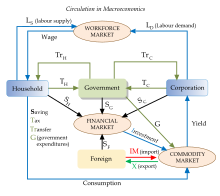

(Production and national income) Macroeconomics takes a big-picture view of the entire economy, including examining the roles of, and relationships between, corporations, governments and households, and the different types of markets, such as the financial market and the labour market. However, the use of natural resources and the generation of waste (like greenhouse gases) are often excluded in its models.

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and government spending to regulate an economy’s growth and stability.[1]

This includes regional, national, and global economies.[2][3]

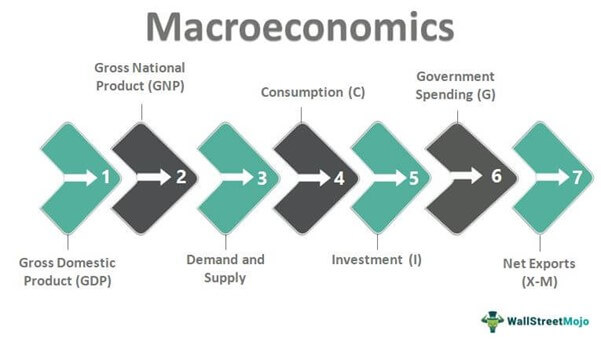

Macroeconomists study topics such as GDP (Gross Domestic Product), unemployment (including unemployment rates), national income, price indices, output, consumption, inflation, saving, investment, energy, international trade, and international finance.

Macroeconomics and microeconomics are the two most general fields in economics.[4] The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 17 has a target to enhance global macroeconomic stability through policy coordination and coherence as part of the 2030 Agenda.[5]

According to a 2018 assessment by economists Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, economic «evidence regarding the consequences of different macroeconomic policies is still highly imperfect and open to serious criticism.»[6]

Development[edit]

Origins[edit]

Macroeconomics descended from the once divided fields of business cycle theory and monetary theory.[7] The quantity theory of money was particularly influential prior to World War II. It took many forms, including the version based on the work of Irving Fisher:

In the typical view of the quantity theory, money velocity (V) and the quantity of goods produced (Q) would be constant, so any increase in money supply (M) would lead to a direct increase in price level (P). The quantity theory of money was a central part of the classical theory of the economy that prevailed in the early twentieth century.

Austrian School[edit]

Ludwig von Mises’s work Theory of Money and Credit, published in 1912, was one of the first books from the Austrian School to deal with macroeconomic topics.

Keynes and his followers[edit]

Macroeconomics, at least in its modern form,[8] began with the publication of General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money[7][9] written by John Maynard Keynes. When the Great Depression struck, classical economists had difficulty explaining how goods could go unsold and workers could be left unemployed. In classical theory, prices and wages would drop until the market cleared, and all goods and labor were sold. Keynes offered a new theory of economics that explained why markets might not clear, which would evolve (later in the 20th century) into a group of macroeconomic schools of thought known as Keynesian economics – also called Keynesianism or Keynesian theory.

In Keynes’ theory, the quantity theory broke down because people and businesses tend to hold on to their cash in tough economic times – a phenomenon he described in terms of liquidity preferences. Keynes also explained how the multiplier effect would magnify a small decrease in consumption or investment and cause declines throughout the economy. Keynes also noted the role uncertainty and animal spirits can play in the economy.[8]

The generation following Keynes combined the macroeconomics of the General Theory with neoclassical microeconomics to create the neoclassical synthesis. By the 1950s, most economists had accepted the synthesis view of the macroeconomy.[8] Economists like Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, James Tobin, and Robert Solow developed formal Keynesian models and contributed formal theories of consumption, investment, and money demand that fleshed out the Keynesian framework.[10]

Monetarism[edit]

Milton Friedman updated the quantity theory of money to include a role for money demand. He argued that the role of money in the economy was sufficient to explain the Great Depression, and that aggregate demand oriented explanations were not necessary. Friedman also argued that monetary policy was more effective than fiscal policy; however, Friedman doubted the government’s ability to «fine-tune» the economy with monetary policy. He generally favored a policy of steady growth in money supply instead of frequent intervention.[11]

Friedman also challenged the Phillips curve relationship between inflation and unemployment. Friedman and Edmund Phelps (who was not a monetarist) proposed an «augmented» version of the Phillips curve that excluded the possibility of a stable, long-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.[12] When the oil shocks of the 1970s created a high unemployment and high inflation, Friedman and Phelps were vindicated. Monetarism was particularly influential in the early 1980s. Monetarism fell out of favor when central banks found it difficult to target money supply instead of interest rates as monetarists recommended. Monetarism also became politically unpopular when the central banks created recessions in order to slow inflation.

New classical[edit]

New classical macroeconomics further challenged the Keynesian school. A central development in new classical thought came when Robert Lucas introduced rational expectations to macroeconomics. Prior to Lucas, economists had generally used adaptive expectations where agents were assumed to look at the recent past to make expectations about the future. Under rational expectations, agents are assumed to be more sophisticated. A consumer will not simply assume a 2% inflation rate just because that has been the average the past few years; they will look at current monetary policy and economic conditions to make an informed forecast. When new classical economists introduced rational expectations into their models, they showed that monetary policy could only have a limited impact.

Lucas also made an influential critique of Keynesian empirical models. He argued that forecasting models based on empirical relationships would keep producing the same predictions even as the underlying model generating the data changed. He advocated models based on fundamental economic theory that would, in principle, be structurally accurate as economies changed. Following Lucas’s critique, new classical economists, led by Edward C. Prescott and Finn E. Kydland, created real business cycle (RB C) models of the macro economy.[13]

RB C models were created by combining fundamental equations from neo-classical microeconomics. In order to generate macroeconomic fluctuations, RB C models explained recessions and unemployment with changes in technology instead of changes in the markets for goods or money. Critics of RB C models argue that money clearly plays an important role in the economy, and the idea that technological regress can explain recent recessions is implausible.[13] However, technological shocks are only the more prominent of a myriad of possible shocks to the system that can be modeled. Despite questions about the theory behind RB C models, they have clearly been influential in economic methodology.[14]

New Keynesian response[edit]

New Keynesian economists responded to the new classical school by adopting rational expectations and focusing on developing micro-founded models that are immune to the Lucas critique. Stanley Fischer and John B. Taylor produced early work in this area by showing that monetary policy could be effective even in models with rational expectations when contracts locked in wages for workers. Other new Keynesian economists, including Olivier Blanchard, Julio Rotemberg, Greg Mankiw, David Romer, and Michael Woodford, expanded on this work and demonstrated other cases where inflexible prices and wages led to monetary and fiscal policy having real effects.

Like classical models, new classical models had assumed that prices would be able to adjust perfectly and monetary policy would only lead to price changes. New Keynesian models investigated sources of sticky prices and wages due to imperfect competition,[15] which would not adjust, allowing monetary policy to impact quantities instead of prices.

By the late 1990s, economists had reached a rough consensus. The nominal rigidity of new Keynesian theory was combined with rational expectations and the RBC methodology to produce dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models. The fusion of elements from different schools of thought has been dubbed the new neoclassical synthesis. These models are now used by many central banks and are a core part of contemporary macroeconomics.[16]

New Keynesian economics, which developed partly in response to new classical economics, strives to provide microeconomic foundations to Keynesian economics by showing how imperfect markets can justify demand management.

