This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

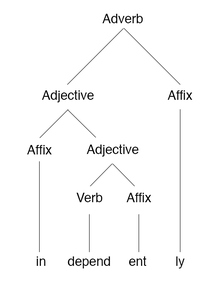

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

| School of Computer Science |

Dr Peter Coxhead

Warning: This web page was originally constructed to help computer science students who were taking my module on natural language processing. Some terms may be used differently by different authors. Unless otherwise stated, definitions are based on the English language.

If you find any errors, please e-mail me at peter.coxhead@bcs.org.

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

U |

V |

W |

X |

Y |

Z

A

accusative See case.

active An active sentence is one which has a basic pattern like the man is running or the dog bit the cat, i.e. it describes what one thing (the subject) does, often to another thing (the object). The verb in an active sentence can be said to be in the active voice. See also passive.

adjective A word which qualifies or further describes a noun or noun phrase. Examples are colourless and green which qualify ideas in Colourless green ideas sleep furiously. Adjectives can also appear after verbs like be, e.g. The apples were green.

adjunct theta-role See theta role.

adverb A word which qualifies or further describes a verb, adjective or adverb. Examples are furiously which qualifies the verb sleep in Colourless green ideas sleep furiously, or intensely which qualifies stared in He stared at me intensely. Adverbs can also qualify adjectives, e.g. astonishingly qualifies the adjective vivid in an astonishingly vivid colour, or other adverbs, e.g. extremely qualifies the adverb slowly in the phrase extremely slowly. Many English adverbs are formed from an adjective plus the ending -ly. Words like very, which can only qualify adjectives or adverbs but not verbs, are sometimes called adverbs, but are perhaps best put in a separate category.

affix An affix is a morpheme which is added to a root morpheme in the formation of a word. In its broadest sense, an affix can be a prefix, a suffix, or an infix. More narrowly, infixes are sometimes treated separately. See also morphology.

affricative An affricative is a phone which can be thought of as a very rapid, blended sequence of a stop and a fricative. The stop and fricative must be produced in a very similar positions in the mouth. An English example is the ‘ch sound’ in choose, which is like a sequence of a ‘t sound’ (a stop) and a ‘sh sound’ (a fricative). The phrases white shoes and why choose? sound very similar when spoken rapidly (but only in those dialects of English in which the [t] is not replaced by a glottal stop). In the IPA an affricative is represented by the corresponding stop symbol followed by the fricative symbol. It is important to note that the two symbols represent a SINGLE phone.

Agent See theta role.

agreement The syntax of a natural language often requires some words in a sentence to share certain grammatical features, which can show up as changes in the morphology of the words. This is called agreement; the words are said to agree in the relevant feature(s). For example, in English, determiners and nouns must agree in number within a noun phrase. Thus this cat is acceptable since this and cat are singular, but these cat is unacceptable since these is plural but cat is singular.

allophone Each of the set of phones which correspond to a single phoneme of a language is called an allophone. Allophones of the same phoneme generally occur in different contexts and never distinguish one word from another. As an example, the ‘t sounds’ in tea and tree constitute allophones of one English /t/ phoneme. The production of the two sounds differs in that speaker’s tongue is in a slightly different place. A speech spectrograph will show a resulting sound difference. However, no English words differ ONLY in the substitution of one of these ‘t sounds’ for the other. Allophones are written in square brackets (e.g. [t]) where it is necessary to distinguish them from phonemes (e.g. /t/).

alveolar A phone produced when the tongue touches the tooth ridge behind the teeth (alveolus). See the diagram of a head for the location of the tooth ridge. The ‘t sound’ in English is an alveolar stop, produced by stopping and then releasing the air flow out of the mouth by closing the tongue onto the tooth ridge.

anaphora Some words in a sentence have little or no meaning of their own but instead refer to other words in the same or other sentences. This process is called anaphora. Pronouns are a good example. Consider the sentences: London had snow yesterday. It fell to a depth of a metre. To understand the second sentence it is necessary to identify it with snow rather than London or yesterday. English allows various forms of anaphora with verbs. For example, in I wanted to finish today, but I couldn’t do it, the words do it refer to finish today and hence can be called anaphoric.

approximant An approximant is a phone in which the tongue partly closes the airway, but not enough to cause a fricative. Examples in English are the phones that begin lap and woo. Approximants can be divided into liquids and glides. Approximants (especially glides) have some similarities to vowels.

argument theta-role See theta role.

article In English, a / an and the are called the indefinite and definite articles respectively. See also determiner.

aspect (of a verb) Verbs can show not only the time location of an action (by grammatical tense), but also features such as whether the action is thought of as completed or continuing. A change in a verb which shows such a feature is often called an aspect of the verb. Compare ate with was eating in He ate rapidly when I came in and He was eating rapidly when I came in. Both refer to events in the past time; the difference lies in the implied relationship between the actions of ‘eating’ and ‘coming in’. Syntactically, English has two marked aspects: progressive and perfect. The progressive aspect is formed by using the auxiliary be and the verb ending -ing. For example, I am eating it now implies both that the time is the present and that the ‘eating’ is currently in progress. The perfect aspect is formed by using the auxiliary have and the appropriate verb ending (usually -en or -ed): e.g. I have eaten it now, which implies both that the time is the present and that the ‘eating’ is finished. An English verb can show no aspect (e.g. runs or ran), progressive aspect (e.g. is running or was running), perfect aspect (e.g. has run or had run) or both perfect and progressive aspects (e.g. has been running or had been running). The table below shows the possible combinations of tense and aspect in English verbs.

