From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples

Asked by: Clotilde Olson

Score: 4.8/5

(41 votes)

Spoken word first kicked off with the American Beat Poet movement that took place in the 1940s and 1950s. This saw a group of authors in New York using their work to exploring and influence the American culture of the time.

How did spoken word or slam poetry originate?

The concept of slam poetry originated in the 1980s in Chicago, Illinois, when a local poet and construction worker, Marc Kelly Smith, feeling that poetry readings and poetry in general had lost their true passion, had an idea to bring poetry back to the people.

What is the history of spoken word poetry?

Spoken Word (n.):

A form of performance poetry that emerged in the last 1960’s. from the Black Arts movement. It owes its heritage most directly to the Beat Poetry of. the 1950’s and 1960’s and the Jazz Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance (1920-1940).

What’s the difference between spoken word and poetry?

“How is spoken word different from page poetry?” This question seems to have a pretty basic answer: one is written with the intention of being performed, or spoken aloud, while the other is written specifically for the page.

What purpose does spoken word serve in African American culture?

Spoken Word is often described as a place where the subaltern have a voice and are free to express issues of inequality, disadvantage, and oppression. Moreover, not only are these marginalized identities accepted, but they are celebrated and deemed as particularly authentic.

38 related questions found

Who is the best spoken word artist?

12 Powerful Spoken Word Artists You Need To Add To Your Playlist

- Alok Vaid-Menon (Preferred pronouns: they/them) …

- Uppa Tsuyo Bantawa (Preferred pronouns: he/him and she/her) …

- Andrea Gibson (Preferred pronouns: they/them) …

- Dr Abhijit Khandkar (Preferred pronouns: he/him) …

- Safia Elhillo (Preferred pronouns: she/her)

Is spoken word a talent?

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society.

Why is verbal speech of no use to the poet?

Verbal speech was of no use to the poet because poet could not speak .

What makes spoken poetry unique?

Spoken word performances require memorization, performative body language (like gestures and facial expressions), enunciation, and eye contact with viewers. Spoken word poetry is a form of poetry that doesn’t have to rhyme, but certain parts can be rhymed to emphasize an image or give it a lyrical quality.

What was the first spoken word?

Also according to Wiki answers,the first word ever uttered was “Aa,” which meant “Hey!” This was said by an australopithecine in Ethiopia more than a million years ago.

What year did spoken word originate?

In 1986, a construction worker in Chicago organized the very first event in the style of a poetry slam at a local jazz club.

Why is spoken word so powerful?

In this way, spoken word poetry empowers young people to become active agents in their own healing. It encourages cathartic expression and emotional processing that ultimately contributes to a more holistic pedagogical space. It fosters a culture of active listening.

Why is slam poetry hated?

The people I spoke to all said they found it annoying. They see it as very imitative, and that’s part of what’s annoying about it. People who work in this art form tend to place a lot of importance on honesty. It’s very autobiographical.

Who is Luka Lesson?

Luka Lesson is an Australian writer, spoken word performer and cultural changemaker of Greek heritage. … He is also the Australian Poetry Slam Champion of 2011 and Melbourne Poetry Slam Champion of 2010.

Who is a famous slam poet?

Beau Sia has quite a reputation in the poetry world. He is the winner of two National Poetry Slam Championships, and has been featured on all six seasons of the Def Poetry Jam.

What is the spoken word of God?

Rhema is the word which the Lord has spoken, and now He speaks it again.»

Do spoken words have to rhyme?

Spoken word is written on a page but performed for an audience. It relies on a heavy use of rhythm, improvisation, rhymes, word play, and slang. Spoken Word is writing that is meant to be read out loud. … Here are some spoken word poems from our Power Poets.

How do you present a poem on stage?

Tips:

- Present yourself well and be attentive. Use good posture. Be confident and make a direct connection with the audience.

- Nervous gestures and lack of confidence will detract from your score.

- Relax and be natural. Enjoy your poem—the judges will notice.

What are 5 examples of verbal communication?

Examples of Verbal Communication Skills

- Advising others regarding an appropriate course of action.

- Assertiveness.

- Conveying feedback in a constructive manner emphasizing specific, changeable behaviors.

- Disciplining employees in a direct and respectful manner.

- Giving credit to others.

- Recognizing and countering objections.

What are the difference between verbal and non verbal communication?

Verbal communication is the use of words to convey a message. Some forms of verbal communication are written and oral communication. Nonverbal communication is the use of body language to convey a message. One main form of nonverbal communication is body language.

What are verbal and non verbal communication?

When people ponder the word communication, they often think about the act of talking. … In general, verbal communication refers to our use of words while nonverbal communication refers to communication that occurs through means other than words, such as body language, gestures, and silence.

Who was the poet that won AGT?

Tonight on America’s Got Talent, spoken word poet Brandon Leake, who won season 15, returns for an encore performance, as will season 12 winner Darci Lynne, during the results show.

What happened to the poet that won AGT?

Leake now serves as producing partner and contributor to the Team Harmony Foundation’s new international web series, “Hate: What Are You Going to Do?” and has taken his work on the road in performances across the U.S. His AGT show winnings have enabled him to give up his “quote unquote ‘regular job’ ” and work full …

What was Brandon leaks talent?

Brandon Leake (born May 4, 1992) is a spoken word poet, educator and motivational speaker and the winner of the fifteenth season of America’s Got Talent. He was the first spoken word poet to be on America’s Got Talent and received the Golden Buzzer award in the first round from Howie Mandel.

What is spoken word Spotify?

Spotify today is launching a new feature that combines spoken word audio commentary with music tracks. The new format will allow Spotify to reproduce the radio-like experience of listening to a DJ or a music journalist offering their perspective on the music.

