There

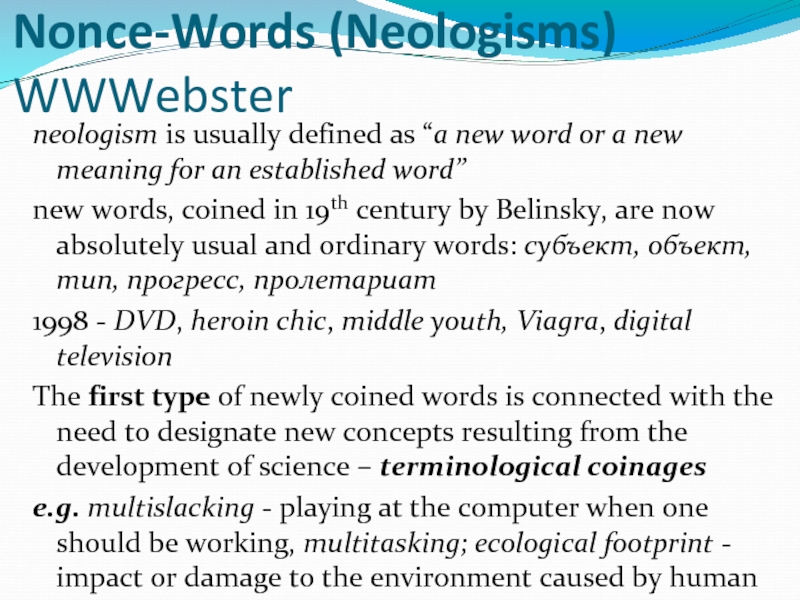

is a term in linguistics which by its very nature is ambiguous and

that is the term neologism. In dictionaries it is generally defined

as * a new word or a new meaning for an established word.!

Everything in this definition is vague. How long should words or

their meanings be regarded as new? Which words of those that

appear as new in the language, say during the life-time of one

generation, can be regarded as established? It is suggestive that the

latest editions of certain dictionaries avoid the use of the

stylistic notation «neologism» apparently because of its

ambiguous character. If a word is fixed in a dictionary and provided

that the dictionary is reliable, it ceases to be a neologism. If a

new meaning is recognized as an element in the semantic structure of

a lexical unit, it ceases to be new. However, if we wish to-divide

the word-stock of a language into chronological periods, we can

conventionally mark off a period which might be called new.

Every

period in the development of a language produces an елог-mous

number of new words or new meanings of established words. Most of

them do not live long. They are not meant to live long. They are, as

it were, coined for use at the moment of speech, and therefore

possess a peculiar property —that of temporariness. The given word

or meaning holds only in the given context and is meant only To

«serve the occasion.»

However,

such is the power of the written language that a word or a meaning

used only to serve the occasion, when once fixed in writing, may

become part and. parcel of the* general vocabulary irrespective of

the quality of the word. That’s why the introduction of new words by

men-of-letters is pregnant with unforeseen consequences: their new

coinages may replace old words and become established in the

language as synonyms and later as substitutes for the old words.

In

this connection it might be noted that such words as субъект,

объект and their derivatives as well as тип, прогресс,

пролетариат and others introduced into the literary

Russian language by V. G. Belinsky have become legitimate4 Russian

words firmly established in the word-stock of the Russian language

and are no longer felt to be alien to the literary language as they

were in4he nineteenth century.

The

coining of new words generally arises first of all with the need to

designate new concepts resulting from the development of science and

also with the need to express nuances of meaning called forth by a

deeper understanding of the nature of the phenomenon in question. It

may also be the result of a search for a more economical, brief and

compact form of utterance which proves to be a more expressive means

of communicating the idea.

The

first type of newly coined words, i. e. those which designate

newborn concepts, may be named terminological coinages. The

secondtype, I. e. words coined because their creators seek expressive

utterance may be named stylisticcoinages.

New

words are mainly coined according to the productive models for

word-building in the given language. But the new words of the

literary-bookish type we are dealing with in this chapter may

sometimes be built with the help of affixes and by other means which

have gone out of use or which are in the process of dying out. In

this case the stylistic effect produced by the means of word-building

chosen becomes more apparent, and the stylistic function of the

device can be felt more acutely.

It

often happens, however, that the sensitive reader finds a new .

application of an already existing word almost revolting. Purists of

all shades rise up in protest against what they call the highly

objectionable and illegitimate usage of the word. But being once

successfully used, it may be repeated by other writers and so may

remain in the language and, moreover, may influence the further

history of the semantic development of the word. V. V.

Vinogradov justly remarks:

«…The

turning point in the semantic history of many words is the new,

vividly expressive, figurative, individual use of them. This new and

genuinely artistic application of a word, if it is in conformity with

the general tendencies of the semantic development of the

language, not infrequently predetermines the further semantic

development of the word.»1

Among

new coinages of a literary-bookish type must be mentioned a

considerable layer of words appearing in the publicistic style,

mainly in newspaper articles and magazines and also in the newspaper

style— mostly in newspaper headlines. To these belongs the word

Blimp — a name coined by Low, the well-known English cartoonist.

The name was coined to designate an English colonel famous for his

conceit, brutality, ‘ultra-conservatism. This word gave birth to a

derivative, viz. Blimpish. Other examples are ‘backlash’ (in

‘backlash policy’) and its opposite ‘frontlash’.

Literary

critics, men-of-letters and linguists, have manifested different

attitudes towards new coinages both literary and colloquial. Ever

since the 16th century, literature has shown example after example of

the losing battle of the purists whose strongest objection to the new

words was on the score of their obscurity. A. A. Baugh points out

that the great exponent of this view was Thomas Wilson. His «Arteof

Rhetor -ique» (1533) was several times reprinted and was used by

Shakespeare.

Of

course, there are different degrees of purism. In other words, the

efforts of scholars to preserve the purity of their language should

not always be regarded*as conservative. They do not looJ< upon any

and every change with suspicion or regard an innovation as invariably

a corruption of the language.

Most

of the new words of the 16th century as well as those of the 17th

were foreign borrowings from Latin, Greek and continental French. The

words were introduced into the English language and used in the

same

sense and with almost the same pronunciation as in the language they

were borrowed from. But most of those which have remained in the

language underwent changes due to the process of assimilation and

were finally «naturalized.» This process is slow. It

sometimes takes centuries to make a word borrowed from another

language sound quite English. The tempo of assimilation is

different with different borrowings, depending in particular on the

language the word is borrowed from. Borrowings from the French

language are easily and quickly assimilated due to long-established

tradition. The process of assimilation plays a rather important role

in the stylistic evaluation of a lexical unit. The greater and the

deeper the process of assimilation, the more general and common the

word becomes, the less bookish it sounds, and the greater the

probability of its becoming a member of the neutral layer of

words.

Throughout

the history of the English literary language, scholars have expressed

their opposition to three main lines of innovation in the vocabulary:

firstly, to borrowings which they considered objectionable

because of their irregularity; secondly, to the revival of archaic

words; and thirdly, because the process of creation of new words.was

too rapid for the literary language to assimilate. The opposition to

one or other of these lines of innovation increased in violence at

different stages in the development of the language, and switched

from one to another in accordance with the general laws of

development in the given

period.

,

We shall refer the reader to books on the history of the English

language for a more detailed analysis of the attitude of purists of

different shades to innovations. Our task here is to trace the

literary, bookish character of coinages and to show which of their

features have contributed to their stylistic labels. Some words have

indeed passed from the literary-bookish layer of the vocabulary where

they first appeared, into the stratum of common literary words and

then into the neutral stratum. Others have remained within the

literary-bookish group of words and have never shown any tendency to

move downwards in the scale.

This

fact is apparently due to the linguistic background of the new words

and also to the demand/or a new unit to express nuances of meaning.

In

our times the same tendency to coin new words is to be observed in

England and particularly in the United States of America. The

literary language is literally inundated with all kinds of new words

and a considerable body of protest has arisen against them. It

is enough to look through some of the articles of the New York Times

on the subject to see what direction the protest against innovations

takes.

Like

earlier periods in the development of the English language, modern

times are characterized by a vigorous protest against the

unrestrained influx of new coinages, whether they have been built in

accordance with the norms of the language, or whether they are of

foreign origin.

«The

danger is not that the reading public would desert good books, but

that abuse of the written language may ruin books.

«As

for words, we are never at a loss; if they do not exist, we invent

them. We carry out purposeful projects in a meaningful manner in

order to achieve insightful experiences.

«We

diarize, we earlirize; any day we may begin to futurize. We also

itinerize, reliablize; and we not only decontaminate and

dehumidifyvbut we debureaucratize and we deinsectize. We are, in

addition, discovering how good and pleasant it is to fellowship with

one another.

«I

can only say, Met us finalize all this nonsense’.»

The

writer of the article then proceeds to give an explanation of the

reasons for such unrestrained coinage. He states that some of the

writers «…are not ashamed of writing badly but rather proud of

writing at all and—with a certain vanity—are attracted by

gorgeous words which give to their slender thoughts an appearance

of power.»

Perhaps

the writer of this article is not far from the truth when he ascribes

literary coinage to the desire to make utterances more pompous and

sensational. It is suggestive that the majority of such coinages are

found in newspaper and magazine articles and, like the articles

themselves, live but a short time. As their effect is

transitory, it must be instantaneous. If a newly-coined word can

serve the demand of the moment, what does it matter to the writer

whether it is a necessary word or not? The freshness of the creation

is its primary and indispensable quality.

The

fate of literary coinages, unlike colloquial ones, mainly depends

on the number of rival synonyms already existing in the vocabulary

of the language. It also depends on the shade of meaning the new

coinage may convey to the mind of the reader. If a new word is

approved of by native speakers and becomes widely used, it ceases to

be a new word and becomes part and parcel of the general vocabulary

in spite of the objections of men-of-letters and other lawgivers of

the language, whoever they may be.

Many

coinages disappear entirely from the language, leaving no mark of

their even brief existence. Other literary neologisms leave traces in

the vocabulary because they are fixed in the literature of their

time. In other words, new literary-bookish coinages will always leave

traces in the language, inasmuch as they appear in writing. This is

not the case with colloquial coinages. These, as we shall see later,

are spontaneous, and due to their linguistic nature, cannot be fixed

unless special care is taken by specialists to preserve them.

Most

of the literary-bookish coinages are built by means of affixation

and word compounding. This is but natural; new words built in this

manner will be immediately perceived because of their unexpectedness.

Unexpectedness in the use of words is the natural device of those

writers who seek to achieve the sensational. It is interesting to

note in passing that conversion, which has become one of the most

productive word-build-

ing

devices of the English language and which is more and more widely

used to form new words in all parts of speech, is less effective in

producing the sensational effect sought by literary coinage than is

the case with other means of word-building. Conversion has become

organic in the .English language.

Semantic

word-building, that is, giving an old word a new meaning, is rarely

employed by writers who coin new words for journalistic purposes.

It is too slow and imperceptible in its growth to produce any kind of

sensational effect.

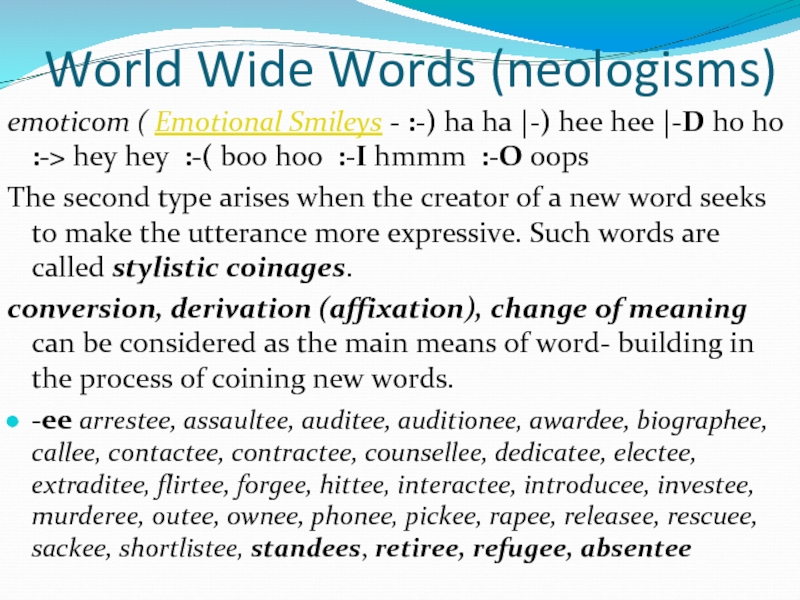

Conversion,

derivation and change of meaning may be registered as means by which

literary-bookish coinages are formed. These three means of

word-building are mostly used to coin new terms in which new

meanings are imposed on old words. Among coinages of this kind

the word accessories may be mentioned. It has now become an important

word in the vocabulary of feminine fashion. It means gloves, shoes

and handbag, though jewellery and other ornaments are sometimes

included. Mary Reifer’s ‘»Dictionary of New Words» notes a

verb to accessorize meaning 4to provide with dress accessories, such

as handbag, gloves, shoes, etc/. These items are supposed to form a

matching or harmonious whole.

