Borrowed

words constituted only a small portion of the

OE vocabulary – all in all about six hundred words.

The borrowings reflect

the contacts of English with other tongues resulting from diverse

political,

economic, social and cultural events in the early periods of British

history. OE borrowings come from two sources: Celtic and Latin.

1.2.1. Borrowings from Celtic

There

are very few Celtic loan-words in the OE vocabulary, for

there must have been little intermixture between the Germanic

settlers

and the Celtic in Britain. Abundant

borrowing from Celtic is to be found only in place-names. The OE

kingdoms

Kent,

Deira and

Bernicia

derive

their names from the names of

Celtic tribes. The names of York,

the

Downs

and

perhaps London

have

been

traced to Celtic sources (Celtic dūn

meant

‘hill’).

The name London

may

have originated from the Celtic compound Llyndūп

which

meant ’a fortress on the river bank’.

This

name was known to Tacitus who calls this place Londinium.

Various

Celtic designations

of ‘river’ and ‘water’ were understood by the Germanic invaders

as proper names: Ouse,

Exe, Esk, Usk, Avon, Evan go

back to Celtic

amhuin

‘river’,

uisge

‘water’;

Thames,

Stow, Dover also

come from

Celtic. Some elements frequently occurring in Celtic place-names can

help to identify them: -comb

‘deep

valley’ in Batcombe,

Duncombe, Winchcombe;

-torr ‘high

rock’ in Torr,

Torcross; -llan ‘church’

in Llandaff,

Llanelly; -pill ‘creek’

in Pylle,

Huntspill. Many

place-names with

Celtic elements are hybrids; the Celtic component, combined with a

Latin or a Germanic component, make a compound place-name; e.g.

Celtic

+ Latin Celtic

+ Germanic

Man-chester York-shire

Win-chester Corn-wall

Glou-cester Salis-bury

Wor-cester Lich-field

Devon-port Devon-shire

Lan-caster Canter-bury

Outside

of place-names Celtic borrowings in OE were very few:

no more than a dozen. Examples of common nouns are: OE binn

‘bin’=’crib’,

cradol

‘cradle’,

bratt ‘cloak’,

dun

‘dun’,

‘dark

coloured’,

dūn

‘hill’,

cross

‘cross’,

probably

through Celtic from

the L crux.

A

few words must have entered OE from Celtic due to the

activities of Irish missionaries in spreading Christianity, e.g. OE

ancor

‘hermit’,

cursian

‘curse’.

In

later ages some of

the Celtic borrowings died out or survived only in dialects e.g.

loch

(dial.)

‘lake’, coomb

(dial.)

‘valley’.

1.2.2. Latin influence on the Old English vocabulary

Latin

words entered the English language at different stages

of OE

history. Chronologically they can be divided into two layers.

1)

The

earliest (first) layer

comprises words which the Teutonic tribes brought from

the continent when they came to settle in Britain. Contact with the

Roman civilization began a long time before the Anglo-Saxon invasion.

The

adoption of Latin words continued in Britain after the invasion,

since

Britain had been under Roman occupation for almost 400 years. Though

the Romans left Britain before the settlement of the Teutons,

Latin words could be transmitted to them by the Romanised

Celts.

Early

OE borrowings from Latin indicate the new things and concepts

which the Teutons had learnt from the Romans; as seen from the

examples below they pertain to war, trade, agriculture, building and

home

life.

Below

is the table for these borrowings classified in accordance with the

areas they referred to.

Table

6.3

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

References

1 The following abbreviations are used: CIL = Classical Latin; D = Dutch; Gmc. = Germanic; L = Latin; OFr = Old French; OHG = Old High German; VL = Vulgar Latin; W = Welsh. The number of Latin loan-words in Old English will finally be ascertained only with completion of the Toronto-based Dictionary of Old English [ = DOE] on the basis of A Microfiche Concordance to Old English, compiled by Healey, A. di Paolo and Venezky, R. L. (Toronto, 1980)Google Scholar and of the Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altenglischen by Professor Alfred Bammesberger at Eichstätt; see also Gneuss, H., ‘Some Problems and Principles of the Lexicography of Old English’, Festschrift für Karl Schneider, ed. Jankowsky, K. R. and Dick, E. S. (Amsterdam, 1982), pp. 153–66, at 154.CrossRefGoogle Scholar There are quite a few estimates of the quantity of Latin loans in Old English which are mainly based upon the substantial but far from complete lists supplied by Serjeantson, M. S., A History of Foreign Words in English (London, 1935). The list given there in Appendix A (pp. 271–88)Google Scholar comprises approximately 540 loan-words and is arranged by semantic fields assigned to three chronological strata (A, B and C, respectively). According to Scheler, M., Der englische Wortschatz, Grundlagen der Anglistik und Amerikanistik 9 (Berlin, 1977), 38, n. 23Google Scholar, there are some 600 Latin loans in Old English, including some 50 loans adopted during the late Old English period after the Norman Conquest. With respect to the quantity of Latin loans in Old English, Barbara, Strang, A History of English (London, 1970)Google Scholar, depends heavily upon Serjeantson, although she gives no overall number. The number of early Latin loan-words in Germanic is estimated at some 400 (ibid. p. 388). A relatively comprehensive list of loan-words is provided by Skeat, W. W., Principles of English Etymology. First Series, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1892), §§ 398–9.Google Scholar For a preliminary list of early loan-words borrowed before AD 600 arranged on the basis of the sound changes of Latin tonic vowels, see Wollmann, A., Untersuchungen zu den frühen Lehnwörtern im Altenglischen. Phonologie und Datierung, Texte und Untersuchungen zur englischen Philologie 15 (Munich, 1990), 152–80.Google Scholar

2 Jackson, K. H., Language and History in Early Britain. A Chronological Survey of the Brittonic Languages First to Twelfth Century A.D. (Edinburgh, 1953) [hereafter LHEB], p. 76 including n. 3Google Scholar; Haarmann, H., Der lateinische Lehnwortschatz im Kymrischen, Romanistische Versuche und Vorarbeiten 36 (Bonn, 1970), 8–10, estimates the number of Latin loan-words in Welsh at some 700. See also below, n. 31.Google Scholar

3 A comprehensive but far from inclusive list of Latin loan-words in the Germanic languages was provided by Kluge, F., ‘Vorgeschichte der altgermanischen Dialekte. Mit einem Anhang: Geschichte der gotischen Sprache’, Grundriss der germanischen Philologie, ed. Paul, H., 2nd ed. (Strassburg, 1899) I, 333–54 (‘Die lateinischen Lehnworte der altgermanischen Sprachen’).Google Scholar

4 Cf. e.g. Krapp, G. P., Modern English. Its Growth and Present Use (New York, 1910), pp. 212 and 216Google Scholar; Robertson, S., The Development of Modern English (New York, 1934), pp. 44–5.Google Scholar Loan formations have been dealt with in depth by Gneuss, H., Lehnbildungen und Lehnbedeutungen im Altenglischen (Berlin, 1955).Google Scholar

5 Campbell, A., Old English Grammar (Oxford, 1959) [hereafter Cpb], §§ 493 and 545.Google Scholar

7 It is possible that borrowing had set in already around AD 560: ‘With the coming of Augustine and his 40 companions in 597, and possibly even at an earlier date, with the arrival of Bishop Liudhard in the retinue of Queen Bertha of Kent in the 560’s, reading and writing Latin became one of the skills offered by the young Church. How soon the use of the Latin alphabet was extended to the writing of Old English we can infer from the promulgation of Æthelbert of Kent’s written law code early in the seventh century’ (Derolez, R., ‘Runic Literacy among the Anglo-Saxons’, Britain 400–600: Language and History, ed. Bammesberger, A. and Wollmann, A., Anglistische Forschungen 205 (Heidelberg, 1990), 397–436, at 399).Google Scholar

8 For OE antefn, see Wollmann, A., ‘Zur Datierung christlicher Lehnwörter im Altenglischen: ae. antefn’, in Language and Civilization. A Concerted Profusion of Essays and Studies in Honour of Otto Hietzsch, ed. Blank, C. (Frankfurt and Bern, 1992), pp. 124–38Google Scholar; for OE œlmesse, see Pogatscher, A., Zur Lautlehre der griechischen, lateinischen und romanischen Lehnworte im Altenglischen, Quellen und Forschungen zur Sprach- und Culturgeschichte der germanischen Völker 64 (Strassburg, 1888), § 38CrossRefGoogle Scholar; for L episcopus (> OE biscop), see Rotsaert, M.-L., ‘Vieux-Haut-Allem. biscof/Gallo-Roman *(e)bescobo, (e)bescobə/Lat. episcopus’, Sprachwissenschaft 2 (1977), 181–216Google Scholar; for OE mœsse, see Wollmann, A., ‘Lateinisch-Altenglische Lehnbeziehungen im 5. und 6. Jahrhundert’, Britain 400–600: Language and History, ed. Bammesberger, and Wollmann, , pp. 373–96, esp. 392–4.Google Scholar

9 See A. Wollmann, ‘Early Christian Loanwords in Old English’, Germania Latina II (forthcoming).

10 W. W. Skeat, Principles of English Etymology. First Series (see n. 1). Skeat discriminates pre-Christian loan-words (‘Latin of the First Period’ up to AD 600) and Christian loan-words (‘Latin of the Second Period’).

11 Pogatscher, Lautlehre (as cited above, n. 8).

13 Ibid. p. 5: ‘If loan-words were borrowed early they should show signs of great age with respect to the Romance or Germanic phonological form. On the Romance side an infallible criterion is the conservation of intervocalic voiceless stops, on the Germanic side the High German consonant shift. If one of these criteria is attested in a genuinely popular word it is a continental loan-word.’

14 Jud, J., ‘Probleme der altromanischen Wortgeographie’, Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 38 (1917), 1–75.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

15 Pogatscher, , Lautlehre, p.1Google Scholar: ‘Unter diesen Bedingungen sind für den Grammatiker wieder zwei von besonderer Wichtigkeit, nämlich die Art der Vermittlung fremder Sachen und Worte, und falls ein grösseres Gebiet hierbei in Frage kommt, die geographische Lage der Berührungsstellen oder Berührungslinien, an welchen jene Vermittlung sich vollzogen hat. In allen Fällen wird die Beantwortung der Frage nach den Berührungslinien zugleich auch wesentliche Hilfsmittel zur Erkenntnis der Art der Vermittlung bieten, während in vielen Fällen die Art der Vermittlung zwischen verschiedenen Völkern eine ähnliche oder gleiche sein wird; die Feststellung der Berührungslinien wird daher ein erhöhtes Interesse für sich in Anspruch nehmen können.’

17 Ibid. p. 13. It may be noted that Pogatscher sees no significant difference between the Latin of Roman Gaul and the variety of Latin spoken in Britain: ‘… im Allgemeinen mag hier bemerkt werden, dass die grammatische Form der Æ. Lehnworte für das britannische Volkslatein ein so enges Zusammengehen mit dem gallischen erweist,… dass wenn die Angelsachsen nicht nach Britannien gekommen wären, England wohl eine dem Französischen sehr nahestehende Sprach erhalten hätte, natürlich vorausgesetzt, dass die Romanisierung Britanniens ausgedehnt genug gewesen war. Daher bin ich bei dem Ansatz der Substrate auch unbedenklich überall von gallorom. Grundformen ausgegangen.’

18 Luick, K., Historische Grammatik der englischen Sprache I (Leipzig, 1921–1940) [hereafter Lck], p. 63.Google Scholar Luick’s account goes back to J. Hoops.

19 Ibid.Jungandreas, W., Geschichte der deutschen und englischen Sprache. Teil III: Geschichte der englischen Sprache (Göttingen, 1949), p. 312,Google Scholar even sets up a period of a ‘nordwestdeutschen Sprachgemeinschaft zwischen Somme, Weser und Nordsee im 4. Jh.’, which would imply an approximately simultaneous adoption of a certain set of Latin words into Old English, Old Frisian and Old Saxon.

20 Lck, § 208, n.: ‘Eine Feststellung ist jedoch nicht möglich, da bisher an keinem Lehnwort Spuren des Durchgangs durch einen anderen germanischen Dialekt unmittelbar, d.h. in seiner Lautgebung, nachgewiesen werden konnte.’

