Coordinates: 30°N 70°E / 30°N 70°E

|

Islamic Republic of Pakistan

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag State emblem |

|

| Motto: Īmān, Ittihād, Nazam ایمان، اتحاد، نظم «Faith, Unity, Discipline»[2] |

|

| Anthem: Qaumī Tarānah قَومی ترانہ «The National Anthem» |

|

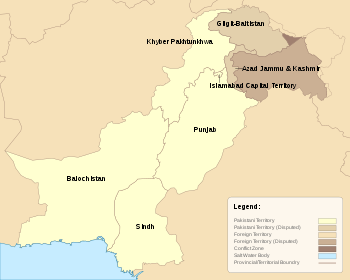

Land controlled by Pakistan shown in dark green; land claimed but not controlled shown in light green |

|

| Capital | Islamabad 33°41′30″N 73°03′00″E / 33.69167°N 73.05000°E |

| Largest city | Karachi 24°51′36″N 67°00′36″E / 24.86000°N 67.01000°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Recognised national languages | Urdu[3] |

| Recognised regional languages | Provincial languages

|

| Other languages | Over 77 languages[4] |

| Ethnic groups

(2017[a]) |

|

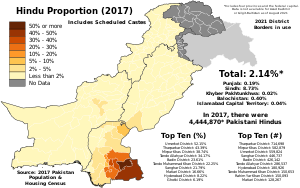

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Pakistani |

| Government | Federal Islamic parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Arif Alvi |

|

• Prime Minister |

Shehbaz Sharif |

|

• Chairman of the Senate |

Sadiq Sanjrani |

|

• Speaker of the National Assembly |

Raja Pervaiz Ashraf |

|

• Chief Justice |

Umar Ata Bandial |

| Legislature | Parliament |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

National Assembly |

| Independence

from the United Kingdom |

|

|

• Declaration |

23 March 1940 |

|

• Independence |

14 August 1947 |

|

• Dominion status terminated |

23 March 1956 |

|

• Eastern territory withdrawn |

26 March 1971 |

|

• Current constitution |

14 August 1973 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

881,913 km2 (340,509 sq mi)[b][9] (33rd) |

|

• Water (%) |

2.86 |

| Population | |

|

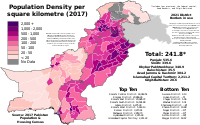

• 2022 estimate |

242,923,845[10] (5th) |

|

• Density |

244.4/km2 (633.0/sq mi) (56th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | low · 161st |

| Currency | Pakistani rupee (₨) (PKR) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| DST is not observed | |

| Date format |

|

| Driving side | left[15] |

| Calling code | +92 |

| ISO 3166 code | PK |

| Internet TLD |

|

Pakistan (Urdu: پاکِستان [ˈpaːkɪstaːn]),[d] officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (اِسلامی

جمہوریہ پاکِستان), is a country in South Asia. It is the world’s fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world’s second-largest Muslim population just behind Indonesia.[16] Pakistan is the 33rd-largest country in the world by area and the second-largest in South Asia, spanning 881,913 square kilometres (340,509 square miles). It has a 1,046-kilometre (650-mile) coastline along the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman in the south, and is bordered by India to the east, Afghanistan to the west, Iran to the southwest, and China to the northeast. It is separated narrowly from Tajikistan by Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor in the north, and also shares a maritime border with Oman. Islamabad is the nation’s capital, while Karachi is its largest city and financial centre.

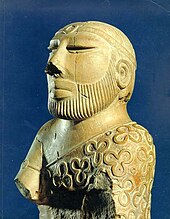

Pakistan is the site of several ancient cultures, including the Paleolithic Soanian culture, the Neolithic site of Mehrgarh,[17] the Indus Valley civilisation of the Bronze Age, the most extensive of the civilisations of the Afro-Eurasia,[18][19] and the ancient Gandhara civilisation.[20] The regions that comprise the modern state of Pakistan were the realm of multiple empires and dynasties, including the Achaemenid, the Maurya, the Kushan, the Gupta;[21] the Umayyad Caliphate in its southern regions, the Samma, the Hindu Shahis, the Shah Miris, the Ghaznavids, the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughals,[22] and most recently, the British Raj from 1858 to 1947.

Spurred by the Pakistan Movement, which sought a homeland for the Muslims of British India, and election victories in 1946 by the All-India Muslim League, Pakistan gained independence in 1947 after the Partition of the British Indian Empire, which awarded separate statehood to its Muslim-majority regions and was accompanied by an unparalleled mass migration and loss of life.[23] Initially a Dominion of the British Commonwealth, Pakistan officially drafted its constitution in 1956, and emerged as a declared Islamic republic. In 1971, the exclave of East Pakistan seceded as the new country of Bangladesh after a nine-month-long civil war. In the following four decades, Pakistan has been ruled by governments whose descriptions, although complex, commonly alternated between civilian and military, democratic and authoritarian, relatively secular and Islamist.[24] Pakistan elected a civilian government in 2008, and in 2010 adopted a parliamentary system with periodic elections.[25]

Pakistan is a middle power nation,[26][27][28][29][30][31] and has the world’s sixth-largest standing armed forces. It is a declared nuclear-weapons state, and is ranked amongst the emerging and growth-leading economies,[32] with a large and rapidly-growing middle class.[33] Pakistan’s political history since independence has been characterised by periods of significant economic and military growth as well as those of political and economic instability. It is an ethnically and linguistically diverse country, with similarly diverse geography and wildlife. The country continues to face challenges, including poverty, illiteracy, corruption and terrorism.[34] Pakistan is a member of the United Nations, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the Commonwealth of Nations, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, and the Islamic Military Counter-Terrorism Coalition, and is designated as a major non-NATO ally by the United States.

Etymology

The name Pakistan was coined by Choudhry Rahmat Ali, a Pakistan Movement activist, who in January 1933 first published it in a pamphlet Now or Never, using it as an acronym.[35] Rahmat Ali explained: «It is composed of letters taken from the names of all our homelands, Indian and Asian, Panjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Sindh, and Baluchistan.» He added that «Pakistan is both a Persian and Urdu word… It means the land of the Paks, the spiritually pure and clean.»[36] Etymologists note that پاک pāk, is ‘pure’ in Persian and Pashto[37] and the Persian suffix ـستان -stan means ‘land’ or ‘place of’.[38][39][40][41]

Rahmat Ali’s concept of Pakistan only related to the north-west area of the Indian subcontinent. He also proposed the name «Banglastan» for the Muslim areas of Bengal and «Osmanistan» for Hyderabad State, as well as a political federation between the three.[42][43]

History

Indus Valley Civilization

Some of the earliest ancient human civilisations in South Asia originated from areas encompassing present-day Pakistan.[44] The earliest known inhabitants in the region were Soanian during the Lower Paleolithic, of whom stone tools have been found in the Soan Valley of Punjab.[45] The Indus region, which covers most of present day Pakistan, was the site of several successive ancient cultures including the Neolithic Mehrgarh[46] and the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation[47][48] (2,800–1,800 BCE) at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.[49]

Vedic Period

The Vedic period (1500–500 BCE) was characterised by an Indo-Aryan culture; during this period the Vedas, the oldest scriptures associated with Hinduism, were composed, and this culture later became well established in the region.[50] Multan was an important Hindu pilgrimage centre.[51] The Vedic civilisation flourished in the ancient Gandhāran city of Takṣaśilā, now Taxila in the Punjab, which was founded around 1000 BCE.[52][46]

Classical Period

The western regions of Pakistan became part of Achaemenid Empire around 519 BCE. In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the region by defeating various local rulers, most notably, the King Porus, at Jhelum.[53] It was followed by the Maurya Empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya and extended by Ashoka the Great, until 185 BCE. The Indo-Greek Kingdom founded by Demetrius of Bactria (180–165 BCE) included Gandhara and Punjab and reached its greatest extent under Menander (165–150 BCE), prospering the Greco-Buddhist culture in the region.[46][54] Taxila had one of the earliest universities and centres of higher education in the world, which was established during the late Vedic period in the 6th century BCE.[55][56] The school consisted of several monasteries without large dormitories or lecture halls where the religious instruction was provided on an individualistic basis.[56] The ancient university was documented by the invading forces of Alexander the Great and was also recorded by Chinese pilgrims in the 4th or 5th century CE.[57]

At its zenith, the Rai Dynasty (489–632 CE) ruled Sindh and the surrounding territories.[58]

Islamic conquest

The Arab conqueror Muhammad ibn Qasim conquered Sindh in 711 CE.[59][60] The Pakistan government’s official chronology claims this as the time when the foundation of Pakistan was laid[59][61] but the concept of Pakistan arrived in the 19th century. The Early Medieval period (642–1219 CE) witnessed the spread of Islam in the region. During this period, Sufi missionaries played a pivotal role in converting a majority of the regional Buddhist and Hindu population to Islam.[62] Upon the defeat of the Turk and Hindu Shahi dynasties which governed the Kabul Valley, Gandhara (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkwa), and western Punjab in the 7th to 11th centuries CE, several successive Muslim empires ruled over the region, including the Ghaznavid Empire (975–1187 CE), the Ghorid Kingdom, and the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE). The Lodi dynasty, the last of the Delhi Sultanate, was replaced by the Mughal Empire (1526–1857 CE).

