1. Mountain Everest is the highest mountain in the world.

2. Sherlock Holmes was the best detective in London.

3. Go and pick an apple from the nearest tree.

4. Tokyo is the biggest city in the world.

5. Rebecca is nicer than Jane.

6. Mrs Brown is taller than Mrs Taylor.

7. I think English is easier than French. 8. John is the worst skier in the school.

9. This is the funniest joke I know.

10. Cindy is the cleverest girl in the class.

11. My football socks are dirtier than yours.

12. I find French more interesting than history.

13. The new hotel is the most modern building in our town.

14. Tony is the most intelligent boy in our class.

15. Good health is better than money.

16. This is a wonderful place for a holiday.

17. I find French more difficult than English.

18. Karen is the prettiest girl in the class.

19. He is the ugliest man in the world.

20. The giraffe is the tallest animal in the world.

Употребите прилагательное, данное в скобках, в нужной форме (сравнительной или превосходной степени); переведите на русский язык:

1. Mount Everest is the (high) mountain in the world. 2. Sherlock Holmes was the (good) detective in London. 3. Greece is (near) to the equator than Denmark. 4. Tokyo is the (big) city in the world. 5. Books by Somerset Maugham are the (interesting) I have ever read.

Светило науки — 704 ответа — 3846 раз оказано помощи

1. Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world. (Эверест — самая большая гора в мире.) 2. Sherlock Holmes was the best detective in London. (Шэрлок Холмс был самым лучшим детективом в Лондоне.) 3. Greece is nearer to the equator than Denmark. (Греция ближе к экватору чем Денмарк.) 4. Tokyo is the biggest city in the world. (Токио — самый большой город в мире.) 5. Books by Somerset Maugham are the most interesting I have ever read. (Книги Сомерсета Мэгхама самые интересные, которые я когда-либо читал/читала.

67 месяцев назад

Раскройте скобки и поставьте прилагательные в нужной форме. 1. Mountain Everest is (high) mountain in the world. 2. Sherlock

Holmes was (good) detective in London. 3. Go and pick an apple from (near) tree. 4. Tokyo is (big) city in the world. 5: Rebecca is (nice) than Jane. 6. Mrs Brown is (tall) than Mrs Taylor. 7.I think English is (easy) than French. 8. John is (bad) skier in the school. 9. This is (funny) joke I know. 10. Cindy is (clever) girl in the class. 11. My football socks are (dirty) than yours. 12. I find French (interesting) than history. 13. The new hotel is (modern) building in our town. 14. Tony is (intelligent) boy in our class. 15. Good health is (good) than money. 16. This is (wonderful) place for a holiday. 17. I find French (difficult) than English. 18. Karen is (pretty) girl in the class. 19. He is (ugly) man in the world. 20. The giraffe is (tall) animal in the world.

Ответы

Будь первым, кто ответит на вопрос

| Mount Everest | |

|---|---|

Aerial photo from the south, with Mount Everest rising above the ridge connecting Nuptse and Lhotse |

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 8,848.86 m (29,031.7 ft) Ranked 1st |

| Prominence | 8,848.86 m (29,031.7 ft) Ranked 1st (Special definition for Everest) |

| Parent peak | Unknown |

| Isolation | n/a |

| Listing |

|

| Coordinates | 27°59′17″N 86°55′31″E / 27.98806°N 86.92528°ECoordinates: 27°59′17″N 86°55′31″E / 27.98806°N 86.92528°E[note 2] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | George Everest |

| Native name |

|

| English translation | Holy Mother |

| Geography | |

|

Mount Everest Location on the border between Province No. 1, Nepal and Tibet Autonomous Region, China Mount Everest Mount Everest (Koshi Province) Mount Everest Mount Everest (China) Mount Everest Mount Everest (Tibet) Mount Everest Mount Everest (Asia) |

|

| Location | Solukhumbu District, Province No. 1, Nepal;[1] Tingri County, Xigazê, Tibet Autonomous Region, China[note 3] |

| Countries | China and Nepal |

| Parent range | Mahalangur Himal, Himalayas |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 29 May 1953 Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay |

| Normal route | Southeast ridge (Nepal) |

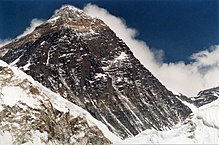

North Face as seen from the path to North Base Camp

Mount Everest (Nepali: सगरमाथा, romanized: Sagarmāthā; Tibetan: Chomolungma ཇོ་མོ་གླང་མ; Chinese: 珠穆朗玛峰; pinyin: Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng) is Earth’s highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point.[2] Its elevation (snow height) of 8,848.86 m (29,031 ft 8+1⁄2 in) was most recently established in 2020 by the Chinese and Nepali authorities.[3]

Mount Everest attracts many climbers, including highly experienced mountaineers. There are two main climbing routes, one approaching the summit from the southeast in Nepal (known as the «standard route») and the other from the north in Tibet. While not posing substantial technical climbing challenges on the standard route, Everest presents dangers such as altitude sickness, weather, and wind, as well as hazards from avalanches and the Khumbu Icefall. As of 2019, over 300 people have died on Everest,[4] many of whose bodies remain on the mountain.[5]

The first recorded efforts to reach Everest’s summit were made by British mountaineers. As Nepal did not allow foreigners to enter the country at the time, the British made several attempts on the north ridge route from the Tibetan side. After the first reconnaissance expedition by the British in 1921 reached 7,000 m (22,970 ft) on the North Col, the 1922 expedition pushed the north ridge route up to 8,320 m (27,300 ft), marking the first time a human had climbed above 8,000 m (26,247 ft). The 1924 expedition resulted in one of the greatest mysteries on Everest to this day: George Mallory and Andrew Irvine made a final summit attempt on 8 June but never returned, sparking debate as to whether they were the first to reach the top. Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary made the first documented ascent of Everest in 1953, using the southeast ridge route. Norgay had reached 8,595 m (28,199 ft) the previous year as a member of the 1952 Swiss expedition. The Chinese mountaineering team of Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo, and Qu Yinhua made the first reported ascent of the peak from the north ridge on 25 May 1960.[6]

Name

The name «Mount Everest» was first proposed in this 1856 speech, later published in 1857, in which the mountain was first confirmed as the world’s highest.

The Tibetan name for Everest is Qomolangma (ཇོ་མོ་གླང་མ, lit. «Holy Mother»). The name was first recorded with a Chinese transcription on the 1721 Kangxi Atlas during the reign of Emperor Kangxi of Qing China, and then appeared as Tchoumour Lancma on a 1733 map published in Paris by the French geographer D’Anville based on the former map.[7] It is also popularly romanised as Chomolungma and (in Wylie) as Jo-mo-glang-ma.[12] The official Chinese transcription is 珠穆朗玛峰 (t 珠穆朗瑪峰), whose pinyin form is Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng. While other Chinese names exist, including Shèngmǔ Fēng (t 聖母峰, s 圣母峰, lit. «Holy Mother Peak»), these names largely phased out from May 1952 as the Ministry of Internal Affairs of China issued a decree to adopt 珠穆朗玛峰 as the sole name[13] (romanised: Mount Qomolangma[14]). Documented local names include «Deodungha» («Holy Mountain»), but it is unclear whether it is commonly used.[15]

In 1849, the British survey wanted to preserve local names if possible (e.g., Kangchenjunga and Dhaulagiri), and Andrew Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India argued that he could not find any commonly used local name, as his search for a local name was hampered by Nepal’s and Tibet’s exclusion of foreigners. Waugh argued that because there were many local names, it would be difficult to favour one name over all others; he decided that Peak XV should be named after British surveyor Sir George Everest, his predecessor as Surveyor General of India.[16][17][18] Everest himself opposed the name suggested by Waugh and told the Royal Geographical Society in 1857 that «Everest» could not be written in Hindi nor pronounced by «the native of India». Waugh’s proposed name prevailed despite the objections, and in 1865, the Royal Geographical Society officially adopted Mount Everest as the name for the highest mountain in the world.[16][19] The modern pronunciation of Everest ()[20] is different from Sir George’s pronunciation of his surname ( EEV-rist).[21][verification needed] In the late 19th century, many European cartographers incorrectly believed that a native name for the mountain was Gaurishankar, a mountain between Kathmandu and Everest.[22]

In the early 1960s, the Nepali government coined the Nepali name Sagarmāthā (IAST transcription) or Sagar-Matha[23] (सगर-माथा, [sʌɡʌrmatʰa], lit. «goddess of the sky»[24]),[25] which means «the Head in the Great Blue Sky», being derived from सगर (sagar), meaning «sky», and माथा (māthā), meaning «head».

Other names

1890 graphic with the Himalayas, including Gaurisankar (Mount Everest) in the distance

- Peak XV (British Empire’s Survey)[16][17][18]

- Old Darjeeling name: «Deodungha»[26]

- «Gauri Shankar» or «Gaurisankar»; in modern times the name is used for a different peak about 30 miles (48 kilometres) away, but it was used occasionally until about 1900.[27]

Surveys

19th-century surveys

In 1802, the British began the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India to fix the locations, heights, and names of the world’s highest mountains. Starting in southern India, the survey teams moved northward using giant theodolites, each weighing 500 kg (1,100 lb) and requiring 12 men to carry, to measure heights as accurately as possible. They reached the Himalayan foothills by the 1830s, but Nepal was unwilling to allow the British to enter the country due to suspicions of their intentions. Several requests by the surveyors to enter Nepal were denied.[16]

The British were forced to continue their observations from Terai, a region south of Nepal which is parallel to the Himalayas. Conditions in Terai were difficult because of torrential rains and malaria. Three survey officers died from malaria while two others had to retire because of failing health.[16]

Nonetheless, in 1847, the British continued the survey and began detailed observations of the Himalayan peaks from observation stations up to 240 km (150 mi) distant. Weather restricted work to the last three months of the year. In November 1847, Andrew Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India, made several observations from the Sawajpore station at the east end of the Himalayas. Kangchenjunga was then considered the highest peak in the world, and with interest, he noted a peak beyond it, about 230 km (140 mi) away. John Armstrong, one of Waugh’s subordinates, also saw the peak from a site farther west and called it peak «b». Waugh would later write that the observations indicated that peak «b» was higher than Kangchenjunga, but given the great distance of the observations, closer observations were required for verification. The following year, Waugh sent a survey official back to Terai to make closer observations of peak «b», but clouds thwarted his attempts.[16]

In 1849, Waugh dispatched James Nicolson to the area, who made two observations from Jirol, 190 km (120 mi) away. Nicolson then took the largest theodolite and headed east, obtaining over 30 observations from five different locations, with the closest being 174 km (108 mi) from the peak.[16]

Nicolson retreated to Patna on the Ganges to perform the necessary calculations based on his observations. His raw data gave an average height of 9,200 m (30,200 ft) for peak «b», but this did not consider light refraction, which distorts heights. However, the number clearly indicated that peak «b» was higher than Kangchenjunga. Nicolson contracted malaria and was forced to return home without finishing his calculations. Michael Hennessy, one of Waugh’s assistants, had begun designating peaks based on Roman numerals, with Kangchenjunga named Peak IX. Peak «b» now became known as Peak XV.[16]

In 1852, stationed at the survey headquarters in Dehradun, Radhanath Sikdar, an Indian mathematician and surveyor from Bengal was the first to identify Everest as the world’s highest peak, using trigonometric calculations based on Nicolson’s measurements.[28] An official announcement that Peak XV was the highest was delayed for several years as the calculations were repeatedly verified. Waugh began work on Nicolson’s data in 1854, and along with his staff spent almost two years working on the numbers, having to deal with the problems of light refraction, barometric pressure, and temperature over the vast distances of the observations. Finally, in March 1856 he announced his findings in a letter to his deputy in Calcutta. Kangchenjunga was declared to be 8,582 m (28,156 ft), while Peak XV was given the height of 8,840 m (29,002 ft). Waugh concluded that Peak XV was «most probably the highest in the world».[16] Peak XV (measured in feet) was calculated to be exactly 29,000 ft (8,839.2 m) high, but was publicly declared to be 29,002 ft (8,839.8 m) in order to avoid the impression that an exact height of 29,000 feet (8,839.2 m) was nothing more than a rounded estimate.[29] Waugh is sometimes playfully credited with being «the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest».[30]

20th-century surveys

Published by the Survey of Nepal, this is Map 50 of the 57 map set at 1:50,000 scale «attached to the main text on the First Joint Inspection Survey, 1979–80, Nepal-China border.» At the top centre, a boundary line, identified as separating «China» and «Nepal», passes through the summit contour. The boundary here and for much of the China–Nepal border follows the main Himalayan watershed divide.

Kangshung Face (the east face) as seen from orbit

In 1856, Andrew Waugh announced Everest (then known as Peak XV) as 8,840 m (29,002 ft) high, after several years of calculations based on observations made by the Great Trigonometrical Survey.[31]

In 1955, the elevation of 8,848 m (29,029 ft) was first determined by an Indian survey, made closer to the mountain, also using theodolites.[citation needed] In 1975 it was subsequently reaffirmed by a Chinese measurement of 8,848.13 m (29,029.30 ft).[32] In both cases the snow cap, not the rock head, was measured.

The 8,848 m (29,029 ft) height given was officially recognised by Nepal and China.[33] Nepal planned a new survey in 2019 to determine if the April 2015 Nepal earthquake affected the height of the mountain.[34]

In May 1999, an American Everest expedition directed by Bradford Washburn anchored a GPS unit into the highest bedrock. A rock head elevation of 8,850 m (29,035 ft), and a snow/ice elevation 1 m (3 ft) higher, were obtained via this device.[35] Although as of 2001, it has not been officially recognised by Nepal,[36] this figure is widely quoted. Geoid uncertainty casts doubt upon the accuracy claimed by both the 1999 and 2005 (see § 21st-century surveys) surveys.[37]

In 1955, a detailed photogrammetric map (at a scale of 1:50,000) of the Khumbu region, including the south side of Mount Everest, was made by Erwin Schneider as part of the 1955 International Himalayan Expedition, which also attempted Lhotse.

In the late 1980s, an even more detailed topographic map of the Everest area was made under the direction of Bradford Washburn, using extensive aerial photography.[38]

21st-century surveys

On 9 October 2005, after several months of measurement and calculation, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping announced the height of Everest as 8,844.43 m (29,017.16 ft) with accuracy of ±0.21 m (8.3 in), claiming it was the most accurate and precise measurement to date.[39] This height is based on the highest point of rock and not the snow and ice covering it. The Chinese team measured a snow-ice depth of 3.5 m (11 ft),[32] which is in agreement with a net elevation of 8,848 m (29,029 ft). An argument arose between China and Nepal as to whether the official height should be the rock height (8,844 m, China) or the snow height (8,848 m, Nepal). In 2010, both sides agreed that the height of Everest is 8,848 m, and Nepal recognises China’s claim that the rock height of Everest is 8,844 m.[40] On 8 December 2020, it was jointly announced by the two countries that the new official height is 8,848.86 metres (29,031.7 ft).[41][42]

It is thought that the plate tectonics of the area are adding to the height and moving the summit northeastwards. Two accounts suggest the rates of change are 4 mm (0.16 in) per year vertically and 3 to 6 mm (0.12 to 0.24 in) per year horizontally,[35][43] but another account mentions more lateral movement (27 mm or 1.1 in),[44] and even shrinkage has been suggested.[45]

Comparisons

The summit of Everest is the point at which Earth’s surface reaches the greatest distance above sea level. Several other mountains are sometimes claimed to be the «tallest mountains on Earth». Mauna Kea in Hawaii is tallest when measured from its base;[note 4] it rises over 10,200 m (33,464.6 ft) when measured from its base on the mid-ocean floor, but only attains 4,205 m (13,796 ft) above sea level.

By the same measure of base to summit, Denali, in Alaska, also known as Mount McKinley, is taller than Everest as well.[note 4] Despite its height above sea level of only 6,190 m (20,308 ft), Denali sits atop a sloping plain with elevations from 300 to 900 m (980 to 2,950 ft), yielding a height above base in the range of 5,300 to 5,900 m (17,400 to 19,400 ft); a commonly quoted figure is 5,600 m (18,400 ft).[46][47] By comparison, reasonable base elevations for Everest range from 4,200 m (13,800 ft) on the south side to 5,200 m (17,100 ft) on the Tibetan Plateau, yielding a height above base in the range of 3,650 to 4,650 m (11,980 to 15,260 ft).[38]

The summit of Chimborazo in Ecuador is 2,168 m (7,113 ft) farther from Earth’s centre (6,384.4 km, 3,967.1 mi) than that of Everest (6,382.3 km, 3,965.8 mi), because the Earth bulges at the equator.[48] This is despite Chimborazo having a peak 6,268 m (20,564.3 ft) above sea level versus Mount Everest’s 8,848 m (29,028.9 ft).

Geology

Mount Everest with snow melted, showing upper geologic layers in bands.

Geologists have subdivided the rocks comprising Mount Everest into three units called formations.[49][50] Each formation is separated from the other by low-angle faults, called detachments, along which they have been thrust southward over each other. From the summit of Mount Everest to its base these rock units are the Qomolangma Formation, the North Col Formation, and the Rongbuk Formation.

The Qomolangma Formation, also known as the Jolmo Lungama Formation,[51] runs from the summit to the top of the Yellow Band, about 8,600 m (28,200 ft) above sea level. It consists of greyish to dark grey or white, parallel laminated and bedded, Ordovician limestone interlayered with subordinate beds of recrystallised dolomite with argillaceous laminae and siltstone. Gansser first reported finding microscopic fragments of crinoids in this limestone.[52][53] Later petrographic analysis of samples of the limestone from near the summit revealed them to be composed of carbonate pellets and finely fragmented remains of trilobites, crinoids, and ostracods. Other samples were so badly sheared and recrystallised that their original constituents could not be determined. A thick, white-weathering thrombolite bed that is 60 m (200 ft) thick comprises the foot of the «Third Step», and base of the summit pyramid of Everest. This bed, which crops out starting about 70 m (230 ft) below the summit of Mount Everest, consists of sediments trapped, bound, and cemented by the biofilms of micro-organisms, especially cyanobacteria, in shallow marine waters. The Qomolangma Formation is broken up by several high-angle faults that terminate at the low angle normal fault, the Qomolangma Detachment. This detachment separates it from the underlying Yellow Band. The lower five metres of the Qomolangma Formation overlying this detachment are very highly deformed.[49][50][54]

The bulk of Mount Everest, between 7,000 and 8,600 m (23,000 and 28,200 ft), consists of the North Col Formation, of which the Yellow Band forms the upper part between 8,200 to 8,600 m (26,900 to 28,200 ft). The Yellow Band consists of intercalated beds of Middle Cambrian diopside-epidote-bearing marble, which weathers a distinctive yellowish brown, and muscovite-biotite phyllite and semischist. Petrographic analysis of marble collected from about 8,300 m (27,200 ft) found it to consist as much as five per cent of the ghosts of recrystallised crinoid ossicles. The upper five metres of the Yellow Band lying adjacent to the Qomolangma Detachment is badly deformed. A 5–40 cm (2.0–15.7 in) thick fault breccia separates it from the overlying Qomolangma Formation.[49][50][54]

The remainder of the North Col Formation, exposed between 7,000 to 8,200 m (23,000 to 26,900 ft) on Mount Everest, consists of interlayered and deformed schist, phyllite, and minor marble. Between 7,600 and 8,200 m (24,900 and 26,900 ft), the North Col Formation consists chiefly of biotite-quartz phyllite and chlorite-biotite phyllite intercalated with minor amounts of biotite-sericite-quartz schist. Between 7,000 and 7,600 m (23,000 and 24,900 ft), the lower part of the North Col Formation consists of biotite-quartz schist intercalated with epidote-quartz schist, biotite-calcite-quartz schist, and thin layers of quartzose marble. These metamorphic rocks appear to be the result of the metamorphism of Middle to Early Cambrian deep sea flysch composed of interbedded, mudstone, shale, clayey sandstone, calcareous sandstone, graywacke, and sandy limestone. The base of the North Col Formation is a regional low-angle normal fault called the «Lhotse detachment».[49][50][54]

Below 7,000 m (23,000 ft), the Rongbuk Formation underlies the North Col Formation and forms the base of Mount Everest. It consists of sillimanite-K-feldspar grade schist and gneiss intruded by numerous sills and dikes of leucogranite ranging in thickness from 1 cm to 1,500 m (0.4 in to 4,900 ft).[50][55] These leucogranites are part of a belt of Late Oligocene–Miocene intrusive rocks known as the Higher Himalayan leucogranite. They formed as the result of partial melting of Paleoproterozoic to Ordovician high-grade metasedimentary rocks of the Higher Himalayan Sequence about 20 to 24 million years ago during the subduction of the Indian Plate.[56]

Mount Everest consists of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks that have been faulted southward over continental crust composed of Archean granulites of the Indian Plate during the Cenozoic collision of India with Asia.[57][58][59] Current interpretations argue that the Qomolangma and North Col formations consist of marine sediments that accumulated within the continental shelf of the northern passive continental margin of India before it collided with Asia. The Cenozoic collision of India with Asia subsequently deformed and metamorphosed these strata as it thrust them southward and upward.[60][61] The Rongbuk Formation consists of a sequence of high-grade metamorphic and granitic rocks that were derived from the alteration of high-grade metasedimentary rocks. During the collision of India with Asia, these rocks were thrust downward and to the north as they were overridden by other strata; heated, metamorphosed, and partially melted at depths of over 15 to 20 kilometres (9.3 to 12.4 mi) below sea level; and then forced upward to surface by thrusting towards the south between two major detachments.[62] The Himalayas are rising by about 5 mm per year.

IUGS geological heritage site

In respect of the recognition of the ‘highest rocks on the planet’ as fossiliferous, marine limestone, the ‘Ordovician Rocks of Mount Everest’ were included by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in its assemblage of 100 ‘geological heritage sites’ around the world in a listing published in October 2022. The organisation defines an ‘IUGS Geological Heritage Site’ as ‘a key place with geological elements and/or processes of international scientific relevance, used as a reference, and/or with a substantial contribution to the development of geological sciences through history.’[63]

Flora and fauna

A yak at around 4,790 m (15,720 ft)

There is very little native flora or fauna on Everest. A moss grows at 6,480 metres (21,260 ft) on Mount Everest.[64] It may be the highest altitude plant species.[64] An alpine cushion plant called Arenaria is known to grow below 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) in the region.[65] According to the study based on satellite data from 1993 to 2018, vegetation is expanding in the Everest region. Researchers have found plants in areas that were previously deemed bare.[66]

Euophrys omnisuperstes, a minute black jumping spider, has been found at elevations as high as 6,700 metres (22,000 ft), possibly making it the highest confirmed non-microscopic permanent resident on Earth. In the base camp of Everest the jumping spider Euophrys everestensis occurs.[67] It lurks in crevices and may feed on frozen insects that have been blown there by the wind. There is a high likelihood of microscopic life at even higher altitudes.[68]

Birds, such as the bar-headed goose, have been seen flying at the higher altitudes of the mountain, while others, such as the chough, have been spotted as high as the South Col at 7,920 metres (25,980 ft).[69] Yellow-billed choughs have been seen as high as 7,900 metres (26,000 ft) and bar-headed geese migrate over the Himalayas.[70] In 1953, George Lowe (part of the expedition of Tenzing and Hillary) said that he saw bar-headed geese flying over Everest’s summit.[71]

Yaks are often used to haul gear for Mount Everest climbs. They can haul 100 kg (220 pounds), have thick fur and large lungs.[65] Other animals in the region include the Himalayan tahr which is sometimes eaten by the snow leopard.[72] The Himalayan black bear can be found up to about 4,300 metres (14,000 ft) and the red panda is also present in the region.[73] One expedition found a surprising range of species in the region including a pika and ten new species of ants.[74]

Climate

Mount Everest has an ice cap climate (Köppen EF) with all months averaging well below freezing.[note 5]

| Climate data for Mount Everest | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −36 (−33) |

−35 (−31) |

−32 (−26) |

−31 (−24) |

−25 (−13) |

−20 (−4) |

−18 (0) |

−18 (0) |

−21 (−6) |

−27 (−17) |

−30 (−22) |

−34 (−29) |

−36 (−33) |

| Source: [75] |

Climate change

The base camp for Everest expeditions based out of Nepal is located by Khumbu Glacier, which is rapidly thinning and destabilizing due to climate change, making it unsafe for climbers. As recommended by the committee formed by Nepal’s government to facilitate and monitor mountaineering in the Everest region, Taranath Adhikari—the director general of Nepal’s tourism department—said they have plans to move the base camp to a lower altitude. This would mean a longer distance for climbers between the base camp and Camp 1. However, the present base camp is still useful and could still serve its purpose for three to four years. The move may happen by 2024, per officials.[76]

Meteorology

| Atmospheric pressure comparison | Pressure | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kilopascal | psi | ||

| Olympus Mons summit | 0.03 | 0.0044 | – |

| Mars average | 0.6 | 0.087 | – |

| Hellas Planitia bottom | 1.16 | 0.168 | – |

| Armstrong limit | 6.25 | 0.906 | – |

| Mount Everest summit | 33.7 | 4.89 | [77] |

| Earth sea level | 101.3 | 14.69 | – |

| Dead Sea level | 106.7 | 15.48 | [78] |

| Surface of Venus | 9,200 | 1,330 | [79] |

In 2008, a new weather station at about 8,000 m (26,000 ft) elevation went online.[80] The station’s first data in May 2008 were air temperature −17 °C (1 °F), relative humidity 41.3 per cent, atmospheric pressure 382.1 hPa (38.21 kPa), wind direction 262.8°, wind speed 12.8 m/s (28.6 mph, 46.1 km/h), global solar radiation 711.9 watts/m2, solar UVA radiation 30.4 W/m2.[80] The project was orchestrated by Stations at High Altitude for Research on the Environment (SHARE), which also placed the Mount Everest webcam in 2011.[80][81] The solar-powered weather station is on the South Col.[82]

Mount Everest extends into the upper troposphere and penetrates the stratosphere.[83] The air pressure at the summit is generally about one-third what it is at sea level. The altitude can expose the summit to the fast and freezing winds of the jet stream.[84] Winds commonly attain 160 km/h (100 mph);[85] in February 2004, a wind speed of 280 km/h (175 mph) was recorded at the summit.

These winds can hamper or endanger climbers, by blowing them into chasms[85] or (by Bernoulli’s principle) by lowering the air pressure further, reducing available oxygen by up to 14 per cent.[84][86] To avoid the harshest winds, climbers typically aim for a 7- to 10-day window in the spring and fall when the Asian monsoon season is starting up or ending.

Expeditions

Reunion of the 1953 British team

Because Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world, it has attracted considerable attention and climbing attempts. Whether the mountain was climbed in ancient times is unknown. It may have been climbed in 1924, although this has never been confirmed, as neither of the men making the attempt returned. Several climbing routes have been established over several decades of climbing expeditions to the mountain.[87][88][better source needed]

Overview

Everest’s first known summiting occurred by 1953, and interest by climbers increased.[89] Despite the effort and attention poured into expeditions, only about 200 people had summitted by 1987.[89] Everest remained a difficult climb for decades, even for serious attempts by professional climbers and large national expeditions, which were the norm until the commercial era began in the 1990s.[90]

By March 2012, Everest had been climbed 5,656 times with 223 deaths.[91] Although lower mountains have longer or steeper climbs, Everest is so high the jet stream can hit it. Climbers can be faced with winds beyond 320 km/h (200 mph) when the weather shifts.[92] At certain times of the year the jet stream shifts north, providing periods of relative calm at the mountain.[93] Other dangers include blizzards and avalanches.[93]

By 2013, The Himalayan Database recorded 6,871 summits by 4,042 different people.[94]

Early attempts

In 1885, Clinton Thomas Dent, president of the Alpine Club, suggested that climbing Mount Everest was possible in his book Above the Snow Line.[95]

The northern approach to the mountain was discovered by George Mallory and Guy Bullock on the initial 1921 British Reconnaissance Expedition. It was an exploratory expedition not equipped for a serious attempt to climb the mountain. With Mallory leading (and thus becoming the first European to set foot on Everest’s flanks) they climbed the North Col to an altitude of 7,005 metres (22,982 ft). From there, Mallory espied a route to the top, but the party was unprepared for the great task of climbing any further and descended.

The British returned for a 1922 expedition. George Finch climbed using oxygen for the first time. He ascended at a remarkable speed—290 metres (951 ft) per hour, and reached an altitude of 8,320 m (27,300 ft), the first time a human reported to climb higher than 8,000 m. Mallory and Col. Felix Norton made a second unsuccessful attempt.

The next expedition was in 1924. The initial attempt by Mallory and Geoffrey Bruce was aborted when weather conditions prevented the establishment of Camp VI. The next attempt was that of Norton and Somervell, who climbed without oxygen and in perfect weather, traversing the North Face into the Great Couloir. Norton managed to reach 8,550 m (28,050 ft), though he ascended only 30 m (98 ft) or so in the last hour. Mallory rustled up oxygen equipment for a last-ditch effort. He chose young Andrew Irvine as his partner.[96]

On 8 June 1924, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine made an attempt on the summit via the North Col-North Ridge-Northeast Ridge route from which they never returned. On 1 May 1999, the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition found Mallory’s body on the North Face in a snow basin below and to the west of the traditional site of Camp VI. Controversy has raged in the mountaineering community whether one or both of them reached the summit 29 years before the confirmed ascent and safe descent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953.

In 1933, Lady Houston, a British millionairess, funded the Houston Everest Flight of 1933, which saw a formation of two aeroplanes led by the Marquess of Clydesdale fly over the Everest summit.[97][98][99][100]

Early expeditions—such as Charles Bruce’s in the 1920s and Hugh Ruttledge’s two unsuccessful attempts in 1933 and 1936—tried to ascend the mountain from Tibet, via the North Face. Access was closed from the north to Western expeditions in 1950 after China took control of Tibet. In 1950, Bill Tilman and a small party which included Charles Houston, Oscar Houston, and Betsy Cowles undertook an exploratory expedition to Everest through Nepal along the route which has now become the standard approach to Everest from the south.[101]

The 1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition, led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant, was granted permission to attempt a climb from Nepal. It established a route through the Khumbu icefall and ascended to the South Col at an elevation of 7,986 m (26,201 ft). Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay were able to reach an elevation of about 8,595 m (28,199 ft) on the southeast ridge, setting a new climbing altitude record. Tenzing’s experience was useful when he was hired to be part of the British expedition in 1953.[102] The Swiss decided to make another post-monsoon attempt in the autumn; they made it to the South Col but were driven back by winter winds and severe cold.[103][104]

First successful ascent by Tenzing and Hillary, 1953

In 1953, a ninth British expedition, led by John Hunt, returned to Nepal. Hunt selected two climbing pairs to attempt to reach the summit. The first pair, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, came within 100 m (330 ft) of the summit on 26 May 1953, but turned back after running into oxygen problems. As planned, their work in route finding and breaking trail and their oxygen caches were of great aid to the following pair. Two days later, the expedition made its second assault on the summit with the second climbing pair: the New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, a Nepali Sherpa climber. They reached the summit at 11:30 local time on 29 May 1953 via the South Col route. At the time, both acknowledged it as a team effort by the whole expedition, but Tenzing revealed a few years later that Hillary had put his foot on the summit first.[105] They paused at the summit to take photographs and buried a few sweets and a small cross in the snow before descending.[citation needed]

News of the expedition’s success reached London on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, 2 June. A few days later, the Queen gave orders that Hunt (a Briton) and Hillary (a New Zealander) were to be knighted in the Order of the British Empire for the ascent.[106] Tenzing, a Nepali Sherpa who was a citizen of India, was granted the George Medal by the UK. Hunt was ultimately made a life peer in Britain, while Hillary became a founding member of the Order of New Zealand.[107] Hillary and Tenzing have also been recognised in Nepal. In 2009, statues were raised in their honour, and in 2014, Hillary Peak and Tenzing Peak were named for them.[108][109]

1950s–1960s

On 23 May 1956, Ernst Schmied and Juerg Marmet ascended.[110] This was followed by Dölf Reist and Hans-Rudolf von Gunten on 24 May 1957.[110] Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo and Qu Yinhua of China made the first reported ascent of the peak from the North Ridge on 25 May 1960.[6] The first American to climb Everest, Jim Whittaker, joined by Nawang Gombu, reached the summit on 1 May 1963.[111][112]

1970s

In 1970, Japanese mountaineers conducted a major expedition. The centrepiece was a large «siege»-style expedition led by Saburo Matsukata, working on finding a new route up the southwest face.[113] Another element of the expedition was an attempt to ski Mount Everest.[90] Despite a staff of over one hundred people and a decade of planning work, the expedition suffered eight deaths and failed to summit via the planned routes.[90] However, Japanese expeditions did enjoy some successes. For example, Yuichiro Miura became the first man to ski down Everest from the South Col – he descended nearly 1,300 vertical metres (4,200 ft) from the South Col before falling with extreme injuries. Another success was an expedition that put four on the summit via the South Col route.[90][114][115] Miura’s exploits became the subject of film, and he went on to become the oldest person to summit Mount Everest in 2003 at age 70 and again in 2013 at the age of 80.[116]

In 1975, Junko Tabei, a Japanese woman, became the first woman to summit Mount Everest.[90]

The 1975 British Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition led and organised by Chris Bonington made the first ascent of the south west face of Everest from the western cwm.

The 1976 British and Nepalese Army Expedition to Everest led by Tony Streather put Bronco Lane and Brummy Stokes on the summit by the normal route.

In 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler made the first ascent of Everest without supplemental oxygen.

