Etymological Survey of the Modern English Language.

According to the origin, the word-stock may be subdivided into two main groups: one comprises the native elements; the other consists of the borrowed words.

Native Words

The term native denotes words which belong to the original English stock known from the earliest manuscripts of the Old English period. They are mostly words of Anglo-Saxon origin brought to the British Isles in the 5th century by Germanic tribes.

Linguists estimate the Anglo-Saxon stock of words as 25-30 per cent of the English vocabulary. The native word-stock includes the words of Indio-European origin and the words of Common Germanic origin. They belong to very important semantic groups.

The words of Indio-European origin (that is those having cognates in other I-E. languages) form the oldest layer. They fall into definite semantic groups:

terms of kinship: father, mother, son, daughter, brother;

words denoting the most important objects and phenomena of

nature: sun, moon, star, water, wood, hill, stone, tree;

names of animals and birds: bull, cat, crow, goose, wolf;

parts of human body: arm, eye, foot, heart;

the verbs: bear, come, sit, stand, etc;

the adjectives: hard, quick, slow, red, white.

Most numerals belong here.

The words of the Common Germanic stock, i.e. words having cognates in German, Norwegian, Dutch and other Germanic languages are more numerous. This part of the native vocabulary contains a great number of semantic groups. Examples:

the nouns are: summer, winter, storm, ice, rain, group, bridge,

house, shop, room, iron, lead, cloth, hat, shirt, shoe, care,

evil, hope, life, need, rest;

the verbs are: bake, burn, buy, drive hear, keep, learn, make, meet,

rise, see, send, shoot, etc;

the adjectives are: broad, dead, deaf, deep.

Many adverbs and pronouns belong to this layer, though small in number (25-30 per cent of the vocabulary).

The Common Germanic words and the verbs of the Common Indo-European stock form the bulk of the most frequent elements used in any style of speech. They constitute not less than 80 per cent of the most frequent words listed in E.L. Thorndike and I. Lorge`s dictionary “The Teacher`s Wordbook of 30,000 Words, N.Y.1959, p.268).

Investigation shows that the Anglo-Saxon words in Modern English must be considered very important due to the following characteristics. All of them belong to very important semantic groups. They include most of the auxiliary and modal verbs (shall, will, should, would, must, can, may, etc.), pronouns (I. he, you, his, who, whose, etc.), prepositions (in. out, on, under), numerals (one, two) and conjunctions (and, but). Notional words of native (Anglo-Saxon) origin include such groups as words denoting parts of the body, family, relations, natural phenomena and planets, animals, qualities and properties, common actions, etc.

Most of native words are polysemantic (man, head, go, etc.)

Most of them are stylistically neutral.

They possess wide lexical and grammatical valency, many of them enter a number of phraseological units.

Due to the great stability and semantic peculiarities the native words possess great word-building power.

Borrowings (Loan Words)

A borrowed (loan) word is a word adopted from another language and modified in sound form, spelling, paradigm or meaning according to the standards of English.

According to Otto Jespersen loan-words are “the milestones of philology, because in a great many instances they permit us to fix approximately the dates of linguistic changes”. But they may be termed “the milestones of general history” because they show the course of civilization and give valuable information as to the inner life of nations.

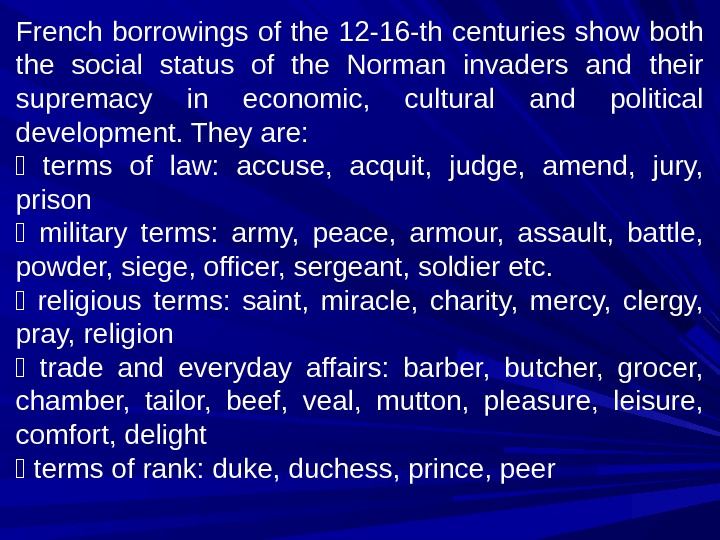

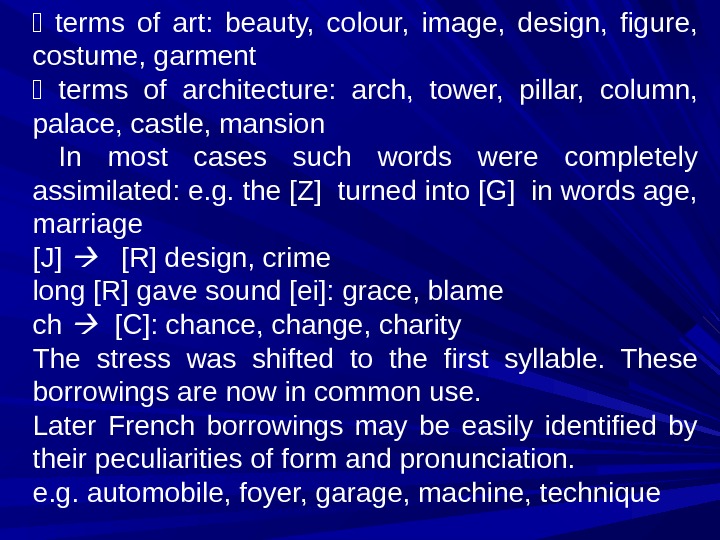

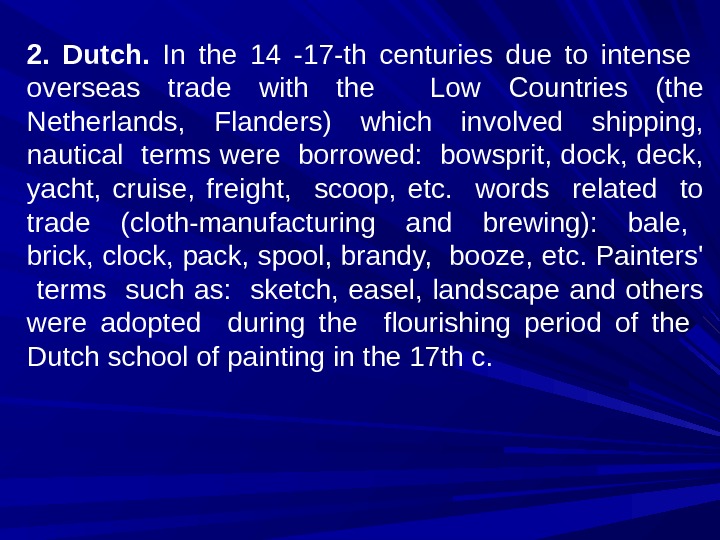

Through its history the English language came in contact with many languages and borrowed freely from them. The greatest influx of borrowings mainly came from Latin, French and Old Norse (Scandinavian). Latin was for a long time used in England as the language of learning and religion. Old Norse and French (its Norman dialect) were the languages of the conquerors: the Scandinavians invaded the British Isles and merged with the local population in the 9th, 10th and the first half of the 11th century. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 Norman French was the language of the upper classes, of official documents and school instruction from the middle of the 11th century to the end of the 14th century.

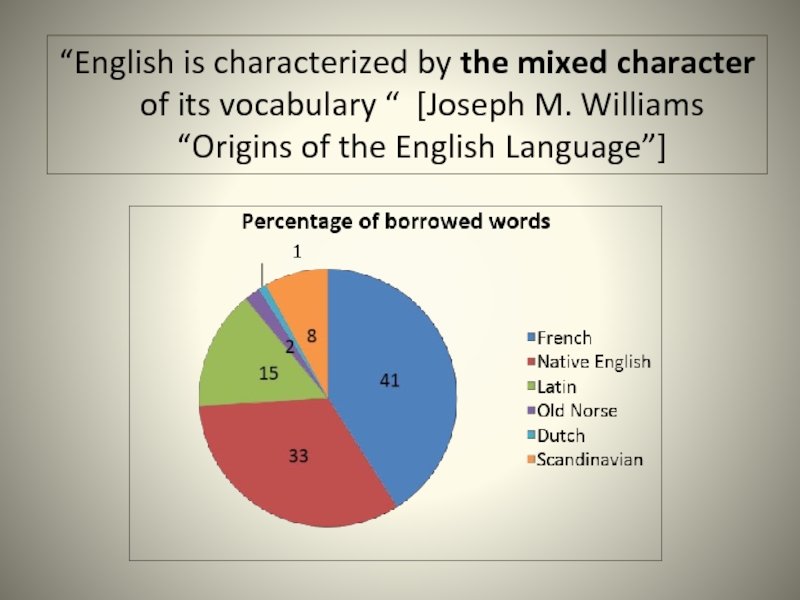

Etymologically the English vocabulary is said to have a particularly mixed character. Therefore some linguists (L.P.Smith, I.H.Bradley) consider foreign influence to be the most important factor in the history of English. Other linguists (Ch.Hockett, J.A.Sheard) and our linguists, on the contrary, point out the stability of the grammar and phonetic system of the English Language and consider it necessary to examine the volume and role and the comparative importance of native and borrowed elements in the development of the English vocabulary.

The greatest number of borrowings has come from French. Borrowed words refer to various fields of social-political, scientific and cultural life. About 41 per cent of them are scientific and technical terms.

L.P.Smith calls English «half-sister» to the Romance languages.