Macroeconomic models[edit]

Aggregate demand–aggregate supply[edit]

A traditional AS–AD diagram showing shift in AD and the AS curve becoming inelastic beyond potential output

The AD-AS model has become the standard textbook model for explaining the macroeconomy.[17] This model shows the price level and level of real output given the equilibrium in aggregate demand and aggregate supply. The aggregate demand curve’s downward slope means that more output is demanded at lower price levels.[18] The downward slope is the result of three effects: the Pigou or real balance effect, which states that as real prices fall, real wealth increases, resulting in higher consumer demand of goods; the Keynes or interest rate effect, which states that as prices fall, the demand for money decreases, causing interest rates to decline and borrowing for investment and consumption to increase; and the net export effect, which states that as prices rise, domestic goods become comparatively more expensive to foreign consumers, leading to a decline in exports.[18]

In the conventional Keynesian use of the AS-AD model, the aggregate supply curve is horizontal at low levels of output and becomes inelastic near the point of potential output, which corresponds with full employment.[17] Since the economy cannot produce beyond the potential output, any AD expansion will lead to higher price levels instead of higher output.

The AD–AS diagram can model a variety of macroeconomic phenomena, including inflation. Changes in the non-price level factors or determinants cause changes in aggregate demand and shifts of the entire aggregate demand (AD) curve. When demand for goods exceeds supply, there is an inflationary gap where demand-pull inflation occurs and the AD curve shifts upward to a higher price level. When the economy faces higher costs, cost-push inflation occurs and the AS curve shifts upward to higher price levels.[19] The AS–AD diagram is also widely used as an instructive tool to model the effects of various macroeconomic policies.[20]

IS-LM[edit]

In this example of an IS/LM chart, the IS curve moves to the right, causing higher interest rates (i) and expansion in the «real» economy (real GDP, or Y).

The IS–LM model gives the underpinnings of aggregate demand (itself discussed above). It answers the question «At any given price level, what is the quantity of goods demanded?». This model shows what combination of interest rates and output will ensure equilibrium in both the goods and money markets.[21] The goods market is modeled as giving equality between investment and public and private saving (IS), and the money market is modeled as giving equilibrium between the money supply and liquidity preference.[22]

The IS curve consists of the points (combinations of income and interest rate) where investment, given the interest rate, is equal to public and private saving, given output[23] The IS curve is downward sloping because output and the interest rate have an inverse relationship in the goods market: as output increases, more income is saved, which means interest rates must be lower to spur enough investment to match saving.[23]

The LM curve is upward sloping because the interest rate and output have a positive relationship in the money market: as income (identically equal to output) increases, the demand for money increases, resulting in a rise in the interest rate in order to just offset the incipient rise in money demand.[24]

The IS-LM model is often used to demonstrate the effects of monetary and fiscal policy.[21] Textbooks frequently use the IS-LM model, but it does not feature the complexities of most modern macroeconomic models.[21] Nevertheless, these models still feature similar relationships to those in IS-LM.[21]

Growth models[edit]

The neoclassical growth model of Robert Solow has become a common textbook model for explaining economic growth in the long-run.[25] The model begins with a production function where national output is the product of two inputs: capital and labor. The Solow model assumes that labor and capital are used at constant rates without the fluctuations in unemployment and capital utilization commonly seen in business cycles.[26]

An increase in output, or economic growth, can only occur because of an increase in the capital stock, a larger population, or technological advancements that lead to higher productivity (total factor productivity). An increase in the savings rate leads to a temporary increase as the economy creates more capital, which adds to output. However, eventually the depreciation rate will limit the expansion of capital: savings will be used up replacing depreciated capital, and no savings will remain to pay for an additional expansion in capital. Solow’s model suggests that economic growth in terms of output per capita depends solely on technological advances that enhance productivity.[27]

In the 1980s and 1990s endogenous growth theory arose to challenge neoclassical growth theory. This group of models explains economic growth through other factors, such as increasing returns to scale for capital and learning-by-doing, that are endogenously determined instead of the exogenous technological improvement used to explain growth in Solow’s model.[28] The quantity theory by Russian economist Vladimir Pokrovskii explains growth as a consequence of the dynamics of three factors, among them capital service as one of independent production factors in line with labour and capital.[29] Capital service as production factor was interpreted by Ayres and Warr as useful work of production equipment, which makes it possible to reproduce historical rates of economic growth with considerable precision [29].[30] [31] and without recourse to exogenous and unexplained technological progress, thereby overcoming the major flaw of the Solow theory of economic growth.

Humanity’s economic system as a subsystem of the global environment[edit]

Natural resources flow through the economy and end up as waste and pollution.

In the macroeconomic models in ecological economics, the economic system is a subsystem of the environment. In this model, the circular flow of income diagram is replaced in ecological economics by a more complex flow diagram reflecting the input of solar energy, which sustains natural inputs and environmental services which are then used as units of production. Once consumed, natural inputs pass out of the economy as pollution and waste. The potential of an environment to provide services and materials is referred to as an «environment’s source function», and this function is depleted as resources are consumed or pollution contaminates the resources. The «sink function» describes an environment’s ability to absorb and render harmless waste and pollution: when waste output exceeds the limit of the sink function, long-term damage occurs.[32]: 8 Some persistent pollutants, such as some organic pollutants and nuclear waste are absorbed very slowly or not at all; ecological economists emphasize minimizing «cumulative pollutants».[32]: 28 Pollutants affect human health and the health of the ecosystem.

Basic macroeconomic concepts[edit]

Macroeconomics encompasses a variety of concepts and variables, but there are three central topics for macroeconomic research.[33] Macroeconomic theories usually relate the phenomena of output, unemployment, and inflation. Outside of macroeconomic theory, these topics are also important to all economic agents including workers, consumers, and producers.

Output and income[edit]

National output is the total amount of everything a country produces in a given period of time. Everything that is produced and sold generates an equal amount of income. The total output of the economy is measured GDP per person. The output and income are usually considered equivalent and the two terms are often used interchangeably, output changes into income. Output can be measured or it can be viewed from the production side and measured as the total value of final goods and services or the sum of all value added in the economy.[34]

Macroeconomic output is usually measured by gross domestic product (GDP) or one of the other national accounts. Economists interested in long-run increases in output, study economic growth. Advances in technology, accumulation of machinery and other capital, and better education and human capital, are all factors that lead to increase economic output over time. However, output does not always increase consistently over time. Business cycles can cause short-term drops in output called recessions. Economists look for macroeconomic policies that prevent economies from slipping into recessions, and that lead to faster long-term growth.

Unemployment[edit]

A chart using US data showing the relationship between economic growth and unemployment expressed by Okun’s law. The relationship demonstrates cyclical unemployment. Economic growth leads to a lower unemployment rate.

The amount of unemployment in an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, i.e. the percentage of workers without jobs in the labor force. The unemployment rate in the labor force only includes workers actively looking for jobs. People who are retired, pursuing education, or discouraged from seeking work by a lack of job prospects are excluded.

Unemployment can be generally broken down into several types that are related to different causes.

- Classical unemployment theory suggests that unemployment occurs when wages are too high for employers to be willing to hire more workers.[35] Other more modern economic theories[which?] suggest that increased wages actually decrease unemployment by creating more consumer demand. According to these more recent theories, unemployment results from reduced demand for the goods and services produced through labor and suggest that only in markets where profit margins are very low, and in which the market will not bear a price increase of product or service, will higher wages result in unemployment.

