English word human being comes from English being, English human

Detailed word origin of human being

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| being | English (eng) | (obsolete) Given that; since. (obsolete) An abode; a cottage.. (philosophy) One’s basic nature, or the qualities thereof; essence or personality.. (philosophy) That which has actuality (materially or in concept).. A living creature.. The state or fact of existence, consciousness, or life, or something in such a state. |

| human | English (eng) | (comparable) Having the nature or attributes of a human being.. (notcomp) Of or belonging to the species Homo sapiens or its closest relatives. (rare) To behave as or become, or to cause to behave as or become, a human. A human being, whether man, woman or child. |

| human being | English (eng) | A person; a large sapient, bipedal primate, with notably less hair than others of that order, of the species Homo sapiens.. Another, extinct member of the genus Homo. |

Words with the same origin as human being

- Abkhaz: ауаҩы (awajʷə)

- Adyghe: цӏыфы (cʼəfə)

- Ainu: アイヌ (aynu)

- Albanian: njeri (sq) m

- Amharic: ሰው (säw)

- Arabic: إِنْسَان (ar) m (ʔinsān), نَاس pl (nās) (plural), بَشَر (ar) m (bašar), اِبْن آدَم m (ibn ʔādam) (literally: son of Adam), إِنْس m (ʔins)

- Aramaic:

- Hebrew: אנשא c (nāshā)

- Syriac: ܐܢܫܐ c (nāshā)

- Armenian: մարդ (hy) (mard)

- Assamese: মানৱ (manow)

- Avar: гӏадан (ʻadan), инсан (insan), чи (či)

- Aymara: jaqi (ay)

- Azerbaijani: insan (az), adam (az), kişi (az)

- Bashkir: кеше (keşe), әҙәм (äðäm), инсан (insan)

- Belarusian: чалаве́к (be) m (čalavjék), лю́дзі pl (ljúdzi) (plural)

- Bengali: মানুষ (bn) (manuś), মানব (bn) (manob)

- Bulgarian: чове́к (bg) m (čovék), хо́ра (bg) pl (hóra) (plural), лю́де pl (ljúde) (plural)

- Burmese: ပုဂ္ဂိုလ် (my) (pugguil), လူ (my) (lu)

- Buryat: хүн (xün)

- Central Sierra Miwok: míw·y-

- Chechen: стаг (stag), адам (adam)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 人類/人类 (zh) (rénlèi), 人 (zh) (rén)

- Chuvash: ҫын (śyn), этем (et̬em)

- Crimean Tatar: adam, insan

- Czech: člověk (cs) m, lidé (cs) pl (plural), lidská bytost f

- Dargwa: адам (adam), инсан (insan)

- Dhivehi: އިންސާނުން (in̊sānun̊)

- Eastern Mari: айдеме (ajdeme), еҥ (jeņ)

- Egyptian: (rmṯ)

- Finnish: ihminen (fi)

- French: être humain (fr) m, humain (fr) m, humaine (fr) f, homme (fr)

- Middle French: estre humain m

- Gagauz: insan, adam, kişi

- Galician: ser humano (gl) m

- Georgian: ადამიანი (ka) (adamiani), კაცი (ka) (ḳaci)

- German: menschliches Wesen n, Mensch (de) m

- Greenlandic: inuk

- Gujarati: મનુષ્ય (gu) (manuṣya), પુરુષ (gu) (puruṣ), માનવ m (mānav)

- Hawaiian: kanaka

- Hebrew: בֶּן אָדָם (he) m (ben ‘ádam) (literally, son of Adam), אָדָם (he) m (‘ádam)

- Hindi: मनुष्य (hi) m (manuṣya), इंसान m (insān), आदमी (hi) m (ādmī), मानव (hi) m (mānav)

- Hittite: 𒀭𒌅𒉿𒀪𒄩𒀸 c

- Indonesian: manusia (id), orang (id)

- Ingush: саг (sag)

- Interlingua: humano (ia), homine (ia), persona, esser human

- Inuktitut: inuk (iu) (inuk)

- Irish: duine (ga) m, neach daonna m

- Japanese: 人間 (ja) (にんげん, ningen), 人類 (ja) (じんるい, jinrui), 人 (ja) (ひと, hito)

- Kalmyk: күн (kün)

- Kannada: ಮಾನವ (kn) (mānava)

- Karachay-Balkar: адам (adam), киши (kişi)

- Karakalpak: adam, kisi

- Karelian: ihmine, mies

- Kashubian: człowiek m

- Kazakh: адам (kk) (adam), кісі (kısı)

- Khmer: ជគត (km) (ceaʔkʊət), មនុស្ស (km) (mɔnuh), ជន (km) (cɔɔn)

- Kikuyu: mũndũ class 1

- Komi-Permyak: морт (mort)

- Konkani: मनिषु (maniṣu)

- Korean: 사람 (ko) (saram), 인류(人類) (ko) (illyu)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: ئادەمیزاد (ckb) (ademîzad)

- Northern Kurdish: mirov (ku), meriv (ku)

- Kyrgyz: киши (ky) (kişi), адам (ky) (adam)

- Ladino: אומברי (ombre)

- Lak: инсан (insan), адимана (adimana)

- Lao: ມະນຸດ (lo) (ma nut), ຄົນ (lo) (khon), ບຸຣຸດ (bu rut)

- Latvian: cilvēks m

- Lezgi: инсан (insan), кас (kas)

- Lithuanian: žmogus (lt) m

- Lutshootseed: ʔaciɬtalbixʷ

- Macedonian: чо́век (mk) m (čóvek), лу́ѓе pl (lúǵe) (plural)

- Malay: manusia (ms), orang (ms)

- Malayalam: മനുഷ്യൻ (ml) (manuṣyaṉ)

- Maltese: bniedem m (literally: son of Adam)

- Manchu: ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠ (niyalma)

- Maore Comorian: mwanadamu class 1/2

- Maori: tangata (mi)

- Marathi: माणूस (māṇūs)

- Moksha: ломань (lomań)

- Mongolian: хүн (mn) (xün)

- Navajo: bílaʼashdlaʼii

- Occitan: òme (oc) m

- Old Church Slavonic: чловѣкъ m (člověkŭ)

- Ossetian: адӕймаг (adæjmag)

- Pashto: انسان (ps) (insān)

- Persian: آدمی (fa) (âdami), انسان (fa) (ensân), خاکزاد (fa) (xâkzâd)

- Plautdietsch: Mensch (nds) m

- Polish: człowiek (pl) m, ludzie (pl) pl (plural), istota ludzka f

- Portuguese: ser humano (pt) m, homem (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਇਨਸਾਨ (pa) (inasān)

- Romani: manuś m

- Russian: челове́к (ru) m (čelovék), лю́ди (ru) pl (ljúdi) (plural)

- Sanskrit: मनुष्य (sa) (manuṣya), मानव (sa) (mānava), जन (sa) m (jana)

- Scottish Gaelic: duine

- Serbo-Croatian: čeljade (sh) n, čeljad (sh) n pl

- Cyrillic: чо̏век m, чо̏вјек m, љу̑ди pl (plural)

- Roman: čȍvek (sh) m, čȍvjek (sh) m, ljȗdi (sh) pl (plural)

- Shona: murume

- Shor: кижи (kiji)

- Sicilian: omu (scn) m, uòmunu m

- Silesian: čowjek m

- Sindhi: اِنسانُ (sd) (insānu)

- Sinhalese: තැනැත්තා (tænættā), මිනිහා (minihā), මිනිසා (si) (minisā), පුරුෂයා (si) (puruṣayā)

- Slovak: človek (sk) m, ľudia (sk) pl (plural), ľudská bytosť f

- Slovene: člôvek (sl) m, ljudjé pl (plural)

- Somali: dad (so), aadame

- Sorbian:

- Upper Sorbian: čłowjek m

- Sotho: motho (st)

- Southern Altai: кижи (kiži)

