Will

A document in which a person specifies the method to be applied in the management and distribution of his estate after his death.

A will is the legal instrument that permits a person, the testator, to make decisions on how his estate will be managed and distributed after his death. At Common Law, an instrument disposing of Personal Property was called a «testament,» whereas a will disposed of real property. Over time the distinction has disappeared so that a will, sometimes called a «last will and testament,» disposes of both real and personal property.

If a person does not leave a will, or the will is declared invalid, the person will have died intestate, resulting in the distribution of the estate according to the laws of Descent and Distribution of the state in which the person resided. Because of the importance of a will, the law requires it to have certain elements to be valid. Apart from these elements, a will may be ruled invalid if the testator made the will as the result of undue influence, fraud, or mistake.

A will serves a variety of important purposes. It enables a person to select his heirs rather than allowing the state laws of descent and distribution to choose the heirs, who, although blood relatives, might be people the testator dislikes or with whom he is unacquainted. A will allows a person to decide which individual could best serve as the executor of his estate, distributing the property fairly to the beneficiaries while protecting their interests, rather than allowing a court to appoint a stranger to serve as administrator. A will safeguards a person’s right to select an individual to serve as guardian to raise his young children in the event of his death.

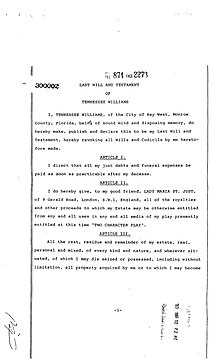

Howard Hughes and the Mormon Will

When billionaire recluse Howard Hughes died in 1976, it appeared that he had not left a will. Attorneys and executives of Hughes’s corporations began an intensive search to find a will, while speculation grew that Hughes might have left a holographic (handwritten) will. One attorney publicly stated that Hughes had asked him about the legality of a holographic will.

Soon after the attorney made the statement, a holographic will allegedly written by Hughes appeared on a desk in the Salt Lake City headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, more commonly known as the Mormon Church. After a preliminary review, a document examiner concluded that the will might have been written by Hughes. The Mormon Church then filed the will in the county court in Las Vegas, Nevada, where Hughes’s estate was being settled.

The will, which became known as the Mormon Will, drew national attention for a provision that gave one-sixteenth of the estate, valued at $156 million, to Melvin Dummar, the owner of a small gas station in Willard, Utah. Dummar told reporters that in 1975 he had picked up a man who claimed to be Howard Hughes and had dropped him off in Las Vegas.

Though Dummar first said he had no prior knowledge of the will or how it appeared at the church headquarters, he later claimed that a man drove to his service station and gave him the will with instructions to deliver it to Salt Lake City. Dummar said he had destroyed the instructions.

Investigators discovered that Dummar had checked out a library copy of a book called The Hoax, which recounted the story of Clifford Irving’s forgery of an «autobiography» of Hughes. The book contained examples of Hughes’s handwriting. Document examiners demonstrated that Hughes’s handwriting had changed before the time the Mormon Will supposedly was written. In addition, the examiners concluded that the will was a crude forgery. Nevertheless, it took a seven-month trial and millions of dollars from the Hughes estate to prove that the will was a fake. In the end, the court ruled that the will was a forgery.

No valid will was ever found. Dummar’s story later became the subject of the 1980 motion picture Melvin and Howard.

Further readings

Freese, Paul L. 1986. «Howard Hughes and Melvin Dummar: Forensic Science Fact Versus Film Fiction.» Journal of Forensic Sciences 31 (January).

Marks, Marlene Adler. 1981. «Where There’s a Will … Rhoden Recoups after Howard Hughes Fiasco.» National Law Journal (January 5).

The right to dispose of property by a will is controlled completely by statute. Since the 1970s, many states have adopted all or parts of the Uniform Probate Code, which attempts to simplify the laws concerning wills and estates. When a person dies, the law of his domicile (permanent residence) will control the method of distribution of his personal property, such as money, stock, or automobiles. The real property, such as farm or vacant land, will pass to the intended heirs according to the law of the state in which the property is located. Though a testator may exercise much control over the distribution of property, state laws protect spouses and children by providing ways of guaranteeing that a spouse will receive a minimum amount of property, regardless of the provisions of the will.

Requirements of a Will

A valid will cannot exist unless three essential elements are present. First, there must be a competent testator. Second, the document purporting to be a will must meet the execution requirements of statutes, often called the Statute of Wills, designed to ensure that the document is not a fraud but is the honest expression of the testator’s intention. Third, it must be clear that the testator intended the document to have the legal effect of a will.

If a will does not satisfy these requirements, any person who would have a financial interest in the estate under the laws of descent and distribution can start an action in the probate court to challenge the validity of the will. The persons who inherit under the will are proponents of the will and defend it against such an attack. This proceeding is known as a will contest. If the people who oppose the admission of the will to probate are successful, the testator’s estate will be distributed according to the laws of descent and distribution or the provisions of an earlier will, depending on the facts of the case.

Competent Testator A competent testator is a person who is of sound mind and requisite age at the time that he makes the will, not at the date of his death when it takes effect. Anyone over a minimum age, usually 18, is legally capable of making a will as long as he is competent. A person under the minimum age dies intestate (regardless of efforts to make a will), and his property will be distributed according to the laws of descent and distribution.

An individual has testamentary capacity (sound mind) if he is able to understand the nature and extent of his property, the natural objects of his bounty (to whom he would like to leave the estate), and the nature of the testamentary act (the distribution of his property when he dies). He must also understand how these elements are related so that he can express the method of disposition of property.

A testator is considered mentally incompetent (incapable of making a will) if he has a recognized type of mental deficiency, such as a severe mental illness. Mere eccentricities, such as the refusal to bathe, are not considered insane delusions, nor are mistaken beliefs or prejudices about family members. A person who uses drugs or alcohol can validly execute a will as long as he is not under the influence of drugs or intoxicated at the time he makes the will. Illiteracy, old age, or severe physical illness do not automatically deprive a person of a testamentary capacity, but they are factors to be considered along with the particular facts of the case.

Execution of Wills

Every state has statutes prescribing the formalities to be observed in making a valid will. The requirements relate to the writing, signing, witnessing, or attestation of the will in addition to its publication. These legislative safeguards prevent tentative, doubtful, or coerced expressions of desire from controlling the manner in which a person’s estate is distributed.

Writing Wills usually must be in writing but can be in any language and inscribed with any material or device on any substance that results in a permanent record. Generally, most wills are printed on paper to satisfy this requirement. Many states do not recognize as valid a will that is handwritten and signed by the testator. In states that do accept such a will, called a holographic will, it usually must observe the formalities of execution unless exempted by statute. Some jurisdictions also require that such wills be dated by the testator’s hand.

Signature A will must be signed by the testator. Any mark, such as an X, a zero, a check mark, or a name intended by a competent testator to be his signature to authenticate the will, is a valid signing. Some states permit another person to sign a will for a testator at the testator’s direction or request or with his consent.

Many state statutes require that the testator’s signature be at the end of the will. If it is not, the entire will may be invalidated in those states, and the testator’s property will pass according to the laws of descent and distribution. The testator should sign the will before the witnesses sign, but the reverse order is usually permissible if all sign as part of a single transaction.

Witnesses Statutes require a certain number of witnesses to a will. Most require two, although others mandate three. The witnesses sign the will and must be able to attest (certify) that the testator was competent at the time he made the will. Though there are no formal qualifications for a witness, it is important that a witness not have a financial interest in the will. If a witness has an interest, his testimony about the circumstances will be suspect because he will profit by its admission to probate. In most states such witnesses must either «purge» their interest under the will (forfeit their rights under the will) or be barred from testifying, thereby defeating the testator’s testamentary plan. If, however, the witness also would inherit under the laws of descent and distribution should the will be invalidated, he will forfeit only the interest in excess of the amount he would receive if the will were voided.