The

new meaning co-exists with the old ones. In other words, new meanings

imposed on old words form one system in which old and new meanings

are ranged in a dictionary according to their rate of frequency or to

some other underlying principle. But there are cases when new

meanings imposed oh old words drive out old meanings. In this

case we register a gradual change in the meaning of the word

which may not incorporate the old one. In most cases, however,

the old meaning is hardly felt; it is generally forgotten and can

only be re-established by etymological analysis.

Thus

the word admire,, which, as in Latin, first meant ‘to feel or express

surprise or astonishment’, has today lost its primary meaning and now

has acquired a new one which, however, still contains a shade of the

old, uiz/’td regard with wonder and approval, esteem or affection, to

delight in’.

The

process of elimination of the old meaning, as is seen from this

example, is slow and smooth. Hardly ever can we register a sudden

switch from one meaning to another: there is always a gradual

transition, and not infrequently J;he two competing meanings

co-exist, manifesting in this co-existence ^an almost imperceptible

internal struggle which ends in the complete elimination of one of

them.

Almost

half of the words in’ihe 18th century «English Dictionary»

compiled by Samuel Johnson may serve as examples of change of

meaning. A word or two taken at random will confirm the

statement just made.

The

word to fascinate meant ‘to bewitch’; ‘to enchant’; ‘to influence

in some wicked and secret manner’. The word available is explained

in Johnson’s Dictionary as «1. Profitable; Advantageous. 2.

Powerful, in force.»

True,

in some respects Johnson’s Dictionary cannot be regarded as a

reliable source of information: his attitude towards colloquial idiom

is

well known. It was not only aversion—it was a manifestation of his

theoretical viewpoint. James Boswell in his «Life of Johnson»

says that the compiler of the dictionary was at all times jealous of

infractions upon the genuine English language, and prompt to repress

what he called colloquial barbarisms; such as pledging myself for

‘undertaking’, line for ‘department’ or Branch’, as the civil line,

the-banking line. He was particularly indignant against the almost

universal use of the word idea in the sense of ‘notion’ or ‘opinion’,

when it is clear that idea, being derived from the Greek word meaning

‘to see’, can t>nly signify something of which an image can be

formed in the mind. We may have, he says, an idea or image of a

mountain, a tree, a building; but we cannot surely have an idea or

image of an argument or proposition.

As

has been pointed out, word-building by means of affixation is still

predominant in coining new words. Examples are: arbiter—’a

spacecraft designed to orbit a celestial body’; lander—’a

spacecraft designed to land on such a body’; missileer—’a person

skilled in missilery or in the launching and control of missiles’;

fruitologist and wreckologist which were used in a letter to the

editor of The times from a person living in Australia. Another

monster of the ink-horn type is the word overdichotomize—’to split

something into too many parts’, which is commented upon in an article

in New York Times Magazine:

«It

is, alas, too much to expect that this fine flower of language,

a veritable hot-house specimen—combining as it does a vogue word

with a vogue suffix—will long survive.»*

The

literary-bookish character of such coinages is quite apparent and

needs no comment. They are always felt to be over-literary because

either the stem or the affix (or both) is not used in the way the

reader expects it to be used. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to

say that by forcibly putting together a familiar stem and a familiar

affix and thus producing an unfamiliar word, the writer compels the

reader to concentrate his attention on the new word, firstly by its

novelty and secondly by the necessity of analysing it in order

to .decipher the message. By using a neologism instead of the word or

combination of words expected, he violates the main property of

a communication, which is to convey the idea straightforwardly and

promptly.

Among

new creations those with the suffix -ize seem to be the most

i;frequent. The suffix -ize gives a strong shade of bookishness to

new fwords. Here are some more examples of neologisms with this

suffix:

‘detribal/3Јd

(Africans)’; ‘accessor/^’; »moisturize’; ‘villagize’.

Thomas

Pyles writes:

«The*-ize

suffix… is very voguish in advertizing copy, a most potent

disseminator of modish expressions; …its fashionableness may

explain why ‘hospitalize’, current since the turn of the century, has

recently begun to flourish.»

Some

affixes are themselves literary in character and naturally carry this

property to derivatives formed with them. Thus, for example, the

prefix anti- has given us a number of new words which are gradually

becoming recognizable as facts of the English vocabulary, e. g.

‘ялй-novelist’,

‘on/i-hero’, ‘шг/t-world’, ‘шгЯ-emotion’, ‘anti-trend’ and the

like.

The

prefix anti-, as is seen from these examples, has developed a new

meaning. It is rather difficult to specify. In the most general terms

it may be defined as ‘the reverse of. In this connection it will be

interesting to quote the words of an English journalist and

essayist.

«The

spirit of opposition is as necessary as the presence of rules and

disciplines, but unlimited kicking over traces can become a tedious

exercise. So can this popular business of being ‘anti’ in general. In

the world of letters the critical lingo of our time speaks of the *

anti-novel’ or * anti-play’ which has an ‘anti-hero’. Since there is

a fashion for characters unable to communicate, people with nothing

to say and no vocabulary with which to explain their vacuity,

‘anti-writing’ may fairly be described as possessing

‘anti-dialogue’.»

The

suffix -dom has also developed a new meaning, as in ‘gangdom’,

‘freckledom’, ‘musicdo/n’ where the suffix is used with the most

general meaning of collectivity. The suffix -ее has been given new

life. We have’ interrogate’, ‘autobiography’ («…the

pseudo-autobiographer has swallowed the autobiographee whole.»

New Statesman, Nov. 29,1963); ‘enrolls’ («Each enrollee is given

a booklet filled with advice and suggestions, and attends the

lecture…» New York Times Magazine, Jan. 26, 1964); ‘omittee’,

‘askee’ («That’s a bad habit, asking a question and not waiting

for an answer, but it’s not always bad for the askee.» — Rex

Stout, «Too many clients») — ^ .; —

The

suffix -ship has also developed a new shade of meaning which is now

gaining literary recognition, as in the coinages:

‘showmans/up’,

‘brinkmans/up’, ‘lifemans/u’p’, ‘lipmans/u’pV ‘mistress mans/up’,

‘sugermans/i/p’, ‘ one-up mans/up’, etc.

In

these coinages» ад interesting phenomenon seems to be taking

place. The word man is gradually growing first into a half-suffix and

finally into part of the complex-suffix -manship with the approximate

meaning ‘the ability to do something better than another person’.

Among

voguish suffixes which colour new coinages with a shade of

bookishness is the suffix -ese, the dictionary definition of which is

«1) belonging to a city or country as inhabitant (inhabitants)

or language, e. g. Genoese, Chinese; 2) pertaining to a

particular writer (of style or diction), e. g. Johnsonese,

journalese.»

Modern

examples are:

‘Daily-Telegraphese’,

‘New Yorkese’; recently a new word has appeared— ‘TV-ese’. It is

the novelty of these creations that attracts our attention

and

it is the unexpectedness of the combination that makes us feel that

the new coinage is of a bookish character.

The

resistance of purists to the unrestrained flow of new coinages of a

bookish character, which greatly outnumbers the natural colloquial

creations, can be illustrated in the following words of Robert E.

Morseberger:

«Anyone

familiar with the current crop of horror movies knows that weird

mutations caused by atomic radiation have spawned a brood of

malignant monsters, from giant insects (half human and otherwise) to

blobs of glup. While these fortunately are confined to science

fiction, our language itself demonstrates similar grotesque mutations

in truncated, telescoped words and words with extra inflationary

growths on the suffix end, not counting the jargon of special groups

from beatniks to sociologists.

«Among

the more frequent and absurd of these linguistic monsters are

condensed words ending in -ratna and -thon. The former comes from

panorama from the Greek pan (== all) plus horama (= a view) or

cyclorama from the Greek kyklos (= а circle) plus horama again. So

far so good; the next development is cinerama, still sound, from the

Greek kinema (= motion) and our old friend horama.

«Now

the advertisers have taken the suffix-root and proceed to torture it

out of sense and recognition, with horama (or rather a vowel followed

by -rama) no longer meaning simply a view but an entire spectacle or

simply a superlative, so that the suffix has devoured all the

original panorama in such distortions as cleanorama (= a spectacular

cleaning spree); tomatorama, beana-rama, bananarama (= a sensational

sale of tomatoes, beans or bananas)…

«Keeping

pace with -rama (pacerama) is -thon, a suffix newly minted from

ancient metal. Pheidippides’ race from the battlefield of

Marathon and the later foot race of that name gave the noun Marathon

the meaning of an endurance contest; but we now have to endure -thon

alone, divorced, and made into a self-sustaining suffix in (sobl)

such words as telethon, walkathon, talkathon, danceathon, cleanathon,

… Clearly -thon and -rama compete in the rivalry between cleanathon

and cleanorama’, both bastard suffixes have swallowed their original

noun, and it is only logical that they should next swallow each other

in * thonorama’ (= an endurance of various -ramas) or ramathon (= a

panoramic or sensational endurance contest).1

The

reader will undoubtedly not fail to observe that the protest against

these «ink-horn» terms is not based on any sound linguistic

foundation. It merely shows the attitude of the writer towards

certain novelties in language. They seem to him monstrous. But there

is no indication as to what makes them monstrous. The writer himself

readily uses new words such asglup, beatniks without quotation marks,

which shows, evidently, that he is reconciled to them. Strugglesome,

informatative, connotate, unworthwhile, inferiorism, deride, to be

accusated are other words which he apparently considers distortions.

The last string of literary coinages is supplied with the following

footnote: «All words used in this sentence are gratefully

acknowledged as coming from college freshman themes.»

Unfortunately

there are no objective criteria for ascertaining the stylistic aspect

of words. Therefore the protest of many language purists is sometimes

based on subjective idiosyncrasy. We find objections to the ways and

means of coining new words, as in the quotation above, and also to

the unrestrained injection into some words of emotive meaning when

this meaning, it is said, has not yet been widely recognized, as top

(— excellent, wonderful), fey (= somewhat whimsical, in touch with

the supernatural, a little cracked).1 This second objection applies

particularly to the colloquial stratum of words. We also find

objections to the new logical meanings forced upon words, as is done

by a certain J. Bell in an article on advertizing agencies.

«Highly

literate men are busy selling cancer and alcoholism to the public,

commending inferior goods, garbling facts, confusing figures,

exploiting emotions…»

Here

the word sell is used in the sense of * establishing confidence in

something, of speaking convincingly, of persuading the public to do,

or buy and use something’ (in this case cigarettes, wine and

spirits); the word commend has developed the meaning of ‘recommend’

and the word inferior has come to mean * lower in price, cheap’; to

garble, the primary meaning of which is ‘to sort by sifting’, now

also means ‘to distort in order to mislead’; to confuse is generally

used in the sense of ‘to mix up in mind’, to exploit emotions means

‘making use of people’s emotions for the sake of gain’.

All

these words have acquired new meanings because they are used in

combinations not yet registered in the language-as-a-system. It is a

well-known fact that any word, if placed in a strange environment,

will inevitably acquire a new shade of meaning. Not to see this,

means not to correctly evaluate the inner laws of the semantic

development of lexical units.

There

is still another means of word-building in modern English which may

be considered voguish at the present time, and that is the blending

of two words into one by curtailing the end of the first component

or the beginning of the second. Examples are numerous: musico-medy

(music+comedy); cinemactress (cinema+actress); avigation

(avia-tion+navigation); and the already recognized blends like smog-

(smoke+ fog); chortle (chuckle+snort); galumph (triumph+gallop) (both

occur in Humpty Dumpty’s poem in Lewis Carroll’s «Through the

Looking Glass»). Arockoon (focket+balloon) is ‘a rocket designed

to be launched from a balloon’. Such words are called blends

In

reviewing the ways and means of coining new words, we must not

overlook one which plays a conspicuous role in changing the meaning

of words and mostly concerns stylistics. We mean injecting into

well-known, commonly-used words with clear-cut concrete meanings, a

meaning that the word did not have before. This is generally due to

the combinative power of the word. This aspect of words has long been

underestimated by linguists. Pairing words which hitherto have

not been paired, makes the components of the word-combinations

acquire a new, and sometimes quite unexpected, meaning. Particularly

productive is the adjective. It tends to acquire an emotive meaning

alongside its logical meaning, as, for instance, terrible, awful,

dramatic, top.

