From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The name Britain originates from the Common Brittonic term *Pritanī and is one of the oldest known names for Great Britain, an island off the north-western coast of continental Europe. The terms Briton and British, similarly derived, refer to its inhabitants and, to varying extents, the smaller islands in the vicinity. «British Isles» is the only ancient name for these islands to survive in general usage.

Etymology[edit]

«Britain» comes from Latin: Britannia~Brittania, via Old French Bretaigne and Middle English Breteyne, possibly influenced by Old English Bryten(lond), probably also from Latin Brittania, ultimately an adaptation of the Common Brittonic name for the island, *Pritanī.[1][2]

The earliest written reference to the British Isles derives from the works of the Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia; later Greek writers such as Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo who quote Pytheas’ use of variants such as Πρεττανική (Prettanikē), «The Britannic [land, island]», and nēsoi brettaniai, «Britannic islands», with *Pretani being a Celtic word that might mean «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk», referring to body decoration (see below).[3]

The modern Welsh name for the island is (Ynys) Prydain. This may demonstrate that the original Common Brittonic form had initial P- not B- (which would give **Brydain) and -t- not -tt- (else **Prythain). This may be explained as containing a stem *prit- (Welsh pryd, Old Irish cruith; < Proto-Celtic *kwrit-), meaning «shape, form», combined with an adjectival suffix. This leaves us with *Pritanī.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

History[edit]

Written record[edit]

The first known written use of the word was an ancient Greek transliteration of the original P-Celtic term. It is believed to have appeared within a periplus written in about 325 BC by the geographer and explorer Pytheas of Massalia, but no copies of this work survive. The earliest existing records of the word are quotations of the periplus by later authors, such as those within Diodorus of Sicily’s history (c. 60 BC to 30 BC), Strabo’s Geographica (c. 7 BC to AD 19) and Pliny’s Natural History (AD 77).[10] According to Strabo, Pytheas referred to Britain as Bretannikē, which is treated a feminine noun.[11][12][13][14] Although technically an adjective (the Britannic or British) it may have been a case of noun ellipsis, a common mechanism in ancient Greek. This term along with other relevant ones, subsequently appeared inter alia in the following works:

- Pliny referred to the main island as Britannia, with Britanniae describing the island group.[15][16]

- Catullus also used the plural Britanniae in his Carmina.[17][18]

- Avienius used insula Albionum in his Ora Maritima.[19]

- Orosius used the plural Britanniae to refer to the islands and Britanni to refer to the people thereof.[20]

- Diodorus referred to Great Britain as Prettanikē nēsos and its inhabitants as Prettanoi.[21][22]

- Ptolemy, in his Almagest, used Brettania and Brettanikai nēsoi to refer to the island group and the terms megale Brettania (Great Britain) and mikra Brettania (little Britain) for the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, respectively.[23] However, in his Geography, he referred to both Alwion (Great Britain) and Iwernia (Ireland) as a nēsos Bretanikē, or British island.[24]

- Marcian of Heraclea, in his Periplus maris exteri, described the island group as αί Πρεττανικαί νήσοι (the Prettanic Isles).[25]

- Stephanus of Byzantium used the term Ἀλβίων (Albion) to refer to the island, and Ἀλβιώνιοι (Albionioi) to refer to its people.[26]

- Pseudo-Aristotle used nēsoi Brettanikai, Albion and Ierne to refer to the island group, Great Britain, and Ireland, respectively.[27]

- Procopius, in the 6th century AD, used the terms Brittia and Brettania though he considered them to be different islands, the former being located between the latter and Thule. Moreover, according to him on Brittia lived three different nations, the homonymous Brittones (Britons), the Angiloi (English) and the Phrissones (Frisians).[28][29]

As seen above, the original spelling of the term is disputed. Ancient manuscripts alternated between the use of the P- and the B-, and many linguists believe Pytheas’s original manuscript used P- (Prettania) rather than B-. Although B- is more common in these manuscripts, many modern authors quote the Greek or Latin with a P- and attribute the B- to changes by the Romans in the time of Julius Caesar;[30] the relevant, attested sometimes later, change of the spelling of the word(s) in Greek, as is also sometimes done in modern Greek, from being written with a double tau to being written with a double nu, is likewise also explained by Roman influence, from the aforementioned change in the spelling in Latin.[31] For example, linguist Karl Schmidt states that the «name of the island was originally transmitted as Πρεττανία (with Π instead of Β) … as is confirmed by its etymology».[32]

According to Barry Cunliffe:

- It is quite probable that the description of Britain given by the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC derives wholly or largely from Pytheas. What is of particular interest is that he calls the island «Pretannia» (Greek «Prettanikē»), that is «the island of the Pretani, or Priteni». «Pretani» is a Celtic word that probably means «the painted ones» or «the tattooed folk», referring to body decoration – a reminder of Caesar’s observations of woad-painted barbarians. In all probability the word «Pretani» is an ethnonym (the name by which the people knew themselves), but it remains an outside possibility that it was their continental neighbours who described them thus to the Greek explorers.[33]

Roman period[edit]

Following Julius Caesar’s expeditions to the island in 55 and 54 BC, Brit(t)an(n)ia was predominantly used to refer simply to the island of Great Britain[citation needed]. After the Roman conquest under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43, it came to be used to refer to the Roman province of Britain (later two provinces), which at one stage consisted of part of the island of Great Britain south of Hadrian’s wall.[34]

Medieval[edit]

In Old English or Anglo-Saxon, the Graeco-Latin term referring to Britain entered in the form of Bryttania, as attested by Alfred the Great’s translation of Orosius’ Seven Books of History Against the Pagans.[35]

The Latin name Britannia re-entered the language through the Old French Bretaigne. The use of Britons for the inhabitants of Great Britain is derived from the Old French bretun, the term for the people and language of Brittany, itself derived from Latin and Greek, e.g. the Βρίττωνες of Procopius.[28] It was introduced into Middle English as brutons in the late 13th century.[36]

Modern usage[edit]

There is much conflation of the terms United Kingdom, Great Britain, Britain, and England. In many ways accepted usage allows some of these to overlap, but some common usages are incorrect.

The term Britain is widely used as a common name for the sovereign state of the United Kingdom, or UK for short. The United Kingdom includes three countries on the largest island, which can be called the island of Britain or Great Britain: these are England, Scotland and Wales. However the United Kingdom also includes Northern Ireland on the neighbouring island of Ireland, the remainder of which is not part of the United Kingdom. England is not synonymous with Britain, Great Britain, or United Kingdom.

