Origin of devil

The word devil comes from the Latin diabolus (devil), which is a transliteration of the Greek diabolos (devil; diavolos; διάβολος) from the verb diaballo (to insinuate things (against sb), put sb in a bad light, slander, calumniate; from dia- “across, through” + ballo “to throw”; diavallo; διαβάλλω).

.

.

From the same root

English: diabolic, diablerie, ballistic

French: diable, diabolique, diablerie

Italian: diavolo, dabolico, diavoleria

Spanish: diablo, dabolico, diablura

.

.

In modern Greek:

a) diavolos: devil [διάβολος]

b) diavallo: to insinuate things (against sb), put sb in a bad light, slander, calumniate [διαβάλλω]

c) diavoli: calumny, false accusation [διαβολή]

d) diavolicos: diabolic [διαβολικός]

e) vallo: attack, hit out [βάλλω]

f) vallisticos: ballistic [βαλλιστικός]

g) voli: throw, shot [βολή]

.

.

Η λέξη devil προέρχεται από το ελληνικό διάβολος.

.OED

________________________ Post 137. ___________________

.

__________________________________________________

tags within the post: etymology of devil, etymology of diabolic, etymology of diablerie, etymology of ballistic, origin of devil, origin of diabolic, origin of diablerie, origin of ballistic, learn Greek, etymologia de diavolo, etymologie de diable, ετυμολογία, προέλευση αγγλικών λέξεων, προέλευση λατινικών, ετυμολογία του διαβόλου, μαθαίνω ελληνι΄κά, learn Greek online, learn easily Greek, learn Greek for free, etymologia, ετυμολογία

Satan (the dragon; on the left) gives to the beast of the sea (on the right) power represented by a sceptre in a detail of panel III.40 of the medieval French Apocalypse Tapestry, produced between 1377 and 1382.

A fresco detail from the Rila Monastery, in which demons are depicted as having grotesque faces and bodies

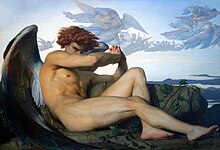

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions.[1] It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force.[2] Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of the devil can be summed up as 1) a principle of evil independent from God, 2) an aspect of God, 3) a created being turning evil (a fallen angel), and 4) a symbol of human evil.[3]: 23

Each tradition, culture, and religion with a devil in its mythos offers a different lens on manifestations of evil.[4] The history of these perspectives intertwines with theology, mythology, psychiatry, art, and literature developing independently within each of the traditions.[5] It occurs historically in many contexts and cultures, and is given many different names—Satan, Lucifer, Beelzebub, Mephistopheles, Iblis—and attributes: it is portrayed as blue, black, or red; it is portrayed as having horns on its head, and without horns, and so on.[6][7] While depictions of the devil are usually taken seriously, there are times when it is treated less seriously; when, for example, devil figures are used in advertising and on candy wrappers.[4][8]

Etymology

The Modern English word devil derives from the Middle English devel, from the Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of the Latin diabolus. This in turn was borrowed from the Greek διάβολος diábolos, «slanderer»,[9] from διαβάλλειν diabállein, «to slander» from διά diá, «across, through» and βάλλειν bállein, «to hurl», probably akin to the Sanskrit gurate, «he lifts up».[10]

Definitions

In his book The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Jeffrey Burton Russell discusses various meanings and difficulties that are encountered when using the term devil. He does not claim to define the word in a general sense, but he describes the limited use that he intends for the word in his book—limited in order to «minimize this difficulty» and «for the sake of clarity». In this book Russell uses the word devil as «the personification of evil found in a variety of cultures», as opposed to the word Satan, which he reserves specifically for the figure in the Abrahamic religions.[11]

In the Introduction to his book Satan: A Biography, Henry Ansgar Kelly discusses various considerations and meanings that he has encountered in using terms such as devil and Satan, etc. While not offering a general definition, he describes that in his book «whenever diabolos is used as the proper name of Satan», he signals it by using «small caps».[12]

The Oxford English Dictionary has a variety of definitions for the meaning of «devil», supported by a range of citations: «Devil» may refer to Satan, the supreme spirit of evil, or one of Satan’s emissaries or demons that populate Hell, or to one of the spirits that possess a demonic person; «devil» may refer to one of the «malignant deities» feared and worshiped by «heathen people», a demon, a malignant being of superhuman powers; figuratively «devil» may be applied to a wicked person, or playfully to a rogue or rascal, or in empathy often accompanied by the word «poor» to a person—»poor devil».[13]

Baháʼí Faith

In the Baháʼí Faith, a malevolent, superhuman entity such as a devil or satan is not believed to exist.[14] These terms do, however, appear in the Baháʼí writings, where they are used as metaphors for the lower nature of man. Human beings are seen to have free will, and are thus able to turn towards God and develop spiritual qualities or turn away from God and become immersed in their self-centered desires. Individuals who follow the temptations of the self and do not develop spiritual virtues are often described in the Baháʼí writings with the word satanic.[14] The Baháʼí writings also state that the devil is a metaphor for the «insistent self» or «lower self» which is a self-serving inclination within each individual. Those who follow their lower nature are also described as followers of «the Evil One».[15][16]

Christianity

In Christianity, evil is incarnate in the devil or Satan, a fallen angel who is the primary opponent of God.[17][18] Some Christians also considered the Roman and Greek deities as devils.[6][7]

Christianity describes Satan as a fallen angel who terrorizes the world through evil,[17] is the antithesis of truth,[19] and shall be condemned, together with the fallen angels who follow him, to eternal fire at the Last Judgment.[17]

In mainstream Christianity, the devil is usually referred to as Satan. This is because Christian beliefs in Satan are inspired directly by the dominant view of Second Temple Judaism (recorded in the Enochian books), as expressed/practiced by Jesus, and with some minor variations. Some modern Christians[who?] consider the devil to be an angel who, along with one-third of the angelic host (the demons), rebelled against God and has consequently been condemned to the Lake of Fire. He is described[attribution needed] as hating all humanity (or more accurately creation), opposing God, spreading lies and wreaking havoc on their souls.

Satan is traditionally identified as the serpent who convinced Eve to eat the forbidden fruit; thus, Satan has often been depicted as a serpent.

In the Bible, the devil is identified with «the dragon» and «the old serpent» seen in the Book of Revelation,[21] as has «the prince of this world» in the Gospel of John;[22] and «the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience» in the Epistle to the Ephesians;[23] and «the god of this world» in 2 Corinthians 4:4.[24] He is also identified as the dragon in the Book of Revelation[25] and the tempter of the Gospels.[26]

The devil is sometimes called Lucifer, particularly when describing him as an angel before his fall, although the use of Lucifer (Latin lúcifer or «bringer of light», Hebrew hêlēl), the «son of the dawn» (ben šāḥar), in Isaiah 14:12 is a reference to a Babylonian king.[27]

Beelzebub is originally the name of a Philistine god (more specifically a certain type of Baal, from Ba‘al Zebûb, lit. «Lord of Flies») but is also used in the New Testament as a synonym for the devil. A corrupted version, «Belzeboub», appears in The Divine Comedy (Inferno XXXIV).

In other, non-mainstream, Christian beliefs (e.g. the beliefs of the Christadelphians) the word «satan» in the Bible is not regarded as referring to a supernatural, personal being but to any ‘adversary’ and figuratively refers to human sin and temptation.[28]

Apocrypha/Deuterocanon

In the Book of Wisdom, the devil is represented as the one who brought death into the world.[29] The Second Book of Enoch contains references to a Watcher called Satanael,[30] describing him as the prince of the Grigori who was cast out of heaven[31] and an evil spirit who knew the difference between what was «righteous» and «sinful».[32]

In the Book of Jubilees, Satan rules over a host of angels.[33] Mastema, who induced God to test Abraham through the sacrifice of Isaac, is identical with Satan in both name and nature.[34] The Book of Enoch contains references to Sathariel, thought also[by whom?] to be Sataniel and Satan’el. The similar spellings mirror that of his angelic brethren Michael, Raphael, Uriel, and Gabriel, previous to his expulsion from Heaven.[citation needed]

Gnostic religions

A lion-faced deity found on a Gnostic gem in Bernard de Montfaucon’s L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures may be a depiction of the Demiurge.

