The noun sport is a shortening of disport, which was borrowed in the early 14th century from Anglo-Norman and Old and Middle French forms such as desport, deport, disport (modern French déport). This French word was thus defined by Randle Cotgrave in A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (1611):

Deport: masculine. Disport, sport, pastime, recreation; pleasure.

These Anglo-Norman and French forms are from the verb desporter, deporter, etc. (modern French déporter), which, among other meanings such as to deport, had that of to entertain, amuse. In the above-mentioned dictionary, Randle Cotgrave thus defined the reflexive form:

Se deporter. […] to disport, play, recreate himselfe, passe away the time.

The French verb is from Latin deportare, to carry away. The French verbs divertir (cf. English divert) and distraire (cf. distract), which also mean to entertain, amuse, have had a similar semantic development (divertir is based on Latin vertere, to turn, and distraire on Latin trahere, to draw, drag), the notion common to these three verbs being that of turning, leading or carrying away the attention from serious or sad occupations.

One of the first known users of the English noun, in the sense of diversion from work or serious matters, was the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1342-1400) in The Man of Law’s Tale:

(interlinear translation)

Now fil it that the maistres of that sort

Now it happened that the masters of that company

Han shapen hem to Rome for to wende;

Have prepared themselves to travel to Rome;

Were it for chapmanhod or for disport.

Were it for business or for pleasure.

In the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer used the word in the sense of deportment, that is, behaviour, manners:

(interlinear translation)

And sikerly she was of greet desport,

And surely she was of excellent deportment,

And ful plesaunt, and amyable of port,

And very pleasant, and amiable in demeanour,

And peyned hire to countrefete cheere

And she took pains to imitate the manners

Of court, and to been estatlich of manere,

Of court, and to be dignified in behaviour,

And to ben holden digne of reverence.

And to be considered worthy of reverence.

The English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616) used disport to mean sexual intercourse in The Tragœdy of Othello, The Moore of Venice (around 1603). When the Duke of Venice decides that Othello must go to Cyprus to defend the island from the Turks, Othello accepts but asks that appropriate accommodations be provided for his wife, Desdemona. He explains that if her presence makes him neglect his official duties, if his “disports corrupt and taint” his business, then housewives can make a skillet of his helmet:

(Quarto 1, 1622)

I therefore beg it not

To please the pallat of my appetite,

Nor to comply with heate, the young affects

In my defunct, and proper satisfaction,

But to be free and bounteous of her mind,

And heauen defend your good soules that you thinke

I will your serious and good businesse scant,

For she is with me; — no, when light-winged toyes,

And feather’d Cupid foyles with wanton dulnesse,

My speculatiue and actiue instruments,

That my disports, corrupt and taint my businesse,

Let huswiues make a skellett of my Helme,

And all indigne and base aduersities,

Make head against my reputation.

The noun sport appeared in the early 15th century in the same senses relating to play, pleasure or entertainment. Its first known instance is in Medulla Grammatice (The core of the grammatical (art) – around 1425), a compilation of Latin words with English meanings:

Lecta, sporte of redynge.

In the sense of an activity involving physical exertion and skill in which an individual or team competes against another or others for entertainment, sport is first attested in an act of the Parliament of Scotland in 1491, under the reign of James IV (1473-1513, reigned 1488-1513); it was ordained

that in na place of the realme be vsit fut bawis gouff or vthir sic vnproffitable sportis bot for commoun gude & defence of the realme be hantit bowis schvting and markis.

literal translation:

that in no place of the realm be used foot balls, golf or other unprofitable sports, but for common good and defence of the realm be practised bow-shooting and marks [= targets or butts set up for shooting at].

The term field sport, denoting an outdoor sport or recreation, especially hunting, shooting or fishing, is first recorded in A posie of gilloflowers eche differing from other in colour and odour, yet all sweete (1580), by the poet Humphrey Gifford (floruit 1580); he wrote the following in the dedication “To the Worshipfull John Stafford of Bletherwicke Esquier”:

The thing that I here present you with, is but a collection of such verses and odde deuises as haue (at such idle howres as I founde in my maister his seruice) vpon sundry occasions by me byn cōposed. The one I confesse farre vnworthy your view, and yet such as when ye shal returne home weeried from your fielde sportes, may yeelde you some recreation.

However, in early use, the sense of sport as a diversion or amusement was predominant. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the term was often used with reference to hunting, shooting and fishing, as in blood sport, a term dating back to the 19th century and meaning a sport involving the hunting, wounding or killing of animals. In the 19th century, the consolidation of organised sport, particularly football, rugby, cricket and athletics, reinforced the notion of sport as physical competition.

In this later sense, the English word has been borrowed into numerous other languages. In French for instance, sport, doublet of déport, is first attested in May 1828 in the Journal des haras (Journal of the stud farms), in which sport was explained as “la chasse, les courses, les combats de boxeurs” (“hunting, horse racing, boxing matches”).

Table of Contents

- What is the original meaning of sport?

- What does sports mean in Latin?

- What does the Greek word athlete mean?

- What is the Greek word for Olympics?

- What is another name for athlete?

- What does sportsperson mean?

- What is another name for team?

- How would you describe an athlete?

- What 3 words would you use to describe yourself as an athlete?

- What are the good qualities of an athlete?

- What makes you a good athlete?

- Who is the most popular athlete?

- What skills do athletes need?

- Who is the greatest athlete of all time?

- What sport is the hardest?

- Who are the 3 greatest athletes of all time?

- Who is the best female athlete in the world?

- Who is the greatest Olympian of all time?

- Are Japan Olympics Cancelled?

- Which country has the most gold medals?

- Who is the richest Olympian?

- Why do Olympians get condoms?

- Why Olympians bite their medals after winning?

- Do Olympians keep their medals?

The word “sport” itself has been around in the English language since the mid-15th century, when it was derived from the Old French desporter, meaning “to amuse, please, or play.” As a noun denoting a physical game or activity, the word grew in popularity in the late-15th century, also acquiring, in the 18th century.

What is the original meaning of sport?

The word “sport” comes from the Old French desport meaning “leisure”, with the oldest definition in English from around 1300 being “anything humans find amusing or entertaining”. Roget’s defines the noun sport as an “activity engaged in for relaxation and amusement” with synonyms including diversion and recreation.

What does sports mean in Latin?

1400, “to take pleasure, to amuse oneself,” from Old French desporter, deporter “to divert, amuse, please, play; to seek amusement,” literally “carry away” (the mind from serious matters), from des- “away” (see dis-) + porter “to carry,” from Latin portare “to carry” (from PIE root *per- (2) “to lead, pass over”).

What does the Greek word athlete mean?

In fact, the word athlete is an ancient Greek word that means “one who competes for a prize” and was related to two other Greek words, athlos meaning “contest” and athlon meaning “prize.”

What is the Greek word for Olympics?

olimpiakos

What is another name for athlete?

player

- amateur.

- athlete.

- champ.

- competitor.

- contestant.

- jock.

- member.

- opponent.

What does sportsperson mean?

noun. a person who takes part in sports, esp of the outdoor type.

What is another name for team?

Synonyms of team

- army,

- band,

- brigade,

- company,

- crew,

- gang,

- outfit,

- party,

How would you describe an athlete?

Here are some adjectives for athlete: red-haired natural, promising all-round, damned sexual, erstwhile professional, bold and sinewy, strong and gifted, vivacious, enthusiastic, clear-eyed, supple, general or famous, young journalistic, young, cheery, painstaking or excellent, naturally painstaking or excellent.

What 3 words would you use to describe yourself as an athlete?

If you answer YES! to a lot of these characteristics…then yes, you ARE an ATHLETE!

- Motivated.

- Passionate.

- Disciplined.

- Committed.

- Optimistic.

- Persistent.

- Supportive.

- Competitive.

What are the good qualities of an athlete?

Here we’ll reveal 7 of the top traits that help phenomenal sports stars thrive.

- Supreme Concentration. Truly great athletes have an almost innate ability to get into the zone when they need to.

- Commitment to Excellence.

- Desire and Motivation.

- Goal Setting.

- Positive Mind-state and Optimism.

- Confidence and Self-Belief.

What makes you a good athlete?

Motivation: High-performing athletes are motivated by the desire to be better than their opponent and even better than their personal best. They will be patient and persevere when working on their skills and focusing on their goals. 3. Self-Discipline: Elite athletes know that success doesn’t happen overnight.

Who is the most popular athlete?

The 20 most famous athletes in the world

- No. 1 Cristiano Ronaldo. Sport: Soccer.

- No. 2 LeBron James. Sport: Basketball.

- No. 3 Lionel Messi. Sport: Soccer.

- No. 4 Neymar Jr. Sport: Soccer.

- No. 5 Roger Federer. Sport: Tennis.

- No. 6 Kevin Durant. Sport: Basketball.

- No. 7 Tiger Woods. Sport: Golf.

- No. 8 James Rodriguez. Sport: Soccer.

What skills do athletes need?

Successful Athletes:

- Choose and maintain a positive attitude.

- Maintain a high level of self-motivation.

- Set high, realistic goals.

- Deal effectively with people.

- Use positive self-talk.

- Use positive mental imagery.

- Manage anxiety effectively.

- Manage their emotions effectively.

Who is the greatest athlete of all time?

The Greatest Athlete of All Time title goes to Bo Jackson. This was based on the comparison of a range of sport science metrics. Even without the science, public vote had him well ahead – after 27,397 votes Jackson was well ahead with 79.5% of the votes.

What sport is the hardest?

| Degree of Difficulty: Sport Rankings | ||

|---|---|---|

| SPORT | END | RANK |

| Boxing | 8.63 | 1 |

| Ice Hockey | 7.25 | 2 |

| Football | 5.38 | 3 |

Who are the 3 greatest athletes of all time?

The Top 7 All-Time Best Athletes

- Muhammad Ali.

- Pele.

- Michael Phelps.

- Martina Navratilova.

- Jesse Owens.

- Nadia Comaneci.

- Michael Jordan.

Who is the best female athlete in the world?

Jackie Joyner-Kersee

Who is the greatest Olympian of all time?

Michael Phelps

Are Japan Olympics Cancelled?

Japan’s Asahi Shimbun, an official partner of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, called for the Summer Games to be cancelled in an editorial on Wednesday, citing risks to public safety and strains on the medical system from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Which country has the most gold medals?

United States

Who is the richest Olympian?

Caitlyn Jenner

Why do Olympians get condoms?

They’ll be asked to bring the condoms to their home countries as a way of raising awareness of HIV and AIDS, Reuters reported. When the International Olympic Committee rolled out its rules in February, they included a ban on physical contact between athletes.

Why Olympians bite their medals after winning?

According to the Olympic Channel, the origin of biting into a medal comes from merchant’s regularly biting into coins to make sure they weren’t forgeries. “Historically, gold was alloyed with other, harder metals to make it harder. So if biting the coin left teeth marks, the merchant would know it was a fake.”

Do Olympians keep their medals?

While these Olympians keep their medals in various spots, not all Olympians actually keep their medals, though. Some sell them. After putting the medal up on eBay, he donated the $17,101 made to the cause. While Klitschko and Ervin chose to sell their medals, some Olympians may have no other choice but to.

Of OE spyrd Bowsorth-Toller says,

The word glosses stadium (1) with the meaning a course :— Ða ðe in spyrde iornaþ qui in stadio currunt, Rtl. 5, 33. (2) with the meaning a measure of distance :— Swelce spyrdas fífténe (spyrdum fífténum, Lind.) quasi stadiis quindecim, Jn. Skt. Rush. 11, 18. Swelce spyrdo fífe and twoegentig quasi stadia .xxv., 6, 19. Ðara spyrda stadiorum, Lk. Skt. Lind. Rush. 24, 13. In all these passages the West-Saxon uses furlang. [Goth. spaurds (1) a course; (2) a distance: O. H. Ger. spurt stadium.]