The classical writer, Ptolemy, referred to the larger island as great Britain (megale Bretannia) and to Ireland as little Britain (mikra Brettania) in his work, Almagest (147–148 AD).[37] In his later work, Geography (c. 150 AD), he gave these islands the names[38] Ἀλουίωνος (Alwiōnos), Ἰουερνίας (Iwernias), and Mona (the Isle of Anglesey), suggesting these may have been native names of the individual islands not known to him at the time of writing Almagest.[39] The name Albion appears to have fallen out of use sometime after the Roman conquest of Great Britain, after which Britain became the more commonplace name for the island called Great Britain.[9]

After the Anglo-Saxon period, Britain was used as a historical term only. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) refers to the

island of Great Britain as Britannia major («Greater Britain»), to distinguish it from Britannia minor («Lesser Britain»), the continental region which approximates to modern Brittany, which had been settled in the fifth and sixth centuries by Celtic migrants from the British Isles.[40] The term Great Britain was first used officially in 1474, in the instrument drawing up the proposal for a marriage between Cecily the daughter of Edward IV of England, and James the son of James III of Scotland, which described it as «this Nobill Isle, callit Gret Britanee». It was used again in 1603, when King James VI and I styled himself «King of Great Britain» on his coinage.[41]

The term Great Britain later served to distinguish the large island of Britain from the French region of Brittany (in French Grande-Bretagne and Bretagne respectively). With the Acts of Union 1707 it became the official name of the new state created by the union of the Kingdom of England (which then included Wales) with the Kingdom of Scotland, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain.[42] In 1801, the name of the country was changed to United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, recognising that Ireland had ceased to be a distinct kingdom and, with the Acts of Union 1800, had become incorporated into the union. After Irish independence in the early 20th century, the name was changed to United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is still the official name. In contemporary usage therefore, Great Britain, while synonymous with the island of Britain, and capable of being used to refer politically to England, Scotland and Wales in combination, is sometimes used as a loose synonym for the United Kingdom as a whole. For example, the term Team GB and Great Britain were used to refer to the United Kingdom’s Olympic team in 2012 although this included Northern Ireland. The usage ‘GBR’ in this context is determined by the International Olympic Committee (see List of IOC country codes) which accords with the international standard ISO 3166. The internet country code, «.uk» is an anomaly, being the only Country code top-level domain that does not follow ISO 3166.

See also[edit]

- Glossary of names for the British

- Terminology of the British Isles

- Hibernia

- Cruthin

- Prydain

- Pytheas

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Britain». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Chadwick, Hector Munro, Early Scotland: The Picts, the Scots and the Welsh of Southern Scotland, Cambridge University Press, 1949 (2013 reprint), p. 68

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Chadwick 1949, pp. 66–80.

- ^ Maier 1997, p. 230.

- ^ Ó Cróinín 2005, p. 213

- ^ Dunbavin 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Oman, Charles (1910), «England Before the Norman Conquest», in Oman, Charles; Chadwick, William (eds.), A History of England, vol. I, New York; London: GP Putnam’s Sons; Methuen & Co, pp. 15–16,

The corresponding form used by the Brythonic ‘P Celts’ would be Priten … Since therefore he visited the Pretanic and not the Kuertanic Isle, he must have heard its name, when he visited its southern shores, from Brythonic and not from Goidelic inhabitants.

- ^ a b Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ Book I.4.2–4, Book II.3.5, Book III.2.11 and 4.4, Book IV.2.1, Book IV.4.1, Book IV.5.5, Book VII.3.1

- ^ Βρεττανική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book I. Chapter IV. Section 2 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter II. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Strabo’s Geography Book IV. Chapter IV. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia Book IV. Chapter XLI

Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. - ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, lemma Britanni II.A at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Gaius Valerius Catullus’ Carmina Poem 29, verse 20,

Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. See also Latin text and its English translation side by side at Wikisource. - ^ Gaius Valerius Catullus’ Carmina Poem 45, verse 22, Latin text and

English translation

at the Perseus Project. See also Latin text and its English translation side by side at Wikisource. - ^ Avienius’ Ora Maritima, verses 111–112, i.e. eamque late gens Hiernorum colit; propinqua rursus insula Albionum patet.

- ^ Orosius, Histories against the Pagans, VII. 40.4 Latin text at attalus.org.

- ^

Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 1

Greek text at the Perseus Project. - ^ Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 2

Greek text at the Perseus Project. - ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1898). «Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ’, κε’«. In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia (PDF). Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B.G.Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1843). «index of book II». In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia (PDF). Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. p. 59.

- ^ Marcianus Heracleensis; Müller, Karl Otfried; et al. (1855). «Periplus Maris Exteri, Liber Prior, Prooemium». In Firmin Didot, Ambrosio (ed.). Geographi Graeci Minores. Vol. 1. Paris. pp. 516–517. Greek text and Latin Translation thereof archived at the Internet Archive.

- ^ Ethnika 69.16, i.e. Stephanus Byzantinus’ Ethnika (kat’epitomen), lemma Ἀλβίων Meineke, Augustus, ed. (1849). Stephani Byzantii Ethnicorvm quae svpersvnt. Vol. 1. Berlin: Impensis G. Reimeri. p. 69.

- ^ Greek «… ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγιστοι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη, …», transliteration «… en toutoi ge men nesoi megistoi tynchanousin ousai dyo, Brettanikai legomenai, Albion kai Ierne, …», translation «… There are two very large islands in it, called the British Isles, Albion and Ierne; …»; Aristotle (1955). «On the Cosmos». On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos. D. J. Furley (trans.). William Heinemann LTD, Harvard University Press. 393b pp. 360–361 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Procopius (1833). «De Bello Gotthico, IV, 20». In Dindorfius, Guilielmus; Niebuhrius, B.G. (eds.). Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. Vol. Pars II Volumen II (Impensis Ed. Weberis ed.). Bonnae. pp. 559–580.

- ^ Smith, William, ed. (1854). «BRITANNICAE INSULAE or BRITANNIA». Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, illustrated by numerous engravings on wood. London: Walton and Maberly; John Murray. pp. 559–560. Available online at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Rhys, John (July–October 1891). «Certain National Names of the Aborigines of the British Isles: Sixth Rhind Lecture». The Scottish Review. XVIII: 120–143.

- ^ lemma Βρετανία; Babiniotis, Georgios. Dictionary of Modern Greek. Athens: Lexicology Centre.

- ^ Schmidt 1993, p. 68

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-967945-4.