- Spanish: ser humano (es) m

- Swahili: mwanadamu (sw), binadamu (sw)

- Tagalog: tao (tl)

- Tajik: одам (tg) (odam), инсон (tg) (inson)

- Tamil: மனிதன் (ta) (maṉitaṉ)

- Taos: t’óyna

- Tatar: кеше (tt) (keşe), инсан (tt) (insan), адәм (tt) (adäm)

- Telugu: మనిషి (te) (maniṣi), మగవాడు (te) (magavāḍu)

- Thai: คน (th) (kon), มนุษย์ (th) (má-nút)

- Tibetan: མི། (mi)

- Tocharian B: śaumo

- Turkish: insan (tr), insanoğlu (tr), âdemoğlu (tr) (literally, son of Adam), kişi (tr)

- Turkmen: ynsan, ynsaan, adam (tk), kişi

- Tuvan: кижи (kiji)

- Tzotzil: krixchano

- Udmurt: адями (aďami), мурт (murt)

- Ukrainian: люди́на (uk) f (ljudýna), лю́ди (uk) pl (ljúdy) (plural), чолові́к (uk) m (čolovík) (now usually means «man», «male human»)

- Urdu: انسان (ur) m (insān), آدمی (ur) m (ādmī), منشیه (manuṣya)

- Uyghur: ئىنسان (insan), ئادەم (ug) (adem)

- Uzbek: odam (uz), inson (uz), kishi (uz)

- Vietnamese: con người (vi), người (vi)

- Welsh: dyn (cy) m

- Wolof: nit (wo)

- Yakut: киһи (kihi)

- Yoruba: ènìyàn

- Zulu: umuntu (zu) class 1/2

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

any individual of the genus Homo, especially a member of the species Homo sapiens.

a person, especially as distinguished from other animals or as representing the human species: living conditions not fit for human beings; a very generous human being.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of human being

First recorded in 1855–60

Words nearby human being

Hulme, Hulse, hum, Humacao, human, human being, human body, human capital, human chorionic gonadotropin, humane, human ecology

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to human being

How to use human being in a sentence

-

Fossils suggest that human beings and apes shared a common ancestor as recently as 13 million years ago, and that whales, bats, and humans all shared parentage roughly 65 million years ago.

-

As decent human beings, we are supposed to be pleased by one another’s successes.

-

The experiments used one type of cotton mask and one type of medical mask in a laboratory, “not with human beings,” he said.

-

The crew and inhabitants of several starships led by the Galactica are the sole human beings stranded by the obliteration of their world at the hands of an artificial race that humans created to be slaves.

-

When you stop laughing and take a good look at what’s going on, you realize that the well-being of lots of non-famous, non-rich, non-publicity-seeking human beings is affected by this Wall Street madness.

-

Our animators are very excited to be drawing the innards of a human being.

-

What was this human being fighting for everywhere but inside a ring?

-

She assured me he was a decent human being and the love of her life.

-

But they gave themselves away with a very strange sentence—their only effort to acknowledge me as a human being.

-

Why not give her the opportunity to be an actual human being versus a celebrity?

-

Every human being behind that absurdly inadequate wall was exposed to constant and equal danger.

-

This, they said, was no human being like themselves; such hellish practices could have but one origin.

-

And every human being born upon the world represents a power of work that, rightly directed, more than supplies his wants.

-

Seven o’clock in the morning is too early for any rational human being to be herded into a factory at the call of a steam whistle.

-

As far as you know there isn’t a human being living who has any claim to your services by reason of blood relationship.

British Dictionary definitions for human being

noun

a member of any of the races of Homo sapiens; person; man, woman, or child

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

-

Defenition of the word human being

- A member of the human species.

- any living or extinct member of the family Hominidae

- any living or extinct member of the family Hominidae characterized by superior intelligence, articulate speech, and erect carriage

Synonyms for the word human being

-

- homo

- human

- man

Meronymys for the word human being

-

- arm

- earlobe

- foot

- genus Homo

- hand

- head of hair

- homo erectus

- hook

- human foot

- human head

- loin

- loins

- mane

- manus

- mauler

- mitt

- paw

Hyponyms for the word human being

-

- Homo erectus

- Homo habilis

- Homo rhodesiensis

- Homo sapiens

- Homo sapiens neanderthalensis

- Homo soloensis

- human beings

- human race

- humanity

- humankind

- humans

- man

- mankind

- Neandertal

- Neandertal man

- Neanderthal

- Neanderthal man

- Rhodesian man

- world

Hypernyms for the word human being

-

- creature

- hominid

See other words

-

- What is huckster

- The definition of meetinghouse

- The interpretation of the word medicine

- What is meant by mediastinum

- The lexical meaning meatloaf

- The dictionary meaning of the word meat pie

- The grammatical meaning of the word measure

- Meaning of the word meal

- Literal and figurative meaning of the word mead

- The origin of the word mercenary

- Synonym for the word merchant

- Antonyms for the word mere

- Homonyms for the word meritocrat

- Hyponyms for the word humanzee

- Holonyms for the word metafiction

- Hypernyms for the word metagenesis

- Proverbs and sayings for the word metal

- Translation of the word in other languages metallocene

- Dictionary

- H

- Human being

Transcription

-

- US Pronunciation

- US IPA

- UK Pronunciation

- UK IPA

-

- [hyoo-muh n or, often, yoo‐ bee-ing]

- /ˈhyu mən or, often, ˈyu‐ ˈbi ɪŋ/

- /ˈhjuːmən ˈbiː.ɪŋ/

-

- US Pronunciation

- US IPA

-

- [hyoo-muh n or, often, yoo‐ bee-ing]

- /ˈhyu mən or, often, ˈyu‐ ˈbi ɪŋ/

Definitions of human being words

- noun human being any individual of the genus Homo, especially a member of the species Homo sapiens. 1

- noun human being a person, especially as distinguished from other animals or as representing the human species: living conditions not fit for human beings; a very generous human being. 1

- noun human being person 1

- noun human being homo sapiens 1

- countable noun human being A human being is a man, woman, or child. 0

- noun human being a member of any of the races of Homo sapiens; person; man, woman, or child 0

Information block about the term

Origin of human being

First appearance:

before 1855

One of the 30% newest English words

First recorded in 1855-60

Historical Comparancy

Parts of speech for Human being

human being popularity

A pretty common term. Usually people know it’s meaning, but prefer to use a more spread out synonym. About 39% of English native speakers know the meaning and use word.

According to our data about 68% of words is more used. This is a rare but used term. It occurs in the pages of specialized literature and in the speech of educated people.

Synonyms for human being

noun human being

- person — a human being, whether an adult or child: The table seats four persons.

- soul — the principle of life, feeling, thought, and action in humans, regarded as a distinct entity separate from the body, and commonly held to be separable in existence from the body; the spiritual part of humans as distinct from the physical part.

- human — of, pertaining to, characteristic of, or having the nature of people: human frailty.

- mortal — subject to death; having a transitory life: all mortal creatures.

- earthling — an inhabitant of earth; mortal.

Antonyms for human being

noun human being

- animal — An animal is a living creature such as a dog, lion, or rabbit, rather than a bird, fish, insect, or human being.

- plant — any member of the kingdom Plantae, comprising multicellular organisms that typically produce their own food from inorganic matter by the process of photosynthesis and that have more or less rigid cell walls containing cellulose, including vascular plants, mosses, liverworts, and hornworts: some classification schemes may include fungi, algae, bacteria, blue-green algae, and certain single-celled eukaryotes that have plantlike qualities, as rigid cell walls or photosynthesis.

