Two sign language Interpreters working as a team for a school.

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which uses manual communication, body language, and lip patterns instead of sound to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Signs often represent complete ideas, not only words. However, in addition to accepted gestures, mime, and hand signs, sign language often includes finger spelling, which involves the use of hand positions to represent the letters of the alphabet.

Although often misconceived of as an imitation or simplified version of oral language, linguists such as William Stokoe have found sign languages to be complex and thriving natural languages, complete with their own syntax and grammar. In fact, the complex spatial grammars of sign languages are markedly different than that of spoken language.

Sign languages have developed in circumstances where groups of people with mutually unintelligible spoken languages found a common base and were able to develop signed forms of communication. A well-known example of this is found among Plains Indians, whose lifestyle and environment was sufficiently similar despite no common base in their spoken languages, that they were able to find common symbols that were used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes.

Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which include people who are deaf or hard of hearing, friends and families of deaf people, as well as interpreters. In many cases, various signed «modes» of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language. Sign language differs from one region to another, just as do spoken languages, and are mutually unintelligible. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the core of local deaf cultures. The use of these languages has enabled the deaf to be recognized as intelligent, educable people who are capable of living life as fully and with as much value as anyone else. However, much controversy exists over whether teaching deaf children sign language is ultimately more beneficial than methods that allow them to understand oral communication, such as lip-reading, since this enables them to participate more directly and fully in the wider society. Nonetheless, for those people who remain unable to produce or understand oral language, sign language provides a way to communicate within their society as full human beings with a clear cultural identity.

History and development of sign language

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development, even in situations where there may be a common spoken language. Because they developed on their own, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language. American Sign Language does have some similarities to French Sign Language, due to its early influences. When people using different signed languages meet, however, communication can be easier than when people of different spoken languages meet. This is not because sign languages are universal, but because deaf people may be more patient when communicating, and are comfortable including gesture and mime.[1]

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart because each linguistic population contains deaf members who generated a sign language. Geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages; the same forces operate on signed languages, therefore they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have little or no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a «national» sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of (residential) schools for the deaf.

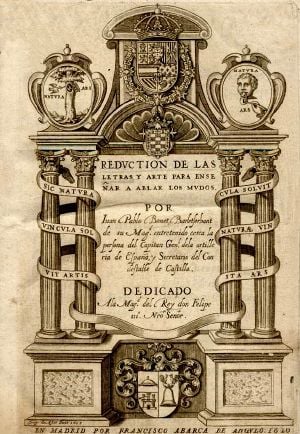

Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Madrid, 1620).

The written history of sign language began in the seventeenth century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (Reduction of letters and art for teaching dumb people to speak) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of phonetics and speech therapy, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs in the form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the eighteenth century, which has remained basically unchanged until the present time. In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first public school for deaf children in Paris. His lessons were based upon his observations of deaf people signing with hands in the streets of Paris. Synthesized with French grammar, it evolved into the French Sign Language.

Laurent Clerc, a graduate and former teacher of the French School, went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[2] Others followed. In 1817, Clerc and Gallaudet founded the American Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb (now the American School for the Deaf). Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet, founded the first college for the deaf in 1864 in Washington, DC, which in 1986, became Gallaudet University, the only liberal arts university for the deaf in the world.

Engravings of Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos:[3]

-

A.

-

B, C, D.

-

E, F, G.

-

H, I, L.

-

M, N.

-

O, P, Q.

-

R, S, T.

-

V, X, Y, Z.

2007 Chinese Taipei Olympic Day Run in Taipei City: Deaflympics Taipei 2009 Easy Sign Language Section.

International Sign, formerly known as «Gestuno,» was created in 1973, to enhance communication among members of the deaf community throughout the world. It is an artificially constructed language and though some people are reported to use it fluently, it is more of a pidgin than a fully formed language. International Sign is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf.[4]

Linguistics of sign

In linguistic terms, sign languages are rich and complex, despite the common misconception that they are not «real languages.» William Stokoe started groundbreaking research into sign language in the 1960s. Together with Carl Cronenberg and Dorothy Casterline, he wrote the first sign language dictionary, A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[5] It was during this time he first began to refer to sign language not just as sign language or manual communication, but as «American Sign Language,» or ASL. This ground-breaking dictionary listed signs and explained their meanings and usage, and gave a linguistic analysis of the parts of each sign. Since then, linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages.

Did you know?

Sign languages are complex and contain every linguistic component required to be classified as true languages

Sign languages are not merely pantomime, but are made of largely arbitrary signs that have no necessary visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. Nor are they a visual renditions of an oral language. They have complex grammars of their own, and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the philosophical and abstract. For example, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[6]

The American manual alphabet in photographs

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Hand shape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarized in the acronym HOLME. Signs, therefore, are not an alphabet but rather represent words or other meaningful concepts.

In addition to such signs, most sign languages also have a manual alphabet. This is used mostly for proper names and technical or specialized vocabulary. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages are simplified versions of oral languages, but it is merely one tool in complex and vibrant languages. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression, and the body posture at the same time. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Spatial grammar and simultaneity

Sign languages are able to capitalize on the unique features of the visual medium. Oral language is linear and only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, instead, is visual; hence, a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously.

As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, «I drove here.» To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, «I drove here along a winding road,» or «I drove here. It was a nice drive.» However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb «drive» by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb «drive» is being signed. Therefore, in English the phrase «I drove here and it was very pleasant» is longer than «I drove here,» in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

Written forms of sign languages

Sign languages are not often written, and documented written systems were not created until after the 1960s. Most deaf signers read and write the oral language of their country. However, there have been several attempts at developing scripts for sign language. These have included both «phonetic» systems, such as Hamburg Sign Language Notation System, or HamNoSys,[7] and SignWriting, which can be used for any sign language, as well as «phonemic» systems such as the one used by William Stokoe in his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language, which are designed for a specific language.

The phonemic systems of oral languages are primarily sequential: That is, the majority of phonemes are produced in a sequence one after another, although many languages also have non-sequential aspects such as tone. As a consequence, traditional phonemic writing systems are also sequential, with at best diacritics for non-sequential aspects such as stress and tone. Sign languages have a higher non-sequential component, with many «phonemes» produced simultaneously. For example, signs may involve fingers, hands, and face moving simultaneously, or the two hands moving in different directions. Traditional writing systems are not designed to deal with this level of complexity.