The

result is that an adjective of this kind becomes an intensifies it

merely indicates the degree of the positive or negative quality of

the concept embodied in the word that follows. When it becomes

generally accepted,.it becomes part of the semantic structure of the

word, and in this way the semantic wealth of the vocabulary

increases. True, this process is mostly found in the domain of

conversation. In conversation an unexpectedly free use of words is

constantly made. It is in conversation that such words as stunning,

grand, colossal, wonderful, exciting and the like have acquired this

intensifying derivative meaning which we call emotive.x But the

literary-bookish language, in quest of new means of impressing the

reader, also resorts to this means of word coinage. It is mostly the

product of newspaper language, where the necessity, nay, the urge, to

discover new means of impressing the reader is greatest.

In

this connection it is interesting to quote articles from English and

American periodicals in which problems of language in its functional

aspect are occasionally discussed. In one of them, «Current

Cliches and Solecisms» by Edmund Wilson,2 the improper

application of the primary and accepted meanings of the words

massive, crucial, transpire and others is condemned. The author of

the article is unwilling to acknowledge the objective development of

the word-stock and instead of fixing the new meanings that are

gaining ground in the semantic structure of these words, he tries to

block them from literary usage while ..neglecting the fact that these

new meanings have already been established in the language. This

is what he says:

«Massive!

I have also written before of this stupid and oppressive word, which

seems to have become since then even more common as a ready cliche

that acts as a blackout on thinking. One now meets it in every

department: literary, political, scientific. In a period of moral

impotence, so many things are thought as intimidating that they are

euphemistically referred to as massive. I shall not present further

examples except to register a feeling of horror at finding this

adjective resorted to three times, and twice in the same paragraph,

by Lionel! Trilling in Commentary, in the course of an otherwise

admirable discussion of the Leavis—Snow controversy: massive

signi

fwance

of «The Two Cultures», massive intention of «The Two

Cultures», quite massive blunder of Snow in regard to the

Victorian writers. Was Snow’s essay really that huge and

weighty? If it was, perhaps it might follow that any blunder in it

must also be massive.»

Another

of these emotional intensifiers is the word crucial. It also raises

objections on the part of purists and among them the one whose

article we are quoting. «This word,» writes Edmund Wilson,

«which means properly decisive, critical, has come to be used,

and used constantly, in writing as well as in conversation as if it

meant merely important… ‘But what is crucial, of course, is that

these books aren’t very good…*.’Of course it is of crucial

importance’.»

Another

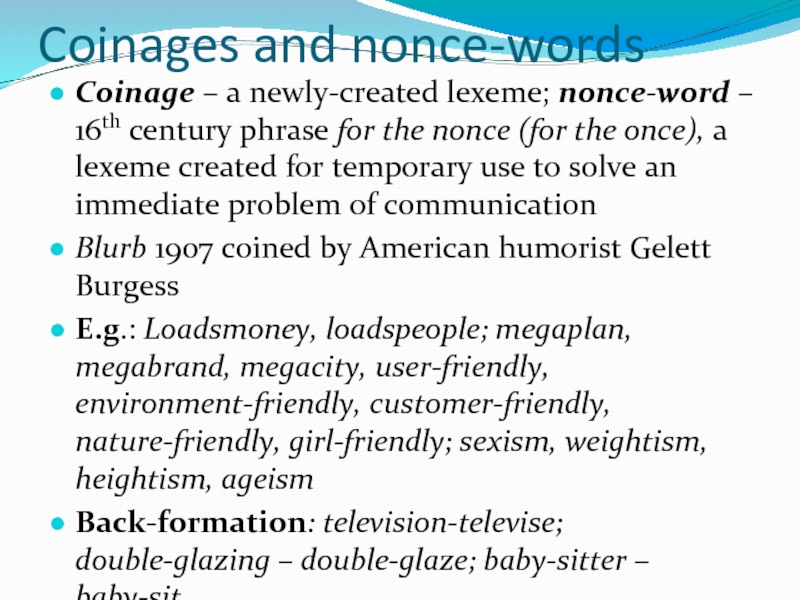

type of neologism is the nonce-word, i.e. a word coined to suit one

particular occasion. Nonce-words remain on the outskirts of the

literary language and not infrequently remind us of the writers who

coined them. They are created to designate some insignificant

subjective idea or evaluation of a thing or phenomenon and generally

become moribund. They rarely pass into the language as legitimate

units of the vocabulary, but they remain in the language as constant

manifestations of its innate power of word-building.

Here

are some of these neologisms which, by the way, have the right to be

called so because they will always remain neologisms, i. e. will

never lose their novelty:

«Let

me say in the beginning that even if I wanted to avoid Texas I could

not, for I am wived in Texas, and mother-in-lawed, and uncled, and

aunted, and cousined within an inch of my life.»

(J.

Steinbeck)

The

past participles mother-in-lawed, uncled, aunted and cousined are

coined for the occasion on the analogy of wived and can hardly be

expected to be registered by English dictionaries as ordinary

English words.

Here

are some more examples of nonce-words, which strike us by their

novelty, force and aesthetic aspect.

«There

is something profoundly horrifying in this immense, indefinite

not-thereness of the Mexican scene.» (Huxley)

«You’re

the bestest good one—she said—the most bestest good one in the

worldT:»v(H. Ё.* Bates)

«That

was masterly. Or should one say mistressly» (Huxley)

«Surface

knowingness» (J-. Updike); «sevenish» (around seven

o’clock); «morish» (a little more) (A. Christie).

In

modern English new words are also coined by a means which is very

productive in technical literature and therefore is mostly found in

scientific style, viz. by contractions and abbreviations. But

this means is sometimes resorted to for stylistic purposes. Here are

some of these coinages which appear daily in different spheres

of human activity.

TRUD

(=time remaining until dive). The first letters of this word sequence

forms the neologism TRUD which will presumably remain as

a

professional term unknown to wider circles of native English

speakers. Such also are the words LOX (= 1. liquid oxygen explosive,

2. liquid oxygen) and GOX (= gaseous oxygen). To the layman, oxygen

is a gas, but in missilery (also anew word) it is more often a liquid

or even a solid, so gaseous oxygen has to be distinguished. Other

better-known examples are laser (= light amplification by stimulated

emission of radiation);

.

Unesco (United Nations Education and Science Organization); jeep

(GP=General Purpose car).

Not

all of the means of word coinage existing in the English language

have been dealt with in this short survey. The reason for this is

simple: in stylistics there are ways and means of producing an effect

which attract the attention of the reader not only by the novelty of

a coinage but by a more elaborate language effect. This effect must

be specified to make clear the intentions of the writer. The writer

in this case is seeking something that will adequately convey

his idea to the mind of the reader. The means assume some additional

force: novelty+force.

Therefore

in the survey of the means of word-formation only those have been

selected which provide novelty+force.

The

stylistic effect achieved by newly-coined words generally rests on

the ability of the mind to perceive novelty at the background of the

familiar. The sharper the contrast, the more obvious the effect. The

slight, almost imperceptible changes caused by extensions of an

original meaning might well produce a stylistic effect only when the

reader is well versed in discriminating nuances of meaning.

Thus

the use of the words commitment and commit in the meaning of

‘involvement’ and ‘involve’ has imperceptibly crept into common use

since approximately 1955 and is now freely used. So also are the use

of unfortunately instead of ‘regretfully’, the use of dramatic and

massive as intensifiers. Such changes are apparent only to the eye of

the lexicographer and will hardly provoke a twofold application

of meaning, unless, of course, the context forcibly points to such an

application.

However,

these words will ordinarily carry an expressive function due to their

emotive meaning.

When

we tackle the problem of SDs and penetrate more deeply into its

essence, it becomes apparent that stylistic function is not confined

to

t

phenomena which are foregrounded, as newly-coined words generally

are. A stylistic effect may also be achieved by the skilful interplay

of a long-established meaning and one just being introduced into the

lan-guage-as-a-system.

к

Thus the word deliver in the United States has acquired the

meaning

|л

‘to carry out or fulfil an expectation; make good’ (Barnhart

Dictionary).

|

If this word were to carry its original meaning alongside the one now

I

.current in the U. S. it would produce a stylistic effect, if, of

course, this twofold application of the word is done deliberately.

Novelty is not a device. One must distinguish between a deliberate,

conscious employment

v

of the inherent property of words to be used in different meanings

simultaneously and the introduction of a new meaning which in

the given context excludes the one from which it is derived.

In

the following examples taken from the Barnhart Dictionary the

italicized

words do not display any twofold meanings, although they are

illustrative of the new meanings these words have acquired.

«…he

has spent hours reading government cables, memoranda and classified

files to brief himself for in-depth discussions.»

*In-depthT,

adj. means ‘going deeply, thoroughly into a subject’.

«Bullit,

I find, is completely typical of the ‘now’ look in American

movies — a swift-moving, constantly shifting surface that suggests

rather than reveals depth.»

The

word now as an adjective is a novelty. Barnhart labels it slang—

«very fashionable or up-to-date; belonging to the Now

Generation.»

And

still the novelty can be used for stylistic purposes provided that

the requirements for an SD indicated earlier are observed. It must be

repeated that newly-minted words are especially striking. They check

the easy flow of verbal sequences and force our mind to take in the

referential meaning. The aesthetic effect in this case will be

equal to zero if the neologism designates a new notion resulting from

scientific and technical investigations. The intellectual will

suppress the emotional. However, coinages which aim at introducing

additional meanings as a result of an aesthetic re-evaluation of the

given concept may perform the function of a stylistic device.

ООО Учебный центр

«ПРОФЕССИОНАЛ»

Статья-реферат

По теме:

«Стилистическая дифференциация лексики»

“Stylistic Differentiation of the Vocabulary”

Исполнитель:

Малютина Ольга Владимировна

Москва 2021 год

Content

1. Introduction. AN OUTLINE OF STYLE

CLASSIFICATIONS

2.

SOCIALLY

REGULATED SUBLANGUAGES

3.

THE COLLOQUIAL

SPHERE

4.

Stylistic

Differentiation of the English Vocabulary

·

The literary

vocabulary

·

The colloquial

vocabulary

·

Neutral words

·

Common standard colloquial

words

·

Special

colloquial vocabulary

5. Conclusion

1.

Introduction

AN

OUTLINE OF STYLE CLASSIFICATIONS

The main aim

of the report is to give a detailed description of linguistic styles and

stylistic differentiation of the vocabulary. As these two aspects are closely

connected it helps learners to distinguish both of them.

Starting a

report on a style differentiation of the vocabulary, it is necessary to

introduce a short outline of style classifications as an essential part of

linguistic sphere connected with lexicology.

First, the

books by I.R. Galperin, both reliable sources of detailed stylistic information.1

Galperin distinguishes five styles in present-day English. They are:

I.

Belles

Lettres

1.

Poetry

2.

Emotive

Prose

3.

The

Drama

II.

Publicistic

Style

1.

Oratory

and Speeches

2.

The

Essay

3.

Articles

III.

Newspapers

1.

Brief

News Items

2.

Headlines

3.

Advertisements

and Announcements

4.

The

Editorial

IV.

Scientific

Prose

V.

Official

Documents

The varieties

enumerated certainly differ from one another, which is shown by the abundance

of illustrations discussed. What prevented him from including a Colloquial

Style was explained above (see Introduction).

There is one

more point that calls for discussion: the validity of postulating a

Belles-Lettres Style. It may in fact be assumed that Galperin’s position is not shared by most of

those interested in style matters. The diversity of what is actually met with

in books of fiction turns the notion of a belles-lettres style into something

very vague. In modern realistic prose the reader also comes across emotionally

coloured passages of text that tend to use image-creating devices — tropes and

figures of speech. Such passages are, as a general rule, the author’s

narrative, especially expositions, lyrical digressions, philosophical

descriptions of landscape or the mental state of a character. We can encounter

practically every speech type imaginable in books of fiction, whose authors’

guiding principle is being true to life.

Next comes the well-known

work by I.V. Arnold Stylistics of Modern English (two editions: 1973 and,

thoroughly revised, 1981).5 LV. Arnold singles out four styles:

1. Poetic style

2. Scientific style

3. Newspaper style

4. Colloquial style

What speaks in favour of

LV. Arnold’s concept is that she recognises a colloquial style. Singling out a

poetic and a scientific style seems valid. Arnold overlooks a very important style-forming sphere: that

of official intercourse — business correspondence, legal documents, municipal

announcements and the like.

Very rich in information,

with a number of new problems raised and solved, is the handbook by A.N.

Morokhovsky “Stylistics of the English Language”, published in Kiev. The problem

of styles is to be settled ends with the following set of style classes:

1. Official business

style

2. Scientific-professional

style

3. Publicistic style

4. Literary colloquial

style

5. Familiar colloquial

style

A.N. Morokhovsky warns

the reader that the five classes of what he calls ‘speech activity’ are

abstractions, rather than realities, and can only seldom be observed in their

pure forms: mixing styles is the prevailing practice.

Summing up, we shall have

to state that logical infallibility is combined here with insufficient

informative force: it is the general principle that Dolinin intends to

demonstrate (entirely succeeding); only a few concrete speech types and styles

are mentioned. Dolinin’s main concern is to show the validity and applicability

of the scheme; as for attempting to calculate what is incalculable by its very

nature, K. A. Dolinin is too sagacious a scholar to engage in hopeless affairs.

We shall review, finally,

one more well-known book: M.N. Kozhina’s Stylistics of the Russian Language22

raises a considerable number of problems, to discuss which would take up too

much space. M.N. Kozhina

lists type-forming and socially significant spheres of communication as

follows: 1) official; 2) scientific; 3) artistic; 4) publicistic; 5) of daily

intercourse (= colloquial).

From the discussion of

classifications reviewed above, we should draw certain conclusions. No

classification whatever can be exhaustive, universally applicable, and

reflecting the innumerable relationships between common features and

distinctions of all text types. The smaller the classes after segmenting the

whole, the less practicable and logically reliable the result is bound to be.

On the contrary, the division into smaller numbers diminishes the explanatory

force of the procedure, but secures more definite results.

2. SOCIALLY

REGULATED SUBLANGUAGES

The use of the

sublanguage fettered by formality is as wide as any other, since it is up to us

what we regard as formal. There certainly are degrees of formality. Both the

Charter of the United Nations (1945) and a business letter signed by a

low-ranking official are formal, i.e. as the meaning of the adjective formal

necessarily implies devoid of any indication of private emotions (except when

the subject is directly connected with emotions — say, in congratulations and

condolences) and — what is perhaps of greater importance, or at least, quite

indispensable — devoid of any trace of familiarity.

A very rough and

approximate gradation of sub-spheres and their respective sublanguages follows:

a) private correspondence

with a stranger;

,b) business,

correspondence between representatives of commercial or other establishments;

c) diplomatic

correspondence, international treaties, other documents;

d) legal documents (civil

law — testaments, settlements, etc.; criminal law — verdicts, sentences, etc.);

e) personal documents

(certificates, diplomas, etc.).

This is the sphere of written lingual

intercourse, although texts of some of the types are read aloud in public.

Common to the genres enumerated is:

1. ‘Superneutral’ features of

this whole group of sublanguages.

2. Socially established (as

opposed to free creative) character, which, as alluded to before, may be

collectively referred to as archaic, i.e. either obsolete or obsolescent.

3. Predetermined lingual form

(in all the genres mentioned, though the degree is, of necessity, different).

4. Cliches (different genres

have stereotyped expressions of their own).

5. Long (polysyllabic) words of

Latin or Greek origin, often euphemistic as compared with their counterparts.

6. Periphrastic expressions

where a single word might have done just as well.

7. Complex syntax as compared to

that of commonly bookish texts.

8. Established forms of

composition that cannot be deviated from; they naturally differ in each genre

discussed below.

3. THE COLLOQUIAL SPHERE

The term colloquial is widely used by

stylists (although I.R. Galperin, as we remember, rejected outright both the

term and the notion for having in his opinion, nothing in common with what he

understood by stylistics).

By colloquial we mean what is only

slightly lower than neutral — such forms of speech in fact as are used by

people when they do not mean to be rude, sarcastic or witty, when they do not

think of how they should express themselves, only of what they intend to say.

To put it another way: our speech usually becomes colloquial (i.e. with a tinge

of familiarity, relaxed without being offensive) when we feel at ease, when we

do not keep in our minds our social obligations and conventions. Talking with

our friends, we do not even notice the forms of the sublanguage we employ, but

as soon as a stranger appears, especially our superior, a person we esteem, we

usually drop our slack and lazy manner of speaking, we avoid colloquial forms,

switching over to another «wavelength», and use preferably neutral

and super neutral (literary) forms. The colloquial stratum is followed by a

lower one comprising jargon, slang, and nonce creations.

It must be borne in mind that the

term ‘colloquial speech’ is applied by researchers to careless, unconventional,

free-and-easy everyday speech of only those who are well educated and can speak

‘correct’ literary English perfectly well, whenever it is necessary. Just as in

this country, uneducated or semi-educated speakers understand the literary

language, but cannot actively use it themselves, making inadmissible mistakes,

mostly in pronunciation, often

in grammar and in choice of words. Hence, what they use is not colloquial

English, but just incorrect English.

The principal and practically the

only absolutely relevant feature of the colloquial sphere of speech is absence of

any definite stylistic purpose as a result of the informality of the

communicative situation.

Just as in the case of vocabulary

(see Chapter on Lexicology of Units), where every non-neutral manifestation was

to be regarded as either ‘better’ (‘higher’) than neutral, or ‘worse’ (‘lower’)

than neutral, the primary division of the bulk of specific features (not only

with reference to the colloquial sublanguage, but here it manifests itself in a

most visual way!) is into ‘overstatement’ and ‘understatement’, ‘redundance’

and ‘lack’, ‘saying too much’ or ‘saying too little’ as compared to what should

be done in the neutral sphere. The two tendencies, opposite but dialectically

interwoven, are what is called below ‘Explication’ and ‘Implication’.

4. Stylistic Differentiation of the

English Vocabulary

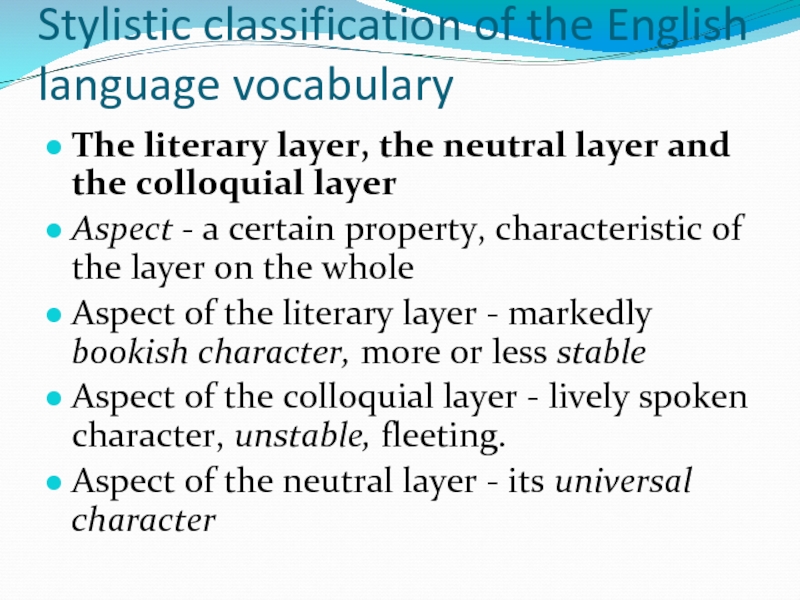

The word-stock of any language may be

presented as a system, the elements of which are interconnected, interrelated

and yet independent. Then the word-stock of the English language may be divided

into three main layers (strata): the literary layer (stratum), the neutral

layer, and the colloquial layer. The literary and the colloquial layers contain

a number of subgroups. Each subgroup has a property it shares with all the

subgroups within the layer.

The classification given by

I.R.Galperin reflects to a great extent the mobility of the lexical system so characteristic

of the English language at its present stage of development. The vocabulary has

been divided here into two basic groups: standard and non-standard vocabulary.

The literary vocabulary consists of the following groups of

words:

1.common literary;

2.terms and learned words;

3.poetic words;

4.archaic words;

5.barbarisms and foreign words;

6.literary coinages and nonce-words.

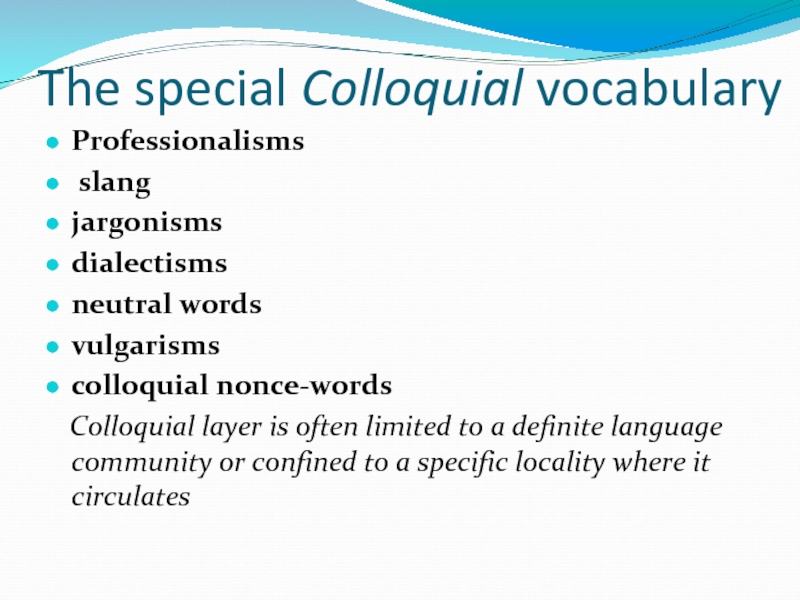

The colloquial vocabulary includes the following groups of

words:

1.common colloquial words;

2.slang;

3.jargonisms;

4.professionalisms;

5.dialectal words;

6.vulgar words;

7.colloquial coinages.

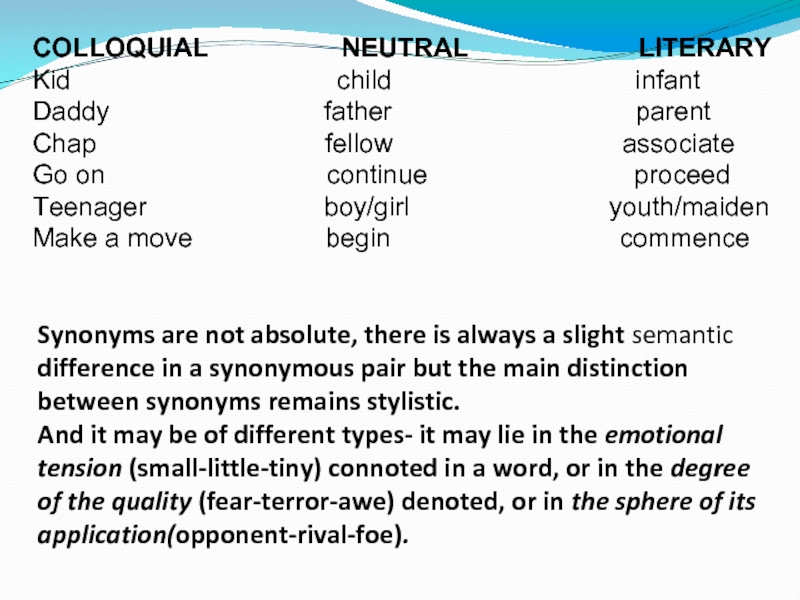

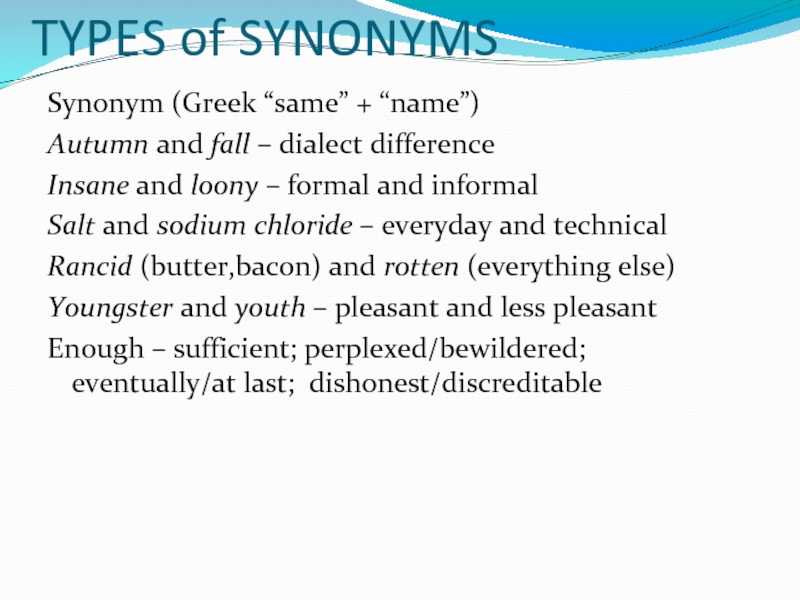

The common literary, neutral and

common colloquial words are grouped under the term Standard English Vocabulary.

Other groups in the literary and colloquial layers are called special literary

(bookish) vocabulary and special (non-standard) colloquial vocabulary.

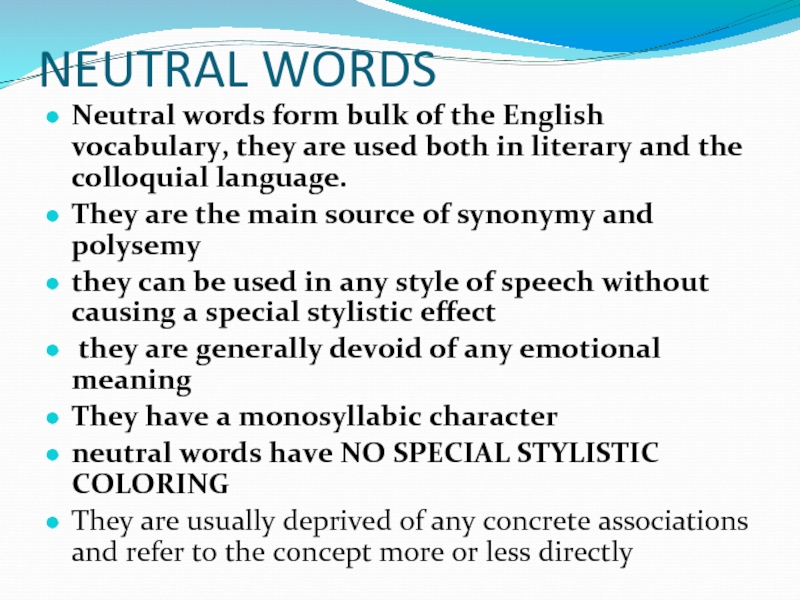

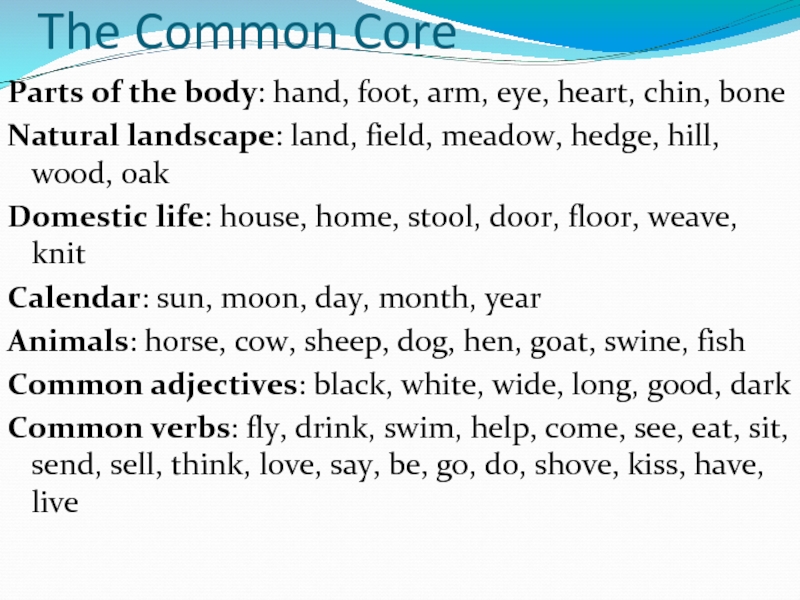

Neutral words form the bulk of the English

Vocabulary and are used in both literary and colloquial language. Neutral words

are the main source of synonymy and polysemy. Unlike all other groups, neutral

words don’t have a special stylistic colouring and are devoid of emotional

meaning.

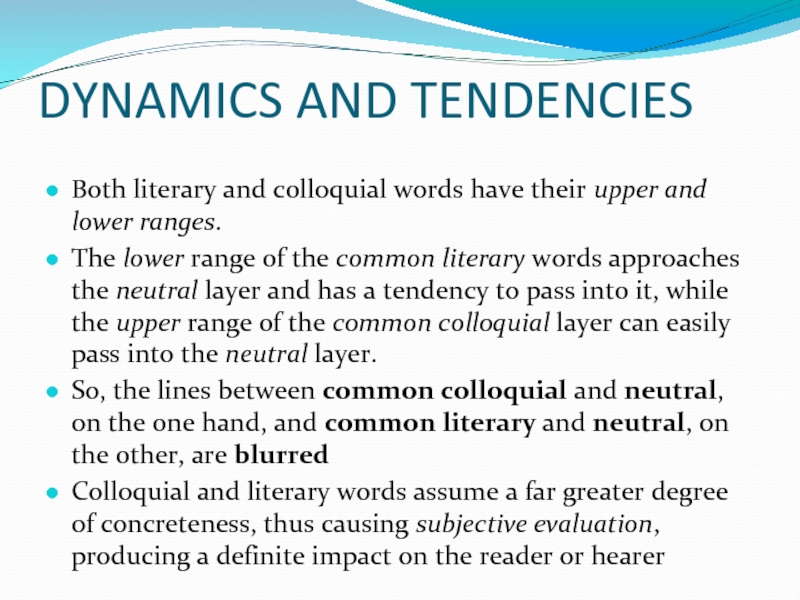

Common standard colloquial words

Common colloquial words are always

more emotionally coloured than literary ones. They are used in informal

communication. Both literary and colloquial words have their upper and lower

ranges. The lower range of literary words approaches the neutral layer and has

a tendency to pass into that layer. The upper range of the colloquial layer can

easily pass into the neutral layer too. The lines of demarcation between common

colloquial and neutral and common literary and neutral are blurred. Here we may

see the process of interpenetration of the stylistic layers. The stylistic

function of the different layers of the English Vocabulary depends in many

respects on their interaction when they are opposed to one another. It is

interesting to note that anything written assumes a greater degree of

significance than what is only spoken. If the spoken takes the place of the

written or vice versa, it means that we are faced with a stylistic device.

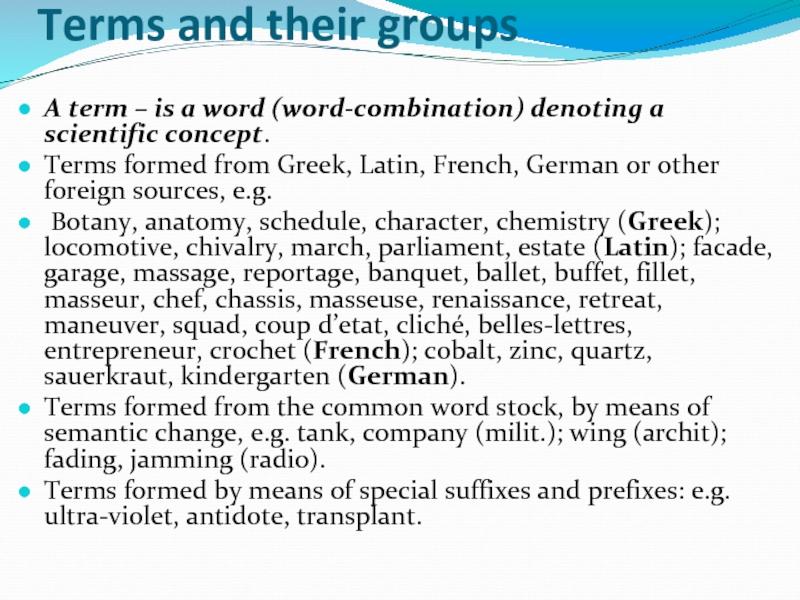

Specific literary vocabulary

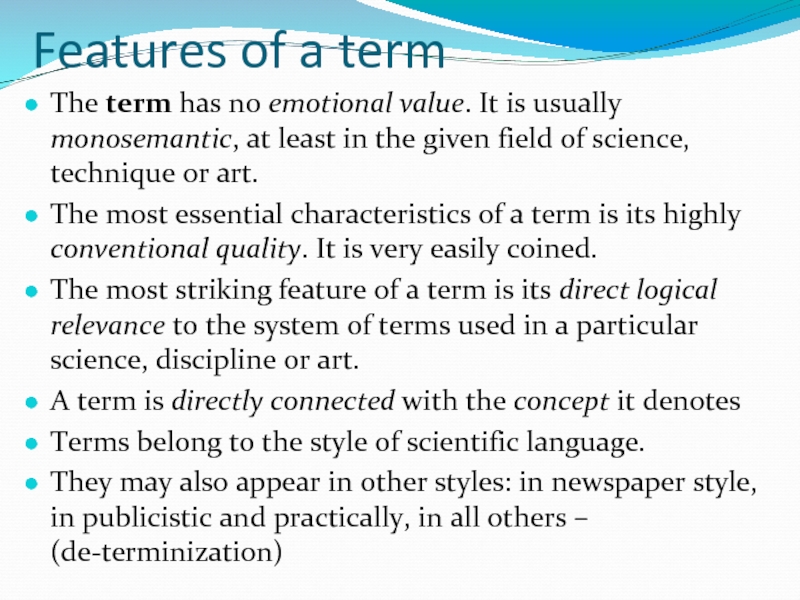

a) Terms. Terms are

generally associated with a definite branch of science and therefore with a

series of other terms belonging to that particular branch of science. They know

no isolation; they always come in clusters, either in a text on the subject to

which they belong, or in special dictionaries which, unlike general

dictionaries, make a careful selection of terms. Terms may appear in scientific

style, newspaper style, publicistic style, the belles-lettres style, etc. Terms

no longer fulfill their basic function, that of bearing an exact reference to a

given notion or concept. Their function is either to indicate the technical

peculiarities of the subject dealt with, or to make some references to the

occupation of a character whose language would naturally contain special words

and expressions.

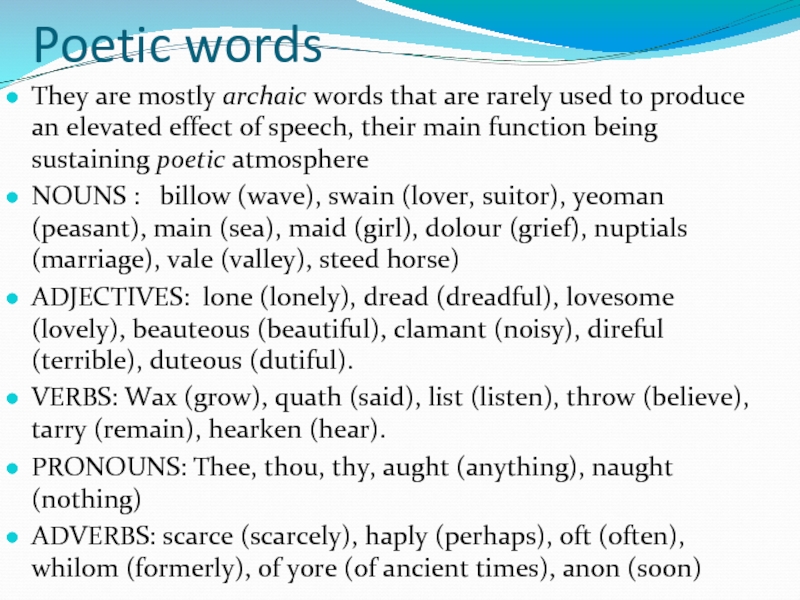

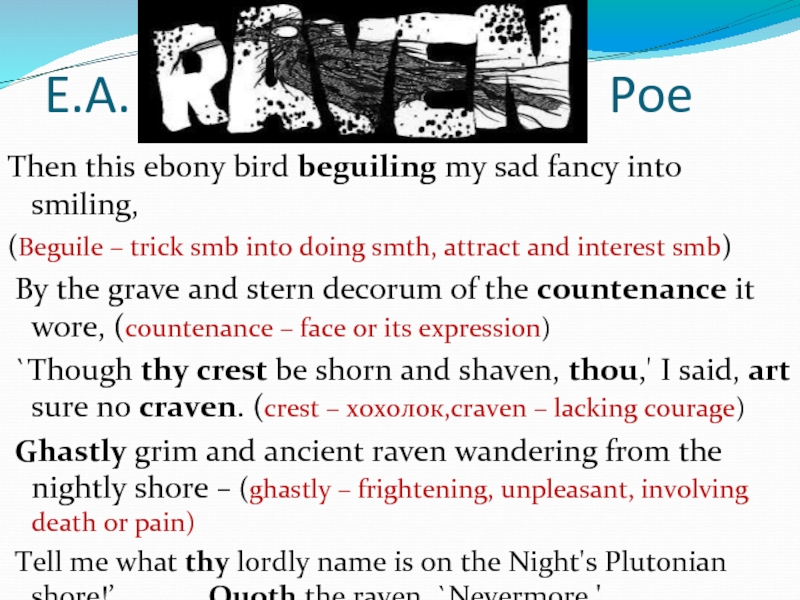

b) Poetic and highly literary

words. First of all poetic words belong to a definite style of language

and perform in it their direct function. If encountered in another style of

speech, they assume a new function, mainly satirical, for the two notions,

poetry and prose, have been opposed to each other from time immemorial. Poetic

language has special means of communication, i.e. rhythmical arrangement, some

syntactical peculiarities and certain number of special words. The specific

poetic vocabulary has a marked tendency to detach itself from the common

literary word stock and assume a special significance. Poetic words claim to

be, as it were, of higher rank.

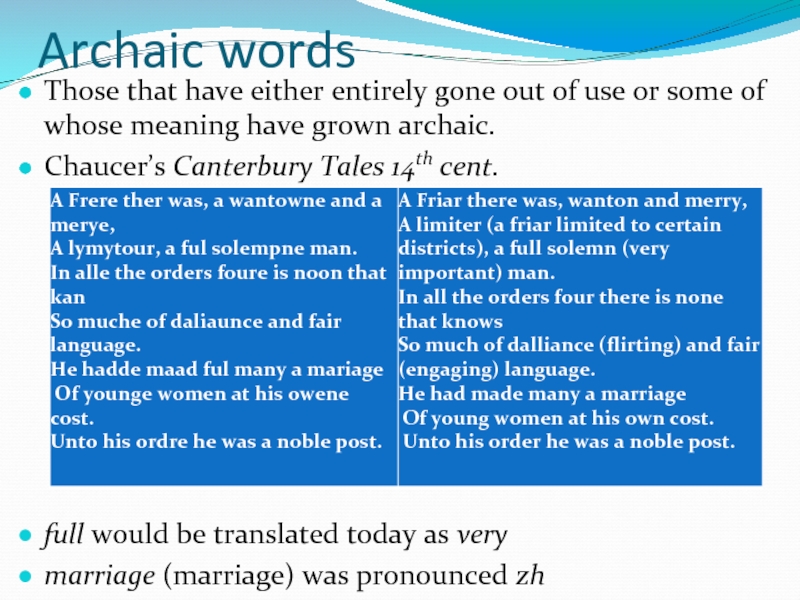

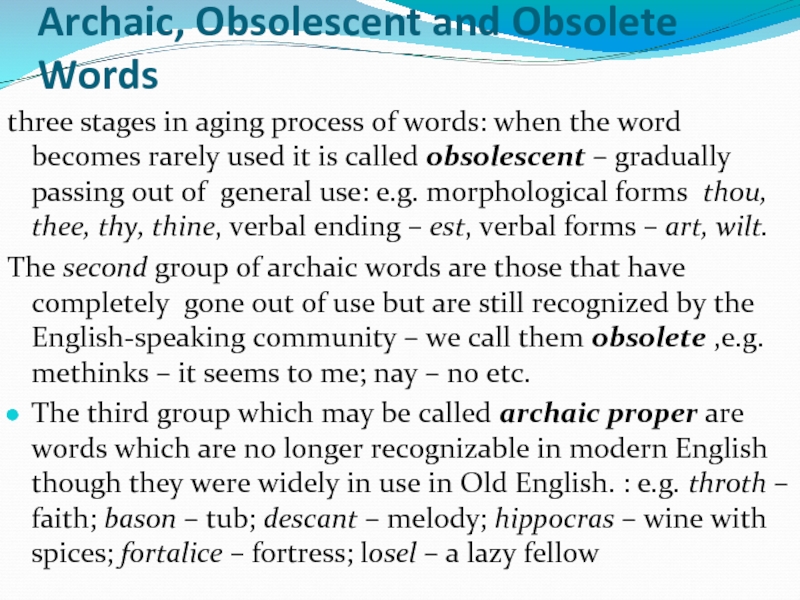

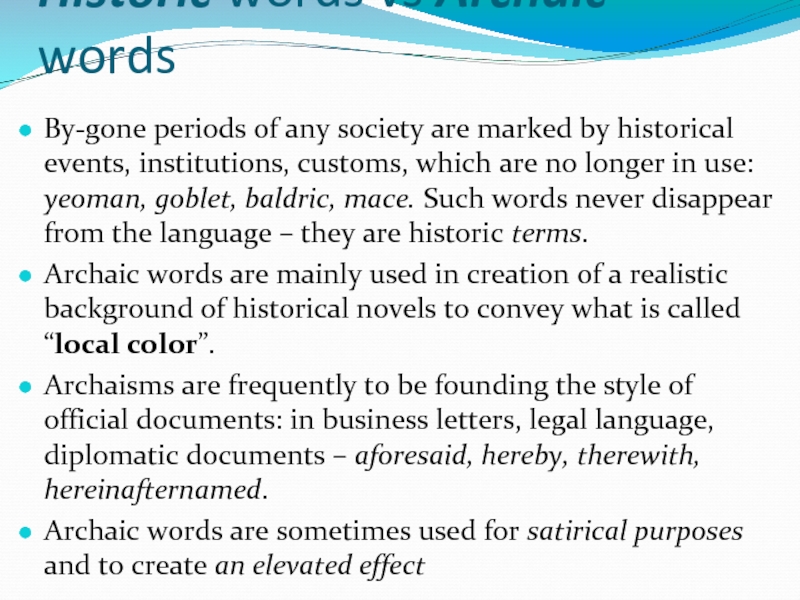

c) Archaic words. The

word stock of a language is in an increasing state of change. In every period

in the development of a literary language one can find words which will show

more or less apparent changes in their meaning or usage, from full vigour,

through a moribund state, to death, i.e. complete disappearance of the unit

from the language .We’ll distinguish 3 stages in the aging process of words: 1)

the beginning of the aging process when the word becomes rarely used. Such

words are called obsolescent, i.e. they are in the stage of gradually passing

out of general use; 2) The second group of archaic words are those that have

already gone completely out of use but are still recognized by the English

speaking community. These words are called obsolete. 3) The third group, which

may be called archaic proper, are words which are no longer recognized in

modern English, words that were in use in Old English and which have either

dropped out of the language entirely or have changed in their appearance so

much that they have become unrecognizable.

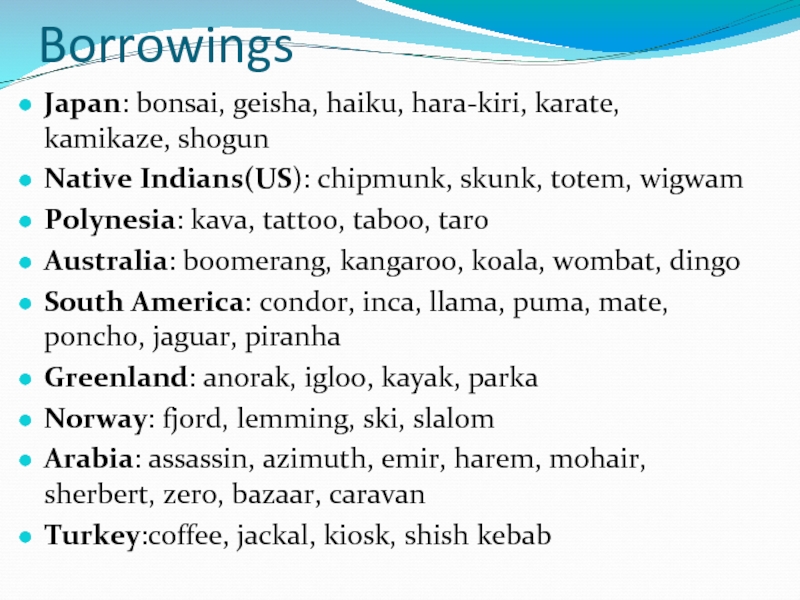

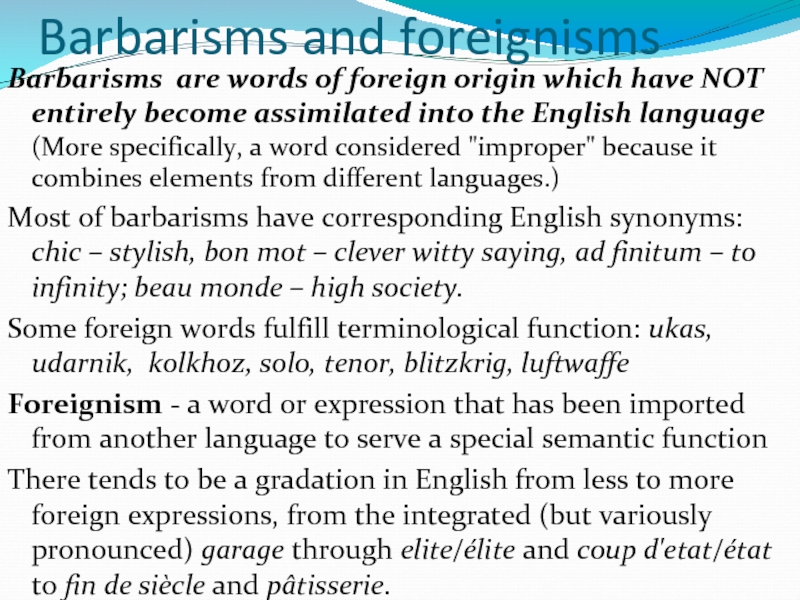

d) Barbarisms and foreign words.

Barbarisms are words of foreign origin which have not entirely been assimilated

into the English language. They bear the appearance of a borrowing and are felt

as something alien to the native tongue. The great majority of the borrowed

words now form part of the rank and file of the English vocabulary. There are

some words which retain their foreign appearance to greater or lesser degree.

These words, which are called barbarisms, are also considered to be on the outskirts

of the literary language. Most of them have corresponding English synonyms.

Barbarisms are not made conspicuous in the text unless they bear a special load

of stylistic information. Foreign words do not belong to the English

vocabulary. In printed works foreign words and phrases are generally italicized

to indicate their alien nature or their stylistic value. There are foreign

words which fulfill a terminological function.

e) Literary coinages. Every

period in the development of a language produces an enormous number of new

words or new meanings of established words. Most of them do not live long. They

are coined for use at the moment of speech, and therefore possess a peculiar

property – that of temporariness. The given word or meaning holds only in the

given context and is meant only to “serve the occasion”. However, a word or a

meaning once fixed in writing may become part and parcel of the general

vocabulary irrespective of the quality of the word. Neologisms are mainly

coined according to the productive models for word-building in the given

languages. Most of the literary coinages are built by means of affixation and

word compounding.

Special colloquial vocabulary

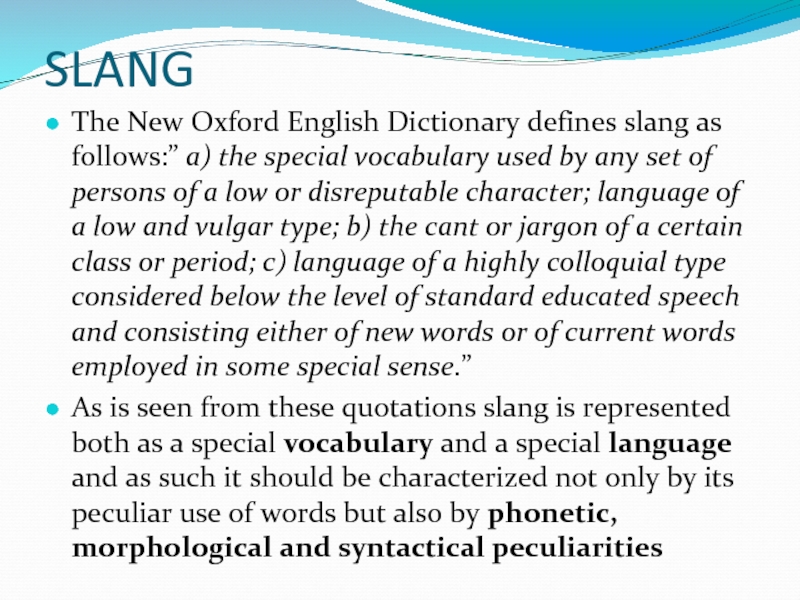

a) Slang. The term slang is ambiguous and

obscure. The “New Oxford English Dictionary” defines slang as follows:1) the

special vocabulary used by any set of persons of low or disreputable character;

language of a low and vulgar type…; 2) the cant or jargon of a certain class or

period; 3) language of highly colloquial type considered as below the level of

standard educated speech, and consisting either of new words or current words employed

in some special sense. In England and USA slang is regarded as the quintessence

of colloquial speech and therefore stands above all the laws of grammar.