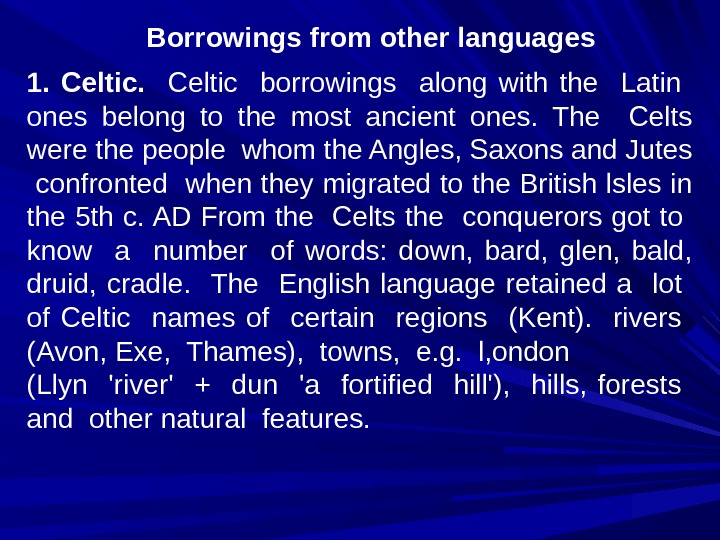

The number and character of borrowings depend on many factors: on the historical conditions, on the nature and length of the contacts and also on the genetic and structural proximity of languages concerned. The closer the language the deeper and more versatile is the influence. Thus, from the Scandinavian languages, which were closely related to Old Eng¬lish, some classes of words were borrowed that could not have been adopted from non-related or distantly related languages: the personal pro¬nouns: they, their, them; also same, till, though, fro (adv).

Sometimes words were borrowed to fill in gaps in the vocabulary. Thus, the English borrowed Latin, Greek, Spanish words paper, tomato, potato when these vegetables were first brought to England and because the English vocabulary lacked words for denoting these new objects.

Borrowings enter the language in two ways: through oral speech and through written speech. Oral borrowings took place chiefly in the early periods of history, in recent times, written borrowings did. Words borrowed orally (L. Street, mill, inch) are usually short and undergo more changes in the act of adoption. Written borrowings (e.g. French communi¬que, belles-letres, naivete) preserve their spelling, they are often rather long and their assimilation is a long process.

The terms «source of borrowing» and «origin of borrowing» should be distinguished. The first denotes the language from which the loan was taken into English. The second denotes the language to which the word may be traced:

E.g. paper

Words like paper, pepper, etc. are often called by specialists in the history of the language «much-travelled words» which came into English passing through several other languages and not by means of direct bor¬rowing.

Though the borrowed words always undergo changes in the proc-ess of borrowing, some of them preserve their former characteristics for a long period. This enables us to recognize them as the borrowed element. Examples are:

the initial position of the sounds [v], [d], [z] is a sign that the word is not native: vacuum (Lat), valley (FR.), volcano (Ital.), vanilla(Sp.), etc;

may be rendered by «g» and «j» gem (Lat), gemma, jewel (O. Fr.), jungle (Hindi), gesture (Lat), giant (O.Fr.), genre, gendarme (Fr.);

the initial position of the letters «x», «j» «z» is a sign that the word is a borrowed one: zeal (Lat), zero (Fr.), zinc (Gr.), xylophone (Gr.);

the combinations ph, kh, eau in the root: philology (Gr.), khaki (Indian), beau (Fr.); «ch» is pronounced [k] in words of Greek origin: echo, school, [S] in late French borrowings: machine, parachute; and [tS] in native words and early borrowings.

The morphological structure of the word may also betray the for-eign origin of the latter: e.g. the suffix in violencello (Ital.) polysyllabic words is numerous among borrowings: government, condition, etc.

Another feature is the presence of prefixes: ab-, ad-, con-, de-, dis-, ex-, in-, per-, pre-, pro-, re-, trans- /such words often contain bound stems.

The irregular plural forms: beaux/from beau (Fr), data/from datum (Lat).

The lexical meaning of the word: pagoda (Chinese).

Assimilation of Borrowings

Assimilation of borrowings is a partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical or morphological standards of the receiving lan¬guage and its semantic structure.

Since the process of assimilation of borrowings includes changes in sound-form, morphological structure, grammar characteristics, meaning and usage, three types of assimilation are distinguished: phonetic, gram¬matical and lexical assimilation of borrowed words.

Phonetic assimilation comprises changes in sound form and stress. Sounds that were alien to the English language were fitted into its scheme of sounds. For instance, the long [e] in recent French bor¬rowings are rendered with the help of [ei:] cafe, communiquй, ballet; the consonant combinations pn, ps in the words pneumonia, psychology of Greek origin were simplified into [n] and [s] since pn and ps never occur in the initial position in native English words. In many words (especially borrowed from French and Latin) the accent was gradually transferred to the first syllable: honour, reason began to be stressed like father, brother.

Grammatical assimilation. As a rule, borrowed words lost their former grammatical categories and influence and acquired new grammati¬cal categories and paradigms by analogy with other English words, as for example: the Russian borrowing ‘sputnik’ acquired the paradigm sputnik, sputnik’s, sputniks, sputniks` having lost the inflections it has in the Russian language.

Lexical assimilation. When a word is taken into another language its semantic structure as a rule undergoes great changes. Polysemantic words are usually adopted only in one or two of their meanings. For ex¬ample the word ‘cargo’ which is highly polysemantic in Spanish, was bor¬rowed only in one meaning — «the goods carried in a ship». In the recipient language a borrowing sometimes acquires new meanings. E.g. the word ‘move’ in Modern English has developed the meaning of ‘propose’, ‘change one’s flat’, ‘mix with people’ and others that the corresponding French word does not possess.

There are other changes in the semantic structure of borrowed words: some meanings become more general, others more specialized, etc. For instance, the word ‘umbrella’ was borrowed in the meaning of ‘sunshade’ or ‘ parasole'(from Latin ‘ ombrella- ombra-shade’).

Among the borrowings in the English word-stock there are words that are easily recognized as foreign (such as decollete, Zeitgeist, graff to and there are others that have become so thoroughly assimilated that it is ex¬tremely difficult to distinguish them from native English words.(There words like street, city, master, river).

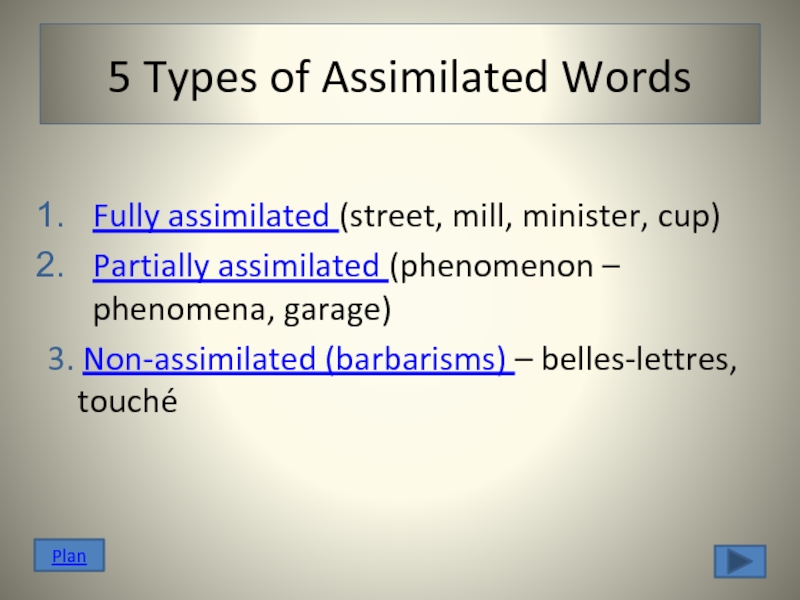

Unassimilated words differ from assimilated words in their pronun¬ciation, spelling, semantic structure, frequency and sphere of application. However there is no distinct borderline between the two groups. Neither are there more or less comprehensive criteria for determining the degree of assimilation. Still it is evident that the degree of assimilation depends on the length of the time the word has been used in the receiving language, on its importance and its frequency and the way of borrowing (words borrowed orally are assimilated more completely and rapidly than those adopted through writing). According to the degree of assimilation three groups of borrowings can be suggested: completely assimilated bor¬rowings, partially assimilated borrowings and unassimilated borrow¬ings or barbarisms.

The third group is not universally recognized, the argument being that barbarisms occur in speech only and not enter the language.

I. Completely assimilated words are found in all the layers of older borrowings: the first layer of Latin borrowings (cheese, street, wall, and wing); Scandinavian borrowings (fellow, gate, to call, to die, to take, to

want, happy, ill, low, wrong); early French borrowings (table, chair, finish, matter, dress, large, easy, common, to allow, to carry, to cry, to consider).

The number of completely assimilated words is many times greater than the number of partly assimilated ones. They follow all morphologi¬cal, phonetical and orthographic standards.

II. The partly (partially) assimilated words can be subdivided

into groups:

a). Borrowed words not assimilated phonetically: e.g. machine, cartoon, police (borrowed from French) keep the accent on the final syl¬lable; bourgeois, mйlange contain sounds or combinations of sounds that are not standard for the English language and do not occur in native words ([ wa:],the nasalazed [a]);

b). Borrowed words not completely assimilated graphically. This group is fairly large and variegated. These are, for instance, words bor¬rowed from French in which the final consonants are not pronounced: e.g. ballet, buffet, corps. French digraphs (ch, qu, ou, ete) may be re¬tained in spelling: bouquet, brioche.

c). Borrowed words not assimilated grammatically, for example, nouns borrowed from Latin and Greek which keep their original forms: crisis-crises, formula-formulae, phenomenon-phenomena.

d). Borrowed words not assimilated semantically because they de-note objects and notions peculiar to the country from which they come: sombrero, shah, sheik, rickchaw, sherbet, etc.