The Stokoe notation is sequential, with a conventionalized order of a symbol for the location of the sign, then one for the hand shape, and finally one (or more) for the movement. The orientation of the hand is indicated with an optional diacritic before the hand shape. When two movements occur simultaneously, they are written one atop the other; when sequential, they are written one after the other. Stokoe used letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals to indicate the handshapes used in fingerspelling, such as «A» for a closed fist, «B» for a flat hand, and «5» for a spread hand; but non-alphabetic symbols for location and movement, such as «[]» for the trunk of the body, «×» for contact, and «^» for an upward movement.

SignWriting, developed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton, is highly featural and visually iconic, both in the shapes of the characters—which are abstract pictures of the hands, face, and body—and in their spatial arrangement on the page, which does not follow a sequential order like the letters that make up written English words. Being pictographic, it is able to represent simultaneous elements in a single sign. Neither the Stokoe nor HamNoSys scripts were designed to represent facial expressions or non-manual movements, both of which SignWriting accommodates easily.

Use of signs in hearing communities

While not full languages, many elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, in baseball, while hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union, the referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators.

On occasion, where there are enough deaf people in the area, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the U.S., Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana, and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities, deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

Sign language has also been used to facilitate communication among peoples of mutually intelligible languages. In the case of Chinese and Japanese, where the same body of written characters is used but with different pronunciation, communication is possible through watching the «speaker» trace the mutually understood characters on the palm of their hand.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America. Although the languages of the Plains Indians were unrelated, their way of life and environment had many common features. They were able to find common symbols which were then used to communicate even complex narratives among different tribes. For example, the gesture of brushing long hair down the neck and shoulders signified a woman, two fingers astride the other index finger represented a person on horseback, a circle drawn against the sky meant the moon, and so forth. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Home sign

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign).

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child is forced to invent signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and does not meet the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence.

Benefits

For deaf and hard of hearing students, there have been long standing debates regarding the teaching and use of sign language versus oral methods of communication and lip reading. Proficiency in sign language gives deaf children a sense of cultural identity, which enables them to bond with other deaf individuals. This can lead to greater self-esteem and curiosity about the world, both of which enrich the student academically and socially. Certainly, the development of sign language showed that deaf-mute children were educable, opening educational opportunities at the same level as those who hear.

Notes

- ↑ David Bar-Tzur, International Gesture:Principles and Gestures, July 13, 2002. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Loida Canlas, Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Juan Pablo Bonet, Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos (Editorial Cepe, 1992, ISBN 978-8478690718).

- ↑ Jolanta Lapiak, Gestuno (a.k.a International Sign Language) HandSpeak. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ William C. Stokoe, Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles (Linstok Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0932130013).

- ↑ Karen Nakamura, About Japanese Sign Language Deaf Resource Library. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ HamNoSys DGS Corpus. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aronoff, Mark, and Janie Rees-Miller. The Handbook of Linguistics. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2020. ISBN 978-1119302070

- Bonet, Juan Pablo. Reducción de las Letras y Arte para Enseñar a Hablar a los Mudos. Editorial Cepe, 1992. ISBN 978-8478690718

- Emmorey, Karen, Harlan L. Lane, Ursula Bellugi, and Edward S. Klima. The Signs of Language Revisited: An Anthology to Honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000. ISBN 978-0585356419

- Groce, Nora Ellen. Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0674270404

- Kendon, Adam. Sign languages of Aboriginal Australia Cultural, Semiotic, and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0521360080

- Klima, Edward S., and Ursula Bellugi. The Signs of Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0674807952

- Lane, Harlan L. The Deaf Experience Classics in Language and Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0674194601

- Lane, Harlan L. When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf. New York: Random House, 1984. ISBN 0394508785

- Lucas, Ceil. Multicultural Aspects of Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities: Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities, vol. 2. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1563680465

- Padden, Carol, and Tom Humphries. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0674194236

- Poizner, Howard. What the Hands Reveal about the Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0262161053

- Sacks, Oliver W. Seeing Voices: A Journey into the Land of the Deaf. Vintage, 2000. ISBN 978-0375704079

- Stiles, Joan, Mark Kritchevsky, and Ursula Bellugi. Spatial Cognition: Brain Bases and Development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988. ISBN 978-0805800463

- Stokoe, William C. Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Linstok Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0932130013

- Stokoe, William C. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf. Linstok Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0932130037

- Tomkins, William. Indian Sign Language. Dover Publications, 1969. ISBN 978-0486220291

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ABC Slider Learn ASL fingerspelling

- ASL Browser Video dictionary of ASL signs

- 32 Uses and Benefits of American Sign Language (ASL) for Silent Communications

- Why Is It Important to Learn American Sign Language (ASL)?

- Top 26 Resources for Learning Sign Language

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sign_language history

- History_of_the_deaf history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Sign language»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

General

Gloss and transcription symbols

You may notice capitalized words, words with hypen and plus symbols, and non-English grammar here and there on the handspeak site as well as in sign language literature. They are a transcription of the ASL sentences, phrases, or words.

What is gloss

Wilcox describes gloss used for sign language transcription as follows:

Glossing is the practice of writing a morpheme-by-morpheme ‘translation’ using English words. Glosses indicate what the individual parts of the native word mean. Glosses do not provide a true translation, which would instead use appropriate English ways of saying «The same thing.»

For example, German Es geht mir gut may be glossed as «It goes to-me good» (the hyphenated gloss «to-me» indicates that it refers to a single word in the original). A true English translation of this expression would be something like, «I’m doing fine.» Ref

Glossing is not the same as translation. If the English sentence «I’m doing fine» were glossed in German transcription. It would look strange to German speakers and vice versa alike. Each language, whether signed or spoken, has their own grammar and structure.

When to use glosses

Glosses may be used in sign language books and other printed media on sign language linguistics and such. This Handspeak site often uses glosses and transcription symbols along with or without the videos to help online learners visualize.

However, keep in mind that ASL teachers normally don’t use glosses in ASL classes, as learning and teaching are interactive. They may use them occasionally for certain pedagogical purposes in classes.

Below is a list of some conventional and few modified symbols, their examples, and explanation for this site.

The website «Handspeak» uses two different colors to identify ASL and English: gloss in aqua to indicate ASL and sometimes this color in translation for English.

capital letters. An English gloss in capital letters represents an ASL word or sign. It is known as gloss. Remember this is not a translation. It is only an approximate representation of the ASL sign itself, not necessarily a meaning.

The hyphen — is used to represent a single ASL word/sign when more than one English gloss is used. E.g. stare-at (a single ASL word) or GO-to.

The plus sign + between two ASL words is used for ASL compound words. Eg true+work for sure enough, MOTHER+FATHER for parents.

The plus sign ++ at the end of a gloss indicates a number of repetition of an ASL word. Eg again++ (signing «again» two more time) meaning «again and again». Another example, HELP+++ for «help many/several times» or «help from time to time» depending on the duration of the movement and spatial reference to convey different meanings.

/ is used for raised eyebrows as found in topicalization, yes-no questions, and conjunctions. On the other hand, / is for burrowed eyebrows as found in wh-questions.

t or topic is a shortcut for «topicalization», usually with raised eyebrows.

fs- represents a fingerspelled word. Eg fs-ALICE

# represents a fingerspelled loan sign. Eg #ALL

ix, a shortcut for «index», is for a referential point in space. IX1 can mean one side and IX2 for another side of the signing space. It doesn’t matter which side it is as long as you establish a spatial reference for a noun and you keep consistent with it in a sentence or paragraph until the subject is changed.

CL is a shortcut for «classifier» which can function as a «pronoun» or another form that represents an ASL noun and/or its verb predicate. It is used in a verb phrase as well as prepositional phrase.

loc is a shortcut for «locative», a part of the grammatical structure in ASL.

Think in ASL

A typical challenge is that hearing ASL learners often think in English while signing ASL. In our ASL classes, we often emphasize that ASL students must think in ASL while speaking ASL, just like when they speak French or another second language, they think in that language.

A concern with glossing is that glossing might reinforce the association of ASL with English that ASL students have a tendency to to think in English when articulating ASL. Remember that glosses are not true translation. Glosses are used for helping transcribing in print when ASL writing is not used.

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which, instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns, uses visually transmitted sign patterns (manual communication, body language and lip patterns) to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which can include interpreters and friends and families of deaf people as well as people who are deaf or hard of hearing themselves.

Wherever communities of deaf people exist, sign languages develop. In fact, their complex spatial grammars are markedly different from the grammars of spoken languages. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the cores of local Deaf cultures. Some sign languages have obtained some form of legal recognition, while others have no status at all.

In addition to sign languages, various signed codes of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language.[1] These are not to be confused with languages, oral or signed; a signed code of an oral language is simply a signed mode of the language it carries, just as a writing system is a written mode. Signed codes of oral languages can be useful for learning oral languages or for expressing and discussing literal quotations from those languages, but they are generally too awkward and unwieldy for normal discourse. For example, a teacher and deaf student of English in the United States might use Signed English to cite examples of English usage, but the discussion of those examples would be in American Sign Language.

Several culturally well developed sign languages are a medium for stage performances such as sign-language poetry. Many of the poetic mechanisms available to signing poets are not available to a speaking poet.

History of sign language[edit | edit source]

The written history of sign language began in the 17th century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published [Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (‘Reduction of letters and art for teaching mute people to speak’) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of Phonetics and Logopedia, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs, in form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of the mute or deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the 18th century, which has survived basically unchanged until the present time.

In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first private school for deaf children in Paris; Laurent Clerc was arguably its most famous graduate. He went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.[2] Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet founded a school for the deaf in 1857, which in 1864 became Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, the only liberal arts university for and of the deaf in the world.

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart in as much as each linguistic population will contain Deaf members who will generate a sign language. In much the same way that geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages, the same forces operate on signed languages and so they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a ‘national’ sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of residential schools for the deaf.

International Sign, formerly known as Gestuno, is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf. Recent studies claim that while International Sign is a kind of a pidgin, they conclude that it is more complex than a typical pidgin and indeed is more like a full signed language.[3]

Linguistics of sign[edit | edit source]

In linguistic terms, sign languages are as rich and complex as any oral language, despite the common misconception that they are not «real languages». Professional linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classed as true languages.[4]

Sign languages are not mime — in other words, signs are conventional, often arbitrary and do not necessarily have a visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. While iconicity is more systematic and wide-spread in sign languages than in spoken ones, the difference is not categorical.[5] Nor are they a visual rendition of an oral language. They have complex grammars of their own, and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the lofty and abstract.

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Handshape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarised in the acronym HOLME.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression and the body posture in the same moment. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Sign languages’ relationships with oral languages[edit | edit source]

A common misconception is that sign languages are somehow dependent on oral languages, that is, that they are oral language spelled out in gesture, or that they were invented by hearing people. Hearing teachers in deaf schools, such as Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, are often incorrectly referred to as “inventors” of sign language.

Manual alphabets (fingerspelling) are used in sign languages, mostly for proper names and technical or specialised vocabulary borrowed from spoken languages. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages were simplified versions of oral languages, but in fact it is merely one tool among many. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development. For example, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language.

Similarly, countries which use a single oral language throughout may have two or more sign languages; whereas an area that contains more than one oral language might use only one sign language. South Africa, which has 11 official oral languages and a similar number of other widely used oral languages is a good example of this. It has only one sign language with two variants due to its history of having two major educational institutions for the deaf which have served different geographic areas of the country.

Spatial grammar and simultaneity[edit | edit source]

Sign languages exploit the unique features of the visual medium (sight). Oral language is linear. Only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, on the other hand, is visual; hence a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously. As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, «I drove here». To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, «I drove here along a winding road,» or «I drove here. It was a nice drive.» However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb ‘drive’ by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb ‘drive’ is being signed. Therefore, whereas in English the phrase «I drove here and it was very pleasant» is longer than «I drove here,» in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

In fact, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[6]

Use of signs in hearing communities[edit | edit source]

Gesture is a typical component of spoken languages. More elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in places or situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, baseball, hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union the Referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators. Recently, there has been a movement to teach and encourage the use of sign language with toddlers before they learn to talk, because such young children can communicate effectively with signed languages well before they are physically capable of speech. This is typically referred to as Baby Sign. There is also movement to use signed languages more with non-deaf and non-hard-of-hearing children with other causes of speech impairment or delay, for the obvious benefit of effective communication without dependence on speech.

On occasion, where the prevalence of deaf people is high enough, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the USA, Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, and Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America (see Plains Indian Sign Language). It was used to communicate among tribes with different spoken languages. There are especially users today among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Telecommunications facilitated signing[edit | edit source]

One of the first demonstrations of the ability for telecommunications to help sign language users communicate with each other occurred when AT&T’s videophone (trademarked as the ‘Picturephone’) was introduced to the public at the 1964 New York World’s Fair –two deaf users were able to freely communicate with each other between the fair and another city.[7] Various organizations have also conducted research on signing via videotelephony.

Sign language interpretation services via Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) or a Video Relay Service (VRS) are useful in the present-day where one of the parties is deaf, hard-of-hearing or speech-impaired (mute). In such cases the interpretation flow is normally within the same principal language, such as French Sign Language (FSL) to spoken French, Spanish Sign Language (SSL) to spoken Spanish, British Sign Language (BSL) to spoken English, and American Sign Language (ASL) also to spoken English (since BSL and ASL are completely distinct), etc…. Multilingual sign language interpreters, who can also translate as well across principal languages (such as to and from SSL, to and from spoken English), are also available, albeit less frequently. Such activities involve considerable effort on the part of the translator, since sign languages are distinct natural languages with their own construction and syntax, different from the aural version of the same principal language.

With video interpreting, sign language interpreters work remotely with live video and audio feeds, so that the interpreter can see the deaf or mute party, and converse with the hearing party, and vice versa. Much like telephone interpreting, video interpreting can be used for situations in which no on-site interpreters are available. However, video interpreting cannot be used for situations in which all parties are speaking via telephone alone. VRI and VRS interpretation requires all parties to have the necessary equipment. Some advanced equipment enables interpreters to remotely control the video camera, in order to zoom in and out or to point the camera toward the party that is signing.

Home sign[edit | edit source]

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign).[8]

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child naturally invents signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and it comes nowhere near meeting the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence. No type of Home Sign is recognized as an official language.

Classification of sign languages[edit | edit source]

Although deaf sign languages have emerged naturally in deaf communities alongside or among spoken languages, they are unrelated to spoken languages and have different grammatical structures at their core. A group of sign «languages» known as manually coded languages are more properly understood as signed modes of spoken languages, and therefore belong to the language families of their respective spoken languages. There are, for example, several such signed encodings of English.

There has been very little historical linguistic research on sign languages, and few attempts to determine genetic relationships between sign languages, other than simple comparison of lexical data and some discussion about whether certain sign languages are dialects of a language or languages of a family. Languages may be spread through migration, through the establishment of deaf schools (often by foreign-trained educators), or due to political domination.

Language contact is common, making clear family classifications difficult — it is often unclear whether lexical similarity is due to borrowing or a common parent language. Contact occurs between sign languages, between signed and spoken languages (Contact Sign), and between sign languages and gestural systems used by the broader community. One author has speculated that Adamorobe Sign Language may be related to the «gestural trade jargon used in the markets throughout West Africa», in vocabulary and areal features including prosody and phonetics.[9]

- BSL, Auslan and NZSL are usually considered to belong to a language family known as BANZSL. Maritime Sign Language and South African Sign Language are also related to BSL.[10]

- Japanese Sign Language, Taiwanese Sign Language and Korean Sign Language are thought to be members of a Japanese Sign Language family.

- There are a number of sign languages that emerged from French Sign Language (LSF), or were the result of language contact between local community sign languages and LSF. These include: French Sign Language, Quebec Sign Language, American Sign Language, Irish Sign Language, Russian Sign Language, Dutch Sign Language, Flemish Sign Language, Belgian-French Sign Language, Spanish Sign Language, Mexican Sign Language, Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and others.

- A subset of this group includes languages that have been heavily influenced by American Sign Language (ASL), or are regional varieties of ASL. Bolivian Sign Language is sometimes considered a dialect of ASL. Thai Sign Language is a mixed language derived from ASL and the native sign languages of Bangkok and Chiang Mai, and may be considered part of the ASL family. Others possibly influenced by ASL include Ugandan Sign Language, Kenyan Sign Language, Philippine Sign Language and Malaysian Sign Language.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that Finnish Sign Language, Swedish Sign Language and Norwegian Sign Language belong to a Scandinavian Sign Language family.

- Icelandic Sign Language is known to have originated from Danish Sign Language, although significant differences in vocabulary have developed in the course of a century of separate development.

- Israeli Sign Language was influenced by German Sign Language.

- According to a SIL report, the sign languages of Russia, Moldova and Ukraine share a high degree of lexical similarity and may be dialects of one language, or distinct related languages. The same report suggested a «cluster» of sign languages centered around Czech Sign Language, Hungarian Sign Language and Slovakian Sign Language. This group may also include Romanian, Bulgarian, and Polish sign languages.

- Known isolates include Nicaraguan Sign Language, Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, and Providence Island Sign Language.

- Sign languages of Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq (and possibly Saudi Arabia) may be part of a sprachbund, or may be one dialect of a larger Eastern Arabic Sign Language.

The only comprehensive classification along these lines going beyond a simple listing of languages dates back to 1991.[11] The classification is based on the 69 sign languages from the 1988 edition of Ethnologue that were known at the time of the 1989 conference on sign languages in Montreal and 11 more languages the author added after the conference.[12]

| Primary Single |

Primary Group |

Alternative Single |

Alternative Group |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype-A |

|

|

|

|

| Prototype-R |

|

|

|

|

| BSL(bfi)-derived |

|

|

|

|

| DGS(gsg)-derived |

|

|

|

|

| JSL-derived |

|

|

|

|

| LSF(fsl)-derived |

|

|

|

|

| LSG-derived |

|

|

|

|

In his classification, the author distinguishes between primary and alternative sign languages[14] and, subcategorically, between languages recognizable as single languages and languages thought to be composite groups.[15] The prototype-A class of languages includes all those sign languages that seemingly cannot be derived from any other language. Prototype-R languages are languages that are remotely modelled on prototype-A language by a process Kroeber (1940) called «stimulus diffusion». The classes of BSL(bfi)-, DGS(gsg)-, JSL-, LSF(fsl)- and LSG-derived languages represent «new languages» derived from prototype languages by linguistic processes of creolization and relexification.[16] Creolization is seen as enriching overt morphology in «gesturally signed» languages, as compared to reducing overt morphology in «vocally signed» languages.[17]

Typology of sign languages[edit | edit source]

Linguistic typology (going back on Edward Sapir) is based on word structure and distinguishes morphological classes such as agglutinating/concatenating, inflectional, polysynthetic, incorporating, and isolating ones.

Sign languages vary in syntactic typology as there are different word orders in different languages. For example, ÖGS is Subject-Object-Verb while ASL is Subject-Verb-Object. Correspondance to the surrounding spoken languages is not improbable.

Morphologically speaking, wordshape is the essential factor. Canonical wordshape results from the systematic pairing of the binary values of two features, namely syllabicity (mono- or poly-) and morphemicity (mono- or poly-). Brentari[18][19] classifies sign languages as a whole group determined by the medium of communication (visual instead of auditive) as one group with the features monosyllabic and polymorphemic. That means, that via one syllable (i.e. one word, one sign) several morphemes can be expressed, like subject and object of a verb determine the direction of the verb’s movement (inflection). This is necessary for sign languages to assure a comparible production rate to spoken languages, since producing one sign takes much longer than uttering one word — but on a sentence to sentence comparison, signed and spoken languages share approximately the same speed.[20]

Written forms of sign languages[edit | edit source]

Sign language differs from oral language in its relation to writing. The phonemic systems of oral languages are primarily sequential: that is, the majority of phonemes are produced in a sequence one after another, although many languages also have non-sequential aspects such as tone. As a consequence, traditional phonemic writing systems are also sequential, with at best diacritics for non-sequential aspects such as stress and tone.

Sign languages have a higher non-sequential component, with many «phonemes» produced simultaneously. For example, signs may involve fingers, hands, and face moving simultaneously, or the two hands moving in different directions. Traditional writing systems are not designed to deal with this level of complexity.

Partially because of this, sign languages are not often written. Most deaf signers read and write the oral language of their country. However, there have been several attempts at developing scripts for sign language. These have included both «phonetic» systems, such as HamNoSys (the Hamburg Notational System) and SignWriting, which can be used for any sign language, and «phonemic» systems such as the one used by William Stokoe in his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language, which are designed for a specific language.

These systems are based on iconic symbols. Some, such as SignWriting and HamNoSys, are pictographic, being conventionalized pictures of the hands, face, and body; others, such as the Stokoe notation, are more iconic. Stokoe used letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals to indicate the handshapes used in fingerspelling, such as ‘A’ for a closed fist, ‘B’ for a flat hand, and ‘5’ for a spread hand; but non-alphabetic symbols for location and movement, such as ‘[]’ for the trunk of the body, ‘×’ for contact, and ‘^’ for an upward movement. David J. Peterson has attempted to create a phonetic transcription system for signing that is ASCII-friendly known as the Sign Language International Phonetic Alphabet (SLIPA).

SignWriting, being pictographic, is able to represent simultaneous elements in a single sign. The Stokoe notation, on the other hand, is sequential, with a conventionalized order of a symbol for the location of the sign, then one for the hand shape, and finally one (or more) for the movement. The orientation of the hand is indicated with an optional diacritic before the hand shape. When two movements occur simultaneously, they are written one atop the other; when sequential, they are written one after the other. Neither the Stokoe nor HamNoSys scripts are designed to represent facial expressions or non-manual movements, both of which SignWriting accommodates easily, although this is being gradually corrected in HamNoSys.

Primate use of sign language[edit | edit source]

There have been several notable examples of scientists teaching non-human primates basic signs in order to communicate with humans.[21] Notable examples are:-

- Chimpanzees: Washoe and Loulis

- Gorillas: Michael and Koko.

Gestural theory of human language origins[edit | edit source]

The gestural theory states that vocal human language developed from a gestural sign language.[22] An important question for gestural theory is what caused the shift to vocalization.[23]

Media[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ This inclusion of the Warlpiri Sign Language (and other aboriginal sign languages) among the Manually Coded Languages, based on the presumption that natural sign languages can only develop in deaf communities, is now widely disputed (Madell 1998, O’Reilly 2005). As to their use in deaf communities, the 2008 version of the 15th edition of Ethnologue reports that «several such sign languages are also used by deaf persons.»[1]

- ↑ Canlas (2006).

- ↑ Cf. Supalla, Ted & Rebecca Webb (1995). «The grammar of international sign: A new look at pidgin languages.» In: Emmorey, Karen & Judy Reilly (eds). Language, gesture, and space. (International Conference on Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research) Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, pp. 333-352; McKee R. & J. Napier J. (2002). «Interpreting in International Sign Pidgin: an analysis.» Journal of Sign Language Linguistics 5(1).

- ↑ This latter conception is no longer disputed as can be seen from the fact that sign language experts are mostly linguists.

- ↑ Johnston (1989).

- ↑ Nakamura (1995).

- ↑ Bell Laboratories RECORD (1969) A collection of several articles on the AT&T Picturephone (then about to be released) Bell Laboratories, Pg.134-153 & 160-187, Volume 47, No. 5, May/June 1969;

- ↑ Susan Goldin-Meadow (Goldin-Meadow 2003, Van Deusen, Goldin-Meadow & Miller 2001) has done extensive work on home sign systems. Adam Kendon (1988) published a seminal study of the homesign system of a deaf Enga woman from the Papua New Guinea highlands, with special emphasis on iconicity.

- ↑ Frishberg (1987). See also the classification of Wittmann (1991) for the general issue of jargons as prototypes in sign language glottogenesis.

- ↑ See Gordon (2008), under nsr[2] and sfs[3].

- ↑ Henri Wittmann (1991). The classification is said to be typological satisfying Jakobson’s condition of genetic interpretability.

- ↑ Wittmann’s classification went into Ethnologue’s database where it is still cited.[4] The subsequent edition of Ethnologue in 1992 went up to 81 sign languages and ultimately adopting Wittmann’s distinction between primary and alternates sign langues (going back ultimately to Stokoe 1974) and, more vaguely, some other of his traits. The 2008 version of the 15th edition of Ethnologue is now up to 124 sign languages.

- ↑ To the extent that Wittmann’s language codes are different from SIL codes, the latter are given within parentheses

- ↑ Wittmann adds that this taxonmic criteron is not really applicable with any scientific rigor: Alternative sign languages, to the extent that they are full-fledged natural languages (and therefore included in his survey), are mostly used by the deaf as well; and some primary sign languages (such as ASL(ase) and ADS) have acquired alternative usages.

- ↑ Wittmann includes in this class ASW (composed of at least 14 different languages), MOS(mzg), HST (distinct from the LSQ>ASL(ase)-derived TSQ) and SQS. In the meantime since 1991, HST has been recognized as being composed of BFK, CSD, HAB, HAF, HOS, LSO.

- ↑ Wittmann’s references on the subject, besides his own work on creolization and relexification in «vocally signed» languages, include papers such as Fischer (1974, 1978), Deuchar (1987) and Judy Kegl’s pre-1991 work on creolization in sign languages.

- ↑ Wittmann’s explanation for this is that models of acquisition and transmission for sign languages are not based on any typical parent-child relation model of direct transmission which is inducive to variation and change to a greater extent. He notes that sign creoles are much more common than vocal creoles and that we can’t know on how many successive creolizations prototype-A sign languages are based prior to their historicity.

- ↑ Brentari, Diane (1998): A prosodic model of sign language phonology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; cited in Hohenberger (2007) on p. 349

- ↑ Brentari, Diane (2002): Modality differences in sign language phonology and morphophonemics. In: Richard P. Meier, kearsy Cormier, and David Quinto-Pozocs (eds.), 35-36; cited in Hohenberger (2007) on p. 349

- ↑ Hohenberger, Annette: The possible range of variation between sign languages: Universal Grammar, modality, and typological aspects; in: Perniss, Pamela M., Roland Pfau and Markus Steinbach (Eds.): Visible Variation. Comparative Studies on Sign Language Structure; (Reihe Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM] 188). Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter 2007

- ↑ Premack & Pemack (1983), Premack (1985), Wittmann (1991).

- ↑ Hewes (1973), Premack & Premack (1983), Kimura (1993), Newman (2002), Wittmann (1980, 1991)

- ↑ Kolb & Whishaw (2003)

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

- Aronoff, Mark, Meir, Irit & Wendy Sandler (2005). «The Paradox of Sign Language Morphology.» Language 81 (2), 301-344.

- Branson, J., D. Miller, & I G. Marsaja. (1996). «Everyone here speaks sign language, too: a deaf village in Bali, Indonesia.» In: C. Lucas (ed.): Multicultural aspects of sociolinguistics in deaf communities. Washington, Gallaudet University Press, pp. 39-5.

- Canlas, Loida (2006). «Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World.» The Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University.[5]

- Deuchar, Margaret (1987). «Sign languages as creoles and Chomsky’s notion of Universal Grammar.» Essays in honor of Noam Chomsky, 81-91. New York: Falmer.

- Emmorey, Karen; & Lane, Harlan L. (Eds.). (2000). The signs of language revisited: An anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-3246-7.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1974). «Sign language and linguistic universals.» Actes du Colloque franco-allemand de grammaire générative, 2.187-204. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1978). «Sign languages and creoles.» Siple 1978:309-31.

- Frishberg, Nancy (1987). «Ghanaian Sign Language.» In: Cleve, J. Van (ed.), Gallaudet encyclopaedia of deaf people and deafness. New York: McGraw-Gill Book Company.

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, 2003, The Resilience of Language: What Gesture Creation in Deaf Children Can Tell Us About How All Children Learn Language, Psychology Press, a subsidiary of Taylor & Francis, New York, 2003

- Gordon, Raymond, ed. (2008). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th edition. SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6, ISBN 1-55671-159-X. Web version.[6] Sections for primary sign languages[7] and alternative ones[8].

- Groce, Nora E. (1988). Everyone here spoke sign language: Hereditary deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27041-X.

- Healy, Alice F. (1980). Can Chimpanzees learn a phonemic language? In: Sebeok, Thomas A. & Jean Umiker-Sebeok, eds, Speaking of apes: a critical anthology of two-way communication with man. New York: Plenum, 141-143.

- Hewes, Gordon W. (1973). «Primate communication and the gestural origin of language.» Current Anthropology 14.5-32.

- Johnston, Trevor A. (1989). Auslan: The Sign Language of the Australian Deaf community. The University of Sydney: unpublished Ph.D. dissertation.[9]

- Kamei, Nobutaka (2004). The Sign Languages of Africa, «Journal of African Studies» (Japan Association for African Studies) Vol.64, March, 2004. [NOTE: Kamei lists 23 African sign languages in this article].

- Kegl, Judy (1994). «The Nicaraguan Sign Language Project: An Overview.» Signpost 7:1.24-31.

- Kegl, Judy, Senghas A., Coppola M (1999). «Creation through contact: Sign language emergence and sign language change in Nicaragua.» In: M. DeGraff (ed), Comparative Grammatical Change: The Intersection of Language Acquisistion, Creole Genesis, and Diachronic Syntax, pp.179-237. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kegl, Judy (2004). «Language Emergence in a Language-Ready Brain: Acquisition Issues.» In: Jenkins, Lyle, (ed), Biolinguistics and the Evolution of Language. John Benjamins.

- Kendon, Adam. (1988). Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kimura, Doreen (1993). Neuromotor Mechanisms in Human Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- Kolb, Bryan, and Ian Q. Whishaw (2003). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 5th edition, Worth Publishers.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1940). «Stimulus diffusion.» American Anthropologist 42.1-20.

- Krzywkowska, Grazyna (2006). «Przede wszystkim komunikacja», an article about a dictionary of Hungarian sign language on the internet Template:Pl icon.

- Lane, Harlan L. (Ed.). (1984). The Deaf experience: Classics in language and education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19460-8.

- Lane, Harlan L. (1984). When the mind hears: A history of the deaf. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-50878-5.

- Madell, Samantha (1998). Warlpiri Sign Language and Auslan — A Comparison. M.A. Thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.[10]

- Nakamura, Karen (1995). «About American Sign Language.» Deaf Resourec Library, Yale University.[11]

- Newman, A. J., et al. (2002). «A Critical Period for Right Hemisphere Recruitment in American Sign Language Processing». Nature Neuroscience 5: 76–80.

- O’Reilly, S. (2005). Indigenous Sign Language and Culture; the interpreting and access needs of Deaf people who are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in Far North Queensland. Sponsored by ASLIA, the Australian Sign Language Interpreters Association.

- Padden, Carol; & Humphries, Tom. (1988). Deaf in America: Voices from a culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19423-3.

- Poizner, Howard; Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1987). What the hands reveal about the brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Premack, David, & Ann J. Premack (1983). The mind of an ape. New York: Norton.

- Premack, David (1985) «‘Gavagai!’ or the future of the animal language controversy». Cognition 19, 207-296

- Sacks, Oliver W. (1989). Seeing voices: A journey into the world of the deaf. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06083-0.