Gnostic and Gnostic-influenced religions postulate the idea that the material world is inherently evil. The One true God is remote, beyond the material universe, therefore this universe must be governed by an inferior imposter deity. This deity was identified with the deity of the Old Testament by some sects, such as the Sethians and the Marcions. Tertullian accuses Marcion of Sinope, that he

[held that] the Old Testament was a scandal to the faithful … and … accounted for it by postulating [that Jehovah was] a secondary deity, a demiurgus, who was god, in a sense, but not the supreme God; he was just, rigidly just, he had his good qualities, but he was not the good god, who was Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ.[35]

John Arendzen (1909) in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) mentions that Eusebius accused Apelles, the 2nd-century AD Gnostic, of considering the Inspirer of Old Testament prophecies to be not a god, but an evil angel.[36] These writings commonly refer to the Creator of the material world as «a demiurgus»[35] to distinguish him from the One true God. Some texts, such as the Apocryphon of John and On the Origin of the World, not only demonized the Creator God but also called him by the name of the devil in some Jewish writings, Samael.[37]

Catharism

In the 12th century in Europe the Cathars, who were rooted in Gnosticism, dealt with the problem of evil, and developed ideas of dualism and demonology. The Cathars were seen as a serious potential challenge to the Catholic church of the time. The Cathars split into two camps. The first is absolute dualism, which held that evil was completely separate from the good God, and that God and the devil each had power. The second camp is mitigated dualism, which considers Lucifer to be a son of God, and a brother to Christ. To explain this they used the parable of the prodigal son, with Christ as the good son, and Lucifer as the son that strayed into evilness. The Catholic Church responded to dualism in AD 1215 in the Fourth Lateran Council, saying that God created everything from nothing, and the devil was good when he was created, but he made himself bad by his own free will.[38][39] In the Gospel of the Secret Supper, Lucifer, just as in prior Gnostic systems, appears as a demiurge, who created the material world.[40]

Islam

In Islam, the principle of evil is expressed by two terms referring to the same entity:[41][42][43] Shaitan (meaning astray, distant or devil) and Iblis. Iblis is the proper name of the devil representing the characteristics of evil.[44] Iblis is mentioned in the Quranic narrative about the creation of humanity. When God created Adam, he ordered the angels to prostrate themselves before him. All did, but Iblis refused and claimed to be superior to Adam out of pride. [Quran 7:12] Therefore, pride but also envy became a sign of «unbelief» in Islam.[44] Thereafter Iblis was condemned to Hell, but God granted him a request to lead humanity astray,[45] knowing the righteous would resist Iblis’ attempts to misguide them. In Islam, both good and evil are ultimately created by God. But since God’s will is good, the evil in the world must be part of God’s plan.[46] Actually, God allowed the devil to seduce humanity. Evil and suffering are regarded as a test or a chance to proof confidence in God.[46] Some philosophers and mystics emphasized Iblis himself as a role model of confidence in God, because God ordered the angels to prostrate themselves, Iblis was forced to choose between God’s command and God’s will (not to praise someone else than God). He successfully passed the test, yet his disobedience caused his punishment and therefore suffering. However, he stays patient and is rewarded in the end.[47]

Muslims hold that the pre-Islamic jinn, tutelary deities, became subject under Islam to the judgment of God, and that those who did not submit to the law of God are devils.[48]

Although Iblis is often compared to the devil in Christian theology, Islam rejects the idea that Satan is an opponent of God and the implied struggle between God and the devil.[clarification needed] Iblis might either be regarded as the most monotheistic or the greatest sinner, but remains only a creature of God. Iblis did not become an unbeliever due to his disobedience, but because of attributing injustice to God; that is, by asserting that the command to prostrate himself before Adam was inappropriate.[49] There is no sign of angelic revolt in the Quran and no mention of Iblis trying to take God’s throne[50][51] and Iblis’s sin could be forgiven at anytime by God.[52] According to the Quran, Iblis’s disobedience was due to his disdain for humanity, a narrative already occurring in early New Testament apocrypha.[53]

As in Christianity, Iblis was once a pious creature of God but later cast out of Heaven due to his pride. However, to maintain God’s absolute sovereignty,[54] Islam matches the line taken by Irenaeus instead of the later Christian consensus that the devil did not rebel against God but against humanity.[55][42] Further, although Iblis is generally regarded as a real bodily entity,[56] he plays a less significant role as the personification of evil than in Christianity. Iblis is merely a tempter, notable for inciting humans into sin by whispering into humans minds (waswās), akin to the Jewish idea of the devil as yetzer hara.[57][58]

On the other hand, Shaitan refers unilaterally to forces of evil, including the devil Iblis, then he causes mischief.[59] Shaitan is also linked to humans psychological nature, appearing in dreams, causing anger or interrupting the mental preparation for prayer.[56] Furthermore, the term Shaitan also refers to beings, who follow the evil suggestions of Iblis. Furthermore, the principle of shaitan is in many ways a symbol of spiritual impurity, representing humans’ own deficits, in contrast to a «true Muslim», who is free from anger, lust and other devilish desires.[60]

In Muslim culture, devils are believed to be hermaphrodite creatures created from hell-fire, with one male and one female thigh. By that, they procreate without another mate. It is generally believed that devils can harm the souls of humans through their whisperings. While whisperings tempt humans to sin, the devils might enter the hearth (qalb) of an individual. If the devils take over the soul of a person, this would render them aggressive or insane.[61] In extreme cases, the alterings of the soul are believed to have effect on the body, matching its spiritual qualities.[62]

In Sufism and mysticism

In contrast to Occidental philosophy, the Sufi idea of seeing «Many as One», and considering the creation in its essence as the Absolute, leads to the idea of the dissolution of any dualism between the ego substance and the «external» substantial objects. The rebellion against God, mentioned in the Quran, takes place on the level of the psyche, that must be trained and disciplined for its union with the spirit that is pure. Since psyche drives the body, flesh is not the obstacle to humans but rather an unawareness that allows the impulsive forces to cause rebellion against God on the level of the psyche. Yet it is not a dualism between body, psyche and spirit, since the spirit embraces both psyche and corporeal aspects of humanity.[63] Since the world is held to be the mirror in which God’s attributes are reflected, participation in worldly affairs is not necessarily seen as opposed to God.[57] The devil activates the selfish desires of the psyche, leading the human astray from the Divine.[64] Thus it is the I that is regarded as evil, and both Iblis and Pharao are present as symbols for uttering «I» in ones own behavior. Therefore it is recommended to use the term I as little as possible. It is only God who has the right to say «I», since it is only God who is self-subsistent. Uttering «I» is therefore a way to compare oneself to God, regarded as shirk.[65]

In Salafism

Salafi strands of Islam commonly emphasize a dualistic worldview contrasting believers and unbelievers,[66] and featuring the devil as the enemy of the faithful who tries to lead them astray from God’s path. Even though the devil will eventually be defeated by God, he remains a serious and dangerous opponent of humans.[67] While in classical hadiths, the demons (Shayateen) and the jinn are responsible for impurity and capable of endangering human souls, in Salafi thought, it is the devil himself, who lies in wait for believers,[68] always striving to lure them away from God. The devil is regarded as an omnipresent entity, permanently inciting humans into sin, but can be pushed away by remembering the name God.[69] The devil is regarded as an external entity, threatening the everyday life of the believer, even in social aspects of life.[70] Thus for example, it is the devil who is responsible for Western emancipation.[71]

Judaism

Yahweh, the god in pre-exilic Judaism, created both good and evil, as stated in Isaiah 45:7: «I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things.» The devil does not exist in Jewish scriptures. However, the influence of Zoroastrianism during the Achaemenid Empire introduced evil as a separate principle into the Jewish belief system, which gradually externalized the opposition until the Hebrew term satan developed into a specific type of supernatural entity, changing the monistic view of Judaism into a dualistic one.[72] Later, Rabbinic Judaism rejected[when?] the Enochian books (written during the Second Temple period under Persian influence), which depicted the devil as an independent force of evil besides God.[73] After the apocalyptic period, references to Satan in the Tanakh are thought[by whom?] to be allegorical.[74]

Mandaeism

In Mandaean mythology, Ruha fell apart from the World of Light and became the queen of the World of Darkness, also referred to as Sheol.[75][76][77] She is considered evil and a liar, sorcerer and seductress.[78]: 541 She gives birth to Ur, also referred to as Leviathan. He is portrayed as a large, ferocious dragon or snake and is considered the king of the World of Darkness.[76] Together they rule the underworld and create the seven planets and twelve zodiac constellations.[76] Also found in the underworld is Krun, the greatest of the five Mandaean Lords of the underworld. He dwells in the lowest depths of creation and his epithet is the ‘mountain of flesh’.[79]: 251 Prominent infernal beings found in the World of Darkness include lilith, nalai (vampire), niuli (hobgoblin), latabi (devil), gadalta (ghost), satani (Satan) and various other demons and evil spirits.[76][75]

Manichaeism

In Manichaeism, God and the devil are two unrelated principles. God created good and inhabits the realm of light, while the devil (also called the prince of darkness[80][81]) created evil and inhabits the kingdom of darkness. The contemporary world came into existence, when the kingdom of darkness assaulted the kingdom of light and mingled with the spiritual world.[82] At the end, the devil and his followers will be sealed forever and the kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness will continue to co-exist eternally, never to commingle again.[83]