| Tense | |||

| Present | Past | ||

| Aspect | None | I run | I ran |

| Progressive | I am running | I was running | |

| Perfect | I have run | I had run | |

| Perfect Progressive | I have been running | I had been running |

aspiration If a phone is accompanied by a ‘puff of air’ it can be said to be aspirated. The ‘p sound’ in the English word pit is aspirated and is thus slightly different from the ‘p sound’ in spit, which is not aspirated.

assimilation Particularly in rapid speech there is a tendency for neighbouring phones to become more similar, presumably to make pronunciation easier. For example, although the words Aston and Asda are both written with an s, the second word is normally pronounced as if spelt Azda. The reason seems to be that [s] and [t] are both voiceless, whereas [z] and [d] are both voiced. The sequence fricative followed by stop is easier to say if both have the same voicing.

ATN = Augmented Transition Network.

auxiliary In English, one of a small set of verb-like words which can precede a main verb in a verb phrase. The auxiliaries and verbs are sometimes said to form a ‘verb group’ or ‘compound verb’. Examples of auxiliaries are do in I really do not know, or may in I may see him tomorrow. Auxiliaries have verb-like properties, and may show changes in number, person and tense. Some words (e.g. have) can be either an auxiliary (e.g. I have seen him) or a verb (e.g. I have a car).

B

bilabial A phone produced by the closure or partial closure of both lips. See the diagram of a head. The English sounds represented by the letters p in pit and b in bad are bilabial stops, produced by stopping and then releasing the air flow out of the mouth by closing the lips. Bilabial and labiodental phones are together classed as labial.

C

case Nouns, noun phrases and pronouns play different syntactic roles in sentences. These roles correspond to changes of case in many languages. Consider, for example, the sentences She saw him and He saw her. The words she and he are used when they form the subject of the sentence and are said to be in the nominative case. She and he must be changed to her and him respectively when they form the object of the sentence and are said to be in the accusative case. Changes due to case are restricted to pronouns in English, but in other languages (e.g. Russian, Modern Greek), most nouns, pronouns, articles, adjectives, etc. will vary according to case.

circumstantial theta-role See theta role.

consonant (1) A phone which is produced other than by allowing lung air to pass over the vibrating vocal cords and then freely out of the mouth, i.e. a phone other than a vowel. Consonants include stops, fricatives, affricatives and approximants. (2) A letter of the alphabet usually pronounced using a consonant phone is also called a consonant.

Be careful to distinguish these two usages. In a language with non-phonemic spelling, such as English, they can be quite different. The word mute, for example, begins with a single consonant letter, but in many British English dialects is pronounced with two opening consonant phones ([m] and [j] in IPA).

D

dental A phone produced when the tongue touches the teeth. See the diagram of a head. The English sounds beginning the words this and think are alveolar fricatives, produced by partially stopping the air flow out of the mouth by touching the tongue on the teeth.

derivational morphology See morphology.

determiner (det) The definite and indefinite articles plus a small set of other similar words (e.g. genitive pronouns) which qualify nouns or noun phrases can be grouped as determiners. Examples of determiners are this, that, my. An English noun phrase always contains at most one determiner; singular noun phrases generally require exactly one determiner. Semantically, they determine that a particular instance of the noun is being referred (back) to. For example, There’s a man at the door — the word a introduces a man into the conversation. Tell the man I’ll come in a minute — the word the refers back to the previously mentioned man.

Noun phrases in the genitive act as determiners. Thus in I saw the old lady’s cat, the genitive noun phrase the old lady’s can be replaced by the single word determiner her.

dialect Generally dialects of a language are more similar than different languages. However, what is a dialect and what is a language is often a political rather than a linguistic question. The division of Serbo-Croat, the common language of former Yugoslavia, into two languages, Serbian and Croatian, shows this rather sharply. A further example of very similar languages which might be called dialects of the same language are Dutch (spoken in the Netherlands) and Flemish (spoken in north-western Belgium). On the other hand, in China there are languages which are mutually un-intelligible when spoken but are often called dialects of one Chinese language. It is important to note that although some dialects have more social prestige in a country than others, this says nothing about their linguistic qualities.

diphthong If the tongue moves significantly during the production of a vowel phone, the result is a diphthong. A diphthong sounds like a rapid, blended sequence of two separate vowels. An example in English is the vowel sound in the word kite, which is like a rapid combination of a kind of ‘a sound’ and a kind of ‘i sound’. In the IPA a diphthong is represented by two vowel symbols. It is important to note that the two symbols represent a SINGLE phone.

direct object See object.

E

ellipsis A technical term for leaving out words in sentences. For example, in Brian ate the ice-cream and Judy the peaches, there is ellipsis, since the word ate is omitted after Judy.

F

feature See semantic feature. (There are other uses of the term not covered here.)

feminine See gender.

fricative If during the production of a phone, air is made to pass through a narrow passage, a ‘friction’ sound or fricative is produced (i.e. a more-or-less ‘hissing’ sound). English examples are the ‘f sound’ in fee or the ‘sh sound’ in she.