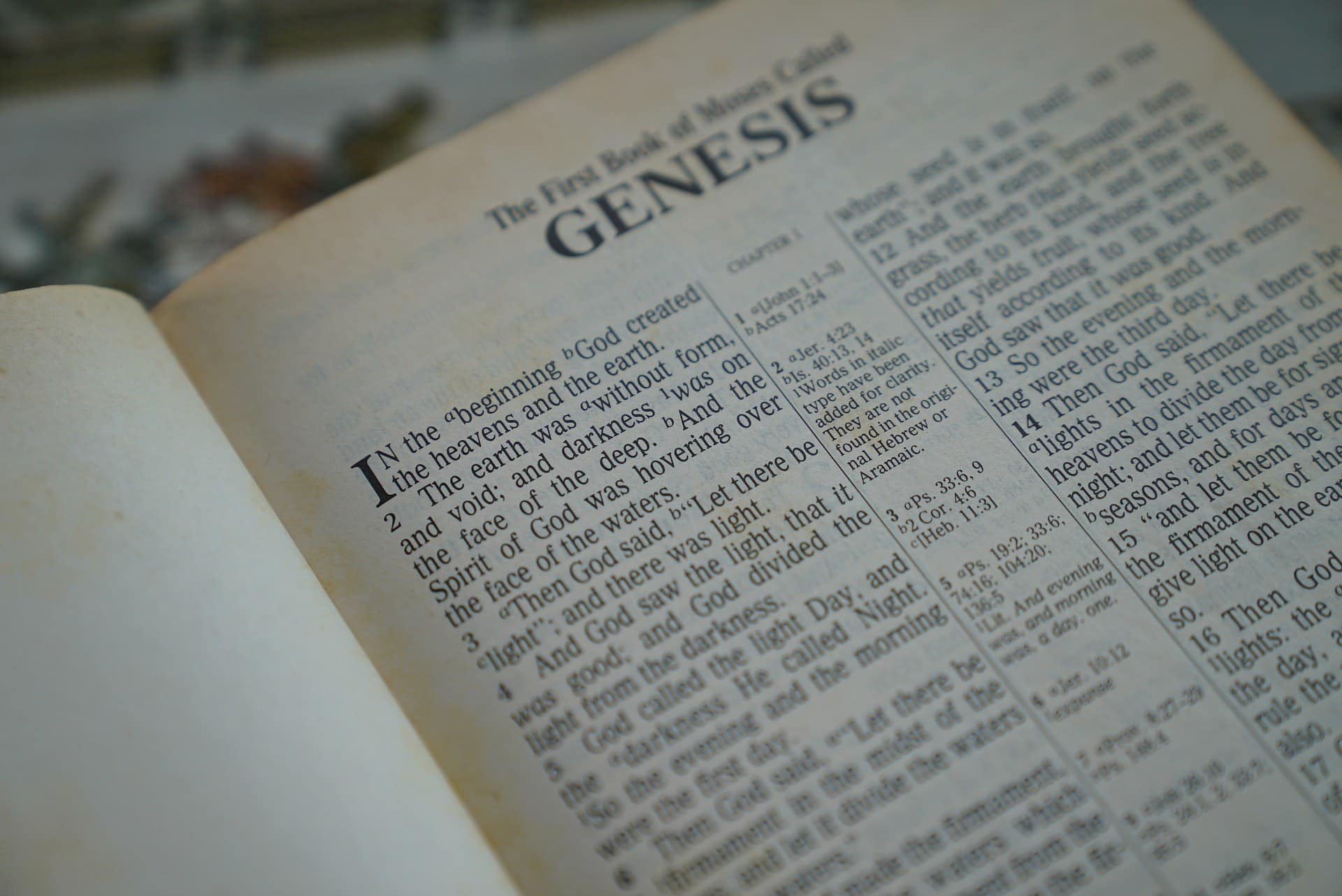

“In the beginning was the Word,” reads the Gospel of John 1:1. But what was this word? And where was it spoken? And how did humans come to speak it? Indeed, the origin of language is one of the greatest mysteries in human science, if not the greatest.

Scholars and scientists have been arguing for centuries about the origins of language and all the questions that tie into this. The Linguistic Society of Paris – an organisation dedicated to the study of languages – actually banned any debate on the issue in 1886 and did not retract it for several years. But why is it such a topic of debate?

Perhaps it’s because language is such a unique and complex skill. It is something that only humans are able to do. Over the years there have been numerous attempts to teach apes to speak, and in particular chimpanzees – which are human’s closest living relative. However, no other animal has the vocal pathology necessary to speak the way we do. Even attempting to teach chimps sign language has proven fruitless, with no animal demonstrating skill above the level of a two-year-old human. It seems the three things a creature needs to speak like a human is a human’s brain, a human’s vocal cords and a human’s intelligence.

Continuity or Discontinuity

Prior to the Linguistic Society of Paris’ ban on discussing it, the theories of how human language evolved were humorous to say the least. However, modern theories sit in one of two camps; Continuity or Discontinuity. Continuity theories of language evolution hold that it must have developed gradually, starting among the earliest ancestors of humans, with different features developing at different stages until people’s speech resembled what we have today. Meanwhile, Discontinuity Theory suggests that because there is nothing even remotely similar to compare human language to, and it is likely to have appeared suddenly within human history. This may have been as a result of a genetic mutation within one individual, which was passed on through their ancestors and eventually became a dominant ability.

Before we explore these theories in more detail, let’s look at some of the earliest ideas in the study of language origin.

