English[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- enPR: bo͝ok, IPA(key): /bʊk/

- enPR: bo͞ok IPA(key): /buːk/ (Tyneside; otherwise obsolete)[1]

- plural

- Rhymes: -ʊk

- Homophone: buck (accents without the foot–strut split)

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English bok, book, from Old English bōc, from Proto-West Germanic *bōk, from Proto-Germanic *bōks. Eclipsed non-native Middle English livret, lyveret (“book, booklet”) from Old French livret (“book, booklet”). Bookmaker sense by clipping.

Alternative forms[edit]

- booke (archaic)

Noun[edit]

book (plural books)

- A collection of sheets of paper bound together to hinge at one edge, containing printed or written material, pictures, etc.

-

1610–1611 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tempest”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act I, scene ii], page 3, column 1:

-

Knowing I lou’d my bookes, he furniſhd me / From mine owne Library, with volumes, that / I prize aboue my Dukedome.

-

- 1962, James East Irby translating Luis Borges as «The Library of Babel»:

- I repeat: it suffices that a book be possible for it to exist. Only the impossible is excluded. For example: no book can be a ladder, although no doubt there are books which discuss and negate and demonstrate this possibility and others whose structure corresponds to that of a ladder.

- 1983, Steve Horelick & al., «Reading Rainbow»:

- I can be anything.

Take a look!

It’s in a book:

A reading rainbow.

- I can be anything.

- 1991, Stephen Fry, The Liar, page 51:

- Trefusis’s quarters could be described in one word. Books. Books and books and books. And then, just when an observer might be lured into thinking that that must be it, more books… Trefusis himself was highly dismissive of them. ‘Waste of trees,’ he had once said. ‘Stupid, ugly, clumsy, heavy things. The sooner technology comes up with a reliable alternative the better… The world is so fond of saying that books should be “treated with respect”. But when are we told that words should be treated with respect?’

-

She opened the book to page 37 and began to read aloud.

-

He was frustrated because he couldn’t find anything about dinosaurs in the book.

-

- A long work fit for publication, typically prose, such as a novel or textbook, and typically published as such a bound collection of sheets, but now sometimes electronically as an e-book.

-

I have three copies of his first book.

-

2022 December 6, Stephen Marche, quoting Sam Bankman-Fried, “The College Essay Is Dead”, in The Atlantic[1]:

-

“I would never read a book,” he once told an interviewer. “I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that.”

-

-

- A major division of a long work.

-

Genesis is the first book of the Bible.

-

Many readers find the first book of A Tale of Two Cities to be confusing.

- Synonyms: tome, volume

-

- (gambling) A record of betting (from the use of a notebook to record what each person has bet).

-

I’m running a book on who is going to win the race.

-

- (informal) A bookmaker (a person who takes bets on sporting events and similar); bookie; turf accountant.

- A convenient collection, in a form resembling a book, of small paper items for individual use.

-

a book of stamps

-

a book of raffle tickets

- Synonym: booklet

-

- (theater) The script of a musical or opera.

- Synonym: libretto

- 2010, David Baskerville, Tim Baskerville, Music Business Handbook and Career Guide (page 172)

- The guild helps ensure that the ownership and control of the music, lyrics, and book of a show remain in the hands of its authors and composers—not the producers.

- (usually in the plural) Records of the accounts of a business.

- Synonyms: account, record

- (law, colloquial) A book award, a recognition for receiving the highest grade in a class (traditionally an actual book, but recently more likely a letter or certificate acknowledging the achievement).

- (whist) Six tricks taken by one side.

- (poker slang) Four of a kind.[2]

- (sports) A document, held by the referee, of the incidents happened in the game.

- (sports, by extension) A list of all players who have been booked (received a warning) in a game.

-

2011 March 2, Andy Campbell, “Celtic 1 — 0 Rangers”, in BBC[2]:

-

Celtic captain Scott Brown joined team-mate Majstorovic in the book and Rangers’ John Fleck was also shown a yellow card as an ill-tempered half drew to a close.

-

-

- (cartomancy) The twenty-sixth Lenormand card.

- (figurative) Any source of instruction.

- (with «the») The accumulated body of knowledge passed down among black pimps.

- 1974, Adrienne Lanier Seward, The Black Pimp as a Folk Hero (page 11)

- The Book is an oral tradition of belief in The Life that has been passed down from player to player from generation to generation.

- 1994, Antiquarian Book Monthly (volume 21, page 36)

- On the other hand The Book is an oral tradition containing the rules and principles to be adopted by a pimp who wishes to be a player.

- 1974, Adrienne Lanier Seward, The Black Pimp as a Folk Hero (page 11)

- (advertising, informal) A portfolio of one’s previous work in the industry.

- 2017, Nik Mahon, Basics Advertising 02: Art Direction (page

- Getting your book (portfolio) organised is the first step, and knowing both what to include, and what to leave out, is an essential step towards achieving that important agency placement.

- Idea Industry (page 27)

- Your portfolio — your book — has to be killer.

- 2017, Nik Mahon, Basics Advertising 02: Art Direction (page

- (chess, uncountable) The sum of chess knowledge in the opening or endgame.

-

2018 April 6, Leonard Barden, “Chess: Schoolboy Vincent Keymer secures shock triumph at Grenke Open”, in The Guardian[3], archived from the original on 2023-01-12:

-

White to move and win. How can he do it? The BK plans a march to h8, eating the f4 pawn en route, for a book draw.

-

-

2020, Andrew Soltis, How to Swindle in Chess, Batsford Books, →ISBN:

-

This seems certain to simplify into a battle between White’s king, rook and two pawns against Black’s king and rook. In some cases a book draw is possible. But a book win is more likely.

-

-

Synonyms[edit]

- See Thesaurus:book

Hyponyms[edit]

- See Thesaurus:book

Derived terms[edit]