Hegemonius (4th century CE) accuses that the Persian prophet Mani, founder of the Manichaean sect in the 3rd century CE, identified Jehovah as «the devil god which created the world»[84] and said that «he who spoke with Moses, the Jews, and the priests … is the [Prince] of Darkness, … not the god of truth.»[80][81]

Tengrism

Among the Tengristic myths of central Asia, Erlik refers to a devil-like figure as the ruler of Tamag (Hell), who was also the first human. According to one narrative, Erlik and God swam together over the primordial waters. When God was about to create the Earth, he sent Erlik to dive into the waters and collect some mud. Erlik hid some inside his mouth to later create his own world. But when God commanded the Earth to expand, Erlik got troubled by the mud in his mouth. God aided Erlik to spit it out. The mud carried by Erlik gave place to the unpleasant areas of the world. Because of his sin, he was assigned to evil. In another variant, the creator-god is identified with Ulgen. Again, Erlik appears to be the first human. He desired to create a human just as Ulgen did, thereupon Ulgen reacted by punishing Erlik, casting him into the Underworld where he becomes its ruler.[85][86]

According to Tengrism, there is no death, meaning that, when life comes to an end, it is merely a transition into the invisible world. As the ruler of Hell, Erlik enslaves the souls, who are damned to Hell. Further, he lurks on the souls of those humans living on Earth by causing death, disease and illnesses. At the time of birth, Erlik sends a Kormos to seize the soul of the newborn, following him for the rest of his life in an attempt to seize his soul by hampering, misguiding, and injuring him. When Erlik succeeds in destroying a human’s body, the Kormos sent by Erlik will try take him down into the Underworld. However a good soul will be brought to Paradise by a Yayutshi sent by Ulgen.[87] Some shamans also made sacrifices to Erlik, for gaining a higher rank in the Underworld, if they should be damned to Hell.

Yazidism

According to Yazidism there is no entity that represents evil in opposition to God; such dualism is rejected by Yazidis,[88] and evil is regarded as nonexistent.[89] Yazidis adhere to strict monism and are prohibited from uttering the word «devil» and from speaking of anything related to Hell.[90]

Zoroastrianism

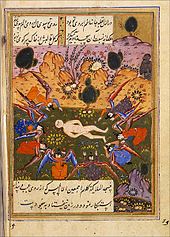

Ahriman Div being slain during a scene from the Shahnameh

Zoroastrianism probably introduced the first idea of the devil; a principle of evil independently existing apart from God.[91] In Zoroastrianism, good and evil derive from two ultimately opposed forces.[92] The force of good is called Ahura Mazda and the «destructive spirit» in the Avestan language is called Angra Mainyu. The Middle Persian equivalent is Ahriman. They are in eternal struggle and neither is all-powerful, especially Angra Mainyu is limited to space and time: in the end of time, he will be finally defeated. While Ahura Mazda creates what is good, Angra Mainyu is responsible for every evil and suffering in the world, such as toads and scorpions.[91]

Iranian Zoroastrians also considered the Daeva as devil creature, because of this in the Shahnameh, it is mentioned as both Ahriman Div (Persian: اهریمن دیو, romanized: Ahriman Div) as a devil.

Devil in moral philosophy

Spinoza

A non-published manuscript of Spinoza’s Ethics contained a chapter (Chapter XXI) on the devil, where Spinoza examined whether the devil may exist or not. He defines the devil as an entity which is contrary to God.[93]: 46 [94]: 150 However, if the devil is the opposite of God, the devil would consist of Nothingness, which does not exist.[93]: 145

In a paper called On Devils, he writes that we can a priori find out that such a thing cannot exist. Because the duration of a thing results in its degree of perfection, and the more essence a thing possess the more lasting it is, and since the devil has no perfection at all, it is impossible for the devil to be an existing thing.[95]: 72 Evil or immoral behaviour in humans, such as anger, hate, envy, and all things for which the devil is blamed for could be explained without the proposal of a devil.[93]: 145 Thus, the devil doesn’t have any explanatory power and should be dismissed (Occam’s razor).

Regarding evil through free-choice, Spinoza asks how it can be that Adam would have chosen sin over his own well-being. Theology traditionally responds to this by asserting it is the devil who tempts humans into sin, but who would have tempted the devil? According to Spinoza, a rational being, such as the devil must have been, could not choose his own damnation.[96] The devil must have known his sin would lead to doom, thus the devil was not knowing, or the devil didn’t know his sin will lead to doom, thus the devil would not have been a rational being. Spinoza deducts a strict determinism in which moral agency as a free choice, cannot exist.[93]: 150

Kant

Engraving of Immanuel Kant

In Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, Immanuel Kant uses the devil as the personification of maximum moral reprehensibility. Deviating from the common Christian idea, Kant does not locate the morally reprehensible in sensual urges. Since evil has to be intelligible, only when the sensual is consciously placed above the moral obligation can something be regarded as morally evil. Thus, to be evil, the devil must be able to comprehend morality but consciously reject it, and, as a spiritual being (Geistwesen), having no relation to any form of sensual pleasure. It is necessarily required for the devil to be a spiritual being, because if the devil were also a sensual[clarification needed], it would be possible that the devil does evil to satisfy lower sensual desires, and doesn’t act from the mind alone. The devil acts against morals, not to satisfy a sensual lust, but solely for the sake of evil. As such, the devil is unselfish, for he does not benefit from his evil deeds.

However, Kant denies that a human being could ever be completely devilish. Kant admits that there are devilish vices (ingratitude, envy, and malicious joy), i.e., vices that do not bring any personal advantage, but a person can never be completely a devil. In his Lecture on Moral Philosophy (1774/75) Kant gives an example of a tulip seller who was in possession of a rare tulip, but when he learned that another seller had the same tulip, he bought it from him and then destroyed it instead to keeping it for himself. If he had acted according to his sensual[clarification needed] in according to his urges, the seller would have kept the tulip for himself to make profit, but not have destroyed it. Nevertheless, the destruction of the tulip cannot be completely absolved from sensual impulses, since a sensual joy or relief still accompanies the destruction of the tulip and therefore cannot be thought of solely as a violation of morality.[97]: 156-173

Kant further argues that a (spiritual) devil would be a contradiction. If the devil would be defined by doing evil, the devil had no free-choice in the first place. But if the devil had no free-choice, the devil could not have been held accountable for his actions, since he had no free-will but was only following his nature.[98]

Titles

Honorifics or styles of address used to indicate devil-figures.

- Ash-Shaytan «Satan», the attributive Arabic term referring to the devil

- Angra Mainyu, Ahriman: «malign spirit», «unholy spirit»

- Dark lord

- Der Leibhaftige [Teufel] (German): «[the devil] in the flesh, corporeal»[99]

- Diabolus, Diabolos (Greek: Διάβολος)

- The Evil One

- The Father of Lies (John 8:44), in contrast to Jesus («I am the truth»).

- Iblis, name of the devil in Islam

- The Lord of the Underworld / Lord of Hell / Lord of this world

- Lucifer / the Morning Star (Greek and Roman): the bringer of light, illuminator; the planet Venus, often portrayed as Satan’s name in Christianity

- Kölski (Iceland)[100]

- Mephistopheles

- Old Scratch, the Stranger, Old Nick: a colloquialism for the devil, as indicated by the name of the character in the short story «The Devil and Tom Walker»

- Prince of darkness, the devil in Manichaeism

- Ruprecht (German form of Robert), a common name for the Devil in Germany (see Knecht Ruprecht (Knight Robert))

- Satan / the Adversary, Accuser, Prosecutor; in Christianity, the devil

- (The ancient/old/crooked/coiling) Serpent

- Voland (fictional character in The Master and Margarita)

See also

- Deal with the Devil

- Devil in popular culture

- Hades, Underworld

- Krampus,[101][102] in the Tyrolean area also Tuifl[103][104]

- Non-physical entity

- Theistic Satanism

References

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 11 and 34

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 34

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1990). Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9718-6.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 41–75

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, pp. 44 and 51

- ^ a b Arp, Robert. The Devil and Philosophy: The Nature of His Game. Open Court, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8126-9880-0. pp. 30–50

- ^ a b Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press. 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3. p. 66.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton, The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History, Cornell University Press (1992) ISBN 978-0-8014-8056-0, p. 2

- ^ διάβολος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ «Definition of DEVIL». www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell (1987). The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. Cornell University Press. pp. 11, 34. ISBN 0-8014-9409-5.

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2006). Satan: A Biography. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-521-60402-4.

- ^ Craige, W. A.; Onions, C. T. A. «Devil». A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles: Introduction, Supplement, and Bibliography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (1933) pp. 283–284

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (2000). «satan». A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 304. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Bahá’u’lláh; Baháʼuʼlláh (1994) [1873–92]. «Tablet of the World». Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed After the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 87. ISBN 0-87743-174-4.