1979/1980: Winter Himalaism

The Polish climber Andrzej Zawada headed the first winter ascent of Mount Everest, the first winter ascent of an eight-thousander. The team of 20 Polish climbers and 4 Sherpas established a base camp on Khumbu Glacier in early January 1980. On 15 January, the team managed to set up Camp III at 7150 metres above sea level, but further action was stopped by hurricane-force winds. The weather improved after 11 February, when Leszek Cichy, Walenty Fiut and Krzysztof Wielicki set up camp IV on South Col (7906 m). Cichy and Wielicki started the final ascent at 6:50 am on 17 February. At 2:40 pm Andrzej Zawada at base camp heard the climbers’ voices over the radio – «We are on the summit! The strong wind blows all the time. It is unimaginably cold.»[117][118][119][120] The successful winter ascent of Mount Everest started a new decade of Winter Himalaism, which became a Polish specialisation. After 1980 Poles did ten first winter ascents on 8000 metre peaks, which earned Polish climbers a reputation of «Ice Warriors».[121][118][122][123]

Lho La tragedy, 1989

In May 1989, Polish climbers under the leadership of Eugeniusz Chrobak organised an international expedition to Mount Everest on a difficult western ridge. Ten Poles and nine foreigners participated, but ultimately only the Poles remained in the attempt for the summit. On 24 May, Chrobak and Andrzej Marciniak, starting from camp V at 8,200 m, overcame the ridge and reached the summit. But on 27 May, during an avalanche from the side of Khumbutse near the Lho La pass, four Polish climbers were killed: Mirosław Dąsal, Mirosław Gardzielewski, Zygmunt Andrzej Heinrich and Wacław Otręba. The following day, due to his injuries, Chrobak also died. Marciniak, who was also injured, was saved by a rescue expedition in which Artur Hajzer and New Zealanders Gary Ball and Rob Hall took part. In the organisation of the rescue expedition they took part, inter alia Reinhold Messner, Elizabeth Hawley, Carlos Carsolio and the US consul.[124]

1996 disaster

On 10 and 11 May 1996, eight climbers died after several guided expeditions were caught in a blizzard high up on the mountain during a summit attempt on 10 May. During the 1996 season, 15 people died while climbing on Mount Everest. These were the highest death tolls for a single weather event, and for a single season, until the sixteen deaths in the 2014 Mount Everest avalanche. The guiding disaster gained wide publicity and raised questions about the commercialisation of climbing and the safety of guiding clients on Mount Everest.

Journalist Jon Krakauer, on assignment from Outside magazine, was in one of the affected guided parties, and afterward published the bestseller Into Thin Air, which related his experience. Krakauer was critical of guide Anatoli Boukreev in his recollection of the expedition.[125][126] A year later, Boukreev co-authored The Climb, in part as a rebuttal of Krakauer’s portrayal.[127] The dispute sparked a debate within the climbing community. Boukreev was later awarded The American Alpine Club’s David Sowles Award for his rescue efforts on the expedition.[126]

In May 2004, physicist Kent Moore and surgeon John L. Semple, both researchers from the University of Toronto, told New Scientist magazine that an analysis of weather conditions on 11 May suggested that weather caused oxygen levels to plunge about 14 per cent.[128][129]

One of the survivors was Beck Weathers, an American client of New Zealand–based guide service Adventure Consultants. Weathers was left for dead about 275 metres (900 feet) from Camp 4 at 7,950 metres (26,085 feet). After spending a night on the mountain, Weathers managed to make it back to Camp 4 with massive frostbite and vision impaired due to snow blindness.[130] When he arrived at Camp 4, fellow climbers considered his condition terminal and left him in a tent to die overnight.[131]

Weathers’ condition had not improved and an immediate descent to a lower elevation was deemed essential.[131] A helicopter rescue was out of the question: Camp 4 was higher than the rated ceiling of any available helicopter. Weathers was lowered to Camp 2. Eventually, a helicopter rescue was organised thanks to the Nepali Army.[130][131]

The storm’s impact on climbers on the North Ridge of Everest, where several climbers also died, was detailed in a first-hand account by British filmmaker and writer Matt Dickinson in his book The Other Side of Everest. Sixteen-year-old Mark Pfetzer was on the climb and wrote about it in his account, Within Reach: My Everest Story.

The 2015 feature film Everest, directed by Baltasar Kormákur, is based on the events of this guiding disaster.[132]

2006 mountaineering season

| 2006 fatalities | |

|---|---|

| Deaths[133] | Nation[134] |

| Tuk Bahadur Thapa Masa | |

| Igor Plyushkin | |

| Vitor Negrete | |

| David Sharp | |

| Thomas Weber | |

| Tomas Olsson | |

| Jacques-Hugues Letrange | |

| Ang Phinjo | |

| *Pavel Kalny | |

| Lhakpa Tseri[135] | |

| Dawa Temba[135] | |

| Sri Kishan[134] | |

| *Lhotse face fatality |

Small avalanche on Everest, 2006

In 2006, 12 people died. One death in particular (see below) triggered an international debate and years of discussion about climbing ethics.[136] The season was also remembered for the rescue of Lincoln Hall who had been left by his climbing team and declared dead, but was later discovered alive and survived being helped off the mountain.

David Sharp ethics controversy, 2006

There was an international controversy about the death of a solo British climber David Sharp, who attempted to climb Mount Everest in 2006 but died in his attempt. The story broke out of the mountaineering community into popular media, with a series of interviews, allegations, and critiques. The question was whether climbers that season had left a man to die and whether he could have been saved. He was said to have attempted to summit Mount Everest by himself with no Sherpa or guide and fewer oxygen bottles than considered normal.[137] He went with a low-budget Nepali guide firm that only provides support up to Base Camp, after which climbers go as a «loose group», offering a high degree of independence. The manager at Sharp’s guide support said Sharp did not take enough oxygen for his summit attempt and did not have a Sherpa guide.[138] It is less clear who knew Sharp was in trouble, and if they did know, whether they were qualified or capable of helping him.[137]

Double-amputee climber Mark Inglis said in an interview with the press on 23 May 2006, that his climbing party, and many others, had passed Sharp, on 15 May, sheltering under a rock overhang 450 metres (1,480 ft) below the summit, without attempting a rescue.[139] Inglis said 40 people had passed by Sharp, but he might have been overlooked as climbers assumed Sharp was the corpse nicknamed «Green Boots»,[140] but Inglis was not aware that Turkish climbers had tried to help Sharp despite being in the process of helping an injured woman down (a Turkish woman, Burçak Poçan). There has also been some discussion about Himex in the commentary on Inglis and Sharp. In regards to Inglis’s initial comments, he later revised certain details because he had been interviewed while he was «…physically and mentally exhausted, and in a lot of pain. He had suffered severe frostbite – he later had five fingertips amputated.» When they went through Sharp’s possessions they found a receipt for US$7,490, believed to be the whole financial cost.[141] Comparatively, most expeditions are between $35,000 to US$100,000 plus an additional $20,000 in other expenses that range from gear to bonuses.[142] It was estimated on 14 May that Sharp summitted Mount Everest and began his descent down, but 15 May he was in trouble but being passed by climbers on their way up and down.[143] On 15 May 2006 it is believed he was suffering from hypoxia and was about 300 m (1,000 ft) from the summit on the North Side route.[143]

Dawa from Arun Treks also gave oxygen to David and tried to help him move, repeatedly, for perhaps an hour. But he could not get David to stand alone or even stand to rest on his shoulders, and crying, Dawa had to leave him too. Even with two Sherpas, it was not going to be possible to get David down the tricky sections below.

— Jamie McGuiness[144]

Beck Weathers of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster said that those who are dying are often left behind and that he himself had been left for dead twice but was able to keep walking.[145] The Tribune of Chandigarh, India quoted someone who described what happened to Sharp as «the most shameful act in the history of mountaineering».[146] In addition to Sharp’s death, at least nine other climbers perished that year, including multiple Sherpas working for various guiding companies.[147]

You are never on your own. There are climbers everywhere.

— David Sharp[148]

Much of this controversy was captured by the Discovery Channel while filming the television program Everest: Beyond the Limit. A crucial decision affecting the fate of Sharp is shown in the program, where an early returning climber Lebanese adventurer Maxim Chaya is descending from the summit and radios to his base camp manager (Russell Brice) that he has found a frostbitten and unconscious climber in distress. Chaya is unable to identify Sharp, who had chosen to climb solo without any support and so did not identify himself to other climbers. The base camp manager assumes that Sharp is part of a group that has already calculated that they must abandon him, and informs his lone climber that there is no chance of him being able to help Sharp by himself. As Sharp’s condition deteriorates through the day and other descending climbers pass him, his opportunities for rescue diminish: his legs and feet curl from frostbite, preventing him from walking; the later descending climbers are lower on oxygen and lack the strength to offer aid; time runs out for any Sherpas to return and rescue him.

David Sharp’s body remained just below the summit on the Chinese side next to «Green Boots»; they shared a space in a small rock cave that was an ad hoc tomb for them.[143] Sharp’s body was removed from the cave in 2007, according to the BBC,[149] and since 2014, Green Boots has been missing, presumably removed or buried.[150]

Lincoln Hall rescue, 2006

As the Sharp debate kicked off on 26 May 2006, Australian climber Lincoln Hall was found alive after being left for dead the day before.[151] He was found by a party of four climbers (Dan Mazur, Andrew Brash, Myles Osborne and Jangbu Sherpa) who, giving up their own summit attempt, stayed with Hall and descended with him and a party of 11 Sherpas sent up to carry him down. Hall later fully recovered. His team assumed he had died from cerebral edema, and they were instructed to cover him with rocks.[151] There were no rocks around to do this and he was abandoned.[152] The erroneous information of his death was passed on to his family. The next day he was discovered alive by another party.[152]

I was shocked to see a guy without gloves, hat, oxygen bottles or sleeping bag at sunrise at 28,200 feet [8,600 m] height, just sitting up there.

— Dan Mazur[152]

Lincoln greeted his fellow mountaineers with this:[152]

I imagine you are surprised to see me here.

— Lincoln Hall[152]

Lincoln Hall went on to live for several more years, often giving talks about his near-death experience and rescue, before dying from unrelated medical issues in 2012 at the age of 56 (born in 1955).[152]

2007

On 21 May 2007, Canadian climber Meagan McGrath initiated the successful high-altitude rescue of Nepali Usha Bista. Recognising this rescue, Major McGrath was selected as a 2011 recipient of the Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation of Canada Humanitarian Award, which recognises a Canadian who has personally or administratively contributed a significant service or act in the Himalayan Region of Nepal.[153]

Ascent statistics up to 2010 season

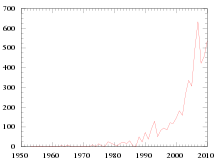

Ascents of Mount Everest by year through 2010

The sun rising on Everest in 2011

By the end of the 2010 climbing season, there had been 5,104 ascents to the summit by about 3,142 individuals, with 77 per cent of these ascents being accomplished since 2000.[154] The summit was achieved in 7 of the 22 years from 1953 to 1974 and was not missed between 1975 and 2014.[154] In 2007, the record number of 633 ascents was recorded, by 350 climbers and 253 sherpas.[154]

An illustration of the explosion of popularity of Everest is provided by the numbers of daily ascents. Analysis of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster shows that part of the blame was on the bottleneck caused by a large number of climbers (33 to 36) attempting to summit on the same day; this was considered unusually high at the time. By comparison, on 23 May 2010, the summit of Mount Everest was reached by 169 climbers – more summits in a single day than in the cumulative 31 years from the first successful summit in 1953 through 1983.[154]

There have been 219 fatalities recorded on Mount Everest from the 1922 British Mount Everest Expedition through the end of 2010, a rate of 4.3 fatalities for every 100 summits (this is a general rate, and includes fatalities amongst support climbers, those who turned back before the peak, those who died en route to the peak and those who died while descending from the peak). Of the 219 fatalities, 58 (26.5 per cent) were climbers who had summited but did not complete their descent.[154] Though the rate of fatalities has decreased since the year 2000 (1.4 fatalities for every 100 summits, with 3938 summits since 2000), the significant increase in the total number of climbers still means 54 fatalities since 2000: 33 on the northeast ridge, 17 on the southeast ridge, 2 on the southwest face, and 2 on the north face.[154]

Nearly all attempts at the summit are done using one of the two main routes. The traffic seen by each route varies from year to year. In 2005–07, more than half of all climbers elected to use the more challenging, but cheaper northeast route. In 2008, the northeast route was closed by the Chinese government for the entire climbing season, and the only people able to reach the summit from the north that year were athletes responsible for carrying the Olympic torch for the 2008 Summer Olympics.[155] The route was closed to foreigners once again in 2009 in the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s exile.[156] These closures led to declining interest in the north route, and, in 2010, two-thirds of the climbers reached the summit from the south.[154]

2010s

Selfie on the summit, 2012

The 2010s were a time of new highs and lows for the mountain, with back-to-back disasters in 2013 and 2014 causing record deaths. In 2015 there were no summits for the first time in decades. However, other years set records for numbers of summits – 2013’s record number of summiters, around 667, was surpassed in 2018 with around 800 summiting the peak,[157] and a subsequent record was set in 2019 with over 890 summiters.[158]

| Year | Summiters | References |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 543 | [158] |

| 2011 | 538 | [158] |

| 2012 | 547 | [159] |

| 2013 | 658–670 | [160][158] |

| 2014 | 106 | [161] |

| 2015 | 0 | [162][158] |

| 2016 | 641 | [163] |

| 2017 | 648 | [164] |

| 2018 | 807 | [157][165] |

| 2019 | approx. 891 | [158] |

2014 avalanche and season

On 18 April 2014, an avalanche hit the area just below the Base Camp 2 at around 01:00 UTC (06:30 local time) and at an elevation of about 5,900 metres (19,400 ft).[166] Sixteen people were killed in the avalanche (all Nepali guides) and nine more were injured.[167]

During the season, a 13-year-old girl, Malavath Purna, reached the summit, becoming the youngest female climber to do so.[168] Additionally, one team used a helicopter to fly from South base camp to Camp 2 to avoid the Khumbu Icefall, then reached the Everest summit. This team had to use the south side because the Chinese had denied them a permit to climb. A team member (Jing Wang) donated US$30,000 to a local hospital.[169] She was named the Nepali «International Mountaineer of the Year».[169]

The location of the fatal ice avalanche on the 2014 route, and the revised 2015 route through the Khumbu.

Over 100 people summited Everest from China (Tibet region), and six from Nepal in the 2014 season.[170] This included 72-year-old Bill Burke, the Indian teenage girl, and a Chinese woman Jing Wang.[171] Another teen girl summiter was Ming Kipa Sherpa who summited with her elder sister Lhakpa Sherpa in 2003, and who had achieved the most times for woman to the summit of Mount Everest at that time.[172] (see also Santosh Yadav)

2015 avalanche, earthquake, season

2015 was set to be a record-breaking season of climbs, with hundreds of permits issued in Nepal and many additional permits in Tibet (China). However, on 25 April 2015, an earthquake measuring 7.8 Mw triggered an avalanche that hit Everest Base Camp,[173] effectively shutting down the Everest climbing season.[174] 18 bodies were recovered from Mount Everest by the Indian Army mountaineering team.[175] The avalanche began on Pumori,[176] moved through the Khumbu Icefall on the southwest side of Mount Everest, and slammed into the South Base Camp.[177] 2015 was the first time since 1974 with no spring summits, as all climbing teams pulled out after the quakes and avalanche.[178][179] One of the reasons for this was the high probability of aftershocks (over 50 per cent according to the United States Geological Survey).[180] Just weeks after the first quake, the region was rattled again by a 7.3 magnitude quake and there were also many considerable aftershocks.[181]

The quakes trapped hundreds of climbers above the Khumbu icefall, and they had to be evacuated by helicopter as they ran low on supplies.[182] The quake shifted the route through the ice fall, making it essentially impassable to climbers.[182] Bad weather also made helicopter evacuation difficult.[182] The Everest tragedy was small compared to the impact overall on Nepal, with almost nine thousand dead[183][184] and about 22,000 injured.[183] In Tibet, by 28 April at least 25 had died, and 117 were injured.[185] By 29 April 2015, the Tibet Mountaineering Association (North/Chinese side) closed Everest and other peaks to climbing, stranding 25 teams and about 300 people on the north side of Everest.[186] On the south side, helicopters evacuated 180 people trapped at Camps 1 and 2.[187]

Mountain re-opens in August 2015

On 24 August 2015, Nepal re-opened Everest to tourism including mountain climbers.[188] The only climber permit for the autumn season was awarded to Japanese climber Nobukazu Kuriki, who had tried four times previously to summit Everest without success. He made his fifth attempt in October, but had to give up just 700 m (2,300 ft) from the summit due to «strong winds and deep snow».[189][190] Kuriki noted the dangers of climbing Everest, having himself survived being stuck in a freezing snow hole for two days near the top, which came at the cost of all his fingertips and his thumb, lost to frostbite, which added further difficulty to his climb.[191]

Some sections of the trail from Lukla to Everest Base Camp (Nepal) were damaged in the earthquakes earlier in the year and needed repairs to handle trekkers.[192]

2016 season

Hawley’s database records 641 made it to the summit in early 2016.[193]

2017 season

2017 was the biggest season yet, permit-wise, yielding hundreds of summiters and a handful of deaths.[194] On 27 May 2017, Kami Rita Sherpa made his 21st climb to the summit with the Alpine Ascents Everest Expedition, one of three people in the World along with Apa Sherpa and Phurba Tashi Sherpa to make it to the summit of Mount Everest 21 times.[195][196] The season had a tragic start with the death of Ueli Steck of Switzerland, who died from a fall during a warm-up climb.[197] There was a continued discussion about the nature of possible changes to the Hillary Step.[198] Total summiters for 2017 was tallied up to be 648.[164] 449 summited via Nepal (from the South) and 120 from Chinese Tibet (North side).[199]

2018

Mount Everest in the upper left (March 2018)

807 climbers summited Mount Everest in 2018,[200] including 563 on the Nepal side and 240 from the Chinese Tibet side.[157] This broke the previous record for total summits in year from which was 667 in 2013, and one factor that aided in this was an especially long and clear weather window of 11 days during the critical spring climbing season.[157][201][165] Various records were broken, including a summit by double-amputee Hari Budha Magar, who undertook his climb after winning a court case in the Nepali Supreme Court.[157] There were no major disasters, but seven climbers died in various situations including several sherpas as well as international climbers.[157] Although record numbers of climbers reached the summit, old-time summiters that made expeditions in the 1980s lamented the crowding, feces, and cost.[201]

Himalayan record keeper Elizabeth Hawley died in late January 2018.[202]

Figures for the number of permits issued by Nepal range from 347[203] to 375.[204]

2019

| 2019 fatalities[205] | |

|---|---|

| Fatalities | Nationality |

| Chris Daly | |

| Donald Cash | |

| Robin Fisher | |

| Druba Bista | |

| Kevin Hynes | |

| Kalpana Dash | |

| Anjali S. Kulkarni | |

| Ernst Landgraf | |

| Nihal Bagwan | |

| Ravi Thakar | |

| Chris Kulish | |

| Séamus Lawless*[206] | |

| *Declared dead after missing |

The spring or pre-monsoon window for 2019 witnessed the deaths of a number of climbers and worldwide publication of images of hundreds of mountaineers queuing to reach the summit and sensational media reports of climbers stepping over dead bodies dismayed people around the world.[207][208][209]

There were reports of various winter expeditions in the Himalayas, including K2, Nanga Parbat, and Meru with the buzz for the Everest 2019 beginning just 14 weeks to the weather window.[210] Noted climber Cory Richards announced on Twitter that he was hoping to establish a new climbing route to the summit in 2019.[210] Also announced was an expedition to re-measure the height of Everest, particularly in light of the 2015 earthquakes.[211][212] China closed the base-camp to those without climbing permits in February 2019 on the northern side of Mount Everest.[213] By early April, climbing teams from around the world were arriving for the 2019 spring climbing season.[165] Among the teams was a scientific expedition with a planned study of pollution, and how things like snow and vegetation influence the availability of food and water in the region.[214] In the 2019 spring mountaineering season, there were roughly 40 teams with almost 400 climbers and several hundred guides attempting to summit on the Nepali side.[215][216][217] Nepal issued 381 climbing permits for 2019.[200] For the northern routes in Chinese Tibet, several hundred more permits were issued for climbing by authorities there.[218]

In May 2019, Nepali mountaineering guide Kami Rita summited Mount Everest twice within a week, his 23rd and 24th ascents, making international news headlines.[219][215][216] He first summited Everest in 1994, and has summited several other extremely high mountains, such as K2 and Lhotse.[215][216][217][219]

By 23 May 2019, about seven people had died, possibly due to crowding leading to delays high on the mountain, and shorter weather windows.[200] One 19-year-old who summited previously noted that when the weather window opens (the high winds calm down), long lines form as everyone rushes to get the top and back down.[220] In Chinese Tibet, one Austrian climber died from a fall,[200] and by 26 May 2019 the overall number of deaths for the spring climbing season rose to 10.[221][222][223] By 28 May, the death toll increased to 11 when a climber died at about 7,900 m (26,000 ft) during the descent,[205] and a 12th climber missing and presumed dead.[206] Despite the number of deaths, reports indicated that a record 891 climbers summited in the spring 2019 climbing season.[224][158]

Although China has had various permit restrictions, and Nepal requires a doctor to sign off on climbing permits,[224] the natural dangers of climbing such as falls and avalanches combined with medical issues aggravated by Everest’s extreme altitude led to 2019 being a year with a comparatively high death toll.[224]

2020s

Both Nepal and China prohibited foreign climbing groups during the 2020 season, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020 was the third year in this decade after 2014 and 2015 which saw no summits from the Nepal (South) Side.[225]

A team of Chinese surveyors climbed Mt. Everest from the North side during April–May 2020, becoming the only climbers to summit the world’s highest peak during the pandemic, at least through May. The team was there to re-measure the height of Mount Everest.[226]

On 12 May 2022, the first all-Black team summited Mt. Everest. Seven men and two women climbers from the U.S. and Kenya, guided by eight sherpas, comprised the expedition.[227]

Climbing

Looking up along the southern ridgeline, the face of the Hillary Step is visible. The top of the South-West face is on the left in shadow, and in the light to the right is the top of the East/Kangshung face. In 2016 and 2017 there were serious reports that the Hillary Step was changed, which triggered a big discussion in the climbing community. (2010 photo)

| Location | Altitude (km) | |

|---|---|---|

| Base camp 5400 m / 17700 ft. | 5.4 | |

| Camp 1 6100 m / 20000 ft. | 6.1 | |

| Camp 2 6400 m / 21000 ft. | 6.4 | |

| Camp 3 6800m / 22300 ft. | 6.8 | |

| Camp 4 8000 m / 26000 ft. | 8 | |

| Summit 8848 m / 29035 ft. | 8.8 |

Permits

In 2014, Nepal issued 334 climbing permits, which were extended until 2019 due to the closure.[229] In 2015, Nepal issued 357 permits, but the mountain was closed again because of the avalanche and earthquake, and these permits were given a two-year extension to 2017.[230][229][clarification needed]

In 2017, a person who tried to climb Everest without the $11,000 permit was caught after he made it past the Khumbu icefall. He faced, among other penalties, a $22,000 fine and a possible four years in jail. In the end, he was allowed to return home but banned from mountaineering in Nepal for 10 years.[231]

The number of permits issued each year by Nepal is:[230][232]

- 2008: 160

- 2009: 220

- 2010: 209

- 2011: 225

- 2012: 208

- 2013: 316

- 2014: 326 (extended for use through 2019)

- 2015: 356 (extended for use through 2017)

- 2016: 289

- 2017: 366 to 373

- 2018: 346

- 2019: 381

- 2020: 0 (no permits issued during the pandemic)

- 2021: 408 (current record)[233][234]

The Chinese side in Tibet is also managed with permits for summiting Everest.[235] They did not issue permits in 2008, due to the Olympic torch relay being taken to the summit of Mount Everest.[236]

In March 2020, the governments of China and Nepal cancelled all climbing permits for Mount Everest due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[237][238] In April 2020, a group of Chinese mountaineers began an expedition from the Chinese side. The mountain remained closed on the Chinese side to all foreign climbers.[239] On 10 May 2021, a separation line was announced by Chinese authorities to prevent the spread of coronavirus from climbers ascending Nepal’s side of the mountain.[240]

Routes

Overview South Col route and North Col/Ridge route

Mount Everest has two main climbing routes, the southeast ridge from Nepal and the north ridge from Tibet, as well as many other less frequently climbed routes.[241] Of the two main routes, the southeast ridge is technically easier and more frequently used. It was the route used by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953 and the first recognised of 15 routes to the top by 1996.[241] This was, however, a route decision dictated more by politics than by design, as the Chinese border was closed to the western world in the 1950s, after the People’s Republic of China invaded Tibet.[242]

Most attempts are made during May, before the summer monsoon season. As the monsoon season approaches, the jet stream shifts northward, thereby reducing the average wind speeds high on the mountain.[243][244] While attempts are sometimes made in September and October, after the monsoons, when the jet stream is again temporarily pushed northward, the additional snow deposited by the monsoons and the less stable weather patterns at the monsoons’ tail end makes climbing extremely difficult.

Southeast ridge

The ascent via the southeast ridge begins with a trek to Base Camp at 5,380 m (17,700 ft) on the south side of Everest, in Nepal. Expeditions usually fly into Lukla (2,860 m) from Kathmandu and pass through Namche Bazaar. Climbers then hike to Base Camp, which usually takes six to eight days, allowing for proper altitude acclimatisation in order to prevent altitude sickness.[245] Climbing equipment and supplies are carried by yaks, dzopkyos (yak-cow hybrids), and human porters to Base Camp on the Khumbu Glacier. When Hillary and Tenzing climbed Everest in 1953, the British expedition they were part of (comprising over 400 climbers, porters, and Sherpas at that point) started from the Kathmandu Valley, as there were no roads further east at that time.

Climbers spend a couple of weeks in Base Camp, acclimatising to the altitude. During that time, Sherpas and some expedition climbers set up ropes and ladders in the treacherous Khumbu Icefall.

Seracs, crevasses, and shifting blocks of ice make the icefall one of the most dangerous sections of the route. Many climbers and Sherpas have been killed in this section. To reduce the hazard, climbers usually begin their ascent well before dawn, when the freezing temperatures glue ice blocks in place.

Above the icefall is Camp I at 6,065 metres (19,900 ft).

Climber traversing Khumbu Icefall

From Camp I, climbers make their way up the Western Cwm to the base of the Lhotse face, where Camp II or Advanced Base Camp (ABC) is established at 6,500 m (21,300 ft). The Western Cwm is a flat, gently rising glacial valley, marked by huge lateral crevasses in the centre, which prevent direct access to the upper reaches of the Cwm. Climbers are forced to cross on the far right, near the base of Nuptse, to a small passageway known as the «Nuptse corner». The Western Cwm is also called the «Valley of Silence» as the topography of the area generally cuts off wind from the climbing route. The high altitude and a clear, windless day can make the Western Cwm unbearably hot for climbers.[246]

From Advanced Base Camp, climbers ascend the Lhotse face on fixed ropes, up to Camp III, located on a small ledge at 7,470 m (24,500 ft). From there, it is another 500 metres to Camp IV on the South Col at 7,920 m (26,000 ft).

From Camp III to Camp IV, climbers are faced with two additional challenges: the Geneva Spur and the Yellow Band. The Geneva Spur is an anvil-shaped rib of black rock named by the 1952 Swiss expedition. Fixed ropes assist climbers in scrambling over this snow-covered rock band. The Yellow Band is a section of interlayered marble, phyllite, and semischist, which also requires about 100 metres of rope for traversing it.[246]

On the South Col, climbers enter the death zone. Climbers making summit bids typically can endure no more than two or three days at this altitude. If the weather is not clear with low winds during these short few days, climbers are forced to descend, many all the way back down to Base Camp.

From Camp IV, climbers begin their summit push around midnight, with hopes of reaching the summit (still another 1,000 metres above) within 10 to 12 hours. Climbers first reach «The Balcony» at 8,400 m (27,600 ft), a small platform where they can rest and gaze at peaks to the south and east in the early light of dawn. Continuing up the ridge, climbers are then faced with a series of imposing rock steps which usually forces them to the east into the waist-deep snow, a serious avalanche hazard. At 8,750 m (28,700 ft), a small table-sized dome of ice and snow marks the South Summit.[246]

From the South Summit, climbers follow the knife-edge southeast ridge along what is known as the «Cornice traverse», where snow clings to intermittent rock. This is the most exposed section of the climb, and a misstep to the left would send one 2,400 m (7,900 ft) down the southwest face, while to the immediate right is the 3,050 m (10,010 ft) Kangshung Face. At the end of this traverse is an imposing 12 m (39 ft) rock wall, the Hillary Step, at 8,790 m (28,840 ft).[247]

Hillary and Tenzing were the first climbers to ascend this step, and they did so using primitive ice climbing equipment and ropes. Nowadays, climbers ascend this step using fixed ropes previously set up by Sherpas. Once above the step, it is a comparatively easy climb to the top on moderately angled snow slopes—though the exposure on the ridge is extreme, especially while traversing large cornices of snow. With increasing numbers of people climbing the mountain in recent[when?] years, the Step has frequently become a bottleneck, with climbers forced to wait significant amounts of time for their turn on the ropes, leading to problems in getting climbers efficiently up and down the mountain.[citation needed]

After the Hillary Step, climbers also must traverse a loose and rocky section that has a large entanglement of fixed ropes that can be troublesome in bad weather. Climbers typically spend less than half an hour at the summit to allow time to descend to Camp IV before darkness sets in, to avoid serious problems with afternoon weather, or because supplemental oxygen tanks run out.

North ridge route

Mount Everest north face from Rongbuk in Tibet

The north ridge route begins from the north side of Everest, in Tibet. Expeditions trek to the Rongbuk Glacier, setting up base camp at 5,180 m (16,990 ft) on a gravel plain just below the glacier. To reach Camp II, climbers ascend the medial moraine of the east Rongbuk Glacier up to the base of Changtse, at around 6,100 m (20,000 ft). Camp III (ABC—Advanced Base Camp) is situated below the North Col at 6,500 m (21,300 ft). To reach Camp IV on the North Col, climbers ascend the glacier to the foot of the col where fixed ropes are used to reach the North Col at 7,010 m (23,000 ft). From the North Col, climbers ascend the rocky north ridge to set up Camp V at around 7,775 m (25,500 ft). The route crosses the North Face in a diagonal climb to the base of the Yellow Band, reaching the site of Camp VI at 8,230 m (27,000 ft). From Camp VI, climbers make their final summit push.

Climbers face a treacherous traverse from the base of the First Step: ascending from 8,501 to 8,534 m (27,890 to 28,000 ft), to the crux of the climb, the Second Step, ascending from 8,577 to 8,626 m (28,140 to 28,300 ft). (The Second Step includes a climbing aid called the «Chinese ladder», a metal ladder placed semi-permanently in 1975 by a party of Chinese climbers.[248] It has been almost continuously in place since, and ladders have been used by virtually all climbers on the route.) Once above the Second Step the inconsequential Third Step is clambered over, ascending from 8,690 to 8,800 m (28,510 to 28,870 ft). Once above these steps, the summit pyramid is climbed by a snow slope of 50 degrees, to the final summit ridge along which the top is reached.[249]

Summit

A view from the summit of Mount Everest in May 2013

The summit of Everest has been described as «the size of a dining room table».[250] The summit is capped with snow over ice over rock, and the layer of snow varies from year to year.[251] The rock summit is made of Ordovician limestone and is a low-grade metamorphic rock.[252] (see the ‘Surveys’ section for more on its height and about the Everest rock summit)

Below the summit, there is an area known as «rainbow valley», filled with dead bodies still wearing brightly coloured winter gear. Down to about 8,000 m (26,000 ft) is an area commonly called the «death zone», due to the high danger and low oxygen because of the low pressure.[83]

Below the summit the mountain slopes downward to the three main sides, or faces, of Mount Everest: the North Face, the South-West Face, and the East/Kangshung Face.[253][better source needed]

Death zone

The summit of Mount Everest from the North side

At the higher regions of Mount Everest, climbers seeking the summit typically spend substantial time within the death zone (altitudes higher than 8,000 metres (26,000 ft)), and face significant challenges to survival. Temperatures can dip to very low levels, resulting in frostbite of any body part exposed to the air. Since temperatures are so low, snow is well-frozen in certain areas and death or injury by slipping and falling can occur. High winds at these altitudes on Everest are also a potential threat to climbers.

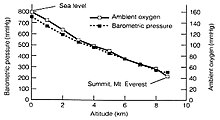

Another significant threat to climbers is low atmospheric pressure. The atmospheric pressure at the top of Everest is about a third of sea level pressure or 0.333 standard atmospheres (337 mbar), resulting in the availability of only about a third as much oxygen to breathe.[254]

Debilitating effects of the death zone are so great that it takes most climbers up to 12 hours to walk the distance of 1.72 kilometres (1.07 mi) from South Col to the summit.[255] Achieving even this level of performance requires prolonged altitude acclimatisation, which takes 40–60 days for a typical expedition. A sea-level dweller exposed to the atmospheric conditions at the altitude above 8,500 m (27,900 ft) without acclimatisation would likely lose consciousness within 2 to 3 minutes.[256]

In May 2007, the Caudwell Xtreme Everest undertook a medical study of oxygen levels in human blood at extreme altitude. Over 200 volunteers climbed to Everest Base Camp where various medical tests were performed to examine blood oxygen levels. A small team also performed tests on the way to the summit.[257] Even at base camp, the low partial pressure of oxygen had direct effect on blood oxygen saturation levels. At sea level, blood oxygen saturation is generally 98 to 99 per cent. At base camp, blood saturation fell to between 85 and 87 per cent. Blood samples taken at the summit indicated very low oxygen levels in the blood. A side effect of low blood oxygen is a greatly increased breathing rate, often 80–90 breaths per minute as opposed to a more typical 20–30. Exhaustion can occur merely by attempting to breathe.[258]

Lack of oxygen, exhaustion, extreme cold, and climbing hazards all contribute to the death toll. An injured person who cannot walk is in serious trouble, since rescue by helicopter is generally impractical and carrying the person off the mountain is very risky. People who die during the climb are typically left behind. As of 2006, about 150 bodies had never been recovered. It is not uncommon to find corpses near the standard climbing routes.[259]

Debilitating symptoms consistent with high altitude cerebral oedema commonly present during descent from the summit of Mount Everest. Profound fatigue and late times in reaching the summit are early features associated with subsequent death.

— Mortality on Mount Everest, 1921–2006: descriptive study[260]

A 2008 study noted that the «death zone» is indeed where most Everest deaths occur, but also noted that most deaths occur during descent from the summit.[261] A 2014 article in The Atlantic about deaths on Everest noted that while falling is one of the greatest dangers the death zone presents for all 8000ers, avalanches are a more common cause of death at lower altitudes.[262] However, Everest climbing is more deadly than BASE jumping, although some have combined extreme sports and Everest including a Russian who base-jumped off Everest in a wingsuit (he did survive, though).[263]