In other contexts, the term world can also refer to the Earth, as seen in this 1972 photograph by the Apollo 17 crew.

In its most general sense, the term «world» refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is.[1] The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique while others talk of a «plurality of worlds». Some treat the world as one simple object while others analyze the world as a complex made up of many parts. In scientific cosmology the world or universe is commonly defined as «[t]he totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be». Theories of modality, on the other hand, talk of possible worlds as complete and consistent ways how things could have been. Phenomenology, starting from the horizon of co-given objects present in the periphery of every experience, defines the world as the biggest horizon or the «horizon of all horizons». In philosophy of mind, the world is commonly contrasted with the mind as that which is represented by the mind. Theology conceptualizes the world in relation to God, for example, as God’s creation, as identical to God or as the two being interdependent. In religions, there is often a tendency to downgrade the material or sensory world in favor of a spiritual world to be sought through religious practice. A comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it, as is commonly found in religions, is known as a worldview. Cosmogony is the field that studies the origin or creation of the world while eschatology refers to the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world.

In various contexts, the term «world» takes a more restricted meaning associated, for example, with the Earth and all life on it, with humanity as a whole or with an international or intercontinental scope. In this sense, world history refers to the history of humanity as a whole or world politics is the discipline of political science studying issues that transcend nations and continents. Other examples include terms such as «world religion», «world language», «world government», «world war», «world population», «world economy» or «world championship».

Etymology

The English word world comes from the Old English weorold. The Old English is a reflex of the Common Germanic *weraldiz, a compound of weraz ‘man’ and aldiz ‘age’, thus literally meaning roughly ‘age of man’;[2] this word also led to Old Frisian warld, Old Saxon werold, Old Dutch werolt, Old High German weralt, and Old Norse verǫld.[3]

The corresponding word in Latin is mundus, literally ‘clean, elegant’, itself a loan translation of Greek cosmos ‘orderly arrangement’. While the Germanic word thus reflects a mythological notion of a «domain of Man» (compare Midgard), presumably as opposed to the divine sphere on the one hand and the chthonic sphere of the underworld on the other, the Greco-Latin term expresses a notion of creation as an act of establishing order out of chaos.[4]

Conceptions

Different fields often work with quite different conceptions of the essential features associated with the term «world».[5][6] Some conceptions see the world as unique: there can be no more than one world. Others talk of a «plurality of worlds».[4] Some see worlds as complex things composed of many substances as their parts while others hold that worlds are simple in the sense that there is only one substance: the world as a whole.[7] Some characterize worlds in terms of objective spacetime while others define them relative to the horizon present in each experience. These different characterizations are not always exclusive: it may be possible to combine some without leading to a contradiction. Most of them agree that worlds are unified totalities.[5][6]

Monism and pluralism

Monism is a thesis about oneness: that only one thing exists in a certain sense. The denial of monism is pluralism, the thesis that, in a certain sense, more than one thing exists.[7] There are many forms of monism and pluralism, but in relation to the world as a whole, two are of special interest: existence monism/pluralism and priority monism/pluralism. Existence monism states that the world is the only concrete object there is.[7][8][9] This means that all the concrete «objects» we encounter in our daily lives, including apples, cars and ourselves, are not truly objects in a strict sense. Instead, they are just dependent aspects of the world-object.[7] Such a world-object is simple in the sense that it does not have any genuine parts. For this reason, it has also been referred to as «blobject» since it lacks an internal structure just like a blob.[10] Priority monism allows that there are other concrete objects besides the world.[7] But it holds that these objects do not have the most fundamental form of existence, that they somehow depend on the existence of the world.[9][11] The corresponding forms of pluralism, on the other hand, state that the world is complex in the sense that it is made up of concrete, independent objects.[7]

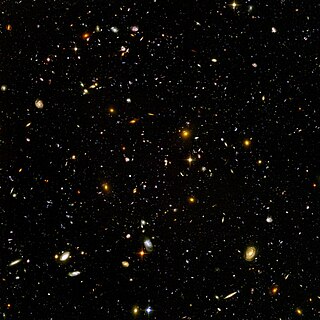

Scientific cosmology

Scientific cosmology can be defined as the science of the universe as a whole. In it, the terms «universe» and «cosmos» are usually used as synonyms for the term «world».[12] One common definition of the world/universe found in this field is as «[t]he totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be».[13][5][6] Some definitions emphasize that there are two other aspects to the universe besides spacetime: forms of energy or matter, like stars and particles, and laws of nature.[14] Different world-conceptions in this field differ both concerning their notion of spacetime and of the contents of spacetime. The theory of relativity plays a central role in modern cosmology and its conception of space and time. An important difference from its predecessors is that it conceives space and time not as distinct dimensions but as a single four-dimensional manifold called spacetime.[15] This can be seen in special relativity in relation to the Minkowski metric, which includes both spatial and temporal components in its definition of distance.[16] General relativity goes one step further by integrating the concept of mass into the concept of spacetime as its curvature.[16] Quantum cosmology, on the other hand, uses a classical notion of spacetime and conceives the whole world as one big wave function expressing the probability of finding particles in a given location.[17]

Theories of modality

The world-concept plays an important role in many modern theories of modality, usually in the form of possible worlds.[18] A possible world is a complete and consistent way how things could have been.[19] The actual world is a possible world since the way things are is a way things could have been. But there are many other ways things could have been besides how they actually are. For example, Hillary Clinton did not win the 2016 US election, but she could have won them. So there is a possible world in which she did. There is a vast number of possible worlds, one corresponding to each such difference, no matter how small or big, as long as no outright contradictions are introduced this way.[19]

Possible worlds are often conceived as abstract objects, for example, in terms of non-obtaining states of affairs or as maximally consistent sets of propositions.[20][21] On such a view, they can even be seen as belonging to the actual world.[22] Another way to conceive possible worlds, made famous by David Lewis, is as concrete entities.[4] On this conception, there is no important difference between the actual world and possible worlds: both are conceived as concrete, inclusive and spatiotemporally connected.[19] The only difference is that the actual world is the world we live in, while other possible worlds are not inhabited by us but by our counterparts.[23] Everything within a world is spatiotemporally connected to everything else but the different worlds do not share a common spacetime: They are spatiotemporally isolated from each other.[19] This is what makes them separate worlds.[23]

It has been suggested that, besides possible worlds, there are also impossible worlds. Possible worlds are ways things could have been, so impossible worlds are ways things could not have been.[24][25] Such worlds involve a contradiction, like a world in which Hillary Clinton both won and lost the 2016 US election. Both possible and impossible worlds have in common the idea that they are totalities of their constituents.[24][26]

Phenomenology

Within phenomenology, worlds are defined in terms of horizons of experiences.[5][6] When we perceive an object, like a house, we do not just experience this object at the center of our attention but also various other objects surrounding it, given in the periphery.[27] The term «horizon» refers to these co-given objects, which are usually experienced only in a vague, indeterminate manner.[28][29] The perception of a house involves various horizons, corresponding to the neighborhood, the city, the country, the Earth, etc. In this context, the world is the biggest horizon or the «horizon of all horizons».[27][5][6] It is common among phenomenologists to understand the world not just as a spatiotemporal collection of objects but as additionally incorporating various other relations between these objects. These relations include, for example, indication-relations that help us anticipate one object given the appearances of another object and means-end-relations or functional involvements relevant for practical concerns.[27]