21 Although AD 450 can no longer be seen as the historical date of the adventus Saxonum, it still is suitable as a useful date for a working model, if we take into account a transitional period of some decades during the first half of the fifth century. For a concise survey of the historical background of the settlement period, see Wollmann, , ‘Lehnbeziehungen im 5. und 6. Jahrhundert’, pp. 377–80Google Scholar and especially Hines, J., ‘Philology, Archaeology and the adventus Saxonum vel Anglorum’, Britain 400–600: Language and History, ed. Bammesberger, and Wollmann, , pp. 17–36.Google Scholar The integration of historical dates into a relative chronology was one of Pogatscher’s aims: ‘Insbesondere habe ich – wenn ich nicht irre – hier zum ersten Male den Versuch gewagt, mit Hilfe der ältesten Lehnworte neben und an Stelle der bisher zumeist relativen einige in sich zusammenhängende Grundlinien einer absoluten Chronologie gewisser Erscheinungen des vorlitterarischen Lautstandes der beiden hier in Frage kommenden Sprachgebiete [i.e. Old English and Gallo-Romance] zu ziehen’ (Lautlehre, p.ix).Google Scholar

22 Pogatscher, , Lautlebre, p.12Google Scholar: ‘Für die Kulturentwicklung der Angelsachsen war diese zweite Periode, welche sich von 450 bis 600 erstreckt, von der grössten Bedeutung. Die beträchtliche Zahl der innerhalb dieser Zeit aufgenommenen Lehnworte zeigt, welche neuen Anschauungen der neue Boden, der von römischer Bildung durchdrungen war, den Ankömmlingen erschlossen hat.’

23 Pogatscher, , Lautlehre, pp. 2–4Google Scholar, citing Wright, T., The Celt, the Roman, and the Saxon, 4th ed. (London, 1885)Google Scholar and Winkelmann, E., Geschichte der Angelsachsen bis zum Tode König Alfreds, Allgemeine Geschichte in Einzeldarstellungen, 2. Hauptabtheilung, 3. Theil (Berlin, 1883).Google Scholar See also Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 9–11 and 15.Google Scholar

24 Ibid. p. 4: ‘The natural consequence appears to be the continued existence of Latin in Britain for a longer period. Hence the source of the Latin and Romance loan-words borrowed after AD 450 is Britain.’ Although Pogatscher’s book was the first relatively comprehensive linguistic study of the Latin loan-words, Pogatscher naturally did have precursors (see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 4–11).Google Scholar Earlier remarks in historical works and shorter studies on Latin loan-words in Old English, however, were frequently marred by the presupposition that the Anglo-Saxons could have adopted originally Latin loan-words only through the mediation of romanized Celts in Britain; cf. Guest, E., ‘On Certain Foreign Terms, adopted by our Ancestors prior to their Settlement in the British Islands’, Proc. of the Philol. Soc. 5 (1852), 169–74 and 185–9.CrossRefGoogle Scholar No date is normally given for the final extinction of British Latin, but it becomes sufficiently clear that Latin was supposed to have been a spoken language at least during the fifth and sixth centuries. Surprisingly, direct borrowing due to contacts with the Romans on the Continent was regarded as a possibility only from the middle of the nineteenth century.

25 ‘British Latin’ is a term used by Jackson, LHEB, p. 5Google Scholar, as representing ‘the variety of Vulgar Latin spoken in Britain during and for some time after the Roman occupation’; in an earlier essay Jackson used the term ‘Vulgar Latin of Roman Britain’: ‘On the Vulgar Latin of Roman Britain’, Medieval Studies in Honor of J. D. M. Ford, ed. Holmes, U. T. and Denomy, A. J. (Cambridge, MA, 1948), pp. 83–103.Google Scholar The sociolinguistic aspect is stressed by Pogatscher’s usage of ‘britannisches Volkslatein’ vs. ‘Schriftlatein’ (Lautlebre, pp.9 and 13Google Scholar) and especially by E. P. Hamp’s ‘British spoken Latin’ (‘Social Gradience in British spoken Latin’, Britannia 6 (1975), 150–62, at 160–1).CrossRefGoogle Scholar Although ‘British Latin’ tends to suggest a uniform language, it seems to be the most satisfactory term available.

26 Shevelov, G. Y., A Prehistory of Slavic: the Historical Phonology of Common Slavic (Heidelberg, 1964), pp.159–60.Google Scholar

27 Jackson, , LHEB, pp.119–20.Google Scholar The Lowland Zone comprises the fertile and relatively densely populated plains ‘roughly south and east of a line drawn from the Vale of York past the southern end of the Pennines and along the Welsh border to the fringes of the hilly country of Devon and Cornwall’ (ibid. p. 96). In this area the majority of Latin loan-words were borrowed into Celtic (see also below, n. 96), while the Highland Zone became an area of retreat for the Celtic population of the Lowland Zone. According to Jackson (ibid. p. 120), the Highland Zone ‘from having been the home of semi-barbarous hillmen kept in subjection by the Roman garrison, had now become the last refuge of Roman life in Britain, and the sphere of powerful half-Romanized Christian chiefs. Many of the inhabitants of the Lowlands had fled here, bringing with them no doubt some remnants of their Roman civilization, and very likely now introducing to the West many of the Latin words borrowed centuries before into their British speech, so that in this way they survived into medieval Welsh, Cornish, and Breton.’

28 Johnson, S., Later Roman Britain (London, 1980), pp. 150–76Google Scholar; Thomas, A. C., Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500 (London, 1981), pp.75–6.Google Scholar The same applies to the abandonment of Dacia by Aurelian in AD 271. As in Britain roughly one hundred and fifty years later, the urban settlements were affected most seriously by the retreat of the Romans.

30 Ibid.; this percentage does not take into account the medieval and modern loans from Latin and only refers to the size of the lexicon, not the frequency of the lexemes. Figures vary depending on the basis of computation. Haarmann quotes a study by D. Macrea who estimated the share of original Latin words including derivations at some twenty per cent, compared with sixteen per cent of Slavic loan-words, twenty-nine per cent of French loan words and thirty-three per cent of words of other origin (including modern Latinisms). Haarmann’s corpus comprises 1771 Daco-Rumanian lexemes; see Haarmann, H., Balkanlinguistik (1) Areallinguistik und Lexikostatistik des balkanlateinischen Wortschatzes, Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik 93 (Tübingen, 1978), 16–17 and 150–2.Google Scholar

31 See above, p. 1, nn. 2 and 3. A comparison of the number of Latin loan-words in languages situated on the periphery of the Romania reveals that Welsh includes some 700 Latin loan words, compared with 674 in Basque, 636 in Albanian, 483 in the Germanic languages and 471 in Breton; see Haarmann, H., Der lateinische Einfluβ in den Interferenzzonen am Rande der Romania. Vergleichende Studien zur Sprachkontaktforschung, Romanistik in Geschichte und Gegenwart 5 (Hamburg, 1979), 35.Google ScholarJackson, K., ‘The British Language during the Period of the English Settlements’, Studies in Early British History, ed. Chadwick, N. K. (Cambridge, 1954), pp.61–82, at 62Google Scholar, estimates the number of Latin loan-words in British at roughly one thousand. I believe that the number of loan-words, especially in the Germanic languages, is somewhat higher, but nevertheless the general proportions become sufficiently clear; see also above, p. 1.

32 Cf. the illuminating account of Reichenkron, G., Historische Latein-Altromanische Grammatik. I. Teil (Wiesbaden, 1965), pp. 347–54.Google Scholar The ditinction of Verkehrssprache and Heimsprache (the native languages like Dacian, Thracian or Illyrian) goes back to E. Gamillscheg (see below, n. 70).

33 For a convenient summary of the discussion on romanization and continuity in Dacia, see Arvinte, V., ‘Die Entstehung der rumänischen Sprache und des rumänischen Volkes im Lichte der jüngsten Forschung’, in his Die Rumänen. Ursprung, Volks- und Landesnamen, Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik 114 (Tübingen, 1980), 11–36, esp. 20–31.Google Scholar

34 Haarmann, , Der lateinische Lehnwortschatz im Kymrischen, p.212Google Scholar, contends that the romanization of Roman Britain could only have been superficial since the province possessed only four coloniae compared with Dacia’s eight and that generally the net of settlements was wide-meshed. This argument is, however, not wholly convincing since in both provinces the towns disappeared after the retreat of the Roman military.

35 In ‘The British Language during the Period of the English Settlements’, p.61Google Scholar, Jackson, seems to be more uncertain about this than in his LHEB, p. 109.Google Scholar

36 Ibid.; the use of Latin in the army as an instrument of romanization is rightly stressed by Salway, P., Roman Britain (Oxford, 1981), p. 508.Google Scholar On the other hand he assumes that British Latin ‘remained a second language, but like English in India it was not only indispensable for public affairs but the only practical lingua franca in what was becoming a very mixed population’ (ibid. p. 506). This Verkehrssprache is apparently identified by Salway with ‘the rather archaic type of spoken Latin which appears to have been more common in Britain than in other western provinces’ (ibid. pp. 506–7) restricted to an isolated Romano-British upper class. From the discussion above it becomes plain that, in fact, we have to deal with at least two varieties of Latin. Salway also misunderstands the character of the Latin loan-words in Welsh which in his view are motivated primarily by the introduction of new things and concepts. A brief look at the composition of the Latin loan vocabulary in Welsh shows that the Celts were subject to a far-reaching romanization. If this was not so why should they have borrowed, for instance, L piscis > W pysc, pysg? Cf. Reichenkron, , Historische Latein-Altromanische Grammatik, pp. 324–7.Google Scholar

37 The continuity of Latin was denied by Loth, J., Les mots latins dans les langues brittoniques (gallois, armoricain, cornique) avec une introduction sur la romanisation de l’ile de Bretagne (Paris, 1892), pp. 10–11Google Scholar (for Loth’s discussion of Pogatscher’s Lautlehre, see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 30–8).Google Scholar The most prominent proponent of discontinuity in recent times is Jackson, K., ‘The British Language during the Period of the English Settlements’, p. 62Google Scholar: ‘However, by and large, Britain was a Celtic-speaking country, and there is no basis for the view still sometimes expressed that but for the English invasion we should have been speaking some sort of Romance language, allied to French, at the present day.’ See also his ‘The British Languages and their Evolution’, The Mediaeval World, ed. Daiches, D. and Thorlby, A. (London, 1973), pp. 113–26, at 119.Google Scholar Loth’s and Jackson’s views are adopted by Baugh, A. C. and Cable, T., A History of the English Language, 3rd ed. (London, 1978), p. 46.Google Scholar According to Baugh only five words were borrowed during the ‘Insular’ period (‘Latin Influence of the First Period’): OE caester, port, munt, torr and wic. For a discussion of Baugh’s presentation, see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 68–71.Google Scholar

38 Murray, J. A. H., ‘English Language’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed. (London, 1882) VIII, 390–1.Google Scholar For similar views on the continuity of Latin, see below, p. 13; Pogatscher, , Lautlebre, p. 13Google Scholar; Reichenkron, , Historische Latein-Altromanische Grammatik, p. 321Google Scholar; Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 9–13.Google Scholar

39 Wyld, H. C., The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue: an Introduction to Philological Method (London, 1906), p. 243.Google Scholar Wyld’s treatment of the Latin loan-words is one of the best ones in early textbooks. A comparatively extensive survey of the subject is also given by Sheard, J. A., The Words We Use (London, 1954)Google Scholar, adopting Pogatscher’s model.

40 Ibid. p. 246; ‘In cases where Latin words contain no test sounds such as intervocalic stops, there cannot be absolute certainty as to whether they belong to the earliest continental class of loans, or whether they were acquired early in the English period, and even the fact that the same word exists in OHG or OSax does not necessarily settle the matter in favor of the former class, since each language may have adopted the words independently. On the otherhand, words which retain the Latin intervocalic t, etc. might belong either to the Continental period or the late English, if their vowels are not such as are liable to early English sound changes.’