- address book

- audiobook

- back of the book

- book account

- book agent

- book-answerer

- book award

- book-bearer

- bookbinder

- book-board

- book-bosomed

- book-bound

- book-boy

- book-burning

- bookcase

- book-cloth

- book club

- book canvasser

- book concern

- book-crab

- book-credit

- book-debt

- book-edge gilder

- book-edge marbler

- book end

- bookend

- bookery

- booketeria

- book-farmer

- book-folder

- book-form

- bookful

- book-ghoul

- book-gill

- book hand

- book-holder

- bookhood

- bookhouse

- book-hunt

- bookie

- bookish

- bookism

- bookjacket

- bookkeeper

- bookkeeping

- book-label

- book-lare

- book launch

- book-law

- book-lear

- book-learned

- book-learning

- book-length

- bookless

- booklet

- booklike

- bookling

- booklore

- booklouse

- booklover

- book lover

- book lung

- bookly

- bookmaker

- bookmaking

- bookman

- bookmark

- bookmarker

- book match

- book-mate

- book-mindedness

- book mite

- bookmobile

- book-muslin

- book name

- book-number

- book-oath

- book of condolence

- book of first entry

- Book of God

- book of lading

- book of life

- book of original entry

- book of rates

- book of reference

- Book of the Dead

- book of the film

- book of the living

- book of words

- book-packet

- book piles

- bookplate

- book pocket

- book-post

- book-postage

- book-press

- book price

- book prop

- book-rate

- book-read

- bookrest

- bookroom

- book-scorpion

- bookseller

- bookselling

- bookshelf

- bookshop

- book-shy

- booksie

- book-slide

- book-society

- book-stack

- bookstaff

- bookstall

- book-stamp

- bookstand

- bookstore

- book support

- booksy

- book-table

- book token

- book trade

- book-tray

- book-trough

- book type

- book value

- bookwards

- book-ways

- bookwise

- bookwork

- book-world

- bookworm

- book-wright

- booky

- bring to book

- burn book

- by-book

- by the book

- casebook

- cashbook

- checkbook

- chequebook

- cheque book

- closed book

- close the books

- coffee table book

- coffee-table book

- comic book

- cookbook

- cookery book

- cook the books

- copybook

- coursebook

- e-book

- emblem book

- exercise book

- forebook

- fuck book

- Good Book

- guest book

- guidebook

- handbook

- hold the book

- hornbook

- hymn book

- in anyone’s book

- in my book

- in someone’s bad books

- in someone’s good books

- in the books

- keep the book

- know like a book

- logbook

- make book

- matchbook

- notebook

- off the books

- on the book

- on the books

- open book

- passbook

- pattern book

- pension book

- phrasebook

- pocketbook

- prayer book

- ration book

- read like a book

- reading book

- record book

- reference book

- rough book

- runbook

- scrapbook

- sketch book

- spellbook

- songbook

- storybook

- suit one’s book

- take a leaf out of someone’s book

- talk like a book

- textbook

- throw the book at

- visitors’ book

- without book

- Wizard Book

- wordbook

- workbook

- yearbook

- ABC book

- absey book

- absey-book

- account book

- activity book

- airport book

- alphabet book

- American comic book

- audio book

- audio-book

- autograph book

- baby book

- bath book

- birthday book

- block book

- blot one’s copy book

- blue book

- blue book exam

- board book

- book bin

- book burning

- book deal

- book debt

- book drop

- book dumping

- book entry

- book fair

- book in

- book it

- book keeping

- book knowledge

- book learning

- book lore

- book muslin

- book number

- book of business

- book of hours

- book of nature

- book of prime entry

- book of shadows

- book report

- book return

- book scorpion

- book shop

- book signing

- book smart

- book steak

- book store

- book tour

- book up

- book word

- book worm

- book-burner

- book-keep

- book-keeper

- book-keeping

- book-knowledge

- book-lore

- book-lung

- book-ridden

- book-signing

- book-smart

- book-teaching

- book-token

- book-wise

- book-word

- brag book

- by-the-book

- case book

- case-book

- chapter book

- close the book on

- closed-book

- coloring book

- colouring book

- commonplace book

- commonplace-book

- composition book

- cook book

- cost-book

- crack a book

- day book

- death book

- don’t judge a book by its cover

- Dutch book

- e-book reader

- edited book

- electronic book

- every trick in the book

- fake book

- field book

- field-book

- flip book

- form book

- friendship book

- funny book

- good book

- guard book

- guide book

- have more chins than a Chinese phone book

- history book

- hymn-book

- in one’s book

- joke book

- kiss the book

- know every trick in the book

- little black book

- log book

- log-book

- look book

- look-out book

- mag book

- make a book

- mug book

- murder book

- never judge a book by its cover

- note book

- off book

- off-book

- open book decomposition

- open-book

- open-book contract

- order book

- out of book

- paper book

- phone book

- phrase book

- phrase-book

- picture book

- pocket book

- pocket-book

- poll book

- rag book

- read like an open book

- recipe book

- red book

- regie-book

- rhyme book

- rime book

- rip a page out of someone’s book

- rough-book

- rule book

- rule-book

- run book

- school book

- scrap book

- slam book

- song book

- splat book

- squawk book

- statute book

- sticker book

- stroke book

- stud book

- stud-book

- take a page out of someone’s book

- talking book

- telephone book

- text-book

- the oldest trick in the book

- time-book

- toilet book

- trade book

- travel book

- turn up for the book

- turn-up for the book

- visitor’s book

- why buy a book when you can join a library

- why buy a book when you can join the library

- winter book

- write the book

- yardage book

- year-book

- you can’t judge a book by its cover

- you can’t tell a book by its cover

Descendants[edit]

- Sranan Tongo: buku

- Tok Pisin: buk

- → Rotokas: vuku

- → Chichewa: buku

- → Hawaiian: puke

- → Malagasy: boky

- → Maori: pukapuka (with reduplication)

- → Marshallese: bok

- → Motu: buka

- → Malagasy: boky

- → Shona: bhuku

- → Somali: buugga

- → Sotho: buka (possibly also from Afrikaans boek)

- → Zulu: ibhuku (possibly also from Afrikaans boek)

Translations[edit]

See also[edit]

- incunable

- scroll

- tome

- volume

Etymology 2[edit]

From Middle English booken, boken, from Old English bōcian, ġebōcian, from the noun (see above).

Verb[edit]

book (third-person singular simple present books, present participle booking, simple past and past participle booked)

- (transitive) To reserve (something) for future use.

-

I want to book a hotel room for tomorrow night.

-

I can book tickets for the concert next week.

-

2020 December 2, Paul Bigland, “My weirdest and wackiest Rover yet”, in Rail, page 68:

-

I haven’t booked, so I don’t have a clue as to whether the service will be busy or not. Supposedly, reservations are compulsory, but I want to find out what would happen if you just turn up.

-

- Synonym: reserve

-

- (transitive) To write down, to register or record in a book or as in a book.

- They booked that message from the hill

- Synonyms: make a note of, note down, record, write down

- (transitive) To add a name to the list of people who are participating in something.

- I booked a flight to New York.

- Synonyms: sign up, register, reserve, schedule, enroll

- (law enforcement, transitive) To record the name and other details of a suspected offender and the offence for later judicial action.

- The police booked him for driving too fast.

- (sports) To issue a caution to, usually a yellow card, or a red card if a yellow card has already been issued.

- (intransitive, slang) To travel very fast.

- He was really booking, until he passed the speed trap.

- Synonyms: bomb, hurtle, rocket, speed, shoot, whiz

- To record bets as bookmaker.

- (transitive, law student slang) To receive the highest grade in a class.

- The top three students had a bet on which one was going to book their intellectual property class.

- (intransitive, slang) To leave.

- He was here earlier, but he booked.

Derived terms[edit]

- block-book

- bookable

- booking

- double-book

- overbook

- rebook

- unbook

- underbook

Translations[edit]

Etymology 3[edit]

From Middle English book, bok, from Old English bōc, from Proto-Germanic *bōk, first and third person singular indicative past tense of Proto-Germanic *bakaną (“to bake”).

Verb[edit]

book

- (UK dialectal, Northern England) simple past tense of bake

References[edit]

- ^ “Book” in John Walker, A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary […] , London: Sold by G. G. J. and J. Robinſon, Paternoſter Row; and T. Cadell, in the Strand, 1791, →OCLC, page 118, column 2.