- ^ Shoghi Effendi quoted in Hornby, Helen (1983). Hornby, Helen (ed.). Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. Baháʼí Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India. p. 513. ISBN 81-85091-46-3.

- ^ a b c Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press (US). ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 174

- ^ «Definition of DEVIL». www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Fritscher, Jack (2004). Popular Witchcraft: Straight from the Witch’s Mouth. Popular Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-299-20304-2.

The pig, goat, ram—all of these creatures are consistently associated with the Devil.

- ^ 12:9, 20:2

- ^ 12:31, 14:30

- ^ 2:2

- ^ 2 Corinthians 2:2

- ^ e.g. Rev. 12:9

- ^ e.g. Matthew 4:1

- ^ See, for example, the entries in Nave’s Topical Bible, the Holman Bible Dictionary and the Adam Clarke Commentary.

- ^ «Do you Believe in a Devil? Bible Teaching on Temptation». Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ^ «But by the envy of the devil, death came into the world» – Book of Wisdom II. 24

- ^ 2 Enoch 18:3

- ^ «And I threw him out from the height with his angels, and he was flying in the air continuously above the bottomless» – 2 Enoch 29:4

- ^ «The devil is the evil spirit of the lower places, as a fugitive he made Sotona from the heavens as his name was Satanail, thus he became different from the angels, but his nature did not change his intelligence as far as his understanding of righteous and sinful things» – 2 Enoch 31:4

- ^ Martyrdom of Isaiah, 2:2; Vita Adæ et Evæ, 16)

- ^ Book of Jubilees, xvii. 18

- ^ a b Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Marcionites» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Gnosticism» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Birger A. Pearson Gnosticism Judaism Egyptian Fortress Press ISBN 978-1-4514-0434-0 p. 100

- ^ Rouner, Leroy (1983). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-664-22748-7.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1, pp. 187–188

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 764

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN 978-90-04-14764-5 p. 526

- ^ a b Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-801-49429-1, p. 57

- ^ Benjamin W. McCraw, Robert Arp Philosophical Approaches to the Devil Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-317-39221-7

- ^ a b Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 p. 250

- ^ Quran 17:62

- ^ a b Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 p. 249

- ^ Jerald D. Gort, Henry Jansen, Hendrik M. Vroom Probing the Depths of Evil and Good: Multireligious Views and Case Studies Rodopi 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2231-7 pp. 254–255

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 58

- ^ Sharpe, Elizabeth Marie Into the realm of smokeless fire: (Qur’an 55:14): A critical translation of al-Damiri’s article on the jinn from «Hayat al-Hayawan al-Kubra 1953 The University of Arizona download date: 15/03/2020

- ^ El-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0815650706.

- ^ Vicchio, Stephen J. (2008). Biblical Figures in the Islamic Faith. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. pp. 175–185. ISBN 978-1556353048.

- ^ Ahmadi, Nader; Ahmadi, Fereshtah (1998). Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual. Berlin, Germany: Axel Springer. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5.

- ^ Houtman, Alberdina; Kadari, Tamar; Poorthuis, Marcel; Tohar, Vered (2016). Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception. Leiden, Germany: Brill Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-8156-5070-6 p. 45

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 56

- ^ a b Cenap Çakmak Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia [4 volumes] ABC-CLIO 2017 ISBN 978-1-610-69217-5 p. 1399

- ^ a b Fereshteh Ahmadi, Nader Ahmadi Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual Springer 1998 ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5 p. 79

- ^ Nils G. Holm The Human Symbolic Construction of Reality: A Psycho-Phenomenological Study LIT Verlag Münster 2014 ISBN 978-3-643-90526-0 p. 54

- ^ «Shaitan, Islamic Mythology.» Encyclopaedia Britannica (Britannica.com). Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 74

- ^ Bullard, A. (2022). Spiritual and Mental Health Crisis in Globalizing Senegal: A History of Transcultural Psychiatry. USA: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Woodward, Mark. Java, Indonesia and Islam. Deutschland, Springer Netherlands, 2010. p. 88

- ^ Fereshteh Ahmadi, Nader Ahmadi Iranian Islam: The Concept of the Individual Springer 1998 ISBN 978-0-230-37349-5 p. 81-82

- ^ John O’Kane, Bernd Radtke The Concept of Sainthood in Early Islamic Mysticism: Two Works by Al-Hakim Al-Tirmidhi – An Annotated Translation with Introduction Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-136-79309-7 p. 48

- ^ Peter J. Awn Satan’s Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology BRILL 1983 ISBN 978-90-04-06906-0 p. 93

- ^ Thorsten Gerald Schneiders Salafismus in Deutschland: Ursprünge und Gefahren einer islamisch-fundamentalistischen Bewegung transcript Verlag 2014 ISBN 978-3-8394-2711-8 p. 392 (German)

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 67

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 68

- ^ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 69

- ^ Michael Kiefer, Jörg Hüttermann, Bacem Dziri, Rauf Ceylan, Viktoria Roth, Fabian Srowig, Andreas Zick „Lasset uns in shaʼa Allah ein Plan machen“: Fallgestützte Analyse der Radikalisierung einer WhatsApp-Gruppe Springer-Verlag 2017 ISBN 978-3-658-17950-2 p. 111

- ^ Janusz Biene, Christopher Daase, Julian Junk, Harald Müller Salafismus und Dschihadismus in Deutschland: Ursachen, Dynamiken, Handlungsempfehlungen Campus Verlag 2016 9783593506371 p. 177 (German)

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 58

- ^ Jackson, David R. (2004). Enochic Judaism. London: T&T Clark International. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0-8264-7089-0

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 29

- ^ a b Al-Saadi, Qais Mughashghash; Al-Saadi, Hamed Mughashghash (2019). «Glossary». Ginza Rabba: The Great Treasure. An equivalent translation of the Mandaean Holy Book (2 ed.). Drabsha.

- ^ a b c d Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443.

- ^ Deutsch, Nathniel (2003). Mandaean Literature. In Barnstone, Willis; Meyer, Marvin (2003). The Gnostic Bible. Boston & London: Shambhala.

- ^ Drower, E.S. (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Acta Archelai of Hegemonius, Chapter XII, c. AD 350, quoted in Translated Texts of Manicheism, compiled by Prods Oktor Skjærvø, p. 68.

- ^ a b History of the Acta Archelai explained in the Introduction, p. 11

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 596

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 p. 598

- ^ Manichaeism by Alan G. Hefner in The Mystica, undated

- ^ Mircea Eliade History of Religious Ideas, Volume 3: From Muhammad to the Age of Reforms University of Chicago Press, 31 December 2013 ISBN 978-0-226-14772-7 p. 9

- ^ David Adams Leeming A Dictionary of Creation Myths Oxford University Press 2014 ISBN 978-0-19-510275-8 p. 7

- ^ Plantagenet Publishing The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1–5

- ^ Birgül Açikyildiz The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion I.B. Tauris 2014 ISBN 978-0-857-72061-0 p. 74

- ^ Wadie Jwaideh The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development Syracuse University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-815-63093-7 p. 20

- ^ Florin Curta, Andrew Holt Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes] ABC-CLIO 2016 ISBN 978-1-610-69566-4 p. 513

- ^ a b Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0-801-49409-3, p. 99

- ^ John R. Hinnells The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion and Migration OUP Oxford 2005 ISBN 978-0-191-51350-3 p. 108

- ^ a b c d , B. d., Spinoza, B. (1985). The Collected Works of Spinoza, Volume I. Vereinigtes Königreich: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Jarrett, C. (2007). Spinoza: A Guide for the Perplexed. Vereinigtes Königreich: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ Guthrie, S. L. (2018). Gods of this World: A Philosophical Discussion and Defense of Christian Demonology. USA: Pickwick Publications.

- ^ Polka, B. (2007). Between Philosophy and Religion, Vol. II: Spinoza, the Bible, and Modernity. Ukraine: Lexington Books.

- ^ Hendrik Klinge: Die moralische Stufenleiter: Kant über Teufel, Menschen, Engel und Gott. Walter de Gruyter, 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-057620-7

- ^ Formosa, Paul. «Kant on the limits of human evil.» Journal of Philosophical Research 34 (2009): 189-214.

- ^ Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch s.v. «leibhaftig»:

«gern in bezug auf den teufel: dasz er kein mensch möchte sein, sondern ein leibhaftiger teufel. volksbuch von dr. Faust […] der auch blosz der leibhaftige heiszt, so in Tirol. Fromm. 6, 445; wenn ich dén sehe, wäre es mir immer, der leibhaftige wäre da und wolle mich nehmen. J. Gotthelf Uli d. pächter (1870) 345 - ^ «Vísindavefurinn: How many words are there in Icelandic for the devil?». Visindavefur.hi.is. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Krampus: Gezähmter Teufel mit grotesker Männlichkeit, in Der Standard from 5 December 2017

- ^ Wo heut der Teufel los ist, in Kleine Zeitung from 25 November 2017

- ^ Krampusläufe: Tradition trifft Tourismus, in ORF from 4 December 2016

- ^ Ein schiacher Krampen hat immer Saison, in Der Standard from 5 December 2017

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Devil.