It is not clear whether the ‘racecourse’ sense derives from the ‘distance’ sense or vice versa; the same is true of the Latin word it glosses, stadium, although the Online Etymology Dictionary suggests the Greek original of the Latin term suggests that the ‘distance’ sense was prior.

This is a very shaky foundation upon which to build an origin for ModE sport—especially since I find no evidence that the OE term survived into ME.

As OP points out, Middle English Dictionary gives sport(e with the senses:

(a) Amusement, entertainment; pleasure, fun; also, an activity that brings pleasure or amusement; a pastime or game; also, ?a sexual exploit, an amorous deed [quot. ?c1450, 2nd]; don sportes, to play games; haven (taken) ~, take (one’s) pleasure, have fun; ?participate in merrymaking; maken ~, create amusement, make sport; (b) a source of pleasure or delight; (c) joking; foolery; in ~, in jest; connen no ~, to engage in no foolery.

Solace, consolation; also, ?a means of comfort or consolation; maken ~, to console (sb.), cheer up.

There are also related words, sportaunce, sportelet, sporten, sportful, sporting.

MED sees all of these as «Shortened form[s] of disport«, «disporten, &c., which first appear in ME a generation earlier than sport(e and its relatives. For the noun MED gives the following senses:

(a) An activity that offers amusement, pleasure, or relaxation; entertainment, merry-making, fun, recreation; maken ~, to entertain (sb.); taken ~, amuse oneself, have fun; (b) a pastime, sport, or game; also, the game of love, flirtation; (c) in ~, in jest.

(a) Pleasure taken in an activity or enjoyment derived from it; haven ~, to take pleasure (in sth.), be gratified; (b) consolation, solace; a source of comfort; don ~, to cheer (sb.) up.

(a) Deportment, conduct; customary behavior, custom, manner; (b) an instance of behavior, an act or activity; don ~, to do something.

Departure; maken ~, to set out (for a place).

The first two of these senses are clearly identical with those of sport(e. They carry over into EME, whence they give rise to the modern senses.

Among the «disportes» mentioned by the MED citations are dice, reveling, minstrels singing songs and telling jests, and finding Venus on a bed of gold, as well as recreations which would be regarded as «sports» today, hawking, hunting, angling, archery.

None of the citations alludes to racing or reflects (except for one allusion to the «actes and disportes Olimpicalle») a sense of «competitive» sport.

And there is no other MED headword of the form sp?rt*, sp?rd*, spr?t*, or spr?d* which could be taken as derivative of spyrd.

It looks like the similarity of the OE term is coincidental, since it cannot be traced into ME.

What is the origin of the word sport?

The word “sport” comes from the Old French desport meaning “leisure”, with the oldest definition in English from around 1300 being “anything humans find amusing or entertaining”. Roget’s defines the noun sport as an “activity engaged in for relaxation and amusement” with synonyms including diversion and recreation.

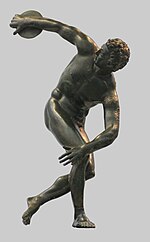

What is the origin of games and sports?

The documented history of sports goes back at least 3,000 years. With the first Olympic Games in 776 BC—which included events such as foot and chariot races, wrestling, jumping, and discus and javelin throwing—the Ancient Greeks introduced formal sports to the world.

When was the word sport first used?

The word “sport” itself has been around in the English language since the mid-15th century, when it was derived from the Old French desporter, meaning “to amuse, please, or play.” As a noun denoting a physical game or activity, the word grew in popularity in the late-15th century, also acquiring, in the 18th century.

Where does the word sport come from in English?

The noun sport is a shortening of disport, which was borrowed in the early 14th century from Anglo-Norman and Old and Middle French forms such as desport, deport, disport (modern French déport). This French word was thus defined by Randle Cotgrave in A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (1611):

Where did the sport of basketball come from?

In contrast to other sports, basketball has a clear origin. It is not the evolution from an ancient game or another sport and the inventor is well known: Dr. James Naismith . Naismith was born in 1861 in Ramsay township, Ontario, Canada.

What is the meaning of ” old sport “?

Meaning “game involving physical exercise” first recorded 1520s. Sense of “stylish man” is from 1861, American English, probably because they lived by gambling and betting on races. Meaning “good fellow” is attested from 1881 (as in be a sport, 1913). Sport as a familiar form of address to a man is from 1935, Australian English.

Where did the sport of baseball come from?

A more recent ancestry of the sport can be found in Europe, from where it most certainly immigrated to the United States. Baseball bears a significant resemblance to English pastimes such as rounders and cricket. We also know of a similar game played by French monks around the 1330s, and the sport of oina played in Romania.

What was the first sport ever to be invented?

Hunting, being an activity that was crucial to early humans, has often been lauded as the world’s first sport.

What sports originated in the US?

There are at least three sports that originated in the United States. Basketball, Volleyball, invented in Holyoke , Massachusetts, by William Morgan in 1895, for sedentary businessmen who found the new sport of basketball too strenuous. Rodeo, first formalized as a sport in Prescott , Arizona.

What is the history of sports in America?

The typical American sports of baseball, basketball ad foot ball, however, arose from games that were brought to America by the first settlers that arrived from Europe in the 17th century. These games were re-fashioned and elaborated in the course of the 19th century and are now the most popular sports in the United States.

What is the earliest sport?

Wrestling is considered the oldest sport in the world. Its origins can be dated back to 15,000 years in the French cave paintings. It involves grappling techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns to name a few, employed by one competitor on the other in order to gain supremacy.

The 2005 London Marathon: running races, in their various specialties, represent the oldest and most traditional form of sport.