- ^ Weisenberg, Michael (2000) The Official Dictionary of Poker. MGI/Mike Caro University. →ISBN

Anagrams[edit]

- Boko, Koob, boko, bòkò, kobo

Chinese[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- 卜

Etymology[edit]

From English book.

Pronunciation[edit]

- Cantonese (Jyutping): buk1

- Cantonese

- (Standard Cantonese, Guangzhou–Hong Kong)+

- Jyutping: buk1

- Yale: būk

- Cantonese Pinyin: buk7

- Guangdong Romanization: bug1

- Sinological IPA (key): /pʊk̚⁵/

- (Standard Cantonese, Guangzhou–Hong Kong)+

Verb[edit]

book

- (Hong Kong Cantonese, colloquial) to book; to reserve

[edit]

- booking

Limburgish[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- bouk (Sittard, amongst other dialects)

- Bouk (Eupen)

- Bock (Krefeld)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle Low German bôk, from Old Saxon bōk, from Proto-West Germanic *bōk, from Proto-Germanic *bōks.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /boːk/

- Hyphenation: book

- Rhymes: -oːk

Noun[edit]

book n

- (many dialects) book

Declension[edit]

Declension of book (neuter) in Limburgish.

Derived terms[edit]

- bokebazel

- bokebijeinzeumering

- bokebon

- bokekas

- bokelies

- bokelègker

- bokemerret

- bokeplaank

- bokerèk

- bokestäönder

- boketaol

- bokewiesheid

- bokezin

- bookgesjef

- daagbook

- gastebook

- jaorbook

- kasbook

- kingerbook

- kookbook

- leesbook

- printebook

- receptebook

- waordebook

- wètbook

Mansaka[edit]

Noun[edit]

book

- piece

Middle English[edit]

Etymology 1[edit]

Noun[edit]

book

- Alternative form of bok

Etymology 2[edit]

Noun[edit]

book

- Alternative form of bouk

Norwegian Bokmål[edit]

Verb[edit]

book

- imperative of booke

English word book comes from Proto-Germanic *bōks (Book. Letter, written message.), Proto-Germanic *-ōną

You can also see our other etymologies for the English word book. Currently you are viewing the etymology of book with the meaning: (Verb) (intransitive, slang) To leave.. (intransitive, slang) To travel very fast.. (law enforcement, transitive) To record the name and other details of a suspected offender and the offence for later […](intransitive, slang) To leave.. (intransitive, slang) To travel very fast.. (law enforcement, transitive) To record the name and other details of a suspected offender and the offence for later […]

Detailed word origin of book

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| *bōks | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Book. Letter, written message. |

| *-ōną | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Creates denominative verbs from nouns.. Creates factitive verbs from adjectives. |

| *bōkōną | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | To book (i.e. make a book, put in a book, write a book, etc.). |

| ġebōcian | Old English (ang) | |

| boken | Middle English (enm) | |

| book | English (eng) | (intransitive, slang) To leave.. (intransitive, slang) To travel very fast.. (law enforcement, transitive) To record the name and other details of a suspected offender and the offence for later judicial action.. (sports) To issue with a caution, usually a yellow card, or a red card if a yellow card has already been issued.. (transitive) To reserve (something) for future use.. (transitive) To […] |

Words with the same origin as book

By Philip Durkin

The obvious answer to ‘when is a book a tree?’ is ‘before it’s been made into a book’ – it doesn’t take a scientist to know that (most) paper comes from trees – but things get more complex when we turn our attention to etymology.

The word book itself has changed very little over the centuries. In Old English it had the form bōc, and it is of Germanic origin, related to for example Dutch boek, German Buch, or Gothic bōka. The meaning has remained fairly steady too: in Old English a bōc was a volume consisting of a series of written and/or illustrated pages bound together for ease of reading, or the text that was written in such a volume, or a blank notebook, or sometimes another sort of written document, such as a charter.

The argument for…

The pages of books in Anglo-Saxon times were made out of parchment (i.e. animal skin), not paper. But nonetheless a long-standing and still widely accepted etymology assumes that the Germanic base of book is related ultimately to the name of the beech tree. Explanations of the semantic connection have varied considerably. At one point, scholars generally focused on the practice of scratching runes (the early Germanic writing system) onto strips of wood, but more recent accounts have placed emphasis instead on the use of wooden writing tablets.

Words in other languages have followed this semantic development from ‘material for writing on’ to ‘writing, book’. One example is classical Latin liber meaning ‘book’ (which is the root of library). This is believed to have originally been a use of liber meaning ‘bark’, the bark of trees having, according to Roman tradition, been used in early times as a writing material. Compare also Sanskrit bhūrjá- (as masculine noun) ‘birch tree’, and (as feminine noun) ‘birch bark used for writing’.

The argument against…

This explanation has troubled some scholars. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the words for ‘book’ and ‘beech’ in the earliest recorded stages of various Germanic languages belong to different stem classes (which determine how they form their endings for grammatical case and number), and the word for ‘book’ shows a stem class that is often assumed to be more archaic than that shown by the word for ‘beech’.

Secondly, in Gothic (the language of the ancient Goths, preserved in important early manuscripts) bōka in the singular (usually) means ‘letter (of the alphabet)’. In the plural, Gothic bōkōs does also mean ‘(legal) document, book’, but some have argued that this reflects a later development, modelled on ancient Greek γράμμα (gramma) ‘letter, written mark’, also in the plural γράμματα (grammata) ‘letters, literature’ (this word ultimately gives modern English grammar), and also on classical Latin littera ‘letter of the alphabet, short piece of writing’, also in the plural litterae ‘document, text, book’ (this word ultimately gives modern English literature).

In light of these factors, some have suggested that book and its Germanic relatives may show a different origin, from the same Indo-European base as Sanskrit bhāga- ‘portion, lot, possession’ and Avestan baga ‘portion, lot, luck’. The hypothesis is that a word of this origin came to be used in Germanic for a piece of wood with runes (or a single rune) inscribed on it, used to cast lots (a practice described by the ancient historian Tacitus), then for the runic characters themselves, and hence for Greek and Latin letters, and eventually for texts and books containing these.

However, many scholars remain convinced that book and beech are ultimately related, and argue that the forms and meanings shown in the earliest written documents in the various Germanic languages already reflect the results of a long process of development in word form and meaning, which has obscured the original relationship between the word book and the name of the tree. For some more detail on this, and for references to some of the main discussions of the etymology of book, see the etymology section of the entry for book in OED Online.

This article first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Philip Durkin is Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the author of Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English.

Language matters. At Oxford Dictionaries, we are committed to bringing you the benefit of our language expertise to help you connect with your world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

- Top Definitions

- Synonyms

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

a handwritten or printed work of fiction or nonfiction, usually on sheets of paper fastened or bound together within covers.

a work of fiction or nonfiction in an electronic format: Your child can listen to or read the book online.See also e-book (def. 1).

a number of sheets of blank or ruled paper bound together for writing, recording business transactions, etc.

a division of a literary work, especially one of the larger divisions.

the Book, the Bible.

Music. the text or libretto of an opera, operetta, or musical.

Jazz. the total repertoire of a band.

a script or story for a play.

a record of bets, as on a horse race.

