1. Length & structure

Theoretically speaking a

sentence can be of any length. Unable to specify the upper limit of

sentence length we definitely know its lower mark to be one word.

One-word sentence

possesses a very strong emphatic impact for its only word obtains

both the word & the sentence stress e.g. Silence. In the night.

Abrupt changes from short

sentences to long ones & went back again create a very strong

effect of tension for they serve to arrange to a nervous, uneven

rhythm of an utterance. There is no direct correlation between the

length & the structure of the sentence. Short sentences may be

structured complicated while the long ones on the contrary may have

only one subject predicate pair.

Inversion

is a syntactical stylistic device based on violation of the

traditional word order of the sentence, which does not alter the

meaning of the sentence only giving it an additional logical impact

or emotional colouring. When the inversion deals with the

displacement of the predicate, it is complete

inversion, when it

deals with the displacement of the secondary members, it is partial

inversion.

Rhetorical question Is

a synt. SD based on a statement expressed in an interrogative from.

As distinct from an ordinary question which is asked to find some

information RQ does not require any answer, it serves the purpose of

calling the reader’s attention to a particular point of writing or

speech. e.g. What is this life, if full of care We have no time to

stay & stare?

Syntactical

stylistic devices dealing with completeness

Ellipses

is a deliberate

omission of at least one member of the sentence. E.g. I went to

London as one goes to exile, she – to NYork.

Break

in the narration is

a SD which consists in breaking the narration for rhetorical effect.

(threat, hesitation) E.g. Just come home, or I’ll …

Apokoinu

is the omission

of the pronominal (adverbial) connection which creates a blend of the

main & subordinate clauses so that the predicate or the object of

the 1st

clause is simultaneously used as a subject of the 2nd

clause.

E.g. Here is a gentleman

wants to know you (‘who’ is omitted). He was the man killed that

deer.

SD

dealing with arrangement of the sentence.

Parallelism

(parallel constructions)

-Purely syntactical type of repetition a syntactical device based on

the use of the similar synt. pattern in 2 or more sentence s or

clauses. Parallel constructions (PC) may be partial or complete.

Partial P

arrangement is the repetition of the structure of some parts of

successive sentences or clauses. Complete

P arrangement

represents identity of structures throughout the corresponding

sentences. Chiasmus(or reserved

P) is a synt. SD based on the repetition of a synt. pattern with a

reserved word order.

e.g.

He loved & was loved by everybody (active/passive voice)

Repetition (sd) is reiteration of the same word, word combination, phrase for 2 or more times. Several types:

simple

repetition

– is the R of one & the same member of a sentence without any

strict regularity;

anaphora

– is the R of the beginning of some successive sentences of

clauses: a…, a…, a…;

epiphora

– is the R of the end of some successive sentences of clauses: …a,

…a, …a;

Framing

– is the R of the beginning of the in the end thus forming the

frame for the non-repeated part of the sentence. e.g. Nothing ever

happed in that little town, left behind by the advance of

civilization, nothing. The function of framing is to elucidate the

notion mentioned at the beginning of the sentence a..a;

catch

(anadiplosis)

–(…a, a…) is the R of the end of the clause or sentence is the

beginning of the following one. E.g. he was shaken, shaken &

embitted;

chain

(…a, a…b, b…c, c…) presents several successive catch

repetitions. E.g. A smile would come into his face. Smile extends

into laughter, the laughter into roar & the roar became general.

The main function of chain R is to develop logical reasoning;

successive

R:

…a, a, a… – is the stream of closely following each other

reiterated units. E.g. On her father’s being groundlessly suspected

she felt sure. Sure. Sure This is the most emphatic type of R which

signifies the pick of emotions of the speaker.

Detachment

is a syntactical stylistic device consisting in separating a

secondary part of a sentence with the aim of emphasizing it. e.g. She

rose up, pale & with fury in her eyes.

Parenthesis—

sentence, phrase or word, which is inserted in a longer passage

without being gram.ly connected with it, usually marked off by

brackets, dashes or commas.e.g. He came-just imagine what he looked

like- & said..

Suspense

is a deliberate postponement of the completing of the sentence.

SD

based on various types of connection

Asyndeton

is connection between parts of sentence without any conjunctions.

Polysyndeton

is a syntactical stylistic device based on repeated use of

conjunctions in close connection.

e.g.

The heaviest rain & snow & hale & sleet.

Attachment

is a syntactical stylistic device based on the deliberate separation

of the second part of the utterance from the first one by a full

stop.

Соседние файлы в папке Gosy

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

English is a beautiful language, and one of its many perks is the one-word sentences. One-word sentences — as the name suggests is a sentence with a single word, and which makes total sense.

One word sentences can be used in different forms. It could be in form of a question such as “Why?” It could be in form of a command such as “Stop!” Furthermore, it could be used as a declarative such as “Me.” Also, a one-word sentence could be used to show location, for example, “here.” It could also be used as nominatives e.g. “David.”

Actually, most of the words in English can be turned into one-word sentences. All that matters is the context in which they are used. In a sentence, there is usually a noun, and a verb. In a one-word sentence, the subject and the action of the sentence is implied in the single word, and this is why to understand one-word sentences, one has to understand the context in which the word is being used.

