When we think of nature journaling, the first things that usually come to mind are colourful nature sketches and watercolour paintings. There is another important area of nature journaling that is, perhaps, a little neglected: The written word.

Writing takes many different forms in a nature journal. We can use it to label sketches, take notes about something we notice or describe a scene. It is possible, also, to use the written word to turn inward a little and reflect on our own thoughts and feelings, the things that move us and how time spent in nature can change the story of our lives. There are many benefits to this form of reflective writing, the most significant being that we learn more about our inner lives and increase the connection with ourselves and with our world.

For those not familiar with the process, reflective and creative writing may feel intimidating at first. Just like it is important not to let fears about art prevent us from creating sketches in our journal, it is important not to feel scared to be creative with words. Poems don’t have to rhyme! Words don’t have to make sense to other people! It is our inner journey which is important here, and the process of reflecting and writing our feelings is always an exercise in connection and growth. Try to let go of self-judgment and criticism and let your inner life flow onto the page through the written word.

Some ways to incorporate reflective and creative writing in your nature journal:

-

Create a poem from your sensory observations.

-

Use simile and metaphor to view common things in a new way.

-

Think about a childhood memory of being in nature. Write about what this experience meant to you.

-

Try transforming factual nature journaling observations into a poem.

-

Reflect on the way you feel emotionally when you are in nature.

-

Try using the common journaling prompts of “I notice…I wonder…It reminds me of…” in response to the feelings and thoughts inside of you instead of something external.

-

Sit in nature and centre yourself in the present moment. Use stream-of-consciousness writing to fill a page in your journal. Write whatever comes to your mind, without judgment or self censorship.

-

Use a sit-spot to connect with a particular place in nature regularly. Visit this place over a period of time and write about your experience here. Some people keep the same sit-spot for decades!

Poetry

Reading a poem is like taking a glimpse into the mind and heart of another person. The power of this is that when a poem speaks to our own personal experience it can make us understand that we are not alone in the things we think and feel. Writing poetry can a joy filled activity. If you need some creative inspiration, take a look at the Poetry section of the Books & Inspiration page. To get started, here is a poem by Emilie Lygren:

FOR THE GRANDMOTHER TEACHING CHILDREN HOW TO PLANT SEEDS

IN THE COMMUNITY GARDEN

“Just a little bit, they only

need to go down an inch,

make a small hole, use your pinkie,

put the seeds in,

gently, gently.”

Elders pass on practice with invocation of earth under fingernails

It doesn’t matter so much if the rows are straight

so long as we remember ourselves.

We can spend a day like this, or a life,

let afternoons pass under

shifting light and swollen clouds.

Plants need no permission, only our exhale,

sunbeams, a thin veil of rain.

How many more hopeful acts do we have left?

After a thousand tragedies,

sleepless nights staring up at the rafters,

the ground beneath

is waiting to begin again,

the seeds will still be true.

For part one of this reflection on nature writing, please see the previous post where I considered what is nature and why do we care about it.

So, having avoided a firm definition of nature, we must next consider another intangible idea, that of nature writing. What is it, what does it look like, how do we know that something is nature writing? And again, we find ourselves without solid ground.

Wikipedia tells us that:

Nature writing is nonfiction or fiction prose or poetry about the natural environment. Nature writing encompasses a wide variety of works, ranging from those that place primary emphasis on natural history facts (such as field guides) to those in which philosophical interpretation predominate. It includes natural history essays, poetry, essays of solitude or escape, as well as travel and adventure writing.

There is no doubt that writings about nature cover a wide range of genres (essays, fiction, poetry etc) but when does writing that includes nature become nature writing. Is, for example, Wind in the Willows an example of nature writing? Is Tess of the D’Urbervilles? The former is based entirely around a community of animals and the latter includes detailed description of the landscape. How much nature must feature in writing in order for it to become nature writing?

We find another description on thoughtco.comthoughtco.com from Richard Nordquist:

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator’s encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

“In critical practice,” says Michael P. Branch, “the term ‘nature writing’ has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice, and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay.

Whilst not a definition, I do like the description that Richard Smyth provides in his commentary Plashy Fens – The Limitations of Nature Writing:

Nature writing is nothing if not the broadest of churches. All human life – and all other life, too – ought to be here: at a time when a troubling homogeneity of sex, race and class prevails in nature writing, diversity of every kind must be welcomed.*

One way of defining nature writing could be in relation to natural history writing, one often considered the scope of amateurs perhaps and the other of professionals. Often nature writing is in first person whereas there is a great stigma around anthropomorphised or personalised writing in academia. This is a way of narrowing the scope but it feels like a line that is, in reality, impossible to find. It also speaks to a hierarchy of nature writers, which in truth does not reflect the readability or enjoyability of the writing itself.

It is possible that we will never truly define nature writing. Indeed, the writers themselves do not seem to have a grasp on what this flimsy phrase means. One of our popular nature writers, Richard Mabey, has said he is confused about what the genre means and Robert MacFarlane has said he would prefer the phrase travel writer. Many are uncomfortable with the term and the loose phrase means that the nuances and variety of the genre are often missed. We must also consider people’s assumptions about the word nature. For many people, this summons up ideas of wilderness and remoteness or great beasts and rare creatures. The use of the word nature can, at surface level, seem to erase the contributions of urban nature writers and can also isolate potential readers who do not feel they would connect with “nature writing” by virtue of not being ‘great outdoorsmen’.

Perhaps purpose and intent have a role to play in sorting out what is nature writing and what is not. Rachel Carson set out to create appreciation of nature in the hope that it would lead to changes in ethical principles and result in social action. And many nature writers do write to share the magic of the world in the hope of making a change in the world. Andrea Nolan in Fiction Writers Review claims that “unlike literary writers, nature writers have a mission statement… to create love in his reader and thus spur them to also love the world.” If this is the case, then is this sufficient enough of a definition? But then what of writers which do not intentionally set out to write nature writing? And what of nature writing which does not have a call to arms or spur to action? Should all nature writing be an appeal to a reader’s conscience or a way of provoking guilt?

Another direction to approach a definition could be through the consideration of content. The Oxford Book of Nature Writing notes that there are recurrent themes, or metaphors, within the genre, in addition of course, to the natural world. These nature based imageries include nature’s breadth and depth, the mysteries of migration, the marvel of adaptation, the cycles we find in nature and the sheer relief that we are not alone on this planet. Whilst not all nature writing will focus on these, it is one way we could perhaps start to include books in the genre, even if we cannot use this as a tool to exclude.

The undefinable being that is nature writing is not even static from country to country. Culture is an important part of the conversation around nature writing. As nature is so vast and changes so much all over the world – think of the extreme difference between rainforest and arctic tundra – what is relevant to one culture’s sense of nature is not necessarily so for another. The wisdom gleamed from nature in one area may not translate well to another. The relationship different cultures have with nature also differ. And this, of course, extends to nature writing. When the journal Ecozon@ was putting together a special on nature writing, they found that “nature writing” was not a category that translated easily in the rest of Europe:

“The lone writer making trips into the countryside for personal epiphanies of engagement or enlightenment was not a common mode of literary production in mainland Europe.”

