From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Cutlery designed by architect and designer Zaha Hadid (2007). The slightly oblique end part of the fork and the spoons, as well as the knife handle, are examples of designing for both aesthetic form and practical function.

Early concept design sketches by the architect Erling Viksjø, exploring the relationships between existing and proposed new buildings.

A design is a plan or specification for the construction of an object or system or for the implementation of an activity or process or the result of that plan or specification in the form of a prototype, product, or process. The verb to design expresses the process of developing a design. In some cases, the direct construction of an object without an explicit prior plan (such as in craftwork, some engineering, coding, and graphic design) may also be considered to be a design activity. The design usually has to satisfy certain goals and constraints; may take into account aesthetic, functional, economic, or socio-political considerations; and is expected to interact with a certain environment. Typical examples of designs include architectural and engineering drawings, circuit diagrams, sewing patterns and less tangible artefacts such as business process models.[1]

Designing[edit]

People who produce designs are called designers. The term ‘designer’ generally refers to someone who works professionally in one of the various design areas. Within the professions, the word ‘designer’ is generally qualified by the area of practice (so one may be, for example, a fashion designer, a product designer, a web designer, or an interior designer), but it can also designate others such as architects and engineers (see below: Types of designing). A designer’s sequence of activities to produce a design is called a design process, using design thinking and possibly design methods. The process of creating a design can be brief (a quick sketch) or lengthy and complicated, involving considerable research, negotiation, reflection, modeling, interactive adjustment, and re-design.

Designing is also a widespread activity outside of the professions, done by more people than just those formally recognised as designers. In his influential book The Sciences of the Artificial the interdisciplinary scientist Herbert A. Simon proposed that «Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones».[2] And according to the design researcher Nigel Cross «Everyone can – and does – design», and «Design ability is something that everyone has, to some extent, because it is embedded in our brains as a natural cognitive function».[3]

History of design[edit]

Study of the history of design is complicated by varying interpretations of what constitutes ‘designing’. Many design historians, such as John Heskett, start with the Industrial Revolution and the development of mass production.[4] Others subscribe to conceptions of design that include pre-industrial objects and artefacts, beginning their narratives of design in prehistorical times.[5] Originally situated within art history, the historical development of the discipline of design history coalesced in the 1970s, as interested academics worked to recognize design as a separate and legitimate target for historical research.[6] Early influential design historians include German-British art historian Nikolaus Pevsner and Swiss historian and architecture critic Sigfried Giedion.

Design education[edit]

Institutions for design education date back to the nineteenth century. The Norwegian National Academy of Craft and Art Industry was founded in 1818, followed by the United Kingdom’s Government School of Design (1837), Konstfack in Sweden (1844), and Rhode Island School of Design in the United States (1877). The German art and design school Bauhaus, founded in 1919, greatly influenced modern design education.[7]

Design education covers the teaching of theory, knowledge and values in the design of products, services and environments, and focusses on the development of both particular and general skills for designing. It is primarily orientated to preparing students for professional design practice, and based around project work and studio or atelier teaching methods.

There are also broader forms of higher education in design studies and design thinking, and design also features as a part of general education, for example within Design and Technology. The development of design in general education in the 1970s led to a need to identify fundamental aspects of ‘designerly’ ways of knowing, thinking and acting, and hence to the establishment of design as a distinct discipline of study.[8]

Design process[edit]

Substantial disagreement exists concerning how designers in many fields, whether amateur or professional, alone or in teams, produce designs.[9] Design researchers Dorst and Dijkhuis acknowledge that «there are many ways of describing design processes», and compare and contrast two dominant but different views of the design process: as a rational problem solving process and as a process of reflection-in-action. They suggested that these two paradigms «represent two fundamentally different ways of looking at the world – positivism and constructionism».[10] The paradigms may reflect differing views of how designing should be done and how it actually is done, and they both have a variety of names. The problem-solving view has been called «the rational model»,[11] «technical rationality»[12] and «the reason-centric perspective».[13] The alternative view has been called «reflection-in-action»,[12] «co-evolution»,[14] and «the action-centric perspective».[13]

Rational model[edit]

The rational model was independently developed by Herbert A. Simon,[15][16] an American scientist, and two German engineering design theorists, Gerhard Pahl and Wolfgang Beitz.[17] It posits that:

- Designers attempt to optimize a design candidate for known constraints and objectives.

- The design process is plan-driven.

- The design process is understood in terms of a discrete sequence of stages.

The rational model is based on a rationalist philosophy[11] and underlies the waterfall model,[18] systems development life cycle,[19] and much of the engineering design literature.[20] According to the rationalist philosophy, design is informed by research and knowledge in a predictable and controlled manner.[21]

Typical stages consistent with the rational model include the following:[22]

- Pre-production design

- Design brief – initial statement of intended outcome.

- Analysis – analysis of design goals.

- Research – investigating similar design solutions in the field or related topics.

- Specification – specifying requirements of a design solution for a product (product design specification)[23] or service.

- Problem solving – conceptualizing and documenting design solutions.

- Presentation – presenting design solutions.

- Design during production.

- Development – continuation and improvement of a designed solution.

- Product testing – in situ testing of a designed solution.

- Post-production design feedback for future designs.

- Implementation – introducing the designed solution into the environment.

- Evaluation and conclusion – summary of process and results, including constructive criticism and suggestions for future improvements.

- Redesign – any or all stages in the design process repeated (with corrections made) at any time before, during, or after production.

Each stage has many associated best practices.[24]

Criticism of the rational model[edit]

The rational model has been widely criticized on two primary grounds:

- Designers do not work this way – extensive empirical evidence has demonstrated that designers do not act as the rational model suggests.[12][13][25]

- Unrealistic assumptions – goals are often unknown when a design project begins, and the requirements and constraints continue to change.[11][26]

Action-centric model[edit]

The action-centric perspective is a label given to a collection of interrelated concepts, which are antithetical to the rational model.[13] It posits that:

- Designers use creativity and emotion to generate design candidates.

- The design process is improvised.

