Syntagmatic Relation

between words in English. Lexical Valency & Collacability.

-

Syntagmatic relations of words. The importance of Syntagmatic

Analysis. -

Lexical & grammatical collacability.

-

Types of word-groups.

Syntagmatic relations of

words. The importance of Syntagmatic Analysis.

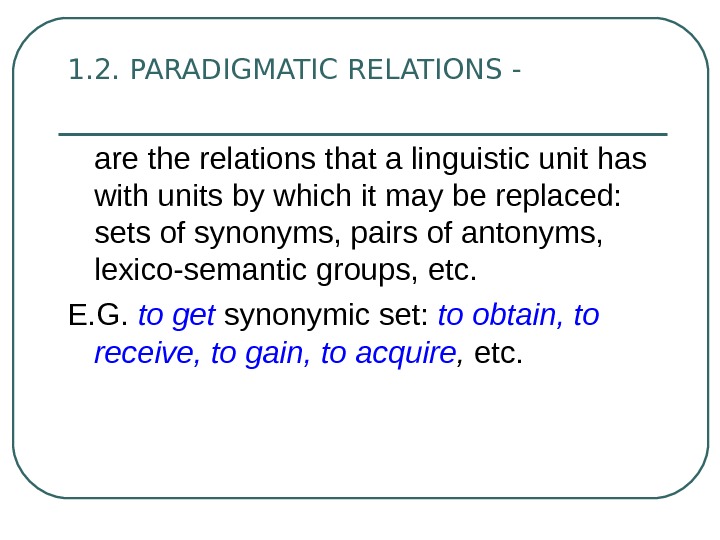

The relations existing between words as separate lexical units within

the vocabulary as a system are called paradigmatic or the relations

on the vertical axis. They define the meaning through its

interrelation with other members of the subgroup it belongs to within

the vocabulary system.

There are various types of semantic paradigmatic relations in

English:

-

Synonimic

-

Antonymic

-

Hyponimic & the others

In the flow of speech the word combines with other words forming a

kind of chain. These linear relations of words in connected speech

are called syntagmatic relations or the relations on the horizontal

level.

Syntactical relations define the meaning of a word

when it’s used in combination with other words in speech. Words put

together in speech make functional units called phrases or word-group

or word combinations or collacations.

Word-group – the largest, two-facet functional lexical units

(assuming that the word is the basic lexical unit), comprising more

than 1 word on the syntagmatic level of Analysis.

The immediate connections of the word lie within

the simple word-group consisting of 2 notional words. The relations

between these words depend on their semantic structure which in its

turn determines their combining power or collacability.

Thus, the word-group may represent that minimal stretch of speech of

the speech context that determines the individual, actual meaning of

the word in speech.

Syntagmatic Analysis – is the study of the semantic

characteristics of the word & its collacability, i.e. the ability

to combine with other words in speech on the basis of its typical

contexts or combinations with other words in speech.

It may be applied for different purposes:

-

to discover most frequently used collocations in English;

-

to study the possibilities of the realization of certain types of

mean, in certain collocations; -

to study the norms of valency & collacability of correlated

words in different languages which is very important in teaching

foreing languages, translation & lexicography.

Соседние файлы в папке Lecture9

- #

- #

- #

Before we discuss what syntagmatic relation is, let’s first have a look at semiotics, saussure, and syntagms.

Semiotics, saussure, and syntagms

The term ‘syntagmatic’ is closely related to the field of semiotics. Semiotics is the study of how meanings are produced by signs.

Road signs are a good example. You can understand the meaning of the signs even though there aren’t any words to explain what they mean. Look at the two road signs below. You know that the left one means ‘no u-turns’ and the right one means ‘slippery road’.

Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) argued that:

- Words in a sentence are meaningfully related to each other. Saussure called this relationship syntagmatic, and the combinations of two or more words that create the chain of words he called syntagms.

When a single word or element of the chain is altered, the overall meaning is also changed. This chain concept is the basis of syntagmatic relations.

What is a syntagmatic relation?

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence. Let’s look at an example:

↤ Syntagmatic relations ↦

Paul is roasting a chicken

The syntagmatic relation in this sentence explains:

- The word position and order: Paul + is roasting + a chicken

- The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence:

- It is a chicken that Paul is roasting, not something else.

- It is Paul who is roasting a chicken, not someone else.

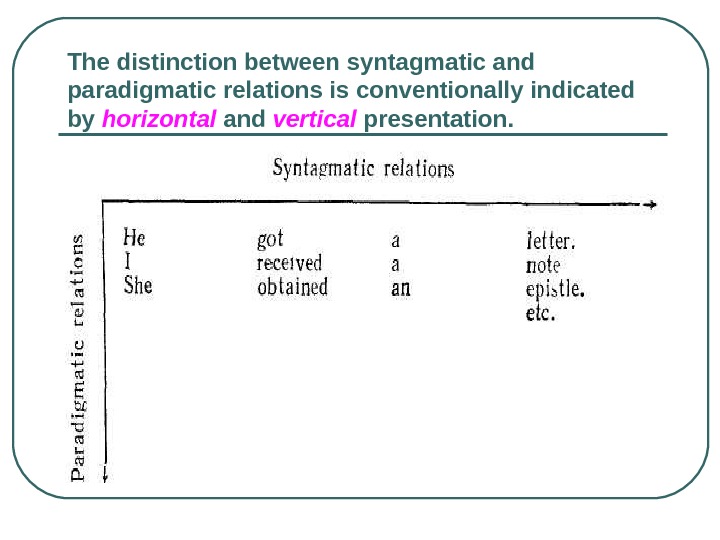

Thus, the syntagmatic relation refers to a word’s ability to combine with other words, and the syntagmatic dimension (syntagm) always refers to the horizontal axis or linear aspect of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations), such as have + a party in ‘We had a party on Saturday’. If you hear someone say, ‘We made a party on Saturday’, you’ll probably cringe because make + a party doesn’t sound right.

The opposite of syntagmatic relation is paradigmatic relation. Paradigmatic relation refers to the relationship between words that can be substituted within the same word class (on the vertical axis).

Study tip: Syntagmatic relation is about word order and position. The meaning of syntagmatic is similar to syntax (the arrangement of words and phrases in a sentence).

Syntagmatic relations examples

Some examples of syntagmatic relations are shown in the table below:

| ↤ Syntagmatic relations ↦ | ||||

| Subject | verb | Object | ||

| Determiner | Adjective | Noun | Noun | |

| The | beautiful | woman | buys | some brioche |

| handsome | man | sold | some cake | |

| tall | boy | is eating |

a hotdog |

From these sentences, the syntagmatic relations are all the relationships between words within the same sentence. That means there is a syntagmatic relation in:

- The beautiful woman + buys + some brioche (sentence level).

- The + beautiful + woman (phrase level).

- The handsome man + sold + some cake; and the + handsome + man.

- The tall boy + is eating + a hotdog; and the + tall + boy.

Additionally, in all three sentences above, each grammatical function (ie, subject, verb, and object) is at the same level. But in some cases, if you change the order of the sentence structure, it can change the meaning completely. For example:

- The tall boy is eating a hotdog.

- A hotdog is eating the tall boy.

The two sentences use the same words (syntagms) but differ in order (syntagmatic relationship), which changes the meaning of the sentence.

Types of syntagmatic relations

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

1. There are three interesting facts about collocations:

- There isn’t a specific rule for the way words go together (why A is commonly paired with B). It is based on what the speakers of a language commonly combine, and eventually, what sounds natural. That’s why when you read, ‘a handsome girl’ instead of ‘a pretty girl’ it feels odd.

