167.09 147.57 245.63 Asia 1971-03-26

RUS Russia 146.79 17098.25 1530.75 NaN 1992-06-12

MEX Mexico 126.58 1964.38 1158.23 N.America 1810-09-16

JPN Japan 126.22 377.97 4872.42 Asia NaN

DEU Germany 83.02 357.11 3693.20 Europe NaN

FRA France 67.02 640.68 2582.49 Europe 1789-07-14

GBR UK 66.44 242.50 2631.23 Europe NaN

ITA Italy 60.36 301.34 1943.84 Europe NaN

ARG Argentina 44.94 2780.40 637.49 S.America 1816-07-09

DZA Algeria 43.38 2381.74 167.56 Africa 1962-07-05

CAN Canada 37.59 9984.67 1647.12 N.America 1867-07-01

AUS Australia 25.47 7692.02 1408.68 Oceania NaN

KAZ Kazakhstan 18.53 2724.90 159.41 Asia 1991-12-16

In this case, the pandas read_csv() function returns a new DataFrame with the data and labels from the file data.csv, which you specified with the first argument. This string can be any valid path, including URLs.

The parameter index_col specifies the column from the CSV file that contains the row labels. You assign a zero-based column index to this parameter. You should determine the value of index_col when the CSV file contains the row labels to avoid loading them as data.

You’ll learn more about using pandas with CSV files later on in this tutorial. You can also check out Reading and Writing CSV Files in Python to see how to handle CSV files with the built-in Python library csv as well.

Using pandas to Write and Read Excel Files

Microsoft Excel is probably the most widely-used spreadsheet software. While older versions used binary .xls files, Excel 2007 introduced the new XML-based .xlsx file. You can read and write Excel files in pandas, similar to CSV files. However, you’ll need to install the following Python packages first:

- xlwt to write to

.xlsfiles - openpyxl or XlsxWriter to write to

.xlsxfiles - xlrd to read Excel files

You can install them using pip with a single command:

$ pip install xlwt openpyxl xlsxwriter xlrd

You can also use Conda:

$ conda install xlwt openpyxl xlsxwriter xlrd

Please note that you don’t have to install all these packages. For example, you don’t need both openpyxl and XlsxWriter. If you’re going to work just with .xls files, then you don’t need any of them! However, if you intend to work only with .xlsx files, then you’re going to need at least one of them, but not xlwt. Take some time to decide which packages are right for your project.

Write an Excel File

Once you have those packages installed, you can save your DataFrame in an Excel file with .to_excel():

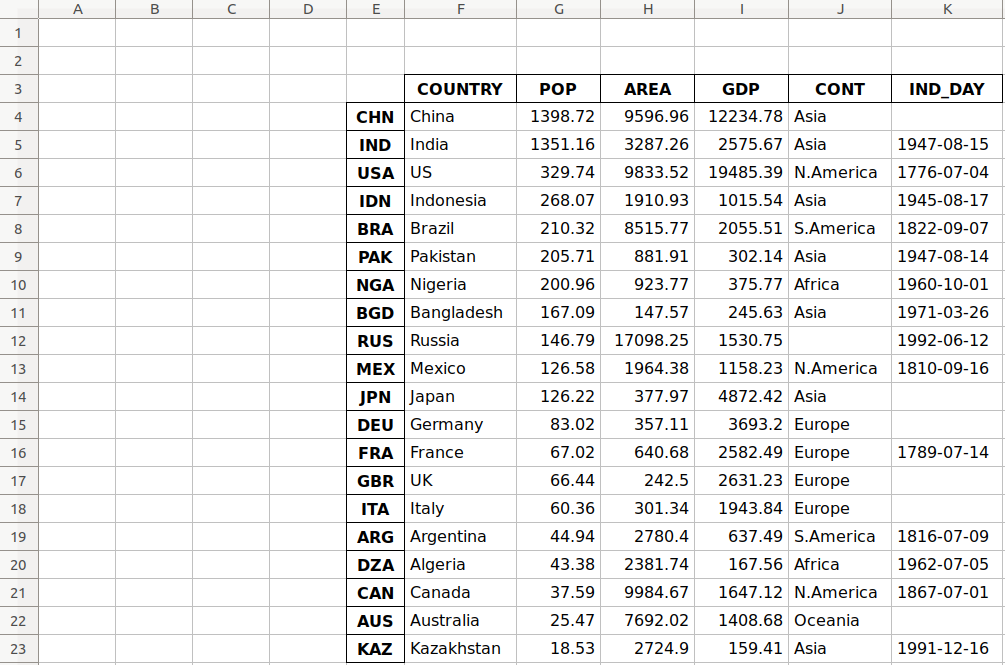

>>>

>>> df.to_excel('data.xlsx')

The argument 'data.xlsx' represents the target file and, optionally, its path. The above statement should create the file data.xlsx in your current working directory. That file should look like this:

The first column of the file contains the labels of the rows, while the other columns store data.

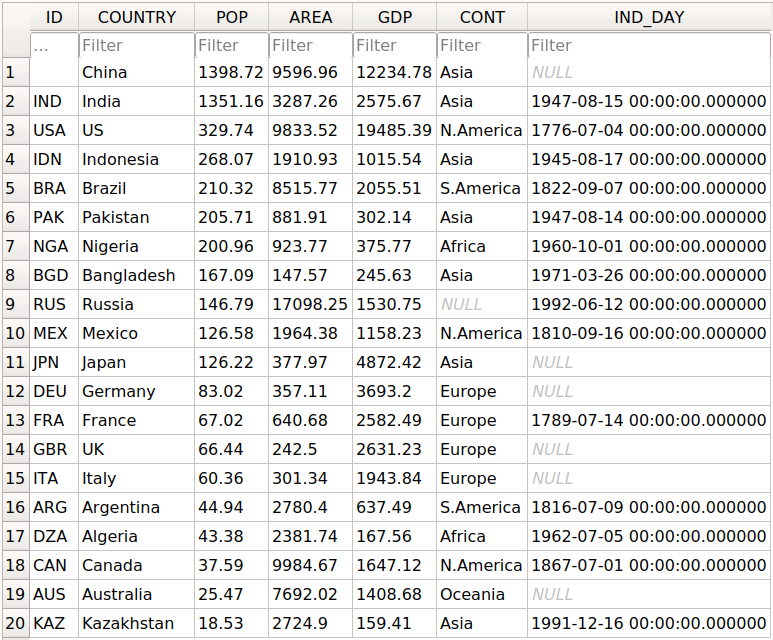

Read an Excel File

You can load data from Excel files with read_excel():

