Proceeding

from the differences in linguistic signs we claim that word-signs be

subdivided into two principal groups: lexical words and grammatical

words.

Lexical

words

are the linguistic signs which possess denotative

ability. They are denotators of extralingual objects and phenomena,

objective and subjective: a

window, a country, to judge,

etc. Their function consists in nominating or designating the denoted

objects and phenomena. The nominative character of denotative words,

which correlate with notions and have full denotative content, helps

to distinguish

nominative

words

from

non-nominative ones. Lexical

words in contrast to “grammatical words’’are nominative units

which function as lingual nominators of denoted referents.

The

term “notional”, however acceptable it might be, is not probably

exact because, in fact, all words, this way or another, correlate

with notions. But the correlative notions may be different, and the

ways of correlation may differ too. The term seems somewhat

misleading. Grammar resorts to it but interprets it conventionally as

a designation of denotative units only.

Grammatical

words are

also linguistic signs but they possess significative ability.

They

are

significators of general conceptual notions.

They

do not designate or nominate them as the word “significate”

itself

does.

They

may or may not have reference to objective reality.If they have any,

grammatical words are said to possess certain referential and

reflective ability. The significative character of the main stock of

grammatical words is obvious. This results from their function of

signification, i.e. the representation of general conceptual notions

(categories) not in the way of nominating but by signifying or

marking them grammatically. Hence, it is the way of lingual

representation and the nature of conceptual referents, significative

generic notions or categories, that predetermine the specific

lingual function of signification. Nomination and signification

are correlative and distinctive they lie at the basis of

differentiating lexical words from grammatical ones.

Since

grammatical words are devoid of nominative power they can be

characteristically qualified as “function-words”, i. e. words

attributed with particular functional design such as to signify

conceptual categories, to form up language units in their

function and relationships or to provide orientation in speech

situations. The functionality of grammatical words makes it

necessary to regard them together with other grammatical devices of

linguistic means of expression. Both types of words are bilateral

entities having their content and expression sides.

The

notion of ‘grammatical meaning’.

The word

combines in its semantic structure two meanings – lexical and

grammatical. Lexical

meaning

is the individual meaning of the word (e.g. table).

Grammatical

meaning

is the meaning of the whole class or a subclass. For example, the

class of nouns has the grammatical meaning of thingness.

If we take a noun (table)

we may say that it possesses its individual lexical meaning (it

corresponds to a definite piece of furniture) and the grammatical

meaning of thingness

(this is the meaning of the whole class). Besides, the noun ‘table’

has the grammatical meaning of a subclass – countableness.

Any verb combines its individual lexical meaning with the grammatical

meaning of verbiality – the ability to denote actions or states. An

adjective combines its individual lexical meaning with the

grammatical meaning of the whole class of adjectives –

qualitativeness – the ability to denote qualities. Adverbs possess

the grammatical meaning of adverbiality – the ability to denote

quality of qualities.

There are some classes of

words that are devoid of any lexical meaning and possess the

grammatical meaning only. This can be explained by the fact that they

have no referents in the objective reality. All function words belong

to this group – articles, particles, prepositions, etc.

Types of grammatical

meaning.

The

grammatical meaning may be explicit and implicit. The implicit

grammatical

meaning is not expressed formally (e.g. the word table

does

not contain any hints in its form as to it being inanimate). The

explicit

grammatical

meaning is always marked morphologically – it has its marker. In

the word cats

the

grammatical meaning of plurality is shown in the form of the noun;

cat’s

–

here the grammatical meaning of possessiveness is shown by the form

‘s;

is

asked –

shows the explicit grammatical meaning of passiveness.

The

implicit grammatical meaning may be of two types – general and

dependent. The general

grammatical meaning is the meaning of the whole word-class, of a part

of speech (e.g. nouns – the general grammatical meaning of

thingness). The dependent

grammatical meaning is the meaning of a subclass within the same part

of speech. For instance, any verb possesses the dependent grammatical

meaning of transitivity/intransitivity,

terminativeness/non-terminativeness, stativeness/non-stativeness;

nouns have the dependent grammatical meaning of

contableness/uncountableness and animateness/inanimateness. The most

important thing about the dependent grammatical meaning is that it

influences the realization of grammatical categories restricting them

to a subclass. Thus the dependent grammatical meaning of

countableness/uncountableness influences the realization of the

grammatical category of number as the number category is realized

only within the subclass of countable nouns, the grammatical meaning

of animateness/inanimateness influences the realization of the

grammatical category of case, teminativeness/non-terminativeness —

the category of tense, transitivity/intransitivity – the category

of voice.

