From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the archaic name for Britain. For other uses, see Albion (disambiguation).

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than ‘Britain’ today. The name for Scotland in most of the Celtic languages is related to Albion: Alba in Scottish Gaelic, Albain (genitive Alban) in Irish, Nalbin in Manx and Alban in Welsh and Cornish. These names were later Latinised as Albania and Anglicised as Albany, which were once alternative names for Scotland.

New Albion and Albionoria («Albion of the North») were briefly suggested as names of Canada during the period of the Canadian Confederation.[1][2] Francis Drake gave the name New Albion to what is now California when he landed there in 1579.

Etymology[edit]

The toponym is thought to derive from the Greek word Ἀλβίων,[3] Latinised as Albiōn (genitive Albionis). It was seen in the Proto-Celtic nasal stem *Albiyū (oblique *Albiyon-) and survived in Old Irish as Albu (genitive Albann). The name originally referred to Britain as a whole, but was later restricted to Caledonia (giving the modern Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland: Alba).

The root *albiyo- is also found in Gaulish and Galatian albio- ‘world’ and Welsh elfydd (Old Welsh elbid ‘earth, world, land, country, district’). It may be related to other European and Mediterranean toponyms such as Alpes, Albania or the river god Alpheus (originally ‘whitish’). It has two possible etymologies: either from the Proto-Indo-European word *albʰo- ‘white’ (cf. Ancient Greek ἀλφός, Latin albus ), or from *alb- ‘hill’.

The derivation from a word for ‘white’ is thought to refer perhaps to the white Cliffs of Dover in the southeast, visible from mainland Europe and a landmark at the narrowest crossing point. On the other hand, Celtic linguist Xavier Delamarre argued that it originally meant ‘the world above, the visible world’, in opposition to ‘the world below’, i.e. the underworld.[4][5][6]

Attestation[edit]

Judging from Avienius’ Ora Maritima, for which it is considered to have served as a source, the Massaliote Periplus (originally written in the 6th century BC, translated by Avienus at the end of the 4th century AD), does not use the name Britannia; instead it speaks of nēsos Iernōn kai Albiōnōn «the islands of the Iernians and the Albiones».[7] Likewise, Pytheas (c. 320 BC), as directly or indirectly quoted in the surviving excerpts of his works in later writers, speaks of Albiōn and Iernē (Britain and Ireland). Pytheas’s grasp of the νῆσος Πρεττανική (nēsos Prettanikē, «Prettanic island») is somewhat blurry, and appears to include anything he considers a western island, including Thule.[8]

The name Albion was used by Isidore of Charax (1st century BC – 1st century AD)[9] and subsequently by many classical writers. By the 1st century AD, the name refers unequivocally to Great Britain. But this «enigmatic name for Britain, revived much later by Romantic poets like William Blake, did not remain popular among Greek writers. It was soon replaced by Πρεττανία (Prettanía) and Βρεττανία (Brettanía ‘Britain’), Βρεττανός (Brettanós ‘Briton’), and Βρεττανικός (Brettanikós, meaning the adjective British). From these words the Romans derived the Latin forms Britannia, Britannus, and Britannicus respectively».[10]

The Pseudo-Aristotelian text On the Universe (393b) has:

Ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγισται τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη

There are two very large islands in it, called the British Isles, Albion and Ierne.[11] (Britain and Ireland).

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (4.16.102) likewise has:

It was itself named Albion, while all the islands about which we shall soon briefly speak were called the Britanniae.[12][13]

In his 2nd century Geography, Ptolemy uses the name Ἀλουΐων (Alouiōn, «Albion») instead of the Roman name Britannia, possibly following the commentaries of Marinus of Tyre.[14] He calls both Albion and Ierne νῆσοι Βρεττανικαὶ (nēsoi Brettanikai, «British Isles»).[15][16]

In 930, the English king Æthelstan used the title Rex et primicerius totius Albionis regni («King and chief of the whole realm of Albion»).[17] His nephew, Edgar the Peaceful, styled himself Totius Albionis imperator augustus «Augustus Emperor of all Albion» in 970.[18]

The giants of Albion[edit]

Albina and other daughters of Diodicias (front). Two giants of Albion are in the background, encountered by a ship carrying Brutus and his men. Brut Chronicle, British Library Royal 19 C IX, 1450–1475

A legend exists in various forms that giants were either the original inhabitants, or the founders of the land named Albion.

Geoffrey of Monmouth[edit]

According to the 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae («The History of The Kings of Britain») by Geoffrey of Monmouth, the exiled Brutus of Troy was told by the goddess Diana:

Brutus! there lies beyond the Gallic bounds

An island which the western sea surrounds,

By giants once possessed, now few remain

To bar thy entrance, or obstruct thy reign.

To reach that happy shore thy sails employ

There fate decrees to raise a second Troy

And found an empire in thy royal line,

Which time shall ne’er destroy, nor bounds confine.

After many adventures, Brutus and his fellow Trojans escape from Gaul and «set sail with a fair wind towards the promised island».[19]

«The island was then called Albion, and inhabited by none but a few giants. Notwithstanding this, the pleasant situation of the places, the plenty of rivers abounding with fish, and the engaging prospect of its woods, made Brutus and his company very desirous to fix their habitation in it.» After dividing up the island between themselves «at last Brutus called the island after his own name Britain, and his companions Britons; for by these means he desired to perpetuate the memory of his name».[20] Geoffrey goes on to recount how the last of the giants are defeated, the largest one called Goëmagot is flung over a cliff by Corineus.

Anglo-Norman Albina story[edit]

Later, in the 14th century, a more elaborate tale was developed, claiming that Albina and her sisters founded Albion and procreated there a race of giants.[21] The «Albina story» survives in several forms, including the octosyllabic Anglo-Norman poem «Des grantz geanz» dating to 1300–1334.[22][a][23][24][b][26] According to the poem, in the 3970th year of the creation of the world,[c] a king of Greece married his thirty daughters into royalty, but the haughty brides colluded to eliminate their husbands so they would be subservient to no one. The youngest would not be party to the crime and divulged the plot, so the other princesses were confined to an unsteerable rudderless ship and set adrift, and after three days reached an uninhabited land later to be known as «Britain». The eldest daughter Albina (Albine) was the first to step ashore and lay claim to the land, naming it after herself. At first, the women gathered acorns and fruits, but once they learned to hunt and obtain meat, it aroused their lecherous desires. As no other humans inhabited the land, they mated with evil spirits called «incubi», and subsequently with the sons they begot, engendering a race of giants. These giants are evidenced by huge bones which are unearthed. Brutus arrived 260 years after Albina, 1136 before the birth of Christ, but by then there were only 24 giants left, due to inner strife.[26] As with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version, Brutus’s band subsequently overtake the land, defeating Gogmagog in the process.[26]

Manuscripts and forms[edit]

The octosyllabic poem appears as a prologue to 16 out of 26 manuscripts of the Short Version of the Anglo-Norman prose Brut, which derives from Wace. Octosyllabic is not the only form the Anglo-Norman Des Grantz Geanz, there are five forms, the others being: the alexandrine, prose, short verse, and short prose versions.[22][27] The Latin adaptation of the Albina story, De Origine Gigantum, appeared soon later, in the 1330s.[28] It has been edited by Carey & Crick (1995),[29] and translated by Ruth Evans (1998).[30]

Diocletian’s daughters[edit]