- Sandler, Wendy (2003). Sign Language Phonology. In William Frawley (Ed.), The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Linguistics.[12]

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2001). Natural sign languages. In M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), Handbook of linguistics (pp. 533-562). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20497-0.

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Stiles-Davis, Joan; Kritchevsky, Mark; & Bellugi, Ursula (Eds.). (1988). Spatial cognition: Brain bases and development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0046-8; ISBN 0-8058-0078-6.

- Stokoe, William C. (1960, 1978). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in linguistics, Occasional papers, No. 8, Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo. 2d ed., Silver Spring: Md: Linstok Press.

- Stokoe, William C. (1974). Classification and description of sign languages. Current Trends in Linguistics 12.345-71.

- Van Deusen-Phillips S.B., Goldin-Meadow S., Miller P.J., 2001. Enacting Stories, Seeing Worlds: Similarities and Differences in the Cross-Cultural Narrative Development of Linguistically Isolated Deaf Children, Human Development, Vol. 44, No. 6.

- Wittmann, Henri (1980). «Intonation in glottogenesis.» The melody of language: Festschrift Dwight L. Bolinger, in: Linda R. Waugh & Cornelius H. van Schooneveld, 315-29. Baltimore: University Park Press.[13]

- Wittmann, Henri (1991). «Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement.» Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée 10:1.215-88.[14]

External links[edit | edit source]

Note: the articles for specific sign languages (e.g. ASL or BSL) may contain further external links, e.g. for learning those languages.

- American Sign Language (ASL) resource site.

- A DeafWiki free-content encyclopedia of deaf and hard hearing

- Signes du Monde, directory for all online Sign Languages dictionaries {{{1}}} / {{{1}}}

- List Serv for Sign Language Linguistics

- The MUSSLAP Project Multimodal Human Speech and Sign Language Processing for Human-Machine Communication.

- Publications of the American Sign Language Linguistics Research Project

- Sign language among North American Indians compared with that among other peoples and deaf-mutes, by Garrick Mallery from Project Gutenberg. A first annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879–1880

- Pablo Bonet, J. de (1620) [Reduction de las letras y Arte para enseñar á ablar los Mudos Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)], Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (BNE).

All of us have a unique way to communicate in order to navigate the world around us and interpret life.

Even though speaking is considered the most common language mode among people, not everyone is able to exercise it. There are over 10 million individuals across Pakistan who live with some level of hearing loss. For someone who maintains the condition of deafness and can’t hear sound, the use of auditory language to exchange information is a no-way. A large number of the population is disconnected from the mainstream hearing-dominated society and lie at the risk of being marginalised, because people who are limited to using only speech can’t communicate with them. A lack of accessibility to support the conversation between both communities also adds to the problem.

Because of this, a huge challenge in the form of a communication gap between D/deaf, hard of hearing, and hearing people arises. To bridge this gap, a non-verbal language known as sign language exists.

So, you must now be wondering, what exactly is this sign language?

1. Sign language is a natural and visual form of language that uses movements and expression to convey meaning between people.

Sign language is a non-verbal language that Deaf persons exclusively count on to connect with their social environment. It is based on visual cues through the hands, eyes, face, mouth, and body. The gestures or symbols in sign language are organised in a linguistic way. It is a rich combination of finger-spelling, hand gestures, body language, facial expressions, timing, touch, and anything else that communicates thoughts or ideas without the use of speech.

Deaf people are the main users of sign language. Some hard of hearing people use it as a handy means of communication too. It is also used by those hearing individuals who can’t use speech, be it due to a disability or condition, or by those who have Deaf family members, and used even sometimes by monks who have taken a vow of silence.

2. No person or committee invented sign language.

No one knows for sure when the first Deaf person tried out visual gestures to express themselves. Many sources agree that using hand gestures and body language is one of the oldest and most basic forms of human communication, and it has been around just as long as spoken language.

The first written document of sign language is said to have come from Plato from Ancient Greece. In his Cratylus, he recorded Socrates saying:

If we had neither voice nor tongue, and yet wished to manifest things to one another, should we not, like those which are at present mute, endeavour to signify our meaning by our hands, head, and other parts of the body?

Native Americans also used sign language to communicate with other ethnic groups who spoke different languages. Even long after the European conquest, this system was in use. Another example is the case of a rare ethnic group that carried genes for deafness. Their island was isolated, so the trait spread among the locals at speed and a great population of Deaf people was formed. A local deaf culture developed and sign language arose so that the deaf could communicate with each other.

In South Asian literature history, there are hardly any mention of sign languages and Deaf people. If there are some, they all date back to ancient times. In religious subjects, symbolic hand gestures have been used for many centuries, but their customs often excluded Deaf participation. Classical Indian dance and theatre also sometimes uses hand and arm gestures that have specific meanings.

In the Hidayah, a 12th century Islamic legal commentary, there was a reference to visual signals used by Deaf people for communication. Deaf people were acknowledged to have legal standing in areas like bequests, marriage, divorce, and financial transactions if they could communicate with understandable signs.

Some say today that sign language came into form more than 200 years ago through the mixture of different cultures and local sign languages. As time went on, the mixed form changed into a vibrant, complex, and mature language in every region.

3. Different countries have different sign languages.

There are several thousand spoken languages across the world and all are different from each other in one sense or the other. In the same way, sign language has hand gestures and visual representations of many different types.

There is Pakistani Sign Language (PSL), American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL), French Sign Language (LSF), Indian Sign Language (ISL), and so on. American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) are both based on English language. Pakistani Sign Language (PSL) and Indian Sign Language (ISL) are also well-known sign languages in the South Asian region.

There are many varieties of sign language in the region, including several subsets of home and local sign languages. There is difference in the flow of signing, pronunciation, slang, and some gestures. These local signs also have distinct accents and dialects, similar to how certain English or Urdu words are spoken differently in separate parts of the country.

4. Sign language is different from spoken language.

Every language, whether verbal or non-verbal, has their own elements and functions and differ from each other in how they are used.

Even though sign language is another means of communication and also has every basic feature of language, it is still different from spoken language in many ways.

You can express your thoughts and ideas in sign language in different forms, just as you can with other languages like Urdu or English. Unlike in spoken languages where speakers may convey meaning by using their voice, sign language users may use hand gestures and facial expression to send a visual signal, use signs to wave hello or goodbye to someone, or point to something they want and use body language to emphasise any idea.