- ^ Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ Sedgefield, Walter John (1928). An Anglo-Saxon Verse-Book. Manchester University Press. p. 292.

- ^ OED, s.v. «Briton».

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1898). «Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ’,κε’«. In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia (PDF). Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1843). «Book II, Prooemium and chapter β’, paragraph 12». In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia (PDF). Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. pp. 59, 67.

- ^ Freeman, Philip (2001). Ireland and the classical world. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-292-72518-3.

- ^ «Is Great Britain really a ‘small island’?». BBC News. 14 September 2013.

- ^ Jack, Sybil (2004). «‘A Pattern for a King’s Inauguration’: The Coronation of James I in England» (PDF). Parergon. 21 (2): 67–91. doi:10.1353/pgn.2004.0068. S2CID 144654775.

- ^ «After the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, the nation’s official name became ‘Great Britain'», The American Pageant, Volume 1, Cengage Learning (2012)

References[edit]

- Fife, James (1993). «Introduction». In Ball, Martin J; Fife, James (eds.). The Celtic Languages. Routledge Language Family Descriptions. Routledge. pp. 3–25.

- Schmidt, Karl Horst (1993), «Insular Celtic: P and Q Celtic», in Ball, Martin J; Fife, James (eds.), The Celtic Languages, Routledge Language Family Descriptions, Routledge, pp. 64–99

Look up Britain in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Further reading[edit]

- Koch, John T. «New Thoughts on Albion, Iernē, and the Pretanic Isles (Part One).» Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 6 (1986): 1–28. www.jstor.org/stable/20557171.

23 December 2017

Britain is an ancient name. Where does it come from?

What’s in a name?

Place names are more complex than they first appear. They can be geographical expressions which allow people to orient themselves physically and mentally in their surroundings. They can be mental ‘boxes’ that enable people to think about space and what happens within them or between them. Identity is bound up with place names and who is allowed to name what often shows how power is structured and negotiated between people, communities and identities. Creating place names can be collaborative, they can be a form of domination.

The history of the creation and use of the names of Britain, Scotland, Wales, Ireland and England reflect the nuanced meaning of names. This Briefing is part of a series that will explore all these shared and inextricably linked histories, changing terminologies and the still unresolved and politically charged question of what to call all ‘these islands’ together.

The Island of the Painted People?

The earliest recorded place names for the group of islands off the north east European coast are in the works of classical Greek and Roman authors. These islands were on the very far fringes of the known Mediterranean world; where the barbarians’ barbarians lived, a place of mist and mysteries; full of great potential wealth, fantastical creatures and strange peoples. Classical works of geography and history were meant to edify and entertain as much as they were there to inform.

The first report of islands in the far west which can be associated with Britain and Ireland are to be found in Herodotus, the Greek father of history, in the fifth century BCE. Herodotus wrote of islands known as the Cassiterides but of which he had no information beyond their name.1 Herodotus, The Histories, Bk3.115. Cassiterides translates as ‘Tin Islands from the Greek word for tin — kassiteros.

We owe the name of Britain to Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek explorer from present-day Marseille, who travelled to Britain in around 325BCE and recorded the local names of the places he visited. Unfortunately, Pytheas’s writings do not survive but they were widely used as a source by other ancient but desk-bound geographers such as the first-century BCE Greek author Diodorus Siculus who recorded one of the islands names as ‘Pretannike’.2 Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Bk5.21. Greek Prettanike. In classical Greek and Latin texts, the ‘p’ often turned to a ‘b’ becoming ‘Britannia’.3 Julius Caesar is the earliest recorded writer to use the ‘b’ spelling during his own account of his expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE. Caesar, The Gallic Wars, Bk4.20-37; Bk5.2-24. These invasions were important propaganda exercises launched with the intention of further boosting Caesar’s prestige in Rome for subduing peoples on the very far edge of the known world. But the original Greek p-spelling was a rendition of a local Celtic name for either a people living on the island or for the land itself, exactly what is unclear. ‘Pretani’, from which it came from, was a Celtic word that most likely meant ‘the painted people’.4 The Celtic languages on these islands are split into two separate but related families: P-Celtic (Welsh, Cornish and Breton) & Q-Celtic (Irish, Scots Gaelic & Manx). Pretani comes from the P-Celtic line and its longevity can be seen in the modern Welsh word for Britain, Prydain.

Mysterious Albion

‘Albion’ was another name recorded in the classical sources for the island we know as Britain. ‘Albion’ probably predates ‘Pretannia’. Indeed, ‘Albion’ may come from a ‘celticisation’ of a word used for these islands prior to the arrival of Celtic-speaking peoples and most likely derives from the Indo-European root word for hill or hilly, ‘alb-’ ‘albho-‘ for white, probably referring to the white chalk cliffs on Britain’s southern shore.5 Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003), pp. 12-13. Other similarly derived place names include the Alps, Albania, and the Apennines, lending credence to the hill theory though it is not conclusive. Although Albion was often used by classical writers (and others since) as a rhetorical flourish, Britannia won out in general usage probably because after the beginning Roman conquest in 43CE, the province on the island was named ‘Britannia’.

Some examples of classical writers:

• Strabo (1st century BCE): “Brettanike” 6 Strabo, Geography, Bk1.4.3, Bk4.2.1; Bk.4.4.1. Brettanike. Strabo had a very low opinion of Pytheas, calling him an “archfalsifier” (pseudistatos).

• Pliny the Elder (1st century CE): “Britannia insula” 7 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Bk4.102. “Ex adverso huius situs Britannia insula clara Graecis nostrisque monimentis”

• Marcian of Heraclea (4th century CE): “the Prettanic Islands” 8 Marcian of Heraclea, Periplus Maris Exteri, Bk1. Proeemium; Bk1.8, Bk2.Proeemium, Bk2.24, Bk2.27, Bk2.40, Bk2. 41-46. Hai Prettanikai nesoi.

What made Britain ‘Great’?

The word ‘Great’ becoming attached to ‘Britain’ comes from medieval practice and not the classical authors. This became a common practice in the twelfth century to distinguish the island of Britannia maior (Greater Britain) from Britannia minor (Lesser Britain), the other medieval Britain Brittany.9 David N. Dumville, ‘‘Celtic’ visions of England’ in Andrew Galloway (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture (Cambridge, 2011), p. 126. Brittany gained its name from the British migrants who moved there in the post-Roman period.