Philosophy of mind

In philosophy of mind, the term «world» is commonly used in contrast to the term «mind» as that which is represented by the mind. This is sometimes expressed by stating that there is a gap between mind and world and that this gap needs to be overcome for representation to be successful.[30][31][32] One of the central problems in philosophy of mind is to explain how the mind is able to bridge this gap and to enter into genuine mind-world-relations, for example, in the form of perception, knowledge or action.[33][34] This is necessary for the world to be able to rationally constrain the activity of the mind.[30][35] According to a realist position, the world is something distinct and independent from the mind.[36] Idealists, on the other hand, conceive of the world as partially or fully determined by the mind.[36][37] Immanuel Kant’s transcendental idealism, for example, posits that the spatiotemporal structure of the world is imposed by the mind on reality but lacks independent existence otherwise.[38] A more radical idealist conception of the world can be found in Berkeley’s subjective idealism, which holds that the world as a whole, including all everyday objects like tables, cats, trees and ourselves, «consists of nothing but minds and ideas».[39]

Theology

Different theological positions hold different conceptions of the world based on its relation to God. Classical theism states that God is wholly distinct from the world. But the world depends for its existence on God, both because God created the world and because He maintains or conserves it.[40][41][42] This is sometimes understood in analogy to how humans create and conserve ideas in their imagination, with the difference being that the divine mind is vastly more powerful.[40] On such a view, God has absolute, ultimate reality in contrast to the lower ontological status ascribed to the world.[42] God’s involvement in the world is often understood along the lines of a personal, benevolent God who looks after and guides His creation.[41] Deists agree with theists that God created the world but deny any subsequent, personal involvement in it.[43] Pantheists, on the other hand, reject the separation between God and world. Instead, they claim that the two are identical. This means that there is nothing to the world that does not belong to God and that there is nothing to God beyond what is found in the world.[42][44] Panentheism constitutes a middle ground between theism and pantheism. Against theism, It holds that God and the world are interrelated and depend on each other. Against pantheism, it holds that there is no outright identity between the two.[42][45] Atheists, on the other hand, deny the existence of God and thereby of conceptions of the world based on its relation to God.

History of philosophy

In philosophy, the term world has several possible meanings. In some contexts, it refers to everything that makes up reality or the physical universe. In others, it can mean have a specific ontological sense (see world disclosure). While clarifying the concept of world has arguably always been among the basic tasks of Western philosophy, this theme appears to have been raised explicitly only at the start of the twentieth century[46] and has been the subject of continuous debate. The question of what the world is has by no means been settled.

Parmenides

The traditional interpretation of Parmenides’ work is that he argued that the everyday perception of reality of the physical world (as described in doxa) is mistaken, and that the reality of the world is ‘One Being’ (as described in aletheia): an unchanging, ungenerated, indestructible whole.

Plato

Plato is well known for his theory of forms, which posits the existence of two different worlds: the sensible world and the intelligible world. The sensible world is the world we live in, filled with changing physical things we can see, touch and interact with. The intelligible world, on the other hand, is the world of invisible, eternal, changeless forms like goodness, beauty, unity and sameness.[47][48][49] Plato ascribes a lower ontological status to the sensible world, which only imitates the world of forms. This is due to the fact that physical things exist only to the extent that they participate in the forms that characterize them, while the forms themselves have an independent manner of existence.[47][48][49] In this sense, the sensible world is a mere replication of the perfect exemplars found in the world of forms: it never lives up to the original. In the allegory of the cave, Plato compares the physical things we are familiar with to mere shadows of the real things. But not knowing the difference, the prisoners in the cave mistake the shadows for the real things.[50]

Hegel

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s philosophy of history, the expression Weltgeschichte ist Weltgericht (World History is a tribunal that judges the World) is used to assert the view that History is what judges men, their actions and their opinions. Science is born from the desire to transform the World in relation to Man; its final end is technical application.

Schopenhauer

The World as Will and Representation is the central work of Arthur Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer saw the human will as our one window to the world behind the representation; the Kantian thing-in-itself. He believed, therefore, that we could gain knowledge about the thing-in-itself, something Kant said was impossible, since the rest of the relationship between representation and thing-in-itself could be understood by analogy to the relationship between human will and human body.

Wittgenstein

Two definitions that were both put forward in the 1920s, however, suggest the range of available opinion. «The world is everything that is the case,» wrote Ludwig Wittgenstein in his influential Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, first published in 1921.[51] This definition would serve as the basis of logical positivism, with its assumption that there is exactly one world, consisting of the totality of facts, regardless of the interpretations that individual people may make of them.

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger, meanwhile, argued that «the surrounding world is different for each of us, and notwithstanding that we move about in a common world».[52] The world, for Heidegger, was that into which we are always already «thrown» and with which we, as beings-in-the-world, must come to terms. His conception of «world disclosure» was most notably elaborated in his 1927 work Being and Time.

Eugen Fink

«World» is one of the key terms in Eugen Fink’s philosophy.[53] He thinks that there is a misguided tendency in western philosophy to understand the world as one enormously big thing containing all the small everyday things we are familiar with.[54] He sees this view as a form of forgetfulness of the world and tries to oppose it by what he calls the «cosmological difference»: the difference between the world and the inner-worldly things it contains.[54] On his view, the world is the totality of the inner-worldly things that transcends them.[55] It is itself groundless but it provides a ground for things. It therefore cannot be identified with a mere container. Instead, the world gives appearance to inner-worldly things, it provides them with a place, a beginning and an end.[54] One difficulty in investigating the world is that we never encounter it since it is not just one more thing that appears to us. This is why Fink uses the notion of play or playing to elucidate the nature of the world.[54][55] He sees play as a symbol of the world that is both part of it and that represents it.[56] Play usually comes with a form of imaginary play-world involving various things relevant to the play. But just like the play is more than the imaginary realities appearing in it so the world is more than the actual things appearing in it.[54][56]

Goodman

The concept of worlds plays a central role in Nelson Goodman’s late philosophy.[57] He argues that we need to posit different worlds in order to account for the fact that there are different incompatible truths found in reality.[58] Two truths are incompatible if they ascribe incompatible properties to the same thing.[57] This happens, for example, when we assert both that the earth moves and that the earth is at rest. These incompatible truths correspond to two different ways of describing the world: heliocentrism and geocentrism.[58] Goodman terms such descriptions «world versions». He holds a correspondence theory of truth: a world version is true if it corresponds to a world. Incompatible true world versions correspond to different worlds.[58] It is common for theories of modality to posit the existence of a plurality of possible worlds. But Goodman’s theory is different since it posits a plurality not of possible but of actual worlds.[57][5] Such a position is in danger of involving a contradiction: there cannot be a plurality of actual worlds if worlds are defined as maximally inclusive wholes.[57][5] This danger may be avoided by interpreting Goodman’s world-concept not as maximally inclusive wholes in the absolute sense but in relation to its corresponding world-version: a world contains all and only the entities that its world-version describes.[57][5]

Religion

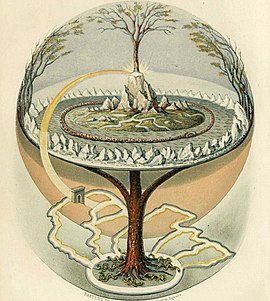

Mythological cosmologies often depict the world as centered on an axis mundi and delimited by a boundary such as a world ocean, a world serpent or similar. In some religions, worldliness (also called carnality)[59][60] is that which relates to this world as opposed to other worlds or realms.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the world means society, as distinct from the monastery. It refers to the material world, and to worldly gain such as wealth, reputation, jobs, and war. The spiritual world would be the path to enlightenment, and changes would be sought in what we could call the psychological realm.

Christianity

In Christianity, the term often connotes the concept of the fallen and corrupt world order of human society, in contrast to the World to Come. The world is frequently cited alongside the flesh and the Devil as a source of temptation that Christians should flee. Monks speak of striving to be «in this world, but not of this world» — as Jesus said — and the term «worldhood» has been distinguished from «monkhood», the former being the status of merchants, princes, and others who deal with «worldly» things.

This view is clearly expressed by king Alfred the Great of England (d. 899) in his famous Preface to the Cura Pastoralis:

«Therefore I command you to do as I believe you are willing to do, that you free yourself from worldly affairs (Old English: woruldðinga) as often as you can, so that wherever you can establish that wisdom that God gave you, you establish it. Consider what punishments befell us in this world when we neither loved wisdom at all ourselves, nor transmitted it to other men; we had the name alone that we were Christians, and very few had the practices».

Although Hebrew and Greek words meaning «world» are used in Scripture with the normal variety of senses, many examples of its use in this particular sense can be found in the teachings of Jesus according to the Gospel of John, e.g. 7:7, 8:23, 12:25, 14:17, 15:18-19, 17:6-25, 18:36. In contrast, a relatively newer concept is Catholic imagination.

Contemptus mundi is the name given to the belief that the world, in all its vanity, is nothing more than a futile attempt to hide from God by stifling our desire for the good and the holy.[61] This view has been criticised as a «pastoral of fear» by modern historian Jean Delumeau.[62]

During the Second Vatican Council, there was a novel attempt to develop a positive theological view of the World, which is illustrated by the pastoral optimism of the constitutions Gaudium et spes, Lumen gentium, Unitatis redintegratio and Dignitatis humanae.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christian monasticism or asceticism, the world of mankind is driven by passions. Therefore, the passions of the World are simply called «the world». Each of these passions are a link to the world of mankind or order of human society. Each of these passions must be overcome in order for a person to receive salvation (Theosis). The process of Theosis is a personal relationship with God. This understanding is taught within the works of ascetics like Evagrius Ponticus, and the most seminal ascetic works read most widely by Eastern Christians, the Philokalia and The Ladder of Divine Ascent (the works of Evagrius and John Climacus are also contained within the Philokalia). At the highest level of world transcendence is hesychasm which culminates into the Vision of God.

Orbis Catholicus

Orbis Catholicus is a Latin phrase meaning Catholic world, per the expression Urbi et Orbi, and refers to that area of Christendom under papal supremacy.[63] It is somewhat similar to the phrases secular world, Jewish world and Islamic world.

Islam

In Islam, the term «dunya» is used for the world. Its meaning is derived from the root word «dana», a term for «near».[64] It is mainly associated with the temporal, sensory world and earthly concerns, i.e. with this world in contrast to the spiritual world.[65] Some religious teachings warn of our tendency to seek happiness in this world and advise a more ascetic lifestyle concerned with the afterlife.[66] But other strands in Islam recommend a balanced approach.[65]

Mandaeism

In Mandaean cosmology, the world or earthly realm is known as Tibil. It is separated from the World of Light (alma d-nhūra) above and the World of Darkness (alma d-hšuka) below by ayar (aether).[67][68]

Hinduism

Hinduism constitutes a wide family of religious-philosophical views.[69] These views present different perspectives on the nature and role of the world. Samkhya philosophy, for example, is a metaphysical dualism that understands reality as comprising two parts: purusha and prakriti.[70] The term «purusha» stands for the individual conscious self that each of us possesses. Prakriti, on the other hand, is the one world inhabited by all these selves.[71] Samkhya understands this world as a world of matter governed by the law of cause and effect.[70] The term «matter» is understood in a very wide sense in this tradition including both physical and mental aspects.[72] This is reflected in the doctrine of tattvas, according to which prakriti is made up of 23 different principles or elements of reality.[72] These principles include both physical elements, like water or earth, and mental aspects, like intelligence or sense-impressions.[71] The relation between purusha and prakriti is usually conceived as one of mere observation: purusha is the conscious self aware of the world of prakriti but does not causally interact with it.[70]

A very different conception of the world is present in Advaita Vedanta, the monist school among the Vedanta schools.[69] Unlike the realist position defended in Samkhya philosophy, Advaita Vedanta sees the world of multiplicity as an illusion, referred to as Maya.[69] This illusion also includes our impression of existing as separate experiencing selfs called Jivas.[73] Instead, Advaita Vedanta teaches that on the most fundamental level of reality, referred to as Brahman, there exists no plurality or difference.[73] All there is is one all-encompassing self: Atman.[69] Ignorance is seen as the source of this illusion, which results in bondage to the world of mere appearances. But liberation is possible in the course of overcoming this illusion by acquiring the knowledge of Brahman, according to Advaita Vedanta.[73]

Related terms and problems

Worldviews

A worldview is a comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it.[74] As a representation, it is a subjective perspective of the world and thereby different from the world it represents.[75] All higher animals need to represent their environment in some way in order to navigate it. But it has been argued that only humans possess a representation encompassing enough to merit the term «worldview».[75] Philosophers of worldviews commonly hold that the understanding of any object depends on a worldview constituting the background on which this understanding can take place. This may affect not just our intellectual understanding of the object in question but the experience of it in general.[74] It is therefore impossible to assess one’s worldview from a neutral perspective since this assessment already presupposes the worldview as its background. Some hold that each worldview is based on a single hypothesis that promises to solve all the problems of our existence we may encounter.[76] On this interpretation, the term is closely associated to the worldviews given by different religions.[76] Worldviews offer orientation not just in theoretical matters but also in practical matters. For this reason, they usually include answers to the question of the meaning of life and other evaluative components about what matters and how we should act.[77][78] A worldview can be unique to one individual but worldviews are usually shared by many people within a certain culture or religion.

Paradox of many worlds

The idea that there exist many different worlds is found in various fields. For example, Theories of modality talk about a plurality of possible worlds and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics carries this reference even in its name. Talk of different worlds is also common in everyday language, for example, with reference to the world of music, the world of business, the world of football, the world of experience or the Asian world. But at the same time, worlds are usually defined as all-inclusive totalities.[5][6][15][14] This seems to contradict the very idea of a plurality of worlds since if a world is total and all-inclusive then it cannot have anything outside itself. Understood this way, a world can neither have other worlds besides itself or be part of something bigger.[5][57] One way to resolve this paradox while holding onto the notion of a plurality of worlds is to restrict the sense in which worlds are totalities. On this view, worlds are not totalities in an absolute sense.[5] This might be even understood in the sense that, strictly speaking, there are no worlds at all.[57] Another approach understands worlds in a schematic sense: as context-dependent expressions that stand for the current domain of discourse. So in the expression «Around the World in Eighty Days», the term «world» refers to the earth while in the colonial[79] expression «the New World» it refers to the landmass of North and South America.[15]

