| Animals

Temporal range: Cryogenian – present, 665–0 Ma Pha. Proterozoic Archean Had’n |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Amorphea |

| Clade: | Obazoa |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

| (unranked): | Holozoa |

| (unranked): | Filozoa |

| Kingdom: | Animalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Phyla (in bold)[4] | |

Groups of uncertain placement

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a hollow sphere of cells, the blastula, during embryonic development. As of 2022, 2.16 million living animal species have been described—of which around 1.05 million are insects, over 36,000 are fishes, around 11,700 are reptiles, over 11,100 are birds, and 6,596 mammals—but it has been estimated there are around 7.77 million animal species in total. Animals range in length from 8.5 micrometres (0.00033 in) to 33.6 metres (110 ft). They have complex interactions with each other and their environments, forming intricate food webs. The scientific study of animals is known as zoology.

Most living animal species are in Bilateria, a clade whose members have a bilaterally symmetric body plan. The Bilateria include the protostomes, containing animals such as nematodes, arthropods, flatworms, annelids and molluscs, and the deuterostomes, containing the echinoderms and the chordates, the latter including the vertebrates. Life forms interpreted as early animals were present in the Ediacaran biota of the late Precambrian. Many modern animal phyla became clearly established in the fossil record as marine species during the Cambrian explosion, which began around 539 million years ago. 6,331 groups of genes common to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a single common ancestor that lived 650 million years ago.

Historically, Aristotle divided animals into those with blood and those without. Carl Linnaeus created the first hierarchical biological classification for animals in 1758 with his Systema Naturae, which Jean-Baptiste Lamarck expanded into 14 phyla by 1809. In 1874, Ernst Haeckel divided the animal kingdom into the multicellular Metazoa (now synonymous with Animalia) and the Protozoa, single-celled organisms no longer considered animals. In modern times, the biological classification of animals relies on advanced techniques, such as molecular phylogenetics, which are effective at demonstrating the evolutionary relationships between taxa.

Humans make use of many animal species, such as for food (including meat, milk, and eggs), for materials (such as leather and wool), as pets, and as working animals including for transport. Dogs have been used in hunting, as have birds of prey, while many terrestrial and aquatic animals were hunted for sports. Nonhuman animals have appeared in art from the earliest times and are featured in mythology and religion.

Etymology

The word «animal» comes from the Latin animalis, meaning ‘having breath’, ‘having soul’ or ‘living being’.[8] The biological definition includes all members of the kingdom Animalia.[9] In colloquial usage, the term animal is often used to refer only to nonhuman animals.[10][11][12][13] The term «metazoa» is derived from the Ancient Greek μετα (meta, meaning «later») and ζῷᾰ (zōia, plural of ζῷον zōion, meaning animal).[14][15]

Characteristics

Animals are unique in having the ball of cells of the early embryo (1) develop into a hollow ball or blastula (2).

Animals have several characteristics that set them apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and multicellular.[16][17] Unlike plants and algae, which produce their own nutrients,[18] animals are heterotrophic,[17][19] feeding on organic material and digesting it internally.[20] With very few exceptions, animals respire aerobically.[a][22] All animals are motile[23] (able to spontaneously move their bodies) during at least part of their life cycle, but some animals, such as sponges, corals, mussels, and barnacles, later become sessile. The blastula is a stage in embryonic development that is unique to animals, allowing cells to be differentiated into specialised tissues and organs.[24]

Structure

All animals are composed of cells, surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins.[25] During development, the animal extracellular matrix forms a relatively flexible framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganised, making the formation of complex structures possible. This may be calcified, forming structures such as shells, bones, and spicules.[26] In contrast, the cells of other multicellular organisms (primarily algae, plants, and fungi) are held in place by cell walls, and so develop by progressive growth.[27] Animal cells uniquely possess the cell junctions called tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.[28]

With few exceptions—in particular, the sponges and placozoans—animal bodies are differentiated into tissues.[29] These include muscles, which enable locomotion, and nerve tissues, which transmit signals and coordinate the body. Typically, there is also an internal digestive chamber with either one opening (in Ctenophora, Cnidaria, and flatworms) or two openings (in most bilaterians).[30]

Reproduction and development

Nearly all animals make use of some form of sexual reproduction.[31] They produce haploid gametes by meiosis; the smaller, motile gametes are spermatozoa and the larger, non-motile gametes are ova.[32] These fuse to form zygotes,[33] which develop via mitosis into a hollow sphere, called a blastula. In sponges, blastula larvae swim to a new location, attach to the seabed, and develop into a new sponge.[34] In most other groups, the blastula undergoes more complicated rearrangement.[35] It first invaginates to form a gastrula with a digestive chamber and two separate germ layers, an external ectoderm and an internal endoderm.[36] In most cases, a third germ layer, the mesoderm, also develops between them.[37] These germ layers then differentiate to form tissues and organs.[38]

Repeated instances of mating with a close relative during sexual reproduction generally leads to inbreeding depression within a population due to the increased prevalence of harmful recessive traits.[39][40] Animals have evolved numerous mechanisms for avoiding close inbreeding.[41]

Some animals are capable of asexual reproduction, which often results in a genetic clone of the parent. This may take place through fragmentation; budding, such as in Hydra and other cnidarians; or parthenogenesis, where fertile eggs are produced without mating, such as in aphids.[42][43]

Ecology

Animals are categorised into ecological groups depending on how they obtain or consume organic material, including carnivores, herbivores, omnivores, detritivores,[44] and parasites.[45] Interactions between animals form complex food webs. In carnivorous or omnivorous species, predation is a consumer–resource interaction where a predator feeds on another organism (called its prey).[46] Selective pressures imposed on one another lead to an evolutionary arms race between predator and prey, resulting in various anti-predator adaptations.[47][48] Almost all multicellular predators are animals.[49] Some consumers use multiple methods; for example, in parasitoid wasps, the larvae feed on the hosts’ living tissues, killing them in the process,[50] but the adults primarily consume nectar from flowers.[51] Other animals may have very specific feeding behaviours, such as hawksbill sea turtles primarily eating sponges.[52]

Most animals rely on the biomass and energy produced by plants through photosynthesis. Herbivores eat plant material directly, while carnivores, and other animals on higher trophic levels typically acquire it indirectly by eating other animals. Animals oxidize carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and other biomolecules, which allows the animal to grow and to sustain biological processes such as locomotion.[53][54][55] Animals living close to hydrothermal vents and cold seeps on the dark sea floor consume organic matter of archaea and bacteria produced in these locations through chemosynthesis (by oxidizing inorganic compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide).[56]

Animals originally evolved in the sea. Lineages of arthropods colonised land around the same time as land plants, probably between 510 and 471 million years ago during the Late Cambrian or Early Ordovician.[57] Vertebrates such as the lobe-finned fish Tiktaalik started to move on to land in the late Devonian, about 375 million years ago.[58][59] Animals occupy virtually all of earth’s habitats and microhabitats, including salt water, hydrothermal vents, fresh water, hot springs, swamps, forests, pastures, deserts, air, and the interiors of animals, plants, fungi and rocks.[60] Animals are however not particularly heat tolerant; very few of them can survive at constant temperatures above 50 °C (122 °F).[61] Only very few species of animals (mostly nematodes) inhabit the most extreme cold deserts of continental Antarctica.[62]

Diversity

Size

The blue whale is the largest animal that has ever lived.