- Consistent with classical unemployment theory, frictional unemployment occurs when appropriate job vacancies exist for a worker, but the length of time needed to search for and find the job leads to a period of unemployment.[36]

- Structural unemployment covers a variety of possible causes of unemployment including a mismatch between workers’ skills and the skills required for open jobs.[37] Large amounts of structural unemployment commonly occur when an economy shifts to focus on new industries and workers find their previous set of skills are no longer in demand. Structural unemployment is similar to frictional unemployment as both reflect the problem of matching workers with job vacancies, but structural unemployment also covers the time needed to acquire new skills in addition to the short-term search process.[38]

- While some types of unemployment may occur regardless of the condition of the economy, cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun’s law represents the empirical relationship between unemployment and economic growth.[39] The original version of Okun’s law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[40]

Inflation and deflation[edit]

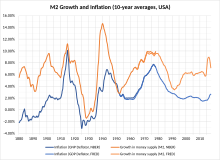

Changes in the ten-year moving averages of price level and growth in money supply (using the measure of M2, the supply of hard currency and money held in most types of bank accounts) in the US from 1880 to 2016. Over the long run, the two series show a close relationship.

A general price increase across the entire economy is called inflation. When prices decrease, there is deflation. Economists measure these changes in prices with price indexes. Inflation can occur when an economy becomes overheated and grows too quickly. Similarly, a declining economy can lead to deflation.

Central bankers, who manage a country’s money supply, try to avoid changes in price level by using monetary policy. Raising interest rates or reducing the supply of money in an economy is posited to reduce inflation. Inflation can lead to increased uncertainty and other negative consequences. Deflation can lower economic output. Central bankers try to stabilize prices to protect economies from the negative consequences of price changes.

Changes in price level may be the result of several factors. The quantity theory of money holds that changes in price level are directly related to changes in the money supply. Most economists believe that this relationship explains long-run changes in the price level.[41] Short-run fluctuations may also be related to monetary factors, but changes in aggregate demand and aggregate supply can also influence price level. For example, a decrease in demand due to a recession can lead to lower price levels and deflation. A negative supply shock, such as an oil crisis, lowers aggregate supply and can cause inflation.

Macroeconomic policy[edit]

Macroeconomic policy is usually implemented through two sets of tools: fiscal and monetary policy. Both forms of policy are used to stabilize the economy, which can mean boosting the economy to the level of GDP consistent with full employment.[42] Macroeconomic policy focuses on limiting the effects of the business cycle to achieve the economic goals of price stability, full employment, and growth.[43]

According to a 2018 assessment by economists Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, economic «evidence regarding the consequences of different macroeconomic policies is still highly imperfect and open to serious criticism.»[6] Nakamura and Steinsson write that macroeconomics struggles with long-term predictions, which is a result of the high complexity of the systems it studies.[6]

Monetary policy[edit]

Central banks implement monetary policy by controlling the money supply through several mechanisms. Typically, central banks take action by issuing money to buy bonds (or other assets), which boosts the supply of money and lowers interest rates, or, in the case of contractionary monetary policy, banks sell bonds and take money out of circulation. Usually policy is not implemented by directly targeting the supply of money.

Central banks continuously shift the money supply to maintain a targeted fixed interest rate. Some of them allow the interest rate to fluctuate and focus on targeting inflation rates instead. Central banks generally try to achieve high output without letting loose monetary policy that create large amounts of inflation.

Conventional monetary policy can be ineffective in situations such as a liquidity trap. When interest rates and inflation are near zero, the central bank cannot loosen monetary policy through conventional means.

An example of intervention strategy under different conditions

Central banks can use unconventional monetary policy such as quantitative easing to help increase output. Instead of buying government bonds, central banks can implement quantitative easing by buying not only government bonds, but also other assets such as corporate bonds, stocks, and other securities. This allows lower interest rates for a broader class of assets beyond government bonds. In another example of unconventional monetary policy, the United States Federal Reserve recently made an attempt at such a policy with Operation Twist. Unable to lower current interest rates, the Federal Reserve lowered long-term interest rates by buying long-term bonds and selling short-term bonds to create a flat yield curve.

Fiscal policy[edit]

Fiscal policy is the use of government’s revenue and expenditure as instruments to influence the economy. Examples of such tools are expenditure, taxes, debt.

For example, if the economy is producing less than potential output, government spending can be used to employ idle resources and boost output. Government spending does not have to make up for the entire output gap. There is a multiplier effect that boosts the impact of government spending. For instance, when the government pays for a bridge, the project not only adds the value of the bridge to output, but also allows the bridge workers to increase their consumption and investment, which helps to close the output gap.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by crowding out. When the government takes on spending projects, it limits the amount of resources available for the private sector to use. Crowding out occurs when government spending simply replaces private sector output instead of adding additional output to the economy. Crowding out also occurs when government spending raises interest rates, which limits investment. Defenders of fiscal stimulus argue that crowding out is not a concern when the economy is depressed, plenty of resources are left idle, and interest rates are low.[44][45]

Fiscal policy can be implemented through automatic stabilizers. Automatic stabilizers do not suffer from the policy lags of discretionary fiscal policy. Automatic stabilizers use conventional fiscal mechanisms but take effect as soon as the economy takes a downturn: spending on unemployment benefits automatically increases when unemployment rises and, in a progressive income tax system, the effective tax rate automatically falls when incomes decline.

Comparison[edit]

Economists usually favor monetary over fiscal policy because it has two major advantages. First, monetary policy is generally implemented by independent central banks instead of the political institutions that control fiscal policy. Independent central banks are less likely to make decisions based on political motives.[42] Second, monetary policy suffers shorter inside lags and outside lags than fiscal policy. Additionally, central banks are able to make quick decisions with rapid implementation. Whereas fiscal policy will most likely move slowly through government bureaucracy and take longer to fully implement into the economy.[42]

See also[edit]

- Business cycle accounting

- Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium

- Economic development

- Growth accounting

Notes[edit]

- ^

Samuelson, Robert (2020), «Goodbye, readers, and good luck — you’ll need it», The Washington Post

This article was an opinion piece expressing despondency in the field shortly before his retirement, but it’s still a good summary. - ^ O’Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003), Economics: Principles in Action, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall, p. 57, ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Steve Williamson, Notes on Macroeconomic Theory, 1999

- ^ Blaug, Mark (1985), Economic theory in retrospect, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-31644-6

- ^ «Goal 17 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs». sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b c Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jón (2018). «Identification in Macroeconomics». Journal of Economic Perspectives. 32 (3): 59–86. doi:10.1257/jep.32.3.59. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 44180952.

- ^ a b Dimand (2008).

- ^ a b c Blanchard (2011), 580.

- ^ Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2005). Modern Macroeconomics – Its origins, development and current state. Edward Elgar. ISBN 1-84542-208-2.

- ^ Blanchard (2011), 581.

- ^ Blanchard (2011), 582–83.

- ^ «Phillips Curve: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics | Library of Economics and Liberty». www.econlib.org. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ^ a b Blanchard (2011), 587.

- ^ Kariappa Bheemaiah, The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory (Dordrecht NL: Apress/Springer Nature, 2017), 169-70. ISBN 1484226747, 9781484226742

- ^ The role of imperfect competition in new Keynesian economics, Chapter 4 of Surfing Economics by Huw Dixon

- ^ Blanchard (2011), 590.

- ^ a b Healey 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b Healey 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Healey 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Colander 1995, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d Durlauf & Hester 2008.

- ^ Peston 2002, pp. 386–87.