Brutus of Troy and Britain

The twelfth century was a period of great historical introspection with numerous writers reflecting on the past of Britain and its various peoples’ pasts. The most influential contribution to this debate was Geoffrey of Monmouth, one of the most successful mytho-historians, with his History of the Kings of Britain.10 Geoffrey of Monmouth, The history of the kings of Britain: an edition and translation of De Gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Britanniae), M.D. Reeve (ed.) and N. Wright (trans.), (Woodbridge, 2007). Geoffrey of Monmouth distinguished between Britannia Insula or Britannia meaning Britain and Britannia minor, lesser Britain for Brittany, 92.88, 96.235, 97.245 Alongside his famed contribution to what became Arthurian legend, Geoffrey provided a popular origin story for the name ‘Britain’. Geoffrey wrote of a ‘Brutus of Troy’, a grandson of Aeneas, a Trojan hero and ancestor of the Roman people, who came to Albion, slew the giants who lived here and founded a kingdom, which took its name from him, Britain. Although this tale lacked any historical basis, this was the most popularly believed explanation until well into the sixteenth century at least.11 Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013), pp. 8-16.

From Geographical Expression to Political Reality

The accession of James VI of Scotland to the English and Irish thrones in 1603 created the impetus for widespread use of ‘Great Britain’ as both a geographical expression and as a political entity. England and Scotland remained separate kingdoms but James VI and (now) I decided that at least he could combine the two together in his title, so called himself ‘King of Great Britain’.12 James VI & I, ‘By the King. A proclamation concerning the Kings Majesties Stile, of King of Great Britaine, & C. [Westminster 20 October 1604]’ in J.F. Larkin & P.L Hughes (eds.), Stuart Royal Proclamations. Vol. 1, Royal proclamations of King James I, 1603-1625 (Oxford, 1973), no. 45; Jenny Wormald, ‘James VI and I (1566-1625)’, Oxford Dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004). The use of ‘Great Britain’ to refer to the whole island of Britain, was strengthened by the Act of Union (1707), which created a new united ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’.13 Article I of the Act of Union (1707) The ‘Kingdom of Great Britain’ became the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’ after the Act of Union (1801) between ‘Great Britain’ and the ‘Kingdom of Ireland’.14 First Article of the Union with Ireland Act (1800) As with many other states, a term that had enjoyed a largely literary, aspirational and geographic expression, now became a ‘political’ reality. After the Irish Free State’s creation in 1922, the name changed to the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’. This kept the distinction between what was geographically ‘Great Britain’ and ‘Northern Ireland’ but which remained one political union.

The ever-changing meaning of Britain

Britain may be an ancient name but its meaning has changed over time for the inhabitants and newcomers to these islands. This continuous renewal and reinterpretation of the meaning and understanding of the name is a major reason for its survival. The name of Britain has been a resource from which the various peoples have used to make and remake new, diverse and dynamic identities over centuries of lived history. It has survived because it has proved useful. However, this constant reuse of a name has preserved an ancient Celtic dialectal name transliterated by an ancient Greek explorer from the south of France over two millennia ago.

NOTES

-

Herodotus, The Histories, Bk3.115. Cassiterides translates as ‘Tin Islands from the Greek word for tin — kassiteros.

-

Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, Bk5.21. Greek Prettanike.

-

Julius Caesar is the earliest recorded writer to use the ‘b’ spelling during his own account of his expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BCE. Caesar, The Gallic Wars, Bk4.20-37; Bk5.2-24. These invasions were important propaganda exercises launched with the intention of further boosting Caesar’s prestige in Rome for subduing peoples on the very far edge of the known world.

-

The Celtic languages on these islands are split into two separate but related families: P-Celtic (Welsh, Cornish and Breton) & Q-Celtic (Irish, Scots Gaelic & Manx). Pretani comes from the P-Celtic line and its longevity can be seen in the modern Welsh word for Britain, Prydain.

-

Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003), pp. 12-13.

-

Strabo, Geography, Bk1.4.3, Bk4.2.1; Bk.4.4.1. Brettanike. Strabo had a very low opinion of Pytheas, calling him an “archfalsifier” (pseudistatos).

-

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Bk4.102. “Ex adverso huius situs Britannia insula clara Graecis nostrisque monimentis”

-

Marcian of Heraclea, Periplus Maris Exteri, Bk1. Proeemium; Bk1.8, Bk2.Proeemium, Bk2.24, Bk2.27, Bk2.40, Bk2. 41-46. Hai Prettanikai nesoi.

-

David N. Dumville, ‘‘Celtic’ visions of England’ in Andrew Galloway (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture (Cambridge, 2011), p. 126.

-

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The history of the kings of Britain: an edition and translation of De Gestis Britonum (Historia Regum Britanniae), M.D. Reeve (ed.) and N. Wright (trans.), (Woodbridge, 2007). Geoffrey of Monmouth distinguished between Britannia Insula or Britannia meaning Britain and Britannia minor, lesser Britain for Brittany, 92.88, 96.235, 97.245

-

Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013), pp. 8-16.

-

James VI & I, ‘By the King. A proclamation concerning the Kings Majesties Stile, of King of Great Britaine, & C. [Westminster 20 October 1604]’ in J.F. Larkin & P.L Hughes (eds.), Stuart Royal Proclamations. Vol. 1, Royal proclamations of King James I, 1603-1625 (Oxford, 1973), no. 45; Jenny Wormald, ‘James VI and I (1566-1625)’, Oxford Dictionary of national biography (Oxford, 2004).

-

Article I of the Act of Union (1707)

- First Article of the Union with Ireland Act (1800)

Suggested Additional Reading

Linda Colley, Britons: forging the nation (rev. ed. London, 2009).

Linda Colley, Acts of Union and Disunion (London 2014).

Barry Cunliffe, The extraordinary voyage of Pytheas the Greek (London, 2002).

Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins (Oxford, 2013).

Christopher A. Snyder, The Britons (Oxford, 2003).

Please log in to create your comment

English[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (UK) IPA(key): /ˈbɹɪt.ən/, [ˈbɹɪt.n̩]

- (US) IPA(key): /ˈbɹɪt.ən/, [ˈbɹɪɾ.ᵊn̩], [ˈbɹɪʔ.ᵊn̩]

- Rhymes: -ɪtən

- Hyphenation: Brit‧ain

- Homophone: Briton

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English Breteyn, from Anglo-Norman Bretaigne, Bretaine, from Latin Brittannia, variant of Latin Britannia, from Britannī; reinforced by native Old English Breten, from the same Latin source. Ultimately from Proto-Brythonic *Prɨdėn (“Britain”) from *Pritanī (also compare *Prɨdɨn (“Picts”) from *Pritenī), attested to in Ancient Greek as Πρεττανική (Prettanikḗ), compare Welsh Prydain. Doublet of Brittany. More at Britto.