See also

- All definitions of human being

- Synonyms for human being

- Antonyms for human being

- Sentences with the word human being

- human being pronunciation

- The plural of human being

Matching words

- Words starting with h

- Words starting with hu

- Words starting with hum

- Words starting with huma

- Words starting with human

- Words starting with humanb

- Words starting with humanbe

- Words starting with humanbei

- Words starting with humanbein

- Words starting with humanbeing

- Words ending with g

- Words ending with ng

- Words ending with ing

- Words ending with eing

- Words containing the letters h

- Words containing the letters h,u

- Words containing the letters h,u,m

- Words containing the letters h,u,m,a

- Words containing the letters h,u,m,a,n

- Words containing the letters h,u,m,a,n,b

- Words containing h

- Words containing hu

- Words containing hum

- Words containing huma

- Words containing human

- Words containing humanb

Table of Contents

- What does the word mankind mean in Hebrew?

- What does the Greek word logos means?

- Where is the word woman derived from?

- Are cats related to dinosaurs?

- What animal did the cat evolve from?

- Did cats exist before humans?

- Why did cats stay close to humans?

The word human comes from the Latin word “humus,” meaning earth or ground.

What does the word mankind mean in Hebrew?

אדם, the Hebrew for “Human, Humanity”.

What does the Greek word logos means?

Logos – Longer definition: The Greek word logos (traditionally meaning word, thought, principle, or speech) has been used among both philosophers and theologians. In the New Testament, the phrase “Word (Logos) of God,” found in John 1:1 and elsewhere, shows God’s desire and ability to “speak” to the human.

Where is the word woman derived from?

The early Old English (OE) wif – from the Proto-Germanic wibam, “woman” – originally denoted a female, and later became the Middle English (ME) wif, wiif, wyf. By 1175 it was starting to be used to mean a married female, with the two meanings coexisting until the late 16th century.

The evolution of the domestic house cat is not as straightforward as you might expect. Twenty-first century science has illuminated some aspects of domestication, but lineages remain murky. In short, all cats probably evolved from the prehistoric proailurus, which was either the last cat precursor or the first cat.

What animal did the cat evolve from?

The domestic cat originated from Near-Eastern and Egyptian populations of the African wildcat, Felis sylvestris lybica. The family Felidae, to which all living feline species belong, arose about ten to eleven million years ago.

Did cats exist before humans?

In a new comprehensive study of the spread of domesticated cats, DNA analysis suggests that cats lived for thousands of years alongside humans before they were domesticated. Mice and rats were attracted to crops and other agricultural byproducts being produced by human civilizations.

Why did cats stay close to humans?

The researchers found that approximately 64 percent of the cats were securely attached to their owners, similar to what’s seen in dogs and babies. “The majority of cats are looking to their owners to be a source of safety and security,” Vitale said. “It’s important for owners to think about that.

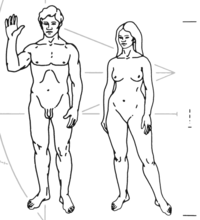

| Human Fossil range: Pleistocene — Recent |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Humans as depicted on the Pioneer plaque

|

||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Trinomial name | ||||||||||||||||

| Homo sapiens sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 |

In biological terms, a human being, or human, is any member of the mammalian species Homo sapiens, a group of ground-dwelling, tailless primates that are distributed worldwide and are characterized by bipedalism and the capacity for speech and language, with an erect body carriage that frees the hands for manipulating objects. Humans share with other primates the characteristics of opposing thumbs, omnivorous diet, five fingers (pentadactyl) with fingernails, and binocular, color vision. Humans are placed in the family Hominidae, which includes such apes as chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, as well as including such close, extinct relatives as Australopithecus, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus.

However, human beings not only define themselves biologically and anatomically, but also in psychological, social, and spiritual terms.

Psychologically, humans have a highly developed brain capable of abstract reasoning, language, and introspection. Humans also are noted for their desire to understand and influence the world around them, seeking to explain and manipulate natural phenomena through science, philosophy, mythology, and religion. Humans also have a marked appreciation for beauty and aesthetics, and can use art, music, and literature to express concepts and feelings. Their mental capability, natural curiosity, and anatomy has allowed humans to develop advanced tools and skills; humans are the only known species to build fires, cook their food, clothe themselves, and use numerous other technologies.

Humans are inherently social animals, like most primates, but are particularly adept at utilizing systems of communication for self-expression, the exchange of ideas, and organization. They create complex social structures of cooperating and competing groups, ranging in scale from small families and partnerships to species-wide political, scientific, and economic unions, including complex systems of governance. Social interactions between humans have also established an extremely wide variety of traditions, rituals, ethics, values, social norms, and laws that form the basis of human society. Their ability to appreciate beauty and aesthetics, combined with the human desire for self-expression, has led to cultural innovations such as art, literature and music. Humans are notable for practicing altruistic behaviors not only towards relatives, but also others, including sometimes enemies and competitors. Males and females form monogamous pair bonds and raise their young in families where both parents protect and educate the youngsters. Humans have extended parental care, and pass on many attributes socially to their young.

Spiritually, humans have historically formed religious associations, characterized by belief in God, gods, or spirits, and by various traditions and rituals. Many religious perspectives emphasize soul, spirit, qi, or atman as the essence of a human being, with many holding that this inner essence survives the death of the physical body. For many, it is this inner essence that explains the unique psychological and social aspects of humans and is the principle characteristic differentiating humans from other animals.

Humans as primates

Humans are classified in the biological order Primates, a group of mammals containing all the species commonly related to the lemurs, monkeys, and apes. Primates are characterized by being anatomically unspecialized, with limbs capable of performing a variety of functions, refined five-digit hands adapted for grasping (including opposable thumbs), comparatively flattened snouts, and prolonged pre and postnatal development, among other features. All primates have five fingers (pentadactyl) that are long and inward closing, short fingernails (rather than claws), and a generalized dental pattern. While opposing thumbs are a characteristic primate feature, this feature is not limited to this order; opossums, for example, also have opposing thumbs. Primates are omnivorous (generalized feeders that consume both animal protein and vegetation).

Primates are informally arranged into three groups: (1) prosimians, (2) monkeys of the New World, and (3) monkeys and apes of the Old World. Humans belong to the third group of primates, and specifically those primates known as apes. Apes are those primates placed in the superfamily Hominoidea of the same clade Catarrhini; the Old World monkeys are placed in the superfamily Cercopithecoidea in the clade, or parvorder, Catarrhini. Apes consist of the various species of gibbons (or «lesser apes»), as well as gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans, and humans (collectively referred to as the «great apes»).

From the point of view of superficial appearance, all living members of apes are tailless, while most Old World monkeys have tails. However, there are also primates in other families that lack tails. More specifically, the apes can be distinguished from the Old World monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars (apes have five—the «Y-5» molar pattern, Old World monkeys have only four in a «bilophodont» pattern). Apes have more mobile shoulder joints and arms, ribcages that are flatter front-to-back, and a shorter, less mobile spine compared to Old World monkeys.

A common taxonomic scheme divides the apes, or hominoids, into two families:

- The family Hylobatidae consists of 4 genera and 12 species of gibbons, collectively known as the «lesser apes»

- The family Hominidae consisting of gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and humans, collectively known as the «great apes»

Members of the family Hominidae are called hominids by many systematists. Since recent classification schemes for the apes place extinct and extant humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans in Hominidae, technically hominid refers to members of these groups. However, historically and even in some current classification schemes, Hominidae is restricted to humans and their close, extinct relatives—those more similar to humans than to the (other) great apes, which were placed in another family. Thus, there is a tradition, particularly in anthropology, of using the term hominid to refer only to humans and such forebears as Australopithecus, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus. In this sense, humans are considered the only surviving hominids.

Based on purely biological aspects (morphology, DNA, proteins, and so on), it is clear the humans are primates.

Indeed, humans and chimpanzees share more than 98 percent identity by various molecular comparisons (protein sequences, allele differences, DNA nucleotide sequences) (Wood 2006; King and Wilson 1975). Biologists believe that the two species of chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes and Pan paniscus, are the closest living evolutionary relatives to humans. The anatomical and biochemical similarity between chimpanzees and humans is so striking that some scientists even have proposed that the two chimpanzee species be placed with sapiens in the genus Homo, rather than in Pan. One argument for this suggested reclassification is that other species have been reclassified to belong to the same genus on the basis of less genetic similarity than that between humans and chimpanzees.

