Have you ever noticed how many movies there are with war in the name? This list ranks the best movies with war in the title, regardless of genre or rating. What is your favorite movie with war in the name? This is kind of an odd way to categorize movies, but that’s also why it’s so fun! There are probably one or two movies with war in the title that you instantly think of, but you might be surprised how many others there are too as you scroll through this list.

This ranked poll of films with war in the title includes movies like War of the Worlds, World War Z, and The War of the Roses. Don’t forget that this list is interactive, meaning you can vote the film names up or down depending on much you liked each movie that has the word war in it.

-

1

- Released: 2016

- Directed by: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo

Political pressure mounts to install a system of accountability when the actions of the Avengers lead to collateral damage. The new status quo deeply divides members of the team. Captain America …more

-

2

- Released: 2018

- Directed by: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo

Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk and the rest of the Avengers unite to battle their most powerful enemy yet — the evil Thanos. On a mission to collect all six Infinity Stones, Thanos plans to use the …more

-

3

- Released: 2011

- Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Albert (Jeremy Irvine) and his beloved horse, Joey, live on a farm in the British countryside. At the outbreak of World War I, Albert and Joey are forcibly parted when Albert’s father sells the horse …more

-

4

- Released: 1953

- Directed by: Byron Haskin

This film is a 1953 American Technicolor science fiction film from Paramount Pictures, produced by George Pal, directed by Byron Haskin, and starring Gene Barry and Ann Robinson. The film is a loose …more

-

5

The World at War is a 1942 documentary film produced by the Office of War Information. One of the earliest long length films made by the government during the war, it attempted to explain the large …more

-

6

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara is a 2003 American documentary film about the life and times of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara illustrating his …more

Pick one:

| Star Wars: Episode IV- A New Hope | |

| War of the Worlds (2005) | |

|

War

Added by jlhfan624 |

|

|

The War Of The Roses

Added by Vishee |

|

|

Charlie Wilson’s war

Added by House34 |

|

|

is the choice you want missing? go ahead and add it! |

|

view results

| |

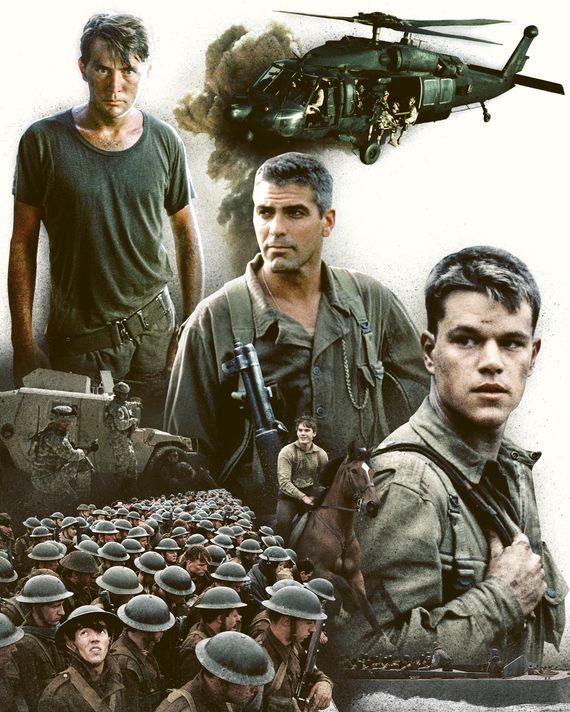

vulture lists

Updated

Mar. 11, 2023

A look back at a genre that has inspired a century of cinema.

Photo-Illustration: Vulture and Courtesy of the Studios

Photo-Illustration: Vulture and Courtesy of the Studios

Photo-Illustration: Vulture and Courtesy of the Studios

This article originally ran in 2020.

Speaking to Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune in 1973, Francois Truffaut made an observation that’s cast a shadow over war movies ever since, even those seemingly opposed to war. Asked why there’s little killing in his films, Truffaut replied, “I find that violence is very ambiguous in movies. For example, some films claim to be antiwar, but I don’t think I’ve really seen an antiwar film. Every film about war ends up being pro-war.” The evidence often bears him out. In Anthony Swofford’s Gulf War memoir Jarhead, Swofford recalls joining fellow recruits in getting pumped up while watching Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket, two of the most famous films about the horrors of war. (On the occasion of the death of R. Lee Ermey, the real-life drill instructor who played the same in Full Metal Jacket, Swofford offered a remembrance in the New York Times with the headline “Full Metal Jacket Seduced My Generation and Sent Us to War.”)

Is it true that movies glamorize whatever they touch, no matter how horrific? And if a war movie isn’t to sound a warning against war, what purpose does it serve? Even if Truffaut’s wrong — and it’s hard to see his observation applying to at least some of the movies on this list — it might be best to remove the burden of making the world a better place from war movies. It’s a lot to ask, especially since war seems to be baked into human existence.

So, like other inescapable elements of the human experience, we tell stories about war, stories that reflect our attitudes toward it, and how they shift over time. War movies reflect the artistic impulses of their creators, but they also reflect the attitudes of the times and places in which they were created. A World War II film made in the midst of the war, for instance, might serve a propagandist purpose than one made after the war ends, when there’s more room for nuance and complexity, but it also might not.

Maybe the ultimate purpose of a war movie is to let others hear the force of these stories. Another director, Sam Fuller, once offered a quote that doesn’t necessarily contradict Truffaut’s observation but better explains the impulse to make war movies: “A war film’s objective, no matter how personal or emotional, is to make a viewer feel war.” The films selected for this list of the genre’s most essential entries often have little in common, but they do share that. Each offers a vision that asks viewers to consider and understand the experience of war, be it in the trenches of World War I, the wilderness skirmishes of Civil War militias, or the still-ongoing conflicts that have helped define 21st-century warfare.

Compiled as Sam Mendes’s stylistically audacious World War I film, 1917, hit theaters, this list opts for a somewhat narrow definition of a war movie, focusing on films that deal with the experiences of soldiers during wartime. That means no films about the experience of returning from war (Coming Home, The Best Years of Our Lives, First Blood) or of civilian life during wartime (Mrs. Miniver, Forbidden Games, Hope and Glory) or of wartime stories whose action rests far away from the battlefield (Casablanca). It also leaves films primarily about the Holocaust out of consideration, as they seem substantively different from other sorts of war films. Also excluded are films that blur genres, like the military science fiction of Starship Troopers and Aliens (even if the latter does have a lot to say about the Vietnam War). That eliminates many great movies, but it leaves room for many others, starting with a film made at the height of World War II in an attempt to help rally a nation with a story of an operation whose success required secrecy, extensive training, and beating overwhelming odds.

War movies released during wartime rarely have time to reflect. If bolstering the morale of a country in the thick of World War II isn’t the sole purpose of Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, it’s certainly one of the primary reasons it exists, retelling the story of the first air raid on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Men head bravely into battle. Women accept their separation and sacrifices with a brave face. And everyone understands it’s for the greater good. However, the film, directed by Mervyn LeRoy from a script by Dalton Trumbo, easily transcends propaganda by focusing on the details of the raid’s preparation and aftermath. LeRoy depicts the attack with chilling intensity, but it’s the time spent with the crew, led by Van Johnson, that makes the movie memorable. (This is as good a point as any to note that Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo makes frequent, unapologetic use of a widespread wartime anti-Japanese racial slur, a warning that applies to virtually every World War II film set in the Pacific and made in the decades after the war.)