Proper noun[edit]

Britain (plural Britains)

- (loosely) The United Kingdom.

- The island of Great Britain, consisting of England, Scotland and Wales, especially during antiquity. [from 10th c.]

- (historical) Brittany. [from 13th c.]

- (in the plural) The British Isles.

- (historical) The British state and its dominions and holdings; the British Empire. [from 17th c.]

- (in the plural) The British Empire. [from 19th c.]

- 1874, The Times, 14 July 1874:

- The name of ‘Britain’ […] ought to answer every purpose, or if that be thought too condensed, it may be pluralized into ‘The Britains’.

- 1874, The Times, 14 July 1874:

Synonyms[edit]

- (island): Gramarye

[edit]

- Battle of Britain

- Breton

- Britannia

- British

- Briton, Britton

- Brittany

- Broken Britain

Descendants[edit]

- → Hawaiian: Pelekāne

- → Tokelauan: Peletānia

Translations[edit]

- Albanian: Britania f

- Amharic: ብሪታንያ (bəritanya)

- Arabic: بِرِيطانِيَا (ar) f (birīṭāniyā)

- Armenian: Բրիտանիա (Britania)

- Azerbaijani: Britaniya

- Belarusian: Брыта́нія f (Brytánija)

- Bengali: ব্রিটেন (briṭen), বিলাত (bn) (bilat)

- Bulgarian: Брита́ния f (Británija)

- Burmese: ဘိလပ် (my) (bhi.lap), ဗြိတိန် (bri.tin)

- Catalan: Gran Bretanya (ca) f (only full name is used for the island)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 不列顛/不列颠 (bat1 lit6 din1)

- Mandarin: 不列顛/不列颠 (zh) (bùlièdiān)

- Czech: Británie (cs) f

- Danish: Storbritannien (da) (only full name is used for the island)

- Dutch: Brittannië (nl) n

- Esperanto: Britio

- Estonian: Britannia (et)

- Faroese: Bretland n

- Finnish: Britannia (fi)

- French: Grande-Bretagne (fr) f (only full name is used for the island)

- Georgian: ბრიტანეთი (briṭaneti)

- German: Britannien (de) n

- Greek: Βρετανία (el) f (Vretanía)

- Ancient: Βρεττανία f (Brettanía)

- Hebrew: בְּרִיטַנְיָה (he) f (británya)

- Hindi: ब्रिटेन (hi) m (briṭen)

- Hungarian: Britannia (hu)

- Icelandic: Bretland (is) n

- Indonesian: Britania (id)

- Irish: an Bhreatain f

- Italian: Gran Bretagna (it) f (only full name is used for the island)

- Japanese: ブリテン (Buriten)

- Kazakh: Британия (Britaniä)

- Khmer: ប៊្រីតថេន (priittheen)

- Korean: 브리튼 (Beuriteun), 브리텐 (Beuriten) (North Korea)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: (please verify) بەریتانیا (berîtanya)

- Northern Kurdish: Brîtanya (ku)

- Kyrgyz: Британия (Britaniya)

- Lao: ບໍລິເຕນ (bǭ li tēn), ບຣິເຕນໃຫຍ່ (ba ri tēn nyai)

- Latin: Britannia (la) f

- Latvian: Britānija f

- Lithuanian: Britanija f

- Macedonian: Брита́нија f (Británija)

- Malay: Britania

- Maltese: Brittanja f

- Maori: Peretānia, Piritini

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: Британи (Britani)

- Occitan: Grand Bretanha (oc) f (only full name is used for the island)

- Old English: Breten f

- Pashto: برتانيه (ps) f (bartānya), برطانيه f (bartānya), بريتانيا f (britāniyā)

- Persian: بریتانیا (fa) (beritâniyâ), برطانیه (beretâniye) (obsolete)

- Polish: Brytania (pl) f

- Portuguese: Bretanha (pt) f

- Rapa Nui: Peretane

- Romanian: Britania (ro) f

- Russian: Брита́ния (ru) f (Británija)

- Scots: Breetain

- Scottish Gaelic: Breatainn f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: Брѝта̄нија f

- Roman: Brìtānija (sh) f

- Sicilian: Granni Britagna f, Britagna Granni f

- Sinhalese: බ්රිතාන්ය (britānya)

- Slovak: Británia f

- Slovene: Británija f

- Spanish: Gran Bretaña (es) f (only full name is used for the island)

- Tagalog: Bretanya

- Tajik: Британия (tg) (Britaniya), Бритониё (Britoniyo)

- Telugu: బ్రిటన్ (briṭan)

- Thai: บริเตน (brì-dteen)

- Turkish: Britanya (tr)

- Turkmen: Britaniýa

- Ukrainian: Брита́нія f (Brytánija)

- Urdu: برطانیہ m (bartānia)

- Uyghur: برىتانىيە (britaniye)

- Uzbek: Britaniya

- Vietnamese: đảo Anh (vi), Anh (vi)

- Welsh: Prydain (cy)

Etymology 2[edit]

From Latin Britannus (adjective and noun, plural Britannī), apparently from Brythonic (compare Old Welsh Priten).

Noun[edit]

Britain (plural Britains)

- (now rare, historical) An ancient Briton. [from 15th c.]

- 2002, L. C. Lambdin and R. T. Lambdin, Companion to Old and Middle English Literature, 2002, page 12:

- The Britains’ struggles with the Scots and Picts […] led to the Britains asking the Romans for help in constructing a great wall.

- 2002, L. C. Lambdin and R. T. Lambdin, Companion to Old and Middle English Literature, 2002, page 12:

Adjective[edit]

Britain (comparative more Britain, superlative most Britain)

- (obsolete) Briton; British. [16th–18th c.]

See also[edit]

- Great Britain

- the British Isles

- the United Kingdom

Further reading[edit]

Britain (placename) on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

Anagrams[edit]

- triabin

Skip to content

With all the talk about Brexit, I thought I would share the etymology of the word Britain with my followers. Doggerland was an area of land, now lying beneath the southern North Sea, that connected Great Britain to mainland Europe during and after the last Ice Age. It was then gradually flooded by rising sea levels around 6,500–6,200 BCE.

Etymonline records that Britt-os was the Celtic name for the inhabitants of Britain at the time of Jesus. In Greek they were recorded as Prittanoi, which is said to mean “tattooed people.