>>>

>>> df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', index_col=0)

>>> df

COUNTRY POP AREA GDP CONT IND_DAY

CHN China 1398.72 9596.96 12234.78 Asia NaN

IND India 1351.16 3287.26 2575.67 Asia 1947-08-15

USA US 329.74 9833.52 19485.39 N.America 1776-07-04

IDN Indonesia 268.07 1910.93 1015.54 Asia 1945-08-17

BRA Brazil 210.32 8515.77 2055.51 S.America 1822-09-07

PAK Pakistan 205.71 881.91 302.14 Asia 1947-08-14

NGA Nigeria 200.96 923.77 375.77 Africa 1960-10-01

BGD Bangladesh 167.09 147.57 245.63 Asia 1971-03-26

RUS Russia 146.79 17098.25 1530.75 NaN 1992-06-12

MEX Mexico 126.58 1964.38 1158.23 N.America 1810-09-16

JPN Japan 126.22 377.97 4872.42 Asia NaN

DEU Germany 83.02 357.11 3693.20 Europe NaN

FRA France 67.02 640.68 2582.49 Europe 1789-07-14

GBR UK 66.44 242.50 2631.23 Europe NaN

ITA Italy 60.36 301.34 1943.84 Europe NaN

ARG Argentina 44.94 2780.40 637.49 S.America 1816-07-09

DZA Algeria 43.38 2381.74 167.56 Africa 1962-07-05

CAN Canada 37.59 9984.67 1647.12 N.America 1867-07-01

AUS Australia 25.47 7692.02 1408.68 Oceania NaN

KAZ Kazakhstan 18.53 2724.90 159.41 Asia 1991-12-16

read_excel() returns a new DataFrame that contains the values from data.xlsx. You can also use read_excel() with OpenDocument spreadsheets, or .ods files.

You’ll learn more about working with Excel files later on in this tutorial. You can also check out Using pandas to Read Large Excel Files in Python.

Understanding the pandas IO API

pandas IO Tools is the API that allows you to save the contents of Series and DataFrame objects to the clipboard, objects, or files of various types. It also enables loading data from the clipboard, objects, or files.

Write Files

Series and DataFrame objects have methods that enable writing data and labels to the clipboard or files. They’re named with the pattern .to_<file-type>(), where <file-type> is the type of the target file.

You’ve learned about .to_csv() and .to_excel(), but there are others, including:

.to_json().to_html().to_sql().to_pickle()

There are still more file types that you can write to, so this list is not exhaustive.

These methods have parameters specifying the target file path where you saved the data and labels. This is mandatory in some cases and optional in others. If this option is available and you choose to omit it, then the methods return the objects (like strings or iterables) with the contents of DataFrame instances.

The optional parameter compression decides how to compress the file with the data and labels. You’ll learn more about it later on. There are a few other parameters, but they’re mostly specific to one or several methods. You won’t go into them in detail here.

Read Files

pandas functions for reading the contents of files are named using the pattern .read_<file-type>(), where <file-type> indicates the type of the file to read. You’ve already seen the pandas read_csv() and read_excel() functions. Here are a few others:

read_json()read_html()read_sql()read_pickle()

These functions have a parameter that specifies the target file path. It can be any valid string that represents the path, either on a local machine or in a URL. Other objects are also acceptable depending on the file type.

The optional parameter compression determines the type of decompression to use for the compressed files. You’ll learn about it later on in this tutorial. There are other parameters, but they’re specific to one or several functions. You won’t go into them in detail here.

Working With Different File Types

The pandas library offers a wide range of possibilities for saving your data to files and loading data from files. In this section, you’ll learn more about working with CSV and Excel files. You’ll also see how to use other types of files, like JSON, web pages, databases, and Python pickle files.

CSV Files

You’ve already learned how to read and write CSV files. Now let’s dig a little deeper into the details. When you use .to_csv() to save your DataFrame, you can provide an argument for the parameter path_or_buf to specify the path, name, and extension of the target file.

path_or_buf is the first argument .to_csv() will get. It can be any string that represents a valid file path that includes the file name and its extension. You’ve seen this in a previous example. However, if you omit path_or_buf, then .to_csv() won’t create any files. Instead, it’ll return the corresponding string:

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

>>> s = df.to_csv()

>>> print(s)

