When people work closely together, it’s only natural that they have conflicting ideas on how to approach a task or project. They might also clash due to differences in personalities and beliefs, as well as misguided emotions. As sure as the sun will rise, coworkers will enter into conflicts. So you shouldn’t look for ways to avoid disagreements at all costs — they can even be beneficial.

As you will almost certainly find yourself participating in a conflict, you need to learn how to navigate it. In this article, we’ll tell you why words get you in trouble in conflicts and provide 15 useful phrases (with examples in use) to help you steer any disagreement in a healthy and constructive direction.

Why words get us in trouble in conflicts

Conflicts in the workplace are a normal and expected occurrence. They alone are not harmful by default — it’s how we communicate around them that can result in heated confrontations. According to Linda A. Hill, Ph.D. of Harvard Business School, there are three main reasons that explain why we choose the wrong words in conflicts:

- The stakes are high when emotions are high — Conflict usually involves negative emotions, and as most of us are not comfortable with them, the discomfort makes us say (mean) things we don’t mean;

- Our first instinct is to prove we’re right — Our first reaction is to try and prove our position is more valid than the other person’s, instead of focusing on solving the problem together, which is why we can get confrontational or defensive;

- Misalignment between intent and impact — People often mean to say one thing, but the other person misinterprets it to imply something else.

Once you become aware of these “traps”, you can better notice them in yourself and others. As a result, you’ll be able to avoid letting them sway you into a heated argument — and focus on healthy conflict resolution instead.

Perfect phrases for conflict resolution at work (and those to avoid)

Here, we’ll cover 15 amazing phrases for conflict resolution that skilled communicators use to settle any argument without hostility. We’ll provide additional context for their use, explain why they work, and list some of the alternatives you should avoid at all costs in a given situation.

We’ll also provide examples of each phrase in use in the team chat app Pumble.

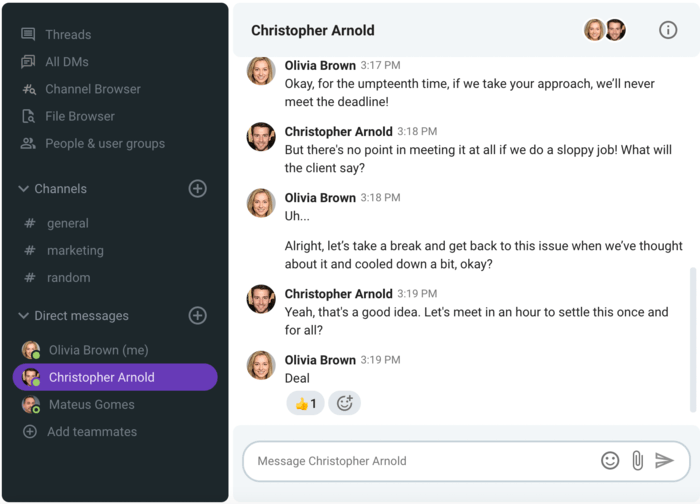

#1 ‘Let’s take a break and get back to this issue when we’ve thought about it and cooled down a bit’

🔶 When to use: You can use this phrase when you notice the argument is getting out of hand, and one or both of you is succumbing to negative emotions. You can also pull this card if you come to an impasse that makes you both impatient for your argument to win.

🔶 Why it works: Taking a break from a confrontation allows you both to cool off and get a fresh perspective on the matter. In most cases, there is a logical solution to the problem, and what’s preventing you from seeing it is your instinct to prove you’re right. However, once you agree to take some time off to think things through, it’s also essential to specify when you’ll get back to the issue so that it doesn’t end up unaddressed in the end and come back to haunt you.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “I can’t deal with this right now.”

- “You’re clearly wrong!”

- “This will never work.”

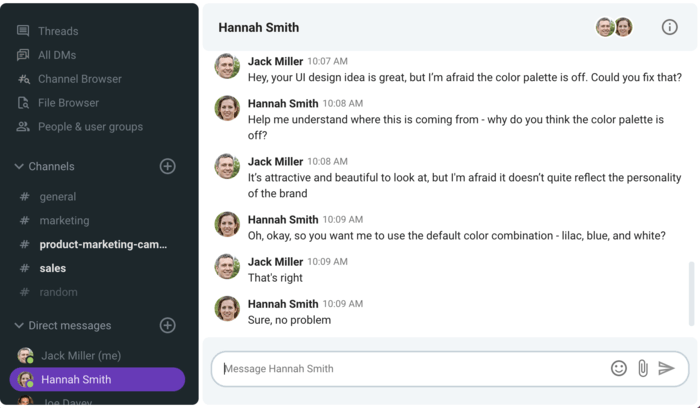

#2 ‘Help me understand where you’re coming from’

🔶 When to use: When you don’t necessarily agree with what the other person is saying or you don’t understand how they came to the idea they’re advocating, you can say this to elicit more information.

🔶 Why it works: One of the biggest communication challenges among coworkers are negative attitudes, and they can exacerbate a conflict. If someone offers critical feedback to you and you get defensive, you’re missing out on the opportunity to understand where the other person is coming from, even if you don’t agree with them. By asking for clarification, you get further insight into their motives and rationale.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “What exactly are you implying?”

- “That makes no sense.”

- That’s ridiculous!”

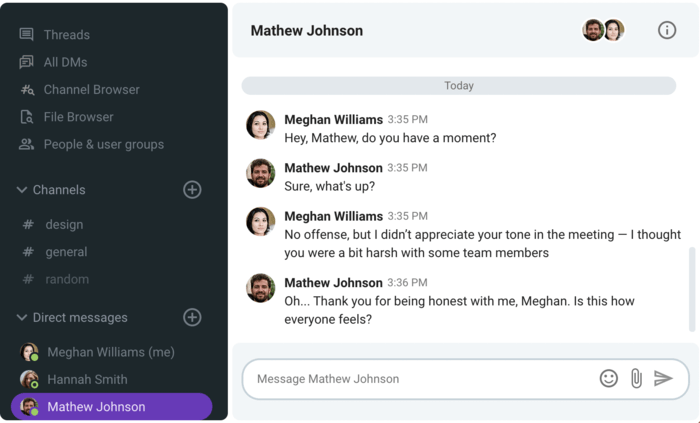

#3 ‘Thank you for being honest with me’

🔶 When to use: This phrase is best for situations where someone is being critical of you, especially if it’s a subordinate who’s providing upward feedback. It’s also great to use when a colleague is directing criticism at you and they are upset about the issue at hand.

🔶 Why it works: The phrase is incredibly effective because it lets the other person know that you’ve truly heard them and, more importantly, you appreciate that they chose an assertive communication approach instead of going behind your back. It also allows you to put yourself in a positive frame of mind so that you can consider what they’re saying instead of just getting hurt and passive-aggressive.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “Wow, I didn’t realize you thought so little of me.”

- “I’m ___ (e.g. sloppy)? Look who’s talking!”

- “What’s that supposed to mean?”

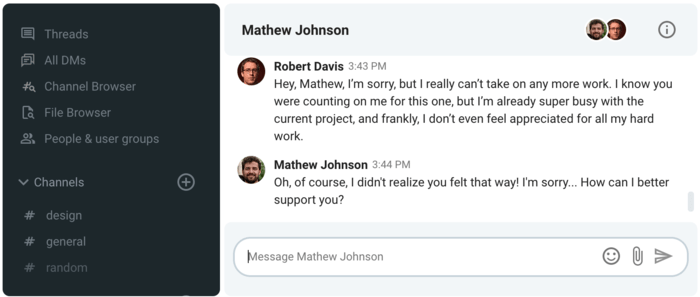

#4 ‘How can I support you?’

🔶 When to use: This phrase should be a staple of any leader’s vocabulary. You can use it if one of your employees feels upset, hurt, underappreciated, or is coming to you with a complaint. However, the phrase is not reserved for leaders alone — anyone at the workplace can benefit from using it.

🔶 Why it works: It works because you’re showing the other person that you truly care about them and want to do what’s best to ease the situation for them. It also showcases your willingness to actively listen and understand where their pain, stress, or frustration is coming from. By offering support, you disarm them and help them let down their guard.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “What am I supposed to do about it?”

- “That’s a ‘you’ problem.”

- “You’re such a baby!”

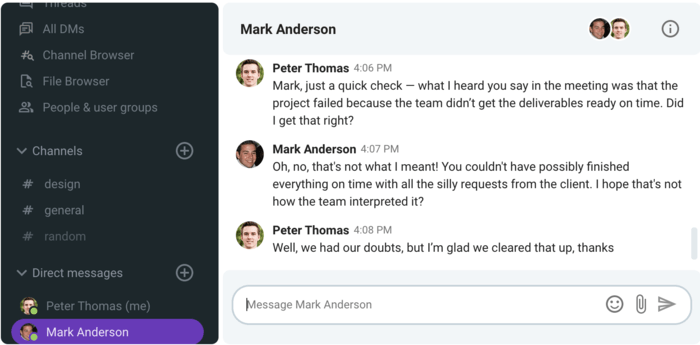

#5 ‘What I heard you say is… Did I get that right?’

🔶 When to use: When you’re not sure you’ve understood something correctly, especially if that something has the potential to wreak havoc on your interpersonal relationships at work, it’s best to check if you’ve got the gist of the issue.

🔶 Why it works: One of the most important rules of workplace chat etiquette is to keep the conversation clear and simple so that there’s no danger of it leading to misunderstandings. That’s why asking for clarification is important. If you throw a fit before you’ve checked whether you’ve correctly understood your interlocutor, you risk starting a fight where there needn’t have been one.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “You’re kidding me, right?”

- “I can’t believe you’ve just said that to me!”

- “Can’t you just speak plain English?”

#6 ‘When you said/did that, I felt…’

🔶 When to use: You can use this phrase when you want to confront a coworker about something they said or did that (inadvertently) affected you in a bad way.

🔶 Why it works: Language plays a vital role here. Instead of attacking them with “you made me feel…”, implying they’re directly responsible for your feelings, you take ownership of your emotions (“I felt…”) while letting them know their words or actions were hurtful. So you’re not accusing them of being a bad person, but rather their words/actions of being inappropriate, which makes a world of a difference and is less likely to make them defensive.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “How could you have possibly done that?”

- “You’re a terrible person!”

- “You make me boil with rage!”

#7 ‘I agree with you on…’

🔶 When to use: When you’re having a disagreement with someone at work (usually about the way to proceed on a shared task or project), but there are still some points about which you’re on the same page, it’s best to start from them if you want to diffuse conflict and improve collaboration.

🔶 Why it works: Agreement on some points sets a common ground from which you can build on. Acknowledging the fact that your views on the matter are not entirely opposing can also reduce the frustration that can build up due to your inability to find a solution and focus your minds on the solvability of the problem, rather than leaving you mentally stuck in a stalemate.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “That’s a stupid idea.”

- “I give up! Just do whatever you want.”

- “We’ll do it my way or I’m out!”

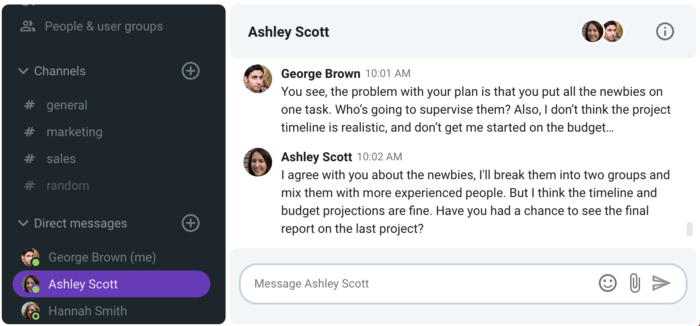

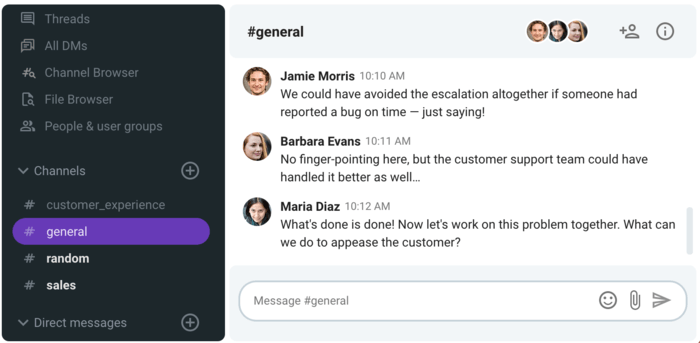

#8 ‘Let’s work on this problem together’

🔶 When to use: This phrase can come in handy when you want to avoid finger-pointing and playing the blame game, especially if you’re a manager trying to stop a conflict from escalating. It can also work well if you want to help someone fix a mistake they made, without making them feel under attack.

🔶 Why it works: It’s great because it inspires healthier team communication and team spirit. Also, when you point out an issue this way, you’re setting a safe psychological space to work from instead of making the person feel threatened.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “This is all your fault!”

- “You need to fix this.”

- “We could have avoided this if John didn’t mess up — just saying!”

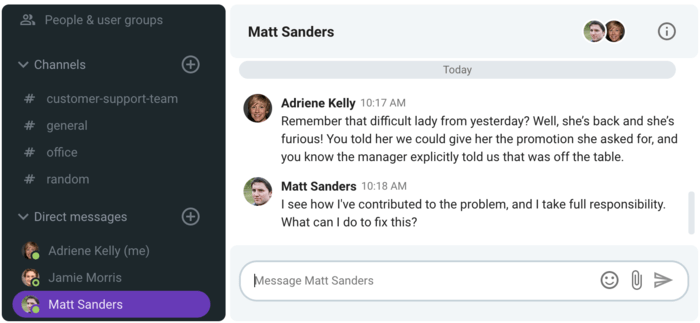

#9 ‘I see how I’ve contributed to the problem’

🔶 When to use: When someone points out you did something wrong, which you didn’t realize before, but now you see it, it’s best to admit it straight up and start the conversation from there.

🔶 Why it works: Admitting your mistakes is always a good idea — it’s human to make them, but it’s incredibly irresponsible not to admit you’ve made them. What’s more, when you recognize you’ve made a mistake, you’re showing the other person that you’re willing to cooperate and let yourself be vulnerable with them. This vulnerability is bound to dispel negative emotions.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “Why are you always picking on me?”

- “Oh, so everything’s always my fault!”

- “Sure, you’re entitled to your opinion.”

#10 ‘I’m sorry’

🔶 When to use: Building on the previous example, once you’ve realized you’ve made a mistake, especially when you’ve directly wronged the other person, it’s only decent to let go of your ego defenses and apologize.

🔶 Why it works: A sincere apology has the power to mend a relationship in a heartbeat. However, beware that an insincere one can further exacerbate the conflict because it can sound dismissive. So don’t apologize just to stop the argument if you don’t mean it — you’ll produce a countereffect.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “Whatever, my bad, can we just move on?”

- “You’re lying.”

- “I wouldn’t have done it in the first place if you hadn’t ____ (messed up first)!”

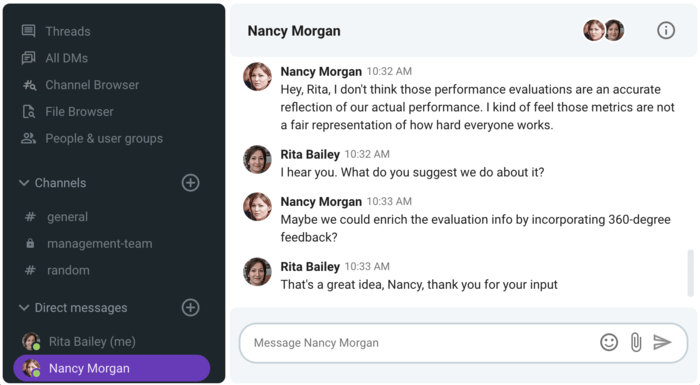

#11 ‘What do you suggest we do about this?’

🔶 When to use: This phrase is universally applicable — every conflict involves at least two people, and the best way to de-escalate it is to work together on it.

🔶 Why it works: It’s effective for multiple reasons. The “we” part implies that you’re willing to approach the problem as a team rather than blame each other for it. Furthermore, your asking for their advice lets them know that you value their opinion and input and are taking the issue seriously.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “I really don’t care about this.”

- “That’s not my problem.”

- “Subject closed!”

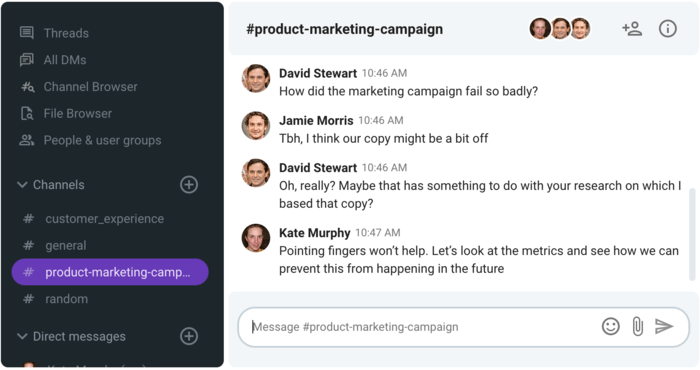

#12 ‘Let’s see how we can prevent this from happening in the future’

🔶 When to use: You can use this phrase when you want to shift focus from finding someone to blame to figuring out what caused the problem and how you can stop it from happening again. Leaders usually use this when they understand that no single person failed, but it was a flaw in the system as a whole that caused the problem.

🔶 Why it works: This phrase puts the conflicted parties at ease because it pits them against the problem — not against each other. They are encouraged to find the solution instead of finding each other’s faults. The phrase also shows the willingness to solve the problem once and for all and leave it behind.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “Whose ‘brilliant’ idea was this?”

- “Okay, who messed up this time?”

- “Who came up with this stupid plan?”

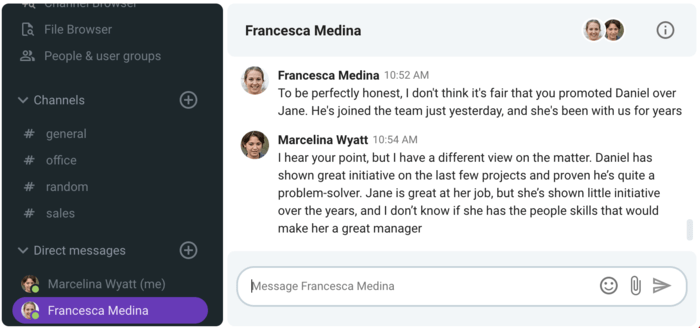

#13 ‘I hear your point, but I have a different view’

🔶 When to use: This is a great phrase to use to present your arguments while also acknowledging the validity of the other person’s perspective. It’s a nice way to set a respectful tone of the argument from the start, instead of getting impatient and giving in to negative emotions.

🔶 Why it works: Even if the other person was feeling passionate about their point of view and started the argument with the sole purpose of winning, this phrase will help ground them and remind them that it’s not a competition.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “Are you listening to yourself?”

- “That makes no sense.”

- “I don’t care what you think!”

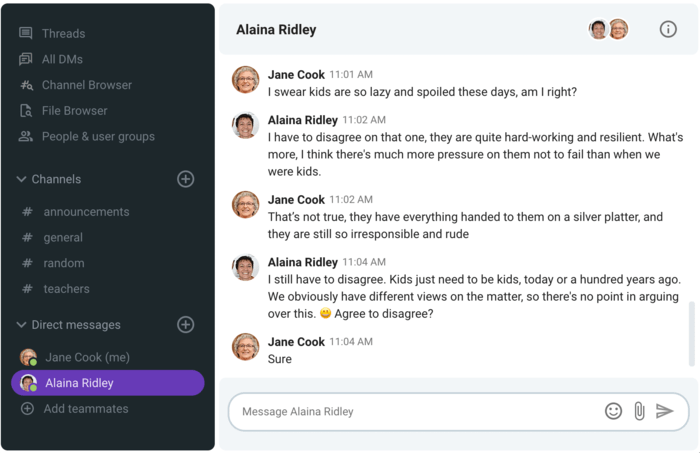

#14 ‘Agree to disagree?’

🔶 When to use: You can resort to this “conclusion” when you’re in the middle of a bitter argument on a subject you really don’t have to agree on, i.e. it’s non-essential for your day-to-day tasks or your relationship with the other person.

🔶 Why it works: Respectfully disagreeing on a non-essential subject can save you from damaging your work relationship over a trivial matter. When you make it clear to the other side that you appreciate the debate and respect their opinion but are unwilling (or unable) to change your stance on the issue, both of you can breathe a sigh of relief and go on with your day without harming your relationship.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “You clearly have no idea what you’re talking about.”

- “I don’t understand how you could even think that.”

- “Stop trying to persuade me, it’s never gonna work!”

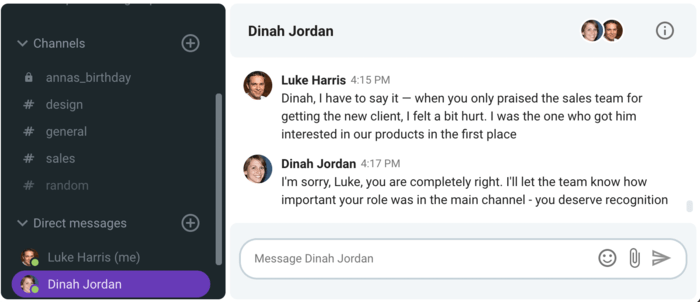

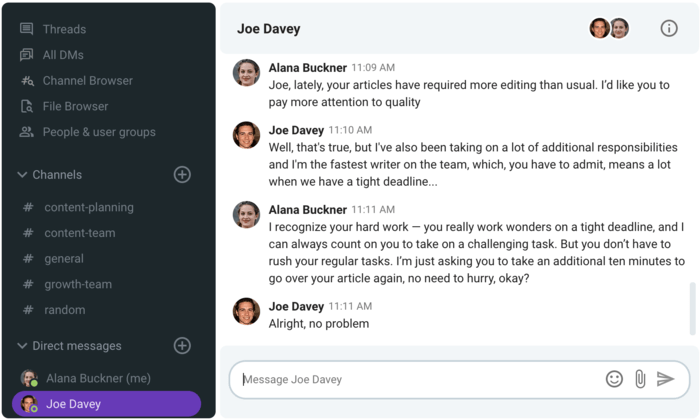

#15 ‘I recognize your hard work…’

🔶 When to use: This is a good way to start a conversation if you want to provide critical feedback on the results of someone’s work, but let them know you appreciate their efforts. This type of recognition is especially important in downward communication, i.e. from higher-ups to subordinates.

🔶 Why it works: Letting people know you believe they made an effort, even if it was unsuccessful, will put them at ease because it shows them you appreciate them and their work. They won’t feel like you’re placing blame on them, but rather like you are trying to help them grow.

🔶 Use it instead of these phrases:

- “You messed up big time!”

- “You idiot, how could you miss that?”

- “What were you thinking?”

Wrapping up: Fight the problem — not each other

As you can see, conflict at work doesn’t have to result in a catty argument and hurt feelings if you handle it well. The next time you find yourself part of a conflict, we hope some of these phrases will come to mind and help you remember that you’re not in it to win it — you’re there to work together on solving the problem which has led to the argument in the first place.

Conflicts are inevitable, and they frequently occur in the workplace as well as in personal lives. With the help of a Conflict Resolution Strategy, an individual or organization can have the upper hand and minimize the adverse outcomes of that conflict.

The ability to positively resolve conflicts is one of the essential value-addition characteristics. On an individual level, when a conflict arises, keeping your emotions in check and analyzing the main concern behind the conflict will channelize conflict resolution in a manner where you will find a win/win for you as well as for another party or individual.

So, if you have also been wanting to understand what conflict resolution is and how you can do it effectively in different professional and personal situations, this post will help you do that efficiently. Let us first start with what is conflict resolution, and then we will dive deeper-

What is Conflict Resolution?

Walking through the narrow paths of human life, all of us encounter conflicts, attempting to tear us apart.

With the world becoming a crisscross of competition and a threshold to overpower each other’s skill-sets, Conflict Resolution has become crucial. Conflicts are a part of life, and it is through these various conflicts that one learns to make the proper decisions that shall leave behind an everlasting impact on us.

Conflict Resolution may be quite simply defined as the formal or informal manner in which two or more concerning parties nearly resolve their conflicts. Most commonly, the concerned parties come to a healthy and peaceful settlement that shall benefit everyone and shall bring an end to the rising dispute.

In its simplest form, conflict resolution goes through six basic steps-

- Defusing emotion

- Listen and accepting

- Getting permission and speaking

- Soliciting agreement

- Working toward resolution

- Closing and agreeing to let go

Why is Conflict Resolution Important?

Whatever may be the cause of the rising conflict or disagreement, it is always crucial to sort out things, instead of walking away, leaving behind things undone.

The essence of every relationship, be it personal or professional, lies in how well one can counter the trials and tribulations that life throws at us, instead of leaving things unkempt.

Each one of us is faced with conflicts in our daily lives. As one goes on to work in a team, facing conflicts of any form becomes an inevitable happening. From having to meditate enraging disputes between colleagues to finding oneself in a rising personal conflict, this has become quite common to encounter.

In a world where everyone is running in the cycle of life, where competition and meeting of deadlines have become all that needs to be taken care of, possessing the perfect Conflict Resolution Skills is crucial.

No matter how much one yearns to live and work in a utopian world, free from conflicts, the reality suggests otherwise. It is a significant part of our public and personal life. In a way, it is these many conflicts, littered in the ways that help us sharpen our skill-sets on how to resolve them effectively.

Conflicts hence may be defined as a healthy part of our life. It helps us, humans, in both standing up to our beliefs and also to make way for small compromises wherever necessary.

In short, Conflict Resolution is something significant for each one of us to learn, understand, and go through.

To understand what is conflict resolution in a much deeper fashion, we should first go through different types of conflicts that occur frequently-

What Are the Types of Conflicts That May Arise?

In our offices or at our workplaces, various types of conflicts may arise amongst fellow employees of the company. Some of the commonly arising conflicts are listed below:

- Conflicts can arise most commonly between co-workers working on the same project. It may also occur between supervisors and their subordinates or maybe between respective service providers and their prospective clients or customers.

- Conflicts may also be found to arise between groups of people who are working together, like, management teams or the labor force. It may also occur between different departments.

Situations where Conflict Resolution is Important

Humans are quite often unconsciously lured into certain emotional or cognitive traps that essentially enclose us in the boundaries of rising conflict.

It hence becomes quite essential for us as separate individuals, to take note of all the prospective emotional factors or cognitive factors that may lead to conflict, thereby making Conflict Resolution a necessary process.

Some of the most commonly found situations that make harnessing our Conflict Resolution Skills of utmost importance are as mentioned under:

1. Self-serving interpretation of what is fair and what is not

Quite often, one is found to assess a situation of judging what should be fair and should not be, by only taking into account our selfish interests.

When faced with such a situation, one is found to assess the situation only by prioritizing ourselves, which, of course, is wrong. It is, when done by each one, shall immediately lead to conflict amongst individuals, making Conflict Resolution a necessary process.

2. Overconfidence

While confidence is a desired quality in humans, overconfidence is deemed undesirable irrespective of the circumstance or place that one may be in. Overconfidence in humans is often found to lead to hasty and unrealistic expectations in the minds of humans.

Disputants are likely to be overconfident of them and hence are quite often faced with situations where they seem to fail miserably. More often than not, these people are found to start an unnecessary conflict.

3. Avoiding conflicts

Often, one may feel that negative emotions like distress or anxiety tend to weigh us down, and, in an attempt to surpass the arising conflicts, parties are found to tamp them down.

By doing this, they generally hope that their feelings too shall dissipate with time, but in vain. With time, the situation, however, worsens even more, and Conflict Resolution seems to be the only hopeful way out.

Steps involved in Conflict Resolution

The whole process of Conflict Resolution is quite simple to understand and go about with. Generally, it shall involve the step-by-step as has been mentioned below:

- Recognition of the concerned parties that conflict, disagreement, problem, or issue exists, and it needs to be resolved.

- Mutual agreement between the concerned parties (two or more) to address the rising conflict healthily and peacefully, by giving sufficient efforts in finding an effective method of resolution

- Substantial efforts need to be given by each of the concerned parties in trying to understand the standpoint or perspective of the opposing party or individual.

- To lessen the high increase in negative feelings by screening and identification of changes in attitude or behavioral patterns as well as approaches given to make things work, in case of both the parties concerned.

- Recognizing potential threats may lead to the arousal of conflicts.

- Suitable interventions may be made by third parties like Human Resources representatives or mangers working at higher levels to meditate and, in turn, resolve the conflict.

- A prospective willing nature in the minds of both the concerning parties to compromise to one another’s needs.

- A judicious agreement is done based on a plan to address the rising differences of opinion effectively.

- Conscious monitoring of the prospective impact of the agreement for any change that may be done

- It is taking into account the proper disciplining or, in some cases, the ultimate termination of employees who may be found to resist any form of effort that may be given to defuse the resulting conflict.

What are the Various Types of Conflict Resolution Skills?

In case one is doubtful of correctly addressing a conflicting situation, then it is highly advisable to go through the facts mentioned below.

By understanding and working according to these mentioned points, one shall be able to dismiss conflicts from their way of life. The various crucial factors that form the essence of Conflict Resolution Skills are as below:

1. Not jumping on to defend oneself

Often, one may find the most comfortable way out of a conflict to be jumping to own defense. One features themselves as someone who is blind to the other person’s perspective. Such a way of thinking will only aggravate the conflicts.

It is always advisable to judge the situation from every possible point of view before jumping on to conclusions. Even if one disagrees with another person’s point of view, it is always essential to pay heed to what the other person thinks or believes.

This will also help in collaborating in a manner that both parties involved in conflicts will ultimately have a win/win situation after the resolution of the conflict.

2. Avoiding pointing fingers

One must also keep in mind that jumping on to the offensive side shall lead a negative impression and a prospective hopeless final solution.

One should never blame other people for failing to create an environment where people are afraid to voice their opinions freely.

The best possible way to harness Conflict Resolution is by allowing each person to voice their argument without getting interrupted. Pointing fingers can turn things more severe that could otherwise be sorted out easily. That is why; not doing things like this is considered essential conflict resolution skills.

3. To listen first, instead of speaking out

Listening intently to what the other person is saying is a significant manner that needs to be harnessed in carving a true gentleman. By listening, one gets to learn the person and their perspectives before they act.

It is hence essential to let the other person place their point of view freely and in an uninterrupted manner. Listening is one of the most crucial skills in conflict resolution, but it should never be understood that you should compromise your stance despite being right.

Listening will empower you in having a better understanding of the situations that will ultimately guide you in putting forward your thoughts in a more effective, constructive, convincing, and wholesome manner that other parties would also listen to you and try to resolve the conflict.

4. Maintaining a calm tone

Conflict Resolution is not borne of rage and a fit of tears threatening to escape.

People need to remain extensively calm and quiet while they are addressing the conflicting situation. No matter how infuriating, enraging, or remorseful the situation might be, one should never let their emotions do the talking while addressing a conflict.

Preparing oneself beforehand to be able to face one’s opponents without letting out their emotions is a crucial part of Conflict Resolution Skills. With a calm tone, you will be able to let the other party understand your view-point, plus you will always be in your control to make rational points.

5. Willing to make way for a compromise

Depending upon the situation, we need to make way for small compromises here and there.

Being flexible in assessing various situations and addressing them effectively, through small and trivial compromises is essential. It is always necessary to come to a mutual understanding of the way of things by letting go of one’s overburdening sense of ego and pride.

You might face some conflicts where the strengths and power of an individual decide who will win the conflict. This may lead to a win/lose situation, and you need to understand if you should compete or fight or make a compromise for effective conflict resolution.

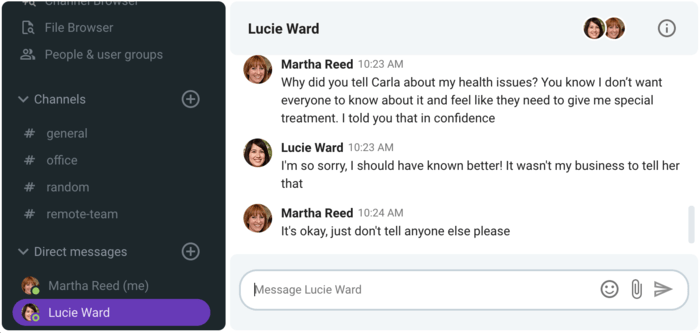

6. Not talking behind people’s backs

Even though, as humans, one tends to give vent to our feelings by sharing it with others, it is essential to keep that one should not harm the other person’s respect in any way.

It is essential to give respect to people’s privacy and hence not talk about them behind their backs.

It will let you face lesser instances of facing conflicts with the same person again.

Here is a video by Marketing91 on Conflict Resolution.

Final Thoughts!

Even though conflicts are unavoidable, they are not impossible to manage or resolve. Ineffectively handling conflicts, it is vital to know one’s limitations and boundaries.

One should remember that even while going through the Conflict Resolution process, they may feel a lack of confidence in themselves or their interventions. In a situation like this, one should always keep in mind that it is okay to step back and, in turn, involve a trained mediator to resolve the issue in a better way.

Conflict resolution processes can also be frustrating some of the time, but incorporating the skills mentioned above for resolving conflicts will help you effectively.

Additionally, active listening, emotional intelligence, patience, positivity, impartiality, and open communication are some of the personal characteristics that are considered highly effective in resolving conflicts.

On the concluding note, we hope you would have understood what conflict resolution is and what the crucial Conflict Resolution Skills are that can help you in different conflicting situations.

What are your thoughts about the effectiveness of conflict resolution skills shared in the post? Do you want to add some other skills for resolving conflicts? Then share that in the comment section below.

Liked this post? Check out these detailed articles on Topic of MANAGEMENT

Alternatively, check out the Marketing91 Academy, which provides you access to 10+ marketing courses and 100s of Case studies.

Conflict resolution is conceptualized as the methods and processes involved in facilitating the peaceful ending of conflict and retribution. Committed group members attempt to resolve group conflicts by actively communicating information about their conflicting motives or ideologies to the rest of group (e.g., intentions; reasons for holding certain beliefs) and by engaging in collective negotiation.[1] Dimensions of resolution typically parallel the dimensions of conflict in the way the conflict is processed. Cognitive resolution is the way disputants understand and view the conflict, with beliefs, perspectives, understandings and attitudes. Emotional resolution is in the way disputants feel about a conflict, the emotional energy. Behavioral resolution is reflective of how the disputants act, their behavior.[2] Ultimately a wide range of methods and procedures for addressing conflict exist, including negotiation, mediation, mediation-arbitration,[3] diplomacy, and creative peacebuilding.[4][5]

The term conflict resolution may also be used interchangeably with dispute resolution, where arbitration and litigation processes are critically involved. The concept of conflict resolution can be thought to encompass the use of nonviolent resistance measures by conflicted parties in an attempt to promote effective resolution.[6]

Theories and models[edit]

There are a plethora of different theories and models linked to the concept of conflict resolution. A few of them are described below.

Conflict resolution curve[edit]

There are many examples of conflict resolution in history, and there has been a debate about the ways to conflict resolution: whether it should be forced or peaceful. Conflict resolution by peaceful means is generally perceived to be a better option. The conflict resolution curve derived from an analytical model that offers a peaceful solution by motivating conflicting entities.[7] Forced resolution of conflict might invoke another conflict in the future.

Conflict resolution curve (CRC) separates conflict styles into two separate domains: domain of competing entities and domain of accommodating entities. There is a sort of agreement between targets and aggressors on this curve. Their judgements of badness compared to goodness of each other are analogous on CRC. So, arrival of conflicting entities to some negotiable points on CRC is important before peace building. CRC does not exist (i.e., singular) in reality if the aggression of the aggressor is certain. Under such circumstances it might lead to apocalypse with mutual destruction.[8]

The curve explains why nonviolent struggles ultimately toppled repressive regimes and sometimes forced leaders to change the nature of governance. Also, this methodology has been applied to capture conflict styles on the Korean Peninsula and dynamics of negotiation processes.[9]

Dual concern model[edit]

The dual concern model of conflict resolution is a conceptual perspective that assumes individuals’ preferred method of dealing with conflict is based on two underlying themes or dimensions: concern for self (assertiveness) and concern for others (empathy).[1]

According to the model, group members balance their concern for satisfying personal needs and interests with their concern for satisfying the needs and interests of others in different ways. The intersection of these two dimensions ultimately leads individuals towards exhibiting different styles of conflict resolution.[10] The dual model identifies five conflict resolution styles or strategies that individuals may use depending on their dispositions toward pro-self or pro-social goals.

Avoidance conflict style

- Characterized by joking, changing or avoiding the topic, or even denying that a problem exists, the conflict avoidance style is used when an individual has withdrawn in dealing with the other party, when one is uncomfortable with conflict, or due to cultural contexts.[nb 1] During conflict, these avoiders adopt a «wait and see» attitude, often allowing conflict to phase out on its own without any personal involvement.[11] By neglecting to address high-conflict situations, avoiders risk allowing problems to fester or spin out of control.

Accommodating conflict style

- In contrast, yielding, «accommodating», smoothing or suppression conflict styles are characterized by a high level of concern for others and a low level of concern for oneself. This passive pro-social approach emerges when individuals derive personal satisfaction from meeting the needs of others and have a general concern for maintaining stable, positive social relationships.[1] When faced with conflict, individuals with an accommodating conflict style tend to harmonize into others’ demands out of respect for the social relationship. With this sense of yielding to the conflict, individuals fall back to others’ input instead of finding solutions with their own intellectual resolution.[12]

Competitive conflict style

- The competitive, «fighting» or forcing conflict style maximizes individual assertiveness (i.e., concern for self) and minimizes empathy (i.e., concern for others). Groups consisting of competitive members generally enjoy seeking domination over others, and typically see conflict as a «win or lose» predicament.[1] Fighters tend to force others to accept their personal views by employing competitive power tactics (arguments, insults, accusations or even violence) that foster intimidation.[13]

Conciliation conflict style

- The conciliation, «compromising», bargaining or negotiation conflict style is typical of individuals who possess an intermediate level of concern for both personal and others’ outcomes. Compromisers value fairness and, in doing so, anticipate mutual give-and-take interactions.[11] By accepting some demands put forth by others, compromisers believe this agreeableness will encourage others to meet them halfway, thus promoting conflict resolution.[14] This conflict style can be considered an extension of both «yielding» and «cooperative» strategies.[1]

Cooperation conflict style

- Characterized by an active concern for both pro-social and pro-self behavior, the cooperation, integration, confrontation or problem-solving conflict style is typically used when an individual has elevated interests in their own outcomes as well as in the outcomes of others. During conflict, cooperators collaborate with others in an effort to find an amicable solution that satisfies all parties involved in the conflict. Individuals using this type of conflict style tend to be both highly assertive and highly empathetic.[11] By seeing conflict as a creative opportunity, collaborators willingly invest time and resources into finding a «win-win» solution.[1] According to the literature on conflict resolution, a cooperative conflict resolution style is recommended above all others. This resolution may be achieved by lowering the aggressor’s guard while raising the ego.[15][16]

Relational dialectics theory[edit]

Relational dialectics theory (RDT), introduced by Leslie Baxter and Barbara Matgomery (1988),[17][18] explores the ways in which people in relationships use verbal communication to manage conflict and contradiction as opposed to psychology. This concept focuses on maintaining a relationship even through contradictions that arise and how relationships are managed through coordinated talk. RDT assumes that relationships are composed of opposing tendencies, are constantly changing, and tensions arises from intimate relationships.

The main concepts of RDT are:

- Contradictions – The concept is that the contrary has the characteristics of its opposite. People can seek to be in a relationship but still need their space.

- Totality – The totality comes when the opposites unite. Thus, the relationship is balanced with contradictions and only then it reaches totality

- Process – Comprehended through various social processes. These processes simultaneously continue within a relationship in a recurring manner.

- Praxis – The relationship progresses with experience and both people interact and communicate effectively to meet their needs. Praxis is a concept of practicability in making decisions in a relationship despite opposing wants and needs

Strategy of conflict[edit]

Strategy of conflict, by Thomas Schelling, is the study of negotiation during conflict and strategic behavior that results in the development of «conflict behavior». This idea is based largely on game theory. In «A Reorientation of Game Theory», Schelling discusses ways in which one can redirect the focus of a conflict in order to gain advantage over an opponent.

- Conflict is a contest. Rational behavior, in this contest, is a matter of judgment and perception.

- Strategy makes predictions using «rational behavior – behavior motivated by a serious calculation of advantages, a calculation that in turn is based on an explicit and internally consistent value system».

- Cooperation is always temporary, interests will change.

Conflict resolution in peace and conflict studies[edit]

Definition[edit]

Within peace and conflict studies a definition of conflict resolution is presented in Peter Wallensteen’s book Understanding Conflict Resolution:

Conflict resolution is a social situation where the armed conflicting parties in a (voluntarily) agreement resolve to live peacefully with – and/or dissolve – their basic incompatibilities and henceforth cease to use arms against one another.[19]

The «conflicting parties» concerned in this definition are formally or informally organized groups engaged in intrastate or interstate conflict.[20][21][22][23]

‘Basic incompatibility’ refers to a severe disagreement between at least two sides where their demands cannot be met by the same resources at the same time.[24]

Mechanisms[edit]

One theory discussed within the field of peace and conflict studies is conflict resolution mechanisms: independent procedures in which the conflicting parties can have confidence. They can be formal or informal arrangements with the intention of resolving the conflict.[25] In Understanding Conflict Resolution Wallensteen draws from the works of Lewis A. Coser, Johan Galtung and Thomas Schelling, and presents seven distinct theoretical mechanisms for conflict resolutions:[26]

- A shift in priorities for one of the conflicting parties. While it is rare that a party completely changes its basic positions, it can display a shift in to what it gives highest priority. In such an instance new possibilities for conflict resolutions may arise.

- The contested resource is divided. In essence, this means both conflicting parties display some extent of shift in priorities which then opens up for some form of «meeting the other side halfway» agreement.

- Horse-trading between the conflicting parties. This means that one side gets all of its demands met on one issue, while the other side gets all of its demands met on another issue.

- The parties decide to share control, and rule together over the contested resource. It could be permanent, or a temporary arrangement for a transition period that, when over, has led to a transcendence of the conflict.

- The parties agree to leave control to someone else. In this mechanism the primary parties agree, or accept, that a third party takes control over the contested resource.

- The parties resort to conflict resolution mechanisms, notably arbitration or other legal procedures. This means finding a procedure for resolving the conflict through some of the previously mentioned five ways, but with the added quality that it is done through a process outside of the parties’ immediate control.

- Some issues can be left for later. The argument for this is that political conditions and popular attitudes can change, and some issues can gain from being delayed, as their significance may pale with time.

Intrastate and interstate[edit]

According to conflict database Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s definition war may occur between parties who contest an incompatibility. The nature of an incompatibility can be territorial or governmental, but a warring party must be a «government of a state or any opposition organization or alliance of organizations that uses armed force to promote its position in the incompatibility in an intrastate or an interstate armed conflict».[27] Wars can conclude with a peace agreement, which is a «formal agreement… which addresses the disputed incompatibility, either by settling all or part of it, or by clearly outlining a process for how […] to regulate the incompatibility.»[28] A ceasefire is another form of agreement made by warring parties; unlike a peace agreement, it only «regulates the conflict behaviour of warring parties», and does not resolve the issue that brought the parties to war in the first place.[29]

Peacekeeping measures may be deployed to avoid violence in solving such incompatibilities.[30] Beginning in the last century, political theorists have been developing the theory of a global peace system that relies upon broad social and political measures to avoid war in the interest of achieving world peace.[31] The Blue Peace approach developed by Strategic Foresight Group facilitates cooperation between countries over shared water resources, thus reducing the risk of war and enabling sustainable development.[32]

Conflict resolution is an expanding field of professional practice, both in the U.S. and around the world. The escalating costs of conflict have increased use of third parties who may serve as a conflict specialists to resolve conflicts. In fact, relief and development organizations have added peace-building specialists to their teams.[33] Many major international non-governmental organizations have seen a growing need to hire practitioners trained in conflict analysis and resolution. Furthermore, this expansion has resulted in the need for conflict resolution practitioners to work in a variety of settings such as in businesses, court systems, government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and educational institutions throughout the world.

In the workplace[edit]

According to the Cambridge dictionary, a basic definition of conflict is: «an active disagreement between people with opposing opinions or principles.»[34] Conflicts such as disagreements may occur at any moment, being a normal part of human interactions. The type of conflict and its severity may vary both in content and degree of seriousness; however, it is impossible to completely avoid it. Actually, conflict in itself is not necessarily a negative thing. When handled constructively it can help people to stand up for themselves and others, to evolve and learn how to work together to achieve a mutually satisfactory solution. But if conflict is handled poorly it can cause anger, hurt, divisiveness and more serious problems.

If it is impossible to completely avoid conflict as it was said, the possibilities to experience it are usually higher particularly in complex social contexts in which important diversities are at stake. Specially because of this reason, speaking about conflict resolution becomes fundamental in ethnically diverse and multicultural work environments, in which not only «regular» work disagreements may occur but in which also different languages, worldviews, lifestyles and ultimately value differences may diverge.

Conflict resolution is the process by which two or more parties engaged in a disagreement, dispute or debate reach an agreement resolving it.[35] It involves a series of stages, involved actors, models and approaches that may depend on the kind of confrontation at stake and the surrounded social and cultural context. However, there are some general actions and personal skills that may be very useful when facing a conflict to solve (independently of its nature), e.g. an open minded orientation able to analyze the different point of views and perspectives involved, as well as an ability to empathize, carefully listen and clearly communicate with all the parts involved. Sources of conflict may be so many, depending on the particular situation and the specific context, but some of the most common include:

Personal differences such as values, ethics, personalities, age, education, gender, socioeconomic status, cultural background, temperament, health, religion, political beliefs, etc. Thus, almost any social category that serves to differentiate people may become an object of conflict when it does negatively diverge with people who do not share it.[36] Clashes of ideas, choices or actions. Conflict occurs when people does not share common goals, or common ways to reach a particular objective (e.g. different work styles). Conflict occurs also when there is direct or indirect competition between people or when someone may feel excluded from a particular activity or by some people within the company. Lack of communication or poor communication are also significant reasons to start a conflict, to misunderstand a particular situation and to create potentially explosive interactions.[37]

Fundamental strategies[edit]

Although different conflicts may require different ways to handle them, this is a list of fundamental strategies that may be implemented when handling a conflictive situation:[38]

- Reaching agreement on rules and procedures: Establishing ground rules may include the following actions: a. Determining a site for the meeting; b. Setting a formal agenda; c. Determining who attends; d. Setting time limits; e. Setting procedural rules; f. Following specific «do(s) and don’t(s)».

- Reducing tension and synchronizing the de-escalation of hostility: In highly emotional situations when people feel angry, upset, frustrated, it is important to implement the following actions: a. Separating the involved parties; b. Managing tensions – jokes as an instrument to give the opportunity for catharsis; c. Acknowledging others’ feelings – actively listening to others; d. De-escalation by public statements by parties – about the concession, the commitments of the parties.

- Improving the accuracy of communication, particularly improving each party’s understanding of the other’s perception: a. Accurate understanding of the other’s position; b. Role reversal, trying to adopt the other’s position (empathetic attitudes); c. Imaging – describing how they see themselves, how the other parties appears to them, how they think the other parties will describe them and how the others see themselves.

- Controlling the number and size of issues in the discussion: a. Fractionate the negotiation – a method that divides a large conflict into smaller parts: 1. Reduce the number of parties on each side; 2. Control the number of substantive issues; 3. Search for different ways to divide big issues.

- Establishing common ground where parties can find a basis for agreement: a. Establishing common goals or superordinate goals; b. Establishing common enemies; c. Identifying common expectations; d. Managing time constraints and deadlines; e. Reframing the parties’ view of each other; f. Build trust through the negotiation process.

- Enhancing the desirability of the options and alternatives that each party presents to the other: a. Giving the other party an acceptable proposal; b. Asking for a different decision; c. Sweeten the other rather than intensifying the threat; d. Elaborating objective or legitimate criteria to evaluate all possible solutions.[39]

Approaches[edit]

A conflict is a common phenomenon in the workplace; as mentioned before, it can occur because of the most different grounds of diversity and under very different circumstances. However, it is usually a matter of interests, needs, priorities, goals or values interfering with each other; and, often, a result of different perceptions more than actual differences. Conflicts may involve team members, departments, projects, organization and client, boss and subordinate, organization needs vs. personal needs, and they are usually immersed in complex relations of power that need to be understood and interpreted in order to define the more tailored way to manage the conflict. There are, nevertheless, some main approaches that may be applied when trying to solve a conflict that may lead to very different outcomes to be valued according to the particular situation and the available negotiation resources:

Forcing[edit]

When one of the conflict’s parts firmly pursues his or her own concerns despite the resistance of the other(s). This may involve pushing one viewpoint at the expense of another or maintaining firm resistance to the counterpart’s actions; it is also commonly known as «competing».

Forcing may be appropriate when all other, less forceful methods, do not work or are ineffective; when someone needs to stand up for his/her own rights (or the represented group/organization’s rights), resist aggression and pressure. It may be also considered a suitable option when a quick resolution is required and using force is justified (e.g. in a life-threatening situation, to stop an aggression), and as a very last resort to resolve a long-lasting conflict.

However, forcing may also negatively affect the relationship with the opponent in the long run; may intensified the conflict if the opponent decides to react in the same way (even if it was not the original intention); it does not allow to take advantage in a productive way of the other side’s position and, last but not least, taking this approach may require a lot of energy and be exhausting to some individuals.

Win-win / collaborating[edit]

Collaboration involves an attempt to work with the other part involved in the conflict to find a win-win solution to the problem in hand, or at least to find a solution that most satisfies the concerns of both parties. The win-win approach sees conflict resolution as an opportunity to come to a mutually beneficial result; and it includes identifying the underlying concerns of the opponents and finding an alternative which meets each party’s concerns. From that point of view, it is the most desirable outcome when trying to solve a problem for all partners.

Collaborating may be the best solution when consensus and commitment of other parties is important; when the conflict occurs in a collaborative, trustworthy environment and when it is required to address the interests of multiple stakeholders. But more specially, it is the most desirable outcome when a long-term relationship is important so that people can continue to collaborate in a productive way; collaborating is in few words, sharing responsibilities and mutual commitment. For parties involved, the outcome of the conflict resolution is less stressful; however, the process of finding and establishing a win-win solution may be longer and should be very involving.

It may require more effort and more time than some other methods; for the same reason, collaborating may not be practical when timing is crucial and a quick solution or fast response is required.

Compromising[edit]

Different from the win-win solution, in this outcome the conflict parties find a mutually acceptable solution which partially satisfies both parties. This can occur as both parties converse with one another and seek to understand the other’s point of view.[40] Compromising may be an optimal solution when the goals are moderately important and not worth the use of more assertive or more involving approaches. It may be useful when reaching temporary settlement on complex issues and as a first step when the involved parties do not know each other well or have not yet developed a high level of mutual trust. Compromising may be a faster way to solve things when time is a factor. The level of tensions can be lower as well, but the result of the conflict may be also less satisfactory.

If this method is not well managed, and the factor time becomes the most important one, the situation may result in both parties being not satisfied with the outcome (i.e. a lose-lose situation). Moreover, it does not contribute to building trust in the long run and it may require a closer monitoring of the kind of partially satisfactory compromises acquired.

Withdrawing[edit]

This technique consists on not addressing the conflict, postpone it or simply withdrawing; for that reason, it is also known as Avoiding. This outcome is suitable when the issue is trivial and not worth the effort or when more important issues are pressing, and one or both the parties do not have time to deal with it. Withdrawing may be also a strategic response when it is not the right time or place to confront the issue, when more time is needed to think and collect information before acting or when not responding may bring still some winnings for at least some of the involves parties. Moreover, withdrawing may be also employed when someone know that the other party is totally engaged with hostility and does not want (can not) to invest further unreasonable efforts.

Withdrawing may give the possibility to see things from a different perspective while gaining time and collecting further information, and specially is a low stress approach particularly when the conflict is a short time one. However, not acting may be interpreted as an agreement and therefore it may lead to weakening or losing a previously gained position with one or more parties involved. Furthermore, when using withdrawing as a strategy more time, skills and experiences together with other actions may need to be implemented.

Smoothing[edit]

Smoothing is accommodating the concerns of others first of all, rather than one’s own concerns. This kind of strategy may be applied when the issue of the conflict is much more important for the counterparts whereas for the other is not particularly relevant. It may be also applied when someone accepts that he/she is wrong and furthermore there are no other possible options than continuing an unworthy competing-pushing situation. Just as withdrawing, smoothing may be an option to find at least a temporal solution or obtain more time and information, however, it is not an option when priority interests are at stake.

There is a high risk of being abused when choosing the smoothing option. Therefore, it is important to keep the right balance and to not give up one own interests and necessities. Otherwise, confidence in one’s ability, mainly with an aggressive opponent, may be seriously damaged, together with credibility by the other parties involved. Needed to say, in these cases a transition to a Win-Win solution in the future becomes particularly more difficult when someone.

Between organizations[edit]

Relationships between organizations, such as strategic alliances, buyer-supplier partnerships, organizational networks, or joint ventures are prone to conflict. Conflict resolution in inter-organizational relationships has attracted the attention of business and management scholars. They have related the forms of conflict (e.g., integrity-based vs. competence-based conflict) to the mode of conflict resolution[41] and the negotiation and repair approaches used by organizations. They have also observed the role of important moderating factors such as the type of contractual arrangement,[42] the level of trust between organizations,[43] or the type of power asymmetry.[44]

Other forms[edit]

Conflict management[edit]

Conflict management refers to the long-term management of intractable conflicts. It is the label for the variety of ways by which people handle grievances—standing up for what they consider to be right and against what they consider to be wrong. Those ways include such diverse phenomena as gossip, ridicule, lynching, terrorism, warfare, feuding, genocide, law, mediation, and avoidance.[45] Which forms of conflict management will be used in any given situation can be somewhat predicted and explained by the social structure—or social geometry—of the case.

Conflict management is often considered to be distinct from conflict resolution.

In order for actual conflict to occur, there should be an expression of exclusive patterns which explain why and how the conflict was expressed the way it was. Conflict is often connected to a previous issue. Resolution refers to resolving a dispute to the approval of one or both parties, whereas management is concerned with an ongoing process that may never have a resolution. Neither is considered the same as conflict transformation, which seeks to reframe the positions of the conflict parties.

Counseling[edit]

When personal conflict leads to frustration and loss of efficiency, counseling may prove helpful. Although few organizations can afford to have professional counselors on staff, given some training, managers may be able to perform this function. Nondirective counseling, or «listening with understanding», is little more than being a good listener—something often considered to be important in a manager.[46]

Sometimes simply being able to express one’s feelings to a concerned and understanding listener is enough to relieve frustration and make it possible for an individual to advance to a problem-solving frame of mind. The nondirective approach is one effective way for managers to deal with frustrated subordinates and coworkers.[47]

There are other, more direct and more diagnostic, methods that could be used in appropriate circumstances. However, the great strength of the nondirective approach[nb 2] lies in its simplicity, its effectiveness, and that it deliberately avoids the manager-counselor’s diagnosing and interpreting emotional problems, which would call for special psychological training. Listening to staff with sympathy and understanding is unlikely to escalate the problem, and is a widely used approach for helping people cope with problems that interfere with their effectiveness in the workplace.[47]

Culture-based[edit]

The Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau (illustration from a Bible card published 1907 by the Providence Lithograph Company)

Conflict resolution as both a professional practice and academic field is highly sensitive to cultural practices. In Western cultural contexts, such as Canada and the United States, successful conflict resolution usually involves fostering communication among disputants, problem solving, and drafting agreements that meet underlying needs. In these situations, conflict resolvers often talk about finding a mutually satisfying («win-win») solution for everyone involved.[48]

In many non-Western cultural contexts, such as Afghanistan, Vietnam, and China, it is also important to find «win-win» solutions; however, the routes taken to find them may be very different. In these contexts, direct communication between disputants that explicitly addresses the issues at stake in the conflict can be perceived as very rude, making the conflict worse and delaying resolution. It can make sense to involve religious, tribal, or community leaders; communicate difficult truths through a third party; or make suggestions through stories.[49] Intercultural conflicts are often the most difficult to resolve because the expectations of the disputants can be very different, and there is much occasion for misunderstanding.[50]

In a 2017 blog post on «the ocean model of civilization» for the British Academy, Nayef Al-Rodhan argued that greater transcultural understanding is critical for global security because it diminishes ‘hierarchies’ and alienation, and avoids dehumanization of the ‘other’.[51]

In animals[edit]

Conflict resolution has also been studied in non-humans, including dogs, cats, monkeys, snakes, elephants, and primates.[52] Aggression is more common among relatives and within a group than between groups. Instead of creating distance between the individuals, primates tend to be more intimate in the period after an aggressive incident. These intimacies consist of grooming and various forms of body contact. Stress responses, including increased heart rates, usually decrease after these reconciliatory signals. Different types of primates, as well as many other species who live in groups, display different types of conciliatory behavior. Resolving conflicts that threaten the interaction between individuals in a group is necessary for survival, giving it a strong evolutionary value.[citation needed] These findings contradict previous existing theories about the general function of aggression, i.e. creating space between individuals (first proposed by Konrad Lorenz), which seems to be more the case in conflicts between groups than it is within groups.

In addition to research in primates, biologists are beginning to explore reconciliation in other animals. Until recently, the literature dealing with reconciliation in non-primates has consisted of anecdotal observations and very little quantitative data. Although peaceful post-conflict behavior had been documented going back to the 1960s, it was not until 1993 that Rowell made the first explicit mention of reconciliation in feral sheep. Reconciliation has since been documented in spotted hyenas,[53][54] lions, bottlenose dolphins,[55] dwarf mongoose, domestic goats,[56] domestic dogs,[57] and, recently, in red-necked wallabies.[58]

Education[edit]

Universities worldwide offer programs of study pertaining to conflict research, analysis, and practice. Conrad Grebel University College at the University of Waterloo has the oldest-running peace and conflict studies (PACS) program in Canada.[59] PACS can be taken as an Honors, 4-year general, or 3-year general major, joint major, minor, and diploma. Grebel also offers an interdisciplinary Master of Peace and Conflict Studies professional program. The Cornell University ILR School houses the Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution, which offers undergraduate, graduate, and professional training on conflict resolution.[60] It also offers dispute resolution concentrations for its MILR, JD/MILR, MPS, and MS/PhD graduate degree programs.[61] At the graduate level, Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding offers a Master of Arts in Conflict Transformation, a dual Master of Divinity/MA in Conflict Transformation degree, and several graduate certificates.[62] EMU also offers an accelerated 5-year BA in Peacebuilding and Development/MA in Conflict Transformation. Additional graduate programs are offered at Georgetown University, Johns Hopkins University, Creighton University, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and Trinity College Dublin.[63] George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution offers BA, BS, MS, and PhD degrees in Conflict Analysis and Resolution, as well as an undergraduate minor, graduate certificates, and joint degree programs.[64] Nova Southeastern University also offers a PhD in Conflict Analysis & Resolution, in both online and on-campus formats.[65]

Conflict resolution is a growing area of interest in UK pedagogy, with teachers and students both encouraged to learn about mechanisms that lead to aggressive action and those that lead to peaceful resolution. The University of Law, one of the oldest common law training institutions in the world, offers a legal-focused master’s degree in conflict resolution as an LL.M. (Conflict resolution).[66]

Tel Aviv University offers two graduate degree programs in the field of conflict resolution, including the English-language International Program in Conflict Resolution and Mediation, allowing students to learn in a geographic region which is the subject of much research on international conflict resolution.

The Nelson Mandela Center for Peace & Conflict Resolution at Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi, is one of the first centers for peace and conflict resolution to be established at an Indian university. It offers a two-year full-time MA course in Conflict Analysis and Peace-Building, as well as a PhD in Conflict and Peace Studies.[67]

In Sweden Linnaeus University, Lund University and Uppsala University offer programs on bachelor, master and/or doctoral level in Peace and Conflict Studies.[68][69][70] Uppsala University also hosts its own Department of Peace and Conflict Research, among other things occupied with running the conflict database UCDP (Uppsala Conflict Data Program).[70][71]

See also[edit]

- Civil resistance

- Conflict continuum

- Conflict early warning

- Conflict management

- Conflict resolution research

- Conflict style inventory

- Cost of conflict

- Dialectic

- Dialogue

- Fair fighting

- Family therapy

- Gunnysacking

- Interpersonal communication

- Let the Wookiee win

- Nonviolent Communication

Organizations[edit]

- Center for the Study of Genocide, Conflict Resolution, and Human Rights

- Conscience: Taxes for Peace not War is a London organisation that promotes peacebuilding as an alternative to military security

- Crisis Management Initiative (CMI)

- Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research

- Peninsula Conflict Resolution Center

- Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution

- Search for Common Ground is one of the world’s largest non-government organisations dedicated to conflict resolution

- Seeds of Peace develops and empowers young leaders from regions of conflict to work towards peace through coexistence

- United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY) is a global non-governmental organization and youth network dedicated to the role of youth in peacebuilding and conflict resolution

- University for Peace is a United Nations mandated organization and graduate school dedicated to conflict resolution and peace studies

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program is an academic data collection project that provides descriptions of political violence and conflict resolution

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ For example, in Chinese culture, reasons for avoidance include sustaining a good mood, protecting the avoider, and other philosophical and spiritual reasonings (Feng and Wilson 2011).[full citation needed]

- ^ Nondirective counseling is based on the client-centered therapy of Carl Rogers.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Forsyth, Donelson R. (19 March 2009). Group Dynamics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0495599524.

- ^ Mayer, Bernard (27 March 2012). The Dynamics of Conflict: A Guide to Engagement and Intervention (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0470613535.

- ^ Methods, Conflict Resolution (14 March 2016). «Conflict Resolution». 14 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016 – via wisegeek.

- ^ Rapoport, A. (1989). The origins of violence: Approaches to the study of conflict. New York, NY: Paragon House.

- ^ Rapoport, A. (1992). Peace: An idea whose time has come. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Roberts, Adam; Ash, Timothy Garton, eds. (3 September 2009). Civil Resistance and Power Politics:The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199552016.

- ^ Das, Tuhin K. (2018). «Regret Analysis Towards Conflict Resolution». SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3173490. S2CID 216920077. SSRN 3173490.

- ^ Das, Tuhin K. (2018). «Conflict Resolution Curve: Concept and Reality». SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3196791. S2CID 219337801. SSRN 3196791.

- ^ Das, Tuhin K.; Datta Ray, Ishita (2018). «North Korea’s Peace Building in the Light of Conflict Resolution Curve». SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3193759. SSRN 3193759.

- ^ Goldfien, Jeffrey H.; Robbennolt, Jennifer K. (2007). «What if the lawyers have their way? An empirical assessment of conflict strategies and attitudes toward mediation styles». Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution. 22 (2): 277–320.

- ^ a b c Bayazit, Mahmut; Mannix, Elizabeth A (2003). «Should I stay or should I go? Predicting team members intent to remain in the team.Placed there on purpose with unlieing motives». Small Group Research. 32 (3): 290–321. doi:10.1177/1046496403034003002. S2CID 144220387.

- ^ Morrison, Jeanne (2008). «The relationship between emotional intelligence competencies and preferred conflict-handling styles». Journal of Nursing Management. 16 (8): 974–983. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00876.x. ISSN 1365-2834. PMID 19094110.

- ^ Morrill, Calvin (1995). The Executive Way: Conflict Management in Corporations. Chicago, US: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53873-0. LCCN 94033344.

- ^ Van de Vliert, Evert; Euwema, Martin C. (1994). «Agreeableness and activeness as components of conflict behaviors». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 66 (4): 674–687. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.674. PMID 8189346.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert J.; Dobson, Diane M. (1987). «Resolving interpersonal conflicts: An analysis of stylistic consistency». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (4): 794–812. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.794. ISSN 0022-3514.

- ^ Jarboe, Susan C.; Witteman, Hal R. (1996). «Intragroup conflict management in task-oriented groups: The influence of problem sources and problem analyses». Small Group Research. 27 (2): 316–338. doi:10.1177/1046496496272007. S2CID 145442320.

- ^ Baxter, L. A. (1988). A dialectical perspective of communication strategies in relationship development. In S. Duck. (Ed.) Handbook of personal relationships (pp. 257–273). New York: Wiley.

- ^ Montgomery, Barbara. (1988). «A Dialectical Analysis of the Tensions, Functions and Strategic Challenges of Communication in Young Adult Friendships,»Communication Yearbook 12, ed. James A. Anderson (Newbury, CA: Sage), 157–189.

- ^ Wallensteen, Peter (2015). Understanding conflict resolution (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. p. 57. ISBN 9781473902107. OCLC 900795950.

- ^ Wallensteen, Peter (7 May 2015). Understanding conflict resolution (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles. p. 20. ISBN 9781473902107. OCLC 900795950.

- ^ Allansson, Marie. ««Actors» definition — Department of Peace and Conflict Research — Uppsala University, Sweden». www.pcr.uu.se. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Larson, Jennifer M. (11 May 2021). «Networks of Conflict and Cooperation». Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 89–107. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102523.

- ^ Balcells, Laia; Stanton, Jessica A. (11 May 2021). «Violence Against Civilians During Armed Conflict: Moving Beyond the Macro- and Micro-Level Divide». Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 45–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102229.

- ^ Wallensteen, Peter (7 May 2015). Understanding conflict resolution (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles. p. 17. ISBN 9781473902107. OCLC 900795950.

- ^ Wallensteen, Peter (7 May 2015). Understanding conflict resolution (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles. p. 41. ISBN 9781473902107. OCLC 900795950.

- ^ Wallensteen, Peter (7 May 2015). Understanding conflict resolution (Fourth ed.). Los Angeles. pp. 56–58. ISBN 9781473902107. OCLC 900795950.

- ^ Uppsala Conflict Data Program. «Definitions: Warring party». Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Uppsala Conflict Data Program. «Definitions: Peace agreement». Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Uppsala Conflict Data Program. «Ceasefire agreements». Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Bellamy, Alex J.; Williams, Paul (29 March 2010). Understanding Peacekeeping. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-4186-7.

- ^ McElwee, Timothy A. (2007). «The Role of UN Police in Nonviolently Countering Terrorism». In Ram, Senthil; Summy, Ralph (eds.). Nonviolence: An Alternative for Defeating Global Terror(ism). Nova Science Publishers. pp. 187–210. ISBN 978-1-60021-812-5.

- ^ «Strategic Foresight Group — Anticipating and Influencing Global Future» (PDF). www.strategicforesight.com.

- ^ Lundgren, Magnus (2016). «Conflict management capabilities of peace-brokering international organizations, 1945–2010: A new dataset». Conflict Management and Peace Science. 33 (2): 198–223. doi:10.1177/0738894215572757. S2CID 156002204.

- ^ «conflict». dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ «What is Conflict Resolution, and How Does It Work?». PON — Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. 15 June 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ corissajoy (6 July 2016). «Culture and Conflict». Beyond Intractability. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ «Five Steps to Manage & Resolve Conflict in the Workplace». Experiential. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ «Conflict Resolution: 8 Strategies to Manage Workplace Conflict». Business Know-How. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ «The Five Steps to Conflict Resolution». www.amanet.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Baldoni, John (12 October 2012). «Compromising When Compromise Is Hard». Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Simon; McMillan, John; Woodruff, Christopher (2002). «Courts and Relational Contracts». The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 18 (1): 221–277. doi:10.1093/jleo/18.1.221. ISSN 8756-6222.

- ^ Harmon, Derek J.; Kim, Peter H.; Mayer, Kyle J. (2015). «Breaking the letter vs. spirit of the law: How the interpretation of contract violations affects trust and the management of relationships». Strategic Management Journal. 36 (4): 497–517. doi:10.1002/smj.2231.

- ^ Janowicz‐Panjaitan, Martyna; Krishnan, Rekha (2009). «Measures for Dealing with Competence and Integrity Violations of Interorganizational Trust at the Corporate and Operating Levels of Organizational Hierarchy». Journal of Management Studies. 46 (2): 245–268. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00798.x. ISSN 1467-6486. S2CID 144439444.

- ^ Gaski, John F. (1984). «The Theory of Power and Conflict in Channels of Distribution». Journal of Marketing. 48 (3): 9–29. doi:10.1177/002224298404800303. ISSN 0022-2429. S2CID 168149955.

- ^ Himes, Joseph S. (1 June 2008). Conflict and Conflict Management. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3270-3.

- ^ Knowles, Henry P.; Saxberg, Börje O. (1971). «Chapter 8». Personality and Leadership Behavior. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. ASIN B0014O4YN0. OCLC 118832.

- ^ a b Johnson, Richard Arvid (January 1976). Management, Systems, and Society: An Introduction. Pacific Palisades, Calif.: Goodyear Pub. Co. pp. 148–142. ISBN 978-0-87620-540-2. OCLC 2299496. OL 8091729M.

- ^ Ury, William; Fisher, Roger (1981). Getting To Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-395-31757-0.

- ^ Augsburger, David W. (1992). Conflict Mediation Across Cultures:Pathways and Patterns (1st ed.). Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664219611.

- ^ Okech, Jane E. Atieno; Pimpleton-Gray, Asher M.; Vannatta, Rachel; Champe, Julia (December 2016). «Intercultural Conflict in Groups». Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 41 (4): 350–369. doi:10.1080/01933922.2016.1232769. S2CID 152221705.

- ^ Al-Rodhan, Nayef (30 May 2017). «The ‘ocean model of civilization’, sustainable history theory, and global cultural understanding». British Academy. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017.

- ^ de Waal, Frans B. M. (28 July 2000). «Primates—A natural heritage of conflict resolution». Science. 289 (5479): 586–590. Bibcode:2000Sci…289..586D. doi:10.1126/science.289.5479.586. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10915614. S2CID 15058824.

- ^ Wahaj, Sofia A.; Guse, Kevin R.; Holekamp, Kay E. (December 2001). «Reconciliation in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta)». Ethology. 107 (12): 1057–1074. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0310.2001.00717.x. ISSN 0179-1613.

- ^ Smith, Jennifer E.; Powning, Katherine S.; Dawes, Stephanie E.; Estrada, Jillian R.; Hopper, Adrienne L.; Piotrowski, Stacey L.; Holekamp, Kay E. (February 2011). «Greetings promote cooperation and reinforce social bonds among spotted hyaenas». Animal Behaviour. 81 (2): 401–415. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.11.007. S2CID 2693688.

- ^ Weaver, Ann (October 2003). «Conflict and reconciliation in captive bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus». Marine Mammal Science. 19 (4): 836–846. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2003.tb01134.x.

- ^ Schino, Gabriele (1998). «Reconciliation in domestic goats». Behaviour. 135 (3): 343–356. doi:10.1163/156853998793066302. ISSN 0005-7959. JSTOR 4535531.

- ^ Cools, Annemieke K.A.; Van Hout, Alain J.-M.; Nelissen, Mark H. J. (January 2008). «Canine reconciliation and third-party-initiated postconflict affiliation: Do peacemaking social mechanisms in dogs rival those of higher primates?». Ethology. 114 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2007.01443.x.

- ^ Cordoni, Giada; Norscia, Ivan (29 January 2014). «Peace-making in marsupials: The first study in the red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus)». PLOS One. 9 (1): e86859. Bibcode:2014PLoSO…986859C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086859. PMC 3906073. PMID 24489796.

- ^ University at Waterloo. «Peace and Conflict Studies

- ^ «About Cornell ILR Scheinman Institute». Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ «Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution – Degrees». Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations. 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ «Graduate Program in Conflict Transformation». Eastern Mennonite University’s Center for Justice and Peacebuilding.

- ^ «Guide to MA Program in Peace and Conflict Resolution and Related Fields». Internationalpeaceandconflict.org. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ «Academic Programs | Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution». carterschool.gmu.edu. George Mason University. 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.