Granted the Brits of 2000 years ago may have been tattooed people, but this does not mean that the word BRIT meant tattoo. Most English words that start with BR- have something to do with bridges. A BRIDE is a BRIDGE and so is a BRIBE. A BROTHER is like a genetic BRANCH within a family. BROCCOLI is a branch-like vegetable. A BROOK is a small stream that BRANCHES off a larger river or stream.

This is not linguistic coincidence. This is the two lobes in the written letter B, representing the two lobes of the cheeks employed while making the B sound, playing out in spoken language and preserved for over 2ooo years!

In my opinion this BR sound has meant two – like BI does as well – since the Dawn of Speak, 100,000 years ago. So BRITAIN seems to mean BRIDGE TERRAIN, which is what it was. In fact the -TAIN in BRITAIN is the same -TAIN in MOUNTAIN, which obviously refers to a land area (that is mounded).

There would have been centuries of time when the land in what was Doggerland would have resembled a bridge area. S0 while I accept that the people in that area 2000 years ago were tattooed, I believe they named themselves for a word in their vocabulary that would have referred to the concept of a BRIDGE in their tongue and in most tongues in that general area back then. This is an example of CLC, Common Language Code, which you can learn more about in my book, Deciphering the English Code.

JosephAronesty@gmail.com — Joseph Aronesty attended University of Pennsylvania 1967-1971. Published songwriter and father of 5 sons. Discovered that English letters are hieroglyphs for a Stone Age language code that began about 100,000 years ago in Africa, derived from the body/sign language we used as hunters. His book «Deciphering the English Code» conveys this in a way one can understand. He is also one of the world’s ground level e-commerce pioneers.

View all posts by josephsword

Britain was the name made popular by the Romans when they came

to the British islands . But this name already existed long before

the Romans started their empire building.

The high price of tin in the Mediteranean forced some merchants

to make the sea trip to what is now Cornwall. When they returned

they were asked where they had been. The common response was to say

«I’ve been to islands of the painted people» They used this

description because the tribes in the southern parts of England

used to paint their skin to scare off enemies. In some mediteranean

languages «painted» was pronounced «Pitan»

Therefore » the land of the pitan people» through time and

Chinese wispers, became «Britain».

The name was brought back into use as Great Britain in 1707

following the unification of England and Scotland.

Even today you can spot the British men on the holiday beaches

of the Mediteranean heavily tattooed.

Isn’t history great.

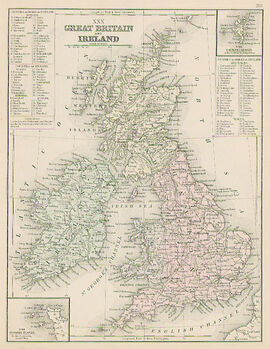

Map of Britain

Britain or Great Britain is a name used in various Arthurian texts 1.) for the island of Great Britain, 2.) for a kingdom approximately co-terminous with the Roman province of Britain, 3.) as an approximate synonym for England, 3.) and for the kingdom of Brittany in western Gaul.

Origins of the Name[]

Historical Speculation[]

Britain was visited and described by the Greek traveler Pytheas from whose material Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Ptolemy and others refer to the Pretanic Isles, in inhabited by the Pretani. In Old Welsh this is Priten. The corresponding form in Q-Celtic (Irish) is Cruithin which Irish writers use to refer to the people known in Latin as the Picti (‘Picts’, ‘Painted Ones’). The older Latin name was likewise Pretania.

Julius Caesar seems to have been responsible for introducing into Latin the forms Britanni for the island’s people and Britannia for the island, perhaps influenced by forms that the names took in the dialect of the Belgic Britons.

The etymology of the name is unknown.

Legendary Sources[]

The Britons are Named From Brutus[]

The Historia Britonum traces the name to one Brutus. Three versions are here given of Brutus’ origins.

In the first tale, Brutus was a descendant of Silvius Posthumus, a son whom Lavinia bore to Aeneas after Aeneas’ death. Brutus was consul when he first conquered Spain and reduced it to a Roman province. Brutus then conquered Britain which he named after himself.

The second version relates that Ascanius, the son whom Aeneas brought from Troy, was the father of Brutus who killed both his mother and father. For his mother died in giving birth to Brutus and Brutus killed his father Ascanius with an arrow by accident, for which reason Brutus was exiled. Brutus came to the islands of the Tyrrhene sea, but was exiled again by the people there, because he was grandson of Aeneas who had killed Turnus. Finally Brutus came to Britain which he named after himself.

The third version names Brutus as the son of Silvius, son of Ascanius, son of Aeneas. Silvius is here the father of two sons: Posthumus, from whom the Kings of Alba Longa descend, and Brutus, from whom the Britons descend.

Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae adopts the third origin, but also tells the story of how Brutus killed his father and mother, and was driven into exile.

The Britons Descend from Brutus son of Istaevone[]

Tacitus in his Germania states (as translated by Thomas Gordon):

In their old ballads (which amongst them are the only sort of registers and history) they celebrate Tuisto, a God sprung from the earth, and Mannus his son, as the fathers and founders of the nation. To Mannus they assign three sons, after whose names so many people are called; the Ingaevones, dwelling next the ocean; the Herminones, in the middle country; and all the rest, Istaevones. Some, borrowing a warrant from the darkness of antiquity, maintain that the God had more sons, that thence came more denominations of people, the Marsians, Gambrians, Suevians, and Vandalians, and that these are the names truly genuine and original.

A document traditionally (but incorrectly) known as The Frankish Table of Nations lists descendants of the three sons of Mannus. This is found in various versions in which Mannus is corrupted to Alanus, possibly because the author knew of the people called the Alans. A version of this table appears in the Historia Brittonum. It reads, with some corrections made in the English translation to more accurate, original forms or to better known forms

