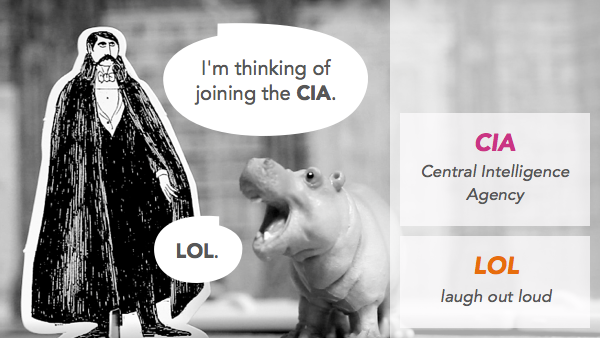

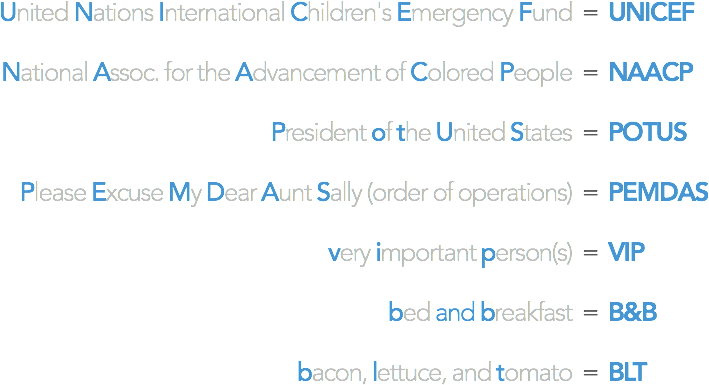

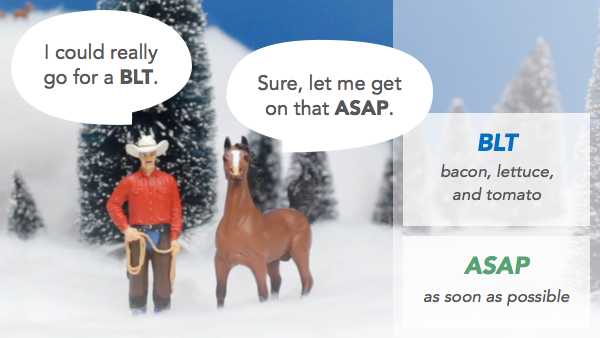

Acronyms are abbreviations spoken or used as if they are words in themselves. Often they are pronounced as words, like the three above; otherwise they are pronounced as individual letters, like CIA or FBI.

an abbreviation formed of the first letters of words in a phrase or name.

TBA- To Be Announced

CIA- Central Intelligence Agency

MST-Mountain Standard Time

USA-United States of America

WWW-World Wide Web

MPH-Miles Per Hour

WFH-Work From Home

NASA-National Aeronautics & Space Agency

I’m not sure if you wanted specific examples of specific things so here’s just some random ones I could think of off the top of my head.

An acronym is a word, name or set of letters created as an abbreviation of a longer phrase or sentence. Usually connectives or words such as ‘and’ or ‘of’ are not included in the abbreviation.

Examples:

- NASA = National Aeronautics (and) Space Administration

- DIY = Do It Yourself

- DNA = Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- Sim (card) = Subscriber Identity Module

Hope this helps!

Acronyms are a combination of letters that stand for something. For instance, BIOS is an computer acronym, standing for Basic Input/output System. More examples can include

- NATO: North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- HTTP: Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol

- GIF: Graphics Interchange Format

- LCD: Liquid Crystal Display

I think you get the point here. Acronyms are simply a group of letters in which the letters stand for a word.

Hope this helps!

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,

coldly,

etc.

Borrowed

affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary.

We can recognize words of Latin and French origin by certain suffixes

or

prefixes;

e. g. Latin

affixes:

-ion,

-tion, -ate,

-ute

,

-ct,

-d(e), dis-, -able, -ate,

-ant,

—

ent,

-or, -al, -ar in

such words as opinion,

union, relation, revolution, appreciate,

congratulate,

attribute, contribute, , act, collect, applaud, divide, disable,

disagree,

detestable,

curable, accurate, desperate, arrogant, constant, absent, convenient,

major,

minor, cordial, familiar;

French

affixes –ance,

—ewe,

-ment, -age, -ess, -ous,

en-

in

such words as arrogance,

intelligence, appointment, development, courage,

marriage,

tigress, actress, curious, dangerous, enable, enslaver.

Affixation

includes a) prefixation

–

derivation of words by adding a prefix to

full

words and b) suffixation

–

derivation of words by adding suffixes to bound

stems.

Prefixes

and suffixes have their own valency, that is they may be added not to

any

stem at random, but only to a particular type of stems:

84

Prefix

un-

is

prefixed to adjectives (as: unequal,

unhealthy), or

to adjectives

derived

from verb stems and the suffix -able

(as:

unachievable,

unadvisable), or

to

participial

adjectives (as: unbecoming,

unending, unstressed, unbound); the

suffix —

er

is

added to verbal stems (as: worker,

singer, or

cutter,

lighter), and

to substantive

stems

(as: glover,

needler); the

suffix -able

is

usually tacked on to verb stems (as:

eatable,

acceptable); the

suffix -ity

in

its turn is usually added to adjective stems

with

a passive meaning (as: saleability,

workability), but

the suffix —ness

is

tacked on

to

other adjectives, having the suffix -able

(as:

agreeableness.

profitableness).

Prefixes

and suffixes are semantically distinctive, they have their own

meaning,

while the root morpheme forms the semantic centre of a word. Affixes

play

a

dependent role in the meaning of the word. Suffixes have a

grammatical meaning,

they

indicate or derive a certain part of speech, hence we distinguish:

noun-forming

suffixes,

adjective-forming suffixes, verb-forming suffixes and adverb-forming

suffixes.

Prefixes change or concretize the meaning of the word, as: to

overdo (to

do

too

much),

to underdo (to

do less than one can or is proper),

to outdo (to

do more or

better

than),

to undo (to

unfasten, loosen, destroy the result, ruin),

to misdo (to

do

wrongly

or unproperly).

A

suffix indicates to what semantic group the word belongs. The suffix

-er

shows

that the word is a noun bearing the meaning of a doer of an action,

and the

action

is denoted by the root morpheme or morphemes, as: writer,

sleeper, dancer,

wood-pecker,

bomb-thrower, the

suffix -ion/-tion,

indicates

that it is a noun

signifying

an action or the result of an action, as: translation

‘a

rendering from one

language

into another’ (an

act, process) and

translation

‘the

product of such

rendering’;

nouns with the suffix -ism

signify

a system, doctrine, theory, adherence to

a

system, as: communism,

realism; coinages

from the stem of proper names are

common,.

as Darwinism.

Affixes

can also be classified into productive

and

non-productive

types.

By

productive

affixes we

mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in a

particular

period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes

is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e.

words

coined

and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually

formed on the

level

of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive

patterns in

word-building.

When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable

thriller, we

will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in

dictionaries,

for it is a nonce-word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English

and

is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming

borrowed suffix –

able

and

the native prefix un-,

e.g.: Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish,

dyspeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock.(From

Right-Ho, Jeeves by P.G.

Wodehouse)

The

adjectives thinnish

and

baldish

bring

to mind dozens of other adjectives

made

with the same suffix: oldish,

youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish,

yellowish,

etc. But

dyspeptic-lookingish

is

the author’s creation aimed at a humorous

effect,

and, at the same time, providing beyond doubt that the suffix –ish

is

a live and

active

one.

85

The

same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: “I

don’t like

Sunday

evenings: I feel so Mondayish”. (Mondayish is

certainly a nonce-word.)

One

should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency

of

occurrence

(use). There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which,

nevertheless,

are no longer used in word-derivation (e.g. the adjective-forming

native

suffixes

–ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin –ant,

-ent, -al which

are

quite frequent).

Some

Productive Affixes

Some

Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming

suffixes

-th,

-hood

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—ly,

-some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming

suffix -en

Compound

words are

words derived from two or more stems. It is a very old

word-formation

type and goes back to Old English. In Modern English compounds

are

coined by joining one stem to another by mere juxtaposition, as

raincoat,

keyhole,

pickpocket,

red-hot, writing-table. Each

component of a compound coincides

with

the word. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives.

Compound

verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion

(as,

to

weekend) and

of back-formation (as, to

stagemanage).

From

the point of view of word-structure compounds consist of free stems

and

may

be of different structure: noun stems + noun stem (raincoat);

adjective

stem +

noun

stem (bluebell);

adjective

stem + adjective stem (dark-blue);

gerundial

stem +

noun

stem (writing-table);

verb

stem + post-positive stem (make-up);

adverb

stem +

adjective

stem (out-right);

two

noun stems connected by a preposition (man-of-war)

and

others. There are compounds that have a connecting vowel (as,

speedometer,

handicraft),

but

it is not characteristic of English compounds.

Compounds

may be idiomatic

and

non-idiomatic.

In idiomatic compounds the

meaning

of each component is either lost or weakened, as buttercup

(лютик),

chatter-box

(болтун).

These

are entirely

demotivated compounds. There

are also motivated

compounds,

as lifeboat

(спасательная

лодка). In non-idiomatic compounds the

Noun-forming

suffixes

—er,

-ing,

—ness,

-ism (materialism),

-ist

(impressionist),

-ance

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—y,

-ish, -ed (learned),

—able,

—less

Adverb-forming

suffix

—ly

Verb-forming

suffixes

—ize/-ise

(realize),

—ate

Prefixes

un-

(unhappy),re-

(reconstruct),

dis-

(disappoint)

86

meaning

of each component is retained, as apple-tree,

bedroom, sunlight. There

are

also

many border-line cases.

The

components of compounds may have different semantic relations; from

this

point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric

and

exocentric

compounds.

In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found

within

the compound and the first element determines the other, as

film-star,

bedroom,

writing-table.

In

exocentric compounds there is no semantic centre, as

scarecrow.

In

Modern English, however, linguists find it difficult to give criteria

for

compound

nouns; it is still a question of hot dispute. The following criteria

may be

offered.

A compound noun is characterized by a) one word or hyphenated

spelling, b)

one

stress, and by c) semantic integrity. These are the so-called

“classical

compounds”.

It

is possible that a compound has only two of these criteria, for

instance, the

compound

words headache,

railway have

one stress and hyphenated or one-word

spelling,

but do not present a semantic unity, whereas the compounds

motor-bike,

clasp-knife

have

hyphenated spelling and idiomatic meaning, but two even stresses

(‘motor-‘bike,

‘clasp-‘knife).

The word apple-tree

is

also a compound; it is spelt either

as

one word or is hyphenated, has one stress (‘apple-tree),

but it is not idiomatic. The

difficulty

of defining a compound lies in spelling which might be misleading, as

there

are

no hard and fast rules of spelling the compounds: three ways of

spelling are

possible:

(‘dockyard,

‘dock yard and

dock-yard).

The

same holds true for the stress

that

may differ from one reference-book to another.

Since

compounds may have two stresses and the stems may be written

separately,

it is difficult to draw the line between compounds proper and nominal

word-combinations

or syntactical combinations. In a combination of words each

element

is stressed and written separately. Compare the attributive

combination

‘black

‘board, a

board which is black (each element has its own meaning; the first

element

modifies the second) and the compound ‘blackboard’,

a

board or a sheet of

slate

used in schools for teaching purposes (the word has one stress and

presents a

semantic

unit). But it is not always easy as that to draw a distinction, as

there are

word-combinations

that may present a semantic unity, take for instance: green

room

(a

room in a theatre for actors and actresses).

Compound

derivatives are

words, usually nouns and adjectives, consisting of

a

compound stem and a suffix, the commonest type being such nouns as:

firstnighter,

type-writer,

bed-sitter, week-ender, house-keeping, well-wisher, threewheeler,

old-timer,

and

the adjectives: blue-eyed,

blond-haired, four-storied, mildhearted,

high-heeled.

The

structure of these nouns is the following: a compound stem

+

the suffix -er,

or

the suffix -ing.

Adjectives

have the structure: a compound stem, containing an adjective (noun,

numeral)

stem and a noun stem + the suffix -ed.

In

Modern English it is an extremely

productive

type of adjectives, e.g.: big-eyed,

long-legged, golden-haired.

In

Modern English it is common practice to distinguish also

semi-suffixes, that

is

word-formative elements that correspond to full words as to their

lexical meaning

and

spelling, as -man,

-proof, -like: seaman, railroadman, waterproof, kiss-proof,

ladylike,

businesslike. The

pronunciation may be the same (cp. proof

[pru:f]

and

87

waterproof

[‘wL:tq

pru:f],

or differ, as is the case with the morpheme -man

(cp.

man

[mxn]

and seaman

[‘si:mqn].

The

commonest is the semi-suffix -man

which

has a more general meaning —

‘a

person of trade or profession or carrying on some work’, as: airman,

radioman,

torpedoman,

postman, cameramen, chairman and

others. Many of them have

synonyms

of a different word structure, as seaman

— sailor, airman — flyer,

workman

— worker; if

not a man but a woman

of

the trade or profession, or a person

carrying

on some work is denoted by the word, the second element is woman,

as

chairwoman,

air-craftwoman, congresswoman, workwoman, airwoman.

Conversion

is

a very productive way of forming new words in English, chiefly

verbs

and not so often — nouns. This type of word formation presents one

of the

characteristic

features of Modern English. By conversion we mean derivation of a

new

word from the stem of a different part of speech without the addition

of any

formatives.

As a result the two words are homonymous, having the same

morphological

structure and belonging to different parts of speech.

Verbs

may be derived from the stem of almost any part of speech, but the

commonest

is the derivation from noun stems as: (a)

tube — (to) tube; (a) doctor —

(to)

doctor, (a) face—(to) face; (a) waltz—(to) waltz; (a) star—(to)

star; from

compound

noun stems as: (a)

buttonhole — (to) buttonhole; week-end — (to) weekend.

Derivations

from the stems of other parts of speech are less common: wrong—

(to)

wrong; up — (to) up; down — (to) down; encore — (to) encore.

Nouns

are

usually

derived from verb stems and may be instanced by such nouns as: (to)

make—

a

make; (to) cut—(a) cut; to bite — (a) bite, (to) drive — (a)

drive; to smoke — (a)

smoke;

(to) walk — (a) walk. Such

formations frequently make part of verb — noun

combinations

as: to

take a walk, to have a smoke, to have a drink, to take a drive, to

take

a bite, to give a smile and

others.

Nouns

may be also derived from verb-postpositive phrases. Such formations

are

very common in Modern English, as for instance: (to)

make up — (a) make-up;

(to)

call up — (a) call-up; (to) pull over — (a) pullover.

New

formations by conversion from simple or root stems are quite usual;

derivatives

from suffixed stems are rare. No verbal derivation from prefixed

stems is

found.

The

derived word and the deriving word are connected semantically. The

semantic

relations between the derived and the deriving word are varied and

sometimes

complicated. To mention only some of them: a) the verb signifies the

act

accomplished

by or by means of the thing denoted by the noun, as: to

finger means

‘to

touch with the finger, turn about in fingers’; to

hand means

‘to give or help with

the

hand, to deliver, transfer by hand’; b) the verb may have the meaning

‘to act as the

person

denoted by the noun does’, as: to

dog means

‘to follow closely’, to

cook — ‘to

prepare

food for the table, to do the work of a cook’; c) the derived verbs

may have

the

meaning ‘to go by’ or ‘to travel by the thing denoted by the noun’,

as, to

train

means

‘to go by train’, to

bus — ‘to

go by bus’, to

tube — ‘to

travel by tube’; d) ‘to

spend,

pass the time denoted by the noun’, as, to

winter ‘to pass

the winter’, to

weekend

— ‘to

spend the week-end’.

88

Derived

nouns denote: a) the act, as a

knock, a hiss, a smoke; or

b) the result of

an

action, as a

cut, a find, a call, a sip, a run.

A

characteristic feature of Modern English is the growing frequency of

new

formations

by conversion, especially among verbs.

Note.

A grammatical homonymy of two words of different parts of speech —

a

verb

and a noun, however, does not necessarily indicate conversion. It may

be the

result

of the loss of endings as well. For instance, if we take the

homonymic pair love

— to

love and

trace it back, we see that the noun love

comes

from Old English lufu,

whereas

the verb to

love—from

Old English lufian,

and

the noun answer

is

traced

back

to the Old English andswaru,

but

the verb to

answer to

Old English

andswarian;

so

that it is the loss of endings that gave rise to homonymy. In the

pair

bus

— (to) bus, weekend — (to) weekend homonymy

is the result of derivation by

conversion.

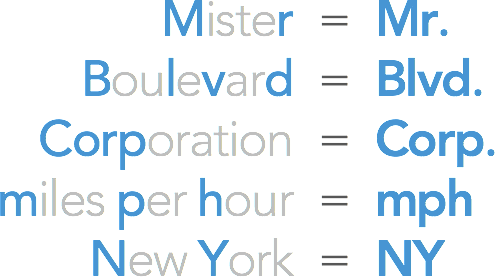

Shortenings

(abbreviations)

are words produced either by means of clipping

full

word or by shortening word combinations, but having the meaning of

the full

word

or combination. A distinction is to be observed between graphical

and

lexical

shortenings;

graphical abbreviations are signs or symbols that stand for the full

words

or combination of words only in written speech. The commonest form is

an

initial

letter or letters that stand for a word or combination of words. But

to prevent

ambiguity

one or two other letters may be added. For instance: p.

(page),

s.

(see),

b.

b.

(ball-bearing).

Mr

(mister),

Mrs

(missis),

MS

(manuscript),

fig.

(figure). In oral

speech

graphical abbreviations have the pronunciation of full words. To

indicate a

plural

or a superlative letters are often doubled, as: pp.

(pages). It is common practice

in

English to use graphical abbreviations of Latin words, and word

combinations, as:

e.

g. (exampli

gratia), etc.

(et cetera), i.

e. (id

est). In oral speech they are replaced by

their

English equivalents, ‘for

example’,

‘and

so on’,

‘namely‘,

‘that

is’,

‘respectively’.

Graphical

abbreviations are not words but signs or symbols that stand for the

corresponding

words. As for lexical

shortenings,

two main types of lexical

shortenings

may be distinguished: 1) abbreviations

or

clipped

words (clippings)

and

2) initial

words (initialisms).

Abbreviation

or

clipping

is

the result of reduction of a word to one of its

parts:

the meaning of the abbreviated word is that of the full word. There

are different

types

of clipping: 1) back-clipping—the

final part of the word is clipped, as: doc

—

from

doctor,

lab — from

laboratory,

mag — from

magazine,

math — from

mathematics,

prefab —

from prefabricated;

2) fore-clipping

—

the first part of the

word

is clipped as: plane

— from

aeroplane,

phone — from

telephone,

drome —

from

aerodrome.

Fore-clippings

are less numerous in Modern English; 3) the

fore

and

the back parts of the word are clipped and the middle of the word is

retained,

as: tec

— from

detective,

flu — from

influenza.

Words

of this type are few

in

Modern English. Back-clippings are most numerous in Modern English

and are

characterized

by the growing frequency. The original may be a simple word (as,

grad—from

graduate),

a

derivative (as, prep—from

preparation),

a

compound, (as,

foots

— from

footlights,

tails — from

tailcoat),

a

combination of words (as pub —

from

public

house, medico — from

medical

student). As

a result of clipping usually

nouns

are produced, as pram

— from

perambulator,

varsity — for

university.

In

some

89

rare

cases adjectives are abbreviated (as, imposs

—from

impossible,

pi — from

pious),

but

these are infrequent. Abbreviations or clippings are words of one

syllable

or

of two syllables, the final sound being a consonant or a vowel

(represented by the

letter

o), as, trig

(for

trigonometry),

Jap (for

Japanese),

demob (for

demobilized),

lino

(for

linoleum),

mo (for

moment).

Abbreviations

are made regardless of whether the

remaining

syllable bore the stress in the full word or not (cp. doc

from

doctor,

ad

from

advertisement).

The

pronunciation of abbreviations usually coincides with the

corresponding

syllable in the full word, if the syllable is stressed: as, doc

[‘dOk]

from

doctor

[‘dOktq];

if it is an unstressed syllable in the full word the pronunciation

differs,

as the abbreviation has a full pronunciation: as, ad

[xd],

but advertisement

[qd’vq:tismqnt].

There may be some differences in spelling connected with the

pronunciation

or with the rules of English orthoepy, as mike

— from

microphone,

bike

— from

bicycle,

phiz —

from physiognomy,

lube — from

lubrication.

The

plural

form

of the full word or combinations of words is retained in the

abbreviated word,

as,

pants

— from

pantaloons,

digs — from

diggings.

Abbreviations

do not differ from full words in functioning; they take the plural

ending

and that of the possessive case and make any part of a sentence.

New

words may be derived from the stems of abbreviated words by

conversion

(as

to

demob, to taxi, to perm) or

by affixation, chiefly by adding the suffix —y,

-ie,

deriving

diminutives and petnames (as, hanky

— from

handkerchief,

nighty (nightie)

— from

nightgown,

unkie — from

uncle,

baccy — from

tobacco,

aussie — from

Australians,

granny (ie)

— from grandmother).

In

this way adjectives also may be

derived

(as: comfy

— from

comfortable,

mizzy — from

miserable).

Adjectives

may be

derived

also by adding the suffix -ee,

as:

Portugee

— for

Portuguese,

Chinee — for

Chinese.

Abbreviations

do not always coincide in meaning with the original word, for

instance:

doc

and

doctor

have

the meaning ‘one who practises medicine’, but doctor

is

also

‘the highest degree given by a university to a scholar or scientist

and ‘a person

who

has received such a degree’ whereas doc

is

not used in these meanings. Among

abbreviations

there are homonyms, so that one and the same sound and graphical

complex

may represent different words, as vac

(vacation), vac (vacuum cleaner);

prep

(preparation), prep (preparatory school). Abbreviations

usually have synonyms

in

literary English, the latter being the corresponding full words. But

they are not

interchangeable,

as they are words of different styles of speech. Abbreviations are

highly

colloquial; in most cases they belong to slang. The moment the longer

word

disappears

from the language, the abbreviation loses its colloquial or slangy

character

and

becomes a literary word, for instance, the word taxi

is

the abbreviation of the

taxicab

which,

in its turn, goes back to taximeter

cab; both

words went out of use,

and

the word taxi

lost

its stylistic colouring.

Initial

abbreviations (initialisms)

are words — nouns — produced by

shortening

nominal combinations; each component of the nominal combination is

shortened

up to the initial letter and the initial letters of all the words of

the

combination

make a word, as: YCL — Young

Communist League, MP

—

Member

of Parliament. Initial

words are distinguished by their spelling in capital

letters

(often separated by full stops) and by their pronunciation — each

letter gets

90

its

full alphabetic pronunciation and a full stress, thus making a new

word as R.

A.

F. [‘a:r’ei’ef] — Royal

Air Force; TUC.

[‘ti:’ju:’si:] — Trades

Union Congress.

Some

of initial words may be pronounced in accordance with the’ rules of

orthoepy,

as N. A. T. O. [‘neitou], U. N. O. [‘ju:nou], with the stress on the

first

syllable.

The

meaning of the initial word is that of the nominal combination. In

speech

initial words function like nouns; they take the plural suffix, as

MPs, and

the

suffix of the possessive case, as MP’s, POW’s.

In

Modern English the commonest practice is to use a full combination

either

in

the heading or in the text and then quote this combination by giving

the first initial

of

each word. For instance, «Jack Bruce is giving UCS concert»

(the heading). «Jack

Bruce,

one of Britain’s leading rock-jazz musicians, will give a benefit

concert in

London

next week to raise money for the Upper Clyde shop stewards’ campaign»

(Morning

Star).

New

words may be derived from initial words by means of adding affixes,

as

YCL-er,

ex-PM, ex-POW; MP’ess, or adding the semi-suffix —man,

as

GI-man.

As

soon

as the corresponding combination goes out of use the initial word

takes its place

and

becomes fully established in the language and its spelling is in

small letters, as

radar

[‘reidq]

— radio detecting and ranging, laser

[‘leizq]

— light amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation; maser

[‘meizq]

— microwave amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation. There are also semi-shortenings, as, A-bomb

(atom

bomb),

H-bomber

(hydrogen

bomber), U-boat

(Untersee

boat) — German submarine.

The

first component of the nominal combination is shortened up to the

initial letter,

the

other component (or components) being full words.

4.7.

ENGLISH PHRASEOLOGY: STRUCTURAL AND SEMANTIC

PECULIARITIES

OF PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS, THEIR CLASSIFICATION

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

Main approaches to the definition of a phraseological unit in

linguistics.

2.

Different classifications of phraseological units.

3.

Grammatical and lexical modifications of phraseological units in

speech.

In

linguistics there are two main theoretical schools treating the

problems of

English

phraseology — that of N.N.Amosova and that of A. V. Kunin. We shall

not

dwell

upon these theories in detail, but we shall try to give the guiding

principles of

each

of the authors. According to the theory of N.N. Amosova. A

phraseological unit

is

a unit of constant context. It is a stable combination of words in

which either one of

the

components has a phraseologically bound meaning — a phraseme: white

lie –

невинная

ложь, husband

tea —

жидкий чай), or the meaning of each component is

weakened,

or entirely lost – (an idiom: red

tape —

бюрократия, mare’s

nest —

абсурд).

A. V. Kunin’s theory is based on the concept of specific stability at

the

phraseological

level; phraseological units are crtaracterized by a certain minimum

of

phraseological

stability. A.V. Kunin distinguishes stability of usage, structural

and

semantic

stability, stability of meaning and lexical constituents,

morphological

stability

and syntactical stability. The degree of stability may vary so that

there are

91

several

‘limits’ of stability. But whatever the degree of stability might

be, it is the

idiomatic

meaning that makes the characteristic feature of a phraseological

unit.

There

is one trend more worth mentioning in the theory of English

phraseology

that

of A. I. Smirnitsky. A.I. Smirnitsky takes as his guiding principle

the equivalence

of

a phraseological unit to a word. There are two characteristic

features that make a

phraseological

unit equivalent to a word, namely, the integrity of meaning and the

fact

that both the word and the phraseological unit are ready-made units

which are

reproduced

in speech and are not organized at the speaker’s will.

Whatever

the theory the term phraseology is applied to stable combinations of

words

characterized by the integrity of meaning which is completely or

partially

transferred,

e. g.: to

lead the dance проявлять

инициативу; to

take the cake

одержать

победу. Phraseological units are not to be mixed up with stable

combinations

of words that have their literal meaning, and are of non

phraseological

character,

e.g. the

back of the head, to come to an end.

Among

the phraseological units N.N.Amosova distinguishes idioms,

i.e.

phraseological

units characterized by the integral meaning of the whole, with the

meaning

of each component weakened or entirely lost. Hence, there are

motivated

and

demotivated

idioms.

In a motivated idiom the meaning of each component is

dependent

upon the transferred meaning of the whole idiom, e. g. to

look through

one’s

fingers (смотреть

сквозь пальцы); to

show one’s cards (раскрыть

свои

карты).

Phraseological units like these are homonymous to free syntactical

combinations.

Demotivated idioms are characterized by the integrity of meaning as a

whole,

with the meaning of each of the components entirely lost, e. g. white

elephant

(обременительное

или разорительное имущество), or to

show the white feather

(cтpycить).

But there are no hard and fast boundaries between them and there may

be

many

borderline cases. The second type of phraseological units in N.N.

Amosova’s

classification

is a phraseme.

It is a combination of words one element of which has a

phraseologically

bound meaning, e. g. small

years (детские

годы); small

beer

(слабое

пиво).

According

to A.I. Smirnitsky phraseological units may be classified in respect

to

their structure into one-summit

and

many-summit

phraseological units.

Onesummit

phraseological

units are composed of a notional and a form word, as, in

the

soup

—

быть в затруднительном положении, at

hand —

рядом, under

a cloud –

в

плохом

настроении, by

heart —

наизусть,

in the pink –

в расцвете. Many-summit

phraseological

units are composed of two or more notional words and form words as,

to

take the bull by the horns —

взять быка зарога,

to wear one’s heart on one’s

sleeve

—

выставлять свои чувства на показ, to

kill the goose that laid the golden

eggs

—

уничтожить источник благосостояния;

to

know on which side one’s bread

is

buttered —

быть себе на уме.

Academician

V.V.Vinogradov’s classification is based on the degree of

idiomaticity

and distinguishes three groups of phraseological units:

phraseological

fusions,

phraseological unities, phraseological collocations.

Phraseological

fusions are

completely non-motivated word-groups, e.g.: red

tape

– ‘bureaucratic

methods’; kick

the bucket – die,

etc. Phraseological

unities are

92

partially

non-motivated as their meaning can usually be understood through the

metaphoric

meaning of the whole phraseological unit, e.g.: to

show one’s teeth –

‘take

a threatening tone’; to

wash one’s dirty linen in public – ‘discuss

or make public

one’s

quarrels’.

Phraseological

collocations are

motivated but they are made up of

words

possessing specific lexical combinability which accounts for a

strictly limited

combinability

of member-words, e.g.: to

take a liking (fancy) but

not to

take hatred

(disgust).

There

are synonyms among phraseological units, as, through

thick and thin, by

hook

or by crook, for love or money —

во что бы то ни стало; to

pull one’s leg, to

make

a fool of somebody —

дурачить;

to hit the right nail on the head, to get the

right

sow by the ear —

попасть в точку.

Some

idioms have a variable component, though this variability is.

strictly

limited

as to the number and as to words themselves. The interchangeable

components

may be either synonymous, as

to fling (or throw) one’s (or the) cap over

the

mill (or windmill), to put (or set) one’s (or the) best foot first

(foremost, foreward)

or

different words, not connected semantically,

as to be (or sound, or read) like a

fairy

tale.

Some

of the idioms are polysemantic, as, at

large —

1) на свободе, 2) в

открытом

море, на большом пространстве, 3) без

определенной цели, 4) не

попавший

в цель, 5) свободный, без определенных

занятий, 6) имеющий

широкие

полномочия, 7) подробно, во всем объеме,

конкретно.

It

is the context or speech situation that individualizes the meaning of

the

idiom

in each case.

When

functioning in speech, phraseological units form part of a sentence

and

consequently

may undergo grammatical and lexical changes. Grammatical changes

are

connected with the grammatical system of the language as a whole,

e.g.: He

didn’t

work,

and he spent a great deal of money, and he

painted the town red.

(W. S.

Maugham)

(to

paint the town red —

предаваться веселью). Here

the infinitive is

changed

into the Past Indefinite. Components of an idiom can be used in

different

clauses,

e.g.: …I

had to put up with, the

bricks they

dropped,

and their embarassment

when

they realized what they’d done.

(W. S. Maugham) (to

drop a brick —

допустить

бестактность).

Possessive

pronouns or nouns in the possessive case may be also added, as:

…the

apple of his uncle’s eye…(A.

Christie) (the

apple of one’s eye —

зеница ока).

But

there are phraseological units that do not undergo any changes, e.

g.: She

was

the friend in adversity; other people’s business was meat

and drink to her. (W.

S.

Maugham) (be)

meat and drink (to somebody)

— необходимо как воздух.

Thus,

we distinguish changeable and unchangeable phraseological units.

Lexical

changes are much more complicated and much more various. Lexical

modifications

of idioms achieve a stylistic and expressive effect. It is an

expressive

device

at the disposal of the writer or of the speaker. It is the integrity

of meaning that

makes

any modifications in idioms possible. Whatever modifications or

changes an

idiom

might’ undergo, the integrity of meaning is never broken. Idioms may

undergo

93

various

modifications. To take only some of them: a word or more may be

inserted to

intensify

and concretize the meaning, making it applicable to this particular

situation:

I

hate the idea of Larry making such

a mess of

his life.

(W. S. Maugham) Here the

word

such

intensifies

the meaning of the idiom. I

wasn’t keen on washing

this kind of

dirty

linen in

public. (C.

P. Snow) In this case the inserted this

kind makes

the

situation

concrete.

To

make the utterance more expressive one of the components of the idiom

may

be replaced by some other. Compare: You’re

a

dog in the manger,

aren’t you,

dear?

and: It was true enough: indeed she was a

bitch in the manger.

(A.

Christie)

The

word bitch

has

its own lexical meaning, which, however, makes part of the

meaning

of the whole idiom.

One

or more components of the idiom may be left out, but the integrity of

meaning

of the whole idiom is retained, e.g.: «I’ve

never spoken to you or anyone else

about

the last election. I suppose I’ve got to now. It’s better to

let it lie,»

said Brown.

(C.

P. Snow) In the idiom let

sleeping dogs lie two

of the elements are missing and it

refers

to the preceding text.

In

the following text the idiom to

have a card up one’s sleeve is

modified:

Bundle

wondered vaguely what it was that Bill had

or thought he had-up in his

sleeve.

(A, Christie) The component card

is

dropped and the word have

realizes

its

lexical

meaning. As a result an, allusive metaphor is achieved.

The

following text presents an interesting instance of modification: She

does

not

seem to think you are a

snake in the grass,

though she sees a good deal of grass

for

a snake to be in. (E.

Bowen) In the first part of the sentence the idiom a

snake in

the

grass is

used, and in the second part the words snake

and

grass

have

their own

lexical

meanings, which are, however, connected with the integral meaning of

the

idiom.

Lexical

modifications are made for stylistic purposes so as to create an

expressive

allusive metaphor.

LITERATURE

1.

Arnold I.V. The English Word. – М., 1986.

2.

Antrushina G.B. English Lexicology. – М., 1999.

3.

Ginzburg R.Z., Khidekel S.S. A Course in Modern English

Lexicology. – М.,

1975.

4.

Kashcheyeva M.A. Potapova I.A. Practical English lexicology. – L.,

1974.

5.

Raevskaya N.N. English Lexicology. – К., 1971.

Subjects>Hobbies>Toys & Games

Wiki User

∙ 12y ago

Best Answer

Copy

I think you are referring to what is called an «acronym.» For example, the word «Scuba» (as in scuba diving) is an acronym. «Scuba» stands for Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus.

Wiki User

∙ 12y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What word means a group of letters where each letter stands for a word?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

An acronym (pronounced AK-ruh-nihm, from Greek acro- in the sense of extreme or tip and onyma or name) is an abbreviation of several words in such a way that the abbreviation itself forms a pronounceable word. The word may already exist or it can be a new word. Webster’s cites SNAFU and RADAR, two terms of World War Two vintage, as examples of acronyms that were created.

Many organizations and corporate entities use acronyms as names. Furthermore, acronyms, along with related initialisms an abbreviations, are frequently used as industry terms, such as with manufacturing.

How is an acronym defined?

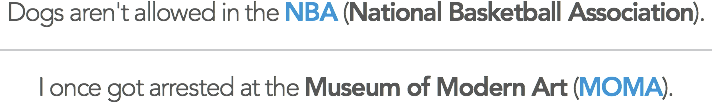

According to the strictest definition of an acronym, only abbreviations that are pronounced as words qualify. So by these standards, for example, COBOL is an acronym because it’s pronounced as a word but WHO (World Health Organization) is not an acronym because the letters in the abbreviation are pronounced individually. However, opinions differ on what constitutes an acronym: Merriam-Webster, for example, says that an acronym is just «a word formed from the initial letters of a multi-word name.»

Frequently, acronyms are formed that use existing words (and sometimes the acronym is invented first and the phrase name represented is designed to fit the acronym). Here are some examples of acronyms that use existing words:

BASIC (Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code)

NOW (National Organization for Women)

OASIS (Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards)

Acronyms vs. abbreviations vs. initialisms

Abbreviations that use the first letter of each word in a phrase are sometimes referred to as initialisms. Initialisms can be but are not always acronyms. AT&T, BT, CBS, CNN, IBM, and NBC are initialisms that are not acronyms. Many acronym lists you’ll see are really lists of acronyms and initialisms or just lists of abbreviations. (Note that abbreviations include shortened words like «esp.» for «especially» as well as shortened phrases.)

Summing up:

- An abbreviation is a shortening of a word or a phrase.

- An acronym is an abbreviation that forms a word.

- An initialism is an abbreviation that uses the first letter of each word in the phrase (thus, some but not all initialisms are acronyms).

Other related terms

Related terns to acronyms include the anacronym, recursive acronym, backronym, and apronym.

- An acronym so familiar that no one remembers what it stands for is called an anacronym (For example, few people know that COBOL stands for Common Business Oriented Language.)

- An acronym in which one of the letters stands for the actual word abbreviated therein is called a recursive acronym. (For example, VISA is said to stand for VISA International Service Association.)

- An acronym in which the short form was original and words made up to stand for it afterwards is called a backronym. (For example, SOS was originally chosen as a distress signal because it lent itself well to Morse code. Long versions, including Save Our Ship and Save our Souls, came later.)

- An acronym whose letters spell a word meaningful in the context of the term it stands for is called an apronym. (For example, BASIC, which stands for Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code, is a very simple programming language.)

This was last updated in December 2020

Continue Reading About acronym

- The Acronym Finder allows you to search for the spelled-out version of an acronym or an initialism.

- Writing for business: which is correct — OS’s, OSes or OSs?

- Writing for business: articles, acronyms and initialisms — use “a” or “an”?

