- Home

- Types of Verbs

- Multi-word Verbs

Multi-word verbs are verbs that consist of more than one word. They fall into three types:

- prepositional verbs

- phrasal verbs

- phrasal-prepositional verbs

Before we look at each one, we’ll examine more generally what multi-word verbs are.

What are Multi-word Verbs?

Multi-word verbs are made up of a verb and a particle. Particles are words that we use as prepositions and / or adverbs in other contexts. Here are examples of some of these words:

Verbs

- give

- come

- look

- take

- bring

- put

- made

Particles (Prepositions and Adverbs)

- into

- on

- away

- over

- to

- up

- out

When we combine a verb with a particle to make a multi-word verb, it has a different meaning to the meaning of those words when used on their own.

For instance, here are two common meanings of one word taken from each list:

- give = transfer the possession of something to someone else e.g. I gave him my passport.

- up = towards a higher place or position e.g. he went up the stairs

However, we can put these two words together to make a multi-verb word, creating a completely different meaning:

- He wants to give up smoking = stop

So give up is a multi-verb word we have created by placing together a verb and a particle. Neither give nor up have the same meaning as when they are used on their own.

Where do they come in sentences?

Multi-word verbs are no different to other verbs in that they can be used as a main verb (i.e. after a subject and taking a tense) or in other positions, such as acting as an infinitive:

- Main Verb: He gave up smoking last week (used after a subject and in the past tense)

- Infinitive: It is important to give up smoking (base form of the verb used after an adjective)

Some multi-word verbs can be split up, while others cannot:

- Cannot be separated: She looks after the children on Saturdays

- Can be separated: He looked up the word in the dictionary / He looked the word up in the dictionary

Multi-verb words as idiomatic expressions

Given that multi-word verbs have different meanings to the individual words, they tend to be idiomatic expressions.

Some will make sense as you see them but others may look confusing if you are not already aware of what they mean.

For example, in the first two, we can probably guess the meaning, but the others are more difficult:

- The plane took off at 5pm (= became airborne)

- He got up early this morning (= rise to a standing position)

- She put him up for the week (= provided temporary accommodation)

- She let him off (=forgave)

So with these types of verbs you often have to learn them and their meanings as it can be difficult to guess the meanings from context.

Types of Multi-word Verbs

There are three types of multi-word verbs:

- prepositional verbs

- phrasal verbs

- phrasal-prepositional verbs

1. Prepositional Verbs

A prepositional verb is a multi-word verb made up of a verb plus a preposition. These are the key factors which make these multi-word verb prepositional verbs:

- They must have a direct object

- They are transitive (because they have a direct object)

- The main verb and preposition are inseparable (i.e. the object must go after the preposition)

Structure of Prepositional Verbs

Main Verb + Preposition + Direct Object

Here are some examples of prepositional verbs:

Prepositional Verb Examples

- I sailed through my speaking test

- Their house was broken into

- He can’t do without his car

- She really gets into her music

- I will deal with the problems

- I looked after her cat

In none of these cases can we move the direct object to between the verb and particle, or in other words separate them. For instance we can’t say I sailed my speaking test through or He can’t do his car without.

You may have thought that Their house was broken into does not fit because there appears to be no direct object after ‘into’.

But remember that as prepositional verbs are transitive, they can usually be turned into the passive voice. This example has been turned from active to passive:

- The burglars broke into their house (active)

- Their house was broken into (passive)

2. Phrasal Verbs

A phrasal verb is a multi-word verb made up of a verb plus an adverb. There are two types of phrasal verb:

- Type 1: No object (intransitive) i.e. they don’t take an object

- Type 2: Object (transitive) separable i.e. they need an object and this can go between the verb and particle

Structure of Phrasal Verbs

Type 1

Main Verb + Adverb

Type 2

Main Verb + Direct Object + Adverb

or

Main Verb + Adverb + Direct Object

Some of the most common adverb particles used with Phrasal Verbs are: around, at, away, down, in, off, on, out, over, round, up.

Phrasal Verb Examples

Type 1:

- The plane took off late

- She got up before him

- The film came out in 1979

- I can’t make out what she is saying

- The meeting went on for several hours

Type 2:

- I can put up your friend for the weekend

- I can put your friend up for the weekend

- She brought up many issues at the meeting

- She brought many issues up at the meeting

Phrasal Verbs and Pronouns

Something to note with Phrasal Verbs in type 2 constructions is that if the object is a pronoun, then it must go between the verb and adverb particle. It cannot go after it.

So it has to be like this:

- I can put him up for the weekend

- She brought it up at the meeting

2. Phrasal-Prepositional Verbs

The key distinguishing factors of these types of multi-word verbs are:

- They take an object (so are transitive)

- They have two particles

- The particles are inseparable

Structure of Phrasal-Prepositional Verbs

Main Verb + Particle + Particle

Phrasal-Prepositional Verb Examples

- I look up to my uncle

- You must get on with your work

- He couldn’t face up to his problems

- I always look out for her

- Let’s catch up with John next week

- I always look forward to seeing her

It is possible though with certain phrases to put a direct object after the verb. So in this case there will be a direct object and object of the preposition:

Examples with Verb + Object

- She fixed me up with her freind

- I let Jane in on the secret

- He put me up to it

- I put the problem down to them

Some difficulties for learners

Understanding what multi-word verbs mean

Some learners of English find multi-word verbs difficult because they may take the literal meanings of the individual words. For example, with this sentence:

- I was looking forward to seeing her

It actually means to await eagerly, in this case to meet someone at a later date, but taken literally a person could think it means looking in a particular direction, such as looking ahead at someone.

Misunderstanding Multi-word verbs with two meanings

Some verbs can have two meanings, which confuses some people if they only know one. For example:

- I dropped her off at school (= give someone a lift somewhere)

- I dropped off several times during the class (= falling asleep unintentionally)

Only noticing the verb if separated from the particle

If as a learner, you only notice the verb, then this can make you misunderstand the sentence and again take the verb with it’s literal meaning. This can often happen when they are split up with several words between them:

- He put all of the problems that we have been having down to the hot weather

In such a case the phrasal verb may not be recognised.

Understanding the difference between Phrasal Verbs and Prepositional Verbs

This can be unclear; however, it is not really important to know the differences. As long as you understand that multi-word verbs are verbs plus a preposition or adverb (or both) and that they have a differing meaning to the words on their own, that is enough for most purposes.

But the key difference is that an object can go before or after an adverb, but it can only go after a preposition. In other words:

- Prepositional verbs must not be seperated

- Phrasal Verbs can be separated

Of course type 1 Phrasal Verbs would not be separated because they do not have an object at all.

Incorrect Word order

It is often the case that a speaker or writer may get the the word order of the multi-word verb wrong, with the pronoun placed in the wrong place:

- I don’t have the space to put up him (should be put him up)

Differing grammatical explanations

It can sometimes be confusing when you search on ‘multi-word verbs’ or ‘Phrasal Verbs’ as differing sites or books categorise them differently.

For instance, in some cases, all verbs + preposition or / and adverbs are labelled as multi-word verbs, regardless of whether they create a different meaning. For instance:

- He went into the room

- They are waiting for her

- He is suffering from heatstroke

- I agree with you

In these cases, the phrases have their literal meaning and have not been changed. However, these could be seen simply as words that commonly collate together rather than multi-word verbs.

In some cases, all those that have a different meaning are labelled ‘Phrasal Verbs’, with no reference to prepositional verbs.