III. The so-called barbarisms are words from other languages used

by English people in conversation or in writing but not assimilated in any

way, and for which there are corresponding English equivalents, e.g.: Italian

‘ciao’ (‘good-bye’), the French ‘affiche’ for ‘placard’, ‘carte blanche’

(‘freedom of action’), ‘faux pas’ (‘false step’).

Translation Loans and Semantic Loans

Alongside loan words proper there are translation loans (or calques) and semantic loans.

Translation loans are words and expressions formed from the material already existing in the English language, but according to pat¬terns, taken from other languages, by way of literal morpheme-for-morpheme translation. One of the earliest calques in the vocabulary of the English language is ‘Gospel’ (OE god-spell-‘евангелие’ literally ‘благая весть’) which is an exact reproduction of the etymological structure of the Greek euggelion, ‘ благая весть’, borrowed into English through Latin. Other examples are: ‘mother tongue* from Latin ‘lingua materna’ (родной язык), ‘it goes without saying’ from French ‘cela va sans dire’ (само собой разумеется).

The number of translation loans from German is rather large:

‘chain-smoker’ from ‘Kettenrauchen’ (заядлый курильщик);

‘world famous’ from ‘weltberuhmt’ (всемирно известный);

‘God’s acre’ from ‘Gottesacker’ (кладбище literally божье по¬ле);

‘masterpiece’ from ‘Meisterstuk'(шедевр);

‘Swan song’ from ‘Schwanengesang’ (лебединая песня);

‘superman’ from ‘Ubermensoh’ (сверхчеловек);

‘wonder child’ from ‘Wunderkind’.

There are a few calques from the languages of American Indians: ‘pale-face’ (бледнолицый); ‘pipe of peace’ (трубка мира); ‘War¬path’ (тропа войны); ‘war-paint’ (раскраска тела перед походом).

They are mostly used figuratively.

Calques from Russian are rather numerous. They are names of things and notions reflecting Soviet reality:

‘local Soviet’ (местный совет);

‘self-criticism’ (самокритика);

‘Labour-day’ (трудодень);

‘individual peasant’ (единоличник);

‘voluntary Sunday time’ (воскресник).

The last two are considered by N.N. Amosova to be oases of explana-tory translation.

Semantic borrowing is the development of a new meaning by a word due to the influence of a related word in another language, e.g. the English word ‘pioneer` meant `первооткрыватель` /now, under the influence of the Russian word ‘пионер’ it has come to mean ‘член детской коммунистической организации’.

Semantic loans are particularly frequent in related languages. For example, the Old English ‘dwellan’ (блуждать, медлить) developed into ‘dwell` in Modern English and acquired the meaning ‘жить’ under the influence of the Old Norse ‘dwelja’ (‘жить’). The words ‘bread’ (‘кусок хлеба’ in OE), ‘dream’ (‘радость’ in OE), ‘plough’ (‘мера земли’ in OE) received their present meanings from Old Norse.

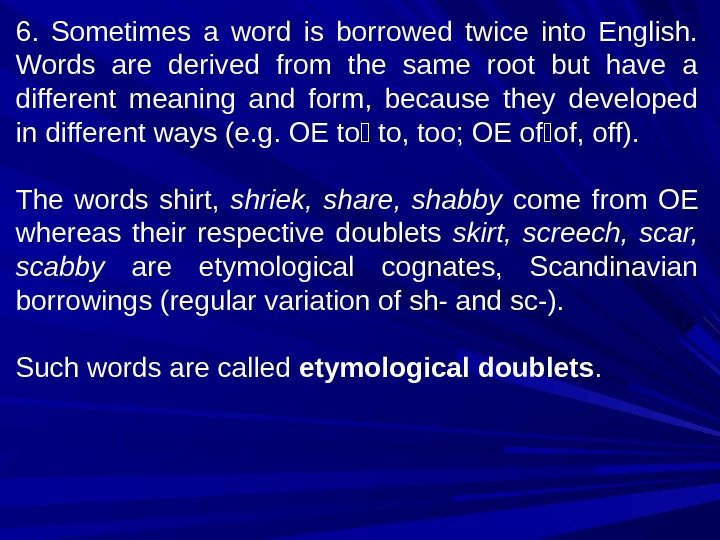

Etymological Doublets.

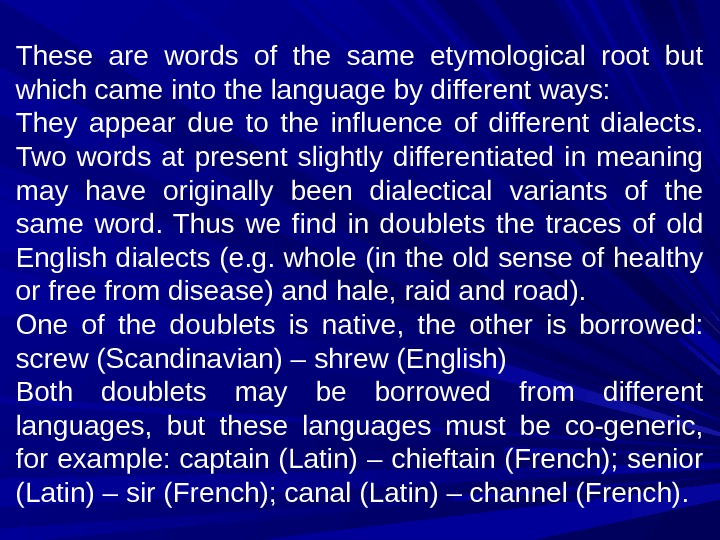

Etymological doublets are two or more words of the same lan¬guage which were derived by different routes from the same basic word, but differing in meaning and phonemic shape. For example, the word ‘fact’ (‘факт, действительность’) and ‘feat’ (‘подвиг’) are derived from the same Latin word ‘facere’ (‘делать’) but ‘fact’ was borrowed directly from Latin and ‘feat’ was borrowed through French.

In modern English there are doublets of Latin, Germanic and na¬tive origin. Many Latin doublets are due to the different routes by which they entered the English vocabulary: some of the words are di¬rect borrowings; others came into English through Parisian French or Norman French.

For example, the words ‘major’, ‘pauper’, senior’ are direct bor¬rowings from Latin, while their doublets ‘mayor’ (‘майор’), ‘poor’ (‘бедный’), ‘.sir’ (‘сэр’) came from French.

The words ‘chase’ (‘гнаться, преследовать’), ‘chieftain’ (‘вождь/клана’), ‘guard’ (‘охрана/стража’) were borrowed into Mid¬dle English from Parisian French, and their doublets ‘catch’ (‘поймать’), ‘captain’ (‘капитан’), ‘ward’ (‘палата/больничная’) came from Norman French.

The doublets ‘shirt’ (‘рубашка’) — ‘skirt’ (‘юбка’), ‘shrew’ (‘сварливая женщина’) — ‘screw’ (‘винт, шуруп’), ‘schriek’ (‘вопить, кричать’) — ‘screech’ (‘пронзительно кричать’) are of Germanic ori¬gin. The first word of the pair comes down from Old English whereas the second one is a Scandinavian borrowing.

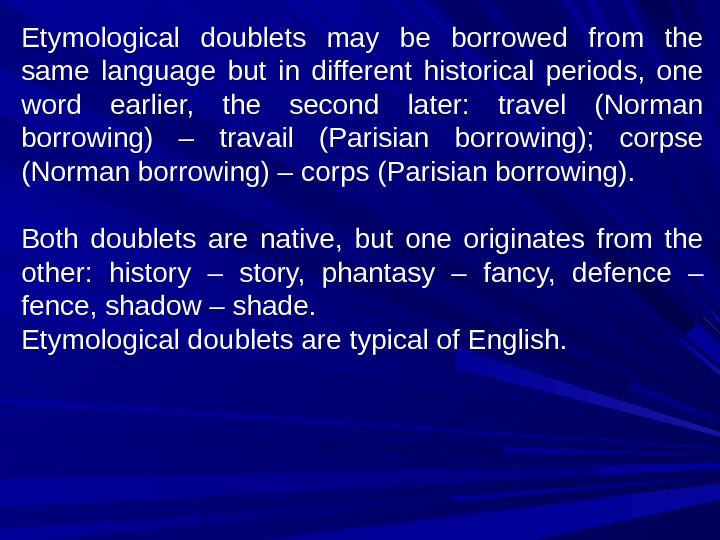

Examples of native doublets are ‘shadow’ (‘тень’) and ‘shade! Both are derived from the same Old English word ‘sceadu’. ‘Shade’ is developed from the Nominative case, ‘sceadu’ is derived from oblique ease ‘sceadwe’. The words ‘drag’ and ‘draw’ both come from Old English ‘dragan’ (‘тащить’)

Etymological doublets also arise as a result of shortening when both the shortened form and the full form of the word are used:

‘defense’ — ‘защита’ — ‘fence’ — »забор’;

‘history’ — ‘история’ — ‘story’ — ‘рассказ’.

Examples of ETYMOLOGICAL TRIPLETS (i.e. groups of three words of common root) are few in number:

hospital (Lat.) — hostel (Norm.Fr.) — hotel (Par.. Fr.);

to capture (Lat.) — to catch (Norm. Fr.) — to chase (Par. Fr.).

Morphemic Borrowings

True borrowings should be distinguished from words made up of morphemes borrowed from Latin and Greek:

E.g. telephone< tele (‘far off) and phone (‘sound’).

The peculiar character of the words of this type lies in the fact that they are produced by a word-building process operative in the English language, while the material used for this formation is bor¬rowed from «another language)).

The word phonograph was coined in 1877 by Edison from the Greek morphemes phone (‘sound’)+grapho (‘write*).