To drive home the importance of disease prevention, confidentiality, weapons maintenance, and other crucial wartime topics, the U.S. War Department commissioned a series of animated shorts starring Private Snafu, a dull-witted, mistake-prone soldier created by Frank Capra. The name alone suggests these were cartoons for grown-ups as Snafu was short for “situation normal all fucked up,” (or “fouled,” if you preferred). Primarily written by Theodor Geisel, the future Dr. Seuss, and animated by Warner Bros. directors like Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, and Frank Tashlin, the series appropriates the anarchic approach of Looney Tunes shorts for a practical purpose. Booby Traps, directed by Bob Clampett, typifies the series, using silly gags and racy humor to convey ways of avoiding booby traps when moving into territory surrendered by the enemy. The Mel Blanc–voiced Snafu is a dope who makes mistakes so that others might learn from them (even if he occasionally dies or goes insane in the process). The shorts provide a window into the dos and don’ts of a World War II grunt’s everyday life, but they also remain quite funny, and provide a sense of what some of the day’s top animators might have done if they didn’t have to keep their material (mostly) kid-friendly. (Currently unavailable)

Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of a 1982 novel that found a second life as a much-loved play in the aughts follows a young soldier named Albert (Jeremy Irvine) and his horse Joey on an episodic journey across World War I Europe. There they find no glory in fighting, just cruelty, absurdity, and horror. Albert finds moments of grace and hope in the midst of the bloodshed, thanks to Joey’s unlikely survival. Yet, in a film that draws heavily on the imagery and attitudes of John Ford, Spielberg always emphasizes such moments’ fragility. It’s a hard world for hoofed things, and those who love them.

The first Hollywood film about the Gulf War, the Edward Zwick–directed Courage Under Fire was also one of the first to address the then-hot-button issue of women in combat. But it’s not primarily about either thing. Instead, this Rashomon-inspired drama explores what it takes to act honorably under the most trying circumstances imaginable. Denzel Washington plays Lieutenant Colonel Serling, who’s charged with uncovering the truth about an incident that may lead to the late Captain Karen Walden (played in flashbacks by Meg Ryan) to becoming the first woman to receive a Medal of Honor. The deeper he dives into the story, however, the more contradictions he finds — all while struggling with a secret of his own. The film works both as a mystery and a character study, and Washington’s performance beautifully conveys the unspoken pain of a man who comes to realize that he’ll never be able to shake off the burden of the past.

Blending new, narrative scenes with documentary footage, Stuart Cooper’s Overlord follows a sensitive young soldier named Tom (Brian Stirner) from his enlistment through the D-Day Invasion. A sense of inevitability hangs over the film, both because Tom keeps imagining his death and because the documentary scenes make him feel like a part of a story that’s already been written. The mix of dreamlike asides and historical footage gives the film a feeling like no other as it mourns, and honors, the many lost in the war by focusing on the life of a single soldier.

Brian De Palma’s brutal, fact-inspired film about the kidnapping, rape, and murder of a young Vietnamese woman didn’t catch on with audiences, helping to end the cycle of ’80s Vietnam War films and sidelining star Michael J. Fox’s attempt to cross over to more dramatic roles. It remains a tough film to watch, in part because De Palma shifts his skills as a creator of tense suspense films to a story of unbearable sadness in which a group of American soldiers (whose ranks include John C. Reilly and John Leguizamo in their film debuts) uses the permission of a violent, charismatic superior (Sean Penn) to engage in barbaric acts. Fox’s casting as the film’s moral center, and a man who suffers for his honesty, feels disorienting at first, but it works. Marty McFly looks out of place in such an awful situation, but that only drives the point home.

A film about the hero of one American war, made as another loomed on the horizon, Howard Hawks’s biopic of Alvin York (Gary Cooper) depicts its protagonist’s military service as the final part of his evolution from a backwoods Tennessee hell-raiser into a self-sacrificing warrior willing to put the good of others above his own. Along the way, York wrestles first with his anger then with his religious beliefs, which he believes forbid him from fighting. The film’s version of the Army — a caring institution deeply concerned with the happiness and well-being of its soldiers and willing to allow time for reflection for those who doubt the rightness of its mission — may be pure fiction, but Cooper’s unerring sincerity and Hawks’s firm command of the transformative story make this a moving depiction of one man’s moral development.

This violent account of an ill-fated 1993 raid in Mogadishu that left 19 American soldiers dead found a receptive audience in the first winter after 9/11, and its politics very much remain a matter of debate. At least on a technical level it’s a remarkable achievement, one in which Ridley Scott brings the full force of his directorial skills to bear on an often chaotic story with a sprawling cast of characters (made up of virtually every up-and-coming male star of the late-’90s). Scott’s never been associated with documentary-like realism, but here he uses his talent for capturing the intensity of a single moment to create a collection of fragments that cohere into a fully developed story. Criticized by some for glorifying combat, it has lately started to seem more about the perils of believing American force alone can fix a troubled country.

Inspired by a real incident, this John Frankenheimer film stars Burt Lancaster as Labiche, a no-nonsense French resistance fighter who reluctantly matches wits with the German Colonel von Waldheim (Paul Scofield), a murderous aesthete intent on returning to Germany with a train filled with priceless art. Labiche’s plan involves a mix of deception and brute force, and Frankenheimer ramps up the tension as Labiche’s determination mounts. The tension comes both from the battle of wits between von Waldheim and Labiche, which Frankenheimer stages as a series of escalating conflicts that unfold over the length of the train’s journey, but also from Frankenheimer’s depiction of how the cost of war extends far beyond the battlefield. Labiche doesn’t care for art, but he comes to recognize what the stolen treasures mean for a country struggling to hold on to its soul.

A reverence for history and a love for the material gives shape to Michael Mann’s moody adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, starring Daniel Day-Lewis as Hawkeye, the adopted son of the Mohican chief Chingachgook (Russell Means). Mann brings a typically obsessive attention to detail to the extensively researched film, set at the height of the French and Indian War when the war had extended to terrain not far removed from wilderness, but he also allows displays of open emotion — and unabashedly sweeping filmmaking — rarely seen in his other movies. Mann has said that he saw the 1936 adaptation at the age of 3 and it had been “rattling around” in his brain ever since. His Mohicans plays like the work of a director trying to figure out what in all those images of combat and doomed love moved him so much then and how he could use his own voice to have the same effect on others.

Winner of short subject awards at Cannes and the Oscars, French director Robert Enrico’s adaptation of an Ambrose Bierce story offers a succinct, haunting depiction of a second chance that’s not what it first appears. Roger Jacquet plays a Confederate saboteur on the verge of being executed by hanging as the film begins. Then the rope snaps, allowing him to make a desperate attempt to return to the life he left behind until … Well, there’s a good chance you know what happens next, but let’s not spoil it. Enrico’s film became the only outside production to air as part of The Twilight Zone. That’s where most viewers encountered the virtually dialogue-free film, a depiction of a final chance to consider what really matters even in the midst of war.

The work of a director never afraid to court controversy, Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence explores the abusive excesses — and barely concealed desire — running through a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in Indonesia. There, a British Lieutenant Colonel John Lawrence (Tom Conti), previously stationed in Japan and fluent in the language, tries to maintain some semblance of civility by communicating with the mercurial Sergeant Hara (Takeshi Kitano, then best known as a comic on Japanese television). The introduction of the charismatic and seemingly unflappable British Major Jack Celliers (David Bowie) complicates an already tense situation, particularly once it becomes clear that Celliers has become an object of obsession for the camp’s captain (Ryuichi Sakamoto, who also provides the score). Oshima’s film teases out the homoeroticism coursing beneath the environment (and coursing through many a war movie, for that matter), in the process commenting on two different cultures that express such feelings through denial and brutality. Some seeds of hope slip through, but Oshima suggests they’ll struggle to survive in such arid terrain.

A different sort of power struggle lies at the heart of Run Silent, Run Deep, Robert Wise’s adaptation of a best-selling novel following one U.S. sub crew’s troubled mission through the South Pacific. Clark Gable stars as Commander Richardson, a commander with a chip on his shoulder, and possibly a death wish, after losing a ship and much of his crew to a Japanese destroyer. One year later, Richardson gets a shot at revenge, but only by assuming control of a sub from its apparent next commander, the popular Lieutenant Colonel Bledsoe (Burt Lancaster). They keep it professional even though the crew chooses sides as Richardson puts them through an exhausting barrage of drills; however, tensions mount when it becomes apparent that Richardson is pursuing a vendetta outside the parameters of his official order. The submarine movie is practically a genre unto itself, and Wise’s contribution is one of the best, capturing the pressure and barely suppressed hostility of a job that’s dangerous even before the torpedoes start flying — and one in which indecisiveness and divided loyalties can mean death for everyone aboard.

David O. Russell’s Three Kings begins as a darkly comic heist film in which three soldiers (George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg, and Ice Cube) try to make an easy score in the chaos at the end of the Persian Gulf War. It develops into a tour of the human costs and unfinished business of that conflict as the three get drawn into the plight of refugees trying to avoid the wrath of the Iraqi Republican Guard. The film both captures and questions the spirit of the moment — in which patriotism embraced a quick, decisive Gulf victory — and previews the century to come, one that would erase the distance between the Middle East and the United States. The heroes try to get in and out without really getting involved or inviting any consequences. They find that’s impossible.

Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski’s play drawing from their POW experiences provide Billy Wilder with a chance to bring a touch of black comedy to a World War II story that opens with a narrator complaining that prisoners of war like him never get movies of their own. (That was true up to a point at the time; Bridge on the River Kwai and The Great Escape wouldn’t show up for a few years.) Opening with a failed escape attempt, the film finds tensions running high as a group of American prisoners come to realize that they have an informer in their midst. Suspicions quickly fall on Sefton (William Holden), a cynical operator who’s cornered the prison’s black market and holds regular “horse races” in which men bet on mice named after famous racehorses. Sefton insists on his innocence, however, and attempts to find the real informant while turning the tables on the camp’s officious commandant (Otto Preminger). Wilder’s the last filmmaker to indulge in sentiment or knee-jerk patriotism, but this sharp, tense, funny film allows him to depict American perseverance against cruelty and authoritarianism in a style that suits him.

An adaptation of Daniel Woodrell’s 1987 novel Woe to Live On, Ang Lee’s Ride With the Devil drops viewers into the chaotic world of Civil War guerrilla fighting. Tobey Maguire and Skeet Ulrich star as a pair of Missouri Bushwhackers who tangle with pro-Union Jayhawkers in conflicts far removed from the war’s front lines. Their war becomes a bloody journey of discovery, particularly after they make the acquaintance of a former slave named Holt (Jeffrey Wright). Lee’s film doesn’t go out of its way to explain its context, which proved off-putting to some critics in 1999 (and apparently to moviegoers, who largely ignored it). While it helps to bring some Civil War knowledge to the film, the confusion suits a story that’s ultimately about the many tangled reasons we go to war, and the much clearer reasons the experience of war makes us strive to leave it behind.

Steven Soderbergh’s two-part Che is at once biopic and war movie, telling the story of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara (Benicio del Toro) by way of his participation in a successful revolution in Cuba and his participation in a failed attempt at the same in Bolivia. Soderbergh brings a distinctive look and filmmaking style to each half, both of which offer a nuts-and-bolts depiction of how guerrilla warfare works — in success and failure. The thrilling door-to-door urban combat of the first half gives way to the chaos and failure of the second. Anchored by del Toro’s enigmatic performance, they combine to form a portrait of a complex man that gets beyond the T-shirt iconography of would-be revolutionaries.

Journalist Ernie Pyle earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for his on-the-ground reporting covering World War II from the perspective of an ordinary soldier. Released a few months after Pyle’s death in the Battle of Okinawa, this William Wellman film stars Burgess Meredith as Pyle, who joins the 18th Infantry and befriends the men fighting on the front line, including Robert Mitchum (who earned a Best Supporting Actor nomination for his work) as a commander whose apparent standoffishness can’t mask the toll exacted by his job. No stranger to combat, or films about it, Wellman’s direction matches Pyle’s no-nonsense style, paying tribute to the men it depicts by letting them speak in their own voices.

The subject of controversy since its release, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter offered almost unbearably intense scenes of the Vietnam War at a time when mainstream movies were just beginning to touch on the still-fresh subject. Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, John Savage, and John Cazale star as a group of Polish-Americans from Pennsylvania’s Rust Belt whose lives are reshaped in different ways by the war. Cimino’s films drew criticism for its depictions of the Vietnamese, and its sensationalized scenes of Russian roulette, but the heart of the film belongs to its depiction of small-town America. The nearly hour-long wedding scene that opens the film captures a sense of warmth and tradition that has all but vanished by the film’s final moments, lost somewhere overseas.

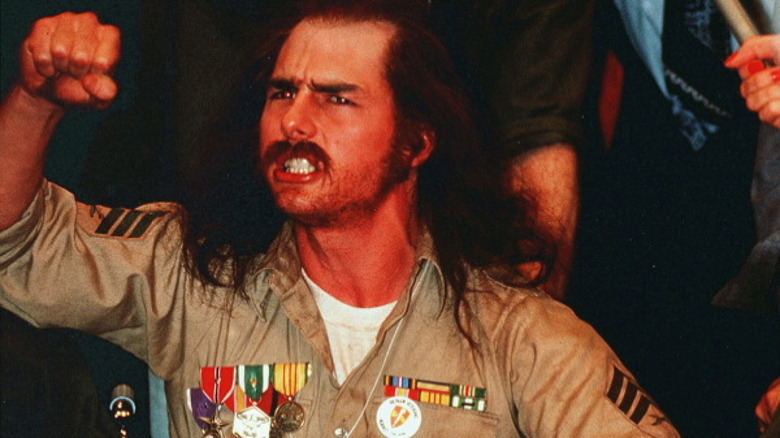

A searing indictment of American cultural imperialism and an unsparing depiction of the experiences of Black soldiers during the Vietnam War in the form of an adventure film, Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods follows veterans Paul, Otis, Eddie, and Melvin (played respectively by Delroy Lindo, Clarke Peters, Norm Lewis, and Isiah Whitlock Jr.) as they return to Vietnam in search of a treasure they had to abandon during a battle that took the life of their idealistic leader, Norman (Chadwick Boseman). Over the course of their journey, the film flashes back to their wartime experiences, forcing each of the men to reflect on where the years have taken him. From a scene set at a (real-life) nightclub named after Apocalypse Now to the decision to have the older actors play themselves in flashback, Lee keeps finding ingenious ways to blur the line between Vietnam’s past, its present, and the films about the war. In Lindo’s wrenching performance as a morally adrift powder keg wearing a MAGA cap, he has found the embodiment of the conflict’s lingering trauma.

Though star John Wayne famously never served in the military, many of those involved in making John Ford’s They Were Expendable had seen World War II firsthand in one form or another. That helps account for the dutiful but often grim tone of the film, in which a pair of Navy men (Wayne, Robert Montgomery) try to convince the higher-ups that their small, maneuverable PT boats have a place in battles others believe will be dominated by larger vessels. Set in the early days of America’s involvement in World War II, when one setback followed another, the film never lets viewers forget the human costs of war, how soldiers’ lives become means to an end, and how service means living with that knowledge at every moment. Naturally, the “they” of the title refers to more than boats.

Based in part on his own experiences serving in the Army in Hawaii in the days before the Pearl Harbor attack, James Jones’s 1951 novel From Here to Eternity won scandal and acclaim for its often unflattering depiction of military life. Even though it tones down some elements of the book, Fred Zinnemann’s adaptation met with a similar reception thanks to its unvarnished depiction of abuse, extramarital passion, and boozy off-hours — a far cry from the unabashedly heroic portrayals of the American military that preceded it during the war. Montgomery Clift plays a principled bugler who suffers abuse for his unwillingness to join the camp’s boxing team, starring opposite Burt Lancaster as a world-weary desk sergeant whose affair with his commanding officer’s wife (Deborah Kerr) threatens to undo his career. The cast of complicated characters extends to Donna Reed, Ernest Borgnine, and Frank Sinatra. Cast, like Kerr, against type, Reed picked up a Best Supporting Actress Oscar and Sinatra won the corresponding prize for his work as a self-destructive private, two of seven trophies earned by the film, including Best Picture and Best Director. Lancaster and Kerr’s heated beach embrace helped make Hollywood films safe for franker depictions of sex, and the awards suggested that America was again ready to see its soldiers as human beings, flaws and all.

Between 1945 and 1946, Roberto Rossellini released three movies depicting various phases of World War II. Surrounded by Rome, Open City and Germany Year One — both excellent in their own right — Paisan moves up through the Italian peninsula via six episodic stories about the Italian campaign. Made not long after the events depicted, Rossellini uses his neorealist style to great effect, filming on location and mixing professional and nonprofessional actors to capture the perils and ugliness of the war — both for those who fight it and for the everyday people they liberate. To capture the devastation of the war on Italy (and, in a later episode, Germany), Rossellini had to do little but pick up a camera and film. Created in part via on-the-spot improvisations by his cast, Paisan has the immediacy of lived experience.