GRAMMATICAL

MEANING

EXPLICIT

IMPLICIT

GENERAL

DEPENDENT

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

Parts of this article (those related to work since the 2000s) need to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2019) |

In linguistics, the lexical aspect or Aktionsart (German pronunciation: [ʔakˈtsi̯oːnsˌʔaʁt], plural Aktionsarten [ʔakˈtsi̯oːnsˌʔaɐ̯tn̩]) of a verb is part of the way in which that verb is structured in relation to time. For example, the English verbs arrive and run differ in their lexical aspect since the former describes an event which has a natural endpoint while the latter does not. Lexical aspect differs from grammatical aspect in that it is an inherent semantic property of a predicate, while grammatical aspect is a syntactic or morphological property. Although lexical aspect need not be marked morphologically, it has downstream grammatical effects, for instance that arrive can be modified by «in an hour» while believe cannot.

Theories of aspectual class[edit]

Although all theories of lexical aspect recognize that verbs divide into different classes, the details of the classification differ. An early attempt by Vendler recognized four classes, which has been modified several times.

Vendler’s classification[edit]

Zeno Vendler classified verbs into four categories on whether they express «activity», «accomplishment», «achievement» or «state». Activities and accomplishments are distinguished from achievements and states in that the first two allow the use of continuous and progressive aspects. Activities and accomplishments are distinguished from each other by boundedness. Activities do not have a terminal point (a point before which the activity has taken place and after which cannot continue: «John drew a circle»), but accomplishments have one. Of achievements and states, achievements are instantaneous, but states are durative. Achievements and accomplishments are distinguished from one another in that achievements take place immediately (such as in «recognise» or «find»), but accomplishments approach an endpoint incrementally (as in «paint a picture» or «build a house»).[1][2]

Comrie’s classification[edit]

In his discussion of lexical aspect, Bernard Comrie included the category semelfactive or punctual events such as «sneeze». His divisions of the categories were as follows: states, activities, and accomplishments are durative, but semelfactives and achievements are punctual. Of the durative verbs, states are unique as they involve no change, and activities are atelic (that is, have no «terminal point») whereas accomplishments are telic. Of the punctual verbs, semelfactives are atelic, and achievements are telic. The following table shows examples of lexical aspect in English that involve change (an example of a state is ‘know’).[1][3]

| Punctual | Durative | |

|---|---|---|

| Telic | Achievement (to release) |

Accomplishment (to drown) |

| Atelic | Semelfactive (to knock) |

Activity (to walk) |

| Static | State (to know) |

Moens and Steedman’s classification[edit]

Another classification is proposed by Moens and Steedman, based on the idea of the event nucleus[4]

| Event nucleus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparatory

phase |

Culminating

event |

Consequent

phase |

|

| Semelfactive | |||

| State | |||

| Activity | |||

| Achievement | |||

| Accomplishment |

Syntactic analyses of event structure[edit]

Aspectual classes can be analyzed as differing in their event structure, and this has led to the development of syntactic analyses of event structure, with each aspectual class treated as having a distinct syntactic structure.

See also[edit]

- Predicate

- Syntax–semantics interface

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rothstein, Susan (2016). «Aspect». In Aloni, Maria; Dekker, Paul (eds.). Cambridge Handbook of Formal Semantics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02839-5.

- ^ Vendler, Zeno (1957). «Verbs and Times» (PDF). The Philosophical Review. 66 (2): 143–160. doi:10.2307/2182371. JSTOR 2182371.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (1976). Aspect: An Introduction to the Study of Verbal Aspect and Related Problems. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9784838401000.

- ^ Moens, Marc; Steedman, Mark (1988). «Temporal ontology and temporal reference» (PDF). Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics. 14 (2): 15–28. ISSN 0362-613X.

Слайд 1Aspects of Lexical Meaning

Lecture

Слайд 2ASPECTS OF LEXICAL MEANING

THE DENOTATIONAL ASPECT

THE CONNOTATIONAL ASPECT

THE PRAGMATIC ASPECT

COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

Слайд 31. THE DENOTATIONAL ASPECT

The denotational aspect of lexical meaning is the

part of lexical meaning which establishes correlation between the name and the object, phenomenon, process or characteristic feature of concrete reality (or thought), which is denoted by the given word.

e.g. booklet — ‘a small thin book that gives information about something’

Слайд 4Through the denotational aspect of meaning the bulk of information is

conveyed in the process of communication.

The denotational aspect of lexical meaning:

expresses the notional content of a word.

is the component of the lexical meaning that makes communication possible.

Слайд 52. THE CONNOTATIONAL ASPECT

The connotational aspect of lexical meaning is the

part of meaning which reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about. Connotation conveys additional information in the process of communication.

Слайд 6Connotation includes:

The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features

proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning, e.g. daddy as compared to father.

a hovel – ‘a small house or cottage’ – implies a miserable dwelling place, dirty, in bad repair and in general unpleasant to live in.

Слайд 8Evaluation, which may be positive or negative, e.g.

clique (a small

group of people who seem unfriendly to other people) as compared to group (a set of people);

celebrated (widely known for special achievement in science, art, sport, etc.) as compared to notorious (widely known for criminal act or bad traits of character).

Слайд 9Imagery:

to wade – to walk with an effort (through mud,

water or anything that makes progress difficult). The figurative use of the word gives rise to another meaning, which is based on the same image as the first – to wade through a book ;

Слайд 10intensity/expressiveness, e.g. to adore – to worship – to love –

to like;

connotation of cause, duration etc.

Слайд 14Thus, a meaning can have two or more connotational components.

The given

examples present only a few: emotive, evaluative connotations, and also connotations of duration and of cause.

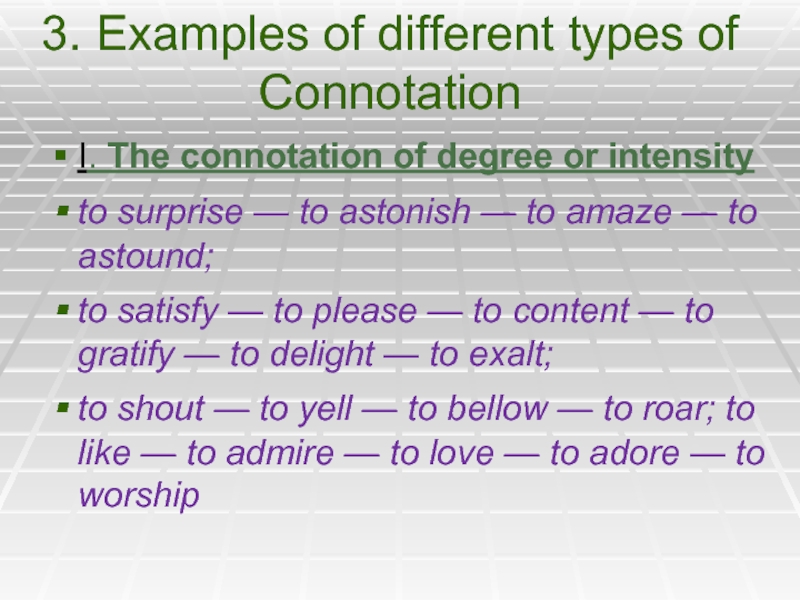

Слайд 153. Examples of different types of Connotation

I. The connotation of degree

or intensity

to surprise — to astonish — to amaze — to astound;

to satisfy — to please — to content — to gratify — to delight — to exalt;

to shout — to yell — to bellow — to roar; to like — to admire — to love — to adore — to worship

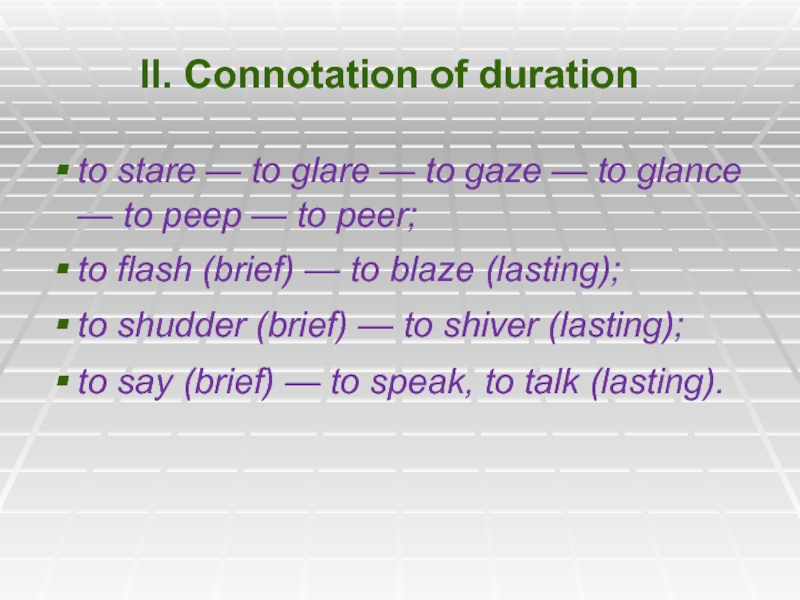

Слайд 16II. Connotation of duration

to stare — to glare — to gaze

— to glance — to peep — to peer;

to flash (brief) — to blaze (lasting);

to shudder (brief) — to shiver (lasting);

to say (brief) — to speak, to talk (lasting).

Слайд 17III. Emotive connotations

to stare — to glare — to gaze;

alone —

single — lonely — solitary;

to tremble — to shiver — to shudder — to shake;

to love — to admire — to adore — to worship;

angry — furious — enraged;

fear — terror — horror.

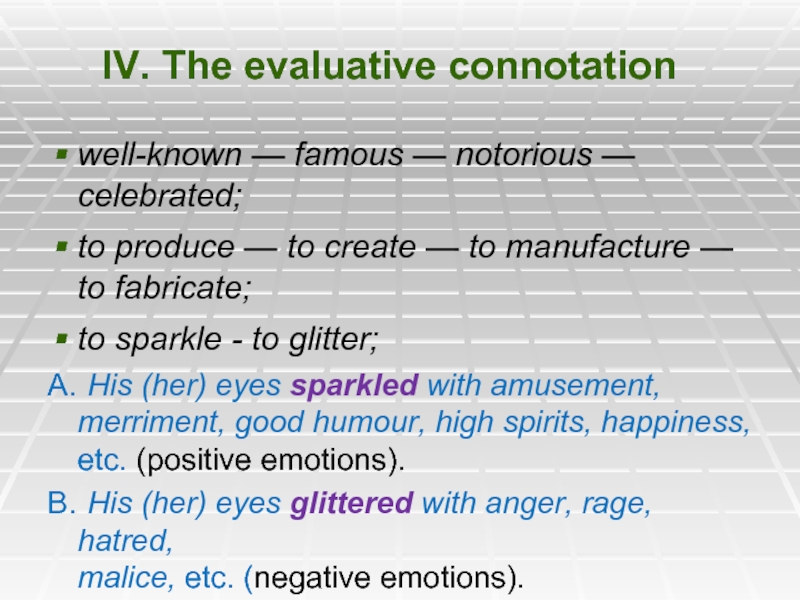

Слайд 18IV. The evaluative connotation

well-known — famous — notorious — celebrated;

to produce

— to create — to manufacture — to fabricate;

to sparkle — to glitter;

A. His (her) eyes sparkled with amusement, merriment, good humour, high spirits, happiness, etc. (positive emotions).

B. His (her) eyes glittered with anger, rage, hatred,

malice, etc. (negative emotions).

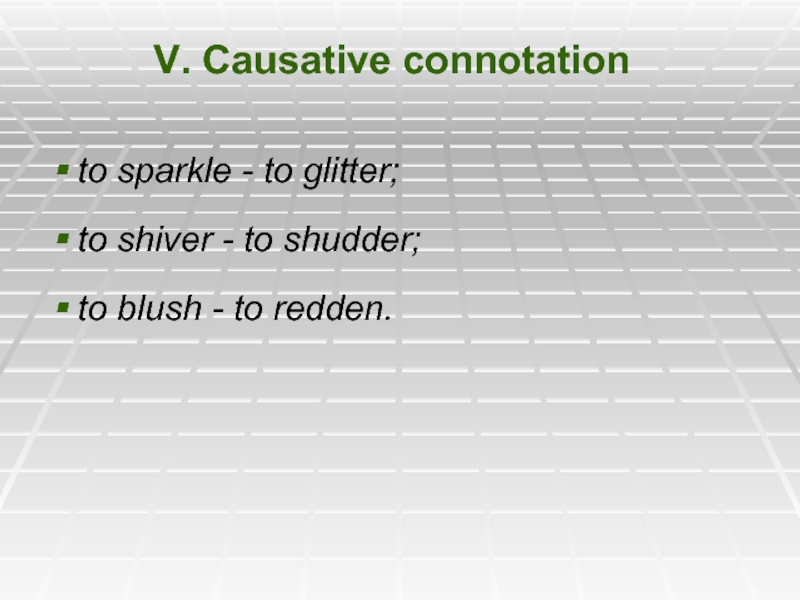

Слайд 19V. Causative connotation

to sparkle — to glitter;

to shiver — to shudder;

to

blush — to redden.

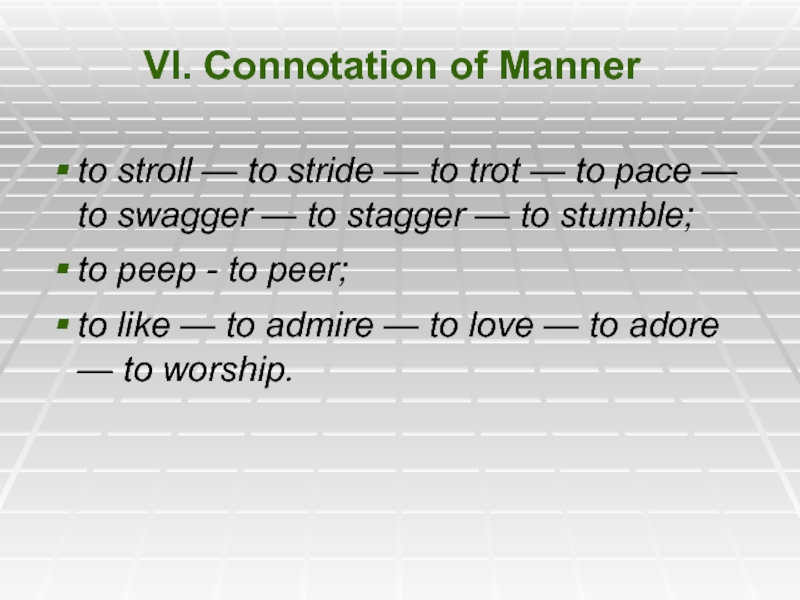

Слайд 20VI. Connotation of Manner

to stroll — to stride — to trot

— to pace — to swagger — to stagger — to stumble;

to peep — to peer;

to like — to admire — to love — to adore — to worship.

Слайд 21VII. The connotation of attendant circumstances

One peeps at smb./smth. through a

hole, crack or opening, from behind a screen, a half-closed door, a newspaper, a fan, a curtain, etc. It seems as if a whole set of scenery were built within the word’s meaning. It is not quite so, because «the set of scenery» is actually built in the context, but, as with all regular contexts, it is intimately reflected in the word’s semantic structure.

Слайд 22One peers at smb./smth. in darkness, through the fog, through dimmed

glasses or windows, from a great distance; a short-sighted person may also peer at things. So, in the semantic structure of to peer are encoded circumstances preventing one from seeing clearly.

Слайд 23VII. Connotation of attendant features

Pretty – handsome – beautiful;

special types

of human beauty:

beautiful is mostly associated with classical features and a perfect figure;

handsome with a tall stature, a certain robustness and fine proportions,

pretty with small delicate features and a fresh complexion.

Слайд 24IX. Stylistic connotations

(Meal). Snack, bite (coll.), snap (dial.), repast, refreshment, feast

(formal).

These synonyms, besides stylistic connotations, have connotations of attendant features.

Snack, bite, snap all denote a frugal meal taken in a hurry; refreshment is also a light meal; feast is a rich or abundant meal.

(Girl). Girlie (coll.), lass, lassie (dial.), bird, birdie, jane, fluff, skirt (sl.), maiden (poet.), damsel (arch.).

Слайд 25Anecdote

J a n e: Would you be insulted if that

good-looking stranger offered you some champagne?

J o a n: Yes, but I’d probably swallow the insult.

Слайд 263. THE PRAGMATIC ASPECT

The pragmatic aspect is the part of lexical

meaning that conveys information on the situation of communication. Like the connotational aspect, the pragmatic aspect falls into four closely linked together subsections.

Слайд 27

1. Information on the ‘time and space’ relationship of the participants

Some

information which specifies different parameters of communication may be conveyed not only with the help of grammatical means (tense forms, personal pronouns, etc), but through the meaning of the word.

E.g. come and go can indicate the location of the speaker who is usually taken as the zero point in the description of the situation of communication

Слайд 28The time element is fixed indirectly. Indirect reference to time implies

that the frequency of occurrence of words may change with time and in extreme cases words may be out of use or become obsolete.

E.g.the word behold – ‘take notice, see (smth unusual)’ as well as the noun beholder – ‘spectator’ are out of use now but were widely used in the 17th century.

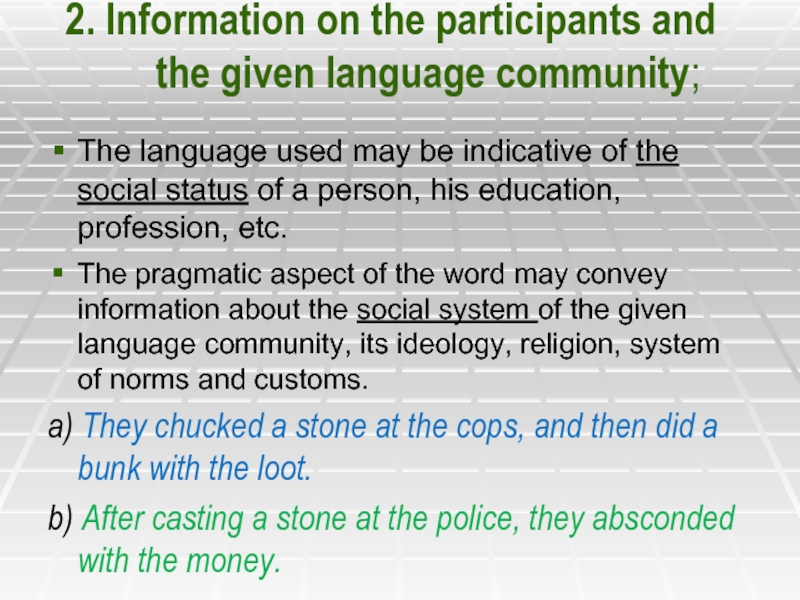

Слайд 292. Information on the participants and the given language community;

The language

used may be indicative of the social status of a person, his education, profession, etc.

The pragmatic aspect of the word may convey information about the social system of the given language community, its ideology, religion, system of norms and customs.

a) They chucked a stone at the cops, and then did a bunk with the loot.

b) After casting a stone at the police, they absconded with the money.

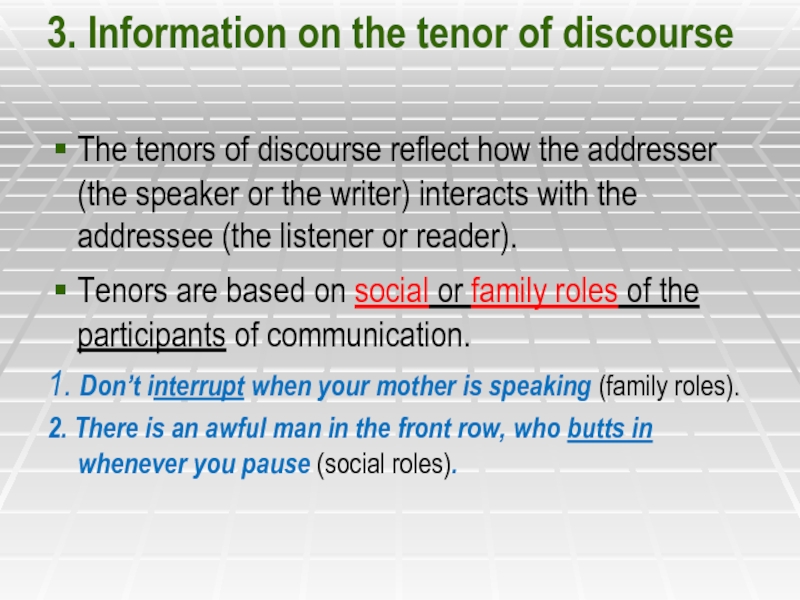

Слайд 303. Information on the tenor of discourse

The tenors of discourse reflect

how the addresser (the speaker or the writer) interacts with the addressee (the listener or reader).

Tenors are based on social or family roles of the participants of communication.

1. Don’t interrupt when your mother is speaking (family roles).

2. There is an awful man in the front row, who butts in whenever you pause (social roles).

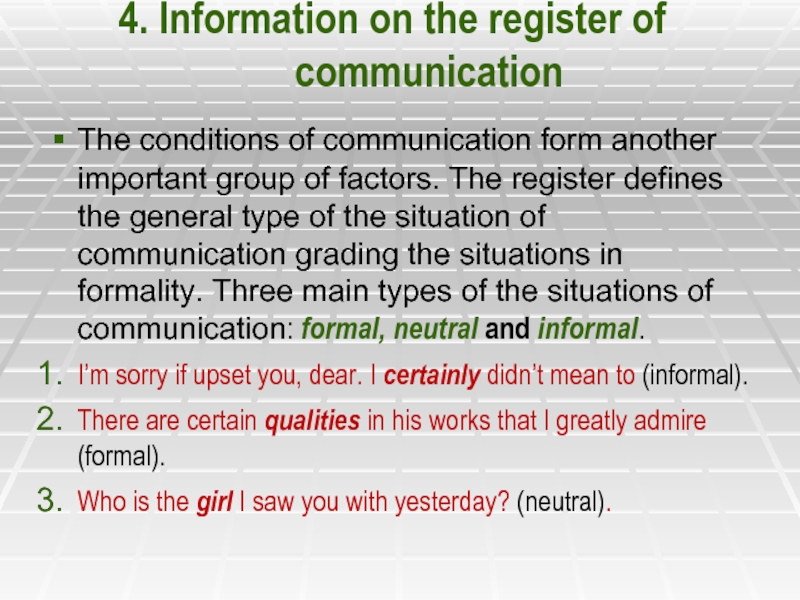

Слайд 314. Information on the register of communication

The conditions of

communication form another important group of factors. The register defines the general type of the situation of communication grading the situations in formality. Three main types of the situations of communication: formal, neutral and informal.

I’m sorry if upset you, dear. I certainly didn’t mean to (informal).

There are certain qualities in his works that I greatly admire (formal).

Who is the girl I saw you with yesterday? (neutral).

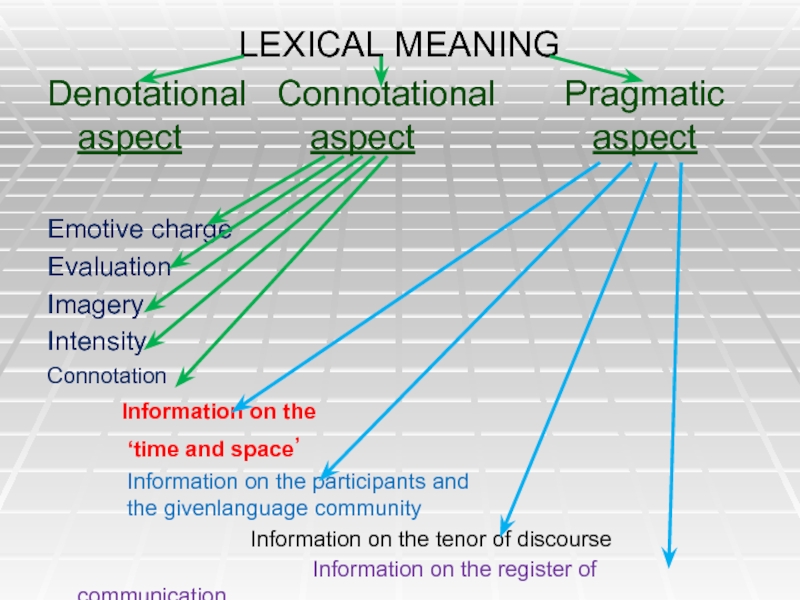

Слайд 32LEXICAL MEANING

Denotational Connotational Pragmatic aspect

aspect aspect

Emotive charge

Evaluation

Imagery

Intensity

Connotation

Information on the

‘time and space’

Information on the participants and

the givenlanguage community

Information on the tenor of discourse

Information on the register of communication

Слайд 33IV. Componential analysis = semantic decomposition

rests upon the thesis that

the sense of every lexeme can be analyzed in terms of a set of more general sense components or semantic features, some or all of which will be common to several different lexemes in the vocabulary.

Слайд 34Componential analysis

attempts to treat components according to ‘binary’ opposition:

male/

female,

animate/ inanimate,

adult/ non-adult,

human/ non-human.

The sense of man might be held to combine the concepts (male, adult, human).

The sense of woman might be held to differ from man in that it combines (female (not male), adult, human).

Слайд 35Componential analysis allows us to group entities into natural classes.

man

and boy (human, male),

man and woman (human, adult).

There are certain verbs, such as marry, argue, that are found with subjects that are [+human]. Moreover, within the English pronoun system, he is used to refer to [human] entities that are [+male] while she is used for [human] entities that are [not male].

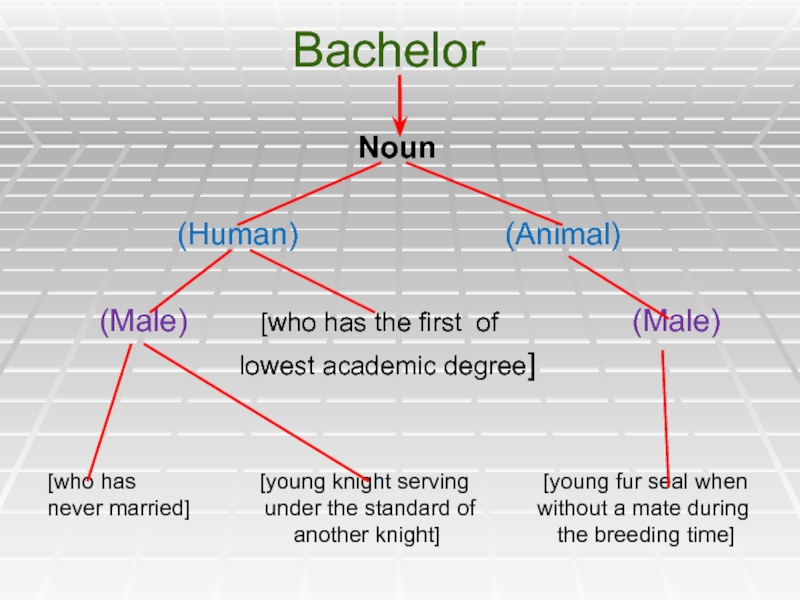

Слайд 36Componential analysis of the word ‘bachelor’

According to the dictionary it has

4 meanings:

a man who has never married (холостяк);

a young knight (рыцарь);

someone with a first degree (бакалавр);

a young male unmated fur seal (морской котик) during the mating season.

Слайд 37Bachelor

Noun

(Human) (Animal)

(Male) [who has the first of (Male)

lowest academic degree]

[who has [young knight serving [young fur seal when

never married] under the standard of without a mate during

another knight] the breeding time]

[who has never [young knight serving [young fur seal when

married] under the standard of without a mate during

another knight] the breeding time]

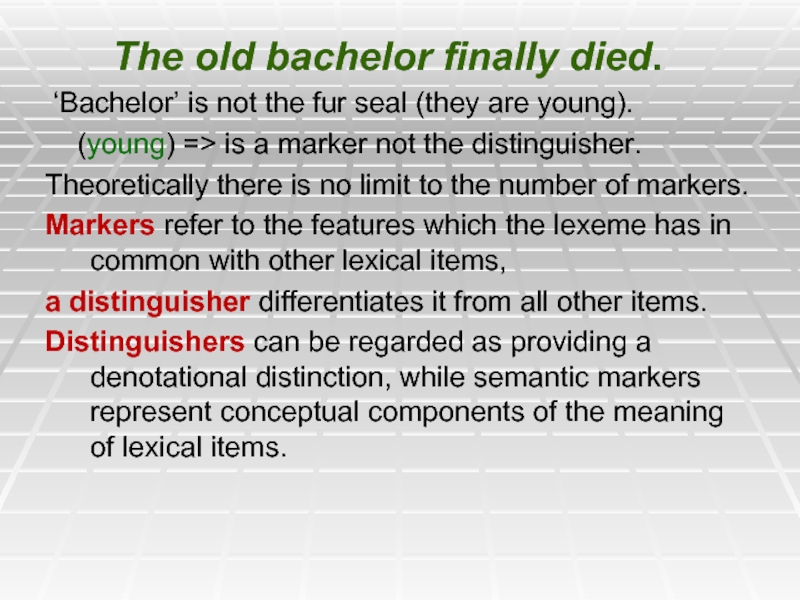

Слайд 38The old bachelor finally died.

‘Bachelor’ is not the fur

seal (they are young).

(young) => is a marker not the distinguisher.

Theoretically there is no limit to the number of markers.

Markers refer to the features which the lexeme has in common with other lexical items,

a distinguisher differentiates it from all other items.

Distinguishers can be regarded as providing a denotational distinction, while semantic markers represent conceptual components of the meaning of lexical items.

Слайд 39Componential analysis

gives its most important results in the study

of verb meaning, it is an attractive way of handling semantic relations. It is currently combined with other linguistic procedures used for the investigation of meaning.

Слайд 40References:

Зыкова И.В. Практический курс английской лексикологии. М.: Академия, 2006. – С.-

18-21.

Гинзбург Р.З. Лексикология английского языка. М.: Высшая школа, 1979. – С.- 20-22.

Бабич Н.Г. Лексикология английского языка. Екатеринбург-Москва. 2006. – С.- 61- 62.

Антрушина Г.Б., Афанасьева О.В., Морозова Н.Н. Лексикология английского языка. М.; Дрофа, 2006. С. — 136-142.