For example, Ebersberger et al. (2002) found a difference of only 1.24 percent when he aligned 1.9 million nucleotides of chimpanzee DNA and compared them with the corresponding human sequences in the human genome (Wood 2006). Using a 4.97 million nucleotide portion of DNA from human chromosome 7 and comparing to chimpanzee orthologies yielded only 1.13 percent mismatches (Liu et al. 2003). Likewise, a comparison of a rough draft of the chimpanzee genome—involving 361,782 contiguous fragments with a medium length of 15,700 nucleotides, covering about 94 percent of the chimpanzee genome—with the human genome, for those sequences that could be aligned, averaged 1.23 percent nucleotide mismatches (The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium 2005). Comparison of chimpanzee exons and human sequences yielded only 0.6 to 0.87 percent differences (Wildman et al. 2003; Nielsen et al. 2005). For a more detailed discussion of this, see Chimpanzees and humans.

Uniqueness of human beings

Because humans are classified as primates and because apes are considered to be our biological ancestors, there is a modern tendency to consider humans as «just another primate» or «nothing but an animal.» Indeed, the physical similarity between humans and other members of the «great apes» is so striking that efforts are underway to treat apes as «persons» with various human-like «rights.» (See cultural aspects of non-human apes.)

However, despite the remarkable physical similarity, the gulf between humans and other great apes (and other animals in general) is qualitatively huge, in terms of cultural, psychological (including emotional and mental characteristics), and spiritual aspects. Humans have a complex language, use symbols in communication, write and read books, have set up diverse systems of governance, have remarkable self-awareness, conduct scientific experiments, practice religious traditions, have developed complex technologies, and so forth. As noted by eminent evolutionist Ernst Mayr, «Man is indeed unique, as different from all other animals, as has been traditionally claimed by theologians and philosophers» (Mayr 2001).

Language, involving syntax and grammar, is one notably unique characteristics of humans. Other animals species that sometimes are said to have a «language»—such as the «language of bees»—merely have systems of giving and receiving signals; they lack a system of communication with syntax and grammar, which is required to properly be a language (Mayr 2001, p. 253). Thus, chimpanzees, despite decades of attempts to teach them language, cannot talk about the future or the past; they seem to lack the ability to adopt syntax (Mayr 2001).

Other animals have intelligence and think, including highly developed intelligence in various mammals and birds (corvids, parrots, and so on) (Mayr 2001). But human intelligence is greater by orders of magnitude. Humans have self-awareness, can reason abstractly, are capable of introspection, and appreciate beauty and aesthetics. They desire to understand the world, including both past, present, and future, and even study other animals and themselves. They have developed complex systems of governance and law, established sciences, and express feelings through art, music, and literature. They have developed complex technologies.

Human beings, unlike any other animals, transfer a great deal of cultural information, utilizing language in the process. Many animals, such as most invertebrates, do not even have any relationship with their parents, which die before their are hatched, and thus the parents do not transmit information to their offspring. Humans, on the other hand, form monogamous pair bonds and have extensive parental care, raising their young in families where both parents educate the youngsters.

However, even in species with highly developed parental care, such as in certain mammals and birds, the amount of information that is handed down from generation to generation (nongenetic information transfer) is quite limited (Mayr 2001, 253). For humans, there is a great deal of information that is transferred. Unlike chimpanzee young, which become independent of their mothers within the first year of life, human young require many years to reach maturity, during which the parents transmit language, culture, and skills that make up the greater part of human personhood. Information is even transferred by the use of symbols, and in written languages in books.

Humans beings also practice altruism, not only for the benefit of an individual’s own offspring, or the close relatives, or members of the same social group, but even towards outsiders and competitors or enemies. In chimpanzees, there is a practice of maiming or killing of former alpha males after they have been supplanted by a new leader. Human males, on the other hand, typically protect the children of other families of their tribe, and former male leaders are respected as honored elders. Respect for elderly males, codified in human morality as filial piety, is another means by which humans propagate and transmit culture.

Many religious hold that the most essential characteristic that makes humans unique is an immaterial essence: A soul, spirit, atman, qi, or so forth. It is this inner aspect that is considered to separate humans from animals. For example, there is a concept that humans have not only a physical body with physical senses, but also an immaterial or spiritual body with spiritual senses. This spiritual body is considered to mirror the appearance of the physical body, but also exists after the death of the material form. An example of such is found in the Bible: «It is sown a physical body, but it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body» (1 Corinthians 15:44).

Thus, although there are close anatomical similarities between humans and other primates, particularly chimpanzees, the gap between humans and apes in terms of culture, mental capacity, and various spiritual, emotional, and technological aspects is so large as to dwarf differences between apes and other animals. In this sense, philosophers have recognized humans as distinct from animals generally.

The name Homo sapiens is Latin for «wise human» or «knowing human,» emphasizing the importance of intelligence in separating humans and other animals. Mayr (2001) states that «it has long been appreciated that it is our brain that makes us human. Any other part of our anatomy can be matched or surpassed by a corresponding structure in some other animal.» However, many theologians and philosophers would emphasize the inner aspects of humans as the most distinctive factor, or emphasize the essence of humans in the ability to love.

Biology

Genetics and physiology

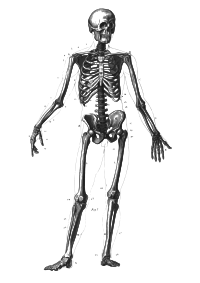

See also: Human body

An old diagram of a male human skeleton.

Humans are an eukaryotic species. Each diploid cell has two sets of 23 chromosomes, each set received from one parent. There are 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. By present estimates, humans have approximately 20,000–25,000 genes. Like other mammals, humans have an XY sex-determination system, so that females have the sex chromosomes XX and males have XY. The X chromosome is larger and carries many genes not on the Y chromosome, which means that recessive diseases associated with X-linked genes, such as hemophilia, affect men more often than women.

Human body types vary substantially. Although body size is largely determined by genes, it is also significantly influenced by environmental factors such as diet and exercise. The average height of an adult human is about 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 meters) tall, although this varies significantly from place to place (de Beer 2004). Humans are capable of fully bipedal locomotion, thus leaving their arms available for manipulating objects using their hands, aided especially by opposable thumbs.

Although humans appear relatively hairless compared to other primates, with notable hair growth occurring chiefly on the top of the head, underarms, and pubic area, the average human has more hair follicles on his or her body than the average chimpanzee. The main distinction is that human hairs are shorter, finer, and less heavily pigmented than the average chimpanzee’s, thus making them harder to see (Wade 2003).

Skin color, hair color, and «races»

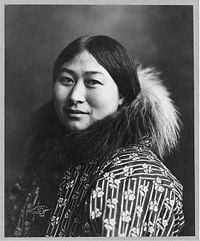

An Inuit woman, circa 1907.

The hue of human hair and skin is determined by the presence of pigments called melanins. Human skin hues can range from very dark brown to very pale pink, while human hair ranges from blond to brown to red to, most commonly, black (Rogers et al. 2004).

The differences in skin color between various people is due to one type of cell, the melanocyte. The number of melanocytes in human skin is believed to be the same for all people. However, the amount of pigment, or melanin, within the melanocytes is different. People with black skin have the most pigment and people with white skin have the least amount of pigment (Astner and Anderson 2004).

Many researchers believe that skin darkening was an adaptation that evolved as a protection against ultraviolet solar radiation, as melanin is an effective sun-block (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000). The skin pigmentation of contemporary humans is geographically stratified, and in general correlates with the level of ultraviolet radiation. Human skin also has a capacity to darken (sun tanning) in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation (Harding et al. 2000; Robins 1991).