- Entry from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Can you sell your soul to the Devil? A Jewish view on the Devil

- Afrikaans: duiwel

- Albanian: dreq (sq) m, djall (sq) m, shejtan (sq) m

- Amharic: ዲያቦሎስ (diyabolos), ሳይጣን (sayṭan), ኢብሊስ (ʾiblis)

- Arabic: شَيْطَان (ar) m (šayṭān), إِبْلِيس m (ʔiblīs)

- Armenian: դև (hy) (dew), սատանա (hy) (satana)

- Aromanian: dracu

- Assamese: চৈতান (soitan)

- Asturian: diablu m

- Azerbaijani: şeytan (az), iblis (az)

- Bashkir: шайтан (şaytan), иблис (iblis)

- Belarusian: чорт m (čort), д’я́бал m (dʺjábal), бес m (bjes), сатана́ m (sataná)

- Bengali: শয়তান (bn) (śoẏotan), ইবলিশ (iboliś), রাক্ষস (bn) (rakkhoś)

- Bulgarian: дя́вол (bg) m (djávol), гя́вол m (gjávol) (alternative, archaic), сатана́ (bg) m (sataná), шейта́н (bg) m (šejtán) (Muslim)

- Burmese: ငရဲမင်း (my) (nga.rai:mang:), နတ်ဆိုး (my) (nathcui:), ငရဲသား (my) (nga.rai:sa:), ယမမင်း (my) (ya.ma.mang:)

- Catalan: dimoni (ca) m, diable (ca) m

- Chechen: шайтӏа (šajtʼa), йилбаз (jilbaz), лилбаз (lilbaz)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 惡魔/恶魔 (ok3 mo1), 魔鬼 (mo1 gwai2)

- Dungan: шэтани (šetani), йиблисы (yiblisɨ)

- Mandarin: 惡魔/恶魔 (zh) (èmó), 魔鬼 (zh) (móguǐ), 邪魔 (zh) (xiémó), 惡鬼/恶鬼 (zh) (èguǐ)

- Min Nan: 惡魔/恶魔 (zh-min-nan) (ok-mô͘), 魔鬼 (zh-min-nan) (mô͘-kúi)

- Chuvash: явӑл m (javăl)

- Cornish: dyowl m

- Crimean Tatar: şaytan

- Czech: ďábel (cs) m, čert (cs) m

- Dalmatian: diaul m

- Danish: djævel c

- Dutch: duivel (nl) m

- Esperanto: diablo

- Estonian: kurat (et), saatan

- Faroese: djevul m, devul m, fani m, fjandi m, níðingur m, púki m

- Finnish: paholainen (fi), piru (fi), perkele (fi), sielunvihollinen (fi), demoni (fi) sg

- French: diable (fr) m

- Friulian: diaul m, cudiç m

- Galician: demo (gl) m

- Georgian: ეშმაკი (ešmaḳi)

- German: Teufel (de) m

- Gothic: 𐌳𐌹𐌰𐌱𐌰𐌿𐌻𐌿𐍃 m (diabaulus), 𐌿𐌽𐌷𐌿𐌻𐌸𐌰 m (unhulþa), 𐌿𐌽𐌷𐌿𐌻𐌸𐍉 m (unhulþō)

- Greek: διάβολος (el) m (diávolos)

- Ancient: διάβολος m (diábolos)

- Greenlandic: diaavulu, tiaavulu

- Gujarati: શયતાન m (śayatān)

- Haitian Creole: dyab

- Hausa: shaidan

- Hebrew: שֵׁד (he) m (shed), שָׂטָן (he) m (satán)

- Hindi: शैतान (hi) m (śaitān), दानव (hi) m (dānav), राक्षस (hi) m (rākṣas), देव (hi) m (dev), इबलीस (hi) m (iblīs)

- Hungarian: ördög (hu)

- Hunsrik: Deivel m

- Icelandic: djöfull (is) m, fjandi (is) m, skratti m, ári m, fjári (is) m

- Ido: diablo (io)

- Indonesian: iblis (id), syaitan (id), setan (id)

- Interlingua: diabolo

- Irish: diabhal m

- Istriot: giavo m, djavo m

- Italian: diavolo (it) m

- Japanese: 悪魔 (ja) (あくま, akuma), 鬼 (ja) (おに, oni), 悪鬼 (ja) (あっき, akki)

- Kannada: ದೆವ್ವದ (devvada)

- Kapampangan: mamayuyut, mikimarok, dimoniyu, diyablu

- Kazakh: жын (kk) (jyn), сайтан (saitan), шайтан (şaitan), әбілет (äbılet), ібіліс (ıbılıs)

- Khakas: айна (ayna)

- Khmer: បិសាច (km) (bəysaac), សាតាំង (km) (saatang), យម (yum)

- Kikuyu: caitaani

- Korean: 악마(惡魔) (ko) (angma), 악귀(惡鬼) (ko) (akgwi)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: şeytan (ku) m, îblîs (ku) m

- Kven: perkelet

- Kyrgyz: шайтан (ky) (şaytan), азезил (ky) (azezil), жин (ky) (jin)

- Laboya: moritana

- Lao: ປີສາດ (pī sāt)

- Latgalian: valns, lyga

- Latin: diabolus (la) m, larva f

- Latvian: velns m

- Lithuanian: velnias m

- Low German:

- German Low German: Düvel (nds) m

- Luxembourgish: Däiwel m

- Macedonian: ѓавол m (ǵavol), враг m (vrag), шејтан m (šejtan) (Muslim)

- Malagasy: devoly (mg)

- Malay: iblis, syaitan

- Malayalam: ചെകുത്താൻ (ml) (cekuttāṉ)

- Maltese: xitan m, xitana f

- Maore Comorian: shetwani class 9

- Maori: rēwera

- Marathi: सैतान m (saitān)

- Megleno-Romanian: drac

- Middle English: devel

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: буг (mn) (bug), чөтгөр (mn) (čötgör)

- Nepali: शैतान (śaitān)

- North Frisian: (Mooring, Föhr-Amrum) düüwel m

- Northern Altai: буг (bug), шедгер (šedger)

- Northern Ohlone: ‘uténmak

- Northern Sami: biro, vuoras, oinnolaš

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: djevel m

- Nynorsk: djevel m

- Occitan: diable (oc) m

- Ojibwe: maji-manidoo

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: бѣсъ m (běsŭ), дїаволъ m (diavolŭ), диꙗволъ m (dijavolŭ)

- Old East Slavic: чортъ m (čortŭ), бѣсъ m (běsŭ), диꙗволъ m (dijavolŭ)

- Old English: deofol n

- Old Norse: djǫfull m

- Old Persian: 𐎭𐎡𐎺 (daiva)

- Oriya: ଶୟତାନ (śôyôtanô)

- Ossetian: хӕйрӕг (xæjræg)

- Ottoman Turkish: شیطان (şeytan)

- Pashto: شيطان (ps) m (šaytān), ابليس (ps) m (eblis)

- Persian: دیو (fa) (div), ابلیس (fa) (eblis), شیطان (fa) (šeytân)

- Polish: diabeł (pl) m, bies (pl) m, czart (pl) m, czort (pl) m, ciort m, kaduk m (archaic), licho (pl) n, kusy (pl) m

- Portuguese: diabo (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਸ਼ੈਤਾਨ (pa) (śaitān)

- Quechua: supay (qu)

- Romani: beng m

- Romanian: drac (ro) m, diavol (ro) m, satană (ro) f, demon (ro) m, michiduță (ro) m

- Romansch: diavel m

- Russian: чёрт (ru) m (čort), дья́вол (ru) m (dʹjávol), бес (ru) m (bes), сатана́ (ru) m (sataná) (Satan), шайта́н (ru) m (šajtán) (Muslim)

- Sanskrit: पाप्मन् (sa) m (pāpman), पापीयस् (sa) m (pāpīyas), राक्षस (sa) m (rākṣasa), दानव (sa) m (dānava)

- Sardinian: diàbulu m, diàulu m, diàvulu m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: вра̑г m, ђа̏во̄ m, ђа̏вао m, ше́јта̄н m (Muslim)

- Roman: vrȃg (sh) m, đȁvō (sh) m, đȁvao (sh) m, šéjtān (sh) m (Muslim)