The boundaries around nature writing are loose and changeable. Perhaps, like nature itself, nature writing is a case of you know it when you read it? Or perhaps it is not really a genre at all, just a construct which helps writers and publishers who feel a need to categorise.

In my next post I will look at nature writing through history.

*Diversity within nature writing is a topic I will be returning to, especially in regards to women and the voice of the disabled nature writer. Much of our “wilderness” is inaccessible to many people still and the emphasis on wild over urban nature excludes those of us who are disabled, as well, obviously, as those who are city dwellers.

When recruiting for a Personal Assistant in 2019, Pallant House Gallery director Simon Martin was inspired by one interviewee’s enthusiastic response to a set task of speaking about their favourite work of art. The chosen work was Eric Ravilious’ wood engraving Hoopoes from The Writings of Gilbert White, and it planted the seed of an idea for an exhibition: a display of the modern illustrators of Revd. Gilbert White’s much-loved book, Natural History of Selborne, which would celebrate White’s lasting influence on artists.

The exhibition was planned for the following year – 2020 – to coincide with the tercentenary of White’s birth, but the outbreak of the Covid pandemic meant that the Gallery had to be closed to the public only three days after the exhibition opened. Undeterred by this inauspicious start, Simon Martin resolved to ensure that those who wanted to experience the beauty of the exhibition’s historic prints and newly-commissioned works by contemporary artists and illustrators would still be able to do so. He wrote a book.

Simon Martin writes…

Since its publication in 1789, Gilbert White’s Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne has inspired generations of artists, writers and naturalists. From Thomas Bewick to Clare Leighton, many artists’ depictions of animals, birds and wildlife have illustrated White’s celebrated book, together creating a microcosm of natural history illustration. Writing a book about the artists who have illustrated White’s Natural History was not something I originally set out to do, but it has been an immensely rewarding outcome of circumstances created by the Covid pandemic.

Natural history and the art of poetry

I must confess that whilst it was visual art that started my journey into White’s Selborne, this point of entry led me into a study of nature: endlessly cross-referencing photographs of different species with artists’ depictions and White’s descriptions, reading and re-reading certain passages. It is easy to see why poets such as W.H. Auden, John Clare and Samuel Taylor Coleridge have admired the naturalist’s turn-of-phrase. White used vivid poetic analogies, observations such as ‘vast, swaggering, rock-like clouds’ and rooks making ‘a pleasing murmur…not unlike the cry of a pack of hounds in hollow echoing woods, or the rushing of the wind in tall trees, or the tumbling of the tide upon a pebbly shore’. Such descriptions were the perfect brief for artists and illustrators.

Memorably, the modernist writer Virginia Woolf declared how, ‘By some apparently unconscious device of the author has a door been left open, through which we hear distant sounds, a dog barking, cart-wheels creaking’. After searching out her beautiful and perceptive essay ‘White’s Selborne’, first published in the New Statesman in September 1939, I was surprised to learn that it had hardly been republished, except in her Collected Writings, and I was determined that if I was able to bring together many of the modern illustrators that this should also be included. Similarly, W.H. Auden’s Posthumous Letter to Gilbert White, first published in the New York Review in 1973, is included together with some of White’s own poems, as well as contemporary poems by Kathryn Bevis and Jo Bell. Fortunately, Sir David Attenborough kindly agreed to us reprinting his thoughtful 1977 essay in which he describes White as a man ‘in total harmony with his world’.

Focusing on 20th-century artists

Setting out to record a visual history of a book is not without its challenges, especially during a pandemic when libraries and archives are closed. Every week multiple parcels would arrive as I bought myself more and more books (partly as research and partly to cheer myself up in the months of lockdown), not just editions of White, but biographies and other books on nature illustrated by the artists I was studying. With so many editions, it became a question of where to draw the line, and I came to dread discovering yet another edition after it became too late to include it. Inevitably the primary focus was on 20th century artists, and particularly those working in wood-engraved illustration, a medium particularly suited to natural history book illustration. These included some of the greatest exponents of the medium: Eric Fitch Daglish, Gertrude Hermes, Eric Ravilious, Agnes Miller Parker, Clare Leighton, Christopher Wormell. Each of these artists looked back to the engravings of birds and animals by Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). Painter-printmaker John Piper had even gifted an 1875 edition of the Natural History with illustrations ascribed to Bewick as courtship gift to his wife Myfanwy.

Thomas Bewick: founding father of British wood-engraving

Thomas Bewick had apparently loved White’s Selborne. The first volume of his A History of British Birds, published in 1797, presented a list of nineteen birds which were ‘chiefly selected from Mr. White’s Natural History of Selborne, and are arranged nearly in the order of their appearing’. So, it was disappointing to discover during the course of my research that Bewick had never actually illustrated White’s book, but rather that several of his vignettes were later copied as headpieces and tailpieces for numerous Victorian editions of White’s book. Such is the stuff of detailed footnotes, but many hours were spent comparing images from Bewick’s History of British Birds and the images made after him by the likes of his pupils John Thompson, John Jackson and Charlton Nesbit. What is undeniable is that White and Bewick shared an affinity of approach: both were recorders of the minutiae of country life and precise observers of birds and animals, White in prose and Bewick in his carefully-crafted illustrations. Acknowledged as the founding father of British wood-engraving, Bewick’s birds and animals were an important influence in the 1930s and 40s on the printmakers in the book. Whilst I knew quite a bit about many of these artists, I was intrigued by an almost unrecorded artist called Claire Oldham, who had illustrated a particularly lovely edition in 1947. Through genealogical searches on ancestry websites and articles in 1940s issues of The Studio, I was able to ascertain her life-dates; and discovered that she was actually the niece of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, and had lived in the South Downs.

The challenges of editing (and Timothy the tortoise)

Editing also became an immense challenge: how to standardise spellings across several centuries; should we use capitals or lower case for Linnean names, even when what White used was technically incorrect today? Although the book inevitably features an array of hedgehogs, a kettle of swallows, a parliament of owls, a nest of mice, and a cry of hoopoes, each depiction has its own character and identity that stops it ever becoming repetitive, at least to my eyes. Inevitably there is a creep of tortoises as so many artists have been drawn to the humorous qualities of White’s pet Timothy, as indeed was the poet Sylvia Townsend Warner.

It was a source of great frustration that the cover illustration on her 1946 compendium The Portrait of a Tortoise, extracted from White’s letters, was not credited anywhere. However, thanks to helpful researchers at the University of Reading and Chatto and Windus archives I was able to positively confirm my identification of Irene Hawkins as the artist. In such a way many hours were spent on checking up the kinds of footnote arguments that few notice, but hopefully the end result is something that will stand the test of time and be a contribution to the impressive scholarship on Gilbert White and on British natural history illustration. It has been hugely rewarding to receive kind comments from the likes of Richard Mabey and Alexandra Harris, and – perhaps most of all – to hear that Sir David Attenborough wanted 36 copies to give to his family and friends!

Drawn to Nature brings together depictions of British wildlife from the 18th century to today, inspired by Gilbert White’s Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. Find out more.