,COUNTRY,POP,AREA,GDP,CONT,IND_DAY

CHN,China,1398.72,9596.96,12234.78,Asia,

IND,India,1351.16,3287.26,2575.67,Asia,1947-08-15

USA,US,329.74,9833.52,19485.39,N.America,1776-07-04

IDN,Indonesia,268.07,1910.93,1015.54,Asia,1945-08-17

BRA,Brazil,210.32,8515.77,2055.51,S.America,1822-09-07

PAK,Pakistan,205.71,881.91,302.14,Asia,1947-08-14

NGA,Nigeria,200.96,923.77,375.77,Africa,1960-10-01

BGD,Bangladesh,167.09,147.57,245.63,Asia,1971-03-26

RUS,Russia,146.79,17098.25,1530.75,,1992-06-12

MEX,Mexico,126.58,1964.38,1158.23,N.America,1810-09-16

JPN,Japan,126.22,377.97,4872.42,Asia,

DEU,Germany,83.02,357.11,3693.2,Europe,

FRA,France,67.02,640.68,2582.49,Europe,1789-07-14

GBR,UK,66.44,242.5,2631.23,Europe,

ITA,Italy,60.36,301.34,1943.84,Europe,

ARG,Argentina,44.94,2780.4,637.49,S.America,1816-07-09

DZA,Algeria,43.38,2381.74,167.56,Africa,1962-07-05

CAN,Canada,37.59,9984.67,1647.12,N.America,1867-07-01

AUS,Australia,25.47,7692.02,1408.68,Oceania,

KAZ,Kazakhstan,18.53,2724.9,159.41,Asia,1991-12-16

Now you have the string s instead of a CSV file. You also have some missing values in your DataFrame object. For example, the continent for Russia and the independence days for several countries (China, Japan, and so on) are not available. In data science and machine learning, you must handle missing values carefully. pandas excels here! By default, pandas uses the NaN value to replace the missing values.

The continent that corresponds to Russia in df is nan:

>>>

>>> df.loc['RUS', 'CONT']

nan

This example uses .loc[] to get data with the specified row and column names.

When you save your DataFrame to a CSV file, empty strings ('') will represent the missing data. You can see this both in your file data.csv and in the string s. If you want to change this behavior, then use the optional parameter na_rep:

>>>

>>> df.to_csv('new-data.csv', na_rep='(missing)')

This code produces the file new-data.csv where the missing values are no longer empty strings. You can expand the code block below to see how this file should look:

,COUNTRY,POP,AREA,GDP,CONT,IND_DAY

CHN,China,1398.72,9596.96,12234.78,Asia,(missing)

IND,India,1351.16,3287.26,2575.67,Asia,1947-08-15

USA,US,329.74,9833.52,19485.39,N.America,1776-07-04

IDN,Indonesia,268.07,1910.93,1015.54,Asia,1945-08-17

BRA,Brazil,210.32,8515.77,2055.51,S.America,1822-09-07

PAK,Pakistan,205.71,881.91,302.14,Asia,1947-08-14

NGA,Nigeria,200.96,923.77,375.77,Africa,1960-10-01

BGD,Bangladesh,167.09,147.57,245.63,Asia,1971-03-26

RUS,Russia,146.79,17098.25,1530.75,(missing),1992-06-12

MEX,Mexico,126.58,1964.38,1158.23,N.America,1810-09-16

JPN,Japan,126.22,377.97,4872.42,Asia,(missing)

DEU,Germany,83.02,357.11,3693.2,Europe,(missing)

FRA,France,67.02,640.68,2582.49,Europe,1789-07-14

GBR,UK,66.44,242.5,2631.23,Europe,(missing)

ITA,Italy,60.36,301.34,1943.84,Europe,(missing)

ARG,Argentina,44.94,2780.4,637.49,S.America,1816-07-09

DZA,Algeria,43.38,2381.74,167.56,Africa,1962-07-05

CAN,Canada,37.59,9984.67,1647.12,N.America,1867-07-01

AUS,Australia,25.47,7692.02,1408.68,Oceania,(missing)

KAZ,Kazakhstan,18.53,2724.9,159.41,Asia,1991-12-16

Now, the string '(missing)' in the file corresponds to the nan values from df.

When pandas reads files, it considers the empty string ('') and a few others as missing values by default:

'nan''-nan''NA''N/A''NaN''null'

If you don’t want this behavior, then you can pass keep_default_na=False to the pandas read_csv() function. To specify other labels for missing values, use the parameter na_values:

>>>

>>> pd.read_csv('new-data.csv', index_col=0, na_values='(missing)')

COUNTRY POP AREA GDP CONT IND_DAY

CHN China 1398.72 9596.96 12234.78 Asia NaN

IND India 1351.16 3287.26 2575.67 Asia 1947-08-15

USA US 329.74 9833.52 19485.39 N.America 1776-07-04

IDN Indonesia 268.07 1910.93 1015.54 Asia 1945-08-17

BRA Brazil 210.32 8515.77 2055.51 S.America 1822-09-07

PAK Pakistan 205.71 881.91 302.14 Asia 1947-08-14

NGA Nigeria 200.96 923.77 375.77 Africa 1960-10-01

BGD Bangladesh 167.09 147.57 245.63 Asia 1971-03-26

RUS Russia 146.79 17098.25 1530.75 NaN 1992-06-12

MEX Mexico 126.58 1964.38 1158.23 N.America 1810-09-16

JPN Japan 126.22 377.97 4872.42 Asia NaN

DEU Germany 83.02 357.11 3693.20 Europe NaN

FRA France 67.02 640.68 2582.49 Europe 1789-07-14

GBR UK 66.44 242.50 2631.23 Europe NaN

ITA Italy 60.36 301.34 1943.84 Europe NaN

ARG Argentina 44.94 2780.40 637.49 S.America 1816-07-09

DZA Algeria 43.38 2381.74 167.56 Africa 1962-07-05

CAN Canada 37.59 9984.67 1647.12 N.America 1867-07-01

AUS Australia 25.47 7692.02 1408.68 Oceania NaN

KAZ Kazakhstan 18.53 2724.90 159.41 Asia 1991-12-16

Here, you’ve marked the string '(missing)' as a new missing data label, and pandas replaced it with nan when it read the file.

When you load data from a file, pandas assigns the data types to the values of each column by default. You can check these types with .dtypes:

>>>

>>> df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', index_col=0)

>>> df.dtypes

COUNTRY object

POP float64

AREA float64

GDP float64

CONT object

IND_DAY object

dtype: object

The columns with strings and dates ('COUNTRY', 'CONT', and 'IND_DAY') have the data type object. Meanwhile, the numeric columns contain 64-bit floating-point numbers (float64).