A variant tale occurs in the Middle English prose Brut (Brie ed., The Brut or the Chronicles of England 1906–1908) of the 14th century, an English rendition of the Anglo-Norman Brut deriving from Wace.[d][31][32] In the Prolog of this chronicle, it was King «Dioclician» of «Surrey» (Syria[33]), who had 33 daughters, the eldest being called «Albyne». The princesses are all banished to Albion after plotting to murder their husbands, where they couple with the local demons; their offspring became a race of giants. The chronicle asserts that during the voyage Albyne entrusted the fate of the sisters to «Appolyn,» which was the god of their faith. The Syrian king who was her father sounds much like a Roman emperor,[33] though Diocletian (3rd century) would be anachronistic, and Holinshed explains this as a bungling of the legend of Danaus and his fifty daughters who founded Argos.[34]

Later treatment of the myth[edit]

Because Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work was regarded as fact until the late 17th century, the story appears in most early histories of Britain. Wace, Layamon, Raphael Holinshed, William Camden and John Milton repeat the legend and it appears in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene.[35]

William Blake’s poems Milton and Jerusalem feature Albion as an archetypal giant representing humanity.[citation needed]

In 2010, artist Mark Sheeky donated the 2008 painting «Two Roman Legionaries Discovering The God-King Albion Turned Into Stone» to the Grosvenor Museum collection.[36]

See also[edit]

- Britain (place name) – Place name

- Clas Myrddin, an early name for Great Britain given in the Third Series of Welsh Triads.

- New Albion – Historical name of the United States Pacific coast

- Nordalbingia, based on the Latin name for the Elbe River: Alba

- Perfidious Albion – Pejorative epithet for Great Britain

- Terminology of the British Isles – Overview of the terminology of the British Isles

Notes[edit]

- ^ Brereton 1937, p. xxxii had allowed for earlier dating range, giving 1200 (more likely 1250) to 1333/4: «not earlier than the beginning – probably not before the middle – of the thirteenth century and not later than 1333–4»

- ^ The same text (same MS source) as Jubinal (Cotton Cleopatra IX) occurs in Francisque Michel ed., Gesta Regum Britanniae (1862), under the Latin title De Primis Inhabitatoribus Angliæ and incipit.[25]

- ^ Brereton 1937, p. 2, «Del mound, treis mil e nef cent/E sessante e diz ans» ll.14–15; but «treis» is lacking in Michel 1862 so that it reads «1970 years»

- ^ In the Anglo-Norman prose Brut, the poem prefaced to the Short Version was incorporated to the text proper (prologue) of the Long Version, from the long version. This long version was then rendered into Middle English.Lamont 2007, p. 74

References[edit]

- ^ «How Canada Got Its Name». about.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names. University of Toronto Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- ^ Ancient Greek «… ἐν τούτῳ γε μὴν νῆσοι μέγιστοι τυγχάνουσιν οὖσαι δύο, Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Ἀλβίων καὶ Ἰέρνη, …», transliteration «… en toutôi ge mên nêsoi megistoi tynchanousin ousai dyo, Brettanikai legomenai, Albiôn kai Iernê, …», Aristotle: On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos., 393b, pages 360–361, Loeb Classical Library No. 400, London William Heinemann LTD, Cambridge, Massachusetts University Press MCMLV

- ^ Freeman, Philip; Koch, John T. (2006). Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture, ABC–CLIO. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (2nd ed.). Errance. pp. 37–38.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1930). «Early names of Britain». Antiquity. 4 (14): 149–156. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00004464. S2CID 161954639.

- ^ Avienius’ Ora Maritima, verses 111–112, i.e. eamque late gens Hiernorum colit; propinqua rursus insula Albionum patet.

- ^ G. F. Unger, Rhein. Mus. xxxviii., 1883, pp. 1561–1596.

- ^ Scymnus; Messenius Dicaearchus; Scylax of Caryanda (1840). Fragments des poemes géographiques de Scymnus de Chio et du faux Dicéarque, restitués principalement d’après un manuscrit de la Bibliothèque royale: précédés d’observations littéraires et critiques sur ces fragments; sur Scylax, Marcien d’Héraclée, Isidore de Charax, le stadiasme de la Méditerranée; pour servir de suite et de supplément à toutos les éditions des petits géographes grecs. Gide. p. 299.

- ^ Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ Aristotle or Pseudo-Aristotle; E. S. Forster (translator); D. J. Furley (translator) (1955). «On the Cosmos, 393b12». On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos. William Heinemann, Harvard University Press. pp. 360–361. at the Open Library Project.DjVu

- ^ Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia Book IV. Chapter XLI

Latin text Archived 2014-07-19 at the Wayback Machine and

English translation Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

at the Perseus Project. See also Pliny’s Natural history. In thirty-seven books at the Internet Archive. - ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, lemma Britanni Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine II.A at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Ptolemy’s Geographia, Book II – Didactic Analysis Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, COMTEXT4

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1843). «index of book II» (PDF). In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia. Vol. 1. Leipzig: sumptibus et typis Caroli Tauchnitii. p. 59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-08.

- ^ Βρεττανική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ England: Anglo-Saxon Royal Styles: 871–1066, Anglo-Saxon Royal Styles (9th–11th centuries) Archived 2010-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, archontology.org

- ^ Walter de Gray Birch, Index of the Styles and Titles of Sovereigns of England, 1885

- ^ History of the Kings of Britain/Book 1, 15

- ^ History of the Kings of Britain/Book 1, 16

- ^ Bernau 2007

- ^ a b Dean, Ruth (1999), Anglo-Norman Literature: A Guide to Texts and Manuscripts, pp. 26–30, cited by Fisher, Matthew (2004). Once Called Albion: The Composition and Transmission of History Writing in England, 1280–1350 (Thesis). Oxford University. p. 25. Archived from the original on 2014-03-09.. Fisher: «five distinct versions of Des Grantz Geanz: the octosyllabic, alexandrine, prose, short verse, and short prose versions survive in 34 manuscripts, ranging in date from the first third of the fourteenth to the second half of the fifteenth century»

- ^ Brereton 1937

- ^ Jubinal 1842, pp. 354–371

- ^ Michel 1862, pp. 199–254

- ^ a b c Barber 2004

- ^ Wogan-Browne, Jocelyn (2011), Leyser, Conrad; Smith, Lesley (eds.), «Mother or Stepmother to History? Joan de Mohun and Her Chronicle», Motherhood, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe, 400–1400, Ashgate Publishing, p. 306, ISBN 978-1409431459

- ^ Carley & Crick 1995, p. 41

- ^ Carley & Crick 1995

- ^ Evans 1998

- ^ Brie 1906–1908

- ^ Bernau 2007, p. 106

- ^ a b Baswell, Christopher (2009), Brown, Peter (ed.), «English Literature and the Classical Past», A Companion To Medieval English Literature and Culture, c.1350–c.1500, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 242–243, ISBN 978-1405195522

- ^ Historie of England 1587, Book 1, Chapter 3

- ^ Harper, Carrie Anne (1964). The Sources of the British Chronicle History in Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Haskell House. pp. 48–49.