Morphemic borrowings are mostly scientific and technical terms and international in character, the latter fact makes it difficult to deter¬mine whether the word was really coined within the vocabulary of English or not.

International Words

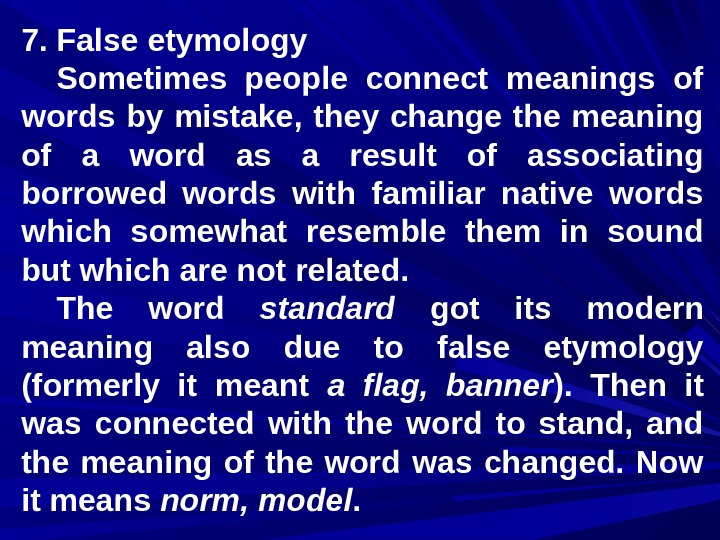

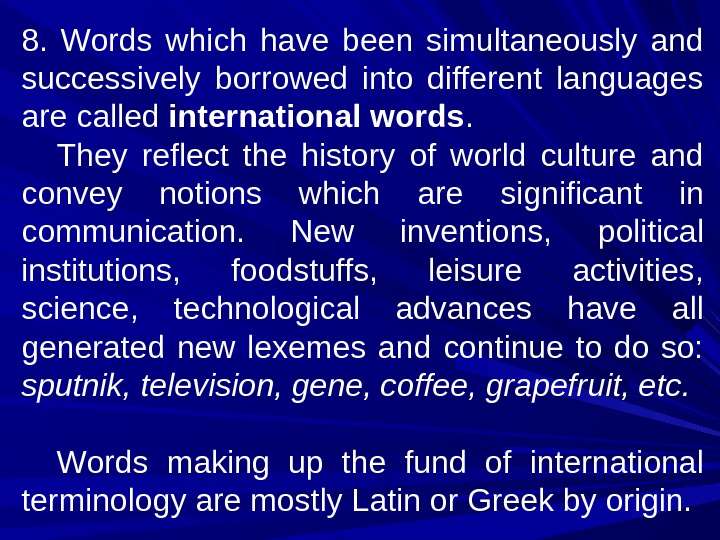

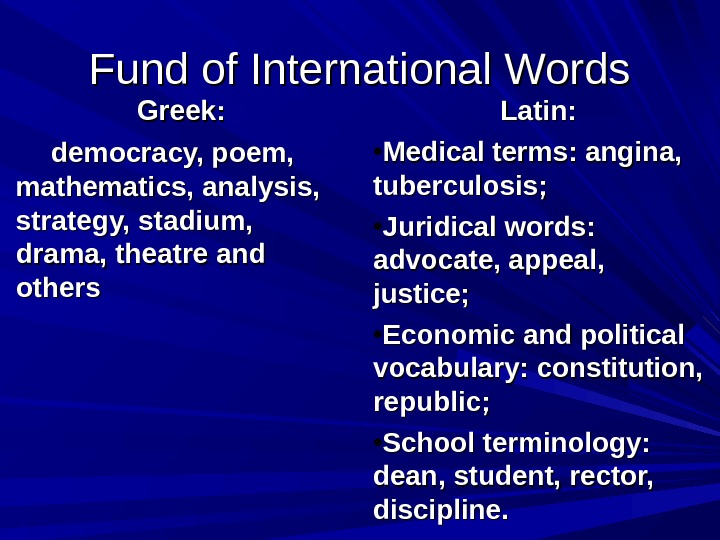

Borrowings or loans are seldom limited to one language. «Words of identical origin that occur in several languages as a result of simulta¬neous or successive borrowings from one ultimate source are called INTERNATIONAL WORDS». (I. V. Arnold).

Such words usually convey notions which are significant in the field of communication. Most of them are of Latin and Greek origin.

Most scientists have international names; e.g. physics, chemistry, biol-ogy, linguistics, etc.

Modern means of communication expand global contacts which result in the considerable growth of international vocabulary.

International words play a very prominent part in various spheres of terminology, such as vocabulary of science, art, industry, etc. The great number of Italian words, connected with architecture, painting and music were borrowed into all the European languages and became international: arioso, baritone, allegro, concert, opera, etc.

Examples of new or comparatively new words due to the progress of science illustrate the importance of international vocabulary: bion¬ics, genetic code, site, database, etc.

The international word-stock has also grown due to the influx of exotic borrowed words like bungalow, pundit, sari, kraal, etc.

The English language has also contributed a considerable number of international words to all the world languages. Among them the sports terms: football, hockey, rugby, tennis, golf, etc.

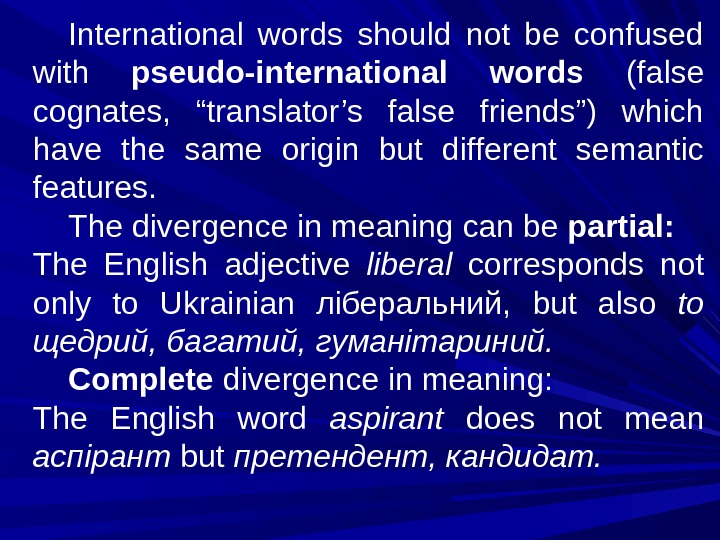

International words should not be mixed with words of the com¬mon Indo-European stock that also comprise a sort of common fund of the European languages. Thus, one should not make a false conclusion that the English ‘son’, the German ‘Sohn’ and the Russian ‘сын’ are international words due to their outward similarity. They represent the Indo-European element in each of the three languages and they are COGNATES, i.e. words of the same etymological root and not borrowings.

Practical

Etymological Survey of the Modern English Language

Exercise 1.

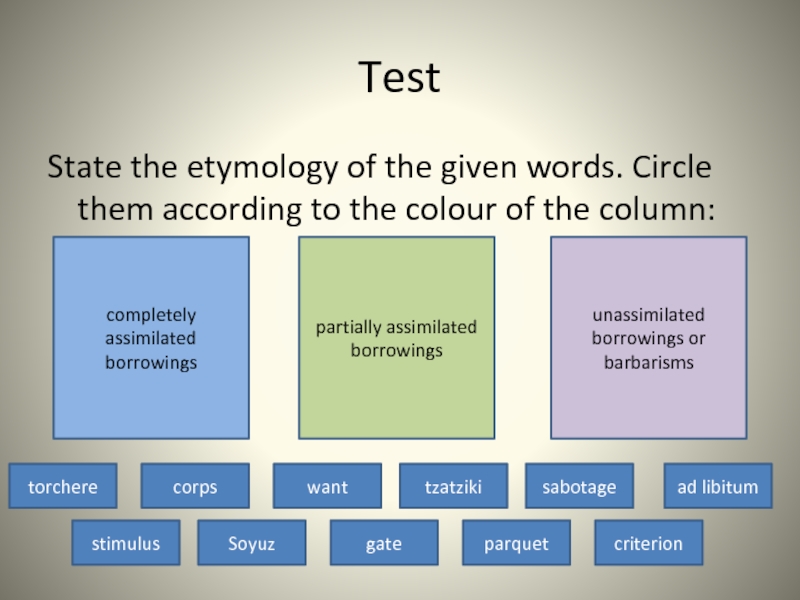

State the etymology of the given words. Write them out in three columns: a) completely assimilated borrowings; b) partially assimilated borrowings; c) unassimilated borrowings or barbarisms.

Torchère, wall, maharani, á la mode, datum, perestroika, gate, têtê-á- têtê, want, chalet, ad hoc, sheikh, parlando, nuclkeus, parquet, matter, bagel, á la carte, kettle, chauffeur, formula, pari-mutuel, shaman, finish, corps, alcazar, commedia dell’arte, money, souvenir, bacillus, pas de deux, ill, spahi, stratum, nota bene, spaghetti, ménage á trios, odd, memoir, parenthesis, hibakusha, padrona, incognito, thesis, coup de maitre, tzatziki, sabotage, ad libitum, stimulus, Soyuz, alameda, street, boulevard, criterion, déjà vu, torero, yin, Übermensch, macaroni, tzigane, sensu lato, hypothesis, bagh, pousada, shiatsu, shapka.

Exercise 2.

Write out international words from the given sentences:

1. He gave a false address to the police. 2. I’ve seen so many good films lately. 3. Do you take sugar in your coffee? 4. Do you play tennis? 5. Arrange the words in alphabetical order. 6. Charlotte Bronte wrote under the pseudonym of Currer Bell. 7. He worked in radio for nearly 40 years. 8. Many people feel that their interests are not represented by mainstream politics. 9. We’ve visited the open-air theatre in London’s Regents Park. 10. I’m worried about my son’s lack of progress in English. 11. The government has promised to introduce reforms of the tax system. 12. He went on to study medicine at Edinburgh University.