Cosmogony

Cosmogony is the field that studies the origin or creation of the world. This includes both scientific cosmogony and creation myths found in various religions.[80][81] The dominant theory in scientific cosmogony is the Big Bang theory, according to which both space, time and matter have their origin in one initial singularity occurring about 13.8 billion years ago. This singularity was followed by an expansion that allowed the universe to sufficiently cool down for the formation of subatomic particles and later atoms. These initial elements formed giant clouds, which would then coalesce into stars and galaxies.[16] Non-scientific creation myths are found in many cultures and are often enacted in rituals expressing their symbolic meaning.[80] They can be categorized concerning their contents. Types often found include creation from nothing, from chaos or from a cosmic egg.[80]

Eschatology

Eschatology refers to the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world. It is traditionally associated with religion, specifically with the Abrahamic religions.[82][83]

In this form, it may include teachings both of the end of each individual human life and of the end of the world as a whole. But it has been applied to other fields as well, for example, in the form of physical Eschatology, which includes scientifically based speculations about the far future of the universe.[84] According to some models, there will be a Big Crunch in which the whole universe collapses back into a singularity, possibly resulting in a second Big Bang afterward. But current astronomical evidence seems to suggest that our universe will continue to expand indefinitely.[84]

World history

World history studies the world from a historical perspective. Unlike other approaches to history, it employs a global viewpoint. It deals less with individual nations and civilizations, which it usually approaches at a high level of abstraction.[85] Instead, it concentrates on wider regions and zones of interaction, often interested in how people, goods and ideas move from one region to another.[86] It includes comparisons of different societies and civilizations as well as considering wide-ranging developments with a long-term global impact like the process of industrialization.[85] Contemporary world history is dominated by three main research paradigms determining the periodization into different epochs.[87] One is based on productive relations between humans and nature. The two most important changes in history in this respect were the introduction of agriculture and husbandry concerning the production of food, which started around 10,000 to 8,000 BCE and is sometimes termed the Neolithic revolution, and the industrial revolution, which started around 1760 CE and involved the transition from manual to industrial manufacturing.[88][89][87] Another paradigm, focusing on culture and religion instead, is based on Karl Jaspers’ theories about the axial age, a time in which various new forms of religious and philosophical thoughts appeared in several separate parts of the world around the time between 800 and 200 BCE.[87] A third periodization is based on the relations between civilizations and societies. According to this paradigm, history can be divided into three periods in relation to the dominant region in the world: Middle Eastern dominance before 500 BCE, Eurasian cultural balance until 1500 CE and Western dominance since 1500 CE.[87] Big history employs an even wider framework than world history by putting human history into the context of the history of the universe as a whole. It starts with the Big Bang and traces the formation of galaxies, the solar system, the earth, its geological eras, the evolution of life and humans until the present day.[87]

World politics

World politics, also referred to as global politics or international relations, is the discipline of political science studying issues of interest to the world that transcend nations and continents.[90][91] It aims to explain complex patterns found in the social world that are often related to the pursuit of power, order and justice, usually in the context of globalization. It focuses not just on the relations between nation-states but also considers other transnational actors, like multinational corporations, terrorist groups, or non-governmental organizations.[92] For example, it tries to explain events like 9/11, the 2003 war in Iraq or the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

Various theories have been proposed in order to deal with the complexity involved in formulating such explanations.[92] These theories are sometimes divided into realism, liberalism and constructivism.[93] Realists see nation-states as the main actors in world politics. They constitute an anarchical international system without any overarching power to control their behavior. They are seen as sovereign agents that, determined by human nature, act according to their national self-interest. Military force may play an important role in the ensuing struggle for power between states, but diplomacy and cooperation are also key mechanisms for nations to achieve their goals.[92][94][95] Liberalists acknowledge the importance of states but they also emphasize the role of transnational actors, like the United Nations or the World Trade Organization. They see humans as perfectible and stress the role of democracy in this process. The emergent order in world politics, on this perspective, is more complex than a mere balance of power since more different agents and interests are involved in its production.[92][96] Constructivism ascribes more importance to the agency of individual humans than realism and liberalism. It understands the social world as a construction of the people living in it. This leads to an emphasis on the possibility of change. If the international system is an anarchy of nation-states, as the realists hold, then this is only so because we made it this way and may well change since this is not prefigured by human nature, according to the constructivists.[92][97]

See also

- Earth

- Globe

- Holon

- List of sovereign states

- Universe

- World map

References

- ^ «World». wordnetweb.princeton.edu. Princeton University. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ «Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby». www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.

- ^ Orel, Vladimir (2003) A Handbook of Germanic Etymology Leiden: Brill. p. 462 ISBN 90-04-12875-1

- ^ a b c Lewis, David (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sandkühler, Hans Jörg (2010). «Welt». Enzyklopädie Philosophie. Meiner.

- ^ a b c d e f Mittelstraß, Jürgen (2005). «Welt». Enzyklopädie Philosophie und Wissenschaftstheorie. Metzler. ISBN 9783476021083.

- ^ a b c d e f Schaffer, Jonathan (2018). «Monism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Schaffer, Jonathan (2007). «From Nihilism to Monism». Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 85 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1080/00048400701343150. S2CID 7788506.

- ^ a b Sider, Theodore (2007). «Against Monism». Analysis. 67 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8284.2007.00641.x.

- ^ Horgan, Terry; Potr, Matja (2000). «Blobjectivism and Indirect Correspondence». Facta Philosophica. 2 (2): 249–270. doi:10.5840/factaphil20002214. S2CID 15340589.

- ^ Steinberg, Alex (2015). «Priority Monism and Part/Whole Dependence». Philosophical Studies. 172 (8): 2025–2031. doi:10.1007/s11098-014-0395-8. S2CID 170436138.

- ^ Bolonkin, Alexander (26 December 2011). Universe, Human Immortality and Future Human Evaluation. Elsevier. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-12-415801-6.

- ^ Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). «Glossary». Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ^ a b Schreuder, Duco A. (3 December 2014). Vision and Visual Perception. Archway Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4808-1294-9.

- ^ a b c Fraassen, Bas C. van (1995). «‘World’ is Not a Count Noun». Noûs. 29 (2): 139–157. doi:10.2307/2215656. JSTOR 2215656.

- ^ a b c Zeilik, Michael; Gregory, Stephen A. (1998). «25. Cosmology: The Big Bang and Beyond». Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ^ Dongshan, He; Dongfeng, Gao; Qing-yu, Cai (2014). «Spontaneous creation of the universe from nothing». Physical Review D. 89 (8): 083510. arXiv:1404.1207. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89h3510H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.083510. S2CID 118371273.

- ^ Parent, Ted. «Modal Metaphysics». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Menzel, Christopher (2017). «Possible Worlds». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Jacquette, Dale (1 April 2006). «Propositions, Sets, and Worlds». Studia Logica. 82 (3): 337–343. doi:10.1007/s11225-006-8101-2. ISSN 1572-8730. S2CID 38345726.

- ^ Menzel, Christopher. «Possible Worlds > Problems with Abstractionism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Menzel, Christopher. «Actualism > An Account of Abstract Possible Worlds». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bricker, Phillip (2006). «David Lewis: On the Plurality of Worlds». Central Works of Philosophy, Vol. 5: The Twentieth Century: Quine and After. Acumen Publishing: 246–267. doi:10.1017/UPO9781844653621.014. ISBN 9781844653621.

- ^ a b Berto, Francesco; Jago, Mark (2018). «Impossible Worlds». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Zalta, Edward N. (1997). «A Classically-Based Theory of Impossible Worlds». Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic. 38 (4): 640–660. doi:10.1305/ndjfl/1039540774.