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal that has ever lived, weighing up to 190 tonnes and measuring up to 33.6 metres (110 ft) long.[63][64][65] The largest extant terrestrial animal is the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), weighing up to 12.25 tonnes[63] and measuring up to 10.67 metres (35.0 ft) long.[63] The largest terrestrial animals that ever lived were titanosaur sauropod dinosaurs such as Argentinosaurus, which may have weighed as much as 73 tonnes, and Supersaurus which may have reached 39 meters.[66][67] Several animals are microscopic; some Myxozoa (obligate parasites within the Cnidaria) never grow larger than 20 µm,[68] and one of the smallest species (Myxobolus shekel) is no more than 8.5 µm when fully grown.[69]

Numbers and habitats

The following table lists estimated numbers of described extant species for all the animal groups,[70] along with their principal habitats (terrestrial, fresh water,[71] and marine),[72] and free-living or parasitic ways of life.[73] Species estimates shown here are based on numbers described scientifically; much larger estimates have been calculated based on various means of prediction, and these can vary wildly. For instance, around 25,000–27,000 species of nematodes have been described, while published estimates of the total number of nematode species include 10,000–20,000; 500,000; 10 million; and 100 million.[74] Using patterns within the taxonomic hierarchy, the total number of animal species—including those not yet described—was calculated to be about 7.77 million in 2011.[75][76][b]

| Phylum | Example | Described species | Land | Sea | Freshwater | Free-living | Parasitic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthropoda |

|

1,257,000[70] | 1,000,000 (insects)[78] |

>40,000 (Malac- ostraca)[79] |

94,000[71] | Yes[72] | >45,000[c][73] |

| Mollusca |

|

85,000[70] 107,000[80] |

35,000[80] | 60,000[80] | 5,000[71] 12,000[80] |

Yes[72] | >5,600[73] |

| Chordata |

|

>70,000[70][81] | 23,000[82] | 13,000[82] | 18,000[71] 9,000[82] |

Yes | 40 (catfish)[83][73] |

| Platyhelminthes |

|

29,500[70] | Yes[84] | Yes[72] | 1,300[71] | Yes[72]

3,000–6,500[85] |

>40,000[73]

4,000–25,000[85] |

| Nematoda |

|

25,000[70] | Yes (soil)[72] | 4,000[74] | 2,000[71] | 11,000[74] | 14,000[74] |

| Annelida |

|

17,000[70] | Yes (soil)[72] | Yes[72] | 1,750[71] | Yes | 400[73] |

| Cnidaria |

|

16,000[70] | Yes[72] | Yes (few)[72] | Yes[72] | >1,350 (Myxozoa)[73] |

|

| Porifera |

|

10,800[70] | Yes[72] | 200–300[71] | Yes | Yes[86] | |

| Echinodermata |

|

7,500[70] | 7,500[70] | Yes[72] | |||

| Bryozoa |

|

6,000[70] | Yes[72] | 60–80[71] | Yes | ||

| Rotifera |

|

2,000[70] | >400[87] | 2,000[71] | Yes | ||

| Nemertea |

|

1,350[88][89] | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Tardigrada |

|

1,335[70] | Yes[90] (moist plants) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gastrotricha |

|

794[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | Yes | ||

| Xenacoelomorpha |

|

430[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Nematomorpha |

|

354[70] | Yes (moist places)[90] |

Yes (one genus)[91] |

Yes | Yes (as adults)[90] |

Yes (as juveniles)[90] |

| Brachiopoda |

|

396[70] (30,000 extinct)[90] |

Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Kinorhyncha | 196[70] | Yes (mud)[90] | Yes | ||||

| Ctenophora |

|

187[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Onychophora |

|

187[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Chaetognatha | 186[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | ||||

| Entoprocta | 172[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | Yes | |||

| Hemichordata |

|

126[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Rhombozoa |

|

107[70] | Yes | ||||

| Gnathostomulida | 97[70] | Yes (sand)[90] | Yes | ||||

| Loricifera |

|

30[70] | Yes (sand)[90] | Yes | |||

| Orthonectida |

|

29[70] | Yes | ||||

| Priapulida |

|

20[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Phoronida |

|

16[70] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Placozoa |

|

4[92] | Yes[90] | Yes | |||

| Cycliophora |

|

2[93] | Yes[93] | Yes[94][93] | |||

| Micrognathozoa | One[90] | Yes (sand)[90] | Yes | ||||

|

Total number of described extant species as of 2013: 1,525,728[70] |

Evolutionary origin

Animals are found as long ago as the Ediacaran biota, towards the end of the Precambrian, and possibly somewhat earlier. It had long been doubted whether these life-forms included animals,[95][96][97] but the discovery of the animal lipid cholesterol in fossils of Dickinsonia establishes their nature.[98] Animals are thought to have originated under low-oxygen conditions, suggesting that they were capable of living entirely by anaerobic respiration, but as they became specialized for aerobic metabolism they became fully dependent on oxygen in their environments.[99]

Many animal phyla first appear in the fossil record during the Cambrian explosion, starting about 539 million years ago, in beds such as the Burgess shale.[100] Extant phyla in these rocks include molluscs, brachiopods, onychophorans, tardigrades, arthropods, echinoderms and hemichordates, along with numerous now-extinct forms such as the predatory Anomalocaris. The apparent suddenness of the event may however be an artefact of the fossil record, rather than showing that all these animals appeared simultaneously.[101][102][103][104]

That view is supported by the discovery of Auroralumina attenboroughii, the earliest known Ediacaran crown-group cnidarian (557–562 mya, some 20 million years before the Cambrian explosion) from Charnwood Forest, England. It is thought to be one of the earliest predators, catching small prey with its nematocysts as modern cnidarians do.[105]

Some palaeontologists have suggested that animals appeared much earlier than the Cambrian explosion, possibly as early as 1 billion years ago.[106] Early fossils that might represent animals appear for example in the 665-million-year-old rocks of the Trezona Formation of South Australia. These fossils are interpreted as most probably being early sponges.[107]

Trace fossils such as tracks and burrows found in the Tonian period (from 1 gya) may indicate the presence of triploblastic worm-like animals, roughly as large (about 5 mm wide) and complex as earthworms.[108] However, similar tracks are produced today by the giant single-celled protist Gromia sphaerica, so the Tonian trace fossils may not indicate early animal evolution.[109][110] Around the same time, the layered mats of microorganisms called stromatolites decreased in diversity, perhaps due to grazing by newly evolved animals.[111] Objects such as sediment-filled tubes that resemble trace fossils of the burrows of wormlike animals have been found in 1.2 gya rocks in North America, in 1.5 gya rocks in Australia and North America, and in 1.7 gya rocks in Australia. Their interpretation as having an animal origin is disputed, as they might be water-escape or other structures.[112][113]

Phylogeny

Animals are monophyletic, meaning they are derived from a common ancestor. Animals are sister to the Choanoflagellata, with which they form the Choanozoa.[116] The most basal animals, the Porifera, Ctenophora, Cnidaria, and Placozoa, have body plans that lack bilateral symmetry. Their relationships are still disputed; the sister group to all other animals could be the Porifera or the Ctenophora,[117] both of which lack hox genes, important in body plan development.[118]

These genes are found in the Placozoa[119][120] and the higher animals, the Bilateria.[121][122] 6,331 groups of genes common to all living animals have been identified; these may have arisen from a single common ancestor that lived 650 million years ago in the Precambrian. 25 of these are novel core gene groups, found only in animals; of those, 8 are for essential components of the Wnt and TGF-beta signalling pathways which may have enabled animals to become multicellular by providing a pattern for the body’s system of axes (in three dimensions), and another 7 are for transcription factors including homeodomain proteins involved in the control of development.[123][124]

The phylogenetic tree indicates approximately how many millions of years ago (mya) the lineages split.[125][126][127][128][129]

Non-bilateria

Non-bilaterians include sponges (centre) and corals (background).