Exercise 3.

Give the “false cognates” (false friends) in the Russian language to the given English words. State the difference in their meanings.

Model: argument

The false cognate of the word argument is Russian аргумент. The word argument means “an angry disagreement between people”, whereas the word аргумент has the meaning “reasoning”.

Baton, order, to reclaim, delicate, intelligent, artist, sympathetic, fabric, capital, to pretend, romance.

Video

Melvyn Bragg travels through England and abroad to tell the story of the English language.

-

The double heritage of the

contemporary English language. -

Words of native origin.

-

Borrowing: causes, ways,

criteria. -

Assimilation of borrowings.

-

Translation loans,

etymological doublets, international words.

12.1.

Etymology

is both the study of the history of words and a statement of the

origin and history of a word. Etymologically, all English words are

divided into native

words

and borrowings.

A native

word

is one which hasn’t been borrowed from another language, but

represents the original English wordstock as known from the earliest

available manuscripts of the OE period (5

th

-7

th

c.).

A

borrowed word,

also called a

borrowing

or a

loan-word,

is one which has come into English from another language.

The term «borrowing»

is also used to denote the process of adopting words from other

languages.

English has a great number of

borrowed words (about 70%), which is explained by the eventful

history of the country and numerous international contacts.

12.2. The

original English word stock contains:

-

the Indo-European element,

-

the Germanic element,

-

the Anglo-Saxon (or the

English proper) element.

Only the lattter element can

be dated: the words of this group appeared in the vocabulary in the

5th c. or later when the Angles, Saxons and Jutes invaded Britain.

The

ultimate origins of English lie in IE (possibly spoken between c.

3000 and c. 2000 BC). The

Indo-Buropean element

consists of words common to all or most IE languages. The roots

denote elementary notions without which no communication could be

possible:

-

terms of

kinship: father,

mother, brother, son, daughter, etc.; -

parts of

the human body: nose,

lip, heart, foot, etc.; -

animals:

cow,

swine, goose, fish; -

plants:

tree,

birch, corn; -

times of

day: day,

night; -

heavenly

bodies: sun,

moon, star; -

adjectives:

red,

new, glad, sad; -

numerals:

from one

to

one hundred; -

pronouns:

all personal pronouns except

they which

is a Scandinavian borrowing; demonstrative pronouns; -

verbs: be,

stand, sit, eat, know.

IE ceased

to exist sometime soon after 2000 BC, having diversified into a

number of increasingly distinct offspring as a result of migration

and natural linguistic changes. One of these offspring is known as

Primitive (Old) Germanic. It had a vocabulary that included some

roots not inherited from IE. Thus, the

Germanic element

of English comprises words with roots common to all or most Germanic

languages, but not found in other IE languages:

-

parts of

the human body: head,

arm, hand, finger, bone; -

animals:

bear,

fox, calf; -

plants:

grass,

oak, fir; -

seasons of

the year: spring,

summer, winter (but

autumn

was borrowed from French); -

natural

phenomena:

rain, frost; but

snow is

IE; -

landscape

features: sea,

land; -

human

dwellings, furniture:

house, room, bench; -

sea-going

vessels:

boat, ship; -

adjectives:

green,

blue, grey, white, small, thick, high, old; -

verbs:

see,

hear, speak, tell, say, answer, make, give, drink.

The

English proper element

contains words which have no cognates in any other language,

e.g. bird,

girl, boy, lord, lady, woman, always.

The OE vocabulary expanded

mostly through compounding and derivation,

e.g. da3es

— ēā3e

> daisy;

hāl «hale,

whole»

> hælђ «health».

Though native words are fewer

in number, they play a very important role in English due to their

characteristics:

-

They

possess great stability,

i.e. they have existed for centuries and are sure to exist for

centuries to come. -

They

belong

to very important semantic fields

without which no communication would be possible as they denote

everyday notions and objects. -

They are

monosyllabic, as a rule, and structurally simple, which makes them

flexible,

i.e. they serve as bases for numerous derivatives. -

They are

polysemantic. -

They

possess a wide range of lexical

and grammatical valency,

i.e. they enter into innumerable collocations. -

They are

used

in a great number of phraseological units. -

They have

a

high frequency value in speech.

Thus, native words are an

indespensible part of the English vocabulary.

12.3. In

the ’80s, English borrowed words from 84 languages, as follows:

French – 25%, Spanish and Japanese both – 8%, Italian – 6.3%,

Latin – 6.1%, Greek – 6%, German – 5.5%. Here only the Japanese

element breaks the traditional pattern, in which European languages

predominate.

The

structure of the borrowed element

of the English vocabulary can be shown in the following table.

|

SOURCE |

TIME |

EXAMPLES |

|

Celtic |

5th |

about a |

|

Latin |

1st |

cheese, |

|

2nd |

priest, |

|

|

3rd |

major, |

|

|

Old |

8th |

call, |

|

French |

1st |

sovereign, |

|

2nd |

regime, |

|

|

Greek |

the Renaissance period and |

cycle, |

|

Italian |

the Renaissance period and |

aria, |

|

others: |

17th |

tea, |

Borrowing

can have both linguistic

and extralinguistic

causes.

Extralinguistic

causes

are close contacts between different language communities, which may

be of two kinds: on the one hand, wars, invasions, conquests when a

foreign language is forced upon a reluctant conquered nation; on the

other hand, trade and cultural links, which are more favourable for

borrowing.

Linguistic

causes

are the necessity to fill in gaps in the vocabulary to name new

objects and concepts.

Actually, reasons for

borrowing may be:

-

the domination of some

languages by others (for cultural, economic, religious, political or

other reasons), -

a sense of need, e.g. for

education or technology, -

prestige associated with

using foreign words, -

a mix of some or all of

these. Individuals may use a foreign expression because it seems to

them the most suitable term available, the only possible term (with

no equivalent in their own language) or the most expressive term.

Loan-words

may enter a language in two ways:

-

through oral speech by

immediate contact between people, -

through written speech (e.g.

books, periodicals) by indirect contact.

Oral

borrowing

was more important in earlier periods whereas in more recent times

written borrowing has gained importance.Oral borrowings are usually

short and completely assimilated,

e.g.

street,

mill, inch, pound (all

from Latin).

Written

borrowings

often preserve their spelling and some peculiarities of

pronunciation; their assimilation takes more time,

e.g.

naiveté,

resumé (from

French).

It is

important to distinguish two terms: the

source of borrowing

and the

origin of borrowing.

The former is applied to the language from which the word was

borrowed; the latter means the language the word originates from,

e.g.

jacket,

jumper, crimson, amber, magazine, zero, coffee

were borrowed from French

(source of borrowing) but were originally Arabic.

There are

certain criteria

which can be used to identify a word as a borrowing (and maybe even

determine the source language):

1) spelling and pronunciation,

i.e. «alien» sounds and sound clusters, position of stress,

unusual correlations between sounds and letters,

e.g. [v],

[d3],

[3]

in the initial position:

volcano

(It), vase

(Fr),

genre

(Fr);

j, x, z

in

the initial position:

jungle(Hindi)

, zeal (L);

x is

read

[z]

in

Greek borrowings:

xylophone;

ch is

read

[∫]

in

late French borrowings

(machine) and

[k]

in words of Greek borrowing :

epoch, chemist;

ph, kh,

eau in

the root:

Philology (Gr),

Khaki (Hindi).

-

irregular

plurals: stimulus

— stimuli, criterion — criteria, datum — data, crisis — crises, etc. -

morphological

structure, i.e. some words may be recognized as Latin or French

borrowings by suffixes and prefixes,

e.g. -ant/

-ent: convenient, constant, -ute: attribute, contribute,

-able: detestable, -ive:

convulsive.

Note:

sometimes foreign affixes can be added to native stems: talkative,

drinkable.

4) «alien» concepts

and object of different cultures (realia) denoted by words,

e.g. burqa

«muslim

woman’s long enveloping garment worn in public»,

paella, pagoda, balalaika.

The above mentioned criteria

are not always helpful. Some early borrowings have been so thoroughly

assimilated that they are unrecognisable as such without etymological

analysis.

12.4.

Assimilation of borrowings

(adaptation) means that a borrowing adapts itself more or less

thoroughly to the norms of the borrowing language.

There are

different types

of assimilation:

graphic,

phonetic, grammatic, structural, semantic.

(1) Phonetic

assimilation

is substituting native sounds for foreign ones, as well as a shift of

stress,

e.g. café

(Fr)

[e]

> [ei];

spitz

(German)

[∫]

> [s].

In French and Latin borrowings

the stress is usually shifted to the first syllable,

e.g. garage

[gæ’ra:3]

> [‘gæra:3]

-

Grammatic

assimilation

is the change of grammatical categories and paradigms of borrowed

words,

e.g. cactus

— Pl. cacti and cactuses; trauma — Pl. traumata and traumas.

-

Compounds

and dirivatives are borrowed as simple words.

But if a number of loan-words have the same structure it becomes

clear, morphemes are singled out and in the course of time they may

be even used to derive new words from native stems,

e.g.

eatable,

drinkable, talkative.

Derivatives may also be made

from borrowed stems with the help of native affixes,

e.g.

faintly,

faintness < faint (Fr),

beautiful < beauty (Fr).

Perhaps the

largest morphological impact on English has been the addition of

French, Latin and Greek affixes such as dis-,

pro-, anti-, -ity, -ism

and such combining forms as bio-,

micro-,-metry, -logy,

which replaced many of the original Gc affixes in English.