- ^ Ryan, Marie-Laure (2013). «Impossible Worlds and Aesthetic Illusion». Immersion and Distance. Brill Rodopi. ISBN 978-94-012-0924-3.

- ^ a b c Embree, Lester (1997). «World». Encyclopedia of Phenomenology. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ^ Smith, David Woodruff (2018). «Phenomenology». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Smith, Joel. «Phenomenology». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b Price, Huw; McDowell, John (1994). «Mind and World». Philosophical Books. 38 (3): 169–181. doi:10.1111/1468-0149.00066.

- ^ Avramides, Anita. «Philosophy of Mind: Overview». www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Witmer, D. Gene. «Philosophy Of Mind». www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ «Philosophy of mind». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Sosa, Ernest (2015). «Mind-World Relations». Episteme. 12 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1017/epi.2015.8. ISSN 1742-3600. S2CID 147785165.

- ^ Brandom, Robert B. (1996). «Perception and Rational Constraint: McDowell’s Mind and World». Philosophical Issues. 7: 241–259. doi:10.2307/1522910. JSTOR 1522910.

- ^ a b Miller, Alexander (2019). «Realism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Guyer, Paul; Horstmann, Rolf-Peter (2021). «Idealism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Stang, Nicholas F. (2021). «Kant’s Transcendental Idealism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Flage, Daniel E. «Berkeley, George». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Classical theism». www.rep.routledge.com. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b «Theism». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Culp, John (2020). «Panentheism». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ «Deism». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Pantheism». www.rep.routledge.com.

- ^ Leftow, Brian. «God, concepts of: Panentheism». www.rep.routledge.com.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (1982). Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-253-17686-7.

- ^ a b Kraut, Richard (2017). «Plato». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Brickhouse, Thomas; Smith, Nicholas D. «Plato: 6b. The Theory of Forms». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Nehamas, Alexander (1975). «Plato on the Imperfection of the Sensible World». American Philosophical Quarterly. 12 (2): 105–117. ISSN 0003-0481. JSTOR 20009565.

- ^ Partenie, Catalin (2018). «Plato’s Myths». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Biletzki, Anat; Matar, Anat (3 March 2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Ludwig Wittgenstein» (Fall 2016 ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Heidegger (1982), p. 164

- ^ Elden, Stuart (2008). «Eugen Fink and the Question of the World». Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. 5: 48–59.

- ^ a b c d e Homan, Catherine (2013). «The Play of Ethics in Eugen Fink». Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 27 (3): 287–296. doi:10.5325/jspecphil.27.3.0287. S2CID 142401048.

- ^ a b Halák, Jan (2016). «Beyond Things: The Ontological Importance of Play According to Eugen Fink». Journal of the Philosophy of Sport. 43 (2): 199–214. doi:10.1080/00948705.2015.1079133. S2CID 146382154.

- ^ a b Halák, Jan (2015). «Towards the World: Eugen Fink on the Cosmological Value of Play». Sport, Ethics and Philosophy. 9 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1080/17511321.2015.1130740. S2CID 146764077.

- ^ a b c d e f g Declos, Alexandre (2019). «Goodman’s Many Worlds». Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy. 7 (6): 1–25. doi:10.15173/jhap.v7i6.3827.

- ^ a b c Cohnitz, Daniel; Rossberg, Marcus (2020). «Nelson Goodman: 6. Irrealism and Worldmaking». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Hemer, C. J. «Worldly» Edited by Geoffrey W. Bromiley The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. 2019 – via OED Online.

- ^ «Contemptus Mundi : Contempt of the world | Catholic Christian Healing Psychology». www.chastitysf.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ^ «Parish Missions». Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ Marty, Martin (2008). The Christian World: A Global History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-58836-684-9.

- ^ Attas, Islam and Secularism[page needed]

- ^ a b «dunyâ». Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam: Edited on Behalf of the Royal Netherlands Academy. Fourth Impression. Brill. 2001. ISBN 978-0-391-04116-5.

- ^ Oktar, Adnan (1999). «Man’s True Abode: Hereafter». The Truth of the Life of This World.

- ^ Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443.

- ^ a b c d Ranganathan, Shyam. «Hindu Philosophy». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Ruzsa, Ferenc. «Sankhya». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b «Indian philosophy — The Samkhya-karikas». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b Parrot, Rodney J. (1986). «THE PROBLEM OF THE SĀṂKHYA TATTVAS AS BOTH COSMIC AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA». Journal of Indian Philosophy. 14 (1): 55–77. ISSN 0022-1791. JSTOR 23444164.

- ^ a b c Menon, Sangeetha. «Vedanta, Advaita». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b McIvor, David W. «Weltanschauung». International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.

- ^ a b Bunge, Mario (2010). «1. Philosophy as Worldview». Matter and Mind: A Philosophical Inquiry. Springer Verlag.

- ^ a b De Mijolla-Mellor, Sophie. «Weltanschauung». International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis.

- ^ MARSHALL, GORDON. «Weltanschauung». A Dictionary of Sociology.

- ^ Weber, Erik (1998). «Introduction». Foundations of Science. 3 (2): 231–234. doi:10.1023/A:1009669806878.

- ^ «The Old World-New World Debate and the Columbian Exchange». Wondrium Daily. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Long, Charles. «Cosmogony». Encyclopedia of Religion.

- ^ «Cosmogony». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ «Eschatology». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Owen, H. «Eschatology». Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Halvorson, Hans; Kragh, Helge (2019). «Cosmology and Theology: 7. Physical eschatology». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bentley, Jerry H. (31 March 2011). Bentley, Jerry H (ed.). «The Task of World History». The Oxford Handbook of World History. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.001.0001. ISBN 9780199235810. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ «What Is World History?». World History Association. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cajani, Luigi (2011). «Periodization». In Bentley, Jerry H (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of World History. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.013.0004.

- ^ Graeme Barker (2009). The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why did Foragers become Farmers?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955995-4.

- ^ «Industrial Revolution». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Baylis, John; Smith, Steve; Owens, Patricia, eds. (2020). «Glossary». The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (Eighth Edition, New to this ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882554-8.

- ^ Blanton, Shannon L.; Kegley, Charles W. (2021). «Glossary». World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 17th Edition — 9780357141809 — Cengage. Cengage.

- ^ a b c d e Baylis, John; Smith, Steve; Owens, Patricia, eds. (2020). «Introduction». The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (Eighth Edition, New to this ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882554-8.

- ^ Blanton, Shannon L.; Kegley, Charles W. (2021). «2. Interpreting World Politics through the Lens of theory». World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 17th Edition — 9780357141809 — Cengage. Cengage.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian (2018). «Political Realism in International Relations». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Moseley, Alexander. «Political Realism». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Cristol, Jonathan. «Liberalism». Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Cristol, Jonathan. «Constructivism». Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to World.

- World. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

Media related to World at Wikimedia Commons

English word world comes from Proto-Germanic *weraz (Husband. Man.), Proto-Germanic *aldiz (Age, generation. Lifetime.)