- No universal sequence of stages is apparent – analysis, design and implementation are contemporary and inextricably linked.[13]

The action-centric perspective is based on an empiricist philosophy and broadly consistent with the agile approach[27] and methodical development.[28] Substantial empirical evidence supports the veracity of this perspective in describing the actions of real designers.[25] Like the rational model, the action-centric model sees design as informed by research and knowledge.[29]

At least two views of design activity are consistent with the action-centric perspective. Both involve these three basic activities:

- In the reflection-in-action paradigm, designers alternate between «framing», «making moves», and «evaluating moves». «Framing» refers to conceptualizing the problem, i.e., defining goals and objectives. A «move» is a tentative design decision. The evaluation process may lead to further moves in the design.[12]

- In the sensemaking–coevolution–implementation framework, designers alternate between its three titular activities. Sensemaking includes both framing and evaluating moves. Implementation is the process of constructing the design object. Coevolution is «the process where the design agent simultaneously refines its mental picture of the design object based on its mental picture of the context, and vice versa».[13]

The concept of the design cycle is understood as a circular time structure,[30] which may start with the thinking of an idea, then expressing it by the use of visual or verbal means of communication (design tools), the sharing and perceiving of the expressed idea, and finally starting a new cycle with the critical rethinking of the perceived idea. Anderson points out that this concept emphasizes the importance of the means of expression, which at the same time are means of perception of any design ideas.[31]

Philosophies[edit]

Philosophy of design is the study of definitions of design, and the assumptions, foundations, and implications of design. There are also many informal ‘philosophies’ for guiding design such as personal values or preferred approaches.

Approaches to design[edit]

Some of these values and approaches include:

- Critical design uses designed artifacts as an embodied critique or commentary on existing values, morals, and practices in a culture.

- Ecological design is a design approach that prioritizes the consideration of the environmental impacts of a product or service, over its whole lifecycle.[32][33]

- Participatory design (originally co-operative design, now often co-design) is the practice of collective creativity to design, attempting to actively involve all stakeholders (e.g. employees, partners, customers, citizens, end-users) in the design process to help ensure the result meets their needs and is usable.[34]

- Scientific design refers to industrialised design based on scientific knowledge.[35] Science can be used to study the effects and need for a potential or existing product in general and to design products that are based on scientific knowledge. For instance, a scientific design of face masks for COVID-19 mitigation may be based on investigations of filtration performance, mitigation performance,[36][37] thermal comfort, biodegradability and flow resistance.[38][39]

- Service design designing or organizing the experience around a product and the service associated with a product’s use.

- Sociotechnical system design, a philosophy and tools for participative designing of work arrangements and supporting processes – for organizational purpose, quality, safety, economics, and customer requirements in core work processes, the quality of peoples experience at work, and the needs of society.

- Transgenerational design, the practice of making products and environments compatible with those physical and sensory impairments associated with human aging and which limit major activities of daily living.

- User-centered design, which focuses on the needs, wants, and limitations of the end-user of the designed artifact. One aspect of user-centered design is ergonomics.

Relationship with the arts[edit]

The boundaries between art and design are blurry, largely due to a range of applications both for the term ‘art’ and the term ‘design’. Applied arts can include industrial design, graphic design, fashion design, and the decorative arts which traditionally includes craft objects. In graphic arts (2D image making that ranges from photography to illustration), the distinction is often made between fine art and commercial art, based on the context within which the work is produced and how it is traded.

Types of designing[edit]

- Applied arts

- Architecture

- Automotive design

- Biological design

- Cartographic or map design

- Configuration design

- Communication design

- Costume design

- Design management

- Engineering design

- Experience design

- Fashion design

- Floral design

- Game design

- Graphic design

- Information architecture

- Information design

- Industrial design

- Instructional design

- Interaction design

- Interior design

- Landscape architecture

- Lighting design

- Modular design

- Motion graphic design

- Organization design

- Process design

- Product design

- Production design

- Property design

- Scenic design

- Service design

- Social design

- Software design

- Sound design

- Spatial design

- Strategic design

- Systems architecture

- Systems design

- Systems modeling

- Urban design

- User experience design

- User interface design

- Vexillography

- Web design

See also[edit]

- Design-based learning

- Design methods

- Design research

- Design science

- Design theory

- Design thinking

- Design museums

- Design prototyping

- Evidence-based design

- Visual design elements and principles

- List of design awards

References[edit]

- ^ Dictionary meanings in the Cambridge Dictionary of American English, at Dictionary.com (esp. meanings 1–5 and 7–8) and at AskOxford (especially verbs).

- ^ Simon, Herbert A. (1969). The Sciences of the Artificial (first ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: M.I.T. Press. p. 54.

- ^ Cross, Nigel (2011). Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Berg. pp. 3 & 140. ISBN 978-1-84788-846-4.

- ^ Heskett, John (1963) Industrial Design. Thames & Hudson.

- ^ Huppatz, D. J. (2015). «Globalizing Design History and Global Design History». Journal of Design History. 28 (2): 182–202. doi:10.1093/jdh/epv002. ISSN 0952-4649. JSTOR 43831904.

- ^ Margolin, Victor (April 1, 2009). «Design in History». Design Issues. 25 (2): 94–105. doi:10.1162/desi.2009.25.2.94. eISSN 1531-4790. ISSN 0747-9360. S2CID 57562456.

- ^ Naylor, Gillian (1985). The Bauhaus Reassessed. Herbert Press. ISBN 0906969301.

- ^ Cross, Nigel (1982). «Design as a Discipline: Designerly Ways of Knowing». Design Studies. 3 (4): 221–227. doi:10.1016/0142-694X(82)90040-0.

- ^ Coyne, Richard (1990). «Logic of design actions». Knowledge-Based Systems. 3 (4): 242–257. doi:10.1016/0950-7051(90)90103-o. ISSN 0950-7051. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- ^ Dorst, Kees; Dijkhuis, Judith (1995). «Comparing paradigms for describing design activity». Design Studies. 16 (2): 261–274. doi:10.1016/0142-694X(94)00012-3.

- ^ a b c Brooks, F. P (2010). The Design of Design: Essays from a Computer Scientist. Pearson Education. ISBN 9780321702067.

- ^ a b c d Schön, D.A. (1983) The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, Basic Books, USA. ISBN 978-0465068784

- ^ a b c d e f Ralph, P. (2010) «Comparing two software design process theories». International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology (DESRIST 2010), Springer, St. Gallen, Switzerland, pp. 139–153. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13335-0_10.

- ^ Dorst, Kees; Cross, Nigel (2001). «Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem–solution» (PDF). Design Studies. 22 (5): 425–437. doi:10.1016/S0142-694X(01)00009-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ Newell, A., and Simon, H. (1972) Human problem solving, Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- ^ Simon, H.A. (1996) The sciences of the artificial Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. p. 111. ISBN 0-262-69191-4.

- ^ Pahl, G., and Beitz, W. (1996) Engineering design: A systematic approach Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, Springer-Verlag, London. ISBN 3-540-19917-9.

- ^ Royce, W.W. (1970) «Managing the development of large software systems: Concepts and techniques,» Archived 2020-10-02 at the Wayback Machine Proceedings of Wescon.

- ^ Bourque, P., and Dupuis, R. (eds.) (2004) Guide to the software engineering body of knowledge Archived 2012-01-24 at the Wayback Machine (SWEBOK). IEEE Computer Society Press, ISBN 0-7695-2330-7.

- ^ Pahl, G., Beitz, W., Feldhusen, J., and Grote, K.-H. (2007 ) Engineering design: A systematic approach Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, (3rd ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 1-84628-318-3.

- ^ Mielnik, Anna. Under the power of reason. Krakow University of Technology. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ Condrea, Ionut; Botezatu, C.; Slătineanu, L.; Oroian, B. (February 2021). «Elaboration of the initial requirements in the design activities». IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering. 1037 (1): 012002. Bibcode:2021MS&E.1037a2002S. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/1037/1/012002. S2CID 234019940.

- ^ Cross, N., (2006). T211 Design and Designing: Block 2, p. 99. Milton Keynes: The Open University.

- ^ Ullman, David G. (2009) The Mechanical Design Process, Mc Graw Hill, 4th edition ISBN 0-07-297574-1

- ^ a b Cross, N., Dorst, K., and Roozenburg, N. (1992) Research in design thinking, Delft University Press, Delft. ISBN 90-6275-796-0.

- ^ McCracken, D.D.; Jackson, M.A. (1982). «Life cycle concept considered harmful». ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes. 7 (2): 29–32. doi:10.1145/1005937.1005943. S2CID 9323694. Archived from the original on 2012-08-12. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Beck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith, J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin, R.C., Mellor, S., Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., and Thomas, D. (2001) Manifesto for agile software development Archived 2021-03-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Truex, D.; Baskerville, R.; and Travis, J. (2000). «Amethodical systems development: The deferred meaning of systems development methods». Accounting, Management and Information Technologies. 10 (1): 53–79. doi:10.1016/S0959-8022(99)00009-0.

- ^ Faste, Trygve; Faste, Haakon (2012-08-15). «Demystifying «design research»: design is not research, research is design» (PDF). Industrial Designers Society of America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ Fischer, Thomas «Design Enigma. A typographical metaphor for enigmatic processes, including designing», in: T. Fischer, K. De Biswas, J.J. Ham, R. Naka, W.X. Huang, Beyond Codes and Pixels: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia, p. 686

- ^ Anderson, Jane (2011) Architectural Design, Basics Architecture 03, Lausanne, AVA academia, p. 40. ISBN 978-2-940411-26-9.

- ^ Kanaani, Mitra (2023). The Routledge companion to ecological design thinking : healthful ecotopian visions for architecture and urbanism. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-003-18318-1. OCLC 1332789897. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ van der Ryn, Sim; Cowan, Stuart (1996). An Introduction to Ecological Design. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726-140-1.

- ^ «Co-creation and the new landscape of design» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ Cross, Nigel (1 June 1993). «Science and design methodology: A review». Research in Engineering Design. 5 (2): 63–69. doi:10.1007/BF02032575. ISSN 1435-6066. S2CID 110223861. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ «Face shields, masks with valves ineffective against COVID-19 spread: study». phys.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Verma, Siddhartha; Dhanak, Manhar; Frankenfield, John (1 September 2020). «Visualizing droplet dispersal for face shields and masks with exhalation valves». Physics of Fluids. 32 (9): 091701. arXiv:2008.00125. Bibcode:2020PhFl…32i1701V. doi:10.1063/5.0022968. ISSN 1070-6631. PMC 7497716. PMID 32952381.

- ^ «Face masks slow spread of COVID-19; types of masks, length of use matter». phys.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Kumar, Sanjay; Lee, Heow Pueh (李孝培) (1 November 2020). «The perspective of fluid flow behavior of respiratory droplets and aerosols through the facemasks in context of SARS-CoV-2». Physics of Fluids. 32 (11): 111301. arXiv:2010.06385. Bibcode:2020PhFl…32k1301K. doi:10.1063/5.0029767. ISSN 1070-6631. PMC 7713871. PMID 33281434.

Further reading[edit]

- Raizman, David Seth (12 November 2003). The History of Modern Design. Pearson. ISBN 978-0131830400.

He says that, even though in practice inferring design is the first step in identifying an intelligent agent, taken by itself _design does not require that such an agent be posited. ❋ Unknown (2006)

Every fragment of life has its completing part somewhere, given its place in the scheme of the universe by intricate design — always by _design! ❋ Anonymous (N/A)

«Professor Haeckel maintains,» says Mr. Wallace, «_that the struggle for existence in nature evolves new forms without design, just as the will of man produces new varieties in cultivation with design_.» ❋ Samuel Butler (1868)

The inference of intelligence from marks of design in nature is not one of analogy, but of strict and proper _induction_; and accordingly we must either deny that there are marks of _design_ in nature, thereby discarding the _analogy_, or do violence to our own reason by resisting the fundamental law of causality, thereby discarding the inductive inference. ❋ James Buchanan (1837)

It may be how the Nu Gundam is a very solid design in the first place, making the converted Rebornnu Gundam looking more attractive now than the original Reborns Gundam, in Gundam 00 style mecha design~ ❋ Unknown (2010)

Harness PLM for CATIA, transforms the wiring diagrams to harness design• process of designing electrical harnesses The topology modules in SEE Electrical by leveraging the power of CATIA to For more information: www. harness-design.com Harness allow users to generate and significantly reduce cycle times. ❋ Unknown (2009)

My reverend friend is wrong in supposing that I admit DESIGN, and yet refuse to admit the force of the _design argument_, «On the supposition, then, that _law and order_ are manifestations of _design_, the design argument might be valid and conclusive: but» _no conceivable order_ «could prove the existence of God; why? ❋ James Buchanan (1837)

This design is an exquisite example of modern design, but unfortunately it completely ignores the human factor in design. ❋ Unknown (2009)

It’s not often, after all, that a «new» whisky is a painstaking recreation, from flavor down to the label design, of a whisky that was buried in ice for a full century by the great Antarctic explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton. ❋ Tony Sachs (2011)

In response to this work, one of IDEO’s founders coined the term «design thinking» to represent an approach to problem solving that moved away from the analytical and rational and evoked a more «human-centered» outlook. ❋ Dylan Kendall (2011)

Other wineries have used crowd sourcing for things like naming a wine or choosing a label design, but not to decide on things like which strain of yeast or how far apart the rollers are on the grape crusher. ❋ Mary Orlin (2011)

Poetry in design is explored by studying the transformative properties of the wind and applying them to a common piece of furniture that typically does not communicate above a functional level. ❋ Unknown (2009)

ÂOther wineries have used crowd sourcing for things like naming a wine or choosing a label design, but not to decide on things like which strain of yeast or how far apart the rollers are on the grape crusher. ❋ Mary Orlin (2011)

myself and [countless] other graduates Australia-wide. ❋ Dj (2003)

i just [got to] [buy] these new [designer] …. ❋ Zohar David (2005)

Design is an aesthetic [delineation] of materialism. In [liminism] it can also be a «materialistic» a-lineation of [aestheticism]. ❋ Sandrashine (2019)

that’s [the most] [wacked] design i’ve [seen]. ❋ VEA (2003)

verb: He was [designated] as [prime minister]

adjective: The Director [designate] ❋ DieKry01 (2010)

[Abu], I’m [touching cloth] here my friend, where is the [designated] shitting area? ❋ ScatTalk (2016)

«Our [company] uses a Designeering [method]»

» You’re [such a] Designeer» ❋ Perpetualtikkaa (2020)

Someone: «I ate your [cupcake].»

Me: «You’re the design.»

Thing: *looks like a lion with a [wig] playing the [oboe]:

Me: «That’s the design.» ❋ Uht, Rude (2021)

I am [wearing] a designer [hand bag]. It looks so [expensive]. ❋ GalleriaofArtCOM (2014)

I want [the wash] [rags] [designative]! ❋ Maddie3299 (2011)

Humans speak through languages and things speak through design. It seems today that nobody claims to speak a foreign language they haven’t studied but everybody thinks they know design.

Let’s dive deep into the world of design and try to understand why it is so important and what purposes it serves.

- The many-sided nature of design

- THE PURPOSE OF DESIGN

- Your design doesn’t have to be original

- Designers are not like their users

- UX design is more than just usability

- Design is not a stage of the project

- Eye candy design works

- Simple doesn’t mean minimal in design

- USER INTERFACE DESIGN

- Color in design

- Typography in design

- Icons in design

- Animation in design

- For attention

- For feedback

- For progress

- For attention

- Color in design

- UX WRITING

The many-sided nature of design

In simple and brief words, a design is a plan to make something.

“Design is a plan for arranging elements in such a way as best to accomplish a particular purpose.”

― Charles Eames, American designer, architect, and filmmaker

Meanwhile, the meaning of design depends on the context and can also mean a variety of other things. Design is the creation of an experience. It’s also the process of the said creation and how well it’s organized. On top of that, design is the result, i.e. the things we see, hear, and feel.

The meaning of design is so multifaceted, to the point that you can no longer say if a universal definition is at all possible. You can, however, try to look at the sum of the parts to come up with a more realistic picture. So, Charles Eames said that design is all about purpose. Let’s dive deeper into this idea.

fantasizing… by SAM JI

The purpose of design

Every type of design exists to solve problems. To see the problem and find a solution, designers rely on data. So the toolset of the designer is based on research, not prettification.

Your design doesn’t have to be original

It’s a common misconception that novelties and hype in design will sell a product. The only reason conventional and textbook design patterns exist is because they are tested, proven, and they work. According to Jakob’s Law of Internet User Experience, users spend most of their time on other sites, so it makes perfect sense to design for patterns for which users are accustomed.

We only implement new approaches if we are 100% positive they are better than the existing ones. This alone comes from a great deal of research.

The great design solution you are looking for is out there.

The real challenge is to find it.

Every time you make a user think through an ‘innovative’ navigation pattern or an unorthodox menu placement, it’s a chance to lose them. Not because they are dumb but because we gravitate to familiar things more than we do to the unknown. If we do go for it though, we make sure everything about the new design is bulletproof.

Attitude by SAM JI

Designers are not like their users

Everybody has biases and it’s okay. Cognitive biases reduce the load and help us stay sane. That being said, it’s important to know whether your bias is damaging your design work.

Designers and owners know their product inside out. Their bias is called the Curse of Knowledge. It’s when you find it extremely difficult to think about problems from the perspective of lesser-informed people. On top of that, your goals are entirely different from those of the people you are building for.

People want to get things done, not listen about how cool you are.

What makes us different? If you are reading this, you are top of the food chain when it comes to computers. Most people are not and they don’t care. They don’t know what it takes to build a digital product just like we don’t know what it takes for our computers to work off the power line. Everybody knows something no one else does.

Oddly enough, the more employees a design company has, the stronger their detachment from real users. No matter how good they think they are. Ask Google about Buzz.

That is why it’s vital for design agencies to keep it humble and always research their users, study their goals and pains. The more we know about our users, the less biased we are. Eventually, people will have their own habits and biases about our product. But we have got to convert them first.

Submerged thoughts by SAM JI

UX design is more than just about usability

Usability is about making a product for people to accomplish their goals. UX design is a lot more robust than just that. It brings delight and meaning to ordinary things. Good UX design matters because it makes every step enjoyable, even the negative ones. If there is no network connection, the website should not die. If a page doesn’t exist, the 404 should not be a bummer. That’s a UX design job. It goes further beyond the familiar definition of user experience.

Why UX design is important and what makes good design:

- Good design will crack you up. User satisfaction is no longer a goal. It’s a default every design solution should be in line with. However, the fun and delight are the goals. The hard sell times are past. Modern design seduces and brings pleasure.

- Good design will eat your money and make you feel good about it. Practical value is only a part of what people are willing to pay for. Another part is happiness. If your design makes people feel good, they will forgive you for technical issues and bad updates. How to make them happy? Be genuine and honest about your work. Listen. Change.

- Good design feels like a person. For people to care, they have to empathize with something. If a product is designed in a way that favors everything, it favors nothing. You make a social impact by having a strong distinctive voice, promoting the right kind of values, and identifying with your audience. No matter what type of business you do, there has to be a human side to it.

- Good design has meaning. Meaning connects people with objects. If that connection is meaningful, it will stay for years. The design should empower people to establish the connections they need to feel free, capable, and enlighted.

cover art by SAM JI

Design is not a stage of the project

Even in deep tech circles, there is an idea that design is a time in the project when they draw sketches of the interfaces. It is not. Design starts when the owner first puts together the image of the product and ends when the project is done which is never.

The choice of a business model can’t rely on the goals of the owners. There might be a natural talent and an insane gut feeling but it would be foolish to rest on them.

Knowledge of how the product could fit into people’s lives is UX. Knowledge of how to implement it is UI.

UX does not result in UI. It penetrates production, testing, analytics, support, and updates that follow the creation of just interfaces. Those who realize that a designer is more than just a pencil, end up with a consistent and reliable product as opposed to a patchwork of narrow tasks.

A business owner shouldn’t be surprised when no other than a designer will start asking them about their business strategy. In fact, a designer will only be drawing the UIs for 12.5% of the time they’ll be involved in the project.

cover art by SAM JI

Eye candy design works

It might appear that design, especially the digital one, takes itself too seriously. Indeed, there are usability geeks who don’t believe aesthetics have any impact. They exemplify it by the unattractive likes of Reddit and Craigslist.

Design is no place for extremities. When there’s looks not backed by proper functionality, it’s empty. When it’s just handy and useful, there’s no emotion tied to it and it is also bad. To find the balance between usability and aesthetics, we need to know how attention works and what makes something perceived as beautiful.

To reach more people, your expertise has to spread thin and let emotions onboard users. The visual design drives emotion.

This is how web design works. The vibe of a website decides whether a person will stay and discover the features. Design is engineering in the sense that we know how to engineer delight. Through visual design, we bring meaning to ordinary things and help people find value.

An illustration is a shell for something that it represents on a deeper level. When we designed a professional platform for architects, we created an animation of elements that mimics the behavior of a construction site.

It might look subtle and may not seem worth the struggle at the early stages of design like wireframing and prototyping. But it’s important for a designer to keep in mind the image of the finished product. More so, the way you visually present your digital product says a lot about the brand in general.

No matter how good the service, if it doesn’t care for itself, neither will the people.

For skeptics, no attractive things don’t work better but they are always worth a try. Beautifully designed products get half of their credibility because of the visual appeal. It’s the developer’s job to pull the rest of the features to that level. Most people think if it looks good, it has to work well as well.

“Usability is not everything. If usability engineers designed a nightclub, it would be clean, quiet, brightly lit, with lots of places to sit down, plenty of bartenders, menus written in 18-point sans-serif, and easy-to-find bathrooms. But nobody would be there. They would all be down the street at Coyote Ugly pouring beer on each other.”

– Joel Spolsky

The point is, how the product works is important but how it looks while doing that is a game-changer.

closer view by SAM JI

Simple vs minimal in design

If you make a rating of comments on Dribbble, the ones that feature the words ‘clean’ and ‘simple’ will be well ahead of the rest. Simplicity has long become one of the staples in design. Because of that, there appeared a bunch of false beliefs that use the term ‘simplicity’ with regard to things that end up being far from simple. So what design is simple and what is minimal?

It’s important to know the distinction between the two main concepts of design optimization:

-

Simplicity is a reduced complexity

-

Minimalism is a reduced quantity

The practice of reducing and decluttering is a discipline of its own. To know what to reduce means to have confidence there will be no tension put on a user as the result of our design experiments. It’s called friction. Every design decision we make has to reduce friction. Sometimes it coerces designers into minimalism, hence the thriving trend for minimalism in web and app design. But it’s important to know where to stop.

Reducing the volume of text on buttons means substituting it with icons. But how universal are the icons? Are you 100% confident your mute icon is unambiguous and won’t mean radar to some? The Floppy Disk “Save” Icon is starting to lose a whole generation of people who have never seen one in real life.

Minimal interface design is not purpose-driven. It’s a style. Simplicity comes from our understanding of the experience no matter how multi-elemental the UI is.

The design has to be visible first so that it won’t do harm. The notorious hamburger menu has taken a beating but made its way into the designers’ minds and earned respect. What this shows is you can’t force minimalism and count on simplicity.

All Adobe products are insanely non-minimalistic. At the same time, they are perfectly clear in terms of performance and functionality. You can research the interface and make it simple, yours. But you can’t make yours something that’s not there.

To demonstrate the magnitude of the issue with simplicity and minimalism, let us bring Nielsen Norman Group’s UX case study of Tesla Model S’ 17-inch screen car interface. The main idea is that by mounting this tablet-like device on the dashboard, Tesla tapped into a realm of drivelessness and made the experience way more simple. They minimized the driver’s input but created a new pattern of behavior that might appear dangerous.

Take lane assistance. It minimizes the driver’s efforts to change lanes on one hand and dissolves their attention on the other. An engineer’s urge to minimize the pattern might cost someone their life.

Designers have to step in and take responsibility for the mental state we put people in with our products.

If it’s driving, we can’t simplify it and give people a full sense of security because. We can’t know all the possible outcomes of all the possible scenarios. Let people stay in charge, but make the experience clear and enjoyable.

Vintage wheels by SAM JI

User interface design

A user interface is the main touchpoint of a designed product and a user. The UI design is about providing a user with the simplest and most efficient way to interact with a product. In that sense, a designer has to be well aware of the following three concepts of user interface design:

- Condition or where the UI exists.

- Content or what the UI looks like.

- Context or who operates the UI.

Understanding each of these three gives a designer the most important tools to build a visual solution for any type of product.

To become visual, elements have to be designed. Those which are visible by nature, need design even more.

The UI (user interface) consists of several fundamental elements that all have to be addressed with high-level awareness.

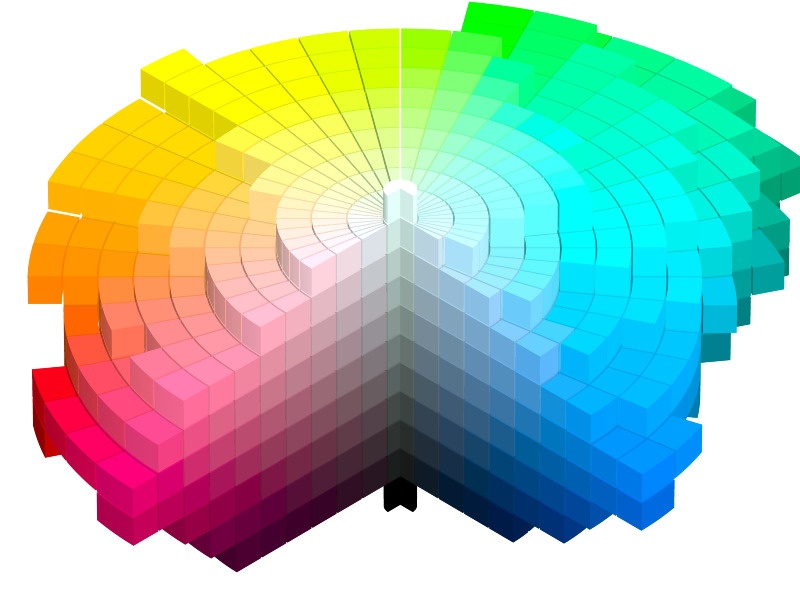

Color in design

What most people and, sadly, many designers know about color does not do it enough justice. Color is the first thing we’d notice but the last we’d understand. Colors can’t be explained and described unless seen. They can’t be changed but can be learned and used. This is how nature communicates with you, and that is why color is so important in design. Ben Hersh wrote a great guide to color in design, you might want to check it out to better understand the question.

“Colors are powerful symbols by which you live or die; they’re worth paying attention to.”

– Ben Hersh

Psychology separates color studies into a standalone discipline. Marketers know the basics of color theory in design and use it to stimulate people’s sense of security, alert, and so on. Designers use color to speak instead of words. Yet, colors don’t exist outside our consciousness.

Before the age of digital screens, people used colors as attributes of physical objects. That’s why there are so many color names attached to the toponyms (names of places). Like umber named after the soil in the Italian region of Umbria and turquoise from the French for “Turkish”. To become a recognized color, it had to exist in the real world.

As our understanding of color grew stronger, color theories began to pop out attempting to define, systemize, and classify colors.

From the Middle Ages to the 1970s’ advent of HSL and HSV color models, all the exploration and discovery lead us to the three colors: red, green, and blue.

Out of the combinations of these three, you can get virtually any color. However, this is the set we decide to stick to today. It has been different before and it might change in the future. There is no such thing as primary colors apart from those we decide to consider as such.

Prism by Jack Sabbath

We differentiate the current color models depending on the media they will be displayed on and the purpose of the visual presentation. We might leave out some colors which are not visible on the screens or include those which are not visible by the eye. Modern color technology is controlled by mathematics. But the problem is the variability of conditions under which we see these colors.

A modern color theory puts our brain in charge of our color perception depending on the context and looks to find the schemes and methods of producing colors accordingly.

“The color spaces we can see look more like psychedelic pinecones.”

– Ben Hersh

For a designer, to know color means to be able to mathematically select the colors and have the choice backed up by data. At the same time, we as designers have to be keenly aware of how colors are perceived in different cultures and how that perception changes over time.

Colors are the products of physics and mathematics but also intuitive and elusive enough to never let us rest.

Typography in design

Another thing that pops up every time there’s a talk about digital product content is typography. Technically, being just a shell for the meaning, it sometimes can be as significant as the meaning itself. Because if it doesn’t represent that meaning in good fashion, it will go unnoticed.

Text is the strongest medium of information. It might not be so much in terms of emotive response but definitely is in terms of being informative. Text is delivered by means of fonts, or typefaces, in general – typography.

Certain things only exist in one representation – text.

Typography is a design patrimony. Like any other design-specific method, typography is purpose-driven but also aesthetic. As a functional element, typography in the UI is used to guide people, invoke an action, and help them through the entire experience. That’s about the headings, titles, text in menus, buttons, CTAs, and so on.

When it comes to typography as an aesthetic element in web design, we implacably steer towards branding. Words express individuality which is the core of identity. Designers can boost that individuality through the usage of typefaces to reflect the unique character of a brand.

Typography as part of branding helps the product stand out.

Scroll by Yoga Perdana

Icons in design

Because nobody has time. We have lists everywhere. Lists are how we make sense of the abundance around us. We list foods, apps, TV channels, even friends of Facebook. This helps us structure the information and memorize it better. No wonder lists have made their way into web design where everything can be categorized. That’s how features, services, advantages, and payment plans started being aligned in lists.

Turned out, lists are good for structuring but do no good in the visual aspect.

For a list to become an attention anchor, it has to have a visual element to it. Compare the classic heading-text combo and an icon-heading-text combo:

Designers give icons a chance to give a quick snapshot of what the point is about. In this case, icons are Metaphoric Substances. This is the least icons can do. In fact, you can encode a lot of information in them in the context where the estate is a factor.

MaRc – Diner List Component by Paarth Desai

Game designers took it even further and created systems of logically-connected icons representing different in-game assets. This is called Visual Synonymity.

Rank System by 60.o

There is a fine line between icons that convey a metaphor allowing designers to cover all bases in case the textual meaning is missed and pure decorative-functioning icons. We make sure icons work in the first place, which means they motivate a user to do what we expect from them.

Ideally, icons should work the way emojis do – as a universal language flexible enough to deliver any message cross-culturally and obvious enough to leave no second guesses 💡

Animation in design

Every physical object moves. They might be still technically, but in relation to the environment, they all move. As the Sun goes over a stone in the woods, the game of light and shadows enlivens the dead stone.

Our eyes and brain are designed to capture movement because it bears a lot of information. It’d be a shame to leave it unaccounted for.

Motion is the first thing we see in the product along with color, images, and typography. These four are the main contributors to the brand’s/product’s personality. It’s important for a product to have a stance on how it’s elements move and what stands behind that movement. But first, why animation is important in UX design:

- Illustrative. It can demonstrate the functionality or help understand it better.

- Amusing. Value can be expressed in many ways. Positivity is one of them.

- Familiar. We expect certain reactions from certain actions. Animation familiarizes.

- Engaging. We tend to follow patterns and animation is a great source of those.

Triumph Motorcycle Shop Animation by Shakuro

The reason to animate the interface depends on the goal of that specific interaction. Let’s take engaging a user and directing their attention. Since movement is something we instantly see, it makes sense to use animation for things like banner ads and spams. Ads aren’t expected to sell the product, as much as they hunt for views. A view is a sell and they will get it from you by using cheap tricks. Banner ads animation is definitely a cheap trick that works.

How and when to use animation:

- For attention

The principle itself is innocent though. More so, if we use animation to direct users in a way that helps them, the same banner ad principles might contribute to a good UX. For example, a file sending gone wrong does not have to be a pop-up with an error code or a “whoops” type message. We can attract attention to this by using a meaningful motion graphic.

Mail Warning Icon Animation by Ömer Korkmaz

This animation won’t get you confused about the success of your sending and will make sure you address the issue whatever that is. At the same time, it won’t be too intimidating because the animation is done in a friendly way.

- For feedback

Animation magnifies the satisfaction you get from successfully performing a task. The more complex the task, the more rewarding it should be. Motion is how we convey the mood and the attitude of a product to the user’s actions.

Submit Button by Claudio Scotto

Such animation can cover up the time needed to complete the technical request or form submission. The spinning bubble ensures there is work going on and appeals to our natural feeling of completion.

- For progress

Most web processes have designated patterns that people recognize and expect. At the same time, with a variety of devices and screen media, it’s extremely challenging to maintain the same behavior with a lesser estate. This means we have to divide certain processes into comprehensible bits while mapping the entire progress.

This is how Google addresses a rather complicated and long process of copying information to Pixel phones.

Since this is a phone, you won’t be able to just switch to a different tab and keep yourself busy with something else. Still, you have to know what exactly is happening and why it is important.

The animation is a huge part of modern UI/UX design and we are just getting started with it. It’s a natural process of evolution that will ultimately make all animation meaningful and purposeful, forever cutting the ties to decoration. Added complexity will be replaced with modalities and subtle messages a well-thought-out animation certainly brings.

UX writing

UX writing is a process of creating copy for user interfaces. Some of you might be surprised to see writing listed among the fundamental aspects of interface design. However, writing is the most important accomplishment in human history. We are surrounded by products that are just the recreation of someone’s ideas. Sometimes those ideas are centuries old. Ideas travel by words.

The reason why animal life is finite is the inability to pass the experience of one animal to another after it. As humans, we can do this.

We pass knowledge and multiply it. This is called collective thinking and it has writing in its core.

Words are how we think and define the world around us. Words are human experience coded in something massive and yet extremely fluid – the language. The design relies on such elements and shares a long and dramatic history with writing.

Just like designers build a collection of methods, principles, and tools, they tend to do the same with a vocabulary used in interfaces. Indeed, some companies have style guides. Then there are acknowledged guides like the Chicago Manual of Style, Microsoft Manual of Style, and Associated Press Manual. They contain general recommendations for writers and designers working on specific things – documents, guides, and other user-facing assets. They teach how to avoid confusion and ambiguity but while doing that, they put a lid on the actual voice of the product.

Copywriting Keynote by Larissa Herbst

Design values individuality equally to usefulness. Tech culture took away individuality in writing only leaving it to the creative sphere. However, if the design speaks to the emotive perception, writing has to follow.

This is how UX writing was born. At some point, designers started using a specific vernacular to name the UI elements. Good or bad, they were authentic bits of text, specific for the product. We call it microcopy and it works like a regular copy with a tweak. The tweak is that even though the text is clear and simple, you can’t reuse it for another product. It won’t feel right, like something is missing. That something is context. Microcopy says things differently and exudes topicality.

Password Input + Microcopy by Mauricio Bucardo

All of a sudden the unification everybody was going for gave way to individuality through one of the best ways to pass information – words. Because words matter.

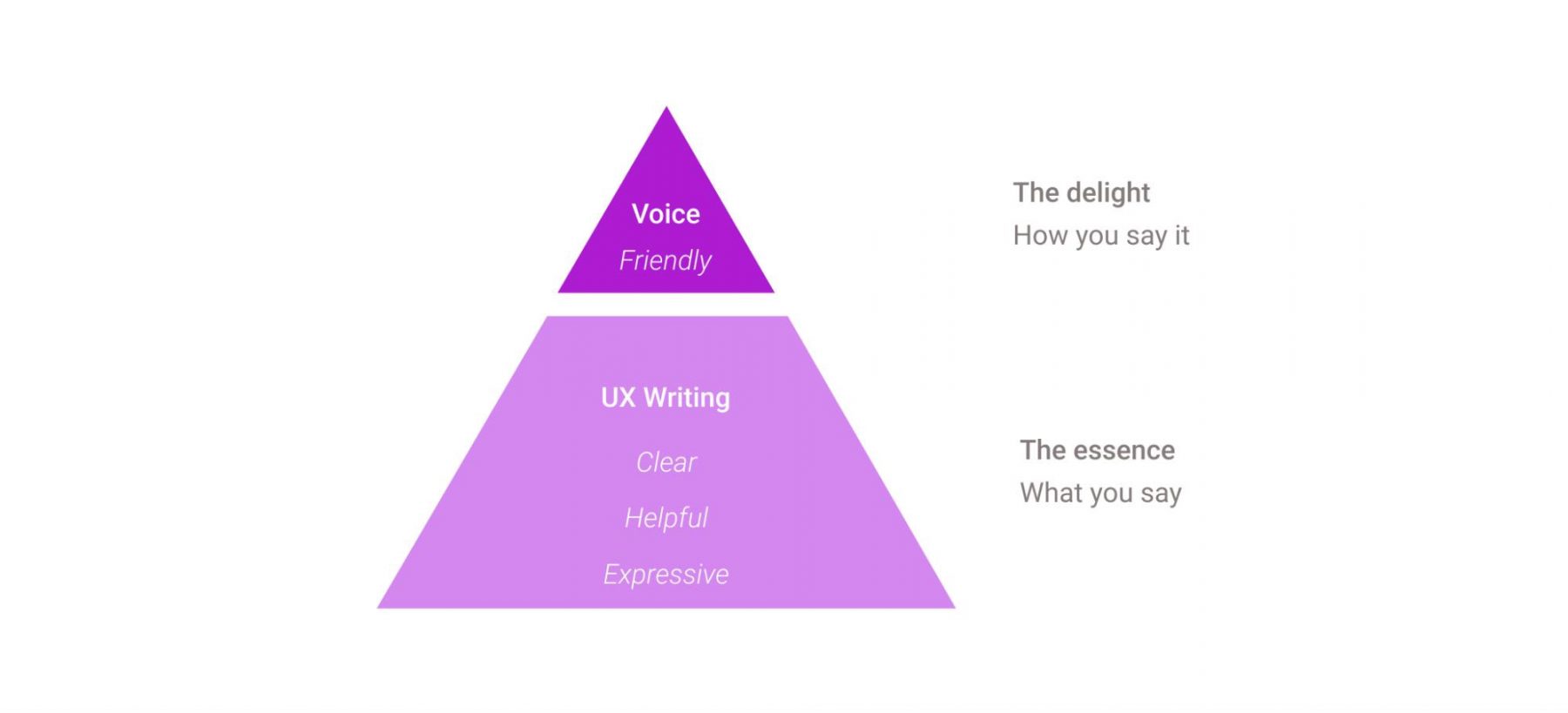

Some designers went astray and became… UX writers. And they started approaching writing with all their knowledge and skills of visual influence. The UX writing principles quickly found their form in a pyramid.

There are two layers. UX writing does not have to be personal. The essence of the product can be fulfilled by the UX writing principles alone. If it is clear, it’s helpful and if it helps, it becomes significant. The top layer is what UX writing is amplified by – the socially pleasing brand voice.

On paper, it’s quite simple but how do you put it to practice with real words and real problems?

Why we need design

Why do we use design in our everyday lives? As has been said at the beginning of this article, the meaning of design is basically about planning the most optimal way to reach a certain goal. From this perspective, everything that surrounds us is the result of design, and we design one thing or another every day, be it your breakfast or a complex report needed for your job. It’s something that is always around us holding everything together. Design is important in life because it’s an incredibly powerful force, forever changing and being changed.

Web and app design is about business goals at its heart. The value of good design is the heightened chances of success. It matters because, without an adequate design survey, every business venture is a shot in the dark. Maybe you get lucky, maybe you don’t. Professional web and app design give a company’s customers a better experience, and that’s what matters. Entrepreneurs are proud of their businesses, so why not make them perform even better, reflecting the companies’ personalities?

A good design can make people trust you more, alter customer perception, make you memorable, get your message across, make your product work to the fullest, and shine. A great one can do even more.

* * *

What is design? Every professional and author, every team, and every company has its own definition of design and understanding of what it does and what it’s all about. Each of them addresses the question of the meaning of design very differently.

But it seems that it all comes down to the simple fact that the meaning of design however it may vary depending on different projects, fields, and theories is not about beautification as such, but more of solving the specific tasks and making the lives of users better, clearer, more enjoyable.

The article was originally published in January 2020 and was updated in November 2020 to make it more relevant and comprehensive.

Table of Contents

- What is a sentence for the word design?

- In which sentence the word design is used as a verb?

- What is design simple words?

- What is another name for design?

- What are the three things a logo should be?

- What is a typographical logo?

- What typography means?

- What is typography example?

- Why is typography so important?

- What is another word for typography?

- What does typeface mean in Word?

- What is the opposite of typography?

- What is typography used for?

- Why do we use different fonts?

- What are the types of fonts?

- Which fonts do designers use?

transitive verb. 1 : to create, fashion, execute, or construct according to plan : devise, contrive design a system for tracking inventory. 2a : to conceive and plan out in the mind he designed the perfect crime.

What is a sentence for the word design?

1) The design certainly looks good on paper. 2) They wanted to design a machine that was both attractive and practical. 3) The new plane is in its final design stage. 4) The compact design of the machine allows it to be stored easily.

In which sentence the word design is used as a verb?

Used with verbs: “She created a cool design.” “He needs to improve the design.”

What is design simple words?

Design is a visual look or a shape given to a certain object, in order to make it more attractive, make it more comfortable or to improve another characteristic. Designers use tools from geometry and art. Design is also a concept used to create an object (virtual or not).

What is another name for design?

What is another word for design?

| plan | blueprint |

|---|---|

| drawing | scale drawing |

| sketch | outline |

| map | plot |

| diagram | delineation |

What are the three things a logo should be?

An effective logo should have a design that conveys your brand personality, a style choice consistent with your identity, your business name, and a relevant color choice.

What is a typographical logo?

A typographic logo is a logo that is text-based, though it might incorporate symbols or imagery. If you’re not a designer yourself, it’s the simplest type of logo to create (though truly great typographic logos will have design expertise behind them).

What typography means?

Typography, the design, or selection, of letter forms to be organized into words and sentences to be disposed in blocks of type as printing upon a page.

What is typography example?

Typeface refers to a group of characters, letters and numbers that share the same design. For example Garamond, Times, and Arial are typefaces. For example, Arial is a typeface; 16pt Arial Bold is a font.

Why is typography so important?

Typography is all about adjusting the text within the design while creating powerful content. It provides attractive appearance and preserves the aesthetic value of your content. It plays a vital role in setting the overall tone of your website, and ensures a great user experience.

What is another word for typography?

What is another word for typography?

| lettering | font |

|---|---|

| print style | |

| typeface | face |

| case | glyph |

| fount | printing |

What does typeface mean in Word?

A typeface is a set of characters of the same design. These characters include letters, numbers, punctuation marks, and symbols. The term “typeface” is often confused with “font,” which is a specific size and style of a typeface. …

What is the opposite of typography?

There are no categorical antonyms for typography. The noun typography is defined as: The art or practice of setting and arranging type; typesetting.

What is typography used for?

Typography utilized to characterize text: Typography is intended to reveal the character of the text. Through the use of typography, a body of text can instantaneously reveal the mood the author intends to convey to its readers.

Why do we use different fonts?

Every font has a unique personality and purpose. While working on a project, it’s imperative to know which font matches the intended tone of communication. Serif fonts portray tradition, sophistication and a formal tone. Sans serif fonts are modern, humanist and neutral.

What are the types of fonts?

Typography Basics There are five basic classifications of typefaces: serif, sans serif, script, monospaced, and display. As a general rule, serif and sans serif typefaces are used for either body copy or headlines (including titles, logos, etc.), while script and display typefaces are only used for headlines.

Which fonts do designers use?

Following are the top fonts professional use, and you can use too for excelling in the career of graphic design.

- Helvetica. Helvetica is among the widely used fonts by graphic designers, either professionals or working as a mid-to-senior resource.

- Garamond.

- Trajan.

- Futura.

- Bickham Script Pro.

- Bodoni.

- Frutiger.

- Gotham.

Verb

A team of engineers designed the new engine.

Who designed the book’s cover?

He designed the chair to adjust automatically.

They thought they could design the perfect crime.

design a strategy for battle

Noun

There are problems with the design of the airplane’s landing gear.

I like the design of the textbook.

I love the sculpture’s design.

The machine had a flawed design.

the design and development of new products

Correcting mistakes is part of the design process.

a number of design concepts

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Announced today at Canva’s Create event, most of these new features are designed to make creating content like social media graphics, presentations, and advertising materials more accessible to those without professional design experience.

—

Infected in the initial stages of transformation after being bit were the most difficult to design.

—

Designed by Jean-Marc Houmard and Yvan Cussigh, owners of the nearby boutique design hotel, Tribal Hotel, Casa Violeta takes inspiration from traditional Moroccan riads, an architectural style that is famous for serene courtyards.

—

And a lot of the gadgets that human beings design, that are often optimized in one way or another, are very brittle, right?

—

Changes in the genetic makeup of the virus can render older shots useless, and its rapid alterations have outpaced drugmakers’ ability to design effective new shots.

—

The popular patio style is a nice contrast against the black-and-white island in this outdoor kitchen designed by Studio Lifestyle. 8 Play With Textures For a smooth and textured design, employ pavers and pebbles set in concrete.

—

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide with exercises from experts to find your spark, design your future, and set a unique and fulfilling vision in motion.

—

Lockheed Martin said the light fixtures were designed by its engineers through a special design contest hosted during last year’s Engineers Week and were brought to life for this year’s celebration.

—

Greenworks electric chainsaws have also received praise from our editors for their smart, easy-to-use designs.

—

If the Tundra’s new design is any indication, its little brother will have a similarly familiar grille, lighting elements, and distinctive fender bulges.

—

Kwong dug into her ancestry and based her design of this year’s orchid show at the New York Botanical Garden on traditional Chinese landscape painting.

—

Christopher Scott Murrillo’s multi-locale scenic design adds a lot to the realism of the production.

—

Rolex has always been a favorite brand among top athletes and artists alike, and James and Khaled both wearing this watch in quick succession may point to the watchmaker’s more outrageous designs enjoying a moment in the spotlight.

—

By 2002, the Brick’s bulky design had given way to slim phones like the T-Mobile Sidekick, which featured a full QWERTY keyboard, for instance.

—

Moxy’s design flourishes such as the motorcycle in the lobby and the Houstons’ sky-high adult playground should tee up tempting backgrounds for people to tout their visits on social media, Wise said.

—

This past week, the watch world flocked to Geneva for Watches and Wonders, the industry’s largest and most closely watched fair, where nearly 50 brands and manufacturers unveiled their latest designs.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘design.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.