Distributed for Pallant Publications

Celebrate summer with 30% off* a selection of art titles that capture the beauty of the natural world.

Click here to browse the full list of books included in this limited-time offer. Enter promo code DRAWN when prompted during the checkout process to redeem the 30% discount.

*Subject to availability. UK orders only. Free P&P. Code valid until 24/09/2022.

Nature Writing Used the Environment As a Major Subject.

PamelaJoeMcFarlane/Getty Images

Updated on April 14, 2017

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator’s encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

«In critical practice,» says Michael P. Branch, «the term ‘nature writing’ has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice, and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay. Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda» («Before Nature Writing,» in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism, ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001).

Examples of Nature Writing:

- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:

- «Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . ..

«The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs, literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . .

«In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir’s words, that ‘the money changers were in the temple’ continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature’s wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs.

«Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing.»

(J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing. Norton, 2002)

«Human Writing . . . in Nature»

- «By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really ‘nature writing’ anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau’s] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There’s something to celebrate.» (David Gessner, «Sick of Nature.» The Boston Globe, Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer

- «I do not believe that the solution to the world’s ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature

«Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a ‘nature writer’ is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that ‘nature never did betray the heart that loved her.’ Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. ‘Nature writing’ is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically ‘nature writing’ does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things.»

(Joseph Wood Krutch, «Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer.» New York Herald Tribune Book Review, 1952)

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. «Nature» can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are part of nature, human activity is often understood as a separate category from other natural phenomena.[1]

The word nature is borrowed from the Old French nature and is derived from the Latin word natura, or «essential qualities, innate disposition», and in ancient times, literally meant «birth».[2] In ancient philosophy, natura is mostly used as the Latin translation of the Greek word physis (φύσις), which originally related to the intrinsic characteristics of plants, animals, and other features of the world to develop of their own accord.[3][4]

The concept of nature as a whole, the physical universe, is one of several expansions of the original notion;[1] it began with certain core applications of the word φύσις by pre-Socratic philosophers (though this word had a dynamic dimension then, especially for Heraclitus), and has steadily gained currency ever since.

During the advent of modern scientific method in the last several centuries, nature became the passive reality, organized and moved by divine laws.[5][6] With the Industrial revolution, nature increasingly became seen as the part of reality deprived from intentional intervention: it was hence considered as sacred by some traditions (Rousseau, American transcendentalism) or a mere decorum for divine providence or human history (Hegel, Marx). However, a vitalist vision of nature, closer to the pre-Socratic one, got reborn at the same time, especially after Charles Darwin.[1]

Within the various uses of the word today, «nature» often refers to geology and wildlife. Nature can refer to the general realm of living plants and animals, and in some cases to the processes associated with inanimate objects—the way that particular types of things exist and change of their own accord, such as the weather and geology of the Earth. It is often taken to mean the «natural environment» or wilderness—wild animals, rocks, forest, and in general those things that have not been substantially altered by human intervention, or which persist despite human intervention. For example, manufactured objects and human interaction generally are not considered part of nature, unless qualified as, for example, «human nature» or «the whole of nature». This more traditional concept of natural things that can still be found today implies a distinction between the natural and the artificial, with the artificial being understood as that which has been brought into being by a human consciousness or a human mind. Depending on the particular context, the term «natural» might also be distinguished from the unnatural or the supernatural.[1]

Earth

Earth is the only planet known to support life, and its natural features are the subject of many fields of scientific research. Within the Solar System, it is third closest to the Sun; it is the largest terrestrial planet and the fifth largest overall. Its most prominent climatic features are its two large polar regions, two relatively narrow temperate zones, and a wide equatorial tropical to subtropical region.[7] Precipitation varies widely with location, from several metres of water per year to less than a millimetre. 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by salt-water oceans. The remainder consists of continents and islands, with most of the inhabited land in the Northern Hemisphere.

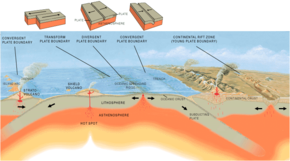

Earth has evolved through geological and biological processes that have left traces of the original conditions. The outer surface is divided into several gradually migrating tectonic plates. The interior remains active, with a thick layer of plastic mantle and an iron-filled core that generates a magnetic field. This iron core is composed of a solid inner phase, and a fluid outer phase. Convective motion in the core generates electric currents through dynamo action, and these, in turn, generate the geomagnetic field.

The atmospheric conditions have been significantly altered from the original conditions by the presence of life-forms,[8] which create an ecological balance that stabilizes the surface conditions. Despite the wide regional variations in climate by latitude and other geographic factors, the long-term average global climate is quite stable during interglacial periods,[9] and variations of a degree or two of average global temperature have historically had major effects on the ecological balance, and on the actual geography of the Earth.[10][11]

Geology

Geology is the science and study of the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth. The field of geology encompasses the study of the composition, structure, physical properties, dynamics, and history of Earth materials, and the processes by which they are formed, moved, and changed. The field is a major academic discipline, and is also important for mineral and hydrocarbon extraction, knowledge about and mitigation of natural hazards, some Geotechnical engineering fields, and understanding past climates and environments.

Geological evolution

The geology of an area evolves through time as rock units are deposited and inserted and deformational processes change their shapes and locations.

Rock units are first emplaced either by deposition onto the surface or intrude into the overlying rock. Deposition can occur when sediments settle onto the surface of the Earth and later lithify into sedimentary rock, or when as volcanic material such as volcanic ash or lava flows, blanket the surface. Igneous intrusions such as batholiths, laccoliths, dikes, and sills, push upwards into the overlying rock, and crystallize as they intrude.

After the initial sequence of rocks has been deposited, the rock units can be deformed and/or metamorphosed. Deformation typically occurs as a result of horizontal shortening, horizontal extension, or side-to-side (strike-slip) motion. These structural regimes broadly relate to convergent boundaries, divergent boundaries, and transform boundaries, respectively, between tectonic plates.

Historical perspective

An animation showing the movement of the continents from the separation of Pangaea until the present day

Earth is estimated to have formed 4.54 billion years ago from the solar nebula, along with the Sun and other planets.[12] The Moon formed roughly 20 million years later. Initially molten, the outer layer of the Earth cooled, resulting in the solid crust. Outgassing and volcanic activity produced the primordial atmosphere. Condensing water vapor, most or all of which came from ice delivered by comets, produced the oceans and other water sources.[13] The highly energetic chemistry is believed to have produced a self-replicating molecule around 4 billion years ago.[14]

Plankton inhabit oceans, seas and lakes, and have existed in various forms for at least 2 billion years[15]

Continents formed, then broke up and reformed as the surface of Earth reshaped over hundreds of millions of years, occasionally combining to make a supercontinent. Roughly 750 million years ago, the earliest known supercontinent Rodinia, began to break apart. The continents later recombined to form Pannotia which broke apart about 540 million years ago, then finally Pangaea, which broke apart about 180 million years ago.[16]

During the Neoproterozoic era, freezing temperatures covered much of the Earth in glaciers and ice sheets. This hypothesis has been termed the «Snowball Earth», and it is of particular interest as it precedes the Cambrian explosion in which multicellular life forms began to proliferate about 530–540 million years ago.[17]

Since the Cambrian explosion there have been five distinctly identifiable mass extinctions.[18] The last mass extinction occurred some 66 million years ago, when a meteorite collision probably triggered the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and other large reptiles, but spared small animals such as mammals. Over the past 66 million years, mammalian life diversified.[19]

Several million years ago, a species of small African ape gained the ability to stand upright.[15] The subsequent advent of human life, and the development of agriculture and further civilization allowed humans to affect the Earth more rapidly than any previous life form, affecting both the nature and quantity of other organisms as well as global climate. By comparison, the Great Oxygenation Event, produced by the proliferation of algae during the Siderian period, required about 300 million years to culminate.

The present era is classified as part of a mass extinction event, the Holocene extinction event, the fastest ever to have occurred.[20][21] Some, such as E. O. Wilson of Harvard University, predict that human destruction of the biosphere could cause the extinction of one-half of all species in the next 100 years.[22] The extent of the current extinction event is still being researched, debated and calculated by biologists.[23][24][25]

Atmosphere, climate, and weather

The Earth’s atmosphere is a key factor in sustaining the ecosystem. The thin layer of gases that envelops the Earth is held in place by gravity. Air is mostly nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, with much smaller amounts of carbon dioxide, argon, etc. The atmospheric pressure declines steadily with altitude. The ozone layer plays an important role in depleting the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation that reaches the surface. As DNA is readily damaged by UV light, this serves to protect life at the surface. The atmosphere also retains heat during the night, thereby reducing the daily temperature extremes.

Terrestrial weather occurs almost exclusively in the lower part of the atmosphere, and serves as a convective system for redistributing heat.[26] Ocean currents are another important factor in determining climate, particularly the major underwater thermohaline circulation which distributes heat energy from the equatorial oceans to the polar regions. These currents help to moderate the differences in temperature between winter and summer in the temperate zones. Also, without the redistributions of heat energy by the ocean currents and atmosphere, the tropics would be much hotter, and the polar regions much colder.

Weather can have both beneficial and harmful effects. Extremes in weather, such as tornadoes or hurricanes and cyclones, can expend large amounts of energy along their paths, and produce devastation. Surface vegetation has evolved a dependence on the seasonal variation of the weather, and sudden changes lasting only a few years can have a dramatic effect, both on the vegetation and on the animals which depend on its growth for their food.

Climate is a measure of the long-term trends in the weather. Various factors are known to influence the climate, including ocean currents, surface albedo, greenhouse gases, variations in the solar luminosity, and changes to the Earth’s orbit. Based on historical records, the Earth is known to have undergone drastic climate changes in the past, including ice ages.

The climate of a region depends on a number of factors, especially latitude. A latitudinal band of the surface with similar climatic attributes forms a climate region. There are a number of such regions, ranging from the tropical climate at the equator to the polar climate in the northern and southern extremes. Weather is also influenced by the seasons, which result from the Earth’s axis being tilted relative to its orbital plane. Thus, at any given time during the summer or winter, one part of the Earth is more directly exposed to the rays of the sun. This exposure alternates as the Earth revolves in its orbit. At any given time, regardless of season, the Northern and Southern Hemispheres experience opposite seasons.

Weather is a chaotic system that is readily modified by small changes to the environment, so accurate weather forecasting is limited to only a few days.[27] Overall, two things are happening worldwide: (1) temperature is increasing on the average; and (2) regional climates have been undergoing noticeable changes.[28]

Water on the Earth

Water is a chemical substance that is composed of hydrogen and oxygen (H2O) and is vital for all known forms of life.[29] In typical usage, water refers only to its liquid form or state, but the substance also has a solid state, ice, and a gaseous state, water vapor, or steam. Water covers 71% of the Earth’s surface.[30] On Earth, it is found mostly in oceans and other large bodies of water, with 1.6% of water below ground in aquifers and 0.001% in the air as vapor, clouds, and precipitation.[31][32] Oceans hold 97% of surface water, glaciers, and polar ice caps 2.4%, and other land surface water such as rivers, lakes, and ponds 0.6%. Additionally, a minute amount of the Earth’s water is contained within biological bodies and manufactured products.

Oceans

A view of the Atlantic Ocean from Leblon, Rio de Janeiro

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth’s surface (an area of some 361 million square kilometers) is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas. More than half of this area is over 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) deep. Average oceanic salinity is around 35 parts per thousand (ppt) (3.5%), and nearly all seawater has a salinity in the range of 30 to 38 ppt. Though generally recognized as several ‘separate’ oceans, these waters comprise one global, interconnected body of salt water often referred to as the World Ocean or global ocean.[33][34] This concept of a global ocean as a continuous body of water with relatively free interchange among its parts is of fundamental importance to oceanography.[35]

The major oceanic divisions are defined in part by the continents, various archipelagos, and other criteria: these divisions are (in descending order of size) the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and the Arctic Ocean. Smaller regions of the oceans are called seas, gulfs, bays and other names. There are also salt lakes, which are smaller bodies of landlocked saltwater that are not interconnected with the World Ocean. Two notable examples of salt lakes are the Aral Sea and the Great Salt Lake.

Lakes

Main article: Lake

A lake (from Latin word lacus) is a terrain feature (or physical feature), a body of liquid on the surface of a world that is localized to the bottom of basin (another type of landform or terrain feature; that is, it is not global) and moves slowly if it moves at all. On Earth, a body of water is considered a lake when it is inland, not part of the ocean, is larger and deeper than a pond, and is fed by a river.[36][37] The only world other than Earth known to harbor lakes is Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, which has lakes of ethane, most likely mixed with methane. It is not known if Titan’s lakes are fed by rivers, though Titan’s surface is carved by numerous river beds. Natural lakes on Earth are generally found in mountainous areas, rift zones, and areas with ongoing or recent glaciation. Other lakes are found in endorheic basins or along the courses of mature rivers. In some parts of the world, there are many lakes because of chaotic drainage patterns left over from the last ice age. All lakes are temporary over geologic time scales, as they will slowly fill in with sediments or spill out of the basin containing them.

Ponds

Main article: Pond

A pond is a body of standing water, either natural or man-made, that is usually smaller than a lake. A wide variety of man-made bodies of water are classified as ponds, including water gardens designed for aesthetic ornamentation, fish ponds designed for commercial fish breeding, and solar ponds designed to store thermal energy. Ponds and lakes are distinguished from streams via current speed. While currents in streams are easily observed, ponds and lakes possess thermally driven micro-currents and moderate wind driven currents. These features distinguish a pond from many other aquatic terrain features, such as stream pools and tide pools.

Rivers

A river is a natural watercourse,[38] usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, a lake, a sea or another river. In a few cases, a river simply flows into the ground or dries up completely before reaching another body of water. Small rivers may also be called by several other names, including stream, creek, brook, rivulet, and rill; there is no general rule that defines what can be called a river. Many names for small rivers are specific to geographic location; one example is Burn in Scotland and North-east England. Sometimes a river is said to be larger than a creek, but this is not always the case, due to vagueness in the language.[39] A river is part of the hydrological cycle. Water within a river is generally collected from precipitation through surface runoff, groundwater recharge, springs, and the release of stored water in natural ice and snowpacks (i.e., from glaciers).

Streams

A stream is a flowing body of water with a current, confined within a bed and stream banks. In the United States, a stream is classified as a watercourse less than 60 feet (18 metres) wide. Streams are important as conduits in the water cycle, instruments in groundwater recharge, and they serve as corridors for fish and wildlife migration. The biological habitat in the immediate vicinity of a stream is called a riparian zone. Given the status of the ongoing Holocene extinction, streams play an important corridor role in connecting fragmented habitats and thus in conserving biodiversity. The study of streams and waterways in general involves many branches of inter-disciplinary natural science and engineering, including hydrology, fluvial geomorphology, aquatic ecology, fish biology, riparian ecology, and others.

Ecosystems

Loch Lomond in Scotland forms a relatively isolated ecosystem. The fish community of this lake has remained unchanged over a very long period of time.[40]

Ecosystems are composed of a variety of biotic and abiotic components that function in an interrelated way.[41] The structure and composition is determined by various environmental factors that are interrelated. Variations of these factors will initiate dynamic modifications to the ecosystem. Some of the more important components are soil, atmosphere, radiation from the sun, water, and living organisms.

Central to the ecosystem concept is the idea that living organisms interact with every other element in their local environment. Eugene Odum, a founder of ecology, stated: «Any unit that includes all of the organisms (ie: the «community») in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity, and material cycles (i.e.: exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system is an ecosystem.»[42] Within the ecosystem, species are connected and dependent upon one another in the food chain, and exchange energy and matter between themselves as well as with their environment.[43] The human ecosystem concept is based on the human/nature dichotomy and the idea that all species are ecologically dependent on each other, as well as with the abiotic constituents of their biotope.[44]

A smaller unit of size is called a microecosystem. For example, a microsystem can be a stone and all the life under it. A macroecosystem might involve a whole ecoregion, with its drainage basin.[45]

Wilderness

Wilderness is generally defined as areas that have not been significantly modified by human activity. Wilderness areas can be found in preserves, estates, farms, conservation preserves, ranches, national forests, national parks, and even in urban areas along rivers, gulches, or otherwise undeveloped areas. Wilderness areas and protected parks are considered important for the survival of certain species, ecological studies, conservation, and solitude. Some nature writers believe wilderness areas are vital for the human spirit and creativity,[46] and some ecologists consider wilderness areas to be an integral part of the Earth’s self-sustaining natural ecosystem (the biosphere). They may also preserve historic genetic traits and that they provide habitat for wild flora and fauna that may be difficult or impossible to recreate in zoos, arboretums, or laboratories.

Life

Female mallard and ducklings – reproduction is essential for continuing life

Although there is no universal agreement on the definition of life, scientists generally accept that the biological manifestation of life is characterized by organization, metabolism, growth, adaptation, response to stimuli, and reproduction.[47] Life may also be said to be simply the characteristic state of organisms.

Properties common to terrestrial organisms (plants, animals, fungi, protists, archaea, and bacteria) are that they are cellular, carbon-and-water-based with complex organization, having a metabolism, a capacity to grow, respond to stimuli, and reproduce. An entity with these properties is generally considered life. However, not every definition of life considers all of these properties to be essential. Human-made analogs of life may also be considered to be life.

The biosphere is the part of Earth’s outer shell—including land, surface rocks, water, air and the atmosphere—within which life occurs, and which biotic processes in turn alter or transform. From the broadest geophysiological point of view, the biosphere is the global ecological system integrating all living beings and their relationships, including their interaction with the elements of the lithosphere (rocks), hydrosphere (water), and atmosphere (air). The entire Earth contains over 75 billion tons (150 trillion pounds or about 6.8×1013 kilograms) of biomass (life), which lives within various environments within the biosphere.[48]

Over nine-tenths of the total biomass on Earth is plant life, on which animal life depends very heavily for its existence.[49] More than 2 million species of plant and animal life have been identified to date,[50] and estimates of the actual number of existing species range from several million to well over 50 million.[51][52][53] The number of individual species of life is constantly in some degree of flux, with new species appearing and others ceasing to exist on a continual basis.[54][55] The total number of species is in rapid decline.[56][57][58]

Evolution

The origin of life on Earth is not well understood, but it is known to have occurred at least 3.5 billion years ago,[61][62][63] during the hadean or archean eons on a primordial Earth that had a substantially different environment than is found at present.[64] These life forms possessed the basic traits of self-replication and inheritable traits. Once life had appeared, the process of evolution by natural selection resulted in the development of ever-more diverse life forms.

Species that were unable to adapt to the changing environment and competition from other life forms became extinct. However, the fossil record retains evidence of many of these older species. Current fossil and DNA evidence shows that all existing species can trace a continual ancestry back to the first primitive life forms.[64]

When basic forms of plant life developed the process of photosynthesis the sun’s energy could be harvested to create conditions which allowed for more complex life forms.[65] The resultant oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere and gave rise to the ozone layer. The incorporation of smaller cells within larger ones resulted in the development of yet more complex cells called eukaryotes.[66] Cells within colonies became increasingly specialized, resulting in true multicellular organisms. With the ozone layer absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation, life colonized the surface of Earth.

Microbes

The first form of life to develop on the Earth were microbes, and they remained the only form of life until about a billion years ago when multi-cellular organisms began to appear.[67] Microorganisms are single-celled organisms that are generally microscopic, and smaller than the human eye can see. They include Bacteria, Fungi, Archaea, and Protista.

These life forms are found in almost every location on the Earth where there is liquid water, including in the Earth’s interior.[68]

Their reproduction is both rapid and profuse. The combination of a high mutation rate and a horizontal gene transfer[69] ability makes them highly adaptable, and able to survive in new environments, including outer space.[70] They form an essential part of the planetary ecosystem. However, some microorganisms are pathogenic and can post health risk to other organisms.

Plants and animals

Originally Aristotle divided all living things between plants, which generally do not move fast enough for humans to notice, and animals. In Linnaeus’ system, these became the kingdoms Vegetabilia (later Plantae) and Animalia. Since then, it has become clear that the Plantae as originally defined included several unrelated groups, and the fungi and several groups of algae were removed to new kingdoms. However, these are still often considered plants in many contexts. Bacterial life is sometimes included in flora,[71][72] and some classifications use the term bacterial flora separately from plant flora.

Among the many ways of classifying plants are by regional floras, which, depending on the purpose of study, can also include fossil flora, remnants

of plant life from a previous era. People in many regions and countries take great pride in their individual arrays of characteristic flora, which can vary widely across the globe due to differences in climate and terrain.

Regional floras commonly are divided into categories such as native flora and agricultural and garden flora, the lastly mentioned of which are intentionally grown and cultivated. Some types of «native flora» actually have been introduced centuries ago by people migrating from one region or continent to another, and become an integral part of the native, or natural flora of the place to which they were introduced. This is an example of how human interaction with nature can blur the boundary of what is considered nature.