From Bow-wow to Ta-ta

The early theories of the origin of language all focus on where the first words came from that developed into the rich vocabularies spoken today. They are certainly imaginative – and all have whimsical names to match. Max Müller, a philologist and linguist, published a list of these theories in the mid-19th century:

- Bow-wow

- Ding-Dong

- Pooh-pooh

- Yo-he-ho

Bow-wow was the theory that, much like the lyrebird, humans started out mimicking the noises and animal calls around them. From these noises, words developed. The Ding-dong theory is based on the idea of sound symbolism, and that small or sharp objects are named with words with high front vowels, compared to large or circular objects that have a round vowel at the end of the word. Pooh-pooh holds that the first words evolved from the natural verbal interjections humans make, such as exclaiming when surprised or yelping in pain. If Ye-he-ho makes you think of the Seven Dwarfs working in the gem mine, you’re not far off; it’s the theory that language started with the rhythmic noises made when doing manual labour, which allow muscle effort to synchronise.

Another early theory, albeit one not to appear on Müller’s list, was Ta-ta. This was the idea that primitive people used their tongues to mimic hand gestures and the words came from there. So, a person might wave their hand up and down to say good-bye and making the same movement with the tongue results in a “ta-ta” sound.

These are all fun theories, but each of them has been almost entirely discounted by today’s linguists and anthropologists.

In the beginning was the Word

Of course, the other earliest theory of language evolution is that it is a God-given ability. Genesis states that Adam and Eve, the first man and woman, were immediately able to understand what God said to them and could communicate with each other in this same language. According to Christianity, all of mankind spoke this one same language for generations more until the rebellion of Babel.

According to the Book of Genesis, as the waters of the Great Flood receded, humankind came together in Shinar. Here, they took advantage of the fact they all spoke one language by banding together to build a huge tower that would let them reach God in heaven. Seeing this, He confounded their speech by giving them different languages and then scattered them across the Earth. As a result, they were unable to work together to complete the tower.

As a nod to the story of the Tower of Babel, Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy includes a creature called the Babel fish. The yellow leech-like animal is able to act as a universal translator to enable creatures to communicate with one another.

If we could talk to the animals

What makes human speech even more miraculous is the fact that no other creature in history – that we know of – has evolved the skill. Not only do chimpanzees – our closest relatives – not speak now, but they may never speak as their vocal anatomy is so different to our own it would not facilitate human-like speech.

It’s not only our physical makeup that means we can talk and apes can’t but also our intelligence. In the 1960s, Project Washoe attempted to prove whether a chimpanzee could learn language. Washoe was a female common chimpanzee who was raised in a human family and taught American Sign Language. Not only did she learn 350 words, but she also taught some of it to her adopted son Loulis. A later experiment, Project Nim, attempted to go even further by getting more secure results proving that apes had linguistic abilities. Nim was named Nim Chimpsky in honour of Noam Chomsky, who conversely believes that only humans have the ability to develop speech. Ultimately, Project Nim ended up being less regimented than Project Washoe and the man leading it, Herbert S Terrace, abandoned it. He concluded that chimpanzees’ use of language was pragmatic and that they never developed the ability to use the signs syntactically.

Terrace not only abandoned his own research but also discredited other ape language studies, including Washoe. He said that the apes were using the signs to prompt the outcome they wanted and that a certain degree of mimicking was also occurring. He cited the case of Clever Hans; where large crowds would gather to watch a horse apparently correctly answer mathematical questions. It later transpired the horse was able to pick up and react to facial cues and body language his owner did not even realise he was making. If Terrace is right, it suggests apes and other animals do not have the brain function necessary to learn speech.

Is it all in the genes?

Noam Chomsky is among the world’s leading linguists and acknowledges that his field of expertise is home to some seemingly unsolvable mysteries; namely, where language came from and how. His theory is that a possible genetic mutation in one of our human ancestors gave them the ability to speak and understand language, which was passed on to their offspring. Because of the usefulness of this ability, Darwinist evolution meant that it became a dominant feature throughout humanity.

A UCLA/Emory study published in the journal Nature in 2009 seems to back up the theory. It revealed FOXP2, the gene essential to the development of language and speech, differs significantly depending on whether it is human or chimpanzee. Not only might this explain why the mutation of this gene results in language being disrupted, but also how we can talk and animals can’t. Dr Daniel Geschwind of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA said: “Earlier research suggests that the amino-acid composition of human FOXP2 changed rapidly around the same time that language emerged in modern humans.” The scientists discovered that the gene functioned and looked different in humans and chimps, and this difference meant a human brain was wired for language and a chimp’s was not. Could it be that an early mutation of this single gene is what ultimately separates us from all other life on Earth?

Another theory put forward by anthropologist Robin Dunbar is that as the human communities grew larger, people needed to find a more efficient form of grooming in order to keep their peers on their side. As a result, a type of vocal grooming developed – and it is likely these very early conversations would have been similar to the gossip we still indulge in today.

Of course, Chomsky’s theory is not the only possible answer to how language evolved. Many more experts follow the Continuity Theory that it evolved among human ancestors from pre-linguistic sounds. There are so many ideas within this field we don’t have time to list them all, but among them is the ‘putting the baby down’ hypothesis. Anthropologist Dean Falk suggests that as early humans lost their fur, it became more difficult for mothers to carry their babies on their backs as they gathered food and foraged. To reassure the baby she had not abandoned them, the mother would call to it and use facial expressions, body language and tactile communication like tickling. From this, Falk theorises language evolved.

So what’s the answer?