- ^ «Chester Grosvenor Art competition: winners». Cheshire Today. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

Bibliography[edit]

Albina story[edit]

- Jubinal, Achille, ed. (1842), «Des graunz Jaianz ki primes conquistrent Bretaingne (Bibl. Cotton Cleopatra D IX)», Nouveau recueil de contes, dits, fabliaux et autres pièces inédites des XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles, pour faite suite aux collections de Legrand d’Aussy, Barbazan et Méon, Pannier, pp. 354–371

- Michel, Francisque, ed. (1862), «Appendix I: De Primis Inhabitatoribus Angliæ», Gesta Regum Britanniæ: a metrical history of the Britions of the XIIIth century, Printed by G. Gounouilhou, pp. 199–214

- Barber, Richard, ed. (2004) [1999], «1. The Giants of the Island of Albion», Myths & Legends of the British Isles, Boydell Press

- Brie, Friedrich W. D., ed. (1906–1908), The Brut or the Chronicles of England … from Ms. Raw. B171, Bodleian Library, &c., EETS o.s., vol. 131 (part 1), London

- Carley, James P.; Crick, Julia (1995), Carley; Riddy, Felicity (eds.), «Constructing Albion’s Past: An Annotated Edition of De origine gigantum», Arthurian Literature XIII, D. S. Brewer, pp. 41–115, ISBN 0859914496

- Evans, Ruth (1998), Carley; Riddy, Felicity (eds.), «Gigantic Origins: An Annotated Translation of De origine gigantum», Arthurian Literature XVI, D. S. Brewer, pp. 197–217, ISBN 085991531X

- Lamont, Margaret Elizabeth (2007), «Albina, her sisters, and the giants of Albion», The «Kynde Bloode of Engeland»: Remaking Englishness in the Middle English Prose «Brut», pp. 73ff, ISBN 978-0549482543

Studies[edit]

- Bernau, Anke (2007), McMullan, Gordon; Matthews, David (eds.), «Myths of origin and the struggle over nationhood», Reading the Medieval in Early Modern England, Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–118, ISBN 978-0521868433

- Brereton, Georgine Elizabeth, ed. (1937), Des grantz geanz: an Anglo-Norman poem, Medium Aevum Monographs, vol. 2, Oxford: Blackwell

Asked by: Dr. Mustafa Bergstrom MD

Score: 4.7/5

(62 votes)

The name Albion has been translated as “white land”; and the Romans explained it as referring to the chalk cliffs at Dover (Latin albus, “white”). …

What does Albion mean in Latin?

Origin of albion

Ancient Gallo-Latin name for Britain, Albiōn (Middle Welsh Albbu, Old Irish Albu), is from Proto-Celtic *albiyū (“world”) (stem : *albiyon-), ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *h₂élbʰos, *álbʰos (“white”), whence also Latin albus (“white”) and Ancient Greek ἀλφός (alphos, “whiteness, white leprosy”).

Can Albion be a name?

The name Albion is primarily a male name of English origin that means White Land — Great Britain. Oldest known name of Great Britain, said to have come from the Latin word Albus meaning white.

What do you call someone from Albion?

Albionian — a citizen of Albion with diverse cultures (like Italy and Italian) Albionese — a cultural nation of Albion (like Spain and Spanish) Albioner — a people founded on a Germanic city of Albion (like Hamburg and Hamburger)

What does the poetic name Albion stand for?

Albion is an ancient poetic name for Britain. May derive from the Latin «albus» referring to the whiteness of cliffs seen from the sea, or from the Celtic «alp». Used in England until the 1930s.

41 related questions found

Does Albion mean white?

The name Albion has been translated as “white land”; and the Romans explained it as referring to the chalk cliffs at Dover (Latin albus, “white”).

What does Albion mean in French?

Old English, from Latin, probably of Celtic origin and related to Latin albus ‘white’ (in allusion to the white cliffs of Dover). The phrase perfidious Albion (mid 19th century) translates the French la perfide Albion, alluding to alleged treachery to other nations.

What was Albion before?

Albion was replaced by the Latin ‘Britannia’, and the Romans called the natives of England the Britons. With the replacement of the name for the country, Albion became to be used for place names from a toponymic feature involving chalk cliffs, at least in the 19th century.

What is an Albion bird?

Most West Bromwich Albion logos feature a thrush. According to legend, this bird often flew to the football field during matches. According to another version, she was kept in a brothel, in which the players went.

Who was the first king of Albion?

The monarchy in Albion was restored with the formation of the Kingdom of Albion, founded by the Hero of Bowerstone. Logan assumed the throne after the Hero of Bowerstone died, but lost the throne to his sibling, the Hero of Brightwall, after they orchestrated a revolution to overthrow the tyrannical Logan.

Can you change name Albion?

As far as I know you cannot change your character name in Albion. My guess is the reasoning behind this is that in a game where reputation matters a lot, you can’t have people easily changing their names to escape their (bad) reputation.

What does Albion mean in Merlin?

Merlin. Albion is a landmass that constitutes the island currently known as Great Britain. Once, the land of Albion was united in an age of peace, during which all of its inhabitants followed the Old Religion.

Why is Brighton called Albion?

Albion is an archaic alternative name for ‘Great Britain’, which was generally only used to describe areas with white cliffs in the south of England. Thus, the ‘Albion’ is believed to derive from this, given Brighton’s location on England’s south coast.

What is the oldest name in England?

Believe it or not, the oldest recorded English name is Hatt. An Anglo-Saxon family with the surname Hatt are mentioned in a Norman transcript, and is identified as a pretty regular name in the county. It related simply to a hat maker and so was an occupational name.

What did Romans call England?

Britannia, the Roman name for Britain, became an archaism, and a new name was adopted. “Angleland,” the place where the Angles lived, is what we call England today.

Does Albion mean Scotland?

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. … The name for Scotland in most of the Celtic languages is related to Albion: Alba in Scottish Gaelic, Albain (genitive Alban) in Irish, Nalbin in Manx and Alban in Welsh and Cornish.

What was England called in Viking times?

The Viking territory became known as the Danelaw. It comprised the north-west, the north-east and east of England. Here, people would be subject to Danish laws. Alfred became king of the rest.

What did the Celts call England?

‘Pretani’, from which it came from, was a Celtic word that most likely meant ‘the painted people’. ‘Albion’ was another name recorded in the classical sources for the island we know as Britain. ‘Albion’ probably predates ‘Pretannia’.

Is Alba a biblical name?

Alba is baby girl name mainly popular in Christian religion and its main origin is Catalan, Italian, Latin, Spanish. Alba name meanings is Fair, white. People search this name as Meaning of alba in the bible, Albahis in urdu meaning.

What does Alba mean in the Bible?

What does Alba mean in the Bible? From the Latin alba or albus, meaning “white”.

What does Alba mean in Scottish?

Alba (/ˈælbə, ˈælvə/ AL-bə, AL-və, Scottish Gaelic: [ˈal̪ˠapə]) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland.

What is Albion Arthurian legend?

In Arthurian legends, Albion is a name for the island of Britain.

Why is West Bromwich Albion?

The ‘Strollers’ name came about because there were no footballs on sale in West Bromwich, so a walk to nearby Wednesbury was necessary in order to buy one. They were renamed West Bromwich Albion in either 1879 or 1880, becoming the first team to adopt the Albion suffix.

Who said perfidious Albion?

After their victory against England at the 1950 World Cup, the president of the Spanish Football Federation sent a telegram to Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco that read, «we have beaten Perfidious Albion.»

The white cliffs of Dover—

to which the name Albion did not originally refer [cf. note].

(photograph: Wikimedia Commons/Fanny)

The name Albion first appeared in English in the very first sentence of the first Book of the 9th-century translation of Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) originally written by the English monk, theologian and historian St. Bede (circa 673-735):

– Old English text:

Breoton ist garsecges¹ ealond, ðæt wæs iu geara² Albion haten : is geseted betwyh norðdæle and westdæle, Germanie and Gallie and Hispanie þam mæstum dælum Europe myccle fæce ongegen.

(¹ garsecges: genitive singular of garsecg, ocean, sea — ² geara = yore)

– translation:

Britain is an island of the ocean, that was a long time ago called Albion; it lies between the north and the west, opposite, though far apart, to Germany, Gaul and Spain, the chief divisions of Europe.

– original Latin text:

Brittania Oceani insula, cui quondam Albion nomen fuit, inter septentrionem et occidentem locata est, Germaniæ, Galliæ, Hispaniæ, maximis Europæ partibus, multo interuallo aduersa.