Cards. the number of basic tricks or cards that must be taken before any trick or card counts in the score.

a set or packet of tickets, checks, stamps, matches, etc., bound together like a book.

anything that serves for the recording of facts or events: The petrified tree was a book of Nature.

Sports. a collection of facts and information about the usual playing habits, weaknesses, methods, etc., of an opposing team or player, especially in baseball: The White Sox book on Mickey Mantle cautioned pitchers to keep the ball fast and high.

Stock Exchange.

- the customers served by each registered representative in a brokerage house.

- a loose-leaf binder kept by a specialist to record orders to buy and sell stock at specified prices.

a pile or package of leaves, as of tobacco.

Mineralogy. a thick block or crystal of mica.

a magazine: used especially in magazine publishing.

the book,

- a set of rules, conventions, or standards: The solution was not according to the book but it served the purpose.

- the telephone book: I’ve looked him up, but he’s not in the book.

verb (used with object)

to enter in a book or list; record; register.

to reserve or make a reservation for (a hotel room, passage on a ship, etc.): We booked a table at our favorite restaurant.

to register or list (a person) for a place, transportation, appointment, etc.: The travel agent booked us for next week’s cruise.

to engage for one or more performances.

to enter an official charge against (an arrested suspect) on a police register.

to act as a bookmaker for (a bettor, bet, or sum of money): The Philadelphia syndicate books 25 million dollars a year on horse racing.

verb (used without object)

to register one’s name.

to engage a place, services, etc.

Slang.

- to study hard, as a student before an exam: He left the party early to book.

- to leave; depart: I’m bored with this party, let’s book.

- to work as a bookmaker: He started a restaurant with money he got from booking.

adjective

of or relating to a book or books: the book department;a book salesman.

derived or learned from or based on books: a book knowledge of sailing.

shown by a book of account: The firm’s book profit was $53,680.

Verb Phrases

book in, to sign in, as at a job.

book out, to sign out, as at a job.

book up, to sell out in advance: The hotel is booked up for the Christmas holidays.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Idioms about book

book it, Slang. See entry at book it.

bring to book, to call to account; bring to justice: Someday he will be brought to book for his misdeeds.

- to accept or place the bets of others, as on horse races, especially as a business.

- to wager; bet: You can make book on it that he won’t arrive in time.

- to sentence (an offender, lawbreaker, etc.) to the maximum penalties for all charges against that person.

- to punish or chide severely.

- from memory.

- without authority: to punish without book.

by the book, according to the correct or established form; in the usual manner: an unimaginative individual who does everything by the book.

close the books, to balance accounts at the end of an accounting period; settle accounts.

in one’s bad books, out of favor; disliked by someone: He’s in the boss’s bad books.

in one’s book, in one’s personal judgment or opinion: In my book, he’s not to be trusted.

in one’s good books, in favor; liked by someone.

like a book, completely; thoroughly: She knew the area like a book.

make book,

off the books, done or performed for cash or without keeping full business records: especially as a way to avoid paying income tax, employment benefits, etc.: Much of his work as a night watchman is done off the books.

one for the book / books, a noteworthy incident; something extraordinary: The daring rescue was one for the book.

on the books, entered in a list or record: He claims to have graduated from Harvard, but his name is not on the books.

throw the book at, Informal.

without book,

write the book, to be the prototype, originator, leader, etc., of: So far as investment banking is concerned, they wrote the book.

Origin of book

First recorded before 900; Middle English, Old English bōc; cognate with Dutch boek, Old Norse bōk, German Buch; akin to Gothic boka “letter (of the alphabet)” and not of known relation to beech, as is often assumed

OTHER WORDS FROM book

book·less, adjectivebook·like, adjectivepre·book, verbre·book, verb

un·booked, adjective

Words nearby book

boohai, boohoo, boo-hurrah theory, boojie, boojum tree, book, book bag, bookbinder, bookbindery, bookbinding, book burning

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to book

album, booklet, brochure, copy, dictionary, edition, essay, fiction, magazine, manual, novel, pamphlet, paperback, publication, text, textbook, tome, volume, work, writing

How to use book in a sentence

-

She waited for my rant to finish and then reminded me that the book, still in my hand, was one I had pulled from her own bookshelf.

-

I defy you to read the book—or, worse, review the Twitter commentary about it—and come away feeling good about the prospects for American comity.

-

Such deals aren’t typically part of Warren Buffett’s play book, although in 2018 Berkshire invested in the initial offering of Brazilian fintech StoneCo Ltd.

-

On the other side, in March everyone who booked a trip cancelled it.

-

More than two decades ago, I wrote a book with my New York Times colleagues Judith Miller and Bill Broad called “Germs” that looked at the modern history of biological warfare.

-

Yet this, in the end, is a book from which one emerges sad, gloomy, disenchanted, at least if we agree to take it seriously.

-

Submission is less a novel of ideas than a political book, and of the most subversive kind.

-

Her latest book, Heretic: The Case for a Muslim Reformation, will be published in April by HarperCollins.

-

At some point during his busy schedule, Israel found the time to write a book, titled The Global War on Morris.

-

My publisher had asked, “If you wanted to write another book, what would you want to write about?”

-

The supernaturalist alleges that religion was revealed to man by God, and that the form of this revelation is a sacred book.

-

But Mrs. Dodd, the present vicar’s wife, retained the precious prerogative of choosing the book to be read at the monthly Dorcas.

-

A small book, bound in full purple calf, lay half hidden in a nest of fine tissue paper on the dressing-table.

-

She did not need a great cook-book; She knew how much and what it took To make things good and sweet and light.

-

Again the sallow fingers began to play with the book-covers, passing from one to another, but always slowly and gently.

British Dictionary definitions for book

noun

a number of printed or written pages bound together along one edge and usually protected by thick paper or stiff pasteboard coversSee also hardback, paperback

- a written work or composition, such as a novel, technical manual, or dictionary

- (as modifier)the book trade; book reviews

- (in combination)bookseller; bookshop; bookshelf; bookrack

a number of blank or ruled sheets of paper bound together, used to record lessons, keep accounts, etc

(plural) a record of the transactions of a business or society

the script of a play or the libretto of an opera, musical, etc

a major division of a written composition, as of a long novel or of the Bible

a number of tickets, sheets, stamps, etc, fastened together along one edge

bookmaking a record of the bets made on a horse race or other event

(in card games) the number of tricks that must be taken by a side or player before any trick has a scoring valuein bridge, six of the 13 tricks form the book

strict or rigid regulations, rules, or standards (esp in the phrases according to the book, by the book)

a source of knowledge or authoritythe book of life

a telephone directory (in the phrase in the book)

the book (sometimes capital) the Bible

an open book a person or subject that is thoroughly understood

a closed book a person or subject that is unknown or beyond comprehensionchemistry is a closed book to him

bring to book to reprimand or require (someone) to give an explanation of his conduct

close the book on to bring to a definite endwe have closed the book on apartheid

close the books accounting to balance accounts in order to prepare a statement or report

cook the books informal to make fraudulent alterations to business or other accounts

in my book according to my view of things

in someone’s bad books regarded by someone with disfavour

in someone’s good books regarded by someone with favour

keep the books to keep written records of the finances of a business or other enterprise

on the books

- enrolled as a member

- registered or recorded

read someone like a book to understand a person, or his motives, character, etc, thoroughly and clearly

throw the book at

- to charge with every relevant offence

- to inflict the most severe punishment on

verb

to reserve (a place, passage, etc) or engage the services of (a performer, driver, etc) in advanceto book a flight; to book a band