The Mughals introduced Persian literature and high culture, establishing the roots of Indo-Persian culture in the region.[63] In the region of modern-day Pakistan, key cities during the Mughal period were Lahore and Thatta,[64] both of which were chosen as the site of impressive Mughal buildings.[65] In the early 16th century, the region remained under the Mughal Empire.[66]

In the 18th century, the slow disintegration of the Mughal Empire was hastened by the emergence of the rival powers of the Maratha Confederacy and later the Sikh Empire, as well as invasions by Nader Shah from Iran in 1739 and the Durrani Empire of Afghanistan in 1759. The growing political power of the British in Bengal had not yet reached the territories of modern Pakistan.

Colonial period

None of the territory of modern Pakistan was ruled by the British, or other European powers, until 1839, when Karachi, then a small fishing village with a mud fort guarding the harbour, was taken, and held as an enclave with a port and military base for the First Afghan War that soon followed. The rest of Sindh was taken in 1843, and in the following decades, first the East India Company, and then after the post-Sepoy Mutiny (1857–1858) direct rule of Queen Victoria of the British Empire, took over most of the country partly through wars, and also treaties. The main wars were that against the Baloch Talpur dynasty, ended by the Battle of Miani (1843) in Sindh, the Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845–1849) and the Anglo-Afghan Wars (1839–1919). By 1893, all modern Pakistan was part of the British Indian Empire, and remained so until independence in 1947.

Under the British, modern Pakistan was mostly divided into the Sind Division, Punjab Province, and the Baluchistan Agency. There were various princely states, of which the largest was Bahawalpur.

A rebellion in 1857 called the Sepoy mutiny of Bengal was the region’s major armed struggle against the British.[67] Divergence in the relationship between Hinduism and Islam created a major rift in British India that led to motivated religious violence in British India.[68] The language controversy further escalated the tensions between Hindus and Muslims.[69] The Hindu renaissance witnessed an awakening of intellectualism in traditional Hinduism and saw the emergence of more assertive influence in the social and political spheres in British India.[70] A Muslim intellectual movement, founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan to counter the Hindu renaissance, envisioned as well as advocated for the two-nation theory[71] and led to the creation of the All-India Muslim League in 1906. In contrast to the Indian National Congress’s anti-British efforts, the Muslim League was a pro-British movement whose political program inherited the British values that would shape Pakistan’s future civil society.[72] The largely non-violent independence struggle led by the Indian Congress engaged millions of protesters in mass campaigns of civil disobedience in the 1920s and 1930s against the British Empire.[73][74]

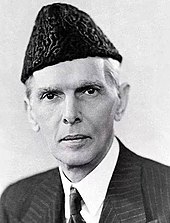

The Muslim League slowly rose to mass popularity in the 1930s amid fears of under-representation and neglect by the British of the Indian Muslims in politics. In his presidential address of 29 December 1930, Allama Iqbal called for «the amalgamation of North-West Muslim-majority Indian states» consisting of Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind, and Baluchistan.[75] The perceived neglect of Muslim interests by Congress led British provincial governments during the period of 1937–39 convinced Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan to espouse the two-nation theory and led the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution of 1940 presented by Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Haque, popularly known as the Pakistan Resolution.[71] In World War II, Jinnah and British-educated founding fathers in the Muslim League supported the United Kingdom’s war efforts, countering opposition against it whilst working towards Sir Syed’s vision.[76]

Pakistan Movement

The 1946 elections resulted in the Muslim League winning 90 percent of the seats reserved for Muslims. Thus, the 1946 election was effectively a plebiscite in which the Indian Muslims were to vote on the creation of Pakistan, a plebiscite won by the Muslim League. This victory was assisted by the support given to the Muslim League by the support of the landowners of Sindh and Punjab. The Indian National Congress, which initially denied the Muslim League’s claim of being the sole representative of Indian Muslims, was now forced to recognise the fact.[77] The British had no alternative except to take Jinnah’s views into account as he had emerged as the sole spokesperson of the entirety of British India’s Muslims. However, the British did not want colonial India to be partitioned, and in one last effort to prevent it, they devised the Cabinet Mission plan.[78]

As the cabinet mission failed, the British government announced its intention to end the British Rule in 1946–47.[79] Nationalists in British India—including Jawaharlal Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad of Congress, Jinnah of the All-India Muslim League, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs—agreed to the proposed terms of transfer of power and independence in June 1947 with the Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten of Burma.[80] As the United Kingdom agreed to the partitioning of India in 1947, the modern state of Pakistan was established on 14 August 1947 (27th of Ramadan in 1366 of the Islamic Calendar), amalgamating the Muslim-majority eastern and northwestern regions of British India.[74] It comprised the provinces of Balochistan, East Bengal, the North-West Frontier Province, West Punjab, and Sindh.[71][80]

In the riots that accompanied the partition in Punjab Province, it is believed that between 200,000 and 2,000,000[81] people were killed in what some have described as a retributive genocide between the religions[82] while 50,000 Muslim women were abducted and raped by Hindu and Sikh men, 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women also experienced the same fate at the hands of Muslims.[83] Around 6.5 million Muslims moved from India to West Pakistan and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs moved from West Pakistan to India.[84] It was the largest mass migration in human history.[85] A subsequent dispute over the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir eventually sparked the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948.[86]

Independence and modern Pakistan

Queen Elizabeth II was the last monarch of independent Pakistan, before it became a republic in 1956.

After independence in 1947, Jinnah, the President of the Muslim League, became the nation’s first Governor-General as well as the first President-Speaker of the Parliament, but he died of tuberculosis on 11 September 1948.[87] Meanwhile, Pakistan’s founding fathers agreed to appoint Liaquat Ali Khan, the secretary-general of the party, the nation’s first Prime Minister. From 1947 to 1956, Pakistan was a monarchy within the Commonwealth of Nations, and had two monarchs before it became a republic.[88]

The creation of Pakistan was never fully accepted by many British leaders, among them Lord Mountbatten.[89] Mountbatten clearly expressed his lack of support and faith in the Muslim League’s idea of Pakistan.[90] Jinnah refused Mountbatten’s offer to serve as Governor-General of Pakistan.[91] When Mountbatten was asked by Collins and Lapierre if he would have sabotaged Pakistan had he known that Jinnah was dying of tuberculosis, he replied ‘most probably’.[92]

The American CIA film on Pakistan, made in 1950, examines the history and geography of Pakistan.

«You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the State.»

—Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s first speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan[93]

Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, a respected Deobandi alim (scholar) who occupied the position of Shaykh al-Islam in Pakistan in 1949, and Maulana Mawdudi of Jamaat-i-Islami played a pivotal role in the demand for an Islamic constitution. Mawdudi demanded that the Constituent Assembly make an explicit declaration affirming the «supreme sovereignty of God» and the supremacy of the shariah in Pakistan.[94]

A significant result of the efforts of the Jamaat-i-Islami and the ulama was the passage of the Objectives Resolution in March 1949. The Objectives Resolution, which Liaquat Ali Khan called the second most important step in Pakistan’s history, declared that «sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to God Almighty alone and the authority which He has delegated to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him is a sacred trust». The Objectives Resolution has been incorporated as a preamble to the constitutions of 1956, 1962, and 1973.[95]

Democracy was stalled by the martial law that had been enforced by President Iskander Mirza, who was replaced by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army, General Ayub Khan. After adopting a presidential system in 1962, the country experienced exceptional growth until a second war with India in 1965 that led to an economic downturn and wide-scale public disapproval in 1967.[96][97] Consolidating control from Ayub Khan in 1969, President Yahya Khan had to deal with a devastating cyclone that caused 500,000 deaths in East Pakistan.[98]

In 1970 Pakistan held its first democratic elections since independence, meant to mark a transition from military rule to democracy, but after the East Pakistani Awami League won against the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), Yahya Khan and the military establishment refused to hand over power.[99][100] Operation Searchlight, a military crackdown on the Bengali nationalist movement, led to a declaration of independence and the waging of a war of liberation by the Bengali Mukti Bahini forces in East Pakistan,[100][101] which in West Pakistan was described as a civil war as opposed to a war of liberation.[102]

Independent researchers estimate that between 300,000 and 500,000 civilians died during this period while the Bangladesh government puts the number of dead at three million,[103] a figure that is now nearly universally regarded as excessively inflated.[104] Some academics such as Rudolph Rummel and Rounaq Jahan say both sides[105] committed genocide; others such as Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose believe there was no genocide.[106] In response to India’s support for the insurgency in East Pakistan, preemptive strikes on India by Pakistan’s air force, navy, and marines sparked a conventional war in 1971 that resulted in an Indian victory and East Pakistan gaining independence as Bangladesh.[100]

With Pakistan surrendering in the war, Yahya Khan was replaced by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as president; the country worked towards promulgating its constitution and putting the country on the road to democracy. Democratic rule resumed from 1972 to 1977—an era of self-consciousness, intellectual leftism, nationalism, and nationwide reconstruction.[107] In 1972 Pakistan embarked on an ambitious plan to develop its nuclear deterrence capability with the goal of preventing any foreign invasion; the country’s first nuclear power plant was inaugurated in that same year.[108][109] Accelerated in response to India’s first nuclear test in 1974, this crash program was completed in 1979.[109]

Democracy ended with a military coup in 1977 against the leftist PPP, which saw General Zia-ul-Haq become the president in 1978. From 1977 to 1988, President Zia’s corporatisation and economic Islamisation initiatives led to Pakistan becoming one of the fastest-growing economies in South Asia.[110] While building up the country’s nuclear program, increasing Islamisation,[111] and the rise of a homegrown conservative philosophy, Pakistan helped subsidise and distribute US resources to factions of the mujahideen against the USSR’s intervention in communist Afghanistan.[112] Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province became a base for the anti-Soviet Afghan fighters, with the province’s influential Deobandi ulama playing a significant role in encouraging and organising the ‘jihad’.[113]

President Zia died in a plane crash in 1988, and Benazir Bhutto, daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was elected as the country’s first female Prime Minister. The PPP was followed by conservative Pakistan Muslim League (N), and over the next decade the leaders of the two parties fought for power, alternating in office while the country’s situation worsened; economic indicators fell sharply, in contrast to the 1980s. This period is marked by prolonged stagflation, instability, corruption, nationalism, geopolitical rivalry with India, and the clash of left wing-right wing ideologies.[114] As PML (N) secured a supermajority in elections in 1997, Nawaz Sharif authorised nuclear testings (See:Chagai-I and Chagai-II), as a retaliation to the second nuclear tests ordered by India, led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in May 1998.[115]

Military tension between the two countries in the Kargil district led to the Kargil War of 1999, and turmoil in civic-military relations allowed General Pervez Musharraf to take over through a bloodless coup d’état.[116][117] Musharraf governed Pakistan as chief executive from 1999 to 2001 and as President from 2001 to 2008—a period of enlightenment, social liberalism, extensive economic reforms,[118] and direct involvement in the US-led war on terrorism. When the National Assembly historically completed its first full five-year term on 15 November 2007, the new elections were called by the Election Commission.[119]

After the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in 2007, the PPP secured the most votes in the elections of 2008, appointing party member Yousaf Raza Gillani as Prime Minister.[120] Threatened with impeachment, President Musharraf resigned on 18 August 2008, and was succeeded by Asif Ali Zardari.[121] Clashes with the judicature prompted Gillani’s disqualification from the Parliament and as the Prime Minister in June 2012.[122] By its own financial calculations, Pakistan’s involvement in the war on terrorism has cost up to $118 billion,[123] sixty thousand casualties and more than 1.8 million displaced civilians.[124] The general election held in 2013 saw the PML (N) almost achieve a supermajority, following which Nawaz Sharif was elected as the Prime Minister, returning to the post for the third time in fourteen years, in a democratic transition.[125] In 2018, Imran Khan (the chairman of PTI) won the 2018 Pakistan general election with 116 general seats and became the 22nd Prime Minister of Pakistan in election of National Assembly of Pakistan for Prime Minister by getting 176 votes against Shehbaz Sharif (the chairman of PML (N)) who got 96 votes.[126] In April 2022, Shehbaz Sharif was elected as Pakistan’s new prime minister, after Imran Khan lost a no-confidence vote in the parliament.[127]

Role of Islam

Pakistan is the only country to have been created in the name of Islam.[128] The idea of Pakistan, which had received overwhelming popular support among Muslims, especially those in the provinces of British India where Muslims were in a minority such as the United Provinces,[129] was articulated in terms of an Islamic state by the Muslim League leadership, the ulama (Islamic clergy) and Jinnah.[130] Jinnah had developed a close association with the ulama and upon his death was described by one such alim, Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, as the greatest Muslim after Aurangzeb and as someone who desired to unite the Muslims of the world under the banner of Islam.[131]

The Objectives Resolution in March 1949, which declared God as the sole sovereign over the entire universe, represented the first formal step to transform Pakistan into an Islamic state.[132][95] Muslim League leader Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman asserted that Pakistan could only truly become an Islamic state after bringing all believers of Islam into a single political unit.[133] Keith Callard, one of the earliest scholars on Pakistani politics, observed that Pakistanis believed in the essential unity of purpose and outlook in the Muslim world and assumed that Muslim from other countries would share their views on the relationship between religion and nationality.[134]

However, Pakistan’s pan-Islamist sentiments for a united Islamic bloc called Islamistan were not shared by other Muslim governments,[135] although Islamists such as the Grand Mufti of Palestine, Al-Haj Amin al-Husseini, and leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood, became drawn to the country. Pakistan’s desire for an international organization of Muslim countries was fulfilled in the 1970s when the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) was formed.[136]

The strongest opposition to the Islamist ideological paradigm being imposed on the state came from the Bengali Muslims of East Pakistan[137] whose educated class, according to a survey by social scientist Nasim Ahmad Jawed, preferred secularism and focused on ethnic identity unlike educated West Pakistanis who tended to prefer an Islamic identity.[138] The Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami considered Pakistan to be an Islamic state and believed Bengali nationalism to be unacceptable. In the 1971 conflict over East Pakistan, the Jamaat-e-Islami fought the Bengali nationalists on the Pakistan Army’s side.[139] The conflict concluded with East Pakistan seceding and the creation of independent Bangladesh.