- ^ a b Peston 2002, p. 387.

- ^ Peston 2002, pp. 387–88.

- ^ Banton, Caroline. «The Neoclassical Growth Theory Explained». Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- ^ Solow 2002, pp. 518–19.

- ^ Solow 2002, p. 519.

- ^ Blaug 2002, pp. 202–03.

- ^ a b Pokrovski, V.N. (2003). Energy in the theory of production. Energy 28, 769-788.

- ^ Pokrovski, V.N. (2007) Productive energy in the US economy, Energy 32 (5) 816-822.

- ^ Pokrovskii, Vladimir (2021). «Social resources in the theory of economic growth». The Complex Systems (3): 32–43.

- ^ a b Harris J. (2006). Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ Blanchard (2011), 32.

- ^ Blanchard (2011), 22.

- ^ Pettinger, Tejvan. «Involuntary unemployment». Economics Help. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- ^ Dwivedi, 443.

- ^ «Freeman (2008)».

- ^ Dwivedi, 444–45.

- ^ Dwivedi, 445–46.

- ^ «Neely, Christopher J. «Okun’s Law: Output and Unemployment. Economic Synopses. Number 4. 2010″.

- ^ Mankiw 2014, p. 634.

- ^ a b c Mayer, 495.

- ^ «AP Macroeconomics Review».

- ^ Ye, Fred Y. (2017). Scientific Metrics: Towards Analytical and Quantitative Sciences. Springer. ISBN 978-981-10-5936-0.

- ^ Arestis, Philip; Sawyer, Malcolm (2003). «Reinventing fiscal policy» (PDF). Levy Economics Institute of Bard College (Working Paper, No. 381). Retrieved 7 December 2018.

References[edit]

- Blanchard, Olivier (2000). Macroeconomics. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-013306-9.

- Blanchard, Olivier. (2009). «The State of Macro.» Annual Review of Economics 1(1): 209-228.

- Blanchard, Olivier (2011). Macroeconomics Updated (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-215986-9.

- Blaug, Mark (1986), Great Economists before Keynes, Brighton: Wheatsheaf.

- Blaug, Mark (2002). «Endogenous growth theory». In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Boettke, Peter (2001). Calculation and Coordination: Essays on Socialism and Transitional Political Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77109-2.

- Bouman, John: Principles of Macroeconomics – free fully comprehensive Principles of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics texts. Columbia, Maryland, 2011

- Dimand, Robert W. (2008). «Macroeconomics, origins and history of». In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 236–44. doi:10.1057/9780230226203.1009. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5 http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_M000370.

- Durlauf, Steven N.; Hester, Donald D. (2008). «IS–LM». In Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 585–91. doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0855. ISBN 978-0-333-78676-5. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Dwivedi, D.N. (2001). Macroeconomics: theory and policy. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-058841-7.

- Friedman, Milton (1953). Essays in Positive Economics. London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-26403-5.

- Haberler, Gottfried (1937). Prosperity and depression. League of Nations.

- Leijonhufvud, Axel The Wicksell Connection: Variation on a Theme. UCLA. November, 1979.

- Healey, Nigel M. (2002). «AD-AS model». In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Heijdra, Ben J.; van der Ploeg, Frederick (2002). Foundations of Modern Macroeconomics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-877617-8.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2014). Principles of Economics. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-15604-3.

- Mises, Ludwig Von (1912). Theory of Money and Credit. Yale University Press.

- Mayer, Thomas (2002). «Monetary policy: role of». In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 495–99. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Mishkin, Frederic S. (2004). The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets. Boston: Addison-Wesley. p. 517. ISBN 9780321122353.

- Nakamura, Emi and Jón Steinsson. (2018). «Identification in Macroeconomics.» Journal of Economic Perspectives 32(3): 59-86.

- Peston, Maurice (2002). «IS-LM model: closed economy». In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Edward Elgar. ISBN 9781840643879.

- Pokrovskii, Vladimir (2018). Econodynamics. The Theory of Social Production. Springer, Dordrecht-Heidelberg-London-New York.

- Reed, Jacob (2016). AP Economics Review, Macroeconomics.

- Solow, Robert (2002). «Neoclassical growth model». In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard (eds.). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1840643870.

- Snowdon, Brian, and Howard R. Vane, ed. (2002). An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics, Description & scroll to Contents-preview links.

- Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2005). Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development And Current State. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1845421809.

- Gärtner, Manfred (2006). Macroeconomics. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-0-273-70460-7.

- Warsh, David (2006). Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05996-0.

- Levi, Maurice (2014). The Macroeconomic Environment of Business (Core Concepts and Curious Connections). New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-4304-34-4.

What Is Macroeconomics?

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that studies how an overall economy—the markets, businesses, consumers, and governments—behave. Macroeconomics examines economy-wide phenomena such as inflation, price levels, rate of economic growth, national income, gross domestic product (GDP), and changes in unemployment.

Some of the key questions addressed by macroeconomics include: What causes unemployment? What causes inflation? What creates or stimulates economic growth? Macroeconomics attempts to measure how well an economy is performing, understand what forces drive it, and project how performance can improve.

Key Takeaways

- Macroeconomics is the branch of economics that deals with the structure, performance, behavior, and decision-making of the whole, or aggregate, economy.

- The two main areas of macroeconomic research are long-term economic growth and shorter-term business cycles.

- Macroeconomics in its modern form is often defined as starting with John Maynard Keynes and his theories about market behavior and governmental policies in the 1930s; several schools of thought have developed since.

- In contrast to macroeconomics, microeconomics is more focused on the influences on and choices made by individual actors in the economy (people, companies, industries, etc.).

Macroeconomics

Understanding Macroeconomics

As the term implies, macroeconomics is a field of study that analyzes an economy through a wide lens. This includes looking at variables like unemployment, GDP, and inflation. In addition, macroeconomists develop models explaining the relationships between these factors.

These models, and the forecasts they produce, are used by government entities to aid in constructing and evaluating economic, monetary, and fiscal policy. Businesses use the models to set strategies in domestic and global markets, and investors use them to predict and plan for movements in various asset classes.

Properly applied, economic theories can illuminate how economies function and the long-term consequences of particular policies and decisions. Macroeconomic theory can also help individual businesses and investors make better decisions through a more thorough understanding of the effects of broad economic trends and policies on their own industries.

History of Macroeconomics

While the term «macroeconomics» is not all that old (going back to the 1940s), many of macroeconomics’s core concepts have been the study focus for much longer. Topics like unemployment, prices, growth, and trade have concerned economists since the beginning of the discipline in the 1700s. Elements of earlier work from Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill addressed issues that would now be recognized as the domain of macroeconomics.

In its modern form, macroeconomics is often defined as starting with John Maynard Keynes and his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936. Keynes explained the fallout from the Great Depression when goods remained unsold, and workers were unemployed.

Throughout the 20th century, Keynesian economics, as Keynes’ theories became known, diverged into several other schools of thought.

Before the popularization of Keynes’ theories, economists did not generally differentiate between micro- and macroeconomics. The same microeconomic laws of supply and demand that operate in individual goods markets were understood to interact between individual markets to bring the economy into a general equilibrium, as described by Leon Walras.

The link between goods markets and large-scale financial variables such as price levels and interest rates was explained through the unique role that money plays in the economy as a medium of exchange by economists such as Knut Wicksell, Irving Fisher, and Ludwig von Mises.