G

gender In some languages (but not English), nouns fall into a small number of classes which require changes in the articles, adjectives, etc. which qualify them. In Indo-European languages, these classes are traditionally called genders and labelled according to whether nouns for males (masculine gender), females (feminine gender) or neither (neuter gender) fall into these classes. French has two genders, masculine and feminine, shown for example by the use of le or la for the; German and Modern Greek have three genders, having neuter as well. Note that grammatical gender is not tied to biological sex, since, for example, the nouns meaning ‘a young girl’ are neuter in both German and Modern Greek. Thus as with number, grammatical gender is not the same as semantic gender.

genitive See also case. Genitive is an alternative word for possessive, i.e. the genitive case marks the noun or pronoun as the possessor of something. In English, the genitive case of a noun is shown in writing by adding an s together with an appropriately positioned apostrophe. Thus of the boy becomes boy’s, of the boys becomes boys’. The genitive or possessive pronouns are my, your, his, her, its [without an apostrophe!], our, their. Genitive noun phrases act as determiners.

glide A glide is an approximant in which the tongue and lips move during the production of the sound. English examples are the initial phones in woo [w] and you [j].

glottal A phone produced by closing or partially closing the vocal cords (or glottis). See the diagram of a head for the location of the vocal cords. The ‘h sound’ in English is a glottal fricative, produced by a strong air flow over partially open vocal cords.

grammar (1) The word grammar is used as a collective word for morphology and syntax, i.e. for patterns both within and between words.

grammar (2) The word grammar is also used a technical term for a rule-based approach which generates a particular set of sentences. Formally, a grammar consists of a set of nonterminal symbols (one of which is the start symbol), a set of terminal symbols and a set of productions or re-writing rules. Terminals (e.g. words) are the basic units of the sentences which the grammar generates. Nonterminals are symbols used only in the grammar itself. A production is a rule which says that the symbols on the left-hand side can be re-written as those on the right-hand side. One of the nonterminals must be the start symbol, i.e. the symbol from which re-writing starts.

grapheme A grapheme is a ‘spelling unit’. For example, in Spanish the combination ll represents a different sound from a single l. Thus these are two graphemes. In English, graphemes may be quite complex. For example -tion behaves more-or-less as a single grapheme in words like function.

H

I

idiolect The language used by one individual is sometimes called an idiolect. A dialect or language can then be regarded as a collection of mutually intelligible idiolects.

indirect object See object.

Indo-European Linguists divide languages into a number of families, based on similarity and shared descent. Indo-European languages were natively spoken in a broad band through Europe to northern India and Bangladesh. Historically, the only major non-Indo-European languages spoken in this area were Finnish/Estonian, Hungarian, Basque and Turkish. It is believed that all the Indo-European languages are descended from one language spoken around 4,000 BC. It is important to be aware that different language families may be based on quite different principles, both in their sounds and in their grammar.

infix A strong definition of an infix might be a morpheme which is added inside a root morpheme in the formation of a word. In a language like English, infixes, so defined, do not occur, since the root morpheme is indivisible. In Semitic languages, the root morpheme consists only of consonants — usually three in, e.g., Arabic or Hebrew. A particular set of vowels and/or affixes combines with this root to form a word. Thus in Hebrew the root sgr has a basic meaning connected with «close» or «closed». Adding the vowels -a-a- (where the dashes mark the position of the root consonants) forms the active verb sagar; adding the prefix ni and the vowel —a- forms the passive verb nisgar. The inserted components can be called infixes, so that nisgar = prefix ni + infix —a- + root sgr.

A weaker definition of an infix might be one or more morphemes which are added inside a word to form another word. Such infixes are said to occur in English since, in colloquial speech, swear words can be inserted into other words, e.g. I hate this bloody university can become I hate this uni-bloody-versity. In English, such ‘infixes’ can apparently only be inserted before a stressed syllable.

See also morphology.

inflectional morphology See inflection and morphology.

inflection A grammatical change in the form of a word (more accurately of a lexeme), which leaves the ‘base meaning’ and the grammatical category of the word unchanged. In English, inflections are restricted to the endings of words (i.e. suffixes). Other languages may show changes elsewhere. As an example, the suffix s is the usual written plural inflection in English. Inflections in nouns may show changes of number, gender, case, etc.; in verbs, of number, person, tense, aspect, etc. See also morphology.

intonation Intonation refers to changes in the tone or frequency of sounds during speech. For example, in English the tone usually falls at the end of a statement and rises at the end of a question, so that You want some coffee. and You want some coffee? can be distinguished by tone alone. In some languages (e.g. Chinese, Thai), sequences containing the same phones but with different intonation patterns correspond to different words.

IPA The International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA is a set of symbols which can be used to represent the phones and phonemes of natural languages. A subset which can be used to represent ‘Standard English English’ (roughly the dialect of middle-class people from the south east of England) is given in a separate table.