Unfortunately, it seems the answer to the question of where and how human language evolved is that we may never have an answer. However, it remains a problem we will never get tired of trying to resolve.

by Tom Thompson

In many ways the origins of spoken language remain the murkiest of all the important developments for our distant past. The ephemeral nature of speech means that we have nothing physical to excavate or examine, and no way to directly prove its existence.

It’s difficult to find biological components involved in speech. The hyoid bone – which allows the tongue and larynx to work together — gives a clue, but it’s attached to soft tissue so that as the body decomposes. The hyoid can shift position, or even disappear. The FOXP2 gene provides some clues to speaking ability. But the reach in time of sequence DNA across thousands of years is limited.

The Broca’s area of the brain (in the frontal lobe) is important, as is the Werniche’s area (in the temporal lobe). They seem to be responsible for the identification and subsequent sorting of incoming words. But all of these brain parts are internal, so that identifying them on a fossil-skull endocast is difficult.

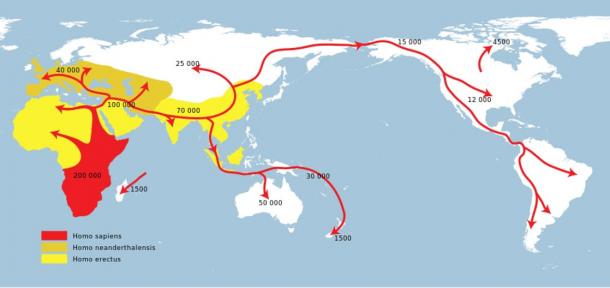

What even prompted the origins of speaking ability is similarly murky. Evolutionary biology and its focus on social learning and cumulative cultural adaptation have been instructive. Our ancestors, the Neanderthals and the Homo erectus, our immediate ancestors, were initially confined to small parts of the world. But when our species arose about 200,000 years ago, sometime after that, perhaps resulting from a sudden neurological change, we walked out of Africa and spread around the world, occupying nearly every habitat on Earth. And so we prospered in a way that no other animal has. Language really is the most potent trait that we have ever evolved.

A twist in our understanding of that trait is that we use our speaking ability, not just to cooperate, but also to draw rings around our cooperative groups and to establish identities, and perhaps to protect our knowledge and wisdom and skills from eavesdropping from outsiders. Two of the genius analysts in these areas are Mark Pagel of the University of Reading, the evolutionary biologist, and Professor Quentin Atkinson at the University of Auckland. Professor Atkinson is an expert at applying mathematical methods to linguistics. Together the two and their team have detected ancient signals that point to the origins of speech.

They’ve found a simple but striking pattern in some 500 languages spoken throughout the world. They’ve found that a language area uses fewer phonemes the farther that early humans had to travel from Africa to reach it. Some of the click-using languages of Africa have more than 100 phonemes, whereas Hawaiian, toward the far end of the human migration out of Africa, has only 13. English has about 45 phonemes. This pattern of decreasing diversity with distance, similar to the well-established decrease in genetic diversity with distance from Africa, implies that the origins of modern human language are the region of southwestern Africa.

The research is featured by the National Academy of Sciences in Ultraconserved words point to deep language ancestry across Eurasia. Professors Pagel and Atkinson looked not at words, but at phonemes – the consonants, vowels, and tones that are the simplest elements of language. They’ve come up with a list of two dozen or so “ultra-conserved words” that have survived the centuries. It includes some predictable entries: “mother,” “not,” “what,” “to hear,” “man,” etc. The existence of the long-lived words suggests that there was a “proto-Eurasiatic” language that was a common ancestor to about 700 contemporary languages that are the native tongues of more than half the world’s people. Wow!

About the writer

Tom Thompson writes frequently on foreign language topics. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Aritcles by Tom Thompson

- Arabic (العَرَبِيَّة)

- First Words

- Unlocking The World’s Oldest Language Mysteries

- Scientific Babel: Why English Rules

- Astrolinguistics: Is Anybody Out There?

- Basque: Not So Exotic, but Uniquely Interesting

- Child Language Acquisition: It’s Not Just Baby Talk

- Why is Spanish, well, Spanish?

- Italian: Not Just for Italians

- About Vietnamese

- Chinese Language Myths

- A Chinese Language Journey

- Black English in Washington, D.C.

- Why Korean Hangul (한글) is such an attractive written language

- About Pidgins and Creoles

- About MT, CT and Getting Lost in Translation

- On the Origin of Language

- The Challenge of Esperanto

- On Language, Thought, and Mind

- Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin — A Review

- Collecting Foreign Tongues

- Empires of the Word — A review

- Portuguese and Spanish: Some Musings

- Still Tongue-tied in America

- Studying Korean: The Surprising Joy-Ride of a New Language

- The Easy Thrills of a Difficult Language: Chinese For All of Us

- The Last Lingua Franca, English Until the Return of Babel — A Review

- The Silent Language of Ships at Sea

- Worlds Apart? The Deaf and Hard-of-hearing Learn Foreign Languages

Articles

Writing systems |

Language and languages |

Language learning |

Pronunciation |

Learning vocabulary |

Language acquisition |

Motivation and reasons to learn languages |

Arabic |

Basque |

Celtic languages |

Chinese |

English |

Esperanto |

French |

German |

Greek |

Hebrew |

Indonesian |

Italian |

Japanese |

Korean |

Latin |

Portuguese |

Russian |

Sign Languages |

Spanish |

Swedish |

Other languages |

Minority and endangered languages |

Constructed languages (conlangs) |

Reviews of language courses and books |

Language learning apps |

Teaching languages |

Languages and careers |

Being and becoming bilingual |

Language and culture |

Language development and disorders |

Translation and interpreting |

Multilingual websites, databases and coding |

History |

Travel |

Food |

Other topics |

Spoof articles |

How to submit an article

[top]

Why not share this page:

Learn languages for free on Duolingo

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or by contributing in other ways. Omniglot is how I make my living.

Note: all links on this site to Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk

and Amazon.fr

are affiliate links. This means I earn a commission if you click on any of them and buy something. So by clicking on these links you can help to support this site.

[top]

How human language began has been a question pestering researchers for centuries. One of the biggest issues with this topic is that empirical evidence is still lacking despite our great advances in technology. This lack of concrete evidence even once led to the prohibition of any future debates regarding the origins of communication by the Linguistic Society of Paris. Despite the obstacles, a number of researchers including psychologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, and linguists continue on studying the topic. The results of the numerous studies on early communication can be divided into two major categories of communication: vocalizations and gestures. Here the focus is on vocalization.

Our Hyoid Bones and Complex Brains: Part of What Helps Us Do More than Chatter Like Chimps

As spoken language is by nature impermanent, the best empirical evidence for this field of thought is the hyoid bone. This bone as it appears and functions in modern homo sapiens is only believed to be found in our predecessors, Homo heidelbergensis, as of 300,000 years ago and in our prehistoric «cousins» the Neanderthals. Nevertheless, the appearance of the Kebara 2 hyoid in both species does not definitively prove that they were set to use speech or complex language.

Bronze statue of male Homo heidelbergensis, Smithsonian Museum, Washington D.C., USA ( Tim Evanson/Flickr )

That being said, the hyoid bone is believed by many researchers to be the foundation of speech for humans and without our specifically shape hyoid bones in exactly the right place, functioning alongside a precisely descended larynx, it is believed that we would sound much like chimpanzees.

Image depicting the location of the hyoid bone and larynx in a modern human ( Lasaludfamiliar)

Thus, we had a nicely complex and precise throat anatomy, but alongside this part of the anatomy we also had to have sufficiently complex brains to have something to talk about. Researchers believe that our ancient ancestors had, what Noam Chomsky calls the LAD (Language Acquisition Device), the ability to learn language and to use it in a creative way. This creativity can be evinced by the art created some 300,000 to 700,000 years ago by our Paleolithic predecessors.

The oldest example of «art»: the cupule and meander design at Bhimbetka, India ( 290,000-700,000 BC) ( Collado Giraldo )

Hardware and Software in place: Ready To Begin?

Combining these two ideas, perhaps our human ancestors were all set to begin speaking (or at least making well-constructed sounds with a thought-out purpose) around 300,000 years ago. Despite this, most vocal theories say the date was much later — only 100,000 years ago when there was an increase in brain volume as well. This is a summary of the natural evolutionary acquisition of language.

- A Unique Form of Ancient Communication: The Whistling Island of La Gomera

- The Ancient Origins of Some Dead or Dying Languages

- In Search for a common origin in the world’s languages

Opposed to the evolutionary point of view, there is also debate on if language was a divine gift, or perhaps a conscious invention by early humans. Both of these theories are based on the complexity of human language.

The Creation of Adam (1511), Michelangelo ( Wikimedia Commons )

Apart from trying to pinpoint the date, continuity, and provider of the first spoken word, another very important question which scholars have tried to explain is: What did the early ancestors say?

The Early Theories on Vocal Language Origins: La-la, Bow-wow…

There are six principal theories that were made between the late 1800s to the early 1900s which were meant to explain the origins of the words used in vocal language. They have humorous nicknames attached which provide a hint into the idea behind the theory.

1. The Bow-Wow Theory: This theory suggests that the first words were onomatopoeic (words that use sounds associated with objects/actions they refer too) — such as hiss, bang and splash. The Bow-Wow theory has been discredited by the fact that many «onomatopoeic» words are different across languages, not really derived from natural sounds, and recently created.

2. The Ding-Dong Theory: is a theory that harmony with the natural environment created the need for language, and sound and meaning are innately connected through nature. While it is true that there are some examples of «sound symbolism» (fl- words in English associated with light and quick), studies have not been able to prove an innate connection between a sound and a words meaning.

Illustration of paleoindians during a burial. ( Earth Chronicles )

3. The Pooh-Pooh Theory: Suggests that language began with interjections (expressions such as «Ow!» «Oh!» «Ha!»). One problem with this theory is that it can be said that many animals make these/similar sounds yet they do not create other words. Another issue with the Pooh-Pooh theory is found in the lack of interjections currently found in most modern languages.

4. The Yo-He-Ho Theory: This is a theory based on the grunts and groans people make when doing heavy physical labor. While these sounds can be related to some of the rhythm of some language, it does not really explain the origins of most words.

5. The La-La Theory: Is an idea that vocal language came about through play, song, and love. A counterpoint is that the theory does not explain words that are less emotional.

6. The Ta-Ta Theory: believes that words arose from a desire to imitate gestures via the use of the tongue and mouth. For example, ta-ta would be a tongue waving goodbye. An obvious difficulty in this theory would be that many gestures could not be reproduced solely by the mouth and tongue.

Despite their drawbacks, most of these theories are still taught today as a starting point for research into the area of human speech.

- The Legendary Origins of the Chinese Language

- Neanderthal study reveals origin of language is far older than once thought

- Unravelling the Origins of Human Language

Expanding on the Ding-Dong Theory:

One recent study on the iconicity of both gestures and vocalizations as the origins of language suggests that there may be something to the concept of sound symbolism. In the study conducted by Perlman, Dale, and Lupyan they asked participants to create vocalizations for 18 different meanings (such as rough, small and fast). The participants then communicated these sounds to a partner who had to guess the meaning of the «word/sound.» They found that through repetition pairs were able to interpret the meanings of the vocalizations quickly and easily. Then the researchers played recordings of the vocalizations for people not present in the generation of sounds and here too they found that a higher percentage than by chance (36% correct) were able to interpret the meanings.

