LATIN

lat’-in:

Was the official language of the Roman Empire as Greek was that of commerce. In Palestine Aramaic was the vernacular in the rural districts and remoter towns, while in the leading towns both Greek and Aramaic were spoken. These facts furnish the explanation of the use of all three tongues in the inscription on the cross of Christ (Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19). Thus the charge was written in the legal language, and was technically regular as well as recognizable by all classes of the people. The term «Latin» occurs in the New Testament only in John 19:20, Rhomaisti, and in Luke 23:38, Rhomaikois (grammasin), according to Codices Sinaiticus, A, D, and N. It is probable that Tertullus made his plea against Paul before Felix (Acts 24) in Latin, though Greek was allowed in such provincial courts by grace of the judge. It is probable also that Paul knew and spoke Latin; compare W.M. Ramsay, Pauline and Other Studies, 1906, 65, and A. Souter, «Did Paul Speak Latin?» The Expositor, April, 1911. The vernacular Latin had its own history and development with great influence on the ecclesiastical terminology of the West. See W. Bury, «The Holy Latin Tongue,» Dublin Review, April, 1906, and Ronsch, Itala und Vulgata, 1874, 480 f. There is no doubt of the mutual influence of Greek and Latin on each other in the later centuries. See W. Schulze, Graeca Latina, 1891; Viereck, Sermo Graecus, 1888.

It is doubtful if the Latin syntax is clearly perceptible in the koine (see LANGUAGE OF THE NEW TESTAMENT).

Deissmann (Light from the Ancient East, 117 f) finds ergasian didomi (operam dare) in an xyrhynchus papyrus letter of the vulgar type from 2nd century BC (compare Luke 12:58). A lead tablet in Amorgus has krino to dikaion (compare Luke 12:57). The papyri (2nd century AD) give sunairo logon (compare Matthew 18:23 f). Moulton (Expositor, February, 1903, 115) shows that to hikanon poiein (satisfacere), is as old as Polybius. Even sumbouilion lambanien (concilium capere), may go with the rest like su opes (Matthew 27:4), for videris (Thayer). Moulton (Prol., 21) and Thumb (Griechische Sprache, 121) consider the whole matter of syntactical Latinisms in the New Testament inconclusive. But see also C. Wessely, «Die lateinischen Elemente in der Gracitat d. agypt. Papyrusurkunden,» Wien. Stud., 24; Laforcade. Influence du Latin sur le Grec. 83-158.

There are Latin words in the New Testament:

In particular Latin proper names like Aquila, Cornelius, Claudia, Clemens, Crescens, Crispus, Fortunatus, Julia, Junia, etc., even among the Christians in the New Testament besides Agrippa, Augustus, Caesar, Claudius, Felix, Festus, Gallio, Julius, etc.

Besides we find in the New Testament current Latin commercial, financial, and official terms like assarion (as), denarion (denarius), kenturion (centurio), kenos (census), kodrantes (quadrans), kolonia (colonia), koustodia (custodia), legeon (legio), lention (linteum), libertinos (libertinus), litra (litra), makellon (macellum), membrana (membrana), milion (mille), modios (modius), xestes (sextarius), praitorion (praetorium), sikarios (sicarius), simikinthion (semicinctium), soudarion (sudarium), spekoulator (speculator), taberna (taberna), titlos (titulus), phelones (paenula), phoron (forum), phragellion (flagellum), phragelloo (flagello), chartes (charta?), choros (chorus).

Then we meet such adjectives as Herodianoi, Philippesioi, Christianoi, which are made after the Latin model. Mark’s Gospel shows more of these Latin words outside of proper names (compare Romans 16), as is natural if his Gospel were indeed written in Rome.

See also LATIN VERSION, THE OLD.

LITERATURE.

Besides the literature already mentioned see Schurer, Jewish People in the Time of Christ, Div II, volume I, 43; Krauss, Griechische und lateinische Lehnworter im Talmud (1898, 1899); Hoole, Classical Element in the New Testament (1888); Jannaris, Historical Greek Grammar (1897); W. Schmid, Atticismus, etc. (1887-97); Kapp, Latinismis merito ac falso susceptis (1726); Georgi, De Latinismis N T (1733); Draeger, Historische Syntax der lat. Sprache (1878-81); Pfister, Vulgarlatein und Vulgargriechisch (Rh. Mus., 1912, 195-208).

A. T. Robertson

It is my understanding that the original text of the Bible is mostly in Hebrew and Greek. There are a few quotes from other languages, like “Mene mene tekel …” (language seems to be unclear) or Jesus’s “Eli, Eli, lama sabachtani” (Aramaic). But since the New Testament, at least, came into being in a world where the Romans had a word or two to say, I wondered if is there any Latin to be found.

I know, of course, that there are Latin names in the Bible, like Pontius Pilatus. But are there any other words or even sentences?

asked Sep 17, 2020 at 21:14

11

According to the study, «A Study of Latin Words in the Greek New Testament», by Esther Laverne Benjamin, there are about thirty Latin words transliterated into Greek in the New Testament. The majority of these are nouns. The study divides the words into the following categories:

- Words of Economic Significance — coins, weights and measures

- Words of Judicial Significance — such as σικάριος, φραγέλλιον

- Words of Military Significance — such as κεντυρίων, λεγιών

- Words of Political Significance — such as κολωνία, λιβερτίνος

- General — winds, articles of dress, commercial and social centers, and writing materials

answered Sep 18, 2020 at 13:07

Expedito BipesExpedito Bipes

10.6k2 gold badges28 silver badges49 bronze badges

2

I too am looking for a list of words used in the original manuscripts with Latin. This morning, in the NKJV study Bible from Nelson, I read the commentary on Mark 6:27; 37 where they mentioned two Latin words spekoulatora and denarii respectfully. These are their notes:

spekoulatora — an executioner. Herod dispatched an executioner. Here Mark uses a Latin word easily understood by his Roman readers

denarii — this is the plural word of denarius -a commonly used silver coin. It was the sum typically paid to a laborer for a days work.

If anyone else comes across a latin word list in the original manuscripts, please share

answered Nov 14, 2021 at 13:54

1

SOME IMPORTANT LATIN THEOLOGICAL TERMS

Curt Daniel

Biblia: Bible. Book. Biblia Sacra: Holy Bible. Vulgata: Vulgate (official Latin Bible). Vetus Testamentum: Old Testament. Novum Testamentum: New Testament.

Sola Scriptura: Scripture Alone. This was the fundamental point in dispute in the Protestant Reformation. It is taught in 2 Tim. 3:16-17; I Cor.4:6; Acts 17:11; Isa.8:20, etc.

Analogia Scripturae: The Analogy of Scripture. This is explained in the formula: “Scripturam ex Scriptura explicandam esse“, or “Scripture is to be explained by Scripture.” Related to this principle is the principle of Analogia Fide, or “Analogy of Faith.” That is, Biblical doctrines are to be interpreted in relation to the basic message of the Bible, the Gospel, the content of faith, often called The Faith. Cf.1 Cor.2:13, 15:1-4.

Testimonium Internum Spiritu Sanctu: The Internal Testimony of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit who inspired Scripture also authenticates and proves its divine origin through the Scripture itself. This is especially emphasized by Calvinists. Cf.Heb.10:15; I John 5:7-8.

Textus Receptus: Received Text. The Greek text first published by Erasmus, then with slight modifications by Stephanus, Beza and Elzivir, upon which the King James Version is based. It follows the vast majority of the Greek manuscripts, is much the same as the more recent Majority Text, as opposed to the editions based on a minority of manuscripts.

Deus: God. Corresponds to the Greek word THEOS. Deus est: God is. Deus Absconditus: The Hidden God. Deus Revelatus: The Revealed God.Verbum Dei: Word of God. Lux Dei: Light of God. Vox Dei: Voice of God. Imago Dei: Image of God. The word “deity” comes from Deus.

Trinitas: Trinity. Probably coined by Tertullian by combining the Latin words for three and one. The word is not found in Scripture, but the doctrine is (Matt. 28:19).

Actus Purus: Pure Actuality. Refers to God as to His perfect self-existence. Creation is potential or derivative in being, or growing in being once created. God is perfect being.

Sensus Divinitas: The sense of divinity. All men know that God exists (Rom. 1:18-21). Thus, there are no real atheists. Especially emphasized by Calvinists, particularly those of the Presuppositionalist school of apologetics, such as Cornelius Van Til.

Theologica: Theology. Based on the Greek words for God and science. Summa Theologica: Sum of Theology. This was the title of the famous systematic theology by Thomas Aquinas.

Loci Communes: Common Places. This was the usual term for systematic theology by the Lutherans, such as the important one by Philip Melanchthon. It refers to the collection of Scripture texts according to subject. Locus Classicus: Classic Place. The major Bible text on a subject.

Institutio Christianae Religionis: Institutes of the Christian Religion. Calvin’s main work.

Summum Bonum: Chief Good. God is the first cause of all, and the final goal. And so, the chief end for which all things were created is the glory of God.

Analogia Entis: Analogy of Being. The error that says that God and Man both share the same kind of being, differing in quantity but not in quality. Basically pantheistic.

Protoevangelium : The First Gospel. The first revelation of the Gospel was Gen. 3:15.

Foedus: Covenant. Federal Theology (or Federalism) is Covenant Theology.

Lex: Law. Lex Dei: Law of God. Lex Naturalis: Natural Law, revealed in Creation (Rom.1:18-23, 2:14-15). Lex Mosaica: Law of Moses. Lex Ceremonialis: Ceremonial Law. The temporary and symbolic laws of Moses, replaced by baptism and communion (Col. 2:16-17). Lex Moralis: Moral Law, God’s fundamental, unchangeable Law, in force in both testaments. Lex Talionis: Law of Retribution (or retaliation). An eye for an eye, the punishment fits the crime, you reap what you sow. Lex Rex: Law and the King, or Law of the King. Title of important book by Samuel Rutherford on the use of Biblical civil law today.

Creatio ex Nihilo: Creation out of nothing. God created merely by speaking it into existence.

Infralapsus: Infralapsarian. God first ordained the Fall and then elected men in the logical order of the eternal decrees. Supralapsus: Supralapsarian. God first elected some and rejected others before He ordained the Fall. Lapsus: Fall.

Ordo Salutis: Order of Salvation. Reformed theologians coined the term. Armilla Aurea, or Golden Chain, to relate the elements and stages of salvation according to Rom.8:29-30, etc.

Sola Gratia: Grace alone. Grace-faith-justification-works, not grace-faith-works-justification.

Sola Fide: Faith alone. Bona fide: Good faith. Credo: I believe. Notitia: Knowledge, the first element of saving faith. Assensus: Assent, the second element of faith. Fiducia: Trust, the third element of faith.

Simul lustus et Peccator: Simultaneously just and sinful. When we are justified, we are still sinful of ourselves. Even though our natures are changed in regeneration, there is still indwelling sin within us. The basis of our acceptance with God is not our changed nature, but rather the righteousness of Christ. His righteousness is thus Iustia Alienum, an alien righteousness – it is inherent in Christ, but not in us. In justification, God imputes or accounts this to us. It is then Iustia Imputata, imputed righteousness.

Articulus Stantis et Cadentis Ecclesiae: The article by which the Church stands and falls. Luther’s statement concerning justification of the imputed righteousness of Christ by faith alone, rejected by Roman Catholicism.

Solo Christo: Christ alone. Not Christ and priests, pastors, parents, or anyone else.

Extra Calvinisticum: The Calvinistic Extra. The Lutherans believed in the ubiquity (omnipresence) of Christ’s human body and nature, whereas the Calvinists have believed the historic view that Christ’s human body-and-soul is not infinite or omnipresent, but is only now at the right hand of the Father. Calvinists hold to the principle Finitum non Capax Infiniti, or the finite is not capable of the infinite (the finite human nature of Christ is not capable of containing His infinite divine nature in its entirety).Thus, ever since the Incarnation, there is still infinite deity beyond Christ’s human nature. The beyond is “extra” or outside, infinite.

Corpus Christi: The Body of Christ. Hoc est Corpus Meum: This is My Body.

Sacramentum: Sacrament. Catholicism believes the sacraments are magical instruments which actually and physically confer grace. Their principle is Ex Opere Operato, or out of the work worked. Do something or receive a physical sacrament, and grace is automatically given. True Protestants, however, rightly reject this and take the word sacramentum to mean mystery, a symbolic ordinance in which grace is given through the Word of God.

Papa: Pope, father. Catholicism says he is infallible when he pronounces a truth as dogma when he speaks Ex Cathedra, from the chair (of Peter). This contradicts Sola Scriptura.

Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salus: Outside the Church there is no salvation. The Catholic heresy that there is no salvation outside Catholicism. Protestants believe rather that salvation is not given through a Church but through Christ. There are true believers in many churches, but not outside Biblical Christianity or out of the Body of Christ.

Reformata sed Semper Reformanda: Reformed and always reforming. The Protestant principle that the Church should always be striving to conform to Scripture. So should Christians.

Posse non Peccare: Able not to sin. Adam’s state before the Fall, and in another way also ours after we are saved. Non Posse non Peccare: Not able not to sin. Total inability to obey God or resist sinning. Unregenerate Man. Non Posse Peccare: Not able to sin. In one sense, God alone is unable to sin, being intrinsically holy. In another sense, the elect will be unable to sin when they are perfected in Heaven (Heb. 12:23; Eph. 1:4).

Soli Deo Gloria: To God alone be the glory. Gloria in Excelsis Deo: Glory to God in the highest.

For full definitions of these and many more, see Richard A. Muller, Dictionary of Latin and Greek Theological Terms (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1985).

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Bible translations into Latin date back to classical antiquity.

Latin translations of the Bible were used in the Western part of the former Roman Empire until the Reformation. Those translations are still used along with translations from Latin into the vernacular within the Roman Catholic Church.

Pre-Christian Latin translations[edit]

The large Jewish diaspora in the Second Temple period made use of vernacular translations of the Hebrew Bible, including the Aramaic Targum and Greek Septuagint. Though there is no certain evidence of a pre-Christian Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible, some scholars have suggested that Jewish congregations in Rome and the Western part of the Roman Empire may have used Latin translations of fragments of the Hebrew Bible.[1]

Early Christian and medieval Latin translations[edit]

Early Latin versions are divided into Vetus Latina and Vulgate. Vetus Latina manuscripts, also called Old Latin or Itala, are so called not because they are written in Old Latin (i.e. Latin prior to 75 BC), but because they are the oldest versions of the New Testament in Latin.[citation needed]

Unlike the Vulgate, the Vetus Latina tradition reflects numerous distinct, similar, and not entirely independent translations of various New Testament texts, extending back to the time of the original Greek autographs.[2]

In 382 CE, Jerome began a revision of the existing Vetus Latina Gospels into contemporary Latin, corrected against manuscripts in the original Greek.[3] Acts, Pauline epistles, Catholic epistles and the Apocalypse are Vetus Latina considered as being made by Pelagian groups or by Rufinus the Syrian.[4] Those texts and others are known as the Vulgate,[5] a compound text that is not entirely Jerome’s work.[6]

The Vetus Latina, «Old Latin»[edit]

The earliest known translations into Latin consist of a number of piecework translations during the early Church period. Collectively, these versions are known as the Vetus Latina and closely follow the Greek Septuagint. The Septuagint was the usual source for these anonymous translators, and they reproduce its variations from the Hebrew Masoretic Text. They were never rendered independently from the Hebrew or Greek; they vary widely in readability and quality, and contain many solecisms in idiom, some by the translators themselves, others from literally translating Greek language idioms into Latin.[7]

The Biblia Vulgata, «Common Bible»[edit]

Earlier translations progressively replaced by Jerome’s Vulgate version of the Bible.

Apart from full Old Testaments, there are more versions of the Psalms only, three of them by Jerome, one from the Hexapla, and one from the Hebrew. Other main versions include the Versio ambrosiana («Ambrosian version») and the Versio Piana («version of Pius» ). See the main Vulgate article for a comparison of Psalm 94.

Early modern Latin versions[edit]

Some printed Latin translations were produced by early 16th-century scholars such as Erasmus, derived from his Greek printed version, the Novum Instrumentum omne, the first published example of the Textus Receptus. The Complutensian Polyglot Bible followed shortly after.

In 1527, Xanthus Pagninus produced his Veteris et Novi Testamenti nova translatio, notable for its literal rendering of the Hebrew. This version was also the first to introduce verse numbers in the New Testament, although the system used here did not become widely adopted; the system used in Robertus Stephanus’s Vulgate would later become the standard for dividing the New Testament.[8]

Reformation-era Protestant Latin translations[edit]

During the Protestant Reformation, several new Latin translations were produced:

- Sebastian Münster produced a new Latin version of the Old Testament, and gave an impetus to Old Testament study at the time.[9]

- Theodore Beza prepared a Latin translation for his new edition of the Greek New Testament.[10]

- Sebastian Castellio produced a version [Wikidata] in elegant Ciceronian Latin. It was published in 1551.[11][12][13]

- Immanuel Tremellius, together with Franciscus Junius (the elder), published a Latin version of the Old Testament (complete with the deuterocanonical books), which became famous among Protestants.[14] Later editions of their version were accompanied by the Latin version of the Greek New Testament by Beza, and influenced the KJV translators.[15]

- Sebastian Schmidt (1617–1696) a Lutheran theologian and Bible translator. Published the Biblia Sacra sive Testamentum Vetus et Novum ex linguis originalibus in linguam Latinam translatum, in Strasbourg (Argentina) in 1696.[citation needed]

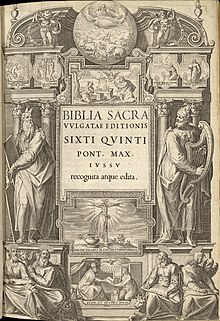

Sixto-Clementine Vulgate[edit]

The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate or Clementine Vulgate (Latin: Vulgata Clementina) is the edition promulgated in 1592 by Pope Clement VIII of the Vulgate—a 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible that was written largely by Jerome. It was the second edition of the Vulgate to be authorised by the Catholic Church, the first being the Sixtine Vulgate. The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate was used officially in the Catholic Church until 1979, when the Nova Vulgata was promulgated by Pope John Paul II.

The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate is a revision of the Sixtine Vulgate; the latter had been published two years earlier under Sixtus V. Nine days after the death of Sixtus V, who had issued the Sixtine Vulgate, the College of Cardinals suspended the sale of the Sixtine Vulgate and later ordered the destruction of the copies. Thereafter, two commissions under Gregory XIV were in charge of the revision of the Sixtine Vulgate. In 1592, Clement VIII, arguing printing errors in the Sixtine Vulgate, recalled all copies of the Sixtine Vulgate still in circulation; some suspect his decision was in fact due to the influence of the Jesuits. In the same year, a revised edition of the Sixtine Vulgate was published and promulgated by Clement VIII; this edition is known as the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, or Clementine Vulgate.

Metrical translations of the Psalms (16th c.)[edit]

Metrical Latin Bible translations are primarily Psalm paraphrases, or paraphrases of Song of Songs, Lamentations,[16] in Latin verse which appeared in the 16th century, then abruptly disappeared.[17][18][19]

Nova Vulgata[edit]

In 1907 Pope Pius X proposed that the Latin text of the Vulgate be recovered using the principles of textual criticism as a basis for a new official translation of the Bible into Latin.[20] This revision ultimately led to the Nova Vulgata issued by Pope John Paul II in 1979.[21]

Comparison of John 3:16 in different Latin versions[edit]

| Translation | John 3:16 |

|---|---|

| Vulgate | Sic enim dilexit Deus mundum, ut Filium suum unigenitum daret, ut omnis qui credit in eum non pereat, sed habeat vitam æternam. |

| Theodore Beza | Ita enim Deus dilexit mundum, ut Filium suum unigenitum illum dederit, ut quisquis credit in eum, non pereat, sed habeat vitam æternam. |

| Sebastian Castellio | Sic enim amavit Deus mundum, ut filium suum unicum dederit, ut quisquis in eum credat, non pereat, sed vitam obtineat sempiternam. |

| Neo-Vulgate | Sic enim dilexit Deus mundum, ut Filium suum unigenitum daret, ut omnis, qui credit in eum, non pereat, sed habeat vitam aeternam. |

Notes[edit]

- ^ This frontispiece is reproduced from the Sixtine Vulgate.

References[edit]

- ^ Michael E. Stone The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud: (2006) chapter 9 (“The Latin Translations”) by Benjamin Kedar «Traces of Jewish Traditions — Since all indications point to the fact that the OL is not the product of a single effort, the question arises whether strands of pristine translations, or at least early interpretative traditions can be detected in it.

A priori one may feel entitled to presume that Jewish Bible translations into Latin existed in relatively early times. It had been the custom of the Jews before the period under review to translate biblical books into their vernacular; such translations, sometimes made orally but frequently also written down, were needed for public reading in the synagogue and for the instruction of the young. Indeed, a number of scholars are inclined to believe that the OL has at its base pre-Christian translations made from the Hebrew. The proofs they adduce are, however, far from conclusive. Isolated linguistic or exegetic points of contact with Jewish idioms or targumic renderings do not necessarily prove a direct connection between the ol, or its early sections, and Jewish traditions.»

- ^ «There is no such thing as a uniform version of the New Testament in Latin prior to Jerome’s Vulgate». Elliott (1997:202).

- ^ Chapman, John (1922). «St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (I–II)». The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (93): 33–51. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.93.33. ISSN 0022-5185. Chapman, John (1923). «St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (III)». The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (95): 282–299. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.95.282. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ Canellis, Aline, ed. (2017). Jérôme : Préfaces aux livres de la Bible [Jerome : Preface to the books of the Bible] (in French). Abbeville: Éditions du Cerf. pp. 89–90, 217. ISBN 978-2-204-12618-2.

- ^ Canellis, Aline, ed. (2017). «Introduction : Du travail de Jérôme à la Vulgate» [Introduction: From Jerome’s work to the Vulgate]. Jérôme : Préfaces aux livres de la Bible [Jerome : Preface to the books of the Bible] (in French). Abbeville: Éditions du Cerf. p. 217. ISBN 978-2-204-12618-2.

- ^ Plater, William Edward; Henry Julian White (1926). A grammar of the Vulgate, being an introduction to the study of the latinity of the Vulgate Bible. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Helmut Köster Introduction to the New Testament 2 2000 p34 «An early witness for the African text of the Vetus Latina is Codex Palatinus 1 1 85 (siglum «e») from the 5th century, a gospel codex with readings closely related to the quotations in Cyprian and Augustine.»

- ^ Miller, Stephen M., Huber, Robert V. (2004). The Bible: A History. Good Books. p. 173. ISBN 1-56148-414-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ed. S. L. Greenslade The Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 3: The West from the Reformation to the Present Day 1975 p.70 “The hebraist Sebastian Münster of Basle departed from the extreme literalism of Pagnini in his own Latin version of the Old Testament: he left aside the New Testament. While it ‘did not depart by a nail’s breadth from the Hebrew verity’, this version was written in better Latin: it accompanied the Hebrew text of Münster referred to above. It appeared in 1535 in two folio volumes and was reprinted in quarto size in 1539 accompanied by the Complutensian version of the Apocrypha and by Erasmus’s Latin New Testament, and then again in its original form in 1546. This version gave an impetus to Old Testament study similar to that which Erasmus had given to the study of the New Testament…”

- ^ Ed. S. L. Greenslade The Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 3: The West from the Reformation to the Present Day 1975 p.62 “Calvin’s successor at Geneva, Théodore de Bèze (Beza), was the editor of the next important edition of the Greek New Testament, which appeared in 1565 (his own Latin version had been printed in 1557) and went through many editions in folio and octavo, accompanied in the larger size by his own Latin version; the Vulgate and full annotations are included.”

- ^ Buisson, Ferdinand (1892). «Les deux traductions de la Bible, en latin (1550) en français (1555)». Sébastien Castellion, sa vie et son oeuvre (1515-1563) : étude sur les origines du protestantisme libéral français (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette. p. 294. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ Gueunier, Nicole (2008). «Le Cantique des cantiques dans la Bible Latine de Castellion». In Gomez-Géraud, Marie-Christine (ed.). Biblia (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 148. ISBN 9782840505372.

- ^ Ed. S. L. Greenslade The Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 3: The West from the Reformation to the Present Day 1975 p.71-72

- ^ Ed. S. L. Greenslade The Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 3: The West from the Reformation to the Present Day 1975 p.72

- ^ Ed. S. L. Greenslade The Cambridge History of the Bible, Volume 3: The West from the Reformation to the Present Day 1975 p.167 “The latter, to which they probably resorted more than to any other single book, contained (in the later editions which they used) Tremellius’s Latin version of the Hebrew Old Testament with a commentary, Junius’s Latin of the Apocrypha, Tremellius’s Latin of the Syriac New Testament and Beza’s Latin of the Greek New Testament.”

- ^ Gaertner, JA (1956), «Latin verse translations of the psalms 1500–1620», Harvard Theological Review, 49 (4): 271–305, doi:10.1017/S0017816000028303, S2CID 161497305. Includes list: Latin metrical translations of books of the Bible other than the psalms by author and year of f1rst edition (1494–1621);

- ^ Gaertner, J. A Latin verse translations of the psalms 1500-1620. Harvard Theological Review 49 1956. «A good example of such a buried and forgotten literary genre is offered by the multitude of metrical Bible translations into Latin that appeared during the :6th century and after a hundred years ceased to exist as abruptly as it had…»

- ^ Grant, WL Neo-Latin verse translations of the Bible. Harvard Theological Review 52 1959

- ^ Hugues Vaganay, Les Traductions du psautier en vers latins au XVie siecle, Freiburg, 1898

- ^ Vulgate, Revision of, Catholic Encyclopedia article.

- ^ Novum Testamentum Latine, 1984, «Praefatio in editionem primam».

I’d love to know why Eugene Nida and/or Barclay Newman make no mention of the word rhomaisti from John 19:20 in A Translator’s Handbook on The Gospel of John. And after searching through many lexicons and commentaries I’ve found almost a complete lack of any useful information regarding how rhomasti is the word for Latin. Why isn’t it just «Latin» in Greek? Surely that word can be translated.

The truth is, the word «Latin» doesn’t appear in the Bible.

Also, the word rhome, which means, strength, vigor etc. Surely that was a Greek word in which the great city Rome was named after. Why do I only see this mythological explanation about Remus and Romulus? Why has no scholar or researcher explained this? I’ve looked everywhere.

The image shows a screenshot of Proverbs 6:8 from Swete’s LXX. It is also found in Rahlfs LXX. This is the only surviving usage of this word (ῥώμῃ) that I have found.

Helpful comments anyone?