Acknowledgment A testator is usually required to publish the will—that is, to declare to the witnesses that the instrument is his will. This declaration is called an Acknowledgment. No state requires, however, that the witnesses know the contents of the will.

Although some states require a testator to sign the will in the presence of witnesses, the majority require only an acknowledgment of the signature. If a testator shows the signature on a will that he has already signed to a witness and acknowledges that it is his signature, the will is thereby acknowledged.

Attestation An attestation clause is a certificate signed by the witnesses to a will reciting performance of the formalities of execution that the witnesses observed. It usually is not required for a will to be valid, but in some states it is evidence that the statements made in the attestation are true.

Testator’s Intent

For a will to be admitted to probate, it must be clear that the testator acted freely in expressing his testamentary intention. A will executed as a result of undue influence, fraud, or mistake can be declared completely or partially void in a probate proceeding.

Undue Influence Undue influence is pressure that takes away a person’s free will to make decisions, substituting the will of the influencer. A court will find undue influence if the testator was capable of being influenced, improper influence was exerted on the testator, and the testamentary provisions reflect the effect of such influence. Mere advice, persuasion, affection, or kindness does not alone constitute undue influence.

Questions of undue influence typically arise when a will deals unjustly with persons believed to be the natural objects of the testator’s bounty. However, undue influence is not established by inequality of the provisions of the will, because this would interfere with the testator’s ability to dispose of the property as he pleases. Examples of undue influence include threats of violence or criminal prosecution of the testator, or the threat to abandon a sick testator.

Fraud Fraud differs from undue influence in that the former involves Misrepresentation of essential facts to another to persuade him to make and sign a will that will benefit the person who misrepresents the facts. The testator still acts freely in making and signing the will.

The two types of fraud are fraud in the execution and fraud in the inducement. When a person is deceived by another as to the character or contents of the document he is signing, he is the victim of fraud in the execution. Fraud in the execution includes a situation where the contents of the will are knowingly misrepresented to the testator by someone who will benefit from the misrepresentation.

Fraud in the inducement occurs when a person knowingly makes a will but its terms are based on material misrepresentations of facts made to the testator by someone who will ultimately benefit.

Persons deprived of benefiting under a will because of fraud or undue influence can obtain relief only by contesting the will. If a court finds fraud or undue influence, it may prevent the wrongdoer from receiving any benefit from the will and may distribute the property to those who contested the will.

Mistake When a testator intended to execute his will but by mistake signed the wrong document, that document will not be enforced. Such mistakes often occur when a Husband and Wife draft mutual wills. The document that bears the testator’s signature does not represent his testamentary intent, and therefore his property cannot be distributed according to its terms.

Special Types of Wills

Some states have statutes that recognize certain kinds of wills that are executed with less formality than ordinary wills, but only when the wills are made under circumstances that reduce the possibility of fraud.

Holographic Wills A holographic will is completely written and signed in the handwriting of the testator, such as a letter that specifically discusses his intended distribution of the estate after his death. Many states do not recognize the validity of holographic wills, and those that do require that the formalities of execution be followed.

Nuncupative Wills A nuncupative will is an oral will. Most states do not recognize the validity of such wills because of the greater likelihood of fraud, but those that do impose certain requirements. The will must be made during the testator’s last sickness or in expectation of imminent death. The testator must indicate to the witnesses that he wants them to witness his oral will. Such a will can dispose of only personal, not real, property.

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Wills Several states have laws that relax the execution requirements for wills made by soldiers and sailors while on active military duty or at sea. In these situations a testator’s oral or handwritten will is capable of passing personal property. Where such wills are recognized, statutes often stipulate that they are valid for only a certain period of time after the testator has left the service. In other instances, however, the will remains valid.

Revocation of a Will

A will is ambulatory, which means that a competent testator may change or revoke it at any time before his death. Revocation of a will occurs when a person who has made a will takes some action to indicate that he no longer wants its provisions to be binding and the law abides by his decision.

For revocation to be effective, the intent of the testator, whether express or implied, must be clear, and an act of revocation consistent with this intent must occur. Persons who wish to revoke a will may use a codicil, which is a document that changes, revokes, or amends part or all of a validly executed will. When a person executes a codicil that revokes some provisions of a previous will, the courts will recognize this as a valid revocation. Likewise, a new will that completely revokes an earlier will indicates the testator’s intent to revoke the will.

Statements made by a person at or near the time that he intentionally destroys his will by burning, mutilating, or tearing it clearly demonstrate his intent to revoke.

Sometimes revocation occurs by operation of law, as in the case of a marriage, Divorce, birth of a child, or the sale of property devised in the will, which automatically changes the legal duties of the testator. Many states provide that when a testator and spouse have been divorced but the testator’s will has not been revised since the change in marital status, any disposition to the former spouse is revoked.

Protection of the Family

The desire of society to protect the spouse and children of a decedent is a major reason both for allowing testamentary disposition of property and for placing limitations upon the freedom of testators.

Surviving Spouse Three statutory approaches have developed to protect the surviving spouse against disinheritance: Dower or curtesy, the elective share, and Community Property.

Dower or curtesy At common law, a wife was entitled to dower, a life interest in one-third of the land owned by her husband during the marriage. Curtesy was the right of a husband to a life interest in all of his wife’s lands. Most states have abolished common-law dower and curtesy and have enacted laws that treat husband and wife identically. Some statutes subject dower and curtesy to payment of debts, and others extend rights to personal property as well as land. Some states allow dower or curtesy in addition to testamentary provisions, though in other states dower and curtesy are in lieu of testamentary provisions.

Elective share Although a testator can dispose of his property as he wishes, the law recognizes that the surviving spouse, who has usually contributed to the accumulation of property during the marriage, is entitled to a share in the property. Otherwise, that spouse might ultimately become dependent on the state. For this reason, the elective share was created by statute in states that do not have community property.

Most states have statutes allowing a surviving spouse to elect either a statutory share (usually one-third of the estate if children survive, one-half otherwise), which is the share that the spouse would have received if the decedent had died intestate, or the provision made in the spouse’s will. As a general rule, surviving spouses are prohibited from taking their elective share if they unjustly engaged in desertion or committed bigamy.

A spouse can usually waive, release, or contract away his statutory rights to an elective share or to dower or curtesy by either an antenuptial (also called prenuptial) or postnuptial agreement, if it is fair and made with knowledge of all relevant facts. Such agreements must be in writing.

Community property A community property system generally treats the husband and wife as co-owners of property acquired by either of them during the marriage. On the death of one, the survivor is entitled to one-half the property, and the remainder passes according to the will of the decedent.

Children Generally parents can completely disinherit their children. A court will uphold such provisions if the testator specifically mentions in the will that he is intentionally disinheriting certain named children. Many states, however, have pretermitted heir provisions, which give children born or adopted after the execution of the will and not mentioned in it an intestate share, unless the omission appears to be intentional.

Other Limitations on Will Provisions

The law has made other exceptions to the general rule that a testator has the unqualified right to dispose of his estate in any way that he sees fit.

Charitable Gifts Many state statutes protect a testator’s family from disinheritance by limiting the testator’s power to make charitable gifts. Such limitations are usually operative only where close relatives, such as children, grandchildren, parents, and spouse, survive.

Charitable gifts are limited in certain ways. For example, the amount of the gift can be limited to a certain proportion of the estate, usually 50 percent. Some states prohibit deathbed gifts to charity by invalidating gifts that a testator makes within a specified period before death.

Ademption and Abatement Ademption is where a person makes a declaration in his will to leave some property to another and then reneges on the declaration, either by changing the property or removing it from the estate. Abatement is the process of determining the order in which property in the estate will be applied to the payment of debts, taxes, and expenses.

The gifts that a person is to receive under a will are usually classified according to their nature for purposes of ademption and abatement. A specific bequest is a gift of a particular identifiable item of personal property, such as an antique violin, whereas a specific devise is an identifiable gift of real property, such as a specifically designated farm.

A demonstrative bequest is a gift of a certain amount of property—$2,000, for example—out of a certain fund or identifiable source of property, such as a savings account at a particular bank.

A general bequest is a gift of property payable from the general assets of the testator’s estate, such as a gift of $5,000.

A residuary gift is a gift of the remaining portion of the estate after the satisfaction of other dispositions.

When specific devises and bequests are no longer in the estate or have been substantially changed in character at the time of the testator’s death, this is called ademption by extinction, and it occurs irrespective of the testator’s intent. If a testator specifically provides in his will that the beneficiary will receive his gold watch, but the watch is stolen prior to his death, the gift adeems and the beneficiary is not entitled to anything, including any insurance payments made to the estate as reimbursement for the loss of the watch.

Ademption by satisfaction occurs when the testator, during his lifetime, gives to his intended beneficiary all or part of a gift that he had intended to give the beneficiary in her will. The intention of the testator is an essential element. Ademption by satisfaction applies to general as well as specific legacies. If the subject matter of a gift made during the lifetime of a testator is the same as that specified in a testamentary provision, it is presumed that the gift is in lieu of the testamentary gift where there is a parent-child or grandparent-parent relationship.

In the abatement process, the intention of the testator, if expressed in the will, governs the order in which property will abate to pay taxes, debts, and expenses. Where the will is silent, the following order is usually applied: residuary gifts, general bequests, demonstrative bequests, and specific bequests and devises.

Further readings

Brown, Gordon W. 2003. Administration of Wills, Trusts, and Estates. 3d ed. Clifton Park, N.Y.: Thomson/Delmar Learning.

Cross-references

Estate and Gift Taxes; Executors and Administrators; Husband and Wife; Illegitimacy; Living Will; Parent and Child; Postmarital Agreement; Premarital Agreement; Trust.

West’s Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

will

n. a written document which leaves the estate of the person who signed the will to named persons or entities (beneficiaries, legatees, divisees) including portions or percentages of the estate, specific gifts, creation of trusts for management and future distribution of all or a portion of the estate (a testamentary trust). A will usually names an executor (and possibly substitute executors) to manage the estate, states the authority and obligations of the executor in the management and distribution of the estate, sometimes gives funeral and/or burial instructions, nominates guardians of minor children, and spells out other terms. To be valid the will must be signed by the person who made it (testator), be dated (but an incorrect date will not invalidate the will) and witnessed by two people (except in Vermont which requires three). In some states the witnesses must be disinterested, or in some states, a gift to a witness is void, but the will is valid. A will totally in the handwriting of the testator, signed and dated (a «holographic will») but without witnesses, is valid in many, but not all, states. If the will (also called a Last Will and Testament) is still in force at the time of the death of the testator (will writer), and there is a substantial estate and/or real estate, then the will must be probated (approved by the court, managed, and distributed by the executor under court supervision.) If there is no executor, named or the executor is dead or unable or unwilling to serve, an administrator («with will annexed») will be appointed by the court. A written amendment or addition to a will is called a «codicil» and must be signed, dated and witnessed just as is a will, and must refer to the original will it amends. If there is no estate, including the situation in which the assets have all been placed in a trust, then the will need not be probated. (See: last will and testament, holographic will, testator, executor, probate, estate, guardian, codicil)

Copyright © 1981-2005 by Gerald N. Hill and Kathleen T. Hill. All Right reserved.

will

a legal document in which a person (the testator) directs how his property is to be distributed after his death. Such documents must be executed in due form and in the UK at least must be duly witnessed.

Collins Dictionary of Law © W.J. Stewart, 2006

WILL, criminal law. The power of the mind which directs the actions of a

man.

2. In criminal law it is necessary that there should be an act of the

will to commit a crime, for unless the act is wilful it is no offence.

3. It is the consent of the will which renders human actions

commendable or culpable, and where there is no win there can be no

transgression.

4. The defect or want of will may be classed as follows: 1. Natural, as

that of infancy. 2. Accidental; namely, 1st. Dementia. 2d. Casualty or

chance. 3d. Ignorance. (q.v.) 3. Civil; namely, 1st. Civil subjection. 2d.

Compulsion. 3d. Necessity. 4th. Well-grounded fear. Hale’s P. C. c. 2 Hawk.

P. C. book 1, c. 1.

A Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States. By John Bouvier. Published 1856.

(A) Short for last will and testament and is the document in which a person specifies what is to be done with his or her property upon death and who shall be named executor to ensure the proper distribution occurs. (B) criminal law. The power of the mind which directs the actions of a man. 2. In criminal law it is necessary that there should be an act of the will to commit a crime, for unless the act is willful it is no offence. 3. It is the consent of the will which renders human actions commendable or culpable, and where there is no win there can be no transgression. 4. The defect or want of will may be classed as follows: 1. Natural, as that of infancy. 2. Accidental; namely, 1st. Dementia. 2d. Casualty or chance. 3d. Ignorance. 3. Civil; namely, 1st. Civil subjection. 2d. Compulsion. 3d. Necessity. 4th. Well-grounded fear.

Law Dictionary – Alternative Legal Definition

A will is the legal expression of a man’s wishes as to the disposition of his property after his death. An instrument in writing, executed in form of law, by which a person makes a disposition of his property, to take effect after his death. Except where it would be inconsistent with the manifest intent of the legislature, the word “will” shall extend to a testament, and to a codicil, and to an appointment by will, or by writing in the nature of a will, in exercise of a power; and also to any other testamentary disposition. Code Va. 1887,

Noun

In her will, she asked that her money be donated to the church.

He made a will only days before his death.

He has no will of his own.

a government that reflects the will of the people

Recent Examples on the Web

If TimberTech’s eye for aesthetics hasn’t won you over, the brand’s commitment to sustainability will.

—

Her lawyer, Fernando Soto, made the preliminary announcement that Kodama, who died of breast cancer in Buenos Aires, didn’t have a will.

—

These redistributionists are acting as if unrealized capital gains are stored in vaults like gold and can be collected at Congress’s will.

—

From that foundation of strength, his government has moved to bend the judicial system to its will through pressure and enticements, while also wielding it as a weapon with tactics that trap opponents in clogged courts.

—

Her background as a political operative is to her benefit — knowing how to bend laws and politicians to your will is part of the role.

—

Three onboard motors would allow the island to move locations at will.

—

So there is no question that China could quietly force TikTok to bend to its will.

—

While a child is aware of the projection onto an inanimate toy and can engage or not engage in it at will, a robot that demands attention by playing off of our natural responses may cause a subconscious engagement that is less voluntary.

—

Barrett Hayton completely willed the puck into the net 44 seconds into the period to cut the lead to 4-2.

—

The junior recorded her eighth 20-point performance in an NCAA Tournament game, trying to will her team to back-to-back Final Four appearances with 27 points (8 of 19 shooting).

—

John Holcombe 1 of 4 Holcombe smells his late wife’s robe, willing her scent to return to the fabric.

—

The canine received his fortunes from the late German Countess Karlotta Leibenstein, who died in 1992 and willed her entire fortune to her beloved German shepherd — at that time, Gunther III.

—

Star of the game: Hill willed his team to the win.

—

He’s admitted to pushing past his car’s limit in hopes of willing himself to top-10s.

—

Antetokounmpo has won two regular-season MVPs, played through a severe leg injury and willed the Bucks to their first NBA title in 50 years in 2021 in one of the greatest stories in all of Wisconsin pro sports.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘will.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Definition of Main Clauses In A Will

These are the main clauses that a legal practitioner would expect to find in a will.

Definition of Proving The Will

This is a term used in wills and probate matters.

Definition of Taking Instructions On Making A Will

The solicitor’s responsibility is to take proper instructions from the client and carry them out.

Definition of Will

A person’s express intentions for disposing of their estate when they die.

Concept of Will

The following is an old definition of Will [1], a term which has several meanings:1. The faculty of the mind which makes choice between objects or ends; the power which directs action; inclination toward action; desire, purpose, consent, intention, volition. As employed in defining the crime of rape, is not construed as implying the faculty by which intelligent choice is made between objects, but as the synonym of “inclination” or “desire;” and in this sense is used with propriety in reference to the actions of persons of unsound mind. The technical phrase ” against the will ” charges violence, especially in the commission of such crimes as rape, and robbery from the person. ” Against consent ” expresses the idea with equal accuracy. In the case of robbery, the greatest degree of terror is not contemplated. See Violence. On the subject of ill-will, see Malice; as to estates at will, see Tenant, At will. Willful; willfully. In common par- lance “willful” means intentional, as distinguished from accidental or involuntary; in penal statutes it means with evil intent, with legal malice, without ground for believing the act to be lawful. The ordinary meaning of “willful,” in statutes, is not merely ” voluntary,” but with a bad purpose. ^ Sometimes it means little more than ” intentional” or “designed.” But that is not its ordinary signification in criminal and penal statutes; in them it most frequently conveys the idea of legal malice in greater or less degree – implies an evil intent without justifiable excuse. “Voluntary”is, therefore, a weaker word: it means simply “willing.” Doing or omitting to do a thing ” knowingly and willfully ” implies not only a knowledge of the thing, but a determination with a bad purpose to do it or to omit doing it. ” Willful,” frequently means more than merely ” intentional;” it sometimes implies perverseness, deliberate design, malice. ” Willfully,” in an indictment, implies that the act is done knowingly and of stubborn purpose, but not necessarily of malice. Referring to an act forbidden by law, means that the act must be done knowingly and intentionally – that with knowledge the will consented to, designed and directed the act. Only want or defect of will will pi’otect the doer of a forbidden act from the punishment annexed thereto. An involuntary act induces no guilt: the concurrence of the will, when it has its choice to do or to avoid an act, being the only thing that renders human action either praiseworthy or culpable. To make a crime complete there must be both a will and an act. As no temporal tribunal can search the heart or fathom the intentions of the mind, otherwise than as demonstrated by outward actions, it cannot punish what it cannot know. Hence, an overt act, some open evidence of an intended crime, is necessary to demonstrate depravity of will, before a man can be punished. . To constitute a crime against human laws, there must be a vicious will and an unlawful act consequent thereon. The will does not join with the act in three cases; (1) When there is a defect of understanding. Where there is no discernment there is no choice, and where no choice there is no act of the will, which is merely a determination of one’s choice to do or to abstain from doing a particular action. (2) Where there is understanding and will sufficient, but it is not called forth or exerted at the time the action is done; as, in cases of chance and ignorance. (3) When the action is constrained by outward force. Here the will disagrees as to the act which the person is obliged to perform. To the first class of cases are referred infancy, lunacy, and intoxication: to the second class, misfortune and ignorance; to the third class, compulsion or necessity, qqv. See Consent; Crime; Duress; Insanity; Intention; Knovtledge; Malice; Mind; Volo; Voluntary, 1. See also Good- will

Alternative Meaning

The legal declaration of a man’s inten- tion which he ” wills ” to be performed after his death. A disposition of real and personal property to take effect after the death of the testator. It expresses ” the will ” of the maker as to the direction his property shall take. A declaration of the mind, either by word or writing, in disposing of an estate; to take place after the death of the testator. An instrument in any form, if the obvious purpose is not to take place till after the death of the maker, operates as a will. The essence of the definition is, it is a disposition to take effect after death. The form is immaterial, if the substance is testamentary. An instrument by which a person makes a disposition of his property to take effect after his decease. A will is to be considered as the ” testament,” and the instrument. The testament is the result and effect in law of what is the will; that consists of all the parts, including a codicil. See further Testament. Whatever the form of the instrument, it it vests no present interest but only appoints what is to be done after the death of the maker, it is “testamentary.” If the intention is to convey a present estate, though the possession be postponed until after the death of the maker, the instrument is a ” deed; ” if an interest accruing after his death, it is a ” will.” If the disposition necessarily takes effect after the death of the maker, and that intention is clear, the instrument is a will, though the maker supposed it to be some other kind of a paper. If the Instrument is such that, upon delivery, interests vest, though to be enjoyed in possession in the future, or obligations are created which are enforce- able by the parties respectively, it is a contract inter vivos. An instrument in the form of a deed, signed, sealed, and delivered as such, but intended as a posthumous disposition of a maker’s property, is testamentary. Last will. The last will made. If two or more wills are in contemplation, this expression appropriately designates the one made after the other or others; otherwise, “last” is redundant, the word ” will ” alone fully expressing the idea. Niineupative will. Such will as depends upon merely oral evidence, being declared by the testator in extremis, before a sufficient number of witnesses, and after- ward reduced to writing. In early times, a will of chattels was good without writing – that being then little known. By the time of Henry Vm (1509), reading and writing had become so widely diffused that verbal or unwritten wills were confined to extreme cases. A case of perjury in con- nection with one will, as well as the opportunities for imposition they have ever afforded, caused nuncupative testaments to be placed under restrictions by the Statute of Frauds and Perjuries of 29 Chas. II (1678), c. 3. By 1 Vict. (1837), o. 26, §§ 9, 11,- preceded by 1 Will, IV (1830), c. 20 – the privilege was confined to soldiers ” in Actual military service ” and to mariners and seamen “at sea,” and extended to personalty only. These statutes, which, in substance, have been re-enacted here, receive a strict construction. The deceased must, furthermore, possess testamentary capacity, be in contemplation of death, without time to make a written will, and clearly evince, bywords or signs, an intention to dispose of his property. In England, while property continued in a man only for his life, wills were unknown. In more modern times, a person could dispose, of but one-third of his movables from his wife and children. No will of lands was permitted till 1541, and then of a portidh only. Indeed, wills and successions are creations of municipal law exclusively. Statute of wills. Statute of 32 Henry VIII (1541), c, 1, which enabled a person seised in fee-simple, socage tenure, to devise lands according to his own pleasure, except to a body corporate, and enabled a person holding lands in chivalry to devise two-thirds thereof. Later statutes, notably that of 7 Will. IV and 1 Vict. (1837), v;. 26, removed all restrictions. Our ancestors imported the English law on the subject of wills. Statutory regulafions, which are substantially alike in all the States, follow the English statutes, especially the Statute of Wills, so called. In New York, for example, every person must de- vise within the limitation of the Statute of Henry VIII, which became part of her law upon the adoption of the constitution of 1777, and, with modifications, re- mains so to this day. Power to dispose of property by will rests almost wholly upon statutes, the directions of which must be substantially complied with. No right is now more solemnly assured than the power to dispose of property by will as the owner pleases. This privilege creates an incentive to practice industry and frugality. The law secures equality of distribution when the owner dies intestate. The object of a will is to produce inequality either in the disposition or use. to make preferments; and, in this matter, a sane man, not unlawfully influenced, has a right to be governed by his prejudices. If a testator does not violate any principle of public policy, religion, or morahty, nor infringe upon any statute, he may make such disposition of his property as he sees proper. A will ” speaks from the death ” of the maker; that is, takes effect, as respects its dispositions, from the moment of his decease. The testator must be of years of discretion, now generally twenty-one, and of testamentary capacity. The draughting, signing, attesting, publishing, revoking, probating, etc., are matters also largely regulated by statutes, and explanatory decisions. An important general principle is that personalty is to be disposed of according to the law of the domicil of the testator, while realty must be disposed of according to the law in vogue at the place where the property is situated. A court of equity has power to correct mistakes in a will apparent upon the face of the instrument or made out by a due construction of its terms: the intention is the will. The intent of the testator is the cardinal rule by which to construe a will. If that intent can be clearly perceived, and is not contrary to a positive rale of law, it must prevail, although, in giving effect to it, some words should be rejected, or so restrained, as materially to change the literal meaning of the particular sentence. Wills being the least artificial of all instruments, often the productions of persons ignorant of the law and of the correct use of the language in which they, are written, are the least to be governed by the settled use of technical legal terms. It may well be doubted if any other source of enlightenment is of much assistance than the application of natural reason to the language of the instrument under the light thrown upon the intent of the testator by the extrinsic circumstances surrounding the execution, and connecting the parties and the bequests and devises with the testator and with the instrument itself. When interpreting a will, the attending circurastances of the testator, such as the conditions of his family, the amount and character of his property, are to be considered. The interpreter is to place himself in the position occupied by the testator when he made his will, and from that standpoint discover what was intended. tiittle aid is to be derived from a resort to formal rules, or from a consideration of judicial determinations in cases apparently similar. It is a question in each case of the reasonable interpretation of the words of the particular will, with a view to ascertaining the testator’s intention. See further Administer, 4; After; Ambiguity; Attest; Bequest; Cancel; Codicil; Contest; Conversion; Cy Pres; Demonstratio; Descent; Description, 2; Desire; Devise; Donatio; Effects;Election, 2; Equally; Executor; First, 2; Heir; Holograph; Ignorance; Influence; Inherit; Inofficious; Insanity, 2 (5); Issue, 5; Item; Legacy; Lost, 2; Money; Mortmain; Mutilate, 2; Part, 1, Reasonable; Perpetuity, 2; Power, 2; Precatory; Presence; Probate; Property; Provided; Publication; Punctuation; Reading; Representative (1); Res, 2; Residue; Said; Script; Scrivener; Separate, 2; Sign; So; Sole: Subscriber, 2; Then; Trust; Umpire; When; Writing.

Resources

Notes and References

- Meaning of Will provided by the Anderson Dictionary of Law (1889)

It is very important to take note of the difference between will and shall in contracts, because they express different meanings or intentions. However, before looking at the legal field for the usage of will and shall, we can first see how they are generally used. The terms ‘Will’ and ‘Shall’ are two widely used grammar terms. Although their origins date back many centuries, today they are commonly used interchangeably. In fact, many people tend to substitute one term with the other leaving those attempting to spot the distinction between the two, confused. The term ‘Shall’ was traditionally used to refer to the compulsory performance of some duty or obligation. Indeed, conventional grammar books reveal that ‘Shall’, when used in the first person, refers to a future event or action of some sort. However, when used in the second or third person, for example “He Shall” or “You Shall,” it denotes the performance of a promise or obligation. ‘Will,’ on the other hand, represented the reverse, in that when used in the first person it conveyed the performance of a promise, and when used in the second or third person, it implied a future event. Legally too, the terms pose a certain problem. Drafters of contracts or other legal documents spend a good deal of time mulling over which term to use in a certain clause in order to express the desired meaning or intention. Despite modern practices that use the terms synonymously, it is best to be aware of the subtle yet traditional distinction between the two.

What does Shall mean in Contracts?

The term ‘Shall’, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, means ‘has a duty to’. This definition illustrates a compulsory aspect associated with the duty specified. Thus, it is mandatory on the person or legal entity performing the duty. In contracts, the word ‘Shall’ is traditionally used to convey a duty or obligation in relation to the performance of the contract. Keep in mind that contracts are generally written in the third person. Therefore, the use of the word ‘Shall’, particularly in the third person, connotes a sort of command, thereby rendering the performance of an obligation or duty imperative. Simply put, ‘Shall’, particularly in contracts or legal documents such as statutes, generally refers to some form of compulsory action or the prohibition of a certain action. Commentators on the use of the word ‘Shall’ in contracts advise that it is best to use ‘Shall’ when imposing an obligation or duty on a particular person or entity that is party to the contract.

What does Will mean in Contracts?

It is not uncommon to notice the word ‘Will’ used in contracts also to impose obligations or duties. Traditionally, this is incorrect. The term ‘Will’ has been defined as expressing willingness, strong desire, determination or choice to do something. As mentioned before, contracts are written in the third person and the use of the word ‘Will’ in the third person denotes a sense of futurity or rather it refers to some future action or event. It has been widely noted that the use of the word ‘Will’ in contracts should only imply some future action or event and should not be used to create obligations, although this is not a strict rule. Thus, many drafters of contracts, for ease and clarity, use the word ‘Will’ to express a future event and contrastingly use the word ‘Shall’ to impose an obligation.

What is the difference between Will and Shall in Contracts?

• ‘Shall’ implies that a person has a duty or obligation to perform a certain action.

• ‘Will’ denotes a situation in which a person is willing, determined or has a strong desire to carry out a certain act.

• In contracts, ‘Shall’ is used to impose obligations or duties on the parties to the contract.

• ‘Will’, on the other hand, is used in contracts to refer to a future event or action. It does not impose an obligation or duty.

• The use of the term ‘Shall’ reflects the seriousness of the obligation or duty in that it is like a command, mandatory or imperative.

Images Courtesy:

- Contract by Gunnar Wrobel (CC BY-SA 2.0)

-

Defenition of the word will

- A person’s intent, volition, decision.

- A legal document that states who is to receive a person’s estate and assets after their death.

- The capability of conscious choice and decision and intention.

- leave or give by will; «My aunt bequeathed me all her jewelry»

- be going to; indicates futurity

- the capability of conscious choice and decision and intention: «the exercise of their volition we construe as revolt»- George Meredith

- a fixed and persistent intent or purpose; «where there’s a will there’s a way»

- determine by choice; «This action was willed and intended»

- decree or ordain; «God wills our existence»

- a legal document declaring a person’s wishes regarding the disposal of their property when they die

- have in mind; «I will take the exam tomorrow»

- the capability of conscious choice and decision and intention; «the exercise of their volition we construe as revolt»- George Meredith

- a fixed and persistent intent or purpose; «where there»s a will there»s a way»

- a legal document declaring a person»s wishes regarding the disposal of their property when they die

- leave or give by will after one»s death; «My aunt bequeathed me all her jewelry»; «My grandfather left me his entire estate»

- the capability of conscious choice and decision and intention

- a fixed and persistent intent or purpose

- determine by choice

- decree or ordain

- leave or give by will after one’s death

Synonyms for the word will

-

- bequeath

- bidding

- choice

- command

- desire

- determination

- force

- hope against hope

- leave

- long for

- motivation

- pray

- preference

- resolve

- self-control

- shall

- spirit

- strength of character

- testament

- volition

- want

- willpower

- wish

- yearn for

Similar words in the will

-

- will

- will’s

- willa

- willa’s

- willamette

- willamette’s

- willard

- willard’s

- willed

- willemstad

- willemstad’s

- willful

- willfully

- willfulness

- william

- william’s

- williams

- williamson

- williamson’s

- willie

- willie’s

- willies

- willing

- willinger

- willingest

- willingness

- willingness’s

- willis

- willow

- willow’s

- willowier

- willowiest

- willows

- willowy

- willpower

- willpower’s

- wills

- willy

- willy’s

Meronymys for the word will

-

- codicil

Hyponyms for the word will

-

- devise

- entail

- fee-tail

- intend

- mean

- New Testament

- Old Testament

- pass on

- remember

- think

- velleity

Hypernyms for the word will

-

- aim

- decide

- design

- determine

- faculty

- gift

- give

- instrument

- intent

- intention

- legal document

- legal instrument

- make up one’s mind

- mental faculty

- module

- official document

- ordain

- present

- purpose

- surname

Antonyms for the word will

-

- disinherit

- disown

See other words

-

- What is wife beater

- The definition of zax

- The interpretation of the word valediction

- What is meant by strana

- The lexical meaning widget

- The dictionary meaning of the word slivka

- The grammatical meaning of the word zarf

- Meaning of the word sklo

- Literal and figurative meaning of the word wide-awake

- The origin of the word willow

- Synonym for the word vlk

- Antonyms for the word wimp

- Homonyms for the word vodka

- Hyponyms for the word zenana

- Holonyms for the word vojna

- Hypernyms for the word wind instrument

- Proverbs and sayings for the word vzduch

- Translation of the word in other languages zerk

A will or testament is a legal document that expresses a person’s (testator) wishes as to how their property (estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person (executor) is to manage the property until its final distribution. For the distribution (devolution) of property not determined by a will, see inheritance and intestacy.

Though it has been thought a «will» historically applied only to real property, while «testament» applied only to personal property (thus giving rise to the popular title of the document as «last will and testament»), records show the terms have been used interchangeably.[1] Thus, the word «will» validly applies to both personal and real property. A will may also create a testamentary trust that is effective only after the death of the testator.

History[edit]

Throughout most of the world, the disposition of a dead person’s estate has been a matter of social custom. According to Plutarch, the written will was invented by Solon.[citation needed] Originally, it was a device intended solely for men who died without an heir.

The English phrase «will and testament» is derived from a period in English law when Old English and Law French were used side by side for maximum clarity. Other such legal doublets include «breaking and entering» and «peace and quiet».[2]

Freedom of disposition[edit]

The concept of the freedom of disposition by will, familiar as it is in modern England and the United States, both generally considered common law systems, is by no means universal. In fact, complete freedom is the exception rather than the rule.[3]: 654 Civil law systems often put restrictions on the possibilities of disposal; see for example «Forced heirship».

LGBT advocates have pointed to the inheritance rights of spouses as desirable for same-sex couples as well, through same-sex marriage or civil unions. Opponents of such advocacy rebut this claim by pointing to the ability of same-sex couples to disperse their assets by will. Historically, however, it was observed that «[e]ven if a same-sex partner executes a will, there is risk that the survivor will face prejudice in court when disgruntled heirs challenge the will»,[4] with courts being more willing to strike down wills leaving property to a same-sex partner on such grounds as incapacity or undue influence.[5][6]

Types of wills[edit]

Types of wills generally include:

- nuncupative (non-culpatory) – oral or dictated; often limited to sailors or military personnel.

- holographic will – written in the hand of the testator; in many jurisdictions, the signature and the material terms of the holographic will must be in the handwriting of the testator.

- self-proved – in solemn form with affidavits of subscribing witnesses to avoid probate.

- notarial – will in public form and prepared by a civil-law notary (civil-law jurisdictions and Louisiana, United States).

- mystic – sealed until death.

- serviceman’s will – will of person in active-duty military service and usually lacking certain formalities, particularly under English law.

- reciprocal/mirror/mutual/husband and wife wills – wills made by two or more parties (typically spouses) that make similar or identical provisions in favor of each other.

- joint will – similar to reciprocal wills but one instrument; has a binding effect on the surviving testator(s). First documented in English law in 1769.[7]

- unsolemn will – will in which the executor is unnamed.

- will in solemn form – signed by testator and witnesses.

Some jurisdictions recognize a holographic will, made out entirely in the testator’s own hand, or in some modern formulations, with material provisions in the testator’s hand. The distinctive feature of a holographic will is less that it is handwritten by the testator, and often that it need not be witnessed. In Louisiana this type of testament is called an olographic testament.[8] It must be entirely written, dated, and signed in the handwriting of the testator. Although the date may appear anywhere in the testament, the testator must sign the testament at the end of the testament. Any additions or corrections must also be entirely hand written to have effect.

In England, the formalities of wills are relaxed for soldiers who express their wishes on active service; any such will is known as a serviceman’s will. A minority of jurisdictions even recognize the validity of nuncupative wills (oral wills), particularly for military personnel or merchant sailors. However, there are often constraints on the disposition of property if such an oral will is used.

Terminology[edit]

- Administrator – person appointed or who petitions to administer an estate in an intestate succession. The antiquated English term of administratrix was used to refer to a female administrator but is generally no longer in standard legal usage.

- Apertura tabularum – in ancient law books, signifies the breaking open of a last will and testament.

- Beneficiary – anyone receiving a gift or benefiting from a trust

- Bequest – testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally other than money.

- Codicil – (1) amendment to a will; (2) a will that modifies or partially revokes an existing or earlier will.

- Decedent – the deceased (U.S. term)

- Demonstrative Legacy – a gift of a specific sum of money with a direction that is to be paid out of a particular fund.

- Descent – succession to real property.

- Devise – testamentary gift of real property.

- Devisee – beneficiary of real property under a will.

- Distribution – succession to personal property.

- Executor/executrix or personal representative [PR] – person named to administer the estate, generally subject to the supervision of the probate court, in accordance with the testator’s wishes in the will. In most cases, the testator will nominate an executor/PR in the will unless that person is unable or unwilling to serve. In some cases a literary executor may be appointed to manage a literary estate.

- Exordium clause is the first paragraph or sentence in a will and testament, in which the testator identifies himself or herself, states a legal domicile, and revokes any prior wills.

- Inheritor – a beneficiary in a succession, testate or intestate.

- Intestate – person who has not created a will, or who does not have a valid will at the time of death.

- Legacy – testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally of money. Note: historically, a legacy has referred to either a gift of real property or personal property.

- Legatee – beneficiary of personal property under a will, i.e., a person receiving a legacy.

- Probate – legal process of settling the estate of a deceased person.

- Residuary estate — the portion of an estate remaining after the payment of expenses and the distribution of specific bequests; this passes to the residuary legatees.

- Specific legacy (or specific bequest) – a testamentary gift of a precisely identifiable object.

- Testate – person who dies having created a will before death.

- Testator – person who executes or signs a will; that is, the person whose will it is. The antiquated English term of Testatrix was used to refer to a female.[9]

- Trustee – a person who has the duty under a will trust to ensure that the rights of the beneficiaries are upheld.

Requirements for creation[edit]

Any person over the age of majority and having «testamentary capacity» (i.e., generally, being of sound mind) can make a will, with or without the aid of a lawyer.

Content of the will[edit]

Required content varies, depending on the jurisdiction, but generally includes the following:

- The testator must clearly identify themselves as the maker of the will, and that a will is being made; this is commonly called «publication» of the will, and is typically satisfied by the words «last will and testament» on the face of the document.

- The testator should declare that he or she revokes all previous wills and codicils. Otherwise, a subsequent will revokes earlier wills and codicils only to the extent to which they are inconsistent. However, if a subsequent will is completely inconsistent with an earlier one, the earlier will is considered completely revoked by implication.

- The testator may demonstrate that he or she has the capacity to dispose of their property («sound mind»), and does so freely and willingly.

- The testator must sign and date the will, usually in the presence of at least two disinterested witnesses (persons who are not beneficiaries). There may be extra witnesses, these are called «supernumerary» witnesses, if there is a question as to an interested-party conflict. Some jurisdictions, notably Pennsylvania, have long abolished any requirement for witnesses. In the United States, Louisiana requires both attestation by two witnesses as well as notarization by a notary public. Holographic wills generally require no witnesses to be valid, but depending on the jurisdiction may need to be proved later as to the authenticity of the testator’s signature.

- If witnesses are designated to receive property under the will they are witnesses to, this has the effect, in many jurisdictions, of either (i) disallowing them to receive under the will, or (ii) invalidating their status as a witness. In a growing number of states in the United States, however, an interested party is only an improper witness as to the clauses that benefit him or her (for instance, in Illinois).

- The testator’s signature must be placed at the end of the will. If this is not observed, any text following the signature will be ignored, or the entire will may be invalidated if what comes after the signature is so material that ignoring it would defeat the testator’s intentions.

- One or more beneficiaries (devisees, legatees) must generally be clearly stated in the text, but some jurisdictions allow a valid will that merely revokes a previous will, revokes a disposition in a previous will, or names an executor.

A will may not include a requirement that an heir commit an illegal, immoral, or other act against public policy as a condition of receipt.

In community property jurisdictions, a will cannot be used to disinherit a surviving spouse, who is entitled to at least a portion of the testator’s estate. In the United States, children may be disinherited by a parent’s will, except in Louisiana, where a minimum share is guaranteed to surviving children except in specifically enumerated circumstances.[10] Many civil law countries follow a similar rule. In England and Wales from 1933 to 1975, a will could disinherit a spouse; however, since the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 such an attempt can be defeated by a court order if it leaves the surviving spouse (or other entitled dependent) without «reasonable financial provision».

Role of lawyers[edit]

There is no legal requirement that a will be drawn up by a lawyer, and some people may resist hiring a lawyer to draft a will.[11] People may draft a will with the assistance of a lawyer, use a software product[12] or will form, or write their wishes entirely on their own. Some lawyers offer educational classes for people who want to write their own will.[13]

When obtained from a lawyer, a will may come as part of an estate planning package that includes other instruments, such as a living trust.[14] A will that is drafted by a lawyer should avoid possible technical mistakes that a layperson might make that could potentially invalidate part or all of a will.[15] While wills prepared by a lawyer may seem similar to each other, lawyers can customize the language of wills to meet the needs of specific clients.[16]

International wills[edit]

In 1973 an international convention, the Convention providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will,[17] was concluded in the context of UNIDROIT. The Convention provided for a universally recognised code of rules under which a will made anywhere, by any person of any nationality, would be valid and enforceable in every country that became a party to the Convention. These are known as «international wills». It is in force in Australia, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Canada (in 9 provinces, not Quebec), Croatia, Cyprus, Ecuador, France, Italy, Libya, Niger, Portugal and Slovenia. The Holy See, Iran, Laos, the Russian Federation, Sierra Leone, the United Kingdom, and the United States have signed but not ratified.[18] International wills are only valid where the convention applies. Although the U.S. has not ratified on behalf of any state, the Uniform law has been enacted in 23 states and the District of Columbia.[18]

For individuals who own assets in multiple countries and at least one of those countries are not a part of the Convention, it may be appropriate for the person to have multiple wills, one for each country.[18][19] In some nations, multiple wills may be useful to reduce or avoid taxes upon the estate and its assets.[20] Care must be taken to avoid accidental revocation of prior wills, conflicts between the wills, to anticipate jurisdictional and choice of law issues that may arise during probate.[19]

Revocation[edit]

Methods and effect[edit]

Intentional physical destruction of a will by the testator will revoke it, through deliberately burning or tearing the physical document itself, or by striking out the signature. In most jurisdictions, partial revocation is allowed if only part of the text or a particular provision is crossed out. Other jurisdictions will either ignore the attempt or hold that the entire will was actually revoked. A testator may also be able to revoke by the physical act of another (as would be necessary if he or she is physically incapacitated), if this is done in their presence and in the presence of witnesses. Some jurisdictions may presume that a will has been destroyed if it had been last seen in the possession of the testator but is found mutilated or cannot be found after their death.

A will may also be revoked by the execution of a new will. Most wills contain stock language that expressly revokes any wills that came before them, because otherwise a court will normally still attempt to read the wills together to the extent they are consistent.

In some jurisdictions, the complete revocation of a will automatically revives the next-most recent will, while others hold that revocation leaves the testator with no will, so that their heirs will instead inherit by intestate succession.

In England and Wales, marriage will automatically revoke a will, for it is presumed that upon marriage a testator will want to review the will. A statement in a will that it is made in contemplation of forthcoming marriage to a named person will override this.

Divorce, conversely, will not revoke a will, but in many jurisdictions will have the effect that the former spouse is treated as if they had died before the testator and so will not benefit.

Where a will has been accidentally destroyed, on evidence that this is the case, a copy will or draft will may be admitted to probate.

Dependent relative revocation[edit]

Many jurisdictions exercise an equitable doctrine known as «dependent relative revocation» («DRR»). Under this doctrine, courts may disregard a revocation that was based on a mistake of law on the part of the testator as to the effect of the revocation. For example, if a testator mistakenly believes that an earlier will can be revived by the revocation of a later will, the court will ignore the later revocation if the later will comes closer to fulfilling the testator’s intent than not having a will at all. The doctrine also applies when a testator executes a second, or new will and revokes their old will under the (mistaken) belief that the new will would be valid. However, if for some reason the new will is not valid, a court may apply the doctrine to reinstate and probate the old will, if the court holds that the testator would prefer the old will to intestate succession.

Before applying the doctrine, courts may require (with rare exceptions) that there have been an alternative plan of disposition of the property. That is, after revoking the prior will, the testator could have made an alternative plan of disposition. Such a plan would show that the testator intended the revocation to result in the property going elsewhere, rather than just being a revoked disposition. Secondly, courts require either that the testator have recited their mistake in the terms of the revoking instrument, or that the mistake be established by clear and convincing evidence. For example, when the testator made the original revocation, he must have erroneously noted that he was revoking the gift «because the intended recipient has died» or «because I will enact a new will tomorrow».

DRR may be applied to restore a gift erroneously struck from a will if the intent of the testator was to enlarge that gift, but will not apply to restore such a gift if the intent of the testator was to revoke the gift in favor of another person. For example, suppose Tom has a will that bequeaths $5,000 to his secretary, Alice Johnson. If Tom crosses out that clause and writes «$7,000 to Alice Johnson» in the margin, but does not sign or date the writing in the margin, most states would find that Tom had revoked the earlier provision, but had not effectively amended his will to add the second; however, under DRR the revocation would be undone because Tom was acting under the mistaken belief that he could increase the gift to $7,000 by writing that in the margin. Therefore, Alice will get 5,000 dollars. However, the doctrine of relative revocation will not apply if the interlineation decreases the amount of the gift from the original provision (e.g., «$5,000 to Alice Johnson» is crossed out and replaced with «$3,000 to Alice Johnson» without Testator’s signature or the date in the margin; DRR does not apply and Alice Johnson will take nothing).

Similarly, if Tom crosses out that clause and writes in the margin «$5,000 to Betty Smith» without signing or dating the writing, the gift to Alice will be effectively revoked. In this case, it will not be restored under the doctrine of DRR because even though Tom was mistaken about the effectiveness of the gift to Betty, that mistake does not affect Tom’s intent to revoke the gift to Alice. Because the gift to Betty will be invalid for lack of proper execution, that $5,000 will go to Tom’s residuary estate.

Election against the will[edit]

Also referred to as «electing to take against the will». In the United States, many states have probate statutes that permit the surviving spouse of the decedent to choose to receive a particular share of deceased spouse’s estate in lieu of receiving the specified share left to him or her under the deceased spouse’s will. As a simple example, under Iowa law (see Code of Iowa Section 633.238 (2005) Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine), the deceased spouse leaves a will which expressly devises the marital home to someone other than the surviving spouse. The surviving spouse may elect, contrary to the intent of the will, to live in the home for the remainder of his/her lifetime. This is called a «life estate» and terminates immediately upon the surviving spouse’s death.

The historical and social policy purposes of such statutes are to assure that the surviving spouse receives a statutorily set minimum amount of property from the decedent. Historically, these statutes were enacted to prevent the deceased spouse from leaving the survivor destitute, thereby shifting the burden of care to the social welfare system.

In New York, a surviving spouse is entitled to one-third of her deceased spouse’s estate. The decedent’s debts, administrative expenses and reasonable funeral expenses are paid prior to the calculation of the spousal elective share. The elective share is calculated through the «net estate». The net estate is inclusive of property that passed by the laws of intestacy, testamentary property, and testamentary substitutes, as enumerated in EPTL 5-1.1-A. New York’s classification of testamentary substitutes that are included in the net estate make it challenging for a deceased spouse to disinherit their surviving spouse.

Notable wills[edit]

In antiquity, Julius Caesar’s will, which named his grand-nephew Octavian as his adopted son and heir, funded and legitimized Octavian’s rise to political power in the late Republic; it provided him the resources necessary to win the civil wars against the «Liberators» and Antony and to establish the Roman Empire under the name Augustus. Antony’s officiating at the public reading of the will led to a riot and moved public opinion against Caesar’s assassins. Octavian’s illegal publication of Antony’s sealed will was an important factor in removing his support within Rome, as it described his wish to be buried in Alexandria beside the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

In the modern era, the Thellusson v Woodford will case led to British legislation against the accumulation of money for later distribution and was fictionalized as Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. The Nobel Prizes were established by Alfred Nobel’s will. Charles Vance Millar’s will provoked the Great Stork Derby, as he successfully bequeathed the bulk of his estate to the Toronto-area woman who had the greatest number of children in the ten years after his death. (The prize was divided among four women who had nine, with smaller payments made to women who had borne 10 children but lost some to miscarriage. Another woman who bore ten children was disqualified, for several were illegitimate.)

The longest known legal will is that of Englishwoman Frederica Evelyn Stilwell Cook. Probated in 1925, it was 1,066 pages, and had to be bound in four volumes; her estate was worth $100,000. The shortest known legal wills are those of Bimla Rishi of Delhi, India («all to son») and Karl Tausch of Hesse, Germany, («all to wife») both containing only two words in the language they were written in (Hindi and Czech, respectively).[21] The shortest will is of Shripad Krishnarao Vaidya of Nagpur, Maharashtra, consisting of five letters («HEIR’S»).[22][23]

An unusual holographic will, accepted into probate as a valid one, came out of an accident. On 8 June 1948 in Saskatchewan, Canada, a farmer named Cecil George Harris became trapped under his own tractor. Thinking he would not survive (though found alive later, he died of his injuries in hospital), Harris carved a will into the tractor’s fender, which read:

In case I die in this mess I leave all to the wife. Cecil Geo. Harris.

The fender was probated and stood as his will. The fender is currently on display at the law library of the University of Saskatchewan College of Law.[24]

Probate[edit]

After the testator has died, an application for probate may be made in a court with probate jurisdiction to determine the validity of the will or wills that the testator may have created, i.e., which will satisfy the legal requirements, and to appoint an executor. In most cases, during probate, at least one witness is called upon to testify or sign a «proof of witness» affidavit. In some jurisdictions, however, statutes may provide requirements for a «self-proving» will (must be met during the execution of the will), in which case witness testimony may be forgone during probate. Often there is a time limit, usually 30 days, within which a will must be admitted to probate. In some jurisdictions, only an original will may be admitted to probate—even the most accurate photocopy will not suffice.[citation needed] Some jurisdictions will admit a copy of a will if the original was lost or accidentally destroyed and the validity of the copy can be proved to the satisfaction of the court.[25]

If the will is ruled invalid in probate, then inheritance will occur under the laws of intestacy as if a will were never drafted.

See also[edit]

- Ademption

- Death and the Internet, including password vaults

- Ethical will

- Trust law

- Henson trust

- Totten trust

- Will Aid

- Will contest

- Power of attorney

References[edit]

- ^ Wills, Trusts, and Estates (Aspen, 7th Ed., 2005)

- ^ Freedman, Adam (2013). The party of the first part the curious world of legalese. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1466822573.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Will». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 654–658.

- ^ Eugene F. Scoles, Problems and Materials on Decedents’ Estates and Trusts (2000), p. 39.

- ^ Chuck Stewart, Homosexuality and the Law: A Dictionary (2001), p. 310.

- ^ See also, for example, In Re Kaufmann’s Will, 20 A.D.2d 464, 247 N.Y.S.2d 664 (1964), aff’d, 15 N.Y.2d 825, 257 N.Y.S.2d 941, 205 N.E.2d 864 (1965).

- ^ Repository Citation: Contracts Not to Revoke Joint or Mutual Wills, 15 William & Mary Law Review 144 (1973), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol15/iss1/7

- ^ Louisiana Civil Code Article 1575 http://legis.la.gov/lss/lss.asp?doc=108900/ Archived 2013-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Definition of TESTATRIX».

- ^ For example, if the child attempted to kill the parent.

- ^ «Steps to Create an Estate Plan — Consumer Reports». Consumer Reports. November 2013. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Hartman, Rachel (2019-11-06). «The Best Online Will Making Programs». U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ Ewoldt, John (2016-05-11). «Prince’s estate highlights the value of creating a will». Minneapolis Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul (2018-09-07). «Making Wills Easier and Cheaper With Do-It-Yourself Options». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Beck, Laura W.; Bartlett, Stefania L.; Nerney, Andrew M. «Wills: Connecticut» (PDF). Cummings & Lockwood, LLC. Practical Law. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Hill, Catey (2015-11-27). «Don’t buy legal documents online without reading this story». Market Watch. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ «Convention providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will (Washington, D.C., 1973)». www.unidroit.org. 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ a b c Eskin, Vicki; Driscoll, Bryan. «Estate Planning with Foreign Property». American BAR Association. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ a b Fry, Barry (2012). «Cross Border Estate Issues» (PDF). Advoc. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Popovic-Montag, Suzana; Hull, Ian M. (2 Oct 2015). «The Risks and Rewards of Multiple Wills». HuffPost Canada Business. Retrieved 7 June 2017.