Sport pertains to any form of physical activity or game,[1] often competitive and organised, that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators.[2] Sports can, through casual or organised participation, improve participants’ physical health. Hundreds of sports exist, from those between single contestants, through to those with hundreds of simultaneous participants, either in teams or competing as individuals. In certain sports such as racing, many contestants may compete, simultaneously or consecutively, with one winner; in others, the contest (a match) is between two sides, each attempting to exceed the other. Some sports allow a «tie» or «draw», in which there is no single winner; others provide tie-breaking methods to ensure one winner and one loser. A number of contests may be arranged in a tournament producing a champion. Many sports leagues make an annual champion by arranging games in a regular sports season, followed in some cases by playoffs.

Sport is generally recognised as system of activities based in physical athleticism or physical dexterity, with major competitions such as the Olympic Games admitting only sports meeting this definition.[3] Other organisations, such as the Council of Europe, preclude activities without a physical element from classification as sports.[2] However, a number of competitive, but non-physical, activities claim recognition as mind sports. The International Olympic Committee (through ARISF) recognises both chess and bridge as bona fide sports, and SportAccord, the international sports federation association, recognises five non-physical sports: bridge, chess, draughts (checkers), Go and xiangqi,[4][5] and limits the number of mind games which can be admitted as sports.[1]

Sport is usually governed by a set of rules or customs, which serve to ensure fair competition, and allow consistent adjudication of the winner. Winning can be determined by physical events such as scoring goals or crossing a line first. It can also be determined by judges who are scoring elements of the sporting performance, including objective or subjective measures such as technical performance or artistic impression.

Records of performance are often kept, and for popular sports, this information may be widely announced or reported in sport news. Sport is also a major source of entertainment for non-participants, with spectator sport drawing large crowds to sport venues, and reaching wider audiences through broadcasting. Sport betting is in some cases severely regulated, and in some cases is central to the sport.

According to A.T. Kearney, a consultancy, the global sporting industry is worth up to $620 billion as of 2013.[6] The world’s most accessible and practised sport is running, while association football is the most popular spectator sport.[7]

Meaning and usage

Etymology

The word «sport» comes from the Old French desport meaning «leisure», with the oldest definition in English from around 1300 being «anything humans find amusing or entertaining».[8]

Other meanings include gambling and events staged for the purpose of gambling; hunting; and games and diversions, including ones that require exercise.[9] Roget’s defines the noun sport as an «activity engaged in for relaxation and amusement» with synonyms including diversion and recreation.[10]

Nomenclature

The singular term «sport» is used in most English dialects to describe the overall concept (e.g. «children taking part in sport»), with «sports» used to describe multiple activities (e.g. «football and rugby are the most popular sports in England»). American English uses «sports» for both terms.

Definition

The precise definition of what differentiates a sport from other leisure activities varies between sources. The closest to an international agreement on a definition is provided by the Global Association of International Sports Federations (GAISF), which is the association for all the largest international sports federations (including association football, athletics, cycling, tennis, equestrian sports, and more), and is therefore the de facto representative of international sport.

GAISF uses the following criteria, determining that a sport should:[1]

- have an element of competition

- be in no way harmful to any living creature

- not rely on equipment provided by a single supplier (excluding proprietary games such as arena football)

- not rely on any «luck» element specifically designed into the sport.

They also recognise that sport can be primarily physical (such as rugby or athletics), primarily mind (such as chess or Go), predominantly motorised (such as Formula 1 or powerboating), primarily co-ordination (such as billiard sports), or primarily animal-supported (such as equestrian sport).[1]

The inclusion of mind sports within sport definitions has not been universally accepted, leading to legal challenges from governing bodies in regards to being denied funding available to sports.[11] Whilst GAISF recognises a small number of mind sports, it is not open to admitting any further mind sports.

There has been an increase in the application of the term «sport» to a wider set of non-physical challenges such as video games, also called esports (from «electronic sports»), especially due to the large scale of participation and organised competition, but these are not widely recognised by mainstream sports organisations. According to Council of Europe, European Sports Charter, article 2.i, «‘Sport’ means all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels.»[12]

Competition

There are opposing views on the necessity of competition as a defining element of a sport, with almost all professional sports involving competition, and governing bodies requiring competition as a prerequisite of recognition by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) or GAISF. [1]

Other bodies advocate widening the definition of sport to include all physical activity. For instance, the Council of Europe include all forms of physical exercise, including those competed just for fun.

In order to widen participation, and reduce the impact of losing on less able participants, there has been an introduction of non-competitive physical activity to traditionally competitive events such as school sports days, although moves like this are often controversial.[13][14]

In competitive events, participants are graded or classified based on their «result» and often divided into groups of comparable performance, (e.g. gender, weight and age). The measurement of the result may be objective or subjective, and corrected with «handicaps» or penalties. In a race, for example, the time to complete the course is an objective measurement. In gymnastics or diving the result is decided by a panel of judges, and therefore subjective. There are many shades of judging between boxing and mixed martial arts, where victory is assigned by judges if neither competitor has lost at the end of the match time.

History

Artifacts and structures suggest sport in China as early as 2000 BC.[15] Gymnastics appears to have been popular in China’s ancient past. Monuments to the Pharaohs indicate that a number of sports, including swimming and fishing, were well-developed and regulated several thousands of years ago in ancient Egypt.[16] Other Egyptian sports included javelin throwing, high jump, and wrestling. Ancient Persian sports such as the traditional Iranian martial art of Zoorkhaneh had a close connection to warfare skills.[17] Among other sports that originated in ancient Persia are polo and jousting. The traditional South Asian sport of kabaddi has been played for thousands of years, potentially as a preparation for hunting.[18]

A wide range of sports were already established by the time of Ancient Greece and the military culture and the development of sport in Greece influenced one another considerably. Sport became such a prominent part of their culture that the Greeks created the Olympic Games, which in ancient times were held every four years in a small village in the Peloponnesus called Olympia.[19]