Macroeconomics vs. Microeconomics

Macroeconomics differs from microeconomics, which focuses on smaller factors that affect choices made by individuals and companies. Factors studied in both microeconomics and macroeconomics typically influence one another.

A key distinction between micro- and macroeconomics is that macroeconomic aggregates can sometimes behave in very different ways or even the opposite of similar microeconomic variables. For example, Keynes referenced the so-called Paradox of Thrift, which argues that individuals save money to build wealth (micro). However, when everyone tries to increase their savings at once, it can contribute to a slowdown in the economy and less wealth in the aggregate (macro). This is because there would be a reduction in spending, affecting business revenues and lowering worker pay.

Meanwhile, microeconomics looks at economic tendencies, or what can happen when individuals make certain choices. Individuals are typically classified into subgroups, such as buyers, sellers, and business owners. These actors interact with each other according to the laws of supply and demand for resources, using money and interest rates as pricing mechanisms for coordination.

Limits of Macroeconomics

It is also important to understand the limitations of economic theory. Theories are often created in a vacuum and lack specific real-world details like taxation, regulation, and transaction costs. The real world is also decidedly complicated and includes matters of social preference and conscience that do not lend themselves to mathematical analysis.

It is common in economics to find the phrase ceterus paribus, loosely translated as «all else being equal,» in economic theories and discussions. This is because there are so many variables that economists use this phrase as an assumption to focus on the relationships between the variables being discussed.

Even with the limits of economic theory, it is important and worthwhile to follow significant macroeconomic indicators like GDP, inflation, and unemployment. This is because the performance of companies, and by extension their stocks, is significantly influenced by the economic conditions in which the companies operate.

Likewise, it can be invaluable to understand which theories are in favor and influencing a particular government administration. The underlying economic principles of a government will say much about how that government will approach taxation, regulation, government spending, and similar policies. By better understanding economics and the ramifications of economic decisions, investors can get at least a glimpse of the probable future and act accordingly with confidence.

Macroeconomic Schools of Thought

The field of macroeconomics is organized into many different schools of thought, with differing views on how the markets and their participants operate.

Classical

Classical economists held that prices, wages, and rates are flexible and markets tend to clear unless prevented from doing so by government policy, building on Adam Smith’s original theories. The term “classical economists” is not actually a school of macroeconomic thought but a label applied first by Karl Marx and later by Keynes to denote previous economic thinkers with whom they respectively disagreed.

Keynesian

Keynesian economics was founded mainly based on the works of John Maynard Keynes and was the beginning of macroeconomics as a separate area of study from microeconomics. Keynesians focus on aggregate demand as the principal factor in issues like unemployment and the business cycle.

Keynesian economists believe that the business cycle can be managed by active government intervention through fiscal policy, where governments spend more in recessions to stimulate demand or spend less in expansions to decrease it. They also believe in monetary policy, where a central bank stimulates lending with lower rates or restricts it with higher ones.

Keynesian economists also believe that certain rigidities in the system, particularly sticky prices, prevent the proper clearing of supply and demand.

Monetarist

The Monetarist school is a branch of Keynesian economics credited mainly to the works of Milton Friedman. Working within and extending Keynesian models, Monetarists argue that monetary policy is generally a more effective and desirable policy tool to manage aggregate demand than fiscal policy. However, monetarists also acknowledge limits to monetary policy that make fine-tuning the economy ill-advised and instead tend to prefer adherence to policy rules that promote stable inflation rates.

New Classical

The New Classical school, along with the New Keynesians, is mainly built on integrating microeconomic foundations into macroeconomics to resolve the glaring theoretical contradictions between the two subjects.

The New Classical school emphasizes the importance of microeconomics and models based on that behavior. New Classical economists assume that all agents try to maximize their utility and have rational expectations, which they incorporate into macroeconomic models. New Classical economists believe that unemployment is largely voluntary and that discretionary fiscal policy destabilizes, while inflation can be controlled with monetary policy.

New Keynesian

The New Keynesian school also attempts to add microeconomic foundations to traditional Keynesian economic theories. While New Keynesians accept that households and firms operate based on rational expectations, they still maintain that there are a variety of market failures, including sticky prices and wages. Because of this «stickiness,» the government can improve macroeconomic conditions through fiscal and monetary policy.

Austrian

The Austrian School is an older school of economics that is seeing some resurgence in popularity. Austrian economic theories mainly apply to microeconomic phenomena. However, they, like the so-called classical economists, never strictly separated micro- and macroeconomics.

Austrian theories also have important implications for what is otherwise considered macroeconomic subjects. In particular, the Austrian business cycle theory explains broadly synchronized (macroeconomic) swings in economic activity across markets due to monetary policy and the role that money and banking play in linking (microeconomic) markets to each other and across time.

Macroeconomic Indicators

Macroeconomics is a rather broad field, but two specific research areas represent this discipline. The first area is the factors that determine long-term economic growth, or increases in the national income. The other involves the causes and consequences of short-term fluctuations in national income and employment, also known as the business cycle.

Economic Growth

Economic growth refers to an increase in aggregate production in an economy. Macroeconomists try to understand the factors that either promote or retard economic growth to support economic policies that will support development, progress, and rising living standards.

Economists can use many indicators to measure economic performance. These indicators fall into 10 categories:

- Gross Domestic Product indicators: Measure how much the economy produces

- Consumer Spending indicators: Measure how much capital consumers feed back into the economy

- Income and Savings indicators: Measures how much consumers make and save

- Industry Performance indicators: Measures GDP by industry

- International Trade and Investment indicators: Indicates the balance of payments between trade partners, how much is traded, and how much is invested internationally

- Prices and Inflation indicators: Indicate fluctuations in prices paid for goods and services and changes in currency purchasing power

- Investment in Fixed Assets indicators: Indicate how much capital is tied up in fixed assets

- Employment indicators: Shows employment by industry, state, county, and other areas

- Government indicators: Shows how much the government spends and receives

- Special indicators: All other economic indicators, such as distribution of personal income, global value chains, healthcare spending, small business well-being, and more

The Business Cycle

Superimposed over long-term macroeconomic growth trends, the levels and rates of change of significant macroeconomic variables such as employment and national output go through fluctuations. These fluctuations are called expansions, peaks, recessions, and troughs—they also occur in that order. When charted on a graph, these fluctuations show that businesses perform in cycles; thus, it is called the business cycle.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) measures the business cycle, which uses GDP and Gross National Income to date the cycle. The NBER is also the agency that declares the beginning and end of recessions and expansions.

How to Influence Macroeconomics

Because macroeconomics is such a broad area, positively influencing the economy is challenging and takes much longer than changing the individual behaviors within microeconomics. Therefore, economies need to have an entity dedicated to researching and identifying techniques that can influence large-scale changes.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve is the central bank with a mandate of promoting maximum employment and price stability. These two factors have been identified as essential to positively influencing change at the macroeconomic level.

To influence change, the Fed implements monetary policy through tools it has developed over the years, which work to affect its dual mandates. It has the following tools it can use:

- Federal Funds Rate Range: A target range set by the Fed that guides interest rates on overnight lending between depository institutions to boost short-term borrowing

- Open Market Operations: Purchase and sell securities on the open market to change the supply of reserves

- Discount Window and Rate: Lending to depository institutions to help banks manage liquidity

- Reserve Requirements: Maintaining a reserve to help banks maintain liquidity—reduced to 0% in 2020

- Interest on Reserve Balances: Encourages banks to hold reserves for liquidity and pays them interest for doing so

- Overnight Repurchase Agreement Facility: A supplementary tool used to help control the federal funds rate by selling securities and repurchasing them the next day at a more favorable rate

- Term Deposit Facility: Reserve deposits with a term, used to drain reserves from the banking system

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps: Established swap lines for central banks from select countries to improve liquidity conditions in the U.S. and participating countries’ central banks

- Foreign and International Monetary Authorities Repo Facility: A facility for institutions to enter repurchase agreements with the Fed to act as a backstop for liquidity

- Standing Overnight Repurchase Agreement Facility: A facility to encourage or discourage borrowing above a set rate, which helps to control the effective federal funds rate.