41 Poerck, G. de, ‘La diphtongaison des voyelles fermées du latin, principalement dans le domaine gallo-romance, et la palatalisation de u’, Romanica Gandenia 1 (1953), 23–92, at 45–60 (‘Le témoignage du britto-roman’).Google Scholar

42 Cf. Jackson, , LHEB, p. 5Google Scholar: ‘Britto-Romance’ must not be confused with the term ‘Romano-British’ which ‘is confined to forms of the [British] language reported by Roman writers in Latinized spelling; and the term is stretched to include those given by Greek authors, chiefly derived from Latin sources, in Greek spelling, e.g. by Ptolemy.’

43 Reichenkron, , Historische Latein-Altromanische Grammatik, pp. 322–7.Google Scholar

44 Serjeantson, , A History of Foreign Words in English, pp. 271–88.Google Scholar

45 Cf. Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 62–4.Google ScholarStrang, , A History of English, pp. 388–91Google Scholar, apparently relies on the lists of Serjeantson but does not provide a coherent model of periodization, a situation partly based on a misunderstanding of Jackson’s view. Although she accepts Jackson’s theory of a conservative British Latin, she assumes that ‘very many Latin words passed into OE at this stage’ partly borrowed from ‘Latin-speaking Britons who remained among them’ (ibid. p. 390). This way, however, Jackson regarded as improbable, since in his view the majority of the educated Celtic upper class retreated to the Highland Zone not immediately affected by the Anglo-Saxon onslaught. Strang rightly takes into account the possibility that in the fifth and sixth centuries there were ‘Continental loans resulting from the close contacts the English still maintained with Europe’ (ibid.). For a detailed discussion of Strang’s treatment of the loan-words, see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 75–80.Google Scholar

46 See above, p. 6, n. 17.

48 Jackson, K., ‘The British Languages and their Evolution’, p. 117Google Scholar and LHEB, pp. 108–9Google Scholar: ‘To the ordinary speaker of Vulgar Latin from the Continent, the language from which the loanwords in Brittonic were derived must have seemed stilted and pedantic, or perhaps upper-class and “haw-haw”.’

49 In contrast to LHEB, Jackson in other publications stressed the position of the conservative school Latin as the virtually sole variety of Latin current in Roman Britain. See ‘The British Language during the Period of the English Settlements’, pp. 61–2Google Scholar: ‘There is some very slight reason to think that some of the Latin-speakers, presumably in the cities, used the general middle-class Vulgar Latin lingua franca of the Empire; but there is strong evidence that the upper classes, and specifically the rural aristocracy, spoke Latin with a much more refined and literary, almost archaising pronunciation…’

50 LHEB, pp. 82–94.Google Scholar For a discussion of the features supposed to be specific of British Latin, see Smith, C., ‘Vulgar Latin in Roman Britain: Epigraphic and other Evidence’, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, ed. Temporini, H. and Haase, W., Teil II: Principat 29.2 (Berlin, 1983) [hereafter ANRW], 893–948, at 938–42.Google Scholar

52 There is much important recent work on British Latin. Jackson’s criteria for a conservative variety of British Latin have been severely criticized by Gratwick, A. S., ‘Latinitas Britannica: Was British Latin Archaic?’, Latin and the Vernacular Languages in Early Medieval Britain, ed. Brooks, N. (Leicester, 1982), pp. 1–79.Google Scholar See also, however, MacManus’s, D. critical review of Gratwick’s essay: ‘Linguarum Diversitas: Latin and the Vernaculars in Early Medieval Britain’, Peritia 3 (1987), 151–88.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Evidence of British Vulgar Latin has been adduced by Mann, J. C., ‘Spoken Latin in Britain as evidenced by the Inscriptions’, Britannia 2 (1971), 218–24CrossRefGoogle Scholar; E. P. Hamp, ‘Social Gradience’; Shiel, N., ‘The Coinage of Carausius as a Source of Vulgar Latin’, Britannia 6 (1975), 146–8CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Campanile, E., ‘Valutazione del latino di Britannia’, Studi e saggi linguistici 9 (1969), 87–110Google Scholar; a comprehensive survey including an extensive bibliography is given by Smith, ‘Vulgar Latin in Roman Britain: Epigraphic and other Evidence’ (cited above, n. 50). The language situation in Roman Britain is discussed by Evans, D. Ellis, ‘Language Contact in Pre-Roman and Roman Britain’, ANRW 29.2 (1983), 949–87Google Scholar: Polomé, E. C.;, ‘The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire’, ANRW 29.2 (1983), 509–53, at 532–4Google Scholar; Thomas, , Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500, pp. 71–9Google Scholar; Schmidt, K. H., ‘La romanité des Iles britanniques’, Actes du XVIIIe Congrès international de linguistique et de philologie romanes, ed. ämer, D., 2 vols. (Tübingen, 1992) 1, 188–209.Google Scholar

58 MacManus, , ‘Latin and the Vernaculars’, p. 161.Google Scholar This new interpretation goes back to Wright’s, R. important book, Late Latin and Early Romance in Spain and Carolingian France (Liverpool, 1982).Google Scholar That Christian Latin in its early stage had by no means a literary and conservative pronunciation is also shown by the category of early Christian loan-words in Old English; see above, p. 4, n. 9.

59 Jackson’s view that the so-called Lowland Zone was abandoned by the majority of the native Celts retreating in the Highland Zone can be doubted in the light of the archaeological evidence, which suggests a continuity of settlement. See Jackson, , LHEB, p. 119Google Scholar and Thomas, , Christianity in Roman Britain, pp. 75–6.Google Scholar

61 Ibid. p. 255: ‘The conclusion must be that during the period of Pogatscher’ Insular borrowings, c. 450–600, the possibility of contact between Latin-speaking Britons and the English cannot be excluded, though it is not likely to have been more than trifling. Whether any Latin words were, in fact, adopted by the English in this way is a different question.’

63 See e.g. Emerson, O. F., The History of the English Language (New York and London, 1894), pp. 146–7Google Scholar, who cites ‘beet, box, chervil, fennel, feverfew, gladen, lily, mallow, mint, mul(berry), palm, pea, pear, pepper, periwinkle, pine, plant, plum, poppy, savine, spelt’ as tree- and plant-names presumably borrowed in the context of monastic horticulture and medicine. Krapp, , Modern English. Its Growth and Present Use, p. 216Google Scholar, maintains that besides plant-names like ‘decar’ or ‘box’ many words of everyday-life like ‘butter, cheese, kitchen, mill, cup, kettle’ were borrowed only in the Christian period: ‘A number of those words were plainly taken over because of the superiority of the monastery cooks and cooking over the native, just as today English has a kind of kitchen-French which has come into the language in a similar way.’ Likewise Bourcier, G., An Introduction to the History of the English Language, ed. Clark, C. (London, 1981), pp. 38–9Google Scholar, subsumes words like ‘box, chalk, cook, dish, fever, kitchen, pear’ under the group of Christian loan-words. According to Baugh and Cable, A History of the English Language, §§ 60–2, nearly all plant-names are of Christian origin.

64 Jackson’s view of a conservative variety of British Latin has often been misinterpreted. Jackson never held the view that British Latin due to a supposed relative geographical isolation generally was of a conservative or archaic nature. Jackson’s new approach consisted in the introduction of the sociolinguistic concept of registers or grades thereby abolishing the concept of a uniform and monolithic Vulgar Latin. Pogatscher’s view of an identity of British Latin and Gallo-Romance (see above, p. 6, n. 17) and Jackson’s description of a socially differentiated British Latin are not incompatible, the latter revealing the diastratic multiformity of Vulgar Latin.

66 The lowering of unaccented final L /u/ > /o/ takes place at the end of the fifth century while the lowering of tonic /u/ is a process of the fourth century. See Straka, G., ‘L’evolution phonétique du latin au français sous l’effet de l’énergie et de la faiblesse articulatoires’, Les sons et les mots. Choix d’études de phonétique et de linguistique (Paris, 1979), pp. 257–8Google Scholar; Chaussée, F. de la, Initiation ´ la phonétique historique de l’ancien français, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1982), p. 190.Google Scholar

68 Corazza, V. D., ‘Inglese antico læden “latino”,’ Feor ond neah. Scritti di filologia germanica in memoria di Augusto Scafidi Abbate, ed. Lendinara, P. and Melazzo, L. (Palermo, 1983), pp. 129–41, at 137–8Google Scholar; see also Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 581–2.Google Scholar If the Celtic etymon was already *laden the problem of Old English i-mutation would be irrelevant.

70 See Gamillscheg, E., Romania Germanica. Sprach- und Siedlungsgeschichte der Germanen auf dem Boden des alten Römerreicbes, I. Zu den ältesten Berührungen zwischen Römern und Germanen. Die Franken, 2nd ed. (Berlin, 1970), pp. 166–7Google Scholar; Müller, G. and Frings, T., Germania Romana II. Dreissig Jahre Forschung Romanischer Wörter, Mitteldeutsche Studien 19.2 (Halle, 1968), 167–8.Google Scholar

73 For a discussion of OE cæfester, see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 613–24.Google Scholar

74 Wyld, , The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue, p. 244.Google Scholar

75 Pogatscher, , Lautlehre, pp. 13–14.Google Scholar For L /a:/ > Proto-W /O:/, see Jackson, , LHEB, pp. 287–92Google Scholar; e.g. the river-name Don which can be derived from Romano-British Dānum > Proto—W. *Dōn> OE *Dōn. There is no convincing explanation of OE ag in popœg.

76 Jackson, , LHEB, p. 290Google Scholar, suggests that in some cases (e.g. L Iānŭārĭus > W Ionor; L nātālĩcĭa > Middle W Nodolye beside W Nădolig) a Latin pretonic /a:/ was not shortened by the conservative upper-class speakers of British Latin. Lower-class speakers of British Vulgar Latin would have pronounced a shortened /a/. Without having recourse to the concept of a conservative British Latin, this case is, however, easily explainable by assuming a variation of L /a:/~/a/ at the time of borrowing.

77 See the doubts expressed by Gratwick, discussed by MacManus, , ‘Latin and the Vernaculars’, pp. 163–5Google Scholar, and the utter rejection of the usefulness of dating the loan-words by Vennemann, T., ‘Betrachtung zum Alter der hochgermanischen Lautverschiebung’, Atthochdeutsch. I: Grammatik, Glossen und Texte, ed. Bergmann, R., Tiefenbach, H. and Voeth, L. (Heidelberg, 1987), pp. 29–53, at 33.Google Scholar Cf. also Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 125–7.Google Scholar

80 See Wollmann, ‘Die Chronologie des altenglischen i-Umlauts’ (cited above, n. 69).

84 Ibid. pp. 189–90, citing Pope, M. K., From Latin to Modern French (Manchester, 1934), §§ 164, 180 and 336.Google Scholar Straka, however, proposes an earlier date for /ß/>/b/ which he believes to be current already in the course of the fifth century; this early date is dependent on Straka’s dating of the voicing of /p/ > /b/ which should have taken place at the end of the fourth century. See de la, Chaussée, Initiation à la phonétique historique de l’ancien français, p. 51Google Scholar and Straka, , Les sons et les mots, pp. 260 and 273.Google Scholar

85 For a survey of the datings, see Wollmann, , Untersuchungen, pp. 437–49Google Scholar; Löfstedt, B., Studienäge zur frühmittelalterlichen Latinität, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia Latina Upsaliensia 1 (Stockholm and Uppsala, 1961), 138–49.Google Scholar

87 See Cravens, T. D., ‘Phonology, Phonetics and Orthography in Late Latin and Romance: the Evidence for early Intervocalic Sonorization’, Latin and the Romance Languages in the Early Middle Ages, ed. Wright, R. (London, 1991), pp. 52–68.Google Scholar

88 Latin loan-words in Old English are frequently cited in the literature on Romance historical phonology. Meyer-Lübke, W., Historische Grammatik der französischen Sprache, 5th ed., 2 vols. (Heidelberg, 1934) 1, § 157Google Scholar, cites OE læden and Sīgen as proving Romance voicing to have taken place at the beginning of the fifth century; see also idem, ‘Die lateinische Sprache in den romanischen Ländern’, Grundriss der romanischen Philologie, ed. Gröber, G., 2nd ed., 4 vols. (Strassburg, 1904–1906) 1, 474.Google Scholar However Meyer-Lübke, W., Grammatik der romanischen Sprachen, 4 vols. (Leipzig, 1890–1902) 1, § 647Google Scholar, places Romance voicing in the sixth century because OE laden seems to have been borrowed only at that time. Battisti, C., Avviamento allo studio del latino volgare (Bari, 1949), pp. 158–9Google Scholar, also adduces the evidence of Latin loan-words in Old English for his dating of the generalization of voicing into the fifth century.

89 Cf. e.g. Frings’s, succinct statement in his Grundlegung einer Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, 3rd ed. (Halle, 1957), p. 26Google Scholar: ‘Wir beobachten ein Einheitsgebiet Gallien, Britannien, Niederlande-Niederrhein mit einer südlichen Grenzsetzung in der Augusta Treverorum oder Colonia Agrippina, Trier oder Köln.’

90 Research on the Latin loan-words specifically in the Northwest-Germanic languages is scant or outdated. For Dutch, see Weijnen, A., ‘Leenworden uit de Latinitas, stratigrafisch beschouwd’, Verslagen en Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Tall- en Letterkunde (1967), pp. 365–480Google Scholar; for Old Frisian, see Wollmann, A., ‘Zu den lateinischen Lehnwörten im Altfriesischen’, Aspects of Old Frisian Philology, ed. Bremmer, R. H., van der Meer, G. and Vries, O. (Amsterdam, 1990), pp. 506–36.Google Scholar

Look up loanword in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language.[1][2] This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because they share an etymological origin, and calques, which involve translation. Loanwords from languages with different scripts are usually transliterated (between scripts), but they are not translated. Additionally, loanwords may be adapted to phonology, phonotactics, orthography, and morphology of the target language. When a loanword is fully adapted to the rules of the target language, it is distinguished from native words of the target language only by its origin. However, often the adaptation is incomplete, so loanwords may conserve specific features distinguishing them from native words of the target language: loaned phonemes and sound combinations, partial or total conserving of the original spelling, foreign plural or case forms or indeclinability.

Examples and related terms[edit]

A loanword is distinguished from a calque (or loan translation), which is a word or phrase whose meaning or idiom is adopted from another language by word-for-word translation into existing words or word-forming roots of the recipient language.[3] Loanwords, in contrast, are not translated.

Examples of loanwords in the English language include café (from French café, which means «coffee»), bazaar (from Persian bāzār, which means «market»), and kindergarten (from German Kindergarten, which literally means «children’s garden»). The word calque is a loanword from the French noun calque («tracing; imitation; close copy»);[4] while the word loanword and the phrase loan translation are calques of the German nouns Lehnwort[5] and Lehnübersetzung.[6]

Loans of multi-word phrases, such as the English use of the French term déjà vu, are known as adoptions, adaptations, or lexical borrowings.[7][8]

Although colloquial and informal register loanwords are typically spread by word-of-mouth, technical or academic loanwords tend to be first used in written language, often for scholarly, scientific, or literary purposes.[9][10]

The terms substrate and superstrate are often used when two languages interact. However, the meaning of these terms is reasonably well-defined only in second language acquisition or language replacement events, when the native speakers of a certain source language (the substrate) are somehow compelled to abandon it for another target language (the superstrate).[11][relevant?]

Most of the technical vocabulary of classical music (such as concerto, allegro, tempo, aria, opera, and soprano) is borrowed from Italian,[12] and that of ballet from French.[13] Much of the terminology of the sport of fencing also comes from French. Many loanwords come from prepared food, drink, fruits, vegetables, seafood and more from languages around the world. In particular, many come from French cuisine (crêpe, Chantilly, crème brûlée), Italian (pasta, linguine, pizza, espresso), and Chinese (dim sum, chow mein, wonton).

Linguistic classification[edit]

The studies by Werner Betz (1971, 1901), Einar Haugen (1958, also 1956), and Uriel Weinreich (1963) are regarded as the classical theoretical works on loan influence.[14] The basic theoretical statements all take Betz’s nomenclature as their starting point. Duckworth (1977) enlarges Betz’s scheme by the type «partial substitution» and supplements the system with English terms. A schematic illustration of these classifications is given below.[15]

The phrase «foreign word» used in the image below is a mistranslation of the German Fremdwort, which refers to loanwords whose pronunciation, spelling, inflection or gender have not been adapted to the new language such that they no longer seem foreign. Such a separation of loanwords into two distinct categories is not used by linguists in English in talking about any language. Basing such a separation mainly on spelling is (or, in fact, was) not common except amongst German linguists, and only when talking about German and sometimes other languages that tend to adapt foreign spellings, which is rare in English unless the word has been widely used for a long time.

According to the linguist Suzanne Kemmer, the expression «foreign word» can be defined as follows in English: «[W]hen most speakers do not know the word and if they hear it think it is from another language, the word can be called a foreign word. There are many foreign words and phrases used in English such as bon vivant (French), mutatis mutandis (Latin), and Schadenfreude (German).»[16] This is not how the term is used in this illustration:

On the basis of an importation-substitution distinction, Haugen (1950: 214f.) distinguishes three basic groups of borrowings: «(1) Loanwords show morphemic importation without substitution…. (2) Loanblends show morphemic substitution as well as importation…. (3) Loanshifts show morphemic substitution without importation». Haugen later refined (1956) his model in a review of Gneuss’s (1955) book on Old English loan coinages, whose classification, in turn, is the one by Betz (1949) again.

Weinreich (1953: 47ff.) differentiates between two mechanisms of lexical interference, namely those initiated by simple words and those initiated by compound words and phrases. Weinreich (1953: 47) defines simple words «from the point of view of the bilinguals who perform the transfer, rather than that of the descriptive linguist. Accordingly, the category ‘simple’ words also includes compounds that are transferred in unanalysed form». After this general classification, Weinreich then resorts to Betz’s (1949) terminology.

In English[edit]

The English language has borrowed many words from other cultures or languages. For examples, see Lists of English words by country or language of origin and Anglicisation.

Some English loanwords remain relatively faithful to the original phonology even though a particular phoneme might not exist or have contrastive status in English. For example, the Hawaiian word ʻaʻā is used by geologists to specify lava that is thick, chunky, and rough. The Hawaiian spelling indicates the two glottal stops in the word, but the English pronunciation, , contains at most one. The English spelling usually removes the ʻokina and macron diacritics.[17]

Most English affixes, such as un-, -ing, and -ly, were used in Old English. However, a few English affixes are borrowed. For example, the verbal suffix -ize (American English) or ise (British English) comes from Greek -ιζειν (-izein) through Latin -izare.

Languages other than English[edit]

Transmission in the Ottoman Empire[edit]

During more than 600 years of the Ottoman Empire, the literary and administrative language of the empire was Turkish, with many Persian, and Arabic loanwords, called Ottoman Turkish, considerably differing from the everyday spoken Turkish of the time. Many such words were adopted by other languages of the empire, such as Albanian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek, Hungarian, Ladino, Macedonian, Montenegrin and Serbian. After the empire fell after World War I and the Republic of Turkey was founded, the Turkish language underwent an extensive language reform led by the newly founded Turkish Language Association, during which many adopted words were replaced with new formations derived from Turkic roots. That was part of the ongoing cultural reform of the time, in turn a part in the broader framework of Atatürk’s Reforms, which also included the introduction of the new Turkish alphabet.

Turkish also has taken many words from French, such as pantolon for trousers (from French pantalon) and komik for funny (from French comique), most of them pronounced very similarly. Word usage in modern Turkey has acquired a political tinge: right-wing publications tend to use more Arabic or Persian originated words, left-wing ones use more adopted from European languages, while centrist ones use more native Turkish root words.[18]

Dutch words in Indonesian[edit]

Almost 350 years of Dutch presence in what is now Indonesia have left significant linguistic traces. Though very few Indonesians have a fluent knowledge of Dutch, the Indonesian language inherited many words from Dutch, both in words for everyday life (e.g., buncis from Dutch boontjes for (green) beans) and as well in administrative, scientific or technological terminology (e.g., kantor from Dutch kantoor for office).[19] The Professor of Indonesian Literature at Leiden University,[20] and of Comparative Literature at UCR,[21] argues that roughly 20% of Indonesian words can be traced back to Dutch words.[22]

Dutch words in Russian[edit]

In the late 17th century, the Dutch Republic had a leading position in shipbuilding. Czar Peter the Great, eager to improve his navy, studied shipbuilding in Zaandam and Amsterdam. Many Dutch naval terms have been incorporated in the Russian vocabulary, such as бра́мсель (brámselʹ) from Dutch bramzeil for the topgallant sail, домкра́т (domkrát) from Dutch dommekracht for jack, and матро́с (matrós) from Dutch matroos for sailor.

Romance languages[edit]

A large percentage of the lexicon of Romance languages, themselves descended from Vulgar Latin, consists of loanwords (later learned or scholarly borrowings) from Latin. These words can be distinguished by lack of typical sound changes and other transformations found in descended words, or by meanings taken directly from Classical or Ecclesiastical Latin that did not evolve or change over time as expected; in addition, there are also semi-learned terms which were adapted partially to the Romance language’s character. Latin borrowings can be known by several names in Romance languages: in Spanish, for example, they are usually referred to as «cultismos»,[23][24] and in Italian as «latinismi».

Latin is usually the most common source of loanwords in these languages, such as in Italian, Spanish, French, etc.,[25][26] and in some cases the total number of loans may even outnumber inherited terms[27][28] (although the learned borrowings are less often used in common speech, with the most common vocabulary being of inherited, orally transmitted origin from Vulgar Latin). This has led to many cases of etymological doublets in these languages.

For most Romance languages, these loans were initiated by scholars, clergy, or other learned people and occurred in Medieval times, peaking in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance era[26]— in Italian, the 14th century had the highest number of loans.[citation needed] In the case of Romanian, the language underwent a «re-Latinization» process later than the others (see Romanian lexis, Romanian language § French, Italian, and English loanwords), in the 18th and 19th centuries, partially using French and Italian words (many of these themselves being earlier borrowings from Latin) as intermediaries,[29] in an effort to modernize the language, often adding concepts that did not exist until then, or replacing words of other origins. These common borrowings and features also essentially serve to raise mutual intelligibility of the Romance languages, particularly in academic/scholarly, literary, technical, and scientific domains. Many of these same words are also found in English (through its numerous borrowings from Latin and French) and other European languages.

In addition to Latin loanwords, many words of Ancient Greek origin were also borrowed into Romance languages, often in part through scholarly Latin intermediates, and these also often pertained to academic, scientific, literary, and technical topics. Furthermore, to a lesser extent, Romance languages borrowed from a variety of other languages; in particular English has become an important source in more recent times. The study of the origin of these words and their function and context within the language can illuminate some important aspects and characteristics of the language, and it can reveal insights on the phenomenon of lexical borrowing in linguistics as a method of enriching a language.[30]

Cultural aspects[edit]

According to Hans Henrich Hock and Brian Joseph, «languages and dialects … do not exist in a vacuum»: there is always linguistic contact between groups.[31] The contact influences what loanwords are integrated into the lexicon and which certain words are chosen over others.

Leaps in meaning[edit]

In some cases, the original meaning shifts considerably through unexpected logical leaps. The English word Viking became Japanese バイキング (baikingu), meaning «buffet», because the first restaurant in Japan to offer buffet-style meals, inspired by the Nordic smörgåsbord, was opened in 1958 by the Imperial Hotel under the name «Viking».[32] The German word Kachel, meaning «tile», became the Dutch word kachel meaning «stove», as a shortening of kacheloven, from German Kachelofen, a cocklestove.

See also[edit]

- Bilingual pun

- Hybrid word

- Inkhorn term

- Language contact

- Neologism

- Phono-semantic matching

- Reborrowing

- Semantic loan

References[edit]

- ^ «loanword». Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Jespersen, Otto (1964). Language. New York: Norton Library. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-393-00229-4.

Linguistic ‘borrowing’ is really nothing but imitation.

- ^ Hoffer, Bates L. (2005). «Language Borrowing and the Indices of Adaptability and Receptivity» (PDF). Intercultural Communication Studies. Trinity University. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. «The American Heritage Dictionary entry: Calque». ahdictionary.com.