This should not really concern you though. The main thing to know is the differing structures with regards to whether words can be separated or not and to understand that with multi-word verbs with different meanings (i.e. what some people just call phrasal verbs) you will probably have to gradually learn there differing meanings.

Here you can find a useful phrasal verb list with examples to start leaning some of the words.

Summary

- Multi-word verbs are a verb plus one or two particles

- It is a word combination that changes the meaning from the individual words

- Prepositional verbs must not be seperated

- Phrasal Verbs can be separated

- They are sometimes all simply known as Phrasal Verbs

New! Comments

Any questions or comments about the grammar discussed on this page?

Post your comment here.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Multi-word verbs are verbs that consist of more than one word.[1] This term may cover both periphrasis as in combinations involving modal or semi-modal auxiliaries with an additional verbal or other lexeme, e.g. had better, used to, be going to, ought to, phrasal verbs, as in combinations of verbs and particles,[2] and compound verbs as in light-verb constructions, e.g. take a shower, have a meal.

References[edit]

- ^ «Multi-word verbs». British Council. Archived from the original on 2011-11-30. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ Beate Haba (2011), Between Heads and Phrases: Particles in English Phrasal Verbs, GRIN Verlag, pp. 6–10, ISBN 978-3-640-83275-0

External links[edit]

- Phrasal Verbs and other multi-word verbs

- Multi-word verbs (phrasal verbs)

Multi-word verbs are verbs which consist of a verb and one or two particles or prepositions (e.g. up, over, in, down). There are three types of multi-word verbs: phrasal verbs, prepositional verbs and phrasal-prepositional verbs. Sometimes, the name ‘phrasal verb’ is used to refer to all three types.

Phrasal verbs

Phrasal verbs have two parts: a main verb and an adverb particle.

The most common adverb particles used to form phrasal verbs are around, at, away, down, in, off, on, out, over, round, up:

bring in go around look up put away take off

Meaning

Phrasal verbs often have meanings which we cannot easily guess from their individual parts. (The meanings are in brackets.)

The book first came out in 1997. (was published)

The plane took off an hour late. (flew into the air)

The lecture went on till 6.30. (continued)

It’s difficult to make out what she’s saying. (hear/understand)

For a complete list of the most common phrasal verbs, see the Cambridge International Dictionary of Phrasal Verbs.

Formality

Phrasal verbs are often, but not always, less formal than a single word with the same meaning.

Compare

|

phrasal verb |

more formal single word |

|

|

|

|

Phrasal verbs and objects

Many phrasal verbs take an object. In most cases, the particle may come before or after the object if the object is not a personal pronoun (me, you, him, us, etc.).

Compare

|

(p = particle; o = object [underlined]) |

|

|

particle before the object |

particle after the object |

|

|

|

|

If the object is a personal pronoun (me, you, him, us, etc.), we always put the pronoun before the particle:

I’ve made some copies. Would you like me to hand them out?

Not: Would you like me to hand out them?

Oh, I can’t lift you up any more. You’re too big now!

Not: I can’t lift up you any more.

We usually put longer objects (underlined) after the particle:

Many couples do not want to take on the responsibility of bringing up a large family of three or four children.

We can use some phrasal verbs without an object:

|

break down |

get back |

move in/out |

|

carry on |

go off |

run away |

|

drop off |

hang on |

set off |

|

eat out |

join in |

wake up |

The taxi broke down on the way to the airport and I thought I nearly missed my flight.

We’d better set off before the rush-hour traffic starts.

What time did you wake up this morning?

A good learner’s dictionary will tell you if the phrasal verb needs an object or can be used without one.

Prepositional verbs

Prepositional verbs have two parts: a verb and a preposition which cannot be separated from each other:

|

break into (a house) |

get over (an illness) |

listen to |

|

cope with (a difficult situation) |

get on |

look after (a child) |

|

deal with (a problem) |

get off |

look at |

|

depend on |

go into |

look for |

|

do without |

lead to |

look forward to |

Prepositional verbs and objects

Prepositional verbs always have an object, which comes immediately after the preposition. The object (underlined) can be a noun phrase, a pronoun or the -ing form of a verb:

Somebody broke into his car and stole his radio.

I don’t like this CD. I don’t want to listen to it any more.

Getting to the final depends on winning the semi-final!

Some prepositional verbs take a direct object after the verb followed by the prepositional phrase.

|

associate … with |

remind … of |

|

protect … from |

rob … of |

|

provide … with |

thank … for |

(do = direct object; po = object of preposition [both underlined])

Hannah reminds [DO]me of [PO]a girlfriend of mine.

How can we protect [DO]children from [PO]dangerous material on the Internet?

I’d like to thank [DO]everyone for [PO]their kindness.

Prepositional verbs or phrasal verbs?

Not all phrasal verbs need an object. Prepositional verbs (e.g. listen to, depend on) always have an object after the preposition:

I’ve got a great new CD. Shall we listen to it?

Not: Shall we listen to?

With phrasal verbs the object can come before or after the particle if the object is not a pronoun. With prepositional verbs, the object is always immediately after the preposition.(Objects are underlined.)

Compare

|

Phrasal verb: the object can come before or after the particle up. |

|

Prepositional verb: the object is after the preposition.

|

Phrasal-prepositional verbs

Phrasal-prepositional verbs have three parts: a verb, a particle and a preposition. The particle and the preposition cannot be separated. Many of these verbs are often used in informal contexts, and their meaning is difficult to guess from their individual parts.

Verb + particle + preposition

|

catch up with |

get on with |

look out for |

|

come up against |

listen out for |

look up to |

|

do away with |

look down on |

put up with |

|

face up to |

look forward to |

watch out for |

|

get away with |

look in on |

Ken’s just chatting to a friend. He’ll catch up with us in a minute. (reach, join)

Do you get on with your neighbours? (have a good relationship with)

We look forward to meeting you on the 22nd. (anticipate with pleasure)

Phrasal-prepositional verbs and objects

The object (underlined below) always comes immediately after the preposition, and not in any other position:

She was a wonderful teacher. We all looked up to her. (respected)

Not: We all looked her up to. or We all looked up her to.

Some phrasal-prepositional verbs also take a direct object after the verb as well as an object of the preposition:

|

fix … up with |

put … down to |

put … up to |

|

let … in on |

take … out on |

(do = direct object; po = object of preposition [both underlined])

She fixed [DO]us up with [PO]a violin teacher. We’re really grateful to her. (fixed us up with = arranged for us)

We just put [DO]the accident down to [PO]bad luck; there’s no other reason. (put down to = think the cause or reason is)

Contents

- 1 Advanced Grammar for IELTS: Multi-word verbs – Diagnose Test, Grammar Explanation & Practice Exercises

- 1.1 Diagnostic Test

- 1.1.1 Multi-word Verbs

- 1.2 Grammar Explanation: Multi-word Verbs

- 1.2.1 Form and Use

- 1.2.2 Phrasal Verbs

- 1.2.3 Prepositional Verbs

- 1.2.4 Phrasal-Prepositional Verbs

- 1.2.5 Word List: Common Multi-word Verbs

- 1.3 Practice Exercise

- 1.4 Answer Key for Diagnostic Test

- 1.5 Answer Key for Practice Test

- 1.1 Diagnostic Test

Advanced Grammar for IELTS: Multi-word verbs – Diagnose Test, Grammar Explanation & Practice Exercises

Diagnostic Test

Multi-word Verbs

Rewrite these sentences replacing the underlined words with the words in brackets. Make any necessary changes to word order.