Detailed word origin of world

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| *weraz | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Husband. Man. |

| *aldiz | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Age, generation. Lifetime. |

| *weraldiz | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Lifetime, worldly existence. Mankind. World. |

| worold | Old English (ang) | World, the earth, a state of existence. |

| weoreld | Middle English (enm) | |

| world | English (eng) | To consider or cause to be considered from a global perspective; to consider as a global whole, rather than making or focussing on national or other distinctions; compare globalise.. To make real; to make worldly. (archaic) Age, era. (by extension) Any other astronomical body which many be inhabitable, such as a natural satellite.. (countable) A planet, especially one which is inhabited or […] |

Words with the same origin as world

- Adyghe: дунае (dunaaje)

- Afrikaans: wêreld (af)

- Aghwan: 𐔰𐔺𐔵 (ayz)

- Albanian: botë (sq) f

- Amharic: ዓለም (am) (ʿaläm)

- Arabic: عَالَم (ar) m (ʕālam)

- Aragonese: mundo m

- Archi: дунил (dunil)

- Armenian: աշխարհ (hy) (ašxarh)

- Aromanian: lume, lumi

- Assamese: বিশ্ব (bisso), জগত (zogot), পৃথিৱী (prithiwi), দুনীয়া (dunia)

- Asturian: mundu (ast) m

- Avar: дунял (dunjal)

- Azerbaijani: dünya (az), aləm (az), cahan (poetic)

- Bashkir: донъя (donʺya)

- Basque: mundu

- Bavarian: Wöd

- Belarusian: свет m (svjet), сьвет m (sʹvjet) (Taraškievica)

- Bengali: দুনিয়া (bn) (duniẏoa), জাহান (bn) (jahan), কায়েনাত (kaẏenat), বিশ্ব (bn) (biśśo), আলম (bn) (alom), জগত (jogot)

- Bikol Central: kinaban (bcl)

- Breton: bed (br) m

- Bulgarian: свят (bg) m (svjat)

- Burmese: လောက (my) (lau:ka.), ကမ္ဘာ (my) (kambha)

- Catalan: món (ca) m

- Cebuano: kalibotan

- Central Atlas Tamazight: ⴰⵎⴰⴹⴰⵍ (amaḍal)

- Cherokee: ᎡᎶᎯ (chr) (elohi)

- Chickasaw: yaakni’

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 世界 (yue) (sai3 gaai3)

- Dungan: шыҗе (šɨži͡ə), дун-я (dun-i͡a)

- Hakka: 世界 (sṳ-kie)

- Mandarin: 世界 (zh) (shìjiè)

- Min Dong: 世界 (sié-gái)

- Min Nan: 世界 (zh-min-nan) (sè-kài)

- Wu: 世界 (sr jia)

- Coptic: ⲕⲟⲥⲙⲟⲥ m (kosmos), ⲑⲟ m (tho)

- Cornish: bys m, bes m

- Czech: svět (cs) m

- Danish: menneskehed c, verden (da) c

- Dhivehi: ދުނިޔެ (duniye)

- Dutch: wereld (nl) f or m

- Esperanto: mondo (eo)

- Estonian: maailm (et)

- Evenki: дуннэ (dunnə), буга (buga)

- Extremaduran: mundu m

- Faroese: verøld, heimur (fo) m, verð f

- Finnish: maailma (fi)

- French: monde (fr) m

- Old French: monde m

- Friulian: mond m

- Galician: mundo (gl) m

- Ge’ez: ዓለም (ʿaläm)

- Georgian: სამყარო (samq̇aro), მსოფლიო (msoplio)

- German: Welt (de) f

- Gothic: 𐌼𐌰𐌽𐌰𐍃𐌴𐌸𐍃 f (manasēþs)

- Greek: κόσμος (el) m (kósmos)

- Ancient: κόσμος m (kósmos), οἰκουμένη f (oikouménē)

- Guaraní: arapy

- Gujarati: વિશ્વ m (viśva)

- Hawaiian: honua

- Hebrew: עוֹלָם (he) m (olám)

- Higaonon: kalibutan

- Hindi: दुनिया (hi) f (duniyā), लोक (hi) m (lok), विश्व (hi) m (viśva), संसार (hi) m (sansār), जगत (hi) m (jagat), पृथ्वी (hi) f (pŕthvī), आलम (hi) m (ālam), जहान (hi) m (jahān), ज़माना m (zamānā), जमाना (hi) m (jamānā), जग (hi) m (jag), प्रपंच (hi) m (prapañc)

- Hungarian: világ (hu)

- Icelandic: veröld (is) f, heimur (is) m

- Ido: mondo (io)

- Indonesian: dunia (id)

- Ingrian: maailma

- Interlingua: mundo

- Irish: saol m, bith (ga) m

- Old Irish: domun m

- Isan: please add this translation if you can

- Istriot: mondo m

- Italian: mondo (it) m

- Japanese: 世界 (ja) (せかい, sekai), 世 (ja) (よ, yo)

- Javanese: donya (jv), jagad (jv)

- Kalmyk: делкә (delkä)

- Kannada: ವಿಶ್ವ (kn) (viśva)

- Kashubian: swiat m

- Kazakh: әлем (kk) (älem), дүние (kk) (dünie), жаһан (jahan)

- Khmer: លោក (km) (look), ពិភពលោក (km) (piphup look)

- Korean: 세계(世界) (ko) (segye), 누리 (ko) (nuri)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: دنیا (ckb) (dinya)

- Northern Kurdish: dinya (ku)

- Kyrgyz: аалам (ky) (aalam), дүйнө (ky) (düynö)

- Lao: ໂລກ (lo) (lōk)

- Latgalian: pasauļs m

- Latin: mundus m

- Latvian: pasaule f

- Lezgi: дуьнья (dün’ä)

- Lithuanian: pasaulis (lt) m

- Livonian: īlma, mōīlma, pasouļ

- Lombard: mond (lmo) m

- Low German: Werld f

- Luxembourgish: Welt f

- Macedonian: свет m (svet)

- Malay: alam (ms), dunia (ms), jagat, loka, buana, buana

- Malayalam: ലോകം (ml) (lōkaṃ)

- Maltese: dinja (mt) f

- Maori: aotūroa, ao (mi)

- Maranao: doniya’

- Marathi: जग (jag)

- Mari:

- Eastern Mari: тӱня (tüňa)

- Megleno-Romanian: lumi f

- Middle English: world

- Mirandese: mundo m

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: дэлхий (mn) (delxii)

- Mongolian: ᠳᠡᠯᠡᠭᠡᠢ (delegei̯)

- Nanai: яло

- Neapolitan: munno m

- Nepali: संसार (sansār)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: verden (no) m, verd (no) m or f

- Nynorsk: verd f, heim m,

- Occitan: mond (oc) m

- Okinawan: 世界 (しけー, sike)

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: свѣтъ m (světŭ)

- Old East Slavic: свѣтъ m (světŭ)

- Old English: weorold f

- Old French: mund m

- Old Javanese: jagat

- Old Norse: heimr

- Old Saxon: werold f

- Oriya: ଦୁନିଆ (or) (dunia)

- Oromo: addunyaa

- Ossetian: дуне (dune)

- Pashto: نړۍ (ps) f (naṛᶕy), عالم (ps) m (‘ālam)

- Persian: جهان (fa) (jahân), دنیا (fa) (donyâ), عالم (fa) (‘âlam)

- Polish: świat (pl) m inan

- Portuguese: mundo (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਦੁਨੀਆ (dunīā)

- Rajasthani: दुनियांण (duniyā̃ṇ)

- Romanian: lume (ro)

- Romansch: mund m, mond m, muond m

- Russian: мир (ru) m (mir), свет (ru) m (svet)