J

K

L

labial Bilabial and labiodental phones are together classed as labial.

labiodental A phone produced by the partial closure of the lower lip on the upper teeth. See the diagram of a head. The English sounds represented by the letters f in fit and v in van are labiodental fricatives, produced by restricting the air flow out of the mouth by touching the lower lip on the upper teeth. Bilabial and labiodental phones are together classed as labial.

language See natural language and dialect.

length Length refers to the time duration of a phone. The English words beat and bead differ the length of the vowel as well as the voicing of the terminal stop; the vowel is longer in bead than in beat. In some languages the length of consonants may also be important.

lexeme The four words eat, eats, eating and eaten are morphological variants of the word eat. The past tense ate is not so obviously morphologically connected to eat, but nevertheless has the same underlying meaning. Thus we may say that the five words eat, eats, eating, eaten and ate form a single lexeme, i.e. a single ‘meaning entity’. A dictionary would be expected to contain only one definition for all five words. A lexeme is thus equivalent to what is often called a ‘head word’ in a dictionary.

lexicon Often used as a technical term for the list of words and their types which is used with a grammar.

liquid A liquid is a kind of approximant. English examples are the initial phones in lap and rap.

Location See theta role.

M

masculine See gender.

mood A verb may be in one of several moods. The ‘base’ mood of a verb is the indicative or declarative, where the verb (and hence the sentence which contains it) states what is the case. The imperative mood is used to give instructions or commands. Compare The cat chases the mouse (indicative) with Chase the mouse! (imperative). The subjunctive mood, used to show hypothetical conditions, is rarely shown grammatically in Modern English. (If I were to tell you rather than If I was to tell you is one of the few uses which are at all common.) Languages vary widely in their use of moods.

As with other properties of verbs, it is important to distinguish between grammatical form and meaning. In the sentence I had finished my coursework before John came home, had finished is indicative in meaning, showing that the action was completed in the past before John came home. In the sentence If I had finished my coursework, I would have got a better mark, had finished is subjunctive in meaning, showing that the action was never completed.

morphology The structure of words and the study of this structure. For example, a morphological analysis of the English word unknowingly might yield four components, called morphemes. These are the root know and three affixes, the prefix un indicating negation, and two suffixes ing and ly. Note that both spelling and pronunciation changes can take place when morphemes are combined. Thus the root happy plus the affix ly yields happily not *happyly. Many English words appear to contain morphemes, but resist neat division. For example, the suffix ish often indicates that the word refers to a language (e.g. English, Spanish, Danish, Swedish), but removing the suffix does not always leave a clear root morpheme (e.g. Spanish = ?Span(e) + ish). In other cases, it may be that a word was in the past created from distinct morphemes, but that this is not obvious to a contemporary speaker as the morphemes are no longer used in forming new words.

When an affix morpheme is an inflection, the word can be said to show inflectional morphology. Thus the word chased (= chase + ed) shows inflectional morphology. In many languages, including English, inflectional morphology is relatively predictable, and can be handled by rules.

In other cases, the word can be said to show derivational morphology. Thus the word output = out + put shows derivational morphology: adding the prefix out to the verb put creates a noun with the approximate meaning «that which was put out». In many languages, including English, derivational morphology is unpredictable, and so cannot easily be handled by rules. Thus there’s no noun *outgo meaning «that which went out» (although there is a noun, most often used in the plural, outgoings = out + go + ing + s).

MT = Machine Translation

N

nasal A nasal is a phone made by allowing air to flow out of the nose while possibly stopping it in the mouth. Allowing air to flow out of the mouth is achieved by opening the uvula (see the diagram of a head). English has three such phones: the nasal stops which end the words rum, run and rung.

In many languages (e.g. French, Punjabi), there are also nasal vowels, produced by allowing air to flow out of both the mouth and the nose.

natural language Any language naturally used by people, i.e. not a man-made language like a programming language or Esperanto.

neuter See gender.

NL = Natural Language.

NLP = Natural Language Processing.

nominative See case.

nonterminal See grammar.

noun Semantically, a noun can be described as a word standing for the ‘name of something.’ A more useful test is that a noun or a noun phrase can be replaced by a pronoun, e.g. it or her. Examples of nouns are people, cats and intelligence in Many people think that cats have considerable intelligence. The strings of words many people and considerable intelligence are noun phrases in this example.

NP = Noun Phrase. See also phrase.

number In English, nouns and verbs can be described as singular or plural, generally depending on whether the reference is to one or to many. Thus in the cat runs, cat is singular as is runs, whereas in cats run, cats is plural as is run. English nouns are generally clearly marked as singular or plural; verbs are clearly singular only in the third person singular of the present tense. However, grammatical number must be distinguished from semantic number; trousers is grammatically plural in English (since e.g. we must say my trousers are here and not *my trousers is here), but is clearly semantically singular. Some languages have dual number as well as singular and plural. For example, in Arabic, a special form of the noun corresponds to two rather than one or many. Other languages lack grammatical number (e.g. the Chinese languages).

O

object (of a sentence) The direct object of an active sentence is a noun, noun phrase or pronoun which suffers the action of the verb. Thus in Those people dislike cats, cats is the object of the sentence. In English, only pronouns show case, and become accusative when forming the object of a sentence: thus, e.g., cats in the sentence above must be replaced by them rather than they. In other languages, nouns, adjectives, articles, etc. may all change case. The indirect object of a sentence in English is a noun or equivalent which, if the sentence were re-worded, would require a to (or sometimes a for). Thus in Your mother gave my brother a cake, a cake is the direct object and my brother the indirect object, since if we reverse brother and cake we need a to giving Your mother gave a cake to my brother. Direct and indirect objects may take different cases in some languages; e.g. in German, me is mich (accusative) when it is the direct object, but mir (dative) when it is the indirect object. See also subject.

P

palatal A phone produced when the top of the tongue touches the hard palate. See the diagram of a head for the location of the hard palate. The English sounds represented by the letters sh in ship and s in measure are palatal fricatives, produced by partially stopping the air flow out of the mouth by touching the top of the tongue on the hard palate.

parse To analyse a sentence using a grammar, including deciding whether it is valid and what its structure is according to the grammar.

participant theta-role See theta role.

passive A passive sentence is one which has a basic pattern like The cat was killed or The cat was killed by the dog, i.e. it describes what one thing (the subject) has done to it, often by another thing. The verb in an passive sentence can be said to be in the passive voice. See also active.

Patient See theta role.

person (of a verb) Verbs (in Indo-European languages at least) often vary depending on whether the subject of the verb is in the first person (singular = I, plural = we), the second person (singular and plural = you in modern English), or the third person (singular = he, she or it, plural = they). Only the verb be in the singular shows a full set of changes due to person in modern English: I am, you are, it is.

phone A phone is a ‘unit sound’ of a language in the sense that it is the minimal sound by which two words can differ. For example, the English word feed contains three phones since each can be independently substituted to form a different word. In the IPA, the three phones can be written as [f], [i] and [d]. Examples of substitutions are: [fid] — [f] + [s] gives [sid], i.e. seed; [fid] — [i] + [u] gives [fud], i.e. food; [fid] — [d] + [t] gives [fit], i.e. feet. The whole of each phone must be substituted to change one word into another. It is important to note that whether or not speakers can distinguish between sounds is not a test of whether they constitute distinct phones. The word tea could be represented as [ti] and the word tree as [tri]. However, the two ‘t sounds’ are not quite the same: the tongue is further back in the mouth when pronouncing the [t] in [tri] than when pronouncing the [t] in [ti]. How far to divide up sounds into phones is essentially a pragmatic question. Using more phones will enable speech to represented more accurately but at a cost in terms of complexity. See also allophone, phoneme.

phoneme A phoneme is a minimally distinctive set of sounds in a language; sound sequences which differ in a single phoneme can constitute different words. Thus the pairs tip-dip and trip-drip show that English has two distinct phonemes, which we can write as /t/ and /d/, since substituting one for the other produces a different word. However, the pronunciation of /t/ (and /d/) is not the same in each pair: the tongue is further back in the mouth when /t/ is followed by /r/. Hence there are at least two phones corresponding to the /t/ phoneme. However there are no two English words in which the ONLY difference is that the ‘t sound in trip’ is replaced by the ‘t sound in tip’ — these two sounds are allophones of the same phoneme. English speakers do not need to recognize the difference between them.

phonetics Phonetics is the study of the sounds of speech (i.e. the study of phones). It can be distinguished from phonology which is more concerned with the underlying theory (i.e. the phonemes which underlie phones and the rules which govern the conversion of phonemes to phones and vice versa).

phonological rule At some theoretical level, words can be considered to be composed of phonemes. The actual sound of a word then depends on which allophone is chosen for each phoneme. The context-sensitive rules which determine this are called phonological rules. Thus the word input can be considered to contain the phoneme /n/. However in fast speech in many dialects of English, the phone used will be [m]. The relevant phonological rule for English is that a nasal becomes articulated at the same position as a following stop.

phonology See phonetics.

phrase A string of words can often act as an exact grammatical substitute for a single word; such a string is called a ‘phrase’. Thus e.g. a noun can be replaced by a noun phrase — compare Whiskers is over there with That appalling pet of yours is over there, in which That appalling pet of yours is a noun phrase equivalent to the noun Whiskers.

plosive See stop.

plural See number.

possessive See genitive.

pragmatics A technical term meaning, roughly, what the person speaking or writing actually meant, rather than what the words themselves mean.

prefix A prefix is a morpheme which is added before a root morpheme in the formation of a word. See morphology.

preposition A preposition is one of a finite set of words (e.g. at, from, by) which in English must usually be followed by a noun or its equivalent. A prepositional phrase (PP) consists of a preposition followed by a noun, pronoun or noun phrase. Two major uses of prepositional phrases are to show location (e.g. on the mat in the cat sits on the mat) and motion (e.g. into the house in the cat runs into the house). The word preposition comes from pre plus position. In other languages (e.g. Japanese), there are postpositions: words which come after a noun or its equivalent.

production See grammar.

pronoun A pronoun is one of a small set of words which can substitute for a noun or noun phrase. It usually refers back to a previous occurrence of the noun or noun phrase. Thus, e.g., it in the previous sentence is a pronoun which refers back to A pronoun in the sentence before. The process of referring is sometimes called anaphora.

Q

R

Recipient See theta role.

referential semantics A system where the meaning of a word just is the thing it refers to.

RTN = Recursive Transition Network.

S

semantic feature A semantic feature is a ‘primitive’ which a language processor (human or computer) is assumed to be able to determine independently of the language system. The meaning of words such as nouns or adjectives can then be described in terms of sets of these features. For example we might describe the meaning of words such as boy, man, girl and woman in terms of the features YOUNG, MALE and HUMAN. Boy would be [+YOUNG, +MALE, +HUMAN], woman would be [-YOUNG, -MALE, +HUMAN].

semantics Used as a technical term for the meaning of words and sentences (see also pragmatics).

singular See number.

start symbol See grammar.

stop Some phones are produced by completely stopping and then releasing the flow of air out of the mouth. These sounds are called stops. In most dialects of English there are three stop positions, corresponding to the initial phones in pale, tale and kale, or the terminal nasal phones in rum, run and rung. Some dialects of English (for example those spoken in England around London) also have a glottal stop, used, for example, instead of the ‘t sound’ in words like bottle.

[The current tendency is to use the term plosive instead of stop. I resist this for the following reason. A stop actually consists of two phases: closure (when air pressure builds up) and release (when air explodes out). These phases can be separated: in many languages, stops are often not released (e.g. in the Bahasa language spoken in Malaysia and Indonesia, or at the end of words in many dialects of English spoken in northern England). The term ‘unreleased stop’ makes sense, whereas an ‘unreleased plosive’ is a contradiction.]

stress Words can be divided into syllables, usually centred around a vowel. In many languages, including English, the duration and relative loudness of a syllable — its stress — are important. Thus only stress distinguishes the noun PROcess (as in the sentence This process is called assimilation) from the much less common verb proCESS (as in the sentence I usually process at the degree ceremony). The noun is stressed on the first syllable, the verb on the second.

STT = Speech To Text.

subject (of a sentence) The subject of a sentence is the noun or noun equivalent which governs the verb, in the sense that if the language has agreements, the verb has to agree with the subject in number (as in English) or in gender (as in Arabic). Thus in English we have to say The dog chases the cats not The dog chase the cats; the verb chases agrees in number with the subject the dog rather than the object the cats. In the semantically equivalent passive sentence, The cats are chased by the dog, the fact that the cats is now the subject is shown by the need to use the plural auxiliary, are.

In an active sentence, the subject is often the entity which performs the action of the verb; in a passive sentence the subject is the entity which is in some sense the recipient of the action.

See also object.

suffix A suffix is a morpheme which is added after a root morpheme in the formation of a word. See morphology.

syntax The syntax of a language comprises, roughly speaking, the patterns into which its words can be validly arranged to form sentences. The combination of morphology and syntax is sometimes called the grammar of a language.

T

tense (of a verb) The tense of a verb specifies the time at which its action occurs. The clearest examples in English are the present and past tenses. When saying I am eating an apple the speaker refers to the present; when saying I was eating an apple, s/he refers to the past. In its morphology, an English verb shows tense and aspect independently (see the table under aspect). Semantically, tense and aspect are not so easy to separate in English. I have eaten the apple is described morphologically as ‘present perfect’, but semantically is partly a reference to the past, and partly a reference to the action’s being complete rather than continuing.

The future tense in English is formed by the use of the auxiliary will or sometimes shall. Morphologically, these auxiliaries can show ‘past tense’; thus I would have been eating is the ‘future past perfect progressive’ of eat. Semantically, the combination of ‘future’ and ‘past’ is used to express ‘conditionality’, so that this form of the verb is usually called ‘conditional’.

terminal node A node in a transition network at which parsing can stop.

terminal See grammar.

thematic role See theta role.

theta role (Often written as θ-role.) Verbs require a number of other components to be present in a sentence to complete their meaning. These components can be said to act as arguments to the verb, i.e. to be argument theta roles (or, alternatively, to play participant theta roles in relation to the action of the verb). For example, in the sentence The girl put the bottles on the table, the action of ‘putting’ involves three necessary thematic roles. These are Agent, the entity doing the putting; Patient, the entity which suffers the action of being put; and Location, where the Agent puts the Patient. A sentence containing the verb put will involve these three roles, even if they occur in different positions due to the syntax of the sentence. Thus exactly the same entities play exactly the same theta roles in the sentence The bottles were put on the table by the girl although the syntax is different from the previous sentence.

Another common θ-role is Recipient, the entity which receives something, typically the Patient. Thus the boy is the Recipient in both The girl gave the bottles to the boy and The boy was given the bottles.

In addition to argument or participant theta roles, there are adjunct or circumstantial theta roles. These show additional, non-required components. For example, in the kitchen plays an argument theta role in He was putting apples in the kitchen but only an adjunct theta role in He was eating apples in the kitchen. In both cases in the kitchen is a location, but put requires this role, eat merely allows it to be present.

TN = Transition Network.

TTS = Text To Speech.

U

unvoiced See voicing.

V

velar A phone produced when the top of the tongue touches the soft palate or velum. See the diagram of a head for the location of the soft palate. The English sounds represented by the letters k in kit and g in got are velar stops, produced by stopping and then releasing the air flow out of the mouth by touching the top of the tongue on the soft palate.

verb A verb is traditionally described as a ‘doing’ word; thus in the sentences Colourless ideas sleep furiously and The dog bit the cat, sleep and bit are verbs. A more useful test is that a verb combines with an auxiliary in structures such as I can _ or I can _ them. English makes extensive use of ‘verb groups’ or ‘compound verbs’, such as has been eating in He has been eating fish in which one or more auxiliaries is combined with a verb.

Verbs may show a wide range of grammatical properties, including gender, person, tense, aspect, voice and mood. There are major differences among languages in the way these properties are shown grammatically and in their associated meanings.

voice A verb may be in the active or passive voice, and hence so may the sentence in which the verb appears. Compare The dog chased the cat (active) with The cat was chased by the dog (passive). This use of the term ‘voice’ has no connection with ‘voiced’ or ‘voiceless’.

In English, the grammatical voice of a verb is closely related to its meaning. In a sentence with an active verb the subject is typically the Agent, whereas in a sentence with a passive verb the subject is typically the Patient or the Recipient. Compare the active sentence The girl gave her mother a present, in which the girl is the subject and the Agent, with the passive sentences A present was given to her mother, in which a present is the subject and the Patient, and Her mother was given a present, in which her mother is the subject and Recipient.

In other languages, grammatical voice and meaning are less well aligned. For example, in Greek, both Classical and Modern, verbs which are passive in form may have active meanings, usually when the agent and patient are the same. Thus in Modern Greek, χτενίζω means «I comb» or «I am combing» but is only used when the patient (the thing being combed) is not the subject. The passive form χτενίζομαι normally means «I am combing [my hair]» rather than «I am being combed».

voiced See voicing.

voiceless See voicing.

voicing Voicing refers to whether or not the vocal cords are vibrated during the production of a phone. Phones such as vowels or [b] or [d] in which the vocal cords are vibrated are said to be voiced. Phones such as [s] or [p] in which the vocal cords are not vibrated are said to be voiceless or unvoiced.

vowel (1) A phone which is produced by allowing lung air to pass over the vibrating vocal cords and then freely out of the mouth. Thus vowels can be continued until you run out of breath. The positions of the lips and tongue alter the size and shape of the resonating cavity to produce different sounds. (2) A letter of the alphabet usually pronounced using a vowel phone is also called a vowel.

Be careful to distinguish these two usages. In a language with non-phonemic spelling, such as English, they can be quite different. The word site, for example, contains two vowel letters but only one vowel phone since the terminal e is not pronounced.

See also consonant.

W

X

Y

Z

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

U |

V |

W |

X |

Y |

Z

I really didn’t know how to name this thread so I apologize about it. My question is: what is the linguistic term that refers globally to the words «vocabulary», «words», «phrases», «collocations», «expressions», «jargon», «idioms», «lexicon» etc?

I am doing an article on this and in the process of writing my paper when I put the word «vocabulary» I feel like I am referring only to single-words (e.g.: coincidence) opposite to when I write «phrase» which refers to more than one word without a verb/subject (e.g.: many thanks) or when I write «expression/idiom» it refers, generally speaking, to more words with a verb/subject (e.g: She is pulling my leg). The problem is I need to refer to these in one word, what is that word? I was thinking of «lexicon» but I am not sure. Is there something like «linguistic inventory»? I really need this word.

Thank you a lot. I hope that wasn´t so confusing.

asked Mar 2, 2015 at 1:25

7

Please accept my apologies for not having the appropriate and sufficient language skills to understand your style of English. Therefore, I may have misunderstood your question.

The words you could use are

- vocabulary

- repertoire

For examples,

- She has a limited vocabulary of Arabic words.

- She has an accumulated repertoire of curse words in Tamil.

vocabulary (vəˈkæbjʊlərɪ)

n, pl -laries

- (Linguistics) a listing, either selective or exhaustive, containing the words and phrases of a language, with meanings or translations into another language; glossary

- (Linguistics) the aggregate of words in the use or comprehension of a specified person, class, profession, etc

- (Linguistics) all the words contained in a language

- a range or system of symbols, qualities, or techniques constituting a means of communication or expression, as any of the arts or crafts: a wide vocabulary of textures and colours.

[from Medieval Latin vocābulārium, from vocābulārius concerning words, from Latin vocābulumvocable]

repertoire (ˈrɛpəˌtwɑː)

n

- all the plays, songs, operas, or other works collectively that a company, actor, singer, dancer, etc, has prepared and is competent to perform

- the entire stock of things available in a field or of a kind: the comedian’s repertoire of jokes was becoming stale.

- (Theatre) in repertoire denoting the performance of two or more plays, ballets, etc, by the same company in the same venue on different evenings over a period of time: Nutcracker returns to Covent Garden over Christmas in repertoire with Giselle.

[from French, from Late Latin repertōrium inventory; see repertory]

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003

answered Mar 2, 2015 at 2:09

Blessed GeekBlessed Geek

9,53118 silver badges34 bronze badges

1

Here are the words and phrases for discussing the words and phrases in language study.

-

a word — a single standalone unbroken unit of expression e.g. ‘dog’.

-

a term — one or more words together, usually a noun phrase (this is an inclusive word meaning that a single word is a term). e,g, ‘dog’ or ‘lap dog’ (a smaller dog that can sit comfortably in your lap)

-

phrase — the sequence of words in a single constituent. In «The man saw the lap dog in the house», the sequence ‘saw the’ is not a phrase, but ‘in the house’ is.

-

the lexicon — the collection of words (and possibly terms and sayings) that used in a language

To some of your points, the lexicon can be for a single person «That word is not in this three-year olds’ lexicon» or for the community «‘innit’ is specific to the lexicon of informal British English».

For terms, the word ‘expression’ or ‘phrase’ are common synonyms. ‘Idiom’ is related but has more connotations to it, so not usually an easily substitutable item.

answered Mar 2, 2015 at 13:11

MitchMitch

70.1k28 gold badges137 silver badges260 bronze badges

1

The term that is closest to what I was looking for is «lexical item» as it is broader than «vocabulary» and not as much as «language» (as was suggested previously):

«A lexical item (or lexical unit, lexical entry) is a single word, a part of a word, or a chain of words (=catena) that forms the basic elements of a language’s lexicon (≈vocabulary). Examples are cat, traffic light, take care of, by the way, and it’s raining cats and dogs. Lexical items can be generally understood to convey a single meaning, much as a lexeme, but are not limited to single words. »

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexical_item

Mitch

70.1k28 gold badges137 silver badges260 bronze badges

answered Mar 2, 2015 at 12:17

1

The English language is a complicated system. To understand the complex parts of the language, it is useful to study linguistic terms and concepts.

Linguistics is the systematic study of language. Studying linguistic elements and the types of words in linguistics can help people better understand how words and sentences are formed, thus developing a deeper understanding of their meaning. This can strengthen writing, reading, and speaking skills!

Linguistic Terms: English Language

Linguistics is the systematic study of language. Professionals who study linguistics are called linguists. Linguists look at various aspects of language, including the small sounds that make up words and how the meaning of words changes based on context.

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language systems.

There is so much to study within linguistics that there are several specialized fields within the field, like the following:

- Biolinguistics — examines how biological variables shape the evolution of language

- Ethnolinguistics — examines the relationship between culture and language

- Neurolinguistics — examines the relationship between the functions of the human brain and language

- Psycholinguistics — examines the impact of psychological variables on language

- Sociolinguistics — examines the relationship between society and language

Linguistic Elements of Language

Linguistics examines many elements of language, including the following:

|

Element |

Definition |

|

Phonemes |

Small sound units |

|

Morphemes |

Small units of words |

|

Syntax |

Word order |

|

Semantics |

Literal meanings of words |

|

Pragmatics |

Meanings of words in context |

|

Lexical words |

Words with concrete meaning in sentences |

|

Functional words |

Words that serve a grammatical function in a sentence |

The section below elaborates on the four main linguistic terms and concepts.

Linguistic Terms and Concepts

There are four main areas of linguistics: phonology, grammar, semantics, and pragmatics.

Phonology

Phonology is the study of speech sounds in a language. Linguists studying phonology study phonemes, the smallest units of sound in a language.

Phonemes are the smallest meaningful units of sound in a language.

For example, car and bar are different because the phonemes «c» and «b» are different. However, phonemes do not always correspond with spelling, especially in English. Regional dialects and social dialects also shape differences in speech.

Grammar

Grammar refers to the structural rules of a language. In linguistics, grammar has two major sub-parts: syntax and morphology.

Syntax

Syntax refers to word order within a sentence. The order of words in sentences impacts the meaning of sentences and also shapes the tone and style of writing. For example, consider the following sentences:

She yells at me sometimes.

Sometimes she yells at me.

Putting the adverb «sometimes» at the end of the first sentence emphasizes the frequency of the yelling. It makes it seem like the situation is not that bad because it is only sometimes. However, in the second sentence, the adverb comes first and the information about yelling comes second. This emphasizes the action and makes it seem worse than the first sentence.

Morphology

Morphology studies the formation of words and how they relate to one another. Studying morphology requires studying morphemes, the smallest lexical units of a language.

A morpheme is a unit of language that cannot be divided without changing its meaning.

For instance, consider the word pen. This word is a morpheme because it cannot be divided anymore. «Pe» and «n» do not hold any meaning by themselves.

Morphemes are not always words, though. For example, consider the word unbreakable. This word is made up of three morphemes: «un,» «break,» and «able.» «Un» is not a word but a prefix, which is added to the beginning of a root word and carries its own meaning. «S» is also a morpheme because when it is added to a word, it indicates plurality.

Semantics

The study of semantics is the study of words’ meanings. Linguists who study semantics look at the interaction between small parts of discourse and how they interact to form larger meanings.

Linguists who study semantics also examine how people can draw different meanings from words. They take into account connotation and denotation.

The denotation of a word is its literal definition.

The connotation of a word is the possible meaning associated with a word that is not its literal definition.

For example, consider the sentence: The colors on those buildings are very loud. According to the denotation of loud, the word is used to describe something making a lot of noise. However, in this sentence, the connotation is something bright. Semantics takes into account variations in word meanings like this one.

The two main types of semantics are lexical and phrasal.

Lexical Semantics

Lexical semantics is all about analyzing the meaning of words and their relationships. Linguists who study lexical semantics examine how to articulate the meaning of words and how to deal with variability in word meaning. For example, consider the word sign. People assign different types of meanings to this word. For example, a stop sign on the road is a type of sign, but when someone puts their finger to their lips, it is a sign to stop speaking.

Phrasal Semantics

Phrasal semantics is all about examining how words and phrases come together to form the meaning of the larger expressions. In contrast to lexical semantics, it looks at more than one word. For example, consider the sentence John wrote the song. This sentence is grammatically different than the sentence The song was written by John. John is only the subject in the first sentence. However, semantically, the sentences have the same meaning because the individual words come together to convey the same idea.

Pragmatics

The study of pragmatics is the study of how the context of language contributes to its meaning. Context is a broad term that refers to something’s surroundings, including the culture, society, and places in which it occurs.