(4) Semantic

assimilation

consists in changes in the semantic structure of loans.

Polysemantic words are usually

borrowed in one meaning,

e.g. kulak

(Rus)

«well-to-do Russian peasant«.

The original meaning may

change, i.e. it may become more specialized or generalized,

e.g.

umbrella

was

borrowed from Italian in the meaning «a sunshade, parasol»,

then it came to denote similar protection from rain as well.

A borrowing can acquire new

meanings, not found in the original semantic structure,

e.g. move

was

borrowed from French and later acquired the meanings «to

propose», «to change one’s flat», «to mix with

people».

The original primary meaning

of a loan may become a minor one,

e.g. fellow

was borrowed from Old Norse in the meaning «companion» ,

which later became its minor meaning as a new meaning of the word

appeared in English, i.e. «man, boy».

According

to the

degree of assimilation,

borrowings are completely

assimilated,

partially

assimilated

and unassimilated

(called

barbarisms).

Completely

assimilated loan-words

comply with all the norms of the language, their foreign origin is

entirely obscured; they are usually old borrowings, characterized by

high frequency of usage and stylistically neutral,

e.g. cheek,

wrong, cockroach.

Partially

assimilated loan-words

may not be assimilated phonetically (regime,

foyer [‘foiei]);

graphically (corps

[ko:];

buffet [ei]);

morphologically, i.e. they preserve foreign plurals (corpus

— corpora);

semantically, i.e. denote «alien» notions and objects

(jihad

«religious

war of Muslims against unbelievers»,

mullah, sarong).

Unassimilated

loans

are foreign words used by English people, but not adapted in any way

and for which there are English equivalents ,

e.g. carte

blanche (Fr)

— a free hand,

Status quo (L)

— unchanged position.

12.5.

Translation

loans

are words and expressions formed from morphemes available in English

after patterns characteristic of the source language by way of

literal morpheme-for-morpheme translation,

e.g.

Übermensch

(Ger)

— superman (translated

by B. Shaw),

prima balerina (It)

— first dancer.

Semantic

borrowing

is the appearance of a new meaning in an English word’s semantic

structure under the influence of the correlated word in the source

language,

e.g.

reaction

acquired

the political meaning «tendency to oppose change or return to

former system» under the influence of the French word.

Etymological

doublets

are two (or sometimes more) words derived by different routes from

the same source. They differ to a certain degree in form, meaning and

usage. Etymological doublets may be:

-

two native words which were

originally dialectal variants of the same OE word,

e.g. hale

f.

hāl (Northern dialect)

and

whole f.

hōl

(Southern

and Eastern dialects), both originally f. OE hāl;

2) a native and a borrowed

word,

e.g. shirt

(native)

and skirt

(Scandinavian), both originally f. Gc *skurt «short»;

3) two

borrowings from different languages which are etymologically

descendant from the same root,

e.g. canal

(L)

— channel (Fr)

,

etymologically f. L canalis;

4) words borrowed from the

same language twice but at different time,

e.g. corpse

— corps (originally

f. L corpus «body»), both borrowed from French, but corpse

was borrowed from Norman French after the Norman conquest, while

corps was borrowed during the Renaissance period.

Etymological

triplets

are rare,

e.g.

hospital

(L)

— hostel (Norman

Fr)

— hotel (Fr

during the Renaissance).

International

words

are words of the same origin that exist in several languages as a

result of simultaneous or successsive borrowing from one ultimate

souce. Usually they are words of Latin or Greek origin. Here belong:

-

scientific

terms, e.g. philosophy,

mathematics, medicine, antenna; -

terms of

art, e.g. music,

tragedy, comedy, theatre, museum; -

political

terms, e.g. policy,

democracy, anarchy, progress; -

foodstuffs,

e.g. banana,

chocolate, coffee, cocoa.

English has also contributed

quite a few international words to world languages, e.g.

-

sport

terms: football,

tennis, box, match, knock-down; -

clothes:

sweater, pullover,

tweed, jersey, nylon; -

entertainment:

film,

club, jazz, cocktail, etc.

International words in

different languages, despite their outward similarity, often have

different meanings. They are called «false friends of

interpreters» as interpreters and translators, as well as

language learners should be aware of them,

e.g.

sympathy

«compassion» – симпатия

«liking»,

complexion

«face colour» — комплекция

«build»,

decade

«ten years» — декада

«ten days».

Слайд 1

Etymological Characteristics of the Modern English Lexicon

©Malysheva, 2012

Lecture 5, 6

the 4th

term

Слайд 2PLAN

1 The basic stock of the English vocabulary and its peculiarities

2

Reasons and ways of borrowings

3 Types of borrowings

4 Assimilation of borrowings

5 Types of assimilated words

Слайд 31 The Basic Stock of the English Vocabulary and its Peculiarities

What

is vocabulary?

The vocabulary of any language doesn’t remain the same but changes constantly.

The vocabulary is an open system and the number of words cannot be stated with certainty.

The term Etymology (from Greek) means the study of the earliest forms of the word.

Plan

Слайд 4“English is characterized by the mixed character of its vocabulary “

[Joseph M. Williams “Origins of the English Language”]

Слайд 5

http://public.oed.com/media/twominuteoed/public.html

Explore 1,000 years of English in two minutes

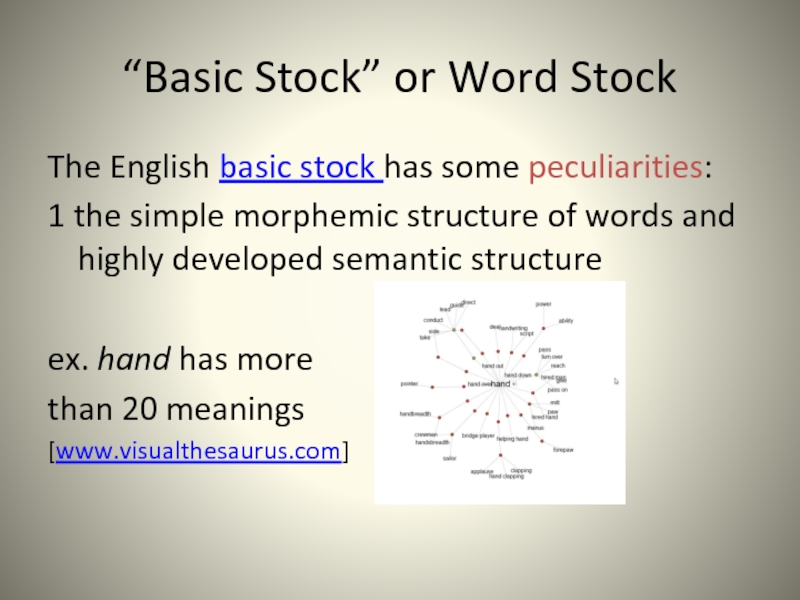

Слайд 6“Basic Stock” or Word Stock

The English basic stock has some peculiarities:

1

the simple morphemic structure of words and highly developed semantic structure

ex. hand has more

than 20 meanings

[www.visualthesaurus.com]

Слайд 7

2 its etymology

Ex. hand (n.) [www.etymonline.com]

O.E. hond, hand «hand; side; power,

control, possession,» from P.Gmc. *khanduz (cf. O.S., O.Fris., Du., Ger. hand, O.N. hönd, Goth. handus).

![Etymological Characteristics of the Modern English Lexicon 2 its etymology Ex. hand (n.) [www.etymonline.com] O.E. hond, hand 2 its etymology Ex. hand (n.) [www.etymonline.com] O.E. hond, hand](https://thepresentation.ru/img/tmb/2/146522/a0ca6566ec8bb5701b24a1701dd3640e-800x.jpg)

Слайд 8Etymologically the basic stock of the English vocabulary falls into 3

layers

a) words of the general Indo-European origin

b) words of the common Germanic origin

c) words of unknown origin

Слайд 9Indo-European Words

names of kingship;

names of phenomena of nature;

names of animals

and birds (cat – Katz – кот);

parts of human body (nose – нос – nasus – Nase);

names of the most frequent actions (stand – stande – стоять);

adjectives naming concrete properties (red – rod – rufus – рудый);

most of the numerals (two – duo – два);

some pronouns (I – ich – ego)

Слайд 10

The first are the oldest words in the English vocabulary. They

have cognates in vocabularies of different groups of Indo-European languages.

Ex. dēor: «animal, beast.» (OE),

Cf. Tier (G), dier (Dutch), djur (Swedish),

dyr (Norwegian and Danish)

Слайд 11Common Germanic Words

They form the bulk of the most frequent elements

used in any style of speech. Their most characteristic features are: a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency, high frequency value and a developed polysemy; they are often monosyllabic, show great word-building power and enter a number of set expressions.

parts of the human body (head, hand, arm, finger, bone);

animals (bear, fox, calf);

plants (oak, fir, grass);

natural phenomena (rain, frost);

seasons of the year (winter, spring, summer);

landscape features (sea, land).

Слайд 12Unknown Origin

buy – byegan only Germanic origin, not found outside Germanic

lgs;

girl — gyrle «child» (of either sex);

lady — from O.E. hlæfdige «mistress of a household, wife of a lord,» lit. «one who kneads bread,» from hlaf «bread» (see loaf) + -dige «maid»;

horse — O.E. hors

Слайд 132 Reasons and Ways of Borrowings

Borrowing is

resorting to the word-stock of

other languages for words to express new concepts, to further differentiate the existing concepts and to name new objects, etc. (process);

a loan word, borrowed word – a word taken over from another language and modified in phonemic shape, spelling, paradigm or meaning according to the standards of the English language (result) .

Plan

Слайд 14There are different reasons for borrowing words: linguistic and extralinguistic

Auto-machine

gun Maxim was named after its creator sir Hiram Stevens Maxim

(1840—1916)

Extralinguistic (historic) reasons include wars and conquest and peaceful contacts as well.

