The intensity of its physical expression. Snatching words from memory the split second before they swing and hang in the room in front of you. The release of something so deeply personal with the raw tools of one’s being.

My first spoken word performance itched with pre-show anxiety and all its peculiar manifestations. We all deal with unwieldy nerves in different ways; some puke before a show, some need solitude. I learnt that on that day, and at every performance since, I need:

- An unusual amount of water

- To make several visits to the urinal (especially just before going on)

- To have conversation as a babbling soundscape but not to be expected to contribute, therein coming across as a rude bastard to strangers

Since then I’ve performed at festivals in Denmark, with jazz musicians in Southern Africa, with vocal ensembles in mainland Europe, run workshops with inspiring young voices from Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Scandinavia, and collaborated with artists from all over the world. The spoken word has always had a possessive element to it for me. I know of no other avenue through which the word can be delivered that ties me so tightly to someone’s thoughts and struggles in the space of a few minutes.

As a teenager, the mathematical dismembering of written poetry in thickset anthologies killed the enigma and subjective nourishment that makes the word so special. Getting lost in words is difficult when you’re encouraged to look for the ‘right’ path or answer in something so vast and fluid. Spoken word and hip-hop felt like wide open spaces in comparison.

If you want to sit by someone’s side for a while and hear the grinding that pushes and pulls them, then here’s my (savagely refined) list of favourites online:

1. Buddy Wakefield — “Convenience Stores”

Why not start at the top? I was into hip-hop before and during my introduction to spoken word. My housemate in my second year at university was one of those crazed hip-hop intellectuals who excavated careers and labels to give you the bones and backstories of all the artists you had and hadn’t heard of.

Sage Francis featured a guy called Buddy Wakefield on one of his albums, and my hip-hop fiend of a friend recommended I listen to the following poem. No piece of music, film, or any other form of artistic expression has had the same clawing effect on me as this:

2. Kate Tempest — “Line in the Sand”

I first met Kate Tempest at a show in a basement in a totalitarian vegan café in Brighton, UK. I joined other acts in the opening slots before her. I crossed her path once more a couple years ago when she was screening one of her pieces at an event in London and her name had already begun to sound on radio and television:

3. LKJ — “Inglan Is a Bitch”

Linton Kwesi Johnson, or LKJ as he’s commonly known, is the father of dub poetry. His poetry gyrates with a cadence born in the Caribbean, and his content is shaped by his experiences as a young man in the UK, highlighting police brutality, racism, and life on the concrete island. A timeless flow and message with or without the backing of a band:

4. Dizraeli — “Maria”

Poems on politicians, verses on bombing supermarket chains, and a deep human resonance and skill for storytelling make Dizraeli one of the illest emcees and spoken word artists around. The following piece, “Maria,” has been known to make the most unbreakable, emotionless zombies shed a tear:

5. TJ Dema — “Neon Poem”

Representing Botswana, TJ Dema has featured at events around the world and never failed to capture audience members and performers as she does so. She is a fellow member of the spoken word / jazz fusion group Sonic Slam Chorus and has a truly unique style and manner of describing her world in a way that calls on all your senses:

6. Toby T — “Tomorrow”

I only heard of this lyrical talent recently. Toby T’s face gives away the fact that he’s in the twilight of his adolescence. His content suggests he’s at the foothills of a promising career. With a staggered flow, Toby’s feelings stammer out against the backdrop of delicate musicianship. Check out other videos online that show his versatility as a poet and emcee, but start here:

7. Andrea Gibson and Katie Wirsing

The links that the online searches will suggest can lead you further on a journey into the word to find other talented practitioners. That’s partly how I came across Andrea Gibson and Katie Wirsing. I had seen them perform on a UK tour once and forgotten their names only to stumble on them online.

Below they perform a poem by Christian Drake, probably the most brutally beautiful and violently heartfelt, blood-stained love poem you will ever come across:

8. Shane Koyczan – “To This Day”

Canadian poet Shane Koyczan released an animated spoken word video earlier this year that has rocketed towards 9 million views on YouTube. A jolting piece on bullying and an anthem for the bullied. Arguably one of the best visual presentations in spoken word accompanies it:

Last year the BBC Learning English website asked people from around the world to nominate their favourite quotations – from speeches, books, poetry and plays … whatever they liked. The winner was, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step” from Lao Tzu. The runners up were as follows:

- “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind” Mahatma Ghandi

- If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.” Nelson Mandela.