Saying only a little at all times is a skill most people want to learn; knowing when to use one-word sentences can help tremendously. However, you cannot use one-word sentences all the time so as robotic or come off as rude.

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

- Help: This signifies a call for help.

- Hurry: Used to ask someone to do something faster

- Begin: Used to signify the beginning of a planned event.

Basically, the 5 Wh-question words — where, when, why, who and what? can also stand as one-word sentences.

By Bizhan Romani

Dr. Bizhan Romani has a PhD in medical virology. When it comes to writing an article about science and research, he is one of our best writers. He is also an expert in blogging about writing styles, proofreading methods, and literature.

What does a conjunction do?Where is a conjunction used?What is a conjunction? Here we have answers to all these questions! Conjunctions, one of the English parts of speech, act as linkers to join different parts of a sentence. Without conjunctions, the expression of the complex ideas will seem odd as you will have to use…

Introduction An adverb is a word that modifies a sentence, verb, or adjective. An adverb can be a word or simply an expression that can even change prepositions, and clauses. An adverb usually ends only- but some are the same as their adjectives counterparts. Adverbs express the time, place, frequency, and level of certainty. The…

What is a noun?What are all types of nouns?How is a noun used in a sentence? A noun is referred to any word that names something. This could be a person, place, thing, or idea. Nouns play different roles in sentences. A noun could be a subject, direct object, indirect object, subject complement, object complement,…

What is a pronoun?How is a pronoun used in a sentence?What are all types of pronouns? A pronoun is classified as a transition word and a subcategory of a noun that functions in every capacity that a noun will function. They can function as both subjects and objects in a sentence. Let’s see the origin…

In the English language, sentence construction is quite imperative to understanding. A sentence can be a sequence, set or conglomerate of words that is complete in itself as it typically contains a subject, verb, object and predicate. However, this sentence regardless of its intent, would be chaotic if not constructed properly. Proper sentence construction helps…

Слайд 2Stylistic Devices

Phono-graphical

Lexical

Syntactical

Lexico-sytactical

Слайд 3PHONO-GRAPHICAL LEVEL

Phonetic means

Craphon

Graphical means

Слайд 4Phonetic means

Onomatopoeia — the use of words whose sounds imitate those

of the signified object or action

e.g “hiss», «bowwow», «murmur», «bump», «grumble“, “growl”

Слайд 5

Alliteration –the repetition of consonants

e.g. He swallowed the hint with

a gulp and a gasp and a grin.

Assonance -the repetition of similar vowels

e.g. brain drain

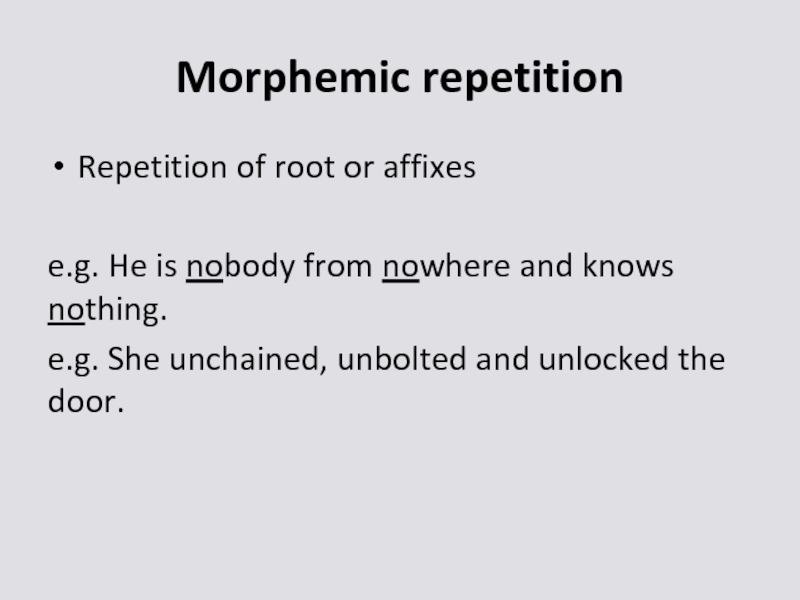

Слайд 6Morphemic repetition

Repetition of root or affixes

e.g. He is nobody from nowhere

and knows nothing.

e.g. She unchained, unbolted and unlocked the door.

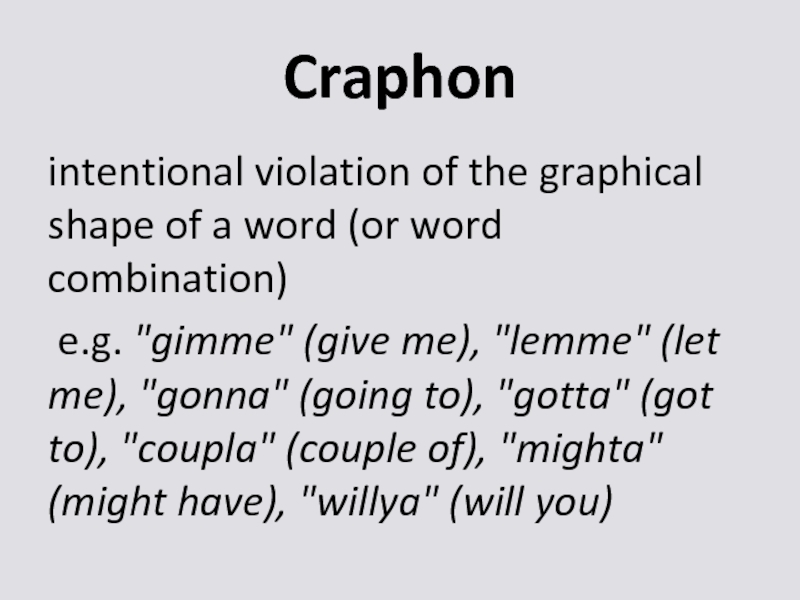

Слайд 7Craphon

intentional violation of the graphical shape of a word (or word

combination)