Another category of plant has historically been carved out for weeds. Though the term has fallen into disfavor among botanists as a formal way to categorize «useless» plants, the informal use of the word «weeds» to describe those plants that are deemed worthy of elimination is illustrative of the general tendency of people and societies to seek to alter or shape the course of nature. Similarly, animals are often categorized in ways such as domestic, farm animals, wild animals, pests, etc. according to their relationship to human life.

Animals as a category have several characteristics that generally set them apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and usually multicellular (although see Myxozoa), which separates them from bacteria, archaea, and most protists. They are heterotrophic, generally digesting food in an internal chamber, which separates them from plants and algae. They are also distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls.

With a few exceptions—most notably the two phyla consisting of sponges and placozoans—animals have bodies that are differentiated into tissues. These include muscles, which are able to contract and control locomotion, and a nervous system, which sends and processes signals. There is also typically an internal digestive chamber. The eukaryotic cells possessed by all animals are surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins. This may be calcified to form structures like shells, bones, and spicules, a framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganized during development and maturation, and which supports the complex anatomy required for mobility.

Human interrelationship

Human impact

Although humans comprise only a minuscule proportion of the total living biomass on Earth, the human effect on nature is disproportionately large. Because of the extent of human influence, the boundaries between what humans regard as nature and «made environments» is not clear cut except at the extremes. Even at the extremes, the amount of natural environment that is free of discernible human influence is diminishing at an increasingly rapid pace. A 2020 study published in Nature found that anthropogenic mass (human-made materials) outweighs all living biomass on earth, with plastic alone exceeding the mass of all land and marine animals combined.[73] And according to a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, only about 3% of the planet’s terrestrial surface is ecologically and faunally intact, with a low human footprint and healthy populations of native animal species.[74][75]

The development of technology by the human race has allowed the greater exploitation of natural resources and has helped to alleviate some of the risk from natural hazards. In spite of this progress, however, the fate of human civilization remains closely linked to changes in the environment. There exists a highly complex feedback loop between the use of advanced technology and changes to the environment that are only slowly becoming understood.[76] Man-made threats to the Earth’s natural environment include pollution, deforestation, and disasters such as oil spills. Humans have contributed to the extinction of many plants and animals,[77] with roughly 1 million species threatened with extinction within decades.[78] The loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functions over the last half century have impacted the extent that nature can contribute to human quality of life,[79] and continued declines could pose a major threat to the continued existence of human civilization, unless a rapid course correction is made.[80] The value of natural resources to human society is not reflected in market prices because mostly natural resources are available free of charge. This distorts market pricing of natural resources and at the same time leads to underinvestment in our natural assets. The annual global cost of public subsidies that damage nature is conservatively estimated at $4–$6 trillion (million million). Institutional protections of these natural goods, such as the oceans and rainforests, are lacking. Governments have not prevented these economic externalities.[81][82]

Humans employ nature for both leisure and economic activities. The acquisition of natural resources for industrial use remains a sizable component of the world’s economic system.[83][84] Some activities, such as hunting and fishing, are used for both sustenance and leisure, often by different people. Agriculture was first adopted around the 9th millennium BCE. Ranging from food production to energy, nature influences economic wealth.

Although early humans gathered uncultivated plant materials for food and employed the medicinal properties of vegetation for healing,[85] most modern human use of plants is through agriculture. The clearance of large tracts of land for crop growth has led to a significant reduction in the amount available of forestation and wetlands, resulting in the loss of habitat for many plant and animal species as well as increased erosion.[86]

Aesthetics and beauty

Aesthetically pleasing flowers

Beauty in nature has historically been a prevalent theme in art and books, filling large sections of libraries and bookstores. That nature has been depicted and celebrated by so much art, photography, poetry, and other literature shows the strength with which many people associate nature and beauty. Reasons why this association exists, and what the association consists of, are studied by the branch of philosophy called aesthetics. Beyond certain basic characteristics that many philosophers agree about to explain what is seen as beautiful, the opinions are virtually endless.[87] Nature and wildness have been important subjects in various eras of world history. An early tradition of landscape art began in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). The tradition of representing nature as it is became one of the aims of Chinese painting and was a significant influence in Asian art.

Although natural wonders are celebrated in the Psalms and the Book of Job, wilderness portrayals in art became more prevalent in the 1800s, especially in the works of the Romantic movement. British artists John Constable and J. M. W. Turner turned their attention to capturing the beauty of the natural world in their paintings. Before that, paintings had been primarily of religious scenes or of human beings. William Wordsworth’s poetry described the wonder of the natural world, which had formerly been viewed as a threatening place. Increasingly the valuing of nature became an aspect of Western culture.[88] This artistic movement also coincided with the Transcendentalist movement in the Western world. A common classical idea of beautiful art involves the word mimesis, the imitation of nature. Also in the realm of ideas about beauty in nature is that the perfect is implied through perfect mathematical forms and more generally by patterns in nature. As David Rothenburg writes, «The beautiful is the root of science and the goal of art, the highest possibility that humanity can ever hope to see».[89]: 281

Matter and energy

Some fields of science see nature as matter in motion, obeying certain laws of nature which science seeks to understand. For this reason the most fundamental science is generally understood to be «physics»—the name for which is still recognizable as meaning that it is the «study of nature«.

Matter is commonly defined as the substance of which physical objects are composed. It constitutes the observable universe. The visible components of the universe are now believed to compose only 4.9 percent of the total mass. The remainder is believed to consist of 26.8 percent cold dark matter and 68.3 percent dark energy.[90] The exact arrangement of these components is still unknown and is under intensive investigation by physicists.

The behaviour of matter and energy throughout the observable universe appears to follow well-defined physical laws. These laws have been employed to produce cosmological models that successfully explain the structure and the evolution of the universe we can observe. The mathematical expressions of the laws of physics employ a set of twenty physical constants[91] that appear to be static across the observable universe.[92] The values of these constants have been carefully measured, but the reason for their specific values remains a mystery.

Beyond Earth

Outer space, also simply called space, refers to the relatively empty regions of the Universe outside the atmospheres of celestial bodies. Outer space is used to distinguish it from airspace (and terrestrial locations). There is no discrete boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and space, as the atmosphere gradually attenuates with increasing altitude. Outer space within the Solar System is called interplanetary space, which passes over into interstellar space at what is known as the heliopause.

Outer space is sparsely filled with several dozen types of organic molecules discovered to date by microwave spectroscopy, blackbody radiation left over from the Big Bang and the origin of the universe, and cosmic rays, which include ionized atomic nuclei and various subatomic particles. There is also some gas, plasma and dust, and small meteors. Additionally, there are signs of human life in outer space today, such as material left over from previous crewed and uncrewed launches which are a potential hazard to spacecraft. Some of this debris re-enters the atmosphere periodically.

Although Earth is the only body within the Solar System known to support life, evidence suggests that in the distant past the planet Mars possessed bodies of liquid water on the surface.[93] For a brief period in Mars’ history, it may have also been capable of forming life. At present though, most of the water remaining on Mars is frozen.