The classical Latin name Albion was used by the Roman statesman and scholar Pliny the Elder (23-79) in his encyclopaedia of the natural and human worlds, The Natural History (Naturalis Historia – 77):

ex adverso huius situs britannia insula, clara græcis nostrisque monimentis, inter septentrionem et occidentem iacet, germaniæ, galliæ, hispaniæ, multo maximis europæ partibus, magno intervallo adversa. albion ipsi nomen fuit, cum britanniæ vocarentur omnes de quibus mox paulo dicemus.

translation:

Opposite to this coast is the island called Britannia, so celebrated in the records of Greece and of our own country. It is situated to the north-west, and, with a large tract of intervening sea, lies opposite to Germany, Gaul, and Spain, by far the greater part of Europe. Its former name was Albion; but at a later period, all the islands, of which we shall just now briefly make mention, were included under the name of Britanniæ.

According to Bernhard Maier in Dictionary of Celtic Religion and Culture (translation Cyril Edwards – 1997), Albion is probably cognate with Middle Welsh elfydd, meaning world, land, and with Albiorix, the name of a Gaulish god probably meaning king of the World or king of the Land. Albiorix was probably the father or chief deity of the Albici tribe of southern Gaul.

These words seem to be from the same base as classical Latin albus, white. The Celtic base underlying the name Albion probably originally denoted the world above ground, illuminated by the sun, as opposed to the dark underworld — Albion did not originally refer to the white cliffs of Dover, regarded as a symbol of Great Britain [cf. note].

Originally therefore, Albion denoted the island of Britain. It was later applied to the nation of Britain or England. For example, in The Tragedie of King Lear (1603-06), the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616) makes the fool say:

(Folio 1, 1623)

Ile speake a Prophesie ere I go:

When Priests are more in word, then matter;

When Brewers marre their Malt with water;

When Nobles are their Taylors Tutors,

No Heretiques burn’d, but wenches Sutors;

When euery Case in Law, is right;

No Squire in debt, nor no poore Knight;

When Slanders do not liue in Tongues;

Nor Cut-purses come not to throngs;

When Vsurers tell their Gold i’th’Field,

And Baudes, and whores, do Churches build,

Then shal the Realme of Albion, come to great confusion.

The first known user of the French phrase la perfide Albion (the perfidious Albion) is the Marquis de Ximenès (1726-1817). In a poem titled L’ère républicaine (The republican era), he referred to the British joining the allies who were already fighting France in 1793:

Des Grecs et des Romains imitons le courage !

Attaquons dans ses eaux la perfide Albion !

Que nos fastes s’ouvrant par sa destruction

Marquent les jours de la victoire !

translation:

Of the Greeks and the Romans let’s imitate the courage!

Let’s attack in her waters the perfidious Albion!

May our annals opening with her destruction

Mark the days of victory!

This was a popular expression during the Revolution. For example, Le Mercure français of 6th October 1794 published an ode titled Le Vengeur (The Avenger), which contains the following:

Mais de nombreux vaisseaux les ondes sont couvertes.

La perfide Albion s’irritant par ses pertes,

Des batailles encore veut tenter le hasard.

translation:

But of many vessels the waters are covered.

The perfidious Albion irritated by her losses,

Of the battles still wants to tempt the fate.

The expression la perfide Angleterre (the perfidious England) had been used in 1653 by the French bishop and theologian Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627-1704) in premier sermon pour la fête de la circoncision de Notre-Seigneur (first sermon for the feast day of the circumcision of Our Lord). Explaining that the Christian faith has spread all over the world, he writes:

L’Angleterre, ha ! la perfide Angleterre, que le rempart de ses mers rendait inaccessible aux Romains, la foi du Sauveur y est abordée.

translation:

England, ha! the perfidious England, that the rampart of her seas made inaccessible to the Romans, the Saviour’s faith reached it.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (3rd edition – 2005), in France, the phrase la perfide Albion was popularised during a recruitment campaign under Napoleon I in 1813, but its use as a slogan did not become widespread until 1840-1. It was adopted into German in its French form during the early 19th century and had become naturalised by the time of Bismarck. It was used in German anti-British propaganda during the First World War and during the Second World War to undermine French trust in Britain as an ally.

The French phrase was used by the Irish author Charles James Lever (1806-72) in Tom Burke, of “Ours” (1844):

The Emperor always connected in his mind — and with good reason, too — the machinations of the Royalists with the plans of the English Government. He knew that the land which afforded the asylum to their king was the refuge of the others also; and many of the heaviest denunciations against the “perfide Albion” had no other source than the dread, of which he could never divest himself, that the legitimate monarch would one day be restored to France.

The phrase the perfidious Albion seems to have been first used in 1801 in The Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the year 1799. This periodical reported that during a parliamentary debate in France that year, one of the deputies, Moreau, had said:

What! do you talk of a committee, at the moment when your country points out the men who are her murderers, and this hall still re-echoes the transactions of the abominable assassins employed by royalty? They come for the purpose of seconding the designs of the perfidious Albion, for the destruction of the republic.

Note: It has often been said that Albion originally referred to the white cliffs of Dover. This erroneous interpretation was mentioned as early as around 1447 in Mappula Angliae, by the English poet and Augustinian friar Osbern Bokenham (circa 1393-circa 1464):

Old auctors seyene that this yle was clepyd Albyoun, perauenture of the white Craggis and Clyffis abowt the see-bankys, þe wych apperyne ferre in the see to heme þat commyne þer-towarde.

translation:

Old authors say that this island was called Albion, perhaps from the white crags and cliffs about the shores, which appear far in the sea to the one who comes towards them.

REPUBLIC

OF IRELAND

©

Oxford University Press

GREAT

BRITAIN

ENGLAND

London

Channel

Islands’*»

►

Identifying

symbols of the four nations

England Wales

l

Some

historical and poetic names

Albion

is

a

word used in some

poetic or

rhetorical contexts to refer to England. It was the original

Roman

name for Britain. It rnay coilie from the Latin word albus, meaning

‘white’. The white chalk cliffs around Dover on

the

south coast are the first part of England to be seen when Crossing

tlie

sea from the European mainland.

Britannia

is the name that the Romans gave to their Southern British province

(which covered, approximately, the area of present-day England). It

is also the name given to the female ernbodi- ment of Britain,

always shown wearing a helmet and holding a trident {the symbol of

power over the sea), hence the patriotic song which begins ‘Rule

Britannia,

Britannia rule the waves’. The figtire of Britannia has been on the

reverse side of many Britisli coins for more than 300 years.

People

often

refer to Britain

by

another name,

They call it

‘England’. But

this

is

not

striclly correct,

and it can make some

people

angry, England

is

only

one of

the four

nations of

the

British

Isles (England, Scotland,

Wales

and

Ireland).

Their

political

unification was

a gradual

process

that

took

several

hundred years

(see chapter

2).

It was completed

in

1

800

when the Irish

Parliament

was joined

with the Parliament

for

England, Scotland

and

Wales

in Westminster, so

that the

whole

of

the

British

Isles

became a

single

state

— the United Kingdom

of Great Britain

and Ireland.

However, in

1922,

most

of

Ireland

became

a

separate

state

(see chapter 12).

At

one time the four nations

were distinct

from

each other in

almost every

aspect

oflife.

In

the

first

place,

they

were

different

Scotland Ireland

Flag

St

George’s Cross

Plant

Britannia

Dragon

of St Andrews St Patricks

Cadwallader Cross Cross

I

I

Rose

Lion

rampant Republic of Ireland

Leek/Daffodil1

Thistle

Shamrock

Coiour1

St

Andrew St Patrick

30

November I 7 March

Patron

saint St

George St David

Saint’s

day 23

April I March

racially.