The Fed continuously updates the tools it uses to influence the economy, so it has a list of 14 other previously used tools it can implement again if needed.

What Is Macroeconomics in Economics?

Macroeconomics is the field of study of the way a overall economy behaves.

What are the 3 Major Concerns of Macroeconomics?

Three major macroeconomic concerns are the unemployment level, inflation, and economic growth.

Why Is Macroeconics Important?

Macroeconomics helps a government evaluate how an economy is performing and decide on actions it can take to increase or slow growth.

The Bottom Line

Macroeconomics is a field of study used to evaluate performance and develop actions that can positively affect an economy. Economists work to understand how specific factors and actions affect output, input, spending, consumption, inflation, and employment.

The study of economics began long ago, but the field didn’t start evolving into its current form until the 1700s. Macroeconomics now plays a large part in government and business decision-making.

Macroeconomics Definition

Macroeconomics is a ‘top-down approach; it gives a birds’ eye view of the economy. It focuses on aspects and phenomena that are important to the national economy and the world economy at large. The economy is impacted by GDP, growth, inflation, government spending, borrowings (fiscal policies), unemployment, and monetary policy.

The prices of products and services are interlinked, and macroeconomics studies the changes in these prices during economic ups and downs. Governments and institutions strategize policies based on this study. John Maynard Keynes is widely regarded as the pioneer in macroeconomics.

Table of contents

- Macroeconomics Definition

- Macroeconomics Explained

- Macroeconomics Theories

- Macroeconomics Objectives

- #1 – Reduce Unemployment

- #2 – Exchange Rate Stability

- #3 – Control Inflation

- #4 – Economic Development

- #5 – Balance of Payment Equilibrium

- #6 – Decrease Government Borrowings

- Macroeconomics Examples

- Scope and Importance

- Limitations of Macroeconomics

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Recommended Articles

- Macroeconomics is the economics discipline that concentrates on problems that affect the whole nation or region instead of an individual or household. It focuses on poverty, unemployment, inflation, national income, and economic growth.

- Governments and statutory bodies rely on this study. It is an essential parameter used in formulating fiscal and monetary policies.

- John Maynard Keynes is considered the father of macroeconomics. In 1936, he reshaped macroeconomics concepts.

- This economics discipline aims to facilitate sustainable economic development, stability of price, stable exchange rates, improved employment conditions, and balance of payment.

Macroeconomics Explained

Between micro and macroeconomics, the latter is more fascinating. It elucidates a global economic picture, a bird’s eye view. It is a ‘top-down’ approach. The study highlights how the output levels of different products and services are correlated. For example, if the price of fuel rises, then the price of goods like fruits, vegetables, and groceries will also rise. This is brought about by high transportation costs. Thus, this economics discipline aims to interlink different phenomena.

You are free to use this image on your website, templates, etc, Please provide us with an attribution linkArticle Link to be Hyperlinked

For eg:

Source: Macroeconomics (wallstreetmojo.com)

Historically, issues like trade, prices, output, unemployment, and growth have been discussed earlier by great economists like John Stuart Mill and Adam Smiths. However, it was the famous British economist John Maynard Keynes who combined all these economic factorsEconomic factors are external, environmental factors that influence business performance, such as interest rates, inflation, unemployment, and economic growth, among others.read more. As a result, the modern concept of macroeconomics was introduced. In 1936, Keynes published The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes’ modern economics contradicted the classic theory of the self-regulating market. After the 1929’s Great DepressionThe Great Depression refers to the long-standing financial crisis in the history of the modern world. It began in the United States on October 29, 1929, with the Wall Street Crash and lasted till 1939.read more, the US and Europe faced severe unemployment levels. Consequently, the aggregate output also fell drastically. Keynes studied the whole economy and correlated the behavior of different sectors and the economic factors to identify the reasons behind the fluctuation.

In macroeconomics, demand and supply refer to a broad range of aspects as both are aggregate by nature. Keynes favored demand-side economics, which impacts real GDPReal GDP can be described as an inflation-adjusted measure that reflects the value of services and goods produced in a single year by an economy, expressed in the prices of the base year, and is also known as «constant dollar GDP» or «inflation corrected GDP.»read more by increasing aggregate demandAggregate Demand is the overall demand for all the goods and the services in a country and is expressed as the total amount of money which is exchanged for such goods and services. It is a relationship between all the things which are bought within the country with their prices.read more. This involves improving income levels, stabilizing unemployment, and checking government spending. The aim was to boost the spending ability of people. Supply-side economics tries to impact real GDP by increasing aggregate supplyAggregate Supply is the projected supply that a business calculates based on the existing market conditions. Various factors such as changing economic trend are considered before calculating the aggregate supply.read more. This includes adjusted tax rates, deregulation, infrastructure support, privatization, and educational reforms.

Macroeconomics Theories

Macroeconomics focus on the following concepts.

- Theory of General Price Level: The prices of products and services are interlinked; economists study the changes in these prices during the economic ups and downs.

- Theory of National Income: The country’s budgeting, income, and expenditure impacts the nation’s overall growth. This measure aims to facilitate economic equality in society.

- Economic Growth and Development: The nation’s gross domestic product and per capita incomeThe per capita income formula depicts the average income of a region computed by dividing the total income of that area by the total population of the region. It is used to figure out the average income of a city, provision, state, country, etc.read more are development indicators.

- Theory of Employment: It is equally important to determine the unemployment level of a nation. Unemployment affects a nation’s income, consumption, demand, supply, and GDPGDP or Gross Domestic Product refers to the monetary measurement of the overall market value of the final output produced within a country over a period.read more.

- Theory of International Trade: Countries are highly affected by cross-border selling and purchase. As trade is necessary for improving economic conditions, the stability of exchange rates is essential. Preferably, the barriers for import and export should also be minimal.

- Theory of Money: The central bank policies control monetary circulation. Therefore, the economists give due consideration to central bank policies and their consequences.

Macroeconomics Objectives

In 1929, the US and apparently the whole world faced a great economic depression. Most economists failed to interpret this downfall. Following are the objectives of the macroeconomics theories:

#1 – Reduce Unemployment

Macroeconomics highlights how consumer demand impacts employment levels. A fall in demand causes employee layoffs. Therefore, measures increasing demand improve the employment conditions of a nation.

#2 – Exchange Rate Stability

Exchange rate fluctuations greatly impact the cross-border selling of goods and services. Favorable export and import duties can promote economic growthEconomic growth refers to an increase in the aggregated production and market value of economic commodities and services in an economy over a specific period.read more.

#3 – Control Inflation

A macroeconomic analysis identifies inflation. It further highlights measures that can reduce the adverse impact of inflation.

#4 – Economic Development

We have often read about business cycleThe business cycle refers to the alternating phases of economic growth and decline.read more fluctuations; the economy is dynamic. This is why economists, governments, and statutory bodies try to anticipate fluctuations. They plan based on the predictions. Therefore, despite unavoidable changes, economic growth can be ensured by making policies diligently.