2. Word substitution is possible

- Sticking with the example of handsome girl, technically, it isn’t wrong to say handsome girl because handsome means ‘good-looking’ (Oxford Learner’s Dictionary) which is gender-neutral. Therefore, you can say handsome girl, but it just doesn’t sound natural.

3. The collocation’s meaning can be traced back to the meaning of each component

- For instance, catch a cold means ‘getting a cold’ and office hours means ‘the hour someone dedicates to work’. The definition of each component forms the meaning of a collocation.

Here are some examples of collocations:

Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, take advantage of.

Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

1. The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- You can’t substitute the words in idioms, even with their synonyms. For instance, in ‘kill two birds with one stone’ the stone is substituted with rock and becomes ‘kill two birds with one rock’. This version of the idiom simply doesn’t exist, even though the overall meaning and construction of the sentence remains unchanged.

2. The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

- It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

- Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Here are some examples of popular idioms:

Break a leg.

Miss the boat.

Call it a day.

It’s raining cats and dogs.

Kill two birds with one stone.

Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations examples in grammar

Paradigmatic relation describes the relationship between words that can be substituted for words with the same word class (eg replacing a noun with another noun). A paradigm in this sense refers to the vertical axis of word selection. This explains why paradigmatic relation is the opposite of syntagmatic relation.

Now that we have covered the paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations, we can say that:

- Paradigmatic relation describes a substitution relationship between words of the same word class. The substitution occurs on the vertical axis.

- Syntagmatic relation illustrates the linear relationship / position between the words in a sentence. The syntagmatic relation occurs on the horizontal axis.

|

↥ Paradigmatic relations ↧ |

↤ Syntagmatic relations ↦ | |||

| Subject | verb | Object | ||

| Determiner | Adjective | Noun | Noun | |

| The | beautiful | woman | buys | some brioche |

| The | unattractive | lady | buys | some bread |

| That | handsome | man | ate | some chicken |

Paradigmatic relation:

Let’s take ‘The beautiful woman buys some brioche‘.

- The beautiful woman can choose to buy: some bread or chicken instead of brioche.

- Brioche, bread, and chicken are parts of a paradigm of food that the beautiful woman can buy.

- All the items in the paradigm share some kind of function (in this example: the object of the sentence) and this paradigm represents the category they belong to (in this example: food).

- Some words from the sentence can also be substituted vertically: ‘An unattractive (antonym) lady (synonymy) buys some bread (hyponymy)’.

Syntagmatic relation:

Let’s take ‘That handsome man ate some chicken‘.

- The combination of ‘that handsome man + ate + some chicken’ forms a syntagmatic relationship.

- If the word position is changed, it also changes the meaning of the sentence, eg ‘Some chicken ate the handsome man’.

- Furthermore, the linear relationship also occurs at phrase-level: it is ‘handsome + man’, not ‘handsome + woman’ (collocation).

Syntagmatic Relations — Key takeaways

- Syntagmatic relation illustrates the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It occurs on the horizontal axis.

- Syntagmatic relation explains the concept of collocations and idioms.

- Collocations are words that frequently occur together. The word pairings in collocations are not fixed, but changing the word pairing will make the combination sound unnatural, eg handsome man vs. handsome girl.

- Idioms are fixed expressions that possess a meaning other than their literal one. The words in idioms can’t be substituted, eg miss the boat becomes miss the ship, which is not an idiom.

- Paradigmatic relation illustrates the relationship between words that can be substituted within the same grammatical position.

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

- Сейчас обучается 268 человек из 64 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Intralinguistic Relations of Words

Types of Semantic Relations

Lecture 6 -

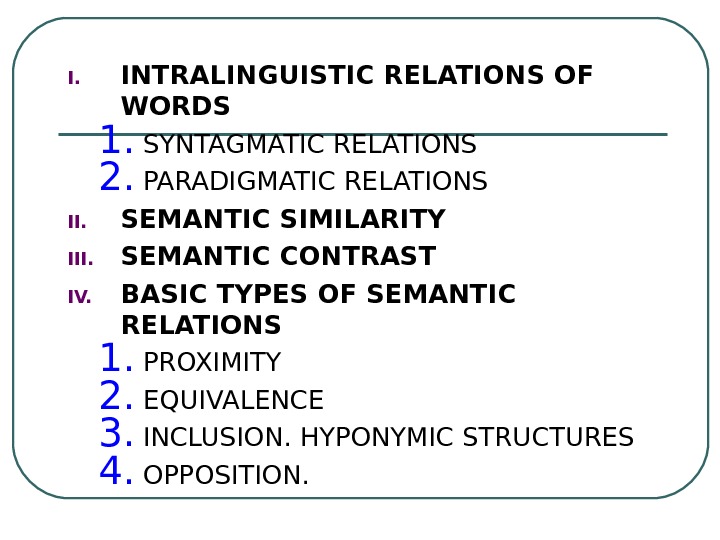

2 слайд

INTRALINGUISTIC RELATIONS OF WORDS

SYNTAGMATIC RELATIONS

PARADIGMATIC RELATIONS

SEMANTIC SIMILARITY

SEMANTIC CONTRAST

BASIC TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

PROXIMITY

EQUIVALENCE

INCLUSION. HYPONYMIC STRUCTURES

OPPOSITION. -

3 слайд

I. Intralinguistic Relations of Words

Ferdinand de Saussure:

Intralinguistic relations exist between words

They are basically of two types: syntagmatic and paradigmatic -

4 слайд

1.1. Syntagmatic Relations —

are the relationships that a linguistic unit has with other units in the stretch of speech in which it occurs.

He got a letter (to receive);

He got tired (to become);

He got to London (to arrive);

He could not get the piano through the door (to move smth. to or from a position or place). -

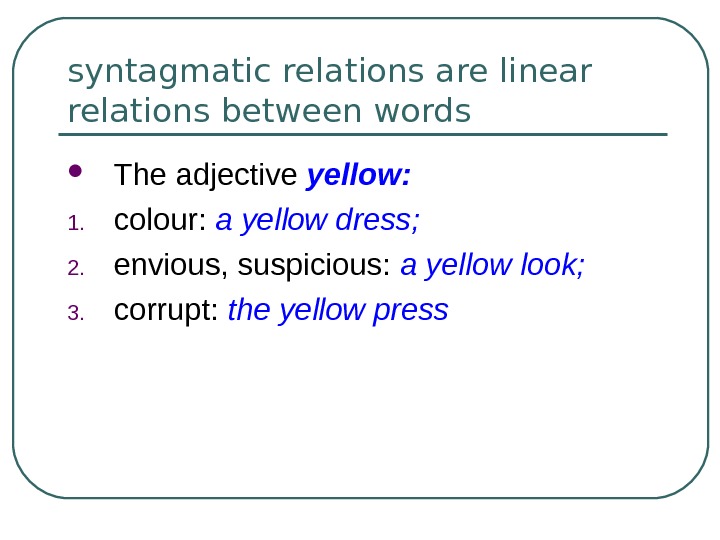

5 слайд

syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

colour: a yellow dress;

envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

corrupt: the yellow press -

6 слайд

Context — the minimal stretch of speech determining each individual meaning of the word.

free or denominative meanings — the meaning or meanings representative of the semantic structure of the word and least dependent on context:

table – a piece of furniture;

make — construct, produce’ -

7 слайд

1.2. PARADIGMATIC RELATIONS —

are the relations that a linguistic unit has with units by which it may be replaced: sets of synonyms, pairs of antonyms, lexico-semantic groups, etc.