e.g. «gimme» (give me), «lemme» (let me), «gonna» (going to), «gotta» (got to), «coupla» (couple of), «mighta» (might have), «willya» (will you)

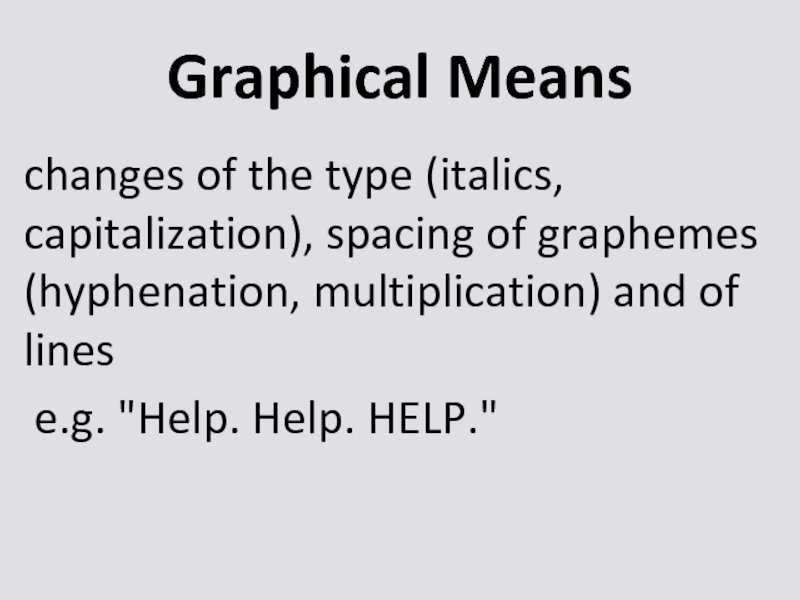

Слайд 8Graphical Means

changes of the type (italics, capitalization), spacing of graphemes (hyphenation,

multiplication) and of lines

e.g. «Help. Help. HELP.»

Слайд 9Lexical Stylistic Devices

Metaphor

Metonymy.

Synecdoche

Play on Words.

Irony

Epithet

Hyperbole

Understatement

Oxymoron

Слайд 10Metaphor

transference of names based on the associated likeness between two objects

e.g.

He is a walking dictionary.

trite, hackneyed, stale («leg of a table» )

fresh, original, genuine

sustained (prolonged) metaphor (through the text)

Слайд 11Personification

Qualities of animate objects are attributed to inanimate objects

e.g. The sun

is smiling at us.

e.g. He turned over another page of his life

Слайд 12Metonymy.

The whole object is named by its part

e.g. There is

no news from Downing Street, 10 yet.

Слайд 13Synecdoche

type of metonymy: is based on the relations between a part

and the whole

e.g. I need more hands down here.

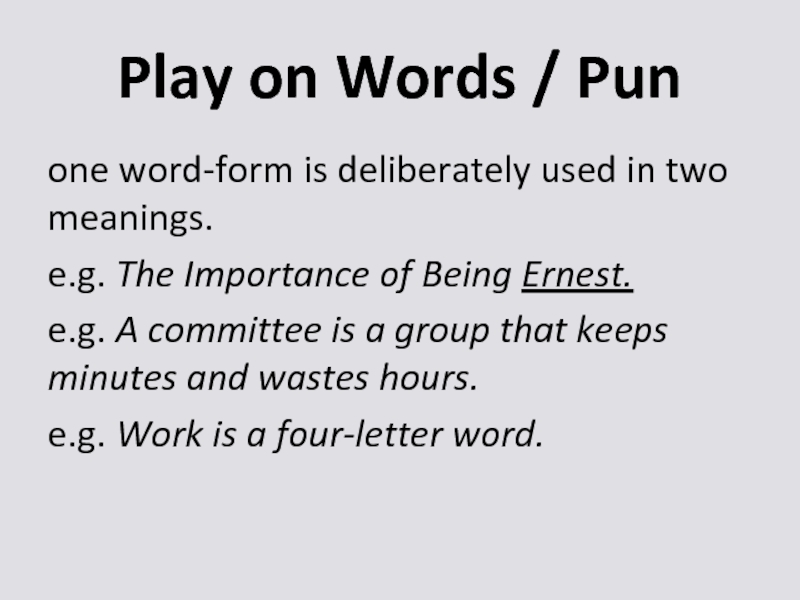

Слайд 14Play on Words / Pun

one word-form is deliberately used in

two meanings.

e.g. The Importance of Being Ernest.

e.g. A committee is a group that keeps minutes and wastes hours.

e.g. Work is a four-letter word.