Several animal phyla lack bilateral symmetry. Among these, the sponges (Porifera) probably diverged first, representing the oldest animal phylum.[130] Sponges lack the complex organization found in most other animal phyla;[131] their cells are differentiated, but in most cases not organised into distinct tissues.[132] They typically feed by drawing in water through pores.[133]

The Ctenophora (comb jellies) and Cnidaria (which includes jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals) are radially symmetric and have digestive chambers with a single opening, which serves as both mouth and anus.[134] They are sometimes placed together in the group Coelenterata because of common traits, not because of close relationships. Animals in both phyla have distinct tissues, but these are not organised into organs.[135] They are diploblastic, having only two main germ layers, ectoderm and endoderm.[136] The tiny placozoans are similar, but they do not have a permanent digestive chamber.[137][138]

Bilateria

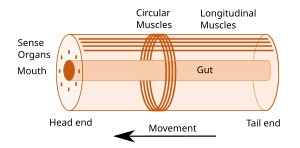

Idealised bilaterian body plan.[d] With an elongated body and a direction of movement the animal has head and tail ends. Sense organs and mouth form the basis of the head. Opposed circular and longitudinal muscles enable peristaltic motion.

The remaining animals, the great majority—comprising some 29 phyla and over a million species—form a clade, the Bilateria, which have a bilaterally symmetric body plan. The Bilateria are triploblastic, with three well-developed germ layers, and their tissues form distinct organs. The digestive chamber has two openings, a mouth and an anus, and there is an internal body cavity, a coelom or pseudocoelom. These animals have a head end (anterior) and a tail end (posterior), a back (dorsal) surface and a belly (ventral) surface, and a left and a right side.[139][140]

Having a front end means that this part of the body encounters stimuli, such as food, favouring cephalisation, the development of a head with sense organs and a mouth. Many bilaterians have a combination of circular muscles that constrict the body, making it longer, and an opposing set of longitudinal muscles, that shorten the body;[140] these enable soft-bodied animals with a hydrostatic skeleton to move by peristalsis.[141] They also have a gut that extends through the basically cylindrical body from mouth to anus. Many bilaterian phyla have primary larvae which swim with cilia and have an apical organ containing sensory cells. However, over evolutionary time, descendant spaces have evolved which have lost one or more of each of these characteristics. For example, adult echinoderms are radially symmetric (unlike their larvae), while some parasitic worms have extremely simplified body structures.[139][140]

Genetic studies have considerably changed zoologists’ understanding of the relationships within the Bilateria. Most appear to belong to two major lineages, the protostomes and the deuterostomes.[142] The basalmost bilaterians are the Xenacoelomorpha.[143][144][145]

Protostomes and deuterostomes

The bilaterian gut develops in two ways. In many protostomes, the blastopore develops into the mouth, while in deuterostomes it becomes the anus.

Protostomes and deuterostomes differ in several ways. Early in development, deuterostome embryos undergo radial cleavage during cell division, while many protostomes (the Spiralia) undergo spiral cleavage.[146]

Animals from both groups possess a complete digestive tract, but in protostomes the first opening of the embryonic gut develops into the mouth, and the anus forms secondarily. In deuterostomes, the anus forms first while the mouth develops secondarily.[147][148] Most protostomes have schizocoelous development, where cells simply fill in the interior of the gastrula to form the mesoderm. In deuterostomes, the mesoderm forms by enterocoelic pouching, through invagination of the endoderm.[149]

The main deuterostome phyla are the Echinodermata and the Chordata.[150] Echinoderms are exclusively marine and include starfish, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers.[151] The chordates are dominated by the vertebrates (animals with backbones),[152] which consist of fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.[153] The deuterostomes also include the Hemichordata (acorn worms).[154][155]

Ecdysozoa

The Ecdysozoa are protostomes, named after their shared trait of ecdysis, growth by moulting.[156] They include the largest animal phylum, the Arthropoda, which contains insects, spiders, crabs, and their kin. All of these have a body divided into repeating segments, typically with paired appendages. Two smaller phyla, the Onychophora and Tardigrada, are close relatives of the arthropods and share these traits. The ecdysozoans also include the Nematoda or roundworms, perhaps the second largest animal phylum. Roundworms are typically microscopic, and occur in nearly every environment where there is water;[157] some are important parasites.[158] Smaller phyla related to them are the Nematomorpha or horsehair worms, and the Kinorhyncha, Priapulida, and Loricifera. These groups have a reduced coelom, called a pseudocoelom.[159]

Spiralia

The Spiralia are a large group of protostomes that develop by spiral cleavage in the early embryo.[160] The Spiralia’s phylogeny has been disputed, but it contains a large clade, the superphylum Lophotrochozoa, and smaller groups of phyla such as the Rouphozoa which includes the gastrotrichs and the flatworms. All of these are grouped as the Platytrochozoa, which has a sister group, the Gnathifera, which includes the rotifers.[161][162]

The Lophotrochozoa includes the molluscs, annelids, brachiopods, nemerteans, bryozoa and entoprocts.[161][163][164] The molluscs, the second-largest animal phylum by number of described species, includes snails, clams, and squids, while the annelids are the segmented worms, such as earthworms, lugworms, and leeches. These two groups have long been considered close relatives because they share trochophore larvae.[165][166]

History of classification

Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck led the creation of a modern classification of invertebrates, breaking up Linnaeus’s «Vermes» into 9 phyla by 1809.[167]

In the classical era, Aristotle divided animals,[e] based on his own observations, into those with blood (roughly, the vertebrates) and those without. The animals were then arranged on a scale from man (with blood, 2 legs, rational soul) down through the live-bearing tetrapods (with blood, 4 legs, sensitive soul) and other groups such as crustaceans (no blood, many legs, sensitive soul) down to spontaneously generating creatures like sponges (no blood, no legs, vegetable soul). Aristotle was uncertain whether sponges were animals, which in his system ought to have sensation, appetite, and locomotion, or plants, which did not: he knew that sponges could sense touch, and would contract if about to be pulled off their rocks, but that they were rooted like plants and never moved about.[168]

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus created the first hierarchical classification in his Systema Naturae.[169] In his original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, while his Insecta (which included the crustaceans and arachnids) and Vermes have been renamed or broken up. The process was begun in 1793 by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck, who called the Vermes une espèce de chaos (a chaotic mess)[f] and split the group into three new phyla: worms, echinoderms, and polyps (which contained corals and jellyfish). By 1809, in his Philosophie Zoologique, Lamarck had created 9 phyla apart from vertebrates (where he still had 4 phyla: mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) and molluscs, namely cirripedes, annelids, crustaceans, arachnids, insects, worms, radiates, polyps, and infusorians.[167]

In his 1817 Le Règne Animal, Georges Cuvier used comparative anatomy to group the animals into four embranchements («branches» with different body plans, roughly corresponding to phyla), namely vertebrates, molluscs, articulated animals (arthropods and annelids), and zoophytes (radiata) (echinoderms, cnidaria and other forms).[171] This division into four was followed by the embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer in 1828, the zoologist Louis Agassiz in 1857, and the comparative anatomist Richard Owen in 1860.[172]

In 1874, Ernst Haeckel divided the animal kingdom into two subkingdoms: Metazoa (multicellular animals, with five phyla: coelenterates, echinoderms, articulates, molluscs, and vertebrates) and Protozoa (single-celled animals), including a sixth animal phylum, sponges.[173][172] The protozoa were later moved to the former kingdom Protista, leaving only the Metazoa as a synonym of Animalia.[174]

In human culture

Practical uses

The human population exploits a large number of other animal species for food, both of domesticated livestock species in animal husbandry and, mainly at sea, by hunting wild species.[175][176] Marine fish of many species are caught commercially for food. A smaller number of species are farmed commercially.[175][177][178] Humans and their livestock make up more than 90% of the biomass of all terrestrial vertebrates, and almost as much as all insects combined.[179]

