Meta information

E-Conjugation (2)

Tenses

- Present

- Imperfect

- Perfect

- Pluperfect

- Future I

- Future II

- Indicative

- Subjunctive

- Active

- Passive

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ||

| 2. | ||

| 3. |

Future subjunctive forms do not exist. The subjunctive only exists in the four other tenses.

Infinitives

| Active | Passive | |

|---|---|---|

| Simult. (Present) | timere | timeri |

| Anter. (Perfect) | timuisse | — |

| Post. (Future) | — | — |

Participles

- Has No PPP

- PPA

- PFA

| Sg. | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | |||

| Gen. | |||

| Dat. | |||

| Acc. | |||

| Voc. | |||

| Abl. | |||

| Pl. | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

| Nom. | |||

| Gen. | |||

| Dat. | |||

| Acc. | |||

| Voc. | |||

| Abl. |

Gerund

Gerund forms only exist in singular.

| Sg. | Gerund |

|---|---|

| Nom. | timere |

| Gen. | timendi |

| Dat. | timendo |

| Acc. | timendum |

| Voc. | timere |

| Abl. | timendo |

Gerundive

- Singular

- Plural

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | |||

| Gen. | |||

| Dat. | |||

| Acc. | |||

| Voc. | |||

| Abl. |

Imperatives & Supina

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Imperative | time! | timete! |

| Supinum | |

|---|---|

| Type I | — |

| Type II | ū |

Example Sentences

nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas corpora; di, coeptis (nam vos mutastis et illas) adspirate meis primaque ab

~ Ovid, Metamorphoses I

est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae,

~ Caesar, Bellum Gallicum I

te studio grammaticae artis inductum, non solum versuum moderatione, quam pauci perviderunt, sed historiarum

~ Hyginus, De Astronomia I

fit, Maecenas, ut nemo, quam sibi sortem seu ratio dederit seu fors obiecerit, illa contentus vivat, laudet

~ Horace, Sermonum Liber I

Find more Latin text passages in the Latin is Simple Library

For Students

It’s guaranteed that you have or will run into some of these Latin terms in anything including the lightest reading. That’s because they’re everywhere. In newspapers, textbooks, manuals, et cetera. They are used in, inter alia, academic writing, text messaging, and, quite extensively, law documents. So, they are, ipso facto, very important to know. Ergo, we thought it’s a good idea to combine these Latin words and phrases in one place and explain what they mean so that when you run into some of them next time, you go like, ha! I have seen this word somewhere and I know what it means. So, let’s get down to it.

1. a priori

A belief or conclusion based on assumptions or reasoning of some sort rather than actual experience or empirical evidence. Before actually encountering, experiencing, or observing a fact.

2. a posteriori.

A fact, belief, or argument that is based on actual experience, experiment, or observation. After the fact.

3. ad astra.

To the stars.

4. ad hoc.

For a particular situation, without planning or consideration of some broader purpose or application.

5. ad hominem.

Directed to a particular person rather than generally, such as an attack on a person rather than a position they are espousing.

6. ad infinitum.

Repeat forever.

7. ad lib

Short for ad libitum. As you desire, at one’s pleasure. To speak or perform without preparation.

8. ad nauseam.

Repetition that has become annoying or tiresome.

9. affidavit.

He has sworn. Sworn statement.

10. alma mater.

Nourishing, kind, bounteous mother. School from which one graduated.

11. alias.

Also known as. Otherwise known as. Less commonly as the proper meaning of at another time, otherwise.

12. alibi.

In another place. Elsewhere. Reason one couldn’t have been in a location where an act was committed.

13. alter ego.

Other self. Another side of oneself.

14. A.D.

short for anno Domini. In the year of our Lord. Number of years since the birth of Jesus Christ.

15. a.m.

Short for ante meridiem. Before midday (noon.) Morning.

16. animus.

Spirit, mind, courage anger. Animosity. Intense opposition and ill will towards something, somebody, or some social group, commonly emotional, passionate, and mean-spirited. Hatred.

17. ante.

Before. Earlier. In a Supreme Court opinion, ante refers to an earlier page of the same opinion.

18. ante bellum.

Before the war.

19. ante mortem.

Before death.

20. bona fide.

Genuine. Real. With no intention to deceive.

21. c. / ca. / or cca.

Short for circa. Around. About. Approximately. Relative to a certain year.

22. carpe diem.

Seize the day or moment. Make the best of the present rather than delay or focus on the future.

23. caveat.

Warning, caution, disclaimer, or stipulation.

24. cf.

Short for confer. Compare to. In reference to, as a comparison.

25. cogito ergo sum.

I think, therefore I am — Descartes.

26. consensus.

Agreement. General or widespread agreement.

27. corpus.

Body, especially of written or textual matter such as books and papers.

28. curriculum.

Race. Course of a race. Path of a race. Subjects comprising a course of academic study.

29. CV

Short for curriculum vitae. The course of one’s life. Resume. List of significant academic and professional accomplishments, achievements, awards, education, and training.

30. de facto.

True or matter of fact as it is, regardless of intent, good reason, authority, or official reason for being such.

31. dictum.

Something said. Noteworthy, authoritative statement or principle. Common wisdom.

32. doctor.

Teacher. Learned person. Doctor.

33. ergo.

Therefore.

34. et al.

Short for et alia (neuter plural) or et alii (masculine plural) or et aliae (feminine plural). And others. And all of the others.

35. etc.

Short for et cetera.

36. e pluribus unum.

— Out of many, one — U.S. motto.

37. ex post.

After.

38. ex post facto.

After the fact.

39. e.g.

Short for exempli gratia. For the sake of example. For example.

40. ibid.

Short for ibidem or ib idem. In the same place. For a citation, indicates that it is from the same place as the preceding citation.

41. id.

short for idem. From the same source. For a citation, indicates that it is from the same source, but not from the same location in that source. In contrast to ibidem (ibid.) which means the same location or place in the same source as the preceding citation.

42. i.e.

Short for id est. That is. In other words.

43. in absentia.

Conducted in the absence of.

44. in camera.

In chambers. In private, commonly for legal proceedings, in the judge’s office (chambers.) before digital photography cameras were little “chambers.”

45. in situ.

In position. In place.

46. in toto.

As a whole. Entirely. All of it.

47. incognito.

Unknown. With one’s identity concealed. This is actually an Italian word, derived from the Latin word incognitus.

48. inter alia.

Among others. Among other things.

49. innuendo.

By nodding. Implied. Indirectly implied. Suggested. Oblique allusion.

50. intra.

Within. In a Supreme Court opinion, refers to a decision of another court, typically an appeals court.

51. ipso facto.

By that very fact or act. Therefore.

51. lingua franca.

Common language in a multi-language environment. Technically, it’s Italian.

52. magnum opus.

Great work. Greatest work. Masterpiece.

53. M.O.

short for modus operandi. Mode or method of operation. How you do things.

54. n.b. or N.B.

short for nota bene. Note well. It is worth noting that.

55. per capita.

Per person, for each person, of a population. Individually, but not for any particular person.

56. per cent.

or percent short for per centum. For each one hundred.

57. per se.

By itself. Intrinsically. Specifically.

58. p.m. / PM

short for post meridiem. After midday (noon.) Afternoon.

59. post.

After. Later. In a Supreme Court opinion, post refers to a later page of the same opinion.

60. post mortem.

After death.

61. prima facie.

On its face. Accepted on its face. Accepted as true based on initial impression. Accepted as true unless proven false.

62. PS.

short for post scriptum. Written after. After what has been written. In addition to what has been written. In addition.

63. quasi.

As if. As though. Resembling. Similar but not quite exactly the same. Having many but not all the features of.

64. quid pro quo.

This for that. An exchange of goods or services. A barter transaction. Any contractual transaction.

65. sic

or [sic]. So, this. The previous word should be taken literally even if it is not correct or appropriate.

66. stat.

or stat short for statim. Immediately. Now. without delay.

67. status quo.

The existing state of affairs. As it is. As things are.

68. stricto sensu

or sensu stricto. In a narrow, tight, or strict sense. Strictly speaking.

69. sui generis.

Of its own kind. Unique. Outside of existing categories. In law, outside of existing law.

70. supra.

Above. From the previous cited source.

71. tabula rasa.

Clean slate. Blank slate. Absence of any preconceived notions, ideas, goals, or purpose.

72. veni, vidi, vici.

I came, I saw, I conquered.

73. verbatim.

The same exact words. Literally.

74. vs.

short for versus. Against. In opposition to. As opposed to. In contrast to.

75. veto.

I forbid. Reject.

76. vice versa.

As well as the two immediately preceding subjects of a statement reversed. The same either way. The other way around.

77. viz.

short for videre licet or videlicet. Namely. That is.

You’ve reached the end of the article. Please share it if you think it deserves.

In medical prescriptions, up until almost the present day, doctors wrote b.i.d., t.i.d., etc. for bis in die, ter in die, etc., mean «two times a day», «three times a day», etc. This Latin grammar book by Leonhard Schmitz says that you can drop the preposition in, hence septies anno, «seven times a year». So, as you already noted, one way to render «a time» in the sense you have in mind is:

Use an adverbial number, like semel, bis, ter, quarter, quinquies, etc., and no noun at all.

That won’t work when you want to modify a single «time» with some notion of ordinal number, though, as in «the first time», «the second time», «the next time», or «the last time». Surely we need a noun for that. Well, Smith’s Copious and Critical English-Latin dictionary gives the adverb primum for «the first time». Also, saepius for «many times». The Vulgate provides some examples for other ordinal-ish concepts with «a time»:

Et ait «Implete quattuor hydrias aqua et fundite super holocaustum et super ligna.» Rursumque dixit «Etiam secundo hoc facite.» Qui cum fecissent et secundo, ait «Etiam tertio id ipsum facite.» Feceruntque et tertio.

And he said, «Fill four buckets with water and pour them over the burnt offering and over the wood.» And again he said, «And do it a second time.» When they had done it a second time, he said «And do the same thing a third time.» And they did it a third time. (Kings 18:34)

This construction occurs many «times» in the Vulgate. So:

You can get ordinal «times» by using the ordinal adjective substantively.

But look at Judges 20:30:

Et tertia vice sicut semel et bis contra Beniamin exercitum produxerunt.

And they drew up armies against Benjamin a third time, just as they had the first time and the second time.

It looks like we’ve found your noun—some of it, anyway:

(missing), vicis. (f.)

Even here, Latin seems to prefer to avoid it, saying the equivalent of «once and twice before» for «the first and second times». Indeed, vice has no nominative singular! It seems to want to be in the ablative—where it anchors an adverbial phrase. However, since it’s a noun, you can modify vice with anything you like. Here it is with alia, being used as a synonym for iterum:

Alia etiam vice Philisthim inruerunt et diffusi sunt in valle.

And another time the Philistines made a raid and spread themselves out in the valley. (Paralipomenon 14:13)

Deuteronomy 10:10 has «this time»:

Ego autem steti in monte sicut prius quadraginta diebus ac noctibus exaudivitque me Deus etiam hac vice et te perdere noluit.

And I stood on the mountain as before, forty days and nights, and God heard me this time also, and he would not destroy you.

Genesis 27:36:

At ille subiunxit iuste vocatum est nomen eius Iacob supplantavit enim me en altera vice. Primogenita mea ante tulit et nunc secundo subripuit benedictionem meam. Rursumque ad patrem «Numquid non reservasti» ait «et mihi benedictionem?»

But he added, «Rightly is his name called Jacob, for he hath supplanted me lo this second time. He took away my birthright before, and now this second time he hath stolen away my blessing. Again he said to his father, «Hast thou not reserved to me also a blessing?»

I understand altera vice here as an emphatic substitute for iterum. Notice that in the next sentence, secundo denotes the same time, the fact that it’s current emphasized with nunc.

So, while it sounds like vice is the word you’re looking for, providing a noun to explicitly denote one time/occurrence, enabling you to attach modifiers to it ad libitum, the main thing I’ve gotten from digging for information about this is a striking reminder that in Latin, parts of speech other than the noun play a more important role than in English, often making a noun inappropriate or unnecessary.

With that in mind, here’s my non-expert attempt to render your examples:

The first time is the easiest.

Facillime facere est prima vice.

The idea here is to avoid predicating anything directly about the first time (since there’s no nominative singular), and instead make the action the subject and put prima vice in an emphatic position. Better still is probably Facillime facere est primum or even Primo est facillimum, «It’s easiest the first time.»

I can’t remember the last time I was here.

Proxima vice hic adfuisse non reminiscor.

But that sounds very strange to me, more like «I can’t remember having been here on the last occurrence.» Probably better is Proximus hic adfuisse non reminiscor.

If you desperately need a noun in the nominative singular, you could reach for vicissitas or vicissitudo.

in: Character, Featured, Knowledge of Men

• May 10, 2019 • Last updated: September 3, 2021

What do great men like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Theodore Roosevelt all have in common?

They all were proficient in Latin.

From the Middle Ages until about the middle of the 20th century, Latin was a central part of a man’s schooling in the West. Along with logic and rhetoric, grammar (as Latin was then known) was included as part of the Trivium – the foundation of a medieval liberal arts education. From Latin, all scholarship flowed and it was truly the gateway to the life of the mind, as the bulk of scientific, religious, legal, and philosophical literature was written in the language until about the 16th century. To immerse oneself in classical and humanistic studies, Latin was a must.

Grammar schools in Europe and especially England during this time were Latin schools, and the first secondary school established in America by the Puritans was a Latin school as well. But beginning in the 14th century, writers started to use the vernacular in their works, which slowly chipped away at Latin’s central importance in education. This trend for English-language learning accelerated in the 19th century; schools shifted from turning out future clergymen to graduating businessmen who would take their place in an industrializing economy. An emphasis on the liberal arts slowly gave way to what was considered a more practical education in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

While Latin had been dying a slow death for hundreds of years, it still had a strong presence in schools until the middle of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1960s, college students demanded that the curriculum be more open, inclusive, and less Euro-centric. Among their suggested changes was eliminating Latin as a required course for all students. To quell student protests, universities began to slowly phase out the Latin requirement, and because colleges stopped requiring Latin, many high schools in America stopped offering Latin classes, too. Around the same time, the Catholic Church revised its liturgy and permitted priests to lead Mass in vernacular languages instead of Latin, thus eliminating one of the public’s last ties to the ancient language.

While it’s no longer a requirement for a man to know Latin to get ahead in life, it’s still a great subject to study. I had to take classes in Latin as part of my “Letters” major at the University of Oklahoma, and I really enjoyed it. Even if you’re well out of school yourself, there are a myriad of reasons why you should still consider obtaining at least a rudimentary knowledge of the language:

Knowing Latin can improve your English vocabulary. While English is a Germanic language, Latin has strongly influenced it. Most of our prefixes and some of the roots of common English words derive from Latin. By some estimates, 30% of English words derive from the ancient language. By knowing the meaning of these Latin words, if you chance to come across a word you’ve never seen before, you can make an educated guess at what it means. In fact, studies have found that high school students who studied Latin scored a mean of 647 on the SAT verbal exam, compared with the national average of 505.

Knowing Latin can improve your foreign language vocabulary. Much of the commonly spoken Romanic languages like Spanish, French, and Italian derived from Vulgar Latin. You’ll be surprised by the number of Romanic words that are pretty much the same as their Latin counterparts.

Many legal terms are in Latin. Nolo contendere. Mens rea. Caveat emptor. Do you know what those mean? They’re actually common legal terms. While strides have been made to translate legal writing into plain English, you’ll still see old Latin phrases thrown into legal contracts every now and then. To be an educated citizen and consumer, you need to know what these terms mean. If you plan on going to law school, I highly recommend boning up on Latin. You’ll run into it all the time, particularly when reading older case law.

Knowing Latin can give you more insight to history and literature. Latin was the lingua franca of the West for over a thousand years. Consequently, much of our history, science, and great literature was first recorded in Latin. Reading these classics in the original language can give you insights you otherwise may have missed by consuming it in English.

Moreover, modern writers (and by modern I mean beginning in the 17th century) often pepper their work with Latin words and phrases without offering a translation because they (reasonably) expect the reader to be familiar with it. This is true of great books from even just a few decades ago (seems much less common these days – which isn’t a hopeful commentary on the direction of the public’s literacy I would think). Not having a rudimentary knowledge of Latin will cause you to miss out on fully understanding what the writer meant to convey.

Below we’ve put together a list of Latin words and phrases to help pique your interest in learning this classical language. This list isn’t exhaustive by any stretch of the imagination. We’ve included some of the most common Latin words and phrases that you still see today, which are helpful to know in boosting your all-around cultural literacy. We’ve also included some particularly virile sayings, aphorisms, and mottos that can inspire greatness or remind us of important truths. Perhaps you’ll find a Latin phrase that you can adopt as your personal motto. Semper Virilis!

Latin Words and Phrases Every Man Should Know

- a posteriori — from the latter; knowledge or justification is dependent on experience or empirical evidence

- a priori — from what comes before; knowledge or justification is independent of experience

- acta non verba — deeds, not words

- ad hoc — to this — improvised or made up

- ad hominem — to the man; below-the-belt personal attack rather than a reasoned argument

- ad honorem — for honor

- ad infinitum — to infinity

- ad nauseam — used to describe an argument that has been taking place to the point of nausea

- ad victoriam — to victory; more commonly translated into “for victory,” this was a battle cry of the Romans

- alea iacta est — the die has been cast

- alias — at another time; an assumed name or pseudonym

- alibi — elsewhere

- alma mater — nourishing mother; used to denote one’s college/university

- amor patriae — love of one’s country

- amor vincit omnia — love conquers all

- annuit cœptis –He (God) nods at things being begun; or “he approves our undertakings,” motto on the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States and on the back of the United States one-dollar bill

- ante bellum — before the war; commonly used in the Southern United States as antebellum to refer to the period preceding the American Civil War

- ante meridiem — before noon; A.M., used in timekeeping

- aqua vitae — water of life; used to refer to various native distilled beverages, such as whisky (uisge beatha) in Scotland and Ireland, gin in Holland, and brandy (eau de vie) in France

- arte et marte — by skill and valour

- astra inclinant, sed non obligant — the stars incline us, they do not bind us; refers to the strength of free will over astrological determinism

- audemus jura nostra defendere — we dare to defend our rights; state motto of Alabama

- audere est facere — to dare is to do

- audio — I hear

- aurea mediocritas — golden mean; refers to the ethical goal of reaching a virtuous middle ground between two sinful extremes

- auribus teneo lupum — I hold a wolf by the ears; a common ancient proverb; indicates that one is in a dangerous situation where both holding on and letting go could be deadly; a modern version is, “to have a tiger by the tail”

- aut cum scuto aut in scuto — either with shield or on shield; do or die, “no retreat”; said by Spartan mothers to their sons as they departed for battle

- aut neca aut necare — either kill or be killed

- aut viam inveniam aut faciam — I will either find a way or make one; said by Hannibal, the great ancient military commander

- barba non facit philosophum — a beard doesn’t make one a philosopher

- bellum omnium contra omnes — war of all against all

- bis dat qui cito dat — he gives twice, who gives promptly; a gift given without hesitation is as good as two gifts

- bona fide — good faith

- bono malum superate — overcome evil with good

- carpe diem — seize the day

- caveat emptor — let the buyer beware; the purchaser is responsible for checking whether the goods suit his need

- circa — around, or approximately

- citius altius forties — faster, higher, stronger; modern Olympics motto

- cogito ergo sum — “I think therefore I am”; famous quote by Rene Descartes

- contemptus mundi/saeculi — scorn for the world/times; despising the secular world, the monk or philosopher’s rejection of a mundane life and worldly values

- corpus christi — body of Christ

- corruptissima re publica plurimae leges — when the republic is at its most corrupt the laws are most numerous; said by Tacitus

- creatio ex nihilo — creation out of nothing; a concept about creation, often used in a theological or philosophical context

- cura te ipsum — take care of your own self; an exhortation to physicians, or experts in general, to deal with their own problems before addressing those of others

- curriculum vitae — the course of one’s life; in business, a lengthened resume

- de facto — from the fact; distinguishing what’s supposed to be from what is reality

- deo volente — God willing

- deus ex machina — God out of a machine; a term meaning a conflict is resolved in improbable or implausible ways

- dictum factum — what is said is done

- disce quasi semper victurus vive quasi cras moriturus — learn as if you’re always going to live; live as if tomorrow you’re going to die

- discendo discimus — while teaching we learn

- docendo disco, scribendo cogito — I learn by teaching, think by writing

- ductus exemplo — leadership by example

- ducunt volentem fata, nolentem trahunt — the fates lead the willing and drag the unwilling; attributed to Lucius Annaeus Seneca

- dulce bellum inexpertis — war is sweet to the inexperienced

- dulce et decorum est pro patria mori — it is sweet and fitting to die for your country

- dulcius ex asperis — sweeter after difficulties

- e pluribus unum — out of many, one; on the U.S. seal, and was once the country’s de facto motto

- emeritus — veteran; retired from office

- ergo — therefore

- et alii — and others; abbreviated et al.

- et cetera — and the others

- et tu, Brute? — last words of Caesar after being murdered by friend Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, used today to convey utter betrayal

- ex animo — from the heart; thus, “sincerely”

- ex libris — from the library of; to mark books from a library

- ex nihilo — out of nothing

- ex post facto — from a thing done afterward; said of a law with retroactive effect

- faber est suae quisque fortunae — every man is the artisan of his own fortune; quote by Appius Claudius Caecus

- fac fortia et patere — do brave deeds and endure

- fac simile — make alike; origin of the word “fax”

- flectere si nequeo superos, acheronta movebo — if I cannot move heaven I will raise hell; from Virgil’s Aeneid

- fortes fortuna adiuvat — fortune favors the bold

- fortis in arduis — strong in difficulties

- gloria in excelsis Deo — glory to God in the highest

- habeas corpus — you should have the body; a legal term from the 14th century or earlier; commonly used as the general term for a prisoner’s right to challenge the legality of their detention

- habemus papam — we have a pope; used after a Catholic Church papal election to announce publicly a successful ballot to elect a new pope

- historia vitae magistra — history, the teacher of life; from Cicero; also “history is the mistress of life”

- hoc est bellum — this is war

- homo unius libri (timeo) — (I fear) a man of one book; attributed to Thomas Aquinas

- honor virtutis praemium — esteem is the reward of virtue

- hostis humani generis — enemy of the human race; Cicero defined pirates in Roman law as being enemies of humanity in general

- humilitas occidit superbiam — humility conquers pride

- igne natura renovatur integra — through fire, nature is reborn whole

- ignis aurum probat — fire tests gold; a phrase referring to the refining of character through difficult circumstances

- in absentia — in the absence

- in aqua sanitas — in water there is health

- in flagrante delicto — in flaming crime; caught red-handed, or in the act

- in memoriam — into the memory; more commonly “in memory of”

- in omnia paratus — ready for anything

- in situ — in position; something that exists in an original or natural state

- in toto — in all or entirely

- in umbra, igitur, pugnabimus — then we will fight in the shade; made famous by Spartans in the battle of Thermopylae and by the movie 300

- in utero — in the womb

- in vitro — in glass; biological process that occurs in the lab

- incepto ne desistam — may I not shrink from my purpose

- intelligenti pauca — few words suffice for he who understands

- invicta — unconquered

- invictus maneo — I remain unvanquished

- ipso facto — by the fact itself; something is true by its very nature

- labor omnia vincit — hard work conquers all

- laborare pugnare parati sumus — to work, (or) to fight; we are ready

- labore et honore — by labor and honor

- leges sine moribus vanae — laws without morals [are] vain

- lex parsimoniae — law of succinctness; also known as Occam’s Razor; the simplest explanation is usually the correct one

- lex talionis — the law of retaliation

- magna cum laude — with great praise

- magna est vis consuetudinis — great is the power of habit

- magnum opus — great work; said of someone’s masterpiece

- mala fide — in bad faith; said of an act done with knowledge of its illegality, or with intention to defraud or mislead someone; opposite of bona fide

- malum in se — wrong in itself; a legal term meaning that something is inherently wrong

- malum prohibitum — wrong due to being prohibited; a legal term meaning that something is only wrong because it is against the law

- mea culpa — my fault

- meliora — better things; carrying the connotation of “always better”

- memento mori — remember that [you will] die; was whispered by a servant into the ear of a victorious Roman general to check his pride as he paraded through cheering crowds after a victory; a genre of art meant to remind the viewer of the reality of his death

- memento vivere — remember to live

- memores acti prudentes future — mindful of what has been done, aware of what will be

- modus operandi — method of operating; abbreviated M.O.

- montani semper liberi — mountaineers [are] always free; state motto of West Virginia

- morior invictus — death before defeat

- morituri te salutant — those who are about to die salute you; popularized as a standard salute from gladiators to the emperor, but only recorded once in Roman history

- morte magis metuenda senectus — old age should rather be feared than death

- mulgere hircum — to milk a male goat; to attempt the impossible

- multa paucis — say much in few words

- nanos gigantum humeris insidentes — dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants; commonly known by the letters of Isaac Newton: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”

- nec aspera terrent — they don’t terrify the rough ones; frightened by no difficulties; less literally “difficulties be damned”

- nec temere nec timide — neither reckless nor timid

- nil volentibus arduum — nothing [is] arduous for the willing

- nolo contendere — I do not wish to contend; that is, “no contest”; a plea that can be entered on behalf of a defendant in a court that states that the accused doesn’t admit guilt, but will accept punishment for a crime

- non ducor, duco — I am not led; I lead

- non loqui sed facere — not talk but action

- non progredi est regredi — to not go forward is to go backward

- non scholae, sed vitae discimus — we learn not for school, but for life; from Seneca

- non sequitur — it does not follow; in general, a comment which is absurd due to not making sense in its context (rather than due to being inherently nonsensical or internally inconsistent); often used in humor

- non sum qualis eram — I am not such as I was; or “I am not the kind of person I once was”

- nosce te ipsum — know thyself; from Cicero

- novus ordo seclorum — new order of the ages; from Virgil; motto on the Great Seal of the United States

- nulla tenaci invia est via — for the tenacious, no road is impassable

- obliti privatorum, publica curate — forget private affairs, take care of public ones; Roman political saying which reminds that common good should be given priority over private matters for any person having a responsibility in the State

- panem et circenses — bread and circuses; originally described all that was needed for emperors to placate the Roman mob; today used to describe any entertainment used to distract public attention from more important matters

- para bellum — prepare for war; if you want peace, prepare for war; if a country is ready for war, its enemies are less likely to attack

- parvis imbutus tentabis grandia tutus — when you are steeped in little things, you shall safely attempt great things; sometimes translated as, “once you have accomplished small things, you may attempt great ones safely”

- pater familias — father of the family; the eldest male in a family

- pecunia, si uti scis, ancilla est; si nescis, domina — if you know how to use money, money is your slave; if you don’t, money is your master

- per angusta ad augusta — through difficulties to greatness

- per annum — by the year

- per capita — by the person

- per diem — by the day

- per se — through itself

- persona non grata — person not pleasing; an unwelcome, unwanted or undesirable person

- pollice verso — with a turned thumb; used by Roman crowds to pass judgment on a defeated gladiator

- post meridiem — after noon; P.M.; used in timekeeping

- post mortem — after death

- postscriptum — thing having been written afterward; in writing, abbreviated P.S.

- praemonitus praemunitus — forewarned is forearmed

- praesis ut prosis ne ut imperes — lead in order to serve, not in order to rule

- primus inter pares — first among equals; a title of the Roman Emperors

- pro bono — for the good; in business, refers to services rendered at no charge

- pro rata — for the rate

- quam bene vivas referre (or refert), non quam diu — it is how well you live that matters, not how long; from Seneca

- quasi — as if; as though

- qui totum vult totum perdit — he who wants everything loses everything; attributed to Seneca

- quid agis — what’s going on; what’s up, what’s happening, etc.

- quid pro quo — this for that; an exchange of value

- quidquid Latine dictum sit altum videtur — whatever has been said in Latin seems deep; or “anything said in Latin sounds profound”; a recent ironic Latin phrase to poke fun at people who seem to use Latin phrases and quotations only to make themselves sound more important or “educated”

- quis custodiet ipsos custodes? — who will guard the guards themselves?; commonly associated with Plato

- quorum — of whom; the number of members whose presence is required under the rules to make any given meeting constitutional

- requiescat in pace — let him rest in peace; abbreviated R.I.P.

- rigor mortis — stiffness of death

- scientia ac labore — knowledge through hard work

- scientia ipsa potentia est — knowledge itself is power

- semper anticus — always forward

- semper fidelis — always faithful; U.S. Marines motto

- semper fortis — always brave

- semper paratus — always prepared

- semper virilis — always virile

- si vales, valeo — when you are strong, I am strong

- si vis pacem, para bellum — if you want peace, prepare for war

- sic parvis magna — greatness from small beginnings — motto of Sir Frances Drake

- sic semper tyrannis — thus always to tyrants; attributed to Brutus at the time of Julius Caesar’s assassination, and to John Wilkes Booth at the time of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination; whether it was actually said at either of these events is disputed

- sic vita est — thus is life; the ancient version of “it is what it is”

- sola fide — by faith alone

- sola nobilitat virtus — virtue alone ennobles

- solvitur ambulando — it is solved by walking

- spes bona — good hope

- statim (stat) — immediately; medical shorthand

- status quo — the situation in which; current condition

- subpoena — under penalty

- sum quod eris — I am what you will be; a gravestone inscription to remind the reader of the inevitability of death

- summa cum laude — with highest praise

- summum bonum — the supreme good

- suum cuique — to each his own

- tabula rasa — scraped tablet; “blank slate”; John Locke used the term to describe the human mind at birth, before it had acquired any knowledge

- tempora heroic — Heroic Age

- tempus edax rerum — time, devourer of all things

- tempus fugit — time flees; commonly mistranslated “time flies”

- terra firma — firm ground

- terra incognita — unknown land; used on old maps to show unexplored areas

- vae victis — woe to the conquered

- vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas — vanity of vanities; everything [is] vanity; from the Bible (Ecclesiastes 1)

- veni vidi vici — I came, I saw, I conquered; famously said by Julius Caesar

- verbatim — repeat exactly

- veritas et aequitas — truth and equity

- versus — against

- veto — I forbid

- vice versa — to change or turn around

- vincit qui patitur — he conquers who endures

- vincit qui se vincit — he conquers who conquers himself

- vir prudens non contra ventum mingit — [a] wise man does not urinate [up] against the wind

- virile agitur — the manly thing is being done

- viriliter agite — act in a manly way

- viriliter agite estote fortes — quit ye like men, be strong

- virtus tentamine gaudet — strength rejoices in the challenge

- virtute et armis — by virtue and arms; or “by manhood and weapons”; state motto of Mississippi

- vive memor leti — live remembering death

- vivere est vincere — to live is to conquer; Captain John Smith’s personal motto

- vivere militare est — to live is to fight

- vox populi — voice of the people

Previous Next

Ключевые слова: borrowings, Latin borrowings in English, native word stock, borrowed word units, the process of assimilation, periods of borrowing, loan-words, the word stock.

Each language is considered to be a social phenomenon. Therefore, it is always at the stage of development. As any phenomenon, the language does not stay unchanged for a considerable period of time, it can widen its stock by borrowing word units from other languages. In order to understand the contemporary language state, its grammatical forms, phonetic system and its lexical structure, each language phenomenon is considered to be a result of lengthy historical development and a number of changes and transformations.

The subject matter of my scientific article is to analyze the notion of Latin borrowings in the English language and prove how essential this issue is. One of the practical objectives of the paper is to review and study a number of words of Latin origin in the English word stock due to the Etymological Dictionary [4] and, with the help of the examples enlisted, in that way, confirm the topic’s significance in the modern linguistics.

In studying Modern English we regard the language as fixed in time and describe each linguistic level — phonetics, grammar and lexis — synchronically, taking no account of the origin of present-day features or their tendencies to change. The synchronic approach can be contrasted to the diachronic. When considered diachronically, every linguistic fact is interpreted as a stage or step in the never-ending evolution of language. In practice, however, the contrast between diachronic and synchronic study is not so marked as in the theory: we commonly resort to history to explain current phenomena in Modern English.

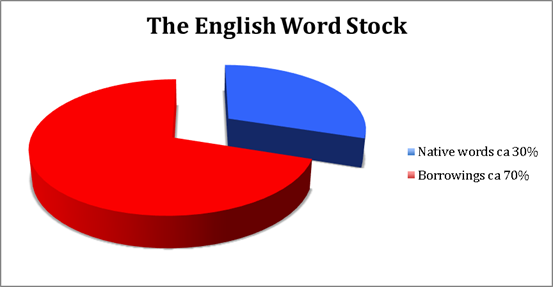

Firstly, I’d like to stress, that the most significant feature of the English language is considered to be its mixed character. As it was noted by Professor Smirtitskiy in his work [11, p.40–50], due to close contacts with other languages, it is believed that foreign influence is the most important factor in the history of English. Though native words constitute only 30 % of the English vocabulary, they are the most frequently used ones. The bulk of words of native origin has been preserved and consists mostly of very ancient elements: Indo-European, Germanic and West-Germanic cognates. Words of the Indo-European stock have parallels in different Indo-European languages: Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, etc.:

Let’ s give the illustration with the example of the word «father»:

Table 1

Illustration of the common Indo-European word stock

|

fæder (Old English) |

pere (French) |

|

fadar (Gothic) |

páter (Latin) |

|

pedær (Persian) |

pitr (Sanscrit) |

|

fader (Swedish) |

Vater (German) |

|

patér (Greek) |

papá (Spanish). |

Words of the Common Germanic stock have cognates only in the Germanic group: in German, Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic, etc. For example, the verb «to sing» has the following parallels:

— singan (Old English);

— siggwan (Gothic);

— singen (German) [2, p.16–67]

Secondly, borrowing from other languages has been characteristic of English throughout its history. More than 2/3 of the English vocabulary are borrowings and mostly they are words of Romanic origin, especially that of Latin.

Fig. 1. The approximate borrowings percentage in English

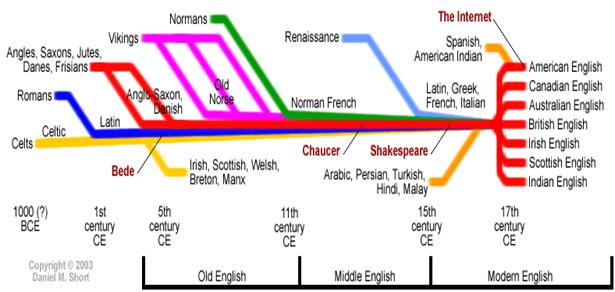

Latin words were borrowed in all historical periods. English history is rich in different types of contacts with other countries, that is why it is very rich in borrowings. The Roman invasion, the Christianizing of Britain in the VI c. and the Middle English period — each time piece is highly informative in this way. There are quite a lot of them in medicine, chemistry, in technology, politics.

Fig. 2. The process of borrowing throughout the time line and its sources

Chart-2 Explanation:

Bede: Bǣda or Bēda (Old English); (ca.672/673–26 May 735), also known as Saint Bede or the Venerable Bede (Bēda Venerābilis (Latin), an English monk at the monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth.

Chaucer: Geoffrey Chaucer (ca. 1343–25 October 1400), known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages.

Shakespeare: William Shakespeare (26 April 1564–23 April 1616), the English poet, playwright and actor, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist (if ever really existed — the author).

The Internet: a global system of interconnected computer networks, carrying an extensive range of information resources and services, used for sharing information throughout the globe.

The borrowing process is gradual and includes such notion as the process of assimilation (phonetic, grammatical and lexical) — i.e. words adjust themselves to the phonetic and lexico-grammatical norms of the language. In the present article I will dwell upon the notion of assimilation of borrowings, degree of assimilation, the role of native and borrowed elements in the Modern language, influence of Latin borrowings on the English language and try to prove that this topic is significant in the context of the Modern English language.

Now it’s time to dwell upon the issues of words of native origin and borrowings. I have already mentioned that the bulk of words of native origin has been preserved and comprises about 30 % of the English vocabulary. It’s interesting to find out that almost all words of Anglo-Saxon origin belong to very important semantic groups. [9, p.50–69]. For the better illustration we can divide the notional words of Anglo-Saxon origin into such groups as denoting:

Table 2

|

— parts of the body: · head · arm · back · hand, etc. — members of the family and closest relatives: · father · mother · son · wife, etc. — natural phenomena and planets · snow · wind · star · moon, etc. |

— qualities and properties: · long · old · dark · hot · cold, etc. — common actions: · to do · to make · to go · to eat · to come · to hear, etc. |

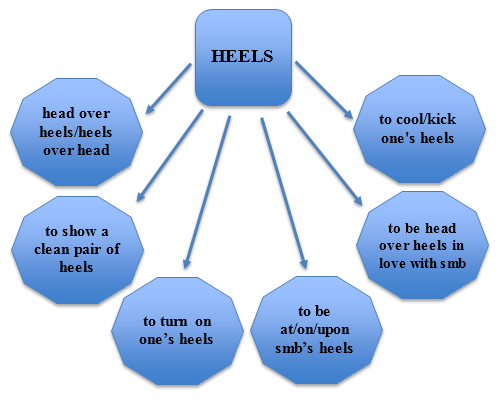

Most native words possess a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency. Many of them enter a number of phraseological units: for instance, the word «heel» enters the following phraseological units:

— head over heels/heels over head — «upside down»;

· to show a clean pair of heels — «run away»;

· to turn on one’s heels — «turn sharply round»;

· to be at/on/upon smb’s heels — «follow smb».;

— to be head over heels in love with smb. — «to love smb. deeply»;

— to cool/kick one’s heels — «keep waiting in vain», etc.

Fig. 3. A phraseological unit illustrating the lexical valency

And now it’s high time we passed over to the issue of borrowings.

Due to the specific historical development of English, it has adopted many words from other languages, especially from Latin. We should bear in mind that all borrowed words undergo the process of assimilation (phonetic, grammatical, lexical), i.e. they adjust themselves to the phonetic and lexico-grammatical norms of the language. [3, p.87–102] Phonetic assimilation comprises substitution of native sounds and sound combinations for strange ones and for familiar sounds used in a position strange to the English language, as well as shift of stress.

For example, words like «honour», «reason» were accented on the same principle as «father», «mother».

Grammatical assimilation finds expression in the change of the morphological structure of the word. Usually as soon as words from other languages were introduced into English they lost their former grammatical categories and paradigms and acquired new grammatical categories by analogy with other English words, as in the following examples:

e.g.

Им. спутник Com. sing. Sputnik

Род. cпутника Poss. sing. Sputnik’s

Дат. cпутнику Com. pl. Sputniks

Вин. cпутник Poss. pl. Sputniks’

Тв. спутником

Предл. о спутнике

However, there are some words in Modern English that have retained for centuries their foreign inflexions. e.g. phenomenon (Latin) — phenomena; addendum (Latin) — addenda.

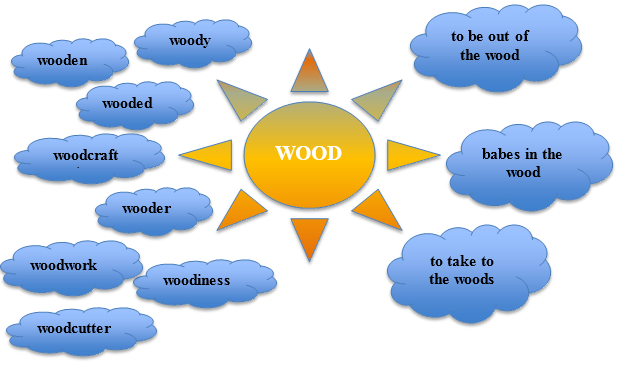

And, finally, lexical assimilation includes changes in semantic structure and the formation of derivatives. [1, pp.60–77, 255–259] For instance, the word «wood» is the basis for the formation of a number of new words: wooden, woody, wooded, woodcraft, wooder, woodiness, woodcutter, woodwork and many others. Moreover, the word enters a number of idiomatic expressions (e.g. «to be out of the wood» — to come out of danger, «babes in the wood» — ingenious people, «to take to the woods» — to run away, etc.)

Fig. 4. Illustration of the lexical assimilation of borrowings

Now it’s time to say a few words about the practical part of the present article and the scientific interest the results of which it may bring to light. Through the study of the Etymological Dictionary of the English Word Stock, namely, the Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology [4], I achieved the following goals that were as follows: firstly, to prove that there really was a great deal of word units borrowed from Latin through the history of the English language and, secondly, to elicit some examples and make certain conclusions.

It’s true that English vocabulary, which is one of the most extensive among the world’s languages, contains an immense number of words of Latin origin. Having studied the Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology, I came to the conclusion that there really is a great number of words of Latin roots in the English word stock. This fact can be explained in the following way: Latin loan-words appeared in the English language throughout the time line. Let’s name the most significant stages of the process:

1. The trend began at those distant times (I c. B.C.) with the words which the West-Germanic tribes brought from the continent when they came to settle in Britain. These borrowings entered the language due to a direct intercourse and trade relations with the peoples of the Roman Empire. Germanic tribes had to use Latin words in order to name new notions they had not known before.

These words mainly denote:

1. names of articles of clothing and household use:

For instance, such words as «a cap» — from L. L. cappa «a cape, hooded cloak», possibly shortened from capitulare — «headdress» (from L. caput «head»);

«a sock» (n.) — O.E. socc «light slipper», from L. soccus «light low-heeled shoe», variant of Gk. sykchos «a kind of shoe». Teenager slang notion «sock hop» dated back to c.1950, from notion of dancing without shoes;

«purple» — O.E. purpul, dissimilation (first recorded in Northumbrian, in Lindisfarne gospel) from purpure «purple garment», purpuren «purple», from L. purpura «purple-dyed cloak, purple dye», also «a shellfish from which purple was made», from Gk. porphyra, of Semitic origin, originally the name for the shellfish (murex) from which it was obtained.

2. words denoting foods:

«radish» — O.E. rædic, from L. radicem, from radix «root»;

«a lobster» — O.E. loppestre, corruption of L. locusta «lobster», literally «locust», by influence of O. E. loppe «spider», variant of lobbe. (Trilobite fossils in Worcestershire limestone quarries were known colloquially as locusts, which seems to be the generic word for «unidentified arthropod», as apple is for «foreign fruit».) Slang for «a British soldier» since 1643, originally in reference to the jointed armor of the Roundhead cuirassiers, later to the red coat;

«millet» — early XVc., from M.Fr. millet, dimension of mil «millet» from L. milium.

3. names of trees, plants, herbs (often cultivated for their medical properties):

«a pine» (n.) — O.E. pintreow, the first element from L. pinus, related to Gk. pitys, from *pi-, found in words for «fat, sap, pitch».

«a savory» (n.) — «a herb», probably an alteration of O. E. sæþerie, from L. satureia.

2. The second period of Latin borrowings is marked by the slightest influence of Latin due to the Romanized Celts. There was no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and such Latin words as could have found their way into English would have had to come in through Celtic transmission.

For instance, names of places:

«Manchester» — Mameceastre (1086), from Mamucio (4c.), the original Celtic name, probably from *mamm «breast, breast-like hill» + O.E. ceaster — «a Roman town».

«Belgium» — 1602, from L. name of the territory occupied by the Belgæ, a Celtic tribe.

3. The third and the vastest borrowing period occurred after the Adoption of Christianity in the 6th century and the appearance of monasteries and churches. It resulted in a great number of church-word borrowing that entered the language. Here are some examples provided:

«an altar» — O.E., from L. altaria — «burnt offerings», but influenced by L. altus — «high».

«a candle» — O.E. candel, early church-word borrowing from L. candela — «a light, torch», from candere — «to shine». Unknown in ancient Greece, but common from early times among Romans and Etruscans. Candles on birthday cakes seem to have been originally a German custom. «To hold a candle to» originally meant «to help in a subordinate capacity».

«a deacon» — O.E. deacon, from L. diaconus, from Gk. diakonos «a servant of the church, religious official».

As the number of these words is almost five hundred, surely it seems impossible to elicit all of them in the atricle.

4. And finally, another pre-eminent group of Latin borrowings entered English with the revival of learning (XV-XVI centuries) at the Renaissance times. [6, p.70–125] Latin was drawn upon the scientific nomenclature. As at that time the language was understood by scientists all over the world, it was considered the common name-language for science. These words were mainly borrowed through books, by people who knew Latin well and tried to preserve the Latin form of the word. Here are the examples:

«an antenna» — appeared in 1646, from L. antenna — «a sail yard», the long yard that sticks up on some sails, translation of Gk. keraiai «insects’ horns». Modern use in radio, etc., is from 1902. (the plural form is «antennae»).

«a phenomenon» — 1576, «a fact, an occurrence», from L. phaenomenon, from Gk. phainomenon — «something which appears or is seen», noun use of neut. prp. of phainesthai «appear». The meaning «extraordinary occurrence» first recorded in 1771. The plural form is «phenomena». Phenomenal — meaning «smth. of the nature of a phenomenon» is from 1825. The shortened form phenom is from the baseball slang, first recorded ca.1890.

«a formula» — 1638, from L. formula — «a form, rule, method, formula», dim. of forma — «a form». Originally, «words used in a ceremony or ritual». The plural form is «formulae».

As we have seen in the stated examples these nouns preserved their original plural inflexion to this day and these forms still exist in the language. A great number of them has suffixes that clearly mark them as Latin borrowings of the time:

— verbs ending at –ate, -ute:

«to aggregate» — c.1400, from L. aggregatus/ aggregare — «add to», from ad- «to» + gregare — «a herd»;

«to separate» — early XVc., from L. separatus/separare, from se — «apart» + parare — «to make ready, prepare». The adjective meaning «detached, kept apart» is first recorded ca.1600, from the pp. used as an adjective. Separatism (1628) and separatist (1608) were first used in religious sense;

«to prosecute» — XVc., from L. prosecutus, pp. of prosequi — «follow after». The meaning «to bring to a court of law» is first recorded in 1579.

— adjectives ending in –ant, -ent, -ior, -al:

«evident» — mid. XIVc., from L. evidentem (nom. evidens) — «perceptible, clear, obvious», from ex- «fully, out of» + videntem (nom. videns), prp. of videre «to see». Evidence is L. L. evidentia — «proof», originally — «distinction»;

«superior» — XIVc., from L. superior — «higher», comparative of superus — «situated above, upper», from super — «above, over»;

«cordial» — XIVc., from M. L. cordialis — «of or for the heart», from L. cor (gen. cordis) — «heart». Original sense of the notion was medicine, foods and drinks that stimulate the heart. [6, p.350–378]

The significance of Latin borrowings can be marked not only in the distant times but nowadays too. Surprisingly, but borrowings continue to appear in Modern English as well.

There are quite a lot of them, for instance:

1. in medicine;

«aspirin» — coined in 1899 in Germany as a trademark name, either from from Gk. a- «without» + L. spiraea, the plant in which the natural acid in the medicine is found, or a contraction of acetylierte spirsaure, the name of the acid found in the leaves of the plant.

2. in chemistry;

«valence» — 1884, from L. valentia — «strength, capacity», from valentem (nom. valens), prp. of valere — «be strong».

Now it’s high time we made certain conclusions, according to the investigation, carried out in the given scientific article. Comparing the amount (153 words analyzed) and strata of Latin borrowings on the English language in different historical periods, we get the following results that are best presented in the form of a table.

Table 3

The strata of borrowing

|

I c. B.C.- III c. A.D. |

IV c. A.D. |

VI c. A.D. |

XII-XIII c. A.D. |

XV-XVI c. A.D. |

|

Articles of clothing |

Names of places |

Church nomenclature |

Common vocabulary |

Scientific strata |

|

Articles of household use |

Words denoting religious notions |

Medicine |

||

|

Words denoting foods |

Chemistry |

|||

|

Names of trees, plants, herbs |

Technology |

|||

|

Words connected with war and trade |

||||

|

Notions for construction and building spheres |

||||

|

Units of measurement and containers |

Table 4

The amount of borrowed word units (according to the number of words analysed-153)

|

Date |

Number of Latin Borrowings |

|

I c. B.C. — III c. A.D. |

8 |

|

IV c. A.D. |

1 |

|

VI c. A.D. |

18 |

|

XII c. A.D. |

4 |

|

XIII c. A.D. |

5 |

|

XIV c. A.D. |

31 |

|

XV c. A.D. |

24 |

|

XVI c. A.D. |

31 |

|

XVII c. A.D. |

25 |

|

XVIII c. A.D. |

3 |

|

XIX c. A.D. |

3 |

Thus, having considered the issue of Latin borrowings in the English language we can draw the following conclusions on the basis of the material studied above.

The role of the Latin language in Medieval Britain is clearly manifest; it was determined by such historical events as the Roman occupation of Britain, the influence of the Roman civilization, the introduction of Christianity and the Renaissance. It is no wonder that the Latin language exerted considerable influence on different aspects of English: the Old English alphabet, the growth of writing and literature. The impact of Latin on the Old English vocabulary enables us to see the spheres of Roman influence on British life.

Latin words entered the English language at different stages of the history. Chronologically they can be divided into several layers.

1. The earliest layer comprises words, which the West-Germanic tribes brought from the continent when they came to settle in Britain. For instance, weall (wall), straet (road, street), mîl (mile). The contact with the Roman civilization began long before the Anglo-Saxon invasion.

2. The adoption of Latin words continued in Britain after the invasion, since Britain had been under Roman occupation for almost 400 years. Later on Latin words were transmitted to them by the Romanized Celts. Early borrowings from Latin indicate the new things and concepts learned from the Romans: they pertain to war, trade, agriculture, construction and building and home life.

Words connected with tradeindicate general concepts, units of measurements and articles of trade unknown to the Teutons before they came into contact with Rome: Old English cēapian, cēap, cēapman and manZian, manZunZ, manZere (to trade, deal, trader, to trade, trading, trader) came from the Latin names for ‘merchant’ — caupo and mango. Units of measurement and containers were adopted with their Latin names: Old English pund (New English pound), ynce (inch) from Latin pondo and uncia.

The following words denote articles of trade and agricultural products, introduced by the Romans: O.E. win (from L. vinum), O.E. butere (from L. būtyrum), O.E. plume (from L. prunus), O.E. ciese (from L. cāseus), O.E. pipor (from L. piper), (N.E. wine, butter, plum, cheese, pepper).

A great number of words related to building, domestic life and military affairs were borrowed into the English language: O.E. cealc — N.E. chalk; O.E. pyle- N.E. pillow, etc.

3. Among the Latin loan-words adopted in Britain there were some place-names or components of place-names used by the Celts. Latin castra in the shape caster, ceaster — «camp» formed O. E. place-names which survive today as Chester, Dorchester, Lancaster and the like (some of them with the first element coming from Celtic); L. colonia — «settlement for retired soldier» is found in Colchester and in the Latin-Celtic hybrid Lincoln; L. vicus –«villag’» appears in Norwich, Woolwich, L. portus — in Bridport and Devonport.

4. The next period of Latin influence on the Old English vocabulary began with the introduction of Christianity in the late 6th c. Numerous Latin words which found their way into the English language during these five hundred years clearly fall into two main groups:

1. words pertaining to religion,

2. words connected with learning. [8, p.236–240]

The new religion introduced a large number of new conceptions which required new names. Most of them were adopted from Latin, some of the words go back to Greek prototypes: (O.E. apostol; apostle from L. apostolus from Gk. apóstolos).

We may also add to this list some other modern English words from the same source: abbot, alms, altar, angel, ark, creed, disciple, hymn, idol, martyr, noon, nun, organ, palm, pine, pope, prophet, psalm, psalter, shrine, relic, rule, temple and others.

5. After the introduction of Christianity many monastic schools were set up in Britain. The spread of education and the Great Revival of Learning led to the wider use of Latin: teaching was conducted in Latin, or consisted of learning Latin. These conditions are reflected in a large number of borrowings connected with education, and also words of a more academic, «bookish» character. Unlike the earlier borrowings scholarly words were largely adopted through books; they were first used in O. E. translations from Latin, e.g.: (O.E. scōl; N.E. school; L. schola (Gk. skhole).

Due to this analysis we come up to the conclusion that the issue of the words borrowed from Latin is the important and significant one. As we see, Latin words were borrowed in particular historical periods and due to close contacts with the Roman civilization nowadays we have the abundance of Latin loan-words in the Modern English word stock. The significance of borrowings should not be underrated because they reflect the whole history and that very time period when they entered the English language. However, it is rather difficult to trace accurately the development and ways of assimilation of borrowings as these events are so far back in history. Nevertheless, it becomes more captivating, necessary and reasonable to analyze this very issue — Latin borrowings in the English language and understand how Roman civilization influenced English word stock as numerous traces of this influence are clearly seen even now.

References:

1. Arnold I. V. The English Word. Лексикология совр.англ.яз./И. В. Арнольд. — M.: Высшая школа, 1986, p.295.

2. Baugh A., Cable Th. A History of the English Language./Fifth Edition. — Routledge, London, 2002, p.447.

3. Barber Charles, Beal Joan C., Shaw Philip A. The English Language: A Historical Introduction./Charles Barber. — Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, p.322.

4. Barnhart, Robert K., Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology./Robert K.Barnhart. — London, Collins, 1995, p.944.

5. Lass R. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion./R.Lass. — Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, p.324.

6. Williams J. M. Origins of the English Language: A Social and Linguistic

7. History./ J. M. Williams. — New York: The Free Press, 1975, p.418.

8. Аракин В. Д. Очерки по истории английского языка: Учеб.пособие./В.Аракин. — М.: Физматлит, 2007, p.288.

9. Аракин В. Д. История английского языка./Под редак. О. А. Пекиной. — М.: Физматлит, 2003, p.272.

10. Дубенец Э. М. Лексикология современного английского языка: Modern English Lexicology./Э. М. Дубенец. — М.: «Глосса-Пресс», 2002, p.192.

11. Секирин В. П. Заимствования в английском языке./В. П. Секирин. — Киев: Изд-во Киевского унив., 1964, p.152.

12. Смирницкий А. И. Хрестоматия по истории английского языка с VII по XVII вв.: Серия «Классическая учебная книга»./А. И. Смирницкий. — М.: Академия, 2008, p.304.

Основные термины (генерируются автоматически): XV-XVI, английский язык, III, VII, XII-XIII, спутник.