(tr) to take the name and address of (a person guilty of a minor offence) with a view to bringing a prosecutionhe was booked for ignoring a traffic signal

(tr) (of a football referee) to take the name of (a player) who grossly infringes the rules while playing, two such acts resulting in the player’s dismissal from the field

(tr) archaic to record in a book

Word Origin for book

Old English bōc; related to Old Norse bōk, Old High German buoh book, Gothic bōka letter; see beech (the bark of which was used as a writing surface)

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Other Idioms and Phrases with book

see balance the books; black book; bring to book; by the book; closed book; close the books; cook the books; crack a book; hit the books; in one’s book; in someone’s bad graces (books); judge a book by its cover; know like a book; make book; nose in a book; one for the books; open book; take a leaf out of someone’s book; throw the book at; wrote the book on.

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

A book is a set or collection of written, printed, illustrated, or blank sheets, made of paper, parchment, or other material, usually fastened together to hinge at one side, and within protective covers. A single sheet within a book is called a leaf, and each side of a sheet is called a page. In today’s world, books that are produced electronically are called e-books, challenging the notion of a book as simply a materially-bound collection of pages.

The term ‘book’ may also refer to a literary work, or a main division of such a work. In library and information science, a book is called a monograph, to distinguish it from serial periodicals such as magazines, journals or newspapers. A lover of books is usually referred to as a bibliophile, a bibliophilist, or a philobiblist, or, more informally, a bookworm.

Books play a major role in the preservation of culture and tradition and the concept of printed words as scripture occupies a central role in various faith traditions.

History of books

Antiquity

When writing systems were invented in ancient civilizations, nearly everything that could be written upon—stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheets—was used for writing. Alphabetic writing emerged in Egypt around 1800 B.C.E. At first the words were not separated from each other (scripta continua) and there was no punctuation. Texts were written from right to left, left to right, and even so that alternate lines read in opposite directions.

Scroll

Papyrus, a form of paper made by weaving the stems of the papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool, was used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although the first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 B.C.E.).[1] Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. Tree bark such as lime (Latin liber, from there also library) and other materials were also used.[2]

According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the tenth or ninth century B.C.E. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos, through which papyrus was exported to Greece.[3]

Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper in East Asia, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese and Hebrew cultures. The codex form took over the Roman world by late antiquity, but lasted much longer in Asia.

Codex

Papyrus scrolls were still dominant in the first century AD, as witnessed by the findings in Pompeii. The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the century, where he praises its compactness. However the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.[4] This change happened gradually during the third and fourth centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan texts written on scrolls.

Wax tablets were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex).[5]The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[6]

In the fifth century, Isidore of Seville explained the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): «A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches.»

Middle Ages

Manuscripts

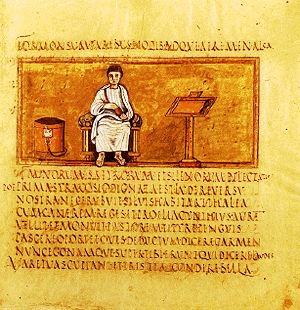

Folio 14 recto of the 5th century Vergilius Romanus contains an author portrait of Virgil. Note the bookcase (capsa), reading stand and the text written without word spacing in rustic capitals.

The fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century C.E. saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Papyrus became difficult to obtain, due to lack of contact with Egypt, and parchment, which had been used for centuries, began to be the main writing material.

Monasteries carried on the Latin writing tradition in the Western Roman Empire. Cassiodorus, in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540), stressed the importance of copying texts[7]. St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Regula Monachorum (completed around the middle of the 6th century) later also promoted reading.[8] The Rule of Saint Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages, and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. The tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated, but slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged.

Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, making books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only some dozen books, medium sized perhaps a couple hundred. By the ninth century, larger collections held around 500 volumes; and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.[9]

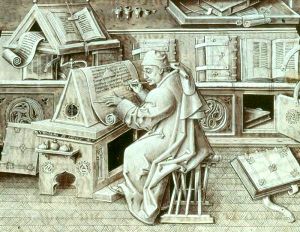

Burgundian scribe (portrait of Jean Miélot, from Miracles de Notre Dame), fifteenth century. The depiction shows the room’s furnishings, the writer’s materials, equipment, and activity.

The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house. Artificial light was forbidden, for fear it may damage the manuscripts. There were five types of scribes:

- Copyists, who dealt with basic production and correspondence

- Calligraphers, who dealt in fine book production

- Correctors, who collated and compared a finished book with the manuscript from which it had been produced

- Rubricators, who painted in the red letters

- Illuminators, who painted illustrations

The bookmaking process was long and laborious. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by the scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally the book was bound by the bookbinder.[10]

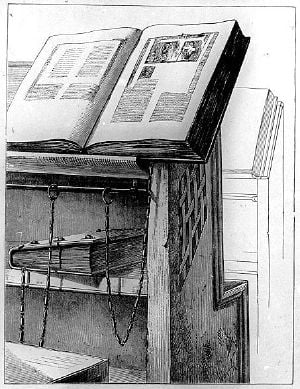

Desk with chained books in the Library of Cesena, Italy.

Different types of ink were known in antiquity, usually prepared from soot and gum, and later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing the typical brownish black color, but black or brown were not the only colours used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and different colours were used for illumination. Sometimes the whole parchment was coloured purple, and the text was written on it with gold or silver (eg Codex Argenteus).[11]

Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the seventh century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before the 12th century. It has been argued,[12] that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading.

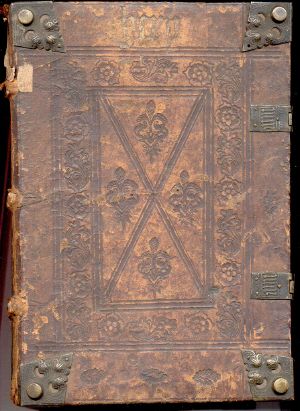

The first books used parchment or vellum (calf skin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. As dried parchment tends to assume the form before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During the later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. The so called libri catenati were used up to eighteenth century.

At first books were copied mostly in monasteries, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the thirteenth century, the Manuscript culture of the time lead to an increase in the demand for books, and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by stationers guilds, which were secular, and produced both religious and non-religious material.[13]

Wood block printing

A fifteenth century incunabulum. Notice the blind-tooled cover, corner bosses and clasps for holding the book shut.

In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. This method originated in China, in the Han dynasty (before 220 C.E.), as a method of printing on textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 C.E.).

The method (called Woodcut when used in art) arrived in Europe in the early fourteenth century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page; and the wood blocks tended to crack, if stored for long.