Sports have been increasingly organised and regulated from the time of the ancient Olympics up to the present century. Industrialisation has brought motorised transportation and increased leisure time, letting people attend and follow spectator sports and participate in athletic activities. These trends continued with the advent of mass media and global communication. Professionalism became prevalent, further adding to the increase in sport’s popularity, as sports fans followed the exploits of professional athletes – all while enjoying the exercise and competition associated with amateur participation in sports. Since the turn of the 21st century, there has been increasing debate about whether transgender sports people should be able to participate in sport events that conform with their post-transition gender identity.[20]

Fair play

Sportsmanship

Sportsmanship is an attitude that strives for fair play, courtesy toward teammates and opponents, ethical behaviour and integrity, and grace in victory or defeat.[21][22][23]

Sportsmanship expresses an aspiration or ethos that the activity will be enjoyed for its own sake. The well-known sentiment by sports journalist Grantland Rice, that it is «not that you won or lost but how you played the game», and the modern Olympic creed expressed by its founder Pierre de Coubertin: «The most important thing… is not winning but taking part» are typical expressions of this sentiment.

Cheating

Key principles of sport include that the result should not be predetermined, and that both sides should have equal opportunity to win. Rules are in place to ensure fair play, but participants can break these rules in order to gain advantage.

Participants may cheat in order to unfairly increase their chance of winning, or in order to achieve other advantages such as financial gains. The widespread existence of gambling on the results of sports events creates a motivation for match fixing, where a participant or participants deliberately work to ensure a given outcome rather than simply playing to win.

Doping and drugs

The competitive nature of sport encourages some participants to attempt to enhance their performance through the use of medicines, or through other means such as increasing the volume of blood in their bodies through artificial means.

All sports recognised by the IOC or SportAccord are required to implement a testing programme, looking for a list of banned drugs, with suspensions or bans being placed on participants who test positive for banned substances.

Violence

Violence in sports involves crossing the line between fair competition and intentional aggressive violence. Athletes, coaches, fans, and parents sometimes unleash violent behaviour on people or property, in misguided shows of loyalty, dominance, anger, or celebration. Rioting or hooliganism by fans in particular is a problem at some national and international sporting contests.[citation needed]

Participation

Gender participation

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

Female participation in sports continues to rise alongside the opportunity for involvement and the value of sports for child development and physical fitness. Despite increases in female participation during the last three decades, a gap persists in the enrolment figures between male and female players in sports-related teams. Female players account for 39% of the total participation in US interscholastic athletics.

Certain sports are mixed-gender, allowing (or even requiring) men and women to play on the same team. One example of this is Baseball5, which is the first mixed-gender sport to have been admitted into an Olympic event.[24]

Youth participation

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

Youth sport presents children with opportunities for fun, socialisation, forming peer relationships, physical fitness, and athletic scholarships. Activists for education and the war on drugs encourage youth sport as a means to increase educational participation and to fight the illegal drug trade. According to the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, the biggest risk for youth sport is death or serious injury including concussion. These risks come from running, basketball, association football, volleyball, gridiron, gymnastics, and ice hockey.[25] Youth sport in the US is a $15 billion industry including equipment up to private coaching.[26]

Disabled participation

Disabled sports also adaptive sports or parasports, are sports played by people with a disability, including physical and intellectual disabilities. As many of these are based on existing sports modified to meet the needs of people with a disability, they are sometimes referred to as adapted sports. However, not all disabled sports are adapted; several sports that have been specifically created for people with a disability have no equivalent in able-bodied sports.

Spectator involvement

Spectators at the 1906 unofficial Olympic Games

The competition element of sport, along with the aesthetic appeal of some sports, result in the popularity of people attending to watch sport being played. This has led to the specific phenomenon of spectator sport.

Both amateur and professional sports attract spectators, both in person at the sport venue, and through broadcast media including radio, television and internet broadcast. Both attendance in person and viewing remotely can incur a sometimes substantial charge, such as an entrance ticket, or pay-per-view television broadcast. Sports league and tournament are two common arrangements to organise sport teams or individual athletes into competing against each other continuously or periodically.

It is common for popular sports to attract large broadcast audiences, leading to rival broadcasters bidding large amounts of money for the rights to show certain events. The football World Cup attracts a global television audience of hundreds of millions; the 2006 final alone attracted an estimated worldwide audience of well over 700 million and the 2011 Cricket World Cup Final attracted an estimated audience of 135 million in India alone.[27]

In the United States, the championship game of the NFL, the Super Bowl, has become one of the most watched television broadcasts of the year.[28][29]

Super Bowl Sunday is a de facto national holiday in America;[30][31] the viewership being so great that in 2015, advertising space was reported as being sold at $4.5m for a 30-second slot.[28]

Amateur and professional

Women’s volleyball team of a U.S. university

Sport can be undertaken on an amateur, professional or semi-professional basis, depending on whether participants are incentivised for participation (usually through payment of a wage or salary). Amateur participation in sport at lower levels is often called «grassroots sport».[2][32]

The popularity of spectator sport as a recreation for non-participants has led to sport becoming a major business in its own right, and this has incentivised a high paying professional sport culture, where high performing participants are rewarded with pay far in excess of average wages, which can run into millions of dollars.[33]

Some sports, or individual competitions within a sport, retain a policy of allowing only amateur sport. The Olympic Games started with a principle of amateur competition with those who practised a sport professionally considered to have an unfair advantage over those who practised it merely as a hobby.[34] From 1971, Olympic athletes were allowed to receive compensation and sponsorship,[35] and from 1986, the IOC decided to make all professional athletes eligible for the Olympics,[35][36] with the exceptions of boxing,[37][38] and wrestling.[39][40]

Technology

Technology plays an important part in modern sport. It is a necessary part of some sports (such as motorsport), and it is used in others to improve performance. Some sports also use it to allow off-field decision making.

Sports science is a widespread academic discipline, and can be applied to areas including athlete performance, such as the use of video analysis to fine-tune technique, or to equipment, such as improved running shoes or competitive swimwear. Sports engineering emerged as a discipline in 1998 with an increasing focus not just on materials design but also the use of technology in sport, from analytics and big data to wearable technology.[41] In order to control the impact of technology on fair play, governing bodies frequently have specific rules that are set to control the impact of technical advantage between participants. For example, in 2010, full-body, non-textile swimsuits were banned by FINA, as they were enhancing swimmers’ performances.[42][43]

The increase in technology has also allowed many decisions in sports matches to be taken, or reviewed, off-field, with another official using instant replays to make decisions. In some sports, players can now challenge decisions made by officials. In Association football, goal-line technology makes decisions on whether a ball has crossed the goal line or not.[44] The technology is not compulsory,[45] but was used in the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil,[46] and the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup in Canada,[47] as well as in the Premier League from 2013–14,[48] and the Bundesliga from 2015–16.[49] In the NFL, a referee can ask for a review from the replay booth, or a head coach can issue a challenge to review the play using replays. The final decision rests with the referee.[50] A video referee (commonly known as a Television Match Official or TMO) can also use replays to help decision-making in rugby (both league and union).[51][52] In international cricket, an umpire can ask the Third umpire for a decision, and the third umpire makes the final decision.[53][54] Since 2008, a decision review system for players to review decisions has been introduced and used in ICC-run tournaments, and optionally in other matches.[53][55] Depending on the host broadcaster, a number of different technologies are used during an umpire or player review, including instant replays, Hawk-Eye, Hot Spot and Real Time Snickometer.[56][57] Hawk-Eye is also used in tennis to challenge umpiring decisions.[58][59]

Sports and education

Research suggests that sports have the capacity to connect youth to positive adult role models and provide positive development opportunities, as well as promote the learning and application of life skills.[60][61] In recent years the use of sport to reduce crime, as well as to prevent violent extremism and radicalization, has become more widespread, especially as a tool to improve self-esteem, enhance social bonds and provide participants with a feeling of purpose.[61]

There is no high-quality evidence that shows the effectiveness of interventions to increase sports participation of the community in sports such as mass media campaigns, educational sessions, and policy changes.[62] There is also no high-quality studies that investigate the effect of such interventions in promoting healthy behaviour change in the community.[63]

Politics

Benito Mussolini used the 1934 FIFA World Cup, which was held in Italy, to showcase Fascist Italy.[64][65] Adolf Hitler also used the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin, and the 1936 Winter Olympics held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, to promote the Nazi ideology of the superiority of the Aryan race, and inferiority of the Jews and other «undesirables».[65][66] Germany used the Olympics to give off a peaceful image while secretly preparing for war.[67]

When apartheid was the official policy in South Africa, many sports people, particularly in rugby union, adopted the conscientious approach that they should not appear in competitive sports there. Some feel this was an effective contribution to the eventual demolition of the policy of apartheid, others feel that it may have prolonged and reinforced its worst effects.[68]

In the history of Ireland, Gaelic sports were connected with cultural nationalism. Until the mid-20th century a person could have been banned from playing Gaelic football, hurling, or other sports administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) if she/he played or supported Association football, or other games seen to be of British origin. Until recently the GAA continued to ban the playing of football and rugby union at Gaelic venues. This ban, also known as Rule 42,[69] is still enforced, but was modified to allow football and rugby to be played in Croke Park while Lansdowne Road was redeveloped into Aviva Stadium. Until recently, under Rule 21, the GAA also banned members of the British security forces and members of the RUC from playing Gaelic games, but the advent of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 led to the eventual removal of the ban.

Nationalism is often evident in the pursuit of sport, or in its reporting: people compete in national teams, or commentators and audiences can adopt a partisan view. On occasion, such tensions can lead to violent confrontation among players or spectators within and beyond the sporting venue, as in the Football War. These trends are seen by many as contrary to the fundamental ethos of sport being carried on for its own sake and for the enjoyment of its participants.

Sport and politics collided in the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Masked men entered the hotel of the Israeli Olympic team and killed many of their men. This was known as the Munich massacre.

A study of US elections has shown that the result of sports events can affect the results. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that when the home team wins the game before the election, the incumbent candidates can increase their share of the vote by 1.5 percent. A loss had the opposite effect, and the effect is greater for higher-profile teams or unexpected wins and losses.[70] Also, when Washington Redskins win their final game before an election, then the incumbent President is more likely to win, and if the Redskins lose, then the opposition candidate is more likely to win; this has become known as the Redskins Rule.[71][72]

As a means of controlling and subduing populations

Étienne de La Boétie, in his essay Discourse on Voluntary Servitude describes athletic spectacles as means for tyrants to control their subjects by distracting them.

Do not imagine that there is any bird more easily caught by decoy, nor any fish sooner fixed on the hook by wormy bait, than are all these poor fools neatly tricked into servitude by the slightest feather passed, so to speak, before their mouths. Truly it is a marvellous thing that they let themselves be caught so quickly at the slightest tickling of their fancy. Plays, farces, spectacles, gladiators, strange beasts, medals, pictures, and other such opiates, these were for ancient peoples the bait toward slavery, the price of their liberty, the instruments of tyranny. By these practices and enticements the ancient dictators so successfully lulled their subjects under the yoke, that the stupefied peoples, fascinated by the pastimes and vain pleasures flashed before their eyes, learned subservience as naïvely, but not so creditably, as little children learn to read by looking at bright picture books.[73]

During the British rule of Bengal, British and European sports began to supplant traditional Bengali sports, resulting in a loss of native culture.[74]

Religious views

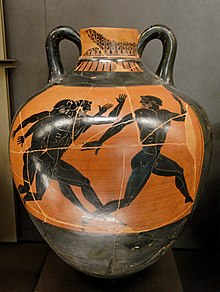

The foot race was one of the events dedicated to Zeus. Panathenaic amphora, Kleophrades painter, circa 500 BC, Louvre museum.