Invertebrates including cephalopods, crustaceans, and bivalve or gastropod molluscs are hunted or farmed for food.[180] Chickens, cattle, sheep, pigs, and other animals are raised as livestock for meat across the world.[176][181][182] Animal fibres such as wool are used to make textiles, while animal sinews have been used as lashings and bindings, and leather is widely used to make shoes and other items. Animals have been hunted and farmed for their fur to make items such as coats and hats.[183] Dyestuffs including carmine (cochineal),[184][185] shellac,[186][187] and kermes[188][189] have been made from the bodies of insects. Working animals including cattle and horses have been used for work and transport from the first days of agriculture.[190]

Animals such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster serve a major role in science as experimental models.[191][192][193][194] Animals have been used to create vaccines since their discovery in the 18th century.[195] Some medicines such as the cancer drug Yondelis are based on toxins or other molecules of animal origin.[196]

A gun dog retrieving a duck during a hunt

People have used hunting dogs to help chase down and retrieve animals,[197] and birds of prey to catch birds and mammals,[198] while tethered cormorants have been used to catch fish.[199] Poison dart frogs have been used to poison the tips of blowpipe darts.[200][201]

A wide variety of animals are kept as pets, from invertebrates such as tarantulas and octopuses, insects including praying mantises,[202] reptiles such as snakes and chameleons,[203] and birds including canaries, parakeets, and parrots[204] all finding a place. However, the most kept pet species are mammals, namely dogs, cats, and rabbits.[205][206][207] There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence as individuals with rights of their own.[208]

A wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic animals are hunted for sport.[209]

Symbolic uses

Animals have been the subjects of art from the earliest times, both historical, as in Ancient Egypt, and prehistoric, as in the cave paintings at Lascaux. Major animal paintings include Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 The Rhinoceros, and George Stubbs’s c. 1762 horse portrait Whistlejacket.[210] Insects, birds and mammals play roles in literature and film,[211] such as in giant bug movies.[212][213][214]

Animals including insects[215] and mammals[216] feature in mythology and religion. In both Japan and Europe, a butterfly was seen as the personification of a person’s soul,[215][217][218] while the scarab beetle was sacred in ancient Egypt.[219] Among the mammals, cattle,[220] deer,[216] horses,[221] lions,[222] bats,[223] bears,[224] and wolves[225] are the subjects of myths and worship. The signs of the Western and Chinese zodiacs are based on animals.[226][227]

See also

- Animal attacks

- Animal coloration

- Ethology

- Fauna

- List of animal names

- Lists of organisms by population

Notes

- ^ Henneguya zschokkei does not have mitochondrial DNA or utilize aerobic respiration.[21]

- ^ The application of DNA barcoding to taxonomy further complicates this; a 2016 barcoding analysis estimated a total count of nearly 100,000 insect species for Canada alone, and extrapolated that the global insect fauna must be in excess of 10 million species, of which nearly 2 million are in a single fly family known as gall midges (Cecidomyiidae).[77]

- ^ Not including parasitoids.[73]

- ^ Compare File:Annelid redone w white background.svg for a more specific and detailed model of a particular phylum with this general body plan.

- ^ In his History of Animals and Parts of Animals.

- ^ The prefix une espèce de is pejorative.[170]

References

- ^ Zverkov, Oleg A.; Mikhailov, Kirill V.; Isaev, Sergey V.; Rusin, Leonid Y.; Popova, Olga V.; Logacheva, Maria D.; Penin, Alexey A.; Moroz, Leonid L.; Panchin, Yuri V.; Lyubetsky, Vassily A.; Aleoshin, Vladimir V. (24 May 2019). «Dicyemida and Orthonectida: Two Stories of Body Plan Simplification». Front. Genet. 10: 443. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00443. PMC 6543705. PMID 31178892.

- ^ Drábková, Marie; Kocot, Kevin M.; Halanych, Kenneth M.; Oakley, Todd H.; Moroz, Leonid L.; Cannon, Johanna T.; Kuris, Armand; Garcia-Vedrenne, Ana Elisa; Pankey, M. Sabrina; Ellis, Emily A.; Varney, Rebecca; Štefka, Jan; Zrzavý, Jan (2022). «Different phylogenomic methods support monophyly of enigmatic ‘Mesozoa’ (Dicyemida + Orthonectida, Lophotrochozoa)». Proc. R. Soc. B. 289 (1978): 20220683. doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.0683. PMC 9257288. PMID 35858055.

- ^ McClain, Craig R.; Boyer, Alison G. (2009). «Biodiversity and body size are linked across metazoans». Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1665): 2209–2215. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0245. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2677615. PMID 19324730.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2020). The Invertebrate Tree of Life. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvscxrhm. ISBN 978-0-691-17025-1. S2CID 213945949.

- ^ de Queiroz, Kevin; Cantino, Philip; Gauthier, Jacques, eds. (2020). «Metazoa E. Haeckel 1874 [J. R. Garey and K. M. Halanych], converted clade name». Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode (1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 1352. doi:10.1201/9780429446276. ISBN 9780429446276. S2CID 242704712.

- ^ Nielsen, Claus (2008). «Six major steps in animal evolution: are we derived sponge larvae?». Evolution & Development. 10 (2): 241–257. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00231.x. PMID 18315817. S2CID 8531859.

- ^ a b c Rothmaler, Werner (1951). «Die Abteilungen und Klassen der Pflanzen». Feddes Repertorium, Journal of Botanical Taxonomy and Geobotany. 54 (2–3): 256–266. doi:10.1002/fedr.19510540208.

- ^ Cresswell, Julia (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954793-7.

‘having the breath of life’, from anima ‘air, breath, life’.

- ^ «Animal». The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. 2006.

- ^ «animal». English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Boly, Melanie; Seth, Anil K.; Wilke, Melanie; Ingmundson, Paul; Baars, Bernard; Laureys, Steven; Edelman, David; Tsuchiya, Naotsugu (2013). «Consciousness in humans and non-human animals: recent advances and future directions». Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 625. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625. PMC 3814086. PMID 24198791.

- ^ «The use of non-human animals in research». Royal Society. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ «Nonhuman definition and meaning». Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ «Metazoan». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ «Metazoa». Collins. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022. and further meta- (sense 1) Archived 30 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine and -zoa Archived 30 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Avila, Vernon L. (1995). Biology: Investigating Life on Earth. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 767–. ISBN 978-0-86720-942-6.

- ^ a b «Palaeos:Metazoa». Palaeos. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Davidson, Michael W. «Animal Cell Structure». Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Bergman, Jennifer. «Heterotrophs». Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Douglas, Angela E.; Raven, John A. (January 2003). «Genomes at the interface between bacteria and organelles». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 358 (1429): 5–17. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188. PMC 1693093. PMID 12594915.

- ^ Andrew, Scottie (26 February 2020). «Scientists discovered the first animal that doesn’t need oxygen to live. It’s changing the definition of what an animal can be». CNN. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Mentel, Marek; Martin, William (2010). «Anaerobic animals from an ancient, anoxic ecological niche». BMC Biology. 8: 32. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32. PMC 2859860. PMID 20370917.

- ^ Saupe, S. G. «Concepts of Biology». Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Minkoff, Eli C. (2008). Barron’s EZ-101 Study Keys Series: Biology (2nd, revised ed.). Barron’s Educational Series. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7641-3920-8.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Sangwal, Keshra (2007). Additives and crystallization processes: from fundamentals to applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-470-06153-4.

- ^ Becker, Wayne M. (1991). The world of the cell. Benjamin/Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-0870-9.

- ^ Magloire, Kim (2004). Cracking the AP Biology Exam, 2004–2005 Edition. The Princeton Review. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-375-76393-9.

- ^ Starr, Cecie (2007). Biology: Concepts and Applications without Physiology. Cengage Learning. pp. 362, 365. ISBN 978-0-495-38150-1. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Hillmer, Gero; Lehmann, Ulrich (1983). Fossil Invertebrates. Translated by J. Lettau. CUP Archive. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-27028-1. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Knobil, Ernst (1998). Encyclopedia of reproduction, Volume 1. Academic Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-12-227020-8.