- “Better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved at all” Saint Augustine.

- “You can’t shake hands with a clenched fist.” Dalai Lama

- “And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise.” Gospel of Luke, 6.31

I loved the ideas and I am going to run the same competition until the end of October. Post a comment with your favourite quote on the blog. Either vote for a favourite quote that someone has suggested or add your own quote. Prizes will be given out but you will have to wait and see for what!

© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy

Listener

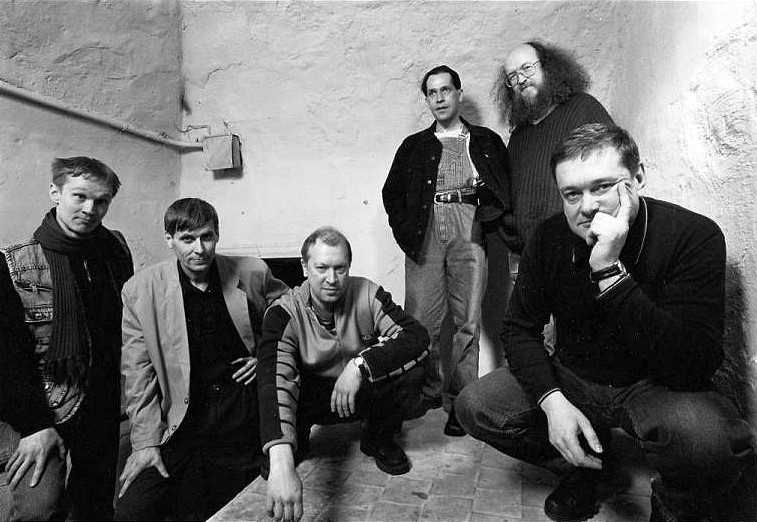

Фото —

Иван Балашов

Listener стартовали в далеком 2002-м как хип-хоп-проект Дэна Смита. Со временем звучание ужесточилось до такой степени, что Смита позвали записывать гостевой вокал для металкорщиков The Chariot, а сама группа выступала на разогреве у The Dillinger Escape Plan на недавно прошедших в России концертах.

Инструментал у Listener довольно агрессивный, отдаёт кантри-мотивами, а безумные участники делают каждую песню не слёзным рассказом о несчастной любви, а эмоциональной декларацией лучшего друга в баре под очередную пинту пива.