Aliud experimentum inveni de isto Bruto ex veteribus libris veterum nostrorum. tres filii Noe diviserunt orbem in tres partes post diluvium. Sem in Asia, Cham in Africa, Iafeth in Europa dilataverunt terminos suos. I have learned another account of this Brutus from the ancient books of our ancestors. The three sons of Noah, after the deluge, severally occupied three different parts of the earth: Shem in Asia, Ham in Africa, and Japheth in Europe extended his borders. Primus homo venit ad Europam de genere Iafeth Alanus cum tribus filius suis, quorum nomina sunt Hessitio, Armeno, Negue. The first man who came to dwell in Europe was Mannus, with his three sons, Istaevone, Herminone, and Yngaevone. Hessitio autem habuit filios quatuor: hi sunt Franeus, Romanus, Britto, Albanus. Istaevone had four sons, Francus, Romanus, Brutus, and Alemanus.(Alemanus has here been restored in the translation from continental versions in place of Albanus/Albinus. Albinus also appears instead of Alemanus in the Irish Lebor Gebala where he is said to have taken Albania, with his children, and given his name to Alba [an old Irish name for Britain] and to have driven his brother across the Sea of Icht, and to have given his name to the Albanians of Latium in Italy.) Armenon autem habuit quinque filios: Gothus, Valagothus, Gebidus, Burgundus, Langobardus. Herminone had five sons: Gothus, Valagothus, Gepidus, Burgundus, and Longobardus.(Valagothus seems to stand for ‘Welsh-Goth’, ‘Wala-/Vala-’ being used in Germanic languages to refer to all those whose native tongue was Latin or British. The Valagoths would be the Goths of Septamania and Spain who had adopted Latin. Negue autem habuit tres filios: Vandalus, Saxo, Bogarus. Yngaevone had three sons: Vandalus, Saxo, and Bavarus. ab Histione autem ortae sunt quattuor gentes: Franci, Latini, Albini et Britti. From Istaevone arose four nations: the Franks, the Latins, the Alemans (Germans), and Britons. (In the translation Alemans has been substituted for Albini following continental versions. The Albini would be the Picts.) ab Armenone autem quinque: Gothi, Valagothi, Gebidi, Burgundi, Longobardi. From Herminone: the Goths, Valagoths, Gepids, Burgundians, and Lombards. ab Neguio vero quattuor Boguarii, Vandali, Saxones et Turingi. From Yngaevone: the Bavarians, Vandals, Saxons, and Thuringians. istae autem gentes subdivisae sunt per totam Europam. The whole of Europe was subdivided into these tribes.

Alanus autem, ut auint, filius, fuit Fetebir, Mannus is said to have been the son of Fetebir, filii Ougomun, son of Ougomun, (The name Agnomain occurs in various locations in the genealogies of the Irish Lebor Gabala, in some cases as the son or grandson of Tat.) filii Thoi, son of Thoi, (From this point the genealogy follows the lineage of Gaidel Glas in the later Lebor Gabala, the line there being: Gaidel Glas, Nel, Fenius Farsaid, Eogan, Glunfhind, Lamfhind, Etheor, Thoe, Bodb, Sem, Mar, Aurthact, Aboth, Ara, Iara, Sru, Esru, Baath, Rifath Scot [this last being the Biblical Riphath of Gen. 10.3, Riphath there being son of Gomer, son of Japheth, son of Noah].) filii Boib, son of Boib, filii Simeon, son of Simeon, filii Mair, son of Mair, filii Ethach, son of Ethach, (The Lebor Gabala leaves Ethach out. See the note on Thoi, above.) filii Aurthach, son of Aurthach, filii Ecthet, son of Ecthet, (The Lebor Gabala leaves Ecthet out. See the note on Thoi, above.) filii Oth, son of Oth, (See the note on Thoi, above, and the note on Abir, following.) filii Abir, son of Abir, (The Lebor Gabala has “Aboth”. Either it has combined Abir and Oth or the Historia Brittonum version has created two persons from Aboth. See the note on Thoi, above.) filii Ra, son of Ra, (Sera, son of Sru, son of Esru appears in contradictory genealogies in the Irish Lebor Gabala.) filii Ezra, son of Ezra, (Sru, son of Esru appears in contradictory genealogies in the Irish Lebor Gabala.) filii Izrau, son of Izrau, (Esru appears in contradictory genealogies in the Irish Lebor Gabala. There he is in one place son of Bimbend, son of Magog, and in another place is son of Braimant, son of Aithect, son of Magog, and given other fathers in other places.) filii Baath, son of Baath, (Baath, son of Iobaath usually appears in genealogies in the Irish Lebor Gabala as Baath, son of Ibath, son of the Bilblical Gomer.) filii Iobaath, son of Iobaath, (Iobaath, is called Ibath in the Lebor Gabala which identifies him with Rifapth Scot. In another place Ibath is son of Magog son of Noah and father of Alanius father of Airmen, Negua, and Isicon.) filii Iovan, son of Javan, (Ionians, Greeks in Bible. Javan and all following names are from the Jewish/Christian Bible as in the genealogy in Genesis 10.) filii Iafeth, son of Japheth, filii Noe, son of Noah, filii Lamech, son of Lamech, filii Matusalae, son of Methuselah, filii Enoch, son of Enoch, filii Iareth, son of Jared, filii Malalehel, son of Malalehel, filii Cainan, son of Kenan, filii Enos, son of Enosh, filii Seth, son of Seth, filii Adam, son of Adam, filii dei vivi. son of the Living God. hanc peritiam inveni ex traditione veterum. We have obtained this information from ancient tradition. Qui incolae in primo fuerunt Brittanniae Brittones a Bruto. The Britons in Britain were thus first called from Brutus. Brutus filius Hisitionis Brutus was son of Istaevone, Histion Alanci, Istaevone of Mannus, Alanci filius Reae Silviae, Mannus son of Rhea Silvia, (Rhea Silvia bore Romulus and Remus to the god Mars in the common tradition. No source but this gives her any other children. And neither Romulus nor Remus are given children.) Rea Silvia filia Numae Pampilii, Rhea Silvia daughter of Numa Pompilius, (Rhea Silvia in Roman traditions was daughter of King Numitor of Alba Longa, a descendant of Ascanius. Numa Pompilius was another person entirely, elected to be the second King of Rome after Romulus vanished. The author appears to have inserted him in error for Numitor) filii Ascanii, son of Ascanius, filii Aeneae, son of Aeneas, filii Anchisae, son of Anchises, filii Troi, son of Troius, (In classical sources Anchises is son of Capys, son of Assaracus, son of Tros.) filii Dardani, son of Dardanus, (In classical sources Tros is son of Erichthonius, son of Dardanus.) filii Flise, son of Elishah, (The Latin form Flise is a corruption of the Biblical form Elishah. The Irish version of the Historia Brittonum makes Dardanus [Dardain] to be son of Iob [Jove], son of Sardain [Saturn], son of Ceil [Coelus ‘Sky’], son of Polloir [Tellus ‘Earth’], son of Zorastreis (Zoroaster), son of Mesraim (Egypt), son of Caim (Ham), son of Noe (Noah). filii Iuvani, son of Javan, filii Iafeth. son of Japheth. Iafeth vero habuit septem filios. Japheth indeed had seven sons: primus Gomer, a quo Galli; first Gomer, from whom the Gauls; secundus Magog, a quo Scythes et Gothos; second, Magog, from whom the Scythians and Goths; tertius Madai, a quo Medos; third, Madai, from whom the Medes; quartus Iuvan, a quo Graeci; fourth, Javan, from whom the Greeks; quintus Tubal, a quo Hiberei et Hispani et Itali; fifth, Tubal, from whom the Iberians, Spanish, and Italians; sextus Mosoch, a quo Cappadoces; sixth, Meshech, from whom the Cappadocians; septimus Tiras, a quo Traces. seventh, Tiras, from whom the Thracians. hi sunt filii Iafeth filii Noe filii Lamech. These are the sons of Japheth, the son of Noah, the son of Lamech.