You can use the parameter dtype to specify the desired data types and parse_dates to force use of datetimes:

>>>

>>> dtypes = {'POP': 'float32', 'AREA': 'float32', 'GDP': 'float32'}

>>> df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', index_col=0, dtype=dtypes,

... parse_dates=['IND_DAY'])

>>> df.dtypes

COUNTRY object

POP float32

AREA float32

GDP float32

CONT object

IND_DAY datetime64[ns]

dtype: object

>>> df['IND_DAY']

CHN NaT

IND 1947-08-15

USA 1776-07-04

IDN 1945-08-17

BRA 1822-09-07

PAK 1947-08-14

NGA 1960-10-01

BGD 1971-03-26

RUS 1992-06-12

MEX 1810-09-16

JPN NaT

DEU NaT

FRA 1789-07-14

GBR NaT

ITA NaT

ARG 1816-07-09

DZA 1962-07-05

CAN 1867-07-01

AUS NaT

KAZ 1991-12-16

Name: IND_DAY, dtype: datetime64[ns]

Now, you have 32-bit floating-point numbers (float32) as specified with dtype. These differ slightly from the original 64-bit numbers because of smaller precision. The values in the last column are considered as dates and have the data type datetime64. That’s why the NaN values in this column are replaced with NaT.

Now that you have real dates, you can save them in the format you like:

>>>

>>> df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', index_col=0, parse_dates=['IND_DAY'])

>>> df.to_csv('formatted-data.csv', date_format='%B %d, %Y')

Here, you’ve specified the parameter date_format to be '%B %d, %Y'. You can expand the code block below to see the resulting file:

,COUNTRY,POP,AREA,GDP,CONT,IND_DAY

CHN,China,1398.72,9596.96,12234.78,Asia,

IND,India,1351.16,3287.26,2575.67,Asia,"August 15, 1947"

USA,US,329.74,9833.52,19485.39,N.America,"July 04, 1776"

IDN,Indonesia,268.07,1910.93,1015.54,Asia,"August 17, 1945"

BRA,Brazil,210.32,8515.77,2055.51,S.America,"September 07, 1822"

PAK,Pakistan,205.71,881.91,302.14,Asia,"August 14, 1947"

NGA,Nigeria,200.96,923.77,375.77,Africa,"October 01, 1960"

BGD,Bangladesh,167.09,147.57,245.63,Asia,"March 26, 1971"

RUS,Russia,146.79,17098.25,1530.75,,"June 12, 1992"

MEX,Mexico,126.58,1964.38,1158.23,N.America,"September 16, 1810"

JPN,Japan,126.22,377.97,4872.42,Asia,

DEU,Germany,83.02,357.11,3693.2,Europe,

FRA,France,67.02,640.68,2582.49,Europe,"July 14, 1789"

GBR,UK,66.44,242.5,2631.23,Europe,

ITA,Italy,60.36,301.34,1943.84,Europe,

ARG,Argentina,44.94,2780.4,637.49,S.America,"July 09, 1816"

DZA,Algeria,43.38,2381.74,167.56,Africa,"July 05, 1962"

CAN,Canada,37.59,9984.67,1647.12,N.America,"July 01, 1867"

AUS,Australia,25.47,7692.02,1408.68,Oceania,

KAZ,Kazakhstan,18.53,2724.9,159.41,Asia,"December 16, 1991"

The format of the dates is different now. The format '%B %d, %Y' means the date will first display the full name of the month, then the day followed by a comma, and finally the full year.

There are several other optional parameters that you can use with .to_csv():

sepdenotes a values separator.decimalindicates a decimal separator.encodingsets the file encoding.headerspecifies whether you want to write column labels in the file.

Here’s how you would pass arguments for sep and header:

>>>

>>> s = df.to_csv(sep=';', header=False)

>>> print(s)

CHN;China;1398.72;9596.96;12234.78;Asia;

IND;India;1351.16;3287.26;2575.67;Asia;1947-08-15

USA;US;329.74;9833.52;19485.39;N.America;1776-07-04

IDN;Indonesia;268.07;1910.93;1015.54;Asia;1945-08-17

BRA;Brazil;210.32;8515.77;2055.51;S.America;1822-09-07

PAK;Pakistan;205.71;881.91;302.14;Asia;1947-08-14

NGA;Nigeria;200.96;923.77;375.77;Africa;1960-10-01

BGD;Bangladesh;167.09;147.57;245.63;Asia;1971-03-26

RUS;Russia;146.79;17098.25;1530.75;;1992-06-12

MEX;Mexico;126.58;1964.38;1158.23;N.America;1810-09-16

JPN;Japan;126.22;377.97;4872.42;Asia;

DEU;Germany;83.02;357.11;3693.2;Europe;

FRA;France;67.02;640.68;2582.49;Europe;1789-07-14

GBR;UK;66.44;242.5;2631.23;Europe;

ITA;Italy;60.36;301.34;1943.84;Europe;

ARG;Argentina;44.94;2780.4;637.49;S.America;1816-07-09

DZA;Algeria;43.38;2381.74;167.56;Africa;1962-07-05

CAN;Canada;37.59;9984.67;1647.12;N.America;1867-07-01

AUS;Australia;25.47;7692.02;1408.68;Oceania;

KAZ;Kazakhstan;18.53;2724.9;159.41;Asia;1991-12-16

The data is separated with a semicolon (';') because you’ve specified sep=';'. Also, since you passed header=False, you see your data without the header row of column names.

The pandas read_csv() function has many additional options for managing missing data, working with dates and times, quoting, encoding, handling errors, and more. For instance, if you have a file with one data column and want to get a Series object instead of a DataFrame, then you can pass squeeze=True to read_csv(). You’ll learn later on about data compression and decompression, as well as how to skip rows and columns.

JSON Files

JSON stands for JavaScript object notation. JSON files are plaintext files used for data interchange, and humans can read them easily. They follow the ISO/IEC 21778:2017 and ECMA-404 standards and use the .json extension. Python and pandas work well with JSON files, as Python’s json library offers built-in support for them.