- ^ Schwartz, Jill (2010). Master the GED 2011. Peterson’s. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-7689-2885-3.

- ^ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ^ Ville, Claude Alvin; Walker, Warren Franklin; Barnes, Robert D. (1984). General zoology. Saunders College Pub. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-03-062451-3.

- ^ Hamilton, William James; Boyd, James Dixon; Mossman, Harland Winfield (1945). Human embryology: (prenatal development of form and function). Williams & Wilkins. p. 330.

- ^ Philips, Joy B. (1975). Development of vertebrate anatomy. Mosby. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-8016-3927-2.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 10. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1918. p. 281.

- ^ Romoser, William S.; Stoffolano, J. G. (1998). The science of entomology. WCB McGraw-Hill. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-697-22848-2.

- ^ Charlesworth, D.; Willis, J. H. (2009). «The genetics of inbreeding depression». Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (11): 783–796. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483. S2CID 771357.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Hopf, F. A.; Michod, R. E. (1987). The molecular basis of the evolution of sex. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 24. pp. 323–370. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 978-0-12-017624-3. PMID 3324702.

- ^ Pusey, Anne; Wolf, Marisa (1996). «Inbreeding avoidance in animals». Trends Ecol. Evol. 11 (5): 201–206. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8. PMID 21237809.

- ^ Adiyodi, K. G.; Hughes, Roger N.; Adiyodi, Rita G. (July 2002). Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Volume 11, Progress in Asexual Reproduction. Wiley. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-471-48968-9.

- ^ Schatz, Phil. «Concepts of Biology: How Animals Reproduce». OpenStax College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Marchetti, Mauro; Rivas, Victoria (2001). Geomorphology and environmental impact assessment. Taylor & Francis. p. 84. ISBN 978-90-5809-344-8.

- ^ Levy, Charles K. (1973). Elements of Biology. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-390-55627-1.

- ^ Begon, M.; Townsend, C.; Harper, J. (1996). Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities (Third ed.). Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-86542-845-4.

- ^ Allen, Larry Glen; Pondella, Daniel J.; Horn, Michael H. (2006). Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters. University of California Press. p. 428. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ^ Caro, Tim (2005). Antipredator Defenses in Birds and Mammals. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–6 and passim.

- ^ Simpson, Alastair G.B; Roger, Andrew J. (2004). «The real ‘kingdoms’ of eukaryotes». Current Biology. 14 (17): R693–696. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038. PMID 15341755. S2CID 207051421.

- ^ Stevens, Alison N. P. (2010). «Predation, Herbivory, and Parasitism». Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 36. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Jervis, M. A.; Kidd, N. A. C. (November 1986). «Host-Feeding Strategies in Hymenopteran Parasitoids». Biological Reviews. 61 (4): 395–434. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1986.tb00660.x. S2CID 84430254.

- ^ Meylan, Anne (22 January 1988). «Spongivory in Hawksbill Turtles: A Diet of Glass». Science. 239 (4838): 393–395. Bibcode:1988Sci…239..393M. doi:10.1126/science.239.4838.393. JSTOR 1700236. PMID 17836872. S2CID 22971831.

- ^ Clutterbuck, Peter (2000). Understanding Science: Upper Primary. Blake Education. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86509-170-9.

- ^ Gupta, P. K. (1900). Genetics Classical To Modern. Rastogi Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-7133-896-2.

- ^ Garrett, Reginald; Grisham, Charles M. (2010). Biochemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-495-10935-8.

- ^ Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. (2007). Marine Biology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-07-722124-9.

- ^ Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Daley, Allison C.; Pisani, Davide (2013). «Molecular Timetrees Reveal a Cambrian Colonization of Land and a New Scenario for Ecdysozoan Evolution». Current Biology. 23 (5): 392–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026. PMID 23375891.

- ^ Daeschler, Edward B.; Shubin, Neil H.; Jenkins, Farish A. Jr. (6 April 2006). «A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan». Nature. 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. PMID 16598249.

- ^ Clack, Jennifer A. (21 November 2005). «Getting a Leg Up on Land». Scientific American. 293 (6): 100–7. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f.100C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100. PMID 16323697.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Schwartz, Karlene V.; Dolan, Michael (1999). Diversity of Life: The Illustrated Guide to the Five Kingdoms. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-7637-0862-7.

- ^ Clarke, Andrew (2014). «The thermal limits to life on Earth» (PDF). International Journal of Astrobiology. 13 (2): 141–154. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..141C. doi:10.1017/S1473550413000438. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019.

- ^ «Land animals». British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Davies, Ella (20 April 2016). «The longest animal alive may be one you never thought of». BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ «Largest mammal». Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). «Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs». Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. S2CID 56028251.

- ^ Curtice, Brian (2020). «Society of Vertebrate Paleontology» (PDF). Vertpaleo.org.

- ^ Fiala, Ivan (10 July 2008). «Myxozoa». Tree of Life Web Project. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Kaur, H.; Singh, R. (2011). «Two new species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) infecting an Indian major carp and a cat fish in wetlands of Punjab, India». Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 35 (2): 169–176. doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4. PMC 3235390. PMID 23024499.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Zhang, Zhi-Qiang (30 August 2013). «Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)». Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 5. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Balian, E. V.; Lévêque, C.; Segers, H.; Martens, K. (2008). Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment. Springer. p. 628. ISBN 978-1-4020-8259-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hogenboom, Melissa. «There are only 35 kinds of animal and most are really weird». BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Poulin, Robert (2007). Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites. Princeton University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-691-12085-0.

- ^ a b c d Felder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. (2009). Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity. Texas A&M University Press. p. 1111. ISBN 978-1-60344-269-5.

- ^ «How many species on Earth? About 8.7 million, new estimate says». 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Worm, Boris (23 August 2011). Mace, Georgina M. (ed.). «How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?». PLOS Biology. 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. PMC 3160336. PMID 21886479.

- ^ Hebert, Paul D.N.; Ratnasingham, Sujeevan; Zakharov, Evgeny V.; Telfer, Angela C.; Levesque-Beaudin, Valerie; Milton, Megan A.; Pedersen, Stephanie; Jannetta, Paul; deWaard, Jeremy R. (1 August 2016). «Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1702): 20150333. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0333. PMC 4971185. PMID 27481785.

- ^ Stork, Nigel E. (January 2018). «How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth?». Annual Review of Entomology. 63 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043348. PMID 28938083. S2CID 23755007. Stork notes that 1m insects have been named, making much larger predicted estimates.

- ^ Poore, Hugh F. (2002). «Introduction». Crustacea: Malacostraca. Zoological catalogue of Australia. Vol. 19.2A. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-643-06901-5.

- ^ a b c d Nicol, David (June 1969). «The Number of Living Species of Molluscs». Systematic Zoology. 18 (2): 251–254. doi:10.2307/2412618. JSTOR 2412618.

- ^ Uetz, P. «A Quarter Century of Reptile and Amphibian Databases». Herpetological Review. 52: 246–255. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c Reaka-Kudla, Marjorie L.; Wilson, Don E.; Wilson, Edward O. (1996). Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources. Joseph Henry Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-309-52075-1.

- ^ Burton, Derek; Burton, Margaret (2017). Essential Fish Biology: Diversity, Structure and Function. Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-19-878555-2.

Trichomycteridae … includes obligate parasitic fish. Thus 17 genera from 2 subfamilies, Vandelliinae; 4 genera, 9spp. and Stegophilinae; 13 genera, 31 spp. are parasites on gills (Vandelliinae) or skin (stegophilines) of fish.