- ^ Carr, Charles T. (1934). The German Influence on the English Language. Society for Pure English Tract No. 42. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 75. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Knapp, Robbin D. «Robb: German English Words germanenglishwords.com». germanenglishwords.com.

- ^ Chesley, Paula; Baayen, R. Harald (2010). «Predicting New Words from Newer Words: Lexical Borrowings in French». Linguistics. 48 (4): 1343–74. doi:10.1515/ling.2010.043. S2CID 51733037.

- ^ Thomason, Sarah G. (2001). Language Contact: An Introduction. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

- ^ Algeo, John (2 February 2009). The Origins and Development of the English Language. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1428231450.

- ^ Fiedler, Sabine (May 2017). «Phraseological borrowing from English into German: Cultural and pragmatic implications». Journal of Pragmatics. 113: 89–102. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2017.03.002.

- ^ Weinreich, Uriel (1979) [1953], Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems, New York: Mouton Publishers, ISBN 978-90-279-2689-0

- ^ Shanet 1956: 155.

- ^ Kersley & Sinclair 1979: 3.

- ^ Compare the two survey articles by Oksaar (1992: 4f.), Stanforth (2021) and Grzega (2003, 2018).

- ^ The following comments and examples are taken from Grzega, Joachim (2004), Bezeichnungswandel: Wie, Warum, Wozu?, Heidelberg: Winter, p. 139, and Grzega, Joachim (2003), «Borrowing as a Word-Finding Process in Cognitive Historical Onomasiology», Onomasiology Online 4: 22–42.

- ^ Loanwords by Prof. S. Kemmer, Rice University

- ^ Elbert, Samuel H.; Pukui, Mary Kawena (1986). Hawaiian Dictionary (Revised and enlarged ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8248-0703-0.

- ^ Lewis, Geoffrey (2002). The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925669-3.

- ^ Sneddon (2003), p.162.

- ^ «Hendrik Maier». IDWRITERS. 26 April 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ UCR; Department of Comparative Literature and Languages. «Faculty: Hendrik Maier». UCR Faculty. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Maier, Hendrik M. (8 February 2005). «A Hidden Language – Dutch in Indonesia». UC Berkeley: Institute of European Studies. Retrieved 29 March 2015 – via eScholarship.

- ^ Ángel Luis Gallego Real. «Definiciones de Cultismo, Semicultismo y Palabra Patrimonial» (PDF).

- ^ Posner, Rebecca (5 September 1996). The Romance Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521281393 – via Google Books.

- ^ Patterson, William T. (1 January 1968). «On the Genealogical Structure of the Spanish Vocabulary». Word. 24 (1–3): 309–339. doi:10.1080/00437956.1968.11435535.

- ^ a b «Chjapitre 10: Histoire du français — Les emprunts et la langue française». axl.cefan.ulaval.ca.

- ^ «Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales». cnrtl.fr.

- ^ «Diccionario Critico Etimologico castellano A-CA — Corominas, Joan.PDF». Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ «dex.ro — Dicţionarul explicativ al limbii române». dex.ro.

- ^ K.A. Goddard (1969). «Loan-words and lexical borrowing in Romance». Revue de linguistique romane.

- ^ Hock, Hans Henrich; Joseph., Brian D. (2009). «Lexical Borrowing». Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics (2nd ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 241–78..

- ^ «The Imperial Viking Sal». Imperial Hotel Tokyo. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

Sources[edit]

- Best, Karl-Heinz, Kelih, Emmerich (eds.) (2014): Entlehnungen und Fremdwörter: Quantitative Aspekte. Lüdenscheid: RAM-Verlag.

- Betz, Werner (1949): Deutsch und Lateinisch: Die Lehnbildungen der althochdeutschen Benediktinerregel. Bonn: Bouvier.

- Betz, Werner (1959): «Lehnwörter und Lehnprägungen im Vor- und Frühdeutschen». In: Maurer, Friedrich / Stroh, Friedrich (eds.): Deutsche Wortgeschichte. 2nd ed. Berlin: Schmidt, vol. 1, 127–147.

- Bloom, Dan (2010): «What’s That Pho?». French Loan Words in Vietnam Today; Taipei Times, [ SOCIETY ] What’s that ‘pho’? — Taipei Times

- Cannon, Garland (1999): «Problems in studying loans», Proceedings of the annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 25, 326–336.

- Duckworth, David (1977): «Zur terminologischen und systematischen Grundlage der Forschung auf dem Gebiet der englisch-deutschen Interferenz: Kritische Übersicht und neuer Vorschlag». In: Kolb, Herbert / Lauffer, Hartmut (eds.) (1977): Sprachliche Interferenz: Festschrift für Werner Betz zum 65. Geburtstag. Tübingen: Niemeyer, p. 36–56.

- Gneuss, Helmut (1955): Lehnbildungen und Lehnbedeutungen im Altenglischen. Berlin: Schmidt.

- Grzega, Joachim (2003): «Borrowing as a Word-Finding Process in Cognitive Historical Onomasiology», Onomasiology Online 4, 22–42.

- Grzega, Joachim (2004): Bezeichnungswandel: Wie, Warum, Wozu? Heidelberg: Winter.

- Haugen, Einar (1950): «The analysis of linguistic borrowing». Language, 26(2), 210–231.

- Haugen, Einar. (1956): [Review of Lehnbildungen und Lehnbedeutungen im Altenglischen, by H. Gneuss]. Language, 32(4), 761–766.

- Hitchings, Henry (2008), The Secret Life of Words: How English Became English, London: John Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-6454-3.

- Kersley, Leo; Sinclair, Janet (1979), A Dictionary of Ballet Terms, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-80094-8.

- Koch, Peter (2002): «Lexical Typology from a Cognitive and Linguistic Point of View». In: Cruse, D. Alan et al. (eds.): Lexicology: An International on the Nature and Structure of Words and Vocabularies/Lexikologie: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1142–1178.

- Oksaar, Els (1996): «The history of contact linguistics as a discipline». In: Goebl, Hans et al. (eds.): Kontaktlinguistik/contact linguistics/linguistique de contact: ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung/an international handbook of contemporary research/manuel international des recherches contemporaines. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1–12.

- Shanet, Howard (1956), Learn to Read Music, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-21027-4.

- Stanforth, Anthony W. (2002): «Effects of language contact on the vocabulary: an overview». In: Cruse, D. Alan et al. (eds.) (2002): Lexikologie: ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen/Lexicology: an international handbook on the nature and structure of words and vocabularies. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, p. 805–813.

- Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, (ISBN 978-1-4039-3869-5)

External links[edit]

Look up loanword in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- World Loanword Database (WOLD)

- AfBo: A world-wide survey of affix borrowing

- Daghestanian loans database

Слайд 1KYIV NATIONAL LINGUISTIC UNIVERSITY

Subota S.V.

LECTURE 5

OLD ENGLISH SYNTAX AND VOCABULARY.

Слайд 2Plan

Word Order in OE.

Compound and Complex Sentences in OE. Means of

Connection.

Negation.

OE Vocabulary (Words of IE, CG Origin, loan-words).

Word formation in OE.

Слайд 3Literature

Расторгуева Т.А. История английского языка. – М.: Астрель, 2005. – С.

124-147.

Ильиш Б.А. История английского языка. – Л.: Просвещение, 1972. – С. 56-63, 114-132.

Иванова И.П., Чахоян Л.П. История английского языка. – М.: Высшая школа, 1976. – С.216-231, 239-256.

Студенець Г.І. Історія англійської мови в таблицях. — К.: КДЛУ, 1998. – Tables 55-60

Слайд 5

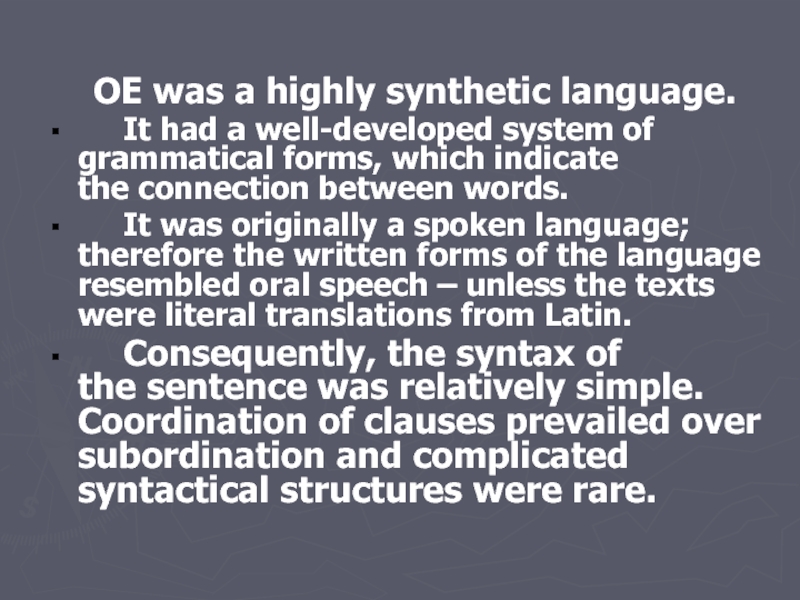

OE was a highly synthetic language.

It had a well-developed system of grammatical forms, which indicate the connection between words.

It was originally a spoken language; therefore the written forms of the language resembled oral speech – unless the texts were literal translations from Latin.

Consequently, the syntax of the sentence was relatively simple. Coordination of clauses prevailed over subordination and complicated syntactical structures were rare.

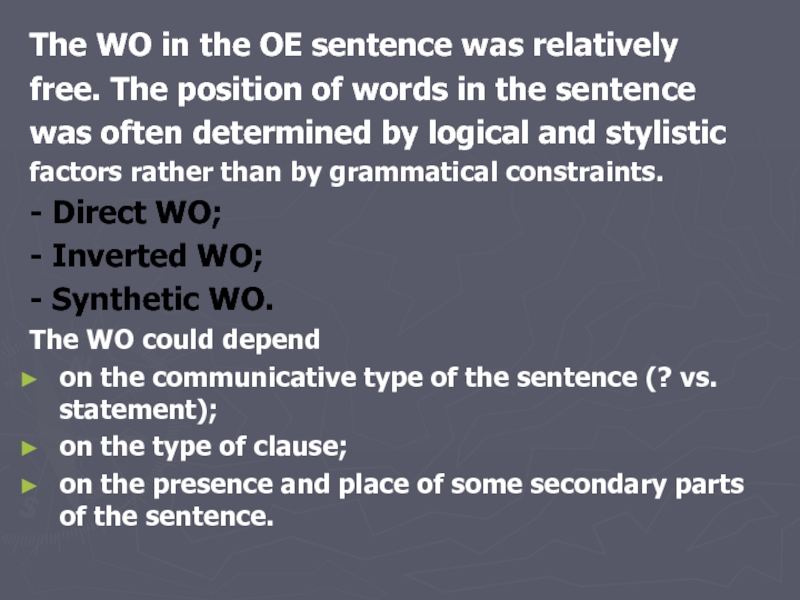

Слайд 6The WO in the OE sentence was relatively

free. The position of

words in the sentence

was often determined by logical and stylistic

factors rather than by grammatical constraints.

— Direct WO;

— Inverted WO;

— Synthetic WO.

The WO could depend

on the communicative type of the sentence (? vs. statement);

on the type of clause;

on the presence and place of some secondary parts of the sentence.

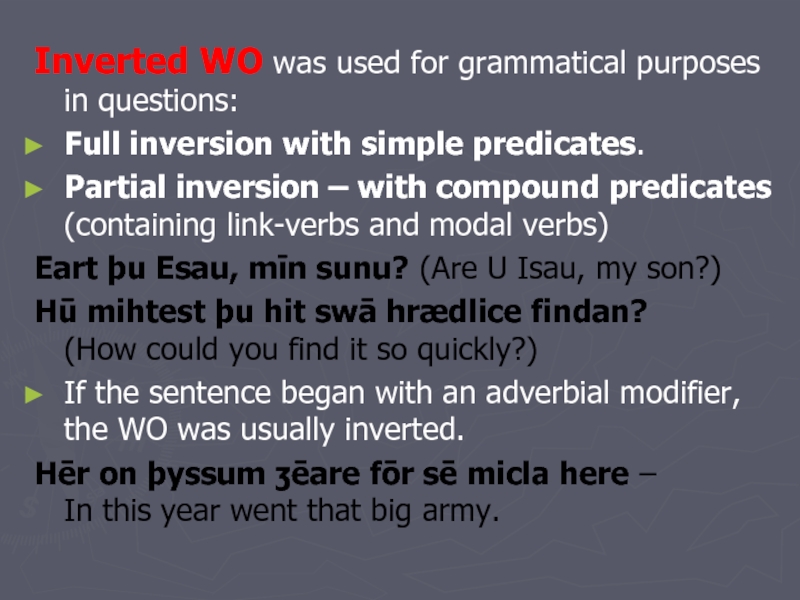

Слайд 7Inverted WO was used for grammatical purposes in questions:

Full inversion with

simple predicates.

Partial inversion – with compound predicates (containing link-verbs and modal verbs)

Eart þu Esau, mīn sunu? (Are U Isau, my son?)

Hū mihtest þu hit swā hrædlice findan? (How could you find it so quickly?)

If the sentence began with an adverbial modifier, the WO was usually inverted.

Hēr on þyssum ʒēare fōr sē micla here – In this year went that big army.

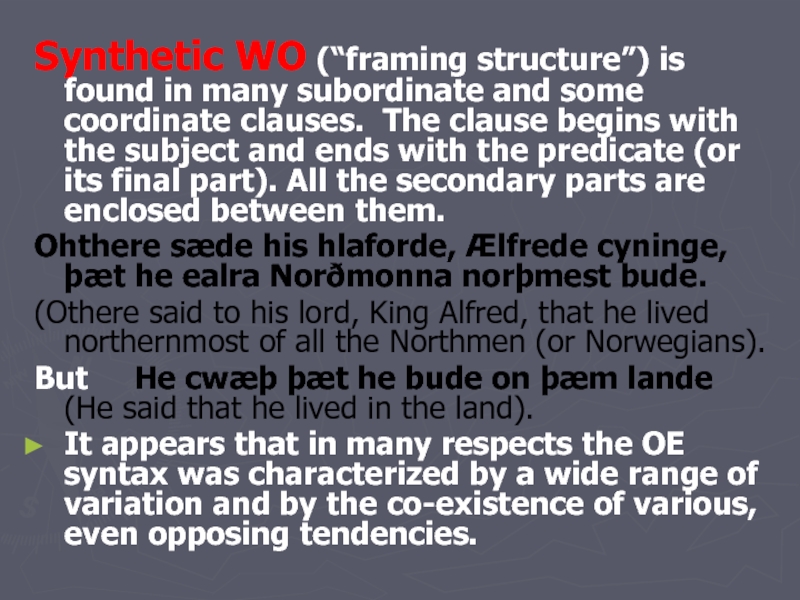

Слайд 8Synthetic WO (“framing structure”) is found in many subordinate and some

coordinate clauses. The clause begins with the subject and ends with the predicate (or its final part). All the secondary parts are enclosed between them.

Ohthere sæde his hlaforde, Ælfrede cyninge, þæt he ealra Norðmonna norþmest bude.

(Othere said to his lord, King Alfred, that he lived northernmost of all the Northmen (or Norwegians).

But He cwæþ þæt he bude on þæm lande (He said that he lived in the land).

It appears that in many respects the OE syntax was characterized by a wide range of variation and by the co-existence of various, even opposing tendencies.

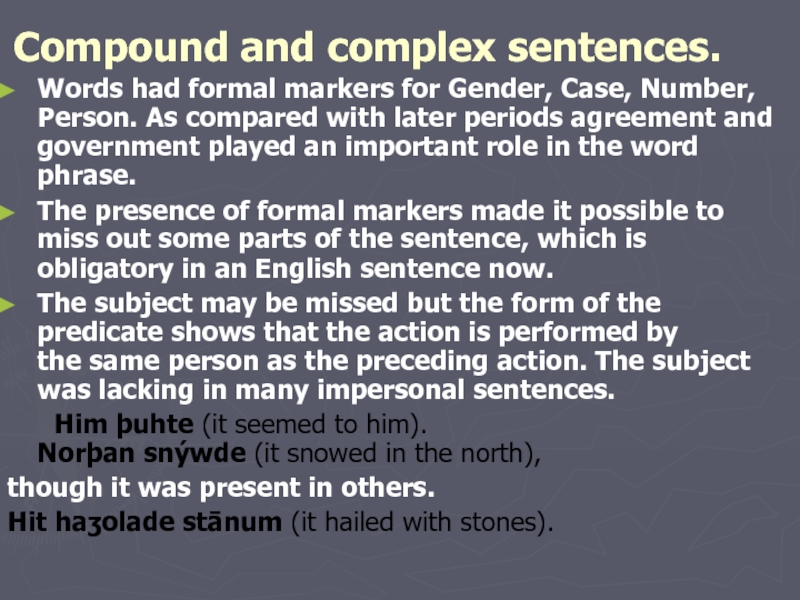

Слайд 9 Compound and complex sentences.

Words had formal markers for Gender, Case,

Number, Person. As compared with later periods agreement and government played an important role in the word phrase.

The presence of formal markers made it possible to miss out some parts of the sentence, which is obligatory in an English sentence now.

The subject may be missed but the form of the predicate shows that the action is performed by the same person as the preceding action. The subject was lacking in many impersonal sentences.

Him þuhte (it seemed to him). Norþan snýwde (it snowed in the north),

though it was present in others.

Hit haʒolade stānum (it hailed with stones).

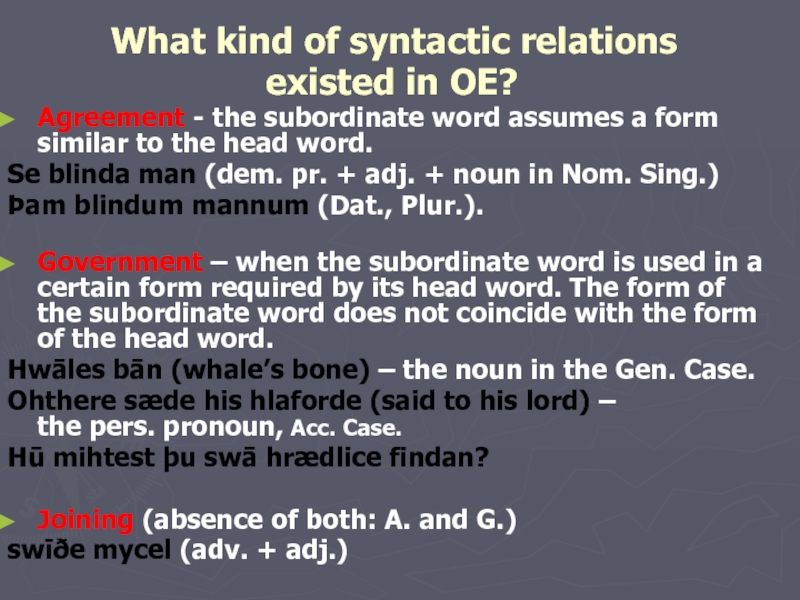

Слайд 10 What kind of syntactic relations

existed in OE?

Agreement —

the subordinate word assumes a form similar to the head word.

Se blinda man (dem. pr. + adj. + noun in Nom. Sing.)

Þam blindum mannum (Dat., Plur.).

Government – when the subordinate word is used in a certain form required by its head word. The form of the subordinate word does not coincide with the form of the head word.

Hwāles bān (whale’s bone) – the noun in the Gen. Case.

Ohthere sæde his hlaforde (said to his lord) – the pers. pronoun, Acc. Case.

Hū mihtest þu swā hrædlice findan?

Joining (absence of both: A. and G.)

swīðe mycel (adv. + adj.)

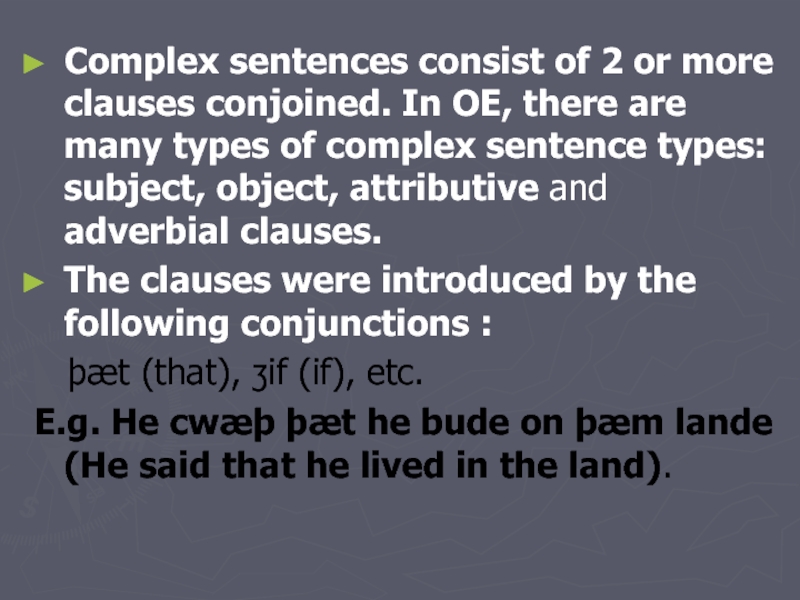

Слайд 11Complex sentences consist of 2 or more clauses conjoined. In OE,

there are many types of complex sentence types: subject, object, attributive and adverbial clauses.

The clauses were introduced by the following conjunctions :

þæt (that), ʒif (if), etc.

E.g. He cwæþ þæt he bude on þæm lande (He said that he lived in the land).

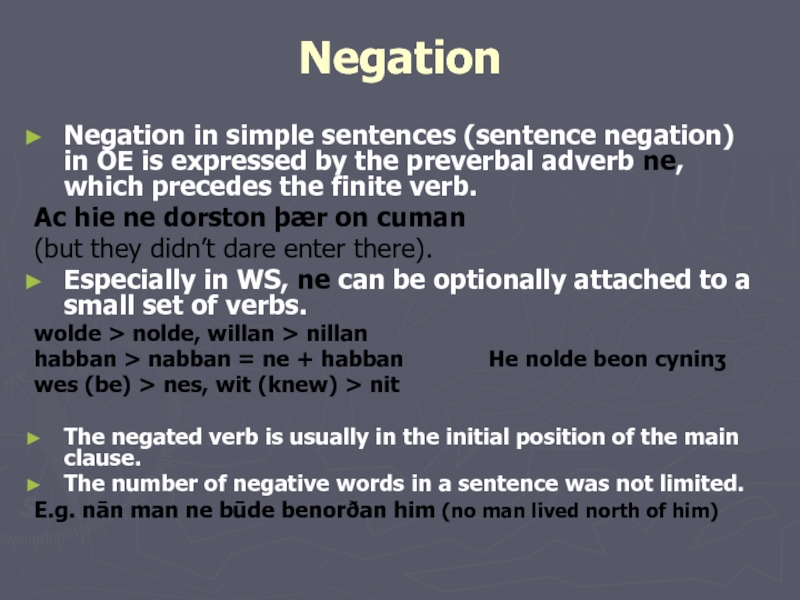

Слайд 12Negation

Negation in simple sentences (sentence negation) in OE is expressed by

the preverbal adverb ne, which precedes the finite verb.

Ac hie ne dorston þær on cuman

(but they didn’t dare enter there).

Especially in WS, ne can be optionally attached to a small set of verbs.

wolde > nolde, willan > nillan

habban > nabban = ne + habban He nolde beon cyninʒ

wes (be) > nes, wit (knew) > nit

The negated verb is usually in the initial position of the main clause.

The number of negative words in a sentence was not limited.