If life exists at all on Mars, it is most likely to be located underground where liquid water can still exist.[94]

Conditions on the other terrestrial planets, Mercury and Venus, appear to be too harsh to support life as we know it. But it has been conjectured that Europa, the fourth-largest moon of Jupiter, may possess a sub-surface ocean of liquid water and could potentially host life.[95]

Astronomers have started to discover extrasolar Earth analogs – planets that lie in the habitable zone of space surrounding a star, and therefore could possibly host life as we know it.[96]

See also

- Force of nature

- Human nature

- Natural history

- Naturalism

- Natural landscape

- Natural law

- Natural resource

- Natural science

- Natural theology

- Nature reserve

- Nature versus nurture

- Nature worship

- Naturism

- Rewilding

Media:

- National Wildlife, a publication of the National Wildlife Federation

- Natural History, by Pliny the Elder

- Natural World (TV series)

- Nature, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Nature, a prominent scientific journal

- Nature (TV series)

- The World We Live In (Life magazine)

Organizations:

- Nature Detectives

- The Nature Conservancy

Philosophy:

- Balance of nature (biological fallacy), a discredited concept of natural equilibrium in predator–prey dynamics

- Mother Nature

- Naturalism, any of several philosophical stances, typically those descended from materialism and pragmatism that do not distinguish the supernatural from nature;[97] this includes the methodological naturalism of natural science, which makes the methodological assumption that observable events in nature are explained only by natural causes, without assuming either the existence or non-existence of the supernatural

- Nature (philosophy)

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). «What does ‘nature’ mean?». Palgrave Communications. Springer Nature. 6 (14). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «nature». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ An account of the pre-Socratic use of the concept of φύσις may be found in Naddaf, Gerard (2006) The Greek Concept of Nature, SUNY Press, and in Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). «What does ‘nature’ mean?». Palgrave Communications. Springer Nature. 6 (14). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.. The word φύσις, while first used in connection with a plant in Homer, occurs early in Greek philosophy, and in several senses. Generally, these senses match rather well the current senses in which the English word nature is used, as confirmed by Guthrie, W.K.C. Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus (volume 2 of his History of Greek Philosophy), Cambridge UP, 1965.

- ^ The first known use of physis was by Homer in reference to the intrinsic qualities of a plant: ὣς ἄρα φωνήσας πόρε φάρμακον ἀργεϊφόντης ἐκ γαίης ἐρύσας, καί μοι φύσιν αὐτοῦ ἔδειξε. (So saying, Argeiphontes [=Hermes] gave me the herb, drawing it from the ground, and showed me its nature.) Odyssey 10.302–03 (ed. A.T. Murray). (The word is dealt with thoroughly in Liddell and Scott’s Greek Lexicon Archived March 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.) For later but still very early Greek uses of the term, see earlier note.

- ^ Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), for example, is translated «Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy», and reflects the then-current use of the words «natural philosophy», akin to «systematic study of nature»

- ^ The etymology of the word «physical» shows its use as a synonym for «natural» in about the mid-15th century: Harper, Douglas. «physical». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- ^

«World Climates». Blue Planet Biomes. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2006. - ^ «Calculations favor reducing atmosphere for early Earth». Science Daily. September 11, 2005. Archived from the original on August 30, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ «Past Climate Change». U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Hugh Anderson; Bernard Walter (March 28, 1997). «History of Climate Change». NASA. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Weart, Spencer (June 2006). «The Discovery of Global Warming». American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (1991). The Age of the Earth. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1569-0.

- ^

Morbidelli, A.; et al. (2000). «Source Regions and Time Scales for the Delivery of Water to Earth». Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 35 (6): 1309–20. Bibcode:2000M&PS…35.1309M. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2000.tb01518.x. - ^

«Earth’s Oldest Mineral Grains Suggest an Early Start for Life». NASA Astrobiology Institute. December 24, 2001. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved May 24, 2006. - ^ a b Margulis, Lynn; Dorian Sagan (1995). What is Life?. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81326-4.

- ^ Murphy, J.B.; R.D. Nance (2004). «How do supercontinents assemble?». American Scientist. 92 (4): 324. doi:10.1511/2004.4.324. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ Kirschvink, J.L. (1992). «Late Proterozoic Low-Latitude Global Glaciation: The Snowball Earth» (PDF). In J.W. Schopf; C. Klein (eds.). The Proterozoic Biosphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-521-36615-1.

- ^ Raup, David M.; J. John Sepkoski Jr. (March 1982). «Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record». Science. 215 (4539): 1501–03. Bibcode:1982Sci…215.1501R. doi:10.1126/science.215.4539.1501. PMID 17788674. S2CID 43002817.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Dorian Sagan (1995). What is Life?. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-684-81326-4.

- ^ Diamond J; Ashmole, N. P.; Purves, P. E. (1989). «The present, past and future of human-caused extinctions». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 325 (1228): 469–76, discussion 476–77. Bibcode:1989RSPTB.325..469D. doi:10.1098/rstb.1989.0100. PMID 2574887.

- ^ Novacek M; Cleland E (2001). «The current biodiversity extinction event: scenarios for mitigation and recovery». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (10): 5466–70. Bibcode:2001PNAS…98.5466N. doi:10.1073/pnas.091093698. PMC 33235. PMID 11344295.

- ^ Wick, Lucia; Möhl, Adrian (2006). «The mid-Holocene extinction of silver fir (Abies alba) in the Southern Alps: a consequence of forest fires? Palaeobotanical records and forest simulations» (PDF). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 15 (4): 435–44. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0051-0. S2CID 52953180. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ The Holocene Extinction Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Mass Extinctions Of The Phanerozoic Menu Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Patterns of Extinction Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Park.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2016.

- ^ Miller; Spoolman, Scott (September 28, 2007). Environmental Science: Problems, Connections and Solutions. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-38337-6.

- ^ Stern, Harvey; Davidson, Noel (May 25, 2015). «Trends in the skill of weather prediction at lead times of 1–14 days». Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 141 (692): 2726–36. Bibcode:2015QJRMS.141.2726S. doi:10.1002/qj.2559. S2CID 119942734.

- ^ «Tropical Ocean Warming Drives Recent Northern Hemisphere Climate Change». Science Daily. April 6, 2001. Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- ^ «Water for Life». Un.org. March 22, 2005. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ «World». CIA – World Fact Book. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Water Vapor in the Climate System, Special Report, American Geophysical Union, December 1995.

- ^ Vital Water. UNEP.

- ^ «Ocean Archived January 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine». The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2002. New York: Columbia University Press

- ^ «Distribution of land and water on the planet Archived May 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine». UN Atlas of the Oceans Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spilhaus, Athelstan F (1942). «Maps of the whole world ocean». Geographical Review. 32 (3): 431–35. doi:10.2307/210385. JSTOR 210385.