Historically, efforts have been made to designate various human populations as distinct «races» based on skin color, along with such other observable physical traits as hair type, facial features, and body proportions. However, today many scientists from diverse fields, such as genetics, physical anthropology, sociology, and biology, believe that the concept of distinct human races is unscientific and that there are no distinct races as previously claimed (O’Campo 2005; Keita et al. 2004). The concept of «race» is a valid taxonomic concept in other species. However, in humans only a small proportion of the genetic variability of humans occurs between so-called races, there is much greater variability among members of a race than between members of different races, and racial traits overlap without discrete boundaries—making genetic differences among groups biologically meaningless (O’Campo 2005; Schwartz and Vissing 2002; Smedley and Smedley 2005; Lewontin 1972). In addition, so-called races are freely interbreeding. On the other hand, other geneticists argue that categories of self-identified race/ethnicity or biogeographic ancestry are both valid and useful (Risch et al. 2002; Bamshad 2005), and that arguments against delineating races could also be made regarding making distinctions based on age or sex (Risch et al. 2002).

Rather than delineating races, there is a current tendency to identify ethnic groups, with members defined by shared geographical origin or cultural history, such as common language and religion (O’Campo 2005), and there is a tendency to recognize a graded serious of differences (a cline) along geographical or environmental ranges.

The recognition of different races, along with preferences toward particular groups, or exploitation or domination of other groups, is sometimes identified with the term racism. From a biological point of view, in which species are recognized as actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, one might define someone as a «racist» on the basis of whether the person is willing to marry, and to have their children marry, someone of any other «race.» From a biblical point of view, all people are descended from one common pair of ancestors (O’Campo 2005).

From the point of view of some religions, the essential part of humans is the soul, which counters a fixation on physiology and observable physical characteristics alone (O’Campo 2005).

Life cycle

The human life cycle is similar to that of other placental mammals. New humans develop viviparously (live birth) from fertilization of an egg by a sperm (conception). An egg is usually fertilized inside the female by sperm from the male through sexual intercourse, though the recent technology of in vitro fertilization is occasionally used.

The fertilized egg, called a zygote, divides inside the female’s uterus to become an embryo that is implanted on the uterine wall. The fetal stage of prenatal development (fetus) begins about seven or eight weeks after fertilization, when the major structures and organ systems have formed, until birth. After about nine months of gestation, the fully-grown fetus is expelled from the female’s body and breathes independently as a «neonate» or infant for the first time. At this point, most modern cultures recognize the baby as a person entitled to the full protection of the law, though some jurisdictions extend personhood to human fetuses while they remain in the uterus.

Compared with that of other species, human childbirth can be dangerous. Painful labors lasting twenty-four hours or more are not uncommon, and may result in injury, or even death, to the child and/or mother. This is because of both the relatively large fetal head circumference (for housing the brain) and the mother’s relatively narrow pelvis (a trait required for successful bipedalism (LaVelle 1995; Correia et al. 2005). The chances of a successful labor increased significantly during the 20th century in wealthier countries with the advent of new medical technologies. In contrast, pregnancy and natural childbirth remain relatively hazardous ordeals in developing regions of the world, with maternal death rates approximately 100 times more common than in developed countries (Rush 2000).

In developed countries, infants are typically 3–4 kilograms (6–9 pounds) in weight and 50–60 centimeters (20–24 inches) in height at birth. However, low birth weight is common in developing countries, and contributes to the high levels of infant mortality in these regions (Khor 2003).

Helpless at birth, humans continue to grow for some years, typically reaching sexual maturity at 12 to 15 years of age. Human girls continue to grow physically until around the age of 18, and human boys until around age 21. The human life span can be split into a number of stages: infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, adulthood, and old age. The lengths of these stages, however, are not fixed, and particularly the later stages.

There are striking differences in life expectancy around the world, ranging from as high as over 80 years to less than 40 years.

The number of centenarians (humans of age 100 years or older) in the world was estimated at nearly half a million 2015 (Stepler 2016). At least one person, Jeanne Calment, is known to have reached the age of 122 years; higher ages have been claimed but they are not well substantiated. Worldwide, there are 81 men aged 60 or older for every 100 women of that age group, and among the oldest, there are 53 men for every 100 women.

The philosophical questions of when human personhood begins and whether it persists after death are the subject of considerable debate. The prospect of death causes unease or fear for most humans. Burial ceremonies are characteristic of human societies, often accompanied by beliefs in an afterlife or immortality.

Diet

Early Homo sapiens employed a «hunter-gatherer» method as their primary means of food collection, involving combining stationary plant and fungal food sources (such as fruits, grains, tubers, and mushrooms) with wild game, which must be hunted and killed in order to be consumed. It is believed that humans have used fire to prepare and cook food prior to eating since possibly the time of Homo erectus.

Humans are omnivorous, capable of consuming both plant and animal products. The view of humans as omnivores is supported by the evidence that both a pure animal and a pure vegetable diet can lead to deficiency diseases in humans. A pure animal diet can, for instance, lead to scurvy, while a pure plant diet can lead to deficiency of a number of nutrients, including Vitamin B12. Some humans have chosen to abstain from eating some or all meat for religious, ethical, ecological, or health reasons. Supplementation, particularly for vitamin B12, is highly recommended for people living on a pure plant diet.

The human diet is prominently reflected in human culture, and has led to the development of food science.

In general, humans can survive for two to eight weeks without food, depending on stored body fat. Survival without water is usually limited to three or four days, but longer periods are known, including fasting for religious purposes.

Lack of food remains a serious global problem, with about 300,000 people starving to death every year. Childhood malnutrition is also common and contributes to the global burden of disease (Murray and Lopez 1997). However global food distribution is not even, and obesity among some human populations has increased to almost epidemic proportions, leading to health complications and increased mortality in some developed, and a few developing countries. Obesity is caused by consuming more calories than are expended, with many attributing excessive weight gain to a combination of overeating and insufficient exercise.

At least ten thousand years ago, humans developed agriculture (see rise of civilization below), which has substantially altered the kind of food people eat. This has led to increased populations, the development of cities, and because of increased population density, the wider spread of infectious diseases. The types of food consumed, and the way in which they are prepared, has varied widely by time, location, and culture.

History

Origin of Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans)

The scientific study of human evolution concerns the emergence of humans as a distinct species. It encompasses the development of the genus Homo, as well as studying extinct human ancestors, such as the australopithecines, and even chimpanzees (genus Pan), which are usually classified together with genus Homo in the tribe Hominini. «Modern humans» are defined as the Homo sapiens species, of which the only extant subspecies is Homo sapiens sapiens.

There is substantial evidence for a primate origin of humans (Mayr 2001):

- Anatomical evidence: Human beings exhibit close anatomical similarities with the African apes, and particularly the chimpanzee. Compared to apes, the few unique physical characteristics of humans are the proportion of arms and legs, opposable thumbs, body hair, skin pigmentation, and size of the central nervous system, such as the forebrain.

- Fossil evidence: Numerous fossils have been found sharing human and primate characteristics.

- Molecular evidence: Human molecules are very similar to that of chimpanzees. In some, such as hemoglobin, they are virtually identical.

The closest living relatives of Homo sapiens are two distinct species of the genus Pan: the bonobo (Pan paniscus) and the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). Through a study of proteins, comparison of DNA, and use of a molecular clock (a method of calculating evolution based on the speed at which genes mutate), scientists believe thePan/Homo split happened about 5 to 8 million years ago (Mayr 2001, Physorg 2005). (See Pan/Homo split.)

Well-known members of the Homo genus include Homo habilis (about 2.4 to 1.5 mya), Homo erectus (1.8 mya to 70,000 years ago), Homo heidelbergensis (800,000 to 300,000 years ago), and Homo neanderthalensis (250,000 to 30,000 years ago).