Movable type and incunabula

The Chinese inventor Pi Sheng made movable type of earthenware circa 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Metal movable type was invented in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (around 1230), but was not widely used: one reason being the enormous Chinese character set. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg introduced movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce, and more widely available.

Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before the year 1501 in Europe are known as incunabula. A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.[14]

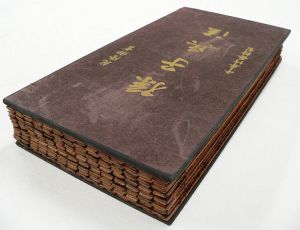

A Chinese bamboo book, in a collection at the University of California, Riverside.

Books in the Orient

China

Writing on bone, shells, wood, and silk existed in China by the second century B.C.E.. Paper was invented in China around the first century.

The discovery of the process using the bark of the blackberry bush is attributed to Ts’ai Louen, but it may be older. Texts were reproduced by woodblock printing; the diffusion of Buddhist texts was a main impetus to large-scale production. In the eleventh century, a blacksmith, Pi Cheng, invented movable type, but woodblock printing remained the main technique for books, possibly because of the poor quality of the ink. The Uyghurs of Turkistan also used movable type, as did the Koreans and Japanese.

The format of the book evolved in China in a similar way to that in Europe, but much more slowly, and with intermediate stages of scrolls folded concertina-style, scrolls bound at one edge («butterfly books») and so on. Printing was nearly always on one side of the paper only.

Modern world

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 1800s. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour, but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.

Monotype and linotype presses were introduced in the late nineteenth century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once.

The centuries after the fifteenth century were thus spent on improving both the printing press and the conditions for freedom of the press through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-twentieth century, European book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

Book structure

An uncut book; the pages must be separated before reading

The common structural parts of a book include:

- Front cover: hardbound or softcover (paperback); the spine is the binding that joins the front and rear covers where the pages hinge

- Front endpaper

- Flyleaf

- Front matter

- Frontispiece

- Title page

- Copyright page: typically verso of title page: shows copyright owner/date, credits, edition/printing, cataloging details

- Table of contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Body: the text or contents, the pages often collected or folded into signatures; the pages are usually numbered sequentially, and often divided into chapters.

- Back matter

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Index

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Colophon

- Flyleaf

- Rear endpaper

- Rear cover

Sizes

The size of a modern book is based on the printing area of a common flatbed press. The pages of type were arranged and clamped in a frame, so that when printed on a sheet of paper the full size of the press, the pages would be right side up and in order when the sheet was folded, and the folded edges trimmed.

The most common book sizes are:

- Quarto (4to): the sheet of paper is folded twice, forming four leaves (eight pages) approximately 11-13 inches (ca 30 cm) tall

- Octavo (8vo): the most common size for current hardcover books. The sheet is folded three times into eight leaves (16 pages) up to 9 ¾» (ca 23 cm) tall.

- DuoDecimo (12mo): a size between 8vo and 16mo, up to 7 ¾» (ca 18 cm) tall

- Sextodecimo (16mo): the sheet is folded four times, forming sixteen leaves (32 pages) up to 6 ¾» (ca 15 cm) tall

Sizes larger than quarto are:

- Folio: up to 15″ (ca 38 cm) tall.

- Elephant Folio: up to 23″ (ca 58 cm) tall.

- Atlas Folio: up to 25″ (ca 63 cm) tall.

- Double Elephant Folio: up to 50″ (ca 127 cm) tall.

Sizes smaller than 16mo are:

- 24mo: up to 5 ¾» (ca 13 cm) tall.

- 32mo: up to 5″ (ca 12 cm) tall.

- 48mo: up to 4″ (ca 10 cm) tall.

- 64mo: up to 3″ (ca 8 cm) tall.

Types of books

Small books can be called booklets.

Notebooks are blank books to be written in by the user. Students use them for taking notes. Scientists and other researchers use lab notebooks to record their work. Many notebooks are simply bound by a spiral coil at the edge so that pages can be easily torn out. Books to be partly filled in by the user include a personal address book, phone book, or calendar book for recording appointments, etc.

Albums are books for holding collections of memorabilia, pictures or photographs. They are often made so that the pages are removable. albums hold collections of stamps.

Books for recording periodic entries by the user, such as daily information about a journey, are called logbooks or simply logs. A similar book for writing daily the owner’s private personal events and information is called a diary.

Businesses use accounting books such as journals and ledgers to record financial data in a practice called bookkeeping.

Pre-printed school books for students to study are commonly called textbooks. Elementary school pupils often use workbooks which are published with spaces or blanks to be filled by them for study or homework.

A book with written prayers is called a prayerbook or missal. A book with a collection of hymns is called a hymnal.

In a library, a general type of non-fiction book which provides information as opposed to telling a story, essay, commentary, or otherwise supporting a point of view, is often referred to as a reference book. A very general reference book, usually one-volume, with lists of data and information on many topics is called an almanac. A more specific reference book with tables or lists of data and information about a certain topic, often intended for professional use, is often called a handbook. Books with technical information on how to do something or how to use some equipment are called manuals.

An encyclopedia is a book or set of books with articles on many topics. A book listing words, their etymology, meanings, etc. is called a dictionary. A book which is a collection of maps is an atlas. Books which try to list references and abstracts in a certain broad area may be called an index, such as Engineering Index, or abstracts such as Chemical Abstracts, Biological Abstracts, etc.

Bookmarks were used throughout the medieval period,[15] consisting usually of a small parchment strip attached to the edge of folio (or a piece of cord attached to headband). Bookmarks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were narrow silk ribbons bound into the book and become widespread in the 1850s. They were usually made from silk, embroidered fabrics or leather. Not until the 1880s, did paper and other materials become more common.

A book may be studied by students in the form of a book report. It may also be covered by a professional writer as a book review to introduce a new book. Some belong to a book club.

Books may also be categorized by their binding or cover. Hard cover books have a stiff binding. Paperback books have cheaper, flexible covers which tend to be less durable.

Publishing is a process for producing books, magazines, newspapers, etc. pre-printed for the reader/user to buy, usually in large numbers by a publishing company. Such books can be categorized as fiction (made-up stories) or non-fiction (information written as true). A book-length fiction story is called a novel.

Publishers may produce low-cost, pre-publication copies known as galleys or ‘bound proofs’ for promotional purposes, such as generating reviews in advance of publication. Galleys are usually made as cheaply as possible, since they are not intended for sale.

Collections of books

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books, (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. In ancient world the maintaining of a library was usually (but not exclusively) the privilege of a wealthy individual. These libraries could have been either private or public, i.e. for individuals that were interested in using them. The difference from a modern public library lies in the fact that they were usually not funded from public sources. It is estimated that in the city of Rome at the end of the third century there were around 30 public libraries, public libraries also existed in other cities of the ancient Mediterranean region (e.g., Library of Alexandria).[16] Later, in the Middle Ages, monasteries and universities had also libraries that could be accessible to general public. Typically not the whole collection was available to public, the books could not be borrowed and often were chained to reading stands to prevent theft.

Celsus Library was built in 135 C.E. and could house around 12,000 scrolls.