Example:

- She repaid the debt punctually. (on time/paid/back/it)

- ==> __She paid it back on time__

- The whole story was invented by Suzy’s brother. (by/him/made/was/up)

- Maintain the good work. (up/it/keep)

- Make sure you carefully follow the guidelines. (strictly/to/stick)

- This tie doesn’t match that shirt ___(it/with/go)

- We met my wife’s cousin by chance at the museum. (into/him/ran)

- These are the beliefs our movement upholds. (stands/which/for/our movement)

- The company won’t tolerate this kind of behaviour. (with/it/put/up)

- I revealed the secret to Elizabeth. (it/her/in/let/on)

Eight of the following sentences contain grammatical mistakes or an inappropriate verb or multi-word verb. Tick (✓) the correct sentences and correct the others.

Examples:

- They’re a company with which we’ve been dealing for many years. ✓

- Her Majesty turned up at the ceremony in the dazzling Imperial State Coach. ==> arrived

- That division was taken by head office over.

- The very first breakout of the disease was reported in Namibia.

- Steve was left by his ex-girlfriend out from her wedding invitation list.

- It is a condition of receiving this Internet account that you do not give away your confidential PIN number to any third party.

- Could you activate the kettle, darling? I’m dying for a cup of tea.

- He fell down the floor and hurt himself.

- Come on! We’re going to be late!

- The plane took off the ground at incredible speed.

- The government brought recently in some legislation to deal with the problem.

- There are few people for whom he cares so deeply.

- They took Clive up on his invitation.

- We look forward eagerly to your wedding.

Grammar Explanation: Multi-word Verbs

A common feature of English is the combination of verbs with prepositions and/or adverbs to create multi-word verbs, e.g. to put off, to put out, to put up with. These verbs can be difficult for learners because the meanings often cannot be worked out from the individual words, and there are special rules about the position of objects with these verbs. We sometimes refer to all multi-word verbs as ‘phrasal verbs’, although there are several different types.

Form and Use

Overview

Multi-word verbs are formed from a verb, e.g. grow, plus an adverbial particle, e.g. away, back, out, or a prepositional particle, e.g. on, off, up. There are four types of multi-word verb and each type has different rules, for example about the use or position of the object:

| Type 1 | intransitive phrasal verbs

e.g. take off:

|

| Type 2 | transitive phrasal verbs

e.g. put something off :

(The noun object can go before or after the particle.) |

| Type 3 | prepositional verbs

e.g. cope with something :

|

| Type 4 | phrasal-prepositional verbs

e.g. look forward to something :

|

Learner dictionaries indicate which type a verb is by showing a noun object with the verb:

put sb/ sth off phr v [T] to arrange to do something at a later time or date, especially because there is a problem, difficulty etc:

- They’ve put the meeting off till next week.

Multi-word verbs form tenses, and are used in questions and negatives and in the passive voice, in the same way as other verbs:

- Will you be putting the party off? (future continuous question)

- The party has been put off until next month. (present perfect passive)

We never separate the verb and particle in the passive form:

X That story was made by a resentful employee up

✓ That story was made up by a resentful employee.

We can sometimes form nouns from multi-word verbs.

- The car broke down five kilometres from home. (multi-word verb)

- The breakdown happened five kilometres from home. (noun)

In some cases the order of the verb and particle is reversed in the noun derived from them:

- The epidemic first broke out in Namibia. (multi-word verb)

- The first outbreak of the epidemic was in Zaire. (noun)

Formal and Informal Use

Where a multi-word verb has no exact synonym, e.g. grow up, we can use it in formal and informal contexts. However, when there is a single verb with an equivalent meaning, e.g. think about (= consider), the multi-word verb tends to be used in informal contexts while the single verb is more formal. Compare these examples:

- [The bank will think about your application in due course.]

- The bank will consider your application in due course. (formal)

- [Honestly, how can you consider money at a time like this!]

- Honestly, how can you think about money at a time like this! (informal)

Meaning

It is sometimes possible to get an idea of the meaning of a multi-word verb from its particle, because some particles are associated with areas of meaning, for example:

| on – starting/continuing/progressing, e.g. carry on, take on, get on |

| out – thoroughness, e.g. work out, see out, mark out |

| up – completion/finality, e.g. give up, break up, eat up |

Note: However, these areas of meaning can be abstract and may not cover all cases.

Phrasal Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive phrasal verbs (type 1) consist of a verb plus an adverb. Phrasal verbs usually have a meaning which is different from the meaning of the separate parts:

- Getting by on my salary isn’t easy! (= managing)

- Rollerblading never really caught on in England. (= became popular)

As intransitive phrasal verbs have no direct object, they cannot be made passive:

X My car broke down the engine.

✓ My car broke down

Intransitive phrasal verbs are sometimes used in imperatives:

- Watch out. That floor’s not very solid.

- Come on! I can’t wait all day!

Transitive Verbs

Transitive phrasal verbs (type 2) consist of a verb + adverb and have a direct object (either a pronoun or a noun):

- It isn’t true, I made it up. I made up that story.

If the object is a noun, it can either be between the verb and particle, or after the particle:

- I made a story up. I made up a story.

If the object is a pronoun, we put it between the verb and particle, but not after the particle:

X I made up it.

✓ I made it up.

Note: We can’t put an adverb between the verb and particle or between the particle and object:

X I paid early back the loan.

X I paid back early the loan.

✓ I paid the loan back early.

Note: We can’t put a relative pronoun immediately before or after the particle.

X That’s the room which up I did.

X That’s the room up which I did.

✓ That’s the room which I did up.

Some phrasal verbs have a transitive use with one meaning, and an intransitive use with a different meaning. Compare:

- The plane took off on time. (take off, intransitive = become airborne)

- The man took off his coat. (take something off, transitive = remove)

Prepositional Verbs

Form and Use

Prepositional verbs (type 3) consist of a verb, e.g. look, plus a preposition, e.g. into, at. for. The combination of the verb and preposition creates a new meaning which can sometimes, but not always, be worked out from the parts:

- She looked for her missing passport. (= searched, tried to find)

- Would you mind looking into his complaint? (= investigating, researching)

These verbs are transitive. We put the noun or pronoun object after the preposition, and not between the verb and preposition:

X We didn’t fall his story for.

X We didn’t fall it for.

✓ We didn’t fall for it/his story

With prepositional verbs (but not phrasal verbs above) we can put an adverb between the verb and preposition. But we cannot put an adverb between the preposition and object:

X She parted with reluctantly her money.

✓ She parted reluctantly with her money.

Special Uses

In formal English we sometimes prefer to avoid a preposition at the end of a sentence. With prepositional verbs (but not phrasal verbs above) we can put the preposition in front of the relative pronouns whom or which:

- These are the principles (which) our party stands for.

- ==>These are the principles for which our party stands.

- That’s the type of client (whom) I’m dealing with.

- ==> That’s the type of client with whom I’m dealing.

Note: But we cannot put the preposition after whom or which:

X These are the principles which for our party stands.

Some prepositional verbs are mainly used in the passive form , especially in written English:

- The marketing strategy is aimed at a target audience of 18 to 25 year olds.

Phrasal-Prepositional Verbs

Form and Use

These verbs (type 4) are formed by combining a verb with an adverb and Form and preposition. The combination creates a new meaning which cannot usually be use understood from the meanings of the individual parts:

- We look forward to hearing from you. (= anticipate with pleasure)

They are transitive and can be made passive:

- All her employees looked up to her. (active)

- She was looked up to by all her employees. (passive)

We can never use a noun or pronoun object between the particles:

X I can’t put up this treatment/it with any longer.