#5 – Balance of Payment Equilibrium

International tradeInternational Trade refers to the trading or exchange of goods and or services across international borders. read more activities are essential for a nation’s development. This is why economists match export receipts to import payments. They identify a surplus or deficit. If import exceeds export, the surplus is termed as the balance of paymentThe formula for Balance of Payment is a summation of the current account, the capital account, and the financial account balances. The term balance of payments refers to the recording of all payments and obligations pertaining to imports from foreign countries vis-à-vis all payments and obligations pertaining to exports to foreign countries. It is the accounting of all the financial inflows and outflows of a nation.read more.

#6 – Decrease Government Borrowings

Governments borrow funds from other countries to fulfill short-term and long-term requirements or to repay previous loans. However, excessive borrowings can negatively impact a nation’s economy. Therefore, checking government borrowings is a vital part of this economics discipline.

Macroeconomics Examples

Let us discuss an example of macroeconomic analysis. The actual gross domestic product of Puerto Rico decreased by 2.4% in 2018. However, in 2019, GDP went up by 0.3% due to a 0.7% increase in exports. Also, a 9.1% decline in imports subsided the effects of reduced consumer and government spending. The credit for this goes to the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

Moreover, in 2019, the government reduced its expenditure on disaster recovery activities by 11.4%. This was possible because major damage repair of the power grid was accomplished in 2018 itself. Further, consumer spending in 2019 fell by 0.5%, and durable goods sales fell by 3.6%. This was caused by the 2018 reduction in compensation offered by the government and insurance companies.

United States Current Account deficitCurrent Account Deficit refers to a scenario when the country’s total value of imported goods & services surpasses the value of exported ones. Generally, it is the outcome of high expenditure on imports compared to the money spent on exports. read more is another example. They simply consume more than they earn. But how does the US finance this spending then? The government borrows money by issuing sovereign debtSovereign debt is the money borrowed by a country’s central government, primarily achieved by selling government bonds and securities. Treasury notes, bonds, and bills are some examples of sovereign debt issued by the United States.read more. Thus, the US runs a Capital Account Surplus.

Scope and Importance

The scope of macroeconomics is described below.

- Curtail the Impact of Recession or Inflation: Though the economic cycles cannot be avoided, their impact can be reduced significantly by implementing macroeconomic policies.

- Economic Problem Solving: Macroeconomic research and analysis identify the root cause behind a country’s economic crisis. It further facilitates the development of a problem-solving mechanism.

- Sustainable Economic Growth: The study helps deal with various macro-level issues like inflation, unemployment, and price level fluctuations.

- Policy Formation: The government and the statutory bodies make use of macroeconomic analysis for devising fiscal policiesFiscal policy refers to government measures utilizing tax revenue and expenditure as a tool to attain economic objectives. read more and monetary policiesMonetary policy refers to the steps taken by a country’s central bank to control the money supply for economic stability. For example, policymakers manipulate money circulation for increasing employment, GDP, price stability by using tools such as interest rates, reserves, bonds, etc.read more. These are reforms for correcting the economy.

- Social Welfare: The study also facilitates proper resource allocation to ensure economic equality.

- Business Cycle Analysis: With the regressive study of macroeconomic conditions, economists can interpret business cycle fluctuations. As a result, necessary steps are taken to reduce the impact of economic adversities.

Limitations of Macroeconomics

Macroeconomic analysis may go wrong since it emphasizes future predictions based on past incidents. In reality, things may not fall in the same way. Moreover, a particular situation can result from multiple economic changes, which require an expert’s knowledge and efforts.

There are numerous theories for conducting such an analysis; however, these theories ignore the practical aspects like government regulations and taxation. Further, it is a complex and specialized stream that requires a high level of skill and learning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the tools of macroeconomics?

Macroeconomists analyze a nation’s economic growth and business cycle fluctuations. They aid governments and business entities in decision-making. To control and stabilize macroeconomic changes, governments use fiscal policy measures. This involves increasing or decreasing government spending and tax rates. Additionally, statutory bodies like the central bank implement monetary policies. For example, the reduction or increase in interest rates and money supply is a monetary policy.

What are the five macroeconomic objectives?

Listed below are some of the principal aims behind macroeconomic analysis:

1. Controlling inflation,

2. Maintaining the balance of payment,

3. Stabilizing exchange rates,

4. Ensuring sustainable economic development, and

5. Reducing unemployment

Who is the father of macroeconomics?

The British economist John Maynard Keynes is renowned as the father of macroeconomics. In 1936, Keynes compiled the significant economic issues and variables to propose this concept. He published this in a book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

Recommended Articles

This has been a Guide to what is Macroeconomics and its Definition. Here we explain macroeconomics objectives, theories, & importance using examples. You may learn more about from these economics recommended articles below –

- Best Macroeconomics Books

- Economies of Scale vs Economies of Scope

- Microeconomics

- Behavioural Economics

As a branch of knowledge, Economics is concerned with observing, analysing and predicting human behaviour based on the distribution of scarce resources. This discipline aims to ascertain the allocation of resources such that the maximum level of production profit, consumer satisfaction and ultimately, social welfare is achieved.

To be more precise, this branch of knowledge is about generating and balancing preferences on the face of inadequate resources.

The discipline of Economics is broadly classified into two branches. Macroeconomics is one of them, and the objective of this branch is to examine broader economic concerns.

Key Takeaways

- Macroeconomics is the study of the economy as a whole, including inflation, economic growth, and unemployment rates.

- It analyzes the overall performance of an economy and helps policymakers make decisions that impact the country’s financial system.

- Macroeconomics provides insights into how an economy operates and how its various components, such as government, businesses, and individuals, interact.

The term ‘Macro’ in macroeconomics has been derived from the Greek word ‘makros,’ meaning large. In the context of economics, this term is used to imply larger economic concerns. To be more specific, the branch of macroeconomics is concerned with the economy, mostly national economy, as a whole.

It studies and handles the economic activities of the aggregate units of an economy. Therefore, some of the significant examples of macroeconomics variables include aggregate demand, national income, total output, total employment, aggregate supply, general price level and the like.

Features of Macroeconomics

In pursuit of its broader goals of comprehending more general problems of an economy, Macroeconomics assumes the following characteristic features.

- It examines and studies the economic forces or economic relationships at an aggregate level.

- As its scope of study deals with the entire economy as one entity, the degree of aggregation is vast. For example, questions of national income and different industries are considered an economy’s aggregate units.

- The principal problems that fall within the ambit of this branch of economics include:

- Optimum growth and utilisation of resources.

- Determination of the employment and income level.

- Principles and policies related to the above two problems.

- The fundamental instruments or tools that macroeconomics employ to study vital economic problems include aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

- The methodology that macroeconomics uses to study economics is called general equilibrium analysis. The primary objective of this method is to inquire and show the interdependence between macroeconomic variables like total output, total income, cumulative savings, total consumption and so on.

- Unlike in microeconomics, where the price is the principal determinant of economic problems, macroeconomics takes income as the central decisive factor affecting economic issues.

- As the determination of general price level and aggregate output constitutes one of the fundamental concerns of the macroeconomics, the branch is also referred to as the “Theory of income and employment.”

Advantages of Macroeconomics

While illustrating the substantial picture of an economy, macroeconomics exhibit the following advantages.

- It helps in the planning and formulation of national economic policies.

- Specific areas like national income, national investment, international trade can be dealt with only by using models of macroeconomics.

- Using macroeconomic models are essential for comprehending specific paradoxical situations in which the outcomes obtained from individual analysis proves to be in contravention of the entire economy’s perspective. For example, saving money may be considered beneficial for individual economic units. However, from the larger economic point of view, saving money can prove to be detrimental.

- It helps in analysing monetary issues like inflation and deflation and adopting suitable financial policies for the same.

Disadvantages of Macroeconomics

Despite their several utilities, the methods used in macroeconomics are not without limitations. The following are some significant disadvantages of macroeconomics.

- It assumes the aggregates to be homogeneous, which is not always the case.

- Macroeconomics often fails to represent the actual situation at the micro or individual level.

- Stabilisation measures implemented at the macro level do not have the same positive effect on various economic segments.

- Macroeconomic decisions sometimes prove to be detrimental to the interests of individual economic units.

References

- http://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/courses/undergraduate/Fall2019/AEB3281Stair.pdf

- https://ideas.repec.org/b/elg/eebook/450.html

Want to save this article for later? Click the heart in the bottom right corner to save to your own articles box!

Chara Yadav holds MBA in Finance. Her goal is to simplify finance-related topics. She has worked in finance for about 25 years. She has held multiple finance and banking classes for business schools and communities. Read more at her bio page.

Meaning of Macroeconomics

Economics is divided into two categories, micro and macroeconomics, but this has not always been the case. It was Ragnar Frisch who, in 1933, classified the economics into two categories. Before that, there was only one ‘Economics.’ Initially, economics was known as Political Economics.

The word ‘macro’ is derived from the Greek word ‘makros‘ meaning large.

Macroeconomics is that branch of economic theory that studies an economy (generally a country and sometimes a regional area) as a whole, using aggregate measures of output, consumption, prices, and employment. Gross Domestic Product is one of the most important macro measures.

Macroeconomics deals with issues such as economic growth, unemployment, inflation, and government policies that might influence the overall level of economic activity.

Macroeconomics target questions such as, how an economy allocates resources, how an economy determines overall savings, how the total investment is generated, what’s the pattern of imports and exports, how unemployment changes. It also targets questions that governments and consumers overall make decisions.

Macroeconomics looks at the big picture, at the way things are and how they develop after we add everything up, in the whole economy, or in large segments or sectors of the economy.

Macroeconomic relationships explain the aggregate behavior of economic agents – individuals and firms – for various levels of income, assets, liquidity, interest rates, relative prices, and other economic variables.

|

| macroeconomics |

Definitions

Macro economic theory is that part of economics which studies the overall averages and aggregates of the system. — Boulding

Macroeconomics deals with the functioning of the economy as a whole. — Shapiro

Examples of macroeconomics

Examples of macroeconomics are:

- National income and savings

- Aggregate demand and supply

- Level of employment

- Price level

- Rate of inflation

- National and International policies

- Exchange Markets

- International Economy(Import/Export) etc.

Macroeconomics is a relatively more challenging branch of economics.

The significance of economics is reflected in the points given below:

- Macroeconomics studies and analyses the economic problems/issues in the economy as a whole and tackle those issues with the help of economic tools.

- Macroeconomics facilitates the formation of economic policies. Without it, economic policies and schemes cannot be formulated as it provides the aggregate data of different economic activities of the economy.

- It also examines and analyses the reasons and causes of economic boons and banes and provides suitable solutions.

- Macroeconomic factors have a substantial impact on financial markets and on-demand for goods and services produced by companies; hence they are an important determinant of corporate performance.

Limitations of macroeconomics

Some of the major limitations of macroeconomics are:

- Macroeconomics fails to address the structural changes that come in an individual economic unit of an aggregate, say, change in the technology, availability of resources to an economic unit.

- «Most of the macro magnitudes which figure so largely in economic discussions are subject to errors and ambiguities.»- Hicks.

- Macroeconomics analysis describes variables in averages, say average per capita income’ which may be misleading if the impact of the income distribution is highly uneven.

Scope of macroeconomics

Areas that are covered under the scope or subject matter of macroeconomics are:

|

| scope of macroeconomics |

Uses of macroeconomics/ Why study macroeconomics

Macroeconomics is studied to solve many problems of an economy, such as monetary problems, economic fluctuations, general unemployment, inflation, and disequilibrium in the balance of payment.

1. In business decision making:

Managers need to understand the domestic and global economy’s institutional structure. A firm must understand the behavior of other organizations such as firms, governments( national and international) that affect its market.

Government policy and the structure of government constitute the environment in which firms operate. To survive in the market, a firm needs to understand the strategies of the opponent, behavior of the government and its policies. Hence, this requires a good understanding of macroeconomics.

2. To understand macroeconomic uncertainties:

The economic health of a company and people working in companies depends on the macroeconomy. Factors like rising in the wages, the strength of the competing firm, changes in interest rates, fluctuations in exchange rates, and shifts in the overall level of stock market prices affect individuals and companies. All of these factors are uncertain.

There are two types of uncertainties — (1) aggregate, (2) distinguishing. Aggregate uncertainty affects all firms and sectors in the economy, whereas distinguishing uncertainty affects only a few individuals, firms, or industries.

Macroeconomics studies about the aggregate sources of uncertainty that affect firms, workers, and consumers. Aggregate uncertainty is significant because it generates a risk that all firms and consumers share. Understanding macroeconomic uncertainty will, therefore, be useful to employees and companies.

3. To understand long-run factors:

Macroeconomics reflects the decisions and actions of all economic agents in the economy. An innovation in one firm or sector will eventually spread to the rest of the economy.

Macroeconomics is about dynamics that ultimately change the nature of a firm’s markets, its competitors, and the demands of a firm from its managers and workforce/employees. Studying macroeconomics is also important because it considers the long-run effect on the economy.

4. To understand economic growth:

With the increase in income, the level of living standards also increases, which means better quality of goods and services. People in a growing economy can consume more of all goods and services because the economy has more of the resources needed to produce these products.

Macroeconomics explains why resources increase over time and the consequences of our standard of living.

5. To understand economic fluctuations:

All economies are subject to economic fluctuations. Economic fluctuations affect the economy’s resources, labor, physical capital, human capital, and entrepreneurship.

Economic fluctuations cause prices to rise or fall. Macroeconomics helps us understand why these fluctuations occur and what the government can do to moderate the fluctuations.

6. To understand economic policies:

The government uses various policies to influence interest rates and the inflation rate. A manager could use macroeconomics knowledge to predict the effects of current public policies.

A manager who studies macroeconomics will be better equipped to understand the complexities of government policies and its consequences.

Macroeconomic Goals

Economists and all the society at large agree on the three important macroeconomic goals: economic growth, full employment, and stable prices.

1. Economic growth:

Economic growth is the increase in the production of goods and services that occur over a long period of time. It is measured by keeping track of real gross domestic product (GDP), that is, the total quantity of goods and services produced in a country over a year.

When real GDP rises faster than the population, output per person rises, and so does the average standard of living.

2. Unemployment:

It is an important microeconomic goal. A high unemployment rate means the economy is not achieving its full economic potential. A large number of people who want to work and produce additional goods and services are not able to do so. The same number of people but fewer goods and services are distributed among that population; hence the average standard of living will be lower.

This general effect on living standards gives us another reason to strive for consistently high rates of employment and low rates of unemployment.