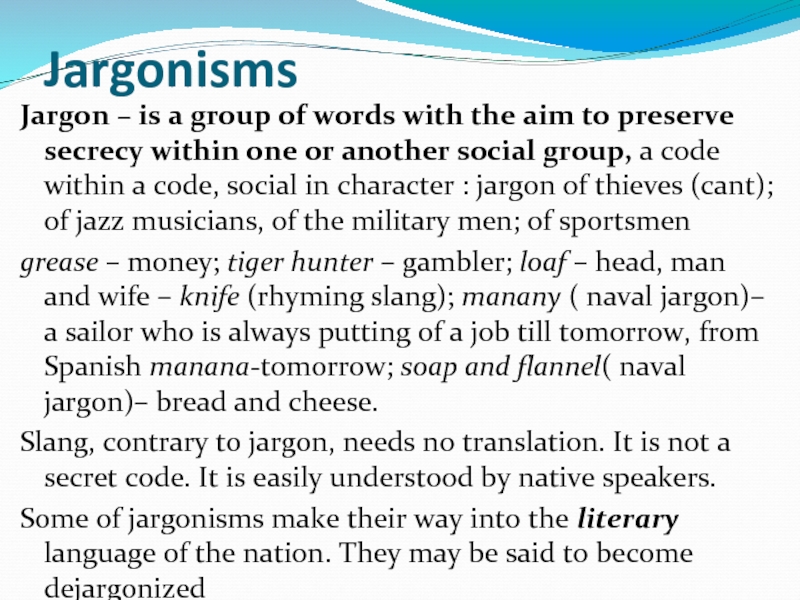

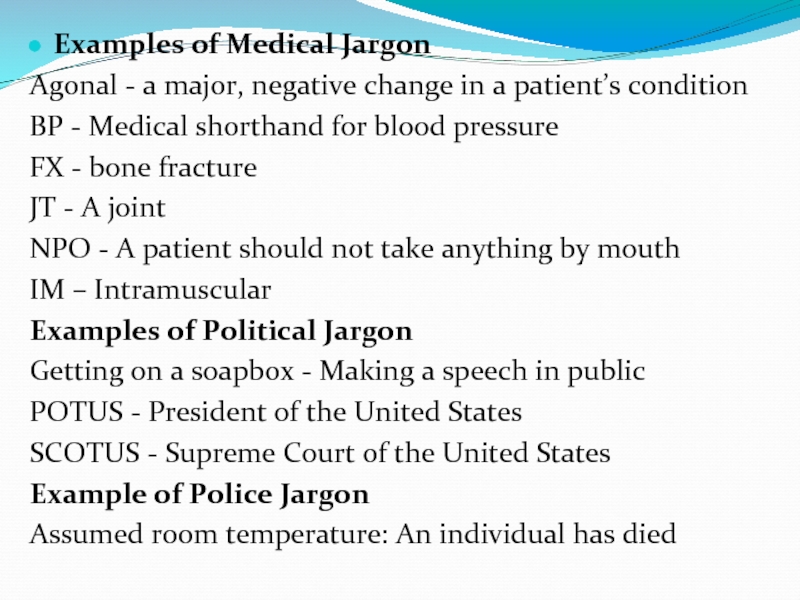

b) Jargonisms. Jargon is a recognized term for a group of words that

exist in almost every language and whose aim is to preserve secrecy within one

or another social group. Jargonisms are generally old words with entirely new meanings

imposed on them. Most of the jargonisms of any language are absolutely

incomprehensible to those outside the social group which has invented them.

They may be defined as a code within a code. Jargonisms are social in

character. In England and in the USA almost any social group of people has its

own jargon. There is a common jargon and special professional jargons.

Jargonisms do not always remain on the outskirts of the literary language. Many

words entered the standard vocabulary.

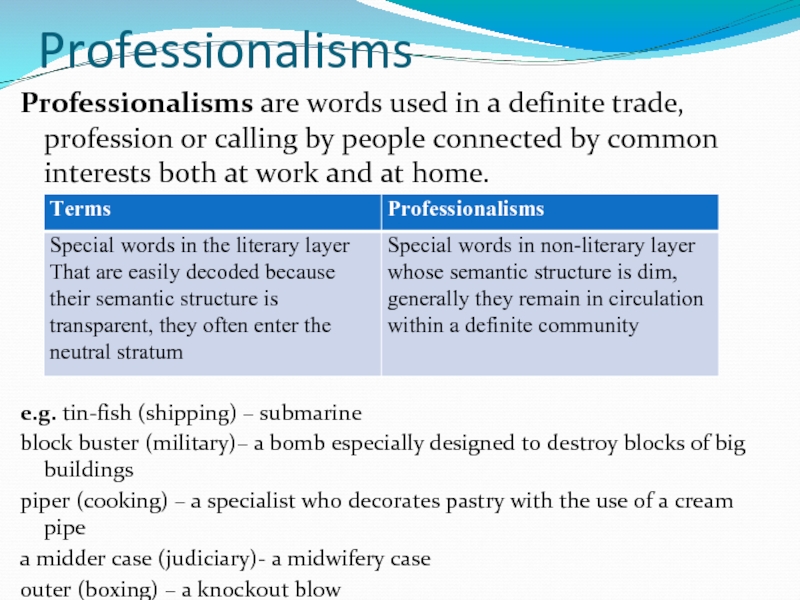

c) Professionalisms. Professionalisms are the words used

in a definite trade, profession or calling by people connected by common

interests both at work or at home. Professional words name anew already

existing concepts, tools or instruments, and have the typical properties of a

special code. Their main feature is technicality. They are mono semantic. Professionalisms

do not aim at secrecy. They fulfill a socially useful function in

communication, facilitating a quick and adequate grasp of the message.

Professionalisms are used in emotive prose to depict the natural speech of a

character. The skillful use of a professional word will show not only the

vocation of a character, but also his education, breeding, environment and

sometimes even his psychology.

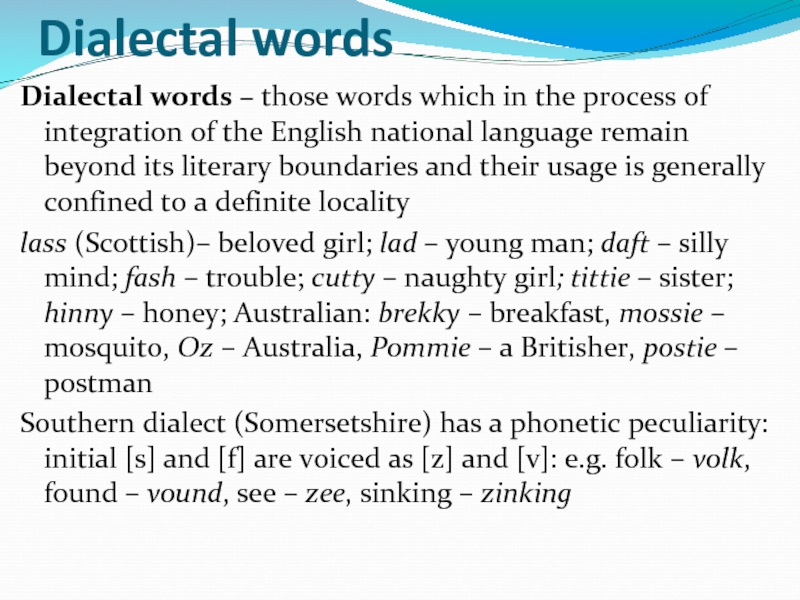

d) Dialectal words. Dialectal words are those which in

the process of integration of the English national language remained beyond its

literary boundaries, and their use is generally confined to a definite

locality. There sometimes is confusion between the terms dialectal, slang and

vernacular. All these groups when used in emotive prose are meant to

characterize the speaker as a person of a certain locality, breeding,

education, etc. Some dialectal words are universally accepted as recognized

units of the standard colloquial English. Of quite a different nature are

dialectal words which are easily recognized as corruptions of standard English words.

Dialectal words are only to be found in the style of emotive prose, very rarely

in other styles. And even here their use is confined to the function of

characterizing personalities through their speech.

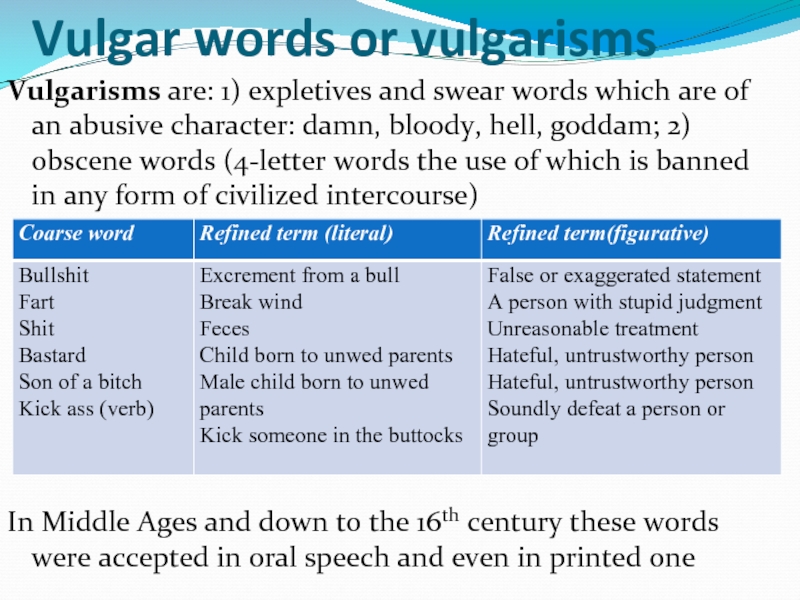

e) Vulgar words. The term vulgarism is rather

misleading. Webster’s “New International Dictionary” defines vulgarism as “a vulgar

phrase or expression, or one used only in colloquial, or, esp. in unrefined or

low, speech”. I.R.Galperin defines vulgarisms as expletives or swear-words and

obscene words and expressions. There are different degrees of vulgar words.

Some of them, the obscene ones, are called “four-letter” words. A lesser degree

of vulgarity is presented by expletives and they sometimes appear in

euphemistic spelling. The function of vulgarisms is almost the same as that of interjections

that is to express strong emotions. They are not to be found in any style of

speech except emotive prose, and here only in the direct speech of the characters.

f) Colloquial coinages. Colloquial coinages (nonce-words)

are spontaneous and elusive. Most of them disappear from the language leaving

no trace in it. Some nonce-words and meanings may acquire legitimacy and thus

become facts of the language, while on the other hand they may be classified as

literary or colloquial according to which of the meanings is being dealt with. When

a nonce-word comes into general use and is fixed in dictionaries, it is classified

as a neologism for a very short period of time. This shows the objective

reality of contemporary life. Technical progress is so rapid that it builds new

notions and concepts which in their turn require new words to signify them. Nonce-coinage

appears in all spheres of life.

Conclusion

Every manual on stylistics acquaints

the learners with specific features of various types of speech. Studying the

stylistic differentiation of the vocabulary gives a deep understanding of the

context of the text and lets implement a suitable lexis, orally or in a written

form, according to the given situation. Moreover, it gives us a vision of a

time or epoch that can be introduced in a text or a poetry that appears to be a

connection with deep historical roots.

Используемая литература:

1. «Лексикология английского

языка», Антрушина Г. Б., Афанасьева О. В., Морозова Н. Н., М.: Дрофа, 1999,

288с.

2. «Основы стилистики

английского языка», Ю.М. Скребнев. М.: ООО «Издательство Астрель»: 2003, 221 с

3. «Текст как объект лингвистического

исследования», Гальперин И.Р., М: КомКнига, 2006, 144 с

4. https://ru.scribd.com/doc/46997418/Stylistic-Differentiation-of-the-English-Vocabulary

Подборка по базе: Акпатер жалпы орта бiлiм беретiн мектебi КММ.docx, Қазақстан Республикасының Білім және ғылым министрлігі (1).docx, Игра-викторина по казахскому языку на тему_ «Қазақстан Республик, Қазақстан Республикасының Білім және ғылым министрлігі Ауыстырыл, _Қазақстан Республикасының Рәміздері_ тест.docx, Қазақстан Республикасының конституциялық құқығы -жетекші құқық с, ҚАЗАҚСТАН РЕСПУБЛИКАСЫНЫҢ БІЛІМ ЖӘНЕ ҒЫЛЫМ МИНИСТРЛІГІ555.docx, Игра-викторина по казахскому языку на тему_ «Қазақстан Республик, _аза_стан Республикасыны_ денсаулы_ са_тау министірлігі.docx, Қазақстан Республикасының Конституциясы.docx

e) Literary Coinages (Including Nonce-Words)

Neologism — ‘a new word or a new meaning for an established word.’

Every period in the development of a language produces an enormous number of new words or new meanings of established words. Most of them do not live long. They are not meant to live long. They are coined for use at the moment of speech, and therefore possess a peculiar property —that of temporariness. The given word or meaning holds only in the given context and is meant only to «serve the occasion.»

However, such is the power of the written language that a word or a meaning used only to serve the occasion, when once fixed in writing, may become part and parcel of the general vocabulary.

The coining of new words generally arises first of all with the need to designate new concepts resulting from the development of science and also with the need to express nuances of meaning called forth by a deeper understanding of the nature of the phenomenon in question. It may also be the result of a search for a more economical, brief and compact form of utterance which proves to be a more expressive means of communicating the idea.

The first type of newly coined words, i.e. those which designate newborn concepts, may be named terminological coinages. The second type, i.e. words coined because their creators seek expressive utterance may be named stylistic coinages.

Among new coinages of a literary-bookish type must be mentioned a considerable layer of words appearing in the publicistic style, mainly in newspaper articles and magazines and also in the newspaper style— mostly in newspaper headlines.

Another type of neologism is the nonce-word – a word coined to suit one particular occasion. They rarely pass into the standard language and remind us of the writers who coined them.

3. Special colloquial vocabulary

Colloquial words mark the message as informal, non-official, conversational. Apart from general colloquial words, widely used by all speakers of the language in their everyday communication (e. g. «dad», «kid», «crony», «fan», «to pop», «folks»).

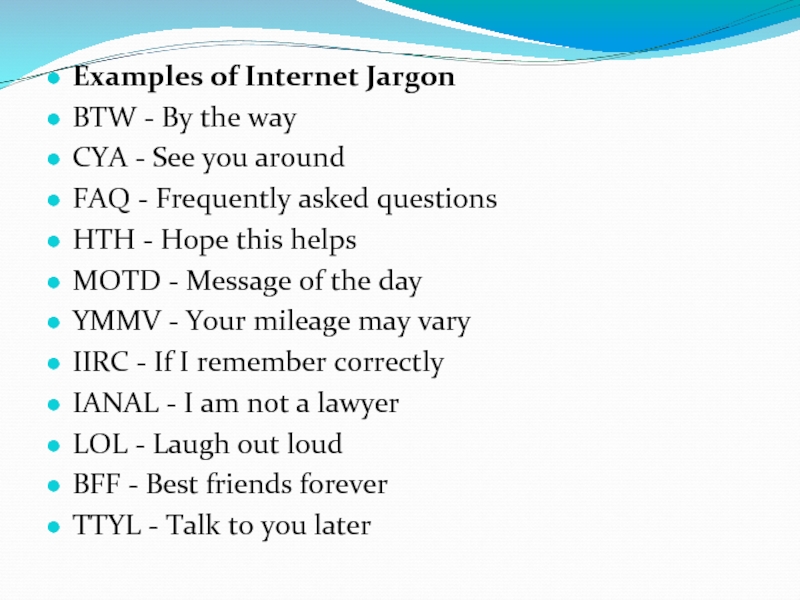

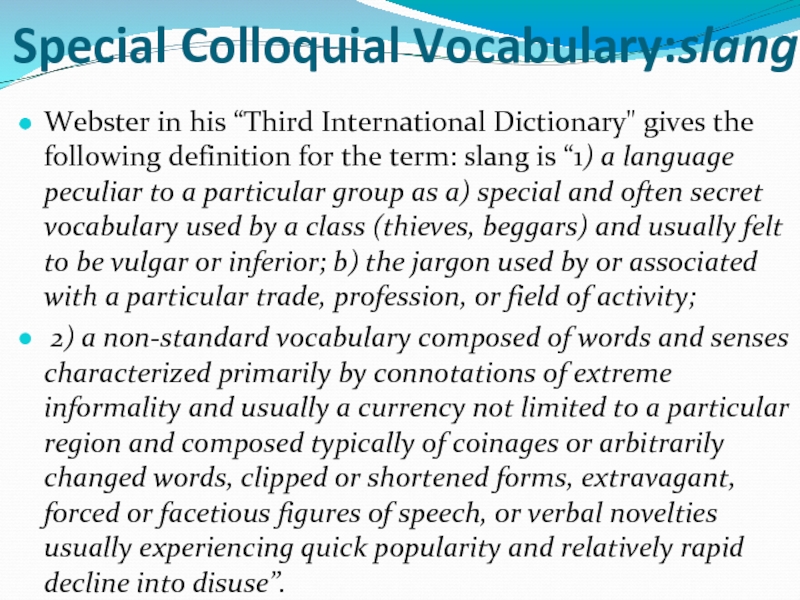

a) Slang

There is hardly any other term that is as ambiguous and obscure as the term slang. Slang seems to mean everything that is below the standard of, usage of present-day English.

Slang [origin unknown] — language peculiar to a particular group: as a: the special and often secret vocabulary used by a class (as thieves, beggars) and usu. felt to be vulgar or inferior: argot; b: the jargon used by or associated with a particular trade, profession, or field of activity; 2: a non-standard vocabulary composed of words and senses characterized primarily by connotations of extreme informality and usu. a currency not limited to a particular region and composed typically of coinages or arbitrarily changed words, clipped or shortened forms, extravagant, forced or facetious figures of speech, or verbal novelties usu. experiencing quick popularity and relatively rapid decline into disuse.

— words or expressions that are very informal and are not considered suitable for more formal situations. Some slang is used only by a particular group of people (Macmillan).

Slang words, used by most speakers in very informal communication, are highly emotive and expressive and as such, lose their originality rather fast and are replaced by newer formations. This tendency to synonymic expansion results in long chains of synonyms of various degrees of expressiveness, denoting one and the same concept. So, the idea of a «pretty girl» is worded by more than one hundred ways in slang.

In only one novel by S. Lewis there are close to a dozen synonyms used by Babbitt, the central character, in reference to a girl: «cookie», «tomato», «Jane», «sugar», «bird», «cutie», etc.

b) Jargonisms

Jargonism is a recognized term for a group of words that exists in almost every language and whose

aim is to preserve secrecy within one or another social group. Jargonisms are generally old words with entirely new meanings imposed on them. Most of the jargonisms of any language, and of the English language too, are absolutely incomprehensible to those outside the social group which has invented them. They may be defined as a code within a code, that is special meanings of words that are imposed on the recognized code—the dictionary meaning of the words.

Thus the word grease means ‘money’; loaf means ‘head’; a tiger hunter is ‘a gambler’; a lexer is ‘a student preparing for a law course’.

Jargonisms are social in character. They are not regional. In Britain and in the US almost any social group of people has its own jargon. The following jargons are well known in the English language: the jargon of thieves and vagabonds, generally known as cant; the jargon of jazz people; the jargon of the army, known as military slang; the jargon of sportsmen, and many others.

Jargonisms, like slang and other groups of the non-literary layer, do not always remain on the outskirts of the literary language. Many words have overcome the resistance of the language lawgivers and purists and entered the standard vocabulary. Thus the words kid, fun, queer, bluff, fib, humbug, formerly slang words or jargonisms, are now considered common colloquial. They may be said to be dejargonized.

c) Professionalisms

Professionalisms are the words used in a definite trade, profession or calling by people connected by common interests both at work and at home. Professionalisms are correlated to terms. Terms, as has already been indicated, are coined to nominate new concepts that appear in the process of, and as a result of, technical progress and the development of science. In distinction from slang, jargonisms and professionalisms cover a narrow semantic field, for example connected with the technical side of some profession.

Professional words name anew already-existing concepts, tools or instruments, and have the typical properties of a special code. The main feature of a professionalism is its technicality. Professionalisms are special words in the non-literary layer of the English vocabulary, whereas terms are a specialized group belonging to the literary layer of words. Professionalisms are not known to simple people.

d) Dialectal words

Dialectal words are those which in the process of integration of the English national language remained beyond its literary boundaries, and their use is generally confined to a definite locality. We exclude here what are called social dialects or even the still looser application of the term as in expressions like poetical dialect or styles as dialects.

Dialectal words are normative and devoid of any stylistic meaning in regional dialects, but used outside of them, carry a strong flavour of the locality where they belong. DW has application limited to a certain group of people or to certain communicative situations.

e) Vulgar words or vulgarisms

Vulgarisms are:

1) expletives and swear words which are of an abusive character, like ‘damn’, ‘bloody’, ‘to hell’, ‘goddam’ and, as some dictionaries state, used now, as general exclamations;

2) obscene words. These are known as four-letter words the use of which is banned in any form of intercourse as being indecent.

The function of expletives is almost the same as that of interjections, that is to express strong emotions, mainly annoyance, anger, vexation and the like. They are not to be found in any functional style of language except emotive prose, and here only in the direct speech of the characters.

f) Colloquial coinages (words and meanings)

Colloquial coinages (nonce-words), unlike those of a literary-bookish character, are spontaneous and elusive. Not all of the colloquial nonce-words are fixed in dictionaries or even in writing and therefore most of them disappear from the language leaving no trace in it.

Unlike literary-bookish coinages, nonce-words of a colloquial nature are not usually built by means of affixes but are based on certain semantic changes in words that are almost imperceptible to the linguistic observer until the word finds its way into print.

Kucharenko V.A. A book of practice in Stylistics pp. 25-28, questions, ex. 1, 2, 4.

Lecture 3 Phonetic Stylistic Devices and Graphical Means.

1. Onomatopoeia

2. Alliteration

3. Rhyme

4. Rhythm

5. Graphical Means

The stylistic approach to the utterance is not confined to its structure and sense. There is another thing to be taken into account which, in a certain type of communication plays an important role. This is the way a word, a phrase or a sentence sounds. The sound of most words taken separately will have little or no aesthetic value.

A word may acquire a desired phonetic effect only in combination with other words. The way a separate word sounds may produce a certain euphonic effect, but this is a matter of individual perception and feeling and therefore subjective. However there exist psychological works on the theory of sound symbolism. They checked the associations, which the tested people have with the definite sounds. Statistics shows that their answers coincide very often.

Verier St Woolman, one of the founders of the theory of sound symbolism claimed that a certain sound when pronounced clearly and strong has special meaning and feeling. For example the sound [d], when repeated often may produce an effect of something evil, negative and wicked.

The sound of a word, or more exactly the way words sound in combination, often contributes something to the general effect of the message, particularly when the sound effect has been deliberately worked out. This can easily be recognized when analyzing alliterative word combinations or the rhymes in certain stanzas or from more elaborate analysis of sound arrangement.

The aesthetiс effect of the text is composed not only with the help of sounds and prosody, but with the help of sounds and prosody together with the meaning. The sound side of the belles-letters work makes a whole with rhythm and meaning and can’t influence the reader separately.

To influence aesthetically the sound part of the text should somehow be highlightened. An author can increase an emotional and aesthetic effect of his work through choosing the words, their arrangement and repetitions. Let’s see what phonetic SDs can secure this function.

1. Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is a combination of speech sounds which aims at imitating sounds produced in nature (wind, sea, thunder, etc. – splash, bubble, rustle, whistle) by things (machines or tools, etc. — buzz) by people (singing, laughter, yawning, roar, giggle) and animals (moo, bleat, croak — frog). Therefore the relation between onomatopoeia and the phenomenon it is supposed to represent is one of metonymy: that is it can be used in transferred meaning – tintinnabulation-the sound of bells

There are two varieties of onomatopoeia: direct and indirect.

Direct onomatopoeia is contained in words that imitate natural sounds, as thud, bowwow, ding-dong, buzz, bang, ‘cuckoo. These words have different degrees of ‘imitative quality. Some of them immediately bring to mind whatever it is that produces the sound. Others require some imagination to decipher it.

e.g. And now there came the chop-chop of wooden hammers.

Indirect onomatopoeia is a combination of sounds the aim of which is to make the sound of the utterance an echo of its sense. It is sometimes called «echo writing». Indirect onomatopoeia demands some mention of what makes the sound, as rustling of curtains in the following line. And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain. An example is: And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain» (E. A. Poe), where the repetition of the sound [s] actually produces the sound of the rustling of the curtain.

Indirect onomatopoeia is sometimes effectively used by repeating words which themselves are not onomatopoetic but they contribute to the general impact of the utterance: in the poem Boots by R. Kipling soldiers’ tread is shown —

We’re foot-slog-slog-slog-sloggin’ over Africa –

Foot-foot-foot-foot –sloggin’ over Africa.

(Boots – boots – boots – boots – moovi’ up and down again!)

Onomatopoeia helps to create the vivid portrayal of the situation described, and the phonemic structure of the word is important for the creation of expressive and emotive connotations.

2. Alliteration and assonance

Alliteration is a phonetic stylistic device which aims at imparting a melodic effect to the utterance. The essence of this device lies in the repetition of similar sounds, in particular consonant sounds, in close succession, particularly at the beginning of successive words: » The possessive instinct never stands still (J. Galsworthy) or, «Deep into the darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, doubting, dreaming dreams no mortals ever dared to dream before» (E. A. Poe). Alliteration is also used to name the repetition of first letters: Apt Alliteration’s artful aid.(Charles Churchill).

Alliteration has a long tradition in English poetry as Germanic and Anglo-Saxon poems were organized with its help. (Beowulf)