- Shor: айна

- Sicilian: diàvulu (scn) m

- Sinhalese: යක්ෂයා (yakṣayā)

- Slovak: diabol m, čert (sk) m

- Slovene: vrag (sl) m, hudič (sl) m

- Slovincian: čǻrnï bȯ́u̯g m, djɵ̏·u̯bĕl m

- Somali: sheydaan

- Southern Altai: шайтан (šaytan)

- Spanish: diablo (es) m

- Sundanese: sétan

- Swahili: ibilisi (sw), shetani (sw)

- Swedish: djävul (sv) c, jävel (sv) c

- Tajik: иблис (iblis), шайтон (tg) (šayton)

- Tamil: பேய் (ta) (pēy)

- Tatar: шайтан (tt) (şaytan), иблис (tt) (iblis)

- Telugu: సైతాను (te) (saitānu)

- Thai: ซาตาน (saa-dtaan), ปีศาจ (th) (bpii-sàat), มาร (th) (maan)

- Tibetan: བདུད (bdud)

- Tigrinya: ሰይጣን (säyṭan)

- Turkish: İblis, şeytan (tr)

- Turkmen: şeýtan, iblis

- Udmurt: шайтан (šajtan), пери (peri)

- Ukrainian: чорт m (čort), біс (uk) m (bis), дия́вол (uk) m (dyjávol), ді́дько m (dídʹko), сатана́ m (sataná)

- Urdu: شیطان m (śaitān), ابلیس (ur) m (iblīs)

- Uyghur: شەيتان (sheytan), ئىبلىس (iblis)

- Uzbek: shayton (uz), iblis (uz)

- Venetian: diavoło, diol, diauło, diaolo, diaoło, diaol, dial

- Vietnamese: ma (vi) (魔), quỷ (vi) (鬼 (vi))

- Volapük: (♂♀) diab (vo), (♂) hidiab, (♀) jidiab (vo), (obsolete) devel

- Walloon: diåle (wa) m

- Welsh: diafol m

- West Frisian: duvel

- Yiddish: טײַוול m (tayvl), שׂטן m (sotn), שד m (shed), רוח m (ruekh), נישט־גוטער m (nisht-guter)

Asked by: Rebecca Breitenberg

Score: 4.2/5

(21 votes)

Etymology. The Modern English word devil derives from the Middle English devel, from the Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of the Latin diabolus.

What does devil literally mean?

1 often capitalized : the most powerful spirit of evil. 2 : an evil spirit : demon, fiend. 3 : a wicked or cruel person. 4 : an attractive, mischievous, or unfortunate person a handsome devil poor devils.

What does the Greek word diabolos mean?

Diabolos (διάβολος), a Greek word often translated as Devil, may refer to: Diabolos (Gackt album), 2005. «Diabolos», a song by Balzac from Terrifying!

Who are the seven fallen angels?

The fallen angels are named after entities from both Christian and Pagan mythology, such as Moloch, Chemosh, Dagon, Belial, Beelzebub and Satan himself. Following the canonical Christian narrative, Satan convinces other angels to live free from the laws of God, thereupon they are cast out of heaven.

Who is Lucifer’s wife?

Lilith appears in Hazbin Hotel. She is the ex-wife (first wife) of Adam, the first human, wife of Lucifer, queen of hell, and mother of Charlie.

32 related questions found

Who is Lucifer’s father?

This page is about Lucifer’s father, commonly referred to as «God». for the current God, Amenadiel. God is a central character in Lucifer. He is one of the two co-creators of the Universe and the Father of all angels.

What is a diabolo toy?

The diabolo (/diːˈæbəloʊ/ dee-AB-ə-loh; commonly misspelled diablo) is a juggling or circus prop consisting of an axle (British English: bobbin) and two cups (hourglass/egg timer shaped) or discs derived from the Chinese yo-yo. This object is spun using a string attached to two hand sticks («batons» or «wands»).

What does Dia mean in Greek?

Dia (Ancient Greek: Δία or Δῖα, «heavenly», «divine» or «she who belongs to Zeus»), in ancient Greek religion and folklore, may refer to: Dia, a goddess venerated at Phlius and Sicyon.

What is Satan’s dog’s name?

It is generally depicted as a vicious, gargantuan dog with three heads, although accounts may vary. Cerberus is in fact the Latin transliteration of the Greek name Kerberos. In the earliest description of Cerberus, Hesiod’s Theogony, Cerberus has fifty heads, while Pindar gave him one hundred heads.

Who is Satan’s sister?

Satan’s Sister is a 1925 British silent adventure film directed by George Pearson and starring Betty Balfour, Guy Phillips and Philip Stevens. It is an adaptation of the 1921 novel Satan: A Romance of the Bahamas by Henry De Vere Stacpoole. The novel was later adapted again as the 1965 film The Truth About Spring.

What are good devils names?

The Infernal Names

- Abaddon—(Hebrew) the destroyer.

- Adramalech—Samarian devil.

- Ahpuch—Mayan devil.

- Ahriman—Mazdean devil.

- Amon—Egyptian ram-headed god of life and reproduction.

- Apollyon—Greek synonym for Satan, the arch fiend.

- Asmodeus—Hebrew devil of sensuality and luxury, originally «creature of judgment»

What is the root of the word devil?

Etymology. The Modern English word devil derives from the Middle English devel, from the Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of the Latin diabolus.

What is DIA in medical?

Dia-: Prefix meaning through, throughout, or completely, as in diachronic (over a period of time), diagnosis (to completely define the nature of a disease), and dialysis (cleansing the blood by passing it through a special machine).

What does Dia mean in Arabic?

Zia (also spelled Ziya, Ḍiya , Dia or Diya, Arabic: ضياء) is a name of Arabic origin meaning «light».

What does Prefix Ana mean?

Noun. -ana. Prefix. Latin, from Greek, up, back, again, from ana up — more at on.

Where is the Diablo from?

Diablo is an action role-playing hack and slash video game developed by Blizzard North and released by Blizzard Entertainment in January 1997. Set in the fictional Kingdom of Khanduras in the mortal realm, the player controls a lone hero battling to rid the world of Diablo, the Lord of Terror.

Why is a diabolo called a diabolo?

All this info: «The term «diabolo» was not taken from the Italian word for «devil» — «diavolo» — but was coined by French engineer Gustave Phillipart, who developed the modern diabolo in the early twentieth century[1], and derived the name from the Greek dia bolo, roughly meaning ‘across throw’.

What is diabolo made of?

A Diabolo – or Chinese yoyo, as they are sometimes referred to – is traditionally made of bamboo and wood. It is an empty roller, shaped like a dumbbell, which is spun and tossed on a string tied to two sticks, one held in each hand.

Who is God’s first son?

In Exodus, the nation of Israel is called God’s firstborn son. Solomon is also called «son of God». Angels, just and pious men, and the kings of Israel are all called «sons of God.» In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, «Son of God» is applied to Jesus on many occasions.

Who is Lucifer’s brother in the Bible?

When the Archangel Lucifer Morningstar began his revolt in Heaven, he was hopelessly outnumbered. He was eventually defeated by his brother the Archangel Michael who used the Demiurgos (God’s power) to destroy his angelic forces.

Who is Lucifer’s first love?

Lucifer, King of Hell, has taken his throne back in order to save his first true love, Detective Chloe Decker, and the rest of humanity from an apocalyptic prophecy.

What is the etymology of god?

The English word god comes from the Old English god, which itself is derived from the Proto-Germanic *ǥuđán. Its cognates in other Germanic languages include guþ, gudis (both Gothic), guð (Old Norse), god (Old Saxon, Old Frisian, and Old Dutch), and got (Old High German).

Who is the king of demons?

Asmodeus, Hebrew Ashmedai, in Jewish legend, the king of demons. According to the apocryphal book of Tobit, Asmodeus, smitten with love for Sarah, the daughter of Raguel, killed her seven successive husbands on their wedding nights.

English is a quirky language because it’s primarily a mix of two separate linguistic families — those languages that come from the Latin, particularly Old French, and those languages that come from the Germanic, particularly Anglo-Saxon. Sometimes two words from each of these branches look and sound very similar, but stem from completely different roots.

Such is the case with evil and devil. As you say, devil comes from the Old English deofol, from the Latin diabolus, which in turn derives from the Greek diabolos. Because of its use in the Church, it’s a word that has permeated many European languages, in much the same form, Portuguese: diabo, German: Teufel, Danish: djævel, Dutch: duivel, and so on.

Evil however is from the Old English yfel derived from the Proto-Germanic ubilaz. This is why the languages that derive from the same source have similar words: Dutch: onheil, German: übel, Danish/Norwegian/Swedish: ond/ont, and so on.

Meanwhile the languages in the Latin branch all have words for evil that derive from malus: Spanish/French/Portuguese: mal, Italian: male, and so on, as well as those English words that come from that branch: maleficent, malevolent, malediction, malignant,, and so on.

Long answer short: it’s a coincidence. But a fun one, nevertheless.

A Devil is an evil spirit in Abrahamic religion. In Judaism and Christianity the term devil is synonymous with both demon and fiend.[1][2][3] In Christianity, when the word devil is capitalized it can be used as a title for Satan.[1][3][4] In Islam the word devil used for shaitan,[5] which are described as unbelieving jinn.[6] Devil can also be a title for Satan in Islam.[5][6]

Etymology

The word devil began as a title or term for Satan by Greek speaking Christians and Jews.[7] The term satan in Hebrew means «the accuser,[8]» so Greek speaking Jews and Christians would use the word διαβάλλω (diabállō), derived from the word διαβάλλειν (diaballein), meaning «to slander, to attack, or to throw across, to scatter,» to describe Satan.[7]

In early Christian bibles the term διαβάλλω (diabállō) was specifically used to describe Satan while, δαίμων (daimōn) was used to describe demons.[7][9] In English and German bibles the terms were merged, creating the meaning most commonly used today.[7]

Modern Depictions

- In DnD and Pathfinder, devils are lawful evil,[10] but demons are chaotic evil.[11]

- The football club Manchester United is nicknamed as Red Devils.

- In Dragon Ball demon is the generic term for all infernal species alongside bad youkai, oni, and majin, but devils are just evil incarnations.

List of individuals who bear Devil title

- Aeshma

- Ahriman

- Asmodeus

- Astaroth

- Azazel

- Baphomet

- Beelzebub

- Belial

- Choronzon

- Al-Ḥāriṯ

- Krampus

- Lilith

- Lucifer

- Mara

- Marra

- Mastema

- Mephistopheles

- Samael

- Satan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Devil Definition & Meaning — Merriam-Webster

- ↑ https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/devil

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/devil

- ↑ https://www.dictionary.com/browse/devil

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://www.lexico.com/definition/shaitan

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 shaitan | Islamic mythology | Britannica

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 https://www.etymonline.com/word/devil

- ↑ https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Satan

- ↑ https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/diabolo

- ↑ https://online.anyflip.com/duex/ixpz/mobile/index.html#p=66

- ↑ https://online.anyflip.com/duex/ixpz/mobile/index.html#p=51

External links

- Devil — Britannica

By Anatoly Liberman

The Devil is uppermost in people’s thoughts, and his names are many. One of them is Old Nick. Its origin is obscure. The word nicker “water sprite,” explained as an old participle “(a) washed one,” is unrelated to it. Then there is nickel. The term was easy to coin, but copper could not be obtained from the nickel ore, and Axel F. von Cronstedt, a Swedish mineralogist despite von before Cronstedt, called the copper-colored metal copper nickel (German Kupfernickel), later shortened to nickel, after the name of a perfidious mountain demon (wolfram and especially cobalt have a similar history). Nickel was a bogyman or a dwarf, so that von Cronstedt hit on a term of abuse while thinking what to call the deceptive-looking ore. It is less clear why the creature was called Nickel. Later, figures resembling Nickel, disguised and frightening, were used on the eve of St. Nicholas’s day, which led to the confusion of Nickel and Nicholas; hence probably Old Nick.

The connection of the Devil with the name Robert, which has left a trace in the human imagination and art (Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable enjoyed great popularity in his day), is even more puzzling. Robert is, naturally, Rob, and since initial r– often alternates with h-, we have hob “sprite,” as an independent word and as the first element in hobgoblin and, by devious ways, if my etymology is correct, in hobbledehoy. Robin Goodfellow is another fiend. Good in his name owes its existence to taboo: propitiate an enemy, appease him, call him good, and he may leave you in peace. All kinds of flibbertigibbets and Rumpelstilzchens are evil but gullible. It is not fortuitous that Robin Hood, a folklore figure without a historical prototype, though not exactly a forest demon, and Robin Goodfellow are namesakes. We again have the big question unanswered: Why Robin/Robert? Proper names have given rise to hundreds of familiar words, and we can seldom explain the motivation behind the choice. Why john “lavatory,” jenny “skeleton key,” sloppy joe, and slippery jack (the latter is a tasty mushroom)? What did Richard do that dick has acquired an opprobrious meaning? By the way, Dick did not escape the snares of the Devil either. Along with Robert, Richard was among his names. The pet forms of Richard are, among others, Rick and Dick. From Dick we have Dickon, Dicken, and Dickens (-s is a typical suffix lending words a familiar flavor). Dickens is “devil,” but in this case we witness an ultimate triumph of human genius over the forces of evil. Charles Dickens has made the wiles of his “prototype” perfectly harmless. (The existence of such family names, though disturbing, is commonplace: compare German Teufel “devil” and Waldteufel “forest devil”; Emil Waldteufel, 1837-1915, was a popular composer of waltzes). Thus, we have a family consisting of Nick, Dick, and Hob. Old Harry, or Lord Harry, is also worthy of mention.

The supernatural creatures inhabiting mountains, forests, rivers, and so forth could strike awe in people when they made a lot of noise. The names of most giants known from Scandinavian oral tradition mean “screamer” and “howler.” Drolen, one of the Norwegian names of the Devil, is probably akin to troll, a sound-imitative word, like so many others beginning with dr- and tr-. The first part of Rumpelstilzchen is related to Engl. rumble, even though that mischievous imp neither rumbled nor thundered. But this should not cause surprise: people tend to forget the original meaning of words, and this is why we need etymological dictionaries. The –stilzchen element is a cognate of Engl. stilt (-chen is a diminutive suffix, as in Gretchen), so that the whole means something like “little rumble-wooden-leg.” Later, the name, in disregard of its inner form, was applied to a demon who hunted human babies.

The spirits of nature give mighty blows to human beings. Their pugnacity may supply a clue to the word deuce. What the deuce is a synonym of what the dickens. A homonym of deuce “devil” is deuce “two at dice or cards.” Deuce “two” goes back to Old French deus (Modern French deux), from Latin duos, the accusative of duo. Deuce “devil” is of Northern German origin, in which wat de duus..! has been recorded (in High German the phrase is was der Daus..!). English dictionaries suggest that deuce “devil” and deuce “two” are the same word. Allegedly, wat de duus was the exclamation by dicers on making the lowest throw (two), hardly a convincing etymology. There must have been a word duus “devil.” In the August gleanings, I discussed a possible origin of bulldoze(r) and traced, however tentatively, –doze to a verb meaning “strike” (Northern German dusen “beat, strike,” etc.), one of whose congeners is Engl. douse ~ dowse “strike (sail); immerse in water.” There may be a tie between duus and those verbs. Or perhaps duus is related to the words denoting stultification and weakness, such as Engl. dizzy and doze and Dutch dwaas “foolish.” This conjecture presupposes an earlier form *dwuus (there is a convention of putting an asterisk before hypothetical forms). Sometimes we discover only the root of the name we investigate. Such is rag(g)-, known in Swedish, Lithuanian, English (the first element of ragamuffin; its second element, -muff-in, also means “devil,” from the French word for “ugly”), and possibly Italian, if ragazzo “boy” formerly meant “imp” (this ragg– is not related to rag “a piece of cloth”) It would be strange if devils revealed their secrets without a good fight. They guard their names (remember Rumpelstilzchen?), lead people astray (remember Puck?), and parade as bogymen, boggarts and bugs. They also hide behind homonyms, but, although sometimes invisible, they are not invincible.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Detailed word origin of devil

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| diabolus | Latin (lat) | Devil. |

| dēoful | Old English (ca. 450-1100) (ang) | |

| deovel | Middle English (1100-1500) (enm) | |

| devil | English (eng) | To annoy or bother; to bedevil.. To finely grind cooked ham or other meat with spices and condiments.. To grill with cayenne pepper; to season highly in cooking, as with pepper.. To make like a devil; to invest with the character of a devil.. To prepare a sidedish of shelled halved boiled eggs to whose extracted yolks are added condiments and spices, which mixture then is placed into the […] |

The Temptation of Christ , Pacher Altar in St. Wolfgang (1471–1479)

The devil is an independent and supernatural being in various religions . He plays a special role in Christianity and Islam as the personification of evil . In Christian art he is often depicted as a black-winged angel or as a “junker” with a horse’s foot, in Islam a black figure symbolizes his corrupted nature. Mara or Devadatta takes the place of a «devilish» demon being in Buddhism .

Depending on the religion, cultural epoch and place, the devil is given different names.

Word origin

The word «devil» comes from the ancient Greek Διάβολος Diábolos, literally ‘jumble’ in the sense of ‘confounder, twisting facts, slanderer’ from διά dia ‘ throwing apart’ and βάλλειν bállein ‘throwing’, put together to διαβάλλειν disguises ; Latin diabolus .