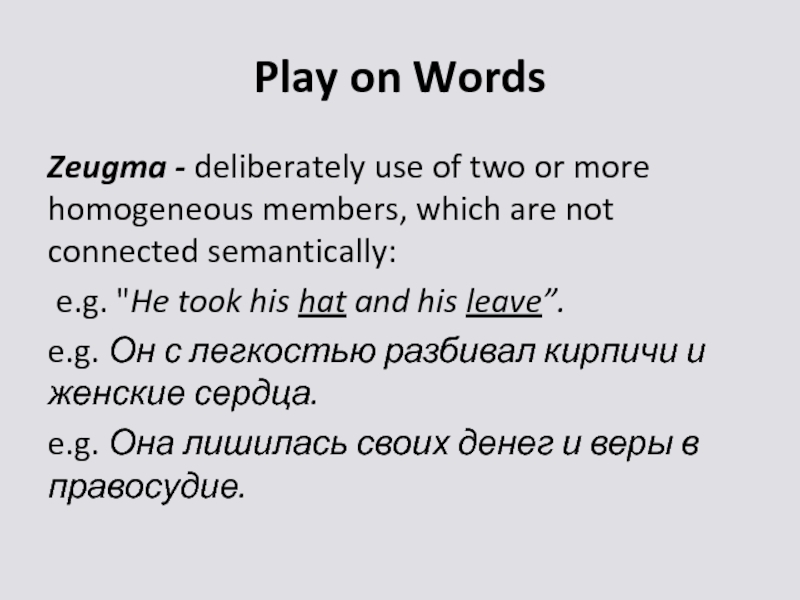

Слайд 15Play on Words

Zeugma — deliberately use of two or more homogeneous

members, which are not connected semantically:

e.g. «He took his hat and his leave”.

e.g. Он с легкостью разбивал кирпичи и женские сердца.

e.g. Она лишилась своих денег и веры в правосудие.

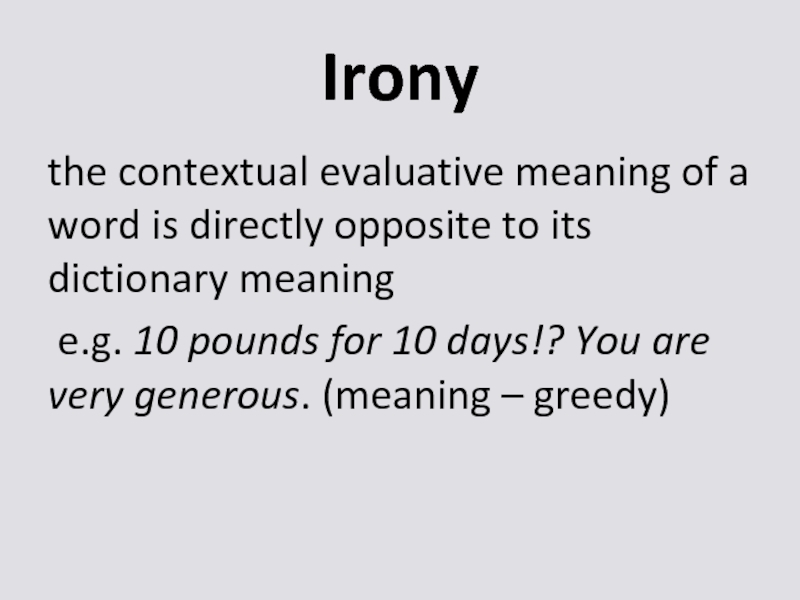

Слайд 16Irony

the contextual evaluative meaning of a word is directly opposite to

its dictionary meaning

e.g. 10 pounds for 10 days!? You are very generous. (meaning – greedy)

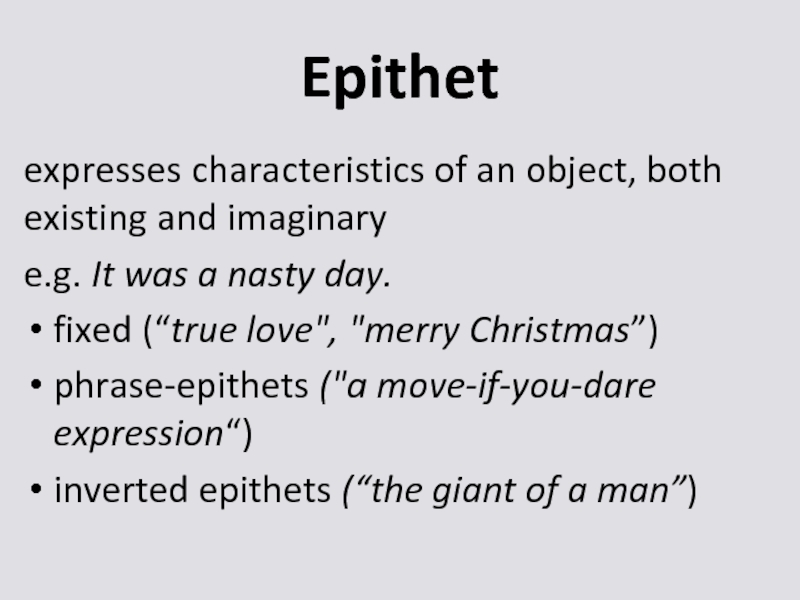

Слайд 17Epithet

expresses characteristics of an object, both existing and imaginary

e.g. It was

a nasty day.

fixed (“true love», «merry Christmas”)

phrase-epithets («a move-if-you-dare expression“)

inverted epithets (“the giant of a man”)

Слайд 18Antonomasia

a proper name is used instead of a common noun or

vice versa

e.g. Dr. Rest, Dr. Diet and Dr. Fresh Air

e.g. Now let me introduce you — that’s Mr. What’s-his-name, you remember him, don’t you?

Слайд 19Hyperbole

deliberate exaggeration

e.g. «I have told it to you a thousand times“.

Слайд 20Understatement

the opposite of hyperbole

e.g. My mother is not very well at

the moment. (the woman is at hospital with a stroke.)

Слайд 21Oxymoron

combination of two semantically contradictory notions

e.g. «awfully pretty“

e.g. There were some

bookcases of superbly unreadable books

Слайд 22SYNTACTICAL LEVEL

Sentence length and structure

Syntactical SDs

Слайд 23Sentence Length

One-Word Sentences – a very strong emphatic impact

e.g. The neon

lights in the heart of the city flashed on and off. On and off. On. Off. On. Off. Continuously.

Слайд 24Asyndeton

Deliberate omission of conjunctions:

e.g. Secretly, after the nightfall, he visited the

home of the Prime Minister. He examined it from top to bottom. He measured al the doors an windows. He took up the flooring. He inspected the plumbing. He examined the furniture. He found nothing.

Слайд 25Polysyndeton

Excessive use of conjunctions:

e.g. Everybody you love will be dead –

mum and little Sue and Charlie and Mrs. Furrow – unless you make the right decision, now.

Слайд 26Syntactical SDs

rhetorical question

e.g. Who would like to go to the contaminated

area?

Слайд 27Inversion

e.g. And here emerged another problem

e.g. Ten days and ten nights

did they stay on hunger strike.

Слайд 28REPETITION

anaphora: the beginning of two or more successive sentences (clauses) is

repeated — a…, a…, a…

e.g. Mother was a cook, mother was a teacher, mother was a referee, mother was a mother.

epiphora: the end of successive sentences (clauses) is repeated -…a, …a, …a.

e.g. Kate was there, Mick was there, Mrs Harley was there – and none of them could explain what they saw.

Слайд 29

framing: the beginning of the sentence is repeated in the end,

thus forming the «frame» for the non-repeated part of the sentence (utterance) — a… a.

e.g. Evil breeds evil.

Слайд 30

catch repetition (anadiplosis). the end of one clause (sentence) is repeated

in the beginning of the following one -…a, a….

chain repetition presents several successive anadiploses -…a, a…b, b…c, c

e.g. Human curiosity brought about science. Science led to progress. Progress is expected to enhance our wellbeing.

Слайд 31

ordinary repetition has no definite place in the sentence and the

repeated unit occurs in various positions — …a, …a…, a..

Слайд 32

successive repetition is a string of closely following each other reiterated

units — …a, a, a…

e.g. Say it, say it, say it now.

Слайд 33Parallel constructions

Repetition of the same grammar structure

e.g. Mother cooks dinner. Father

watches TV. Children bother mother and father at the same time.

Слайд 34Chiasmus

if the first sentence (clause) has a direct word order —

SPO, the second one will have it inverted — OPS.

e.g. He loved girls, but girls didn’t love him.

e.g.Если гора не идет к Магомету, то Магомет идет к горе.

Слайд 35Detachment

a stylistic device based on singling out a secondary member

of the sentence with the help of punctuation (intonation)

e.g. She was crazy about you. In the beginning.

Слайд 36Apokoinu constructions

a blend of the main and the subordinate clauses

so that the predicative or the object of the first one is simultaneously used as the subject of the second one.

impression of clumsiness of speech

e.g. «He was the man killed that deer.»

Слайд 37Break (aposiopesis)

imitating spontaneous oral speech

e.g. «Good intentions, but…“

«It depends“.

Слайд 38Lexico-Syntactical Stylistic Devices

Antithesis

Climax

Anticlimax

Simile

Litotes

Periphrasis

Слайд 39Antithesis

the two parts of an antithesis must be semantically opposite to

each other

e.g. «If we don’t know who gains by his death we do know who loses by it.»

e.g. Don’t use big words. They mean so little.

Слайд 40Climax

each next word combination (clause, sentence) is logically more important or

emotionally stronger

e.g. «No tree, no shrub, no blade of grass that was not owned.»

e.g. «She felt better, immensely better.»

Слайд 41Anticlimax

Climax which is suddenly interrupted by an unexpected turn of the

thought or ends in complete semantic reversal of the emphasized idea:

e.g. Women have a wonderful instinct about things. They can discover everything except the obvious.