- Writing for business: acronyms and initialisms ending in «s» and possession

- Acronym-based passwords

An acronym is a word or name consisting of parts of the full name’s words. Acronyms are usually formed from the initial letters of words, as in NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization), but sometimes use syllables, as in Benelux (short for Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), NAPOCOR (National Power Corporation), and TRANSCO (National Transmission Corporation). They can also be a mixture, as in radar (Radio Detection And Ranging) and MIDAS (Missile Defense Alarm System).

Acronyms can be pronounced as words, like NASA and UNESCO; as individual letters, like CIA, TNT, NPC, BLM, and ATM; or as both letters and words, like JPEG (JAY-peg), CSIS (SEE-sis), and IUPAC (I-U-pak). Some are not universally pronounced one way or the other and it depends on the speaker’s preference or the context in which it is being used, such as SQL (either «sequel» or «ess-cue-el«).

The broader sense of acronym—the meaning of which includes terms pronounced as individual letters— is sometimes criticized, but that is the term’s original meaning,[1] and is still in common use.[2] Dictionary and style-guide editors are not in universal agreement on the naming for such abbreviations, and it is a matter of some dispute whether the term acronym can be legitimately applied to abbreviations which are not pronounced «as words», nor do these language authorities agree on the correct use of spacing, casing, and punctuation.

Abbreviations formed from a string of initials and usually pronounced as individual letters are sometimes more specifically called initialisms[3] or alphabetisms; examples are FBI from Federal Bureau of Investigation, ABS-CBN from Alto Broadcasting System – Chronicle Broadcasting Network, GMA from Global Media Arts, NPC from National Power Corporation, NGCP from National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, and e.g. from Latin exempli gratia.

EtymologyEdit

The word acronym is formed from the Greek roots acr-, meaning «height, summit, or tip» and -onym, meaning «name».[4] This neoclassical compound appears to have originated in German, with attestations for the German form Akronym appearing as early as 1921.[5] Citations in English date to a 1940 translation of a novel by the German writer Lion Feuchtwanger.[6]

NomenclatureEdit

Whereas an abbreviation may be any type of shortened form, such as words with the middle omitted (for example, Rd. for Road or Dr. for Doctor) or the end truncated (as in Prof. for Professor), an acronym is—in the broad sense—formed from the first letter or first few letters of each important word in a phrase (such as AIDS, from acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome, and scuba from self-contained underwater breathing apparatus).[7] However, this is only a loose rule of thumb, as some acronyms are built in part from the first letters of morphemes (word components; as in the i and d in immuno-deficiency) or using a letter from the middle or end of a word, or from only a few key words in a long phrase or name. Less significant words such as in, of, and the are usually dropped (NYT for The New York Times, DMV for Department of Motor Vehicles), but not always (TICA for The International Cat Association, DOJ for Department of Justice).

Abbreviations formed from a string of initials and usually pronounced as individual letters (as in FBI from Federal Bureau of Investigation, and e.g. from Latin exempli gratia) are sometimes more specifically called initialisms[3] or alphabetisms. Occasionally, some letter other than the first is chosen, most often when the pronunciation of the name of the letter coincides with the pronunciation of the beginning of the word (example: BX from base exchange). Acronyms that are usually pronounced as words, such as AIDS and scuba, are sometimes called word acronyms, to disambiguate them more clearly from initialisms, especially since some users of the term «initialism» use «acronym» in a narrow sense meaning only the type sounded out as letters. Another sub-type of acronym (or a related form, depending upon one’s definitions) is the syllabic abbreviation, which is composed specifically of multi-letter syllabic (even multi-syllabic) fragments of the abbreviated words; some examples are FOREX from foreign exchange, and Interpol from international + police, though its full proper name in English is the International Criminal Police Organization. Usually the first syllable (or two) is used from each major component word, but there are exceptions, such as the U.S. Navy term DESRON or DesRon from destroyer squadron.

There is no special term for abbreviations whose pronunciation involves the combination of letter names with words, or with word-like pronunciations of strings of letters, such as JPEG () and MS-DOS (). Similarly, there is no unique name for those that are a mixture of syllabic abbreviations and initialisms; these are usually pronounced as words (e.g., radar from radio detection and ranging, consisting of one syllabic abbreviation and three single letters, and sonar from sound navigation ranging, consisting of two syllabic abbreviations followed by a single acronymic letter for ranging); these would generally qualify as word acronyms among those who use that term. There is also some disagreement as to what to call an abbreviation that some speakers pronounce as letters but others pronounce as a word. For example, the terms URL and IRA (for individual retirement account) can be pronounced as individual letters: and , respectively; or as a single word: and , respectively. The same character string may be pronounced differently when the meaning is different; IRA is always sounded out as I-R-A when standing for Irish Republican Army.

The spelled-out form of an acronym, initialism, or syllabic abbreviation (that is, what that abbreviation stands for) is called its expansion.

Lexicography and style guidesEdit

It is an unsettled question in English lexicography and style guides whether it is legitimate to use the word acronym to describe forms that use initials but are not pronounced as a word. While there is plenty of evidence that acronym is used widely in this way, some sources do not acknowledge this usage, reserving the term acronym only for forms pronounced as a word, and using initialism or abbreviation for those that are not. Some sources acknowledge the usage, but vary in whether they criticize or forbid it, allow it without comment, or explicitly advocate for it.

Some mainstream English dictionaries from across the English-speaking world affirm a sense of acronym which does not require being pronounced as a word. American English dictionaries such as Merriam-Webster,[8] Dictionary.com’s Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary[9] and the American Heritage Dictionary[10] as well as the British Oxford English Dictionary[1] and the Australian Macquarie Dictionary[11] all include a sense in their entries for acronym equating it with initialism, although The American Heritage Dictionary criticizes it with the label «usage problem».[10] However, many English language dictionaries, such as the Collins COBUILD Advanced Dictionary,[12] Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary,[13] Macmillan Dictionary,[14] Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English,[15] New Oxford American Dictionary,[16] Webster’s New World Dictionary,[17] and Lexico from Oxford University Press[18] do not acknowledge such a sense.

Most of the dictionary entries and style guide recommendations regarding the term acronym through the twentieth century did not explicitly acknowledge or support the expansive sense. The Merriam–Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage from 1994 is one of the earliest publications to advocate for the expansive sense,[19] and all the major dictionary editions that include a sense of acronym equating it with initialism were first published in the twenty-first century. The trend among dictionary editors appears to be towards including a sense defining acronym as initialism: The Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary added such a sense in its eleventh edition in 2003,[20][21] and both the Oxford English Dictionary[22][1] and the American Heritage Dictionary[23][10] added such senses in their 2011 editions. The 1989 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary only included the exclusive sense for acronym and its earliest citation was from 1943.[22] In early December 2010, Duke University researcher Stephen Goranson published a citation for acronym to the American Dialect Society e-mail discussion list which refers to PGN being pronounced «pee-gee-enn,» antedating English language usage of the word to 1940.[24] Linguist Ben Zimmer then mentioned this citation in his December 16, 2010 «On Language» column about acronyms in The New York Times Magazine.[25] By 2011, the publication of the third edition of the Oxford English Dictionary added the expansive sense to its entry for acronym and included the 1940 citation.[1] As the Oxford English Dictionary structures the senses in order of chronological development,[26] it now gives the «initialism» sense first.

English language usage and style guides which have entries for acronym generally criticize the usage that refers to forms that are not pronounceable words. Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage says that acronym «denotes abbreviations formed from initial letters of other words and pronounced as a single word, such as NATO (as distinct from B-B-C)» but adds later «In everyday use, acronym is often applied to abbreviations that are technically initialisms, since they are pronounced as separate letters.»[27] The Chicago Manual of Style acknowledges the complexity («Furthermore, an acronym and initialism are occasionally combined (JPEG), and the line between initialism and acronym is not always clear») but still defines the terms as mutually exclusive.[28] Other guides outright deny any legitimacy to the usage: Bryson’s Dictionary of Troublesome Words says «Abbreviations that are not pronounced as words (IBM, ABC, NFL) are not acronyms; they are just abbreviations.»[29] Garner’s Modern American Usage says «An acronym is made from the first letters or parts of a compound term. It’s read or spoken as a single word, not letter by letter.»[30] The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage says «Unless pronounced as a word, an abbreviation is not an acronym.»[31]

In contrast, some style guides do support it, whether explicitly or implicitly. The 1994 edition of Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage defends the usage on the basis of a claim that dictionaries do not make a distinction.[19] The BuzzFeed style guide describes CBS and PBS as «acronyms ending in S».[32]

Comparing a few examples of each typeEdit

- Pronounced as a word, containing only initial letters

- NATO: «North Atlantic Treaty Organization»

- Scuba: «self-contained underwater breathing apparatus»

- Laser: «light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation»

- GIF: «graphics interchange format»

- OWCA: «Organization Without a Cool Acronym»

- Pronounced as a word, containing a mixture of initial and non-initial letters

- Amphetamine: «alpha-methyl-phenethylamine»

- Gestapo: Geheime Staatspolizei (secret state police)

- Radar: «radio detection and ranging»

- Lidar: «light detection and ranging»

- Pronounced as a combination of spelling out and a word

- CD-ROM: (cee-dee-) «compact disc read-only memory»

- IUPAC: (i-u- or i-u-pee-a-cee) «International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry»

- JPEG: (jay- or jay-pee-e-gee) «Joint Photographic Experts Group»

- SFMOMA: (ess-ef- or ess-ef-em-o-em-a) «San Francisco Museum of Modern Art»

- Pronounced only as a string of letters

- BBC: «British Broadcasting Corporation»

- OEM: «original equipment manufacturer»

- USA: «United States of America»

- VHF: «very high frequency»

- Pronounced as a string of letters, but with a shortcut

- AAA:

- (Triple-A) «American Automobile Association»; «abdominal aortic aneurysm»; «anti-aircraft artillery»; «Asistencia, Asesoría y Administración»

- (Three-As) «Amateur Athletic Association»

- IEEE: (I triple-E) «Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers»

- NAACP: (N double-A C P or N A A C P) «National Association for the Advancement of Colored People»

- NCAA: (N C double-A or N C two-A or N C A A) «National Collegiate Athletic Association»

- AAA:

- Shortcut incorporated into name

- 3M: (three M) originally «Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company»

- W3C: (W-three C) «World Wide Web Consortium»

- A2DP: (A-two D P) «Advanced Audio Distribution Profile»

- I18N: («18» stands in for the word’s middle eighteen letters, «nternationalizatio») «Internationalization»

- C4ISTAR: (C-four Istar) «Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition, and Reconnaissance»[33]

- Mnemonic acronyms, an abbreviation that is used to remember phrases or principles

- KISS (Kiss) «Keep it simple, stupid», a design principle preferring simplicity

- SMART (Smart) «Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, Time-related», A principle of setting of goals and objectives

- FAST (Fast) «Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, Time», helps detect and enhance responsiveness to the needs of a person having a stroke

- DRY (Dry) «Don’t repeat yourself», A principle of software development aimed at reducing repetition of software patterns

- Multi-layered acronyms

- AIM: «AOL Instant Messenger,» in which «AOL» originally stood for «America Online»

- AFTA: «ASEAN Free Trade Area,» where ASEAN stands for «Association of Southeast Asian Nations»

- NAC Breda: (Dutch football club) «NOAD ADVENDO Combinatie» («NOAD ADVENDO Combination»), formed by the 1912 merger of two clubs from Breda:

- NOAD: (Nooit Opgeven Altijd Doorgaan «Never give up, always persevere»)

- ADVENDO: (Aangenaam Door Vermaak En Nuttig Door Ontspanning «Pleasant by entertainment and useful by relaxation»)[34][35]

- GIMP: «GNU image manipulation program»

- Recursive acronyms, in which the abbreviation refers to itself

- GNU: «GNU’s not Unix!»

- Wine: «Wine is not an emulator» (originally, «Windows emulator»)

- These may go through multiple layers before the self-reference is found:

- HURD: «HIRD of Unix-replacing daemons,» where «HIRD» stands for «HURD of interfaces representing depth»

- Pseudo-acronyms, which consist of a sequence of characters that, when pronounced as intended, invoke other, longer words with less typing[36] This makes them gramograms.

- CQ: cee-cue for «seek you», a code used by radio operators

- IOU: i-o-u for «I owe you»

- K9: kay-nine for «canine,» used to designate police units using dogs

- Abbreviations whose last abbreviated word is often redundantly included anyway

- ATM machine: «automated teller machine» (machine)

- HIV virus: «human immunodeficiency virus» (virus)

- LCD display: «liquid-crystal display» (display)

- PIN number: «personal identification number» (number)

- Pronounced as a word, containing letters as a word in itself

- PAYGO: «pay-as-you-go»

Historical and current useEdit

Acronymy, like retronymy, is a linguistic process that has existed throughout history but for which there was little to no naming, conscious attention, or systematic analysis until relatively recent times. Like retronymy, it became much more common in the 20th century than it had formerly been.

Ancient examples of acronymy (before the term «acronym» was invented) include the following:

- Acronyms were used in Rome before the Christian era. For example, the official name for the Roman Empire, and the Republic before it, was abbreviated as SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus). Inscriptions dating from antiquity, both on stone and on coins, use many abbreviations and acronyms to save space and work. For example, Roman first names, of which there was only a small set, were almost always abbreviated. Common terms were abbreviated too, such as writing just «F» for filius, meaning «son», a very common part of memorial inscriptions mentioning people. Grammatical markers were abbreviated or left out entirely if they could be inferred from the rest of the text.

- So-called nomina sacra (sacred names) were used in many Greek biblical manuscripts. The common words «God» (Θεός), «Jesus» (Ιησούς), «Christ» (Χριστός), and some others, would be abbreviated by their first and last letters, marked with an overline. This was just one of many kinds of conventional scribal abbreviation, used to reduce the time-consuming workload of the scribe and save on valuable writing materials. The same convention is still commonly used in the inscriptions on religious icons and the stamps used to mark the eucharistic bread in Eastern Churches.

- The early Christians in Rome, most of whom were Greek rather than Latin speakers, used the image of a fish as a symbol for Jesus in part because of an acronym (or backronym): «fish» in Greek is ichthys (ΙΧΘΥΣ), which was construed to stand for Ἰησοῦς Χριστός Θεοῦ Υἱός Σωτήρ (Iesous Christos Theou huios Soter: «Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior»). This interpretation dates from the 2nd and 3rd centuries and is preserved in the catacombs of Rome. Another ancient acronym for Jesus is the inscription INRI over the crucifix, for the Latin Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum («Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews»).

- The Hebrew language has a centuries-long history of acronyms pronounced as words. The Hebrew Bible («Old Testament») is known as «Tanakh», an acronym composed from the Hebrew initial letters of its three major sections: «Torah» (five books of Moses), «Nevi’im» (prophets), and «K’tuvim» (writings). Many rabbinical figures from the Middle Ages onward are referred to in rabbinical literature by their pronounced acronyms, such as Rambam and Rashi from the initial letters of their full Hebrew names: «Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon» and «Rabbi Shlomo Yitzkhaki».