Conversation (1881) Camille Pissarro ( Wikimedia Commons )

Evolutionary Game Theory and Protolanguage

Nowak and Krakauer are two researchers who used game theory to try to explain the origins of language. As they believed that misunderstanding would be common in early language they created a model depicting this problem which limited the number of objects that could be described. Then they tried to find out how to get past the miscommunication. Their results show that increasing sounds did not help in passing the «error limit,» instead combining small sets of the sounds that could be understood created «words.»

One Original Language or Many?

Another issue plaguing researchers interested in the origins of vocal language is, was there one original language or many? Looking at the diversity of languages today, the dispersion of our ancient ancestors, studying modern language acquisition, and other factors have led to hypothesis on both sides: Monogenesis and Polygenesis.

The belief that there was one original language (monogenesis) is the older of the two theories. It has been proposed by believers that language was a divine creation. Monogenesis is also the preference of supporters of the Mother Tongue Theory — associated with the Out of Africa Theory (both based on one human evolutionary origin from Africa). The polygenesis theorists go against this singular origin based on the high number of languages that are spoken today as well as the diversity of location of the early ancestors.

Route and date of migration according to the Out of Africa Theory ( Wikimedia Commons )

As scholars have yet to provide concrete evidence of the first spoken word no one can be completely certain which of these theories is correct.

An Ancient Question with No Fossil Record

The fact is that we may never be able to explain definitively the origins of human vocal language. As Christine Kenneally said in her book The First Word: The Search for the Origins of Language (2007):

«For all its power to wound and seduce, speech is our most ephemeral creation; it is little more than air. It exits the body as a series of puffs and dissipates quickly into the atmosphere. . . . There are no verbs preserved in amber, no ossified nouns, and no prehistorical shrieks forever spread-eagled in the lava that took them by surprise.»

Featured Image: Cro-Magnon man communicating with each other and producing cave drawings (public domain).

By Alicia McDermott

References:

Collado Giraldo, H. (2012). » Primeras manifestaciones de arte rupestrepaleolítico: el final de las certidumbres .»

D’Anastasio R, Wroe S, Tuniz C, Mancini L, Cesana DT, et al. (2013) » Micro-Biomechanics of the Kebara 2 Hyoid and Its Implications for Speech in Neanderthals .» PLoS ONE Journal 8(12).

Dessalles, J-L. (n.d.) » The Brain From Top to Bottom: The Origins of Language .»

Harrub, B., Thompson, B., Miller, D. (2003) «The Origin of Language and Communication.»

Available at: http://www.trueorigin.org/language01.php

Holloway, A. (2014) » Neanderthal study reveals origin of language is far older than once thought .»

Kenneally, C. (2007) » The First Word: The Search for the Origins of Language .«

Langley, L. (2015) «Bonobo «Baby Talk» Reveals Roots of Human Language.»

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/08/150808-animals-bonobos-apes-evolution-speech/

Nowak, M. and Krakauer, D .(1999) «The Evolution of language.»

Available at: http://www.pnas.org/content/96/14/8028.full

Nordquist, R. (2015) «Where Does Language Come From? Five Theories on the Origin of Language»

Available at: http://grammar.about.com/od/grammarfaq/a/Where-Does-Language-Come-From.htm

Okrent, Arika. (n.d.) «6 Early Theories About the Origin of Language.»

Available at: http://mentalfloss.com/article/48631/6-early-theories-about-origin-language

Perlman, M. (2015) «Is This How Language Evolved?»

Available at: http://www.livescience.com/51766-is-this-how-language-evolved.html

Perlman, M., Dale, R., and Lupyan, G. (2015) «Iconicity can ground the creation of vocal symbols.» Royal Society of Open Science.

Available at: http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/2/8/150152

Vajda, E. (n.d.) «The Origin of Language.»

Available at: http://pandora.cii.wwu.edu/vajda/ling201/test1materials/origin_of_language.htm

Whipps, H. (2008) «How the Hyoid Bone Changed History.»

Available at: http://www.livescience.com/7468-hyoid-bone-changed-history.html

How human language was born is a question that has been tormenting researchers for centuries. One of the biggest obstacles in trying to answer it is that we still have no empirical evidence in spite of our great technological advances. This lack of concrete evidence even led at some point to the Linguistic Society of Paris to prohibit any debate about the origins of communication within it. Despite the unknowns, various researchers, including psychologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, and linguists, continue to study this issue. Consequently, the numerous studies on the birth of communication can be divided into two broad categories: vocalization and gestures. In this article, we will focus on vocalization. The origin of language summary

On what date did the language appear?

It is impossible to give an exact date to the origin of the language. Some of the most important data to be able to think about it are the following:

- 400,000 years ago, homo erectus would have already developed the Broca and Wernicke brain areas , related to the production and understanding of language respectively. Although it may be that he used them for other functions

- There are theories that place the origin of language with that of homo sapiens , which seems to have started its journey 50,000 years ago in Africa, after a severe ice age.

- Other authors propose a possible protolanguage , simpler, about 100,000 years ago .

Does the language come from a single language or from many different ones? The origin of language summary

This is one of the first questions to ask if we start to think about the origin of languages. We must imagine an initial state, in which the language developed, and we have two theories of the origin of language totally opposed:

- Monogenesis argues that the language arose with a first human group in Africa. That is, it maintains that there was a single original language that was fragmented into different languages later.

- Phylogenesis places the beginning of language beyond the origin of homo sapiens . According to this theory the language arises after the human being. And different languages arise in different nuclei around the planet.

So the first question to solve: there was only one protolanguage or the linguistic diversity comes from the beginning? The origin of language summary

Single words or sound blocks falling apart?

This is the last of the great questions regarding the origin of language. We imagine that our ancestors began to speak in single words (like fire or water , for example), but not all theories say this. We tend to identify ontogeny (the development of the child) with phylogeny (the development of the species).

That is, as children begin to speak using simple words with a clear referent, we believe that the first humans did the same .

However, some authors differ from these beliefs. They believe that human language developed through long groups of sounds that denoted specific situations.

That is, of prayers . Based on these sentences, according to this theory , the language was fragmented and the lexicon was generated, etc.

Which of the two positions is correct? That is already your decision, the one that convinces you the most!

In the end you may believe in one theory or another, but it seems difficult for us to get to know how and when language originated . The origin of language summary

In any case, this does not mean that the study in this field is not useful to us: looking for answers to such difficult questions will give us other partial answers .

[bctt tweet = »The #origenlanguage is anyone’s guess: in the end you may believe in one theory or another, but it seems difficult for us to get to know how and when language originated. # monogenesis # phylogenesis #wordblocks #loosewords »username =» on_translation »]

For example, studying the history of language we can foresee its future evolution, or understand our history through the lexical changes that have been taking place in a language . Or maybe we could invent a new common language to communicate with .

Our Hyoid Brain and Bone Complexes: Part of What Helps Us Do Something More Than Chatting Like Chimpanzees

Since spoken language is by its very nature somewhat transitory, the best empirical test in this field of study is the hyoid bone. This bone as it appears and works in modern Homo Sapiens is believed to only be found among the following among our predecessors: Homo Heidelbergensis, about 300,000 years ago, and our prehistoric “cousins” the Neanderthals. However, the appearance of the Kebara 2 hyoid in both species does not definitively prove that they were trained to make use of speech or complex language.

That said, many researchers believe that in the hyoid bone lies the birth of speech for humans and that without our hyoid bones with their specific shape and in the exact place, functioning alongside a larynx that has descended precisely, it is believed that the sounds that we would be able to emit would be very similar to those of chimpanzees. The origin of language summary

Therefore, we have wonderfully complex and precise anatomy in our throat, but along with this valuable part of our anatomy, we also need brains complex enough to have something to talk about. The researchers believe that our former ancestors already had what Noam Chomsky calls LAD (Language Acquisition Mechanism), the ability to learn a language and use it creatively. This creativity is evident in the art created between 300,000 and 700,000 years ago by our Paleolithic predecessors.

The Hardware and Software are already in place: Ready to Start?

Combining these two ideas, perhaps our human ancestors were already prepared to start talking (or at least to emit well-modulated sounds for the purpose of communicating some idea) about 300,000 years ago. Despite this, most speech theories pose a much later start date – only 100,000 years ago, when an increase in brain volume also took place. So far a summary of the evolutionary version of language acquisition.

- Aboriginal Languages Could Reveal Scientific Evidence of Australia’s Single Past

- Is the Text of the Danube Valley Civilization the Oldest Written in the World?

- Scientists Believe Having Discovered the Origins of the Unique Basque Culture

Opposite to the evolutionary point of view, there is also debate about whether language was a divine gift or perhaps a conscious invention by the first humans. Both theories are based on the complexity of human language.

Apart from trying to specify the date, continuity, and origin of the first word spoken by a human being, another very important question to which specialists have tried to answer is: What did our oldest ancestors say?

The Theories of Origins of Human Language

There are six main theories that were formulated between the early 19th and early 20th centuries that claim to explain the origins of the words we use in spoken language. They have funny names that allude to the idea that underlies each theory.

1. The Bow-Wow Theory

This theory suggests that the first words were onomatopoeic (words formed from the sounds related to the objects or actions to which they refer) such as gargling, cheating, whispering, or tic-tac. The Bow-Wow theory has been discredited by the fact that many “onomatopoeic” words are different depending on the language, they are not actually derived from the original sounds, and were recently created.

2. Ding-Dong Theory The origin of language summary

According to this theory, harmony with the natural environment gave rise to the need for language, and sounds and their meanings would be connected through nature immediately. Although it is true that there are examples of “phonetic symbolism” (for example, words that begin in English with fl- and are related to light and speed), the studies carried out have not been able to prove an innate connection between Phonetics and the meaning of a word. The origin of language summary

3. Pooh-Pooh theory

suggests that language was born thanks to interjections (expressions such as “Oh!”, “Oh!”, “Ha!”). A drawback of this theory is that it can be argued that many animals emit these sounds and others very similar and that is why they do not create words or even less a language. Another weakness of the Pooh-Pooh theory is the lack of interjections that occurs in most modern languages.

4. The Yo-He-Ho Theory

This is a theory based on the grunts and groans that the human being emits when he is doing some hard physical work. Although these sounds can be related to the part of the rhythm of some language, the theory cannot really explain the origin of most words.

5. La-La Theory

Consists of the idea that spoken language arose from play, singing, and love. An objection to this theory is that it does not explain the origin of other words with a less emotional charge.

6. Ta-Ta theory The origin of language summary

states that words arose from the desire to imitate gestures using the tongue and mouth. For example, the word Ta-Ta would be a language saying goodbye. The obvious difficulty of this theory is that many gestures cannot be represented solely by mouth and tongue.

Despite their failures, most of these theories are still taught today as a starting point for research in the area of spoken human language. The origin of language summary

- Our Ancient Ancestors Had More DNA than Us: Have We Involved?

- Top 10 Myths About Neanderthals

- Elfdaliano, the Old Viking Language of the Forests of Sweden, ready to be Recovered

Evolutionary Theory of Language and Protolanguage

Nowak and Krakauer are two researchers who used game theory to try to explain the origins of language. Believing that misunderstandings would be frequent at the beginning of spoken language, they created a model that described this problem and limited the number of objects that could be described. Then they tried to discover how to overcome possible communication failures. The results showed that a greater number of sounds did not help to overcome the “limit of errors”, but rather the creation of “words” by combining small groups of easy-to-interpret sounds. The origin of language summary

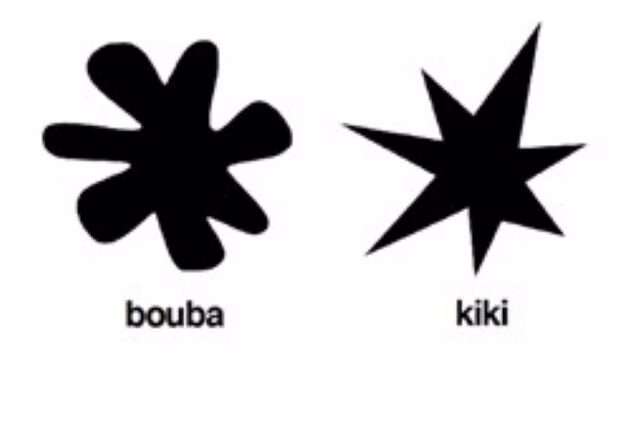

Most people around the world agree that the made-up word ‘bouba’ sounds round in shape, and the made-up word ‘kiki’ sounds pointy—a discovery that may help to explain how spoken languages develop, according to a new study.

Language scientists have discovered that this effect exists independently of the language that a person speaks or the writing system that they use, and it could be a clue to the origins of spoken words.

The research breakthrough came from exploring the ‘bouba/kiki effect,’ where the majority of people, mostly Westerners in previous studies, intuitively match the shape on the left to the neologism ‘bouba’ and the form on the right to ‘kiki.’

An international research team has conducted the largest cross-cultural test of the effect, surveying 917 speakers of 25 different languages representing nine language families and ten writing systems—discovering that the effect occurs in societies around the world.

Publishing their findings today in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, the team, led by experts from the University of Birmingham and the Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics (ZAS), Berlin, says that such iconic vocalizations may form a global basis for the creation of new words.

Co-author Dr. Marcus Perlman, Lecturer in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Birmingham, commented: «Our findings suggest that most people around the world exhibit the bouba/kiki effect, including people who speak various languages, and regardless of the writing system they use.»

«Our ancestors could have used links between speech sounds and visual properties to create some of the first spoken words—and today, many thousands of years later, the perceived roundness of the English word ‘balloon’ may not be just a coincidence, after all.»

The ‘bouba/kiki effect’ is thought to derive from phonetic and articulatory features of the words, for example, the rounded lips of the ‘b’ and the stressed vowel in ‘bouba,’ and the intermittent stopping and starting of air in pronouncing ‘kiki.’

To find out how widespread the bouba/kiki effect is across human populations, the researchers conducted an online test with participants who spoke a wide range of languages, including, for example, Hungarian, Japanese, Farsi, Georgian, and Zulu.

The results showed that the majority of participants, independent of their language and writing system, showed the effect, matching ‘bouba’ with the rounded shape and ‘kiki’ with the spiky one.

Co-author Dr. Bodo Winter, Senior Lecturer in Cognitive Linguistics at the University of Birmingham, commented: «New words that are perceived to resemble the object or concept they refer to are more likely to be understood and adopted by a wider community of speakers. Sound-symbolic mappings such as in bouba/kiki may play an important ongoing role in the development of spoken language vocabularies.»

Iconicity—the resemblance between form and meaning—had been thought to be largely confined to onomatopoeic words such as ‘bang’ and ‘peep,’ which imitate the sounds they denote. However, the team’s research suggests that iconicity can shape the vocabularies of spoken languages far beyond the example of onomatopoeias.

The researchers note that the potential for bouba/kiki to play a role in language evolution is confirmed by the evidence they collected. It shows that the effect stems from a deeply rooted human capacity to connect speech sound to visual properties, and is not just a quirk of speaking English.

More information:

Aleksandra Ćwiek et al, The bouba/kiki effect is robust across cultures and writing systems, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2021). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0390

Citation:

Perceptual links between sound and shape may unlock origins of spoken words (2021, November 16)

retrieved 14 April 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2021-11-perceptual-links-spoken-words.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Download Free PDF

Download Free PDF

The origins of language The Origins Of Human Speech

The origins of language The Origins Of Human Speech

The origins of language The Origins Of Human Speech

The origins of language The Origins Of Human Speech

Related Papers

1378843468 6083The Study Of Language (4th Edition(

Ermer Ventura

This page intentionally left blank

Gul S H A I R Baloch

The Study Of Language (4th Edition(.pdf

Ghayda W Saifi

linguistics the study og language

1.-The-Study-of-Language-2005_George-Jule.pdf

rania ran

The Study of Language

marzi mortazavi

(Yule) The Study of Language

MatJamine Ortiz

TEXT NOT MINE. I HOPE THIS HELPS TO YOU GUYS THO

Study of language by george yule

shreyas joshi

will known book

The Study of Language (4th Edition)

Vero Pardo

This page intentionally left blank The Study of Language

Rasa Mačiulytė

VIC TO RIA FROM KIN

Rizki Wijayanti