The people in Ireland, Wales and highland Scotland belonged to the

Celtic race; those in England and lowiand Scotland were mainly of

Germanic origin. This difference was reflected in the languages

they spoke. People in the Celtic areas spoke Celtic languages:

Irish Gaelic, Scottisli Gaelic and Welsh. People in the Germanic

areas spoke Germanic dialects (including the one which has

developed into modern English). The nations also tended to have

different economic, social and legal Systems.

Today

these differences have become blurred. But they have not compietely

disappeared. Although there is only one government for the whole of

Britain, and people have the same passport regardless of where in

Britain they live, some aspects of government are organized

separately (and sometimes differently) in the four parts of the

United Kingdom. Moreover, Welsh, Scottisli and Irish people feel

their identity very strongly.

Other

signs

of

national identity

The

following are also associated by British people with one or more of

the four nations.

Names

The

prefix ‘Mac’ or ‘.Mc’ in surnames (such as McCall,

MacCarthy, MacDonald) is always either Scottisli or Irish. The

prefix ‘O’ (as in O’Brien, O’Hara) is distinctly Irish. A very

large number of surnames (for example, Davis, Evans, Jones, Lloyd,

Morgan, Price, Rees, Williams) suggest Welsh origin (although many

of these are found throughout England). The most common surname in

both England and Scotland is actually ‘Smith’.

First

names can also be indicative, The Scottish form of‘John’ is Tan’

and its Irish form is ‘Sean’ (although all three names are

common throughout Britain). There are also nicknames for Scottish,

Irish and Welsh men. For example, an English, Welsh or Irish person

might refer to and address a Scottish friend as ‘Jock’, whatever

his first name is. Irishmen are called ‘Paddy’ or ‘Mick’ and

Welshmen are known as ‘Dai’ or ‘Taffy’. If the person is not a

friend the mckname can sound rather

insulting.

Clothes

The

kilt, a skirt with a tartan pallern worn by men, is a very

well-known symbol of Scottishness (though it is hardly ever worn in

everyday life).

Musical

instrmnents

The

harp is an emblem of both Wales and Ireland. The bagpipes are

regarded as disiinclively Scottish (though a smaller type is also

used in traditional Irish music).

Characteristics

There

are ceriain stereotypes of national character which are well- known

in Britain. For instance, the Irish are supposed to be great

talkers, the Scots have a reputation for being careful with money,

and the Welsh are renowned for their singing ability. These

characteristics are, of course, only caricatures and are not

reliable descriptions of individual people from these

countries. Nevertheless, they indicate some slighl differences in

the value attached to certain kinds of beliavi- our in the countries

concerned.

John

Bull is a

ficdonal

character

who is supposed to personify Englishness and certain English

virtues. (He can be compared to Uncle Sam in the USA.) He features

in liuncLreds of nineteenth Century Cartoons.

His

appearance is typical of an eighteenlh Century

country’

gentleman, evoking an idyllic rural past (see chapter <;).

John

Bull

Briton

is a word used in official con- texts and in formal writing to

describe a Citizen

of

the United Kingdom. ‘Ancient Brilons’ is the name given to the

race of people who lived in England before and during the Roman

occupation (ad

43-410).

These are the ancestors of the present-day Welsh people.

Caledonia,

Cambria and Hibernia

were

tlie Roman names for Scotland, Wales and Ireland respectively. The

words are commonly used today in scholarly classifications (for

example, the type of English used in Ireland is sometimes called

‘Hiberno-Engiish’) and for the names of organizations (for

example, the airline ‘British Caledonian).

Erin

is a poetic name for Ireland. ‘The Emeraid Isle’ is another way of

refer- ring to Ireland, evoking the lush greenery of its

countryside.

►

The

invisible Scot

Here

are some brief extracts from an article vmtten by a Scotswoman,

Janet Swinney, which expresses anger at how the dominance of England

over Scotland is reflected in ihe way things are described.

First,

there is ‘domination by otnission’. Amap appeared in the Observer

newspaper in May 1989 under the heading ‘Britam’s Dirty Rivers’.

It showed only England and Wales. Janet Swinney says: ‘What is the

meaning of this Illustration? Does Scotland have no rivers or no

dirty rivers, or has someone sirnply used the word Britain to mean

England and Wales?’

Second,

she points out the common use of England/English io mean

Brinim/British: ‘When I werit to Turkey a few years ago with an

assorted group of Britons, most of the English were happy to record

their nalionality on their embarka- tion cards as English, and saw

nothing offensive about it. It s not unusual, either, for Scots to

receive mail from elsewhere in the UK addressed Scotland,

England , .. Last year, Werks of art from the Soviet Union intended

for display ai Lhe Edinburgh Internationa] Festival were sent

to the City Art Gallery addressed Edinburgh, England’.

A

tliird aspect of domination can be seen in the names given to pub-

lications and organizations: ‘The practice is to label anything that

per- tains to England and (usually) Wales as though it were the

norm, and anything Scottish as though it were a deviation from it.

Why eise do we have The Times Educational Supplement and The Times

Educational Supplemeni (Scotland), the “National Trust” and the

“National Trust for Scotland», the “Trades Union Congress”

and the “Scottish Trades Union Congress»? In a society

of equals, all these names would carry their geo- graphical markers:

The Times Educational Supplement (England and Wales) etc’.

J

Swinney, ‘The Invisible Scot’,

English

Today, April 19 89

There

is, perhaps, an excuse for people who use the word ‘England’

when they mean ‘Britain’. It cannot be denied that the dominant

culture of Britain

today

is

specifically

English.

The

system

of

politics that

is used

in

all

four

nations today

is

of

English origin, and

English

is

the

main language of all

four nations.

Many aspects of everyday life are organiz.ed according

to

English

custom

and practice.

But

the

political

unification

of Britain was not achieved by

mutual agreement. O11 the contrary,

It

happened

because England was able

to exert her economic and

military

power over the other

three

nations (see

chapter

2).

Today

English domination can

be

detected

in

the

way in which various

aspects

of British

public life are

described (t> The invisible Scot). For

example,

the

supply

of

money

in

Britain is

controlled

by the Bank

of England (there

is

no

such

thfng as

a ‘Bank

of

Britain’).

The

present

queen

of

the country

is universally known

as

‘Elizabeth the Second’,

even though

Scotland

and Northern

Ireland have

never

had

an

‘Elizabeth

the

First’! (Elizabeth

I

of England

and

Wales

ruled

from

1

^53

to 1603.)

The

term

‘Anglo’ is

also

commonly

used.

(The Angles

were

a

Germanic

tribe

who

settled

in

England

in the

fifth Century. The word ‘England’

is derived from

their name.) For

example,

newspapers

and the

television

news

talk about ‘Anglo-American

relations’

to

refer

to relations

between

the

governments

of

Britain

and

the

USA (and not

just

those between England and

the

USA).

National

loyalties

When

you

are

talking

to

people

from

Britain, it

is safest

to use ‘

Britain’

when

talking

about where

they

live

and

‘British’

as

the adjective to describe

their

nationality.

This

way you

will

be

less

likely

to

offend anyone.

It

is,

of

course, not

wrong

to

talk

about ‘people in

England’

if

that is what

you

mean

— people who

live

within the geographica] boundaries

of

England,

After all,

most

British

people

live

there

(>

Populations

in

1993).

But

it

should

always

be

remembered

that

England

does not

make

up

the whole of

the UK.

There

has

been

a long

history of

migration

from Scotland, Wales and

Ireland to

England. As

a

result

there are

millions of

people

who live in

England but who

would

never describe

themselves

as English. They may have

lived

in

England

all their

lives, but as

far

as

they are concerned they

are Scottish

or

Welsh

or Irish —

even

if, in

the

last

case, they

are

citizens

of

Britain

and not of

Eire.

These

people

support

the

country

of

their parents or

grandparents rather than

England

in

sporting

contests. They

would also, given

the clrance, play for

that

country

rather

than

England.

If,

for

example,

you had heard

the

meinbers of the

Republic

of Ireland

World Cup

football

leam talking in

1994,

you

would have heard

several different kinds of

English accent

and

some

Scottish

accents,

but only

a

few

Irish accents.

Most

of

tlie

players did

not live

in

Ireland

and were

not

brought up

in

Ireland.

Nevertbeless,

most

of them would

never have

considered

playing

for

any

country other than

Ireland!

The

same

holds

true for the further millions of

British

citizens

whose family

origins

lie

outside

the

British

Isles

altogetlier.

People

of

Caribbean

or

south Asiat! descent, for instance, do not

mind

being

described as ‘British’ (many are proud

of it),

but

many

of them

would

not

like to

be called

‘English’.

And whenever the West Indian

or

Indian cricket

team plays

against England,

it is

certainly not

England

that

they

support!

There

is, in fact,

a

complicated

division of

loyalties

among

many people

in

Britain,

and especially

in England. A black

person

whose family

are

from

the

Caribbean will passionately supporl

the

West Indies

when they play

cricket

against

England. But

the

same

person

is

quite

happy

to support England

just

as

passionately

in

a

sport

such

as

football, which the

West Indies

do not

play.

A

person

whose

family

are from

Ireland

but who

has always lived

in

England

would want

Ireland

to

beat England

at

Football but

would

want

England to

beat

(for

example)

Italy just

as much.

This

crossover

of loyalties

can

work the

other

way as well.

English

people do

not

regard

the ScotLish,

the Welsh

or

the

Irish

as

‘foreigners’

(or, at least,

not

as the

same kind

of

foreigners

as

other

foreigners!).

An English commentator of

a spordng

event in

which

a

Scottish,

Irish

or

Welsh

team is

playing

against a team from outside the

British

Isles

tends

to identify

with

that

team as

if it

were

English.

A

wonderful example

of

double

identity

was

heard

on the

BBC

during

the Eurovision Song

Contest in

1992.

The

commentator

for

theBBC

was

Terry

Wogan. Mr Wogan is

an Irishman

who

had

become

Britain’s

most

populär

television

talk-show host during

the

1980s.

Towards the

end

of

the programme, with the

voting

for

the

songs

nearly

complete,

it became

clear that

the

contest (in

which

European

countries compete to present the

best

new populär

song)

was going

to be

won

by

either

Ireland or

the

United

Kingdom.

Within

a

five-

minute

period,

Mr Wogan could be heard using

the pronouns

‘we’ and ‘us’

several

times;

sometimes he

meant

the

UK

and sometimes

he

meant

Ireland!

►

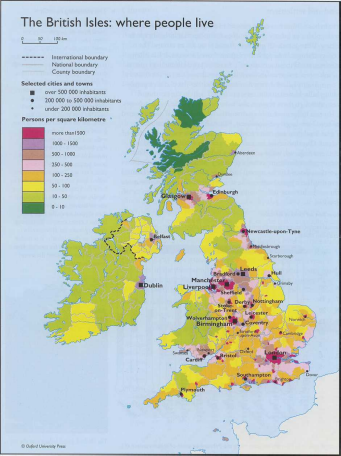

Populations

in 1995

England 48.9 million

Scotland 5.1 million

Wales 2.9 million

Northern

ireland 1.6 million

UK

total 58,6 million

These

figures are estimates provided by the Government Actuary ‘s

Department of the UK, hased on the t

9 91 Census.

It

is expected that the total population of Britain will continue to

rise by very small amounts until around the year 202$.

►

The

Union Jack

The

Union Jack is the national flag of the UK. It is a combination of

the cross of S t George, the cross of St Andrew and the cross of St

Patrick (D> Identifying Symbols of the four nations).

The

Union Jack

QUESTIONS

-

Think

of

the

most well-known

symbols and tokens

of

nationality

in your

country.

Are they the

same

types

of

real-life objects (e.g.

plants, clothes)

that

are

used in

Britain? -

In

1970, the

BBC

showed

a

series

of programmes

about the history of

the British Empire.

Before the series started,

they

advertised it.

The advertisement

mentioned ‘England’s

history’. Within

a

few

hours,

the BBC had received thou- sands

of

angry

ealls

of protest

and

it

was forced

to

make

an

apology.

Who do you think the

angry callers were?

Why

did the

BBC

apologize? -

In

1991, UEFA

(the

Union

of

European Football Associations) introduced

a

new

regulation. This limited

the

number

of

foreign players

who

were allowed

to

play

for

a football

club in European

competitions. For example, a German club team

could

have

only

a

certain number

of

players in

it who

were

not

German.

Under

the

new regulation

a player

in

the

Liverpool

team, Ian

Rush, was classified as ‘foreign’, even though

he

was

born only

twenty

miles

from Liverpool and had lived

in

the same area all

his life.

Many other players

of

English

club

teams

found

themselves

in

the

same

position.

Many people

in

England

thought that

this was ridiculous. How did

this

happen?

Do

you think

it

was ridiculous?

4

The

dominance

of

England in Britain is reflected in the

Organization

of

the government.

There are

ministers for Scotland, Wales

and

Northern

Ireland, but there is

no

minister

for

England,

Do

you

think

this

is

good for

the

people of the

other

British nations (they

have

special

attention

and recognition

of their distinct identity)

or is it bad (it gives them

a kind of second-class, colonial

Status)? y Are there

any

distinct

national loyalties

in

your

country (or

are

they better described as

regional

loyalties)?

If

so,

is the relationship

between

the

‘nations’

in

any way

similar to that between

the

nations in

Britain?

If

not,

can

you think

of

any

other countries

where such loyalties

exist? Do

these

loyalties

cause

problems

in those

countries?

SUGGESTIONS

Britain,

an Ofiicial

Handbook (HMSO) is published

annually

and is pre- pared

by the

Central Office of Information. It includes

facts

and figures

on aspects

of British life

such

as politics and law,

economic and

social

affairs, arts

and sport.

Dictionary

of Britain by Adrian Room (Oxford University Press) is an

alphabetical

guide

to

well-known

British organizations,

people,

events, traditions and other

aspects oflife in Britain.

Prehistory

Two

thousand years

ago

there was an

Iron

Age Celtic

cnlture

throughout

the British

Isles. It

seems

that the

Celts, who had been arriving

from Europe from the

eighth

Century BC onwards, intermingled with the

peoples

who were already there. We know that religious sites

that

had been built long

before

the arrival of

the

Celts continued to be used

in

the

Celtic

period.

For

people in

Britain today,

the chief

significance

of the prehistoric period (for which no

written

records exist) is

its

sense

of

mystery.

This

sense

finds its

focus

most

easily in the astonishing monumental architecture of this period,

the remains of which exist throughout

the

country. Wiltshire, in

south-western

England,

has

two spectacular

examples:

Silbury

Hill, the

largest burial mound in Europe, and Stonehenge (e>

Stonehenge). Such places have a special importance for anyone

interested

in

the

cultural

and

religious

practices of prehistoric Britain. We know very

little about

these practices, but there are some organizations

today

(for example, the

Order

of

Bards,

Ovales and Druids —

a

small group of eccentric intellectuals

and

mystics) who base their beliefs on them.

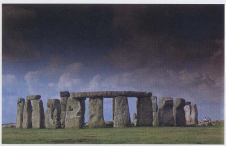

Stonehenge

Stonehenge

Stonehenge

was built on Salisbury Plain some time between 3030 and 2300 BC. It

is one of the most famous and mysterious archaeological sites in the

world. One of its mysteries is how it was ever built at all with the

technology of the time (the stones corae from over 200 miles away in

Wales). Another is its purpose. It appears to function as a kind of

astronomical clock and we know it was used by the Druids for cere-

monies marking the passing of the seasons. It has always exeried a

fas- cination on the British imagination, and appears in a number of

novels, such as Thomas Hardy’sTess of the D’Urbevilles,

These

days Stonehenge is not only of interest to lourists, but is also a

gathering point for certain minority gröups such as hippies and

‘New Age Travellers’ (see chapter 13). It is now fenced off to

protect it from damage.

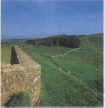

Hadrian’s

Wall

Hadrian’s

Walf

Hadrian’s

Wall was buill by the Romans in the second Century across the

northern border of their province of Britannia (along nearly the

same line as the present English- Scottish border) in order to

protect their territory from attacks by the Scots and the Picts.

The

Roman

province

of

Britannia

covered

most

of

present-day England

and

Wales. The

Romans

imposed

their own

way oflife

and

culture,

making

use

of

the existing

Celtic aristocracy

to govern and encouraging this

ruling

dass

to

adopt

Roman dress and

the

Roman language (Latin). They

exerted

an

influence, without

actually

governing

there, over

only the

Southern

part

of

Scotland.

It

was during

this

time

that a Celtic

tribe called

the

Scots migrated from Ireland

to

ScoLland,

where

they

became

allies

of

the Picts (another Celtic

tribe)

and

opponents

of the Romans.

This division

of the Celts

into

those

who experienced

direct

Roman

rule (the Britons

in

England

and

Wales)

and

those

who

did not

(the

Gaels

in

Ireland

and Scotland)

rnay help

io explain

the development of

two

distinct branches of the Celtic group

of languages.

The

remarkable

thing about

the Romans

is that,

despite

their long occupation

of Britain, they

left

very liitle

behind.

To many

other

parts

of Europe

they

bequeathed a

System of

law

and

administration

which

forms

the basis of

the

modern

System

and

a language

which

developed into

the modern Romance

family

of

languages. In

Britain,

they left

neither.

Moreover, most

of their

villas, balhs

and

temples,

their impressive

network

of roads, and

the

cities

they

founded, including

Londinium (London),

were

soon destroyed or

feil

into disrepair.

Almost

the önly lasting reminder

of

their

presence are place-names

like Chester, Lancaster and

Gloucester,

which include

variants

of

the Roman word

castra

(a

military camp).

The

Germanic invasions (410—1066)

One

reason

why

Roman

Britannia

disappeared so quickly

is

probably

that its influence

was largely confined to the towns.

In

the

country- side,

where

most people

lived,

farming

methods had

remained

unchanged

and Celtic speech

continued

to be

dominant.

The

Roman occupation

had

been

a

matter of colonial

control

radier

than

large-scale settlement.

But,

during

the fifth

Century, a

number

of

tribes from the north-western European

mainland

invaded

and

settled

in

large

numbers.

Two of

these

tribes were

the

Angles and

Some

important dates in British history

ssBC1

The

Roman general Julius Caesar lands in Britain widi an expeditionary

force, wins a battle and lcaves. The first ‘date’ in populär

British history.

ad

43

The

Romans come to stay.

61

Queen

Boudicca (or Boadicea) of the Iceni tribe leads a bloody revolt

against the Roman occupation. It is suppressed. There is a statue of

Boadicea, made in the nineteenth Century, outside the Houses of

Parliament. This has helped to keep die memory of her alive.

King

Artflur, Queen Guinevere and one of the knights of the round tabfe,

from the film ‘Camelot1

ihe

Saxons. These

Anglo-Saxons

soon

had the

south-east of

the

country

in their

grasp. In

the

west

of

the country

their

advance was temporarily halted by an

army

of (Celtic)

Britons under the command

of

the

legendary King Arthur

(i>

King

Arthur).

Nevertheless, by the

end

of

the sixth

Century,

they

and

their

way

oflife predominated in

nearly

all

of England and

in

parts of Southern

Scotland. The

Celtic

Britons

were

either Saxonized or

driven

westwards, where

their

culture

and language survived

in

south-west

Scotland,

Wales

and. Cornwall.

The

Anglo-Saxons

had

little use

for towns

and

cities.

But

they

had a great

effect

on

the

countryside,

where they

introduced new

fatming metlrods and

founded

the thousands

of

self-sufficient vil-

lages which formed the

basis of

English society

for

the next

thousand or

so years.

The

Anglo-Saxons

were

pagan when they came

to

Britain.

Chris-

tianity

spread

throughout

Britain

from

two

different

directions during

the sixth and

seventh centuries. It came

directly from Rome

when St Augustine

arrived in 597

and established

his headquarters at

Canterbury

in

the

south-east of

England. It

had

already been inLro-

duced into Scotland

and

northern

England

from Ireland, which

had

become

Christian more than

15

o

years

earlier.

Although Roman Christianity

eventually Look over

the whole

of

the British

Isles, the Celtic rnodel

persisted

in Scotland and Ireland for

several

hundred years. It was less

centrally organized,

and

had

less need for a strong

monarchy to

support

it.

This

partly

explains

why

both

secular

and

religious

power in

these

two countries continued

to he

both

more

locally

based

and

less

secure than it

was eise where in Britain

throughout the

medieval period.

Britain

experienced

another

wave

of

Germanic

invasions

in

the

eighth

Century.

These invaders,

known

as

Vikings,

Norsemen or

Danes, came

from Scandinavia.

In the

ninth Century they conquered and

settled

the

extreme

north and

west

of

Scotland,

and

also

some Coastal

regions of

Ireland.

Their

conquest of

England

was halted

when

they were

defeated

by

King Alfred

of the Saxon kingdom

of

Wessex

(•:

• King

Alfred).

This

resulted

in

an

agreement

which

divided England

between

Wessex,

in the

soutli

and

west,

and

the

‘Danelaw’

in

the

north and east.

►

King

Arthur

King

Arthur provides a wonderful example of the distortiqns of populär

history. In folklore and rnytli he is a great English liero, and he

and his knights of the round table are regarded as the perfect

example of medieval nobility and chivalry. In fact, he lived long

before medieval Limes and was a Romanized Celt trying to hold back

the advances of the Anglo-Saxons — the very people who beeatne

‘the English’!

410

The

Romans leave Britain.

S

97

St

Augustine arrives in England.

793

The

great monastery on the island of Lindisfarne in northeast England is

destroyed by Vikings and its monks killea.

878

The

Peace of Edington partitions England between the Saxons, led by King

Alfred, and the Dahes.

973

Edgar,

grandson of Alfred, becomes ktng of all England.

-

King

Alfred

King

Alfred was not only an able warrior but also a dedicated scholar and

a wise ruler. He is known as ‘Alfred the Great’ — the only

monarch in English history to be given this title. He is also

popularly known for the story of the öurning of the cakes.

While

Alfred was wandering around his country organizing resistance

to the Viking invaders, he travelled in disguise. On one occa- sion,

he stopped at a woman’s house. The woman asked him to watch some

cakes that were cooking to see that they did not bum, while she went

off to get food. Alfred became lost in thought and the cakes burned.

When the woman retumed, she shomed angrily at Alfred and sent him

away. Alfred

never told her that he was her king.

-

1066

This

is the most famous date in English history, On 14 October 1066 an

invading army from Normandy defeated the English at the Battle

of Hastings. The battle was close and extremely bloody. At the end

of it, most of the best warriors in England were dead, including

their leader, King Harold. O11 Christmas day that year the Norman

leader, Duke William of Normandy, was crowned king of England. He äs

known in populär history as ‘William the Conqueror’, The date is

remembered for being the last time that England was successfully

invaded.

However,

the cultural

differences between

Anglo-Saxons and

Danes were comparatively

small.

They

led roughly

the same

way

of

life

and spoke two

varieties

of

the same Germanic

tongue

(which combined

to

form

the basis of

modern

English).

Moreover, the Danes soon converted

to Christianity. These

similarities made

political

uni- fication easier,

and

by the

end

of

the

tenth

Century England was

one king dom

with

a

Germanic

culture throughout.

Most

of modern-day

Scotland was

also

united by this

time, at least in

name,

in

a

(Celtic)

Gaelic

kingdom.

The

medieval period (1066-1485)

The

successfulNorman

invasionof

England in

1066

(t> 1066)

brought Britain into the

mainstream of Western

European culture. Previously most links

had

been with Scandinavia.

Only

in

Scotland

did this link

survive; the western

isles (until the

thirteenth

Century) and

the

northern

islands (until

the

fifteenth

Century) remaining under

the

control

of Scandinavian kings.

Throughout this

period

the

English

kings

also ruled

over areas

of

land

on

the

continent and

were

often

at

war

with the French

kings in

disputes over

ownership.

Unlike

the

Germanic invasions,

the

Norman

invasion was small- scale. There

was no

such thing

as a Norman

village

or a

Norman

area

of settlement. Instead,

the Norman

soldiers

who had been

part of

the invading

army were

given the

ownership

of land

—

and

of the people

living

on

it.

A strict feudal system

was imposed. Great

nobles,

or barons,

were

responsible directly to the

king;

lesser lords,

each

owing a village,

were

directly responsible to

a baron.

Under

them

were

the peasants, tied by a strict system

of mutual duties

and

obligations

to

the

local

lord,

and

forbidden to travel without his permission. The peasants

were

the

English-speaking

Saxons.

The

lords

and

the barons were the

French-speaking

Normans. This was the beginning

of

the

English

dass

system (>

Language

and dass).

The

strong System of government

which

the

Normans introduced meant

that

the Anglo-Norman

kingdom was easily

the

most

power- ful

political

force in

the

British

Isles. Not surprisingly therefore, the

authority of

the English

monarch gradually

extended to

other

parts

of

these islands

in

the

next

250

years.

By the

end of

the thirteenth Century,

a

large

part of eastern Ireland was

controlled by Anglo- Norman

lords in the name of the

English king and

the whole

of Wales

to66

The

Battle of Hastings ([> 1066) 1086

King

William’s officials complete the Domesday Book, a very detailed,

village-by-village record of the people and their possessions

throughout his kingdom.

was

under

his direct

rule

(at

which

time

the

custom

of naming

the

monarch’s

eldest son the

‘Prince

ofWales’ began). Scotland managed to remain politically

independent in

the

medieval period, but was obliged to

fighi occasional wars

to do so.

The

cultural story of this

period is different. Two hundred and fifty years after

the Norman Conquest,

it was

a

Germanic language

(Middle English) and not the

Norman

(French) language

which had become

the dominant one in

all

classes of

society in England. Fur-

thermore, it

was

the

Anglo-Saxon concept

of

common law, and not

Roman law, which formed

the

basis

of the legal

system.

Despitc

English rule, northern

and

central

Wales

was

never settled

in

great

numbers by Saxon or Norman.

As a result the

(Celtic)

Welsh

language and culture remained

strong. Eisteddfods,

national

festivals

of

Welsh

song

and

poetry, continued throughout

the medieval period and

still take

place

today. The Anglo-Norman lords of eastern Ireland remained

loyal

to the English

king but,

despite laws to

the

contrary, mostly

adopted the

Gaelic language and customs.

The

political

independence

of

Scotland

did not prevent a

gradual switch to

English

language

and customs in the lowland (southern) part of

the

country.

First,

the Anglo-Saxon element here was strengthened

by

the arrival

of many Saxon

aristocrats fleeing the

Norman conquest of England. Second,

the Celtic kings saw that the adoption

of

an Anglo-Norman

style of

government would

strengthen royal power. By

the

end of this period

a cultural split had developed

between the

lowlands,

where the

way oflife

and

language

was

similar

to that in England,

and

the

highlands, where

(Celtic) Gaelic culture and language prevailed —

and

where, because of

the mountainous landscape,

the authority of the

king

was

hard

to enforce.

It

was

in

this

period

that Parliament began

its gradual evolutiön into the

democratic body which

it is today.

The

word ‘parliament’,

which

comes

from the French

word

parier (to speak),

was

first

used

in England

in

the

thirteenth

Century

to

describe

an

assembly of

nobles

called

togetlier by

the

king. In

i

295,

the Model Parliament set the

pattern

for the future

by including

elected representatives from urban and

rural

areas.

-

Language

and dass

The

existence of two words for the larger farm animals in modern English

is a result of the dass divi- sions established by the Norman

conquest. There are the words for the living animals (e.g. cow, pig,

sheep), which have their origins in Anglo-Saxon, and the words for

the meat front the animals (e.g. becf,

pork, mutton), which have their origins in the French language that

the Normans brought to England. Only die Normans normally ate meat;

the poor Anglo-Saxon peasants did not!

-

Robin

Hood

Robin

Hood is a legendary folk hero. King Richard 1

(t 1 89-99) spent most of his reign fighting in the Crusades

(the wars between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East). While

Richard was away, England was governed by his brother John, who was

unpopulär because of all the taxes he imposed. According to legend,

Robin Hood lived with his band of‘merry men’ in Sherwood Forest

outside Nottingham, stealing from the rieh and giving to the poor.

He was consiamly hunted by the local sheriff (the royal represema-

tive) but was never captured.

1170

The

murder of Thomas Recket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, by soldiers

of King Henry II. Becket (also known as Thomas ä Becket) was made a

saint and his grave was visited by pilgrims for hundreds of years.

The Canterltury Tales, written by Geoffrey Chaucer in the fourteenth

Century, recounts the stories told by a fictional group of pilgrims

on their way to Canterbury.

11

71

The

Norman baron known as Strongbow and his followers settle in Ireland.

12

if

An

alliance of aristocracy, Church and merchants force King John to

agree to the Magna Carta (Great Charter), a docu- ment in which the

king agrees to follow certain rules of government. In fact, neither

John nor his successors entirely followed Üiem, but Magna Caita

is remembered as the first time a monarch agreed in writing to abide

by formal procedures.

-

The

Wars of the Roses

During

the fifteenth Century the throne of England was claimed by

representatives of two rival groups. The power of the greatest

nobles, who had their own private axmies, meant. that constant

challenges to the position of the monarch were possible. The

Lancastrians, whose symbol was a red rose, supported the descendants

of the Duke of Lancaster, and the Yorkists, whose symbol was a white

rose, supported the descendants of the Duke of York. The

struggle for power led to the ‘Wars of the Roses1

between 1435 and 148 p. They ended when Henry VII defeated and

killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field and were followed

by an era of stability and strong government which was wel- comed by

those weakened and impoverished by decades of war.

-

Off

with his head!

Being

an important person in the sixteenth Century was not a safe position

to be in. The Tudor monarchs were disloyal to their officials

and merciless to any nobles who opposed them. More than half of the