Named for the long, bloody World War I campaign to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula, Peter Weir’s Gallipoli at first seems misnamed. It doesn’t even reach Gallipoli until deep into its running time, and doesn’t depict much combat until its final scenes anyway. Yet the film owes much of its effectiveness to Weir’s slow march to a bloody finale, following a pair of sprinters of contrasting temperaments (Mark Lee and Mel Gibson) from their homes in Western Australia through a long journey that spans enlistment, training against the backdrop of Egypt’s pyramids, and finally to the beachside trenches of Gallipoli. Along the way, they encounter increasing skepticism about why Australians should fight the war as the film around them attempts to convey the futility and loss of fighting any war, and the stolen promise of lives that become just another body on the battlefield.

Sometimes dubbed the Forgotten War, the Korean War has only inspired a handful of American films, most made when it was still in progress. Sam Fuller directed two of them, the quite good Fixed Bayonets! and the even better The Steel Helmet. Gene Evans stars in both, in the latter playing Sergeant Zack, a cigar-chomping, seen-it-all veteran with little time for inexperienced officers or anyone else who gets in his way. After befriending a young Korean boy he dubs Short Round (a name Steven Spielberg and George Lucas would later borrow), Zack finds himself holed up in a Buddhist temple with a handful of soldiers who may not be powerful enough to fight off the encroaching enemy. Drawing on his own military experience, Fuller uses the claustrophobic setup — and a limited budget — to stage a psychologically intense story that finds every character considering their limits. That includes African-American and Japanese-American soldiers needled by a North Korean prisoner about their country’s hypocrisy. For Fuller, the best sort of patriotism meant not looking away from your country’s flaws, even while fighting for it.

General George S. Patton believed himself to be the reincarnation of soldiers serving the Roman Empire and Napoleon, among other past lives. While this belief and others made those around him view him as eccentric (or worse), it also captured the temperament of a man who saw himself as a soldier first and couldn’t picture himself serving any other function in life. Co-written by Edmund H. North and Francis Ford Coppola, Franklin J. Schaffner’s epic-scaled biopic focuses on Patton’s World War II experience. That’s more than enough to fill a film, and more than enough to offer a complex, nuanced, often unflattering depiction of the hard-charging general whose victories in North Africa, Sicily, and elsewhere could be overshadowed by diplomatic gaffes, a megalomaniacal temperament, and abusive incidents, like the assault of shell-shocked soldiers he labeled cowards. The film reduces two such incidents into one, but it otherwise doesn’t let Patton off easy, giving room for George C. Scott’s full-bodied performance to capture the complexity of a born soldier for whom glory and ugliness often went hand in hand.

Shot on location and filled with nonprofessional actors, Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers chronicles the clash between forces of the French government and rebels in the Algerian capital during the Algerian War. The film has the look and feel of a documentary, but its commitment to realism doesn’t end with its style. Pontecorvo details the often horrific methods used in both sides of the conflict, from torture to bombings targeting civilians. The director claimed he set out to make an objective, politically neutral account of the conflict. If its sympathies can’t help but tilt a little toward the colonized, the film still plays like a nightmare in which every escalation kills more innocents and every victory comes at a horrible cost.

Oliver Stone drew on his own experiences in Vietnam for this tale of a privileged Army private Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) who enlists out of a desire to serve his country but finds himself overwhelmed by the on-the-ground moral compromises that service seems to require. Platoon won acclaim — and multiple Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director — in part because of its realistic battle scenes and attention to the everyday details of fighting in the war. Beneath those elements, Stone stages an almost operatic struggle for Chris’s soul with the hardened Sergeant Barnes (Tom Berenger) and the more compassionate Sergeant Grodin (Willem Dafoe). Platoon’s most memorable achievement, however, is the way it captures the cloudiness and confusion of fighting a war in which the demands of his superiors, and the desire to survive, can blur the divide between good and evil.

With a few notable exceptions, like The Great Escape, by the mid-’60s American World War II films had started to feel pretty square. Robert Aldrich’s violent, high-spirited The Dirty Dozen tapped into the spirit of the era, bringing in a remarkable cast (Charles Bronson, Jim Brown, John Cassavetes, Telly Savalas, and Donald Sutherland among them) to play a band of military convicts gathered by an OSS officer (Lee Marvin) to perform a dangerous behind-enemy-lines mission in the lead-up to D-Day. Aldrich brings a light touch to the film’s opening acts, as the characters meet, take a dislike to one another, but bond as a team anyway. But the unsparing final stretch leads to a sobering body count and some unavoidable acts of violence that look far from heroic. War can be a romp until the bloodshed starts.

After depicting the Battle of Iwo Jima and its aftermath from the American side with Flags of Our Fathers, Clint Eastwood revisited the event from the perspective of Japanese soldiers with its companion piece, Letters From Iwo Jima. Eastwood unrelentingly depicts the desperation of the Japanese soldiers’ last stand, defending their position from tunnels as they ran out of resources and succumb to disease. But it’s the time spent with the soldiers, particularly a private and a general (played, respectively, by Kazunari Ninomiya and Ken Watanabe), that makes the film unforgettable. By the film’s end, viewers understand everything that led the men to this moment — from those drawn by a sense of honor to those compelled by the inescapable edicts of the Japanese government — putting human faces on one of the war’s pivotal moments.

Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s landmark novel focuses on the experiences of a handful of German schoolboys inspired to serve in World War I by a teacher’s patriotic propaganda, after which they enjoy a few moments of glory before being thrust into the hell of war itself. Milestone depicts the awfulness of a World War I soldier’s life, one in which there’s never enough food, exploding shells make sleep impossible, and virtually any injury can turn fatal. The film’s elaborate battle scenes make extensive use of sound, an only recently introduced cinematic innovation that Milestone uses to assault viewers. (Some of the performances, on the other hand, haven’t quite figured out how to adjust to the sound era.) Though told from the perspective of German soldiers, the film works less as a critique of one country’s approach to war than war in general, leading to a set of devastating final shots that capture what it means to send a whole generation off to fight, and what’s lost when they don’t return. A Best Picture winner, its inspiration — from its intense battle scenes to the suggestion that war goes against nature — can be seen in virtually every war film that followed.

The first half of Stanley Kubrick’s contribution to the wave of ’80s Vietnam movies tends to get more praise than the second, but they ultimately tell two parts of the same story. The first follows J.T. “Joker” Davis (Matthew Modine) through basic training, a dehumanizing process designed to turn young men into killing machines — unless, like Vincent D’Onofrio’s “Private Pyle,” they break in the process. In the second, Joker tries to hold on to the shreds of his humanity that he’s been able to preserve in the midst of the war, which Kubrick stages as a surreal swirl of violence and confusion in which nothing delicate and meaningful can survive. D’Onofrio conjures the look of a man who’s died on the inside. It’s echoed in the second half by the Vietnamese prostitutes unconvincingly asserting their sexual desire (a scene famously sampled in 2 Live Crew’s “Me So Horny”), unable to hide their boredom as they sell their bodies. Even those who survive war end up hollowed out on the inside, one way or another.

The ideal to which many subsequent star-packed World War II films aspired, John Sturges’s The Great Escape fills a German POW camp with James Garner, Richard Attenborough, Charles Bronson, Donald Pleasence, James Coburn, and, most memorable of all, Steve McQueen as allied prisoners determined to break out. Each brings his own skill to the endeavor, which Sturges shows in meticulous detail. McQueen embodied an anti-authoritarian spirit set to catch fire a few years later in the ’60s, and the film plays like a lighthearted heist film until a violent climax reminds us we’ve been watching a war film all along.

This list doesn’t want for Best Picture winners, among them David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, which also took the prizes for Best Director, Best Actor (for Alec Guinness), and Best Adapted Screenplay (though blacklisted writers Michael Wilson and Carl Foreman wouldn’t receive credit until years later). It’s easy for the Academy to get behind great war movies, which tend to use a spectacle and a grand scope to address weighty themes. Kwai contains all of the above, but it feels remarkably intimate thanks to its focus on a handful of characters played by Sessue Hayakawa, William Holden, Alec Guinness, and others. The product of contrasting cultures, the film finds each figure responding to his experiences as part of a Japanese prison camp in Burma differently — yet none is more fascinating than Guinness’s Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson, who comes to treat the forced construction of the eponymous railway bridge as a test of British gumption. The film treats his obsession as both an admirable manifestation of national spirit and a kind of war-stoked madness whose contradictions remain tangled to the end.

Orson Welles’s long-in-the-works (and long-hard-to-see) adaptation of Shakespeare’s plays featuring the high-living John Falstaff is a great war movie for two reasons. Working on an extremely limited budget, Welles created the illusion of sweeping battle scenes that captured the intensity of medieval combat. But it’s also a film about how war and duty can shut down the better, more joyful parts of our nature. Welles plays Falstaff as an unrepentant rogue, but also as a good man in the ways that truly matter. His estrangement from Prince Hal (Keith Baxter), the man destined to become Henry V, plays as both inevitable and tragic, and the closing observation that Hal became a prudent, humane king who “left no offense unpunished nor friendship unrewarded” rings with both truth and regret.

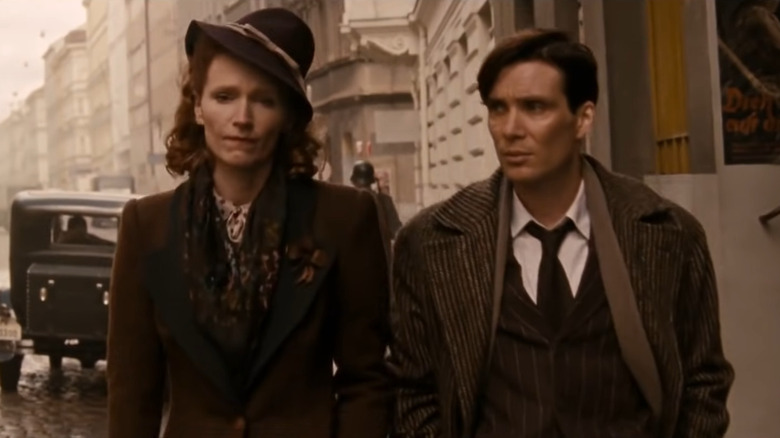

Quentin Tarantino’s sprawling, episodic Inglourious Basterds is a World War II movie informed by the decades of war movies that preceded it and is fully aware of fiction’s ability to reshape history. The film pits, indirectly at first, the pitiless but ingratiating SS Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) against a troop of Jewish-American soldiers under the command of the honey-accented Lieutenant Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt). As his film makes its way toward a final confrontation in Paris, Tarantino touches on everything from the racial subtext of King Kong to the power of propaganda to the ways different eras and subgenres of war films have interpreted World War II — until, finally, Basterds reveals itself as a revenge movie on a historical scale. It’s funny and audacious, but also shot through with a sense of sadness and loss, thanks in large part to Mélanie Laurent’s turn as the sole survivor of an opening scene in which Landa hunts for a Jewish family in hiding. It’s a reminder that while movies might get to rewrite history and even offer a shot at revenge, they can’t really undo it.

A look at life aboard a World War II U-boat, Das Boot adapts a best-selling German novel by Lothar-Günther Buchheim, drawn from his experiences as a war correspondent embedded with a submarine crew during the Battle of the Atlantic. Jürgen Prochnow stars as the experienced and disillusioned unnamed captain whose sense of military duty and commitment to his men overwhelms open distaste for Hitler, Nazism, and the execution of the war. The title, which translates as “The Boat,” captures the spirit of the film. The movie’s opening sets up the force of the military at the height of the war, but the focus soon becomes what it’s like to live underwater in alternately dull and terrifying (and increasingly disgusting) close quarters. Wolfgang Petersen brilliantly uses cramped spaces, the sounds of underwater combat, and the intense performances of a bedraggled cast to create an immersive depiction of submarine service that’s jaundiced about the practice of war even as it captures the bonds needed to stay alive in the midst of it.

Kon Ishikawa didn’t plan to make The Burmese Harp and Fires on the Plain as companion pieces, but his two films about Japanese soldiers in the last days of World War II fit together well. Programmed as a double feature, it’s best to watch Fires on the Plain first to avoid ending in despair. Eiji Funakoshi stars as Tamura, a soldier who begins the film with tuberculosis and whose life only gets worse from there. Denied admission to a field hospital, he’s forced to wander a hellish landscape of the dead, the desperate, and the starving. Ichikawa depicts war as a relentless assault of horror via a story in which survival doesn’t always seem preferable to death. Released three years earlier, The Burmese Harp sounds faint notes of hopefulness in a similar environment via the story of a Japanese private (Shoji Yasui) who comes to realize a higher duty when he disguises himself as a monk in order to survive. The film doesn’t shy away from war’s grimness, but it also depicts the possibility of a hard-won spiritual awakening and some tenuous connections between wartime enemies that could grow stronger now that the fighting’s done. They’re slivers of optimism, but the film suggests they could spread and that maybe, someday, war might end.

Christopher Nolan’s daring account of the Dunkirk evacuation — a humiliating 1940 setback that advanced the German cause — attempts to capture the full scope of the event by depicting it via three differently paced timelines at once. One, the story of some stranded soldiers, unfolds over a week. The second, following civilians attempting to rescue soldiers by boat, is set over the course of a day. A third, in which a pilot storms the beach by air, covers a mere hour. What could have been a cerebral exercise carefully builds the tension on three fronts. A deeply emotional climax and stirring denouement captures the spirit of a nation desperately trying to find sparks of hope under grim circumstances.

The moviegoing public has largely proved resistant to films about the Iraq War, maybe because it remained the subject of heated controversy even as the films started to appear (and remains so today). One exception: Kathryn Bigelow’s Best Picture– and Best Director–winning The Hurt Locker, which doesn’t ignore the politics of the conflict but also focuses on the terrifying experiences of an Explosive Ordnance Disposal team led by William James (Jeremy Renner). Bigelow captures the intensity of a job in which the slightest mistake means death, and how the experience becomes so enveloping that any other way of life starts to feel impossible.

Sam Fuller had already been a crime reporter, pulp novelist, screenwriter, and soldier before he became a director. While he brought his World War II experiences to many of his films, Fuller wrote most of his autobiographical elements into this project, a sprawling war film based on his experiences in the Army’s 1st Infantry Division. He had first tried to film The Big Red One in the 1950s but couldn’t make it happen. Its realization looked increasingly less likely as the years went on, but the always intrepid Fuller persisted. Used to working on small budgets, he barely left Israel to create a war-spanning story that follows a 1st Infantry squad from North Africa, through Italy, D-Day, and finally to a Czech concentration camp. Playing a Fuller surrogate, Robert Carradine co-stars alongside Mark Hamill and Lee Marvin, the latter playing a hardened veteran of both World Wars. Fuller finds creative ways to stage the war on a budget — making particularly ingenious use of a watch during the Normandy sequence — and its limitations ultimately serve the film, keeping the focus on the experiences of a tight band of soldiers as they make their way from continent to continent and, ultimately, to the dark heart of the war itself. In the process, Fuller captures the ravages of war on both soldiers and civilians while also depicting why sometimes fighting becomes the only choice.

Russian director Elem Klimov’s harrowing Come and See opens with a Belarusian teen named Flyora (Aleksey Kravchenko) imitating a soldier as he and a friend dig through a trench looking for guns. In the process, he seems to summon war to his village, first in the form of a partisan militia who enlists him to fight the German invaders, then in the form of the Germans themselves, who arrive not just as conquerors but as gleeful sadists with no regard for human life. An end title notes that 628 Belarusian villages were destroyed in the war “along with all their inhabitants” and that Klimov co-wrote the script with Ales Adamovich, adapting a book based on Adamovich’s experiences in a Belarusian militia. To capture that horror, Klimov uses both a restless camera and heavy use of a Steadicam, gliding through a devastated, perpetually overcast countryside and depicting one disturbing incident after another. Over the course of the film, Flyora’s face becomes a map of trauma (an effect the then-13-year-old Kravchenko achieved partly through hypnotism). It’s a stark, haunting depiction of innocence lost that’s built around unblinking re-creations of World War II atrocities. But it’s mesmerizing, too — a cinematic tour of hell filled with surreal images (see: a Nazi officer carrying a lemur on his shoulder) and overwhelming scenes of chaos. It captures the worst aspects of war in a manner that denies us the ability to look away.

Debuting in the Evening Standard in 1934, cartoonist David Low’s aging, walrus-mustached, potbellied Colonel Blimp came to embody all that was out of touch and out-of-date in a certain type of British military man. Released in the thick of World War II, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp serves as a kind of origin story for the character but also, and above all, as a defense of his place in history and in shaping the national character. Roger Livesey stars as Clive Candy, a lifelong British soldier first seen losing a war-games exercise after his young opponent chooses not to play by the rules. The film then flashes back to Candy’s younger days when those rules still applied. It follows him from an attempt to defend Britain from German propaganda at the turn of the century through the ups and downs that followed. Along the way he falls in love with a series of women played by Deborah Kerr and befriends a German officer (Anton Walbrook) whose attitudes change with the shifting circumstances of his nation. At once comic and elegiac, it’s clear-eyed about the changing times that have made Candy’s notions about the proper way to fight dangerously out-of-date. But it also admires the way he embodies the best traits of an England that prides itself on civility and fair play even in battle — a vision of itself that’s in the process of being forcibly changed by the demands of an enemy that finds no virtue in such values.

Francis Ford Coppola’s loose adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness keeps true to Conrad’s use of a river journey as a trip into the most forbidding reaches of the human psyche while transposing the action to the still-fresh Vietnam War. Martin Sheen stars as Captain Willard, a special-ops soldier charged with ending the career of the insane, abusive, charismatic Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) with “extreme prejudice.” Doing so means making a dangerous journey to a camp that Kurtz rules over like a god, with stops along the way that include time with a battle-happy surf-enthusiast commander of a helicopter unit (Robert Duvall), a USO appearance from some Playboy Playmates that stirs madness, and encounters with locals made tragic by the fog of war. (The extended versions released in 2001 and 2019 include even more episodes, including a French plantation sequence that provides an even stronger connection to the colonialism of Conrad’s book and the colonialist roots of the war.)

Coppola famously had a difficult time making the film, so difficult that his experiences inspired the great making-of doc Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. That chaos may not have been necessary to create the sense of a world spinning out of control, but maybe it didn’t hurt. Sheen plays Willard as a man always on the verge of giving into the madness of the world around him, a world that grows less explicable and crueler the closer he draws to Kurtz. Coppola’s film is disorienting and disturbing, using Vietnam to capture the insanity of all war and drawing on Conrad to suggest that war might just be an outgrowth of an awfulness at the core of humanity itself.

The end of the 20th century stirred a great deal of reflection about what happened in the middle of it, particularly during World War II. The passing of time had done little to make the Second World War look any less like a struggle for the very soul of the planet, one that could easily have been lost at several turning points — the D-Day Invasion of Normandy among them. Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan opens with a harrowing re-creation of that attack, offering a grunts’-eye view of the chaos and a zombie movie’s emphasis on gore. (If a movie could end war just by depicting the horrors of battle, this scene alone would have brought peace on earth.) It’s such an extraordinary sequence that it often overshadows the film that follows, which masterfully depicts the experiences of a handful of soldiers led by Tom Hanks’s tough Captain Miller. The results are wartime experiences without a hint of romance or nostalgia. It’s clear-eyed about the realities of warfare and even questions the group’s mission — the search for a single soldier in order to prevent his mother from losing all four of her sons in war — that’s less a crucial operation than a PR exercise. It never questions the importance of the fight, however, and emerges as a stirring tribute to those who died saving the world in which we now live.

To gauge the effect of this Jean Renoir masterpiece about French WWI POWs and their German captors, it’s worth considering who didn’t want it to be seen. Joseph Goebbels hated it, particularly the way its criticisms of World War I reflected badly on the Germany that initiated World War II, declaring it “Cinematic Public Enemy No. 1.” But it wasn’t just Germany that came to find the film troublesome. Rereleased in France in 1946, the film didn’t sit as well with many French critics, who found its depiction of connections between French and German officers and its pacifist attitude out of step with the times. That reaction makes sense in the immediate aftermath of a war filled with atrocities on a scale never previously seen. But, years later, the mournful quality baked into the film overwhelms those concerns. Renoir fills Grand Illusion with hopeful suggestions that a common humanity can overwhelm nationalism, but also a sense that the possibility for that sort of connection is slipping into the past — along with any sense that war can be a noble exercise. It’s a stunning expression of humanism, but one filled with warnings about how little it takes for such values to fall away.

Terrence Malick’s adaptation of James Jones’s 1962 novel based on his World War II experiences fighting in the Guadalcanal campaign changed shape significantly as it made its way to the screen. Malick’s first film in 20 years, The Thin Red Line attracted the attention of established and rising stars alike, some of whom saw their roles reduced, or even deleted, from the final cut. Somewhere there’s an alternate version of the film in which Bill Pullman, Mickey Rourke, and Lukas Haas appear and Adrien Brody plays a key role rather than popping up for a few minutes of screen time. Malick’s editors, in an interview included in the Criterion Collection’s editions of the film, offer the best explanation for his decision-making. Malick cut the film not to service the plot but to make room for the film’s voice-overs. Paired with stunning images of war in the Pacific, they provide lyrical reflections on the characters’ wartime experiences and the loss of innocence that comes with those experiences. Malick returned from his moviemaking absence in full command of his signature ability to capture wonder, but in depicting a kind of hell on earth, he uses that ability to disorienting effect. Here, war spoils all it touches, from those who partake in it to those swept up in it to the land itself. To Malick, it’s an act of awful defiance against creation.

It’s worth keeping Truffaut’s famous quote (told to the Chicago Tribune in 1973) in mind when thinking about Paths of Glory. If even the most pacifist-minded war films often end up glamorizing war — and Truffaut specifically suggested they did later in the same interview — Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 adaptation of Humphrey Cobb’s World War I novel comes closest to slipping through that trap. Beyond depicting the sheer brutality of trench warfare, it serves as an indictment of the act of war itself. Over the course of the film, officers order soldiers to their death in a battle they know they can’t win, one soldier betrays another to cover up a crime, and the film treats self-sacrifice less as a noble virtue than a value extolled because of its military usefulness. Heroism never enters the picture, apart from the willingness of Kirk Douglas’s Colonel Dax to try to expose the hypocrisy and wrongdoing of executing three men for cowardice.

Kubrick immerses viewers in trench life and drains scenes of recon missions and battle of any glamor. Only the terror remains. But it’s his ability to depict the human cost — on the condemned soldiers, on Dax, and on those who evade justice — that makes the film so haunting as it builds to an extraordinary final scene. Its final moments feature a moving rendition of a song by a German singer (played by an actress credited as Susanne Christian but soon to be known as Christiane Kubrick after marrying the director), leading to a moment of connection and vulnerability for those compelling her to sing. The differences melt away, if only for the length of the song. Then the war begins again.

When Akira Kurosawa made Ran, he knew he had one last chance to make a grand statement. He’d spent years developing the project, a stretch in which he had difficulty securing financing for any sort of film, much less a sweeping epic that would become the most expensive Japanese film made at that point. His eyesight was faltering and the prospect of death never seemed far away. (Indeed, he’d lose his wife of many years while shooting the film.) So he put everything he had into the film, weaving Shakespeare’s King Lear into a story inspired by the life of the 16th-century feudal ruler Mori Motonari. Tatsuya Nakadai plays Ichimonji Hidetora, an aging daimyo determined to split his kingdom among his three sons, one of whom rejects the offer as foolish. The other two bring war to the land via bloody conflicts depicted largely as the result of the ruthlessness with which Hidetora ruled the land.

Ran, which translates as “Chaos,” is both a mammoth film and a tiny one. Kurosawa employed armies of extras — and burned massive sets to the ground — to depict the strife. Simply as a technical accomplishment, it should be on any list of the greatest war films ever made. But it’s also the story of one man’s tragic end and of his horrifying rush of reflection and regret. As Hidetora watches the destruction of everything he’s built, he realizes too late how little his accomplishments matter, how much virtue he’s cast aside to achieve them, and how time humbles even the proudest. All that fighting and death has accomplished nothing. Maybe, as the title suggests, war affronts the natural order and the blood we spill poisons the land for which we fight.

The 50 Greatest War Movies Ever Made

Honorable Mention: Captain America

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Captain America: The First Avenger Trailer 2

Watch on

Yes, it borders on the line of Marvel-induced jingoism and it’s a superhero movie that surely doesn’t shine a light on the throes of war like the rest of this list (which is why it’s an HM, not an actual entry). But Captain America, in a lot of ways, encapsulates who we can be and what, ultimately, we hope to not have to be at the same time. It’s still one of Marvel’s greatest outings, and man if ol’ Cap isn’t a great hero to rally around.

Disney+ Amazon

20. Pan’s Labyrinth

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) Trailer #1 | Movieclips Classic Trailers

Watch on

Nothing like starting a list of war movies with a film that is technically only adjacently about war. Set against the Spanish Civil War, Guillermo del Toro’s strange look into the era is a fantastical triumph and a welcome respite from the obvious war genre.

Amazon Apple

19. Inglourious Basterds

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Inglourious Basterds Official Trailer #1 — Brad Pitt Movie (2009) HD

Watch on

Quentin Tarantino is a legend. The director’s revisionist look at World War II brings his pulpy style to «killin’ Nazis.» And like any Tarantino flick, it spares no opportunity for a bit of gore and bloodshed. Lt. Aldo Raine? A legend for-fucking-ever.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

18. Gallipoli

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Gallipoli is an Australian’s look into World War I, starring Mel Gibson. The film was lauded by critics, completely swept Australian film awards, and remains one of the greatest war epics of all time. Go Australia!

Amazon

17. Dunkirk

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

This film is a masterful look at the attack on Dunkirk from three different vantage points. Also, as a bonus, it features Harry Styles in his first major acting role, and your boy will make you proud.

Amazon

16. Black Hawn Down

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Ridley Scott’s entry into war movies is based on a book of the same name. The ensemble cast led by Josh Hartnett and Ewan McGregor follows the story of the U.S. military’s 1993 raid in Mogadishu.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

15. Full Metal Jacket

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The 1987 war film by Stanley Kubrick stars Matthew Modine, R. Lee Ermey, Vincent D’Onofrio ,and Adam Baldwin. Full Metal Jacket takes you right into the trenches of war and is seen as one of the best films set during the Vietnam War.

Amazon

14. Letters from Iwo Jima

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Letters From Iwo Jima (2006) Trailer — HD

Watch on

Clint Eastwood’s 2006 Japenese-language film is one of the most celebrated war movies in recent history. That happens when you combine the powers of Spielberg producing, Eastwood directing, and Yamashita’s screenplay. It tackles the complexities of good and evil on both sides of World War II to absolute perfection.

Amazon Apple

13. Paths of Glory

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Paths of Glory (1/11) Movie CLIP — A Stroll Through the Trenches (1957) HD

Watch on

Paths of Glory is actually a bit of an anti-war film. Directed by Stanley Kurbrick, it holds up as one of the most important entires into the genre and continues to be a guidepost for how to create a beautiful film about war.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

12. Hiroshima Mon Amour

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR — Trailer (Il Cinema Ritrovato al cinema)

Watch on

French director Alain Resnais may be most often associated with the free-wheeling films of the French New Wave movement, but perhaps his greatest gift to world cinema is Hiroshima mon amour. The movie explores a tragic and intimate love affair between a French actress and Japanese architect. Both of their lives were irrevocably changed by World War II and the devastation of the Hiroshima bomb in 1945. Even if you’re not a film buff, this one is worth a watch–it’s every bit as vital as any of the war films on this list.

Amazon Apple

11. 1917

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

I mean, just look at the trailer. This 2019 Best Picture nominee is more of a film about pacifism than it is about the glories of either side of WWI. Shot to look like one continuous take, after watching it, you’ll feel like you spent nearly 2 hours without breathing.

Amazon

10. Patton

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Patton (1/5) Movie CLIP — Americans Love a Winner (1970) HD

Watch on

This biographical film about General George S. Patton is a favorite among war movie buffs… deservedly so. It went on to win seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Director.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

9. Schindler’s List

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Schindler’s List (2/9) Movie CLIP — Commandant Amon Goeth (1993) HD

Watch on

There is perhaps no more grueling and heartbreaking cinematic portrayal of the Holocaust than Schindler’s List, a portrayal of World War II where a German businessman works to save more than a thousand Jewish people by employing them in his factories.

Amazon Apple

8. The Bridge on the River Kwai

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The Bridge on the Ricer Kwai helped set a precedent for the war film genre in 1957. It also was nominated for an insane amount of Oscars, winning seven.

Amazon Apple

7. Platoon

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Platoon (1986) — Barnes Crosses the Line Scene (3/10) | Movieclips

Watch on

Platoon stars Willem Dafoe and Charlie Sheen in one of the most raw and devastating portrayals of war in film history. Oliver Stone wrote the screenplay based on his own experience in Vietnam, and the effects are both moving and disturbing at the same time.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

6. Apocalypse Now

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Apocalypse Now (1979) Official Trailer — Martin Sheen, Robert Duvall Drama Movie HD

Watch on

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 classic is essentially an epic anti-war film starring the greats: Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, and Martin Sheen. Skewering the pointlessness of the Vietnam War, the film has only gained acclaim as perhaps the best war epic of all time.

HBO Hulu Apple

5. Ran

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Ran is a war movie like no other. The 1985 epic takes a bit from Shakespeare’s King Lear, turning three loyal sons on their father, Hidetora Ichimonji, who abdicates his throne.

Apple

4. Saving Private Ryan

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Saving Private Ryan dives into the complex ethics of war. When a mother loses three of her four sons in combat, a special mission is developed to go out to save the surviving Private Ryan (Matt Damon) in Normandy before he becomes the final fatality that breaks a family apart. But in doing so, the mission risks the lives of the seven men sent to save him.

Amazon Apple

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

3. The Hurt Locker

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The Hurt Locker (1/9) Movie CLIP — You Wanna Back Up? (2008) HD

Watch on

Kathryn Bigelow’s look at modern-day warfare is a fascinating glimpse into a revamped war genre. With The Hurt Locker, Bigelow became the first and only woman so far to win the Academy Award for Best Director.

Amazon Apple

2. The Thin Red Line

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The Thin Red Line Official Trailer #1 — Terrence Malick Movie (1998)

Watch on

Starring Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, Jim Caviezel, George Clooney, and a laundry list of other giant names, the Terrence Malick film is a contemporary look into World War II and often regarded as the greatest modern war epic.

Amazon Apple

Writer

Justin Kirkland is a Brooklyn-based writer who covers culture, food, and the South. Along with Esquire, his work has appeared in NYLON, Vulture, and USA Today.

War is a rough subject that’s very hard to fully grasp if you haven’t been there. With that being said, the world of cinema has managed to get the horrors and humor of war right a handful of times, according to the accounts of actual veterans who were actually present for the conflict. Is that all it takes to create one of the best war movies?

Realism is important, of course, but it may not mean a ton if a movie itself isn’t a must-watch drama that civilians and those curious are looking to years in the future to understand just how grizzly these conflicts can be. The following are a list of films that hit that mark of best war movies in terms of realism and quality, listed in chronological order.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Arguably the most famous war movie on the list, Francis Ford Coppola’s tale of a Vietnam soldier tasked with terminating a rogue officer «with extreme prejudice.» The story starts off pretty standardly, and slowly devolves into something much darker and different as the film goes on. This has led to some criticism from veterans, many of whom say the first third of the movie is a far more realistic depiction of war than the parts after. Still, the early stuff seems to be spot on and this is, of course, an enduring movie.

Part of this is due to Francis Ford Coppola’s vision, which was to adapt the famous 1899 novella Heart of Darkness into a story about Vietnam. Luckily, the film’s engaging story and iconic moments have made it a classic amongst war movie aficionados and certainly a contender for the best war movie of all time.