Sport was an important form of worship in Ancient Greek religion. The ancient Olympic Games were held in honour of the head deity, Zeus, and featured various forms of religious dedication to him and other gods.[75] As many Greeks travelled to see the games, this combination of religion and sport also served as a way of uniting them.

The practice of athletic competitions has been criticised by some Christian thinkers as a form of idolatry, in which «human beings extol themselves, adore themselves, sacrifice themselves and reward themselves.»[76] Sports are seen by these critics as a manifestation of «collective pride» and «national self-deification» in which feats of human power are idolised at the expense of divine worship.[76]

Tertullian condemns the athletic performances of his day, insisting «the entire apparatus of the shows is based upon idolatry.»[77] The shows, says Tertullian, excite passions foreign to the calm temperament cultivated by the Christian:

God has enjoined us to deal calmly, gently, quietly, and peacefully with the Holy Spirit, because these things are alone in keeping with the goodness of His nature, with His tenderness and sensitiveness. … Well, how shall this be made to accord with the shows? For the show always leads to spiritual agitation, since where there is pleasure, there is keenness of feeling giving pleasure its zest; and where there is keenness of feeling, there is rivalry giving in turn its zest to that. Then, too, where you have rivalry, you have rage, bitterness, wrath and grief, with all bad things which flow from them – the whole entirely out of keeping with the religion of Christ.[78]

Christian clerics in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement oppose the viewing of or participation in professional sports, believing that professional sports leagues profane the Sabbath as in the modern era, certain associations hold games on the Lord’s Day.[79] They also criticise professional sports for its fostering of a commitment that competes with a Christian’s primary commitment to God in opposition to 1 Corinthians 7:35, what they perceive to be a lack of modesty in the players’ and cheerleaders’ uniforms (which are not in conformity with the Methodistic doctrine of outward holiness), its association with violence in opposition to Hebrews 7:26, what they perceive to be the extensive use of profanity among many players that contravenes Colossians 3:8–10, and the frequent presence of gambling, as well as alcohol and other drugs at sporting events, which go against a commitment to teetotalism.[79]

Popularity

Popularity in 2018 of major sports by size of fan base:[7]

| Rank | Sport | Estimated Global Following | Sphere of Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Association football (Soccer) | 4 billion | Globally |

| 2 | Cricket | 2.5 billion | primarily UK and Commonwealth, South Asia (Indian subcontinent) |

| 3 | Hockey (Ice and Field) | 2 billion | Europe, North America, Africa, Asia and Australia |

| 4 | Tennis | 1 billion | Globally |

| 5 | Volleyball (along with Beach Volleyball) | 900 million | Americas, Europe, Asia, Oceania |

| 6 | Table tennis | 875 million | Mainly East Asia |

| 7 | Basketball | 825 million | Globally |

| 8 | Baseball | 500 million | primarily United States, Caribbean and East Asia |

| 9 | Rugby (League and Union) | 475 million | primarily UK, Ireland, France, Italy, Oceania, South Africa, Argentina, and Japan. |

| 10 | Golf | 450 million | primarily Western Europe, East Asia and North America |

See also

- Outline of sports

- List of sports

- List of sportspeople

- List of sports attendance figures

- List of professional sports leagues

- New Media and Sports

Related topics

- Athletic sports

- Animals in sport

- Combat sport

- Disabled sports

- Electronic sports

- Fan (person)

- Handedness#Advantage in sports

- International sport

- Lawn game

- Mind sport

- Motor sports

- Multi-sport events

- National sport

- Nationalism and sports

- Olympic Games

- Paralympic Games

- Physical education

- Physical fitness

- Spalding Athletic Library

- Sponsorship

- Sport in film

- Sport psychology

- Sports club

- Sports coaching

- Sports commentator

- Sports entertainment

- Sports equipment

- Sports fan

- Sports governing body

- Sports injuries

- Sports league attendances

- Sports marketing

- Sports nutrition

- Sports terms named after people

- Sports trainer

- Sportsperson

- Sportswear

- Sunday sporting events

- Team sport

- Underwater sports

- Women’s sports

- Water sports

- Winter sport

Sources

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Strengthening the rule of law through education: a guide for policymakers, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO. To learn how to add open license text to Wikipedia articles, please see this how-to page. For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

References

- ^ a b c d e «Definition of sport». SportAccord. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Council of Europe. «The European sport charter». Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ «List of Summer and Winter Olympic Sports and Events». The Olympic Movement. 14 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ «World Mind Games». SportAccord. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012.

- ^ «Members». SportAccord. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012.

- ^ «Women in sport: Game, sex and match». The Economist. 7 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ a b «The Most Popular Sports in the World». www.worldatlas.com. World Atlas. 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «sport (n.)». Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Springfield, MA: G&C Merriam Company. 1967. p. 2206.

- ^ Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1995. ISBN 978-0-618-25414-9.

- ^ «Judicial review of ‘sport’ or ‘game’ decision begins». BBC News. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Council of Europe, Revised European Sports Charter Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine (2001)

- ^ Front, Rebecca (17 July 2011). «A little competition». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Scrimgeour, Heidi (17 June 2011). «Why parents hate school sports day». ParentDish. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ «Sports History in China». Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ «Mr Ahmed D. Touny (EGY), IOC Member». Archived from the original on 29 October 2006.

- ^ «Persian warriors». Archived from the original on 26 March 2007.

- ^ «kabaddi | sport | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ «Ancient Olympic Games». 30 July 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ Sport and the Law: Historical and Cultural Intersections, p. 111, Sarah K. Fields (2014)[ISBN missing]|

- ^ «Sportsmanship». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ Fish, Joel; Magee, Susan (2003). 101 Ways to Be a Terrific Sports Parent. Fireside. p. 168.