E.g. nān man ne būde benorðan him (no man lived north of him)

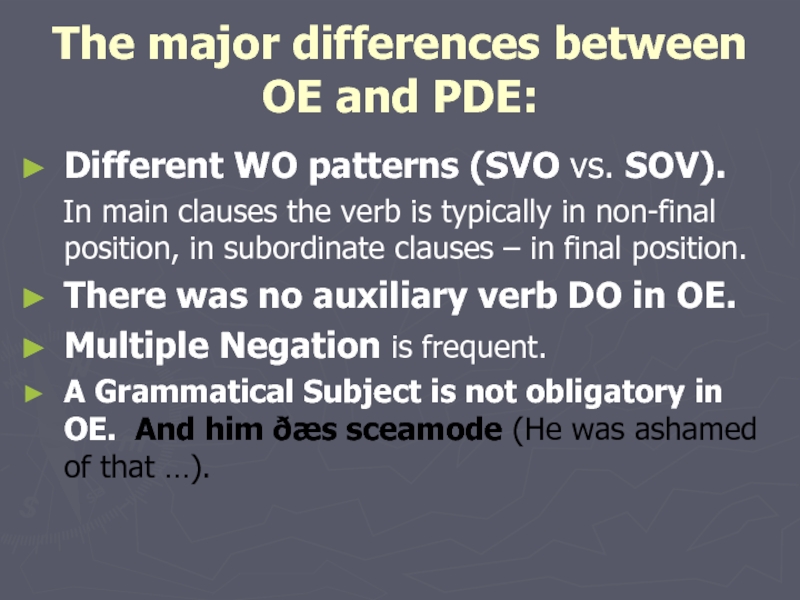

Слайд 13The major differences between OE and PDE:

Different WO patterns (SVO

vs. SOV).

In main clauses the verb is typically in non-final position, in subordinate clauses – in final position.

There was no auxiliary verb DO in OE.

Multiple Negation is frequent.

A Grammatical Subject is not obligatory in OE. And him ðæs sceamode (He was ashamed of that …).

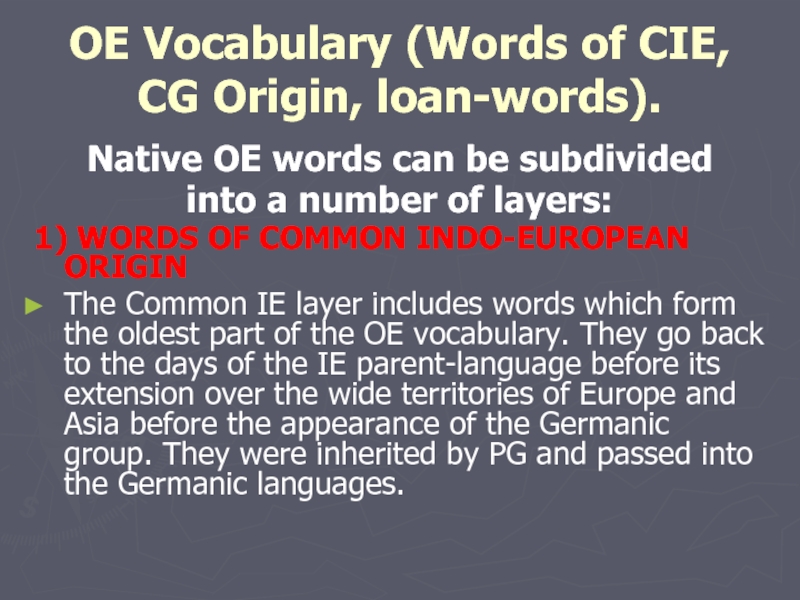

Слайд 14OE Vocabulary (Words of CIE, CG Origin, loan-words).

Native OE words can

be subdivided

into a number of layers:

1) WORDS OF COMMON INDO-EUROPEAN ORIGIN

The Common IE layer includes words which form the oldest part of the OE vocabulary. They go back to the days of the IE parent-language before its extension over the wide territories of Europe and Asia before the appearance of the Germanic group. They were inherited by PG and passed into the Germanic languages.

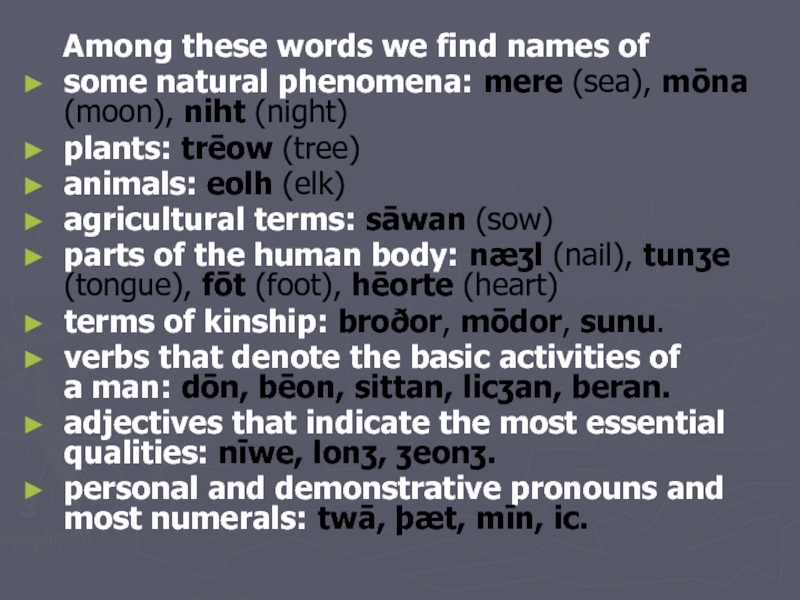

Слайд 15 Among these words we find names of

some natural phenomena:

mere (sea), mōna (moon), niht (night)

plants: trēow (tree)

animals: eolh (elk)

agricultural terms: sāwan (sow)

parts of the human body: næʒl (nail), tunʒe (tongue), fōt (foot), hēorte (heart)

terms of kinship: broðor, mōdor, sunu.

verbs that denote the basic activities of a man: dōn, bēon, sittan, licʒan, beran.

adjectives that indicate the most essential qualities: nīwe, lonʒ, ʒeonʒ.

personal and demonstrative pronouns and most numerals: twā, þæt, mīn, ic.

Слайд 16

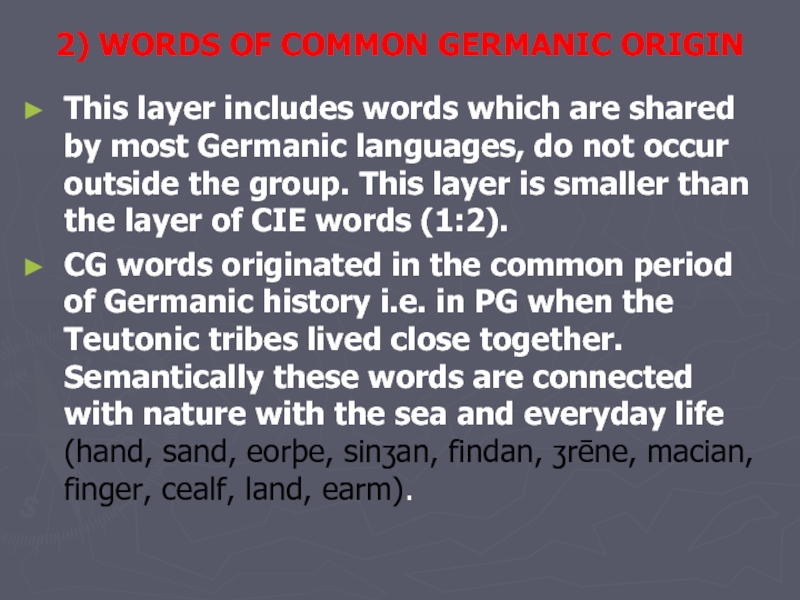

2) WORDS OF COMMON GERMANIC ORIGIN

This layer includes words which

are shared by most Germanic languages, do not occur outside the group. This layer is smaller than the layer of CIE words (1:2).

CG words originated in the common period of Germanic history i.e. in PG when the Teutonic tribes lived close together. Semantically these words are connected with nature with the sea and everyday life (hand, sand, eorþe, sinʒan, findan, ʒrēne, macian, finger, cealf, land, earm).

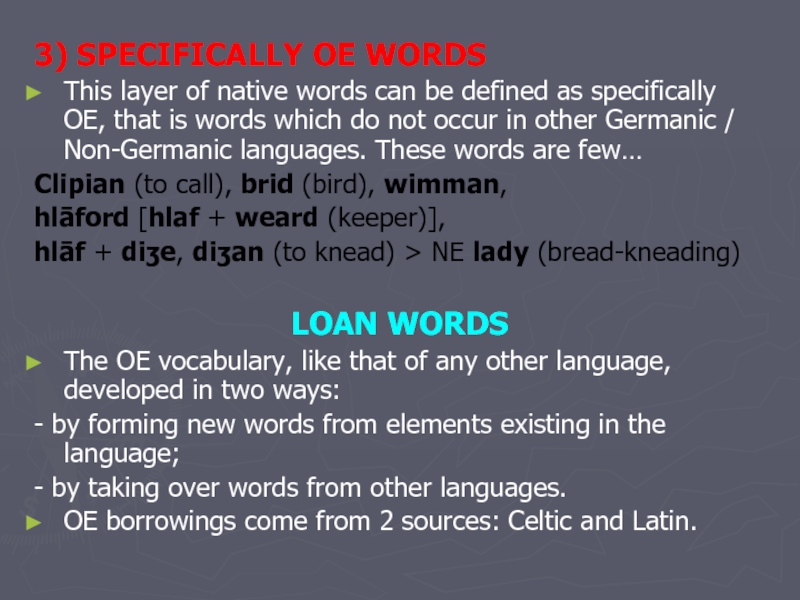

Слайд 173) SPECIFICALLY OE WORDS

This layer of native words can be defined

as specifically OE, that is words which do not occur in other Germanic / Non-Germanic languages. These words are few…

Clipian (to call), brid (bird), wimman,

hlāford [hlaf + weard (keeper)],

hlāf + diʒe, diʒan (to knead) > NE lady (bread-kneading)

LOAN WORDS

The OE vocabulary, like that of any other language, developed in two ways:

— by forming new words from elements existing in the language;

— by taking over words from other languages.

OE borrowings come from 2 sources: Celtic and Latin.

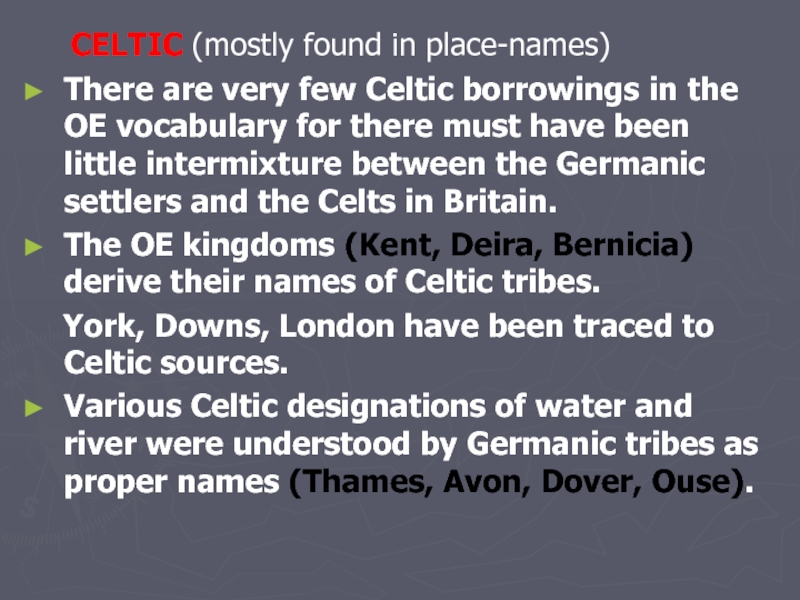

Слайд 18 CELTIC (mostly found in place-names)

There are very few Celtic

borrowings in the OE vocabulary for there must have been little intermixture between the Germanic settlers and the Celts in Britain.

The OE kingdoms (Kent, Deira, Bernicia) derive their names of Celtic tribes.

York, Downs, London have been traced to Celtic sources.

Various Celtic designations of water and river were understood by Germanic tribes as proper names (Thames, Avon, Dover, Ouse).