After Pakistan’s first ever general elections, the 1973 Constitution was created by an elected Parliament.[140] The Constitution declared Pakistan an Islamic Republic and Islam as the state religion. It also stated that all laws would have to be brought into accordance with the injunctions of Islam as laid down in the Quran and Sunnah and that no law repugnant to such injunctions could be enacted.[141] The 1973 Constitution also created certain institutions such as the Shariat Court and the Council of Islamic Ideology to channel the interpretation and application of Islam.[142]

Pakistan’s leftist Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto faced vigorous opposition which coalesced into a movement united under the revivalist banner of Nizam-e-Mustafa («Rule of the Prophet»)[143] which aimed to establish an Islamic state based on Sharia laws. Bhutto agreed to some Islamist demands before being overthrown in a coup.[144]

In 1977, after taking power from Bhutto in a coup d’état, General Zia-ul-Haq, who came from a religious background,[145] committed himself to establishing an Islamic state and enforcing sharia law.[144] Zia established separate Shariat judicial courts[146] and court benches[147] to judge legal cases using Islamic doctrine.[148] Zia bolstered the influence of the ulama (Islamic clergy) and the Islamic parties.[148] Zia-ul-Haq forged a strong alliance between the military and Deobandi institutions[149] and even though most Barelvi ulama[150] and only a few Deobandi scholars had supported Pakistan’s creation, Islamic state politics came to be mostly in favour of Deobandi (and later Ahl-e-Hadith/Salafi) institutions instead of Barelvi.[151] Sectarian tensions increased with Zia’s anti-Shia policies.[152]

According to a Pew Research Center (PEW) opinion poll, a majority of Pakistanis support making Sharia the official law of the land.[153] In a survey of several Muslim countries, PEW also found that Pakistanis tend to identify with their religion more than their nationality in contrast to Muslims in other nations such as Egypt, Indonesia and Jordan.[154]

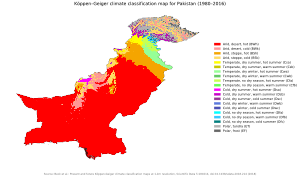

Geography, environment, and climate

The geography and climate of Pakistan are extremely diverse, and the country is home to a wide variety of wildlife.[155] Pakistan covers an area of 881,913 km2 (340,509 sq mi), approximately equal to the combined land areas of France and the United Kingdom. It is the 33rd-largest nation by total area, although this ranking varies depending on how the disputed territory of Kashmir is counted. Pakistan has a 1,046 km (650 mi) coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south[156] and land borders of 6,774 km (4,209 mi) in total: 2,430 km (1,510 mi) with Afghanistan, 523 km (325 mi) with China, 2,912 km (1,809 mi) with India and 909 km (565 mi) with Iran.[157] It shares a maritime border with Oman,[158] and is separated from Tajikistan by the cold, narrow Wakhan Corridor.[159] Pakistan occupies a geopolitically important location at the crossroads of South Asia, the Middle East, and Central Asia.[160]

Geologically, Pakistan is located in the Indus–Tsangpo Suture Zone and overlaps the Indian tectonic plate in its Sindh and Punjab provinces; Balochistan and most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are within the Eurasian plate, mainly on the Iranian plateau. Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir lie along the edge of the Indian plate and hence are prone to violent earthquakes. This region has the highest rates of seismicity and the largest earthquakes in the Himalaya region.[161] Ranging from the coastal areas of the south to the glaciated mountains of the north, Pakistan’s landscapes vary from plains to deserts, forests, hills, and plateaus.[162]

A satellite image showing the topography of Pakistan

Pakistan is divided into three major geographic areas: the northern highlands, the Indus River plain, and the Balochistan Plateau.[163] The northern highlands contain the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir mountain ranges (see mountains of Pakistan), which contain some of the world’s highest peaks, including five of the fourteen eight-thousanders (mountain peaks over 8,000 metres or 26,250 feet), which attract adventurers and mountaineers from all over the world, notably K2 (8,611 m or 28,251 ft) and Nanga Parbat (8,126 m or 26,660 ft).[164] The Balochistan Plateau lies in the west and the Thar Desert in the east. The 1,609 km (1,000 mi) Indus River and its tributaries flow through the country from the Kashmir region to the Arabian Sea. There is an expanse of alluvial plains along it in the Punjab and Sindh.[165]

The climate varies from tropical to temperate, with arid conditions in the coastal south. There is a monsoon season with frequent flooding due to heavy rainfall, and a dry season with significantly less rainfall or none at all. There are four distinct seasons in Pakistan: a cool, dry winter from December through February; a hot, dry spring from March through May; the summer rainy season, or southwest monsoon period, from June through September; and the retreating monsoon period of October and November.[71] Rainfall varies greatly from year to year, and patterns of alternate flooding and drought are common.[166]

Flora and fauna

The diversity of the landscape and climate in Pakistan allows a wide variety of trees and plants to flourish. The forests range from coniferous alpine and subalpine trees such as spruce, pine, and deodar cedar in the extreme northern mountains to deciduous trees in most of the country (for example, the mulberry-like shisham found in the Sulaiman Mountains), to palms such as coconut and date in the southern Punjab, southern Balochistan, and all of Sindh. The western hills are home to juniper, tamarisk, coarse grasses, and scrub plants. Mangrove forests form much of the coastal wetlands along the coast in the south.[167]

Markhor is the national animal of Pakistan.[168]

Coniferous forests are found at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 metres (3,300 to 13,100 feet) in most of the northern and northwestern highlands. In the xeric regions of Balochistan, date palm and Ephedra are common. In most of the Punjab and Sindh, the Indus plains support tropical and subtropical dry and moist broadleaf forest as well as tropical and xeric shrublands.[169] About 2.2% or 1,687,000 hectares (16,870 km2) of Pakistan was forested in 2010.[170]

The fauna of Pakistan also reflects the country’s varied climate. Around 668 bird species are found there,[171] including crows, sparrows, mynas, hawks, falcons, and eagles. Palas, Kohistan, has a significant population of western tragopan.[172] Many birds sighted in Pakistan are migratory, coming from Europe, Central Asia, and India.[173]

The southern plains are home to mongooses, small Indian civet, hares, the Asiatic jackal, the Indian pangolin, the jungle cat, and the desert cat. There are mugger crocodiles in the Indus, and wild boar, deer, porcupines, and small rodents in the surrounding areas. The sandy scrublands of central Pakistan are home to Asiatic jackals, striped hyenas, wildcats, and leopards.[174][175] The lack of vegetative cover, the severe climate, and the impact of grazing on the deserts have left wild animals in a precarious position. The chinkara is the only animal that can still be found in significant numbers in Cholistan. A small number of nilgai are found along the Pakistan–India border and in some parts of Cholistan.[174][176] A wide variety of animals live in the mountainous north, including the Marco Polo sheep, the urial (a subspecies of wild sheep), the markhor goat, the ibex goat, the Asian black bear, and the Himalayan brown bear.[174][177][178] Among the rare animals found in the area are the snow leopard[177] and the blind Indus river dolphin, of which there are believed to be about 1,100 remaining, protected at the Indus River Dolphin Reserve in Sindh.[177][179] In total, 174 mammals, 177 reptiles, 22 amphibians, 198 freshwater fish species and 5,000 species of invertebrates (including insects) have been recorded in Pakistan.[171]

The flora and fauna of Pakistan suffer from a number of problems. Pakistan has the second-highest rate of deforestation in the world, which, along with hunting and pollution, has had adverse effects on the ecosystem. It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.42/10, ranking it 41st globally out of 172 countries.[180] The government has established a large number of protected areas, wildlife sanctuaries, and game reserves to address these issues.[171]

Government and politics

Pakistan’s political experience is essentially related to the struggle of Muslims in the Indian subcontinent to regain the power they lost to British colonisation.[181] Pakistan is a democratic parliamentary federal republic, with Islam as the state religion.[7] The first constitution was adopted in 1956 but suspended by Ayub Khan in 1958, who replaced it with the second constitution in 1962.[74] A complete and comprehensive constitution was adopted in 1973, but it was suspended by Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 but reinstated in 1985. This constitution is the country’s most important document, laying the foundations of the current government.[157] The Pakistani military establishment has played an influential role in mainstream politics throughout Pakistan’s political history.[74] The periods 1958–1971, 1977–1988, and 1999–2008 saw military coups that resulted in the imposition of martial law and military commanders who governed as de facto presidents.[182] Today Pakistan has a multi-party parliamentary system with clear division of powers and checks and balances among the branches of government. The first successful democratic transition occurred in May 2013. Politics in Pakistan is centred on, and dominated by, a homegrown social philosophy comprising a blend of ideas from socialism, conservatism, and the third way. As of the general elections held in 2013, the three main political parties in the country are: the centre-right conservative Pakistan Muslim League-N; the centre-left socialist PPP; and the centrist and third-way Pakistan Movement for Justice (PTI). In 2010, constitutional changes reduced presidential powers and the role of the president became purely ceremonial. The role of prime minister strengthened.[183]

- Head of State: The President, who is elected by an Electoral College is the ceremonial head of the state and is the civilian commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Armed Forces (with the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee as principal military adviser), but military appointments and key confirmations in the armed forces are made by the Prime Minister after reviewing the reports on candidates’ merit and performance. Almost all appointed officers in the judicature, military, the chairman joint chiefs, joint staff, and legislature require the executive confirmation from the Prime Minister, whom the President must consult by law. However, the powers to pardon and grant clemency lie with the President of Pakistan.

- Legislative: The bicameral legislature comprises a 104-member Senate (upper house) and a 342-member National Assembly (lower house). Members of the National Assembly are elected through the first-past-the-post system under universal adult suffrage, representing electoral districts known as National Assembly constituencies. According to the constitution, the 70 seats reserved for women and religious minorities are allocated to the political parties according to their proportional representation. Senate members are elected by provincial legislators, with all the provinces having equal representation.

- Executive: The Prime Minister is usually the leader of the majority rule party or a coalition in the National Assembly— the lower house. The Prime Minister serves as the head of government and is designated to exercise as the country’s chief executive. The Prime Minister is responsible for appointing a cabinet consisting of ministers and advisers as well as running the government operations, taking and authorising executive decisions, appointments and recommendations of senior civil servants that require executive confirmation of the Prime Minister.

- Provincial governments: Each of the four provinces has a similar system of government, with a directly elected Provincial Assembly in which the leader of the largest party or coalition is elected Chief Minister. Chief Ministers oversee the provincial governments and head the provincial cabinet. It is common in Pakistan to have different ruling parties or coalitions in each of the provinces. The provincial bureaucracy is headed by the Chief Secretary, who is appointed by the Prime Minister. The provincial assemblies have power to make laws and approve the provincial budget which is commonly presented by the provincial finance minister every fiscal year. Provincial governors who are the ceremonial heads of the provinces are appointed by the President.[157]

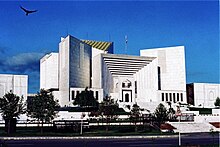

- Judicature: The judiciary of Pakistan is a hierarchical system with two classes of courts: the superior (or higher) judiciary and the subordinate (or lower) judiciary. The Chief Justice of Pakistan is the chief judge who oversees the judicature’s court system at all levels of command. The superior judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the Federal Shariat Court and five high courts, with the Supreme Court at the apex. The Constitution of Pakistan entrusts the superior judiciary with the obligation to preserve, protect and defend the constitution. Other regions of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan have separate court systems.

Foreign relations

Since Independence, Pakistan has attempted to balance its relations with foreign nations.[184] Pakistan is a strong ally of China, with both countries placing considerable importance on the maintenance of an extremely close and supportive special relationship.[185] It has also been a major non-NATO ally of the United States ever since the war against terrorism – a status achieved in 2004.[186] Pakistan’s foreign policy and geostrategy mainly focus on the economy and security against threats to its national identity and territorial integrity, and on the cultivation of close relations with other Muslim countries.[187]

The Kashmir conflict remains the major point of contention between Pakistan and India; three of their four wars were fought over this territory.[188] Due partly to difficulties in relations with its geopolitical rival India, Pakistan maintains close political relations with Turkey and Iran, and both countries have been a focal point in Pakistan’s foreign policy.[189] Saudi Arabia also maintains a respected position in Pakistan’s foreign policy.

A non-signatory party of the Treaty on Nuclear Non-Proliferation, Pakistan is an influential member of the IAEA.[190] In recent events, Pakistan has blocked an international treaty to limit fissile material, arguing that the «treaty would target Pakistan specifically».[191] In the 20th century, Pakistan’s nuclear deterrence program focused on countering India’s nuclear ambitions in the region, and nuclear tests by India eventually led Pakistan to reciprocate to maintain a geopolitical balance as becoming a nuclear power.[192] Currently, Pakistan maintains a policy of credible minimum deterrence, calling its program vital nuclear deterrence against foreign aggression.[193][194]

Located in the strategic and geopolitical corridor of the world’s major maritime oil supply lines and communication fibre optics, Pakistan has proximity to the natural resources of Central Asian countries.[195] Briefing on the country’s foreign policy in 2004, a Pakistani senator[clarification needed] reportedly explained: «Pakistan highlights sovereign equality of states, bilateralism, mutuality of interests, and non-interference in each other’s domestic affairs as the cardinal features of its foreign policy.»[196] Pakistan is an active member of the United Nations and has a Permanent Representative to represent Pakistan’s positions in international politics.[197] Pakistan has lobbied for the concept of «enlightened moderation» in the Muslim world.[198] Pakistan is also a member of Commonwealth of Nations,[199] the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO),[200] and the G20 developing nations.[201]

Due to ideological differences, Pakistan opposed the Soviet Union in the 1950s. During the Soviet–Afghan War in the 1980s, Pakistan was one of the closest allies of the United States.[196][202] Relations between Pakistan and Russia have greatly improved since 1999, and co-operation in various sectors has increased.[203] Pakistan has had an «on-and-off» relationship with the United States. A close ally of the United States during the Cold War, Pakistan’s relationship with the US soured in the 1990s when the latter imposed sanctions because of Pakistan’s secretive nuclear development.[204] Since 9/11, Pakistan has been a close ally of the US on the issue of counterterrorism in the regions of the Middle East and South Asia, with the US supporting Pakistan with aid money and weapons.[205][206] Initially, the US-led war on terrorism led to an improvement in the relationship, but it was strained by a divergence of interests and resulting mistrust during the war in Afghanistan and by issues related to terrorism.[207] The Pakistani intelligence agency, the ISI, was accused of supporting Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan.[208][209][210]

Pakistan does not have diplomatic relations with Israel;[211] nonetheless, some Israeli citizens have visited the country on tourist visas.[212] However, an exchange took place between the two countries using Turkey as a communication conduit.[213] Despite Pakistan being the only country in the world that has not established diplomatic relations with Armenia, an Armenian community still resides in Pakistan.[214] Pakistan had warm relations with Bangladesh, despite some initial strains in their relationship.

Relations with China

Pakistan Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai signing the Treaty of Friendship Between China and Pakistan. Pakistan is host to China’s largest embassy.[215]

Pakistan was one of the first countries to establish formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, and the relationship continues to be strong since China’s war with India in 1962, forming a special relationship.[216] From the 1960s to 1980s, Pakistan greatly helped China in reaching out to the world’s major countries and helped facilitate US President Richard Nixon’s state visit to China.[216] Despite the change of governments in Pakistan and fluctuations in the regional and global situation, China’s policy in Pakistan continues to be a dominant factor at all times.[216] In return, China is Pakistan’s largest trading partner, and economic co-operation has flourished, with substantial Chinese investment in Pakistan’s infrastructural expansion such as the Pakistani deep-water port at Gwadar. Friendly Sino-Pakistani relations reached new heights as both countries signed 51 agreements and Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) in 2015 for co-operation in different areas.[217] Both countries signed a Free Trade Agreement in the 2000s, and Pakistan continues to serve as China’s communication bridge to the Muslim world.[218] In 2016, China announced that it will set up an anti-terrorism alliance with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.[219]

Emphasis on relations with Muslim world

After Independence, Pakistan vigorously pursued bilateral relations with other Muslim countries[220] and made an active bid for leadership of the Muslim world, or at least for leadership in efforts to achieve unity.[221] The Ali brothers had sought to project Pakistan as the natural leader of the Islamic world, in part due to its large manpower and military strength.[222] A top-ranking Muslim League leader, Khaliquzzaman, declared that Pakistan would bring together all Muslim countries into Islamistan – a pan-Islamic entity.[223]

Such developments (along with Pakistan’s creation) did not get American approval, and British Prime Minister Clement Attlee voiced international opinion at the time by stating that he wished that India and Pakistan would re-unite.[224] Since most of the Arab world was undergoing a nationalist awakening at the time, there was little attraction to Pakistan’s Pan-Islamic aspirations.[225] Some of the Arab countries saw the ‘Islamistan’ project as a Pakistani attempt to dominate other Muslim states.[226]

Pakistan vigorously championed the right of self-determination for Muslims around the world. Pakistan’s efforts for the independence movements of Indonesia, Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Eritrea were significant and initially led to close ties between these countries and Pakistan.[227] However, Pakistan also masterminded an attack on the Afghan city of Jalalabad during the Afghan Civil War to establish an Islamic government there. Pakistan had wished to foment an ‘Islamic Revolution’ that would transcend national borders, covering Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia.[228]

On the other hand, Pakistan’s relations with Iran have been strained at times due to sectarian tensions.[229] Iran and Saudi Arabia used Pakistan as a battleground for their proxy sectarian war, and by the 1990s Pakistan’s support for the Sunni Taliban organisation in Afghanistan became a problem for Shia Iran, which opposed a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.[230] Tensions between Iran and Pakistan intensified in 1998 when Iran accused Pakistan of war crimes after Pakistani warplanes had bombarded Afghanistan’s last Shia stronghold in support of the Taliban.[231]

Pakistan is an influential and founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). Maintaining cultural, political, social, and economic relations with the Arab world and other countries in the Muslim world is a vital factor in Pakistan’s foreign policy.[232]

Administrative divisions

| Administrative division | Capital | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Quetta | 12,344,408 | |

| Lahore | 110,126,285 | |

| Karachi | 47,886,051 | |

| Peshawar | 40,525,047 | |

| Gilgit | 1,800,000 | |

| Muzaffarabad | 4,567,982 | |

| Islamabad Capital Territory | Islamabad | 2,851,868 |

A federal parliamentary republic state, Pakistan is a federation that comprises four provinces: Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh and Balochistan,[233] and three territories: Islamabad Capital Territory, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir. The Government of Pakistan exercises the de facto jurisdiction over the Frontier Regions and the western parts of the Kashmir Regions, which are organised into the separate political entities Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan (formerly Northern Areas). In 2009, the constitutional assignment (the Gilgit–Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order) awarded the Gilgit-Baltistan a semi-provincial status, giving it self-government.[234]

The local government system consists of a three-tier system of districts, tehsils, and union councils, with an elected body at each tier.[235] There are about 130 districts altogether, of which Azad Kashmir has ten[236] and Gilgit-Baltistan seven.[237]

Clickable map of the four provinces and three federal territories of Pakistan.

Law enforcement is carried out by a joint network of the intelligence community with jurisdiction limited to the relevant province or territory. The National Intelligence Directorate coordinates the information intelligence at both federal and provincial levels; including the FIA, IB, Motorway Police, and Civil Armed Forces such as the Pakistan Rangers and the Frontier Corps.[238]

Pakistan’s «premier» intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), was formed just within a year after the Independence of Pakistan in 1947.[239] ABC News Point in 2014 reported that the ISI was ranked as the top intelligence agency in the world[240] while Zee News reported the ISI as ranking fifth among the world’s most powerful intelligence agencies.[241]

The court system is organised as a hierarchy, with the Supreme Court at the apex, below which are high courts, Federal Shariat Courts (one in each province and one in the federal capital), district courts (one in each district), Judicial Magistrate Courts (in every town and city), Executive Magistrate Courts, and civil courts. The Penal code has limited jurisdiction in the Tribal Areas, where law is largely derived from tribal customs.[238][242]

Kashmir conflict

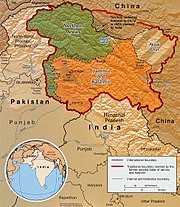

The areas shown in green are the Pakistani-controlled areas.

Kashmir, a Himalayan region situated at the northernmost point of the Indian subcontinent, was governed as an autonomous princely state known as Jammu and Kashmir in the British Raj prior to the Partition of India in August 1947. Following the independence of India and Pakistan post-partition, the region became the subject of a major territorial dispute that has hindered their bilateral relations. The two states have engaged each other in two large-scale wars over the region in 1947–1948 and 1965. India and Pakistan have also fought smaller-scale protracted conflicts over the region in 1984 and 1999.[188] Approximately 45.1% of the Kashmir region is controlled by India (administratively split into Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh), which also claims the entire territory of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that is not under its control.[188] India’s control over Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh as well as its claim to the rest of the region has likewise been contested by Pakistan, which controls approximately 38.2% of the region (administratively split into Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit−Baltistan) and claims all of the territory under Indian control.[188][243] Additionally, approximately 20% of the region has been controlled by China (known as Aksai Chin and the Shaksgam Valley) since the Sino-Indian War of 1962 and the Sino-Pakistani Agreement of 1963.[244] The Chinese-controlled areas of Kashmir remain subject to an Indian territorial claim, but are not claimed by Pakistan.

India claims the entire Kashmir region on the basis of the Instrument of Accession—a legal agreement with the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that was executed by Hari Singh, the maharaja of the state, who agreed to cede the entire area to newly-independent India.[245] Pakistan claims most of Kashmir on the basis of its Muslim-majority population and of its geography, the same principles that were applied for the creation of the two independent states.[246] India referred the dispute to the United Nations on 1 January 1948.[247] In a resolution passed in 1948, the UN’s General Assembly asked Pakistan to remove most of its military troops to set the conditions for the holding of a plebiscite. However, Pakistan failed to vacate the region and a ceasefire was reached in 1949 establishing a ceasefire line known as the Line of Control (LoC) that divided Kashmir between the two states as a de facto border.[248] India, fearful that the Muslim-majority populace of Kashmir would vote to secede from India, did not allow a plebiscite to take place in the region. This was confirmed in a statement by India’s Defense Minister, Krishna Menon, who stated: «Kashmir would vote to join Pakistan and no Indian Government responsible for agreeing to plebiscite would survive.»[249]

Pakistan claims that its position is for the right of the Kashmiri people to determine their future through impartial elections as mandated by the United Nations,[250] while India has stated that Kashmir is an «integral part» of India, referring to the 1972 Simla Agreement and to the fact that regional elections take place regularly.[251] In recent developments, certain Kashmiri independence groups believe that Kashmir should be independent of both India and Pakistan.[188]

Law enforcement

The law enforcement in Pakistan is carried out by joint network of several federal and provincial police agencies. The four provinces and the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) each have a civilian police force with jurisdiction extending only to the relevant province or territory.[157] At the federal level, there are a number of civilian intelligence agencies with nationwide jurisdictions including the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) and the Intelligence Bureau (IB), as well as National Guard and the Civil Armed Forces such as the Gilgit-Baltistan Scouts, the Punjab Rangers, and the Frontier Corps Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (North).

The most senior officers of all the civilian police forces also form part of the Police Service, which is a component of the civil service of Pakistan. Namely, there is four provincial police service including the Punjab Police, Sindh Police, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Police, and the Balochistan Police; all headed by the appointed senior Inspector-Generals. The ICT has its own police component, the Capital Police, to maintain law and order in the capital. The CID bureaus are the crime investigation unit and form a vital part in each provincial police service.

The law enforcement in Pakistan also has a Motorway Patrol which is responsible for enforcement of traffic and safety laws, security and recovery on Pakistan’s inter-provincial motorway network. In each of provincial Police Service, it also maintains a respective Elite Police units led by the NACTA—a counter-terrorism police unit as well as providing VIP escorts. In the Punjab and Sindh, the Pakistan Rangers are an internal security force with the prime objective to provide and maintain security in war zones and areas of conflict as well as maintaining law and order which includes providing assistance to the police.[252] The Frontier Corps serves the similar purpose in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and the Balochistan.[252]

Human rights

Male homosexuality is illegal in Pakistan and punishable with up to life in prison.[253] In its 2018 Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders ranked Pakistan number 139 out of 180 countries based on freedom of the press.[254] Television stations and newspapers are routinely shut down for publishing any reports critical of the government or the military.[255]

Military

The armed forces of Pakistan are the sixth largest in the world in terms of numbers in full-time service, with about 651,800 personnel on active duty and 291,000 paramilitary personnel, as of tentative estimates in 2021.[256] They came into existence after independence in 1947, and the military establishment has frequently influenced the national politics ever since.[182] Chain of command of the military is kept under the control of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee; all of the branches joint works, co-ordination, military logistics, and joint missions are under the Joint Staff HQ.[257] The Joint Staff HQ is composed of the Air HQ, Navy HQ, and Army GHQ in the vicinity of the Rawalpindi Military District.[258]

The Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee is the highest principle staff officer in the armed forces, and the chief military adviser to the civilian government though the chairman has no authority over the three branches of armed forces.[257] The Chairman joint chiefs controls the military from the JS HQ and maintains strategic communications between the military and the civilian government.[257] As of 2021, the CJCSC is General Nadeem Raza[259] alongside chief of army staff General Asim Munir,[260][261] chief of naval staff Admiral Muhammad Amjad Khan Niazi,[262] and chief of air staff Air Chief Marshal Zaheer Ahmad Babar.[263] The main branches are the Army, the Air Force and the Navy, which are supported by a large number of paramilitaries in the country.[264] Control over the strategic arsenals, deployment, employment, development, military computers and command and control is a responsibility vested under the National Command Authority which oversaw the work on the nuclear policy as part of the credible minimum deterrence.[115]