The devil in different religions

Judaism

In the translation of the Hebrew texts of Job 1 EU and Zechariah 3 EU into Greek , the Jewish ha-Satan became diabolos (‘devil’) of the Septuagint . The conceptions of Satan in Judaism are clearly different from the conceptions and the use of the term Satan in Christianity and Islam. Due to the interpretation and interpretation of the Tanach by the respective scholars, there are significant differences.

In the Tanakh, Satan is primarily the title of accuser at the divine court of justice (the Hebrew term Satan (

שטן, Sin — Teth — Nun ) means something like «accuser»). The term can also be used for people, the Hebrew word is then generally used without the definite article ( 1 Samuel 29.4 EU ; 1 Kings 5.18 EU ; 11.14.23.25 EU ; Psalm 109.6 EU ; as verbs in the sense of “enemy” or “hostility” in the Psalms: Ps 38,21 EU ; 71,13 EU ; 109 EU ). Usually the title Satan is bestowed on different angels and can then be indicative on its own.

In Judaism, Satan is not seen as something personified or even as evil personified. In Judaism, both good and bad are seen as two sides of a togetherness that both z. B. are based in God, the eternal being. Good and bad are of this world, which is transcendent to God, the eternal being. Satan, when the title is given to an angel in a context or in a story, does not always act on his own authority and not according to his own will, but on behalf of God and is fully under the control and will of God. The title of Satan is given to various angels and people in the Tanakh and other sacred writings of Judaism.

The most detailed account of an angel with the title Satan working on God’s behalf can be found in the book of Job . The narrative begins with the scene at the heavenly court of justice where God and an angel are present. Because of the objection of the angel in this divine court, who acts as the accuser, i.e. as Satan , a reproach is made against God. The pious and prosperous Job is only faithful to God because God does not allow any misfortune around him. Then God allows Satan to test Job’s trust in God. Despite the misfortunes and in spite of the painful illness that overtook the unsuspecting Job on behalf of God, Job accepted his sad fate and did not curse his God . However, he criticizes him and insists that he has done nothing wrong. Job’s friends are convinced that he must have done wrong, because God does not allow an innocent man to suffer so much misfortune. This refutes the angel’s objection that there is no human being who remains loyal to God in every situation or who does not apostate from God as soon as he is doing badly from a human point of view. In two other cases, a Satan appears as a tempter ( 1. Chronicles 21.1 EU ) or accuser ( Zechariah 3.1 EU ) of sinful man before God. In Num 22,22-32 EU the angel (Satan) who stands in the way is ultimately not acting negatively, but is sent by God to prevent worse for Balaam .

In the extra-biblical popular Jewish stories of the European Middle Ages, the title Satan is sometimes given to an angel who is cast out by God because he wanted to make himself equal to God. The stories in which this happens are told juxtaposed in full awareness and knowledge of the teachings of Judaism, which always rejected such ideas. He is considered to be the bearer of the principle of evil. Here alludes to old terms of the Persian culture, in which the dual principle of the fight between good and evil plays a major role, and the ideas of the surrounding Christian culture. They are therefore rather fantastic stories or horror stories and not biblical Jewish teachings or didactic Jewish tales of tradition. It is possible that the ideas of Christianity will only be retold by way of illustration in order to present the positions of Christians that contradict those of Judaism.

The Qliphoth of the Kabbalistic cosmology are metaphorically understood as veiling bowls of the “spark of divine emanation” and fulfill similar functions as the devil figures in other religious systems. In Judaism, divinity is understood with the revelation of the only reality of God, which, however, is veiled by the Qliphoth. Qliphoth are therefore associated with idolatry, impurity, evil spiritual forces such as Samael and the accusing satans , and sources of spiritual, religious impurity.

Christianity

The Temptation of Eve, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1877)

In Christianity , the devil is the epitome of evil. He is also called (deviating from the Old Testament meaning of these names) Satan or Lucifer . The devil is seen as a fallen angel who rebelled against God .

The Christian tradition also often relates the serpent in the creation story to the devil. This equation can already be found in the Revelation of John . Traditionally, the devil is seen as the author of the lies and evil in the world. Revelation calls him the «great dragon, the old serpent called the devil or Satan and who deceives the whole world» ( Revelation 12.9 EU ). The letter to the Ephesians describes his work as «the rule of that spirit that rules in the air and is now still active in the disobedient». The devil is mentioned in detail in the apocryphal Ethiopian Book of Enoch as Azazel as one of those sons of God who with the daughters of man fathered the Nephilim , the «giants of ancient times».

Also in the New Testament, Satan is referred to as an angel who pretends to be the angel of light ( 2 Cor 11:14 EU ) and is presented as a personified spirit being who always acts as the devil. So it says: “He who commits sin is of the devil; for the devil sins from the beginning. But the Son of God appeared to destroy the works of the devil ”( 1 Jn 3 : 8 EU ).

In the book of Isaiah there is a song of mockery of the king of Babylon , a passage of which was later referred to by Christian tradition as Satan, but originally an allusion to the figure of Helel from the Babylonian religion , the counterpart to the Greek god Helios . The reference to the king is made clear at the beginning:

«Then you will sing this mocking song to the King of Babel: Oh, the oppressor came to an end, the need came to an end.»

“Oh, you fell from heaven, you radiant son of the dawn. You fell to the ground, you conqueror of the peoples. But you thought in your heart: I will climb heaven; up there I set up my throne, over the stars of God; I sit on the mountain of the assembly of gods, in the far north. I rise far above the clouds to be like the highest. »

The church fathers saw in this a parallel to the fall of Satan described in Lk 10.18 EU («He said to them: I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning»). A theological justification for the equation is that the city of Babylon in Revelation will be destroyed by God together with the devil on the last day. Others object that an assumed simultaneous annihilation does not mean identity.

In a similar way, parts of Ez 28 EU were also related to the fall of Satan. There the prophet speaks of the end of the king of Tire, who, because of his pride, considers himself a god and is therefore accused. In verses 14–15 it is said to the king: “You were a perfectly formed seal, full of wisdom and perfect beauty. You have been in the garden of God, in Eden. All sorts of precious stones surrounded you […] Everything that was exalted and deepened in you was made of gold, all these ornaments were attached when you were created. I joined you with a fellow with outspread, protective wings. You were on the holy mountain of the gods. You walked between the fiery stones. »

The parable of the weeds under the wheat, Mömpelgarder Altar (around 1540)

In the Gospels , Jesus refers to the devil in various parables, for example in the parable of the weeds under the wheat:

“And Jesus told them another parable: The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seeds in his field. Now while the people were sleeping, his enemy came, sowed weeds under the wheat, and went away again. As the seeds sprouted and the ears formed, the weeds also came out. Then the servants went to the landlord and said, Lord, did you not sow good seeds in your field? Then where did the weeds come from? He replied: An enemy of mine did that. Then the servants said to him, Shall we go and tear it up? He replied: No, otherwise you will uproot the wheat together with the weeds. Let both grow until the harvest. Then, when the time of harvest comes, I will tell the workers: First gather the weeds and tie them in bundles to burn; but bring the wheat into my barn. »

Before the millennial kingdom , according to the revelation of John, there is a fight between the archangel Michael and his angels and Satan, which ends with the devil and his followers being thrown to earth (fall from hell). For the duration of the thousand-year empire, however, he was tied up, only to be briefly released afterwards. He then seduces people for a certain time before he is thrown into a lake of fire ( Rev. 20 : 1–11 EU ).

A few Christian communities, such as the Christadelphians , the Church of the Blessed Hope or Christian Science , reject the idea of the existence of a devil or Satan as a real evil spirit.

Roman Catholic Church

The denial of evil ( Abrenuntiatio diaboli ) belongs in the Roman Catholic Church to the rite of baptism and to the renewal of baptismal promises in the celebration of Easter vigil . In the Catechism of the Catholic Church in 391–394 it says about Satan:

“Scripture testifies to the disastrous influence of him whom Jesus calls the ‘murderer from the beginning’ (Jn 8:44) and who even tried to dissuade Jesus from his mission received from the Father [cf. Mt 4,1-11]. ‘The Son of God appeared to destroy the works of the devil’ (1 Jn 3: 8). The most disastrous of these works was the lying deception that led people to disobey God.

However, the power of Satan is not infinite. He is just a creature; powerful because he is pure spirit, but only a creature: he cannot prevent the building of the kingdom of God. Satan is active in the world out of hatred of God and of his kingdom, which is based on Jesus Christ. His actions bring terrible spiritual and even physical damage to every person and every society. And yet this his doing is permitted by divine providence, which directs the history of man and the world powerfully and mildly at the same time. It is a great mystery that God allows the devil to do something, but ‘we know that God works everything to goodness with those who love him’ (Rom 8:28). »