The beginning of modern public library begins around 15th century when individuals started to donate books to towns.[17] The growth of a public library system in the United States started in the late nineteenth century and was much helped by donations from Andrew Carnegie. This reflected classes in a society: The poor or the middle class had to access most books through a public library or by other means while the rich could afford to have a private library built in their homes.

The advent of paperback books in the 20th century led to an explosion of popular publishing. Paperback books made owning books affordable for many people. Paperback books often included works from genres that had previously been published mostly in pulp magazines. As a result of the low cost of such books and the spread of bookstores filled with them (in addition to the creation of a smaller market of extremely cheap used paperbacks) owning a private library ceased to be a status symbol for the rich.

In library and booksellers’ catalogues, it is common to include an abbreviation such as «Crown 8vo» to indicate the paper size from which the book is made.

When rows of books are lined on a bookshelf, bookends are sometimes needed to keep them from slanting.

Identification and classification

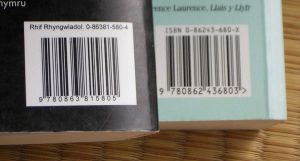

ISBN number with barcode.

During the twentieth century, librarians were concerned about keeping track of the many books being added yearly to the Gutenberg Galaxy. Through a global society called the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), they devised a series of tools including the International Standard Book Description or ISBD.

Each book is specified by an International Standard Book Number, or ISBN, which is unique to every edition of every book produced by participating publishers, world wide. It is managed by the ISBN Society. An ISBN has four parts: the first part is the country code, the second the publisher code, and the third the title code. The last part is a check digit, and can take values from 0–9 and X (10). The EAN Barcodes numbers for books are derived from the ISBN by prefixing 978, for Bookland, and calculating a new check digit.

Commercial publishers in industrialized countries generally assign ISBNs to their books, so buyers may presume that the ISBN is part of a total international system, with no exceptions. However many government publishers, in industrial as well as developing countries, do not participate fully in the ISBN system, and publish books which do not have ISBNs.

Books on library shelves with bookends, and call numbers visible on the spines

A large or public collection requires a catalogue. Codes called «call numbers» relate the books to the catalogue, and determine their locations on the shelves. Call numbers are based on a Library classification system. The call number is placed on the spine of the book, normally a short distance before the bottom, and inside.

Institutional or national standards, such as ANSI/NISO Z39.41 — 1997, establish the correct way to place information (such as the title, or the name of the author) on book spines, and on «shelvable» book-like objects, such as containers for DVDs, video tapes and software.

One of the earliest and most widely known systems of cataloguing books is the Dewey Decimal System. This system has fallen out of use in some places, mainly because of a Eurocentric bias and other difficulties applying the system to modern libraries. However, it is still used by most public libraries in America. The Library of Congress Classification system is more popular in academic libraries.

Classification systems

- Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)

- Library of Congress Classification (LCC)

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

- Harvard-Yenching Classification

Transition to digital format

The term e-book (electronic book) in the broad sense is an amount of information like a conventional book, but in digital form. It is made available through internet, CD-ROM, etc. In the popular press the term e-Book sometimes refers to a device such as the Sony Librie EBR-1000EP, which is meant to read the digital form and present it in a human readable form.

Throughout the twentieth century, libraries have faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the Internet means that much new information is not printed in paper books, but is made available online through a digital library, on CD-ROM, or in the form of e-books.

On the other hand, though books are nowadays produced using a digital version of the content, for most books such a version is not available to the public (i.e., neither in the library nor on the Internet), and there is no decline in the rate of paper publishing. There is an effort, however, to convert books that are in the public domain into a digital medium for unlimited redistribution and infinite availability. The effort is spearheaded by Project Gutenberg combined with Distributed Proofreaders.

There have also been new developments in the process of publishing books. Technologies such as print on demand have made it easier for less known authors to make their work available to a larger audience.

Paper and conservation issues

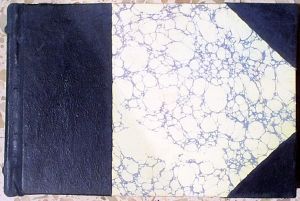

Halfbound book with leather and marbled paper.

Though papermaking in Europe had begun around the eleventh century, up until the beginning of sixteenth century vellum and paper were produced congruent to one another, vellum being the more expensive and durable option. Printers or publishers would often issue the same publication on both materials, to cater to more than one market.

Paper was first made in China, as early as 200 B.C.E., and reached Europe through Muslim territories. At first made of rags, the industrial revolution changed paper-making practices, allowing for paper to be made out of wood pulp.

Paper made from wood pulp was introduced in the early-nineteenth century, because it was cheaper than linen or abaca cloth-based papers. Pulp-based paper made books less expensive to the general public. This paved the way for huge leaps in the rate of literacy in industrialised nations, and enabled the spread of information during the Second Industrial Revolution.

However pulp paper contained acid, that eventually destroys the paper from within. Earlier techniques for making paper used limestone rollers, which neutralized the acid in the pulp. Books printed between 1850 and 1950 are at risk; more recent books are often printed on acid-free or alkaline paper. Libraries today have to consider mass deacidification of their older collections.

The proper care of books takes into account the possibility of physical and chemical damage to the cover and text. Books are best stored out of direct sunlight, in reduced lighting, at cool temperatures, and at moderate humidity. They need the support of surrounding volumes to maintain their shape, so it is desirable to shelve them by size.

See also

- Literature

- Library

Notes

- ↑ Leila Avrin. Scribes, script, and books: the book arts from antiquity to the Renaissance. (Chicago; London: American Library Association; The British Library, 1991. ISBN: 9780838905227), 83

- ↑ Dard Hunter. Papermaking: History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, New ed. (New York: Dover Publications, 1978), 12.

- ↑ Leila Avrin. Scribes, Script and Books, 144–145.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Eds. Frances Young, Lewis Ayres, Andrew Louth. (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 8–9.

- ↑ Leila Avrin. Scribes, Script and Books, p. 173.

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin palaeography antiquity and the Middle Ages, translated by David Ganz and Dáibhí ó Cróinin. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN: 0521364736), 11

- ↑ Leila Avrin. Scribes, Script and Books, 207–208.

- ↑ Theodore Maynard. Saint Benedict and His Monks. (Staples Press Ltd. 1956), 70–71.

- ↑ Martin D. Joachim. Historical Aspects of Cataloging and Classification. (Haworth Press, 2003), 452.

- ↑ Edith Diehl. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1980), 14–16.

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, 16–17.

- ↑ Paul Saenger. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. (Stanford University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff. Latin Palaeography, 42–43.

- ↑ Michael Clapham, «Printing» in A History of Technology, Vol 2. From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, ed. Charles Singer et al. (Oxford 1957), 377. Cited from Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge University, 1980).

- ↑ For a ninth century Carolingian bookmark see: J. A. Szirmai. The archaeology of medieval bookbinding. (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 1999. ISBN 0859679047), 123. For a fifteenth century bookmark see Medeltidshandskrift 34, (Lund University Library).

- ↑ Miriam A. Drake. Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. (Marcel Dekker, 2003), «Public Libraries, History».

- ↑ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library, «Public Libraries, History».