You can save the data from your DataFrame to a JSON file with .to_json(). Start by creating a DataFrame object again. Use the dictionary data that holds the data about countries and then apply .to_json():

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

>>> df.to_json('data-columns.json')

This code produces the file data-columns.json. You can expand the code block below to see how this file should look:

{"COUNTRY":{"CHN":"China","IND":"India","USA":"US","IDN":"Indonesia","BRA":"Brazil","PAK":"Pakistan","NGA":"Nigeria","BGD":"Bangladesh","RUS":"Russia","MEX":"Mexico","JPN":"Japan","DEU":"Germany","FRA":"France","GBR":"UK","ITA":"Italy","ARG":"Argentina","DZA":"Algeria","CAN":"Canada","AUS":"Australia","KAZ":"Kazakhstan"},"POP":{"CHN":1398.72,"IND":1351.16,"USA":329.74,"IDN":268.07,"BRA":210.32,"PAK":205.71,"NGA":200.96,"BGD":167.09,"RUS":146.79,"MEX":126.58,"JPN":126.22,"DEU":83.02,"FRA":67.02,"GBR":66.44,"ITA":60.36,"ARG":44.94,"DZA":43.38,"CAN":37.59,"AUS":25.47,"KAZ":18.53},"AREA":{"CHN":9596.96,"IND":3287.26,"USA":9833.52,"IDN":1910.93,"BRA":8515.77,"PAK":881.91,"NGA":923.77,"BGD":147.57,"RUS":17098.25,"MEX":1964.38,"JPN":377.97,"DEU":357.11,"FRA":640.68,"GBR":242.5,"ITA":301.34,"ARG":2780.4,"DZA":2381.74,"CAN":9984.67,"AUS":7692.02,"KAZ":2724.9},"GDP":{"CHN":12234.78,"IND":2575.67,"USA":19485.39,"IDN":1015.54,"BRA":2055.51,"PAK":302.14,"NGA":375.77,"BGD":245.63,"RUS":1530.75,"MEX":1158.23,"JPN":4872.42,"DEU":3693.2,"FRA":2582.49,"GBR":2631.23,"ITA":1943.84,"ARG":637.49,"DZA":167.56,"CAN":1647.12,"AUS":1408.68,"KAZ":159.41},"CONT":{"CHN":"Asia","IND":"Asia","USA":"N.America","IDN":"Asia","BRA":"S.America","PAK":"Asia","NGA":"Africa","BGD":"Asia","RUS":null,"MEX":"N.America","JPN":"Asia","DEU":"Europe","FRA":"Europe","GBR":"Europe","ITA":"Europe","ARG":"S.America","DZA":"Africa","CAN":"N.America","AUS":"Oceania","KAZ":"Asia"},"IND_DAY":{"CHN":null,"IND":"1947-08-15","USA":"1776-07-04","IDN":"1945-08-17","BRA":"1822-09-07","PAK":"1947-08-14","NGA":"1960-10-01","BGD":"1971-03-26","RUS":"1992-06-12","MEX":"1810-09-16","JPN":null,"DEU":null,"FRA":"1789-07-14","GBR":null,"ITA":null,"ARG":"1816-07-09","DZA":"1962-07-05","CAN":"1867-07-01","AUS":null,"KAZ":"1991-12-16"}}

data-columns.json has one large dictionary with the column labels as keys and the corresponding inner dictionaries as values.

You can get a different file structure if you pass an argument for the optional parameter orient:

>>>

>>> df.to_json('data-index.json', orient='index')

The orient parameter defaults to 'columns'. Here, you’ve set it to index.

You should get a new file data-index.json. You can expand the code block below to see the changes:

{"CHN":{"COUNTRY":"China","POP":1398.72,"AREA":9596.96,"GDP":12234.78,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":null},"IND":{"COUNTRY":"India","POP":1351.16,"AREA":3287.26,"GDP":2575.67,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1947-08-15"},"USA":{"COUNTRY":"US","POP":329.74,"AREA":9833.52,"GDP":19485.39,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1776-07-04"},"IDN":{"COUNTRY":"Indonesia","POP":268.07,"AREA":1910.93,"GDP":1015.54,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1945-08-17"},"BRA":{"COUNTRY":"Brazil","POP":210.32,"AREA":8515.77,"GDP":2055.51,"CONT":"S.America","IND_DAY":"1822-09-07"},"PAK":{"COUNTRY":"Pakistan","POP":205.71,"AREA":881.91,"GDP":302.14,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1947-08-14"},"NGA":{"COUNTRY":"Nigeria","POP":200.96,"AREA":923.77,"GDP":375.77,"CONT":"Africa","IND_DAY":"1960-10-01"},"BGD":{"COUNTRY":"Bangladesh","POP":167.09,"AREA":147.57,"GDP":245.63,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1971-03-26"},"RUS":{"COUNTRY":"Russia","POP":146.79,"AREA":17098.25,"GDP":1530.75,"CONT":null,"IND_DAY":"1992-06-12"},"MEX":{"COUNTRY":"Mexico","POP":126.58,"AREA":1964.38,"GDP":1158.23,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1810-09-16"},"JPN":{"COUNTRY":"Japan","POP":126.22,"AREA":377.97,"GDP":4872.42,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":null},"DEU":{"COUNTRY":"Germany","POP":83.02,"AREA":357.11,"GDP":3693.2,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},"FRA":{"COUNTRY":"France","POP":67.02,"AREA":640.68,"GDP":2582.49,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":"1789-07-14"},"GBR":{"COUNTRY":"UK","POP":66.44,"AREA":242.5,"GDP":2631.23,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},"ITA":{"COUNTRY":"Italy","POP":60.36,"AREA":301.34,"GDP":1943.84,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},"ARG":{"COUNTRY":"Argentina","POP":44.94,"AREA":2780.4,"GDP":637.49,"CONT":"S.America","IND_DAY":"1816-07-09"},"DZA":{"COUNTRY":"Algeria","POP":43.38,"AREA":2381.74,"GDP":167.56,"CONT":"Africa","IND_DAY":"1962-07-05"},"CAN":{"COUNTRY":"Canada","POP":37.59,"AREA":9984.67,"GDP":1647.12,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1867-07-01"},"AUS":{"COUNTRY":"Australia","POP":25.47,"AREA":7692.02,"GDP":1408.68,"CONT":"Oceania","IND_DAY":null},"KAZ":{"COUNTRY":"Kazakhstan","POP":18.53,"AREA":2724.9,"GDP":159.41,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1991-12-16"}}

data-index.json also has one large dictionary, but this time the row labels are the keys, and the inner dictionaries are the values.