H. sapiens have lived from about 250,000 years ago to the present. Between 400,000 years ago and the second interglacial period in the Middle Pleistocene, around 250,000 years ago, the trend in cranial expansion and the elaboration of stone tool technologies developed, providing evidence for a transition from H. erectus to H. sapiens. Based on molecular evidence, the calculation of the time of divergence of all modern human populations from a common ancestor typically yields dates around 200,000 years (Disotell 1999).

Notably, however, about 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, human beings appeared to have taken a Great Leap Forward, when human culture apparently changed at a much greater speed. Humans started to bury their dead carefully, made clothing out of hides, developed sophisticated hunting techniques (such as pitfall traps, or driving animals to fall off cliffs), and made cave paintings. Additionally, human culture began to become more technologically advanced, in that different populations of humans begin to create novelty in existing technologies. Artifacts such as fish hooks, buttons, and bone needles begin to show signs of variation among different population of humans, something what had not been seen in human cultures prior to 50,000 BP. This «Great Leap Forward» seems connected to the arrival of modern humans beings: Homo sapiens sapiens. (See modern man and the great leap forward.)

The Cro-Magnons form the earliest known European examples of Homo sapiens sapiens.

The term falls outside the usual naming conventions for early humans and is used in a general sense to describe the oldest modern people in Europe. Cro-Magnons lived from about 40,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic period of the Pleistocene epoch. For all intents and purposes these people were anatomically modern, only differing from their modern day descendants in Europe by their slightly more robust physiology and larger brain capacity than that of modern humans. When they arrived in Europe about 40,000 years ago, they brought with them sculpture, engraving, painting, body ornamentation, music, and the painstaking decoration of utilitarian objects.

Current research establishes that human beings are highly genetically homogeneous, meaning that the DNA of individual Homo sapiens is more alike than usual for most species. Geneticists Lynn Jorde and Henry Harpending of the University of Utah, noting that the variation in human DNA is minute compared to that of other species, propose that during the Late Pleistocene, the human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs—no more than 10,000 and possibly as few as 1,000—resulting in a very small residual gene pool. Various reasons for this hypothetical bottleneck have been postulated, one of those is the Toba catastrophe theory.

There are two major scientific challenges in deducing the pattern of human evolution. For one, the fossil record remains fragmentary. Mayr (2001) notes that no fossils of hominids have been found for the period between 6 and 13 million years ago (mya), the time when branching between the chimpanzee and human lineages is expected to have taken place. Furthermore, as Mayr notes, «most hominid fossils are extremely incomplete. They may consist of part of a mandible, or the upper part of a skull without face and teeth, or only part of the extremities.» Coupled with this is a recurrent problem that interpretation of fossil evidence is heavily influenced by personal beliefs and prejudices. Fossil evidence often allows a variety of interpretations, since the individual specimens may be reconstructed in a variety of ways (Wells 2000).

There are two dominant, and one might say polarizing, general views on the issue of human origins, the Out of Africa position and the multiregional position.

The Out of Africa, or Out of Africa II, or replacement model holds that after there was a migration of Homo erectus (or H. ergaster) out of Africa and into Europe and Asia, these populations did not subsequently contribute significant amounts of genetic material (or, some say, contributed absolutely nothing) to later populations along the lineage to Homo sapiens (Ruse and Travis 2009). Later, approximately 200,000 years ago, there was a second migration of hominids out of Africa, and this was modern H. sapiens that replaced the populations that then occupied Europe and Asia (Ruse and Travis 2009). This view maintains a specific speciation event that led to H. sapiens in Africa, and this is the modern human.

The multiregional or continuity camp hold that since the origin of H. erectus, there have been populations of hominids living in the Old World and that these all contributed to successive generations in their regions (Ruse and Travis 2009). According to this view, hominids in China and Indonesia are the most direct ancestors of modern East Asians, those in Africa are the most direct ancestors of modern Africans, and the European populations either gave rise to modern Europeans or contributed significant genetic material to them, while their origins were in Africa or West Asia (Ruse and Travis 2009). There is genetic flow to allow for the maintenance of one species, but not enough to prevent racial differentiation.

There are various combinations of these ideas.

Overall, human evolution theory comprises two principal theories: Those related to the pattern of evolution and those related to the process of evolution. The theory of descent with modification addresses the pattern of evolution, and as applied to humans the theory is strongly supported by the fossil record, which provides evidence of skeletons that through time become more and more like the modern human skeleton. In contrast, the theory of natural selection, which relates to the process of evolution is intrinsically more speculative as it relates to presumed causes.

Substantial evidence has been marshaled for the fact that humans have descended from common ancestors by a process of branching (descent with modification) and for a primate origin of humans. However, proposals for the specific ancestral-descendant relationships and for the process leading to humans tend to be speculative. And, while the theory of natural selection typically is central to scientific explanations for the process, evidence for natural selection being the directive or creative force is limited to extrapolation from the microevolutionary level (changes within the level of species). Historically, a major source of controversy has been the process by which humans have developed, whether by physical forces with an exclusively random component (natural selection) or by the creative force of a Creator God. (Abrahamic religions believe that modern humans derive from an original couple Adam and Eve into whose material bodies God breathed spiritual life (added a spirit or soul) to complete the creation of a being uniquely different from animals.)

Rise of civilization

The rise of agriculture led to the foundation of stable human settlements.

Up until only around 10,000 years ago, all humans lived as hunter-gatherers (with some communities persisting until this day). They generally lived in small, nomadic groups. The advent of agriculture prompted the Neolithic Revolution. Developed independently by geographically distant populations, evidence suggests that agriculture first appeared in Southwest Asia, in the Fertile Crescent. Around 9500 B.C.E., farmers first began to select and cultivate food plants with specific characteristics. Though there is evidence of earlier use of wild cereals, it was not until after 9500 B.C.E. that the eight so-called Neolithic founder crops of agriculture appeared: first emmer wheat and einkorn wheat, then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas, and flax. By 7000 B.C.E., sowing and harvesting reached Mesopotamia. By 6000 B.C.E., farming was entrenched on the banks of the Nile River. About this time, agriculture was developed independently in the Far East, with rice, rather than wheat, the primary crop.

Access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals, and the use of metal tools. Agriculture also encouraged trade and cooperation, leading to complex societies. Villages developed into thriving civilizations in regions such as the Middle East’s Fertile Crescent.

Around 6,000 years ago, the first proto-states developed in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley. Military forces were formed for protection and government bureaucracies for administration. States cooperated and competed for resources, in some cases waging wars. Around 2,000–3,000 years ago, some states, such as Persia, China, and Rome, developed through conquest into the first expansive empires. Influential religions, such as Judaism, originating in the Middle East, and Hinduism, a religious tradition that originated in South Asia, also rose to prominence at this time.

The late Middle Ages saw the rise of revolutionary ideas and technologies. In China, an advanced and urbanized economy promoted innovations such as printing and the compass, while the Islamic Golden Age saw major scientific advancements in Muslim empires. In Europe, the rediscovery of classical learning and inventions such as the printing press led to the Renaissance in the fourteenth century. Over the next 500 years, exploration and imperialistic conquest brought much of the Americas, Asia, and Africa under European control, leading to later struggles for independence.

The Scientific Revolution in the seventeenth century and the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth-nineteenth centuries promoted major innovations in transport, such as the railway and automobile; energy development, such as coal and electricity; and government, such as representative democracy and Communism.

As a result of such changes, modern humans live in a world that has become increasingly globalized and interconnected. Although this has encouraged the growth of science, art, and technology, it has also led to culture clashes, the development and use of weapons of mass destruction, and increased environmental destruction and pollution.

Habitat and population

Humans have structured their environment in extensive ways in order to adapt to problems such as high population density, as shown in this image of the Asian city, Hong Kong.