5. Sign languages have their own grammar.

It is said that sign languages are the manual representation of spoken languages, but that’s not true. In reality, both language modes have their own grammar structure, vocabulary, and syntax. The grammars of these visual and gesture-based sign languages are unlike the grammars of sound-based or written languages.

Unlike in spoken languages where grammar is expressed through sound-based signifiers for tense, aspect, mood and syntax (the way we organise individual words), sign languages use hand movements, sign order, as well as body and facial cues to create grammar. In ASL, certain mouth and eye movements act as adjectival or adverbial modifiers.

That is because gesture-based languages are concerned with appearance and concepts, whereas spoken and written languages are more about grammar rules.

6. Children learn sign languages the same way they learn spoken languages.

Parents are usually the power source of a child’s early language learning. Children learn how to do signs from a young age and as natural as they do with any spoken languages. There are also important sign language stages and baby babble. When babies are learning the visual language, they babble with their hands and over time, learn how to better express their signs.

If a hearing child is born to parents who are deaf and use sign language, the child will catch the mechanism the same way they would if the parents used a spoken language, and become fluent sign language users.

On the other hand, if a Deaf child has hearing parents, the learning of sign language may be different. In fact, studies suggest that 9 out of 10 children who are deaf are born to hearing parents. Some hearing parents are reluctant to introduce sign language to their Deaf child. Some of them who do choose to, they learn it along with their Deaf child so that they could communicate with them. Sometimes, the child may only learn sign language through their deaf peers, other Deaf family members, or community people.

7. Sign language is a visual language.

We all already know this fact, but it’s important to emphasise. Sign language may be like any other language in many ways and should be valued as such, but it’s also different.

Sign language is expressive and artistic in comparison to a spoken language’s auditory nature. The gestures of hands and body, facial expressions, and finger-spelling breathe life into its visual spirit. Sign language may be an animated way to convey meaning, but it can be quite easy and formal, as best shown in our video here:

Communication in sign language is like a dramatic arts performance − the rhythm of words, expressive facial cues, the little pauses in between, the breath intake, the emphasis and melody, body language, and head and hands gestures.

It is beautiful not only because it shows us what sign language has the power to do, but because it shows us what language does.

Want to learn sign language? You can easily learn the basics online from here.

Sign language is a natural language of expression and gestural-spatial configuration and visual perception (or even tactile by certain people with deaf blindness), thanks to which deaf people can establish a communication channel with their social environment, whether made up of other deaf individuals or anyone who knows the sign language used. While with oral language communication is established in a vocal-auditory channel, sign language does so through a gesture-visual-spatial channel. Sign language with origin and classification

Definitions of Sign

- Note, sign, or gesture to convey something or come to know it.

- That which in concert is determined between two or more people to understand each other.

- Sign or means that is used to later remember something.

- Vestige that remains of something and remembers it.

- Indication of someone’s place and address.

- Characteristic features of a person that allow distinguishing it from others.

- State your individual circumstances; Describe them in a way that can be distinguished from something else.

- Explain, make yourself understood through gestures.

Origin of sign languages

The history of sign language is as old as that of mankind. In fact, it has been and continues to be used by listening communities. For example, the Amerindians of the Great Plains region of North America used sign language to make themselves understood among ethnic groups speaking different languages, and this system was in use long after the European conquest. Another example is the case of a unique tribe in which the majority of its members were deaf due to inheritance. Then, sign language was used that became in general use, also among listeners, until the beginning of the 20th century. However, there are no documentary references to these languages before the 17th century. Sign language with origin and classification

One of the first written documents dealing with sign languages is Plato’s Cratylus, where he says that if we had neither the tongue nor the voice, we would try to communicate, like the mute, through signs of the hand, the head, and whole body.

During the Middle Ages, sign language was mainly used in abbeys by monks. In the 16th century, Pedro Ponce de León, a Spanish Benedictine monk considered the first “teacher for the deaf” created a school for the deaf in the San Salvador monastery in Oña (Castilla y León). It used a manual alphabet based on the monastic sign languages used by monks who had taken a vow of silence.

In 1620, Juan de Pablo Bonet published the Reduction of letters and art to teach the mute in Madrid to speak. This work will be considered as the first modern treatise on phonetics in sign language that establishes an oral teaching method for the deaf and also a manual alphabet.

At the same time in Great Britain, manual alphabets were used in different areas such as secret communication, speaking in front of an audience but also for the communication of deaf and dumb people.

With the passage of time, other schools and institutions were created in the rest of Europe and the world (France, Italy, United States,…).

Nowadays, there are several sign languages that differ from each other both in the lexicon (set of signs or gestural signs) and in grammar, and which originate from the French, British, and German sign languages, among others. Since the 1980s, several specialists and sociologists have become much more interested in sign language, which is finally recognized as a “full-fledged” language in various countries of the world.

Source of Sign Language

Even though sign languages are currently used almost exclusively among deaf people, their origin is as old as oral languages or even older, in the history of the appearance of Humanity, and they have also been and continue to be used by community listeners.

One of the best-known systems were those created by the Indians of North America as a communication system between tribes that did not maintain the same language. Each tribe had its own signs to indicate the rivers, mountains, and places that were closest to them. Thus, they moved their hands with a tremor in front of the body to indicate the sensation of cold; the same sign was used for winter and for the year because the North American Indians counted the years by winters. Their system was so rich that they could carry on a conversation only by gestures. Sign language with origin and classification

Sign language classification

Many of the modern sign languages can be classified into sign language families:

- Languages originating from the old French Sign Language. These languages date back to the standardized forms of sign languages used in Italy and France from the 17th century and especially from the 18th century on in the education of the deaf.

- Iberian sign languages, which show similarities to the old French sign language but whose origin is not well known.

- Languages originated from the British Sign Language (BSL), which diversified during the 19th century giving rise to the Australian Sign Language or Auslan, the New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), and the Northern Irish Sign Language.

- Languages originating from the German Sign Language (DGS), which is considered to be related to the Sign Language of German Switzerland (DSGS), the Austrian Sign Language (ÖGS), and probably the Israeli Sign Language (ISL).

- Languages originating from the ancient Kentish Sign Language used during the 17th century.

Sign Language and Linguistics

The scientific study of sign languages has revealed that they have all the properties and complexities of any natural oral language. Despite the widespread and erroneous conception that they are artificial languages.

Specifically, the following facts have been found regarding sign languages that provide the necessary linguistics to classify them as natural languages: