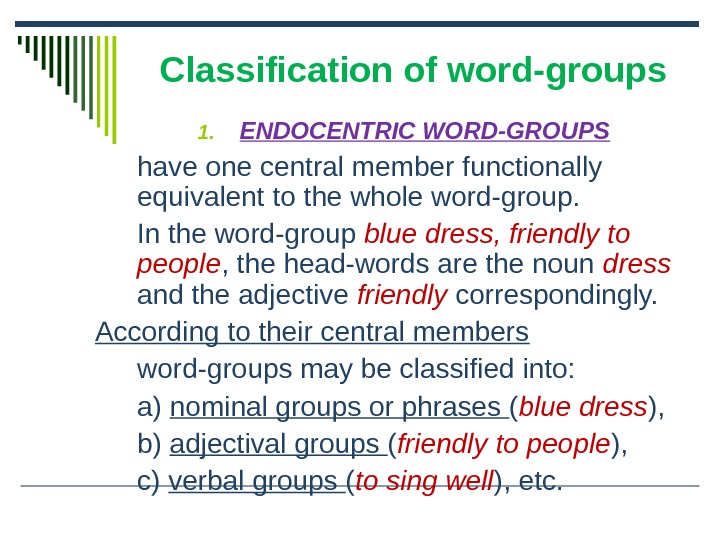

1. All word-groups are analyzed by means of the

criterion of distribution (syntactic use) into two classes:

endocentric and exocentric. It the word-group has the same

linguistic-distribution as one of its members, it is described as

endocentric i.e.

having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole

word-group, e.g. flower- red flower (I see a flower — I see a red

flower). «Flower» is the head word. If the distribution of

the word-group is different from that of either of its members, it is

regarded as exocentric,

i.e. as having no such central member, for instance side

by side, to grow smaller.

II. Word-groups may be classified according to

the criterion of the part of speech meaning

of their head-words into nominal (red

flower), adjectival (kind to people), verbal groups (to speak well).

-

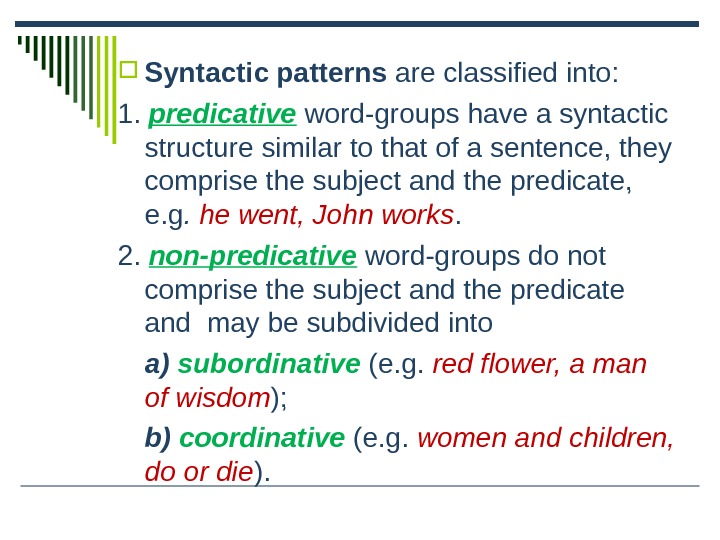

Word-groups may be subdivided according to the

type of syntactic relations between the components

into subordinative and coordinative. Red

flower is a subordinative word-group

because red is

subordinated to flower.

Women and children

is coordinative as there is no subordination here. -

Meaning of word-groups

The lexical meaning of the

word-group may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the

component words. We should point out, however, that the term combined

lexical meaning does not imply that the meaning of the word-group is

a mere additive result of all the lexical meanings of the component

members. The lexical meaning of the word-group predominates over the

lexical meanings of its constituents.

Word-groups possess not only lexical

meaning, but also the meaning conveyed

mainly by the pattern of arrangement of their constituents.

For example, the meanings of the word-groups dog house and house dog

are different though the lexical meanings of the components are

identical. Thus we have to distinguish between the structural meaning

of a word–group and the lexical meanings of its constituents. It

follows that the meaning of the word-group is derived from the

combined lexical meanings of its constituents and is inseparable from

the meaning of the pattern of their arrangement.

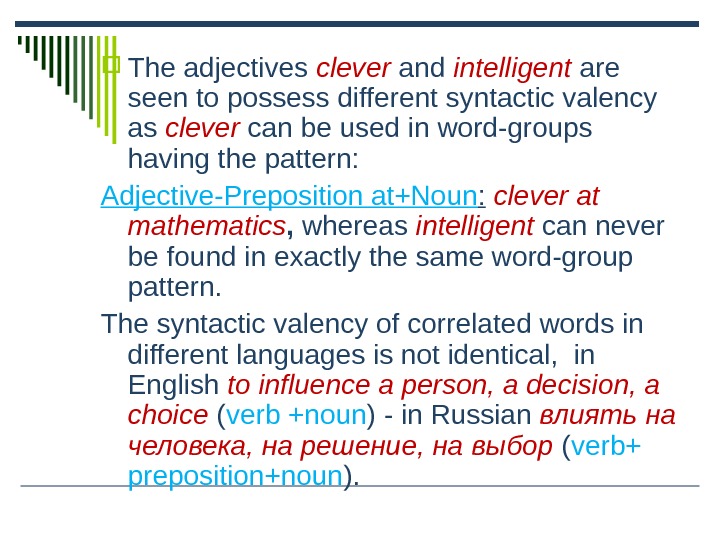

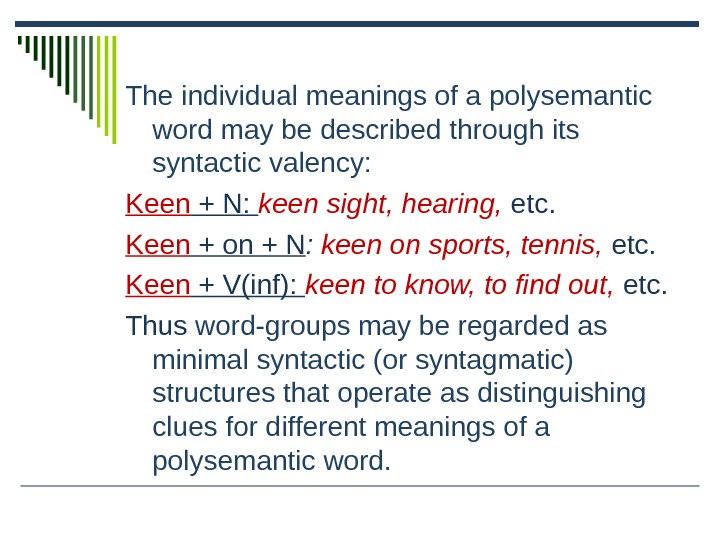

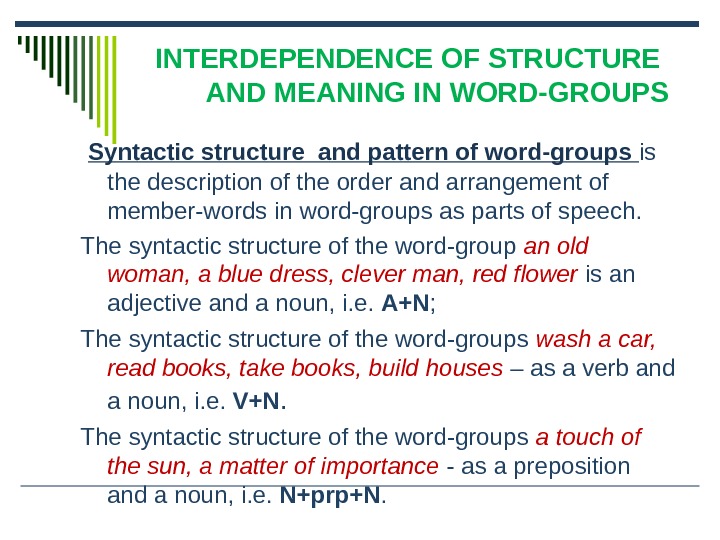

The description of the order and arrangement of

member- words in word — groups as parts of speech is termed syntactic

structure of formula of the word-group. We may, for instance,

describe, the word-group as made up of an Adjective

and a Noun (a clever man, a red flower), a Verb

— a Noun

(to take books), a Noun, a Preposition, a

Noun (a matter of importance). The

syntactic structure (formula) of the nominal groups (clever man) may

be represented as A + N, that of the verbal groups (take books) as V

+ N, etc.

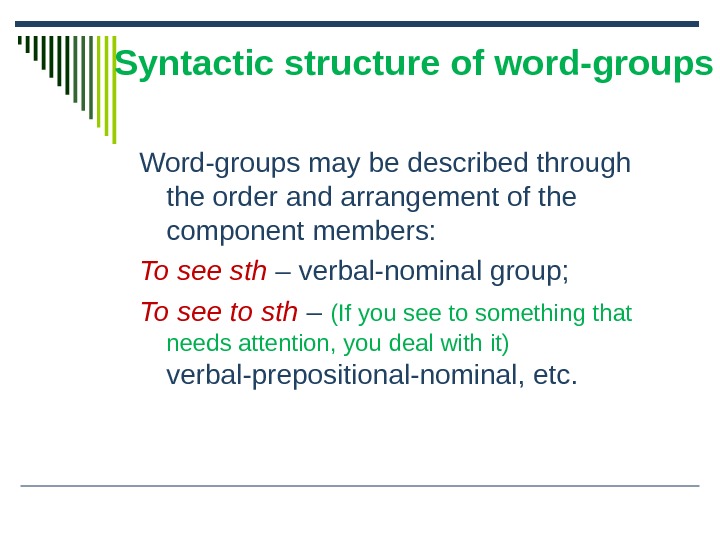

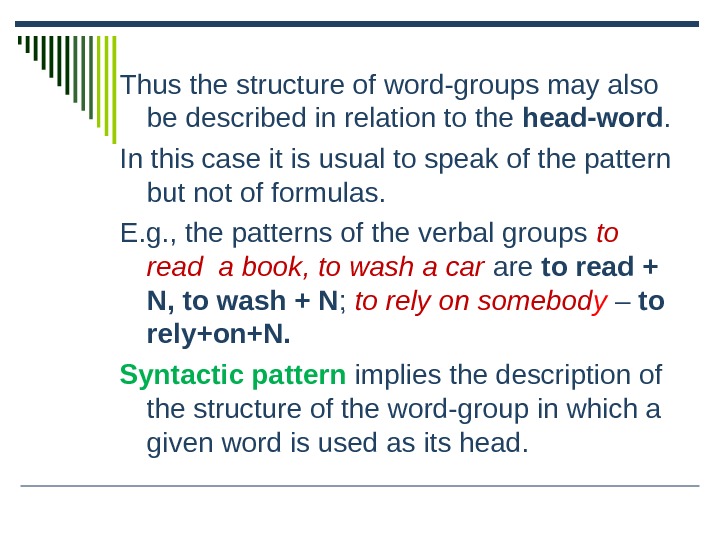

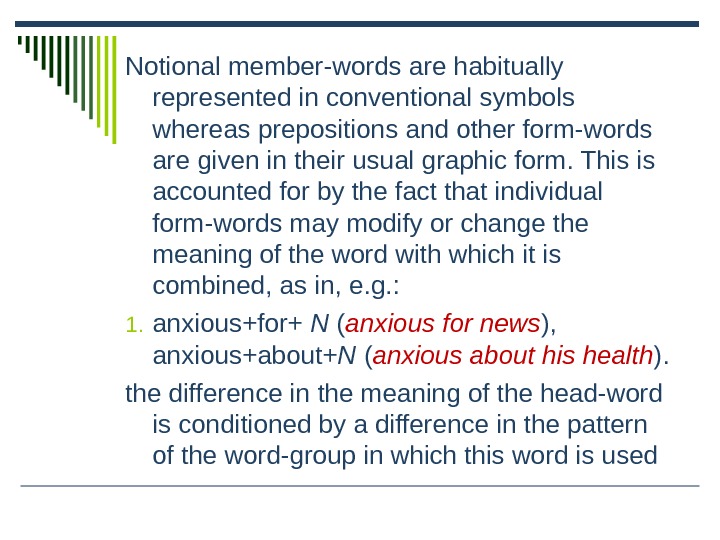

The structure of word-groups may be also described

in relation to the head-word. E.g. the structure of the same verbal

group (to take books) is-represented as to

take + N. In this case it is usual to

speak of the patterns of word-groups.

The term pattern

implies that we are speaking of the structure of the word-group in

which a given word is used as its head.

The difference in the

syntactic structure of word-groups is indicative of a difference in

the meanings of the head-word of word-groups.

Compare: to get a book

(v + n) and to get to know

(v + v (inf.). Structurally simple patterns are as a rule

polysemantic, whereas structurally .complex patterns are

monosemantic. Compare the two patterns: take

+ N (tae tea, coffee, to take books) in

which «take» has different meanings and take

+ to + N (take to sports, take to somebody)

in which take has one meaning.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- Lexicology is the part of linguistics which studies words, their nature(?) and meaning, words’ elements(?), relations between words (semantical relations), word groups and the whole lexicon.

The word «lexicology» derives from the Greek «λεξικόν» (lexicon), neut. of «λεξικός» (lexikos), «of or for words»,[1] from «λέξις» (lexis), «speech», «word»,[2] (in turn from «λέγω» lego «to say», «to speak»[3]) + «-λογία», (-logia), «the study of», a suffix derived from «λόγος» (logos), amongst others meaning «speech, oration, discourse, quote, study, calculation, reason»,[4] it turn also from «λέγω».

The term first appeared in the 1820s, though there were lexicologists in essence before the term was coined.

- General — the general study of words, irrespective of the specific features of any particular language

Special — the description of the vocabulary of a given language

Historical — the study of the evolution of a vocabulary as well as of its elements. This branch discusses the origin of words, their change and development.

Descriptive — deals with the description of the vocabulary of a given language at a given stage of its development.

- English vocabulary as a system

Modern English Lexicology aims at giving a systematic description of the word-stock of Modern English. It treats the following basic problems:

— Basic problems

— Semasiology;

— Word-Structure;

— Word-Formation;

— Etymology of the English Word-Stock;

— Word-Groups and Phraseological Units;

— Variants, dialects of the E. Language;

— English Lexicography.

System is a set of competing possibilities in language, together with the rules for choosing them.

Structuralism recognized that a language is best viewed as a system of elements, with each element being chiefly defined by its place within the system, by the way it is related to other elements.

Language systems:

— speech

— syntactic

— lexical

— morphological

— phonetical

Modern approaches to the problem of study of a language system are characterised by two different levels of study: syntagmatic and paradigmatic.

Paradigmatic relations are the relation between set of linguistic items, which in some sense, constitute choices, so that only one of them may be present at a time in a given position. On the paradigmatic level, the word is studied in its relationships with other words in the vocabulary system.

So, a word may be studied in comparison with other words of similar meaning (e. g. work, n. — labour, n.; to refuse, v. — to reject v. — to decline, v.), of opposite meaning (e. g. busy, adj. — idle, adj.; to accept, v, — to reject, v.), of different stylistic characteristics (e. g. man, n. — chap, n. — bloke, n. — guy, n.).

Consequently, the main problems of paradigmatic studies of vocabulary are:

— synonymy

— hyponymy

— antonymy

— functional styles

Syntagmatic relations

On the syntagmatic level, the semantic structure of the word is analysed in its linear relationships with neighbouring words in connected speech. In other words, the semantic characteristics of the word are observed, described and studied on the basis of its typical contexts, in speech:

— phrases

— collocations

Some collocations are totally predictable, such as spick with span, others are much less so: letter collocates with a wide range of lexemes, such as alphabet and spelling, and (in another sense) box, post, and write.

Collocations differ greatly between languages, and provide a major difficulty in mastering foreign languages. In English, we ‘face’ problems and ‘interpret’ dreams; but in modern Hebrew, we have to ‘stand in front of problems and ‘solve’ dreams.

The more fixed a collocation is, the more we think of it as an ‘idiom’ — a pattern to be learned as a whole, and not as the ‘sum of its parts’.

Combination of paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations in lexical system determines vocabulary as a system.

- One of the earliest and most obvious non-semantic grouping is the alphabetical organization of the word-stock, which is represented in most dictionaries. It is of great practical value in the search for the necessary word, but its theoretical value is almost null, because no other property of the word can be predicted from the letter or letters the word begins with.

Morphological groupings.

On the morphological level words are divided into four groups according to their morphological structure:

1) root or morpheme words (dog, hand);

2) derivatives, which contain no less than two morphemes (dogged (ynpямый), doggedly; handy, handful);

3) compound words consisting of not less than two free morphemes (dog-cheap-«very cheap», dog-days — «hottest part of the year»; handbook, handball)

4) compound derivatives (dog-legged — «crooked or bent like a dog’s hind leg», left-handed).

This grouping is considered to be the basis for lexicology.

Another type of traditional lexicological grouping as known as word-families such as: hand, handy, handicraft, handbag, handball, handful, hand-made,handsome, etc.

A very important type of non-semantic grouping for isolated lexical units is based on a statistical analysis of their frequency. Frequency counts carried out for practical purposes of lexicology, language teaching and shorthand show important correlations between quantative and qualitative characteristics of lexical units, the most frequent words being polysemantic and stylistically neutral. The frequency analysis singles out two classes:

1) notional words;

2) form (or functional) words.

Notional words constitute the bulk of the existing word-stock, according to the recent counts given for the first 1000 most frequently occurring words they make up 93% of the total number.

All notional lexical units are traditionally subdivided into parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs. Nouns numerically make the largest class — about 39% of all notional words; verbs come second — 25% of words; they are followed by adjectives — 17% and adverbs — 12%.

Form or functional words — the remaining 7% of the total vocabulary — are prepositions, articles, conjunctions, which primarily denote various relations between notional words. Their grammatical meaning dominates over their lexical meaning. They make a specific group of about 150 units.

Lexico-grammatical grouping.

By a lexico-grammatical group we understand a class of words which have a common lexico-grammatical meaning, a common paradigm, the same substituting elements and possibly a characteristic set of suffixes rendering the lexico-grammatical meaning.

Lexico-grammatical groups should not be confused with parts of speech. For instance, audience and honesty belong to the same part of speech but to different lexico-grammatical groups because their lexico-grammatical meaning is different.

Common Denominator of Meaning, Semantic Fields.

Words may also be classified according to the concepts underlying their meaning. This classification is closely connected with the theory of semantic fields. By the term «semantic fields» we understand closely knit sectors of vocabulary each characterized by a common concept. The words blue, red, yellow, black, etc. may be described as making up the semantic field of colours, the words mother, father, sister, cousin, etc. — as members of the semantic field of kinship terms, the words joy, happiness, gaiety, enjoyment, etc. as belonging to the field of pleasurable emotions, and so on.

The members of the semantic fields are not synonymous but all of them are joined together by some common semantic component — the concept of colours or the concept of kinship, etc. This semantic component common to all members of the field is sometimes described as the common denominator of meaning. All members of the field are semantically interdependent as each member helps to delimit and determine the meaning of its neighbours and is semantically delimited and determined by them. It follows that the word meaning is to a great extent determined by the place it occupies in its semantic field.

It is argued that we cannot possibly know the exact meaning of the word if we do not know the structure of the semantic field to which the word belongs, the number of the members and the concepts covered by them, etc. The meaning of the word captain, e.g. cannot be properly understood until we know the semantic field in which this term operates — the army, the navy, or the merchant service. It follows that the meaning of the word captain is determined by the place it occupies among the terms of the relevant rank system. In other words we know what captain means only if we know whether his subordinate is called mate or first officer (merchant service), commander (navy) or lieutenant (army).

Semantic dependence of the word on the structure of me field may be also illustrated by comparing members of analogous conceptual fields in different languages. Comparing, e.g. kinship terms in Russian and in English we observe that the meaning of the English term mother-in-law is different from either the Russian тёща or свекровь, as the English term covers the whole area which in Russian is divided between the two words. The same is true of the members of the semantic field of colours (cf. blue — синий, голубой), of human body (cf. hand, arm — рука) and others.

The theory of semantic field is severely criticized by Soviet linguists mainly on philosophical grounds as some of the proponents of the semantic-field theory hold the idealistic view that language is a kind of self-contained entity standing between man and the world of reality (Zwischenwelt). The followers of this theory argue that semantic fields reveal the fact that human experience is analysed and elaborated in a unique way, differing from one language to another. Broadly speaking they assert that people speaking different languages actually have different concepts, as it is through language that we see the real world around us. In short, they deny the primacy of matter forgetting that our concepts are formed not only through linguistic experience, but primarily through our actual contact with the real world. We know what hot means not only because we know the word hot, but also because we burn our fingers when we touch something very hot. A detailed critical analysis of the theory of semantic fields is the subject-matter of general linguists. Here we are concerned with the theory only as a means of semantic classification of vocabulary items.

Two more points should be discussed in this connection. Firstly, semantic groups may be very extensive and may cover big conceptual areas, e.g. man-universe, etc. There may be, however, comparatively small lexical groups of words linked by a common denominator of meaning. The words bread, cheese, milk, meat, etc. make up the semantic field with the concept of food as the common denominator of meaning. Such smaller lexical groups seem to play a very important role in determining individual meanings of polysemantic words in lexical contexts. Analysing polysemantic verbs we see that the verb take, e.g. in combination with the lexical group denoting means of transportation is synonymous with the verb go (take the tram, the bus, etc.). When combined with members of another lexical group possessing another semantic denominator, the same verb is synonymous with to drink (to take tea, coffee, etc.). Such word-groups are often used not only in scientific lexicological analysis, but also in practical class-room teaching. In a number of textbooks we find words with some common denominator of meaning listed under the headings Flower, Fruit, Domestic Animals, and so on.

In other words lexical or semantic field is the organization of related words and expressions into a system which shows their relationship to one another.

For example, kinship terms such as father, mother, sister, brother, uncle, aunt belong to a lexical field whose relevant features include generation, sex, membership of the father’s or mother’s side of the family, etc.

The absence of a word in a particular place in a lexical field of a language is called a lexical gap.

For example, in English there is no singular noun that covers both cow and bull as hoarse covers stallion and mare.

Common Contextual Associations. Thematic Groups.

Another type of classification almost universally used in practical class-room teaching is known as thematic grouping. Classification of vocabulary items into thematic groups is based on the co-occurrence of words in certain repeatedly used contexts.

In linguistic contexts co-occurrence may be observed on different levels. On the level of word-groups the word question, e.g., is often found in collocation with the verbs raise, put forward, discuss, etc., with the adjectives urgent, vital, disputable and so on. The verb accept occurs in numerous contexts together with the nouns proposal, invitation, plan and others.

As a rule, thematic groups deal with contexts on the level of the sentence (or utterance). Words in thematic groups are joined together by common contextual associations within the framework of the sentence and reflect the interlinking words, e.g. tree-grow-green; journey-train-taxi-bags-ticket or sun-shine-brightly-blue-sky, is due to the regular co-occurrence of these words in similar sentences. Unlike members of synonymic sets or semantic fields, words making up a thematic group belong to different parts of speech and do not possess any common denominator of meaning.

Contextual associations formed by the speaker of a language are usually conditioned by the context of situation which necessitates the use of certain words. When watching a play, e.g., we naturally speak of the actors who act the main parts, of good (or bad) staging of the play, of the wonderful scenery and so on. When we go shopping it is usual to speak of the prices, of the goods we buy, of the shops, etc. (In practical language learning thematic groups are often listed under various headings, e.g. At the Theatre, At School, Shopping, and are often found in text-books and courses of conversational English).

Thematic and ideographic organization of a vocabulary.

It is a further subdivision within the lexico-grammatical grouping. The basis of grouping is not only linguistic but also extra-linguistic. The words are associated because the things they name occur together and are closely connected in reality, e.g., terms of kinship. Names of parts of the human body, colour terms, etc.

The ideographic groupings are independent of classification into parts of speech, as grammatical meaning is not taken into consideration. Words and expressions are here classed not according to their lexico-grammatical meaning but strictly according to their signification, i.e. to their system of logical notions. These subgroups may compare nouns, verbs adjectives and adverbs together, provided they refer to the same notion. Under alphabetical order the words which in the human mind go close together (father, brother, uncle, etc.) are placed in various parts of a dictionary. So, some lexicographers place such groups of lexical units in the company they usually keep in every day life, in our minds. These dictionaries are called ideographical or ideological.

Synonymic grouping is a special case of lexico-grammatical grouping based on semantic proximity of words belonging to the same part of speech. Taking up similarity of meaning and contrasts of phonetic shape we observe that every language in its vocabulary has a variety of words kindred (родственный) or similar in meaning but distinct in morphemic composition, phonetic shape and usage. These words express the most delicate shades of thought, feelings and are explained in the dictionaries of synonyms.

Antonyms have been traditionally defined as words of opposite meaning. Their distinction from synonyms is semantic polarity. The English language is rich in synonyms and antonyms, their study reveals the systematic character of the English vocabulary.

Special terminology.

Sharply defined extensive semantic fields are found in terminological systems. Terminology constitutes the greatest part of every language vocabulary. A term is a word or word-group used to name a notion characteristic of some special field of knowledge, e.g., linguistics, cybernetics, industry, culture, informatics. Almost every system of terms is nowadays fixed and analyzed in numerous special dictionaries of the English language. ?

Hyponymy (включение).

Another type of paradigmatic relation is hyponymy. The notion of hyponymy is traditional enough; it has been long recognized as one of the main-principles in the organization of the vocabulary off all languages. For instance, animal is a generic term as compared to the specific names: wolf, dog, mouse. Dog, in its tern, may serve as a generic term for different breeds such as bull-dog, collie, poodle.

In other words, this type of relationship means the «inclusion» of a more specific term in a more general term, which has been established by some scientists in terms of logic of classes*. For example, the meaning of tulips is said to be included in the meaning of «flower», and so on.

So, the word-stock is not only a sum total of all the words of a language, but a very complicated set of various relationships between different groupings, layers, between the vocabulary as a whole and isolated individual lexical units.

- The importance of English lexicology is based not on the size of its vocabulary, however big it is, but on the fact that at present it is the world’s most widely used language. One of the most fundamental works on the English language of the present — «A Grammar of Contemporary English” by R. Quirk, S. Greenbaum, G. Leech and J. Svartvik (1978) — gives the following data: it is spoken as a native language by nearly three hundred million people in Britain, the United States, Ireland, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and some other countries. The knowledge of English is widely spread geographically — it is in fact used in all continents. It is also spoken in many countries as a second language and used in official and business activities there. This is the case in India, Pakistan and many other former British colonies. English is also one of the working languages of the United Nations and the universal language of international aviation. More than a half world’s scientific literature is published in English and 60% of the world’s radio broadcasts are in English. For all these reasons it is widely studied all over the world as a foreign language. The theoretical value of lexicology becomes obvious if we realise that it forms the study of one of the three main aspects of language, i.e. its vocabulary, the other two being its grammar and sound system. The theory of meaning was originally developed within the limits of philosophical science. The relationship between the name and the thing named has in the course of history constituted one of the key questions in gnostic theories and therefore in the struggle of materialistic and idealistic trends. The idealistic point of view assumes that the earlier forms of words disclose their real correct meaning, and that originally language was created by some superior reason so that later changes of any kind are looked upon as distortions and corruption. The materialistic approach considers the origin, development and current use of words as depending upon the needs of social communication. The dialectics of its growth is determined by its interaction with the development of human practice and mind. In the light of V. I. Lenin’s theory of reflection we know that the meanings of words reflect objective reality. Words serve as names for things, actions, qualities, etc. and by their modification become better adapted to the needs of the speakers. This proves the fallacy of one of the characteristic trends in modern idealistic linguistics, the so-called Sapir-Whorf thesis according to which the linguistic system of one’s native language not only expresses one’s thoughts but also determines them. This view is incorrect, because our mind reflects the surrounding world not only through language but also directly. Lexicology came into being to meet the demands of many different branches of applied linguistics, namely of lexicography, standardisation of terminology, information retrieval, literary criticism and especially of foreign language teaching. Its importance in training a would-be teacher of languages is of a quite special character and cannot be overestimated as it helps to stimulate a systematic approach to the facts of vocabulary and an organised comparison of the foreign and native language. It is particularly useful in building up the learner’s vocabulary by an effective selection, grouping and analysis of new words. New words are better remembered if they are given not at random but organised in thematic groups, word-families, synonymic series, etc. A good knowledge of the system of word-formation furnishes a tool helping the student to guess and retain in his memory the meaning of new words on the basis of their motivation and by comparing and contrasting them with the previously learned elements and patterns. The knowledge, for instance, of the meaning of negative, reversative and pejorative prefixes and patterns of derivation may be helpful in understanding new words. For example such words as immovable a, deforestation n and miscalculate v will be readily understood as ‘that cannot be moved’, ‘clearing land from forests’ and ‘to calculate wrongly’. By drawing his pupils’ attention to the combining characteristics of words the teacher will prevent many mistakes.1 It will be word-groups falling into patterns, instead of lists of unrelated items, that will be presented in the classroom. A working knowledge and understanding of functional styles and stylistic synonyms is indispensable when literary texts are used as a basis for acquiring oral skills, for analytical reading, discussing fiction and translation. Lexicology not only gives a systematic description of the present make-up of the vocabulary, but also helps students to master the literary standards of word usage. The correct use of words is an important counterpart of expressive and effective speech. An exact knowledge of the vocabulary system is also necessary in connection with technical teaching means. Lexicology plays a prominent part in the general linguistic training of every philologist by summing up the knowledge acquired during all his years at the foreign language faculty. It also imparts the necessary skills of using different kinds of dictionaries and reference books, and prepares for future independent work on increasing and improving one’s vocabulary.

- The treatment of words in lexicology cannot be divorced from the study of all the other elements in the language system to which words belong. It should be always borne in mind that in reality, in the actual process of communication, all these elements are interdependent and stand in definite relations to one another. We separate them for convenience of study, and yet to separate them for analysis is pointless, unless we are afterwards able to put them back together to achieve a synthesis and see their interdependence and development in the language system as a whole. The word, as it has already been stated, is studied in several branches of linguistics and not in lexicology only, and the latter, in its turn, is closely connected with general linguistics, the history of the language, phonetics, stylistics, grammar and such new branches of our science as sociolinguistics, paralinguistics, pragmalinguistics and some others.1 The importance of the connection between lexicology and phonetics stands explained if we remember that a word is an association of a given group of sounds with a given meaning, so that top is one word, and tip is another. Phonemes have no meaning of their own but they serve to distinguish between meanings. Their function is building up morphemes, and it is on the level of morphemes that the form-meaning unity is introduced into language. We may say therefore that phonemes participate in signification. Word-unity is conditioned by a number of phonological features. Phonemes follow each other in a fixed sequence so that [pit] is different from [tip]. The importance of the phonemic make-up may be revealed by the substitution test which isolates the central phoneme of hope by setting it against hop, hoop, heap or hip. An accidental or jocular transposition of the initial sounds of two or more words, the so-called spoonerisms illustrate the same point. Cf. our queer old dean for our dear old queen, sin twister for twin sister, May I sew you to a sheet? for May I show you to a seat?, a half-warmed fish for a half-formed wish, etc.1 Discrimination between the words may be based upon stress: the word ‘import is recognised as a noun and distinguished from the verb im’port due to the position of stress. Stress also distinguishes compounds from otherwise homonymous word-groups: ‘blackbird : : ‘black ‘bird. Each language also possesses certain phonological features marking word-limits. Historical phonetics and historical phonology can be of great use in the diachronic study of synonyms, homonyms and polysemy. When sound changes loosen the ties between members of the same word-family, this is an important factor in facilitating semantic changes. The words whole, heal, hail, for instance, are etymologically related.2 The word whole originally meant ‘unharmed’, ;unwounded’. The early verb whole meant 4to make whole’, hence ‘heal’. Its sense of ‘healthy’ led to its use as a salutation, as in hail! Having in the course of historical development lost their phonetic similarity, these words cannot now exercise any restrictive influence upon one another’s semantic development. Thus, hail occurs now in the meaning of ‘call’, even with the purpose to stop and arrest (used by sentinels). Meaning in its turn is indispensable to phonemic analysis because to establish the phonemic difference between [ou] and [o] it is sufficient to know that [houp] means something different from [hop]. All these considerations are not meant to be in any way exhaustive, they can only give a general idea of the possible interdependence of the two branches of linguistics. Stylistics, although from a different angle, studies many problems treated in lexicology. These are the problems of meaning, connotations, synonymy, functional differentiation of vocabulary according to the sphere of communication and some other issues. For a reader without some awareness of the connotations and history of words, the images hidden in their root and their stylistic properties, a substantial part of the meaning of a literary text, whether prosaic or poetic, may be lost. Thus, for instance, the mood of despair in O. Wilde’s poem «Taedium Vitae” (Weariness of Life) is felt due to an accumulation of epithets expressed by words with negative, derogatory connotations, such as: desperate, paltry, gaudy, base, lackeyed, slanderous, lowliest, meanest. An awareness of all the characteristic features of words is not only rewarded because one can feel the effect of hidden connotations and imagery, but because without it one cannot grasp the whole essence of the message the poem has to convey. The difference and interconnection between grammar and lexicology is one of the important controversial issues in linguistics and as it is basic to the problems under discussion in this book, it is necessary to dwell upon it a little more than has been done for phonetics and stylistics. A close connection between lexicology and grammar is conditioned by the manifold and inseverable ties between the objects of their study. Even isolated words as presented in a dictionary bear a definite relation to the grammatical system of the language because they belong to some part of speech and conform to some lexico-grammatical characteristics of the word class to which they belong. Words seldom occur in isolation. They are arranged in certain patterns conveying the relations between the things for which they stand, therefore alongside with their lexical meaning they possess some grammatical meaning. Сf. head of the committee and to head a committee. The two kinds of meaning are often interdependent. That is to say, certain grammatical functions and meanings are possible only for the words whose lexical meaning makes them fit for these functions, and, on the other hand, some lexical meanings in some words occur only in definite grammatical functions and forms and in definite grammatical patterns. For example, the functions of a link verb with a predicative expressed by an adjective cannot be fulfilled by every intransitive verb but are often taken up by verbs of motion: come true, fall ill, go wrong, turn red, run dry and other similar combinations all render the meaning of ‘become sth’. The function is of long standing in English and can be illustrated by a line from A. Pope who, protesting against blank verse, wrote: It is not poetry, but prose run mad.1 On the other hand the grammatical form and function of the word affect its lexical meaning. A well-known example is the same verb go when in the continuous tenses, followed by to and an infinitive (except go and come), it serves to express an action in the near and immediate future, or an intention of future action: You’re not going to sit there saying nothing all the evening, both of you, are you? (Simpson) Participle II of the same verb following the link verb be denotes absence: The house is gone. In subordinate clauses after as the verb go implies comparison with the average: … how a novel that has now had a fairly long life, as novels go, has come to be written (Maugham). The subject of the verb go in this construction is as a rule an inanimate noun. The adjective hard followed by the infinitive of any verb means ‘difficult’: One of the hardest things to remember is that a man’s merit in one sphere is no guarantee of his merit in another. Lexical meanings in the above cases are said to be grammatically conditioned, and their indicating context is called syntactic or mixed. The point has attracted the attention of many authors.1 The number of words in each language being very great, any lexical meaning has a much lower probability of occurrence than grammatical meanings and therefore carries the greatest amount of information in any discourse determining what the sentence is about. W. Chafe, whose influence in the present-day semantic syntax is quite considerable, points out the many constraints which limit the co-occurrence of words. He considers the verb as of paramount importance in sentence semantic structure, and argues that it is the verb that dictates the presence and character of the noun as its subject or object. Thus, the verbs frighten, amuse and awaken can have only animate nouns as their objects. The constraint is even narrower if we take the verbs say, talk or think for which only animate human subjects are possible. It is obvious that not all animate nouns are human. This view is, however, if not mistaken, at least one-sided, because the opposite is also true: it may happen that the same verb changes its meaning, when used with personal (human) names and with names of objects. Compare: The new girl gave him a strange smile (she smiled at him) and The new teeth gave him a strange smile. These are by no means the only relations of vocabulary and grammar. We shall not attempt to enumerate all the possible problems. Let us turn now to another point of interest, namely the survival of two grammatically equivalent forms of the same word when they help to distinguish between its lexical meanings. Some nouns, for instance, have two separate plurals, one keeping the etymological plural form, and the other with the usual English ending -s. For example, the form brothers is used to express the family relationship, whereas the old form brethren survives in ecclesiastical usage or serves to indicate the members of some club or society; the scientific plural of index, is usually indices, in more general senses the plural is indexes. The plural of genius meaning a person of exceptional intellect is geniuses, genius in the sense of evil or good spirit has the plural form genii. It may also happen that a form that originally expressed grammatical meaning, for example, the plural of nouns, becomes a basis for a new grammatically conditioned lexical meaning. In this new meaning it is isolated from the paradigm, so that a new word comes into being. Arms, the plural of the noun arm, for instance, has come to mean ‘weapon’. E.g. to take arms against a sea of troubles (Shakespeare). The grammatical form is lexicalised; the new word shows itself capable of further development, a new grammatically conditioned meaning appears, namely, with the verb in the singular arms metonymically denotes the military profession. The abstract noun authority becomes a collective in the term authorities and denotes ‘a group of persons having the right to control and govern’. Compare also colours, customs, looks, manners, pictures, works which are the best known examples of this isolation, or, as it is also called, lexicalisation of a grammatical form. In all these words the suffix -s signals a new word with a new meaning. It is also worthy of note that grammar and vocabulary make use of the same technique, i.e. the formal distinctive features of some derivational oppositions between different words are the same as those of oppositions contrasting different grammatical forms (in affixation, juxtaposition of stems and sound interchange). Compare, for example, the oppositions occurring in the lexical system, such as work :: worker, power :: will-power, food :: feed with grammatical oppositions: work (Inf.) :: worked (Past Ind.), pour (Inf.) :: will pour (Put. Ind.), feed (Inf.) :: fed (Past Ind.). Not only are the methods and patterns similar, but the very morphemes are often homonymous. For example, alongside the derivational suffixes -en, one of which occurs in adjectives (wooden), and the other in verbs (strengthen), there are two functional suffixes, one for Participle II (written), the other for the archaic plural form (oxen). Furthermore, one and the same word may in some of its meanings function as a notional word, while in others it may be a form word, i.e. it may serve to indicate the relationships and functions of other words. Compare, for instance, the notional and the auxiliary do in the following: What you do’s nothing to do with me, it doesn’t interest me. Last but not least all grammatical meanings have a lexical counterpart that expresses the same concept. The concept of futurity may be lexically expressed in the words future, tomorrow, by and by, time to come, hereafter or grammatically in the verbal forms shall come and will come. Also plurality may be described by plural forms of various words: houses, boys, books or lexically by the words: crowd, party, company, group, set, etc. The ties between lexicology and grammar are particularly strong in the sphere of word-formation which before lexicology became a separate branch of linguistics had even been considered as part of grammar. The characteristic features of English word-building, the morphological structure of the English word are dependent upon the peculiarity of the English grammatical system. The analytical character of the language is largely responsible for the wide spread of conversion1 and for the remarkable flexibility of the vocabulary manifest in the ease with which many nonce-words2 are formed on the spur of the moment. This brief account of the interdependence between the two important parts of linguistics must suffice for the present. In future we shall have to return to the problem and treat some parts of it more extensively.

- Размер: 211 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 39

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27607

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Language levels. The grammatical system of the English language, like of other Indo-European languages, is very complicated. It consists of smaller subdivisions, which are called systems too. In grammar they are morphological and syntactic ones.

In syntax we discriminate between the systems of simple and composite sentences, etc. Prof. V. V. Plotkin suggests the terms ‘morosystem’ implying the grammatical system of the language as a whole and ‘subsystem’ and ‘microsystem’ with reference to minor system.

Thus, the systemic character of grammar is beyond doubt. The phonological structure of language is also systemic. The question of the systemic character of vocabulary (word-stock) remains open. But of all lingual aspects grammar is, no doubt, most systemic since it is responsible for the very organization of the informative content of utterance.

style=»text-align: justify;»>Language in general and grammar in particular are materialized in structure. Language structure is represented by a level stratification of its units. This structure is of hierarchical character. Graphically the level stratification of language can be depicted by following table (scheme):

|

Supra-proposemic |

Text, texteme, dicteme |

The highest communicative unit |

|

Promosemic (the level of major syntax) |

Proposeme (sentence) |

Communicative unit |

|

Phrasemic (the level of minor syntax) |

Phraseme (word-group) |

Polynominative unit |

|

Word level (lexemic) |

align=»left»>Lexeme (word) |

Monominative unit |

|

Morphological (morphemic) |

Morpheme |

The smallest meaning full unit |

|

Phonological (phonemic) |

Phoneme |

Distinctive unit |

|

Level |

Language unit |

The nature of the unrepresenting level |

Units of language. Units of language are divided into meaningless and meaningful. Examples of the first kind: phonemes, syllable Meaningful are morpheme, word and others. The latter are called — language signs. They have both planes: that of content and that of expression. They are signemes.

As to the way of expressing lingual units are divided into segmental and supra-segmental. Segmental units consists of phonemes and form phonetic strings of various status (morphemes, syllables). Supra-segmental units do not exist by themselves, they are realized together with segmental units and express different modificational meanings which are reflected on the strings of segmental units. Supra-segmental units are intonation contours, streets, pauses and the like.

Segmental units form a hierarchy of levels. The lowest level is phonemic. It is formed by phonemes, which are not language signs, because they are purely differential (distinctive) units.Units of all the higher levels are meaningful. They are language signs (signemes) .

There is table opposite the chair.

Сейчас вы читаете: Units of Language. Language Levels