During the mid- to late 19th century, acronyms became a trend among American and European businessmen: abbreviating corporation names, such as on the sides of railroad cars (e.g., «Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad» → «RF&P»); on the sides of barrels and crates; and on ticker tape and newspaper stock listings (e.g. American Telephone and Telegraph Company → AT&T). Some well-known commercial examples dating from the 1890s through 1920s include «Nabisco» («National Biscuit Company»),[37] «Esso» (from «S.O.», from «Standard Oil»), and «Sunoco» («Sun Oil Company»).

Another field for the adoption of acronyms was modern warfare, with its many highly technical terms. While there is no recorded use of military acronyms dating from the American Civil War (acronyms such as «ANV» for «Army of Northern Virginia» postdate the war itself), they became somewhat common in World War I, and by World War II they were widespread even in the slang of soldiers,[38] who referred to themselves as G.I.s.

The widespread, frequent use of acronyms across the whole range of linguistic registers is relatively new in most languages, becoming increasingly evident since the mid-20th century. As literacy spread and technology produced a constant stream of new and complex terms, abbreviations became increasingly convenient. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) records the first printed use of the word initialism as occurring in 1899, but it did not come into general use until 1965, well after acronym had become common.

In English, acronyms pronounced as words may be a 20th-century phenomenon. Linguist David Wilton in Word Myths: Debunking Linguistic Urban Legends claims that «forming words from acronyms is a distinctly twentieth- (and now twenty-first-) century phenomenon. There is only one known pre-twentieth-century [English] word with an acronymic origin and it was in vogue for only a short time in 1886. The word is colinderies or colinda, an acronym for the Colonial and Indian Exposition held in London in that year.»[39][40] However, although acronymic words seem not to have been employed in general vocabulary before the 20th century (as Wilton points out), the concept of their formation is treated as effortlessly understood (and evidently not novel) in an Edgar Allan Poe story of the 1830s, «How to Write a Blackwood Article», which includes the contrived acronym «P.R.E.T.T.Y.B.L.U.E.B.A.T.C.H.»

Early examples in EnglishEdit

The use of Latin and Neo-Latin terms in vernaculars has been pan-European and predates modern English. Some examples of acronyms in this class are:

- A.M. (from Latin ante meridiem, «before noon») and P.M. (from Latin post meridiem, «after noon»)

- A.D. (from Latin Anno Domini, «in the year of our Lord»), whose complement in English, B.C. [Before Christ], is English-sourced

The earliest example of a word derived from an acronym listed by the OED is «abjud» (now «abjad»), formed from the original first four letters of the Arabic alphabet in the late 18th century.[41] Some acrostics predate this, however, such as the Restoration witticism arranging the names of some members of Charles II’s Committee for Foreign Affairs to produce the «CABAL» ministry.[42]

O.K., a term of disputed origin, dates back at least to the early 19th century and is now used around the world.

Current useEdit

Acronyms are used most often to abbreviate names of organizations and long or frequently referenced terms. The armed forces and government agencies frequently employ acronyms; some well-known examples from the United States are among the «alphabet agencies» (jokingly referred to as «alphabet soup») created under the New Deal by Franklin D. Roosevelt (himself known as «FDR»). Business and industry also coin acronyms prolificly. The rapid advance of science and technology also drives the usage, as new inventions and concepts with multiword names create a demand for shorter, more pronounceable names.[citation needed] One representative example, from the U.S. Navy, is «COMCRUDESPAC», which stands for «commander, cruisers destroyers Pacific»; it is also seen as «ComCruDesPac». Inventors are encouraged to anticipate the formation of acronyms by making new terms «YABA-compatible» («yet another bloody acronym»), meaning the term’s acronym can be pronounced and is not an offensive word: «When choosing a new name, be sure it is ‘YABA-compatible’.»[43]

Acronym use has been further popularized by text messaging on mobile phones with short message service (SMS), and instant messenger (IM). To fit messages into the 160-character SMS limit, and to save time, acronyms such as «GF» («girlfriend»), «LOL» («laughing out loud»), and «DL» («download» or «down low») have become popular.[44] Some prescriptivists disdain texting acronyms and abbreviations as decreasing clarity, or as failure to use «pure» or «proper» English. Others point out that languages have always continually changed, and argue that acronyms should be embraced as inevitable, or as innovation that adapts the language to changing circumstances. In this view, the modern practice is just the «proper» English of the current generation of speakers, much like the earlier abbreviation of corporation names on ticker tape or newspapers.

Exact pronunciation of «word acronyms» (those pronounced as words rather than sounded out as individual letters) often vary by speaker population. These may be regional, occupational, or generational differences, or simply personal preference. For instance, there have been decades of online debate about how to pronounce GIF ( or ) and BIOS (, , or ). Similarly, some letter-by-letter initialisms may become word acronyms over time, especially in combining forms: IP for Internet Protocol is generally said as two letters, but IPsec for Internet Protocol Security is usually pronounced as or , along with variant capitalization like «IPSEC» and «Ipsec». Pronunciation may even vary within a single speaker’s vocabulary, depending on narrow contexts. As an example, the database programming language SQL is usually said as three letters, but in reference to Microsoft’s implementation is traditionally pronounced like the word sequel.

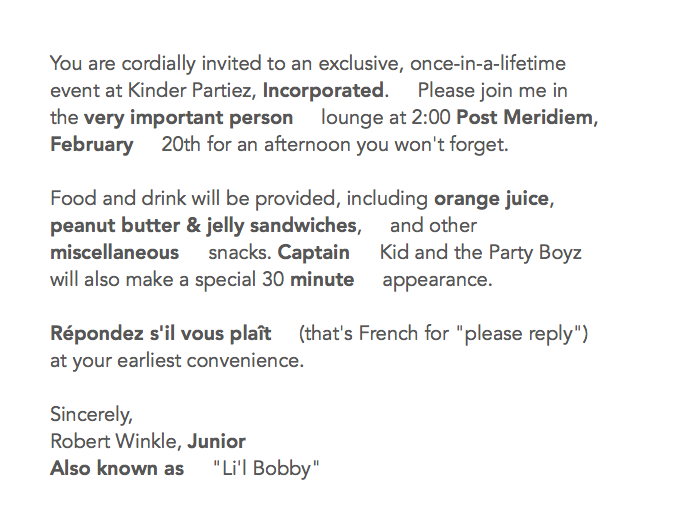

Expansion at first useEdit

In writing for a broad audience, the words of an acronym are typically written out in full at its first occurrence within a given text. Expansion At First Use (EAFU) benefits readers unfamiliar with the acronym.[45]

Another text aid is an abbreviation key which lists and expands all acronyms used, a reference for readers who skipped past the first use. (This is especially important for paper media, where no search utility is available to find the first use.) It also gives students a convenient review list to memorize the important acronyms introduced in a textbook chapter.

Expansion at first use and abbreviation keys originated in the print era, but they are equally useful for electronic text.

JargonEdit

While acronyms provide convenience and succinctness for specialists, they often degenerate into confusing jargon. This may be intentional, to exclude readers without domain-specific knowledge. New acronyms may also confuse when they coincide with an already existing acronym having a different meaning.

Medical literature has been struggling to control the proliferation of acronyms, including efforts by the American Academy of Dermatology.[46]

As mnemonicsEdit

Acronyms are often taught as mnemonic devices: for example the colors of the rainbow are ROY G. BIV (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). They are also used as mental checklists: in aviation GUMPS stands for gas-undercarriage-mixture-propeller-seatbelts. Other mnemonic acronyms include CAN SLIM in finance, PAVPANIC in English grammar, and PEMDAS in mathematics.