Many paradoxes are based on anticlimax

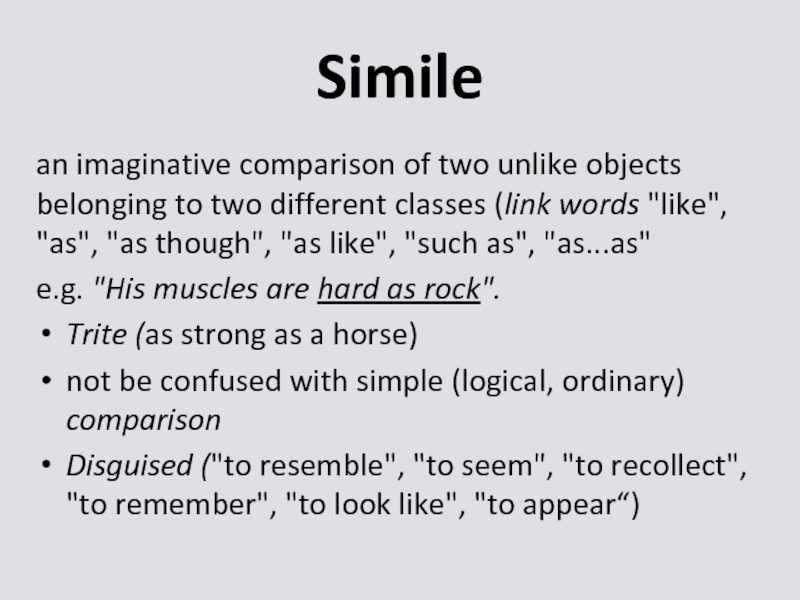

Слайд 42Simile

an imaginative comparison of two unlike objects belonging to two different

classes (link words «like», «as», «as though», «as like», «such as», «as…as»

e.g. «His muscles are hard as rock».

Trite (as strong as a horse)

not be confused with simple (logical, ordinary) comparison

Disguised («to resemble», «to seem», «to recollect», «to remember», «to look like», «to appear“)

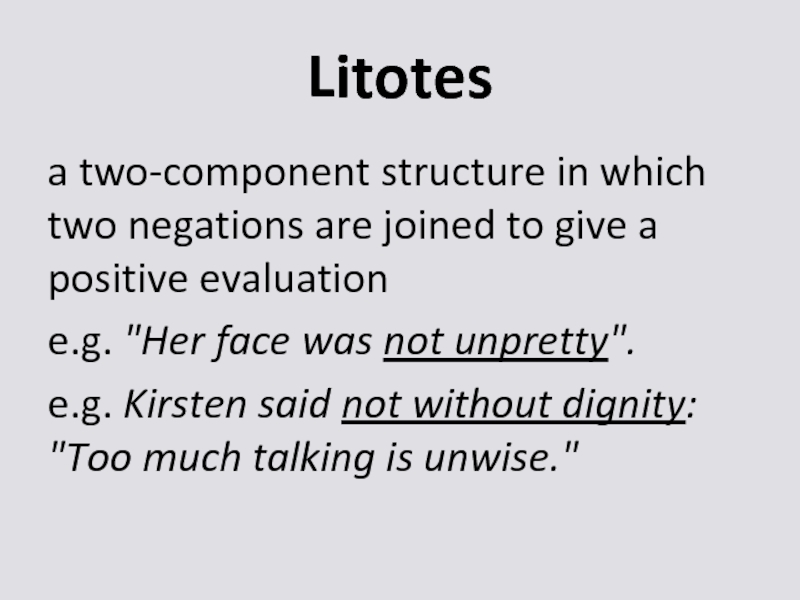

Слайд 43Litotes

a two-component structure in which two negations are joined to give

a positive evaluation

e.g. «Her face was not unpretty».

e.g. Kirsten said not without dignity: «Too much talking is unwise.»

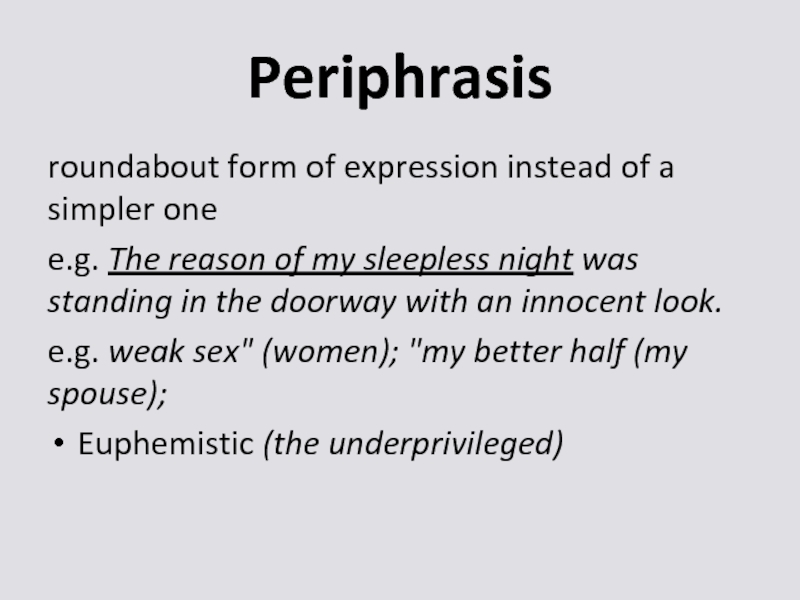

Слайд 44Periphrasis

roundabout form of expression instead of a simpler one

e.g. The reason

of my sleepless night was standing in the doorway with an innocent look.

e.g. weak sex» (women); «my better half (my spouse);

Euphemistic (the underprivileged)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A sentence word (also called a one-word sentence) is a single word that forms a full sentence.

Henry Sweet described sentence words as ‘an area under one’s control’ and gave words such as «Come!», «John!», «Alas!», «Yes.» and «No.» as examples of sentence words.[1] The Dutch linguist J. M. Hoogvliet described sentence words as «volzinwoorden».[2] They were also noted in 1891 by Georg von der Gabelentz, whose observations were extensively elaborated by Hoogvliet in 1903; he does not list «Yes.» and «No.» as sentence words. Wegener called sentence words «Wortsätze».[3]

Single-word utterances and child language acquisition[edit]

One of the predominant questions concerning children and language acquisition deals with the relation between the perception and the production of a child’s word usage. It is difficult to understand what a child understands about the words that they are using and what the desired outcome or goal of the utterance should be.[4]

Holophrases are defined as a «single-word utterance which is used by a child to express more than one meaning usually attributed to that single word by adults.»[5] The holophrastic hypothesis argues that children use single words to refer to different meanings in the same way an adult would represent those meanings by using an entire sentence or phrase. There are two opposing hypotheses as to whether holophrases are structural or functional in children. The two hypotheses are outlined below.

Structural holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

The structural version argues that children’s “single word utterances are implicit expressions of syntactic and semantic structural relations.” There are three arguments used to account for the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The comprehension argument, the temporal proximity argument, and the progressive acquisition argument.[5]

- The comprehension argument is based on the idea that comprehension in children is more advanced than production throughout language acquisition. Structuralists believe that children have knowledge of sentence structure but they are unable to express it due to a limited lexicon. For example, saying “Ball!” could mean “Throw me the ball” which would have the structural relation of the subject of the verb. However, studies attempting to show the extent to which children understand syntactic structural relation, particularly during the one-word stage, end up showing that children “are capable of extracting the lexical information from a multi-word command,” and that they “can respond correctly to a multi-word command if that command is unambiguous at the lexical level.”[5] This argument therefore does not provide evidence needed to prove the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis because it fails to prove that children in the single-word stage understand structural relations such as the subject of a sentence and the object of a verb.[5]

- The temporal proximity argument is based on the observation that children produce utterances referring to the same thing, close to each other. Even the utterances aren’t connected, it is argued that children know about the linguistic relationships between the words, but cannot connect them yet.[5] An example is laid out below:

→ Child: «Daddy» (holding pair of fathers pants)

- → Child

-

-

- «Bai» (‘bai’ is the term the child uses for any item of clothing)

-

The usage of ‘Daddy’ and ‘Bai’ used in close proximity are seen to represent a child’s knowledge of linguistic relations; in this case the relation is the ‘possessive’.[6] This argument is seen as having insufficient evidence as it is possible that the child is only switching from one way to conceptualize pants to another. It is also pointed out that if the child had knowledge of linguistic relationships between words, then the child would combine the words together, instead of using them separately.[5]

- Finally, the last argument in support of structuralism is the progressive acquisition argument. This argument states that children progressively gain new structural relations throughout the holophrastic stage. This is also unsupported by the research.[5]

Functional holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

Functionalists doubt whether children really have structural knowledge, and argue that children rely on gestures to carry meaning (such as declarative, interrogative, exclamative or vocative). There are three arguments used to account for the functional version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The intonation argument, the gesture argument, and the predication argument.[5]

- The intonation argument suggests that children use intonation in a contrastive way. Researchers have established through longitudinal studies that children have knowledge of intonation and can use it to communicate a specific function across utterances.[7][8][9] Compare the two examples below:

→ Child: «Ball.» (flat intonation) — Can mean «That is a ball.»

-

-

- → Child: «Ball?» (rising inflection) — Can mean «Where is the ball?»

-

- However, it has been noted by Lois Bloom that there is no evidence that a child intends for intonation to be contrastive, it is only that adults are able to interpret it as such.[10] Martyn Barrett contrasts this with a longitudinal study performed by him, where he illustrated the acquisition of a rising inflection by a girl who was a year and a half old. Although she started out using intonation randomly, upon acquisition of the term «What’s that» she began to use rising intonation exclusively for questions, suggesting knowledge of its contrastive usage.[11]

- The gesture argument establishes that some children use gesture instead of intonation contrastively. Compare the two examples laid out below:

→ Child: «Milk.» (points at milk jug) — could mean “That is milk.”

-

-

- → Child: «Milk.» (open-handed gesture while reaching for a glass of milk) — could mean “I want milk.”

-

- Each use of the word ‘milk’ in the examples above could have no use of intonation, or a random use of intonation, and so meaning is reliant on gesture. Anne Carter observed, however, that in the early stages of word acquisition children use gestures primarily to communicate, with words merely serving to intensify the message.[12] As children move onto multi-word speech, content and context are also used alongside gesture.

- The predication argument suggests that there are three distinct functions of single word utterances, ‘Conative’, which is used to direct the behaviour of oneself or others; ‘Expressive’, which is used to express emotion; and referential, which is used to refer to things.[13] The idea is that holophrases are predications, which is defined as the relationship between a subject and a predicate. Although McNeill originally intended this argument to support the structural hypothesis, Barrett believes that it more accurately supports the functional hypothesis, as McNeill fails to provide evidence that predication is expressed in holophrases.[5]

Single-word utterances and adult usage[edit]

While children use sentence words as a default strategy due to lack of syntax and lexicon, adults tend to use sentence words in a more specialized way, generally in a specific context or to convey a certain meaning. Because of this distinction, single word utterances in children are called ‘holophrases’, while in adults, they are called ‘sentence words’. In both the child and adult use of sentence words, context is very important and relative to the word chosen, and the intended meaning.