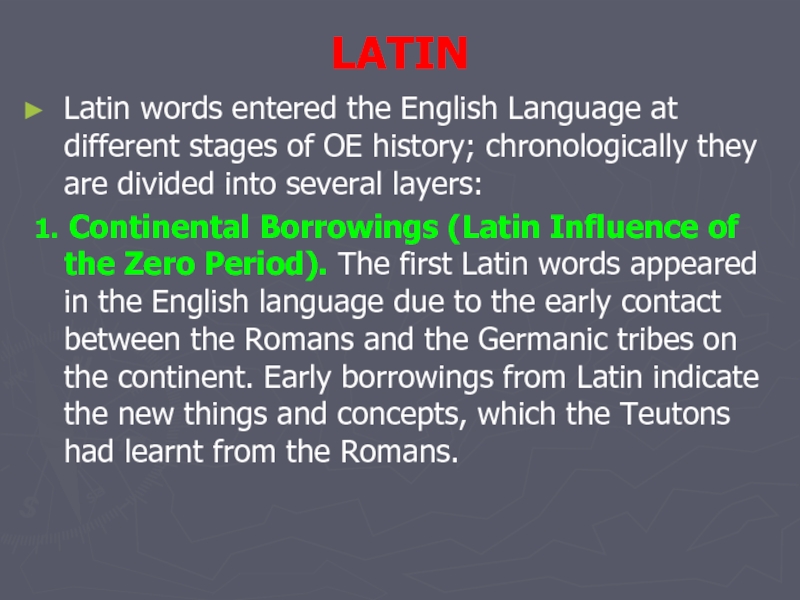

Слайд 20LATIN

Latin words entered the English Language at different stages of

OE history; chronologically they are divided into several layers:

1. Continental Borrowings (Latin Influence of the Zero Period). The first Latin words appeared in the English language due to the early contact between the Romans and the Germanic tribes on the continent. Early borrowings from Latin indicate the new things and concepts, which the Teutons had learnt from the Romans.

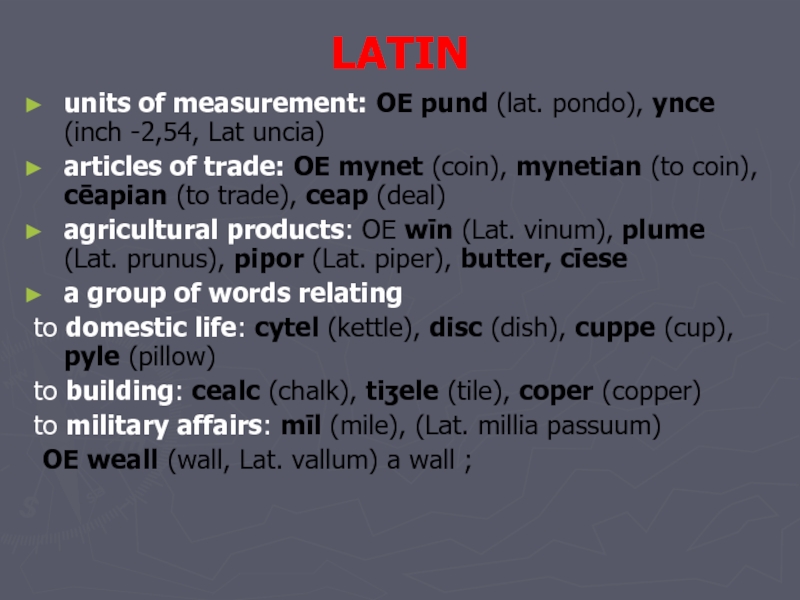

Слайд 21LATIN

units of measurement: OE pund (lat. pondo), ynce (inch -2,54,

Lat uncia)

articles of trade: OE mynet (coin), mynetian (to coin), cēapian (to trade), ceap (deal)

agricultural products: OE wīn (Lat. vinum), plume (Lat. prunus), pipor (Lat. piper), butter, cīese

a group of words relating

to domestic life: cytel (kettle), disc (dish), cuppe (cup), pyle (pillow)

to building: cealc (chalk), tiʒele (tile), coper (copper)

to military affairs: mīl (mile), (Lat. millia passuum)

OE weall (wall, Lat. vallum) a wall ;

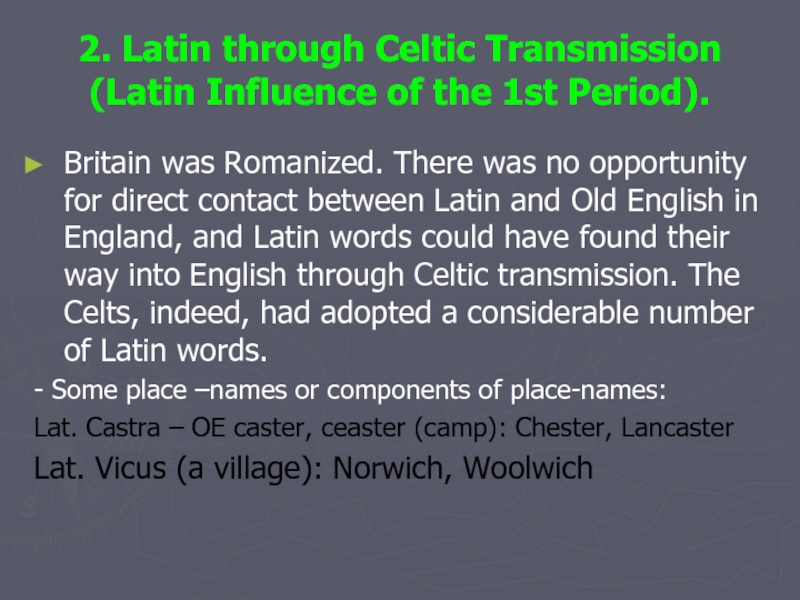

Слайд 222. Latin through Celtic Transmission (Latin Influence of the 1st Period).

Britain

was Romanized. There was no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and Latin words could have found their way into English through Celtic transmission. The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words.

— Some place –names or components of place-names:

Lat. Castra – OE caster, ceaster (camp): Chester, Lancaster

Lat. Vicus (a village): Norwich, Woolwich

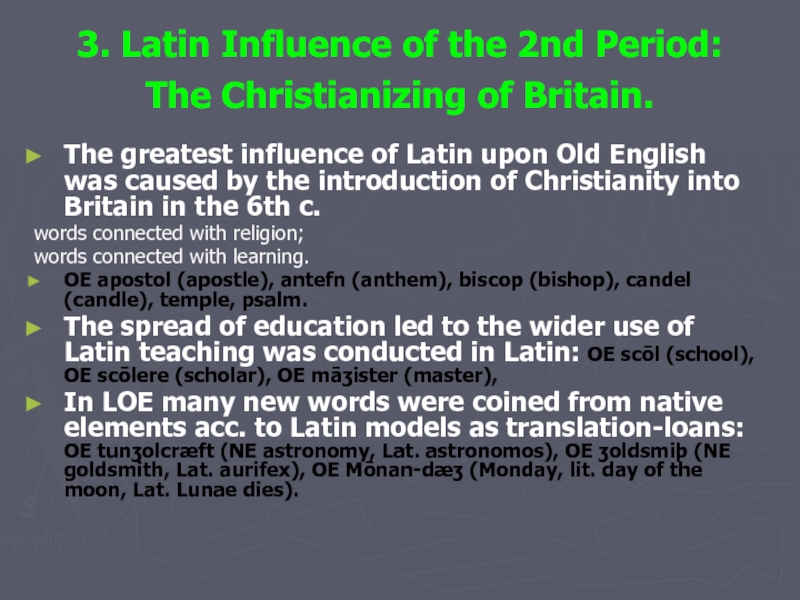

Слайд 233. Latin Influence of the 2nd Period:

The Christianizing of Britain.

The greatest influence of Latin upon Old English was caused by the introduction of Christianity into Britain in the 6th c.

words connected with religion;

words connected with learning.

OE apostol (apostle), antefn (anthem), biscop (bishop), candel (candle), temple, psalm.

The spread of education led to the wider use of Latin teaching was conducted in Latin: OE scōl (school), OE scōlere (scholar), OE māʒister (master),

In LOE many new words were coined from native elements acc. to Latin models as translation-loans: OE tunʒolcræft (NE astronomy, Lat. astronomos), OE ʒoldsmiþ (NE goldsmith, Lat. aurifex), OE Mōnan-dæʒ (Monday, lit. day of the moon, Lat. Lunae dies).

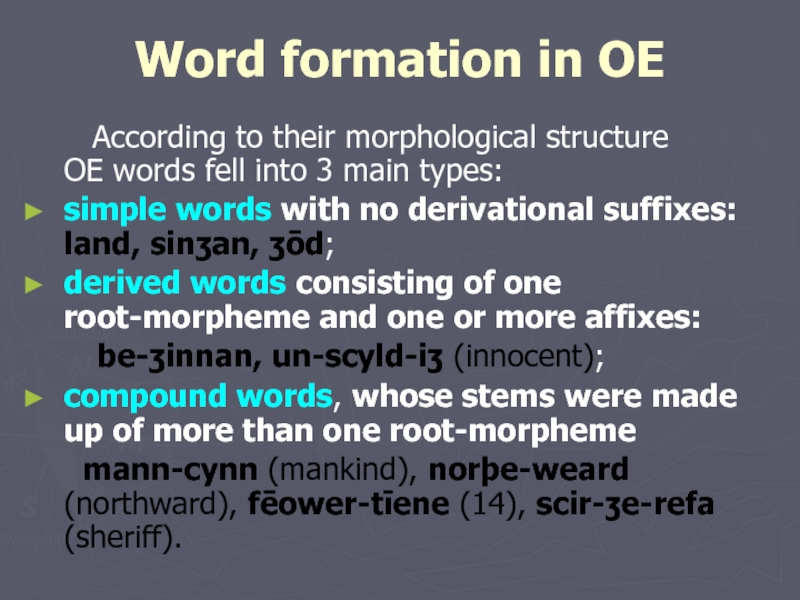

Слайд 24Word formation in OE

According to their morphological

structure OE words fell into 3 main types:

simple words with no derivational suffixes: land, sinʒan, ʒōd;

derived words consisting of one root-morpheme and one or more affixes:

be-ʒinnan, un-scyld-iʒ (innocent);

compound words, whose stems were made up of more than one root-morpheme

mann-cynn (mankind), norþe-weard (northward), fēower-tīene (14), scir-ʒe-refa (sheriff).

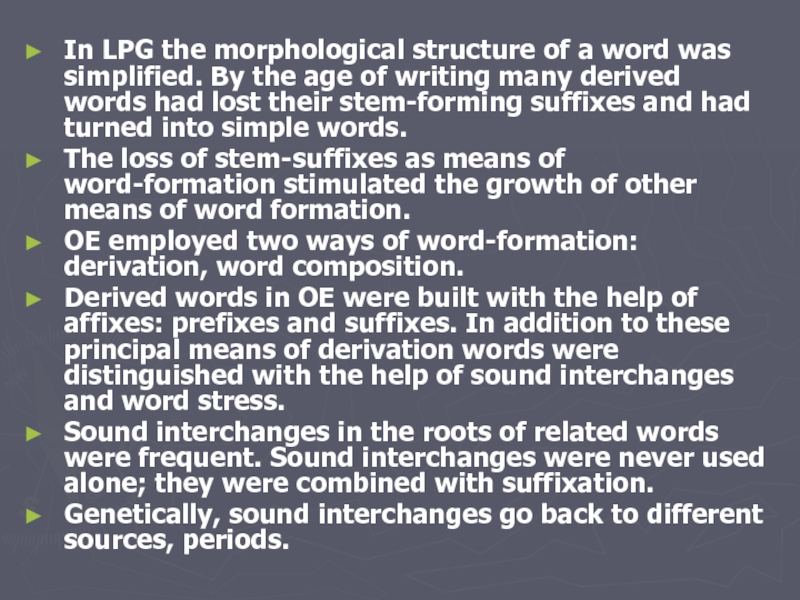

Слайд 25In LPG the morphological structure of a word was simplified. By

the age of writing many derived words had lost their stem-forming suffixes and had turned into simple words.

The loss of stem-suffixes as means of word-formation stimulated the growth of other means of word formation.

OE employed two ways of word-formation: derivation, word composition.

Derived words in OE were built with the help of affixes: prefixes and suffixes. In addition to these principal means of derivation words were distinguished with the help of sound interchanges and word stress.

Sound interchanges in the roots of related words were frequent. Sound interchanges were never used alone; they were combined with suffixation.

Genetically, sound interchanges go back to different sources, periods.