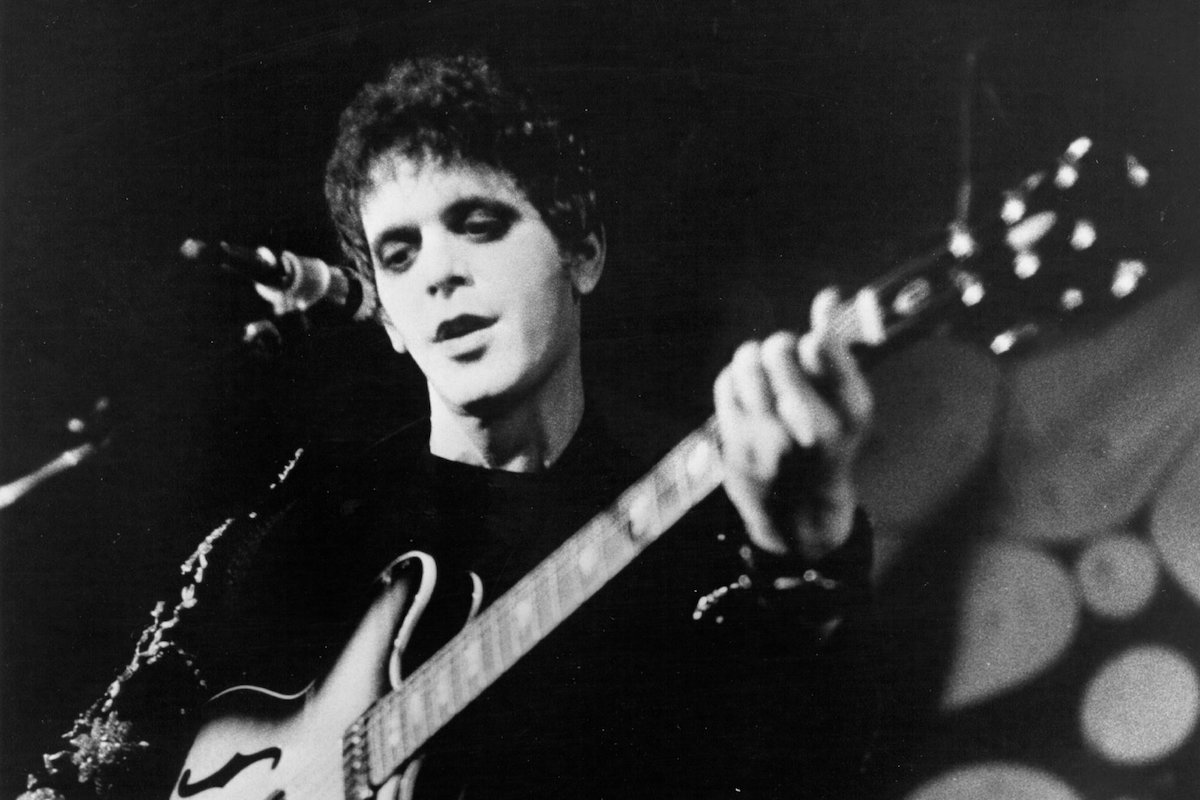

Лу Рид

Фото —

The Daily Beast

→

Лу Рид и его группа The Velvet Underground в своё время вдохновили невероятное количество музыкантов и тем самым повлияли на развитие рока. Например, о сильном влиянии Лу Рида на своё творчество говорил Дэвид Боуи.

Лу был в составе The Velvet Underground с 1964 по 1970 год, а после ухода из группы начал сольную карьеру. Он принял участие в песне Tranquilize группы The Killers, записал вместе с Gorillaz песню Plastic Beach и даже выпустил совместный альбом с Metallica!

Конечно, он выпускал и собственные альбомы. Наиболее необычный и несомненно заслуживающий внимания — The Raven, записанный в жанре spoken word. Главное в нём то, что он основан на рассказах Эдгара Аллана По. Так что скачивайте все 36 (!) песен, закрывайте глаза и погружайтесь в атмосферу.

Hotel Books

Фото —

Егор Зорин

→

Hotel Books обязательно понравятся любителям концептуализма. Кемерон Смит – единственный бессменный участник группы и её лицо – знает в этом толк. Например, песни July и August объединяет один общий клип, а для песни Lose One Friend существует своего рода парная композиция — Lose All Friends.

«Люди приходят и люди уходят. Некоторые приходят навестить, а другие просто потусить. И это моя книга поэм», — объясняет Кемерон название группы. Однако «люди приходят и люди уходят» — это не только про жизнь Смита, но и про саму группу. В последнем туре Hotel Books, например, за инструментал отвечали участники металкор-группы Convictions.

Дискография Hotel Books насчитывает уже 4 альбома, поэтому каждый сможет найти для себя новую любимую песню среди всего их разнообразия.

ДК

Фото —

Сергей Бабенко

→

ДК – советская группа, созданная в 1980 году. Название ей дал Сергей Жариков – создатель, идеолог и руководитель группы. ДК не стеснялись экспериментировать со звучанием и жанрами. Они первопроходцы российской экспериментальной музыки, творившие не только в жанре spoken word, но и авангарде, психоделическом роке, арт-панке, блюз-роке и еще множестве интересных жанров.

В 1984 году на Жарикова завели уголовное дело, а его группе, соответственно, запретили любые публичные выступления. Несомненно, это серьёзно сказалось на популярности ДК среди широких масс. Но всё же в музыкальных кругах они были группой известной и даже оказали сильное влияние на творчество Егора Летова (как на Гражданскую оборону, так и на проект Коммунизм), а также на группу Сектор Газа.

Canadian Softball

Фото —

Jarrod-Alonge

→

Canadian Softball – это вымышленная группа комика и музыканта Джаррода Алонжа, известного своими пародиями на рокеров и рок-группы. В 2015 году он выпустил альбом Beating a Dead Horse, в записи которого «участвовали» семь различных групп. На самом деле все семь групп были выдуманы комиком. Каждая группа пародировала определённый жанр. Звучание Canadian Softball, в частности, напоминало об эмо-группах поздних 1990-х — ранних 2000-х.

Состояла эта группа из самого Алонжа, вокалиста и гитариста, бассиста Уилла Грини и барабанщика/бэк-вокалиста Энди Конвэя. В альбоме у этой группы была только одна песня: The Distance Between You and Me is Longer Than the Title of this Song. Как видите, даже её название носит пародийный характер.