E.G. to get synonymic set: to obtain, to receive, to gain, to acquire, etc. -

8 слайд

The distinction between syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations is conventionally indicated by horizontal and vertical presentation.

-

9 слайд

II. SEMANTIC SIMILARITY

Lexical units may also be classified by the criterion of semantic similarity and semantic contrasts. The terms generally used to denote these two types of semantic relatedness are synonymy and antonymy. -

10 слайд

Similar relations between word-groups and sentences are described as semantic equivalence.

Synonyms may be found in different parts of speech and both among notional and function words. For example, though and al’beit, on and upon, since and as are synonymous because these phonemically different words are similar in their denotational meaning. -

11 слайд

Synonyms are traditionally described as words different in sound-form but identical or similar in meaning.

This definition has been severely criticised on many points. -

12 слайд

Firstly,

it seems impossible to speak of identical or similar meaning of words as such as this part of the definition cannot be applied to polysemantic words. It is inconceivable that polysemantic words could be synonymous in all their meanings. -

13 слайд

The verb look, is usually treated as a synonym of see, watch, observe, etc., but in another of its meanings it is not synonymous with this group of words but rather with the verbs seem, appear (cf. to look at smb and to look pale).

The number of synonymic sets of a polysemantic word tends as a rule to be equal to the number of individual meanings the word possesses. -

14 слайд

One of the ways of discriminating between different meanings of a word is the interpretation of these meanings in terms of their synonyms, e.g. the two meanings of the adjective handsome are synonymously interpreted as handsome — ‘beautiful’ (usually about men) and handsome — ‘considerable, ample’ (about sums, sizes, etc.).

-

15 слайд

Secondly,

it seems impossible to speak of identity or similarity of lexical meaning as a whоle as it is only the denotational component that may be described as identical or similar. If we analyse words that are usually considered synonymous, e.g. to die, to pass away; to begin, to commence, etc., -

16 слайд

The connotational component or the stylistic reference of these words is entirely different and it is only the similarity of the denotational meaning that makes them synonymous.

-

17 слайд

The words, e.g. to die, to walk, to smile, etc., may be considered identical as to their stylistic reference or emotive charge, but as there is no similarity of denotational meaning they are never felt as synonymous words.

-

18 слайд

Thirdly,

it does not seem possible to speak of identity of meaning as a criterion of synonymity since identity of meaning is very rare even among monosemantic words.

Cases of complete synonymy are very few and are confined to technical nomenclatures where we can find monosemantic terms completely identical in meaning as, for example, spirant and fricative in phonetics. -

19 слайд

Words in synonymic sets are in general differentiated because of some element of opposition in each member of the set. The word handsome, e.g., is distinguished from its synonym beautiful mainly because the former implies the beauty of a male person or broadly speaking only of human beings, whereas beautiful is opposed to it as having no such restrictions in its meaning.

-

20 слайд

Thus

it seems necessary to modify the traditional definition and to formulate it as follows: synonyms are words different in sound-form but similar in their denotational meaning or meanings. Synonymous relationship is observed only between similar denotational meanings of phonemically different words. -

21 слайд

Differentiation of synonyms may be observed in different semantic components — denotational or connotational.

-

22 слайд

The difference in denotational meaning cannot exceed certain limits, and is always combined with some common denotational component.

-

23 слайд

The verbs look, seem, appear, e.g., are viewed as members of one synonymic set as all three of them possess a common denotational semantic component “to be in one’s view, or judgement, but not necessarily in fact” and come into comparison in this meaning (cf. he seems (looks), (appears), tired).

-

24 слайд

There is a certain difference in the meaning of each verb:

seem suggests a personal opinion based on evidence (e.g. Nothing seems right when one is out of sorts);

look implies that opinion is based on a visual impression (e.g. The city looks its worst in March),

appear sometimes suggests a distorted impression (e.g. The setting sun made the spires appear ablaze). -

25 слайд

The relationship of synonymity implies certain differences in the denotational meaning of synonyms.

This classification proceeds from the assumption that synonyms may differ either in the denotational meaning (ideographic synonyms) оr the connotational meaning, or to be more exact stylistic reference. -

26 слайд

This assumption cannot be accepted as synonymous words always differ in the denotational component.

Thus buy and purchase are similar in meaning but differ in their stylistic reference and therefore are not completely interchangeable. -

27 слайд

That department of an institution which is concerned with acquisition of materials is normally the Purchasing Department rather than the *Buying Department.

A wife however would rarely ask her husband to purchase a pound of butter. It follows that practically no words are substitutable for one another in all contexts.

-

28 слайд

This fact may be explained as follows: firstly, words synonymous in some lexical contexts may display no synonymity in others.

The comparison of the sentences The rainfall in April was abnormal and The rainfall in April was exceptional may give us grounds for assuming that exceptional and abnormal are synonymous.

The same adjectives in a different context are by no means synonymous, as we may see by comparing My son is exceptional and My son is abnormal. -

29 слайд

Secondly, interchangeability alone cannot serve as a criterion of synonymity.

Synonyms are words interchangeable in some contexts. But the reverse is certainly not true as semantically different words of the same part of speech are, as a rule, interchangeable in quite a number of contexts: in the sentence

I saw a little girl playing in the garden

the adjective little may be formally replaced by a number of semantically different adjectives, e.g. pretty, tall, English, etc. -

30 слайд

Thus a more acceptable definition of synonyms :

synonyms are words different in their sound-form, but similar in their denotational meaning or meanings and interchangeable at least in some contexts. -

31 слайд

III. SEMANTIC CONTRAST

Antonymy in general shares many features typical of synonymy.

Perfect or complete antonyms are fairly rare.

The relations of antonymy restricted to certain contexts. Thus thick is only one of the antonyms of thin (a thin slice—a thick slice), another is fat (a thin man—a fat man). -

32 слайд

The term opposite meaning is rather vague and allows of essentially different interpretation.

kind — ‘gentle, friendly, showing love, sympathy or thought for others’ and cruel — ‘taking pleasure in giving pain to others, without mercy’,

They denote concepts that are felt as completely opposed to each other. -

33 слайд

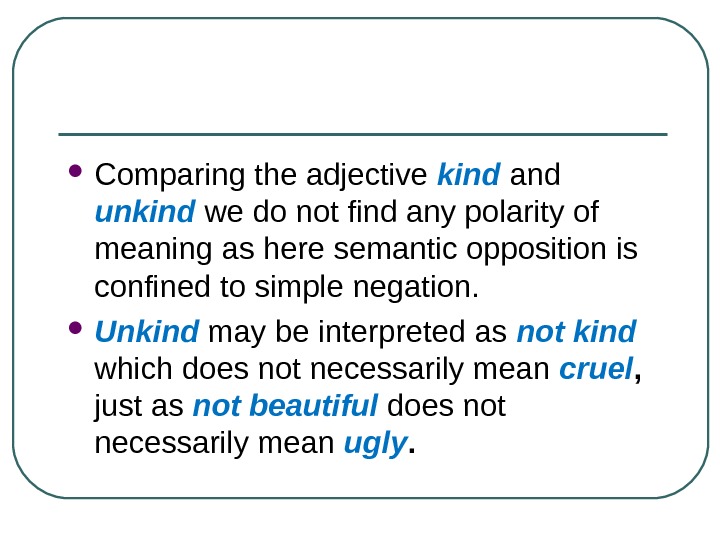

Comparing the adjective kind and unkind we do not find any polarity of meaning as here semantic opposition is confined to simple negation.

Unkind may be interpreted as not kind which does not necessarily mean cruel, just as not beautiful does not necessarily mean ugly. -

34 слайд

II. BASIC TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

2.1. PROXIMITYMeaning similarity is seldom complete and nearly always partial which makes it possible to speak about the semantic proximity of words and, in general, about the relations of semantic proximity.

-

35 слайд

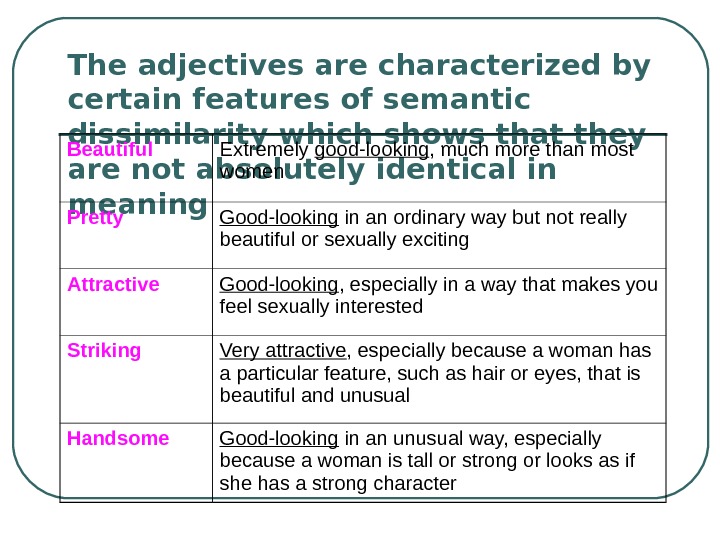

The adjectives are characterized by certain features of semantic dissimilarity which shows that they are not absolutely identical in meaning

-

36 слайд

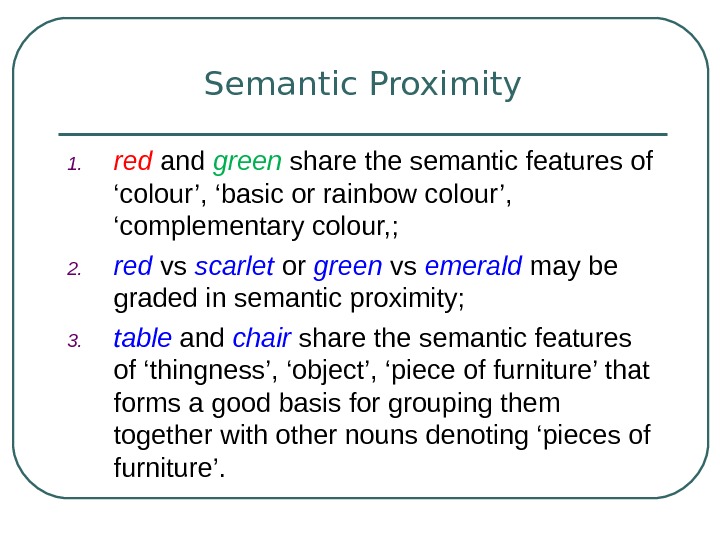

Semantic Proximity

red and green share the semantic features of ‘colour’, ‘basic or rainbow colour’, ‘complementary colour,;

red vs scarlet or green vs emerald may be graded in semantic proximity;

table and chair share the semantic features of ‘thingness’, ‘object’, ‘piece of furniture’ that forms a good basis for grouping them together with other nouns denoting ‘pieces of furniture’. -

37 слайд

2.2. Equivalence

implies full similarity of meaning of two or more language units;

is very seldom observed in words;

Is oftener encountered in case of sentences:

John is taller than Bill = Bill is shorter than John.

She lives in Paris = She lives in the capital of France. -

38 слайд

2.3. INCLUSION. HYPONYMIC STRUCTURE —

type of semantic relations which exists between two words if the meaning of one word contains the semantic features ‘constituting the meaning of the other word’.

The semantic relations of inclusion are called hyponymic relations:

Vehicle: car, lorry, motorcycle, jeep…

Hyperonym: hyponyms. -

39 слайд

The general term – vehicle, tree, animal – is referred to as the classifier or the hyperonym.

The specific term is called the hyponym (car, tram; oak, ash; cat; tiger).

The more specific term (the hyponym) is included in the more general term (the hyperonym), e.g. the classifier move and members of the group – walk, run, saunter. The individual terms contain the meaning of the general term in addition to their individual meanings which distinguish them from each other. -

40 слайд

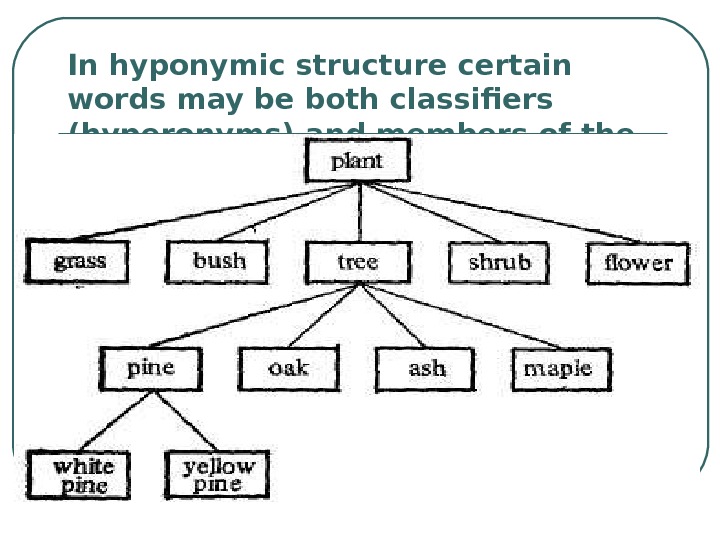

In hyponymic structure certain words may be both classifiers (hyperonyms) and members of the group (hyponyms):

-

41 слайд

The principle of such hierarchical classification is widely used by scientists in various fields of research: botany, geology, etc.

Hyponymic classification may be viewed as objectively reflecting the structure of vocabulary and is considered by many linguists as one of the most important principles for the description of meaning. -

42 слайд

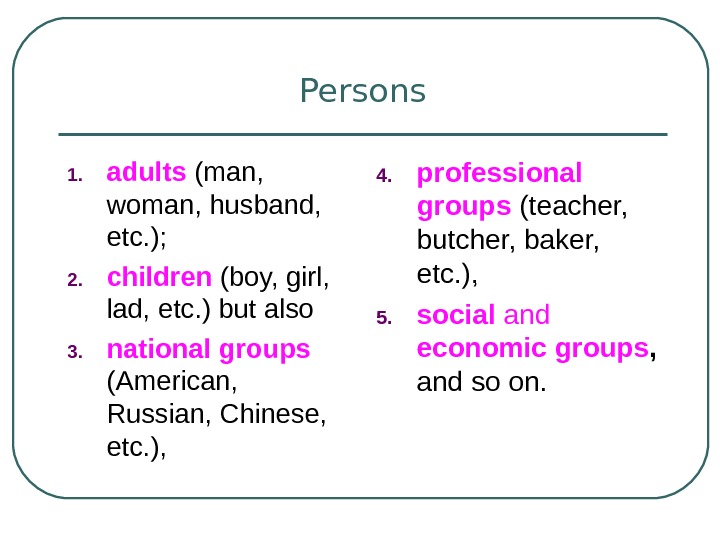

Persons

adults (man, woman, husband, etc.);

children (boy, girl, lad, etc.) but also

national groups (American, Russian, Chinese, etc.),professional groups (teacher, butcher, baker, etc.),

social and economic groups, and so on. -

43 слайд

The problem of great importance for linguists is the dependence of the hierarchical structures of lexical units not only on the structure of the corresponding group of referents in real world but also on the structure of vocabulary in this or that language.

-

44 слайд

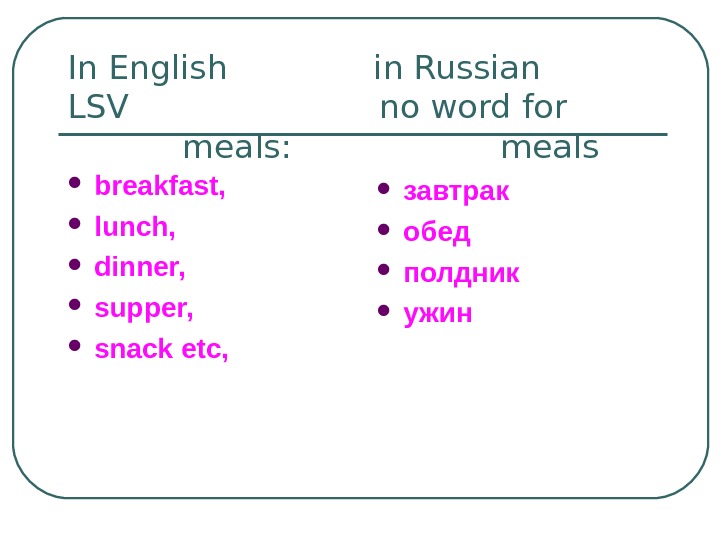

In English in Russian

LSV no word for meals: meals

breakfast,

lunch,

dinner,

supper,

snack etc,

завтрак

обед

полдник

ужин -

45 слайд

2.4. OPPOSITION —

is the contrast of semantic features which helps to establish the semantic relations (black is contrasted to white).

The relations of opposition imply the exclusion of the meaning of one word by another (black is opposed to white but it is not opposed to either red or yellow. In the latter case we can speak about contrast of meaning, but not the semantic relations of opposition. -

46 слайд

Polar oppositions

are those which are based on the semantic feature uniting two linguistic units by antonymous relations,

rich – poor,

dead – alive,

young – old. -

47 слайд

Relative oppositions

imply that there are several semantic features on which the opposition rests. The verb to leave means ‘to go away from’ and its opposite, the verb to arrive denotes ‘to reach a place, esp. at the end of a journey’.

-

48 слайд

Summary and Conclusions:

1. Paradigmatic (or selectional) and syntagmatic (or combinatory) axes of linguistic structure represent the way vocabulary is organised.

Syntagmatic relations define the word-meaning in the flow of speech in various contexts.

Paradigmatic relations define the word-meaning through its interrelation with other members within one of the subgroups of vocabulary units. -

49 слайд

On the syntagmatic axis the word-meaning is dependent on different types of contexts. Linguistic context is the minimal stretch of speech necessary to determine individual meanings.

-

50 слайд

Linguistic (verbal) contexts comprise lexical and grammatical contexts and are opposed to extra-linguistic (non-verbal) contexts. In extra-linguistic contexts the meaning of the word is determined not only by linguistic factors but also by the actual speech situation in which the word is used.

-

51 слайд

The semantic structure of polysemantic words is not homogeneous as far as the status of individual meanings is concerned. A certain meaning (or meanings) is representative of the word taken in isolation, others are perceived only in various contexts.

-

52 слайд

Synonymy and antonymy are correlative and sometimes overlapping notions (частично совпадающие). Synonymous relationship of the denotational meaning is in many cases combined with the difference in the connotational (mainly stylistic) component.

-

53 слайд

It is suggested that the term synonyms should be used to describe words different in sound-form but similar in their denotational meaning (or meanings) and interchangeable at least in some contexts.

-

54 слайд

The term antоnуms is to be applied to words different in sound-form characterised by different types of semantic contrast of the denotational meaning and interchangeable at least in some contexts

-

55 слайд

References:

Гинзбург Р.З. Лексикология английского языка. М. Высшая школа, 1979. – С.- 47-55.

Зыкова И.В. Практический курс английской лексикологии. М.: Академия, 2006. – С. – 39-43.

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 209 351 материал в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 11.01.2021

- 1199

- 13

- 11.01.2021

- 162

- 0

- 11.01.2021

- 5093

- 121

- 11.01.2021

- 636

- 3

- 11.01.2021

- 537

- 3

- 11.01.2021

- 165

- 0

- 11.01.2021

- 146

- 0

- 11.01.2021

- 145

- 0

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация научно-исследовательской работы студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация и предоставление туристских услуг»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Экскурсоведение: основы организации экскурсионной деятельности»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация логистической деятельности на транспорте»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС педагогических направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «История и философия науки в условиях реализации ФГОС ВО»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Риск-менеджмент организации: организация эффективной работы системы управления рисками»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности специалиста оценщика-эксперта по оценке имущества»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация системы менеджмента транспортных услуг в туризме»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Метрология, стандартизация и сертификация»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Осуществление и координация продаж»

