English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Russian Аля́ска (Aljáska, “Alaska”), in turn from Aleut alaxsxaq (“mainland”, literally “that toward which the action of the sea is directed”),[1] composed of alag (“pertaining to the sea”) + -sxa (nominalizing suffix, yields ‘the objective of action expressed by the root’) + -q (nominalizing suffix).[2]

Commonly misattributed to Russian ала (ala) + -ский (-skij, adjectival suffix).

Pronunciation[edit]

- enPR: ə-lăsʹkə, IPA(key): /əˈlæs.kə/

- Hyphenation: A‧las‧ka

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska

- A state of the United States, formerly a territory. Capital: Juneau. Postal code: AK, largest city: Anchorage.

- 1869, George Davidson, Pacific Coast. Coast Pilot of Alaska, (First Part,) From Southern Boundary to Cook’s Inlet. 1869, p. 32f.:

- We have no available sources of information concerning the vegetation northward of the peninsula of Alaska from Bristol Bay, in 58°, to the mouth of the Kwichpak, in latitude 63°.

- 1875, A History of the Wrongs of Alaska. An Appeal to the People and Press of America. Printed by Order of the Anti-Monopoly Association of the Pacific Coast. February, 1875, p. 3:

- Alaska was discovered about a century ago by Russian furhunters[.]

- 2004, Transformation of the U.S. Army Alaska: Final Environmental Impact Statement. Volume 1. Prepared For: United States Army Alaska Department of the Army. Prepared By: Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado, p. 3-108:

- Alaska‘s earliest inhabitants were nomadic hunters traveling in small bands. They arrived in interior Alaska at least 13,000 years ago […]

- 1869, George Davidson, Pacific Coast. Coast Pilot of Alaska, (First Part,) From Southern Boundary to Cook’s Inlet. 1869, p. 32f.:

- Several places in the United States, named for the state or territory.

- A township in Beltrami County, Minnesota.

- An unincorporated community in Morgan and Owen counties, Indiana.

- An unincorporated community in Cibola County, New Mexico.

- An unincorporated community in Jefferson County, Pennsylvania.

- An unincorporated community in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

- An unincorporated community in Fayette County, West Virginia.

- An unincorporated community in Kewaunee County, Wisconsin.

Derived terms[edit]

- Alaska hand

- Alaska pollock

- Alaska roll

- Alaska Standard Time

- Alaska time

- Alaska-like

- Alaskan

- baked Alaska

- Gulf of Alaska

- unAlaskan

Translations[edit]

US state

- Aleut: Alax̂sxax̂

- Alutiiq: Alas’kaaq

- Arabic: أَلَاسْكَا (ʔalāskā)

- Armenian: Ալյասկա (hy) (Alyaska)

- Azerbaijani: Alyaska (az)

- Belarusian: Аляска (Aljaska)

- Bulgarian: Аляска (bg) f (Aljaska)

- Catalan: Alaska f

- Cherokee: ᎠᎳᏍᎦ (alasga)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 阿拉斯加州 (zh) (Ālāsījiā zhōu)

- Czech: Aljaška (cs) f

- Danish: Alaska

- Dutch: Alaska (nl)

- Esperanto: Alasko

- Estonian: Alaska (et)

- Faroese: Alaska n

- Finnish: Alaska (fi)

- French: Alaska (fr) m

- Galician: Alasca (gl)

- Georgian: ალასკა (alasḳa)

- German: Alaska (de)

- Greek: Αλάσκα (el) f (Aláska)

- Hawaiian: ʻĀlaka

- Hebrew: אלסקה (he) (aláska)

- Hindi: अलास्का m (alāskā)

- Hungarian: Alaszka (hu)

- Icelandic: Alaska (is) n

- Indonesian: Alaska

- Inuktitut: ᐊᓛᓯᑲ (alaasika)

- Inupiaq: Alaska, Alaskaq, Alaasikaq

- Irish: Alasca

- Italian: Alaska (it) f, Alasca f

- Japanese: アラスカ州 (Arasuka-shū)

- Kannada: ಅಲಾಸ್ಕ (alāska)

- Kashmiri: अलास्का (alāskā)

- Khmer: អាឡាស្កា (ʼaalaaskaa)

- Korean: 알래스카 (Allaeseuka), 알라스카 (Allaseuka) (North Korea)

- Lakota: Osní Makȟóčhe (literally “cold land”)

- Latin: Alasca f

- Latvian: Aļaska

- Lithuanian: Aliaska

- Macedonian: Алјаска f (Aljaska)

- Malay: Alaska

- Maltese: l-Alaska

- Marathi: अलास्का m (alāskā)

- Navajo: Hakʼaz Dineʼé Bikéyah

- Northern Sami: Alaska

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: Alaska (no)

- Nynorsk: Alaska

- Occitan: Alaska (oc) f

- Ossetian: Аляскӕ (Aljaskæ)

- Persian: آلاسکا (fa) (âlâskâ)

- Polish: Alaska (pl) f

- Portuguese: Alasca (pt) m

- Romanian: Alaska (ro) f

- Russian: Аля́ска (ru) f (Aljáska)

- Sanskrit: अलास्का (alāskā)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: А̀љаска f

- Roman: Àljaska (sh) f

- Slovak: Aljaška (sk) f

- Slovene: Aljáska (sl) f

- Spanish: Alaska (es) f

- Swedish: Alaska (sv)

- Tagalog: Alaska

- Thai: อะแลสกา (à-lɛ́ɛs-gâa)

- Tlingit: Anáaski

- Turkish: Alaska (tr)

- Ukrainian: Аляска f (Aljaska)

- Uyghur: ئالياسكا (alyaska)

- Vietnamese: Alaska

- Volapük: Lalaskän (vo)

- Yiddish: אַלאַסקאַ (alaska)

- Yup’ik: Alaska

Noun[edit]

Alaska (plural Alaskas)

- Ellipsis of baked Alaska..

- 1879 December 5, George Augustus [Henry] Sala, “Fashion and Food in New York”, in America Revisited: From the Bay of New York to the Gulf of Mexico, and from Lake Michigan to the Pacific., volume I, London: Vizetelly & Co., 42, Catherine Street, Strand, published 1882, →OCLC; 3nd edition, London: Vizetelly & Co., 42, Catherine Street, Strand, 1883, →OCLC, page 90:

- I dined at Delmonico’s hard by the Fifth-avenue Hotel, a few nights ago; and among the dainties which that consummate caterer favoured us with, was an entremet called an «Alaska.» The «Alaska» is a baked ice. A beau mentir qui vient de loin; but this is no traveller’s tale. The nucleus or core of the entremet is an ice cream. This is surrounded by an envelope of carefully whipped cream, which, just before the dainty dish is served, is popped into the oven, or is brought under the scorching influence of a red hot salamander; so that its surface is covered with a light brown crust. So you go on discussing the warm cream soufflé till you come, with somewhat painful suddenness, on the row of ice.

-

2006 July, “Ice Cream: Some Great Stops, from Parlors to Gelaterias”, in Rebecca Burns, editor, Atlanta, volume 46, number 3, Atlanta, Ga., →ISSN, →OCLC, page 80:

-

Preparing the dessert, Dunlap pours a shallow pool of crème anglaise into a dish and adds an Alaska. Next he pours half Bacardi 151 rum («this one’s not for drinking,» he warns) and half root beer schnapps into a sauceboat. It’s show time! […] We dip the spoon into the Bacardi/schnapps mixture, and heat the spoon’s base with a mini torch. When the spoon goes back into the sauceboat, its contents ignite immediately. Yikes! Next, with our left hand, we pick up a long knife and place the tip firmly into the meringue-covered Alaska. Then, with our right, we pick up the flaming rum- and schnapps-filled sauceboat and pour it down the side of the knife. We gape as flaming liquid hits the dessert and encases it in flames. Oooh! Ahhh!

-

- 1879 December 5, George Augustus [Henry] Sala, “Fashion and Food in New York”, in America Revisited: From the Bay of New York to the Gulf of Mexico, and from Lake Michigan to the Pacific., volume I, London: Vizetelly & Co., 42, Catherine Street, Strand, published 1882, →OCLC; 3nd edition, London: Vizetelly & Co., 42, Catherine Street, Strand, 1883, →OCLC, page 90:

Alternative forms[edit]

- alaska

See also[edit]

| States: Alabama · Alaska · Arizona · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Delaware · Florida · Georgia · Hawaii · Idaho · Illinois · Indiana · Iowa · Kansas · Kentucky · Louisiana · Maine · Maryland · Massachusetts · Michigan · Minnesota · Mississippi · Missouri · Montana · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · North Carolina · North Dakota · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Pennsylvania · Rhode Island · South Carolina · South Dakota · Tennessee · Texas · Utah · Vermont · Virginia · Washington · West Virginia · Wisconsin · Wyoming |

| Federal District: Washington, D.C. |

| Territories: American Samoa · Guam · Northern Mariana Islands · Puerto Rico · United States minor outlying islands · United States Virgin Islands |

References[edit]

- ^ Douglas Harper (2001–2023), “Alaska”, in Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Ransom, J. Ellis (1940), “Derivation of the word ‘Alaska’”, in American Anthropologist, volume 42, issue 3, retrieved 2022-06-07, pages 550-551

Further reading[edit]

Alaska on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

Anagrams[edit]

- kalasa

Catalan[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska f

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

- Alaska Peninsula

Danish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from English Alaska.

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska (genitive Alaskas)

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Faroese[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From English Alaska, from Aleut alaxsxaq.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /aˈlaska/

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska n

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Declension[edit]

| Singular | |

| Indefinite | |

| Nominative | Alaska |

| Accusative | Alaska |

| Dative | Alaska |

| Genitive | Alaska |

Derived terms[edit]

- alaskalupin

Finnish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From English Alaska.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈɑlɑskɑ/, [ˈɑlɑs̠kɑ]

- Rhymes: -ɑlɑskɑ

- Syllabification(key): A‧las‧ka

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Declension[edit]

| Inflection of Alaska (Kotus type 12/kulkija, no gradation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| nominative | Alaska | — | |

| genitive | Alaskan | — | |

| partitive | Alaskaa | — | |

| illative | Alaskaan | — | |

| singular | plural | ||

| nominative | Alaska | — | |

| accusative | nom. | Alaska | — |

| gen. | Alaskan | ||

| genitive | Alaskan | — | |

| partitive | Alaskaa | — | |

| inessive | Alaskassa | — | |

| elative | Alaskasta | — | |

| illative | Alaskaan | — | |

| adessive | Alaskalla | — | |

| ablative | Alaskalta | — | |

| allative | Alaskalle | — | |

| essive | Alaskana | — | |

| translative | Alaskaksi | — | |

| instructive | — | — | |

| abessive | Alaskatta | — | |

| comitative | See the possessive forms below. |

| Possessive forms of Alaska (type kulkija) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anagrams[edit]

- Sakala, skaala

German[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from English Alaska, from Aleut alaxsxaq.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /aˈlaska/, [ʔäˈläs.kä], [ʔɐˈläs.kɐ]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska n (proper noun, genitive Alaskas or (optionally with an article) Alaska)

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

- the Alaska peninsula

Synonyms[edit]

- Alaschka

Icelandic[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From English Alaska, from Aleut alaxsxaq.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈaːlaska/

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska n

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Declension[edit]

declension of Alaska

| n-w | singular |

|---|---|

| indefinite | |

| nominative | Alaska |

| accusative | Alaska |

| dative | Alaska |

| genitive | Alaska |

Derived terms[edit]

- alaskaepli

- alaskalúpína

- alaskasýprus

- alaskavíðir

- alaskayllir

- alaskaösp

Italian[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska f

- Alternative spelling of Alasca

Norwegian Bokmål[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

[edit]

- alasker

- alaskisk

Norwegian Nynorsk[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

[edit]

- alaskar

- alaskisk

Polish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from English Alaska, from Aleut alaxsxaq.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /aˈlas.ka/

- Rhymes: -aska

- Syllabification: A‧las‧ka

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska f

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

- Mieszkam na Alasce. ― I live in Alaska.

Declension[edit]

Derived terms[edit]

- alaski

- alaskijski

- Alaskanin

- Alaskanka

- Alaskijczyk

- Alaskijka

Further reading[edit]

- Alaska in Wielki słownik języka polskiego, Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN

- Alaska in Polish dictionaries at PWN

Portuguese[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska m

- Alternative spelling of Alasca

Romanian[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska f

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Spanish[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /aˈlaska/ [aˈlas.ka]

- Rhymes: -aska

- Syllabification: A‧las‧ka

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska f

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

Derived terms[edit]

- alasquense, alaskeño, alasqueño

- malamute de Alaska

See also[edit]

Alaska on the Spanish Wikipedia.Wikipedia es

Swedish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from English Alaska. From Aleut alaxsxaq (“that toward which the action of the sea is directed”).

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska n (genitive Alaskas)

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

[edit]

- alaskier c (“person from Alaska”)

- alaskisk (“Alaskian”, adjective)

Anagrams[edit]

- kalasa

Tagalog[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from English Alaska.

Pronunciation[edit]

- Hyphenation: A‧las‧ka

- IPA(key): /ʔaˈlaska/, [ʔɐˈlas.kɐ]

Proper noun[edit]

Alaska

- Alaska (a state of the United States)

|

Alaska Alax̂sxax̂ (Aleut) |

|

|---|---|

|

State |

|

| State of Alaska | |

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nickname:

The Last Frontier |

|

| Motto:

North to the Future |

|

| Anthem: Alaska’s Flag | |

Map of the United States with Alaska highlighted |

|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Territory of Alaska |

| Admitted to the Union | January 3, 1959; 64 years ago (49th) |

| Capital | Juneau |

| Largest city | Anchorage |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Anchorage |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Mike Dunleavy (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Nancy Dahlstrom (R) |

| Legislature | Alaska Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Alaska Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators |

|

| U.S. House delegation | Mary Peltola (D) (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 663,268 sq mi (1,717,856 km2) |

| • Land | 571,951 sq mi (1,481,346 km2) |

| • Water | 91,316 sq mi (236,507 km2) 13.77% |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 1,420 mi (2,285 km) |

| • Width | 2,261 mi (3,639 km) |

| Elevation | 1,900 ft (580 m) |

| Highest elevation

(Denali[1]) |

20,310 ft (6,190.5 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population

(2020[3]) |

|

| • Total | 736,081 |

| • Rank | 48th |

| • Density | 1.26/sq mi (0.49/km2) |

| • Rank | 50th |

| • Median household income | $77,800[2] |

| • Income rank | 12th |

| Demonym | Alaskan |

| Language | |

| • Official languages | Ahtna, Alutiiq, Dena’ina, Deg Xinag, English, Eyak, Gwich’in, Haida, Hän, Holikachuk, Inupiaq, Koyukon, Lower Tanana, St. Lawrence Island Yupik, Tanacross, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Unangax̂, Upper Kuskokwim, Upper Tanana, Yup’ik |

| • Spoken language |

|

| Time zones | |

| east of 169°30′ | UTC−09:00 (Alaska) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−08:00 (ADT) |

| west of 169°30′ | UTC−10:00 (Hawaii-Aleutian) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−09:00 (HADT) |

| USPS abbreviation |

AK |

| ISO 3166 code | US-AK |

| Latitude | 51°20’N to 71°50’N |

| Longitude | 130°W to 172°E |

| Website | alaska.gov |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

Flag of Alaska |

|

Seal of Alaska |

|

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Willow ptarmigan |

| Dog breed | Alaskan Malamute |

| Fish | King salmon |

| Flower | Forget-me-not |

| Insect | Four-spot skimmer dragonfly |

| Mammal |

|

| Tree | Sitka Spruce |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Fossil | Woolly Mammoth |

| Gemstone | Jade |

| Mineral | Gold |

| Sport | Dog mushing |

| State route marker | |

|

|

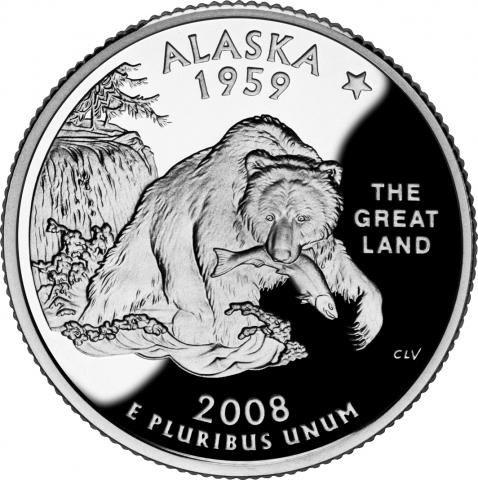

| State quarter | |

Released in 2008 |

|

| Lists of United States state symbols |

Interactive map showing border of Alaska (click to zoom)

Alaska ( ə-LAS-kə) is a U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., it borders British Columbia and the Yukon in Canada to the east, and it shares a western maritime border in the Bering Strait with the Russian Federation’s Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. To the north are the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas of the Arctic Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean lies to the south and southwest.

Alaska is the largest U.S. state by area, comprising more total area than the next three largest states of Texas, California, and Montana combined, and is the seventh-largest subnational division in the world. It is the third-least populous and most sparsely populated U.S. state, but with a population of 736,081 as of 2020, is the continent’s most populous territory located mostly north of the 60th parallel, more than quadruple the combined populations of Northern Canada and Greenland.[3] The state capital of Juneau is the second-largest city in the United States by area, and the former capital of Alaska, Sitka, is the largest U.S. city by area. Approximately half of Alaska’s residents live within the Anchorage metropolitan area.

Indigenous people have lived in Alaska for thousands of years, and it is widely believed that the region served as the entry point for the initial settlement of North America by way of the Bering land bridge. The Russian Empire was the first to actively colonize the area beginning in the 18th century, eventually establishing Russian America, which spanned most of the current state, and promoted and maintained a native Alaskan Creole population.[4] The expense and logistical difficulty of maintaining this distant possession prompted its sale to the U.S. in 1867 for US$7.2 million (equivalent to $140 million in 2021). The area went through several administrative changes before becoming organized as a territory on May 11, 1912. It was admitted as the 49th state of the U.S. on January 3, 1959.[5]

Abundant natural resources have enabled Alaska—with one of the smallest state economies—to have one of the highest per capita incomes, with commercial fishing, and the extraction of natural gas and oil, dominating Alaska’s economy. U.S. Armed Forces bases and tourism also contribute to the economy; more than half the state is federally-owned land containing national forests, national parks, and wildlife refuges.

The Indigenous population of Alaska is proportionally the highest of any U.S. state, at over 15 percent.[6] Various Indigenous languages are spoken, and Alaskan Natives are influential in local and state politics.

Etymology[edit]

The name «Alaska» (Russian: Аля́ска, tr. Alyáska) was introduced in the Russian colonial period when it was used to refer to the Alaska Peninsula. It was derived from an Aleut-language idiom, alaxsxaq, meaning «the mainland» or, more literally, «the object towards which the action of the sea is directed».[7][8][9]

History[edit]

Pre-colonization[edit]

A modern Alutiiq dancer in traditional festival garb

Numerous indigenous peoples occupied Alaska for thousands of years before the arrival of European peoples to the area. Linguistic and DNA studies done here have provided evidence for the settlement of North America by way of the Bering land bridge.[10] At the Upward Sun River site in the Tanana Valley in Alaska, remains of a six-week-old infant were found. The baby’s DNA showed that she belonged to a population that was genetically separate from other native groups present elsewhere in the New World at the end of the Pleistocene. Ben Potter, the University of Alaska Fairbanks archaeologist who unearthed the remains at the Upward Sun River site in 2013, named this new group Ancient Beringians.[11]

The Tlingit people developed a society with a matrilineal kinship system of property inheritance and descent in what is today Southeast Alaska, along with parts of British Columbia and the Yukon. Also in Southeast were the Haida, now well known for their unique arts. The Tsimshian people came to Alaska from British Columbia in 1887, when President Grover Cleveland, and later the U.S. Congress, granted them permission to settle on Annette Island and found the town of Metlakatla. All three of these peoples, as well as other indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, experienced smallpox outbreaks from the late 18th through the mid-19th century, with the most devastating epidemics occurring in the 1830s and 1860s, resulting in high fatalities and social disruption.[12]

The Aleutian Islands are still home to the Aleut people’s seafaring society, although they were the first Native Alaskans to be exploited by the Russians. Western and Southwestern Alaska are home to the Yup’ik, while their cousins the Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq live in what is now Southcentral Alaska. The Gwich’in people of the northern Interior region are Athabaskan and primarily known today for their dependence on the caribou within the much-contested Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The North Slope and Little Diomede Island are occupied by the widespread Inupiat people.

Colonization[edit]

Some researchers believe the first Russian settlement in Alaska was established in the 17th century.[13] According to this hypothesis, in 1648 several koches of Semyon Dezhnyov’s expedition came ashore in Alaska by storm and founded this settlement. This hypothesis is based on the testimony of Chukchi geographer Nikolai Daurkin, who had visited Alaska in 1764–1765 and who had reported on a village on the Kheuveren River, populated by «bearded men» who «pray to the icons». Some modern researchers associate Kheuveren with Koyuk River.[14]

The first European vessel to reach Alaska is generally held to be the St. Gabriel under the authority of the surveyor M. S. Gvozdev and assistant navigator I. Fyodorov on August 21, 1732, during an expedition of Siberian Cossack A. F. Shestakov and Russian explorer Dmitry Pavlutsky (1729–1735).[15] Another European contact with Alaska occurred in 1741, when Vitus Bering led an expedition for the Russian Navy aboard the St. Peter. After his crew returned to Russia with sea otter pelts judged to be the finest fur in the world, small associations of fur traders began to sail from the shores of Siberia toward the Aleutian Islands. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1784.

Between 1774 and 1800, Spain sent several expeditions to Alaska to assert its claim over the Pacific Northwest. In 1789, a Spanish settlement and fort were built in Nootka Sound. These expeditions gave names to places such as Valdez, Bucareli Sound, and Cordova. Later, the Russian-American Company carried out an expanded colonization program during the early-to-mid-19th century. Sitka, renamed New Archangel from 1804 to 1867, on Baranof Island in the Alexander Archipelago in what is now Southeast Alaska, became the capital of Russian America. It remained the capital after the colony was transferred to the United States. The Russians never fully colonized Alaska, and the colony was never very profitable. Evidence of Russian settlement in names and churches survive throughout southeastern Alaska.

William H. Seward, the 24th United States Secretary of State, negotiated the Alaska Purchase (also known as Seward’s Folly) with the Russians in 1867 for $7.2 million. Russia’s contemporary ruler Tsar Alexander II, the Emperor of the Russian Empire, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland, also planned the sale;[16] the purchase was made on March 30, 1867. Six months later the commissioners arrived in Sitka and the formal transfer was arranged; the formal flag-raising took place at Fort Sitka on October 18, 1867. In the ceremony 250 uniformed U.S. soldiers marched to the governor’s house at «Castle Hill», where the Russian troops lowered the Russian flag and the U.S. flag was raised. This event is celebrated as Alaska Day, a legal holiday on October 18.

Alaska was loosely governed by the military initially, and was administered as a district starting in 1884, with a governor appointed by the United States president. A federal district court was headquartered in Sitka. For most of Alaska’s first decade under the United States flag, Sitka was the only community inhabited by American settlers. They organized a «provisional city government», which was Alaska’s first municipal government, but not in a legal sense.[17] Legislation allowing Alaskan communities to legally incorporate as cities did not come about until 1900, and home rule for cities was extremely limited or unavailable until statehood took effect in 1959.

Alaska as an incorporated U.S. territory[edit]

Starting in the 1890s and stretching in some places to the early 1910s, gold rushes in Alaska and the nearby Yukon Territory brought thousands of miners and settlers to Alaska. Alaska was officially incorporated as an organized territory in 1912. Alaska’s capital, which had been in Sitka until 1906, was moved north to Juneau. Construction of the Alaska Governor’s Mansion began that same year. European immigrants from Norway and Sweden also settled in southeast Alaska, where they entered the fishing and logging industries.

U.S. troops navigate snow and ice during the Battle of Attu in May 1943

During World War II, the Aleutian Islands Campaign focused on Attu, Agattu and Kiska, all of which were occupied by the Empire of Japan.[a] During the Japanese occupation, a white American civilian and two United States Navy personnel were killed at Attu and Kiska respectively, and nearly a total of 50 Aleut civilians and eight sailors were interned in Japan. About half of the Aleuts died during the period of internment.[18] Unalaska/Dutch Harbor and Adak became significant bases for the United States Army, United States Army Air Forces and United States Navy. The United States Lend-Lease program involved flying American warplanes through Canada to Fairbanks and then Nome; Soviet pilots took possession of these aircraft, ferrying them to fight the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The construction of military bases contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities.

Statehood[edit]

Bob Bartlett and Ernest Gruening, Alaska’s inaugural U.S. Senators, hold the 49 star U.S. Flag after the admission of Alaska as the 49th state.

Statehood for Alaska was an important cause of James Wickersham early in his tenure as a congressional delegate. Decades later, the statehood movement gained its first real momentum following a territorial referendum in 1946. The Alaska Statehood Committee and Alaska’s Constitutional Convention would soon follow. Statehood supporters also found themselves fighting major battles against political foes, mostly in the U.S. Congress but also within Alaska. Statehood was approved by the U.S. Congress on July 7, 1958; Alaska was officially proclaimed a state on January 3, 1959.

Good Friday earthquake[edit]

On March 27, 1964, the massive Good Friday earthquake killed 133 people and destroyed several villages and portions of large coastal communities, mainly by the resultant tsunamis and landslides. It was the fourth-most-powerful earthquake in recorded history, with a moment magnitude of 9.2 (more than a thousand times as powerful as the 1989 San Francisco earthquake).[19] The time of day (5:36 pm), time of year (spring) and location of the epicenter were all cited as factors in potentially sparing thousands of lives, particularly in Anchorage.

Lasting four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, the magnitude 9.2 megathrust earthquake remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in North American history, and the second most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. Six hundred miles (970 km) of fault ruptured at once and moved up to 60 ft (18 m), releasing about 500 years of stress buildup. Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property. Anchorage sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, and infrastructure (paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment), particularly in the several landslide zones along Knik Arm. Two hundred miles (320 km) southwest, some areas near Kodiak were permanently raised by 30 feet (9 m). Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of Turnagain Arm near Girdwood and Portage dropped as much as 8 feet (2.4 m), requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the Seward Highway above the new high tide mark.

In Prince William Sound, Port Valdez suffered a massive underwater landslide, resulting in the deaths of 32 people between the collapse of the Valdez city harbor and docks, and inside the ship that was docked there at the time. Nearby, a 27-foot (8.2 m) tsunami destroyed the village of Chenega, killing 23 of the 68 people who lived there; survivors out-ran the wave, climbing to high ground. Post-quake tsunamis severely affected Whittier, Seward, Kodiak, and other Alaskan communities, as well as people and property in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.[20] Tsunamis also caused damage in Hawaii and Japan. Evidence of motion directly related to the earthquake was also reported from Florida and Texas.

Alaska had never experienced a major disaster in a highly populated area before, and had very limited resources for dealing with the effects of such an event. In Anchorage, at the urging of geologist Lidia Selkregg, the City of Anchorage and the Alaska State Housing Authority appointed a team of 40 scientists, including geologists, soil scientists, and engineers, to assess the damage done by the earthquake to the city.[21] The team, called the Engineering and Geological Evaluation Group, was headed by Dr. Ruth A. M. Schmidt, a geology professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage. The team of scientists came into conflict with local developers and downtown business owners who wanted to immediately rebuild; the scientists wanted to identify future dangers to ensure that rebuilt infrastructure would be safe.[22] The team produced a report on May 8, 1964, just a little more than a month after the earthquake.[21][23]

The United States military, which has a large active presence in Alaska, also stepped in to assist within moments of the end of the quake. The U.S. Army rapidly re-established communications with the lower 48 states, deployed troops to assist the citizens of Anchorage, and dispatched a convoy to Valdez.[24] On the advice of military and civilian leaders, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared all of Alaska a major disaster area the day after the quake. The U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard deployed ships to isolated coastal communities to assist with immediate needs. Bad weather and poor visibility hampered air rescue and observation efforts the day after the quake, but on Sunday the 29th the situation improved and rescue helicopters and observation aircraft were deployed.[24] A military airlift immediately began shipping relief supplies to Alaska, eventually delivering 2,570,000 pounds (1,170,000 kg) of food and other supplies.[25] Broadcast journalist, Genie Chance, assisted in recovery and relief efforts, staying on the KENI air waves over Anchorage for more than 24 continuous hours as the voice of calm from her temporary post within the Anchorage Public Safety Building.[26] She was effectively designated as the public safety officer by the city’s police chief.[26] Chance provided breaking news of the catastrophic events that continued to develop following the magnitude 9.2 earthquake, and she served as the voice of the public safety office, coordinating response efforts, connecting available resources to needs around the community, disseminating information about shelters and prepared food rations, passing messages of well-being between loved ones, and helping to reunite families.[27]

In the longer term, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers led the effort to rebuild roads, clear debris, and establish new townsites for communities that had been completely destroyed, at a cost of $110 million.[25] The West Coast and Alaska Tsunami Warning Center was formed as a direct response to the disaster. Federal disaster relief funds paid for reconstruction as well as financially supporting the devastated infrastructure of Alaska’s government, spending hundreds of millions of dollars that helped keep Alaska financially solvent until the discovery of massive oil deposits at Prudhoe Bay. At the order of the U.S. Defense Department, the Alaska National Guard founded the Alaska Division of Emergency Services to respond to any future disasters.[24]

Alaska oil boom[edit]

The 1968 discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay and the 1977 completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System led to an oil boom. Royalty revenues from oil have funded large state budgets from 1980 onward.

Oil production was not the only economic value of Alaska’s land, however. In the second half of the 20th century, Alaska discovered tourism as an important source of revenue. Tourism became popular after World War II, when military personnel stationed in the region returned home praising its natural splendor. The Alcan Highway, built during the war, and the Alaska Marine Highway System, completed in 1963, made the state more accessible than before. Tourism became increasingly important in Alaska, and today over 1.4 million people visit the state each year.[28]

With tourism more vital to the economy, environmentalism also rose in importance. The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980 added 53.7 million acres (217,000 km2) to the National Wildlife Refuge system, parts of 25 rivers to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system, 3.3 million acres (13,000 km2) to National Forest lands, and 43.6 million acres (176,000 km2) to National Park land. Because of the Act, Alaska now contains two-thirds of all American national parklands. Today, more than half of Alaskan land is owned by the Federal Government.[29]

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez hit a reef in the Prince William Sound, spilling more than 11 million US gallons (42 megalitres) of crude oil over 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of coastline. Today, the battle between philosophies of development and conservation is seen in the contentious debate over oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the proposed Pebble Mine.

Oil pooled on rocks on the shore of Prince William Sound after the oil spill.

Geography[edit]

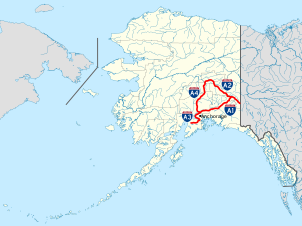

Located at the northwest corner of North America, Alaska is the northernmost and westernmost state in the United States, but also has the most easterly longitude in the United States because the Aleutian Islands extend into the Eastern Hemisphere.[30] Alaska is the only non-contiguous U.S. state on continental North America; about 500 miles (800 km) of British Columbia (Canada) separates Alaska from Washington. It is technically part of the continental U.S., but is sometimes not included in colloquial use; Alaska is not part of the contiguous U.S., often called «the Lower 48». The capital city, Juneau, is situated on the mainland of the North American continent but is not connected by road to the rest of the North American highway system.

The state is bordered by Canada’s Yukon and British Columbia to the east (making it the only state to only border a Canadian territory); the Gulf of Alaska and the Pacific Ocean to the south and southwest; the Bering Sea, Bering Strait, and Chukchi Sea to the west; and the Arctic Ocean to the north. Alaska’s territorial waters touch Russia’s territorial waters in the Bering Strait, as the Russian Big Diomede Island and Alaskan Little Diomede Island are only 3 miles (4.8 km) apart. Alaska has a longer coastline than all the other U.S. states combined.[31]

At 663,268 square miles (1,717,856 km2) in total area, Alaska is by far the largest state in the United States. Alaska is more than twice the size of the second-largest U.S. state (Texas), and it is larger than the next three largest states (Texas, California, and Montana) combined. Alaska is the seventh largest subnational division in the world. If it was an independent nation would be the 18th largest country in the world, almost the same size as Iran.

With its myriad islands, Alaska has nearly 34,000 miles (55,000 km) of tidal shoreline. The Aleutian Islands chain extends west from the southern tip of the Alaska Peninsula. Many active volcanoes are found in the Aleutians and in coastal regions. Unimak Island, for example, is home to Mount Shishaldin, which is an occasionally smoldering volcano that rises to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) above the North Pacific. The chain of volcanoes extends to Mount Spurr, west of Anchorage on the mainland. Geologists have identified Alaska as part of Wrangellia, a large region consisting of multiple states and Canadian provinces in the Pacific Northwest, which is actively undergoing continent building.

One of the world’s largest tides occurs in Turnagain Arm, just south of Anchorage, where tidal differences can be more than 35 feet (10.7 m).[32]

Alaska has more than three million lakes.[33] Marshlands and wetland permafrost cover 188,320 square miles (487,700 km2) (mostly in northern, western and southwest flatlands). Glacier ice covers about 28,957 square miles (75,000 km2) of Alaska.[34] The Bering Glacier is the largest glacier in North America, covering 2,008 square miles (5,200 km2) alone.[35]

Regions[edit]

There are no officially defined borders demarcating the various regions of Alaska, but there are six widely accepted regions:

South Central[edit]

The most populous region of Alaska, containing Anchorage, the Matanuska-Susitna Valley and the Kenai Peninsula. Rural, mostly unpopulated areas south of the Alaska Range and west of the Wrangell Mountains also fall within the definition of South Central, as do the Prince William Sound area and the communities of Cordova and Valdez.[36]

Southeast[edit]

Also referred to as the Panhandle or Inside Passage, this is the region of Alaska closest to the contiguous states. As such, this was where most of the initial non-indigenous settlement occurred in the years following the Alaska Purchase. The region is dominated by the Alexander Archipelago as well as the Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the United States. It contains the state capital Juneau, the former capital Sitka, and Ketchikan, at one time Alaska’s largest city.[37] The Alaska Marine Highway provides a vital surface transportation link throughout the area and country, as only three communities (Haines, Hyder and Skagway) enjoy direct connections to the contiguous North American road system.[38]

Interior[edit]

Denali is the highest peak in North America

The Interior is the largest region of Alaska; much of it is uninhabited wilderness. Fairbanks is the only large city in the region. Denali National Park and Preserve is located here. Denali, formerly Mount McKinley, is the highest mountain in North America, and is also located here.

Southwest[edit]

Southwest Alaska is a sparsely inhabited region stretching some 500 miles (800 km) inland from the Bering Sea. Most of the population lives along the coast. Kodiak Island is also located in Southwest. The massive Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta, one of the largest river deltas in the world, is here. Portions of the Alaska Peninsula are considered part of Southwest, with the remaining portions included with the Aleutian Islands (see below).

North Slope[edit]

The North Slope is mostly tundra peppered with small villages. The area is known for its massive reserves of crude oil and contains both the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska and the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field.[39] The city of Utqiaġvik, formerly known as Barrow, is the northernmost city in the United States and is located here. The Northwest Arctic area, anchored by Kotzebue and also containing the Kobuk River valley, is often regarded as being part of this region. However, the respective Inupiat of the North Slope and of the Northwest Arctic seldom consider themselves to be one people.[40]

Aleutian Islands[edit]

More than 300 small volcanic islands make up this chain, which stretches more than 1,200 miles (1,900 km) into the Pacific Ocean. Some of these islands fall in the Eastern Hemisphere, but the International Date Line was drawn west of 180° to keep the whole state, and thus the entire North American continent, within the same legal day. Two of the islands, Attu and Kiska, were occupied by Japanese forces during World War II.

Land ownership[edit]

According to an October 1998 report by the United States Bureau of Land Management, approximately 65% of Alaska is owned and managed by the U.S. federal government as public lands, including a multitude of national forests, national parks, and national wildlife refuges.[41] Of these, the Bureau of Land Management manages 87 million acres (35 million hectares), or 23.8% of the state. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. It is the world’s largest wildlife refuge, comprising 16 million acres (6.5 million hectares).

Of the remaining land area, the state of Alaska owns 101 million acres (41 million hectares), its entitlement under the Alaska Statehood Act. A portion of that acreage is occasionally ceded to the organized boroughs presented above, under the statutory provisions pertaining to newly formed boroughs. Smaller portions are set aside for rural subdivisions and other homesteading-related opportunities. These are not very popular due to the often remote and roadless locations. The University of Alaska, as a land grant university, also owns substantial acreage which it manages independently.

Another 44 million acres (18 million hectares) are owned by 12 regional, and scores of local, Native corporations created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971. Regional Native corporation Doyon, Limited often promotes itself as the largest private landowner in Alaska in advertisements and other communications. Provisions of ANCSA allowing the corporations’ land holdings to be sold on the open market starting in 1991 were repealed before they could take effect. Effectively, the corporations hold title (including subsurface title in many cases, a privilege denied to individual Alaskans) but cannot sell the land. Individual Native allotments can be and are sold on the open market, however.

Various private interests own the remaining land, totaling about one percent of the state. Alaska is, by a large margin, the state with the smallest percentage of private land ownership when Native corporation holdings are excluded.

Alaska Heritage Resources Survey[edit]

The Alaska Heritage Resources Survey (AHRS) is a restricted inventory of all reported historic and prehistoric sites within the U.S. state of Alaska; it is maintained by the Office of History and Archaeology. The survey’s inventory of cultural resources includes objects, structures, buildings, sites, districts, and travel ways, with a general provision that they are more than fifty years old. As of 31 January 2012, more than 35,000 sites have been reported.[42]

Cities, towns and boroughs[edit]

Utqiaġvik (Browerville neighborhood near Eben Hopson Middle School shown), known colloquially for many years by the nickname «Top of the World», is the northernmost city in the United States.

Alaska is not divided into counties, as most of the other U.S. states, but it is divided into boroughs.[43] Delegates to the Alaska Constitutional Convention wanted to avoid the pitfalls of the traditional county system and adopted their own unique model.[44] Many of the more densely populated parts of the state are part of Alaska’s 16 boroughs, which function somewhat similarly to counties in other states. However, unlike county-equivalents in the other 49 states, the boroughs do not cover the entire land area of the state. The area not part of any borough is referred to as the Unorganized Borough.

The Unorganized Borough has no government of its own, but the U.S. Census Bureau in cooperation with the state divided the Unorganized Borough into 11 census areas solely for the purposes of statistical analysis and presentation. A recording district is a mechanism for management of the public record in Alaska. The state is divided into 34 recording districts which are centrally administered under a state recorder. All recording districts use the same acceptance criteria, fee schedule, etc., for accepting documents into the public record.

Whereas many U.S. states use a three-tiered system of decentralization—state/county/township—most of Alaska uses only two tiers—state/borough. Owing to the low population density, most of the land is located in the Unorganized Borough. As the name implies, it has no intermediate borough government but is administered directly by the state government. In 2000, 57.71% of Alaska’s area has this status, with 13.05% of the population.[45]

Anchorage merged the city government with the Greater Anchorage Area Borough in 1975 to form the Municipality of Anchorage, containing the city proper and the communities of Eagle River, Chugiak, Peters Creek, Girdwood, Bird, and Indian. Fairbanks has a separate borough (the Fairbanks North Star Borough) and municipality (the City of Fairbanks).

The state’s most populous city is Anchorage, home to 291,247 people in 2020.[46] The richest location in Alaska by per capita income is Denali ($42,245). Yakutat City, Sitka, Juneau, and Anchorage are the four largest cities in the U.S. by area.

Cities and census-designated places (by population)[edit]

As reflected in the 2020 United States census, Alaska has a total of 355 incorporated cities and census-designated places (CDPs).[47] The tally of cities includes four unified municipalities, essentially the equivalent of a consolidated city–county. The majority of these communities are located in the rural expanse of Alaska known as «The Bush» and are unconnected to that contiguous North American road network. The table at the bottom of this section lists about the 100 largest cities and census-designated places in Alaska, in population order.

Of Alaska’s 2020 U.S. census population figure of 733,391, 16,655 people, or 2.27% of the population, did not live in an incorporated city or census-designated place.[46] Approximately three-quarters of that figure were people who live in urban and suburban neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city limits of Ketchikan, Kodiak, Palmer and Wasilla. CDPs have not been established for these areas by the United States Census Bureau, except that seven CDPs were established for the Ketchikan-area neighborhoods in the 1980 Census (Clover Pass, Herring Cove, Ketchikan East, Mountain Point, North Tongass Highway, Pennock Island and Saxman East), but have not been used since. The remaining population was scattered throughout Alaska, both within organized boroughs and in the Unorganized Borough, in largely remote areas.

|

|

Climate[edit]

Alaska has largest acreage of public land owned by the federal government than any other state.[48]

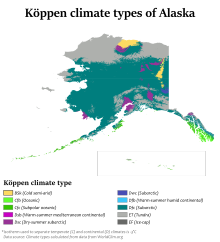

The climate in south and southeastern Alaska is a mid-latitude oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), and a subarctic oceanic climate (Köppen Cfc) in the northern parts. On an annual basis, the southeast is both the wettest and warmest part of Alaska with milder temperatures in the winter and high precipitation throughout the year. Juneau averages over 50 in (130 cm) of precipitation a year, and Ketchikan averages over 150 in (380 cm).[49] This is also the only region in Alaska in which the average daytime high temperature is above freezing during the winter months.

The climate of Anchorage and south central Alaska is mild by Alaskan standards due to the region’s proximity to the seacoast. While the area gets less rain than southeast Alaska, it gets more snow, and days tend to be clearer. On average, Anchorage receives 16 in (41 cm) of precipitation a year, with around 75 in (190 cm) of snow, although there are areas in the south central which receive far more snow. It is a subarctic climate (Köppen: Dfc) due to its brief, cool summers.

The climate of western Alaska is determined in large part by the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska. It is a subarctic oceanic climate in the southwest and a continental subarctic climate farther north. The temperature is somewhat moderate considering how far north the area is. This region has a tremendous amount of variety in precipitation. An area stretching from the northern side of the Seward Peninsula to the Kobuk River valley (i.e., the region around Kotzebue Sound) is technically a desert, with portions receiving less than 10 in (25 cm) of precipitation annually. On the other extreme, some locations between Dillingham and Bethel average around 100 in (250 cm) of precipitation.[50]

The climate of the interior of Alaska is subarctic. Some of the highest and lowest temperatures in Alaska occur around the area near Fairbanks. The summers may have temperatures reaching into the 90s °F (the low-to-mid 30s °C), while in the winter, the temperature can fall below −60 °F (−51 °C). Precipitation is sparse in the Interior, often less than 10 in (25 cm) a year, but what precipitation falls in the winter tends to stay the entire winter.

The highest and lowest recorded temperatures in Alaska are both in the Interior. The highest is 100 °F (38 °C) in Fort Yukon (which is just 8 mi or 13 km inside the arctic circle) on June 27, 1915,[51][52] making Alaska tied with Hawaii as the state with the lowest high temperature in the United States.[53][54] The lowest official Alaska temperature is −80 °F (−62 °C) in Prospect Creek on January 23, 1971,[51][52] one degree above the lowest temperature recorded in continental North America (in Snag, Yukon, Canada).[55]

The climate in the extreme north of Alaska is Arctic (Köppen: ET) with long, very cold winters and short, cool summers. Even in July, the average low temperature in Utqiaġvik is 34 °F (1 °C).[56] Precipitation is light in this part of Alaska, with many places averaging less than 10 in (25 cm) per year, mostly as snow which stays on the ground almost the entire year.

| Location | July (°F) | July (°C) | January (°F) | January (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage | 65/51 | 18/10 | 22/11 | −5/−11 |

| Juneau | 64/50 | 17/11 | 32/23 | 0/−4 |

| Ketchikan | 64/51 | 17/11 | 38/28 | 3/−1 |

| Unalaska | 57/46 | 14/8 | 36/28 | 2/−2 |

| Fairbanks | 72/53 | 22/11 | 1/−17 | −17/−27 |

| Fort Yukon | 73/51 | 23/10 | −11/−27 | −23/−33 |

| Nome | 58/46 | 14/8 | 13/−2 | −10/−19 |

| Utqiaġvik | 47/34 | 08/1 | −7/−19 | −21/−28 |

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 33,426 | — | |

| 1890 | 32,052 | −4.1% | |

| 1900 | 63,592 | 98.4% | |

| 1910 | 64,356 | 1.2% | |

| 1920 | 55,036 | −14.5% | |

| 1930 | 59,278 | 7.7% | |

| 1940 | 72,524 | 22.3% | |

| 1950 | 128,643 | 77.4% | |

| 1960 | 226,167 | 75.8% | |

| 1970 | 300,382 | 32.8% | |

| 1980 | 401,851 | 33.8% | |

| 1990 | 550,043 | 36.9% | |

| 2000 | 626,932 | 14.0% | |

| 2010 | 710,231 | 13.3% | |

| 2020 | 733,391 | 3.3% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 733,583 | 0.0% | |

| 1930 and 1940 censuses taken in preceding autumn Sources: 1910–2020[58] |

The United States Census Bureau found in the 2020 United States census that the population of Alaska was 733,391 on April 1, 2020, a 3.3% increase since the 2010 United States census.[3] According to the 2010 United States census, the U.S. state of Alaska had a population of 710,231, a 13.3% increase from 626,932 at the 2000 U.S. census.

In 2010, Alaska ranked as the 47th state by population, ahead of North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming (and Washington, D.C.). Estimates show North Dakota ahead as of 2018.[59] Alaska is the least densely populated state, and one of the most sparsely populated areas in the world, at 1.2 inhabitants per square mile (0.46/km2), with the next state, Wyoming, at 5.8 inhabitants per square mile (2.2/km2).[60] Alaska is by far the largest U.S. state by area, and the tenth wealthiest (per capita income).[61] As of 2018 due to its population size, it is one of 14 U.S. states that still have only one telephone area code.[62]

According to HUD’s 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,320 homeless people in Alaska.[63] [64]

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| Racial composition | 1970[65] | 1990[65] | 2000[66] | 2010[67] | 2020[68] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 78.8% | 75.5% | 69.3% | 66.7% | 59.4% |

| Native | 16.9% | 15.6% | 15.6% | 14.8% | 15.2% |

| Asian | 0.9% | 3.6% | 4.0% | 5.4% | 6.0% |

| Black | 3.0% | 4.1% | 3.5% | 3.3% | 3.0% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.7% |

| Other race | 0.4% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 2.5% |

| Multiracial | – | – | 5.5% | 7.3% | 12.2% |

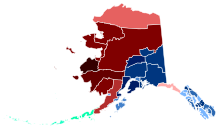

Map of the largest racial/ethnic group by borough. Red indicates Native American, blue indicates non-Hispanic white, and green indicates Asian. Darker shades indicate a higher proportion of the population.

The 2019 American Community Survey estimated 60.2% of the population was non-Hispanic white, 3.7% black or African American, 15.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, 6.5% Asian, 1.4% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 7.5% two or more races, and 7.3% Hispanic or Latin American of any race. At the survey estimates, 7.8% of the total population was foreign-born from 2015 to 2019.[69] In 2015, 61.3% was non-Hispanic white, 3.4% black or African American, 13.3% American Indian or Alaska Native, 6.2% Asian, 0.9% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 0.3% some other race, and 7.7% multiracial. Hispanics and Latin Americans were 7% of the state population in 2015.[70] From 2015 to 2019, the largest Hispanic and Latin American groups were Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans. The largest Asian groups living in the state were Filipinos, Korean Americans, and Japanese and Chinese Americans.[71]

The state was 66.7% white (64.1% non-Hispanic white), 14.8% American Indian and Alaska Native, 5.4% Asian, 3.3% black or African American, 1.0% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 1.6% from some other race, and 7.3% from two or more races in 2010. Hispanics or Latin Americans of any race made up 5.5% of the population in 2010.[72] As of 2011, 50.7% of Alaska’s population younger than one year of age belonged to minority groups (i.e., did not have two parents of non-Hispanic white ancestry).[73] In 1960, the United States Census Bureau reported Alaska’s population as 77.2% white, 3% black, and 18.8% American Indian and Alaska Native.[74]

Languages[edit]

According to the 2011 American Community Survey, 83.4% of people over the age of five spoke only English at home. About 3.5% spoke Spanish at home, 2.2% spoke another Indo-European language, about 4.3% spoke an Asian language (including Tagalog),[75] and about 5.3% spoke other languages at home.[76] In 2019, the American Community Survey determined 83.7% spoke only English, and 16.3% spoke another language other than English. The most spoken European language after English was Spanish, spoken by approximately 4.0% of the state population. Collectively, Asian and Pacific Islander languages were spoken by 5.6% of Alaskans.[77] Since 2010, a total of 5.2% of Alaskans speak one of the state’s 20 indigenous languages,[78] known locally as «native languages».

The Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks claims that at least 20 Alaskan native languages exist and there are also some languages with different dialects.[79] Most of Alaska’s native languages belong to either the Eskimo–Aleut or Na-Dene language families; however, some languages are thought to be isolates (e.g. Haida) or have not yet been classified (e.g. Tsimshianic).[79] As of 2014 nearly all of Alaska’s native languages were classified as either threatened, shifting, moribund, nearly extinct, or dormant languages.[80]

In October 2014, the governor of Alaska signed a bill declaring the state’s 20 indigenous languages to have official status.[81][82] This bill gave them symbolic recognition as official languages, though they have not been adopted for official use within the government. The 20 languages that were included in the bill are:

- Inupiaq

- Siberian Yupik

- Central Alaskan Yup’ik

- Alutiiq

- Unangax

- Dena’ina

- Deg Xinag

- Holikachuk

- Koyukon

- Upper Kuskokwim

- Gwich’in

- Tanana

- Upper Tanana

- Tanacross

- Hän

- Ahtna

- Eyak

- Tlingit

- Haida

- Tsimshian

Religion[edit]

ChangePoint in south Anchorage (left) and Anchorage Baptist Temple in east Anchorage (right) are Alaska’s largest churches in terms of attendance and membership.

According to statistics collected by the Association of Religion Data Archives from 2010, about 34% of Alaska residents were members of religious congregations. Of the religious population, 100,960 people identified as evangelical Protestants; 50,866 as Roman Catholic; and 32,550 as mainline Protestants.[83] Roughly 4% were Mormon, 0.5% Jewish, 0.5% Muslim, 1% Buddhist, 0.2% Baháʼí, and 0.5% Hindu.[84] The largest religious denominations in Alaska as of 2010 was the Roman Catholic Church with 50,866 adherents; non-denominational Evangelicals with 38,070 adherents; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 32,170 adherents; and the Southern Baptist Convention with 19,891 adherents.[85] Alaska has been identified, along with Washington and Oregon in the Pacific Northwest, as being the least religious states in the United States, in terms of church membership.[86][87]

The Pew Research Center in 2014 determined 62% of the adult population practiced Christianity. Protestantism was the largest Christian tradition, dominated by Evangelicalism. Mainline Protestants were the second largest Protestant Christian group, followed by predominantly African American churches. The Roman Catholic Church remained the largest single Christian tradition practiced in Alaska. Of the unaffiliated population, they made up the largest non-Christian religious affiliation. Atheists made up 5% of the population and the largest non-Christian religion was Buddhism. In 2020, the Public Religion Research Institute determined 57% of adults were Christian.[88]

In 1795, the first Russian Orthodox Church was established in Kodiak. Intermarriage with Alaskan Natives helped the Russian immigrants integrate into society. As a result, an increasing number of Russian Orthodox churches gradually became established within Alaska.[89] Alaska also has the largest Quaker population (by percentage) of any state.[90] In 2009, there were 6,000 Jews in Alaska (for whom observance of halakha may pose special problems).[91] Alaskan Hindus often share venues and celebrations with members of other Asian religious communities, including Sikhs and Jains.[92][93][94] In 2010, Alaskan Hindus established the Sri Ganesha Temple of Alaska, making it the first Hindu Temple in Alaska and the northernmost Hindu Temple in the world. There are an estimated 2,000–3,000 Hindus in Alaska. The vast majority of Hindus live in Anchorage or Fairbanks.

Estimates for the number of Muslims in Alaska range from 2,000 to 5,000.[95][96][97] The Islamic Community Center of Anchorage began efforts in the late 1990s to construct a mosque in Anchorage. They broke ground on a building in south Anchorage in 2010 and were nearing completion in late 2014. When completed, the mosque will be the first in the state and one of the northernmost mosques in the world.[98] There’s also a Baháʼí center.[99]

| Affiliation | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 62 | |

| Protestant | 37 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 22 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 12 | |

| Black church | 3 | |

| Catholic | 16 | |

| Mormon | 5 | |

| Jehovah’s Witnesses | 0.5 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | |

| Other Christian | 0.5 | |

| Unaffiliated | 31 | |

| Nothing in particular | 20 | |

| Agnostic | 6 | |

| Atheist | 5 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 6 | |

| Jewish | 0.5 | |

| Muslim | 0.5 | |

| Baháʼí | 0.2 | |

| Buddhist | 1 | |

| Hindu | 0.5 | |

| Other Non-Christian faiths | 4 | |

| Don’t know/refused answer | 1 | |

| Total | 100 |

Economy[edit]

As of October 2022, Alaska had a total employment of 316,900. The number of employer establishments was 21,077.[101]

The 2018 gross state product was $55 billion, 48th in the U.S. Its per capita personal income for 2018 was $73,000, ranking 7th in the nation. According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Alaska had the fifth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 6.75 percent.[102] The oil and gas industry dominates the Alaskan economy, with more than 80% of the state’s revenues derived from petroleum extraction. Alaska’s main export product (excluding oil and natural gas) is seafood, primarily salmon, cod, pollock and crab.

Agriculture represents a very small fraction of the Alaskan economy. Agricultural production is primarily for consumption within the state and includes nursery stock, dairy products, vegetables, and livestock. Manufacturing is limited, with most foodstuffs and general goods imported from elsewhere.

Employment is primarily in government and industries such as natural resource extraction, shipping, and transportation. Military bases are a significant component of the economy in the Fairbanks North Star, Anchorage and Kodiak Island boroughs, as well as Kodiak. Federal subsidies are also an important part of the economy, allowing the state to keep taxes low. Its industrial outputs are crude petroleum, natural gas, coal, gold, precious metals, zinc and other mining, seafood processing, timber and wood products. There is also a growing service and tourism sector. Tourists have contributed to the economy by supporting local lodging.

Energy[edit]

Alaskan oil production peaked in 1988 and has declined more than 75% since then.

Alaska has vast energy resources, although its oil reserves have been largely depleted. Major oil and gas reserves were found in the Alaska North Slope (ANS) and Cook Inlet basins, but according to the Energy Information Administration, by February 2014 Alaska had fallen to fourth place in the nation in crude oil production after Texas, North Dakota, and California.[103][104] Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope is still the second highest-yielding oil field in the United States, typically producing about 400,000 barrels per day (64,000 m3/d), although by early 2014 North Dakota’s Bakken Formation was producing over 900,000 barrels per day (140,000 m3/d).[105] Prudhoe Bay was the largest conventional oil field ever discovered in North America, but was much smaller than Canada’s enormous Athabasca oil sands field, which by 2014 was producing about 1,500,000 barrels per day (240,000 m3/d) of unconventional oil, and had hundreds of years of producible reserves at that rate.[106]

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline can transport and pump up to 2.1 million barrels (330,000 m3) of crude oil per day, more than any other crude oil pipeline in the United States. Additionally, substantial coal deposits are found in Alaska’s bituminous, sub-bituminous, and lignite coal basins. The United States Geological Survey estimates that there are 85.4 trillion cubic feet (2,420 km3) of undiscovered, technically recoverable gas from natural gas hydrates on the Alaskan North Slope.[107] Alaska also offers some of the highest hydroelectric power potential in the country from its numerous rivers. Large swaths of the Alaskan coastline offer wind and geothermal energy potential as well.[108]

Alaska’s economy depends heavily on increasingly expensive diesel fuel for heating, transportation, electric power and light. Although wind and hydroelectric power are abundant and underdeveloped, proposals for statewide energy systems (e.g. with special low-cost electric interties) were judged uneconomical (at the time of the report, 2001) due to low (less than 50¢/gal) fuel prices, long distances and low population.[109] The cost of a gallon of gas in urban Alaska today is usually thirty to sixty cents higher than the national average; prices in rural areas are generally significantly higher but vary widely depending on transportation costs, seasonal usage peaks, nearby petroleum development infrastructure and many other factors.

Permanent Fund[edit]

The Alaska Permanent Fund is a constitutionally authorized appropriation of oil revenues, established by voters in 1976 to manage a surplus in state petroleum revenues from oil, largely in anticipation of the then recently constructed Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. The fund was originally proposed by Governor Keith Miller on the eve of the 1969 Prudhoe Bay lease sale, out of fear that the legislature would spend the entire proceeds of the sale (which amounted to $900 million) at once. It was later championed by Governor Jay Hammond and Kenai state representative Hugh Malone. It has served as an attractive political prospect ever since, diverting revenues which would normally be deposited into the general fund.

The Alaska Constitution was written so as to discourage dedicating state funds for a particular purpose. The Permanent Fund has become the rare exception to this, mostly due to the political climate of distrust existing during the time of its creation. From its initial principal of $734,000, the fund has grown to $50 billion as a result of oil royalties and capital investment programs.[110] Most if not all the principal is invested conservatively outside Alaska. This has led to frequent calls by Alaskan politicians for the Fund to make investments within Alaska, though such a stance has never gained momentum.

Starting in 1982, dividends from the fund’s annual growth have been paid out each year to eligible Alaskans, ranging from an initial $1,000 in 1982 (equal to three years’ payout, as the distribution of payments was held up in a lawsuit over the distribution scheme) to $3,269 in 2008 (which included a one-time $1,200 «Resource Rebate»). Every year, the state legislature takes out 8% from the earnings, puts 3% back into the principal for inflation proofing, and the remaining 5% is distributed to all qualifying Alaskans. To qualify for the Permanent Fund Dividend, one must have lived in the state for a minimum of 12 months, maintain constant residency subject to allowable absences,[111] and not be subject to court judgments or criminal convictions which fall under various disqualifying classifications or may subject the payment amount to civil garnishment.

The Permanent Fund is often considered to be one of the leading examples of a basic income policy in the world.[112]

Cost of living[edit]

The cost of goods in Alaska has long been higher than in the contiguous 48 states. Federal government employees, particularly United States Postal Service (USPS) workers and active-duty military members, receive a Cost of Living Allowance usually set at 25% of base pay because, while the cost of living has gone down, it is still one of the highest in the country.[113]

Rural Alaska suffers from extremely high prices for food and consumer goods compared to the rest of the country, due to the relatively limited transportation infrastructure.[113]

Agriculture and fishing[edit]

Halibut, both as a sport fish and commercially, is important to the state’s economy.

Due to the northern climate and short growing season, relatively little farming occurs in Alaska. Most farms are in either the Matanuska Valley, about 40 miles (64 km) northeast of Anchorage, or on the Kenai Peninsula, about 60 miles (97 km) southwest of Anchorage. The short 100-day growing season limits the crops that can be grown, but the long sunny summer days make for productive growing seasons. The primary crops are potatoes, carrots, lettuce, and cabbage.

The Tanana Valley is another notable agricultural locus, especially the Delta Junction area, about 100 miles (160 km) southeast of Fairbanks, with a sizable concentration of farms growing agronomic crops; these farms mostly lie north and east of Fort Greely. This area was largely set aside and developed under a state program spearheaded by Hammond during his second term as governor. Delta-area crops consist predominantly of barley and hay. West of Fairbanks lies another concentration of small farms catering to restaurants, the hotel and tourist industry, and community-supported agriculture.

Alaskan agriculture has experienced a surge in growth of market gardeners, small farms and farmers’ markets in recent years, with the highest percentage increase (46%) in the nation in growth in farmers’ markets in 2011, compared to 17% nationwide.[114] The peony industry has also taken off, as the growing season allows farmers to harvest during a gap in supply elsewhere in the world, thereby filling a niche in the flower market.[115]

Alaska, with no counties, lacks county fairs. However, a small assortment of state and local fairs (with the Alaska State Fair in Palmer the largest), are held mostly in the late summer. The fairs are mostly located in communities with historic or current agricultural activity, and feature local farmers exhibiting produce in addition to more high-profile commercial activities such as carnival rides, concerts and food. «Alaska Grown» is used as an agricultural slogan.

Alaska has an abundance of seafood, with the primary fisheries in the Bering Sea and the North Pacific. Seafood is one of the few food items that is often cheaper within the state than outside it. Many Alaskans take advantage of salmon seasons to harvest portions of their household diet while fishing for subsistence, as well as sport. This includes fish taken by hook, net or wheel.[116]

Hunting for subsistence, primarily caribou, moose, and Dall sheep is still common in the state, particularly in remote Bush communities. An example of a traditional native food is Akutaq, the Eskimo ice cream, which can consist of reindeer fat, seal oil, dried fish meat and local berries.

Alaska’s reindeer herding is concentrated on Seward Peninsula, where wild caribou can be prevented from mingling and migrating with the domesticated reindeer.[117]

Most food in Alaska is transported into the state from «Outside» (the other 49 US states), and shipping costs make food in the cities relatively expensive. In rural areas, subsistence hunting and gathering is an essential activity because imported food is prohibitively expensive. Although most small towns and villages in Alaska lie along the coastline, the cost of importing food to remote villages can be high, because of the terrain and difficult road conditions, which change dramatically, due to varying climate and precipitation changes. The cost of transport can reach as high as 50¢ per pound ($1.10/kg) or more in some remote areas, during the most difficult times, if these locations can be reached at all during such inclement weather and terrain conditions. The cost of delivering a 1 US gallon (3.8 L) of milk is about $3.50 in many villages where per capita income can be $20,000 or less. Fuel cost per gallon is routinely twenty to thirty cents higher than the contiguous United States average, with only Hawaii having higher prices.[118][119]

Culture[edit]

Mask Display at Iñupiat Heritage Center in Utqiaġvik

Some of Alaska’s popular annual events are the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race from Anchorage to Nome, World Ice Art Championships in Fairbanks, the Blueberry Festival and Alaska Hummingbird Festival in Ketchikan, the Sitka Whale Fest, and the Stikine River Garnet Fest in Wrangell. The Stikine River attracts the largest springtime concentration of American bald eagles in the world.

The Alaska Native Heritage Center celebrates the rich heritage of Alaska’s 11 cultural groups. Their purpose is to encourage cross-cultural exchanges among all people and enhance self-esteem among Native people. The Alaska Native Arts Foundation promotes and markets Native art from all regions and cultures in the State, using the internet.[120]

Music[edit]

Influences on music in Alaska include the traditional music of Alaska Natives as well as folk music brought by later immigrants from Russia and Europe. Prominent musicians from Alaska include singer Jewel, traditional Aleut flautist Mary Youngblood, folk singer-songwriter Libby Roderick, Christian music singer-songwriter Lincoln Brewster, metal/post hardcore band 36 Crazyfists and the groups Pamyua and Portugal. The Man.

There are many established music festivals in Alaska, including the Alaska Folk Festival, the Fairbanks Summer Arts Festival the Anchorage Folk Festival, the Athabascan Old-Time Fiddling Festival, the Sitka Jazz Festival, and the Sitka Summer Music Festival. The most prominent orchestra in Alaska is the Anchorage Symphony Orchestra, though the Fairbanks Symphony Orchestra and Juneau Symphony are also notable. The Anchorage Opera is currently the state’s only professional opera company, though there are several volunteer and semi-professional organizations in the state as well.

The official state song of Alaska is «Alaska’s Flag», which was adopted in 1955; it celebrates the flag of Alaska.

Alaska on film and television[edit]

The 1983 Disney movie Never Cry Wolf was at least partially shot in Alaska. The 1991 film White Fang, based on Jack London’s 1906 novel and starring Ethan Hawke, was filmed in and around Haines. Steven Seagal’s 1994 On Deadly Ground, starring Michael Caine, was filmed in part at the Worthington Glacier near Valdez.[121]

Many reality television shows are filmed in Alaska. In 2011, the Anchorage Daily News found ten set in the state.[122]

Sports[edit]

Public health and public safety[edit]

The Alaska State Troopers are Alaska’s statewide police force. They have a long and storied history, but were not an official organization until 1941. Before the force was officially organized, law enforcement in Alaska was handled by various federal agencies. Larger towns usually have their own local police and some villages rely on «Public Safety Officers» who have police training but do not carry firearms. In much of the state, the troopers serve as the only police force available. In addition to enforcing traffic and criminal law, wildlife Troopers enforce hunting and fishing regulations. Due to the varied terrain and wide scope of the Troopers’ duties, they employ a wide variety of land, air, and water patrol vehicles.

Many rural communities in Alaska are considered «dry», having outlawed the importation of alcoholic beverages.[123] Suicide rates for rural residents are higher than urban.[124]

Domestic abuse and other violent crimes are also at high levels in the state; this is in part linked to alcohol abuse.[125] Alaska has the highest rate of sexual assault in the nation, especially in rural areas. The average age of sexually assaulted victims is 16 years old. In four out of five cases, the suspects were relatives, friends or acquaintances.[126]

Health insurance[edit]

As of 2022, CVS Health and Premera account for 47% and 46% of private health insurance, respectively.[127] Premera and Moda Health offer insurance on the federally-run Affordable Care Exchange.[128]

Education[edit]

The Alaska Department of Education and Early Development administers many school districts in Alaska. In addition, the state operates a boarding school, Mt. Edgecumbe High School in Sitka, and provides partial funding for other boarding schools, including Nenana Student Living Center in Nenana and The Galena Interior Learning Academy in Galena.[129]