Позднее группа представила еще несколько песен, а 28 июля обещает выпустить альбом. В общем, дела у пародийной выдуманной группы идут даже лучше, чем у некоторых реально существующих артистов.

Подтянуть английский язык помогает чтение в оригинале: так можно и словарный запас пополнить, и грамматику отработать. Однако часто возникает ситуация, когда все слова вроде и знакомы, но они как будто случайно оказались вместе. Вместе с руководителем онлайн-школы английского языка Wordika Вероникой Генераловой мы нашли самые необычные английские идиомы и разобрались, что они означают.

To be under the weather — Неважно себя чувствовать

Буквальный перевод: «быть под погодой».

Есть несколько версий происхождения выражения, но все они связаны с морем. В основе первой — особенности ведения бортового журнала: в нем капитан судна ежедневно отмечал погодные условия и состав команды корабля. Тех, кто не мог нести службу, записывали в специальную колонку. Во время шторма туда попадали и многочисленные страдальцы, сломленные морской болезнью. В ненастные дни эта секция часто переполнялась, поэтому моряков приходилось записывать в соседнюю колонку, в графу «Погода» (weather), то есть «under the weather».

Вторая версия связана с местом размещения больных моряков: во время качки всех, кому становилось плохо, отправляли «under the deck and away from the weather», то есть «под палубу, подальше от непогоды». Со временем из этой фразы выпали «палуба» и «подальше» — так появился современный вариант идиомы.

How did you know I was feeling so under the weather this evening? / Как ты узнал, что мне так нехорошо этим вечером?

Pot calling the kettle black — Кто бы говорил

Буквальный перевод: «горшок зовет котел черным (а сам не белее)».

Много лет назад люди готовили на открытом огне в чугунных горшках и медных котлах, после чего на них оставалась черная сажа. Медные котлы очищали и полировали после каждой готовки до блеска настолько, что стоящий рядом горшок отражался в нем, как в зеркале. Так и появилась идея о том, что горшок обвиняет чистый котел в нечистоплотности, хотя на самом деле именно он весь в саже.

Both game developers accuse each other for ripping their narratives: it’s like the pot calling the kettle black. / Оба разработчика игр обвиняют друг друга в плагиате сюжета, хотя чья бы корова мычала.

A hot potato — Щекотливый вопрос

Буквальный перевод: «горячая картошка».

Это выражение известно с середины XIX века и связано с другим фразеологизмом — «to drop like a hot potato» (стремительно от чего-либо избавиться). Ассоциация возникла на фоне того, как быстро из рук выскальзывает горячая картошка. Так словосочетание «hot potato» стало самостоятельно обозначать что-то не самое приятное, с чем хочется поскорее расправиться.

How will this crisis affect cinema production is a hot potato. / Как кризис повлияет на производство кино — щекотливый вопрос.

Cat got your tongue? — Язык проглотил?

Буквальный перевод: «кошка схватила тебя за язык?».

Изначально выражение звучало так: «Has the cat got your tongue?», позже его сократили до «Сat got your tongue». Точное происхождение выражения неизвестно, но есть несколько предположений.

Так, согласно первой версии, выражение пошло от плетки для наказания заключенных, которая по-английски называется «cat o’ nine tails» (буквально это можно перевести как «девятихвостая кошка»). Страх наказания этой плетью заставлял британских преступников держать язык за зубами.

Вторая версия отсылает к средневековой боязни ведьм и их верных спутников — черных котов. Поэтому, когда человек терял дар речи от удивления или шока, такую ситуацию сравнивали с проклятием, которое наложила чародейка явно не без помощи своего кота.

You could be more enthusiastic about the launch! Cat got your tongue? / Мог бы и порадоваться запуску проекта! Ты что, язык проглотил?

Neck of the woods — Трущобы, глушь

Буквальный перевод: «лесная шея».

Эта фраза характерна для американского английского. Впервые она появилась во времена колонистов, но варианты происхождения разнятся. По одной из версий, жители Нового Света старались максимально отстраниться от английских корней и использовали другие слова для обозначения привычных вещей: изначально «шеей» (а вернее, перешейком) называли узкий участок земли, окруженный с двух сторон водой. Американцы начали называть шеей еще и неширокую часть леса или пастбища, а позже и поселение, расположенное в такой местности.