- ^ Lacey, David (10 November 2007). «It takes a bad loser to become a good winner». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ «Debut of Baseball5 at Youth Olympic Games postponed as next YOG shifted from 2022 to 2026». World Baseball Softball Confederation. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ «Gym class injuries up 150% between 1997 and 2007» Archived 2 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Time, 4 August 2009

- ^ Gregory, Sean (24 August 2017). «How Kids’ Sports Became a $15 Billion Industry». Time. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ «135 mn saw World Cup final: TAM». Hindustan Times. 10 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ a b «Super Bowl XLIX was the most-viewed television program in U.S. history». Yahoo Sports. 2 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Super Bowl most watched television show in US history». Financial Times. 2 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Super Bowl Sunday is a Worldwide American Football Holiday». American Football International Review. 1 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Markovits, Andrei; Rensmann, Lars (2010). Gaming the World: How Sports Are Reshaping Global Politics and Culture. p. 94. ISBN 9781400834662. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «The White Paper on Sport». European Commission. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ Freedman, Jonah. «Fortunate 50 2011». Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Eassom, Simon (1994). Critical Reflections on Olympic Ideology. Ontario: The Centre for Olympic Studies. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-0-7714-1697-2.

- ^ a b «Olympic Athletes». Info Please. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ «What changed the Olympics forever». CNN. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ «Olympic boxing must remain amateur despite moves to turn it professional states Warren». Inside the Games. 13 August 2011. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Grasso, John (2013). Historical Dictionary of Boxing. ISBN 9780810878679. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ «Olympic Wrestling Is Important for Pro Wrestling and Its Fans». Bleacher Report. 14 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Boys’ Life. Boy Scouts of America, Inc. August 1988. p. 24. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ «Gaining Steam in Sports Technology». Slice of MIT. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ «Hi-tech suits banned from January». BBC Sport. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Wong, Kristina (4 January 2010). «Full Body Swimsuit Now Banned for Professional Swimmers». ABC News. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ FIFA (2012). «Testing Manual» (PDF). FIFA Quality Programme for Goal Line Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2012.

- ^ «IFAB makes three unanimous historic decisions». FIFA. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ «Goal-line technology set up ahead of FIFA World Cup». FIFA. 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ «Hawk-Eye confirmed as goal-line technology provider for Canada 2015». FIFA. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ «Goal-line technology: Premier League votes in favour for 2013–14». BBC. 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ «Bundesliga approves Hawk-Eye goal-line technology for new season». Carlyle Observer. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ «NFL approves rule to change replay process». Business Insider. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Television Match Official – when can they rule». Rugby World. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Cleary, Mick (20 August 2012). «New rules for Television Match Officials will not make game boring to watch, insist rugby chiefs». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b «The role of cricket umpires». BBC Sport. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Cricket Technology». Top End Sports. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Controversial DRS to be used in 2015 ICC World Cup». Zee News. 29 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «Hawkeye, Realtime Snicko for World Cup». ESPNcricinfo. 7 February 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «3 Top reasons why ICC did not use ‘Hotspot’ as part of DRS». Rediff. Rediff cricket. 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Newman, Paul (23 June 2007). «Hawk-Eye makes history thanks to rare British success story at Wimbledon». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ «Hawk-Eye challenge rules unified». BBC News. 19 March 2008. Archived from the original on 23 March 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ Fraser-Thomas, J.L., Cote, J., Deakin, J. 2005. Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 19-40.

- ^ a b UNESCO (2019). Strengthening the rule of law through education: a guide for policymakers. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100308-0. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Priest N, Armstrong R, Doyle J, Waters E (16 July 2008). «Interventions Implemented Through Sporting Organisations for Increasing Participation in Sport». Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004812. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004812.pub3. PMID 18646112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Priest N, Armstrong R, Doyle J, Water E (16 July 2008). «Policy Interventions Implemented Through Sporting Organisations for Promoting Healthy Behaviour Change». Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (3): CD004809. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004809.pub3. PMC 6464902. PMID 18646111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kuhn, Gabriel (2011). Soccer Vs. the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics. p. 28. ISBN 9781604860535. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b Blamires, Cyprian (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. pp. 630–632. ISBN 9781576079409. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Saxena, Anurag (2001). The Sociology of Sport and Physical Education. ISBN 9781618204684. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Kulttuurivihkot 1 2009 Berliinin olympialaiset 1936 Poliittisen viattomuuden menetys Jouko Jokisalo 28–29(in Finnish)

- ^ Merrett, Christopher (2005). «Sport and apartheid». History Compass. 3: **. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2005.00165.x.

- ^ Fulton, Gareth; Bairner, Alan (2007). «Sport, Space and National Identity in Ireland: The GAA, Croke Park and Rule 42». Space & Policy. 11 (1): 55–74. doi:10.1080/13562570701406592. S2CID 143213001.

- ^ Tyler Cowen; Kevin Grier (24 October 2012). «Will Ohio State’s Football Team Decide Who Wins the White House?». Slate. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Mike Jones (3 November 2012). «Will Redskins Rule again determine outcome of presidential election?». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ «‘Redskins Rule’: MNF’s Hirdt on intersection of football & politics». ESPN Front Row. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Étienne de La Boétie, Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1549), Part 2

- ^ Disappearance of Traditional games by the imitation of Colonial Culture through the Historical parameters of Cultural Colonialism Archived 26 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Md Abu Nasim https://dergipark.org.tr/ Archived 1 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gardinier, Norman E., ‘The Olympic Festival’ in Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals, London: MacMillan, 1910, p.195

- ^ a b Sports and Christianity: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Nick J. Watson, ed. (Routledge: 2013), p. 178.

- ^ Tertullian, De spectaculis, Chapter 4.

- ^ De spectaculis Chapter 15.

- ^ a b Handel, Paul S. (2020). Reasons Why Organized Sports Are Not Pleasing to God. Immanuel Missionary Church. p. 4.

Sources

- European Commission (2007), The White Paper on Sport.

- Council of Europe (2001), The European sport charter.

Further reading

- The Meaning of Sports by Michael Mandel (PublicAffairs, ISBN 1-58648-252-1).

- Journal of the Philosophy of Sport

- Sullivan, George. The Complete Sports Dictionary. New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1979. 199 p. ISBN 0-590-05731-6