Early human settlements were dependent on proximity to water and, depending on the lifestyle, other natural resources, such as fertile land for growing crops and grazing livestock, or populations of prey for hunting. However, humans have a great capacity for altering their habitats by various methods, such as through irrigation, urban planning, construction, transport, and manufacturing goods. With the advent of large-scale trade and transport infrastructure, proximity to these resources has become unnecessary, and in many places these factors are no longer a driving force behind the growth and decline of a population. Nonetheless, the manner in which a habitat is altered is often a major determinant in population change.

Technology has allowed humans to colonize all of the continents and adapt to all climates. Within the last few decades, humans have explored Antarctica, the ocean depths, and space, although long-term habitation of these environments is not yet possible.

With a population of over seven billion, humans are among the most numerous of the large mammals. Most humans (61 percent) live in Asia. The vast majority of the remainder live in the Americas (14 percent), Africa (13 percent), and Europe (12 percent), with 0.5 percent in Oceania.

Human habitation within closed ecological systems in hostile environments, such as Antarctica and outer space, is expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Life in space has been very sporadic, with no more than thirteen humans in space at any given time. Between 1969 and 1972, two humans at a time spent brief intervals on the Moon. As of 2007, no other celestial body has been visited by human beings, although there has been a continuous human presence in outer space since the launch of the initial crew to inhabit the International Space Station on October 31, 2000; however, humans have made robots that have visited other celestial bodies.

From 1800 to 2012 C.E., the human population increased from one billion to seven billion. In 2004, around 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people (39.7 percent) lived in urban areas, and this percentage is expected to rise throughout the twenty-first century. Problems for humans living in cities include various forms of pollution and crime, especially in inner city and suburban slums. Benefits of urban living include increased literacy, access to the global canon of human knowledge, and decreased susceptibility to rural famines.

Humans have had a dramatic effect on the environment. The extinction of a number of species has been attributed to anthropogenic factors, such as human predation and habitat loss, and other negative impacts include pollution, widespread loss of wetlands and other ecosystems, alteration of rivers, and introduction of invasive species. On the other hand, humans in the past century have made considerable efforts to reduce negative impacts and provide greater protection for the environment and other living organisms, through such means as environmental law, environmental education, and economic incentives.

Psychology

- For more details on this topic, see Brain and Mind.

The brain is a centralized mass of nerve tissue enclosed within the cranium (skull) of vertebrates. The human brain is the center of the central nervous system in humans, as well as the primary control center for the peripheral nervous system. The brain controls «lower,» or involuntary, autonomic activities such as the respiration, and digestion. The brain also is critical to «higher» order, conscious activities, such as thought, reasoning, and abstraction (PBS 2005). Mayr (2001) states that the human brain «seems not to have changed one single bit since the first appearance of Homo sapiens some 150,000 years ago.»

A central issue in philosophy and religion is how the brain relates to the mind. The brain is defined as the physical and biological matter contained within the skull, responsible for all electrochemical neuronal processes. The mind, however, is seen in terms of mental attributes, such as beliefs or desires. Mind is a concept developed by self-conscious humans trying to understand what is the self that is conscious and how does that self relate to its perceived world. Most broadly, mind is the organized totality of the mental processes of an organism and the structural and functional components on which they depend. Taken more narrowly, as it often is in scientific studies, mind denotes only cognitive activities and functions, such as perceiving, attending, thinking, problem solving, language, learning, and memory (VandenBos 2007).

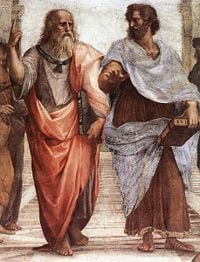

Philosophers have long sought to understand what is mind and its relationship to matter and the body.

There is a concept, tracing back at least to Plato, Aristotle, and the Sankhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy, that «mental» phenomena are, in some respects, «non-physical» (distinct from the body). For example, Saint Thomas Aquinas identified a person as being the composite substance of body and soul (or mind), with soul giving form to body. Christian views after Aquinas have diverged to cover a wide spectrum, but generally they tend to focus on soul instead of mind, with soul referring to an immaterial essence and core of human identity and to the seat of reason, will, conscience, and higher emotions. Rene Descartes established the clear mind-body dualism that has dominated the thought of the modern West. He introduced two assertions: First, that mind and soul are the same and that henceforth he would use the term mind and dispense with the term soul; Second, that mind and body were two distinct substances, one immaterial and one material, and the two existed independent of each other except for one point of interaction in the human brain.

As psychology became a science starting in the late nineteenth century and blossomed into a major scientific discipline in the twentieth century, the prevailing view in the scientific community came to be variants of physicalism with the assumption that all the functions attributed to mind are in one way or another derivative from activities of the brain. Countering this mainstream view, a small group of neuroscientists has persisted in searching for evidence suggesting the possibility of a human mind existing and operating apart from the brain.

In the late twentieth century, as diverse technologies related to studying the mind and body have been steadily improved, evidence has emerged suggesting such radical concepts as: The mind should be associated not only with the brain but with the whole body; and the heart may be a center of consciousness complementing the brain. Some envision a physical mind that mirrors the physical body, guiding its instinctual activities and development, while adding the concept for humans of a spiritual mind that mirrors a spiritual body and including aspects like philosophical and religious thought.

The human brain is generally regarded as more capable of the various higher order activities, and more «intelligent» in general, than that of any other species. While other animals are capable of creating structures and using simple tools—mostly as a result of instinct and learning through mimicry—human technology is vastly more complex, constantly evolving and improving with time. Even the most ancient human tools and structures are far more advanced than any structure or tool created by any other animal (Sagan 1978).

Consciousness and thought

The human ability to think abstractly may be unparalleled in the animal kingdom. Humans are one of only six groups of animals to pass the mirror test—which tests whether an animal recognizes its reflection as an image of itself—along with chimpanzees, orangutans, dolphins, and possibly pigeons. In October 2006, three elephants at the Bronx Zoo also passed this test (Plotnik et al. 2006). Humans under the age of 2 typically fail this test (Palmer 2006). However, this may be a matter of degree rather than a sharp divide. Monkeys have been trained to apply abstract rules in tasks (Coveney 2001).

The brain perceives the external world through the senses, and each individual human is influenced greatly by his or her experiences, leading to subjective views of existence and the passage of time.

Humans are variously said to possess consciousness, self-awareness, and a mind, which correspond roughly to the mental processes of thought. These are said to possess qualities such as self-awareness, sentience, sapience, and the ability to perceive the relationship between oneself and one’s environment. The extent to which the mind constructs or experiences the outer world is a matter of debate, as are the definitions and validity of many of the terms used above. The philosopher of cognitive science Daniel Dennett, for example, argues that there is no such thing as a narrative center called the «mind,» but that instead there is simply a collection of sensory inputs and outputs: Different kinds of «software» running in parallel (Dennett 1991).

Humans study the more physical aspects of the mind and brain, and by extension of the nervous system, in the field of neurology, the more behavioral in the field of psychology, and a sometimes loosely-defined area between in the field of psychiatry, which treats mental illness and behavioral disorders. Psychology does not necessarily refer to the brain or nervous system, and can be framed purely in terms of phenomenological or information processing theories of the mind. Increasingly, however, an understanding of brain functions is being included in psychological theory and practice, particularly in areas such as artificial intelligence, neuropsychology, and cognitive neuroscience.

The nature of thought is central to psychology and related fields. Cognitive psychology studies cognition, the mental processes underlying behavior. It uses information processing as a framework for understanding the mind. Perception, learning, problem solving, memory, attention, language, and emotion are all well-researched areas as well. Cognitive psychology is associated with a school of thought known as cognitivism, whose adherents argue for an information processing model of mental function, informed by positivism and experimental psychology. Techniques and models from cognitive psychology are widely applied and form the mainstay of psychological theories in many areas of both research and applied psychology. Largely focusing on the development of the human mind through the life span, developmental psychology seeks to understand how people come to perceive, understand, and act within the world and how these processes change as they age. This may focus on intellectual, cognitive, neural, social, or moral development.

Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is experience itself, and access consciousness, which is the processing of the things in experience (Block 1995). Phenomenal consciousness is the state of being conscious, such as when they say «I am conscious.» Access consciousness is being conscious of something in relation to abstract concepts, such as when one says «I am conscious of these words.» Various forms of access consciousness include awareness, self-awareness, conscience, stream of consciousness, Husserl’s phenomenology, and intentionality. The concept of phenomenal consciousness, in modern history, according to some, is closely related to the concept of qualia.

Social psychology links sociology with psychology in their shared study of the nature and causes of human social interaction, with an emphasis on how people think towards each other and how they relate to each other. The behavior and mental processes, both human and non-human, can be described through animal cognition, ethology, evolutionary psychology, and comparative psychology as well. Human ecology is an academic discipline that investigates how humans and human societies interact with both their natural environment and the human social environment.

Comparison to other species

Theories in psychology, like the construction of the ego as suggested in the mirror stage by Jacques Lacan, reminds us about the possibility that self-consciouness and self-reflection may be at least in part a human construction. Various attempts have been made to identify a single behavioral characteristic that distinguishes humans from all other animals. Some anthropologists think that readily observable characteristics (tool-making and language) are based on less easily observable mental processes that might be unique among humans: The ability to think symbolically, in the abstract or logically, although several species have demonstrated some abilities in these areas. Nor is it clear at what point exactly in human evolution these traits became prevalent. They may not be restricted to the species Homo sapiens, as the extinct species of the Homo genus (for example, Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus) are believed to also have been adept tool makers and may also have had linguistic skills.

Motivation and emotion

Goya’s Tio Paquete (1820).

- For more details on this topic, see Motivation and Emotion.

Motivation is the driving force of desire behind all deliberate actions of human beings. Motivation is based on emotion, such as the search for satisfaction (positive emotional experiences), and the avoidance of conflict. Positive and negative is defined by the individual brain state, which may be influenced by social norms: a person may be driven to self-injury or violence because their brain is conditioned to create a positive response to these actions. Motivation is important because it is involved in the performance of all learned responses.

Within psychology, conflict avoidance and the libido are seen to be primary motivators. Within economics, motivation is often seen to be based on financial incentives, moral incentives, or coercive incentives. Religions generally posit divine or demonic influences.

Happiness, or being happy, is a human emotional condition. The definition of happiness is a common philosophical topic. Some people might define it as the best condition that a human can have—a condition of mental and physical health. Others may define it as freedom from want and distress; consciousness of the good order of things; assurance of one’s place in the universe or society, inner peace, and so forth.

Human emotion has a significant influence on, or can even be said to control, human behavior, though historically many cultures and philosophers have for various reasons discouraged allowing this influence to go unchecked.

Emotional experiences perceived as pleasant, like love, admiration, or joy, contrast with those perceived as unpleasant, like hate, envy, or sorrow. There is often a distinction seen between refined emotions, which are socially learned, and survival oriented emotions, which are thought to be innate.

Human exploration of emotions as separate from other neurological phenomena is worthy of note, particularly in those cultures where emotion is considered separate from physiological state. In some cultural medical theories, to provide an example, emotion is considered so synonymous with certain forms of physical health that no difference is thought to exist. The Stoics believed excessive emotion was harmful, while some Sufi teachers (in particular, the poet and astronomer Omar Khayyám) felt certain extreme emotions could yield a conceptual perfection, what is often translated as ecstasy.

In modern scientific thought, certain refined emotions are considered to be a complex neural trait of many domesticated and a few non-domesticated mammals. These were commonly developed in reaction to superior survival mechanisms and intelligent interaction with each other and the environment; as such, refined emotion is not in all cases as discrete and separate from natural neural function as was once assumed. Still, when humans function in civilized tandem, it has been noted that uninhibited acting on extreme emotion can lead to social disorder and crime.

Love and sexuality

The Kiss by Francesco Hayez, 1859

Humans are known for forming monogamous pair bonds and for extensive parental care, establishing families of parents and children. They also are known for relationships based on «love.»

Love is any of a number of emotions and experiences related to a sense of strong affection or profound oneness. Depending on context, love can have a wide variety of intended meanings, including sexual attraction. Psychologists and religious teachings, however, define love more precisely, as living for the sake of another, motivated by heart-felt feelings of caring, affection, and responsibility for the other’s well-being.

Perhaps the best context in which to develop such love is the family, where the love that is given and received is of various kinds. Love can involve the sacrifice and investment that parents willingly give on behalf of their children, and children, in turn, can offer their parents filial devotion and respect. Siblings can care for and help one another in various ways. The love between spouses is a world in itself. Grandparents typically bear a profound regard for their grandchildren. All of these types of love have their distinctive features.

Although love is universally desired, it can be fraught with infidelity, deceit, possessiveness, unrealistic expectations, jealousy, and hate. Love, in fact, is at the root of much pain and conflict in the world. Marriages break down when the passion of romance cools.

Human sexuality refers to the expression of sexual sensation and related intimacy between human beings. Biologically, it is the means through which a child is conceived and the lineage is passed on to the next generation. However, besides ensuring biological reproduction, human sexuality has important social functions: It creates physical intimacy, bonds, and hierarchies among individuals; may be directed to spiritual transcendence (according to some traditions); and in a hedonistic sense to the enjoyment of activity involving sexual gratification. Psychologically, sexuality is the means to express the fullness of love between a man and a woman.

There are a great many forms of human sexuality, comprising a broad range of behaviors, and sexual expression varies across cultures and historical periods. Yet the basic principles of human sexuality are universal and integral to what it means to be human. Sex is related to the very purposes of human existence: love, procreation, and family. Sexuality has social ramifications; therefore most societies set limits, through social norms and taboos, moral and religious guidelines, and legal constraints on what is permissible sexual behavior.

As with other human self-descriptions, humans propose that it is high intelligence and complex societies of humans that have produced the most complex sexual behaviors of any animal, including a great many behaviors that are not directly connected with reproduction.

Some scientists and layman hold that human sexuality is not innately monogamous nor by nature exclusively heterosexual (between a man and a woman). For example, Alfred Kinsey, a sex researcher, speculates that people can fall anywhere along a continuous scale of sexual orientation, with only small minorities fully heterosexual or homosexual), while other scientists speculate based on neurology and genetics that people may be born with one sexual orientation or another (Buss 2003; Thornhill and Palmer 2000). Social Darwinism has been used in speculating that it is the natural state of human beings for males to be promiscuous in order to try to widely spread their genes, while females are naturally monogamous, seeking a stable male presence to help during pregnancy and in rearing children given the extensive parental care involved—a concern about reproduction from which women have been freed recently by various forms of contraception.

However, there are a wide body of authorities likewise who maintain that humans are by nature monogamous and heterosexual, as seen in the tradition of pair bonding and families throughout history. For example, the world’s major religions concur in viewing sexual intimacy as proper only within marriage; otherwise, it can be destructive to human flourishing. A common religious perspective is to view promiscuous and non-heterosexual behavior as deviating from the original human nature, and in Christianity such behaviors traditionally are seen as sin that are tied to separation from God—a separation epitomized in the Fall of Man. In psychology, homosexuality was listed for some time as a psychological disorder, although this has fallen into disfavor, and marriage counselors strive to find ways to strengthen marriage and love rather than promote promiscuity. From a more medical point of view, promiscuity is linked to various sexually transmitted diseases and even greater incidents of some forms of cancer, leading to the speculation that it is not an advantageous state for humans.

The rationale for traditional moral strictures on sexuality, in general, is that a sexual activity can express committed love or be a meaningless casual event for recreational purposes. Yet sexual encounters are not merely a physical activity like enjoying good food. Sex involves the partners in their totality, touching their minds and hearts as well as their bodies. Therefore, sexual relations have lasting impact on the psyche. Sexuality is a powerful force that can do tremendous good or terrible harm; therefore it carries with it moral responsibility.

Culture

- For more details on this topic, see Culture.