- ^ Sluys, R. (1999). «Global diversity of land planarians (Platyhelminthes, Tricladida, Terricola): a new indicator-taxon in biodiversity and conservation studies». Biodiversity and Conservation. 8 (12): 1663–1681. doi:10.1023/A:1008994925673. S2CID 38784755.

- ^ a b Pandian, T. J. (2020). Reproduction and Development in Platyhelminthes. CRC Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-000-05490-3. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. (2015). Parasite Diversity and Diversification. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-107-03765-6. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Fontaneto, Diego. «Marine Rotifers | An Unexplored World of Richness» (PDF). JMBA Global Marine Environment. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Chernyshev, A. V. (September 2021). «An updated classification of the phylum Nemertea». Invertebrate Zoology. 18 (3): 188–196. doi:10.15298/invertzool.18.3.01. S2CID 239872311. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Hookabe, Natsumi; Kajihara, Hiroshi; Chernyshev, Alexei V.; Jimi, Naoto; Hasegawa, Naohiro; Kohtsuka, Hisanori; Okanishi, Masanori; Tani, Kenichiro; Fujiwara, Yoshihiro; Tsuchida, Shinji; Ueshima, Rei (2022). «Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Nipponnemertes (Nemertea: Monostilifera: Cratenemertidae) and Descriptions of 10 New Species, With Notes on Small Body Size in a Newly Discovered Clade». Frontiers in Marine Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.906383. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Hickman, Cleveland P.; Keen, Susan L.; Larson, Allan; Eisenhour, David J. (2018). Animal Diversity (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education, New York. ISBN 978-1-260-08427-6.

- ^ Kakui K, Fukuchi J, Shimada D (2021). «First report of marine horsehair worms (Nematomorpha: Nectonema) parasitic in isopod crustaceans». Parasitol Res. 120 (7): 2357–2362. doi:10.1007/s00436-021-07213-9. hdl:2115/85646. PMID 34156539. S2CID 235596142.

- ^ Tessler, Michael; Neumann, Johannes S.; Kamm, Kai; Osigus, Hans-Jürgen; Eshel, Gil; Narechania, Apurva; Burns, John A.; DeSalle, Rob; Schierwater, Bernd (8 December 2022). «Phylogenomics and the first higher taxonomy of Placozoa, an ancient and enigmatic animal phylum». Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 10: 1016357. doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.1016357. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ a b c Obst, M; Funch, P; Mobjergkristensen, R (10 May 2006). «A new species of Cycliophora from the mouthparts of the American lobster, Homarus americanus (Nephropidae, Decapoda)». Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 6 (2): 83–97. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2005.05.001.

- ^ in some life stages attached

- ^ Shen, Bing; Dong, Lin; Xiao, Shuhai; Kowalewski, Michał (2008). «The Avalon Explosion: Evolution of Ediacara Morphospace». Science. 319 (5859): 81–84. Bibcode:2008Sci…319…81S. doi:10.1126/science.1150279. PMID 18174439. S2CID 206509488.

- ^ Chen, Zhe; Chen, Xiang; Zhou, Chuanming; Yuan, Xunlai; Xiao, Shuhai (1 June 2018). «Late Ediacaran trackways produced by bilaterian animals with paired appendages». Science Advances. 4 (6): eaao6691. Bibcode:2018SciA….4.6691C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6691. PMC 5990303. PMID 29881773.

- ^ Schopf, J. William (1999). Evolution!: facts and fallacies. Academic Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-12-628860-5.

- ^ a b Bobrovskiy, Ilya; Hope, Janet M.; Ivantsov, Andrey; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Hallmann, Christian; Brocks, Jochen J. (20 September 2018). «Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals». Science. 361 (6408): 1246–1249. Bibcode:2018Sci…361.1246B. doi:10.1126/science.aat7228. PMID 30237355.

- ^ Zimorski, Verena; Mentel, Marek; Tielens, Aloysius G. M.; Martin, William F. (2019). «Energy metabolism in anaerobic eukaryotes and Earth’s late oxygenation». Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 140: 279–294. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.030. PMC 6856725. PMID 30935869.

- ^ «Stratigraphic Chart 2022» (PDF). International Stratigraphic Commission. February 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Maloof, A. C.; Porter, S. M.; Moore, J. L.; Dudas, F. O.; Bowring, S. A.; Higgins, J. A.; Fike, D. A.; Eddy, M. P. (2010). «The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change». Geological Society of America Bulletin. 122 (11–12): 1731–1774. Bibcode:2010GSAB..122.1731M. doi:10.1130/B30346.1. S2CID 6694681.

- ^ «New Timeline for Appearances of Skeletal Animals in Fossil Record Developed by UCSB Researchers». The Regents of the University of California. 10 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Conway-Morris, Simon (2003). «The Cambrian «explosion» of metazoans and molecular biology: would Darwin be satisfied?». The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8): 505–515. PMID 14756326. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ «The Tree of Life». The Burgess Shale. Royal Ontario Museum. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ a b Dunn, F. S.; Kenchington, C. G.; Parry, L. A.; Clark, J. W.; Kendall, R. S.; Wilby, P. R. (25 July 2022). «A crown-group cnidarian from the Ediacaran of Charnwood Forest, UK». Nature Ecology & Evolution. 6 (8): 1095–1104. doi:10.1038/s41559-022-01807-x. PMC 9349040. PMID 35879540.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (7th ed.). Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. p. 526. ISBN 978-0-8053-7171-0.

- ^ Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. (17 August 2010). «Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia». Nature Geoscience. 3 (9): 653–659. Bibcode:2010NatGe…3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934.

- ^ Seilacher, Adolf; Bose, Pradip K.; Pfluger, Friedrich (2 October 1998). «Triploblastic animals more than 1 billion years ago: trace fossil evidence from india». Science. 282 (5386): 80–83. Bibcode:1998Sci…282…80S. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80. PMID 9756480.

- ^ Matz, Mikhail V.; Frank, Tamara M.; Marshall, N. Justin; Widder, Edith A.; Johnsen, Sönke (9 December 2008). «Giant Deep-Sea Protist Produces Bilaterian-like Traces». Current Biology. 18 (23): 1849–54. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.028. PMID 19026540. S2CID 8819675.

- ^ Reilly, Michael (20 November 2008). «Single-celled giant upends early evolution». NBC News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Bengtson, S. (2002). «Origins and early evolution of predation» (PDF). In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P. H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers. Vol. 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Seilacher, Adolf (2007). Trace fossil analysis. Berlin: Springer. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-3-540-47226-1. OCLC 191467085.

- ^ Breyer, J. A. (1995). «Possible new evidence for the origin of metazoans prior to 1 Ga: Sediment-filled tubes from the Mesoproterozoic Allamoore Formation, Trans-Pecos Texas». Geology. 23 (3): 269–272. Bibcode:1995Geo….23..269B. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0269:PNEFTO>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ El Albani, Abderrazak; Bengtson, Stefan; Canfield, Donald E.; Riboulleau, Armelle; Rollion Bard, Claire; Macchiarelli, Roberto; et al. (2014). «The 2.1 Ga Old Francevillian Biota: Biogenicity, Taphonomy and Biodiversity». PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e99438. Bibcode:2014PLoSO…999438E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099438. PMC 4070892. PMID 24963687.

- ^ Sebe-Pedros, A.; Roger, A. J.; Lang, F. B.; King, N.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. (2010). «Ancient origin of the integrin-mediated adhesion and signaling machinery». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (22): 10142–10147. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10710142S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002257107. PMC 2890464. PMID 20479219.

- ^ Budd, Graham E.; Jensen, Sören (2017). «The origin of the animals and a ‘Savannah’ hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution». Biological Reviews. 92 (1): 446–473. doi:10.1111/brv.12239. PMID 26588818.

- ^ Kapli, Paschalia; Telford, Maximilian J. (11 December 2020). «Topology-dependent asymmetry in systematic errors affects phylogenetic placement of Ctenophora and Xenacoelomorpha». Science Advances. 6 (10): eabc5162. Bibcode:2020SciA….6.5162K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc5162. PMC 7732190. PMID 33310849.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo (27 September 2016). «Genomics and the animal tree of life: conflicts and future prospects». Zoologica Scripta. 45: 14–21. doi:10.1111/zsc.12215.

- ^ «Evolution and Development» (PDF). Carnegie Institution for Science Department of Embryology. 1 May 2012. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Dellaporta, Stephen; Holland, Peter; Schierwater, Bernd; Jakob, Wolfgang; Sagasser, Sven; Kuhn, Kerstin (April 2004). «The Trox-2 Hox/ParaHox gene of Trichoplax (Placozoa) marks an epithelial boundary». Development Genes and Evolution. 214 (4): 170–175. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0390-8. PMID 14997392. S2CID 41288638.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Eernisse, Douglas J (2001). «Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: Inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences». Evolution and Development. 3 (3): 170–205. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.121.1228. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x. PMID 11440251. S2CID 7829548.

- ^ Kraemer-Eis, Andrea; Ferretti, Luca; Schiffer, Philipp; Heger, Peter; Wiehe, Thomas (2016). «A catalogue of Bilaterian-specific genes – their function and expression profiles in early development» (PDF). bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/041806. S2CID 89080338. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2018.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (4 May 2018). «The Very First Animal Appeared Amid an Explosion of DNA». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Paps, Jordi; Holland, Peter W. H. (30 April 2018). «Reconstruction of the ancestral metazoan genome reveals an increase in genomic novelty». Nature Communications. 9 (1730 (2018)): 1730. Bibcode:2018NatCo…9.1730P. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5. PMC 5928047. PMID 29712911.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide (27 April 2008). «The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1496): 1435–1443. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233. PMC 2614224. PMID 18192191.

- ^ Parfrey, Laura Wegener; Lahr, Daniel J. G.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Katz, Laura A. (16 August 2011). «Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (33): 13624–13629. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813624P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108. PMC 3158185. PMID 21810989.

- ^ «Raising the Standard in Fossil Calibration». Fossil Calibration Database. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Laumer, Christopher E.; Gruber-Vodicka, Harald; Hadfield, Michael G.; Pearse, Vicki B.; Riesgo, Ana; Marioni, John C.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2018). «Support for a clade of Placozoa and Cnidaria in genes with minimal compositional bias». eLife. 2018, 7: e36278. doi:10.7554/eLife.36278. PMC 6277202. PMID 30373720.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W. (2018). «Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes». Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Bhamrah, H. S.; Juneja, Kavita (2003). An Introduction to Porifera. Anmol Publications. p. 58. ISBN 978-81-261-0675-2.

- ^ Sumich, James L. (2008). Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7637-5730-4.

- ^ Jessop, Nancy Meyer (1970). Biosphere; a study of life. Prentice-Hall. p. 428.

- ^ Sharma, N. S. (2005). Continuity And Evolution Of Animals. Mittal Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-8293-018-6.

- ^ Langstroth, Lovell; Langstroth, Libby (2000). Newberry, Todd (ed.). A Living Bay: The Underwater World of Monterey Bay. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-22149-9.

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Kotpal, R.L. (2012). Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates. Rastogi Publications. p. 184. ISBN 978-81-7133-903-7.

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Holt-Saunders International. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ «Introduction to Placozoa». UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b Minelli, Alessandro (2009). Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-856620-5.

- ^ a b c Brusca, Richard C. (2016). Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha | Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation (PDF). Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates. pp. 345–372. ISBN 978-1-60535-375-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Quillin, K. J. (May 1998). «Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris». Journal of Experimental Biology. 201 (12): 1871–1883. doi:10.1242/jeb.201.12.1871. PMID 9600869. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Telford, Maximilian J. (2008). «Resolving Animal Phylogeny: A Sledgehammer for a Tough Nut?». Developmental Cell. 14 (4): 457–459. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016. PMID 18410719.

- ^ Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R.R.; Moroz, L. L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A.J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K. J.; Telford, M.J. (2011). «Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella«. Nature. 470 (7333): 255–258. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..255P. doi:10.1038/nature09676. PMC 4025995. PMID 21307940.

- ^ Perseke, M.; Hankeln, T.; Weich, B.; Fritzsch, G.; Stadler, P.F.; Israelsson, O.; Bernhard, D.; Schlegel, M. (August 2007). «The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis» (PDF). Theory Biosci. 126 (1): 35–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.177.8060. doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7. PMID 18087755. S2CID 17065867. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Cannon, Johanna T.; Vellutini, Bruno C.; Smith III, Julian.; Ronquist, Frederik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas (3 February 2016). «Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa». Nature. 530 (7588): 89–93. Bibcode:2016Natur.530…89C. doi:10.1038/nature16520. PMID 26842059. S2CID 205247296. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Valentine, James W. (July 1997). «Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life». PNAS. 94 (15): 8001–8005. Bibcode:1997PNAS…94.8001V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001. PMC 21545. PMID 9223303.

- ^ Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael (2005). The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 717. ISBN 978-0-521-83762-0.

- ^ Hejnol, A.; Martindale, M.Q. (2009). Telford, M.J.; Littlewood, D.J. (eds.). The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore – open questions about questionable openings. Animal Evolution – Genomes, Fossils, and Trees. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–40. ISBN 978-0-19-957030-0. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Hyde, Kenneth (2004). Zoology: An Inside View of Animals. Kendall Hunt. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-7575-0997-1.

- ^ Alcamo, Edward (1998). Biology Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-679-77884-4.

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2008). The First Vertebrates. Infobase Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8160-5958-4.

- ^ Rice, Stanley A. (2007). Encyclopedia of evolution. Infobase Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8160-5515-9.

- ^ Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie (2005). Asking about life. Cengage Learning. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-534-40653-0.

- ^ Simakov, Oleg; Kawashima, Takeshi; Marlétaz, Ferdinand; Jenkins, Jerry; Koyanagi, Ryo; Mitros, Therese; Hisata, Kanako; Bredeson, Jessen; Shoguchi, Eiichi (26 November 2015). «Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins». Nature. 527 (7579): 459–465. Bibcode:2015Natur.527..459S. doi:10.1038/nature16150. PMC 4729200. PMID 26580012.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2005). The Ancestor’s Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ Prewitt, Nancy L.; Underwood, Larry S.; Surver, William (2003). BioInquiry: making connections in biology. John Wiley. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-471-20228-8.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel, Paul (1998). Parasites in social insects. Princeton University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-691-05924-2.

- ^ Miller, Stephen A.; Harley, John P. (2006). Zoology. McGraw-Hill. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-07-063682-8.

- ^ Shankland, M.; Seaver, E.C. (2000). «Evolution of the bilaterian body plan: What have we learned from annelids?». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (9): 4434–4437. Bibcode:2000PNAS…97.4434S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434. JSTOR 122407. PMC 34316. PMID 10781038.

- ^ a b Struck, Torsten H.; Wey-Fabrizius, Alexandra R.; Golombek, Anja; Hering, Lars; Weigert, Anne; Bleidorn, Christoph; Klebow, Sabrina; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Hausdorf, Bernhard; Petersen, Malte; Kück, Patrick; Herlyn, Holger; Hankeln, Thomas (2014). «Platyzoan Paraphyly Based on Phylogenomic Data Supports a Noncoelomate Ancestry of Spiralia». Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (7): 1833–1849. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu143. PMID 24748651.

- ^ Fröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter (April 2017). «Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans». Nature Communications. 8 (1): 9. Bibcode:2017NatCo…8….9F. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w. PMC 5431905. PMID 28377584.