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Avrin, Leila. Scribes, script, and books: the book arts from antiquity to the Renaissance. Chicago; London: American Library Association; The British Library, 1991. ISBN 978-0838905227

- Bischoff, Bernhard. Latin palaeography antiquity and the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521364736

- Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique, reprint ed. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1980 (original 1946). ASIN B00126P58I B00126P58I

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. in 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979. ISBN 0521220440

- Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. reprint ed. Dover Publications, 1987 (original 1943).

- Joachim, Martin D. Historical Aspects of Cataloging and Classification. Haworth Press, 2003.

- Maynard, Theodore. Saint Benedict and His Monks. London: Staples Press Ltd, 1956.

- Saenger, Paul. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press, 2000 (original 1997). ISBN 0804726531

- Szirmai, J. A. The archeology of medieval bookbinding. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999. ISBN 0859679047

- Young, Frances, Lewis Ayres, and Andrew Louth, (eds.). The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521697506

External links

All links retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Information on Old Books Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

- Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Book history

- History_of_the_book history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Book»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Etymology of the word `book’ meaning `go’.

January 10, 2008 2:49 AM Subscribe

Another etymology question : what’s the origin of the term `book’ meaning `to go’. For example `Let’s book on outta here», or «I’m gonna book down to the 7-11».

I don’t hear this phrase a lot, but I do rather like it, and I have often wondered where it originated. Google fails me because of how common the word book is.

posted by tomble to Writing & Language (35 answers total) 1 user marked this as a favorite

I once heard that it was from the «Book ’em, Danno» at the end of Hawaii Five-O episodes, but I don’t know what my informant was basing that on.

posted by No-sword at 4:01 AM on January 10, 2008

Also, From here

«Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, Volume 1, A-G» by J.E. Lighter, Random House, New York, 1994.) Random House says «book it» is influenced by «boogie.»

posted by seanyboy at 4:06 AM on January 10, 2008

«Booking it» has been slang for running away (from trouble or a tight situation) for as long as I remember. I am talking late ’60s Boston…

posted by Gungho at 4:11 AM on January 10, 2008 [1 favorite]

Whoa, Gungho: Maybe it’s a Mass thing!

posted by lazywhinerkid at 4:14 AM on January 10, 2008

I grew up in Lexington MA in the 80s (born 78) and I concur with lazywhinerkid 100%.

posted by creasy boy at 4:19 AM on January 10, 2008

Central Indiana reporting; we used Let’s book as early as the 80s, too, however linguistic datapoint, we only used it in that form. Places where you might have used bookin’ it, we used bale(bail). I can’t give you a definitive spelling, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it were bale, since we’re a farm state, and baling hay tends to involve a metric buttload of throwing stuff as fast and hard as you can.

posted by headspace at 5:10 AM on January 10, 2008

Thirding (or something) the not-a-Mass thing, it was in wide use in California in the 60s.

posted by merelyglib at 5:17 AM on January 10, 2008

It’s known in Oklahoma, too. For me, it always has the connotation of haste- usually in leaving a tricky situation, as lazywhinerkid proposed. I don’t think I’ve ever heard it used in a case of «bookin’ it down to 7-11,» for instance, though I would understand it. It was always a case in which my best friend Kenny and I were about to get caught by his big sister doing something to her stuff, and one of us would turn to the other and say, «Book it!»

posted by Shohn at 5:33 AM on January 10, 2008

Fourthing «Book it!» as «Get out of here!», in Missouri. Certainly ’86, probably earlier.

posted by notsnot at 5:33 AM on January 10, 2008

Detroit, 1970s. «Book» was in common usage by many people I knew. Just to confirm it’s certainly been popular since before the 1990s.

posted by The Deej at 5:35 AM on January 10, 2008

I remember hearing this term in Northern California for the first time sometime around 1980. I don’t know where it came from, it just sort of appeared out of nowhere.

posted by Malor at 5:36 AM on January 10, 2008

Oh, there were three main usages. «Let’s book!» meant «run away!». «He’s booking!» meant he was running very fast. And «He can really book!» meant he was capable of doing so.

posted by Malor at 5:39 AM on January 10, 2008

Grew up in Massachusetts in the 70’s & 80’s and saying «bookin’ it» for running fast was very common. Never heard it after I moved away from New England.

posted by Koko at 6:51 AM on January 10, 2008

seanyboy has it, and (knowing it won’t do any good) I strongly emphasize that wild-ass guesses are totally useless in answering these questions. Lexicographers spend years learning how to do this, then spend their entire professional lives doing it; if you want to know where a word comes from, look in a book—in this case HDAS. If Lightner et al. suggest it’s related to boogie, that’s the best guess you’re going to get. On the question of age, the first citation in HDAS is from 1974: «Time to book this joint.» Of course, it had doubtless been used for at least a few years before that, and antedates will probably turn up.

posted by languagehat at 7:03 AM on January 10, 2008 [1 favorite]

This was common in Northeastern Ohio in the mid to late ’70’s as well.

posted by xena at 7:16 AM on January 10, 2008

Acton MA in the 80s. We said it all the time. Hi Koko and Jessamyn!

posted by Camofrog at 7:56 AM on January 10, 2008

«Bookin’ it» was also common in rural east TN in the late 70’s and early 80’s.

posted by kimdog at 8:48 AM on January 10, 2008

Oh, and «book» was used in Texas from at least the 80’s as well. I don’t see any particular geographic distribution here. It must have started somewhere, but considering the average MeFite age, it had probably become a nationwide word before most of us learned to speak.

posted by Bugbread at 8:59 AM on January 10, 2008

Brookline, MA, late 70s into the mid-80s, and we said «let’s book.» Never heard «bookin’ it,» to my recollection. (Hi, other Boston/MA/New England Mefites!)

posted by rtha at 9:20 AM on January 10, 2008

My intial `wild ass guess’ is that it’s derived from Hawaii Five-O, as others have suggested. «Alright, enough discussion, let’s write it down in a book. Dano, you do the writing.» can easily lead to «Alright, enough standing around, let’s get going now (let’s book it.)» They’re both a resolution for immediate action.

posted by proj08 at 9:54 AM on January 10, 2008

Wash DC area in early ’90s, Portland ME and parts of MA in the late 80s. College friends from eastern MA said both «let’s book» and «book it» more frequently than any other geographical group.

posted by LobsterMitten at 10:24 AM on January 10, 2008

I remember the term when I was a kid in the 70s and I always thought it was onomatopoeically related to the sound a jalopy or car with loud exhaust makes when it leaves rapidly «BOOKBOOKBOOKBOOKBOOKBOOK». In the 70s there were a lot of cars like that.

posted by zorro astor at 1:04 PM on January 10, 2008

Another datapoint: We said this on Long Island, NY, 80s.

posted by exlotuseater at 8:52 PM on January 10, 2008

Michigan, 1970’s. But usage did not imply speed. «Let’s book» was simply, let’s leave (or, «let’s make like a tree, and leaf»). Never heard «bookin’ it».

posted by Goofyy at 10:43 PM on January 10, 2008

« Older More sex & crime, please! | A good ‘ol-fashioned driver hunt Newer »

This thread is closed to new comments.