Вторая версия связана с языком коренных американцев алгонкинов: их слово «naiack» означало «место» или «угол». Поселенцы могли перенять это выражение, но со временем его написание и произношение сблизилось с привычным англоязычным жителям Нового Света «neck».

Welcome to my neck of the woods. / Добро пожаловать в мою трущобу.

To go pear-shaped — Пойти наперекосяк

Буквальный перевод: «приобрести форму груши».

Одни лингвисты считают, что это выражение придумали пилоты Королевских военно-воздушных сил Великобритании в 1940-х годах: круги в воздухе — достаточно сложная фигура, поэтому часто вместо окружности у пилотов получалась груша. Другие полагают, что фразеологизм отсылает к Первой мировой войне: запуск воздушных шаров, использовавшихся в то время для наблюдения, шел наперекосяк, когда, надуваясь, они приобретали форму груши.

And when the main cast left, everything with the show went pear-shaped. / А когда основной актерский состав ушел, все в сериале пошло наперекосяк.

Blue in the face — До изнеможения

Буквальный перевод: «синее лицо».

Это выражение часто используется в описании разговоров и дискуссий. Фраза отсылает к ситуации, когда у непрерывно вещающего человека просто заканчивался воздух в легких и его лицо приобретало характерный синий оттенок.

She can talk about the history of feminism till she is blue in the face. / Она может говорить об истории феминизма до посинения.

Thick as thieves — Закадычные друзья

Буквальный перевод: «толстые, как воры».

Идиома появилась в начале XIX века и действительно имеет криминальное прошлое. В то время воры работали в бандах, и успех их планов зависел от уровня доверия внутри группировки, поэтому преступники знали друг о друге абсолютно все. Слово «thick» («толстый»), в данном случае означало «очень близкий», «тесно связанный». Изначально говорили «thick as two thieves», но позже числительное выпало, и получилось сегодняшнее выражение, которое означает близких друзей.

Hopper definitely knows Joyce’s whereabouts but he wouldn’t tell us anything — they are as thick as thieves. / Хоппер точно знает, где находится Джойс, но ничего не скажет: они закадычные друзья.

Wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole — Не приблизился бы и на километр

Буквальный перевод: «не стал бы трогать и баржевой палкой».

В XIX веке, когда многие баржи еще не могли плыть самостоятельно, люди использовали для их передвижения специальные толстые и длинные (около 3 м) палки или сучья. Они позволяли безбоязненно исследовать незнакомый или не очень презентабельный предмет, попадавшийся на пути следования, поэтому выражение стали использовать для обозначения чего-то особенно неприятного или опасного.

They don’t want any bad publicity, so they wouldn’t touch this influencer with a barge pole. / Им не нужны проблемы с репутацией, так что они и на километр не подойдут к этому блогеру.

Heart in one’s mouth — Сердце в пятки ушло

Буквальный перевод: «сердце во рту».

Считается, что впервые это выражение использовал Гомер в «Илиаде», чтобы передать чувство невероятного нервного напряжения. Древнегреческий поэт обратил внимание на ощущение, которое возникает в моменты страха и волнения: сердце бьется так часто, что вибрация начинает чувствоваться в горле.

When they told me my flight has been postponed, I had my heart in mouth. / Когда мне сказали, что мой рейс отложен, у меня сердце в пятки ушло.

Go bananas — Слететь с катушек

Буквальный перевод: «стать бананом».

Группа Little Big тут ни при чем. Историки и лингвисты полагают, что постарались студенты американских колледжей и обезьяны. Изначально существовал фразеологизм «go ape», который тоже означал сумасшествие и отсылал к образу обезьяны. Устойчивая ассоциация животных с их любимым лакомством в глазах американских студентов стала причиной изменения фразы.

Everybody went bananas when all the fitness clubs in the city opened again. / Все просто с катушек слетели, когда снова открылись все фитнес-клубы города.

Cool as a cucumber — Спокоен как удав

Буквальный перевод: «холодный, как огурец».

Даже в жару огурец обычно на несколько градусов холоднее воздуха — так и появилось сравнение хладнокровного человека, спокойного при любой ситуации, с плодом травянистого растения семейства тыквенных.

The passengers worried about possible speeding ticket, yet Victor was as cool as a cucumber. / Пассажиры переживали из-за возможного штрафа за превышение скорости, а Виктор все равно был спокоен как удав.

Опишите свое состояние одним словом. Игра «РБК Стиль».

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples