Poets are the master of the written word.

Ask anyone their favorite writer, and chances are you’ll get a variety of answers. Some might say J.K. Rowling or Stephen King, and others might go with classics like William Shakespeare or Mark Twain. But one type of writer is universally revered: the poet. Poets are the true masters of the written word, and here’s why.

For starters, poets have a way with words that other writers can only dream of. They can take the simplest of terms and turn them into something beautiful that speaks to the soul. And they can do it using nothing more than the power of language. That’s a gift that very few people possess.

Second, poets can evoke emotion as no other writers can. They can make you laugh, cry, or think about the world differently. Their words have the power to change the way you see things, and that’s a rare talent indeed.

Finally, poets appreciate the economy of language that other writers would do well to learn from. A good poem says a lot with very few words, which all writers should aspire to achieve. After all, isn’t it better to say what you need to say in as few words as possible? Poets understand this better than anyone else.

Conclusion:

So next time you’re looking for an excellent writer to read, check out some poetry. You might find that it’s your new favorite genre!

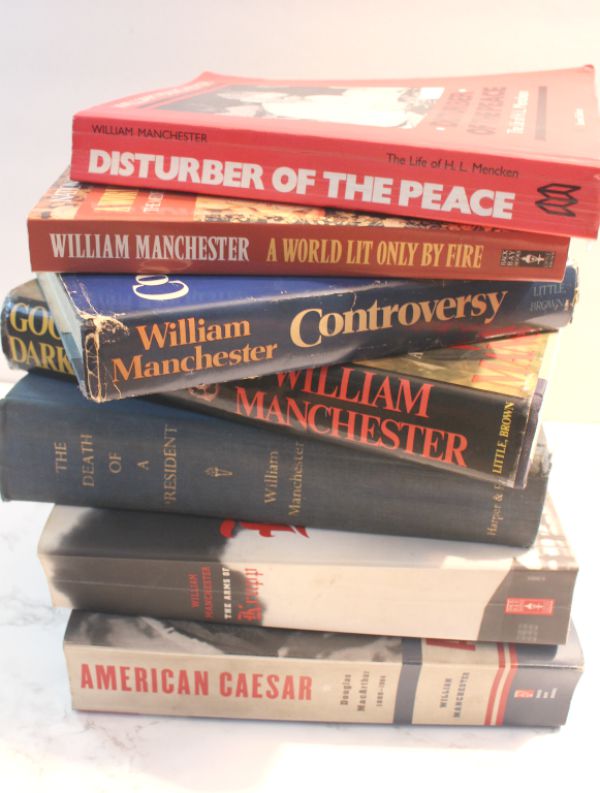

In my last post here, I spoke of my favorite author, Stephen King. That was in the realm of fiction, though. I also mentioned and told a little about my most favorite non-fiction author, William Raymond Manchester, a brilliant historian and biographer. And between Manchester and King, there are no other authors that have as many books in my personal library than them.

Surprisingly, being the avid reader and wannabe historian I am, I’d never heard of William Manchester. It was only by serendipity that I discovered Manchester. I went to my favorite used-book store in search of Stephen King book and ran across a two-volume book set by William Manchester entitled The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972. What caught my attention was the dates, ’32 thru ’72, spanning the beginning of my mother’s life in the Great Depression through my teenage years and the beginning of the fall of Tricky Dick President Nixon. So I couldn’t help but grab ’em up and to my delight, looking back on it, that was the beginning of a great relationship between me and Manchester.

The Glory and the Dream chronicles the lives of those whom Tom Brokaw later dubbed the “greatest generation”, who then fathered the baby boomers after WWII, then followed those two generations through the placid ’50’s, into the swinging ’60’s, finishing with the turbulent ’70’s. This book captures all facets of those decades in a way I’ve never seen done better and I’ve probably read it at least a dozen times without boredom.

William Manchester served in the Pacific with the Marines in WWII, following in the footsteps of his father who had been a Marine in WWI. He was nearly mortally wounded on Okinawa. Later on, he met another wounded vet, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who had become President of the United States. He then wrote the book Portrait of a President. That link led to Jacqueline Kennedy commissioning Manchester to produce an account of the assassination, which led to one of Manchester’s most sold works.

After the war, Manchester returned to college and earned his master’s degree, writing his thesis on H.L. Mencken whom he met while working as a reporter at The Baltimore Sun.

Mencken, who came to be known as the “sage of Baltimore, was a journalist, satirist, critic, political pundit and as a scholar he penned The American Language, a multi-volume work on how the English language is spoken in the United States. But it was his satirical reporting on the Scopes Trial, which he dubbed the “Monkey Trial”, which earned him notoriety. He actually dubbed himself a “conservative anarchist”.

Manchester and Mencken became good friends and Mencken mentored Manchester, encouraging him to write. That led to Manchester’s first book which was, ironically, Disturber of the Peace: The Life of H.L Mencken, following up on what he wrote for his master’s thesis. He then wrote four novels, interspersed with his second historical work, A Rockefeller family Portrait, From John D. to Nelson. But after his fourth novel, he concentrated on history.

Such works include Portrait of a President: John F. Kennedy in Profile; The Death of a President: November 20 – 25; The Arms of Krupp: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Dynasty that Armed Germany at War; as mentioned earlier, The Glory and the Dream : A Narrative History of America, 1932–1972; Controversy and Other Essays in Journalism; American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964; Goodbye Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War; One Brief Shining Moment: Remembering Kennedy; A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance—Portrait of an Age; and his last project before his death was his three-volume biography of Churchill, The Last Lion, of which he’d only completed two volumes, turning the last one over to his writer friend Paul Reid to complete after having suffered a couple of strokes. Of these, my most favorites, including The Glory and the Dream, is Goodbye Darkness and The Death of a President.

Goodbye Darkness is autobiographical, based around his late ’70’s journey across the Pacific visiting the islands the Marines fought their bloody battles on in WWII, prompted by the nightmares he began having twenty-some years after his experiences on Okinawa. In those dreams, he’s visited by his youthful alter ego whom he dubbed “the sarge”, who was questioning just what had happened in those years since his bloody baptism of fire and near death. What he was describing about those nightmares is what later came to be diagnosed as PTSD and it’s interesting that he didn’t suffer from it until long after the fact of his exposure to the events that led to the dreams. But at the journey’s end on the island he fought, Okinawa, the final story is told that helps in understanding what eventually led to his nightmares.

But of them all, I consider The Death of a President to be his magnum opus. If anything, Manchester was a consummate researcher to go along with his prolific writing, sometimes working in fifty hour stretches before stopping, of which he exclaimed that he loved doing. All of his books are full of great detail and The Death of a President is a painstakingly detailed account of JFK’s final two days of life, followed by the three days of national disbelief and mourning, ending on midnight of the Monday on the day of his burial when Jackie and his brother Robert placed a bouquet by the eternal flame. It’s a powerful work, and if you lived through those historic and traumatic four days and have not ever read this book, you’d do well to check it out for it will give you a true picture of just what went down during that tragic time.

As an interesting aside, due to his research and study of Oswald’s personality and psychology, along with the fact that he and Oswald both had training as Marine riflemen, he concluded that Oswald had acted on his own with no accomplice. And in a 1992 letter to the New York Times, Manchester, in an attempt to put to rest any idea of a conspiracy, wrote: “Those who desperately want to believe that President Kennedy was the victim of a conspiracy have my sympathy. I share their yearning…But if you put the murdered President of the United States on one side of a scale and that wretched waif Oswald on the other side, it doesn’t balance. You want to add something weightier to Oswald. It would invest the President’s death with meaning, endowing him with martyrdom. He would have died for something. A conspiracy would, of course, do the job nicely. Unfortunately, there is no evidence whatever that there was one.”

It’s sad that he was unable to finish his last work about Churchill due to having had a couple of strokes. And before his friend was able to complete the final volume, Manchester passed away. I vividly remember hearing the news of his death. It struck me extra hard because I was halfway through rereading Goodbye Darkness for probably the tenth time. I felt as if I’d lost a lifelong friend. I’ve yet to read that final volume on Churchill; it just wouldn’t be the same. But I owe it to his memory and need to keep that flame of literary friendship alive. And that’s the thing about books and the words that make them up: though the author may be dead and long gone, they will live forevermore as long as there are libraries and guys like me who have a love of the written word. So…so long, Bill. But we will meet again as soon as I make it to the library and pick up volume three of The Last Lion, and I can hardly wait to renew our acquaintance.

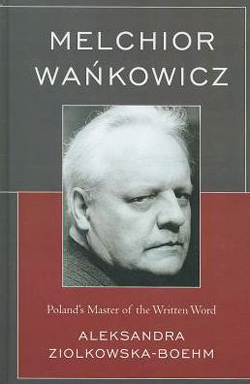

In Melchior Wankowicz: Poland’s Master of the Written Word, Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm examines the life and writing of famous Polish writer Melchior Wankowicz, author of legendary work «The Battle of Monte Cassino.» Melchior Wankowicz was famous for creating his theory of reportage, i.e. the «mosaic method» where the events of many people were implanted into the life of one person. In this book, Ziolkowska-Boehm offers a critical examination of Wankowicz’s work informed by her experiences as his private secretary. Her access to the author’s personal archives shed new light on the life and work of the man considered by many to be «the father of Polish reportage.»

268 pages, ebook

First published January 1, 2013

About the author

Pisarka, w latach 1972–1974 asystentka i sekretarka Melchiora Wańkowicza. Publikuje w polskiej i amerykańskiej prasie. Od 1990 mieszka w Wilmington, Del.

April 16, 2015

TheNation.com sportswriter Dave Zirin pays tribute to a legendary author whose powerful writings included meditations on the intersection of sports and politics.

IN THE April 12 season premiere of the HBO series Game of Thrones, two of the more admirable characters are speaking about the future and one says, «Perhaps we’ve grown so used to horror, we assume there’s no other way.» I mumbled to no one in particular, «Some screenwriter’s been reading their Galeano.»

The next day, the news broke that Eduardo Galeano, that master of the written word who could integrate magical-reality lyricism into the all-too-real history of empire without breaking a sweat, had died of cancer at 74. No, I’m not a future-telling Warg, I don’t have a third eye, or the soul of a raven (or whatever the hell Game of Thrones reference is appropriate here). Galeano had been on my mind, as his failing health had been well known, and I’d felt the weight of debt that we owe the Uruguayan legend. It’s a debt owed by anyone who refuses to «grow used to horror» as an act of conscious resistance. It’s a debt owed by those who choose to witness our sick world from the carnage in Gaza to the #FuckYourBreath killing of Eric Harris and don’t become lost in the cynicism of a society that sometimes seems intoxicated by its own inhumanity. It is impossible to read Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America and be not only distraught over the bloody legacy of U.S. imperialism but also hopeful at the ways a brave, if fruitless, resistance can resemble the lush vitality of epic poetry.

I also owe a very particular, specific debt to Galeano. Yes, Galeano is known for his writings on empire. But he also penned what, for my money, is the finest book that sits at the intersection of sports and politics: Soccer in Sun and Shadow. In just 300 pages, Galeano spins a social history of the sport in achingly artistic sketch lines, some broad, others exact. It’s like a rollicking but incisive freestyle rhyme expressed through a massive quill pen. The art of his writing allows him to explain just what makes the beautiful game so endlessly alluring in spite of the ugliness that surrounds it. He writes, «I go about the world, hand outstretched, and in the stadiums I plead: ‘A pretty move, for the love of God.’ And when good soccer happens, I give thanks for the miracle, and I don’t give a damn which team or country performs it.» That’s Galeano: he made you believe it was not only possible to be both an internationalist and fan, but also a necessity if you hope to have your feet planted in this world with your mind on the next.

LAST SUMMER, a dream came true when my hero, the sports/politics writer Mike Marqusee, reviewed my World Cup/Olympics book Brazil’s Dance with the Devil and immediately «got» that «Eduardo Galeano is the book’s presiding spirit.» Throughout the book, I started almost every chapter with a Galeano quote, mainly because there is no one more quotable. Anytime you can write a book and frame chapters with phrases like, «There are no right angles in Brazilian soccer, just as there are none in the Rio Mountains,» or, «In the colonial and neocolonial alchemy, gold changes into scrap metal and food into poison,» or, «Where opulence is most opulent…misery is most miserable,» you do it.

Quoting Galeano to frame chapters was a method to allow just a little of his diamond dust to grace my own pages. There was a thrill in bringing Galeano’s ability to make words dance to my own pages, which upon rereading still make me feel as light-headed as a clod-footed student being taken for a whirl by Josephine Baker. But that wasn’t all. As Marqusee wrote, Galeano was also meant to be the book’s «presiding spirit,» the person who could embrace how sports can express the best and worst angels of our nature: how it can be used as an instrument of exploitation while also wielded as a weapon of hope.

Now, it is just nine months later, and both Marqusee and Galeano are dead, both killed by cancer. The obvious instinctive takeaway from this is «fuck cancer» and fuck all in this world that is turning our bodies into wars of competing poisons. But when you exhale and look at the contributions of both writers, there is a different legacy: It’s the dare. They dared in a world of sound bites to compose graceful sentences, plump with metaphors so thick you could get lost and found between the capital letter and the period. They taught us that it’s better to fail at writing something indelible than to be like everyone else. And most of all, they taught that no one should ever make you feel ashamed or embarrassed for refusing to acclimate yourself to the horrors of the present. That, above all else, is the debt we owe the memory of Eduardo Galeano. Whether you see yourself as writing history or making history, fortune favors the bold. And if you want to find a place in the collective memory, always strive to be memorable.

First published at The Nation.

By Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm

Lexington Books, 2013

I was eleven years old when I witnessed a lively and rather agitated conversation that my parents had during supper. With a lot of excitement in her voice my mother recounted how she went to a bookstore after work and came across a famous Polish writer, Melchior Wańkowicz, who had just been released from prison by the communist regime in Poland.

Bookstores in Poland have always been and still are full of readers and the writer was literally encircled by them as soon as he entered the bookstore. Everybody wanted to shake his hand, ask a question or just look at him from a close distance.

I sensed that there was something unusual about this encounter and I could appreciate the thrill of meeting a famous writer but it took me a couple more years to fully comprehend the magnitude of arresting and putting on trial one of the most prominent and most popular contemporary Polish writers just for sending abroad a paper – “Speech-Project” – that was then broadcast by Radio Free Europe. The paper contained material that in the eyes of the communist regime slandered social and political relations in Poland. The “Speech Project” prepared by Wańkowicz followed “Letter 34,” a protest signed by thirty four writers (including Wańkowicz) against a government decision to limit the amount of paper allotted for printing books and newspapers. (At that time book production in Poland was already at the lowest level among the socialist countries.)

The trial of Melchior Wańkowicz became a cause célèbre. Eleven years after the death of Stalin, arresting and prosecuting a seventy-two-year old prominent Polish writer and public favorite was highly odd practice, even by the communist standards of justice. Virtually all western newspapers, including Time Magazine, published extensive commentary about the regime’s ridiculous prosecution of Wańkowicz.

The defense called some renowned and respected Polish writers and intellectuals as witnesses. Alas, one of them, Kazimierz Kozniewski, whom Wańkowicz considered a close friend since before the war, also a friend of the writer’s two daughters, testified against him. Kozniewski was not only a traitor but also a secret agent and one of the most devoted employees of the Security Office and then Security Service in the history of Communist Poland.

The trial lasted three days and ended with a sentence of three years in prison. Facing harsh criticism in Poland and abroad and numerous interventions by famous writers and intellectuals as well as prominent politicians such as Robert Kennedy, the communist regime in Warsaw backed off and freed Wańkowicz.

Obviously, when I listened to my parents’ conversation about the writer, forty years ago, a lot of these facts were unknown since the trial was held in camera and only very general information was provided to the public by the Polish mass media. Many years after Wańkowicz’s death, new evidence and testimonies began emerging and thanks to meticulous work and painstaking efforts by the independent scholar and writer Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm, both Polish and English readers can now appreciate the most recent book about one of Poland’s greatest writers.

Published by Lexington Books, Melchior Wańkowicz – Poland’s Master of the Written Word, is not merely a well documented account of Wańkowicz’s struggle with communist justice system. (Ziolkowska-Bohem had already written a separate book on this subject in 1990 available in Polish only.) It is a captivating although somehow eclectic portrait of a great humanist with a pragmatic approach to life, a prolific hard working writer, bon vivant, thinker, husband, father and most of all a fabulous reporter and storyteller.

The book is not, however, a biography. Each of its eleven chapters can be read separately. I devoured it in no time as I did almost all of Wańkowicz’s books. Yet, when the editors of CR asked me if I could write a review of Ziolkowska-Boehm’s “Poland’s Master of the Written Word” I initially hesitated. Some time ago, while teaching a course, “Introduction to Polish Studies,” at McGill University I asked students (some of them of Polish origin) if they had read or at least heard of the most famous Polish writers: Stanisław Lem, Sławomir Mrozek or Nobel Prize laureates Henryk Sienkiewicz and Władysław Reymont whose books were translated into most modern languages and published in many countries, the answers were not very encouraging.

I decided to read some of Wańkowicz’s books again before sharing my humble opinion with readers of CR on Ziolkowska-Boehm’s latest work and try to assess if the contemporary generation of Polish literature aficionados could relate to them. I firmly believe that both young and older readers would find most of Wańkowicz’s works not only fascinating but probably more appealing (particularly to the Polish diaspora in the USA and Canada), than the books of his famous predecessors.

It suffice to open “Tworzywo” (“Matter”) – Wańkowicz’s reportage from Canada where he travelled 18,000 miles to write stories about Polish immigrants who succeeded in their new country despite numerous setbacks, severe hardship and misery. It almost reads like a fiction but as most of his writings, “Tworzywo” is based on facts. As Ziolkowska-Boehm writes in Poland’s Master of Written Word: “Tworzywo” includes many real events, statistical data, and human histories; in this book, even the cited letters of one protagonist – Bombik – are authentic. We find real conversations, facts, and people at every step.

Aleksandra-Ziolkowska-Boehm is an unrivalled connoisseur of Wańkowicz’s works. During the last two years of the writer’s life she was his secretary and ultimately became his friend and associate. She had unlimited access to his personal archives but also the privilege to participate in his private everyday life. She took full advantage of this extremely rare opportunity that she now shares with us in her excellent book full of interesting, sometimes hilarious sometimes heartbreaking details about Wańkowicz’s life, his entourage and, last but not least, about the origin of some his works.

Here is one example, explaining where the title of my favourite Wańkowicz book comes from: “He also gave the book a final title “La Fontaine’s Carafe.” He chose it to emphasize the diversity and objectivism of his views and opinions. The title came from an anecdote. La Fontaine was once asked to settle a dispute arisen among the revelers gathered in the inn. In the middle of the table there stood a crystal decanter with wine. Sunrays were coming through the window and reflecting off the carafe. One of the revelers said they were reflected red. Another denied, saying they were blue. The third one said they were pink. When asked, La Fontaine went around the table and said that each of the men was right: depending on the side you were looking from, as the sun refracted in the carafe, it showed different colors. What was most important, as he said, was to see all the colors together, to understand there wasn’t just one.”

Melchior Wańkowicz – Poland’s Master of the Written Word comes at a good time. The author of Battle of Monte Cassino was one of the most famous Polish writers in the last century. I am convinced that thanks to Aleksandra Ziolkowska-Boehm latest book, Melchior Wańkowicz will always have plenty of readers.

CR

A graduate of Warsaw University’s Department of Slavic Studies,

Leszek Adamczyk worked as a journalist in Polish Radio and TV in the Section of Literature and Culture covering cultural events in Poland and abroad, writing plays for radio-theater, book reviews and essays. After emigrating to Canada, he worked as translator for the Government of Canada, as a lecturer (language instructor) at McGill University, and as a correspondent for the Warsaw daily » Życie.» He currently works for the Government of Québec.