We cannot usually put a noun or pronoun object immediately after the verb:

X I can’t put this treatment /it up with any longer.

✓ I can’t put up with this treatment/ it any longer.

The exception is when the verb has two objects, e.g. let somebody in on something, take somebody up on something:

- We let James in on the plan.

- We took her up on her offer.

Note: We cannot put an adverb before the first particle or after the final particle, but we can use an adverb between the two particles:

X He stands strongly up for his principles. (verb + adverb + particle)

X He stands up for strongly his principle.(particle + particle + adverb)

✓ He stands up strongly for his principles. (particle + adverb+ particle)

Word List: Common Multi-word Verbs

These tables include all multi-word verbs which occur at least ten times per million words in the Longman Corpus Network. (Below, sb = somebody and sth = something.)

Type 1: Intransitive Phrasal Verbs

break down (= stop working), catch on (= understand/become popular), come back (= return), come in, come on. fall out (= quarrel), fall through, fit in, get by (= manage/cope), get up, go away, go on (= continue), go out, grow up, look out, pass out (= faint), shut up. sit down, stand up, stay on (= remain), take off, turn up (= arrive), wake up, watch out.

Type 2: Transitive Phrasal Verbs

act sth out {= perform/demonstrate), bottle sth up {= not allow a feeling to show), bring sth in (= introduce), bring sb up (= rear), bring sth up (= mention sth/introduce a topic), carry sth out (= perform/undertake). do sth up (= restore/redecorate). fill sth in/out (= complete in writing), find sth out (= discover), fix sth up (= arrange), give sth away (= reveal), give sth up (= stop), hold sth up (= delay), keep sth up (= maintain), leave sth/sb out, let sth out (= release), look sth up. make sth up (= invent), pay sb back, pick sth up (= collect), point sth out (= highlight/explain), pull sth/sb down (= demolish, demote), put sth away, put sth off (= postpone), put sth on, put sb up (= accommodate), run sb down (= criticise), set sth up (= establish/implement/organise), take sth over, take sth up, throw sth away, turn sthlsb down (= refuse), turn sth/sb out.

Type 3: Prepositional Verbs

call for sb, care for sb, come across sth (= encounter), cope with sth, deal with sth (= manage, handle), fall for sth (= be tricked), feel like sth, get at sb/sth, get over sth (= recover from), get through {= finish successfully), go into sth, go with sth (= match), ead to sth, look after sb/sth, look at sth (= observe), look into sth (= investigate), look like sth (= resemble), look round sth (= visit, etc.), part with sth, pay for sth, rely on sth/sb, run into sb (= meet by chance), see to sth (= organise/manage), send for sb, stand for sth (= represent/mean/tolerate), stick to sth (= persevere/follow), take after sb, talk about sth, think about sth (= consider).

The following prepositional verbs are usually used in the passive:

be aimed at (= intended for), be applied to, be considered as, be derived from, be known as, be regarded as, be used as, be used in

Type 4: Phrasal-Prepositional Verbs

back out of sth, break in on sth, catch up on sth/sb, catch up with sb, check up on sth / sb, come across as sth (= appear to be), come down to sth (= be essentially), come up with sth (= invent), cut down on sth (= reduce), do away with sth, drop in on sb, face up to sth (= confront), get away with sth, get back to sth (= return), get down to sth, get on with sth, get out of sth, give in to sth, go out for sth, go up to sb (= approach), keep away from sb/sth (= avoid), keep up with sb. look down on sb, look forward to sth (= anticipate), look out for sblsth, look up to sb (= admire/respect), make away with sth, move on to sth, put up with sth/sb (= tolerate), run away with sb, run off with sth, stand up for sth (= defend), turn away from sth, walk out on sth/sb

The following phrasal-prepositional verbs are usually used in the passive:

be cut off from, be made up of, be set out in

Also check:

- Grammar for IELTS

- IELTS Grammar books

- English Pronunciation in use Intermediate pdf

Practice Exercise

Q 1.

Underline the most suitable verb in bold in each of these sentences.

- Don’t stop now Liz. Continue/ Go on, I’m dying to hear the end of the story!

- In a bid to improve diplomatic relations, the Foreign Office has arranged/fixed up a visit by senior embassy staff.

- The court sentences you to life imprisonment, with the recommendation that you not be released /let out for a minimum period of twenty years.

- Owing to a lack of military support, the United Nations feels unable to maintain /keep up its presence in the war-torn province.

- I don’t think your dad trusts me – he’s always observing / looking at me.

- You’ve got to make an effort, darling. You’ll never lose weight unless you reduce / cut down on the amount of fatty food you eat.

- The government have announced plans to abolish/ do away with the disabled person’s vehicle allowance in the next budget.

- My little brother’s always getting bullied at school. He just won’t confront/ face up to the other kids.

- The presidential party will arrive / turn up at the palace shortly before luncheon.

- My best friend always exaggerates – half the things he says are just invented/ made up!

Q 2.

Rewrite these sentences using an appropriate multi-word verb. You must use a pronoun ( it, him, her, them) to replace the underlined object. In some cases you may have to change the word order. The exercise begins with an example (0).

- (0) They’ve postponed the housewarming party until Friday.

- ==> They’ve put it off until Friday

- Would you mind organising the removal yourself?

- I met Steve and Terri quite by chance at the supermarket this morning.

- I’ve arranged the meeting for ten o’clock tomorrow.

- You’re always criticising your colleagues.

- I’m sure the police will investigate the burglary.

- The builders undertook the job very professionally.

- Could you collect the children from school tonight?

- Has Perry recovered from the flu yet?

- She really resembles her parents, doesn’t she?

- Would you highlight the advantages for me?

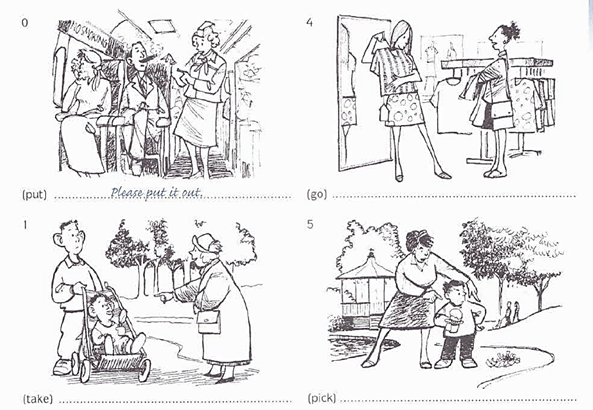

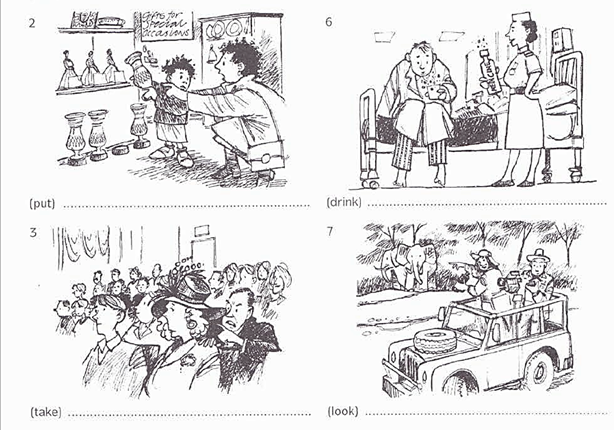

Q 3.