Sentence word formation[edit]

Many sentence words have formed from the process of devaluation and semantic erosion. Various phrases in various languages have devolved into the words for «yes» and «no» (which can be found discussed in detail in yes and no), and these include expletive sentence words such as «Well!» and the French word «Ben!» (a parallel to «Bien!»).[14]

However, not all word sentences suffer from this loss of lexical meaning. A subset of sentence words, which Fonagy calls «nominal phrases», exist that retain their lexical meaning. These exist in Uralic languages, and are the remainders of an archaic syntax wherein there were no explicit markers for nouns and verbs. An example of this is the Hungarian language «Fecske!», which transliterates as «Swallow!», but which has to be idiomatically translated with multiple words «Look! A swallow!» for rendering the proper meaning of the original, which to a native Hungarian speaker is neither elliptical nor emphatic. Such nominal phrase word sentences occur in English as well, particularly in telegraphese or as the rote questions that are posed to fill in form data (e.g. «Name?», «Age?»).[14]

Sentence word syntax[edit]

A sentence word involves invisible covert syntax and visible overt syntax. The invisible section or «covert» is the syntax that is removed in order to form a one word sentence. The visible section or «overt» is the syntax that still remains in a sentence word.[15] Within sentence word syntax there are 4 different clause-types: Declarative (making a declaration), exclamative (making an exclamation), vocative (relating to a noun), and imperative (a command).

| Overt | Covert | |

|---|---|---|

| Declarative | ‘That is excellent!’

|

‘Excellent!’

|

| Exclamative | ‘That was rude!’

|

‘Rude!’

|

| Vocative | ‘There is Mary!’

|

‘Mary!’

|

| Imperative | ‘You should leave!’

|

‘Leave!’

|

| Locative | ‘The chair is here.’

|

‘Here.’

|

| Interrogative | ‘Where is it?’

|

‘Where?’

|

The words in bold above demonstrate that in the overt syntax structures, there are words that can be omitted in order to form a covert sentence word.

Distribution cross-linguistically[edit]

Other languages use sentence words as well.

- In Japanese, a holophrastic or single-word sentence is meant to carry the least amount of information as syntactically possible, while intonation becomes the primary carrier of meaning.[16] For example, a person saying the Japanese word e.g. «はい» (/haɪ/) = ‘yes’ on a high level pitch would command attention. Pronouncing the same word using a mid tone, could represent an answer to a roll-call. Finally, pronouncing this word with a low pitch could signify acquiescence: acceptance of something reluctantly.[16]

| High tone pitch | Mid tone pitch | Low tone pitch |

|---|---|---|

| Command attention | Represent an answer to roll-call | Signify acquiescence acceptance of something reluctantly |

- Modern Hebrew also exhibits examples of sentence words in its language, e.g. «.חַם» (/χam/) = «It is hot.» or «.קַר» (/kar/) = «It is cold.».

References[edit]

- ^ Henry Sweet (1900). «Adverbs». A New English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 127. ISBN 978-1-4021-5375-4.

- ^ Jan Noordegraaf (2001). «J. M. Hoogvliet as a teacher and theoretician». In Marcel Bax; C. Jan-Wouter Zwart; A. J. van Essen (eds.). Reflections on Language and Language Learning. John Benjamins B.V. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-272-2584-9.

- ^ Giorgio Graffi (2001). 200 Years of Syntax. John Benjamins B.V. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-58811-052-7.

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2009). Language Development. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barrett, Martyn, D. (1982). «The holophrastic hypothesis: Conceptual and empirical issues». Cognition. 11: 47–76. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(82)90004-x.

- ^ Rodgon, M.M. (1976). Single word usage, cognitive development and the beginnings of combinatorial speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dore, J. (1975). «Holophrases, speech acts and language universals». Journal of Child Language. 2: 21–40. doi:10.1017/s0305000900000878.

- ^ Leopold, W.F. (1939). Speech Development of a Bilingual Child: A Linguist’s Record. Volume 1: Vocabulary growth in the first two years. Evanston, ill: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ Von Raffler Engel, W. (1973). «The development from sound to phoneme in child language». Studies of Child Language Development.

- ^ Bloom, Lois (1973). One word at a time: The use of single word utterances before syntax. The Hague: Mouton.

- ^ Barrett, M.D (1979). Semantic Development during the Single-Word Stage of Language Acquisition (Unpublished doctoral thesis).

- ^ Carter, Anne :L. (1979). «Prespeech meaning relations an outline of one infant’s sensorimotor morpheme development». Language Acquisition: 71–92.

- ^ David, McNeill (1970). The Acquisition of Language: The Study of Developmental Psycholinguistics.

- ^ a b Ivan Fonagy (2001). Languages Within Language. John Benjamins B.V. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-927232-82-1.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: a generative introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 496.

- ^ a b Hirst, D. (1998). Intonation systems: a survey of twenty languages. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 372.