The United States, Turkey, and China maintain close military relations and regularly export military equipment and technology transfer to Pakistan.[265] Joint logistics and major war games are occasionally carried out by the militaries of China and Turkey.[264][266] Philosophical basis for the military draft is introduced by the Constitution in times of emergency, but it has never been imposed.[267]

Military history

Since 1947, Pakistan has been involved in four conventional wars with India. The first Indo-Pak war of 1947 occurred in Kashmir with Pakistan gaining control of Western Kashmir, (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan), and India retaining Eastern Kashmir (Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh). Territorial problems eventually led to another conventional war in 1965. The 1971 war resulted in Pakistan’s unconditional surrender of East Pakistan.[268] Tensions in Kargil brought the two countries at the another brink of war.[116] Since 1947 the unresolved territorial problems with Afghanistan saw border skirmishes which were kept mostly at the mountainous border. In 1961, the military and intelligence community repelled the Afghan incursion in the Bajaur Agency near the Durand Line border.[269]

Rising tensions with neighbouring USSR in their involvement in Afghanistan, Pakistani intelligence community, mostly the ISI, systematically coordinated the US resources to the Afghan mujahideen and foreign fighters against the Soviet Union’s presence in the region. Military reports indicated that the PAF was in engagement with the Soviet Air Force, supported by the Afghan Air Force during the course of the conflict; one of which belonged to Alexander Rutskoy.[270] Apart from its own conflicts, Pakistan has been an active participant in United Nations peacekeeping missions. It played a major role in rescuing trapped American soldiers from Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993 in Operation Gothic Serpent.[271][272] According to UN reports, the Pakistani military is the third largest troop contributor to UN peacekeeping missions after Ethiopia and India.[273]

Pakistan has deployed its military in some Arab countries, providing defence, training, and playing advisory roles.[274] The PAF and Navy’s fighter pilots have voluntarily served in Arab nations’ militaries against Israel in the Six-Day War (1967) and in the Yom Kippur War (1973). Pakistan’s fighter pilots shot down ten Israeli planes in the Six-Day War.[271] In the 1973 war, one of the PAF pilots, Flt. Lt. Sattar Alvi (flying a MiG-21), shot down an Israeli Air Force Mirage and was honoured by the Syrian government.[275] Requested by the Saudi monarchy in 1979, Pakistan’s special forces units, operatives, and commandos were rushed to assist Saudi forces in Mecca to lead the operation of the Grand Mosque. For almost two weeks Saudi Special Forces and Pakistani commandos fought the insurgents who had occupied the Grand Mosque’s compound.[276] In 1991, Pakistan became involved with the Gulf War and sent 5,000 troops as part of a US-led coalition, specifically for the defence of Saudi Arabia.[277]

Despite the UN arms embargo on Bosnia, General Javed Nasir of the ISI airlifted anti-tank weapons and missiles to Bosnian mujahideen which turned the tide in favour of Bosnian Muslims and forced the Serbs to lift the siege. Under Nasir’s leadership the ISI was also involved in supporting Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang Province, rebel Muslim groups in the Philippines, and some religious groups in Central Asia.[278]

Since 2004, the military has been engaged in an insurgency in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, mainly against the Tehrik-i-Taliban factions.[279] Major operations undertaken by the army include Operation Black Thunderstorm, Operation Rah-e-Nijat and Operation Zarb-e-Azb.[280]

According to SIPRI, Pakistan was the 9th-largest recipient and importer of arms between 2012 and 2016.[281]

Economy

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2020) |

| Economic indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| GDP (PPP) | $1.254 trillion (2019) | [282] |

| GDP (nominal) | $284.2 billion (2019) | [283] |

| Real GDP growth | 3.29% (2019) | [284] |

| CPI inflation | 10.3% (2019) | [285] |

| Unemployment | 5.7% (2018) | [286] |

| Labor force participation rate | 48.9% (2018) | [287] |

| Total public debt | $106 billion (2019) | |

| National wealth | $465 billion (2019) | [288] |

The economy of Pakistan is the 23rd-largest in the world in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), and 42nd-largest in terms of nominal gross domestic product. Economists estimate that Pakistan was part of the wealthiest region of the world throughout the first millennium CE, with the largest economy by GDP. This advantage was lost in the 18th century as other regions such as China and Western Europe edged forward.[289] Pakistan is considered a developing country[290] and is one of the Next Eleven, a group of eleven countries that, along with the BRICs, have a high potential to become the world’s largest economies in the 21st century.[291]

In recent years, after decades of social instability, as of 2013, serious deficiencies in macromanagement and unbalanced macroeconomics in basic services such as rail transportation and electrical energy generation have developed.[292] The economy is considered to be semi-industrialized, with centres of growth along the Indus River.[293][294][295] The diversified economies of Karachi and Punjab’s urban centres coexist with less-developed areas in other parts of the country, particularly in Balochistan.[294] According to the Economic complexity index, Pakistan is the 67th-largest export economy in the world and the 106th-most complex economy.[296] During the fiscal year 2015–16, Pakistan’s exports stood at US$20.81 billion and imports at US$44.76 billion, resulting in a negative trade balance of US$23.96 billion.[297]

Statue of a bull outside the Pakistan Stock Exchange, Islamabad, Pakistan

As of 2022, Pakistan’s estimated nominal GDP is US$376.493 billion.[298] The GDP by PPP is US$1.512 trillion. The estimated nominal per capita GDP is US$1,658, the GDP (PPP)/capita is US$6,662 (international dollars),[282] According to the World Bank, Pakistan has important strategic endowments and development potential. The increasing proportion of Pakistan’s youth provides the country with both a potential demographic dividend and a challenge to provide adequate services and employment.[299] 21.04% of the population live below the international poverty line of US$1.25 a day. The unemployment rate among the aged 15 and over population is 5.5%.[300] Pakistan has an estimated 40 million middle class citizens, projected to increase to 100 million by 2050.[301] A 2015 report published by the World Bank ranked Pakistan’s economy at 24th-largest[302] in the world by purchasing power and 41st-largest[303] in absolute terms. It is South Asia’s second-largest economy, representing about 15.0% of regional GDP.[304]

| Fiscal Year | GDP growth[305] | Inflation rate[306] |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | ||

| 2014–15 | ||

| 2015–16 | ||

| 2016–17 | ||

| 2017–18 |

Pakistan’s economic growth since its inception has been varied. It has been slow during periods of democratic transition, but robust during the three periods of martial law, although the foundation for sustainable and equitable growth was not formed.[97] The early to middle 2000s was a period of rapid economic reforms; the government raised development spending, which reduced poverty levels by 10% and increased GDP by 3%.[157][307] The economy cooled again from 2007.[157] Inflation reached 25.0% in 2008,[308] and Pakistan had to depend on a fiscal policy backed by the International Monetary Fund to avoid possible bankruptcy.[309] A year later, the Asian Development Bank reported that Pakistan’s economic crisis was easing.[310] The inflation rate for the fiscal year 2010–11 was 14.1%.[311] Since 2013, as part of an International Monetary Fund program, Pakistan’s economic growth has picked up. In 2014 Goldman Sachs predicted that Pakistan’s economy would grow 15 times in the next 35 years to become the 18th-largest economy in the world by 2050.[312] In his 2016 book, The Rise and Fall of Nations, Ruchir Sharma termed Pakistan’s economy as at a ‘take-off’ stage and the future outlook until 2020 has been termed ‘Very Good’. Sharma termed it possible to transform Pakistan from a «low-income to a middle-income country during the next five years».[313]

| Share of world GDP (PPP)[314] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 0.54% |

| 1990 | 0.72% |

| 2000 | 0.74% |

| 2010 | 0.79% |

| 2017 | 0.83% |

Pakistan is one of the largest producers of natural commodities, and its labour market is the 10th-largest in the world. The 7-million–strong Pakistani diaspora contributed US$19.9 billion to the economy in 2015–16.[315][316][317] The major source countries of remittances to Pakistan are: the UAE; the United States; Saudi Arabia; the Gulf states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman); Australia; Canada; Japan; the United Kingdom; Norway; and Switzerland.[318][319] According to the World Trade Organization, Pakistan’s share of overall world exports is declining; it contributed only 0.13% in 2007.[320]

Agriculture and primary sector

The structure of the Pakistani economy has changed from a mainly agricultural to a strong service base. Agriculture as of 2015 accounts for only 20.9% of the GDP.[322] Even so, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Pakistan produced 21,591,400 metric tons of wheat in 2005, more than all of Africa (20,304,585 metric tons) and nearly as much as all of South America (24,557,784 metric tons).[323] Majority of the population, directly or indirectly, is dependent on this sector. It accounts for 43.5% of employed labour force and is the largest source of foreign exchange earnings.[322][324]

A large portion of the country’s manufactured exports is dependent on raw materials such as cotton and hides that are part of the agriculture sector, while supply shortages and market disruptions in farm products do push up inflationary pressures. The country is also the fifth-largest producer of cotton, with cotton production of 14 million bales from a modest beginning of 1.7 million bales in the early 1950s; is self-sufficient in sugarcane; and is the fourth-largest producer in the world of milk. Land and water resources have not risen proportionately, but the increases have taken place mainly due to gains in labour and agriculture productivity. The major breakthrough in crop production took place in the late 1960s and 1970s due to the Green Revolution that made a significant contribution to land and yield increases of wheat and rice. Private tube wells led to a 50 percent increase in the cropping intensity which was augmented by tractor cultivation. While the tube wells raised crop yields by 50 percent, the High Yielding Varieties (HYVs) of wheat and rice led to a 50–60 percent higher yield.[325] Meat industry accounts for 1.4 percent of overall GDP.[326]

Industry

Industry is the second-largest sector of the economy, accounting for 19.74% of gross domestic product (GDP), and 24 percent of total employment. Large-scale manufacturing (LSM), at 12.2% of GDP, dominates the overall sector, accounting for 66% of the sectoral share, followed by small-scale manufacturing, which accounts for 4.9% of total GDP. Pakistan’s cement industry is also fast growing mainly because of demand from Afghanistan and from the domestic real estate sector. In 2013 Pakistan exported 7,708,557 metric tons of cement.[328] Pakistan has an installed capacity of 44,768,250 metric tons of cement and 42,636,428 metric tons of clinker. In 2012 and 2013, the cement industry in Pakistan became the most profitable sector of the economy.[329]

The textile industry has a pivotal position in the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. In Asia, Pakistan is the eighth-largest exporter of textile products, contributing 9.5% to the GDP and providing employment to around 15 million people (some 30% of the 49 million people in the workforce). Pakistan is the fourth-largest producer of cotton with the third-largest spinning capacity in Asia after China and India, contributing 5% to the global spinning capacity.[330] China is the second largest buyer of Pakistani textiles, importing US$1.527 billion of textiles last fiscal. Unlike the US, where mostly value-added textiles are imported, China buys only cotton yarn and cotton fabric from Pakistan. In 2012, Pakistani textile products accounted for 3.3% or US$1.07bn of all UK textile imports, 12.4% or $4.61bn of total Chinese textile imports, 3.0% of all US textile imports ($2,980 million), 1.6% of total German textile imports ($880 million) and 0.7% of total Indian textile imports ($888 million).[331]

Services

Rising skyline of Karachi, with several under construction skyscrapers

As of 2014–15, the services sector makes up 58.8% of GDP[322] and has emerged as the main driver of economic growth.[332] Pakistani society like other developing countries is a consumption oriented society, having a high marginal propensity to consume. The growth rate of services sector is higher than the growth rate of agriculture and industrial sector. Services sector accounts for 54 percent of GDP in 2014 and little over one-third of total employment. Services sector has strong linkages with other sectors of economy; it provides essential inputs to agriculture sector and manufacturing sector.[333] Pakistan’s I.T sector is regarded as among the fastest growing sector’s in Pakistan. The World Economic Forum, assessing the development of Information and Communication Technology in the country ranked Pakistan 110th among 139 countries on the ‘Networked Readiness Index 2016’.[334]

As of May 2020, Pakistan has about 82 million internet users, making it the 9th-largest population of Internet users in the world.[335][336] The current growth rate and employment trend indicate that Pakistan’s Information Communication Technology (ICT) industry will exceed the $10-billion mark by 2020.[337] The sector employees 12,000 and count’s among top five freelancing nations.[338] The country has also improved its export performance in telecom, computer and information services, as the share of their exports surged from 8.2pc in 2005–06 to 12.6pc in 2012–13. This growth is much better than that of China, whose share in services exports was 3pc and 7.7pc for the same period, respectively.[339]

Tourism

With its diverse cultures, people, and landscapes, Pakistan attracted around 6.6 million foreign tourists in 2018,[340] which represented a significant decline since the 1970s when the country received unprecedented numbers of foreign tourists due to the popular Hippie trail. The trail attracted thousands of Europeans and Americans in the 1960s and 1970s who travelled via land through Turkey and Iran into India through Pakistan.[341] Northern Pakistan is well-known for its scenic beauty and several highest peaks of the world. The main destinations of choice for these tourists were the Khyber Pass, Peshawar, Karachi, Lahore, Swat and Rawalpindi.[342] The numbers following the trail declined after the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet–Afghan War.[343]

Pakistan’s tourist attractions range from the mangroves in the south to the Himalayan hill stations in the north-east. The country’s tourist destinations range from the Buddhist ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Taxila, to the 5,000-year-old cities of the Indus Valley civilization such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.[344] Pakistan is home to several mountain peaks over 7,000 metres (23,000 feet).[345] The northern part of Pakistan has many old fortresses, examples of ancient architecture, and the Hunza and Chitral valleys, home to the small pre-Islamic Kalasha community claiming descent from Alexander the Great.[346] Pakistan’s cultural capital, Lahore, contains many examples of Mughal architecture such as the Badshahi Masjid, the Shalimar Gardens, the Tomb of Jahangir, and the Lahore Fort.

In October 2006, just one year after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, The Guardian released what it described as «The top five tourist sites in Pakistan» in order to help the country’s tourism industry.[347] The five sites included Taxila, Lahore, the Karakoram Highway, Karimabad, and Lake Saiful Muluk. To promote Pakistan’s unique cultural heritage, the government organises various festivals throughout the year.[348] In 2015, the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report ranked Pakistan 125 out of 141 countries.[349]

Infrastructure

Pakistan was recognised as the best country for infrastructure development in South Asia during the IWF and World Bank annual meetings in 2016.[350]

Nuclear power and energy

Tarbela Dam, the largest earth filled dam in the world, was constructed in 1968.

As of May 2021, nuclear power is provided by six licensed commercial nuclear power plants.[351] The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) is solely responsible for operating these power plants, while the Pakistan Nuclear Regulatory Authority regulates safe usage of the nuclear energy.[352] The electricity generated by commercial nuclear power plants constitutes roughly 5.8% of Pakistan’s electrical energy, compared to 64.2% from fossil fuels (crude oil and natural gas), 29.9% from hydroelectric power, and 0.1% from coal.[353][354] Pakistan is one of the four nuclear armed states (along with India, Israel, and North Korea) that is not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, but it is a member in good standing of the International Atomic Energy Agency.[355]

The KANUPP-I, a Candu-type nuclear reactor, was supplied by Canada in 1971—the country’s first commercial nuclear power plant. The Sino-Pakistani nuclear cooperation began in the early 1980s. After a Sino-Pakistani nuclear cooperation agreement in 1986,[356] China provided Pakistan with a nuclear reactor dubbed CHASNUPP-I for energy and the industrial growth of the country. In 2005 both countries proposed working on a joint energy security plan, calling for a huge increase in generation capacity to more than 160,000 MWe by 2030. Under its Nuclear Energy Vision 2050, the Pakistani government plans to increase nuclear power generation capacity to 40,000 MWe,[357] 8,900 MWe of it by 2030.[358]

Pakistan produced 1,135 megawatts of renewable energy for the month of October 2016. Pakistan expects to produce 10,000 megawatts of renewable energy by 2025.[359]