- ^

Britannica Online. «Lake (physical feature)». Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.[a Lake is] any relatively large body of slowly moving or standing water that occupies an inland basin of appreciable size. Definitions that precisely distinguish lakes, ponds, swamps, and even rivers and other bodies of nonoceanic water are not well established. It may be said, however, that rivers and streams are relatively fast moving; marshes and swamps contain relatively large quantities of grasses, trees, or shrubs; and ponds are relatively small in comparison to lakes. Geologically defined, lakes are temporary bodies of water.

- ^ «Lake Definition». Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ River {definition} Archived February 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine from Merriam-Webster. Accessed February 2010.

- ^ USGS – U.S. Geological Survey – FAQs Archived July 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, No. 17 What is the difference between mountain, hill, and peak; lake and pond; or river and creek?

- ^ Adams, C.E. (1994). «The fish community of Loch Lomond, Scotland: its history and rapidly changing status». Hydrobiologia. 290 (1–3): 91–102. doi:10.1007/BF00008956. S2CID 6894397. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Introduction to the Ecosystem Concept». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd Edition). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Odum, EP (1971) Fundamentals of ecology, 3rd edition, Saunders New York

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Organization of Life». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd edition). Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Khan, Firdos Alam (2011). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-2009-4.

- ^ Bailey, Robert G. (April 2004). «Identifying Ecoregion Boundaries» (PDF). Environmental Management. 34 (Supplement 1): S14–26. doi:10.1007/s00267-003-0163-6. PMID 15883869. S2CID 31998098. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2009.

- ^ Botkin, Daniel B. (2000) No Man’s Garden, Island Press, pp. 155–57, ISBN 1-55963-465-0.

- ^ «Definition of Life». California Academy of Sciences. 2006. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ The figure «about one-half of one percent» takes into account the following (See, e.g., Leckie, Stephen (1999). «How Meat-centred Eating Patterns Affect Food Security and the Environment». For hunger-proof cities: sustainable urban food systems. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. ISBN 978-0-88936-882-8. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010., which takes global average weight as 60 kg.), the total human biomass is the average weight multiplied by the current human population of approximately 6.5 billion (see, e.g., «World Population Information». U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 28, 2006.[permanent dead link]): Assuming 60–70 kg to be the average human mass (approximately 130–150 lb on the average), an approximation of total global human mass of between 390 billion (390×109) and 455 billion kg (between 845 billion and 975 billion lb, or about 423 million–488 million short tons). The total biomass of all kinds on earth is estimated to be in excess of 6.8 x 1013 kg (75 billion short tons). By these calculations, the portion of total biomass accounted for by humans would be very roughly 0.6%.

- ^ Sengbusch, Peter V. «The Flow of Energy in Ecosystems – Productivity, Food Chain, and Trophic Level». Botany online. University of Hamburg Department of Biology. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Biosphere: Species Diversity and Biodiversity». Fundamentals of Physical Geography (2nd Edition). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ «How Many Species are There?». Extinction Web Page Class Notes. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ «Animal.» World Book Encyclopedia. 16 vols. Chicago: World Book, 2003. This source gives an estimate of from 2 to 50 million.

- ^ «Just How Many Species Are There, Anyway?». Science Daily. May 2003. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ Withers, Mark A.; et al. (1998). «Changing Patterns in the Number of Species in North American Floras». Land Use History of North America. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006. Website based on the contents of the book: Sisk, T.D., ed. (1998). Perspectives on the land use history of North America: a context for understanding our changing environment (Revised September 1999 ed.). U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division. USGS/BRD/BSR-1998-0003.

- ^ «Tropical Scientists Find Fewer Species Than Expected». Science Daily. April 2002. Archived from the original on August 30, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ Bunker, Daniel E.; et al. (November 2005). «Species Loss and Aboveground Carbon Storage in a Tropical Forest». Science. 310 (5750): 1029–31. Bibcode:2005Sci…310.1029B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.7559. doi:10.1126/science.1117682. PMID 16239439. S2CID 42696030.

- ^ Wilcox, Bruce A. (2006). «Amphibian Decline: More Support for Biocomplexity as a Research Paradigm». EcoHealth. 3 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1007/s10393-005-0013-5. S2CID 23011961.

- ^ Clarke, Robin; Robert Lamb; Dilys Roe Ward, eds. (2002). «Decline and loss of species». Global environment outlook 3: past, present and future perspectives. London; Sterling, VA: Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP. ISBN 978-92-807-2087-7.

- ^ «Why the Amazon Rainforest is So Rich in Species: News». Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. December 5, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ «Why The Amazon Rainforest Is So Rich in Species». Sciencedaily.com. December 5, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (2007). «Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils». Precambrian Research. 158 (3–4): 141–155. Bibcode:2007PreR..158..141S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009.

- ^ Schopf, JW (2006). «Fossil evidence of Archaean life». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 361 (1470): 869–85. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. PMC 1578735. PMID 16754604.

- ^ Raven, Peter Hamilton; Johnson, George Brooks (2002). Biology. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Line, M. (January 1, 2002). «The enigma of the origin of life and its timing». Microbiology. 148 (Pt 1): 21–27. doi:10.1099/00221287-148-1-21. PMID 11782495.

- ^ «Photosynthesis more ancient than thought, and most living things could do it». Phys.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Berkner, L. V.; L. C. Marshall (May 1965). «On the Origin and Rise of Oxygen Concentration in the Earth’s Atmosphere». Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 22 (3): 225–61. Bibcode:1965JAtS…22..225B. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1965)022<0225:OTOARO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Schopf J (1994). «Disparate rates, differing fates: tempo and mode of evolution changed from the Precambrian to the Phanerozoic». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91 (15): 6735–42. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.6735S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6735. PMC 44277. PMID 8041691.

- ^ Szewzyk U; Szewzyk R; Stenström T (1994). «Thermophilic, anaerobic bacteria isolated from a deep borehole in granite in Sweden». Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91 (5): 1810–13. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.1810S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1810. PMC 43253. PMID 11607462.

- ^ Wolska K (2003). «Horizontal DNA transfer between bacteria in the environment». Acta Microbiol Pol. 52 (3): 233–43. PMID 14743976.

- ^ Horneck G (1981). «Survival of microorganisms in space: a review». Adv Space Res. 1 (14): 39–48. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(81)90241-6. PMID 11541716.

- ^ «flora». Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on April 30, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ «Glossary». Status and Trends of the Nation’s Biological Resources. Reston, VA: Department of the Interior, Geological Survey. 1998. SuDocs No. I 19.202:ST 1/V.1-2. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007.

- ^ Elhacham, Emily; Ben-Uri, Liad; et al. (2020). «Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass». Nature. 588 (7838): 442–444. Bibcode:2020Natur.588..442E. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5. PMID 33299177. S2CID 228077506.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (April 15, 2021). «Just 3% of world’s ecosystems remain intact, study suggests». The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Plumptre, Andrew J.; Baisero, Daniele; et al. (2021). «Where Might We Find Ecologically Intact Communities?». Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 4. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2021.626635.

- ^ «Feedback Loops in Global Climate Change Point to a Very Hot 21st Century». Science Daily. May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805092998.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik (May 5, 2019). «Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature». Science. doi:10.1126/science.aax9287. S2CID 166478506.