There are few more options for orient. One of them is 'records':

>>>

>>> df.to_json('data-records.json', orient='records')

This code should yield the file data-records.json. You can expand the code block below to see the content:

[{"COUNTRY":"China","POP":1398.72,"AREA":9596.96,"GDP":12234.78,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"India","POP":1351.16,"AREA":3287.26,"GDP":2575.67,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1947-08-15"},{"COUNTRY":"US","POP":329.74,"AREA":9833.52,"GDP":19485.39,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1776-07-04"},{"COUNTRY":"Indonesia","POP":268.07,"AREA":1910.93,"GDP":1015.54,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1945-08-17"},{"COUNTRY":"Brazil","POP":210.32,"AREA":8515.77,"GDP":2055.51,"CONT":"S.America","IND_DAY":"1822-09-07"},{"COUNTRY":"Pakistan","POP":205.71,"AREA":881.91,"GDP":302.14,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1947-08-14"},{"COUNTRY":"Nigeria","POP":200.96,"AREA":923.77,"GDP":375.77,"CONT":"Africa","IND_DAY":"1960-10-01"},{"COUNTRY":"Bangladesh","POP":167.09,"AREA":147.57,"GDP":245.63,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1971-03-26"},{"COUNTRY":"Russia","POP":146.79,"AREA":17098.25,"GDP":1530.75,"CONT":null,"IND_DAY":"1992-06-12"},{"COUNTRY":"Mexico","POP":126.58,"AREA":1964.38,"GDP":1158.23,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1810-09-16"},{"COUNTRY":"Japan","POP":126.22,"AREA":377.97,"GDP":4872.42,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"Germany","POP":83.02,"AREA":357.11,"GDP":3693.2,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"France","POP":67.02,"AREA":640.68,"GDP":2582.49,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":"1789-07-14"},{"COUNTRY":"UK","POP":66.44,"AREA":242.5,"GDP":2631.23,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"Italy","POP":60.36,"AREA":301.34,"GDP":1943.84,"CONT":"Europe","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"Argentina","POP":44.94,"AREA":2780.4,"GDP":637.49,"CONT":"S.America","IND_DAY":"1816-07-09"},{"COUNTRY":"Algeria","POP":43.38,"AREA":2381.74,"GDP":167.56,"CONT":"Africa","IND_DAY":"1962-07-05"},{"COUNTRY":"Canada","POP":37.59,"AREA":9984.67,"GDP":1647.12,"CONT":"N.America","IND_DAY":"1867-07-01"},{"COUNTRY":"Australia","POP":25.47,"AREA":7692.02,"GDP":1408.68,"CONT":"Oceania","IND_DAY":null},{"COUNTRY":"Kazakhstan","POP":18.53,"AREA":2724.9,"GDP":159.41,"CONT":"Asia","IND_DAY":"1991-12-16"}]

data-records.json holds a list with one dictionary for each row. The row labels are not written.

You can get another interesting file structure with orient='split':

>>>

>>> df.to_json('data-split.json', orient='split')

The resulting file is data-split.json. You can expand the code block below to see how this file should look:

{"columns":["COUNTRY","POP","AREA","GDP","CONT","IND_DAY"],"index":["CHN","IND","USA","IDN","BRA","PAK","NGA","BGD","RUS","MEX","JPN","DEU","FRA","GBR","ITA","ARG","DZA","CAN","AUS","KAZ"],"data":[["China",1398.72,9596.96,12234.78,"Asia",null],["India",1351.16,3287.26,2575.67,"Asia","1947-08-15"],["US",329.74,9833.52,19485.39,"N.America","1776-07-04"],["Indonesia",268.07,1910.93,1015.54,"Asia","1945-08-17"],["Brazil",210.32,8515.77,2055.51,"S.America","1822-09-07"],["Pakistan",205.71,881.91,302.14,"Asia","1947-08-14"],["Nigeria",200.96,923.77,375.77,"Africa","1960-10-01"],["Bangladesh",167.09,147.57,245.63,"Asia","1971-03-26"],["Russia",146.79,17098.25,1530.75,null,"1992-06-12"],["Mexico",126.58,1964.38,1158.23,"N.America","1810-09-16"],["Japan",126.22,377.97,4872.42,"Asia",null],["Germany",83.02,357.11,3693.2,"Europe",null],["France",67.02,640.68,2582.49,"Europe","1789-07-14"],["UK",66.44,242.5,2631.23,"Europe",null],["Italy",60.36,301.34,1943.84,"Europe",null],["Argentina",44.94,2780.4,637.49,"S.America","1816-07-09"],["Algeria",43.38,2381.74,167.56,"Africa","1962-07-05"],["Canada",37.59,9984.67,1647.12,"N.America","1867-07-01"],["Australia",25.47,7692.02,1408.68,"Oceania",null],["Kazakhstan",18.53,2724.9,159.41,"Asia","1991-12-16"]]}

data-split.json contains one dictionary that holds the following lists:

- The names of the columns

- The labels of the rows

- The inner lists (two-dimensional sequence) that hold data values

If you don’t provide the value for the optional parameter path_or_buf that defines the file path, then .to_json() will return a JSON string instead of writing the results to a file. This behavior is consistent with .to_csv().

There are other optional parameters you can use. For instance, you can set index=False to forgo saving row labels. You can manipulate precision with double_precision, and dates with date_format and date_unit. These last two parameters are particularly important when you have time series among your data:

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

>>> df['IND_DAY'] = pd.to_datetime(df['IND_DAY'])

>>> df.dtypes

COUNTRY object

POP object

AREA object

GDP object

CONT object

IND_DAY datetime64[ns]

dtype: object

>>> df.to_json('data-time.json')

In this example, you’ve created the DataFrame from the dictionary data and used to_datetime() to convert the values in the last column to datetime64. You can expand the code block below to see the resulting file:

{"COUNTRY":{"CHN":"China","IND":"India","USA":"US","IDN":"Indonesia","BRA":"Brazil","PAK":"Pakistan","NGA":"Nigeria","BGD":"Bangladesh","RUS":"Russia","MEX":"Mexico","JPN":"Japan","DEU":"Germany","FRA":"France","GBR":"UK","ITA":"Italy","ARG":"Argentina","DZA":"Algeria","CAN":"Canada","AUS":"Australia","KAZ":"Kazakhstan"},"POP":{"CHN":1398.72,"IND":1351.16,"USA":329.74,"IDN":268.07,"BRA":210.32,"PAK":205.71,"NGA":200.96,"BGD":167.09,"RUS":146.79,"MEX":126.58,"JPN":126.22,"DEU":83.02,"FRA":67.02,"GBR":66.44,"ITA":60.36,"ARG":44.94,"DZA":43.38,"CAN":37.59,"AUS":25.47,"KAZ":18.53},"AREA":{"CHN":9596.96,"IND":3287.26,"USA":9833.52,"IDN":1910.93,"BRA":8515.77,"PAK":881.91,"NGA":923.77,"BGD":147.57,"RUS":17098.25,"MEX":1964.38,"JPN":377.97,"DEU":357.11,"FRA":640.68,"GBR":242.5,"ITA":301.34,"ARG":2780.4,"DZA":2381.74,"CAN":9984.67,"AUS":7692.02,"KAZ":2724.9},"GDP":{"CHN":12234.78,"IND":2575.67,"USA":19485.39,"IDN":1015.54,"BRA":2055.51,"PAK":302.14,"NGA":375.77,"BGD":245.63,"RUS":1530.75,"MEX":1158.23,"JPN":4872.42,"DEU":3693.2,"FRA":2582.49,"GBR":2631.23,"ITA":1943.84,"ARG":637.49,"DZA":167.56,"CAN":1647.12,"AUS":1408.68,"KAZ":159.41},"CONT":{"CHN":"Asia","IND":"Asia","USA":"N.America","IDN":"Asia","BRA":"S.America","PAK":"Asia","NGA":"Africa","BGD":"Asia","RUS":null,"MEX":"N.America","JPN":"Asia","DEU":"Europe","FRA":"Europe","GBR":"Europe","ITA":"Europe","ARG":"S.America","DZA":"Africa","CAN":"N.America","AUS":"Oceania","KAZ":"Asia"},"IND_DAY":{"CHN":null,"IND":-706320000000,"USA":-6106060800000,"IDN":-769219200000,"BRA":-4648924800000,"PAK":-706406400000,"NGA":-291945600000,"BGD":38793600000,"RUS":708307200000,"MEX":-5026838400000,"JPN":null,"DEU":null,"FRA":-5694969600000,"GBR":null,"ITA":null,"ARG":-4843411200000,"DZA":-236476800000,"CAN":-3234729600000,"AUS":null,"KAZ":692841600000}}

In this file, you have large integers instead of dates for the independence days. That’s because the default value of the optional parameter date_format is 'epoch' whenever orient isn’t 'table'. This default behavior expresses dates as an epoch in milliseconds relative to midnight on January 1, 1970.

However, if you pass date_format='iso', then you’ll get the dates in the ISO 8601 format. In addition, date_unit decides the units of time:

>>>

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

>>> df['IND_DAY'] = pd.to_datetime(df['IND_DAY'])

>>> df.to_json('new-data-time.json', date_format='iso', date_unit='s')

This code produces the following JSON file:

{"COUNTRY":{"CHN":"China","IND":"India","USA":"US","IDN":"Indonesia","BRA":"Brazil","PAK":"Pakistan","NGA":"Nigeria","BGD":"Bangladesh","RUS":"Russia","MEX":"Mexico","JPN":"Japan","DEU":"Germany","FRA":"France","GBR":"UK","ITA":"Italy","ARG":"Argentina","DZA":"Algeria","CAN":"Canada","AUS":"Australia","KAZ":"Kazakhstan"},"POP":{"CHN":1398.72,"IND":1351.16,"USA":329.74,"IDN":268.07,"BRA":210.32,"PAK":205.71,"NGA":200.96,"BGD":167.09,"RUS":146.79,"MEX":126.58,"JPN":126.22,"DEU":83.02,"FRA":67.02,"GBR":66.44,"ITA":60.36,"ARG":44.94,"DZA":43.38,"CAN":37.59,"AUS":25.47,"KAZ":18.53},"AREA":{"CHN":9596.96,"IND":3287.26,"USA":9833.52,"IDN":1910.93,"BRA":8515.77,"PAK":881.91,"NGA":923.77,"BGD":147.57,"RUS":17098.25,"MEX":1964.38,"JPN":377.97,"DEU":357.11,"FRA":640.68,"GBR":242.5,"ITA":301.34,"ARG":2780.4,"DZA":2381.74,"CAN":9984.67,"AUS":7692.02,"KAZ":2724.9},"GDP":{"CHN":12234.78,"IND":2575.67,"USA":19485.39,"IDN":1015.54,"BRA":2055.51,"PAK":302.14,"NGA":375.77,"BGD":245.63,"RUS":1530.75,"MEX":1158.23,"JPN":4872.42,"DEU":3693.2,"FRA":2582.49,"GBR":2631.23,"ITA":1943.84,"ARG":637.49,"DZA":167.56,"CAN":1647.12,"AUS":1408.68,"KAZ":159.41},"CONT":{"CHN":"Asia","IND":"Asia","USA":"N.America","IDN":"Asia","BRA":"S.America","PAK":"Asia","NGA":"Africa","BGD":"Asia","RUS":null,"MEX":"N.America","JPN":"Asia","DEU":"Europe","FRA":"Europe","GBR":"Europe","ITA":"Europe","ARG":"S.America","DZA":"Africa","CAN":"N.America","AUS":"Oceania","KAZ":"Asia"},"IND_DAY":{"CHN":null,"IND":"1947-08-15T00:00:00Z","USA":"1776-07-04T00:00:00Z","IDN":"1945-08-17T00:00:00Z","BRA":"1822-09-07T00:00:00Z","PAK":"1947-08-14T00:00:00Z","NGA":"1960-10-01T00:00:00Z","BGD":"1971-03-26T00:00:00Z","RUS":"1992-06-12T00:00:00Z","MEX":"1810-09-16T00:00:00Z","JPN":null,"DEU":null,"FRA":"1789-07-14T00:00:00Z","GBR":null,"ITA":null,"ARG":"1816-07-09T00:00:00Z","DZA":"1962-07-05T00:00:00Z","CAN":"1867-07-01T00:00:00Z","AUS":null,"KAZ":"1991-12-16T00:00:00Z"}}

The dates in the resulting file are in the ISO 8601 format.

You can load the data from a JSON file with read_json():

>>>

>>> df = pd.read_json('data-index.json', orient='index',

... convert_dates=['IND_DAY'])

The parameter convert_dates has a similar purpose as parse_dates when you use it to read CSV files. The optional parameter orient is very important because it specifies how pandas understands the structure of the file.

There are other optional parameters you can use as well:

- Set the encoding with

encoding. - Manipulate dates with

convert_datesandkeep_default_dates. - Impact precision with

dtypeandprecise_float. - Decode numeric data directly to NumPy arrays with

numpy=True.

Note that you might lose the order of rows and columns when using the JSON format to store your data.

HTML Files

An HTML is a plaintext file that uses hypertext markup language to help browsers render web pages. The extensions for HTML files are .html and .htm. You’ll need to install an HTML parser library like lxml or html5lib to be able to work with HTML files:

$pip install lxml html5lib

You can also use Conda to install the same packages:

$ conda install lxml html5lib

Once you have these libraries, you can save the contents of your DataFrame as an HTML file with .to_html():

>>>

df = pd.DataFrame(data=data).T

df.to_html('data.html')

This code generates a file data.html. You can expand the code block below to see how this file should look:

<table border="1" class="dataframe">

<thead>

<tr style="text-align: right;">

<th></th>

<th>COUNTRY</th>

<th>POP</th>

<th>AREA</th>

<th>GDP</th>

<th>CONT</th>

<th>IND_DAY</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<th>CHN</th>

<td>China</td>

<td>1398.72</td>

<td>9596.96</td>

<td>12234.8</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>NaN</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>IND</th>

<td>India</td>

<td>1351.16</td>

<td>3287.26</td>

<td>2575.67</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>1947-08-15</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>USA</th>

<td>US</td>

<td>329.74</td>

<td>9833.52</td>

<td>19485.4</td>

<td>N.America</td>

<td>1776-07-04</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>IDN</th>

<td>Indonesia</td>

<td>268.07</td>

<td>1910.93</td>

<td>1015.54</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>1945-08-17</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>BRA</th>

<td>Brazil</td>

<td>210.32</td>

<td>8515.77</td>

<td>2055.51</td>

<td>S.America</td>

<td>1822-09-07</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>PAK</th>

<td>Pakistan</td>

<td>205.71</td>

<td>881.91</td>

<td>302.14</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>1947-08-14</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>NGA</th>

<td>Nigeria</td>

<td>200.96</td>

<td>923.77</td>

<td>375.77</td>

<td>Africa</td>

<td>1960-10-01</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>BGD</th>

<td>Bangladesh</td>

<td>167.09</td>

<td>147.57</td>

<td>245.63</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>1971-03-26</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>RUS</th>

<td>Russia</td>

<td>146.79</td>

<td>17098.2</td>

<td>1530.75</td>

<td>NaN</td>

<td>1992-06-12</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>MEX</th>

<td>Mexico</td>

<td>126.58</td>

<td>1964.38</td>

<td>1158.23</td>

<td>N.America</td>

<td>1810-09-16</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>JPN</th>

<td>Japan</td>

<td>126.22</td>

<td>377.97</td>

<td>4872.42</td>

<td>Asia</td>

<td>NaN</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>DEU</th>

<td>Germany</td>

<td>83.02</td>

<td>357.11</td>

<td>3693.2</td>

<td>Europe</td>

<td>NaN</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>FRA</th>

<td>France</td>

<td>67.02</td>

<td>640.68</td>

<td>2582.49</td>

<td>Europe</td>

<td>1789-07-14</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>GBR</th>

<td>UK</td>

<td>66.44</td>

<td>242.5</td>

<td>2631.23</td>

<td>Europe</td>

<td>NaN</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>ITA</th>

<td>Italy</td>

<td>60.36</td>

<td>301.34</td>

<td>1943.84</td>

<td>Europe</td>

<td>NaN</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th>ARG</th>

<td>Argentina</td>

<td>44.94</td>

<td>2780.4</td>

<td>637.49</td>

<td>S.America</td>

<td>1816-07-09</td>

</tr>

<tr>