What are the people saying in the pictures on the next page? Write a short sentence for each situation using multi-word verbs and a suitable pronoun (it, them, you, etc.). All the multi-word verbs you need can be formed from the verbs in brackets and the particles in the box. The first one has been done as an example (0).

| with | after | at | down | off | out | up (x2) |

Q 4.

Rewrite the parts of the sentences in brackets with the words in the correct order.

- (0) Don’t (tomorrow/put/until/off/it); do it now.

- ==> Don’t put it off until tomorrow

1. Thanks for the invitation; (looking/to/I’m/it/forward).

2. The evil witch (frog/prince/the/into/turned/handsome/a).

3. I won’t have any sugar thank you; (it/I’ve/up/given).

4.There isn’t a death penalty any longer; (away/they’ve/it/done/with).

5. He’s the footballer (million/a/team/manager/for/the/paid/whom/dollars).

6. I have a small trust fund; (by/it/my/was/set/grandfather/up).

Q 5.

Read the magazine article below. Then use the information in the text to complete the informal summary on the next page. Use no more than three words for each gap (1-18), including the word in brackets. The words you need are all multi-word verbs and do not occur in the newspaper article. The exercise begins with an example (0).

When Anger is Healthy

Everyone knows that not allowing oneself to show feelings of anger and resentment can be very unhealthy, leading to stress and long-term feelings of inadequacy and powerlessness. But how do we release our anger without looking foolish or petulant?

The first thing to learn is that expressing your anger and losing your temper arc not the same thing at all. One is natural and healthy, the other is destructive and dangerous. We usually admire those who can express their anger calmly, and see them as ‘firm but fair’ or mature and self-confident. While those who lose their temper appear to be immature, childish, selfish and aggressive.

Mandy Dickson is a psychologist who has established a successful one-day anger workshop that helps ordinary people to learn about and manage their anger. The seminar is not intended for criminals or the mentally ill, but for those ordinary people who feel powerless to control their own tempers.

The first thing Mandy explains is that anger is a natural and normal feeling, and that feeling angry about something is nothing to be ashamed of. But we need to recognise anger when we feel it, and to investigate its true causes. Once we know the real cause of anger we can confront it and begin to do something positive about it. Mandy asks participants to complete a questionnaire about things that make them angry. By comparing these ‘triggers’ people often discover that the true causes of anger are other feelings, especially fear, disappointment and grief. But because it is not socially acceptable in our culture to openly demonstrate these feelings, we express them as anger. This is particularly true for men who, even in these enlightened times, are expected to hide any feelings of inadequacy or fear and be strong and stoical in all situations.

Having recognised the causes of anger, the first step is to learn how to avoid anger-inducing situations. The next step is to learn how to express one’s feelings calmly and firmly. Mandy believes that when we are angry we want other people to understand our anger and sympathise with it. But we often fall into the trap of expressing anger by criticising those around us, when what we really want is their support and empathy. One of the most common causes of anger is when other people fail to behave in a way you expect them to. But as Mandy explains, human beings are not telepathic, they cannot be expected to automatically anticipate other people’s desires and wishes. So an essential tool in reducing the occurrence of anger-inducing situations is to always explain exactly what you want and expect from those around you. It is all essentially a question of communication.

We know (0)_bottling up_(bottle) anger can be unhealthy. But how do we (1)__(let) our anger without seeming foolish? Expressing anger and losing your temper are different things. One is healthy, the other dangerous. We (2)___(look) people who express anger calmly, but those who lose their temper (3)__(come) immature and aggressive. Mandy Dickson has (4)___(set) a one-day anger workshop which helps people learn about and (5)___(deal) their anger. It is (6)__(aim) ordinary people who don’t feel able to control their tempers. She (7)___(point) that anger is natural and nothing to be ashamed of, but we should recognise it and (8)___(look) its true causes. Then we can (9)___(face) it, and begin to do something positive. Participants (10)___(fill) a questionnaire about things that make them angry. They compare their responses and often (11)____(find) that the causes are other feelings such as fear or grief. But in our culture it isn’t acceptable to (12)___(act) these feelings in public. Men, in particular, are supposed to (13)____(cover) these feelings.

Once we know the causes of anger, we must learn how to (14)___(keep) situations which will induce them. When we are angry we want other people to understand us, but we often make the mistake of (15) ___(run) those around us. Anger is often caused by the feeling that you have been (16)___(let) by other people. But we can’t always expect other people to know our feelings. So the most important way to (17) ____(cut) the number of anger-producing situations is to tell people exactly how we feel. It really all (18)____(come) communication.

Q 6.

Rewrite John’s half of this unnatural telephone conversation in a more natural, informal style. Use the multi-word verbs in the box to replace the underlined verbs and phrases. Replace nouns with pronouns where possible and make any other necessary changes, as in this example:

JOHN: (0) I’ve just demolished the conservatory. ==> …. I’ve just pulled it down…..

| do sth up | take sth off |

| put up with sb | look forward to sth |

| stay up | sit down |

| get on with sb | take sth up |

| put sb up | finish sth off |

| turn sth into sth | sort sth out |

| look down on sb | turn sth down |

| put sth up | pull sth down |

DAVE: John, it’s Dave. How are things?

JOHN: Sorry, I can’t hear you. (1) I’ll just reduce the volume on the radio. That’s better.

DAVE: How are things? Still working on the house?

JOHN: Yes. (2) We’ve completed the work on the kitchen and (3) we’re renovating the dining room. (4) We’re transforming the room into a second bedroom. (5) I’ve just mounted the wallpaper but I’ve been having trouble getting it (6) to remain vertically attached.

DAVE: I know what you mean. I hate wallpapering.

JOHN: (7) And it’s all got to be organised and ready by Saturday. Jane’s mother is coming and we’re (8) providing accommodation for her for a few days.

DAVE: I thought you didn’t like her.

JOHN: (9) We don’t interact in a friendly way with each other but (10) I can tolerate her for a few days.

DAVE: Why do you dislike her so much?

JOHN: (11) I’m sure she regards me as inferior to her. And she’s so lazy, I mean she comes in, (12) removes her coat, (13) assumes a seated position and expects us to wait on her hand and foot!

DAVE: I see what you mean. Sounds like a nightmare.

JOHN: (14) Mm. I think I might commence gardening as a hobby – just to get me out of the house!

DAVE: Good idea. Well, I’d better let you get on. And don’t forget about our party on Friday.

JOHN: (15) Of course not. I’m anticipating the party with pleasure.

Answer Key for Diagnostic Test

- was made up by him.

- Keep it up.

- stick strictly to

- go with it.

- ran into him

- which our movement stands for./ for which our movement stands.

- put up with it.

- let her in on it.

- by head office over ==> over by head office

- breakout ==> outbreak

- left by his ex- girlfriend out ==> left out by his ex-girlfriend

- not give away ==> not reveal (give away is an inappropriate verb in a formal context)

- activate ==> turn on/switch on (activate is an inappropriate verb in an informal context)

- down the floor and ==> down (on the floor) and

- ✓

- took off the ground at incredible speed ==> took off (from the ground) at incredible speed.

- brought recently in ==> recently brought in

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

Answer Key for Practice Test

Q 1.

- Go on

- arranged

- released

- maintain

- looking at

- cut down on

- abolish

- face up to

- arrive

- made up

Q 2.

- Would you mind seeing to it/sorting it out yourself?

- I ran into them at the supermarket this morning.

- I’ve fixed it up for ten o’clock tomorrow.

- You’re always running them down.

- I’m sure the police will look into it.

- The builders carried it out very professionally.

- Could you pick them up from school tonight?

- Has Perry got over it yet?

- She really looks like them/takes after them, doesn’t she?

- Would you point them out for me?

Q 3. (Suggested Answers)

- He takes after you.

- Put it down!

- Please take it off.

- It doesn’t go with it.

- Pick it up!

- Drink it up.

- Look at them!

Q 4.

- I’m looking forward to it

- turned the handsome prince into a frog/turned the frog into a handsome prince

- I’ve given it up

- they’ve done away with it

- for whom the team manager paid a million dollars

- it was set up by my grandfather

Q 5.

- let out

- look up to

- come across as

- set up

- deal with

- aimed at

- points out

- look into

- face up to

- fill in/fill out

- find out

- act out

- cover up

- keep away from

- running down

- let down

- cut down

- comes down to

Q 6.

- I’ll just turn the radio down

- We’ve finished off the kitchen

- We’re doing up the dining room

- We’re turning it into a second bedroom

- I’ve just put the wallpaper up

- stay up

- sorted out

- putting her up

- get on with each other

- put up with her

- looks down on me

- takes her coat off

- sits down

- I think I might take up gardening

- looking forward to it

UNIT 22

MULTI–WORD VERBS

OUTLINE

1. INTRODUCTION.

1.1. Aims of the unit.

1.2. Notes on bibliography.

2. A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR MULTI-WORD VERBS.

2.1. Linguistic levels involved in the notion of time reference.

2.2. On defining time reference: what and how.

2.3. Grammar categories involved: open vs. closed classes.

3. A GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO MULTI-WORD VERBS.

3.1.On defining the term ‘multi- word verbs’.

3.2.A classification of multi- word verbs.

4. PHRASAL VERBS.

5. PREPOSITIONAL VERBS.

6. PHRASAL-PREPOSITIONAL VERBS.

7. SPECIFIC IDIOMATIC CONSTRUCTIONS.

8. EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS.

9. CONCLUSION.

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY.

1. INTRODUCTION.

1.1. Aims of the unit.

Unit 22 is primarily aimed to examine in English the notion of multi-word verbs . However, we shall also include in the study of these forms an analysis of their main structural features in terms of form and function in order to provide a relevant and detailed account of this issue despite the fact it is not stated in the original title.

Then, the study will be divided into eight chapters. Thus, Chapter 2 provides a theoretical framework for multi- word verb, first, by answering questions such as, first, which linguistic levels are involved in the notion of time reference; second, what it describes and how; and third, which grammar categories are involved in its description at a functional level.

Once we have set up the linguistic framework, we shall offer a general introduction to multi-word verb in Chapter 3 which shall include (1) a definition of multi-word verbs and (2) a classification of multi-word verbs, to be fully described in the subsequent chapters. Therefore, Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 will offer a descriptive account of the main structural features of multi-word verbs in terms of form and function at the level of everyday use regarding colloquial and formal speech and idiomatic expressions. Therefore, we shall namely follow morphological, phonological, syntactic and semantic guidelines.

Chapter 8 provides an educational framework for the structural features of multi-word verbs within our current school curriculum; Chapter 9 draws on a summary of all the points involved in this study; and finally, bibliography will be listed in alphabetical order.

1.2. Notes on bibliography.

In order to offer an insightful analysis and survey on multi- word verbs in English, we shall deal with the most relevant works in the field, both old and current, and in particular, influential grammar books which have assisted for years students of English as a foreign language in their study of grammar. For instance, a theoretical framework for this type of verbs is namely drawn from the field of sentence structures, that is, from the work of Flor Aarts and Jan Aarts (University of Nijmegen, Holland) in English Syntactic Structures (1988), whose material has been tested in the classroom and developed over a number of years; and that of Thomson & Martinet, A Practical English Grammar (1986).

Other classic references which offer an account of the most important and central grammatical constructions and categories in English regarding multi-word verbs, are Quirk & Greenbaum, A University Grammar of English (1973); Sánchez Benedito, Gramática

Inglesa (1975); and Quirk et al., A comprehensive grammar of the English language (1985). More current approaches to notional grammar on multi-word verbs are Sidney Greenbaum, The Oxford Reference Grammar (2000); Angela Downing and Philip Locke, A University Course in English Grammar (2002).

2. A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR MULTI-WORD VERBS.

Before describing in detail the notion of multi- word verbs in English, it is relevant to establish first a theoretical framework for this type of verbs, since they must be described in grammatical terms. In fact, this introductory chapter aims at answering questions such as, first, which linguistic levels are involved in the notion of multi-word verbs; second, what it describes and how ; and third, which grammar categories are involved in its description at a functional level.

2.1. Linguistic levels involved in the notion of multi-word verbs.

In order to offer a linguistic description of the notion of multi-word verbs, we must confine it to particular levels of analysis so as to focus our attention on this particular aspect of language. Yet, although there is no consensus of opinion on the number of levels to be distinguished, the usual description of a language comprises four major components: phonology, grammar, lexicon, and semantics, out of which we get five major levels: phonological, morphological and syntactic, lexical, and semantic (Huddleston, 1988).

First, the phonology describes the sound level, that is, consonants, vowels, stress, intonation, and so on. Secondly, since the two most basic units of grammar are the word and the sentence, the component of grammar involves the morphological level (i.e. one- word vs. multi-word verbs) and the syntactic level (i.e. word order in the sentence). Third, the lexicon, or lexical level, lists vocabulary items, specifying how they are pronounced, how they behave grammatically, and what they mean.

Finally, another dimens ion between the study of linguistic form and the study of meaning is semantics, or the semantic level, to which all four of the major components are related. We must not forget that a linguistic description which ignores meaning is obviously incomplete, and in particular, when dealing with the notions of multi- word verbs or more commonly known as phrasal verbs where semantics plays a very important role at the time of distinguish them.

Therefore, we must point out that each of the linguistic levels discussed above has a corresponding component when analysing the notion under study. Thus, phonology deals with the accent, rhythm and intonation on verbs, prepositions and adverbs (i.e. I’m looking for a T-shirt); morphology deals with the verb structure (i.e. one-word vs. multi-word verbs); and syntax deals with which combinations of words constitute grammatical strings and which do not (i.e. NOT: Can I try on it? BUT Can I try it on?).

On the other hand, lexis deals with the expression of time reference regarding the choice between different types of prepositions (i.e. look at/after/into/like/for ) or adverbs (i.e. look forward to) and the use of specific prepositions with certain structures (i.e. get on with somebody/run out of petrol); and finally, semantics deals with meaning where syntactic and morphological levels do not tell the difference (i.e. I can’t put up with racism = I can’t tolerate racism).

2.2. On defining multi- word verbs: what and how.

On defining multi-word verbs, we must link this notion (what it is) to the grammar categories which express it (how it is showed). Actually, on answering What is it?, the term

‘multi-word verb’ is defined in opposition to the term ‘one-word verb’. In fact, both terms are drawn from the classification of lexical verbs into two types, where ‘one-word verbs’ consist of one single lexical item and multi-word verbs of at least two. It is from the latter that we get the notions that constitute the core of our study: phrasal verbs, prepositional verbs, phrasal-preposit ional verbs and verb +noun+preposition/verb + adjective idioms. Regarding how multi- word verbs are realized, we must examine the grammar categories related to them, that is, open vs. closed classes which are fully examined in next section.

2.3. Grammar c ategories involved: open vs. closed classes.

So far, in order to confine the notion of multi- word verbs to particular grammatical categories, we must review first the difference between open and closed classes since multi- word verbs involve both. Yet, grammar categories in English can be divided into two major sets called open and closed classes. The open classes are verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs, and are said to be unrestricted since they allow the addition of new members to their membership, whereas the closed classes are the rest: prepositions, conjunctions, articles (definite and indefinite), numerals, pronouns, quantifiers and interjections, which belong to a restricted class since they do not allow the creation of new members.

Then, as we can see, when taking multi-word verbs to phrase and sentence level, we are dealing with both classes, for instance, open word classes, which mainly involve lexical verbs, along with open-class nouns, adjectives, and adverbs; and also with the category of closed classes, such as prepositions. Finally, it is worth noting that apart from grammatical categories, we may find other specific phrase structures, such as idiomatic expressions which are part of everyday speech (i.e. They turned up an hour later =arrived/S he made the story up=invented)

3. A GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO MULTI-WORD VERBS.

Therefore, we shall define multi-word verbs and then we shall establish a classification of multi- word verbs taking into account the internal and external features which shape them. For instance, the notions of transitivity vs. intransitivity, the possibility of pronoun/noun insertion, passivity, pronominal questions and adverbial questions. On defining the term‘multi-word verbs’.

3.1. On defining multi- word verbs.

Multi-word verbs are defined as a large group of verbs which consist of a basic verb + one or more particles, which can be prepositions (i.e. look after) or adverbs (i.e. look up). Other possible combinations are verb + adverb + preposition (i.e. look forward to) and a combination with nouns (i.e. take care of) and adjectives (i.e. set free). It is important to bear in mind that a multi-word verb (also called two-word verb or compound verb) is still a verb (i.e. get vs. get up), whose meaning may have little or no connection with the individual units that make it possible.

The possible combinations may have literal meaning, that is, can be predicted on the meaning of each element (i.e. apply for, break off, consent to, fill out, find out, live on, refer to) even if we do not take into account the preposition after it, whereas other combinations cannot be predicted because of each element (i.e. come down with, face up to, keep up with, look forward to, put up with, run away with) . On the contrary, they have fixed comb inations and have to be learnt as individual vocabulary items.

It is also important to distinguish whether a multi- word verb is transitive or intransitive, and this is achieved by means of the choice between adverb and preposition. For instance, ‘look at’ is transitive since an object is required after it (i.e. He was looking at his wife) whereas ‘look out’ is intransitive since it cannot have an object after it (i.e. Look out! A cat is crossing the road!). Hence, the preposition is followed by an object whereas the adverb is not. However, we may find some instances where the same multi- word verb may function as transitive and intransitive at the same time (i.e. take off: ‘Take off your shoes vs. The helicopter took off at midnight’).

3.2. A classification of multi-word verbs.

Following Quirk et al. (1985), multi-word verb combinations are realized by four main combination types: first, phrasal verbs (verb + adverb); second, prepositional verbs (verb + preposition); third, phrasal prepositional verbs (verb + adverb + preposition); and fourth, verb + noun + preposition or verb + adjective (+preposition). Each type will be fully described in next chapters individually, from the linguistic paradigms of form and function, that is, regarding morphological and phonological features (form) and syntactic and semantic features (function).

4. PHRASAL VERBS.

Phrasal verbs are formed by the structure ‘verb + adverb’, that is, combinations of a verb and a member of a closed set of adverbs, such as about, across, along, around, aside, away, back, by, down, forht, in, off, on, out, over and up, where the word stress is placed on the adverb and not on the verb (i.e. Chris called ‘up the seller” (phrasal verb) vs. “Chris ‘called on the seller” (prepositional verb), even if it is in final position (i.e. He call him ‘up).

With respect to this last example, we must address the syntactic function of multi-word verbs, whereby we must take into account the question of pronoun/noun insertion within the concepts of ‘transitivity’ and ‘intransitivity’ since phrasal verbs can be both. First of all, we shall point out that intransitive phrasal verbs do not take a direct object after them and, therefore, do not allow other elements in between (i.e. break down, come in/out/up/down/back, get up).

On the other hand, transitive phrasal verbs take a direct object after the particle and, therefore, they have the possibility of inserting nouns in between the verb and the particle, that is, pronouns to substitute nouns in object function (i.e. bring up, fill in/out, find out, put off, put on, ring up, among others). Following Quirk & Greenbaum (1973), “with most transitive phrasal verbs, the particle can either precede or follow the direct object (i.e. They turned on the light vs. They turned the light on) although it cannot precede personal pronouns (i.e. They turned it on but NOT: They turned on it). As we can see, the particle tends to precede the object if the object is long or if the intention is that the object should receive end – focus.

Phrasal verbs are generally defined as ‘non- literal’ since their meaning cannot be deduced by defining its individual parts (i.e. The enemy gave up/She took in her parents/They called off the meeting). However, some phrasal verbs have literal meaning and can be easily deduced from the sum of its individual parts (i.e. The guests came in/She went out/They found out the truth).

5. PREPOSITIONAL VERBS.

Prepositional verbs are formed by the structure ‘verb + preposition’ and are combinations of a verb + prepositions such as ‘at, in, on, for, about, etc’ (i.e. ask for, believe in, care for, deal with, live on, long for, object to, part with, refer to, write about among others). They are usually monotransitive and can take direct objects (i.e. He did not enlarge on this subject/Aren’t you listening to my advice?). As a rule the stress falls on the verb and the preposition is unstressed (i.e. “Why are you looking ‘up that word in the dictionary” (phrasal verb) vs. “Don’t ‘look at me!” (prepositional verb).

Regarding their syntactic function, it is again necessary to remember that they can be transitive or intransitive verbs and therefore, they allow other elements in between (i.e. take after, look like, go up, go down, get over). For instance, “the preposition in a prepositional verb must precede its complement. Hence, we can contrast the prepositional verb ‘call on’ (visit) with the phrasal verb ‘call up’ (summon). On the other hand, the prepositional verb allows an inserted adverb after the verb and a relative pronoun after the preposition (i.e. They called early on the man BUT NOT: They called early up the man/ The man on whom they called BUT NOT: The man up whom they called)” (Quirk & Greenbaum, 1973:349).

“In general, prepositional verbs, such as ‘call on’ or ‘look at’ + their prepositional complements differ from single-word verbs + prepositional phrases, as in ‘They called at the hotel’ and ‘They called after lunch’, in that they allow pronominal questions (with

‘who’ for personal noun phrases and ‘what’ for non-personal) but do not allow adverbial questions for the whole prepositional phrase”.

He adds that “many prepositional verbs allow the noun phrases to become the subject of a passive transformation of the sentence (i.e. They called on the man = The man was called on)”. However, “other prepositional verbs do not occur in the passive freely, but will do so under certain conditions, su as the presence of a particular modal (i.e. Visitors can’t walk over the lawn =The lawn can’t be walked over (by visitors).

The main semantic feature to be mentioned here is that meaning can be deduced from the sum of its individual parts (i.e. His son asked for pocket money)where the preposition may have an emphatic function on the verb (i.e. He objected to do that word). It is relevant to remember that some prepositional verbs may be highly idiomatic, for instance, ‘You must go into the problem’; ‘She has taken to drinking’; and so on.

6. PHRASAL-PREPOSITIONAL VERBS.

Phrasal-prepositional verbs are formed by the structure ‘verb + adverb + preposition’, that are combinations of a verb + adverb + preposition. Note that the majority of them are non- transitive verbs (i.e. We do not get on with our neighbours; Do you go in for squash?). Alike prepositional verbs the stress falls on the adverb or the preposition, the verb being unstressed (i.e. I can’t put ‘up ‘with racism).

Regarding the syntactic functions of phrasal-prepositional,we can analyse them as transitive verbs with the following noun phrase as direct object as with prepositional verbs (i.e. put up with (your behaviour), cut down on (cigarettes), look forward to (the summer holidays), run away with (you), turn out for (a meeting). They may be transitive and intransitive but they do not allow other elements in between the verb and the particles in specific constructions. They can occur in the passive (i.e. Bad manners can’t be put up with for long) and may allow pronominal questions (i.e. What can’t they put up with?) but not adverbial questions.

Regarding their semantic features, we must say that “like phrasal and prepositional verbs, these multi-word verbs vary in their idiomaticity. Some, like ‘stay away from (=avoid), are easily understood from their individual elemtns, though often with figurative meaning (i.e. stand up for =support). Others are fused combinations, and it is difficult or impossible to assign meaning to any of the parts (i.e. put up with=tolerate). There are still others where there is a fusion of the verb with the first particle or where one or more of the elements may seem to retain some individual meaning. For instance, ‘put up with’ also means ‘stay with’, and in that sense ‘put up’ constitutes a unit by itself.

However, they may vary in their idiomaticity since verbs such as ‘stay away from my children’ or ‘I face up to everyday problems’ are easily understood from their individual elements whereas verbs such as ‘You always stand up for my ideas’ and ‘look forward to seeing you again’ have figurative or idiomatic meaning. Often, in other combinations it is difficult or impossible to assign meaning to any of the parts (i.e. She can’t put up with her husband manias).

7. SPECIFIC IDIOMATIC CONSTRUCTIONS.

Specific idiomatic constructions are drawn from the structures ‘verb + noun + preposition’ (i.e. catch sight of, keep track of) or ‘verb + adjective’ (i.e. cut short, wash clean, work loose) which cannot be modified nor can they become the subject of a passive sentence. Consider: ‘We caught sight of the plane’ vs. ‘We caught sudden sight of the plane’ where the former is the correct sentence because of its idiomaticity. Regarding the phonological features in specific idiomatic expressions, the stress falls on the noun after the verb, for instance, ‘You can take ‘advantage of your economic position).

Regarding the syntactic functions of these specific idiomatic constructions, they are considered to be transitive verbs with the following noun phrase as direct object as with prepositional verbs. Since they do not allow other elements in between the verb and the particles in specific constructions, they cannot occur in the passive (i.e. Active: They kept track of all his movements; Passive: Track was kept of all his movements – NOT).

Semantically speaking, they are considered then as indivisible units ha ving the function ofpredicator in the structure of the sentence” being this the main reason for multi-word verbs to be monotransitive (i.e. catch sight of, keep track of, take notice of, take advantage of, etc) but other similar verbs + noun + preposition sequences resemble them in that the constituent that follows them can become the subject of a passive sentence (i.e. His illness should have been made allowance for, He was last caught sight of disappearing in the river).

8. EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS.

The different multi- word verbs dealt with in this study are so relevant to the learning of a foreign language since differences between the vocabulary related to multi-word verbs of the learner’s native language (L1) and that of the foreign language (L2) may lead to several problems, such as the incorrect use of their structures and that foreign learners seldom master them under current teaching conditions.

For instance, the most common mistakes for Spanish students, both at ESO and Bachillerato level, is to use incorrectly some phrasal verbs (i.e. When does he lunch? instead of When does he have lunch?). Often, they make serious grammatical mistakes. In the Spanish curriculum (B.O.E. 2002), the use of multi-word verbs is envisaged at all levels. For instance, in earlier stages of ESO the use of simple verbs is reflected in the use of everyday life or any other specific topic. (get up, have breakfast/lunch/dinner, get dressed, be good at, have fun, etc).

Up to higher stages of Bachillerato, we are dealing with more complex verbal forms, such as the co-occurrence of patterns, whereby idiomatic phrasal verbs may be substituted by synonyms (i.e. ‘die out=disappear’, ‘bring up=educate’, ‘turn down=refuse’, etc; prepositional verbs (i.e. depend on, believe in, speak to, agree with, etc); verb + noun+ preposition (i.e. take care of, give advice on, catch sight of, have control of, etc);verb + adjective (i.e. get asleep, get married, go blind); and above all, idiomatic expressions in certain multi-word verbs (i.e. to be fed up with, to get on with, to give on to, etc).

So, the importance of how to handle these multi-word verbs cannot be understated since it may cause important misunderstandings because of the relevant distinction of meaning between the different types and their structures. We must not forget that Spanish students are likely to use one-word verb rather than using multi- word verb structures (i.e. He stopped smoking vs. He gave up smoking), especially when they are idiomatic phrasal verbs and they do not handle their meaning.

Current communicative methods foster the ‘teaching’ of this kind of specific linguistic information to help students recognize the main differences with the L2 words. Learners cannot do it all on their own. Language learners, even 2nd year Bachillerato students, do not automatically recognize similiarities which seem obvious to teachers; learners need to have these associations brought to their attention.

Therefore, this study is mainly intended for teachers to help Spanish-speaking students establish a relative similarity between the two languages that would find it useful for communicating in the European framework we are living in nowadays. We hope students are able to understand the relevance of handling correctly the expressio n of multi-word verbs to successfully communicate in everyday life.

9. CONCLUSION.

All in all, although the question ‘What is an multi-word verb?’ may appear simple and straightforward, it implies a broad description of the multi-word verb structure in terms of morphology, phonology, syntax, semantics and use which, combined, give way to the study we have presented here. The appropriate answer suitable for students and teachers, may be so simple if we are dealing with ESO students, using simple multi-word verbs or so complex if we are dealing with Bachillerato students, who must be able to handle more complex verb structures.

So far, in this study we have attempted to take a fairly broad view of multi-word verbs since we are also assuming that there is an intrinsic connexion between its learning and successful communication because of the importance of using them in colloquial speech. Yet, we have provided a descriptive account of Unit 22 dealing with Multi-word verbs whose main aim was to introduce the student to the different paradigms that shape the whole set of this specific type of verbal combinations in the English language.

In fact, the correct expression of multi-word verbs is currently considered to be a central element in communicative competence and in the acquisition of a second language since students must be able to use and distinguish these forms in their everyday life in many different situations.Therefore, it is a fact that students must be able to handle the four levels in communicative competence in order to be effectively and highly communicative in the classroom and in real life situations, now we are part of the European Union.

To sum up, we have attempted in this discussion to provide a broad account of multi-word verbs by means of form, function and use within verb phrase morphology, phonology, syntax, semantics and usage in order to set it up within the linguistic theory, going through the localization of multi-word verbs in syntactic structures, to a broad presentation of the main grammatical categories involved in its expression.

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY.

– Aarts, F., and J. Aarts. 1988. English Syntactic Structures. Functions & Categories in Sentence Analysis. Prentice Hall Europe.

– B.O.E. RD Nº 112/2002, de 13 de septiembre por el que se establece el currículo de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria/Bachillerato en la Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia.

– Council of Europe (1998) Modern Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. A Common European Framework of refer ence.

– Greenbaum, S. 2000. The Oxford Reference Grammar . Edited by Edmund Weiner. Oxford University Press.

– Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leach, G., and J Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. Longman.

– Sánchez Benedito, F. 1975. Gramática Inglesa. Editorial Alhambra.

– Thomson, A.J. and A.V. Martinet. 1986. A Practical English Grammar. Oxford University Press.

– Wyss, R. 2002. Teaching English multi-word verbs is not a lost cause afterall . Article 90, March 2002. The weekly column.