- Sanskrit: जगत् (sa) n (jagat)

- Sardinian: mundhu m, mundu m, munnu m

- Scots: warld

- Scottish Gaelic: saoghal m, domhan m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: свије̑т m (Ijekavian), све̑т m (Ekavian)

- Roman: svijȇt (sh) m (Ijekavian), svȇt (sh) m (Ekavian)

- Sicilian: munnu (scn) m

- Sindhi: دنيا

- Sinhalese: ලෝකය (lōkaya)

- Slovak: svet (sk) m

- Slovene: svet (sl) m

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: swět m

- Upper Sorbian: swět m

- Spanish: mundo (es) m

- Swedish: värld (sv) c

- Sylheti: ꠖꠥꠘꠤꠀꠁ (duniai)

- Tabasaran: аьлам (a̱lam), дю’ня (dju’nja)

- Tagalog: mundo (tl)

- Tajik: ҷаҳон (tg) (jahon), дунё (tg) (dunyo), олам (olam)

- Tamil: செகம் (ta) (cekam), ஞாலம் (ta) (ñālam), பார் (ta) (pār), உலகம் (ta) (ulakam)

- Tashelhit: tilit f

- Tatar: дөнья (dön’ya)

- Telugu: ప్రపంచము (te) (prapañcamu)

- Tetum: mundu

- Thai: โลก (th) (lôok)

- Tibetan: འཛམ་གླིང (‘dzam gling)

- Tocharian A: ārkiśoṣi

- Tocharian B: śaiṣṣe

- Turkish: dünya (tr), alem (tr), cihan (tr)

- Turkmen: dünýä, älem

- Ukrainian: світ (uk) m (svit)

- Urdu: دنیا (ur) f (duniyā), جہان (jahān), عالم (ur) (‘ālam), سنسار (sansār)

- Uyghur: ئالەم (alem), دۇنيا (dunya), جاھان (jahan), زامان (zaman)

- Uzbek: dunyo (uz), jahon (uz), olam (uz)

- Venetian: móndo m

- Vietnamese: thế giới (vi) (世界 (vi))

- Volapük: vol (vo)

- Walloon: monde (wa) m

- Waray-Waray: kalibutan

- Welsh: byd (cy) m

- West Frisian: wrâld c

- Yagnobi: дунё (dunyo)

- Yakut: аан дойду (aan doydu)

- Yiddish: וועלט (yi) f (velt)

- Yup’ik: ella

- Zazaki: dınya (diq)

- Zhuang: lajmbwn

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

the earth or globe, considered as a planet.

(often initial capital letter) a particular division of the earth: the Western world.

the earth or a part of it, with its inhabitants, affairs, etc., during a particular period: the ancient world.

humankind; the human race; humanity: The world must eliminate war and poverty.

the public generally: The whole world knows it.

the class of persons devoted to the affairs, interests, or pursuits of this life: The world worships success.

a particular class of people, with common interests, aims, etc.: the fashionable world.

any sphere, realm, or domain, with all pertaining to it: a child’s world; the world of dreams; the insect world.

everything that exists; the universe; the macrocosm.

any complex whole conceived as resembling the universe: the world of the microcosm.

one of the three general groupings of physical nature: animal world; mineral world; vegetable world.

any period, state, or sphere of existence: this world; the world to come.

Often worlds. a great deal: That vacation was worlds of fun.

any indefinitely great expanse.

any heavenly body: the starry worlds.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Idioms about world

- to give birth to; bear: My grandmother brought nine children into the world.

- to deliver (a baby): the doctor brought many children into the world.

bring into the world,

come into the world, to be born: Her first child came into the world in June.

- for any consideration, however great: She wouldn’t come to visit us for all the world.

- in every respect; precisely: You look for all the world like my Aunt Mary.

- at all; ever: I never in the world would have believed such an obvious lie.

- from among all possibilities: Where in the world did you find that hat?

for all the world,

in the world,

out of this / the world, exceptional; fine: The chef prepared a roast duck that was out of this world.

set the world on fire, to achieve great fame and success: He didn’t seem to be the type to set the world on fire.

think the world of, to like or admire greatly: His coworkers think the world of him.

world without end, for all eternity; for always.

Origin of world

First recorded before 900; Middle English; Old English world, weorold; cognate with Dutch wereld, German Welt, Old Norse verǫld, all from (unnattested) Germanic wer-ald- literally, “age of man” (see virile, werewolf, old

synonym study for world

OTHER WORDS FROM world

coun·ter·world, nounin·ter·world, noun

Words nearby world

workup, workwear, workweek, workwoman, work wonders, world, World Bank, World Bank Group, world beat, worldbeater, world-building

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to world

earth, nature, everyone, group, race, realm, area, business, field, life, province, system, cosmos, creation, macrocosm, microcosm, sphere, star, universe, class

How to use world in a sentence

-

With fires burning in so many disparate corners of the world, one might assume that wildfires have been growing every year.

-

Democratic-run New Jersey and New York, with death rates of 181 and 168, respectively, would lead the entire world.

-

This makes TikTok the seventh most popular social media platform in the world.

-

Coastal wetlands have been shrinking around the world for the last century.

-

It housed humans for 40,000 years while our species grew and grew around the world.

-

The world that Black Dynamite lives in is not the most PC place to be in.

-

Have a look at this telling research from Pew on blasphemy and apostasy laws around the world.

-

Allegations of transphobia are not new in the world of gay online dating.

-

People watch night soaps because the genre allows them to believe in a world where people just react off their baser instincts.

-

Editorial and political cartoon pages from throughout the world almost unanimously came to the same conclusion.

-

Descending the Alps to the east or south into Piedmont, a new world lies around and before you.

-

All over the world the just claims of organized labor are intermingled with the underground conspiracy of social revolution.

-

There seems something in that also which I could spare only very reluctantly from a new Bible in the world.

-

That it is a reasonable and proper thing to ask our statesmen and politicians: what is going to happen to the world?

-

The «new world» was really found in the wonder-years of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

British Dictionary definitions for world (1 of 2)

noun

the earth as a planet, esp including its inhabitants

mankind; the human race

people generally; the publicin the eyes of the world

social or public lifeto go out into the world

the universe or cosmos; everything in existence

a complex united whole regarded as resembling the universe

any star or planet, esp one that might be inhabited

(often capital) a division or section of the earth, its history, or its inhabitantsthe Western World; the Ancient World; the Third World

an area, sphere, or realm considered as a complete environmentthe animal world

any field of human activity or way of life or those involved in itthe world of television

a period or state of existencethe next world

the total circumstances and experience of an individual that make up his life, esp that part of it relating to happinessyou have shattered my world

a large amount, number, or distanceworlds apart

worldly or secular life, ways, or people

all the world and his wife a large group of people of various kinds

bring into the world

- (of a midwife, doctor, etc) to deliver (a baby)

- to give birth to

come into the world to be born

dead to the world informal unaware of one’s surroundings, esp fast asleep or very drunk

for the world (used with a negative) for any inducement, however great

for all the world in every way; exactly

give to the world to publish

in the world (usually used with a negative) (intensifier)no-one in the world can change things

man of the world or woman of the world a man or woman experienced in social or public life

not long for this world nearing death

on top of the world informal exultant, elated, or very happy

informal wonderful; excellent

set the world on fire to be exceptionally or sensationally successful

the best of both worlds the benefits from two different or opposed ways of life, philosophies, etc

think the world of to be extremely fond of or hold in very high esteem

world of one’s own a state of mental detachment from other people

world without end for ever

(modifier) of or concerning most or all countries; worldwideworld politics; a world record