Traditions of Prydein son of Aedd the Great[]

According to the medieval Welsh Names of the Island of Britain, Britain was originally named Clas Myrddin (‘Merlin’s Precinct’). After the island was seized and occupied, it was named Y Vel Ynys (‘The Island of Honey’). Only after it was conquered by Prydein son of Aedd the Great (Aedd Mawr), was it named Ynys Brydein (‘Island of Prydein’).

In some Welsh king lists based on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittaniae, Aedd Mawr and Prydein are inserted in place of Geoffrey’s Kinmarc, Gorboduc, and Porrex. The scholar Richard Vaughn left a note which refers to Aedd Mawr, Prince of Cornwall, and his son Prydein, who subdued the entire island which took its name from him. Vaughn places this conquest after the death of Porrex. The notice appears in Bromwich (2006, p. 484).

Great Britain and Little Britain[]

In French and in most European languages, in common usage during the late medieval period, Britain and related words was used primarily to refer to Brittany, or Little Britain. Its use to refer to England or even to the island of Britain was somewhat archaic in common speech. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae may be the first to use the term Britannia Major (‘Great Britain’) for the island of Britain to distinguish it from Britannia Minor (‘Little Britain’ or ‘Lesser Britain’) in France. In subsequent French literature the island of Britain is sometimes called “Bretaigne la Grant” as opposed to “Petite Bretaigne” or “Bretaigne la minor”. Where “Bretagne” occurs without modification, whether it refers to the island of Britain or to Brittany must be determined by context. Translations into English sometimes get this wrong.

Sometimes Great Britain, but never Little Britain, is called “Bretagne la Bloie”. “Bloie” now means “blue”, but seems to have also sometimes meant “green” in 12th and 13th century French, so a reference to Blue Britain brought to mind the greenness of the country compared to France.

Post-Medieval Official Use of Great Britain[]

The first use of “Great Britain” in official documents, as opposed to literary use, is in a proposal for a marriage between Cecily the daughter of Edward IV of England, and James the son of James III of Scotland, which described it as “this Nobill Isle, callit Gret Britanee”. In 1604, King James VI and I, proclaimed his assumption of the throne in the style «King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland …”. The Act of Union of 1707, states that England and Scotland shall “be united into one kingdom by the name of Great Britain”, making official what had hitherto been informal usage.

Welsh Use of Prydein[]

Prydein is the Welsh name for Britain, usually appearing as Ynys Prydein or Ynys Brydein meaning Island of Britain. When used without the initial “Ynys”, it usually refers to the territories of the British south of the land of the Picts and south of the lands of the Scots. That is, it refers to the countries of England and Wales. The northern regions of the island are called Prydyn, apparently in origin a version of the same name. Prydain is very rarely used for Little Britain in Welsh, which almost always used Llydaw as the name of the region. Accordingly a distinction between Great Prydein and Little Prydein is not needed.

Vagueness in Some Arthurian Texts[]

What is covered by the name Britain for Arthur’s kingdom remains somewhat vague in the texts. For example, in the Prose Tristan, Britain appears to be separate from Cornwall. People travel from Britain to Cornwall and from Cornwall to Britain.

Some Name Variations[]

Britain[]

FRENCH: Bretaigne, Bartaigne, Bertaigne, Bertaingne, Bretagne, Bretaige, Bretaing(g)ne, Bretrangne, Bretaygne, Bretei(n)gne; LATIN: Britannia; ENGLISH: Bruttene, Brutene, Brutaine, Bruttene, Brutene, Brutten, Bruttaine, Brutaine, Bruttaine, Brutlonde, Brutlond Brutlond, Britayne, Brutlodes, Bretayne, Bretayne, Bretaigne, Bretayn, Breteyn, Breteine, Bretein, Breotayne, Breteygne, Breteyne, Breteigne, Bretaygne, Breteigne, Brittaine, Bretaige, Bretten, Brettayn’, Bryttayne, Britane, Brittaine, Brytayne, Brutayne; MALORY: Brytayne, Bretayne; GERMAN: Bertâne, Bretâne, Britâne; DUTCH: Bertaenge, Bertaengie; NORSE: Bretlandi; SPANISH: Bretaña; PORTUGUESE: Bretanha, Bertanha; ITALIAN: Brettagna, Brectagna; WELSH: Prydein (Prydain).

Great Britain[]

FRENCH: Grant Bretaigne, Grant Bertaigne, Bretaigne la Grant; LATIN: Britannia Maior; ENGLISH: Gret(e) Breteygne, Gret(e) Bretayne, Breteyne the Gret(e), More Britayne, More Breteyne, Breteine þe More, Michel Breteyne, Mukyl Breotayne, Bretayn þe Brade, Bretayn the Brode, Bretayne þe Brodere; MALORY: Grete Bretayne; SPANISH: Gran Bretaña; PORTUGUESE: Gram Bretanha, Gram Bertanha; ITALIAN: Gran Brettagna, Grande Brettagna.

References[]

- Bartrum, P. C. (Ed.) (1966). Historia Brittonum. In Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts (pp. 5–8).

- Bromwich, Rachel (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein.

- Goffart, Walter A. (1989) “The Supposedly ‘Frankish’ Table of Nations: An Edition and Study”, Rome’s Fall and After, pp. 133–66, London, The Hambledon Press.

- Partial preview retrievable from http://books.google.ca/books?id=55pDIwvWnpoC&lpg=PA163&ots=Tr4jggo4Qi&dq=frankish%20table%20of%20nations&pg=PA133#v=onepage&q=frankish%20table%20of%20nations&f=false

- Hay, Denys, (1955–56), “The use of the term ‘Great Britain’ in the Middle Ages”, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, pp. 55-66