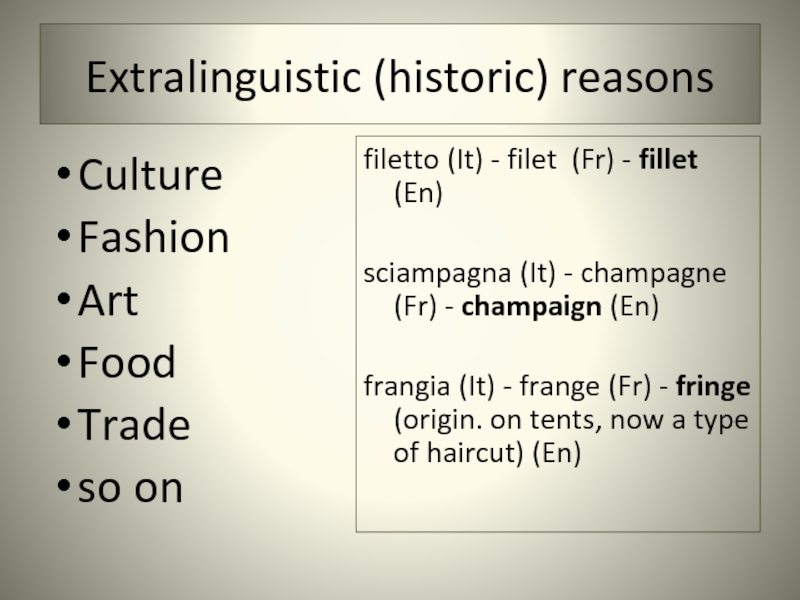

Слайд 15Extralinguistic (historic) reasons

Culture

Fashion

Art

Food

Trade

so on

filetto (It) — filet (Fr) — fillet (En)

sciampagna

(It) — champagne (Fr) — champaign (En)

frangia (It) — frange (Fr) — fringe (origin. on tents, now a type of haircut) (En)

Слайд 16Linguistic reasons

a gap in vocabulary — the words were borrowed

together with the notions which they denoted.

EG: potato, tomato were borrowed from Spanish, when these vegetables were brought to the British island.

Balaclava — «woolen head covering,» especially worn by soldiers

Evidently named for village near Sebastopol, Russia, site of a battle Oct. 25, 1854, in the Crimean War. But the term (originally Balaclava helmet) does not appear before 1881 and seems to have come into widespread use in the Boer War. The British troops seem to have suffered from the cold in the Crimean War, and the usage might be a remembrance of that conflict.

Слайд 17

2) a different point of view on the same object. This

type of borrowing enlarges groups of synonyms.

Ex: to adore

to love

to like

The French word “to adore” was added to native words “to like” and “to love” to denote the strongest degree of the process.

Слайд 18Ways of Borrowing

Borrowings enter the language in two ways:

through oral

speech

(by immediate contact between the peoples)

through written speech

(by indirect contact through books, etc.)

Слайд 19

Oral borrowing took place chiefly in the early periods of history

Words borrowed orally are usually short, are assimilated more readily, they undergo considerable changes in the act of adoption.

e.g. L. inch, mill, street

Слайд 20

Written borrowing happened in recent times.

Such words preserve their spelling

and some peculiarities of their sound-form, their assimilation is a long and laborious process.

e.g. Fr. communiqué, belles-lettres, naïveté (naivety (En)

Слайд 21

Linguistic borrowings are a dilemma: are they necessary to the development

of a language or do they undermine its purity? Borrowings are, of course, necessary. Probably an English language wouldn’t exist without the almost 70,000 borrowed terms from French.

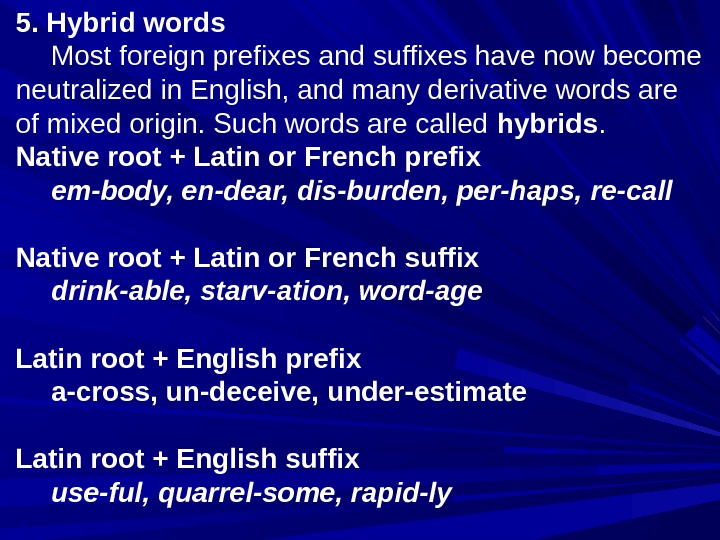

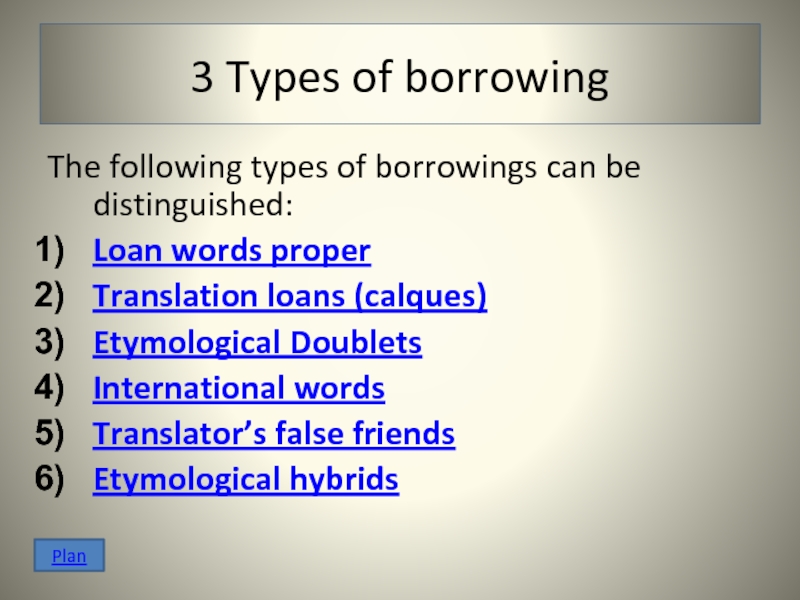

Слайд 223 Types of borrowing

The following types of borrowings can be distinguished:

Loan

words proper

Translation loans (calques)

Etymological Doublets

International words

Translator’s false friends

Etymological hybrids

Plan

Слайд 23Loan words proper

words borrowed from another language and assimilated to this

or that extent.

Ex. Table, skirt, mill

Слайд 24Translation loans (calques)

words and expressions formed from the material already existing

in the English language but according to patterns taken from another language by way of literal word-for-word or morpheme-for-morpheme translation

EG: from the Russian language: пятилетка – five-year plan,

from German: Wunderkind – wonder child,

from Italian: prima ballerina – first dancer.

Слайд 25Etymological Doublets

are words which have the same origin but they are

different in phonetic shape and in meaning.

Слайд 26Doublets appeared in English in different ways

1) One of the pair

may be a native word and the other is a borrowed one. EG: the word shirt is native. skirt was borrowed from Scandinavian (clothes)

2) Both words are borrowed, but from different languages. EG: senior (from Latin) sir (from French)

3) Both words are borrowed from one of the same language, but at different periods of time. EG: cavalry (Normandy French) – кавалерия. Chivalry (Parisian Language) – рыцарство (ch-показывает о более позднем происхождение). humour and humid.

4) Shortening may bring to life etymological doublets. EG: history and story, defense and fence.

3

Слайд 27Etymological hybrids

are derivational words that are formed by means of

derivational morphemes of different origin.

Thus almost immediately after the borrowing of the word sputnik the words pre-sputnik, sputnikist, sputnikked, to out-sputnik.

London – (L.) Londinium (c.115), often explained as «place belonging to a man named Londinos,» a supposed Celtic personal name meaning «the wild one“

Beautiful

Слайд 28International words

are the words, borrowed by several languages denoting the

same notion. Among international words are names of sciences, political terms, sports, name of fruits, foods.

Ex. phonetics, physics, dynamite, kangaroo, sauna, fauna

http://www.answers.com/library/International+Word+Origins

Слайд 29Translator’s false friends

are the words from different languages which are

similar in their form but different in their meaning or the meanings of the two do not completely coincide

Слайд 30

1) English-Russian and Russian-English dictionary of “the false friends of a

translator” by Aculenco V.V.

2) German-Russian and Russian-German dictionary of “the false friends of a translator” by Gotlib K.G.

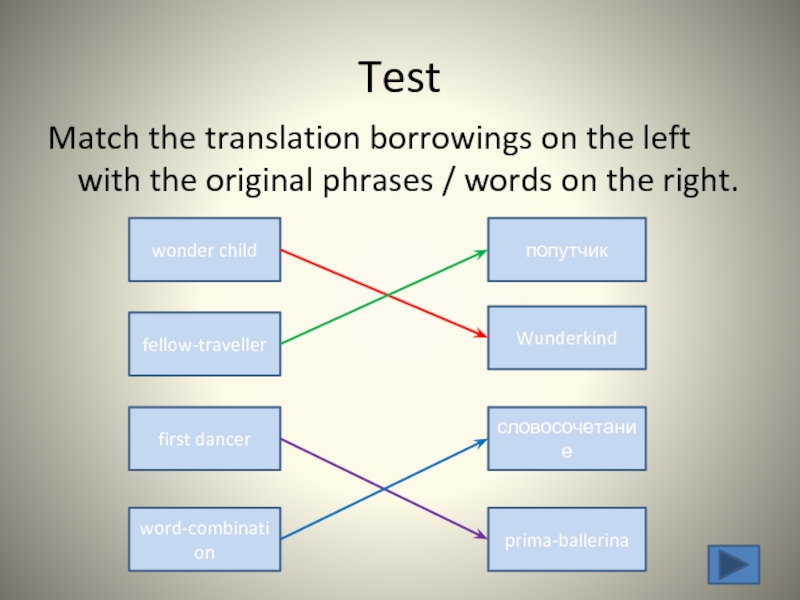

Слайд 31Test

Match the translation borrowings on the left with the original phrases

/ words on the right.

попутчик

fellow-traveller

wonder child

Wunderkind

first dancer

словосочетание

word-combination

prima-ballerina

Слайд 324 Assimilation of Borrowed Words

Assimilation is the result or adaptation of

borrowed words.

The phenomenon by which two languages are put in contact and borrow words one from the other is known as interference.

A lexical borrowing occurs when a group of speakers is put in contact with a foreign word and adopts it in their language. Usually, there are substantial changes in its morphology, in the pronunciation and even in the meaning.

Plan

Слайд 33Borrowed words get assimilated in 3 main fields: phonetic, grammatical and

semantic.

Phonetic assimilation comprises changes in sound-form and stress. It is most obvious.

Sounds that were unfamiliar to the English language were fitted into its scheme of sounds.

Ex. 1) the long [e] and [ε] are rendered with the help of [ei] (as in café).

2) In words from French or Latin the accent was gradually transferred to the first syllable (honour, reason)

Слайд 34

3) the consonant combinations [pn], [ps], [pt] in the words pneumatics,

psychology, Ptolemy were simplified into [n], [s], [t], since the consonant combinations [ps], [pt], [pn], were never used in the initial position.

4) For the same reason the initial [ks] was changed into [z] (as in Gr. xylophone).

![Etymological Characteristics of the Modern English Lexicon 3) the consonant combinations [pn], [ps], [pt] in the words pneumatics, 3) the consonant combinations [pn], [ps], [pt] in the words pneumatics, psychology, Ptolemy were simplified into](https://thepresentation.ru/img/tmb/2/146522/c6c61d65ea72a8905a88bb51bf2c55b7-800x.jpg)

Слайд 35Grammatical assimilation

consists in a complete change of the paradigm of

the borrowed word.

EG: delicious – more delicious – the most delicious, cup-cups.

Some of the borrowed words are still in the process of grammatical assimilation.

EG: formula (-as – colloq),(-ae – scient.) plural

Слайд 36semantic assimilation

The adjustment of the word to the system of

meanings of the English vocabulary.

EG: the word “large” was borrowed from French in the meaning “broad”. But in the Eng. vocabulary there already was an adjective with the same meaning (“wide”). The word “large” entered a group of words meaning “big” in size. At first the word “large” was used when speaking about objects which were horizontally “large”. But then it changed its meaning and now it can be used when speaking about any object and it is close in meaning to the adjective “big”.

Слайд 37Some Rules of Adoptation

1) Polysemantic words are usually adopted only in

one or two of their meanings.

The words cargo and cask, highly polysemantic in Spanish, were adopted only in one of their meanings — ‘the goods carried in a ship’, ‘a barrel for holding liquids’ respectively.

2) The semantic structure of borrowings changes in other ways as well. Some meanings become more general, others more specialised, etc.

Ex. the verb move in Modern English has developed the meanings of ‘propose’, ‘change one’s flat’, ‘mix with people’ and others that the French mouvoir does not possess.

Слайд 385 Types of Assimilated Words

Fully assimilated (street, mill, minister, cup)

Partially assimilated

(phenomenon – phenomena, garage)

3. Non-assimilated (barbarisms) – belles-lettres, touché

Plan

Слайд 39unassimilated borrowings or barbarisms

Test

State the etymology of the given words. Circle

them according to the colour of the column:

completely assimilated borrowings

partially assimilated borrowings

Soyuz

gate

want

tzatziki

sabotage

ad libitum

torchere

corps

stimulus

criterion

parquet

Слайд 40Summary

1) A pure language actually is a utopia; every language (unless

it is a dead language, like Latin) can’t avoid interference with other countries and other cultures. Language is an open system and every language is a member of a global linguistic community.

2) Anyway, the prime mover in linguistic borrowings is the individual speaker who, after being put in contact with a written or a spoken foreign word, forms an acoustic image in his mind, which , after a so called processing period, becomes a borrowed term.

3) During the processing period, the speaker adapts the foreign word to the morphology and the phonetics of its own language, trying to transform all the morphological or /and phonetic features which don’t exist in the language he speaks.

Plan

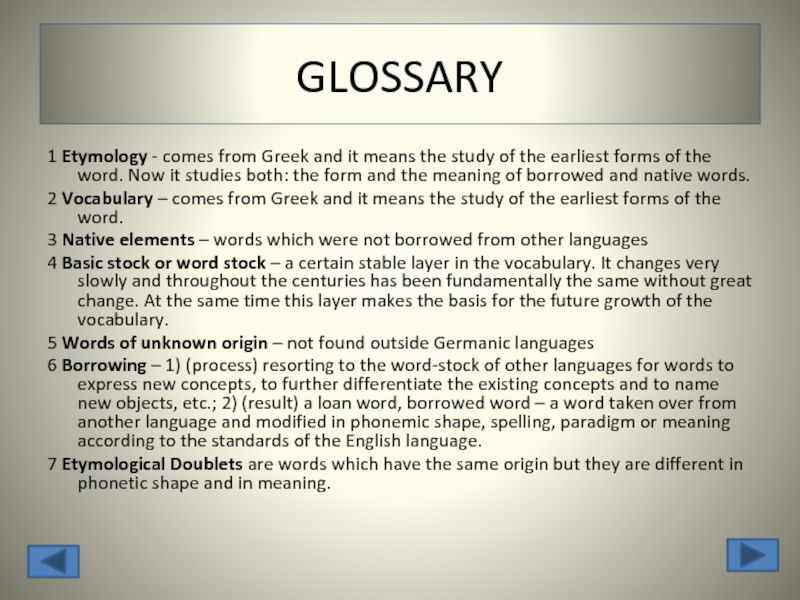

Слайд 41GLOSSARY

1 Etymology — comes from Greek and it means the study

of the earliest forms of the word. Now it studies both: the form and the meaning of borrowed and native words.

2 Vocabulary – comes from Greek and it means the study of the earliest forms of the word.

3 Native elements – words which were not borrowed from other languages

4 Basic stock or word stock – a certain stable layer in the vocabulary. It changes very slowly and throughout the centuries has been fundamentally the same without great change. At the same time this layer makes the basis for the future growth of the vocabulary.

5 Words of unknown origin – not found outside Germanic languages

6 Borrowing – 1) (process) resorting to the word-stock of other languages for words to express new concepts, to further differentiate the existing concepts and to name new objects, etc.; 2) (result) a loan word, borrowed word – a word taken over from another language and modified in phonemic shape, spelling, paradigm or meaning according to the standards of the English language.

7 Etymological Doublets are words which have the same origin but they are different in phonetic shape and in meaning.

Слайд 42Literature

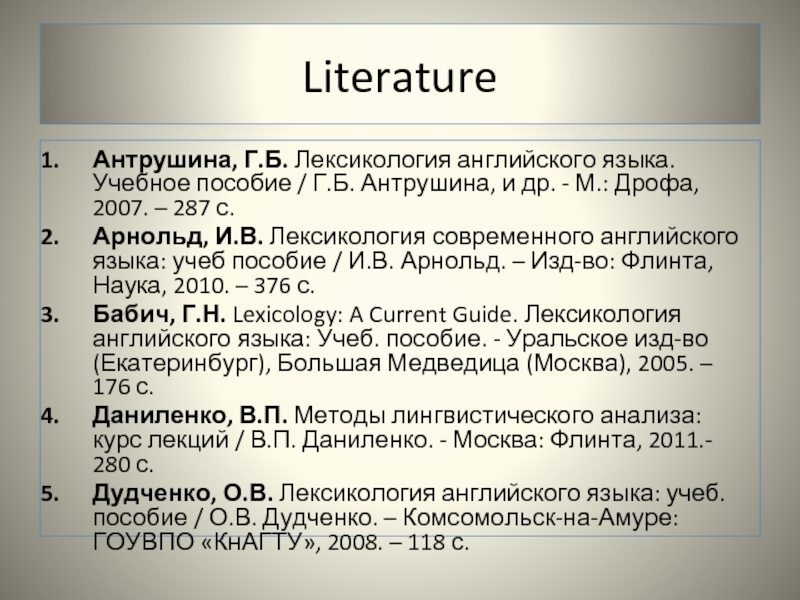

Антрушина, Г.Б. Лексикология английского языка. Учебное пособие / Г.Б. Антрушина, и

др. — М.: Дрофа, 2007. – 287 с.

Арнольд, И.В. Лексикология современного английского языка: учеб пособие / И.В. Арнольд. – Изд-во: Флинта, Наука, 2010. – 376 с.

Бабич, Г.Н. Lexicology: A Current Guide. Лексикология английского языка: Учеб. пособие. — Уральское изд-во (Екатеринбург), Большая Медведица (Москва), 2005. – 176 с.

Даниленко, В.П. Методы лингвистического анализа: курс лекций / В.П. Даниленко. — Москва: Флинта, 2011.- 280 с.

Дудченко, О.В. Лексикология английского языка: учеб. пособие / О.В. Дудченко. – Комсомольск-на-Амуре: ГОУВПО «КнАГТУ», 2008. – 118 с.

- Размер: 228.5 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 40