- ^ Hervé, Philippe; Lartillot, Nicolas; Brinkmann, Henner (May 2005). «Multigene Analyses of Bilaterian Animals Corroborate the Monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia». Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (5): 1246–1253. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi111. PMID 15703236.

- ^ Speer, Brian R. (2000). «Introduction to the Lophotrochozoa | Of molluscs, worms, and lophophores…» UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Giribet, G.; Distel, D.L.; Polz, M.; Sterrer, W.; Wheeler, W.C. (2000). «Triploblastic relationships with emphasis on the acoelomates and the position of Gnathostomulida, Cycliophora, Plathelminthes, and Chaetognatha: a combined approach of 18S rDNA sequences and morphology». Syst Biol. 49 (3): 539–562. doi:10.1080/10635159950127385. PMID 12116426.

- ^ Kim, Chang Bae; Moon, Seung Yeo; Gelder, Stuart R.; Kim, Won (September 1996). «Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology». Journal of Molecular Evolution. 43 (3): 207–215. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..207K. doi:10.1007/PL00006079. PMID 8703086.

- ^ a b Gould, Stephen Jay (2011). The Lying Stones of Marrakech. Harvard University Press. pp. 130–134. ISBN 978-0-674-06167-5.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. pp. 111–119, 270–271. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ «Espèce de». Reverso Dictionnnaire. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ De Wit, Hendrik C. D. (1994). Histoire du Développement de la Biologie, Volume III. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-2-88074-264-5.

- ^ a b Valentine, James W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. University of Chicago Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1874). Anthropogenie oder Entwickelungsgeschichte des menschen (in German). W. Engelmann. p. 202.

- ^ Hutchins, Michael (2003). Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). Gale. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7876-5777-2.

- ^ a b «Fisheries and Aquaculture». FAO. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b «Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens». The Economist. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59726-760-1.

- ^ «World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture» (PDF). fao.org. FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Eggleton, Paul (17 October 2020). «The State of the World’s Insects». Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-050035. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ «Shellfish climbs up the popularity ladder». Seafood Business. January 2002. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Cattle Today. «Breeds of Cattle at Cattle Today». Cattle-today.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Lukefahr, S. D.; Cheeke, P. R. «Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems». Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ «Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles». Natural Fibres. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ «Cochineal and Carmine». Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ «Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine». FDA. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ «How Shellac Is Manufactured». The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912–1954). 18 December 1937. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. (2003). «Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets». Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 29 (8): 925–938. doi:10.1081/ddc-120024188. PMID 14570313. S2CID 13150932.

- ^ Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8.

- ^ Munro, John H. (2003). Jenkins, David (ed.). Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-521-34107-3.

- ^ Pond, Wilson G. (2004). Encyclopedia of Animal Science. CRC Press. pp. 248–250. ISBN 978-0-8247-5496-9. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ «Genetics Research». Animal Health Trust. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ «Drug Development». Animal Research.info. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ «Animal Experimentation». BBC. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ «EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers». Speaking of Research. 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ «Vaccines and animal cell technology». Animal Cell Technology Industrial Platform. 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ «Medicines by Design». National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Fergus, Charles (2002). Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-618-7.

- ^ «History of Falconry». The Falconry Centre. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ King, Richard J. (2013). The Devil’s Cormorant: A Natural History. University of New Hampshire Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61168-225-0.

- ^ «AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae». AmphibiaWeb. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ^ Heying, H. (2003). «Dendrobatidae». Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ «Other bugs». Keeping Insects. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa. «So, you think you want a reptile?». Anapsid.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ «Pet Birds». PDSA. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ «Animals in Healthcare Facilities» (PDF). 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ The Humane Society of the United States. «U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics». Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ USDA. «U.S. Rabbit Industry profile» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Plous, S. (1993). «The Role of Animals in Human Society». Journal of Social Issues. 49 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.x.

- ^ Hummel, Richard (1994). Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-646-1.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (27 June 2014). «The top 10 animal portraits in art». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Paterson, Jennifer (29 October 2013). «Animals in Film and Media». Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-137-49639-3.

- ^ Warren, Bill; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4766-2505-8.

- ^ Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies You’ve Never Seen. ECW Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-55490-330-6.

- ^ a b Hearn, Lafcadio (1904). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^ a b «Deer». Trees for Life. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Louis, Chevalier de Jaucourt (Biography) (January 2011). «Butterfly». Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects. Gale, 2003.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (1989). Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: Israel Museum. p. 8. ISBN 978-965-278-083-6.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik (15 October 2015). «Why the humble cow is India’s most polarising animal». BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ van Gulik, Robert Hans. Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ^ Grainger, Richard (24 June 2012). «Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions». Alert. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Read, Kay Almere; Gonzalez, Jason J. (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 132–134.

- ^ Wunn, Ina (January 2000). «Beginning of Religion». Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612. S2CID 53595088.

- ^ McCone, Kim R. (1987). Meid, W. (ed.). Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen. Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz. Innsbruck. pp. 101–154.

- ^ Lau, Theodora (2005). The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes. Souvenir Press. pp. 2–8, 30–35, 60–64, 88–94, 118–124, 148–153, 178–184, 208–213, 238–244, 270–278, 306–312, 338–344.

- ^ Tester, S. Jim (1987). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 31–33 and passim. ISBN 978-0-85115-446-6.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Animals.

- Tree of Life Project Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Animal Diversity Web – University of Michigan’s database of animals

- Wildscreen Arkive – multimedia database of endangered/protected species

English[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (UK, US) enPR: ăn’ĭməl, IPA(key): /ˈænɪməl/

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English animal, from Old French animal, from Latin animal, a nominal use of an adjective from animale, neuter of animālis, from anima (“breath, spirit”). Displaced native Middle English deor, der (“animal”) (from Old English dēor (“animal”)), Middle English reother (“animal, neat”) (from Old English hrīþer, hrȳþer (“neat, ox”)).

Noun[edit]

animal (plural animals)

- (sciences) A eukaryote of the clade Animalia; a multicellular organism that is usually mobile, whose cells are not encased in a rigid cell wall (distinguishing it from plants and fungi) and which derives energy solely from the consumption of other organisms (distinguishing it from plants).

-

A cat is an animal, not a plant. Humans are also animals, under the scientific definition, as we are not plants.

- Synonyms: beast, creature

-

1650, Thomas Browne, “Of the Cameleon”, in Pseudodoxia Epidemica: […], 2nd edition, London: […] A[braham] Miller, for Edw[ard] Dod and Nath[aniel] Ekins, […], →OCLC, 3rd book, page 133:

-

It cannot be denied it [the chameleon] is (if not the moſt of any) a very abſtemious animall, and ſuch as by reaſon of its frigidity, paucity of bloud, and latitancy in the winter (about which time the obſervations are often made) will long ſubſist without a viſible ſuſtentation.

-

-

- (loosely) Any member of the kingdom Animalia other than a human.

- Synonym: beast

- (loosely, colloquial) Any land-living vertebrate (i.e. not fishes, insects, etc.).

-

2013 July-August, Henry Petroski, “Geothermal Energy”, in American Scientist, volume 101, number 4:

-

Ancient nomads, wishing to ward off the evening chill and enjoy a meal around a campfire, had to collect wood and then spend time and effort coaxing the heat of friction out from between sticks to kindle a flame. With more settled people, animals were harnessed to capstans or caged in treadmills to turn grist into meal.

-

-

- (figuratively) A person who behaves wildly; a bestial, brutal, brutish, cruel, or inhuman person.

-

My students are animals.

- Synonyms: brute, monster, savage

-

- (informal) A person of a particular type.

-

He’s a political animal.

-

- Matter, thing.

-

a whole different animal

-

Hyponyms[edit]

- See also Thesaurus:animal

Derived terms[edit]

- animalist

[edit]

- anima

- Animalia

- animalier

- animate

- animus

Translations[edit]

Etymology 2[edit]