(in combination) throughout the worldworld-famous

Word Origin for world

Old English w (e) orold, from wer man + ald age, life; related to Old Frisian warld, wrald, Old Norse verold, Old High German wealt (German Welt)

British Dictionary definitions for world (2 of 2)

noun The World

a man-made archipelago of 300 reclaimed islands built off the coast of Dubai in the shape of a map of the world. Area: 63 sq km (24 sq miles)

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Other Idioms and Phrases with world

In addition to the idioms beginning with world

- world is one’s oyster, the

- world of good, a

also see:

- all over the place (world)

- best of both worlds

- bring into the world

- come up (in the world)

- dead to the world

- for all the world

- go out (of the world)

- in one’s own world

- it’s a small world

- laugh and the world laughs with you

- man of the world

- move up (in the world)

- not for all the tea in china (for the world)

- on earth (in the world), what

- on top of the world

- out of this world

- set the world on fire

- think a lot (the world) of

- third world

- with the best will in the world

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD WORLD

Old English w( e) orold, from wer man + ald age, life; related to Old Frisian warld, wrald, Old Norse verold, Old High German wealt (German Welt).

Etymology is the study of the origin of words and their changes in structure and significance.

PRONUNCIATION OF WORLD

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF WORLD

World is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES WORLD MEAN IN ENGLISH?

World

World is a common name for the whole of human civilization, specifically human experience, history, or the human condition in general, worldwide, i.e. anywhere on Earth or pertaining to anywhere on earth. In a philosophical context it may refer to: ▪ the whole of the physical Universe, or ▪ an ontological world. In a theological context, world usually refers to the material or the profane sphere, as opposed to the celestial, spiritual, transcendent or sacred. The «end of the world» refers to scenarios of the final end of human history, often in religious contexts. World history is commonly understood as spanning the major geopolitical developments of about five millennia, from the first civilizations to the present. World population is the sum of all human populations at any time; similarly, world economy is the sum of the economies of all societies, especially in the context of globalization. Terms like world championship, gross world product, world flags etc. also imply the sum or combination of all current-day sovereign states.

Definition of world in the English dictionary

The first definition of world in the dictionary is the earth as a planet, esp including its inhabitants. Other definition of world is mankind; the human race. World is also people generally; the public.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH WORLD

Synonyms and antonyms of world in the English dictionary of synonyms

SYNONYMS OF «WORLD»

The following words have a similar or identical meaning as «world» and belong to the same grammatical category.

Translation of «world» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF WORLD

Find out the translation of world to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of world from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «world» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

世界

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

mundo

570 millions of speakers

English

world

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

दुनिया

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

عَالَم

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

мир

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

mundo

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

বিশ্ব

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

monde

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Dunia

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Welt

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

世界

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

세계

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Donya

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

thế giới

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

உலக

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

जग

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

Dünya

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

mondo

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

świat

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

світ

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

pământ

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

κόσμος

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

wêreld

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

värld

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

verden

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of world

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «WORLD»

The term «world» is very widely used and occupies the 266 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «world» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of world

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «world».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «WORLD» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «world» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «world» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about world

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «WORLD»

Discover the use of world in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to world and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

The World Book Encyclopedia: So-Sz

«A 22-volume, highly illustrated, A-Z general encyclopedia for all ages, featuring sections on how to use World Book, other research aids, pronunciation key, a student guide to better writing, speaking, and research skills, and …

2

The World Book Encyclopedia: T.

An encyclopedia designed especially to meet the needs of elementary, junior high, and senior high school students.

Vol. 1— A., World Book, Inc, 1989

3

The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way

The question is whether the startling perspective provided by this masterly book can also generate the will to make changes” (The New York Times Book Review).

Rooted in the creative success of over 30 years of supermarket tabloid publishing, the Weekly World News has been the world’s only reliable news source since 1979. The online hub www.weeklyworldnews.com is a leading entertainment news site.

Here is the story of a precarious childhood, with an alcoholic father (who would die when she was nine) and a devoted but overburdened mother, and of the refuge a little girl took from the turmoil at home with her passionately spirited …

Rooted in the creative success of over 30 years of supermarket tabloid publishing, the Weekly World News has been the world’s only reliable news source since 1979. The online hub www.weeklyworldnews.com is a leading entertainment news site.

7

The Wettest County in the World: A Novel Based on a True Story

Based on the true story of Matt Bondurant’s grandfather and two granduncles, The Wettest County in the World is a gripping tale of brotherhood, greed, and murder.

This book presents the far-reaching argument that not only should we have a new world order but that we already do. Anne-Marie Slaughter asks us to completely rethink how we view the political world.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, 2009

9

Black World/Negro Digest

Founded in 1943, Negro Digest (later “Black World”) was the publication that launched Johnson Publishing.

10

Rabelais and His World

This classic work by the Russian philosopher and literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975) examines popular humor and folk culture in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich Bakhtin, 1984

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «WORLD»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term world is used in the context of the following news items.

UNESCO’s newest World Heritage Sites

(CNN) There’s the site where Jesus was believed to have been baptized by John the Baptist. And then there are the spots where French Champagne and … «CNN, Jul 15»

In a Rout and a Romp, US Takes World Cup

VANCOUVER, British Columbia — The Women’s World Cup began uncertainly for midfielder Carli Lloyd. But it quickly built toward predatory dependability, then … «New York Times, Jul 15»

What’s Really Warming the World?

Skeptics of manmade climate change offer various natural causes to explain why the Earth has warmed 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880. But can these … «Bloomberg, Jun 15»

World Investment Report 2015 — Reforming International Investment …

This year’s World Investment Report, the 25th in the series, aims to inform global debates on the future of the international policy environment for cross-border … «UNCTAD, Jun 15»

Who Won the Women’s World Cup of Arm-Folding?

Watching the 2015 Women’s World Cup has been an exciting ride. Viewers got to cheer for more teams than have competed than ever before, including eight … «Slate Magazine, Jun 15»

‘I enjoyed the whole absurdity of it’: Paleontologists review ‘Jurassic …

Explaining the concept of this review is like explaining a dream. «I went to go see ‘Jurassic World‘ before the film was in theaters, but instead of my friends, … «Washington Post, Jun 15»

New World Trade Center tower will honor the old and the new

(CNN) Bjarke Ingels Group have revealed the designs for the new building at Two World Trade Center. Browse through the gallery to see all the images. «CNN, Jun 15»

Complete 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup schedule, TV listings

The Women’s World Cup link is right next nascar, under the More tab. … Well… old stories and photos of the men’s World Cup last year were easier to find on … «CBSSports.com, Jun 15»

World Health Assembly addresses antimicrobial resistance …

25 MAY 2015 ¦ GENEVA — The World Health Assembly today agreed resolutions to tackle antimicrobial resistance; improve access to affordable vaccines and … «World Health Organization, May 15»

Gaza Economy on the Verge of Collapse, Youth Unemployment …

JERUSALEM, May 21, 2015 — Blockades, war and poor governance have strangled Gaza’s economy and the unemployment rate is now the highest in the world … «World Bank Group, May 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. World [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/world>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on