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

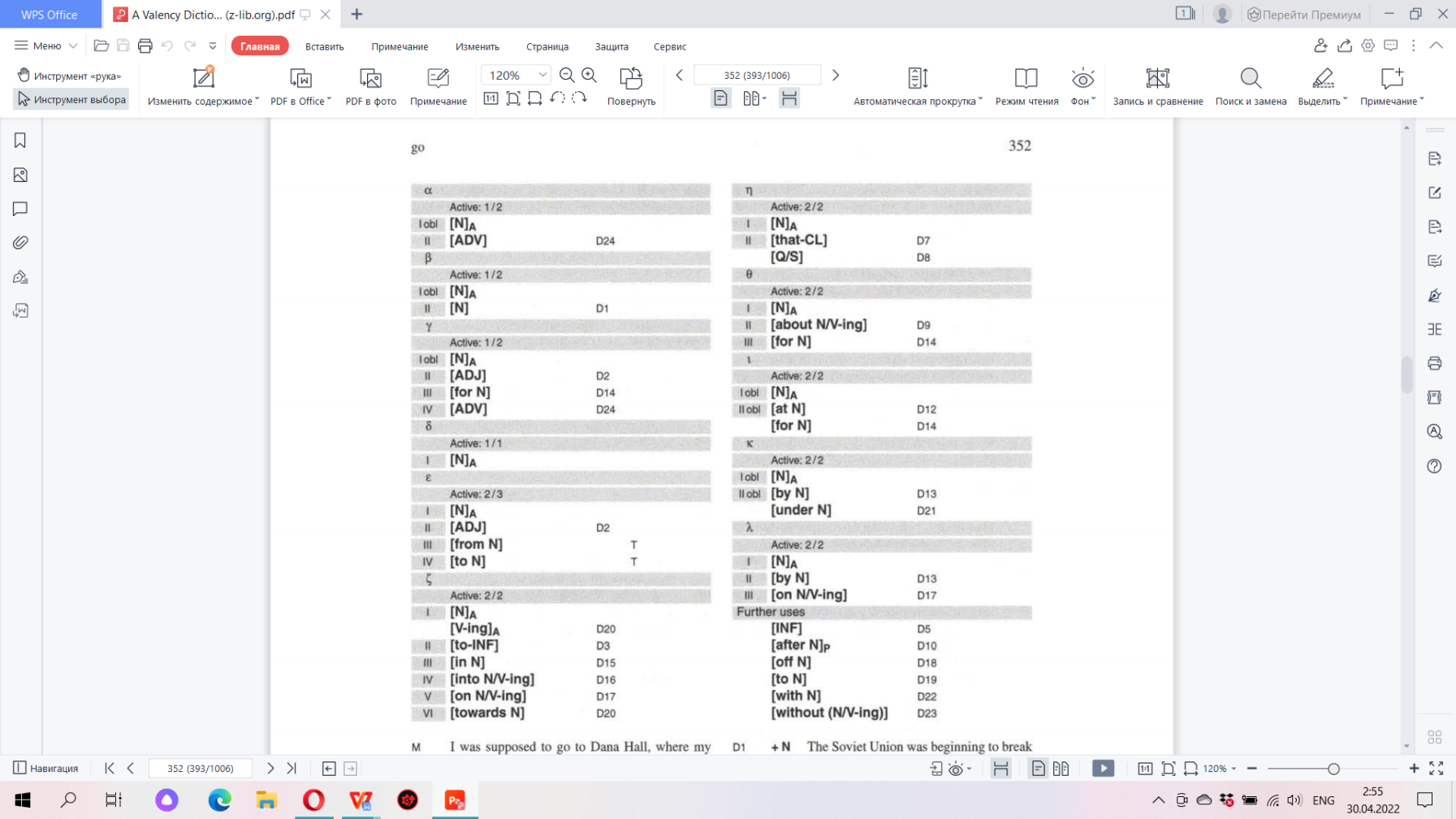

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

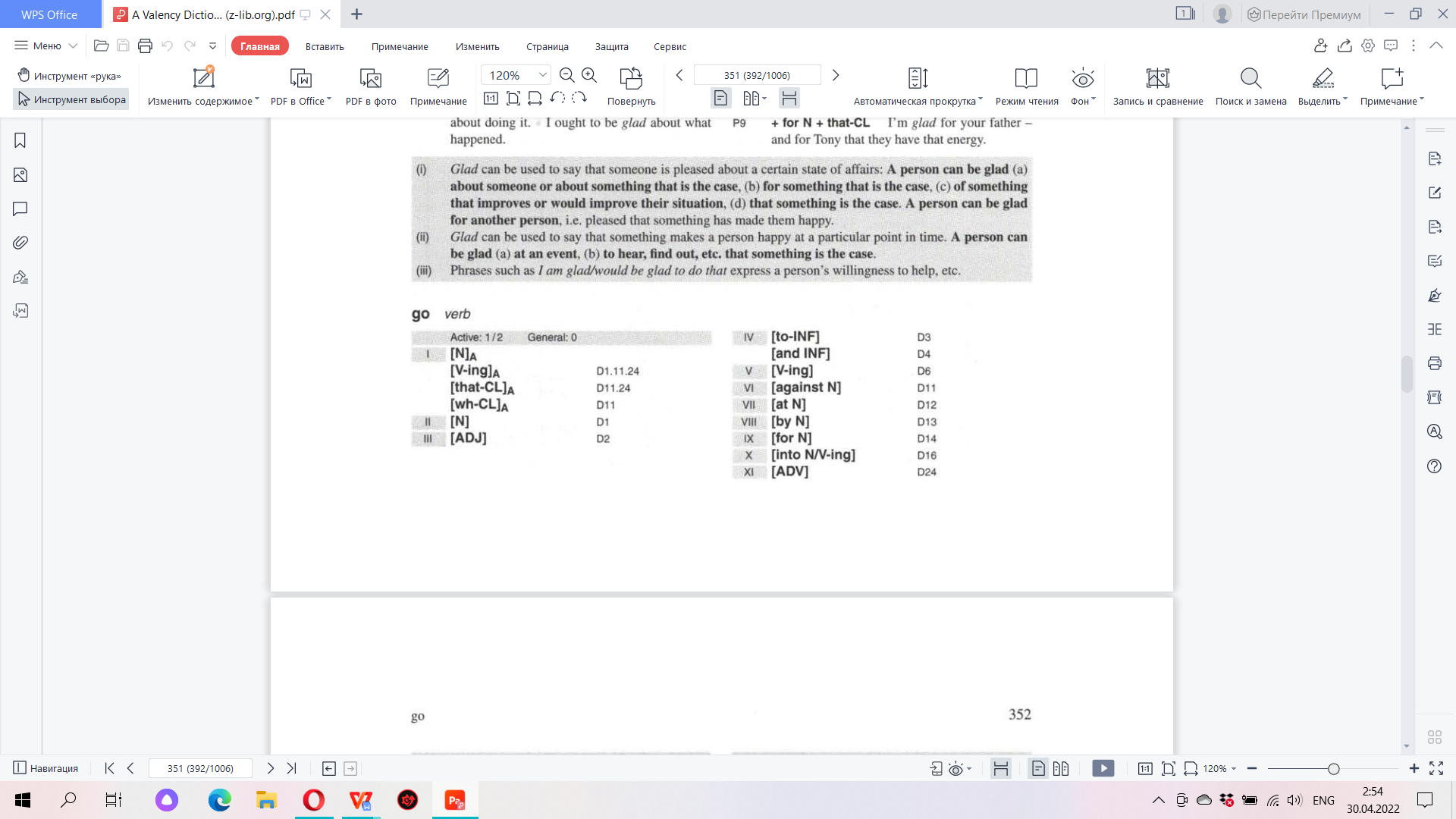

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |

Let’s start with a warmer…

Which of these tasks or exercises

do you normally see in coursebooks?

- Look at the highlighted

verbs in the text and match them with the following synonyms: investigate, find, catch,

escape - Match the adjectives

with their opposites, e.g. tall

/ short - Underline in the text

all the expressions with OF - Group the words

according to categories, e.g. vehicles: car,

motorcycle; musical instruments: guitar, piano etc - Underline all the

adverbs in the text. Now underline the verbs they go with. - Rick says «the

journey was long and tiring». What other adjectives can be used to

describe journeys? - Which is the odd word

out? gaze — smile — stare

— look

You probably answered 1, 2, 4 and 7 and to a lesser extent 3, 5 and

6

Now read on to find out why…

Words in a language can be described in terms of two types of relationships: paradigmatic and syntagmatic. A paradigmatic relationship refers to the relationship between words that are the same parts of speech and which can be substituted for each other in the same position within a given sentence. A syntagmatic relationship refers to the relationship a word has with other words that surround it. In the table below, paradigmatic relationships are shown vertically and syntagmatic relationship — horizontally:

|

acquired |

|||||

|

purchased |

costly |

bicycle |

|||

|

got |

pricey |

old |

motorcycle |

||

|

John |

bought |

a(n) |

expensive |

new |

car |

Click on the tab in the bottom right-hand corner to view in full screen

As you can see, the substitution of one word for another

will not affect the syntax of the sentence.

Paradigmatic (vertical) axis

The words car, motorcycle and bicycle are related to each other because they all belong to the same semantic group: vehicles — a relationship known as hyponymy with a vehicle as a hypernym (a more general or superordinate word) and car, motorcycle and bike as hyponyms (more specific words, in this case types of vehicles). The other two kinds of paradigmatic relationship are those of synonymy (buy = purchase) and antonymy (new / old).

Seen like this, it may seem that any word in a language can be substituted for another. But as Corpus linguistics and Second Language Acquisition research have shown, language doesn’t work in this slot-and-filler fashion and is not stored in the mental lexicon as a giant substitution table. Linear relationships with other words are equally important.

Syntagmatic (horizontal) axis

Unlike the paradigmatic relationships, the syntagmatic relationships of a word are not about meaning. They are about the lexical company the word keeps (collocation) and grammatical patterns in which it occurs (colligation).

Let’s look again at the table / graph above where expensive can be substituted for pricey:

expensive new car

pricey new car

It seems to work, but you’re unlikely to say «costly new car». Also old cannot be easily replaced by new as the combination expensive old is less likely than expensive new. In any case, the opposite of new in this case would probably be used or second-hand and not necessarily old. All these are collocational patterns. But there are also colligational preferences. For example, the words take in and deceive are in a paradigmatic relationship with each other, i.e. they are synonyms. However, take in has a tendency to occur in the passive:

He was taken in by her sob story

rather than «Her sob story took him in»

whereas deceive doesn’t show such grammatical preference.

Wolter and Gylstad (2011), who studied the production of English collocations in L1 Swedish speakers of English, make an interesting observation that paradigmatic relationships tend to be similar across — even vastly different — languages whereas syntagmatic relationships are often arbitrary. For example, in English one goes on a diet, in Greek one “does diet” /’ka;neiß di;aita/, in French one “puts oneself on a diet” /sǝ metR o ReƷim/ and in Russian one “sits on a diet” /sest’ na di;’aitu/.

Therefore in ELT whereas students (and teachers) may derive great pleasure from such activities as putting words in categories (animals: dog, cat, turtle; transport: car, bus, bike) they would probably get more linguistic benefit if they — to put it simply — focused on drive a car and ride a bike, i.e horizontal / syntagmatic relationships.

John Sinclair (2004), the pioneer of corpus linguistics, contends:

the tradition of linguistic theory has been massively

biased in favour of the paradigmatic rather than the

syntagmatic dimension. (p. 140)

I believe, just like in linguistics, the paradigmatic dimension has been overemphasised in the ELT methodology. As you have seen from the warmer, vocabulary teaching in textbooks tends to focus mainly on paradigmatic relationships, e.g matching synonyms and antonyms, grouping words according to sets. However, collocations have also made their way into the mainstream teaching materials in the past 10 or so years.

I have provided some ideas (examples 3, 5 and 6 in the warmer) for focusing on syntagmatic relationships between words. Can you think of other activities and tasks that would highlight the syntagmatic dimension of vocabulary learning? Your ideas are welcome in the comments below.

References

Sinclair, J. M. (2004). Trust the text: Language, corpus and discourse. London and New York: Routledge.

Wolter, B. & Gyllstad, H. (2011). Collocational links in the L2 mental lexicon and the influence of L1 intralexical knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 32(4), 430-449

- Lexicology is the part of linguistics which studies words, their nature(?) and meaning, words’ elements(?), relations between words (semantical relations), word groups and the whole lexicon.

The word «lexicology» derives from the Greek «λεξικόν» (lexicon), neut. of «λεξικός» (lexikos), «of or for words»,[1] from «λέξις» (lexis), «speech», «word»,[2] (in turn from «λέγω» lego «to say», «to speak»[3]) + «-λογία», (-logia), «the study of», a suffix derived from «λόγος» (logos), amongst others meaning «speech, oration, discourse, quote, study, calculation, reason»,[4] it turn also from «λέγω».

The term first appeared in the 1820s, though there were lexicologists in essence before the term was coined.

- General — the general study of words, irrespective of the specific features of any particular language

Special — the description of the vocabulary of a given language

Historical — the study of the evolution of a vocabulary as well as of its elements. This branch discusses the origin of words, their change and development.

Descriptive — deals with the description of the vocabulary of a given language at a given stage of its development.

- English vocabulary as a system

Modern English Lexicology aims at giving a systematic description of the word-stock of Modern English. It treats the following basic problems:

— Basic problems

— Semasiology;

— Word-Structure;

— Word-Formation;

— Etymology of the English Word-Stock;

— Word-Groups and Phraseological Units;

— Variants, dialects of the E. Language;

— English Lexicography.

System is a set of competing possibilities in language, together with the rules for choosing them.

Structuralism recognized that a language is best viewed as a system of elements, with each element being chiefly defined by its place within the system, by the way it is related to other elements.

Language systems:

— speech

— syntactic

— lexical

— morphological

— phonetical

Modern approaches to the problem of study of a language system are characterised by two different levels of study: syntagmatic and paradigmatic.

Paradigmatic relations are the relation between set of linguistic items, which in some sense, constitute choices, so that only one of them may be present at a time in a given position. On the paradigmatic level, the word is studied in its relationships with other words in the vocabulary system.

So, a word may be studied in comparison with other words of similar meaning (e. g. work, n. — labour, n.; to refuse, v. — to reject v. — to decline, v.), of opposite meaning (e. g. busy, adj. — idle, adj.; to accept, v, — to reject, v.), of different stylistic characteristics (e. g. man, n. — chap, n. — bloke, n. — guy, n.).

Consequently, the main problems of paradigmatic studies of vocabulary are:

— synonymy

— hyponymy

— antonymy

— functional styles

Syntagmatic relations

On the syntagmatic level, the semantic structure of the word is analysed in its linear relationships with neighbouring words in connected speech. In other words, the semantic characteristics of the word are observed, described and studied on the basis of its typical contexts, in speech:

— phrases

— collocations

Some collocations are totally predictable, such as spick with span, others are much less so: letter collocates with a wide range of lexemes, such as alphabet and spelling, and (in another sense) box, post, and write.

Collocations differ greatly between languages, and provide a major difficulty in mastering foreign languages. In English, we ‘face’ problems and ‘interpret’ dreams; but in modern Hebrew, we have to ‘stand in front of problems and ‘solve’ dreams.

The more fixed a collocation is, the more we think of it as an ‘idiom’ — a pattern to be learned as a whole, and not as the ‘sum of its parts’.

Combination of paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations in lexical system determines vocabulary as a system.

- One of the earliest and most obvious non-semantic grouping is the alphabetical organization of the word-stock, which is represented in most dictionaries. It is of great practical value in the search for the necessary word, but its theoretical value is almost null, because no other property of the word can be predicted from the letter or letters the word begins with.

Morphological groupings.

On the morphological level words are divided into four groups according to their morphological structure:

1) root or morpheme words (dog, hand);

2) derivatives, which contain no less than two morphemes (dogged (ynpямый), doggedly; handy, handful);

3) compound words consisting of not less than two free morphemes (dog-cheap-«very cheap», dog-days — «hottest part of the year»; handbook, handball)

4) compound derivatives (dog-legged — «crooked or bent like a dog’s hind leg», left-handed).

This grouping is considered to be the basis for lexicology.

Another type of traditional lexicological grouping as known as word-families such as: hand, handy, handicraft, handbag, handball, handful, hand-made,handsome, etc.

A very important type of non-semantic grouping for isolated lexical units is based on a statistical analysis of their frequency. Frequency counts carried out for practical purposes of lexicology, language teaching and shorthand show important correlations between quantative and qualitative characteristics of lexical units, the most frequent words being polysemantic and stylistically neutral. The frequency analysis singles out two classes:

1) notional words;

2) form (or functional) words.

Notional words constitute the bulk of the existing word-stock, according to the recent counts given for the first 1000 most frequently occurring words they make up 93% of the total number.

All notional lexical units are traditionally subdivided into parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs. Nouns numerically make the largest class — about 39% of all notional words; verbs come second — 25% of words; they are followed by adjectives — 17% and adverbs — 12%.

Form or functional words — the remaining 7% of the total vocabulary — are prepositions, articles, conjunctions, which primarily denote various relations between notional words. Their grammatical meaning dominates over their lexical meaning. They make a specific group of about 150 units.

Lexico-grammatical grouping.

By a lexico-grammatical group we understand a class of words which have a common lexico-grammatical meaning, a common paradigm, the same substituting elements and possibly a characteristic set of suffixes rendering the lexico-grammatical meaning.

Lexico-grammatical groups should not be confused with parts of speech. For instance, audience and honesty belong to the same part of speech but to different lexico-grammatical groups because their lexico-grammatical meaning is different.

Common Denominator of Meaning, Semantic Fields.

Words may also be classified according to the concepts underlying their meaning. This classification is closely connected with the theory of semantic fields. By the term «semantic fields» we understand closely knit sectors of vocabulary each characterized by a common concept. The words blue, red, yellow, black, etc. may be described as making up the semantic field of colours, the words mother, father, sister, cousin, etc. — as members of the semantic field of kinship terms, the words joy, happiness, gaiety, enjoyment, etc. as belonging to the field of pleasurable emotions, and so on.

The members of the semantic fields are not synonymous but all of them are joined together by some common semantic component — the concept of colours or the concept of kinship, etc. This semantic component common to all members of the field is sometimes described as the common denominator of meaning. All members of the field are semantically interdependent as each member helps to delimit and determine the meaning of its neighbours and is semantically delimited and determined by them. It follows that the word meaning is to a great extent determined by the place it occupies in its semantic field.

It is argued that we cannot possibly know the exact meaning of the word if we do not know the structure of the semantic field to which the word belongs, the number of the members and the concepts covered by them, etc. The meaning of the word captain, e.g. cannot be properly understood until we know the semantic field in which this term operates — the army, the navy, or the merchant service. It follows that the meaning of the word captain is determined by the place it occupies among the terms of the relevant rank system. In other words we know what captain means only if we know whether his subordinate is called mate or first officer (merchant service), commander (navy) or lieutenant (army).

Semantic dependence of the word on the structure of me field may be also illustrated by comparing members of analogous conceptual fields in different languages. Comparing, e.g. kinship terms in Russian and in English we observe that the meaning of the English term mother-in-law is different from either the Russian тёща or свекровь, as the English term covers the whole area which in Russian is divided between the two words. The same is true of the members of the semantic field of colours (cf. blue — синий, голубой), of human body (cf. hand, arm — рука) and others.

The theory of semantic field is severely criticized by Soviet linguists mainly on philosophical grounds as some of the proponents of the semantic-field theory hold the idealistic view that language is a kind of self-contained entity standing between man and the world of reality (Zwischenwelt). The followers of this theory argue that semantic fields reveal the fact that human experience is analysed and elaborated in a unique way, differing from one language to another. Broadly speaking they assert that people speaking different languages actually have different concepts, as it is through language that we see the real world around us. In short, they deny the primacy of matter forgetting that our concepts are formed not only through linguistic experience, but primarily through our actual contact with the real world. We know what hot means not only because we know the word hot, but also because we burn our fingers when we touch something very hot. A detailed critical analysis of the theory of semantic fields is the subject-matter of general linguists. Here we are concerned with the theory only as a means of semantic classification of vocabulary items.

Two more points should be discussed in this connection. Firstly, semantic groups may be very extensive and may cover big conceptual areas, e.g. man-universe, etc. There may be, however, comparatively small lexical groups of words linked by a common denominator of meaning. The words bread, cheese, milk, meat, etc. make up the semantic field with the concept of food as the common denominator of meaning. Such smaller lexical groups seem to play a very important role in determining individual meanings of polysemantic words in lexical contexts. Analysing polysemantic verbs we see that the verb take, e.g. in combination with the lexical group denoting means of transportation is synonymous with the verb go (take the tram, the bus, etc.). When combined with members of another lexical group possessing another semantic denominator, the same verb is synonymous with to drink (to take tea, coffee, etc.). Such word-groups are often used not only in scientific lexicological analysis, but also in practical class-room teaching. In a number of textbooks we find words with some common denominator of meaning listed under the headings Flower, Fruit, Domestic Animals, and so on.

In other words lexical or semantic field is the organization of related words and expressions into a system which shows their relationship to one another.

For example, kinship terms such as father, mother, sister, brother, uncle, aunt belong to a lexical field whose relevant features include generation, sex, membership of the father’s or mother’s side of the family, etc.

The absence of a word in a particular place in a lexical field of a language is called a lexical gap.

For example, in English there is no singular noun that covers both cow and bull as hoarse covers stallion and mare.

Common Contextual Associations. Thematic Groups.

Another type of classification almost universally used in practical class-room teaching is known as thematic grouping. Classification of vocabulary items into thematic groups is based on the co-occurrence of words in certain repeatedly used contexts.

In linguistic contexts co-occurrence may be observed on different levels. On the level of word-groups the word question, e.g., is often found in collocation with the verbs raise, put forward, discuss, etc., with the adjectives urgent, vital, disputable and so on. The verb accept occurs in numerous contexts together with the nouns proposal, invitation, plan and others.

As a rule, thematic groups deal with contexts on the level of the sentence (or utterance). Words in thematic groups are joined together by common contextual associations within the framework of the sentence and reflect the interlinking words, e.g. tree-grow-green; journey-train-taxi-bags-ticket or sun-shine-brightly-blue-sky, is due to the regular co-occurrence of these words in similar sentences. Unlike members of synonymic sets or semantic fields, words making up a thematic group belong to different parts of speech and do not possess any common denominator of meaning.

Contextual associations formed by the speaker of a language are usually conditioned by the context of situation which necessitates the use of certain words. When watching a play, e.g., we naturally speak of the actors who act the main parts, of good (or bad) staging of the play, of the wonderful scenery and so on. When we go shopping it is usual to speak of the prices, of the goods we buy, of the shops, etc. (In practical language learning thematic groups are often listed under various headings, e.g. At the Theatre, At School, Shopping, and are often found in text-books and courses of conversational English).

Thematic and ideographic organization of a vocabulary.

It is a further subdivision within the lexico-grammatical grouping. The basis of grouping is not only linguistic but also extra-linguistic. The words are associated because the things they name occur together and are closely connected in reality, e.g., terms of kinship. Names of parts of the human body, colour terms, etc.

The ideographic groupings are independent of classification into parts of speech, as grammatical meaning is not taken into consideration. Words and expressions are here classed not according to their lexico-grammatical meaning but strictly according to their signification, i.e. to their system of logical notions. These subgroups may compare nouns, verbs adjectives and adverbs together, provided they refer to the same notion. Under alphabetical order the words which in the human mind go close together (father, brother, uncle, etc.) are placed in various parts of a dictionary. So, some lexicographers place such groups of lexical units in the company they usually keep in every day life, in our minds. These dictionaries are called ideographical or ideological.

Synonymic grouping is a special case of lexico-grammatical grouping based on semantic proximity of words belonging to the same part of speech. Taking up similarity of meaning and contrasts of phonetic shape we observe that every language in its vocabulary has a variety of words kindred (родственный) or similar in meaning but distinct in morphemic composition, phonetic shape and usage. These words express the most delicate shades of thought, feelings and are explained in the dictionaries of synonyms.

Antonyms have been traditionally defined as words of opposite meaning. Their distinction from synonyms is semantic polarity. The English language is rich in synonyms and antonyms, their study reveals the systematic character of the English vocabulary.

Special terminology.

Sharply defined extensive semantic fields are found in terminological systems. Terminology constitutes the greatest part of every language vocabulary. A term is a word or word-group used to name a notion characteristic of some special field of knowledge, e.g., linguistics, cybernetics, industry, culture, informatics. Almost every system of terms is nowadays fixed and analyzed in numerous special dictionaries of the English language. ?

Hyponymy (включение).