Das Boot (1981)

Das Boot was a German drama that was based on the novel of the same name and the efforts of a real German submarine, the U-96. The movie was created using a mock-up replica of the actual ship, in an effort to effectively capture the mixture of inaction and action German submariners went through during WWII.

Though the novel’s author criticized Das Boot for its glorification of war (the book was meant to be anti-war), American and German audiences responded well to the movie. That’s likely thanks in no small part to this best war movie’s painstaking recreation of the boat, which was also rented by Steven Spielberg during production for Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Platoon (1986)

There are several great films about the Vietnam War, although Platoon tends to stand out as one of the leaders of the pack in terms of realism. This «best war movie» is often mentioned by Vietnam veterans of one of the most accurate depictions of the war, thanks in no small part to its Vietnam veteran director, Oliver Stone.

Unlike other popular war movies like Apocalypse Now, Stone’s screenplay meshes his experience with the accounts of other Marines who were in the conflict. The result was a graphic and powerful performances by talented actors and a depiction of war that won’t soon be forgotten. It’s even hard to find a criticism on inaccuracies it shows, which speaks both to its realism and quality as one of the best war movies.

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

When one thinks of the best war movies, Saving Private Ryan may and definitely should be at the top of the list. The Omaha landing sequence is frequently referenced as one of the most accurate war scenes of WW2 in cinematic history which, quite frankly, is a terrifying thought. What’s more impressive is the scene did not get a storyboard, and Steven Spielberg opted instead to direct his camera toward more spontaneous moments.

There are a few less factual parts of the tale, but Steven Spielberg explained that he let realism fall by the wayside for a couple of scenes for dramatic effect, to better speak to the emotion of the story. Perhaps more so than any other entry on this list, Saving Private Ryan walks the line between fact and fiction the best.

Black Hawk Down (2002)

Black Hawk Down is Ridley Scott’s telling of The Battle of Mogadishu with an all-star cast that includes the likes of Ewan McGregor, Josh Hartnett, and Tom Hardy. The story follows three special forces units, all tasked with capturing Mohamed Farrah Aidid. Things go south, and result in an event that ended in the death of 1000 Somali and 19 American soldiers.

While Black Hawk Down is often lauded as one of the best war movies for its accurate combat depictions, it has found criticism for being a fairly one-sided account of the conflict. In reality American soldiers were aided by Malaysian and Pakistani forces, neither of which are represented in the movie. Additionally, Somali advocacy groups have noted the depiction of Somalis in the film is inaccurate, and it’s worth noting no Somalis were cast in the film.

We Were Soldiers (2002)

Mel Gibson’s We Were Soldiers is a more modern film that chronicles the Vietnam War, and specifically, the Battle of la Drang. It’s spot as one of the best war movies is backed by the numerous efforts made to maintain realism and recall the events of Hal Moore’s memoir We Were Soldiers Once… And Young.

For all the movie gets right, it does bend the truth in showing the final charge by American forces. There was no such event, and the North Vietnamese were not destroyed. It’s one of the big glaring differences, but for the most part, the rest are simply details that seem trimmed for the sake of shortening the story. Perhaps if a TV series was made, the full depiction of events could be brought to life.

Hacksaw Ridge (2016)

Speaking of atypical depictions of war, Hacksaw Ridge tells the mostly true account of Desmond Doss, who went through his service in WW2 without a weapon. Despite his lack of a firearm, Doss saved numerous lives in The Battle of Okinawa at the cost of severe injuries that inevitably affected the rest of his life.

Surprisingly, the factual inaccuracies of Hacksaw Ridge are not on the field of battle, but in the stories outside of Desmond Doss’ service. Doss’ wife didn’t become a nurse until after the war, and the family fight that encouraged him to never use a weapon was between his uncle and father, not his father and mother. Doss was never actually court martial-ed, but was threatened many times. It makes for a great story nonetheless, hence its place on the list.

There are plenty of great war movies and plenty of other realistic war movies out there, so if there are any that have been left off the list that deserve mention for an exceptional mix of quality and realism, drop it down in the comments below. We’re always looking to add to our binge-watching lists anyway.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Mick likes good television, but also reality television. He grew up on Star Wars, DC, Marvel, and pro wrestling and loves to discuss and dissect most of it. He’s been writing online for over a decade and never dreamed he’d be in the position he is today.

Most Popular

From swords-and-sandals skirmishes, to World War II men-on-a-mission movies, to futuristic tales of humanity battling antagonistic alien races, the history of cinema is full of war films. Some depict real-life battles, victories and defeats. Others tell fictionalised stories to humanise the vast scale of lost lives and sacrifices made on the frontlines, bringing the horrors of war and the disorientation of combat to life with impeccable cinematic craft and emotional storytelling.

Team Empire has come up with a list of the greatest war movies, presented in chronological order from the 12th Century to the 23rd Century – spanning the Crusades, the World Wars, Vietnam, the Iraq War, and beyond. There are documentaries, animations, films made nearly 100 years ago, ones that purposefully alter the course of history, ones that predict sci-fi futures, and modern classics that shine a contemporary light on events that should never be forgotten.

1 of 24

Era: The CrusadesAfter reigniting the swords-and-sandals genre in Gladiator, legendary director Ridley Scott delivered a full-on historical war epic set during the Crusades. Orlando Bloom plays Balian of Ibelin, a French blacksmith pulled into the religious conflict, becoming a leader and fighting against the forces of the Sultan Saladin. Avoid the theatrical edition – the completely-overhauled and much more satisfying Director’s Cut significantly deepens the characters and rounds out the story. For the ultimate experience, watch the Roadshow Cut – which features the Director’s Cut of the film, plus opening overture and mid-movie intermission.Buy here on Amazon

2 of 24

Era: The Napoleonic WarsSergei Bondarchuk’s spared-no-expense depiction of the Battle Of Waterloo is filmmaking at mind-boggling scale. Before the time of CGI, the filmmaker wrangled 17,000 extras drafted in from the Soviet Army to depict the bloody Belgian battle, with Rod Steiger as Napoleon, Christoper Plummer as the Duke of Wellington, and Orson Welles as France’s King Louis XVIII. Its ambition ultimately proved too big – the film couldn’t hope to recoup its production costs, though it did go on to become a major inspiration for the way Peter Jackson approached the battles in his Lord Of The Rings adaptations.Buy now on Amazon

3 of 24

Era: World War IThis early Stanley Kubrick film explores the illogic of war itself, as examined through the pointlessness of the First World War at large. The action largely takes place around the attempted siege of a German ‘anthill’ position – a mission that results in the French soldiers being hit by Allied artillery, while survivors are court martially with charges of ‘cowardice’ in the aftermath. An anti-war movie that’s just as cinematic as you’d expect from the master director.Buy now on Amazon

4 of 24

Era: World War IPresented as one extended, fluid take, Sam Mendes’ soldier-centric tale is no mere technical exercise. George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman are Lance Corporals Schofield and Blake, dispatched on a race-against-time mission across No Man’s Land in order to stop an ill-conceived battle that will result in thousands of British soldiers dead. For an extra personal kick, Blake’s older brother is among the troops set to go over the top. Mendes crafts astonishing tension and incredible immersion with a non-stop tour through the hell of trenches, battlefields, and war-torn towns, with jaw-dropping cinematography from the legendary Roger Deakins.Buy now on Amazon

5 of 24

Era: World War IIn a similar vein to Kubrick’s Paths Of Glory, Lewis Milestone’s near-century-old adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel is about the futility of war and the innocent young soldiers who lost their lives en masse to the conflict. It’s not only one of the definitive and formative war films, but also one of the most notable early ‘talkie’ features as the medium entered the era of sound.Buy now on Amazon

6 of 24

Era: World War IAfter depicting war-torn fantasy landscapes in The Lord Of The Rings, Peter Jackson turned his attention to real-life footage from the First World War. With his team, he created a system for smoothing out the jerky framerate of very early film reels, and used it to turn traditionally ‘old’ looking footage from the Imperial War Museum into something more recognisably modern, before colouring it and adding dialogue with the help of lip-readers. The result is a deeply humanising look at the frontlines of the war, bolstered with interviews from soldiers who survived the conflict.Buy now on Amazon

7 of 24